1. Introduction

Older adults frequently experience age-related changes, including cognitive and physical decline (which can be painful), increased stress, sleep disturbances, or mood dysregulation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Providing tools for managing these situations is an unavoidable challenge for improving the living conditions of older adults. Non-invasive interventions such as neurofeedback (NFB) and binaural stimuli (BS) have garnered interest as adjunct therapies to improve brain function, emotional balance, and overall quality of life [

7].

Although there is little clinical information describing the potential use of NFB and BS to improve the quality of life of older adults [

8,

9,

10], for the well-being of these persons, the NFB and BS system could be a valuable tool to manage chronic pain (always with the supervision of health services through nursing management) by using real-time monitoring of brain activity to promote self-regulation and pain relief.

Regarding the effectiveness of these techniques, evidence was found. However, the heterogeneity in study protocols-made it very challenging to determine an optimal protocol for NFB administration [

9,

11,

12]. This pilot study explores the feasibility and impact of NFB training on cognitive performance in elderly individuals, reporting preliminary improvements in their cognitive abilities.

1.1. Background on Neurofeedback

Basically, NFB, as a non-invasive therapy, allows people to be trained to modify their brain activity through real-time feedback, which could be very useful in nursing care. This group of techniques constitutes a form of biofeedback that relies on monitoring brain activity (usually using electroencephalography (EEG) or functional near-infrared spectroscopy to measure brain wave patterns). The hypothesis is that patients can learn to adjust these patterns through visual or auditory cues [

13], which would provide real-time feedback that would allow them to optimize their brain function [

2,

3,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. This would be achieved by reinforcing the desired brain wave patterns through visual or auditory feedback. Thus, for example, to relieve pain, NFB can reduce pain perception by modulating alpha (8-12 Hz) and theta (4-7 Hz) waves, associated with relaxation and pain tolerance [

19,

20,

21]. This process would be based on the neuroplasticity of the brain, which gives it the remarkable ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections.

1.2. Types of NFB Training

Various types of NFB protocols have been developed, each with unique methodologies and clinical applications [

2,

3,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

22]. Each type of NFB training offers distinct advantages, and the choice of method is typically guided by the individual’s clinical presentation, specific treatment goals, and the targeted neural processes. As research advances, these techniques continue to evolve, expanding their potential applications in both clinical and performance-enhancement settings.

The most conventional method is EEG NFB, which uses scalp sensors to capture electrical brain activity across frequency bands (e.g., delta, theta, alpha, beta). By reinforcing desired brainwave patterns and inhibiting undesired ones, traditional EEG NFB aims to enhance cognitive performance, emotional regulation, and overall mental well-being [

19,

20,

21].

This study presents a design that explores the experiences associated with a traditional EEG NFB-based program and binaural beat music stimuli (BS). Binaural beats are an auditory phenomenon created when two slightly different frequencies are presented separately to each ear [

23]. The brain perceives a third “beat” frequency, which may influence brainwave activity [

24]. By targeting specific frequency bands (e.g., theta for relaxation, alpha for meditative states), BS may entrain neural oscillations associated with desired mental states. These stimuli have been investigated for stress reduction (like management of pain, improved sleep quality or enhanced cognitive processing). BS are typically delivered via headphones during quiet, controlled sessions and can be easily integrated into a patient’s routine [

25,

26,

27].

This technique is used to influence brainwave activity and has been studied for its effects on pain relief and cognitive performance. Specifically, delta (0.5–4 Hz) and theta (4–8 Hz) BS have been linked to relaxation, stress reduction, and pain relief. Some research suggests that listening to these frequencies can modulate pain perception and promote relaxation, helping to manage chronic pain in older adults [

28].

The combined use of NFB and BS may offer synergistic benefits by enhancing brainwave Modulation. NFB provides direct, individualized training in regulating brain activity, while BS can prime the brain for relaxation or cognitive engagement. This combined approach could also facilitate multimodal intervention, as it may address both the physiological and psychological aspects of aging, leading to better outcomes in mood regulation and overall well-being.

The interactive nature of NFB, complemented by the passive listening experience of BS, may increase patient adherence and engagement in therapy routine [

25,

26,

27,

29]. Ultimately, this combination of NFB may provide enhanced benefits for older adults by amplifying cognitive training effects, leading to better focus and memory retention. It may also strengthen neural networks that help with pain processing and perception, promoting deep relaxation, which aids in pain relief and mental clarity.

1.3. Neurofeedback and Bianural Stimuli for Concentration and Pain Management

The incidence of pain is reported to reach 73% among community-dwelling older adults and 80% among those living in nursing homes, so there is a clear risk that the incidence of some types of age-related pain will increase daily. Notably, it is not restricted to chronic pain alone; studies have demonstrated that acute pain is also poorly managed among this population. Common non-malignant pain conditions seen in older people include osteoarthritis, post herpetic neuralgia, post-stroke pain or diabetic neuropathy [

30]. Then, there is no doubt that developing and testing new, multimodal strategies to reduce the onset and impact of pain in older adults is crucial.

Because NFB and BS represent promising complementary interventions for improving quality of life in older adults (although preliminary evidence is encouraging), further controlled studies are needed to optimize protocols and verify long-term benefits. Specifically NFB training could modulate pain perception and reduce chronic pain symptoms by training patients to control brain activity associated with pain processing [

31,

32]. It has been used to improve emotional resilience and reduce negative mood, particularly by targeting the right hemisphere of the brain, which is involved in stress and pain processing [

33,

34].

By directly influencing brain wave activity and promoting self-regulation, these techniques may help mitigate age-related physical, cognitive, and emotional challenges. However, further clinical trials are needed to establish standardized protocols and long-term efficacy. In parallel, considering the target population, it is important to develop easy-to-use devices that combine NFB EEG with BS administration [

25,

26,

27,

29], in order to standardize their use given the promising results.

Finally, it is important to highlight that their use to date has shown that NFB and BS are safe for most people, but they should be guided by a trained professional to avoid overstimulation or fatigue. For example, BS should not be used by people suffering from epilepsy or severe auditory processing disorders, and patients should be monitored for both improvements and possible side effects, such as mild headaches or dizziness [

25,

26,

27,

29].

2. Materials and Methods

This comprehensive technical protocol integrating a multi-dimensional assessment strategy, combining standardized testing principles, and quantitative metrics. The protocol is divided into several phases that cover initial screening, controlled testing, data collection, and analysis.

2.1. Preparing the Pilot Test Equipment. Participant Information and Selection Criteria

Proper data collection and management, a standardized testing environment, and proper equipment distribution were ensured. All tests were conducted in the same quiet room, with uniform lighting and minimal distractions. Devices (recorders, computers) were calibrated before each session.

2.1.1. Eligibility Screening

Pre-screening is used to determine whether potential participants are eligible to participate in their research study (based on exclusion and inclusion criteria). In this pilot study were: Age range (adults over 55 years of age), native language fluency and level of education higher than high school, and absence of sensory impairments (or documented accommodations).

2.1.2. Pre-Test Briefing

Before the start of the pilot test, all the selected participants were informed about the objectives of the evaluation, clearly explained study procedures and any potential risks or benefits for obtaining informed consent, ensuring the success and viability of the aforementioned test. However, information regarding therapeutic treatments and cognitive or other diseases was collected. To reduce gender bias, participants were selected to ensure an equal percentage of men and women. Initially, all participants completed an informed consent form (ethical committee approval code US PEIBA: 1553-N-22).

For data collection, the protocol ensured compliance with data privacy regulations (anonymization, secure storage). In addition, inter-rater reliability measures were taken. Therefore, for comfort level scoring, at least two independent raters were required to score each response. Inter-rater agreement was calculated using Cohe

n’s kappa statistic. The kappa statistic is used to assess inter-rater reliability. The importance of inter-rater reliability is that it represents the degree to which the data collected in the study are accurate representations of the measured variables [

35]. By incorporating these rigorous quality control procedures, this framework provides a comprehensive method for exploring the effectiveness of NFB BS tools in improving subject

s’ ability to maintain concentration and, ultimately, in managing their cognitive abilities (which can greatly assist them in coping with painful events).

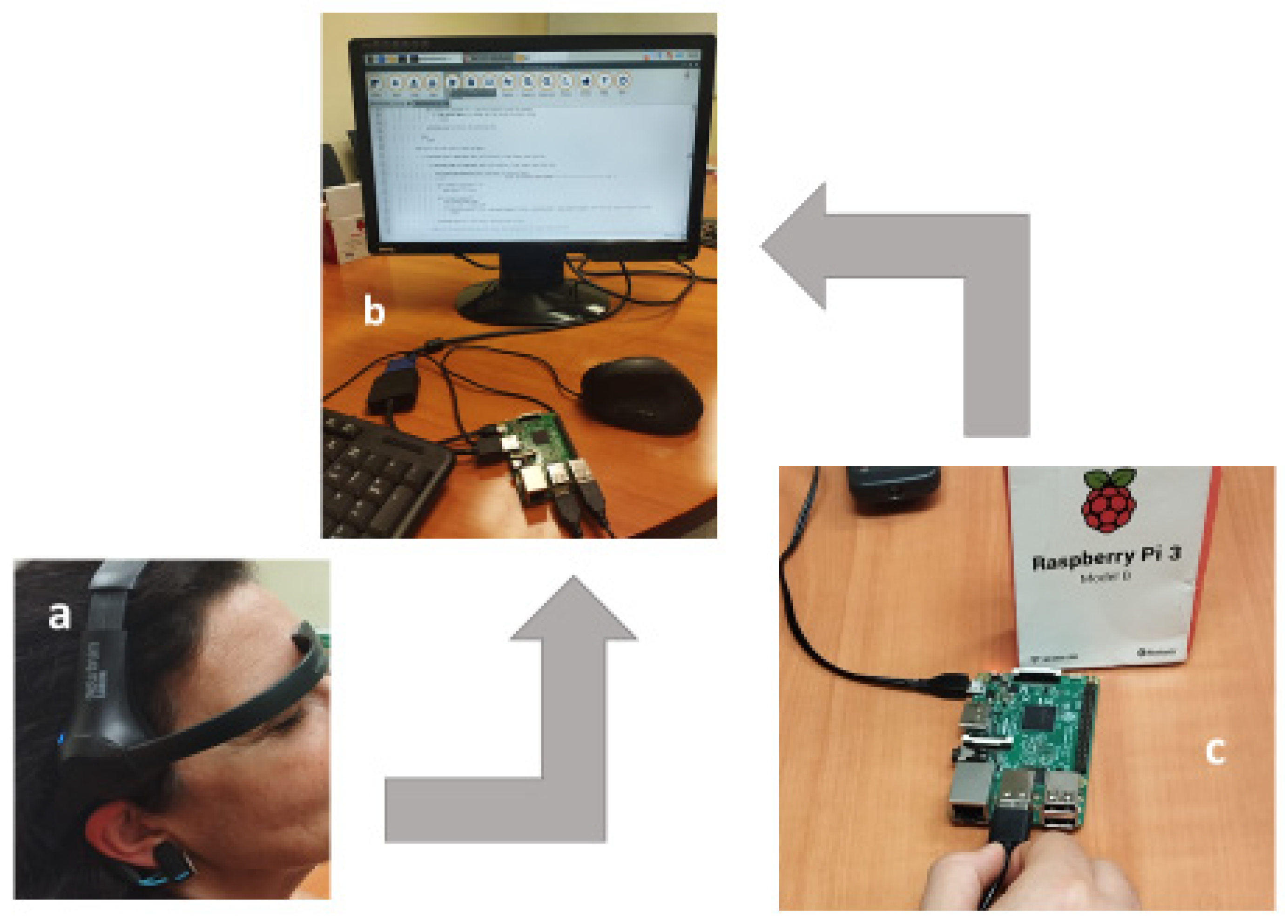

2.1.3. Neurofeedback Designed Device: Instrumentation, Measurement Tools and Digital Recording

The NBF device (MindWave Mobile 2

TM, NeuroSky INC., Silicon Valley Headquarters, San Jose, CA, USA [

36]) was used as a cerebral activity feedback system, using an auditive simulation way to improve mental status. The emission of BS was used to test the improving the ability for concentration of the participants. This device is a low-cost EEG system widely used in NFB training, meditation, and cognitive state monitoring. It measures brainwave activity through a single dry electrode placed on the forehead and an ear clip that serves as a grounding mechanism to reduce electrical noise. The collected EEG signals allow for real-time monitoring of attention states.

The NeuroSky headset was wirelessly connected to a Raspberry Pi 3B

TM (Raspberry Pi Foundation, UK [

37]) via Bluetooth to process real-time EEG data and adjust the auditory stimuli accordingly. The headphones were connected to the Raspberry Pi, and the Mindwave Mobile headset was positioned on the participants according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The frontal electrode of the headset was placed on the forehead, while the ear clip provided a grounding connection to minimize electrical noise. The headphones were connected to the Raspberry Pi, allowing participants to listen to BS that were adjusted based on their real-time EEG activity.

The following setup procedure was as follows (

Figure 1):

1. The Flex cable is connected to the low screen plaque. The connector cover is removed and the display cable is inserted in the Flex connector in the Raspberry.

2. The microUSB/USB cable is connected to the screen for power supply. The microUSB plugs into the “PWR IN” in the lower plaque of the screen. The USB is connected to the USB port in the Raspberry Pi.

3. Raspberry Pi is connected to the power and it is switched on. It was used the software Onboard to get a keyboard in the screen.

4. The console is opened in the tools bar.

5. Mindwave mobile is now switched on using matchup mode.

6. Now, it should be typed the following commands to connect to the diadem NeurosSky by Bluetooth:

Active Bluetooth

Initiate matchup mode

Matchup device

Exit from Bluetooth tool

Connection established

Using the MAC address of Mindwave Mobile to be connected.

7. Mu Editor is used to run the commands.

Finally, all the settings were connected to the system and Mindwave Mobile diadem was placed in the participants head according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The headset’s frontal electrode was placed on the forehead, while the ear clip provided a grounding connection to reduce electrical noise. Headphones allowed participants to listen to BSbeats adapted to their real-time EEG activity.

2.2. Procedure: Protocol Overview

Participants must read two popular science texts of similar complexity. The texts will be provided by the experimentation team, and they include several questions about the level of complexity of reading (

Figure 2). The test is conducted as follows (

Figure 1): The subject put on headphones. The participant has not been previously informed of the time at which the sound stimulus will begin. Then, the person received the first text (in fact, this test is the control because no sound is applied by the headphones). This first reading constitutes the baseline phase. The recording lasted as long as the participant took to complete the reading. Then, when the subject finished reading and answered the questionnaire, the text is taken away (

Figure 2).

After a brief pause, a second text was provided. Simultaneously, binaural tones began playing through the headphones. Finished the reading the participants answered the questionnaire again (

Figure 2).

Finally, the participants were interviewed to determine their comfort level with the system and whether they noticed any difference in attention span between the two texts read.

2.3. Signal Acquisition and Interpretation

As the manufacturer describes in [

36], the NeuroSky headset measured brain activity through a dry forehead electrode and an earlobe reference clip. The forehead electrode detected electrical signals primarily originating from the prefrontal cortex, and although optimized for brainwaves, it could also pick up electromyographic (EMG) signals caused by facial muscle activity.

Participants were instructed to minimize muscle contractions to ensure a cleaner EEG recording. The earlobe clip did not detect brainwaves but served as a reference point, allowing differential amplification of the EEG signal and reducing external electrical interference. The NeuroSky device uses a proprietary adaptive algorithm that adjusts dynamically to each participant’s natural brainwave variability, enhancing data robustness across a wide range of individuals and environmental conditions.

Data was recorded and downloaded as CSV files and processing was done using Microsoft ExcelTM.

3. Results

The pilot test was conducted on a group of four people (two women and two men) with similar academic backgrounds (all participants had higher education) and also similar ages (55-65 years).

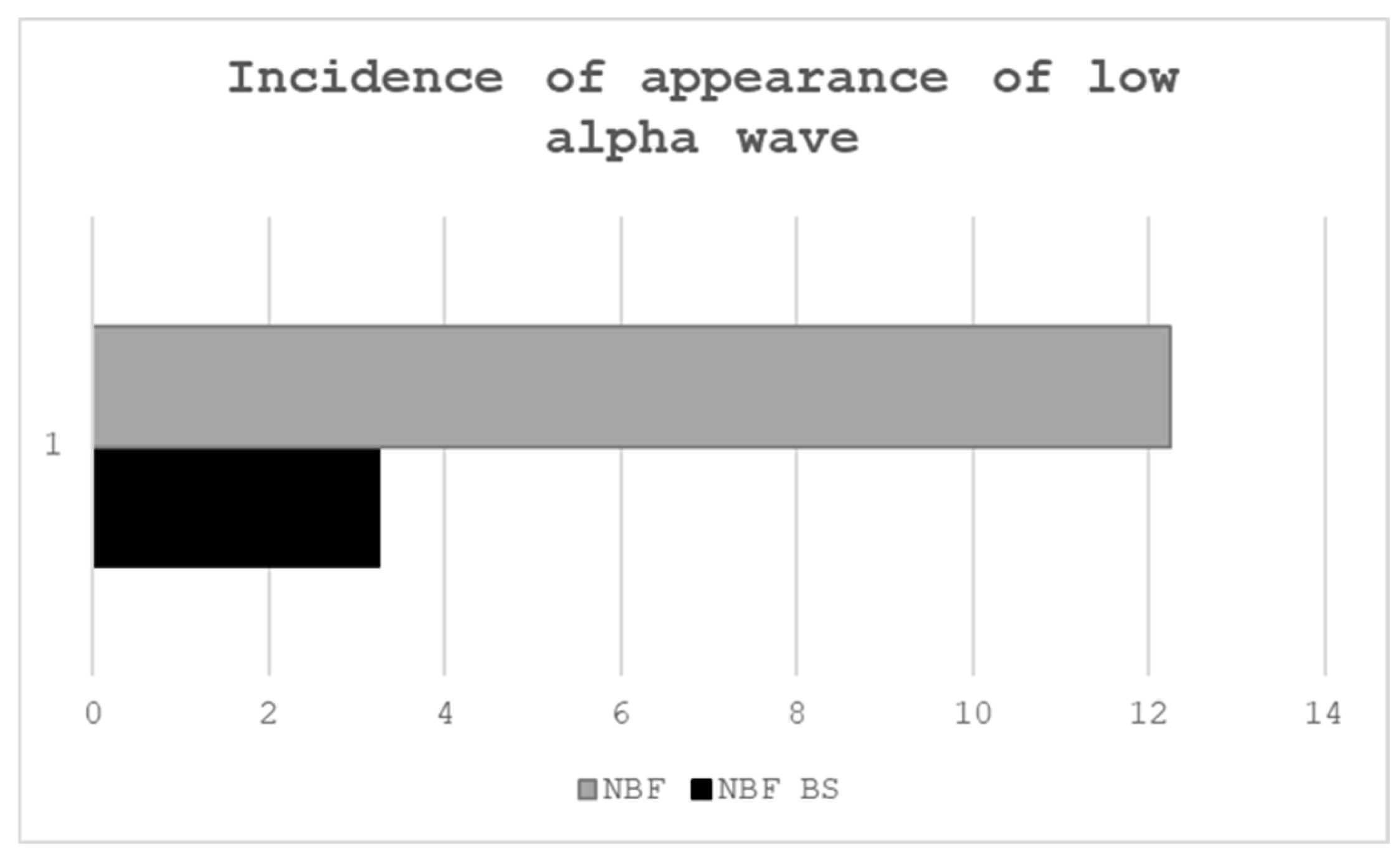

Data on the occurrence of low alpha waves are collected based on information provided by the selected device regarding their incidence. Alpha rhythms (8–13 Hz) in the EEG are subdivided into a “low alpha” band (approximately 8–10 Hz) and a “high alpha” band (10–12 Hz). Low alpha activity has been particularly linked to semantic memory processes and a state of relaxation. In a typical NeuroSky-based neurofeedback protocol, the software defines a target range for low alpha power. Empirical studies confirm that even inexpensive single-channel devices like NeuroSky’s can accelerate alpha enhancement.

The pilot project confirmed that, for the target population (people over 55 years of age), the use of this group of technological devices did not cause significant discomfort. In fact, the responses collected at the end of each phase of the test showed that all participants achieved high or very high levels of comfort and attention during the test. Regarding the performance of the proposed task, all participants were able to complete it without difficulty and reported no discomfort with either the NBF device or BS.

4. Discussion

Aging is often accompanied by natural changes in brain structure and function. Many older adults experience declines in memory, attention, and executive functions, which can impact daily living and overall quality of life. Additionally, the emotional landscape of aging can include increased vulnerability to conditions such as depression and anxiety. Traditional interventions, including pharmacological treatments and cognitive therapies, have shown varying degrees of success in addressing these issues [

30,

38]. Hence, exploring non-invasive alternatives that may complement existing treatment modalities becomes essential. Given the high prevalence, limited efficacy and safety concerns of current pharmacotherapies in older adults, it is both necessary and urgent to develop and implement novel, evidence-based strategies to curb the incidence and mitigate the burden of pain among the aging population.

Research suggests that NFB BS may improve cognitive functions that typically decline with age. By targeting specific brainwave patterns associated with attention and memory, NFB training can help older individuals enhance their cognitive performance. This BCI training could record EEG signals in real time and provide feedback on specific brain-wave patterns, making it possible to learn how to up or down-regulate targeted rhythms. On the other hand, BS arise when two tones of slightly different frequencies are played (one to each ear), and the brain perceives a third “beat” frequency equal to their difference. It is thought that training EEG oscillations (e.g., alpha, theta) could shift mental states toward enhanced focus or relaxation. [

22,

23,

29,

38,

39,

40].

Furthermore, NFB/BS may enhance neuroplasticity in the aging brain. While aging is typically associated with a decline in neuronal flexibility, the brain retains some degree of plasticity well into adulthood. NFB leverages this inherent capacity, facilitating the strengthening of neural circuits and compensating for age-related deficits. This adaptive mechanism may not only improve cognitive function but also help delay the progression of cognitive decline, which, among other things, is linked to pain [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Because alpha waves (8–12 Hz) are most prominent during relaxed wakefulness, its modifications have been carefully controlled. They are subdivided into low alpha (8–10 Hz), often linked to internalized attention and calmness, and high alpha (10–12 Hz), more associated with sensory gating and cognitive inhibition. Low alpha activity in pain states could be very relevant. For example, there is evidence that chronic pain patients frequently exhibit suppressed alpha power compared to healthy controls, suggesting that reduced alpha may serve as a biomarker for pain intensity. Specifically, lower resting-state alpha correlates with higher pain ratings across conditions such as fibromyalgia and neuropathic pain. Dynamic measures of alpha (such as the proportion of time spent in a high-alpha state versus transitions from low to high alpha) show stronger associations with pain resilience than mean alpha power alone. In one small study, increased fractional occupancy and transition probability into high-alpha states across NFB sessions correlated with reduced pain during cold-pressor tests [

41].

Emerging studies as the present project indicate that consistent NFB/BS training could contribute to a more regulated stress response. Moreover, by promoting a state of mental calmness and clarity, NFB/BS could foster greater emotional well-being. Beyond cognition, NFB holds promise for regulating distress and enhancing overall mental health outcomes in the older population. Emotional well-being is a critical component of healthy aging, significantly influencing overall life satisfaction [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Despite its promising potential, the application of NFB/BS in older adults is accompanied by significant challenges. The variability in individual brain function and the heterogeneity of aging populations necessitate the development of personalized training protocols [

2,

4,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

22].

Moreover, while preliminary research has shown encouraging results, larger-scale and long-term studies are required to establish standardized protocols and validate the efficacy of NFB/BS in this demographic. Future research should focus on optimizing NFB/BS protocols for older adults, including the duration and frequency of training sessions. Investigations into the underlying neural mechanisms that facilitate cognitive and emotional improvements will also be critical. Collaborative efforts among neuroscientists, clinicians, and geriatric specialists can pave the way for integrating NFB/BS into comprehensive geriatric care programs [

2,

3,

7,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

22].

Additionally, advancements in technology are likely to enhance the accessibility and effectiveness of NFB/BS training. Portable and user-friendly devices could make this intervention more widely available, allowing older individuals to benefit from NFB/BS in both clinical and home settings. Such innovations would be particularly beneficial in addressing the growing need for scalable and non-invasive interventions in an aging society.

Focusing on pain management, it is well known that several types of pain are prevalent among aging populations. NFB/BS targeting slow-wave activity (delta/theta modulation) and training could help to reduce pain perception [

7,

29].

5. Conclusions

NFB/BS represents an exciting frontier in the quest to enhance cognitive and emotional well-being among older adults. By leveraging the brain’s inherent capacity for neuroplasticity, NBF/BS offers a non-invasive and adaptable approach to mitigating the effects of aging on mental function. While further research is essential to refine its application and confirm long-term benefits, the current evidence suggests that NFB/BS may become an invaluable component of holistic geriatric care. Exploring and developing this technology, given its integration into health strategies for older adults, becomes crucial, as these strategies promise a future where aging is approached with resilience, clarity, and enhanced quality of life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.G. and M.E..; methodology, S.G. and M.J.; software, M.J., C.P. and A.M..; validation, S.G. and M.E.; formal analysis, S. G y M.J.; investigation, S.G. and ME.; resources, M.E., C.P. and A.M..; data curation, A.M. and C.P..; writing—original draft preparation, S.G.; writing—review and editing, M.E. and M.J..; visualization, S.G.; supervision, S.G.; project administration, M.E.; funding acquisition, M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de Sevilla (protocol code US PEIBA: 1553-N-22 and date of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request by email (marelen@us.es).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Departamento de Tecnología Electrónica, ETS Ingeniería and the Departamento de Fisiología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, 41012 Sevilla, Spain for their invaluable technical and administrative support throughout the course of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NFB |

Neurofeedback |

| BS |

Binaural Stimuli |

| TLA |

Electroencephalography |

References

- Park, J.-H. Is virtual reality-based cognitive training in parallel with functional near-infrared spectroscopy-derived neurofeedback beneficial to improve cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment? Disabil. Rehabilitation 2024, 47, 1717–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acevedo, B.P.; Dattatri, N.; Le, J.; Lappinga, C.; Collins, N.L. Cognitive Training with Neurofeedback Using fNIRS Improves Cognitive Function in Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatorre-Cruz, G.C.; Fernández, T.; Castro-Chavira, S.A.; González-López, M.; Sánchez-Moguel, S.M.; Silva-Pereyra, J. One-Year Follow-Up of Healthy Older Adults with Electroencephalographic Risk for Neurocognitive Disorder After Neurofeedback Training. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2021, 85, 1767–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda-Sánchez, F.; Cansino, S. The Effects of Neurofeedback on Aging-Associated Cognitive Decline: A Systematic Review. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2021, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Pilar, J.; Corralejo, R.; Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Álvarez, D.; Hornero, R. Assessment of neurofeedback training by means of motor imagery based-BCI for cognitive rehabilitation. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2014, 3630–3633. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.-R.; Hsieh, S. Neurofeedback training improves attention and working memory performance. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2013, 124, 2406–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.; Cheong, M.J.; Lee, H.; Cho, E.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, G.-W.; Kang, H.W. Effectiveness, Cost-Utility, and Safety of Neurofeedback Self-Regulating Training in Patients with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, T.; Heathcote, L.C; Hobson, H. Solmi M. Neuromodulatory Interventions for Pain Frontiers Front Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.; de la Vega, R.; Jensen, M.P.; Miró, J. Neurofeedback for Pain Management: A Systematic Review. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaieb, L.; Wilpert, E.C.; Reber, T.P.; Juergen Fell, J. Auditory Beat Stimulation and its Effects on Cognition and Mood States. Front Psychiatry 2015, 12, 6–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, P.-C.; Akpan, A.; Tang, K.-T.; Lakany, H. Brain computer interfaces for cognitive enhancement in older people - challenges and applications: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darijani, S.S.; .Sahebozamani, M.; Eslami, M.; Babakhanian, S.; Alimoradi, M.; Iranmanesh, M. The effect of neurofeedback and somatosensory exercises on balance and physical performance of older adults: a parallel single-blinded randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 24087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Pilar, J.; Corralejo, R.; Nicolas-Alonso, L.F.; Álvarez, D.; Hornero, R. Neurofeedback training with a motor imagery-based BCI: neurocognitive improvements and EEG changes in the elderly. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2016, 54, 1655–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Takahashi, D.; Kuroiwa, Y.; Sakurai, N.; Kodama, N. Construction and evaluation of a neurofeedback system using finger tapping and near-infrared spectroscopy. Front. Neuroimaging 2024, 3, 1361513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Jessee, W.; Hoyng, S.; Borhani, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Price, L.K.; High, W.; Suhl, J.; Cerel-Suhl, S. Sharpening Working Memory With Real-Time Electrophysiological Brain Signals: Which Neurofeedback Paradigms Work? Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 780817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, K.; Nami, M.; Sinaei, E.; Bagheri, Z.; Yoosefinejad, A.K. A Comparison between Effects of Neurofeedback and Balance Exercise on Balance of Healthy Older. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2021, 11, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.N.; Lee, T.S.; Sng, W.T.; Heo, M.Q.; Bautista, D.; Cheung, Y.B.; Zhang, H.H.; Wang, C.; Chin, Z.Y.; Feng, L.; et al. Effectiveness of a Personalized Brain-Computer Interface System for Cognitive Training in Healthy Elderly: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 2018, 66, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhinney, S.R.; Tremblay, A.; Boe, S.G.; Bardouille, T. The impact of goal-oriented task design on neurofeedback learning for brain–computer interface control. Med Biol. Eng. Comput. 2017, 56, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlats, F.; Djabelkhir-Jemmi, L.; Azabou, E.; Boubaya, M.; Pouwels, S. ; Rigaud, A,S. Comparison of effects between SMR/delta-ratio and beta1/theta-ratio neurofeedback training for older adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: a protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019, 20, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Staufenbiel, S.; Brouwer, A.-M.; Keizer, A.; van Wouwe, N. Effect of beta and gamma neurofeedback on memory and intelligence in the elderly. Biol. Psychol. 2014, 95, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakis, E.; Stathopoulou, S.; Frymiare, J.L.; Green, D.L.; Lubar, J.F.; Kounios, J. EEG Neurofeedback: A Brief Overview and an Example of Peak Alpha Frequency Training for Cognitive Enhancement in the Elderly. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2007, 21, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, H.-Y. (.; Vitiello, M.V.; Perlis, M.; Riegel, B. Open-Loop Neurofeedback Audiovisual Stimulation: A Pilot Study of Its Potential for Sleep Induction in Older Adults. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2015, 40, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-J.; Lee, N.-R. Using a mobile app comprising neurofeedback-based meditation and binaural beat music to treat PTSD symptoms: A qualitative analysis. Digit. Heal. 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingendoh, R.M.; Posny, E.S.; Heine, A. Binaural beats to entrain the brain? A systematic review of the effects of bianuralbeat stimulation on brain oscillatory activity, and the implications for psychological research and intervention. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0286023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschke, S.; le Roux, T.; Swanepoel, W. Outcomes of children with sensorineural hearing loss fitted with binaural hearing aids at a pediatric public hospital in South Africa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2022.152:110977.

- Valzolgher, C.; Verdelet, G.; Salemme, R.; Lombardi, L.; Gaveau, V.; Farné, A.; Pavani, F. Reaching to sounds in virtual reality: A multisensory-motor approach to promote adaptation to altered auditory cues. Neuropsychologia 2020, 149, 107665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phneah, S.W.; Nisar, H. EEG-based alpha neurofeedback training for mood enhancement. Australas. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2017, 40, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, F.; Azadinia, F.; Shaygan, M. Does brain entrainment using binaural auditory beats affect pain perception in acute and chronic pain?: a systematic review. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Krawutschke, M.; Kowalski, A.; Pasche, S.; Bialek, A.; Schweig, T.; Weismüller, B.; Tewes, M.; Schuler, M.; Hamacher, R.; et al. Cancer Patients’ Age-Related Benefits from Mobile Neurofeedback-Therapy in Quality of Life and Self-efficacy: A Clinical Waitlist Control Study. Appl. Psychophysiol. Biofeedback 2022, 48, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, P. Pain in Older Adults: Epidemiology, Impact and Barriers to Management. Rev Pain 2007, 1, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Mi, Y.; Li, M.; Nigri, A.; Grisoli, M.; Kendrick, K.M.; Becker, B.; Ferraro, S. Identifying brain targets for real-time fMRI neurofeedback in chronic pain: insights from functional neurosurgery. Psychoradiology 2024, 4, kkae026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Birbaumer, N. Real-time functional MRI neurofeedback: A tool for psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2014, 27, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, K.D.; Siegle, G.J.; Misaki, M.; Zotev, V.; Phillips, R.; Drevets, W.C.; Bodurka, J. Altered task-based and resting-state amygdala functional connectivity following real-time fMRI amygdala neurofeedback training in major depressive disorder. NeuroImage: Clin. 2018, 17, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grueschow,M. ; Stenz, N.; Thörn, H.; Ehlert, U.; Breckwoldt, J.; Brodmann Maeder, M.;, Exadaktylos, A.K.; Bingisser, R.; Ruff,C.C.; Kleim, B. Real-world stress resilience is associated with the responsivity of the locus coeruleus. Nat Commun. 2021, 12, 2275.

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Medica 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neurosky. Available online: https://store.neurosky.com/pages/mindwave (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Raspberry, Pi. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.com/ (accessed on 30 December 2025).

- Schofield, P.; Dunham, M.; Martin, D.; Bellamy, G.; Francis, S.-A.; Sookhoo, D.; Bonacaro, A.; Hamid, E.; Chandler, R.; Abdulla, A.; et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on the management of pain in older people – a summary report. Br. J. Pain 2020, 16, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaskovits, F.; Tyerman, J.; Luctkar-Flude, M. Effectiveness of neurofeedback therapy for anxiety and stress in adults living with a chronic illness: a systematic review protocol. JBI Évid. Synth. 2017, 15, 1765–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eijk, L.; A Zwijsen, S.; Keeser, D.; Oosterman, J.M.; Pogarell, O.; Engelbregt, H. EEG-neurofeedback training and quality of life of institutionalized elderly women (a pilot study). . 2017, 30, 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, K.; Henshaw, J.; Sutherland, H.; Taylor, J.R.; Casson, A.J.; Lopez-Diaz, K.; Brown, C.A.; Jones, A.K.P.; Sivan, M.; Trujillo-Barreto, N.J. Using EEG Alpha States to Understand Learning During Alpha Neurofeedback Training for Chronic Pain. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).