Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

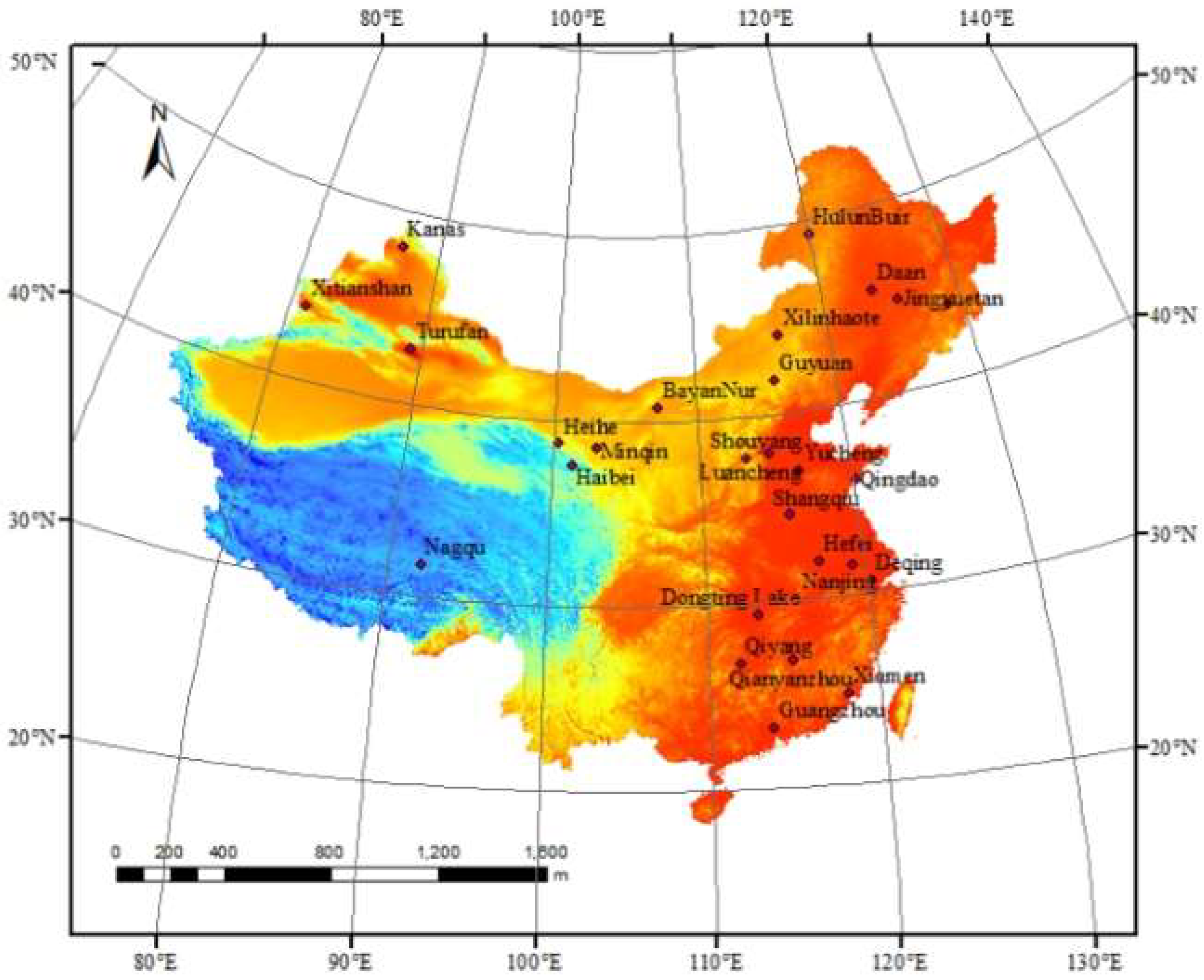

2.1. Study area

2.2. Data resources

2.3. Regional Division

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Temporal change

2.4.2. Spatial distribution characteristics

2.4.3. Analysis Methodology of Influencing Factors

3. Results and Discussion

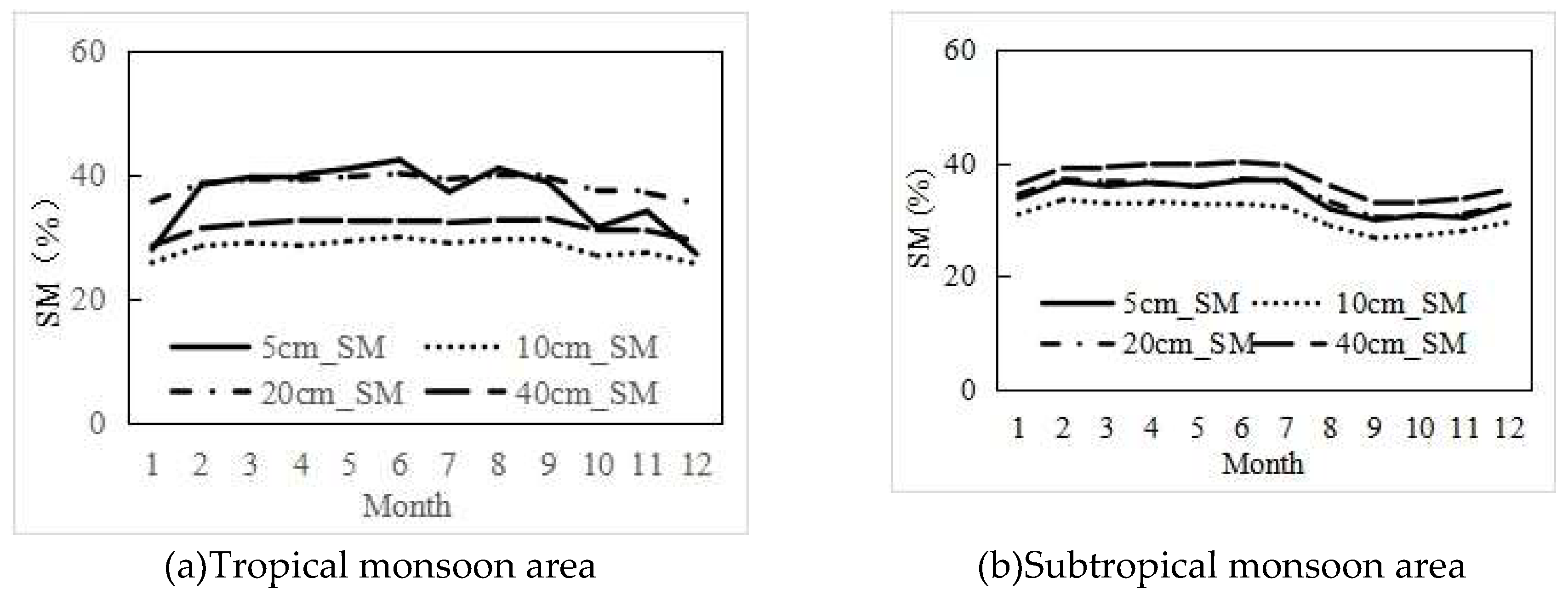

3.1. Temporal Dynamics of SM

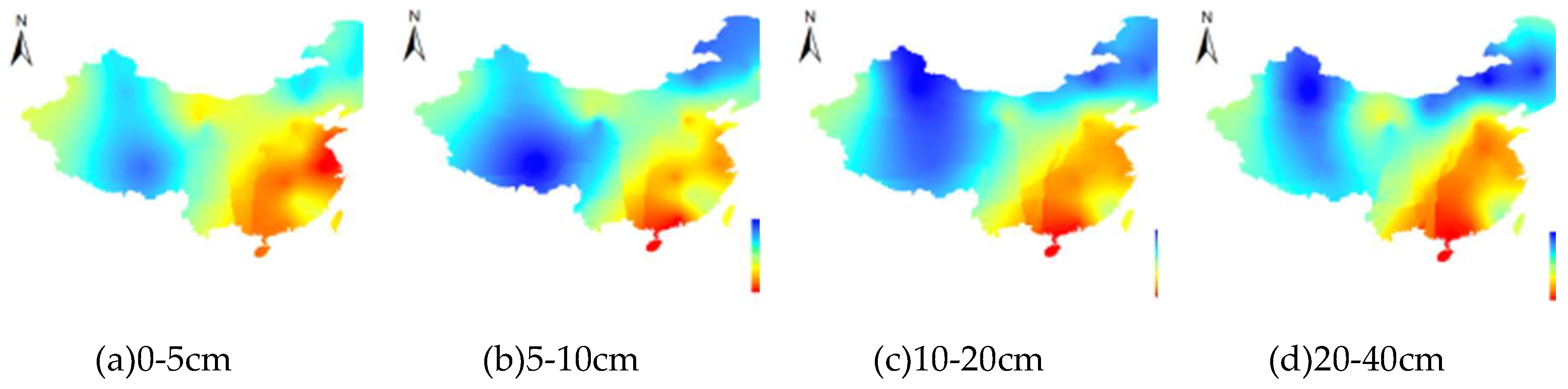

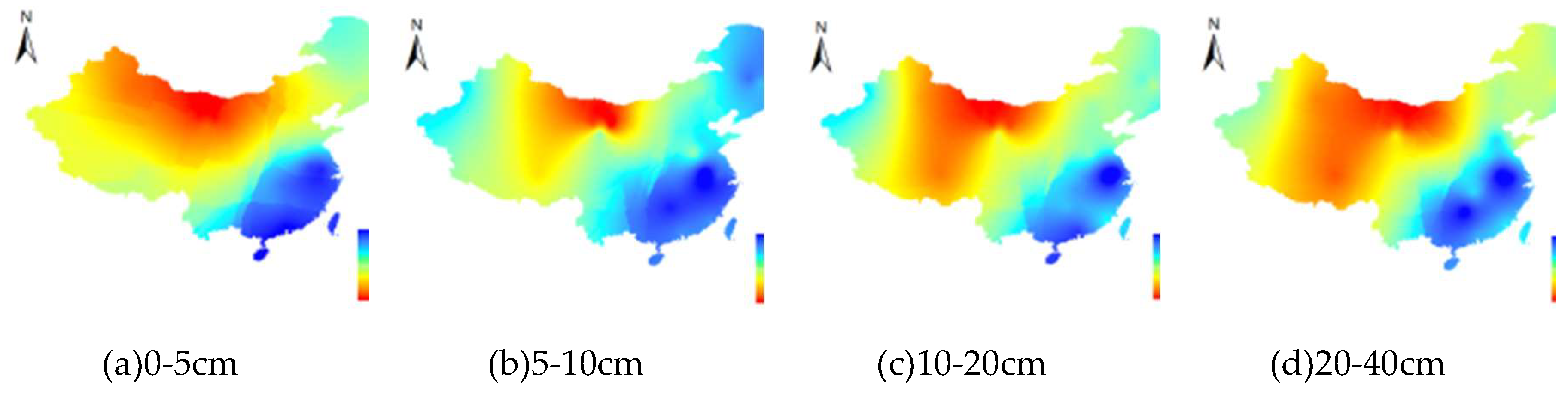

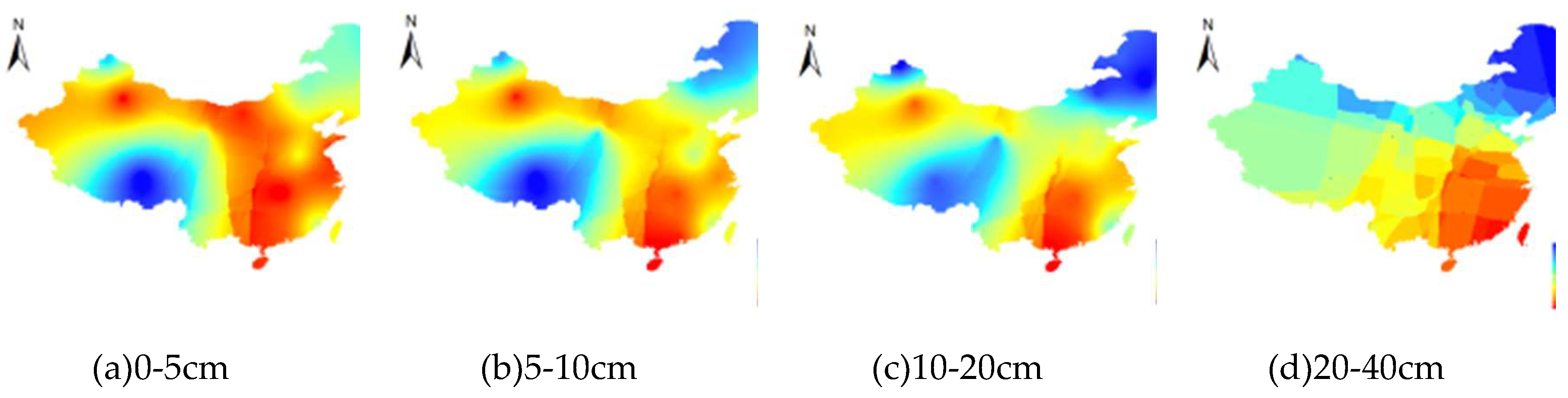

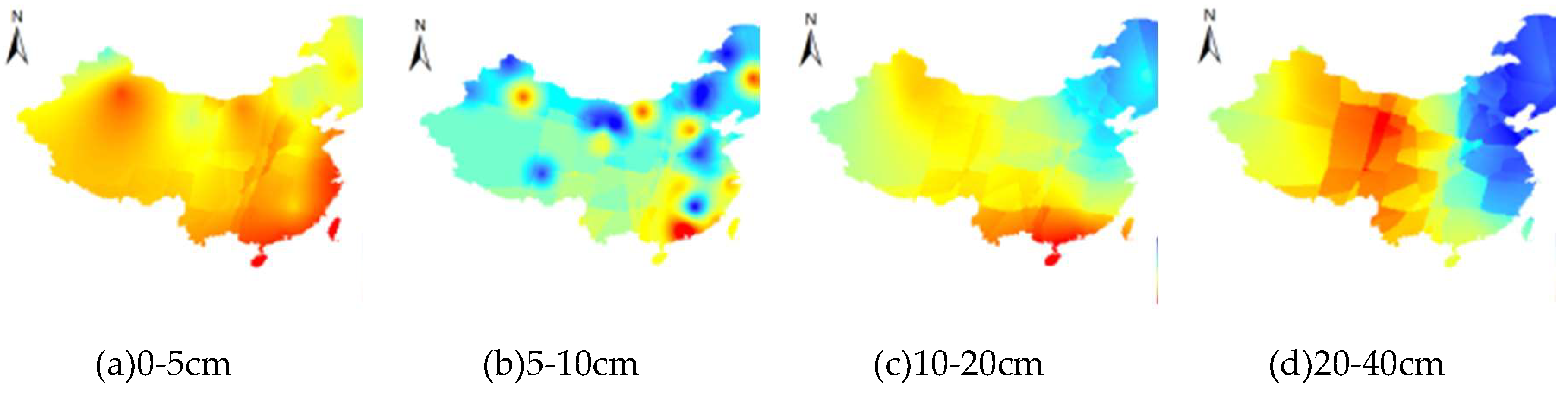

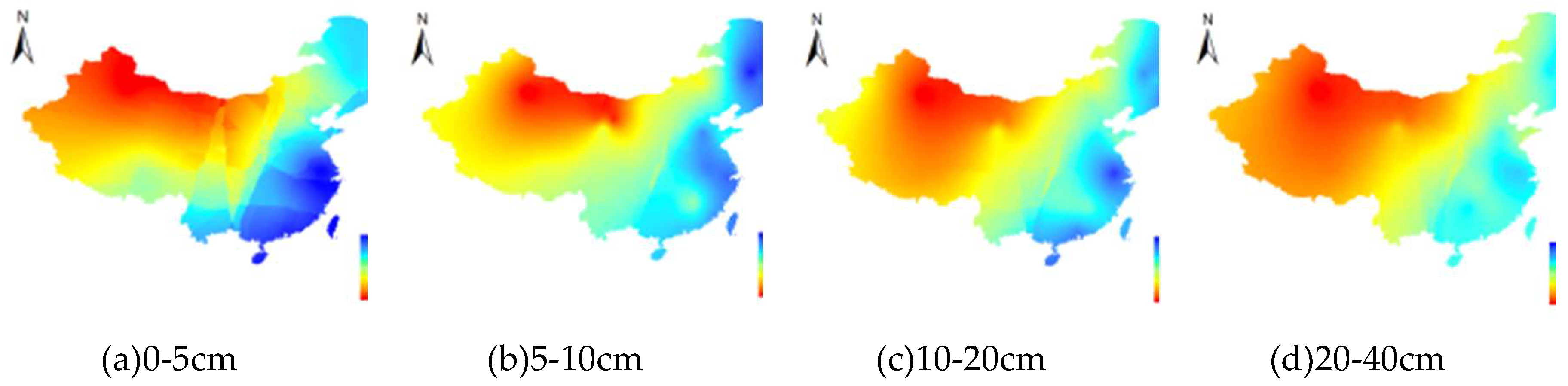

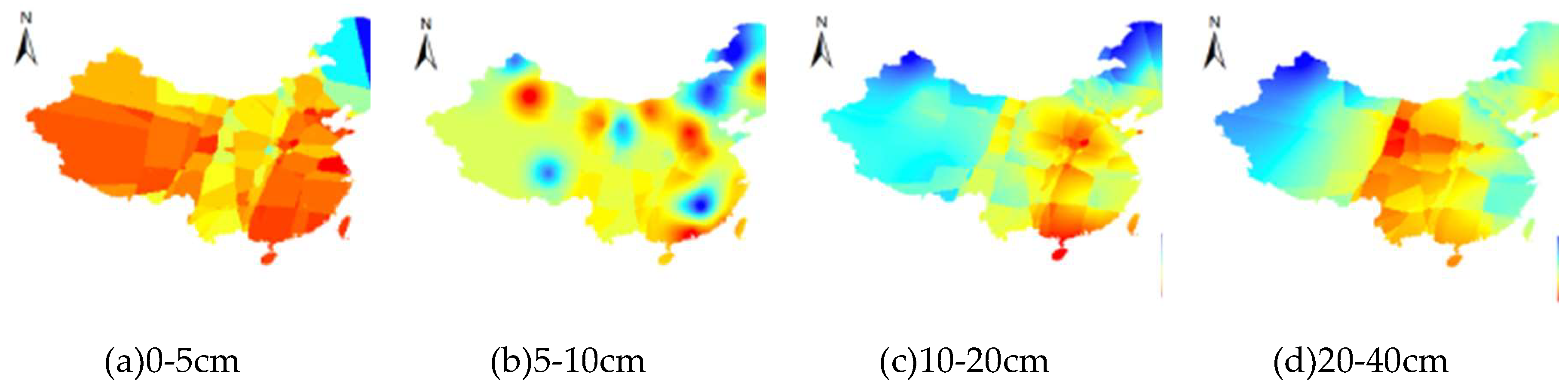

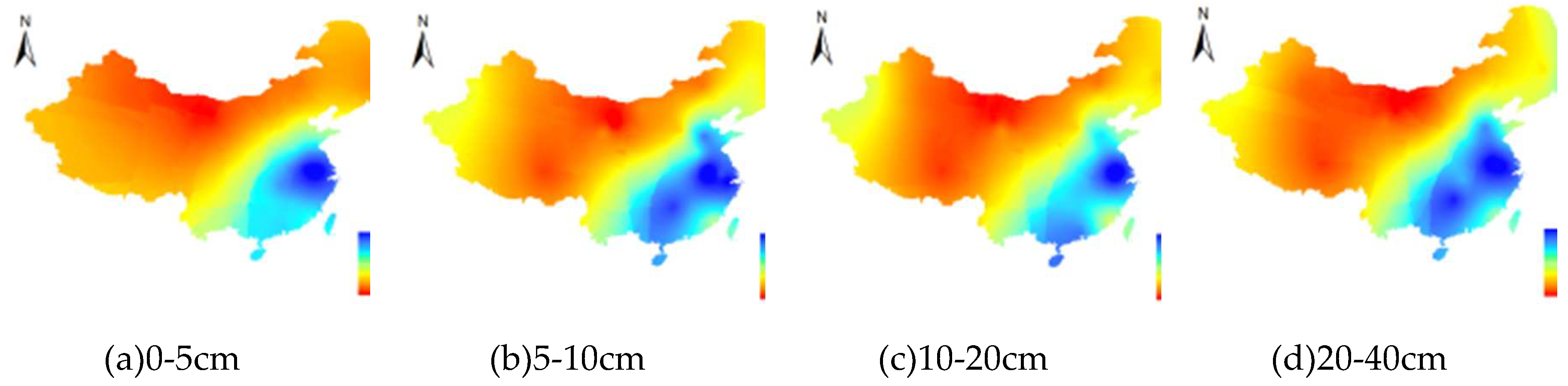

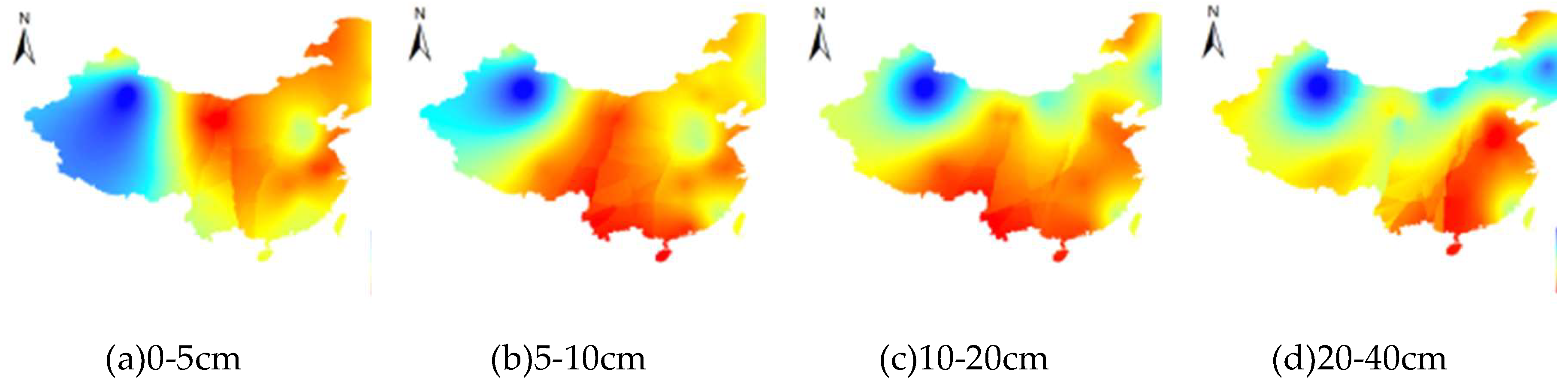

3.2. Spatial distribution characteristics of soil moisture content

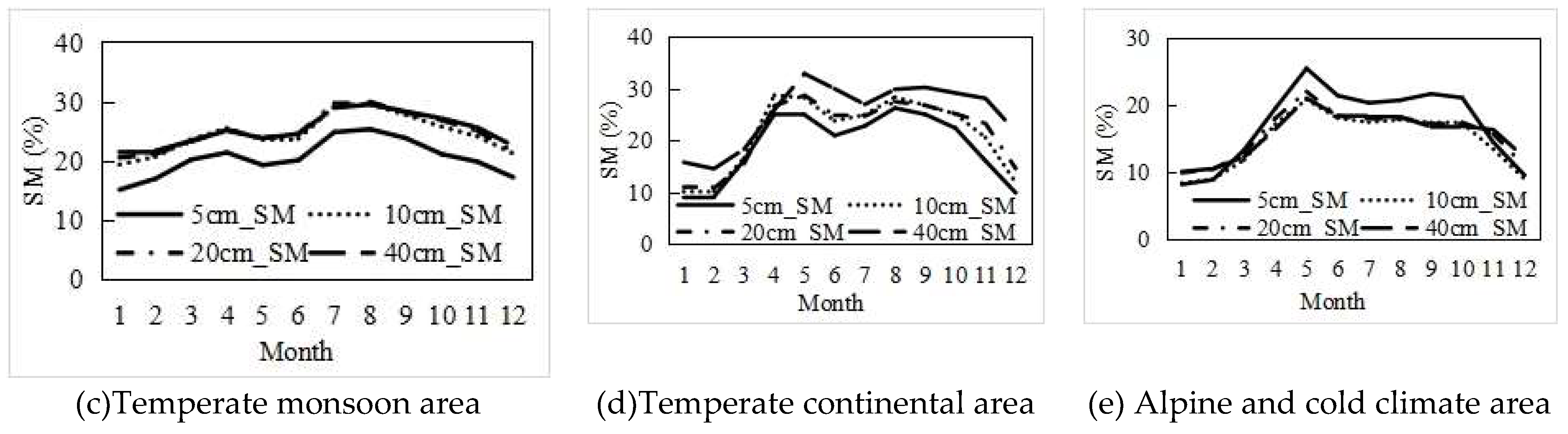

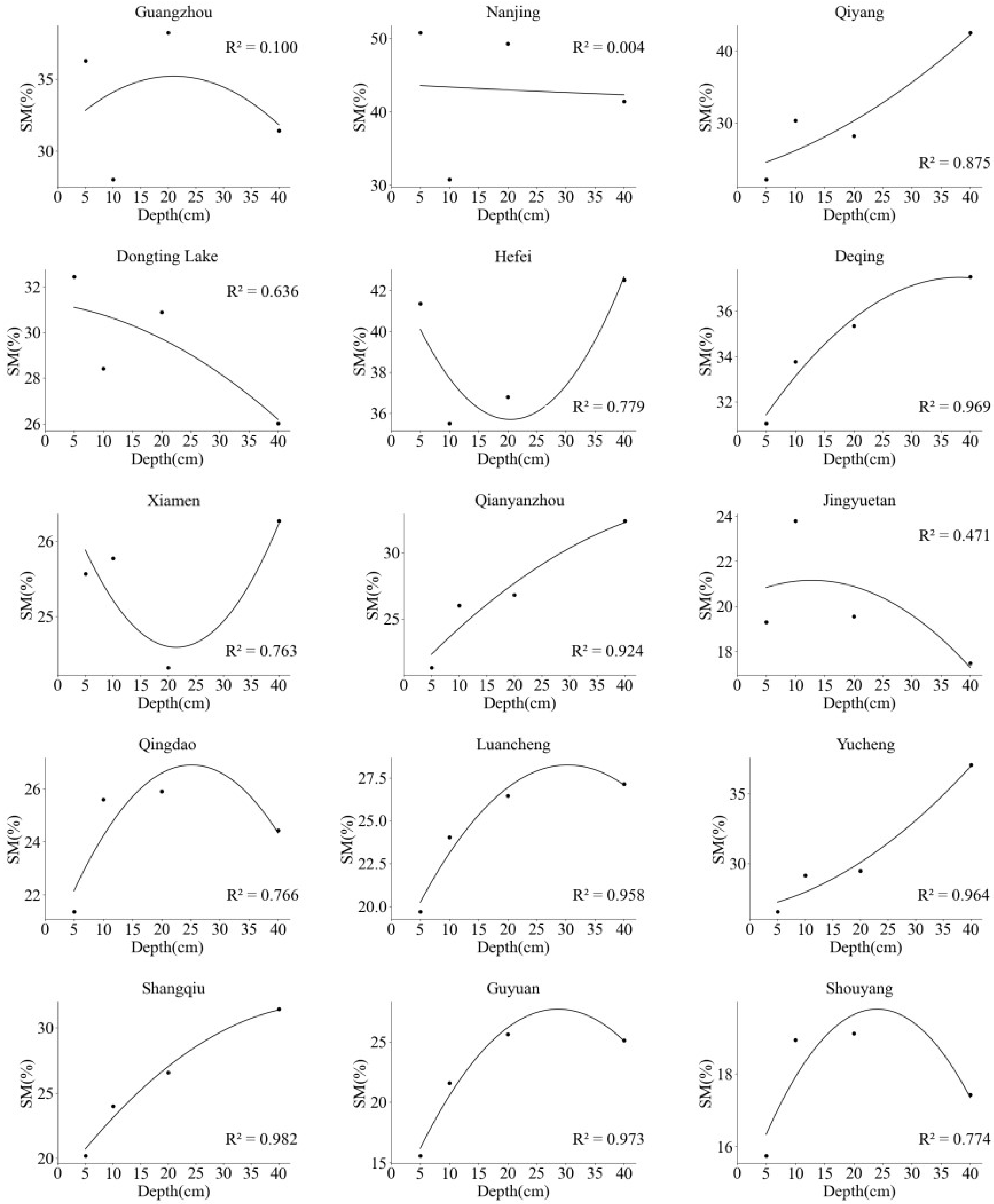

3.3. The SM change pattern with increasing soil depth

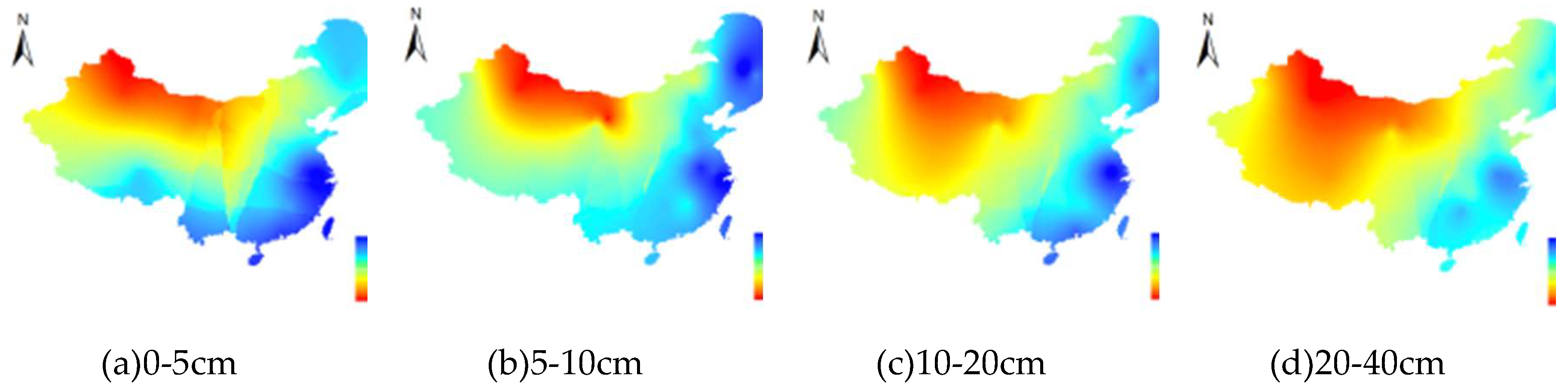

3.4. Effects of Meteorological Factors on SM

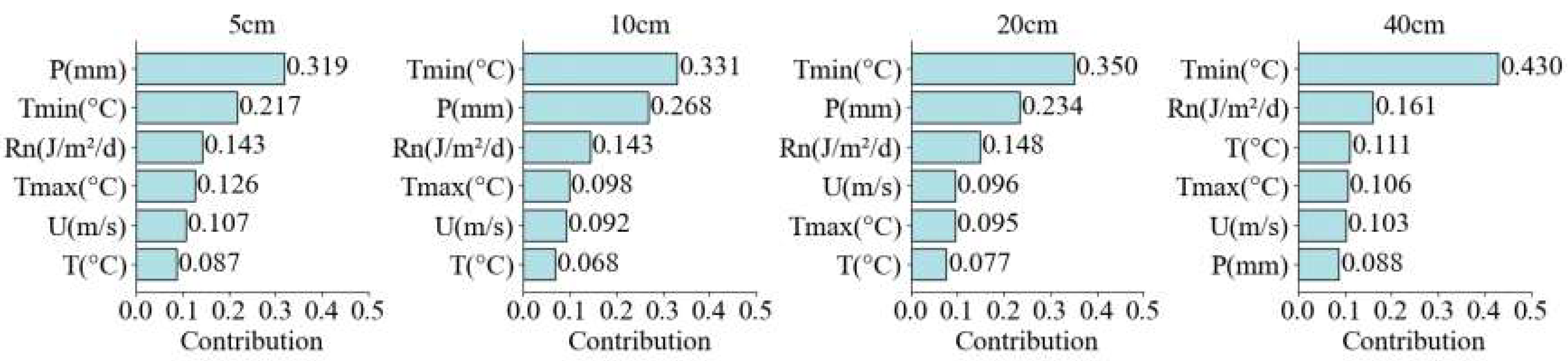

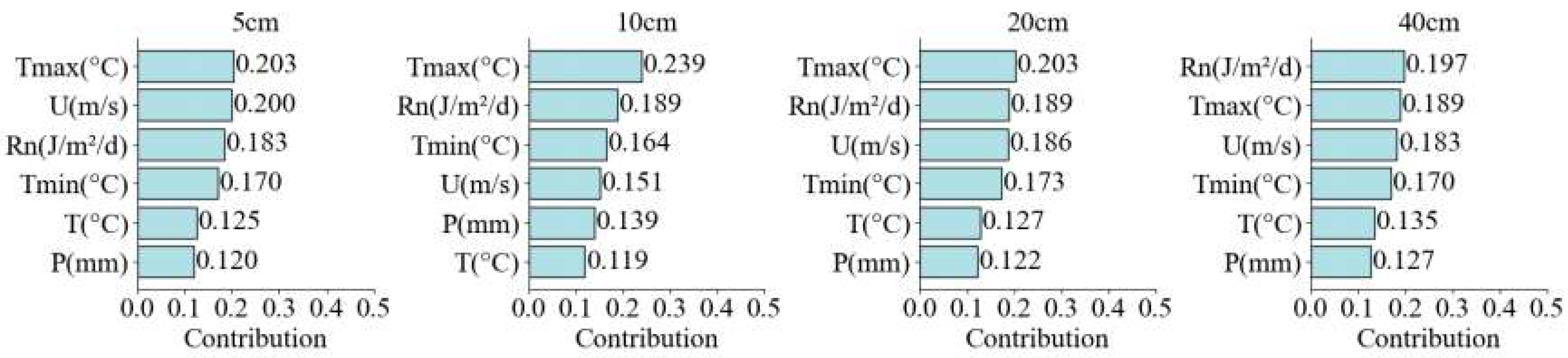

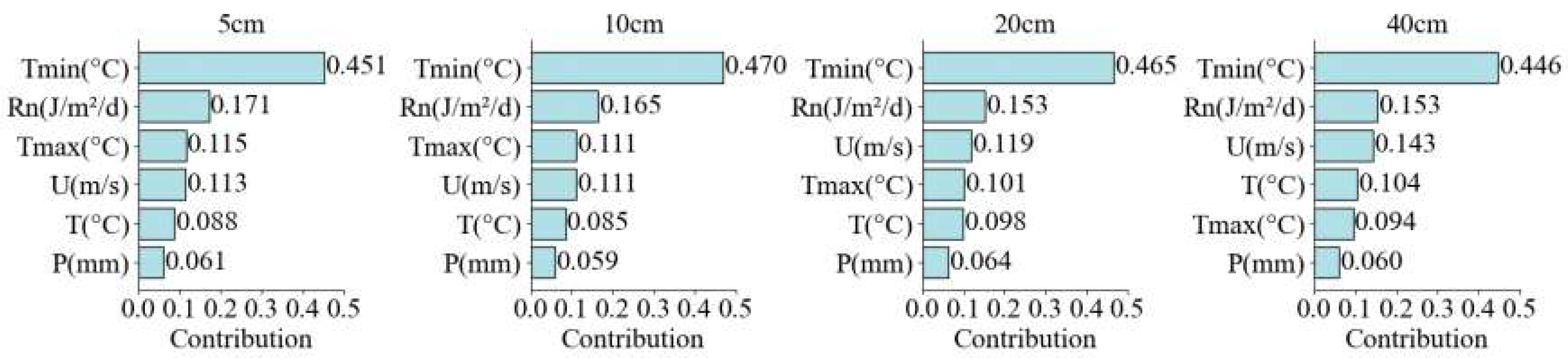

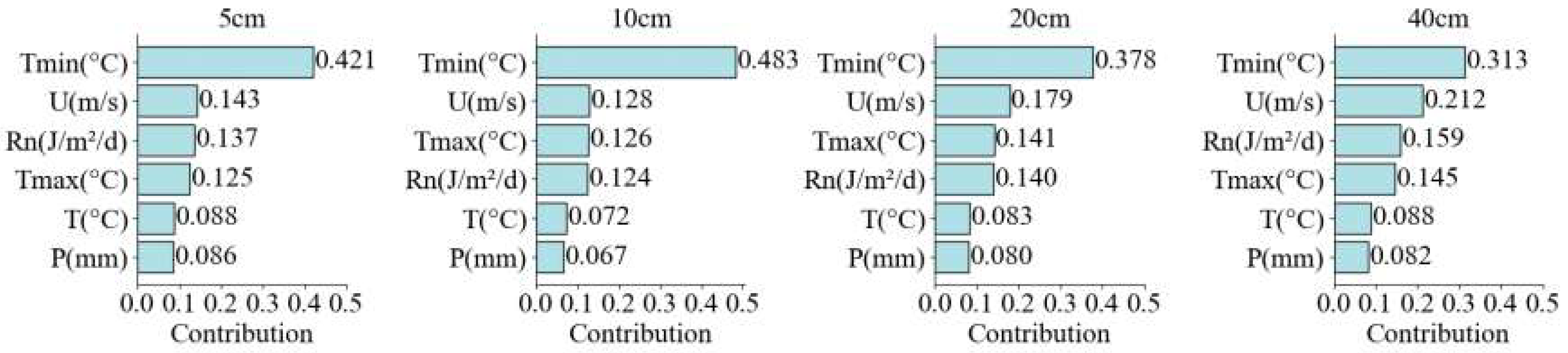

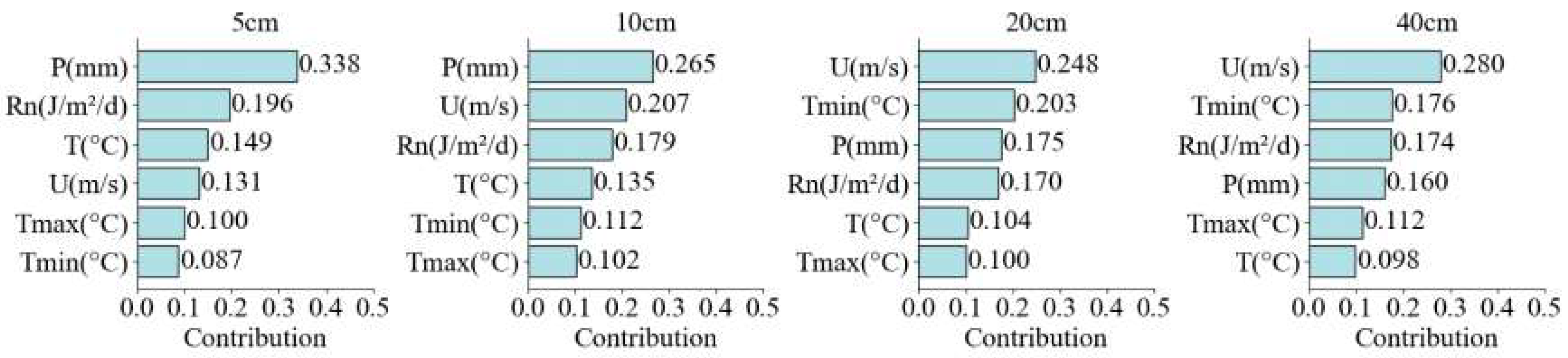

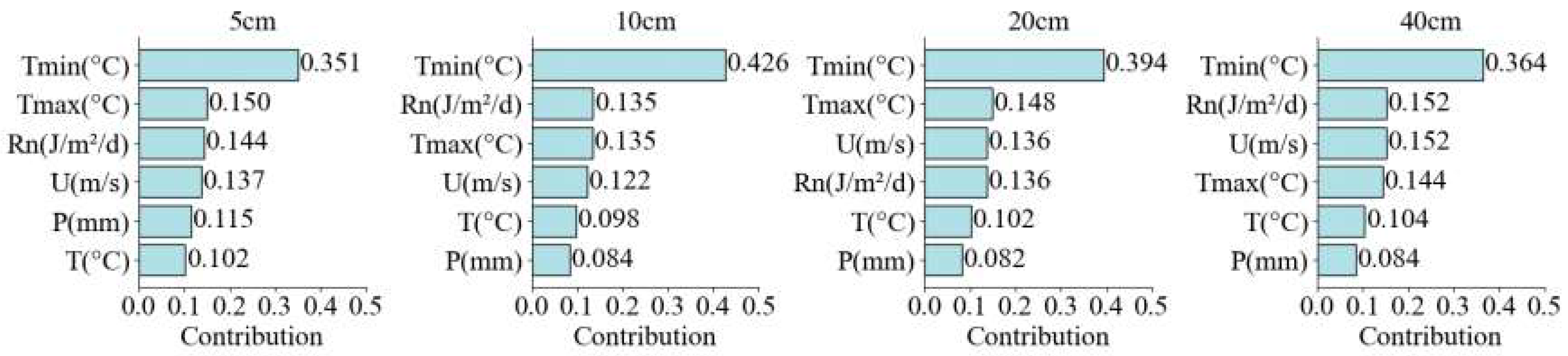

3.5. Contribution Analysis of meteorological factors to SM in different soil layers

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial differences analysis of Cv for SM

4.2. The impact of underlying surfaces and human activities on soil moisture content

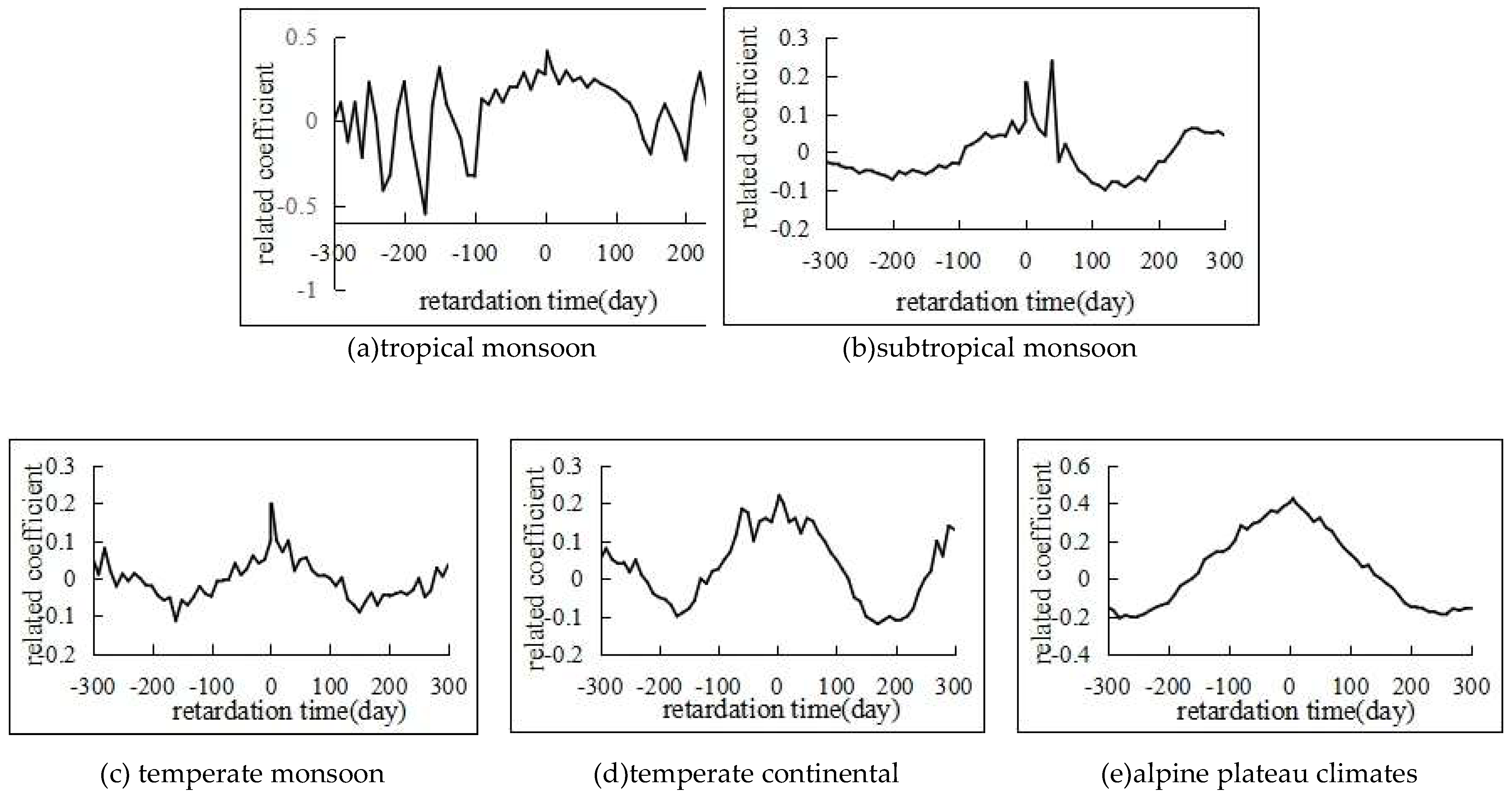

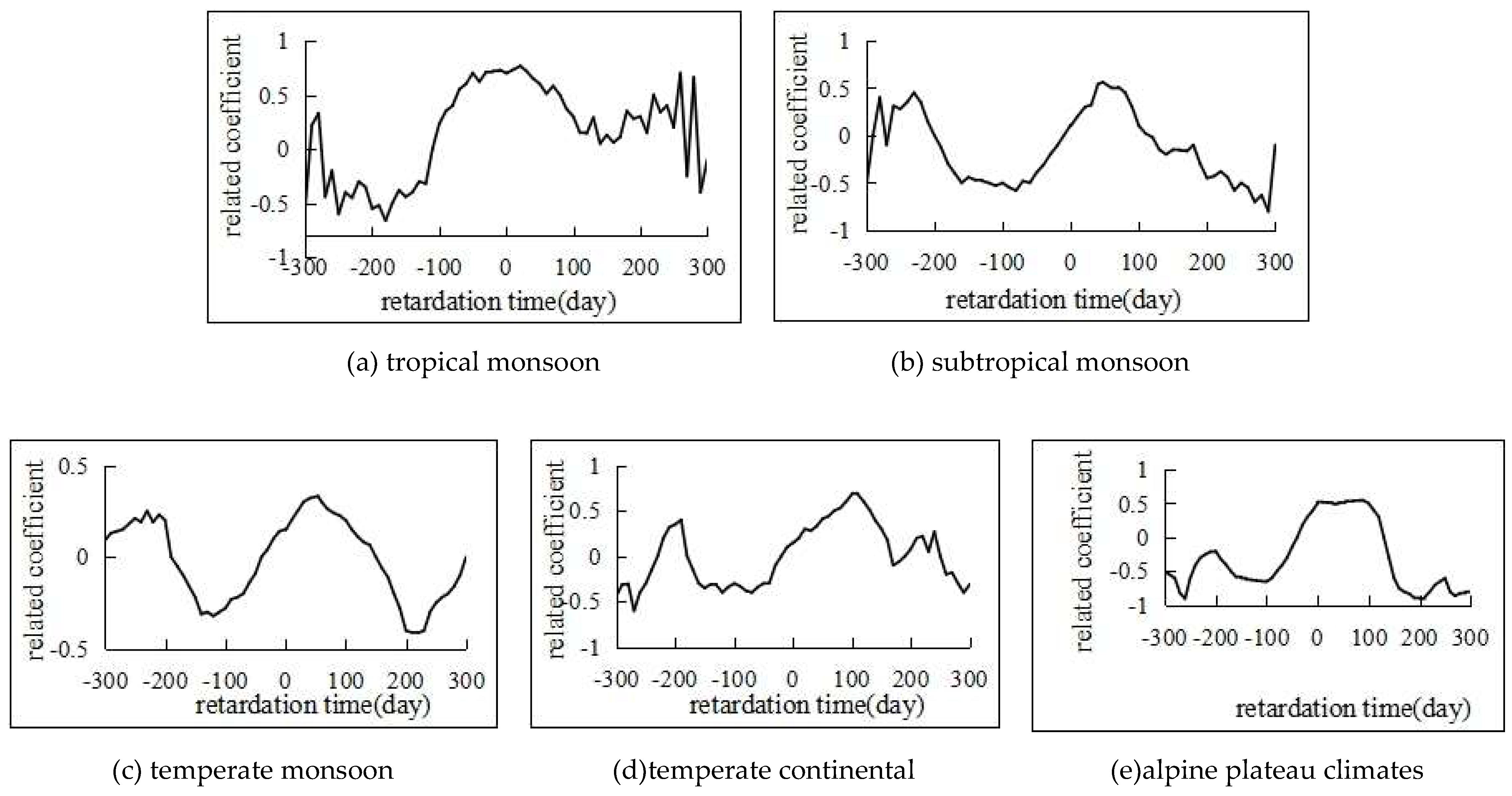

4.3. Lagged Effect of Meteorological Factors to Soil Moisture

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bláhová, M.; Fischer, M.; Poděbradská, M.; Štěpánek, P.; Balek, J.; Zahradníček, P.; Kudláčková, L.; Žalud, Z.; Trnka, M. Testing the reliability of soil moisture forecast for its use in agriculture. Agric. Water Manage. 2024, 304, 109073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.X.; Yin, Z.E.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.K. Spatiotemporal variations of precipitation extremes of China during the past 50 years (1960–2009). Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2016, 124, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.L.; Wang, J.L.; Pan, Y.Y.; Huang, N.; Zang, Z.Y.; Peng, R.Q; Wang, Z.Z.; Sun, G.F.; Liu, C.; Ma, S.Q.; Song, Y.; Pan, Z.H. Temporal and Spatial Variation of Soil Moisture and Its Possible Impact on Regional Air Temperature in China. Water 2020, 12, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.J.; Zhou, B.T.; Chen, S.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Cheng, Z.Q.; Wang, F.W.; Mei, X.Y.; Wu, D. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Soil Moisture and Its Driving Factors in the Northern Agricultural Regions of China. Water 2024, 16, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dong, J.W.; Huang, L.; Chen, L.J.; Li, Z.C.; You, N.S.; Singha, M.; Tao, F.L. Characterizing the 2020 summer floods in South China and effects on croplands. Iscience 2023, 26, 107096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.F.; Wang, Y.Q.; Xu, D.Y. Desertification in northern China from 2000 to 2020: The spatial–temporal processes and driving mechanisms. Ecol. Inf. 2024, 82, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.Y.; Qi, H.W.; Shang, S.H. Estimating soil water and salt contents from field measurements with time domain reflectometry using machine learning algorithms. Agric. Water Manage. 2023, 285, 108364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, M.W.; Tang, J.L.; Sarwar, A.; Shah, S.; Saddique, N.; Khan, M.U.; Khan, M.I.; Nawaz, S.; Shamshiri, R.R.; Aziz, M.; Sultan, M. Soil Moisture Measuring Techniques and Factors Affecting the Moisture Dynamics: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouazen, A.M.; Al-Asadi, R.A. Influence of soil moisture content on assessment of bulk density with combined frequency domain reflectometry and visible and near infrared spectroscopy under semi field conditions. Soil Till Res. 2018, 176, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamar, M.; Mohamed, R. Assessment of the impact of climate change on soil moisture using remote sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Int. J. Ecol Dev. 2024, 39(2), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.J.; Huang, Y.H.; Yan, H.B.; Wu, C.L.; Luo, L.; Zhou, B. Temporal and spatial variation of soil moisture in china based on smap data. Isprs Archives 2020, XLII-3/W10, 775–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.P.; Mao, J.F.; Hoffman, F.M.; Bonfils, C.J.W.; Douville, H.; Jin, M.Z.; Thornton, P.E.; Ricciuto, D.M.; Shi, X.Y.; Chen, H.S.; Wullschleger, S.D.; Piao, S.L.; Dai, Y.J. Quantification of human contribution to soil moisture-based terrestrial aridity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13(1), 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.X.; Wang, Q.Y.; Guo, L.; Yi, J.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Q.; Fan, B.H.; Zhang, H.L. Influence of canopy and topographic position on soil moisture response to rainfall in a hilly catchment of Three Gorges Reservoir Area, China. J. Geog. Sci. 2020, 30(3), 949–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Wang, S.J.; Peng, T.; Zhao, G.Z.; Dai, B. Hydrological characteristics and available water storage of typical karst soil in SW China under different soil–rock structures. Geoderma 2023, 43, 116633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgarimehr, M.; Entekhabi, D.; Camps, A. Diurnal Vegetation Moisture Cycle in the Amazon and Response to Water Stress. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL111462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.R.; Zheng, J.H; Guan, J.Y.; Zhong, T.; Liu, L. Exploring the dominant drivers affecting soil water content and vegetation growth by decoupling meteorological indicators. J. Hydrol. 2024, 631, 130722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.W.; Yin, H.Y.; Chang, J.J.; Xue, J. Spatial variability of surface soil water content and its influencing factors on shady and sunny slopes of an alpine meadow on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 34, e02035. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, P.; Lin, K.R.; Wang, Y.R.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, X.; Tu, X.J.; Bai, C.M. Spatial interpolation of red bed soil moisture in Nanxiong basin, South China. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2021, 242, 103860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.B; Yang, Y.; Li, Z. ; Combined effects of multiple factors on spatiotemporally varied soil moisture in China’s Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manage. 2021, 258, 107180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S.Q.; Guo, L.; Liu, H.C.; Wu, X.M.; Lan, P.; Boyer, E.W.; Mello, C.R.; Li, H.X. Spatiotemporal dynamics of soil moisture and the occurrence of hysteresis during seasonal transitions in a headwater catchment. Geoderma 2025, 454, 117169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.Y.; Yang, Y.P. ; Spatial-temporal variability pattern of multi-depth soil moisture jointly driven by climatic and human factors in China. J. Hydrol. 2023, 619, 129313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lai, H.X.; Li, Y.B.; Feng, K.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Tian, Q.Q.; Zhu, X.M.; Yang, H.B. Dynamic variation of meteorological drought and its relationships with agricultural drought across China. Agric. Water Manage. 2022, 261, 107301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Shi, Y. Changes in surface wind speed and its different grades over China during 1961–2020 based on a high-resolution dataset. Int. J. Climatol. 2021, 42, 3954–3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Jing, H.F.; Guo, X.X.; Dou, B.Y.; Zhang, W.S. Analysis of Water and Salt Spatio-Temporal Distribution along Irrigation Canals in Ningxia Yellow River Irrigation Area, China. Sustainability 2023, 15(16), 12114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marukatat, S. Tutorial on PCA and approximate PCA and approximate kernel PCA. Artif Intell Rev. 2022, 56, 5445–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, P.S.; Patley, S.; Choudhary, B.; Gupta, S. Assessment and Comparison of Soil Quality Using Principal Components Analysis (PCA) & Expert Opinion (EO) Methods in different Rice-based Cropping Systems in Alfisol. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13(12), 869–887. [Google Scholar]

- Jaswal, R.; Sandal, K.S. Effect of Conservation Tillage and Irrigation on Soil Water Content, Shoot-Root Growth Parameters and Yield in Maize (Zea mays)-Wheat (Triticum aestivum) Cropping Sequence. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2024, 24(4), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.K. Book review: Christoph Molnar. 2020. Interpretable Machine Learning: A Guide for Making Black Box Models Explainable. Metamorphosis 2024, 23, 92–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.Q.; Chai, H.Z.; Wang, Z.H.; Pu, D.D.; Zhang, Q.K. Research on GNSS-IR soil moisture retrieval based on random forest algorithm. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 105108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Jiang, H.W.; Han, G.S. Multiscale adaptive multifractal cross-correlation analysis of multivariate time series. Chaos Solitons Fract. 2023, 174, 113872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Y.; Yang, X.Z.; Liu, C.; Yang, N.; Yu, G.D.; Zhang, Z.T.; Chen, Y.W.; Yao, Y.F. ; Hu. X.T. Monitoring soil moisture in winter wheat with crop water stress index based on canopy-air temperature time lag effect. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.Z.; Zhang, G.H.; Wang, H.X.; Zhang, B.J.; Liu, Y.N. Soil moisture variations in response to precipitation properties and plant communities on steep gully slope on the Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manage. 2021, 256, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Xiao, Z.N.; Wei, J.H.; Wang, G. The Seasonal and Diurnal Variation Characteristics of Soil Moisture at Different Depths from Observational Sites over the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2022, 14(19), 5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.R.; Gao, J.H.; Zhang, Y.B.; Li, F.P.; Man, W.D.; Liu, M.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Li, M.Q.; Zheng, H.; Yang, X.W.; Li, C.J. Estimation of Soil Organic Carbon Content in Coastal Wetlands with Measured VIS-NIR Spectroscopy Using Optimized Support Vector Machines and Random Forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.S.; Li, X.; Xie, Y.H.; Li, F.; Hou, Z.Y.; Zheng, L. Combined influence of hydrological gradient and edaphic factors on the distribution of macrophyte communities in Dongting Lake wetlands, China. Wetlands Ecol. Manage. 2015, 23, 481–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.X.; Yuan, L.M.; Meng, Z.J.; Zhang, E.Z.; Zhu, L.; Liu, J.W. Soil moisture partitioning strategies in blowouts in the Hulunbeier grassland and response to rainfall. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2025, 12, 1519807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.S.; Ouyang, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. Sharhuu, A.; Tseren-Ochir, S.E.; Yang, Y. Revisiting snowmelt dynamics and its impact on soil moisture and vegetation in mid-high latitude watershed over four decades. Agric. Forest. Meteorol. 2025, 362, 110353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.Z.; Qiu, Z.J.; Zhou, G.Y.; Zuecco, G.L.; Liu, Y.; Wen, Y. Soil water hydraulic redistribution in a subtropical monsoon evergreen forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 835, 155437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugathan, N.; Biju, V.; Renuka, G. Influence of soil moisture content on surface albedo and soil thermal parameters at a tropical station. J. Earth Syst. Sci. 2014, 123, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Liu, D.P.; Li, T.X.; Fu, Q.; Liu, D.; Hou, R.J.; Meng, F.X.; Li, M.; Li, Q.L. Responses of spring soil moisture of different land use types to snow cover in Northeast China under climate change background. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.W.; Liu, G.H.; Liu, Q.S.; Huang, C.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.H. Seasonal variation of deep soil moisture under different land uses on the semi-arid Loess Plateau of China. J. Soils Sediments. 2019, 19, 1179–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H.; Kim, S.H. Spatiotemporal soil moisture response and controlling factors along a hillslope. J. Hydrol. 2022, 605, 127382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Li, M.J.; Wu, Y.; Ma, X.Y.; Song, Q.H.; Zhang, Y.P.; Su, Y.; Ni, J.J.; Dong, J.Z. Identification of varied soil hydraulic properties in a seasonal tropical rainforest. Catena 2022, 212, 106104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Yuan, Z.; Shi, X.L.; Yin, J.; Chen, F.; Shi, M.Q.; Zhang, F.L. Soil moisture content-based analysis of terrestrial ecosystems in China: Water use efficiency of vegetation systems. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, R.N.; Liang, M.; Ma, J.F.; Yang, Y.Z.; Zheng, H. Impact of crop types and irrigation on soil moisture downscaling in water-stressed cropland regions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 100, 107073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.B; Zhan, H.B.; Yang, W.B.; Bao, F. Deep soil water recharge response to precipitation in Mu Us Sandy Land of China. Water Sci. Eng. 2018, 11, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.Z.; Kong, X.Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, H.B.; Wang, C.W.; Ma, S.A. Effects of Conservation Tillage on Soil Properties and Maize Yield in Karst Regions, Southwest China. Agriculture 2022, 12(9), 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.X.; Zhao, C.C. Impact of Different Yearly Rainfall Patterns on Dynamic Changes of Soil Moisture of Fixed Sand Dune in the Horqin Sandy Land. IOP Conf. Ser: Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 234, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.J.; Wan, L.; Cui, M.; Wu, B.; Zhou, J.X. Influence of Canopy Interception and Rainfall Kinetic Energy on Soil Erosion under Forests. Forests 2019, 10(6), 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Lv, X.Z.; Yu, X.X.; Ni, Y.G.; Ma, L.; Liu, Z.Q. Species and spatial differences in vegetation rainfall interception capacity: A synthesis and meta-analysis in China. Catena 2022, 213, 106223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cao, S.L.; Sun, Z.H.; Wang, H.Y.; Qu, S.D.; Lei, N.; He, J.; Dong, Q.G. Tillage effects on soil properties and crop yield after land reclamation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.W.; Pan, C.Z.; Sun, Y.H.; Chen, Z.J.; Xiong, Y.W.; Huang, G.H. Impact of Land Use Conversion on Soil Structure and Hydropedological Functions in an Arid Region. Land Degrad Dev. 2024, 36(2), 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, M.; Si, B.C.; Feng, H. Deep rooted apple trees decrease groundwater recharge in the highland region of the Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 622-623, 584–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wei, W.; Chen, L.D. Effects of terracing practices on water erosion control in China: A meta-analysis. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 173, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, W.; Sun, X.H.; Ma, J.J.; Guo, X.H.; Lei, T.; Li, R.F. Measurement and simulation of the water storage pit irrigation trees evapotranspiration in the Loess Plateau. Agric. Water Manage. 2019, 226, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, F.; Qin, D.J.; Zhao, Z.F.; Gan, F.P.; Yan, B.K.; Bai, J.; Muhammed, H. Hydrodynamic characteristics of a typical karst spring system based on time series analysis in northern China. China Geology 2021, 4(3), 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler-White, J.L.; Knapp, A.K.; Kelly, E.F. Increasing precipitation event size increases aboveground net primary productivity in a semi-arid grassland. Oecologia 2008, 158, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bao, Z.X.; Wang, G.Q.; Liu, C.S.; Xie, M.M.; Wang, B.; Zhang, J.Y. The Time Lag Effects and Interaction among Climate, Soil Moisture, and Vegetation from In Situ Monitoring Measurements across China. Remote Sens. 2024, 16(12), 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Lu, J.Z.; Chen, X.L. A novel comprehensive agricultural drought index reflecting time lag of soil moisture to meteorology: A case study in the Yangtze River basin, China. Catena 2022, 209, 105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Name | Longitude (°E) | Latitude (°N) | Soil Texture | Plant Type |

| 1 | Dongting Lake | 113.17 | 29.32 | 13%、82%、5% | Camellia oleifera |

| 2 | Guyuan | 115.68 | 41.76 | 7%、37%、56% | Grassland |

| 3 | Guangzhou | 113.64 | 23.25 | 5%、56%、39% | Grassland |

| 4 | Haibei | 101.31 | 37.61 | 7%、83%、10% | Grassland |

| 5 | Hefei | 117.17 | 31.9 | 11%、81%、8% | Rice |

| 6 | HulunBuir | 119.99 | 49.22 | 11%、57%、32% | Grassland |

| 7 | Jiangshanjiao | 128.95 | 43.86 | 32%、41%、27% | Forest Land |

| 8 | Jingyuetan | 125.62 | 44.79 | 10%、53%、37% | Corn |

| 9 | Minqin | 102.92 | 38.63 | 1%、11%、88% | Desert control |

| 10 | Nagqu | 92.01 | 31.64 | 11%、84%、5% | Grassland |

| 11 | Nanjing | 119.21 | 31.5 | 7%、61%、32% | Tea Plantation |

| 12 | Qiyang | 111.87 | 26.76 | 17%、74%、9% | Tea Plantation |

| 13 | Qianyanzhou | 115.07 | 26.75 | 25%、39%、36% | Grassland vegetation |

| 14 | Qingdao | 120.18 | 35.95 | 7%、55%、38% | Pine trees and fruit trees |

| 15 | Western Tianshan | 81.17 | 43.74 | 7%、59%、34% | apple |

| 16 | Xilinhaote | 116.33 | 44.14 | 8%、37%、54% | Grassland vegetation |

| 17 | Yucheng | 116.57 | 36.83 | 32%、56%、12% | Corn-Wheat Rotation |

| 18 | BayanNur | 107.22 | 40.73 | 32%、50%、18% | Corn |

| 19 | Daan | 123.85 | 45.6 | 28%、45%、27% | Grassland,saline-alkali soil |

| 20 | Deqing | 120.19 | 30.57 | 38%、33%、29% | Rice |

| 21 | Heihe | 100.32 | 38.77 | 36%、53%、11% | Sandy Grassland |

| 22 | Kanas | 87.02 | 48.1 | 31%、51%、18% | Grassland |

| 23 | Luancheng | 114.69 | 37.89 | 29%、50%、21% | Winter wheat –Corn rotation |

| 24 | Xiamen | 118.07 | 24.78 | 38%、33%、29% | Corn |

| 25 | Shangqiu | 115.59 | 34.52 | 31%、47%、22% | Corn |

| 26 | Shouyang | 113.2 | 37.75 | 32%、54%、14% | Corn |

| 27 | Turufan | 89.2 | 42.85 | 17%、78%、5% | Sandy Grassland |

|

Meteorological Factors |

Factor Loading | Communality | ||

| Principal Component 1 | Principal Component 2 | Principal Component 3 | ||

| T (℃) | 0.967 | 0.179 | 0.163 | 0.983 |

| Tmax (℃) | 0.981 | 0.098 | 0.117 | 0.977 |

| Tmin (℃) | 0.925 | 0.269 | 0.207 | 0.957 |

| P (mm) | -0.336 | 0.855 | 0.249 | 0.729 |

| U(m/s) | -0.490 | -0.408 | 0.768 | 0.548 |

| Rn (J/m2/d) | 0.641 | -0.672 | -0.006 | 0.677 |

| climatic zones | T (℃) | Tmax(℃) | Tmin (℃) | P (mm) | U (m/s) | Rn(J/m2/d) |

| Tropical Monsoon | 0.196 | 0.192 | 0.186 | 0.191 | 0.047 | 0.184 |

| subtropical monsoon | 0.199 | 0.198 | 0.183 | 0.170 | 0.100 | 0.146 |

| temperate monsoon | 0.191 | 0.189 | 0.184 | 0.184 | 0.080 | 0.168 |

| temperate continental | 0.198 | 0.196 | 0.193 | 0.191 | 0.030 | 0.187 |

| alpine plateau climates | 0.221 | 0.215 | 0.215 | 0.170 | 0.015 | 0.162 |

| Mean | 0.201 | 0.198 | 0.192 | 0.181 | 0.055 | 0.169 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).