Giorgio Agamben defines archaeology as the identification of “signatures” that shape how disciplines construct and perpetuate meaning. These marks, inherited from historical tensions, continue to structure contemporary regimes of truth (Agamben 2019, p. 44). Taking up and extending the archaeology proposed by Michel Foucault, Agamben emphasises the relevance of this method for understanding the devices that organise contemporary experience and the regimes of truth that accept or exclude certain practices of knowledge. In this sense, the archaeological task is not limited to a work of historical excavation, but is presented as a critical method for thinking about knowledge - such as theology - in its constitutive relationship with the exercise of power and its possibilities for re-signification in the present.

While Luhmann describes knowledge systems as self-referential, Foucault shows that knowledge is always embedded in power relations that define what can be said and thought, through mechanisms of control, exclusion and disciplining of speech (Foucault 1971). There is no knowledge that is completely autonomous, because its conditions of possibility are historically determined by the power games that determine what can be said and thought at any given time.

From this perspective, social systems cannot be understood as operationally closed in an absolute way, because each system is constantly traversed by an order of speech that determines what can and cannot be legitimated as knowledge. This order is not only contingent, but is structured by power relations that determine which propositions are accepted because they are “in the true” (Foucault 2010, p. 224) and which are excluded. In a Foucauldian approach, the self-referentiality of a system such as the scientific system is ultimately an illusion, because all knowledge is produced in a field of forces that includes political, economic and cultural tensions that shape its historical conditions of possibility. Scientific practices cannot be separated from the social and political practices that allow them to operate.

In addition, Foucault pays particular attention to the discontinuities between different epochs, that is, the moments when forms of knowledge power are radically restructured by changes in discursive practices and their relationship to non-discursive practices. The production of knowledge is always traversed by practices of power and resistance that cannot be explained solely by self-referential mechanisms internal to systems.

In the specific case of theological knowledge, a fundamental problem in the structural coupling with modern universities lies in the divergence between two regimes of rationality: while the scientific system that governs the university is guided by a public rationality, contemporary theology remains largely referenced by a confessional rationality based on revelation. This emphasis on revelation as the ultimate criterion of truth can be interpreted as a symptom of the historical conditions of possibility that have shaped the place of the religious system in modern societies and partly explain its current epistemological marginality. Yet historically, theology emerged as a public discourse intertwined with philosophy and public reason. The reduction of theology to fundamental theologies centred on Revelation reinforces epistemic self-enclosure, despite efforts to reinterpret Revelation in dialogue with modern experience. (Rahner 1941; 1984; Ratzinger 1969; Latourelle 1966; Gutiérrez 1971; Libanio 1992; Tillich 1951–1963; Pannenberg 1961; Geffré 1972; O’Collins 2016; Theobald 2001, among others).

Theology must be translated into the language of public rationality to contribute to citizenship and the common good, without abandoning its confessional roots (Tracy 1996). However it does demand a rigorous translation and a broadening of its epistemological understanding, so that it can fit better in the mission of modern universities to promote the formation of citizens’ critical conscience and contribute to the common good.

In contrast to the logic of self-referentiality, Francis used the metaphor of the polyhedron to describe theology as polyphonic—open to diversity, yet united in dialogue and oriented to the common good (Francis 2017, n. 3). Foucault similarly speaks of a “polyhedron of intelligibility,” where knowledge is structured by multiple, irreducible relations. The analysis of a field of knowledge requires taking into account the multiplicity of relations that make it up, forming a polyhedron whose faces are not given in advance and whose complexity cannot be completely reduced to a single point of view (Foucault 2001, p. 227).

On the same horizon, Michel de Certeau—identified by Pope Francis as a major influence (La Civiltà Cattolica 2013; IHU online 2013)—proposed to think about an “archaeology of the religious” (archéologie religieuse) in which the religious element functions as a matrix of intelligibility. In L’écriture de l’histoire, he argued that modern historiography does not entirely break with the religious, but rather reinscribes the experience of alterity and absence—God, the Other—into secular modes of knowledge (Certeau 1975, p. 121).

The task of an archaeology of theological knowledge thus acquires a critical and plural character. It involves reflecting on theology’s entanglement with knowledge, society, and power, identifying the multiple genealogies that shape its discourse, and overcoming epistemic self-referentiality to contribute to a public theology in dialogue with contemporary rationality—particularly as it emerges within the human sciences.

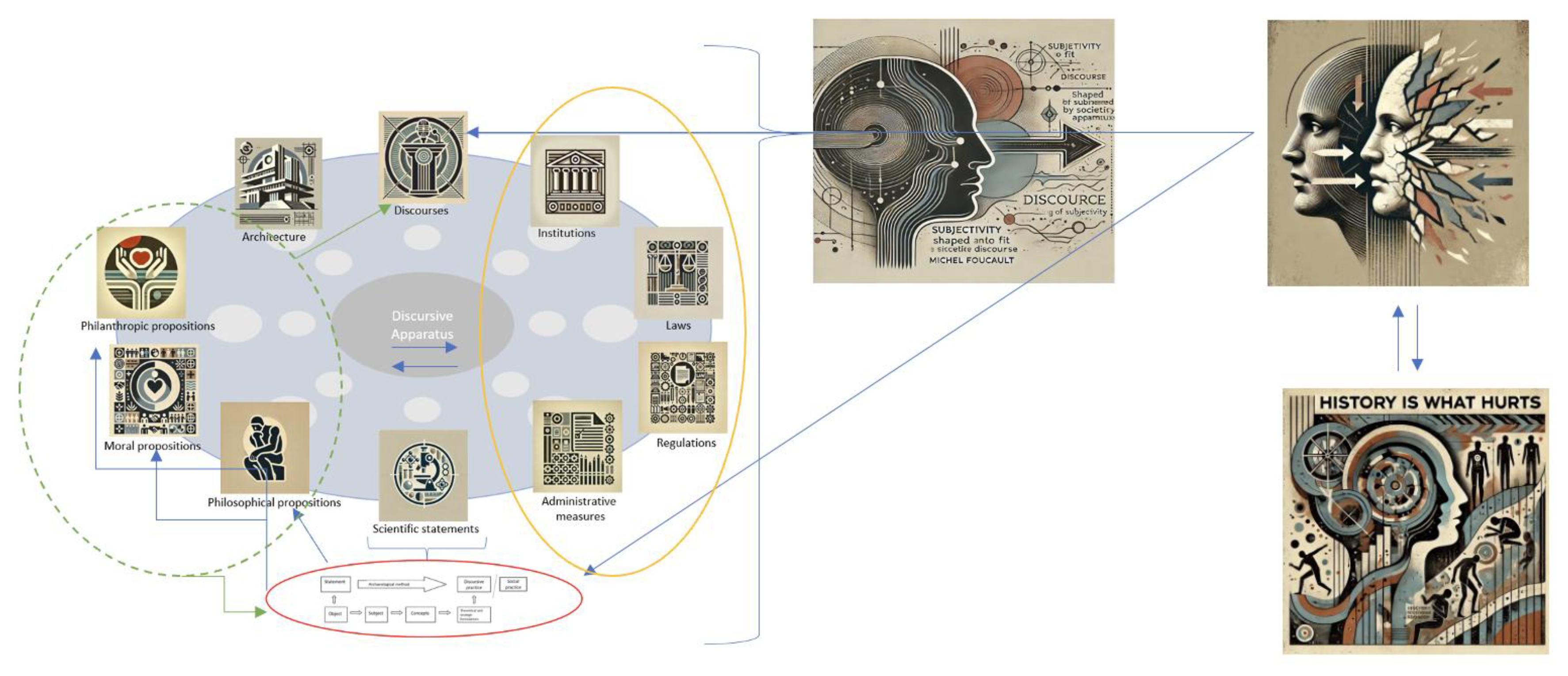

In this way, the archaeo-genealogical toolbox is employed here to illuminate the historical and relational conditions underlying the emergence of public theology through three complementary dimensions: (1) the archaeology of knowledge, (2) the genealogy of power apparatuses, and (3) the genealogy of ethics or processes of subjectivation—each contributing to the analysis of theology’s epistemic displacement.

3.1. The Trajectory of Michel Foucault’s Archaeological Method

In order to outline an archaeology of theological knowledge, it is first necessary to understand some aspects of the first moment of Foucault’s analyses, corresponding to the trajectory of the archaeological method, and its relation to the second moment of his thought, when the refined elaboration of the genealogical method takes place.

In a broad sense, the archaeological analysis does not aim to search for an origin or a history of ideas, but rather to systematically describe the birth of a discourse-object based on enunciative regularities between different types of knowledge in the same long period of time, which come to share an enunciative homogeneity, forming a kind of bundle of discursive relations. To understand this point of arrival for the archaeology of knowledge, it is necessary to elucidate its trajectory.

Foucault’s archaeological project in the 1960s is exemplified by History of Madness (1961), where he explores how different periods constructed the perception of madness as a cultural and institutional phenomenon. In The Birth of the Clinic (1963), he extends this analysis to medical discourse, showing how the shift from metaphysical to empirical observation in the late 18th century transformed clinical practice. This transition—from symptom to lesion, from theory to anatomical gaze—illustrates how knowledge is shaped by institutional practices. Ultimately, Foucault links this evolution to the emergence of biopower and the modern control of bodies through medical authority.

Finally, his last archaeological exercise, known as Opus Magnum, led to the publication of

Les mots et les choses (literally

words and things)

2, whose subtitle also indicates the object of its excavation, namely

An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (1966). The book deals with the discursive formation that led to the emergence of this field of knowledge in the nineteenth century, which, according to the French philosopher, consisted mainly of the social sciences, psychology and literature, from the opening to positivity of the finitude of the human being not only as a transcendental subject in Kantian philosophy, but above all as an empirical object, making it possible to grasp him not only as the subject of his reflection, but also as his own object. It is here that Foucault analyses the formation of knowledge and its historical conditions of existence, and the way in which discourses articulate words and things in modernity, no longer governed by the notion that words merely reveal and represent the already given meaning of things.

It is only in this 1966 book that the centrality of knowledge is acknowledged, through the intersection of its philosophical and empirical perspectives, between which a synchronic continuity is identified (for example, in the perspective of finitude that runs through biology, political economy and philology in modernity) and a diachronic discontinuity (the reconfiguration of the relationship between words and things in the sphere of knowledge, based on the change in the archaeological network in which they are found). The archaeology of knowledge in Les mots et les choses aims to identify the limits of what is thinkable in a given culture - in this case, Western European culture. To do this, Foucault turns to literature to show the extent to which an order of knowledge that does not belong to our cultural codes of apprehension provides an almost complete alienation. And yet these codes, which are completely different from ours, have a way of being understood in the archaeological soil in which they were built.

Foucault’s decision to pursue the archaeology of the human sciences was inspired by Borges’ fictional taxonomy, which revealed the self-referential nature of Western categories of thought. It refers to an entry on animals in a “certain Chinese encyclopaedia”:

‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies’. (2008, Preface, p. XVI)

The philosopher commented on the impression the poem made on him when he realised that Western thought was in danger of thinking variations on the same thing. Said the French Philosopher:

“In the wonderment of this taxonomy, the thing we apprehend in one great leap, the thing that, by means of the fable, is demonstrated as the exotic charm of another system of thought, is the limitation of our own, the stark impossibility of thinking that. (2008, Preface, p. XVI)”

In this way, the archaeological task can be seen as a way of forming a theoretical toolbox to identify forms of self-referentiality.

Furthermore, in the preface to The Order of Things, Foucault makes it clear that his aim is not to tell a chronological history of the human sciences, but to reveal the networks of thought that have shaped knowledge in different periods. He defines this as ‘archaeology’, as he digs beneath historical surfaces to find the underlying rules that organise discourses and forms of knowledge that are taken for granted by the subjects of the time. In this way, the French philosopher aims to identify the rules of speech that organise and legitimise what can be said and thought as scientific in a given period.

Michel Foucault’s archaeological task, then, was to progressively understand and describe what he called the episteme, that is, the set of historical rules that, at a given time, establish the conditions of possibility for a field of scientific knowledge, leading to the emergence of the so-called ‘human sciences’. The episteme is not simply a body of knowledge or a set of ideas; it is the invisible and underlying structure that determines what can be known, thought and said at a given time, even before knowledge is organised into specific disciplines. Episteme can be understood as an “a priori is what, in a given period, delimits in the totality of experience a field of knowledge, defines the mode of being of the objects that appear in that field” (Foucault 2005a, p. 158).

The archaeological method is based on the rules or historical a priori that define what knowledge is for each era. It is a ‘network of knowledge’ that connects all areas of knowledge in and influences the forms of truth that are accepted in a period. The episteme is not conscious, but it is the background that shapes the knowledge of an era, allowing certain concepts to make sense while others do not. Each specific piece of knowledge (savoir) needs to relate to this network of foundational knowledge (connaissance).

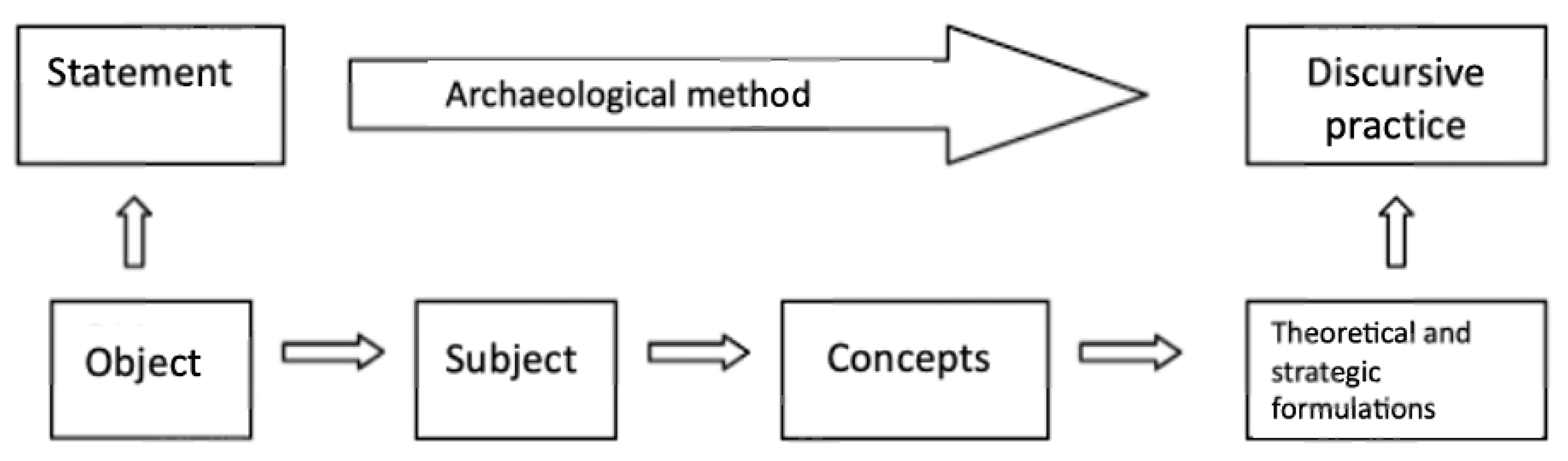

In

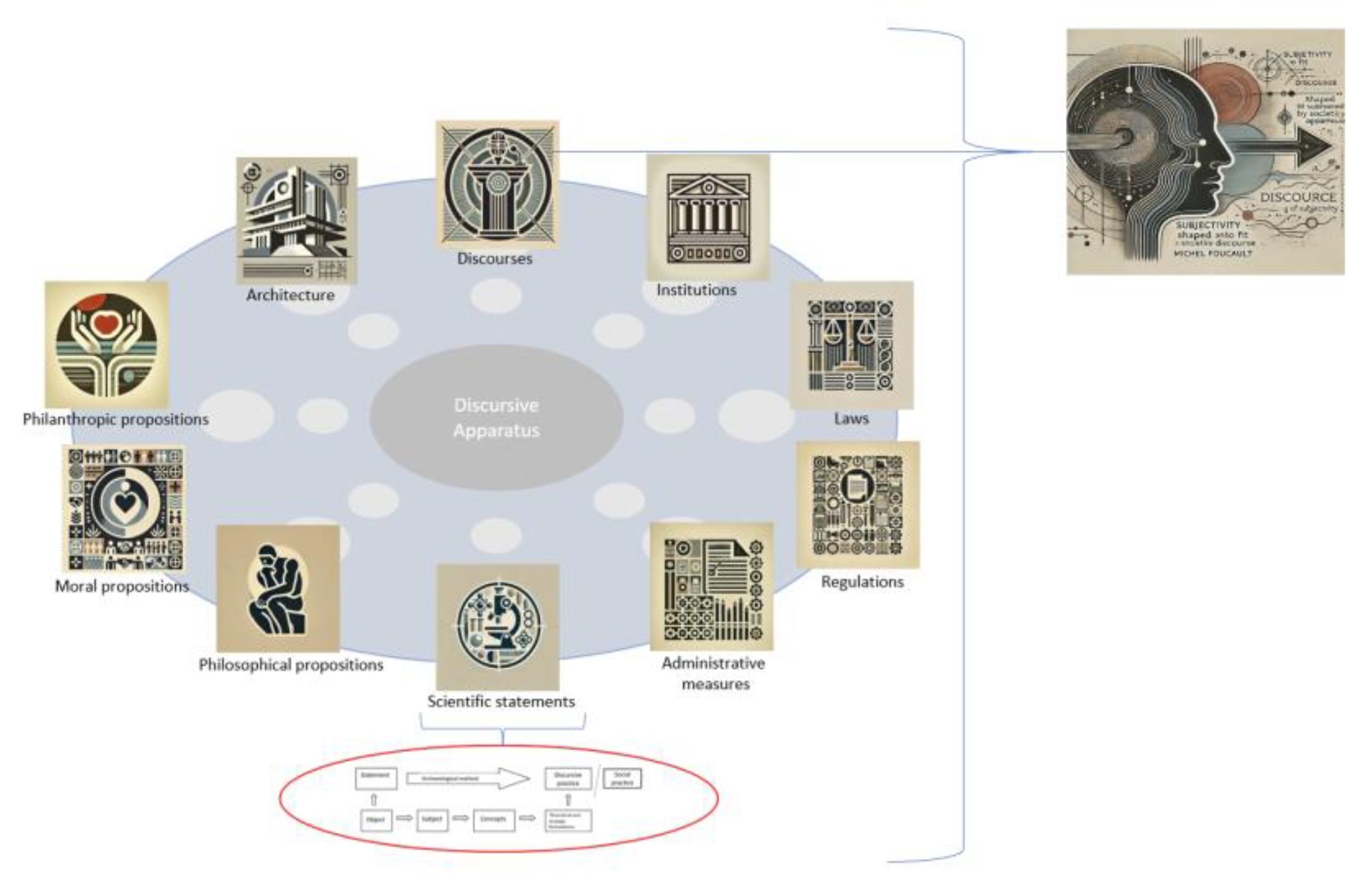

The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969), Foucault outlines a method for analysing the historical conditions that make knowledge possible in different periods. Rather than seeking the origin of ideas or the intentions of authors, archaeology focuses on analysing the discursive practices and regularities that govern the constitution of knowledge. This archaeology is structured around four elements—Object, Subject, Concepts, and Strategies—understood not as fixed entities, but as relational functions within a discursive field. These are articulated through the statement (

énoncé), the method’s basic unit—not a sentence, but a discursive function that enables something to be said meaningfully within specific institutional and historical conditions. A statement does not exist in isolation: it is situated within a set of rules that determine who can speak (subject), what may be spoken about (object), with which conceptual tools (concepts), and under what strategic conditions or power relations (strategic formulations). The statement is the intersection of these four dimensions, allowing discourse to emerge meaningfully within a given historical configuration (see

Figure 1). The archaeologist’s task is to describe this field of statements and to uncover the rules that govern their formation, transformation, and exclusion.

The object emerges within a statement, shaped by the discursive practices that define its properties and modes of existence. The subject is likewise positioned by the statement; there is no subject prior to it, only subject positions determined by what may be said. Concepts are mobilised and structured through statements, defining fields of reference, intelligibility, and regimes of truth. Finally, strategies determine the effects of statements, assigning them a role within a field of knowledge-power and situating them in ongoing struggles and relations of force.

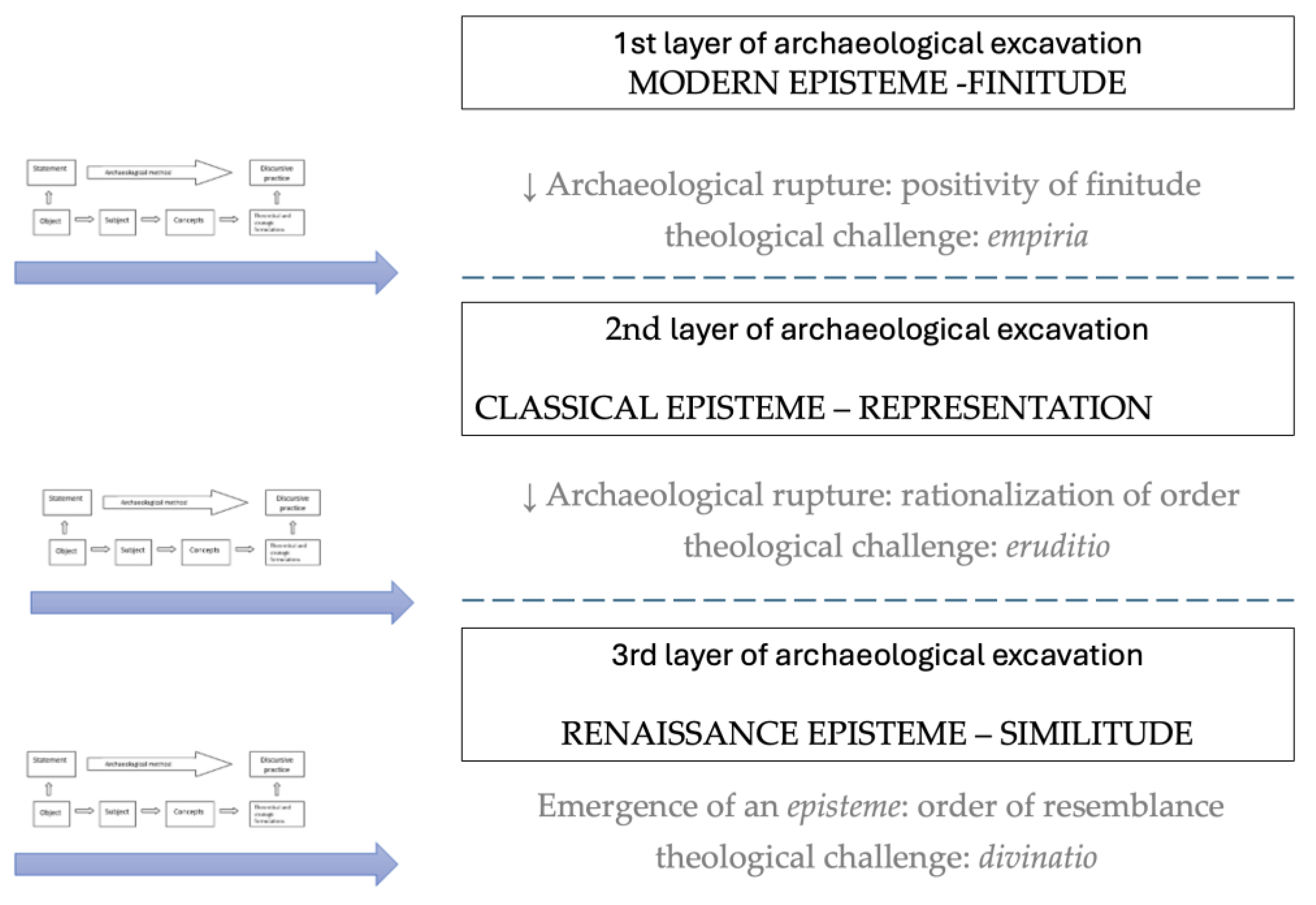

The French philosopher emphasizes discontinuities and ruptures that allow new rules for the emergence of a new understanding of what scientific knowledges is, at least in three periods. These epistemic configurations do not follow a linear progression but rather mark historical thresholds that redefine the historical conditions of possibility of knowing. Although Foucault did not analyse theology, the emergence of a new configuration in this set of rules obviously has repercussions for theology by changing the scenario of knowledge production in an era: 1) From Antiquity to the Renaissance, knowledge was organized around the principle of

resemblance. Words aimed to reflect the relationships between things, understood as signs inscribed in a cosmos that could be deciphered. This way of knowing can also be associated with the ancient

divination (Foucault 2005a, p. 36-37; 65-66), a contemplative and symbolic mode that presupposes a world animated by divine traces, where meaning is revealed through analogies, correspondences, and

signatures, in which nature is in the form of being deciphered by the human being, a mode of knowledge oriented toward the perception of beauty (

thaumazein) in the order of things. It was the first theological challenge of transposing the narrative theology of the Semitic tradition into the rules of knowledge production elaborated by the ancient Greeks. Without this transposition, dialogue with the Greco-Roman world would not have been possible; 2) The Classical period (17th century until the transition to the 19th century), as named by Foucault and influenced mainly by Descartes, marks a rupture in which thought separated words from things in order to create a rational, unchanging order of

representation. Language became a transparent medium to structure and classify reality. This period directly influences the second scholasticism, both Catholic and Protestant, in which one can identify a shift in the way the figure of God is associated with the rules of knowledge production. In this sense, God ceases to be analysed through things and begins to inhabit the world of scholastic

eruditio (Foucault 2005a, p. 37) characterised by a systematic and taxonomic approach to knowledge, a rationality in which erudition places the idea of God in an exercise of abstraction that aspires to universality and epistemic clarity; 3) In the

Modern period, which replaces the classical episteme, knowledge is primarily structured by the emergence of

finitude as a historical and epistemological condition. According to Foucault, this marks a radical shift: the archaeology of knowledge breaks with the philosophical narrative that interprets the birth of the human sciences as a progressive unfolding of the idea of human nature. Instead, the modern episteme is grounded in history itself, whereby the finitude of human nature is no longer seen negatively in contrast to the perfection of the divine infinite but rather becomes the central positive datum around which knowledge is organized. This regime is defined by the constitution of “man” as both subject and object of knowledge — a figure that arises not from the metaphysical continuity of the Enlightenment, but from a series of discontinuous discourses: philosophical (notably in Kant), and empirical (philology, political economy, biology). In this configuration, empirical methods do not merely provide observational tools; they articulate the historicity and limits of human knowing. This period thus corresponds to the emergence of the modern ‘man’ as an empirical-transcendental figure, essential for the notion of

finitude (Foucault 2005a, p. 357s). Thus, for scholastic theology,

modernitas meant

empiria, a challenge to think of the theological tradition beyond metaphysical

eruditio about life, but from an analysis of finitude and its basic dimension of

empiricism situated in the concrete conditions of human life, as a way of engaging with the positivity of finitude, the most decisive event in the modern order of knowledge (

Figure 2).

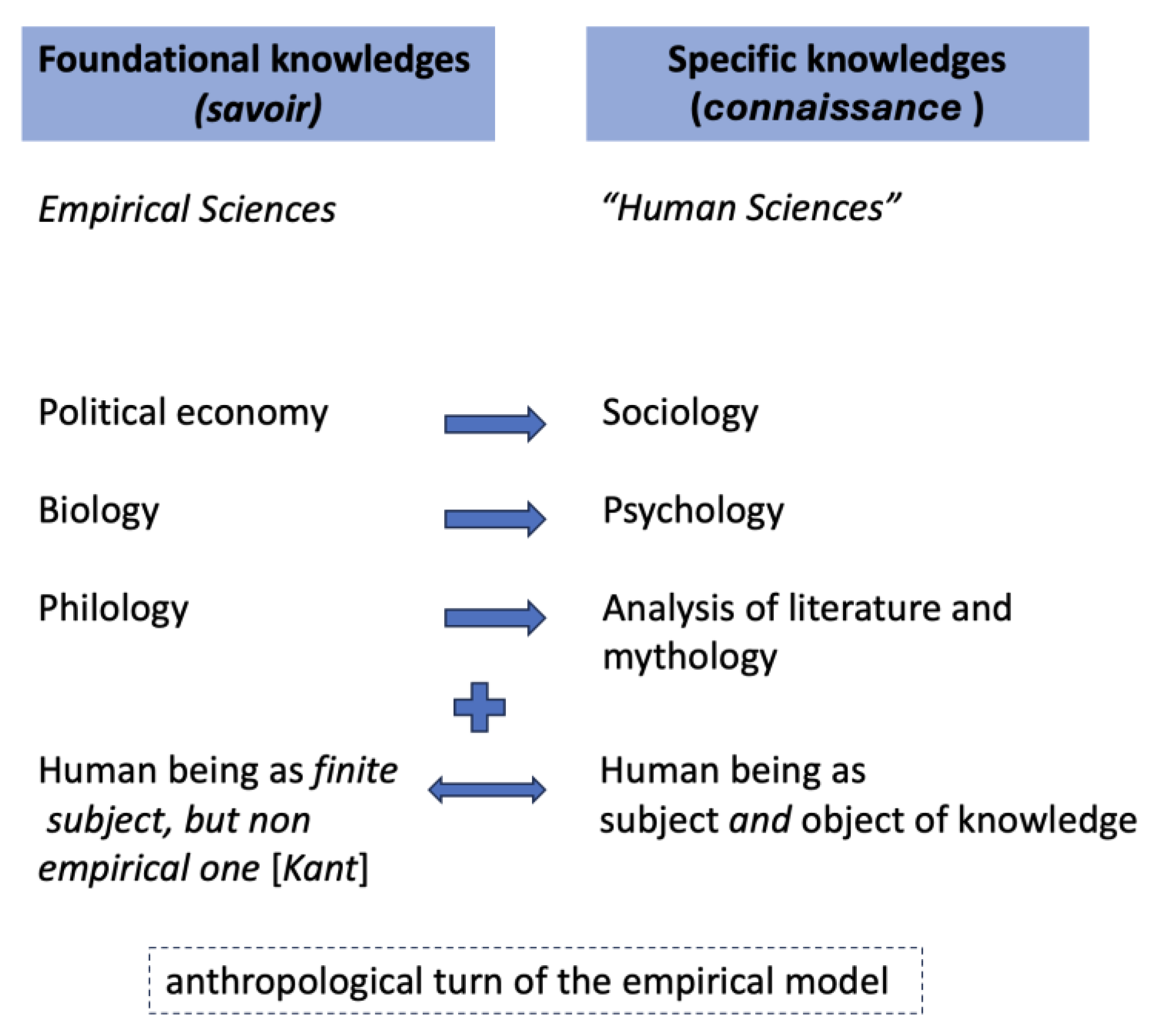

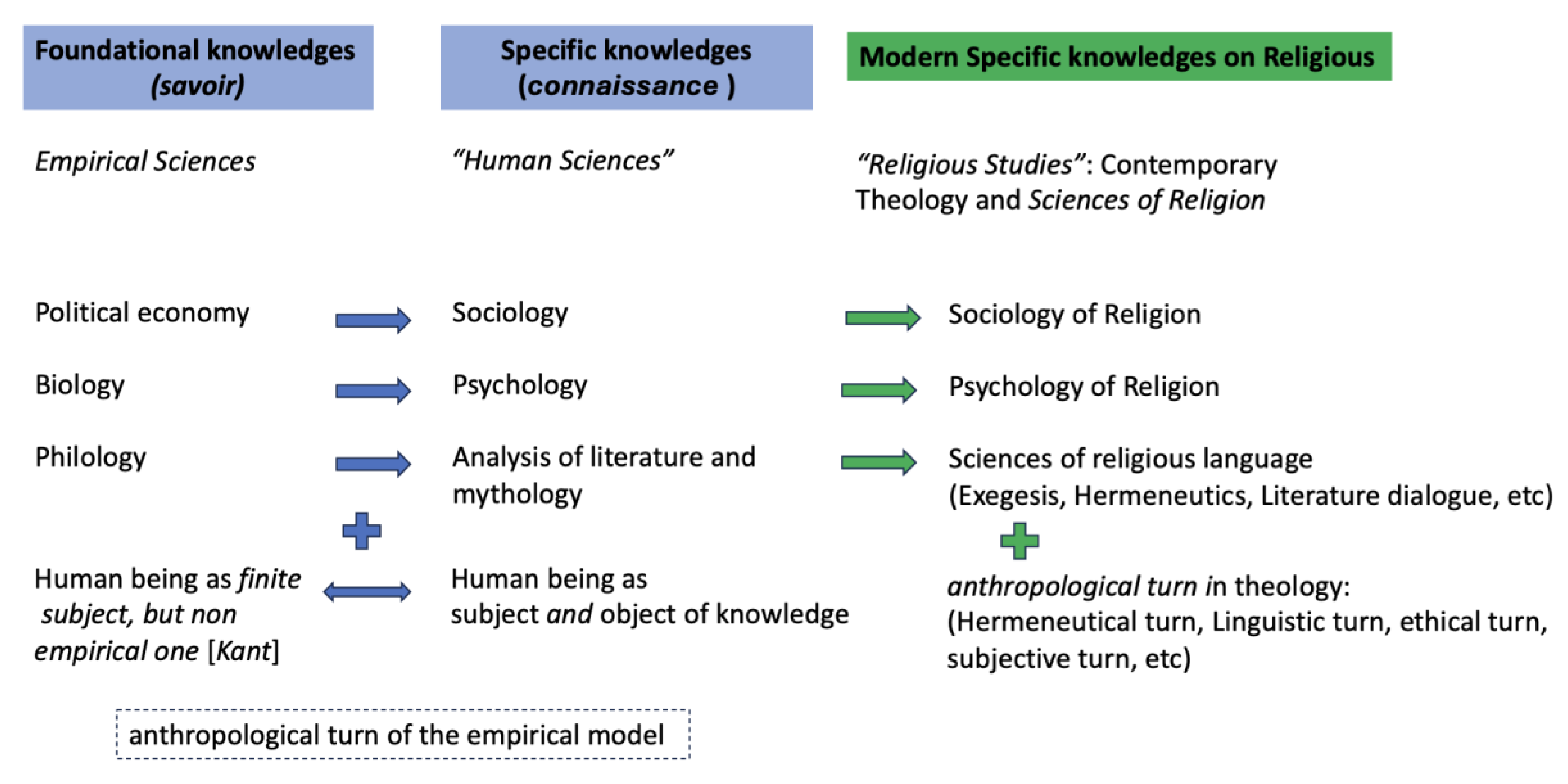

In this sense, the human sciences simultaneously become a specific knowledge in harmony with the set of fundamental knowledges that shape the meaning of modern science. It means human sciences is scientific knowledge from its connection with the empirical basis of thought.

In other words, the human sciences emerged from the insufficient use of language from metaphysics in translating the empiric model to a cultural perspective. They were responsible for shaping the subjectivity of the modern individual. Human sciences emerged as an anthropological turn in empirical knowledge, transforming the human being not only into an object, but also into a subject of their own knowledge.

If, at the empirical level, it is political economy (labor), biology (life), and philology (language) that discover finitude in a more radical manner, at the philosophical level it is Kant’s philosophy that opens the way to a “finite subject” (

Figure 3). In fact, Kant creates a transcendental field in which the finite subject (because it is deprived of the intellectual intuition of metaphysics), but which is not empirical (because it is not given in experience, as in the empirical sciences), determines in its relation to any objects the formal conditions of experience in general (Foucault 2010, p. 264), and thus carries out a synthesis between representations. In contrast, and without paying attention to this Kantian distinction between the empirical and the transcendental subject, modern philosophy - especially positivism, dialectics and phenomenology - sought to identify in the empirical subject of the sciences of life, work and language the transcendental conditions of experience, thus inaugurating modern anthropologism through the ‘confusion’ between the empirical and the transcendental. Modern man is thus, from his very origins, both empirical and transcendental-object of knowledge (as one who works, lives, and speaks) and, at the same time, condition of the possibility of this knowledge (as a transcendental subject whose finite categories of space and time make it possible to grasp the object, first through sensibility and then through the intellect, thus effecting a synthesis between representations). The human sciences are thus characterised as an anthropological turn of the empirical model of knowledge as an analytic of finitude.

3.1.1. The Relation Between Archaeological and Genealogical Methods

The genealogical method introduced by Michel Foucault deepens rather than ruptures his analysis of the historical conditions of knowledge and its entanglement with power, already evident in his 1970 inaugural lecture at the Collège de France, published as The Order of Discourse (1971). As Domingues (2023, p. 347) observes, the analytics of power was already implicit in the archaeological phase, as the emergence and legitimation of knowledge depend on external—especially political—conditions. Genealogy builds on this by tracing how truth is historically produced through such entanglements.

Foucault himself clarified this in 1984, distinguishing archaeology’s concern with rules of formation from genealogy’s focus on intersecting and transforming discursive practices:

“The analysis I was proposing was archaeological insofar as it was not intended to capture what was hidden, but to bring to light the play of rules that determine the appearance of statements as singular events. But it was also genealogical, in that it was not concerned with reconstituting formal successions, but with detecting discursive formations as multiple practices that intersect, repeat, transform, and sustain one another” [free translation] (Foucault 1984, p. 14).

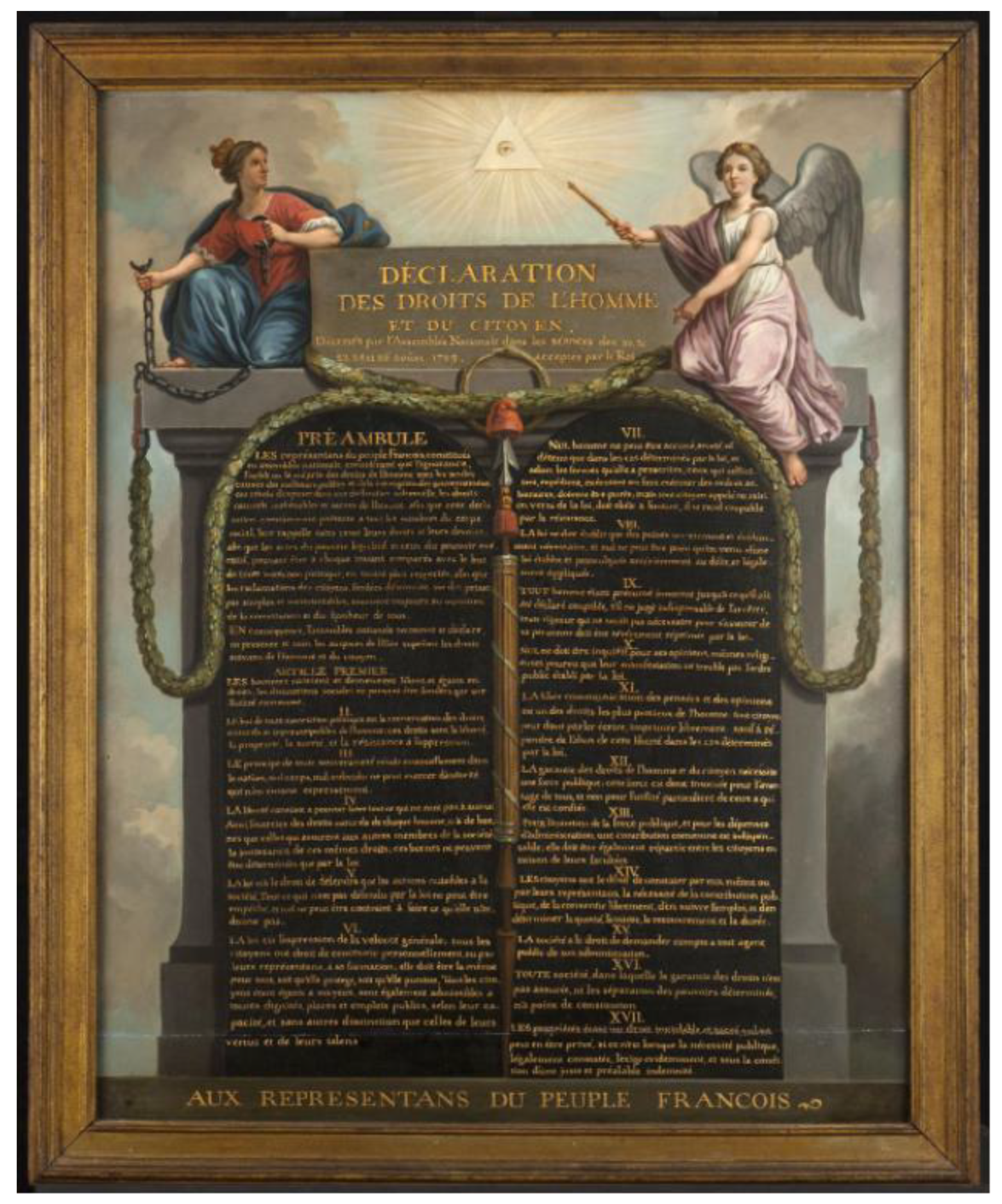

What was previously centered on the conditions of possibility for statements and discursive formations now also incorporates the relations of force that traverse and historically constitute those formations. Foucault’s metaphor of the ‘polyhedron of intelligibility’ illustrates this multidimensional character of knowledge-power formations. The polyhedron, with its multiple, open-ended facets, illustrates the multiplicity of relations that compose any historical formation of knowledge-power. For Foucault, understanding a historical event or process does not involve recovering its unique origin or a linear cause but tracing the multiple lines of force, knowledges, and practices that intersect in its constitution (1994, p. 24). This relates to the concept of apparatus (dispositif), a network of discourses, institutions, norms, practices and strategies that operate as mechanisms of power and knowledge in a society.

The genealogical method, which succeeds and complements archaeology, seeks to describe the emergence and transformation of these

apparatus, revealing how they organize conduct and produce subjectivities. While the archaeological method analyses the historical conditions of possibility for statements and knowledges within a discursive formation, genealogy investigates the correlations of force and strategies of power that sustain and modify such formations across knowledge fields. The polyhedron of intelligibility is thus a powerful image (

Figure 4) of this complex and dynamic analysis, one that resists reduction to a homogeneous totality and remains open to the multiple genealogies and apparatuses that shape regimes of truth and social practices.

In the late 1970s, Foucault introduced the concept of governmentality (gouvernamentalité) to analyze the emergence of modern political rationalities. Foucault aimed to analyze how the state became “governmental,” that is, how a rationality for governing others and oneself emerged (removed for peer review). This shift is traced from medieval advice to princes literature to early modern Stoicism, where spiritual counsel gave way to the arts of government (Foucault 2008, p. 281). This governmental rationality, however, does not emerge ex nihilo. Foucault identifies its deeper roots in Christian traditions of pastoral care, where governing individuals’ conduct—spiritually and morally—prefigures modern techniques of population management. This continuity becomes visible in his genealogy of pastoral power. This situation gave rise to a deep concern over “how one wishes to be spiritually guided on this earth toward salvation”—a transcendent issue that was, however, intimately tied to the immanent order of a Christianized society. In the sixteenth century, this became a structurally sensitive problem, as it threatened the cultural-religious unity that had sustained the social body. This tension encompassed a range of political questions inherently linked to the spiritual one: “how to be governed, by whom, to what extent, to what ends, and by what means?” (Foucault 2006, p. 282).

Foucault’s genealogy of pastoral power shows how Christian techniques of spiritual direction evolved into modern technologies for governing populations, emphasizing the production of truth and the constitution of subjectivities. This transformation is rooted in the emergence of centralized states and the religious upheavals of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, which reshaped the political and spiritual question of how people are to be governed—by whom, to what end, and with what means (Foucault 2006, p. 282). Rather than recovering the Stoic ideal of government as self-mastery, Foucault traces a distinctly Christian model of pastoral government: a form of power exercised by the clergy over a mobile flock, formalized after the Council of Trent through the creation of seminaries (Foucault 2008, p. 224).

Unlike Greek and Stoic traditions, where leadership was tied to territory and self-governance, and unlike Judaism, where God alone is shepherd of his people (Foucault 2006, pp. 358–359), Christian pastoralism implies guiding individuals toward salvation through structured obedience and confession (Foucault 2008, p. 168). Two central mechanisms define this model: total obedience—requiring the renunciation of personal will—and exhaustive confession, aimed at extracting inner truths (Foucault 2008, p. 196). These mechanisms converge in the practice of spiritual direction, in which truth is produced through verbalized self-examination under the interpretative authority of a director. This dual regime of truth—revelation and confession—is institutionalized under surveillance (Foucault 2008, p. 8), producing subjects through subjection to knowledge they come to recognize as their own (removed for peer review).

Foucault contrasts this with Stoic spiritual direction, where obedience is temporary and geared toward autonomy through alignment with logos, without requiring inner confession. In Christianity, however, obedience becomes an end in itself, embedded in a permanent asymmetry of power. He locates the origins of this model in the fourth century, particularly in the thought of John Cassian, who formulated the principles of endless obedience, unceasing examination, and exhaustive confession (Foucault 2018b, p. 262). Cassian urged disciples to “disclose [their thoughts] to their elder as soon as they arise […] and not rely on their own discernment” (Institutes, IV.9). Foucault identifies this nexus of truth-production and self-renunciation as the “schema of Christian subjectivity” (Foucault 2018b, p. 280), later systematized in the Borromean model of spiritual direction, where the director becomes a “guardian angel” entrusted with the inner life of the penitent (Foucault 2001, p. 232).

3.1.2. The Relation Between the Archaeology of Knowledge and the Genealogy of Ethics

This historical configuration of subjectivity, grounded in the interplay between confession, obedience, and surveillance, prepares the ground for Foucault’s subsequent inquiry into the ethical dimension of subject formation—namely, the relation between the archaeology of knowledge and the genealogy of ethics.

Building upon the relation between knowledge, power, and subjectivation explored in the genealogical analysis of pastoral power, Foucault turns toward the ethical dimension of subject formation through the concept of spirituality.

Far from being limited to a religious or mystical dimension, spirituality in its Foucauldian sense refers to concrete practices of self-transformation that enable the subject to access truth and resist historical forms of subjection. This perspective inaugurates a mode of analysis in which care of the self—drawn from ancient philosophical traditions—is reinterpreted as a field of articulation between knowledge, power, and subjectivation. It is at this intersection that spirituality and genealogy converge: both seek to understand how the ethical constitution of subjects is inscribed within the meshes of power, and how it can simultaneously open breaches of freedom and the creation of new forms of existence.

This new interest is also tied to his diagnosis of the “decline of revolutionary desire in the West” (removed for peer review). This concern led him to reflect on the “religious origins of modern revolutions,” especially after reading The Principle of Hope by Ernst Bloch and analyzing the Iranian Insurrection of 1978. This event struck Foucault because it articulated a political agenda for social transformation with a strong spiritual dimension—without mediation by the traditional forms of Western Marxism.

Foucault identified in this phenomenon what he called political spirituality, understood as a practice of resistance and self-transformation through which the subject breaks with the subjection imposed by power apparatuses and constitutes itself as a subject of knowledge, belief, and action. It is a process of renouncing the condition of the dominated and enacting subjective insurrection: “To become other than what one is, other than oneself” (Foucault 2006, p. 21).

Rather than a form of traditional militancy, political spirituality constitutes an interior practice of freedom through which the subject breaks social and political subjection.

Later, Foucault developed the notion of spirituality as care of the self in his lecture course L’Herméneutique du sujet (1981–1982). Here, he broadens the concept: spirituality is no longer merely a political force of resistance, but a set of individual ethical practices by which the subject transforms itself in order to access truth. For Foucault, spirituality refers to the set of transformative practices that constitute the subject as a necessary condition for the apprehension of truth (Foucault 2005b, p. 19).

This epimeleia heautou is not a nostalgic return to ancient ethics, but a secularized form of spirituality, expressed in contemporary practices of resistance. Drawing on Greco-Roman traditions of self-transformation—such as Stoic and Epicurean exercises—Foucault demonstrates that access to truth requires an inner metamorphosis of the subject. It is through this trajectory that he elaborates a genealogy of ethics, shifting his focus from epistemology to practices of subjectivation. Here, care of the self becomes a practice of freedom, a mode of constituting the self through resistance. As he puts it, the genealogy of ethics involves “an ethical work on the self” (Foucault 2006, p. 49), in which truth emerges not as a given, but as the effect of a new mode of being.

Thus, political spirituality, care of the self, and the genealogy of ethics become interconnected: resistance to subjection, inner transformation, and the constitution of free subjects are three dimensions of the same movement of freedom production. As Foucault notes “all the great political, social and cultural upheavals could only effectively take place in history from a movement that was a movement of spirituality” (Foucault 2018, p. 23). Therefore, the genealogy of ethics reveals the inseparability of self-transformation and world transformation.

Spirituality as care of the self may serve as the basis for a political practice that does not aim merely to reform external structures, but to reshape subjectivity itself in critical relation to historical forms of power.

Given the complex and intrinsic relationship between knowledge and power, when there is an abuse of power, it calls for a genealogy of ethics—as a way of subverting knowledge and inverting power into a force of resistance. This is especially relevant when subjectivity is challenged by what wounds it historically—by the painful nature of historical processes.

To illustrate this complex dynamic, knowledge, like a river, carries evolving ideas and theories. Power, like riverbanks, shapes and channels this flow. Over time, however, knowledge erodes and reshapes power, creating new paths and possibilities. This illustrates how knowledge influences and redefines power, generating new truths that guide and transform action when rooted in a genealogy of ethics. Subjectivity arises both from adherence to norms and from the potential for resistance when faced with abuse, making it a dynamic and historical process. In other words, knowledge continually reshapes the structures that once confined it, producing new regimes of truth that reconfigure power.

This new mode of knowledge can emerge either through a spirituality conceived as a renewed consciousness of care of the self—where ethical transformation enables access to truth—or as a form of political spirituality inscribed in a collective agenda of resistance and social reconfiguration; both trajectories constitute distinct yet convergent expressions of a genealogy of ethics, in which subjectivation becomes the site of epistemic and political innovation.

Figure 5.

The metaphor of the polyhedron applied to genealogy of ethics.

Figure 5.

The metaphor of the polyhedron applied to genealogy of ethics.

It is precisely within this relationship—between spiritual transformation and genealogical critique—that the production of theological knowledge takes place, always conceived as the second act of a first existential or spiritual experience. In dialogue with Foucault’s archaeological project, Michel de Certeau identifies spirituality as a kind of Trojan horse inserted into theological discourse: it destabilizes doctrinal closures from within and exposes their entanglement with structures of abusive power. This becomes especially urgent in the face of history’s wounds—those open traumas that, through institutional negligence or as by-products of power apparatuses, infiltrate the daily lives of individuals and communities.

3.2. The Archaeology of the Religious and the ‘Genealogy’ of Ethics in Michel de Certeau

In Heterologies, Michel de Certeau describes Michel Foucault’s archaeology as driven by a paradoxical experience of absence and fascination with what he calls ‘the black sun of language’ (Certeau 1986, p. 171). This image refers to a blind spot, an opaque source of light that both generates and obscures meaning, a place where language is revealed in its radical otherness but also in its essential opacity.

For Certeau, this ‘black sun’ expresses the condition of Foucault’s archaeological project: a language that excavates the rules of knowledge formation but finds no ultimate foundation, only a field of games, ruptures and silences. It is a knowledge that operates without a founding subject, without a transcendental origin, but which is paradoxically structured around this central absence. Foucault, according to Certeau, becomes the ‘historian of disappearance’ because he explores the negativity at the heart of Western knowledge, exposes the flaws in the fabric of speech, and illuminates an absence - the death of God, the death of man, the eclipse of full meaning - that underlies modernity (Certeau 1986, pp. 171-172).

This notion has direct implications for the unfinished task of an archaeology of the religious, which would allow a theology of difference to overcome its self-referentiality. The Black Sun suggests that all theological language is pervaded by an original emptiness, an irreducible otherness that prevents any systematic or totalising closure. The theology of difference inspired by this vision does not seek to fill the void with new dogmatic syntheses, but to inhabit the gap, to welcome the otherness of God and the other as sources of meaning that escape attempts at totalisation.

By emphasising the black sun as an image of Foucault’s archaeological language, Certeau invites theology to recognise that its own language is always in danger, always on the threshold between word and silence, between revelation and absence. The Mystic Fable that Certeau explores in his later work is an expression of this tension: speech that is aware of its own inadequacy and yet continues to narrate, to invoke, to translate the ineffable (Certeau 1995, p. 109).

Certeau thus shows how modern history does not completely break with the religious model; it transforms the religious experience of otherness and absence (God, the other) into a historiographical practice that deals with the past as an absent other. For Certeau, the historian becomes the one who replaces the theologian: someone who deals with traces and remnants and, on the basis of them, writes a narrative with an ordering and normative function. His proposal for an archaeology of the religious thus has a critical function: it makes visible this return of the repressed, that is, the persistence of an underlying theological structure in the way historical knowledge is narrated and organised.

Certeau emphasises the question of otherness, which, as we know, is virtually absent from Foucault. He is interested in the experience of those who write history, in the relationship between enunciation and absence, and in the symbolic processes inherited from religion, especially how the symbolic processes of recognising otherness affect social practices despite the discursive practices of normative theology. History is a field for excavating the traces of otherness that are absent from historiography, with social practices being a privileged site for this absent presence of otherness that is repressed from the point of view of discursive practice.

Michel de Certeau does not present a systematic concept of ‘genealogy’ along Foucauldian lines, but offers contributions that allow a genealogical reading of his historiographical method (1975, pp. 14; 107-108; 314). In several passages, especially in Chapter IX, Certeau focuses on the historical shifts in ethics, religion and knowledge, showing how discursive and institutional practices emerge, transform or are marginalised over time . However, the French Jesuit points to the establishment of an epistemological incompatibility between theology and the emerging human sciences in the 19th century, since the latter operated with an ethical primacy of speech, while theology remained with a dogmatic primacy, which hindered dialogue and led back to the distancing.

Rather than a formal theory, Certeau offers a genealogy of ethics as a shifting field of meaning in which ethical discourse emerges not from doctrine, but from situated, embodied practices that function as interpretative operators of modern social life. From the 17th century onwards, Christian ethics was confronted with social and political critiques that displaced it from its normative position and replaced it with a dialectic of uses and conflicts of power, especially with regard to the control of religious behaviour. Between the 17th and 18th centuries, a rupture between religion and morality was consolidated, allowing the emergence of an autonomous social ethics responsible for organising collective practices and relativising inherited belief systems. This autonomy culminated in the Enlightenment with the primacy of ethics over faith, strongly influenced by Rousseau, who privileged morality over dogma. In the 18th century, ethics became associated with the ideal of progress and democratisation, taking on the role of guiding the improvement of societies. Religious practices were reinterpreted in terms of a new social order in which ethics determined behaviour and replaced the old religious frameworks. In this context, Christian ethics was absorbed and reorganised by the logic of the ‘duty of the state’, which linked moral meaning to the social position held and the functions performed. This reorganisation also led to a split between piety and morality: morality became a public language, while piety was relegated to the private sphere. Popular culture, in turn, is reinterpreted as an instrument of public utility, incorporating religious and social practices into the ethical language of modernity. In The Writing of History, Certeau presents a certain ‘genealogy’ of ethics in which it becomes a linguistic-pragmatic device in which ethical speeches organise social meanings, legitimacies and ways of life. It is a practical, situated and historical ethics that functions as a key to understanding human behaviour within the concrete conditions of modern society. In place of obedience to dogma, an ethics emerges as a language of practice, articulated with the apparatuses of the state, with discourses of progress, and with mechanisms of control and self-formation. This ethics replaces dogma as the epistemic axis of the human sciences and functions as a criterion of intelligibility for modern experience (Certeau 1975, p. 19; 152f).

The place of theology seems to have been left empty by the human sciences. Theology is seen as an institution for the enunciation of meaning that remains tied to a dogmatic order, a semantics that is identified either with ideology or with private convictions that are incompatible with scientific analysis. The so-called human sciences, on the other hand, are developing into forms of knowledge whose project and method, based on statutes, social tasks and conflicts, reorganise the meaning of existence. The primacy of ethics for Certeau is not a kind of principle of moral superiority, but rather an operative capacity to produce meaning from everyday life. This primacy relegates theology to a marginal or reactive position, requiring it to reconcile itself with the devices of meaning production inherent in modernity.

Certeau observes that in the context of growing secularisation and religious marginalisation in rural France in the 19th century, many Catholic religious congregations reorganised themselves as forms of social presence aimed at dignifying human life. These congregations, composed of consecrated women and men, developed social and educational activities in line with principles that would later be recognised as human rights, such as access to basic education, health, decent work and child protection. In response to the decline of traditional religious structures and the spread of urban industrialisation, they directed their missions to the interior of the country, where the peasant population found itself excluded from the benefits of technological progress and public education. Certeau describes this reorganisation as a ‘topography of urgencies’ in which evangelisation involved the creation of schools, hospitals, charitable works and mutual support structures in order to associate evangelisation with ‘the fight against the ignorance of the masses, aid to accident victims or abandoned children, the hospitalisation of the sick, the education of girls, scholarships, etc.’ (1975, p. 170).

In 19th-century France, religious congregations developed social practices—education, health, care—which embodied a public ethic anticipating modern human rights discourse (removed for peer review). Although based on theological categories such as salvation, charity and grace, these practices converge with human dignity, promoting inclusion, justice and care for the most vulnerable. It is therefore an incarnate spirituality that responds to modern exclusion through an ethic of presence, anticipating social concerns that would later be addressed in the field of human rights and in the Church’s social doctrine with Rerum Novarum (1891). This phenomenon, described as a response to the urgencies of modernity, constitutes an essential genealogical field of European social Catholicism, providing the historical and theological-practical background for the emergence of liberation theologies in Latin America, for example, and the origins of how the religious agenda of Catholicism intersects with the political agenda of human rights after the industrial revolution, in new forms of critical spirituality and social commitment, bridging to the 20th century and the primacy of ethics as a field for reconfiguring regimes of meaning for a public discursive practice of theology.

Michel de Certeau uses the metaphor of the Trojan Horse to describe the way in which Christian spirituality - and in particular mysticism and social practices of faith - operates within the rigid and dogmatic structures of institutionalised theology. For him, spirituality does not conform to normative orthodoxy, but infiltrates established systems as a foreign body, bringing with it the memory of otherness, absence and promise. In La Fable Mystique, Certeau observes that Christian mysticism - as a practice that occurs in ‘deviation’ and ‘excess’ (Certeau 1995, pp. 29-30) - has often imploded the mechanisms of power and control of dogmatic theology. The spirituality lived out in the social practices of Catholicism - whether through care for the sick, popular education or involvement in social movements - acted as an internal resistance, challenging the mechanisms of doctrinal closure that sometimes legitimised or covered up social injustices. It is, as Certeau says in La Faiblesse de Croire, a ‘weak faith’ that acts as a Trojan horse: it does not seek to conquer or impose, but to destabilise certainties and open spaces for difference, listening and hospitality to the other (Certeau 1987, pp. 25-28).

Certeau understands ‘weak faith’ as a practical, everyday form of theological resistance that reconfigures social space without being bound by rigid forms of control. This weakness is not a sign of impotence, but of openness to otherness and to listening to others. In L’Invention du quotidien (1980), Certeau identifies the place where this faith manifests itself: in simple gestures and anonymous practices that quietly and subversively reconfigure social space. The everyday is the terrain of micro-resistance, where weak faith reinvents itself outside the great institutional narratives. In this perspective, Certeau’s Trojan horse is the ordinary practice of faith itself, which infiltrates institutions and doctrines as a discreet force of transformation: a mysticism that does not cry out but transforms, a spirituality that operates in the ‘low continuous’ of everyday life (Certeau 1987, pp. 25-28). By shifting attention from grand theological constructions to the dispersed and anonymous practices of everyday subjects, Certeau proposes a theology of difference capable of recognising the dignity of the practices of subaltern subjects as producers of new subversive meanings that reconfigure the social order through the creative reinvention of everyday life as a tactic of resistance. The question of genealogy applied to the emergence of ethics can be understood in his perspective as a critical analysis of the processes by which certain regimes of meaning are constituted and stabilised in history, especially since the 17th century. It is linked to his notions of ‘production of place’ and ‘repressed otherness’, since he focuses not only on legitimised speech, but also on absences, silences and practices that escape official narratives - such as popular, mystical or marginalised practices.

In particular, Certeau traces the replacement of theology by ethical speech in the human sciences as a symptom of this epistemic transformation. The archaeo-genealogical question, in this sense, is linked to the task of bringing out the historicity of such displacements - not as linearity, but as ruptures and reconfigurations. Thus, genealogy in Certeau is the movement of critical historicisation of regimes of knowledge, with attention to the excluded and the mechanisms of exclusion that affect both language and social practices.

Michel Foucault’s archaeo-genealogy of knowledge-power and its implications for the task identified by Michel de Certeau as the archaeology of the religious share a common objective: to investigate the historical conditions that make certain statements possible, though each emphasizes different dimensions of that emergence. In proposing his archaeology, Foucault seeks to describe the impersonal rules that structure the formation of knowledge in different epochs, revealing the systems of enunciability that define the field of what can be thought. Certeau appropriates and displaces Foucault’s archaeological method, applying it to reveal the underlying theological logic in historiographical forms. While Foucault traces discursive conditions, Certeau maps the interruptions introduced by social practices that do not conform to established discursive regimes—what the figure identifies as non-discursive practices with subversive effects. He showed how Western historiography, in seeking to ground itself in scientific rationality, nevertheless inherits from religious scriptures a logic of enunciation oriented toward absence and the symbolic management of alterity. Both archaeologies, therefore, offer critical and methodological tools for constructing an archaeology of theological knowledge: one capable of identifying the historical, discursive, and institutional conditions under which theological knowledge arises, while also uncovering its continuities, ruptures, and specific regimes of truth. In this sense, the analysis of theological knowledge must attend equally to its non-discursive dimension: to the social practices that reinvent everyday life from within a theological horizon and that, as illustrated in

Figure 6, act as Trojan horses disrupting the mechanisms of control that seek to contain theological discourse.

Moreover, insofar as Foucault’s archaeology is linked to his genealogical method, it proves extremely useful in identifying how religion can be understood as a complex phenomenon in which, within its theological discursive context, genealogies of power and genealogies of ethics coexist—often sustained by a silent theology revealed in the social practices it supports. As Metz pointed out, in twentieth-century contextual theologies, there is a form of revelation that occurs precisely in concrete action directed toward the transformation of reality(1999, pp. 246–55). These practices act as Trojan horses that undermine abusive forms of power rooted in religious discourse. This dual movement of archaeology and genealogy—as visualized in

Figure 6—constitutes a critical toolbox for identifying modes of theological self-referentiality and recovering the public relevance of subaltern practices that challenge and transform the structures of discourse from within.