Submitted:

12 September 2025

Posted:

16 September 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition

2.2. Timeline of Key Events

2.3. COVID-19 Epidemiological Data

2.4. Analysis of Circulating Variants

2.5. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Implementation of Genomic Surveillance and Sequencing Capacity

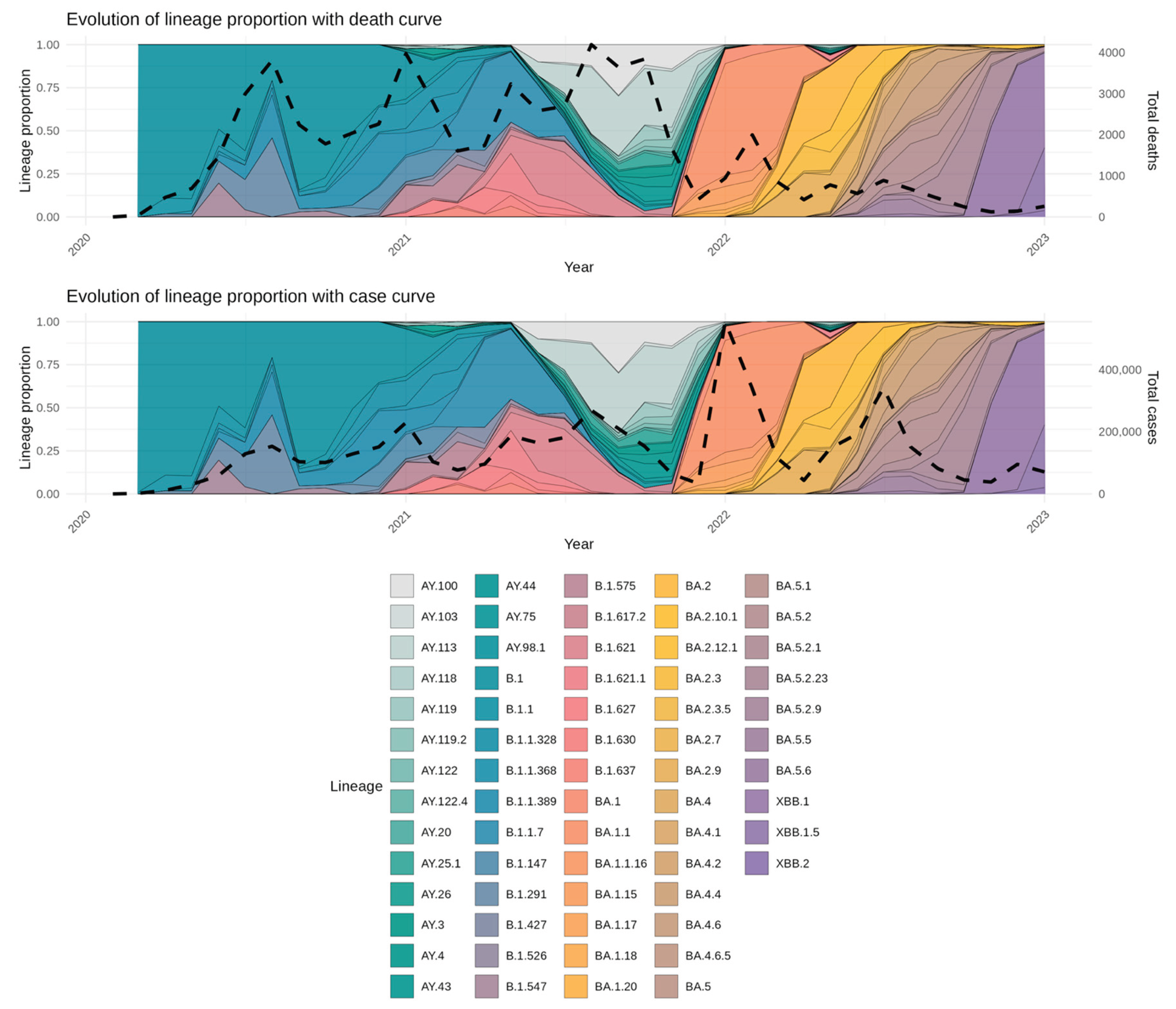

3.2. Circulating Variants and Lineage

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages

3.4. Associations between Lineage Dynamics and Epidemiological Trends

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COMISCA | Council of Ministers of Health of Central America |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| GISAID | Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data |

| ICGES | Instituto Conmemorativo Gorgas de Estudios de la Salud |

| INCIENSA | Instituto Costarricense de Investigación y Enseñanza en Nutrición y Salud |

| PAHO | Pan American Health Organization |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| SARS | Severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| SE-COMISCA | COMISCA Executive Secretary |

| VOC | Variants of concern |

| VOI | Variants of interest |

| VUM | Variants under monitoring |

| WGS | Whole genome sequencing |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X. Lou; Wang, X. G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H. R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C. L.; Chen, H. D.; Chen, J.; Luo, Y.; Guo, H.; Jiang, R. Di; Liu, M. Q.; Chen, Y.; Shen, X. R.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X. S.; Zhao, K.; Chen, Q. J.; Deng, F.; Liu, L. L.; Yan, B.; Zhan, F. X.; Wang, Y. Y.; Xiao, G. F.; Shi, Z. L. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomedica 2020, 91, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Gao, G. F.; Shi, W. The Emergence, Genomic Diversity and Global Spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 600, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants, 2024.

- Pan American Health Organization. Update on the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages and recombination events (18 November 2022), 18 November 1066.

- Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological Update: SARS-CoV-2 variants in the Region of the Americas (1 December 2021), 1 December 1066.

- Singh, P.; Sharma, K.; Shaw, D.; Bhargava, A.; Negi, S. S. Mosaic Recombination Inflicted Various SARS-CoV-2 Lineages to Emerge into Novel Virus Variants: A Review Update. Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2023, 38, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Mora, J. A.; Cordero-Laurent, E.; Godínez, A.; Calderón-Osorno, M.; Brenes, H.; Soto-Garita, C.; Pérez-Corrales, C.; Drexler, J. F.; Moreira-Soto, A.; Corrales-Aguilar, E.; Duarte-Martínez, F. SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance in Costa Rica: Evidence of a Divergent Population and an Increased Detection of a Spike T1117I Mutation. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2021, 92, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Mora, J. A. Insights into the Mutation T1117I in the Spike and the Lineage B.1.1.389 of SARS-CoV-2 Circulating in Costa Rica. Gene Rep 2022, 27, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambaut, A.; Holmes, E. C.; O’Toole, Á.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J. T.; Ruis, C.; du Plessis, L.; Pybus, O. G. A Dynamic Nomenclature Proposal for SARS-CoV-2 Lineages to Assist Genomic Epidemiology. Nat Microbiol 2020, 5, 1403–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oude Munnink, B. B.; Worp, N.; Nieuwenhuijse, D. F.; Sikkema, R. S.; Haagmans, B.; Fouchier, R. A. M.; Koopmans, M. The next Phase of SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance: Real-Time Molecular Epidemiology. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockdale, J. E.; Liu, P.; Colijn, C. The Potential of Genomics for Infectious Disease Forecasting. Nat Microbiol 2022, 7, 1736–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, E.; Ritchie, H.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J.; Macdonald, B.; Dattani, S.; Beltekian, D.; Ortiz-Ospina, E.; Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases.

- O’Toole, Á.; Scher, E.; Underwood, A.; Jackson, B.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J. T.; Colquhoun, R.; Ruis, C.; Abu-Dahab, K.; Taylor, B.; Yeats, C.; du Plessis, L.; Maloney, D.; Medd, N.; Attwood, S. W.; Aanensen, D. M.; Holmes, E. C.; Pybus, O. G.; Rambaut, A. Assignment of Epidemiological Lineages in an Emerging Pandemic Using the Pangolin Tool. Virus Evol 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, T.; Brito, A. F.; Lasek-Nesselquist, E.; Rothman, J.; Valesano, A. L.; MacKay, M. J.; Petrone, M. E.; Breban, M. I.; Watkins, A. E.; Vogels, C. B. F.; Kalinich, C. C.; Dellicour, S.; Russell, A.; Kelly, J. P.; Shudt, M.; Plitnick, J.; Schneider, E.; Fitzsimmons, W. J.; Khullar, G.; Metti, J.; Dudley, J. T.; Nash, M.; Beaubier, N.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.; Hui, P.; Muyombwe, A.; Downing, R.; Razeq, J.; Bart, S. M.; Grills, A.; Morrison, S. M.; Murphy, S.; Neal, C.; Laszlo, E.; Rennert, H.; Cushing, M.; Westblade, L.; Velu, P.; Craney, A.; Cong, L.; Peaper, D. R.; Landry, M. L.; Cook, P. W.; Fauver, J. R.; Mason, C. E.; Lauring, A. S.; St. George, K.; MacCannell, D. R.; Grubaugh, N. D. Early Introductions and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Variant B.1.1.7 in the United States. Cell 2021, 184, 2595–2604e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K. MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Res 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B. Q.; Schmidt, H. A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M. D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B. Q.; Wong, T. K. F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: Fast Model Selection for Accurate Phylogenetic Estimates. Nat Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (ITOL) v4: Recent Updates and New Developments. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, W256–W259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Evaluation of the Pan American Health Organization Response to COVID-19 2020–2022. Volume I. Final Report, 2023. [CrossRef]

- COMISCA. Acuerdo Cooperativo Salud Global COMISCA/CDC apoya el fortalecimiento al Laboratorio INCIENSA, 1278.

- U.S. Census Bureau. International Database (IDB), 2023.

- Taboada, B.; Zárate, S.; García-López, R.; Muñoz-Medina, J. E.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Boukadida, C.; Gómez-Gil, B.; Mojica, N. S.; Rosales-Rivera, M.; Salas-Lais, A. G.; Gutiérrez-Ríos, R. M.; Loza, A.; Rivera-Gutierrez, X.; Vazquez-Perez, J. A.; Matías-Florentino, M.; Pérez-García, M.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Hurtado, J. M.; Herrera-Nájera, C. I.; Núñez-Contreras, J. de J.; Sarquiz-Martínez, B.; García-Arias, V. E.; Santiago-Mauricio, M. G.; Martínez-Miguel, B.; Enciso-Ibarra, J.; Cháidez-Quiróz, C.; Iša, P.; Wong-Chew, R. M.; Jiménez-Corona, M. E.; López, S.; Arias, C. F. Dominance of Three Sublineages of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant in Mexico. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Karuppanan, K.; Subramaniam, G. Omicron (BA.1) and Sub-variants (BA.1.1, BA.2, and BA.3) of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Infectivity and Pathogenicity: A Comparative Sequence and Structural-based Computational Assessment. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 4780–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Ito, J.; Uriu, K.; Zahradnik, J.; Kida, I.; Anraku, Y.; Nasser, H.; Shofa, M.; Oda, Y.; Lytras, S.; Nao, N.; Itakura, Y.; Deguchi, S.; Suzuki, R.; Wang, L.; Begum, M. M.; Kita, S.; Yajima, H.; Sasaki, J.; Sasaki-Tabata, K.; Shimizu, R.; Tsuda, M.; Kosugi, Y.; Fujita, S.; Pan, L.; Sauter, D.; Yoshimatsu, K.; Suzuki, S.; Asakura, H.; Nagashima, M.; Sadamasu, K.; Yoshimura, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Nagamoto, T.; Schreiber, G.; Maenaka, K.; Ito, H.; Misawa, N.; Kimura, I.; Suganami, M.; Chiba, M.; Yoshimura, R.; Yasuda, K.; Iida, K.; Ohsumi, N.; Strange, A. P.; Takahashi, O.; Ichihara, K.; Shibatani, Y.; Nishiuchi, T.; Kato, M.; Ferdous, Z.; Mouri, H.; Shishido, K.; Sawa, H.; Hashimoto, R.; Watanabe, Y.; Sakamoto, A.; Yasuhara, N.; Suzuki, T.; Kimura, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Wu, J.; Shirakawa, K.; Takaori-Kondo, A.; Nagata, K.; Kazuma, Y.; Nomura, R.; Horisawa, Y.; Tashiro, Y.; Kawai, Y.; Irie, T.; Kawabata, R.; Motozono, C.; Toyoda, M.; Ueno, T.; Hashiguchi, T.; Ikeda, T.; Fukuhara, T.; Saito, A.; Tanaka, S.; Matsuno, K.; Takayama, K.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 XBB Variant Derived from Recombination of Two Omicron Subvariants; 2023; Vol. 14. [CrossRef]

- Gardy, J. L.; Loman, N. J. Towards a Genomics-Informed, Real-Time, Global Pathogen Surveillance System. Nat Rev Genet 2018, 19, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, K. A.; Panigrahi, M.; Kumar, H.; Rajawat, D.; Nayak, S. S.; Bhushan, B.; Dutt, T. Role of Genomics in Combating COVID-19 Pandemic. Gene, 20 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durón, R. M.; Sánchez, E.; Choi, J. N.; Peralta, G.; Ventura, S. G.; Soto, R. J.; Rodríguez, G.; Ahrens, C.; Farach, E.; Figueroa, J.; Pineda, G.; Romero, A.; Rodríguez, O.; Discua, D.; Salgado, J. Honduras: Two Hurricanes, COVID-19, Dengue and the Need for a New Digital Health Surveillance System. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2021, 43, e297–e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrek, D.; Speroni, L.; Curnow, K. J.; Oberholzer, M.; Moeder, V.; Febbo, P. G. Genomic Surveillance at Scale Is Required to Detect Newly Emerging Strains at an Early Timepoint. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Brito, A. F.; Semenova, E.; Dudas, G.; Hassler, G. W.; Kalinich, C. C.; Kraemer, M. U. G.; Ho, J.; Tegally, H.; Githinji, G.; Agoti, C. N.; Matkin, L. E.; Whittaker, C.; Kantardjiev, T.; Korsun, N.; Stoitsova, S.; Dimitrova, R.; Trifonova, I.; Dobrinov, V.; Grigorova, L.; Stoykov, I.; Grigorova, I.; Gancheva, A.; Jennison, A.; Leong, L.; Speers, D.; Baird, R.; Cooley, L.; Kennedy, K.; de Ligt, J.; Rawlinson, W.; van Hal, S.; Williamson, D.; Singh, R.; Nathaniel-Girdharrie, S. M.; Edghill, L.; Indar, L.; St. John, J.; Gonzalez-Escobar, G.; Ramkisoon, V.; Brown-Jordan, A.; Ramjag, A.; Mohammed, N.; Foster, J. E.; Potter, I.; Greenaway-Duberry, S.; George, K.; Belmar-George, S.; Lee, J.; Bisasor-McKenzie, J.; Astwood, N.; Sealey-Thomas, R.; Laws, H.; Singh, N.; Oyinloye, A.; McMillan, P.; Hinds, A.; Nandram, N.; Parasram, R.; Khan-Mohammed, Z.; Charles, S.; Andrewin, A.; Johnson, D.; Keizer-Beache, S.; Oura, C.; Pybus, O. G.; Faria, N. R.; Stegger, M.; Albertsen, M.; Fomsgaard, A.; Rasmussen, M.; Khouri, R.; Naveca, F.; Graf, T.; Miyajima, F.; Wallau, G.; Motta, F.; Khare, S.; Freitas, L.; Schiavina, C.; Bach, G.; Schultz, M. B.; Chew, Y. H.; Makheja, M.; Born, P.; Calegario, G.; Romano, S.; Finello, J.; Diallo, A.; Lee, R. T. C.; Xu, Y. N.; Yeo, W.; Tiruvayipati, S.; Yadahalli, S.; Wilkinson, E.; Iranzadeh, A.; Giandhari, J.; Doolabh, D.; Pillay, S.; Ramphal, U.; San, J. E.; Msomi, N.; Mlisana, K.; von Gottberg, A.; Walaza, S.; Ismail, A.; Mohale, T.; Engelbrecht, S.; Van Zyl, G.; Preiser, W.; Sigal, A.; Hardie, D.; Marais, G.; Hsiao, M.; Korsman, S.; Davies, M. A.; Tyers, L.; Mudau, I.; York, D.; Maslo, C.; Goedhals, D.; Abrahams, S.; Laguda-Akingba, O.; Alisoltani-Dehkordi, A.; Godzik, A.; Wibmer, C. K.; Martin, D.; Lessells, R. J.; Bhiman, J. N.; Williamson, C.; de Oliveira, T.; Chen, C.; Nadeau, S.; du Plessis, L.; Beckmann, C.; Redondo, M.; Kobel, O.; Noppen, C.; Seidel, S.; de Souza, N. S.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Topolsky, I.; Jablonski, P.; Fuhrmann, L.; Dreifuss, D.; Jahn, K.; Ferreira, P.; Posada-Céspedes, S.; Beisel, C.; Denes, R.; Feldkamp, M.; Nissen, I.; Santacroce, N.; Burcklen, E.; Aquino, C.; de Gouvea, A. C.; Moccia, M. D.; Grüter, S.; Sykes, T.; Opitz, L.; White, G.; Neff, L.; Popovic, D.; Patrignani, A.; Tracy, J.; Schlapbach, R.; Dermitzakis, E.; Harshman, K.; Xenarios, I.; Pegeot, H.; Cerutti, L.; Penet, D.; Stadler, T.; Howden, B. P.; Sintchenko, V.; Zuckerman, N. S.; Mor, O.; Blankenship, H. M.; de Oliveira, T.; Lin, R. T. P.; Siqueira, M. M.; Resende, P. C.; Vasconcelos, A. T. R.; Spilki, F. R.; Aguiar, R. S.; Alexiev, I.; Ivanov, I. N.; Philipova, I.; Carrington, C. V. F.; Sahadeo, N. S. D.; Branda, B.; Gurry, C.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Naidoo, D.; von Eije, K. J.; Perkins, M. D.; van Kerkhove, M.; Hill, S. C.; Sabino, E. C.; Pybus, O. G.; Dye, C.; Bhatt, S.; Flaxman, S.; Suchard, M. A.; Grubaugh, N. D.; Baele, G.; Faria, N. R. Global Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance. Nat Commun 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, D.; Rego, N.; Resende, P. C.; Tort, F.; Fernández-Calero, T.; Noya, V.; Brandes, M.; Possi, T.; Arleo, M.; Reyes, N.; Victoria, M.; Lizasoain, A.; Castells, M.; Maya, L.; Salvo, M.; Schäffer Gregianini, T.; Mar da Rosa, M. T.; Garay Martins, L.; Alonso, C.; Vega, Y.; Salazar, C.; Ferrés, I.; Smircich, P.; Sotelo Silveira, J.; Fort, R. S.; Mathó, C.; Arantes, I.; Appolinario, L.; Mendonça, A. C.; Benítez-Galeano, M. J.; Simoes, C.; Graña, M.; Motta, F.; Siqueira, M. M.; Bello, G.; Colina, R.; Spangenberg, L. Recurrent Dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 Through the Uruguayan–Brazilian Border. Front Microbiol 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniz-Mondolfi, A.; Muñoz, M.; Florez, C.; Gomez, S.; Rico, A.; Pardo, L.; Barros, E. C.; Hernández, C.; Delgado, L.; Jaimes, J. E.; Pérez, L.; Teherán, A. A.; Alshammary, H. A.; Obla, A.; Khan, Z.; Dutta, J.; van de Guchte, A.; Gonzalez-Reiche, A. S.; Hernandez, M. M.; Sordillo, E. M.; Simon, V.; van Bakel, H.; Llewellyn, M. S.; Ramírez, J. D. SARS-CoV-2 Spread across the Colombian-Venezuelan Border. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño, L. H.; Ballesteros, N.; Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, A. L.; Luna, N.; Castañeda, S.; Gutierrez-Marin, R.; Mendoza-Ibarra, J. A.; Rodriguez, R.; Bohada, D. P.; Ramírez, J. D.; Paniz-Mondolfi, A. Mu SARS-CoV-2 (B.1.621) Variant: A Genomic Snapshot across the Colombian-Venezuelan Border. J Med Virol 2023, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodcroft, E. B.; Zuber, M.; Nadeau, S.; Vaughan, T. G.; Crawford, K. H. D.; Althaus, C. L.; Reichmuth, M. L.; Bowen, J. E.; Walls, A. C.; Corti, D.; Bloom, J. D.; Veesler, D.; Mateo, D.; Hernando, A.; Comas, I.; González-Candelas, F.; González-Candelas, F.; Goig, G. A.; Chiner-Oms, Á.; Cancino-Muñoz, I.; López, M. G.; Torres-Puente, M.; Gomez-Navarro, I.; Jiménez-Serrano, S.; Ruiz-Roldán, L.; Bracho, M. A.; García-González, N.; Martínez-Priego, L.; Galán-Vendrell, I.; Ruiz-Hueso, P.; De Marco, G.; Ferrús, M. L.; Carbó-Ramírez, S.; D’Auria, G.; Coscollá, M.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, P.; Roig-Sena, F. J.; Sanmartín, I.; Garcia-Souto, D.; Pequeno-Valtierra, A.; Tubio, J. M. C.; Rodríguez-Castro, J.; Rabella, N.; Navarro, F.; Miró, E.; Rodríguez-Iglesias, M.; Galán-Sanchez, F.; Rodriguez-Pallares, S.; de Toro, M.; Escudero, M. B.; Azcona-Gutiérrez, J. M.; Alberdi, M. B.; Mayor, A.; García-Basteiro, A. L.; Moncunill, G.; Dobaño, C.; Cisteró, P.; García-de-Viedma, D.; Pérez-Lago, L.; Herranz, M.; Sicilia, J.; Catalán-Alonso, P.; Muñoz, P.; Muñoz-Cuevas, C.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, G.; Alberola-Enguidanos, J.; Nogueira, J. M.; Camarena, J. J.; Rezusta, A.; Tristancho-Baró, A.; Milagro, A.; Martínez-Cameo, N. F.; Gracia-Grataloup, Y.; Martró, E.; Bordoy, A. E.; Not, A.; Antuori-Torres, A.; Benito, R.; Algarate, S.; Bueno, J.; del Pozo, J. L.; Boga, J. A.; Castelló-Abietar, C.; Rojo-Alba, S.; Alvarez-Argüelles, M. E.; Melon, S.; Aranzamendi-Zaldumbide, M.; Vergara-Gómez, A.; Fernández-Pinero, J.; Martínez, M. J.; Vila, J.; Rubio, E.; Peiró-Mestres, A.; Navero-Castillejos, J.; Posada, D.; Valverde, D.; Estévez-Gómez, N.; Fernandez-Silva, I.; de Chiara, L.; Gallego-García, P.; Varela, N.; Moreno, R.; Tirado, M. D.; Gomez-Pinedo, U.; Gozalo-Margüello, M.; Eliecer-Cano, M.; Méndez-Legaza, J. M.; Rodríguez-Lozano, J.; Siller, M.; Pablo-Marcos, D.; Oliver, A.; Reina, J.; López-Causapé, C.; Canut-Blasco, A.; Hernáez-Crespo, S.; Cordón, M. L. A.; Lecároz-Agara, M. C.; Gómez-González, C.; Aguirre-Quiñonero, A.; López-Mirones, J. I.; Fernández-Torres, M.; Almela-Ferrer, M. R.; Gonzalo-Jiménez, N.; Ruiz-García, M. M.; Galiana, A.; Sanchez-Almendro, J.; Cilla, G.; Montes, M.; Piñeiro, L.; Sorarrain, A.; Marimón, J. M.; Gomez-Ruiz, M. D.; López-Hontangas, J. L.; González Barberá, E. M.; Navarro-Marí, J. M.; Pedrosa-Corral, I.; Sanbonmatsu-Gámez, S.; Pérez-González, C.; Chamizo-López, F.; Bordes-Benítez, A.; Navarro, D.; Albert, E.; Torres, I.; Gascón, I.; Torregrosa-Hetland, C. J.; Pastor-Boix, E.; Cascales-Ramos, P.; Fuster-Escrivá, B.; Gimeno-Cardona, C.; Ocete, M. D.; Medina-Gonzalez, R.; González-Cantó, J.; Martínez-Macias, O.; Palop-Borrás, B.; de Toro, I.; Mediavilla-Gradolph, M. C.; Pérez-Ruiz, M.; González-Recio, Ó.; Gutiérrez-Rivas, M.; Simarro-Córdoba, E.; Lozano-Serra, J.; Robles-Fonseca, L.; de Salazar, A.; Viñuela-González, L.; Chueca, N.; García, F.; Gómez-Camarasa, C.; Carvajal, A.; de la Puente, R.; Martín-Sánchez, V.; Fregeneda-Grandes, J. M.; Molina, A. J.; Argüello, H.; Fernández-Villa, T.; Farga-Martí, M. A.; Domínguez-Márquez, V.; Costa-Alcalde, J. J.; Trastoy, R.; Barbeito-Castiñeiras, G.; Coira, A.; Pérez-del-Molino, M. L.; Aguilera, A.; Planas, A. M.; Soriano, A.; Fernandez-Cádenas, I.; Pérez-Tur, J.; Marcos, M. Á.; Moreno-Docón, A.; Viedma, E.; Mingorance, J.; Galán-Montemayor, J. C.; Parra-Grande, M.; Stadler, T.; Neher, R. A. Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 Variant through Europe in the Summer of 2020. Nature 2021, 595, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serwin, K.; Aksak-Was˛, B.; Parczewski, M. Phylodynamic Dispersal of SARS-CoV-2 Lineages Circulating across Polish–German Border Provinces. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Mrig, S.; Goldust, Y.; Kroumpouzos, G.; Karadağ, A. S.; Rudnicka, L.; Galadari, H.; Szepietowski, J. C.; Di Lernia, V.; Goren, A.; Kassir, M.; Goldust, M. New Coronavirus (Sars-Cov-2) Crossing Borders beyond Cities, Nations, and Continents: Impact of International Travel. Balkan Med J 2021, 38, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Y.; Smith, D. M. SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern. Yonsei Med J 2021, 62, 961–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zárate, S.; Taboada, B.; Muñoz-Medina, J. E.; Iša, P.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Boukadida, C.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Selem Mojica, N.; Rosales-Rivera, M.; Gómez-Gil, B.; Salas-Lais, A. G.; Santacruz-Tinoco, C. E.; Montoya-Fuentes, H.; Alvarado-Yaah, J. E.; Molina-Salinas, G. M.; Espinoza-Ayala, G. E.; Enciso-Moreno, J. A.; Gutiérrez-Ríos, R. M.; Loza, A.; Moreno-Contreras, J.; García-López, R.; Rivera-Gutierrez, X.; Comas-García, A.; Wong-Chew, R. M.; Jiménez-Corona, M.-E.; del Angel, R. M.; Vazquez-Perez, J. A.; Matías-Florentino, M.; Pérez-García, M.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Castelán-Sánchez, H. G.; Delaye, L.; Martínez-Castilla, L. P.; Escalera-Zamudio, M.; López, S.; Arias, C. F. The Alpha Variant (B.1.1.7) of SARS-CoV-2 Failed to Become Dominant in Mexico. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, P.; Trentini, F.; Guzzetta, G.; Marziano, V.; Mammone, A.; Schepisi, M. S.; Poletti, P.; Grané, C. M.; Manica, M.; del Manso, M.; Andrianou, X.; Ajelli, M.; Rezza, G.; Brusaferro, S.; Merler, S.; Di Martino, A.; Ambrosio, L.; Lo Presti, A.; Fiore, S.; Fabiani, C.; Benedetti, E.; Di Mario, G.; Facchini, M.; Puzelli, S.; Calzoletti, L.; Fontana, S.; Venturi, G.; Fortuna, C.; Marsili, G.; Amendola, A.; Stuppia, L.; Savini, G.; Picerno, A.; Lopizzo, T.; Dell’Edera, D.; Minchella, P.; Greco, F.; Viglietto, G.; Atripaldi, L.; Limone, A.; D’Agaro, P.; Licastro, D.; Pongolini, S.; Sambri, V.; Dirani, G.; Zannoli, S.; Affanni, P.; Colucci, M. E.; Capobianchi, M. R.; Icardi, G.; Bruzzone, B.; Lillo, F.; Orsi, A.; Pariani, E.; Baldanti, F.; Molecolare, U. V.; Gismondo, M. R.; Maggi, F.; Caruso, A.; Ceriotti, F.; Boniotti, M. B.; Barbieri, I.; Bagnarelli, P.; Menzo, S.; Garofalo, S.; Scutellà, M.; Pagani, E.; Collini, L.; Ghisetti, V.; Brossa, S.; Ru, G.; Bozzetta, E.; Chironna, M.; Parisi, A.; Rubino, S.; Serra, C.; Piras, G.; Coghe, F.; Vitale, F.; Tramuto, F.; Scalia, G.; Palermo, C. I.; Mancuso, G.; Pollicino, T.; Di Gaudio, F.; Vullo, S.; Reale, S.; Cusi, M. G.; Rossolini, G. M.; Pistello, M.; Mencacci, A.; Camilloni, B.; Severini, S.; Di Benedetto, M.; Terregino, C.; Monne, I.; Biscaro, V. Co-Circulation of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha and Gamma Variants in Italy, February and March 2021. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oróstica, K. Y.; Mohr, S. B.; Dehning, J.; Bauer, S.; Medina-Ortiz, D.; Iftekhar, E. N.; Mujica, K.; Covarrubias, P. C.; Ulloa, S.; Castillo, A. E.; Daza-Sánchez, A.; Verdugo, R. A.; Fernández, J.; Olivera-Nappa, Á.; Priesemann, V.; Contreras, S. Early Mutational Signatures and Transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 Gamma and Lambda Variants in Chile. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, F.; Kamali, N.; Bezmin Abadi, A. T. The Mu Strain: The Last but Not Least Circulating Variant of Interest’ Potentially Affecting the COVID-19 Pandemic. Future Virology, 1 January 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanetti, M.; Fonseca, V.; Wilkinson, E.; Tegally, H.; San, E. J.; Althaus, C. L.; Xavier, J.; Nanev Slavov, S.; Viala, V. L.; Ranieri Jerônimo Lima, A.; Ribeiro, G.; Souza-Neto, J. A.; Fukumasu, H.; Lehmann Coutinho, L.; Venancio Da Cunha, R.; Freitas, C.; Campelo De A E Melo, C. F.; Navegantes De Araújo, W.; Do Carmo Said, R. F.; Almiron, M.; De Oliveira, T.; Coccuzzo Sampaio, S.; Elias, M. C.; Covas, D. T.; Holmes, E. C.; Lourenço, J.; Kashima, S.; De Alcantara, L. C. J. Replacement of the Gamma by the Delta Variant in Brazil: Impact of Lineage Displacement on the Ongoing Pandemic. Virus Evol 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fall, A.; Eldesouki, R. E.; Sachithanandham, J.; Morris, C. P.; Norton, J. M.; Gaston, D. C.; Forman, M.; Abdullah, O.; Gallagher, N.; Li, M.; Swanson, N. J.; Pekosz, A.; Klein, E. Y.; Mostafa, H. H.; Feinstone, W. H. The Displacement of the SARS-CoV-2 Variant Delta with Omicron: An Investigation of Hospital Admissions and Upper Respiratory Viral Loads. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Long, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, C.; Liu, W. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 Recombinants and Emerging Omicron Sublineages. Int J Med Sci 2023, 20, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W. L.; Armas, F.; Guarneri, F.; Gu, X.; Formenti, N.; Wu, F.; Chandra, F.; Parisio, G.; Chen, H.; Xiao, A.; Romeo, C.; Scali, F.; Tonni, M.; Leifels, M.; Chua, F. J. D.; Kwok, G. W.; Tay, J. Y.; Pasquali, P.; Thompson, J.; Alborali, G. L.; Alm, E. J. Rapid Displacement of SARS-CoV-2 Variant Delta by Omicron Revealed by Allele-Specific PCR in Wastewater. Water Res 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, M.; Lau, L. S.; Pokharel, M. D.; Ramelow, J.; Owens, F.; Souchak, J.; Akkaoui, J.; Ales, E.; Brown, H.; Shil, R.; Nazaire, V.; Manevski, M.; Paul, N. P.; Esteban-Lopez, M.; Ceyhan, Y.; El-Hage, N. From Alpha to Omicron: How Different Variants of Concern of the SARS-Coronavirus-2 Impacted the World. Biology (Basel) 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, R.; Tripathi, S. Enhanced Recombination Among SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variants Contributes to Viral Immune Escape. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Paulino-Ramírez, R.; Pham, K.; Breban, M. I.; Peguero, A.; Jabier, M.; Sánchez, N.; Eustate, I.; Ruiz, I.; Grubaugh, N. D.; Hahn, A. M. Genome Sequence of a Recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Lineage XAM (BA.1.1/BA.2.9) Strain from a Clinical Sample in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. Microbiol Resour Announc 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Iketani, S.; Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Bowen, A. D.; Liu, M.; Wang, M.; Yu, J.; Valdez, R.; Lauring, A. S.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, H. H.; Gordon, A.; Liu, L.; Ho, D. D. Alarming Antibody Evasion Properties of Rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB Subvariants. Cell 2023, 186, 279–286e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parums, D. V. Editorial: The XBB.1.5 (‘Kraken’) Subvariant of Omicron SARS-CoV-2 and Its Rapid Global Spread. Medical Science Monitor, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, L. What to Know about Omicron XBB.1.5. CMAJ. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2023, 195, E127–E128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A. F.; Semenova, E.; Dudas, G.; Hassler, G. W.; Kalinich, C. C.; Kraemer, M. U. G.; Ho, J.; Tegally, H.; Githinji, G.; Agoti, C. N.; Matkin, L. E.; Whittaker, C.; Howden, B. P.; Sintchenko, V.; Zuckerman, N. S.; Mor, O.; Blankenship, H. M.; Oliveira, T. de; Lin, R. T. P.; Siqueira, M. M.; Resende, P. C.; Vasconcelos, A. T. R.; Spilki, F. R.; Aguiar, R. S.; Alexiev, I.; Ivanov, I. N.; Philipova, I.; Carrington, C. V. F.; Sahadeo, N. S. D.; Gurry, C.; Maurer-Stroh, S.; Naidoo, D.; von Eije, K. J.; Perkins, M. D.; Kerkhove, M. van; Hill, S. C.; Sabino, E. C.; Pybus, O. G.; Dye, C.; Bhatt, S.; Flaxman, S.; Suchard, M. A.; Grubaugh, N. D.; Baele, G.; Faria, N. R. Global Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 Genomic Surveillance. , 2021. 26 August. [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, N. E.; Price, V.; Cunningham-Oakes, E.; Tsang, K. K.; Nunn, J. G.; Midega, J. T.; Anjum, M. F.; Wade, M. J.; Feasey, N. A.; Peacock, S. J.; Jauneikaite, E.; Baker, K. S. Innovations in Genomic Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance. The Lancet Microbe, 1 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, D.; Ghosh, A.; Jha, A.; Prasad, P.; Raghav, S. K. Impact of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 evolution and immune escape variants. Vaccine 2024, 42(21), 126153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.; Gonzalez, C.; Abrego, L. E.; Carrera, J. P.; Diaz, Y.; Caicedo, Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics, spread, and genomic characterization of SARS-CoV-2 in Panama. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, 27(2), 612–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datos Abiertos de Panamá. Migración - Irregulares en tránsito por Darién por país 2022 (16 de enero de 2023). 2022.

- Cumbrera, A.; Calzada, J. E.; Chaves, L. F.; Hurtado, L. A. Spatiotemporal analysis of malaria transmission in the autonomous indigenous regions of Panama, Central America, 2015–2022. Trop Med Infect Dis 2024, 9(4), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Mora, J. A.; Reales-González, J.; Camacho, E.; Duarte-Martínez, F.; Tsukayama, P.; Soto-Garita, C.; Brenes, H.; Cordero-Laurent, E.; Ribeiro dos Santos, A.; Guedes Salgado, C.; Santos Silva, C.; Santana de Souza, J.; Nunes, G.; Negri, T.; Vidal, A.; Oliveira, R.; Oliveira, G.; Muñoz-Medina, J. E.; Salas-Lais, A. G.; Mireles-Rivera, G.; Sosa, E.; Turjanski, A.; Monzani, M. C.; Carobene, M. G.; Remes Lenicov, F.; Schottlender, G.; Fernández Do Porto, D. A.; Kreuze, J. F.; Sacristán, L.; Guevara-Suarez, M.; Cristancho, M.; Campos-Sánchez, R.; Herrera-Estrella, A. Overview of the SARS-CoV-2 Genotypes Circulating in Latin America during 2021. Front Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concha-Toloza, M.; González, L. C.; Estrella, A. H. H.; Porto, D. F. Do; Campos-Sánchez, R.; Molina-Mora, J. A. Genomic, Socio-Environmental, and Sequencing Capability Patterns in the Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in Latin America and the Caribbean up to 2023. , 2024. 15 November. [CrossRef]

- Lira-Morales, J. D.; López-Cuevas, O.; Medrano-Félix, J. A.; González-Gómez, J. P.; González-López, I.; Castro-Del Campo, N.; Gomez-Gil, B.; Chaidez, C. Genomic Surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 in México: Three Years since Wuhan, China’s First Reported Case. Viruses 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro Dias, M. F.; Andriolo, B. V.; Silvestre, D. H.; Cascabulho, P. L.; Leal da Silva, M. Genomic Surveillance and Sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 across South America. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 2023, 47, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Country | COVID-19 Cases per Million | Total deaths | Total reported COVID-19 cases |

Total sequenced SARS-CoV-2 Samples |

Percentage of Sequenced COVID-19 Cases (%) |

Genomes Retrieved from GISAID* | Completeness Average (%)* | Sequences with ≥95% Coverage and <6% Ambiguities* | Sequences that met the quality criteria (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 174,223.1 | 688 | 70,610 | 1,183 | 1.68 | 1,071 | 99.37 | 970 | 90.57 |

| Costa Rica | 228,954.6 | 9,158 | 1,186,176 | 9,960 | 0.84 | 9,921 | 99.35 | 9,865 | 99.44 |

| Dominican Republic | 58,793.97 | 4,384 | 660,187 | 2,628 | 0.40 | 2,585 | 99.46 | 2,345 | 90.72 |

| El Salvador | 31,845.41 | 4,230 | 201,785 | 914 | 0.45 | 633 | 99.48 | 616 | 97.31 |

| Guatemala | 68,736.55 | 20,092 | 1,226,529 | 4,623 | 0.38 | 4,504 | 99.32 | 4,053 | 89.99 |

| Honduras | 45,103.27 | 11,104 | 470,556 | 287 | 0.06 | 233 | 99.43 | 225 | 96.57 |

| Nicaragua | 2,240.661 | 245 | 15,569 | 1,065 | 6.84 | 1,064 | 98.79 | 768 | 72.18 |

| Panama | 23,3567.4 | 8,596 | 1,029,701 | 6,613 | 0.64 | 6,584 | 99.28 | 6,343 | 96.34 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).