Submitted:

08 May 2025

Posted:

08 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Apparatus

2.3. Cyclic Voltammetry

2.4. Double Potential Step Chronoamperometry

2.5. Fabrication of Electrodes

2.5.1. Composite Thermoplastic Filament Fabrication

2.5.2. Computer-Aided Design and 3D Printing

2.6. Analytical Application

3. Results and Discussion

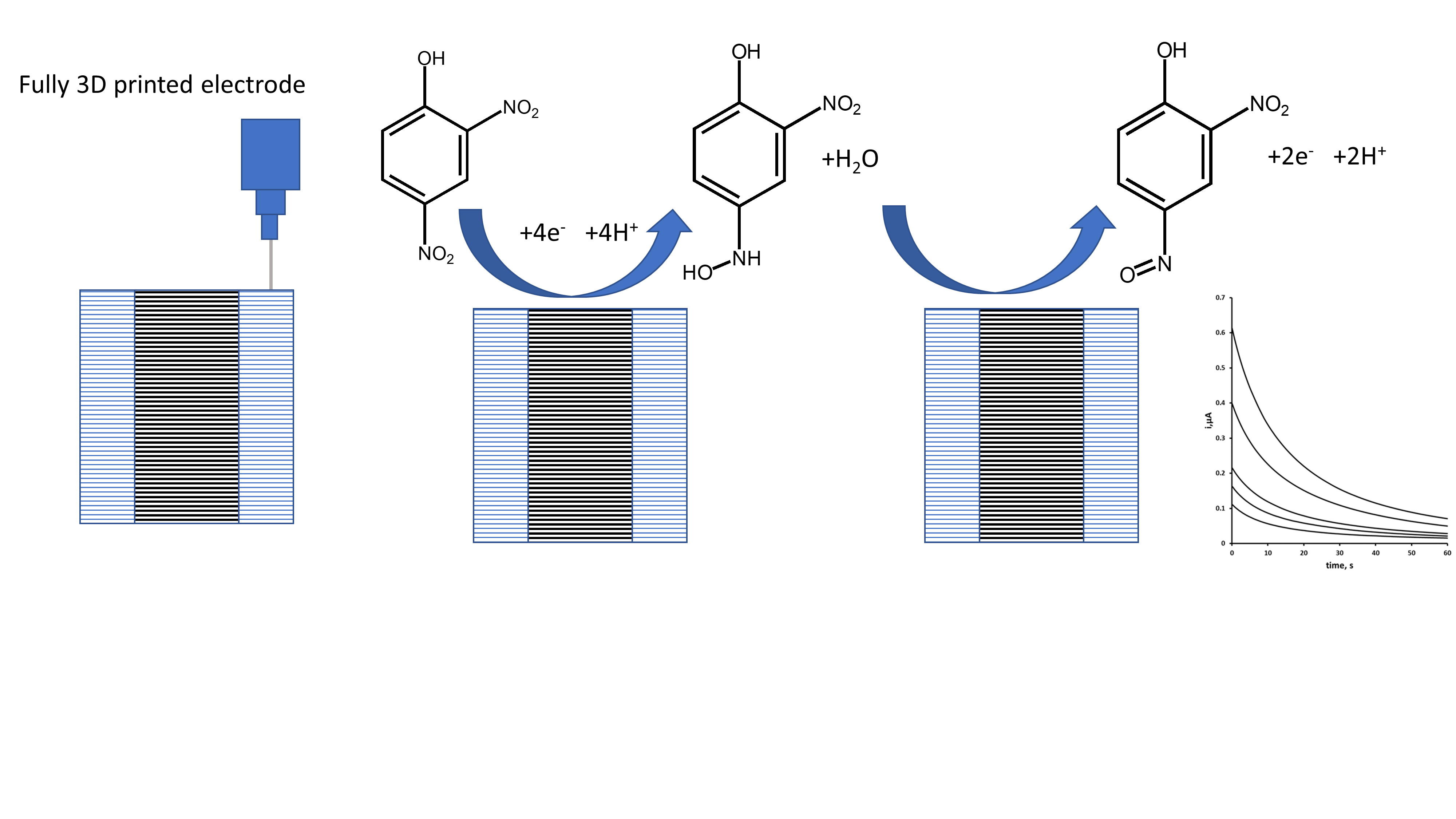

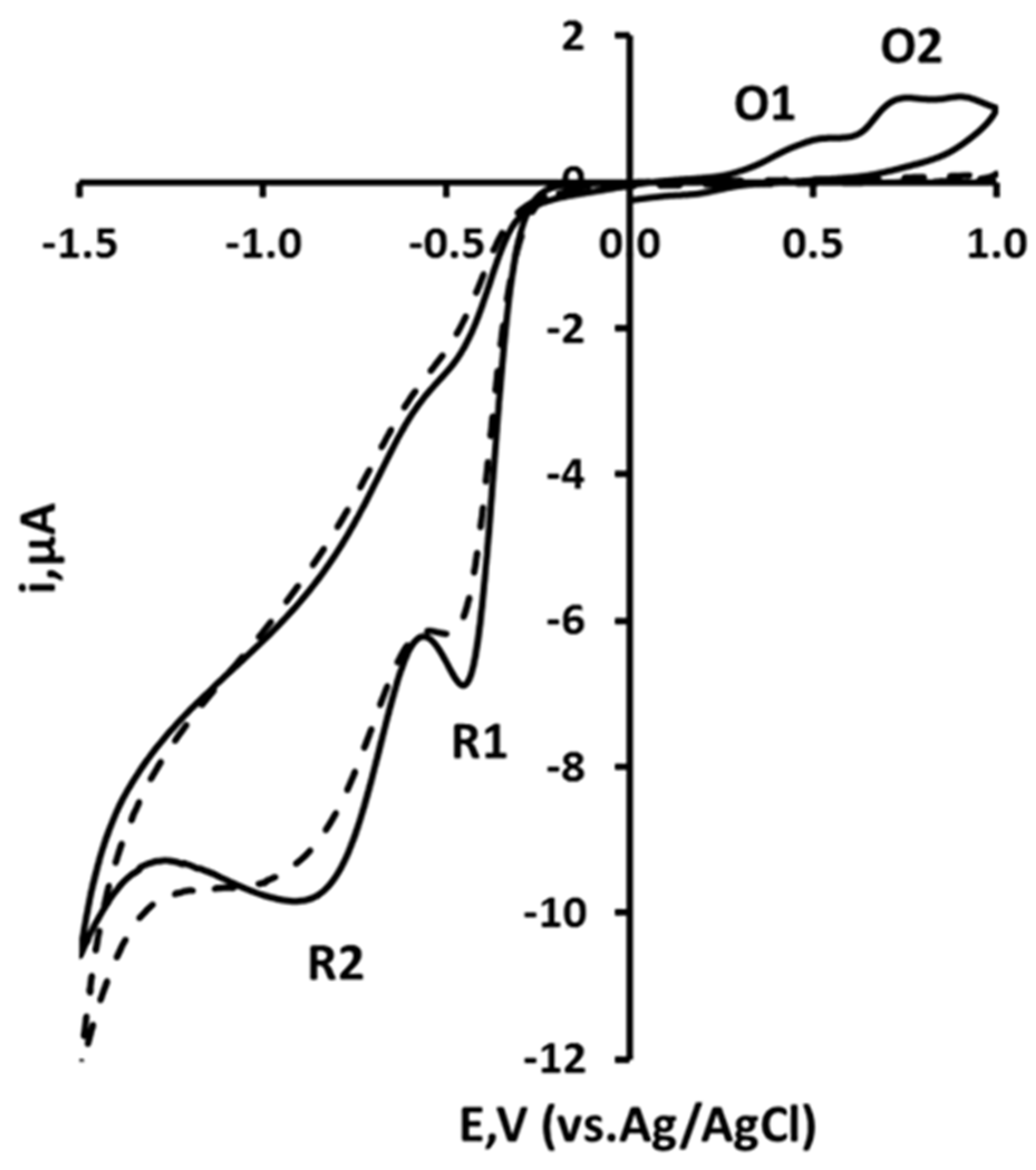

3.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

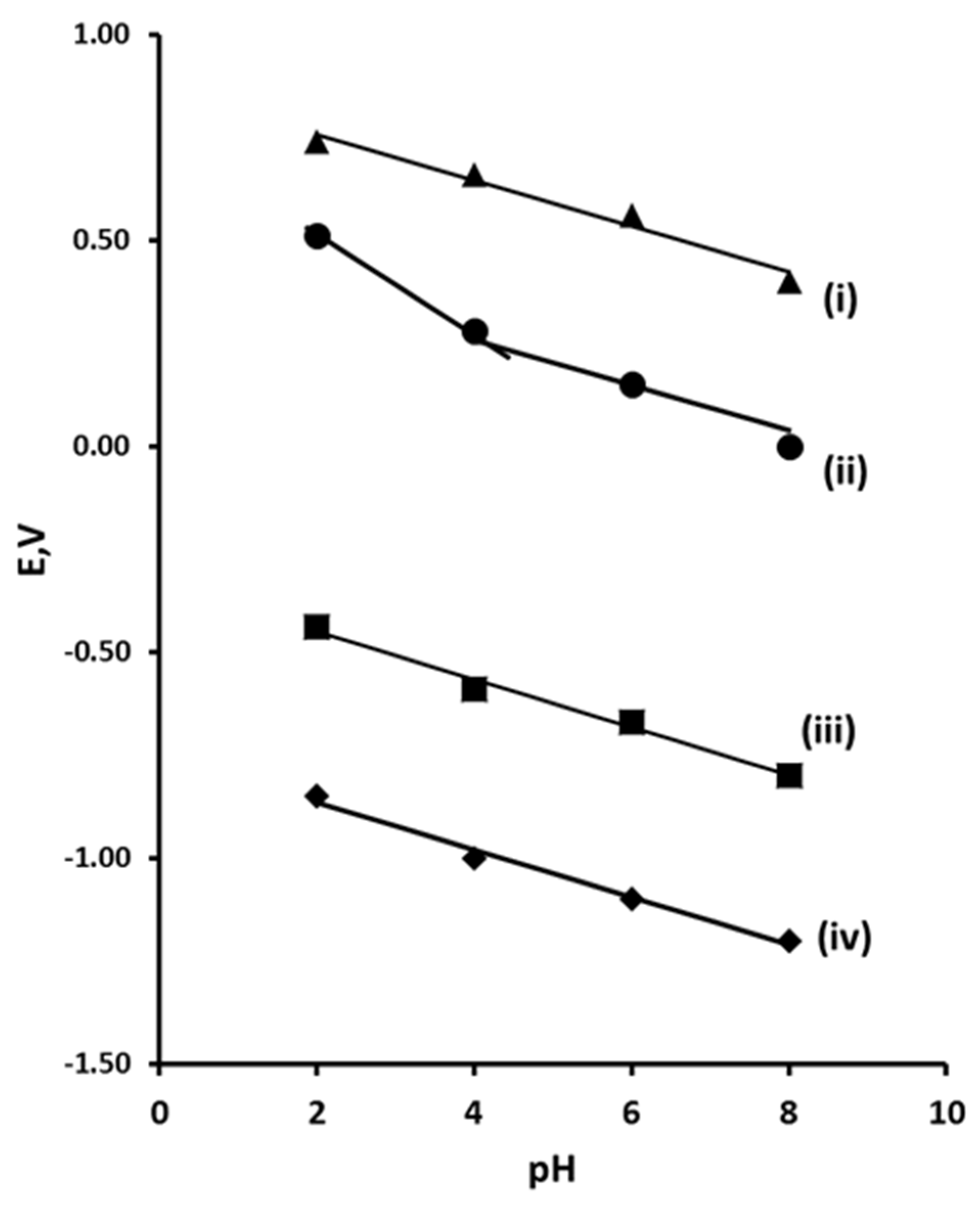

3.2. Effect of pH on Peak Potential

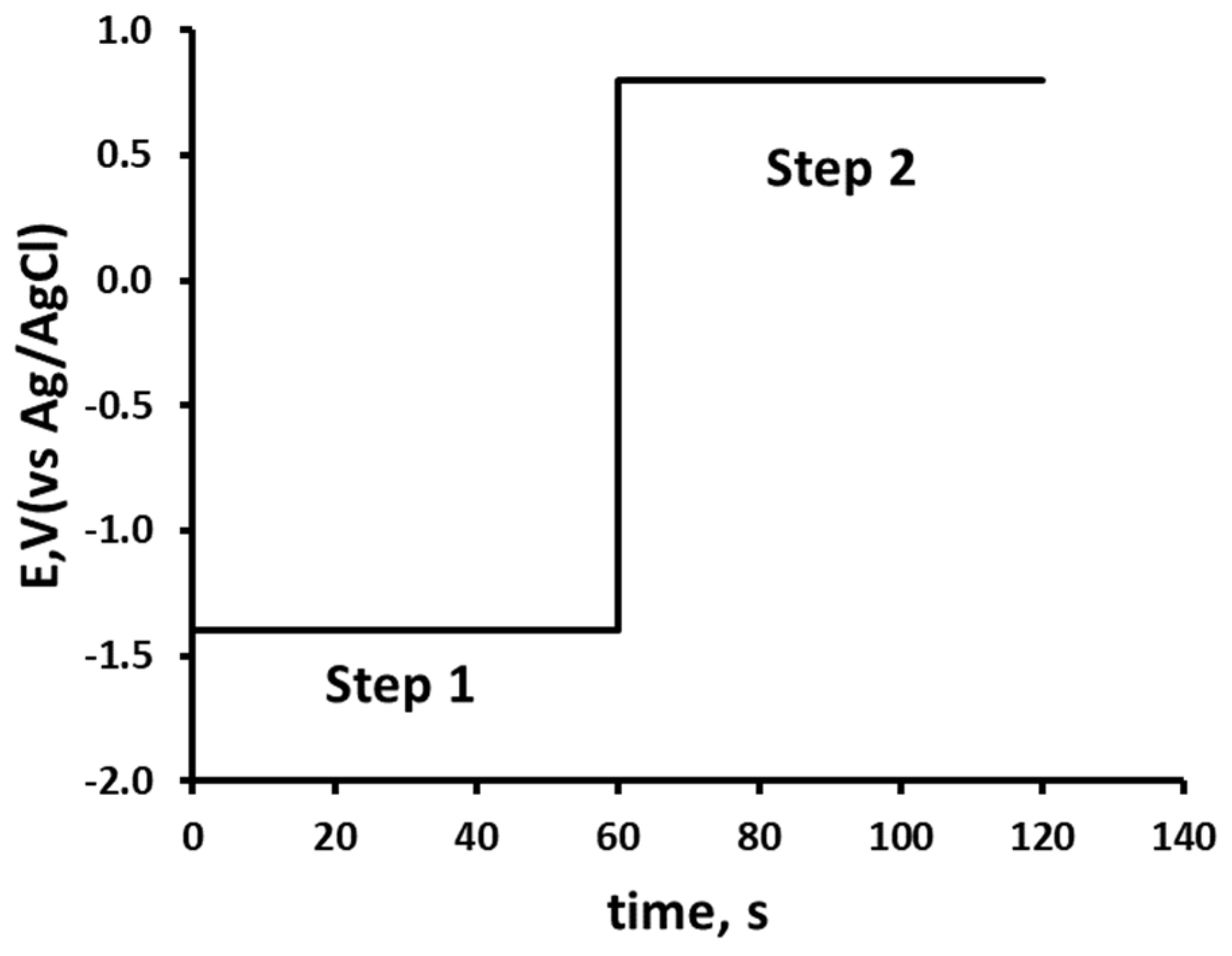

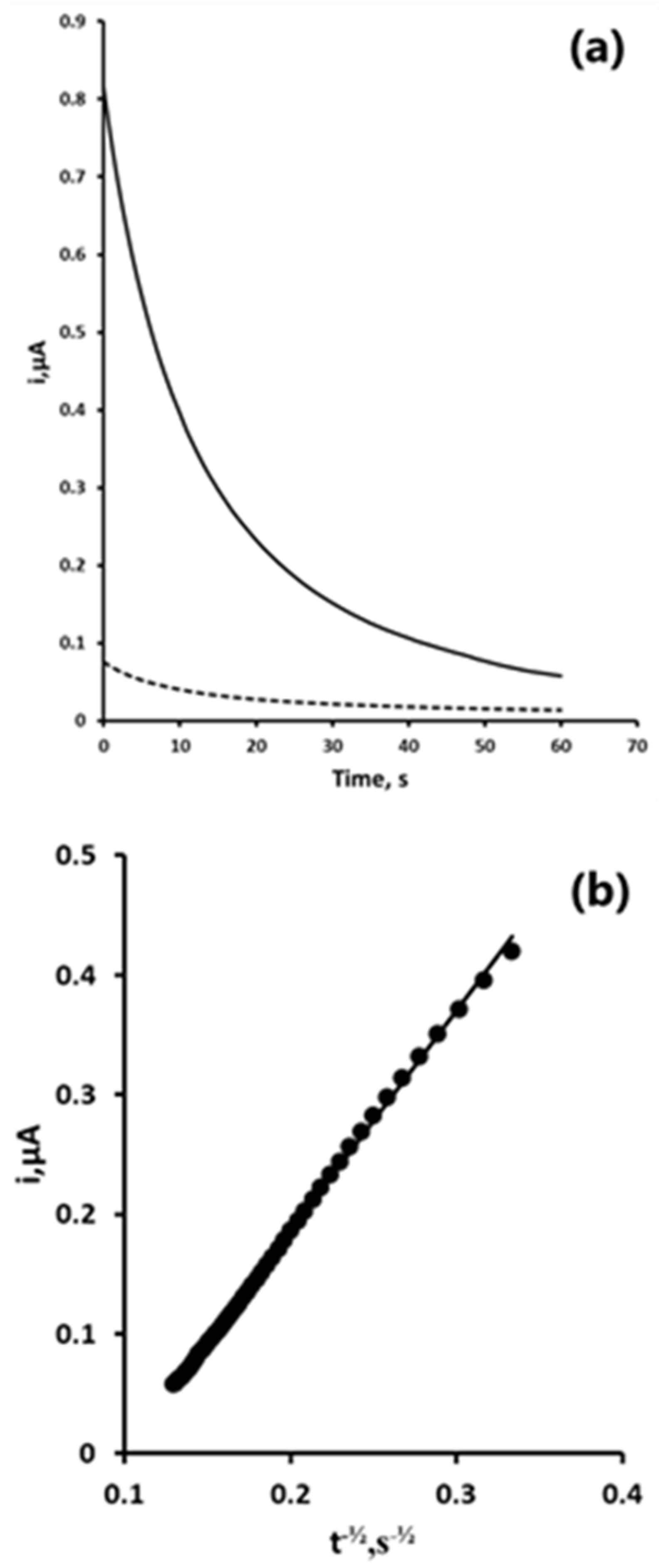

3.3. Double Potential Step Chronoamperometry

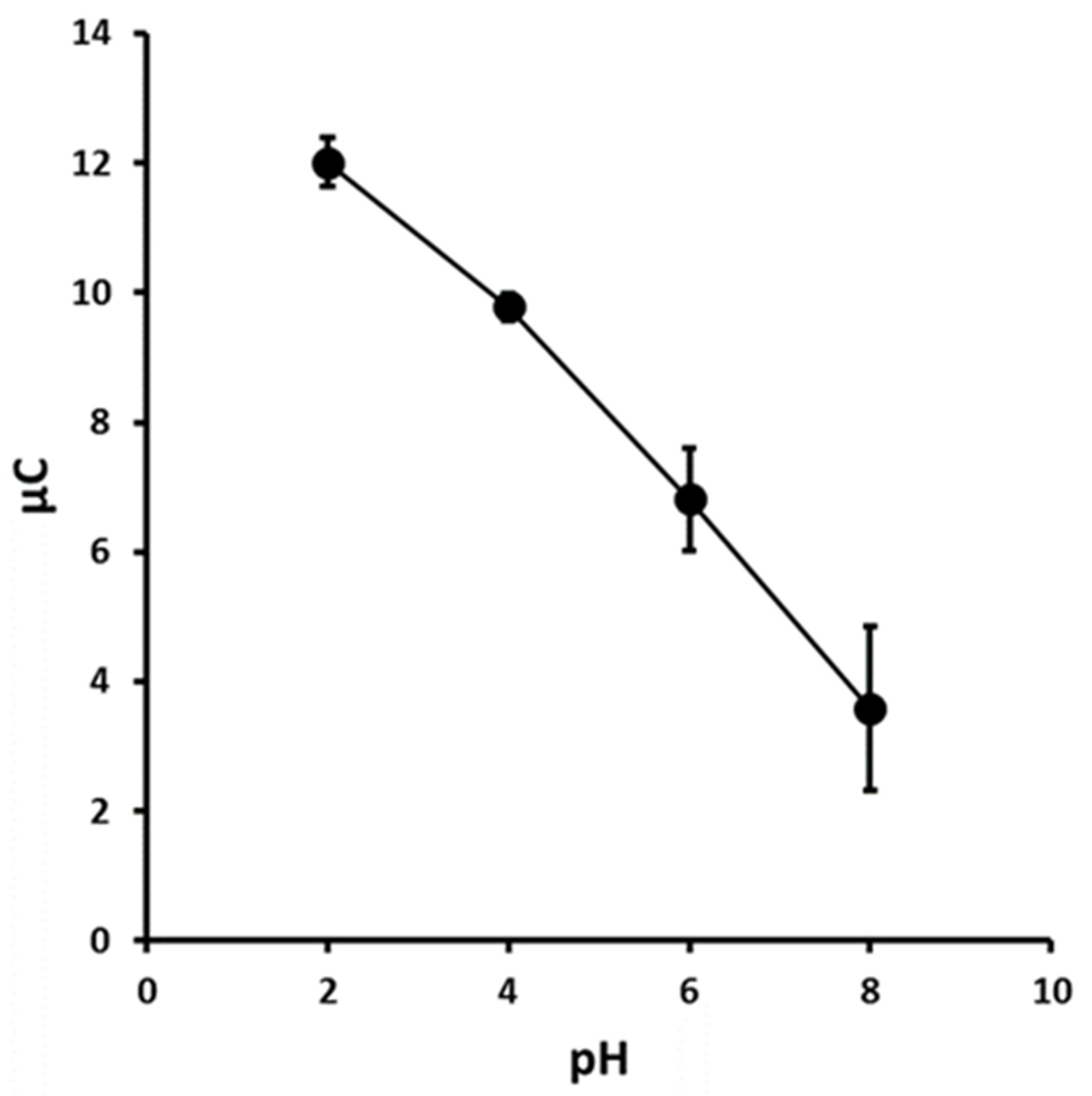

3.4. The Effect of pH on the Chronoamperometric Response

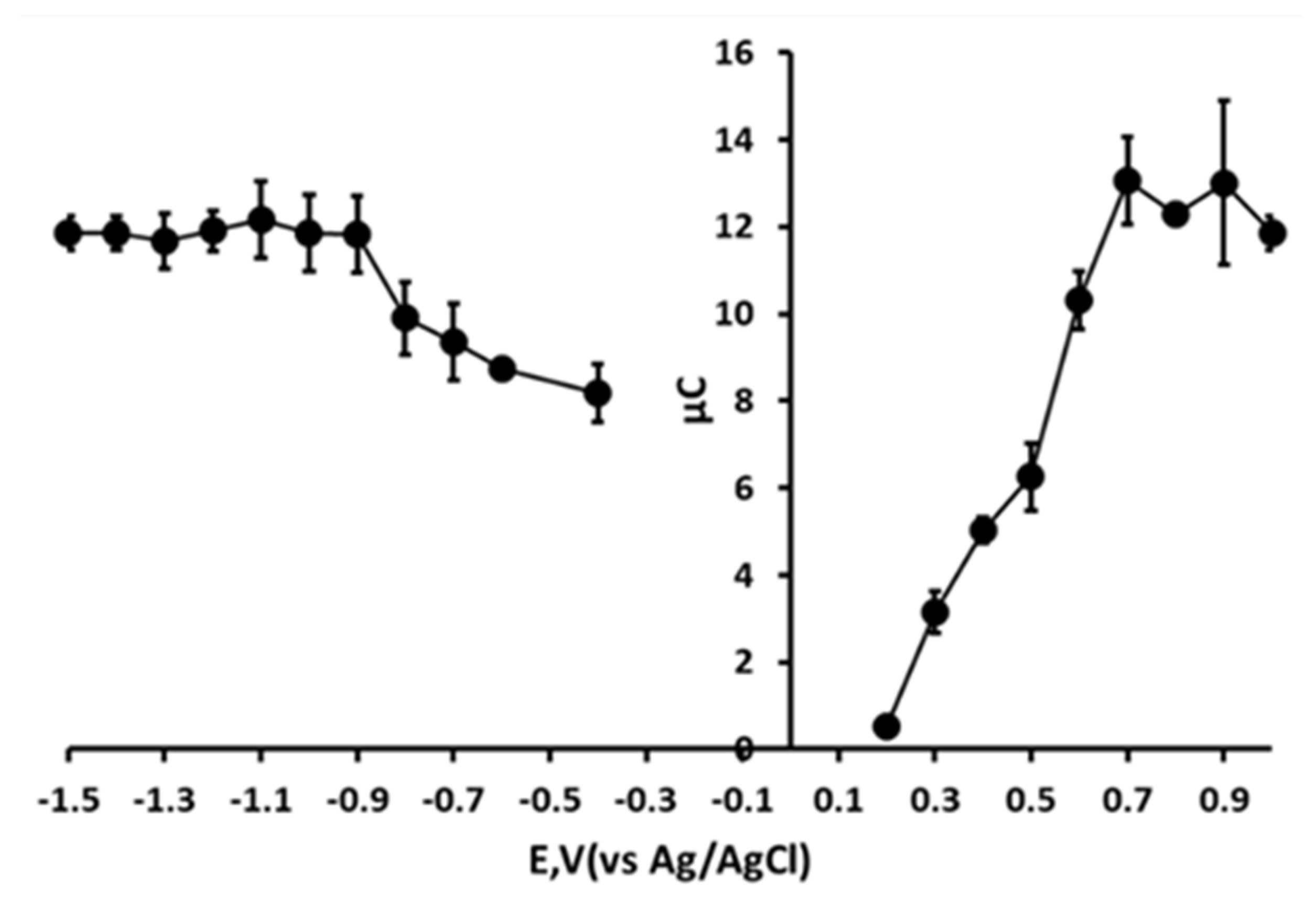

3.5. Optimisation of Chronoamperometric Step Potentials

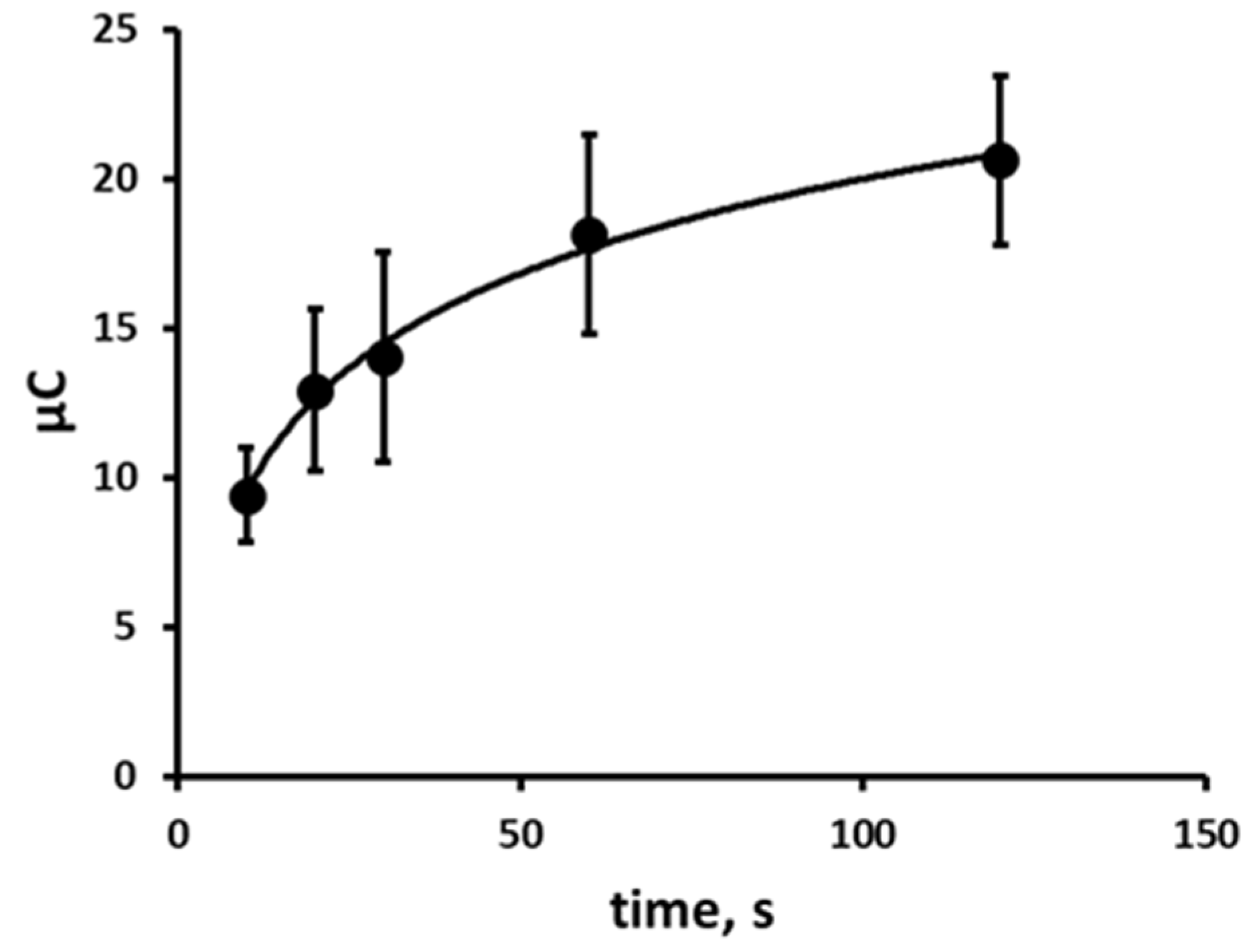

3.6. The Effect of Time on the Chronoamperometric Response

3.7. Calibration Curve and Limit of Detection

3.8. Analytical Application

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ag/AgCl | Silver/Silver Chloride |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CV | Cyclic Voltammetry |

| 2,4-DNP | 2,4-Dinitrophenol |

| LC50 | Median Lethal Concentration |

References

- Dadban Shahamat, Y.; Sadeghi, M.; Shahryari, A.; Okhovat, N.; Bahrami Asl, F.; Baneshi, M.M. Heterogeneous catalytic ozonation of 2, 4-dinitrophenol in aqueous solution by magnetic carbonaceous nanocomposite: catalytic activity and mechanism, Desalination and Water Treatment 2016, 57, 20447-20456.

- Nojima, K.; Kawaguchi, A.; Ohya, T.; Kanno, S.; Hirobe, M. Studies on photochemical reaction of air pollutants. X. Identification of nitrophenols in suspended particulates. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 1983, 31, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan, M.A.; Slimak, M.W.; Gabel, N.W.; May, I.P.; Fowler, C.F.; Freed, J.R.; Jennings, P.; Durfee, R.L.; Whitmore, F.C.; Maestri, B.; Mabey, W.R.; Holt, B.R.; Gould, C. Water-Related Environmental Fate of 129 Priority Pollutants; Office of Water Planning and Standards, Office of Water and Waste Management, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, D.C., 1979.

- Dehghani, M.H.; Alghasi, A.; Porkar, G. Using medium pressure ultraviolet reactor for removing azo dyes in textile wastewater treatment plant, World Applied Sciences Journal 2011, 12, 797-802.

- Paisio, C.E.; Agostini, E.; González, P.S.; Bertuzzi, M.L. Lethal and teratogenic effects of phenol on Bufo arenarum embryos, Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 167, 64-68.

- Marit, J.S.; Weber, L.P. Acute exposure to 2, 4-dinitrophenol alters zebrafish swimming performance and whole body triglyceride levels, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2011, 154, 14-18.

- Kuzmina, V.V.; Tarleva, A.F.; Gracheva, E.L. Influence of various concentrations of phenol and its derivatives on the activity of fish intestinal peptidases, Inland Water Biology 2017, 10, 228-234.

- Shea, P.J.; Weber, J.B.; Overcash, M.R. Residue Reviews: Residues of Pesticides and Other Contaminants in the Total Environment; Gunther, F.A., Gunther, J.D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 87, pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Shaddad, M.A.; Radi, A.F.; El-Enany, A.E. Seed Germination, Transpiration Rate, and Growth Criteria as Affected by Various Concentrations of CdCl2, NaF, and 2,4-DNP. Journal of Islamic Academy of Sciences 1989, 2, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, H.L. The Effect of Arsenate and Other Inhibitors on Early Events during the Germination of Lettuce Seeds (Lactuca sativa L.). Plant Physiology 1973, 52, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.S.C.; Yang, T.-K.; Chuang, T.-T. Soil phenolic acids as plant growth inhibitors, Soil Science 1967, 103, 239-246.

- Nanda, K.K.; Dhawan, A.K. A paradoxical effect of 2,4-dinitrophenol in stimulating the rooting of hypocotyl cuttings ofPhaseolus mungo, Experientia 1976, 32, 1167-1168.

- Perkins, R.G. A study of the munitions intoxications in France, Public Health Reports 1919, 34, 2335-2374.

- Harris, M.O.; Corcoran, J. Toxicological Profile for Dinitrophenols; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, United States Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Hargreaves, I.P.; Al Shahrani, M.; Wainwright, L.; Heales, S.J.R. Drug-induced mitochondrial toxicity, Drug Safety 2016, 39, 661-674.

- Boardman, W.W. Rapidly developing cataracts after dinitrophenol, California and Western Medicine 1935, 43, 118.

- Petróczi, A.; Ocampo, J.A.V.; Shah, I.; Jenkinson, C.; New, R.; James, R.A.; Taylor, G.; Naughton, D.P. Russian roulette with unlicensed fat-burner drug 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP): evidence from a multidisciplinary study of the internet, bodybuilding supplements and DNP users, Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 2015, 10, 1-21.

- Fernardes, V.F.; Izidoro, L.F.M. The Risks of Using 2,4-Dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP) as a Weight Loss Agent: A Literature Review, Annals of Clinical and Medical Case Reports 2022, 9, 1-7.

- Freeman, N.; Moir, D.; Lowis, E.; Tam, E. 2, 4-Dinitrophenol:‘diet’drug death following major trauma, Anaesthesia Reports 2021, 9, 106-109.

- Abdelati, A.; Burns, M.M.; Chary, M. Sublethal toxicities of 2, 4-dinitrophenol as inferred from online self-reports, PLoS One 2023, 18, e0290630.

- Rudenko, I.B.; Shaimardanova, D.R.; Kayumova, R.R. Clinical case report of acute dinitrophenol poisoning with a fatal outcome of Udmurt Republic, Sudebno-meditsinskaia Ekspertiza 2023, 66, 59-61.

- Tuğcan, M.O.; Kekeç, Z. A Case of Fatal Poisoning: Use of 2-4 Dinitrophenol for Weight Loss, Anatolian Journal of Emergency Medicine 2024, 7, 87-90.

- Mwesigwa, J.; Collins, D.J.; Volkov, A.G. Electrochemical signaling in green plants: effects of 2, 4-dinitrophenol on variation and action potentials in soybean, Bioelectrochemistry 2000, 51, 201-205.

- Geisler, J.G.; Marosi, K.; Halpern, J.; Mattson, M.P. DNP, mitochondrial uncoupling, and neuroprotection: A little dab’ll do ya, Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2017, 13, 582-591.

- Lee, Y.; Heo, G.; Lee, K.M.; Kim, A.H.; Chung, K.W.; Im, E.; Chung, H.Y.; Lee, J. Neuroprotective effects of 2, 4-dinitrophenol in an acute model of Parkinson’s disease, Brain Research 2017, 1663, 184-193.

- Wu, B.; Jiang, M.; Peng, Q.; Li, G.; Hou, Z.; Milne, G.L.; Mori, S.; Alonso, R.; Geisler, J.G.; Duan, W. 2, 4 DNP improves motor function, preserves medium spiny neuronal identity, and reduces oxidative stress in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease, Experimental Neurology 2017, 293, 83-90.

- Perry, R.J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, X.-M.; Boyer, J.L.; Shulman, G.I. Controlled-release mitochondrial protonophore reverses diabetes and steatohepatitis in rats, Science 2015, 347, 1253-1256.

- Honeychurch, K.C.; Brooks, J.; Hart, J.P. Development of a voltammetric assay, using screen-printed electrodes, for clonazepam and its application to beverage and serum samples, Talanta 2016, 147, 510-515.

- Honeychurch, K.C.; Davidson, G.M.; Brown, E.; Hart, J.P. Novel reductive–reductive mode electrochemical detection of Rohypnol following liquid chromatography and its determination in coffee, Analytica Chimica Acta 2015, 853, 222-227.

- Honeychurch, K.C.; Smith, G.C.; Hart, J.P. Voltammetric behavior of nitrazepam and its determination in serum using liquid chromatography with redox mode dual-electrode detection, Analytical Chemistry 2006, 78, 416-423.

- Honeychurch, K.C. Development of an electrochemical assay for the illegal “fat burner” 2, 4-dinitrophenol and its potential application in forensic and biomedical analysis, Advances in Analytical Chemistry 2016, 6, 41-48.

- Xu, F.; Guan, W.; Yao, G.; Guan, Y. Fast temperature programming on a stainless-steel narrow-bore capillary column by direct resistive heating for fast gas chromatography, Journal of Chromatography A 2008, 1186, 183-188.

- Preiss, A.; Bauer, A.; Berstermann, H.-M.; Gerling, S.; Haas, R.; Joos, A.; Lehmann, A.; Schmalz, L.; Steinbach, K. Advanced high-performance liquid chromatography method for highly polar nitroaromatic compounds in ground water samples from ammunition waste sites, Journal of Chromatography A 2009, 1216, 4968-4975.

- Xu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Ren, L.; Long, T. Determination of 2, 4-Dichlorophenol, 2, 4-Dinitrophenol, and Bisphenol a in River Water by Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction (MSPE) Using β-Cyclodextrin Modified Magnetic Ferrite Microspheres and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography – Diode Array Detection (HPLC-DAD), Analytical Letters 2022, 55, 367-377.

- Hofmann, D.; Hartmann, F.; Herrmann, H. Analysis of nitrophenols in cloud water with a miniaturized light-phase rotary perforator and HPLC-MS, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2008, 391, 161-169.

- Gross, B.; Lockwood, S.Y.; Spence, D.M. Recent advances in analytical chemistry by 3D printing, Analytical Chemistry 2017, 89, 57-70.

- . Pan, L.; Shijing, Z.; Yang, J.; Fei, T.; Mao, S.; Fu, L.; Lin, C.T. 3D-Printed Electrodes for Electrochemical Detection of Environmental Analytes. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 2235–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- . Selemani, M.A.; Cenhrang, K.; Azibere, S.; Singhateh, M.; Martin, R.S. 3D Printed Microfluidic Devices with Electrodes for Electrochemical Analysis. Anal. Methods 2025, 17, 2235–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- . Crapnell, R.D.; Banks, C.E. Electroanalysis Overview: Additive Manufactured Biosensors Using Fused Filament Fabrication. Anal. Methods 2024, 16, 2625–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, C.-K.; Peng, P.-J.; Sun, Y.-C. Fully 3D-printed preconcentrator for selective extraction of trace elements in seawater, Analytical Chemistry 2015, 87, 6945-6950.

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap–the replicating rapid prototype, Robotica 2011, 29, 177-191.

- Kitson, P.J.; Glatzel, S.; Chen, W.; Lin, C.-G.; Song, Y.-F.; Cronin, L. 3D printing of versatile reactionware for chemical synthesis, Nature Protocols 2016, 11, 920-936.

- Ambrosi, A.; Pumera, M. 3D-printing technologies for electrochemical applications, Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 2740-2755.

- Djafari, Y.; Abolfathi, N. An inexpensive 3D printed amperometric oxygen sensor for transcutaneous oxygen monitoring, 2016 23rd Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering and 2016 1st International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME) 2016, 281-284.

- Honeychurch, K.C.; Rymansaib, Z.; Iravani, P. Anodic stripping voltammetric determination of zinc at a 3-D printed carbon nanofiber–graphite–polystyrene electrode using a carbon pseudo-reference electrode, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 267, 476-482.

- Loo, A.H.; Chua, C.K.; Pumera, M. DNA biosensing with 3D printing technology, Analyst 2017, 142, 279-283.

- Pohanka, M. Three-dimensional printing in analytical chemistry: principles and applications, Analytical Letters 2016, 49, 2865-2882.

- Ragones, H.; Schreiber, D.; Inberg, A.; Berkh, O.; Kósa, G.; Freeman, A.; Shacham-Diamand, Y. Disposable electrochemical sensor prepared using 3D printing for cell and tissue diagnostics, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2015, 216, 434-442.

- Rymansaib, Z.; Iravani, P.; Emslie, E.; Medvidović-Kosanović, M.; Sak-Bosnar, M.; Verdejo, R.; Marken, F. All-polystyrene 3D-printed electrochemical device with embedded carbon nanofiber-graphite-polystyrene composite conductor, Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 1517-1523.

- Salvo, P.; Raedt, R.; Carrette, E.; Schaubroeck, D.; Vanfleteren, J.; Cardon, L. A 3D printed dry electrode for ECG/EEG recording, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2012, 174, 96-102.

- Silva, M.V.C.O.; Carvalho, M.S.; Silva, L.R.G.; Rocha, R.G.; Cambraia, L.V.; Janegitz, B.C.; Nossol, E.; Muñoz, R.A.A.; Richter, E.M.; Stefano, J.S. Tailoring 3D-Printed Sensor Properties with Reduced-Graphene Oxide: Improved Conductive Filaments. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brum, R.R.D.; de Faria, L.V.; Caldas, N.M.; Pereira, R.P.; Peixoto, D.A.; Silva, S.C.; Nossol, E.; Semaan, F.S.; Pacheco, W.F.; Rocha, D.P.; Dornellas, R.M. 3D-Printed Electrochemical Sensor Based on Graphite-Alumina Composites: A Sensitive and Reusable Platform for Self-Sampling and Detection of 2,4,6-Trinitrotoluene Residues in Environmental and Forensic Applications. Talanta Open 2025, 11, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Fan, F.; Li, S.; Song, Z.; Yang, W.; Duan, H.; Cui, S.; He, X. An Intelligent Portable Point-of-Care Testing (POCT) Device for On-Site Quantitative Detection of TNT Explosive in Environmental Samples. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2025, 439, 137846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, P.J.; Simkins, R.J.J. Acid strengths of some substituted picric acids, Canadian Journal of Chemistry 1968, 46, 241-248.

- Yin, H.; Zhou, Y.; Han, R.; Qiu, Y.; Ai, S.; Zhu, L. Electrochemical oxidation behavior of 2, 4-dinitrophenol at hydroxylapatite film-modified glassy carbon electrode and its determination in water samples, Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2012, 16, 75-82.

- Pletcher, D.; Greff, R.; Peat, R.; Peter, L.M.; Robinson, J. Instrumental Methods in Electrochemistry; Elsevier, 2001.

- Fischer, J.; Vanourkova, L.; Danhel, A.; Vyskocil, V.; Cizek, K.; Barek, J.; Peckova, K.; Yosypchuk, B.; Navratil, T. Voltammetric determination of nitrophenols at a silver solid amalgam electrode, International Journal of Electrochemical Science 2007, 2, 226-234.

- Danhel, A.; Shiu, K.K.; Yosypchuk, B.; Barek, J.; Peckova, K.; Vyskocil, V. The use of silver solid amalgam working electrode for determination of nitrophenols by HPLC with electrochemical detection, Electroanalysis 2009, 21, 303-308.

- Khachatryan, K.S.; Smirnova, S.V.; Torocheshnikova, I.I.; Shvedene, N.V.; Formanovsky, A.A.; Pletnev, I.V. Solvent extraction and extraction–voltammetric determination of phenols using room temperature ionic liquid, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2005, 381, 464-470.

- Wang, X.-G.; Wu, Q.-S.; Liu, W.-Z.; Ding, Y.-P. Simultaneous determination of dinitrophenol isomers with electrochemical method enhanced by surfactant and their mechanisms research, Electrochimica Acta 2006, 52, 589-594.

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, H. Electrochemical sensoring of 2, 4-dinitrophenol by using composites of graphene oxide with surface molecular imprinted polymer, Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2012, 171, 1151-1158.

- Yang, P.; Cai, H.; Liu, S.; Wan, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, N. Electrochemical reduction of 2, 4-dinitrophenol on nanocomposite electrodes modified with mesoporous silica and poly (vitamin B1) films, Electrochimica Acta 2011, 56, 7097-7103.

- Lezi, N.; Economou, A.; Barek, J.; Prodromidis, M. Screen-Printed Disposable Sensors Modified with Bismuth Precursors for Rapid Voltammetric Determination of 3 Ecotoxic Nitrophenols, Electroanalysis 2014, 26, 766-775.

- Karaová, J.; Barek, J.; Schwarzová-Pecková, K. Oxidative and Reductive Detection Modes for Determination of Nitrophenols by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Amperometric Detection at a Boron Doped Diamond Electrode, Analytical Letters 2016, 49, 66-79.

- Ruana, J.; Urbe, I.; Borrull, F. Determination of phenols at the ng/l level in drinking and river waters by liquid chromatography with UV and electrochemical detection, Journal of Chromatography A 1993, 655, 217-226.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).