1. Introduction

Cryptography’s primary goal is to securely transmit data, protecting it from unauthorized access during transit. Before computers revolutionized the field, substitution ciphers were the go-to method for transmitting secure messages over insecure networks. These ciphers work by converting readable data (“plain-text”) into an encrypted form (“cipher-text”).

Substitution ciphers fall into two categories: Mono-alphabetic substitution ciphers, where each letter is replaced consistently, and poly-alphabetic substitution ciphers, which use multiple letter substitutions for greater complexity.

Mono-alphabetic substitution ciphers, where each plain-text letter is consistently replaced by a unique cipher-text letter, form the foundational structure of cryptography. In contrast, poly-alphabetic substitution ciphers increase complexity by substituting letters with different ones depending on their position, creating a dynamic and shifting code. While these ciphers appear simple, they present interesting computational challenges. They serve as key benchmarks for decryption algorithms, merging historical cryptographic methods with modern complexities, demonstrating how even basic designs can evolve into intricate encryption systems.

Traditional approaches to decrypt monoalphabetic substitution ciphers typically rely on frequency analysis and heuristic-based methods [

1]; however, with recent advancements in deep learning, Transformer-based models have introduced new possibilities for hastening and automating the decryption process.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of machine learning in cryptanalysis. For example, Blackledge and Mosola provide an overview of AI applications in cryptography, including machine learning for cryptanalysis [

2]. Nitaj and Rachidi discuss neural networks enhancing cryptographic security, potentially aiding decryption [

3], which also brings to mind the idea of using neural networks.

The T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) [

4] model, developed by Google Research and described in the

Appendix A.2 section, is a powerful natural language processing (NLP) tool based on the Transformer architecture. It treats all NLP tasks as a text-to-text problem, meaning both the input and output are always text, regardless of the task. For example, in translation, the input is text in one language, and the output is the translation in another language. In cryptanalysis, the input is the cipher-text and the output is the plain-text or the key used to encrypt the text.

T5 was pretrained on a large dataset called C4 (Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus) which is a large-scale text dataset created by filtering and cleaning web-crawled data to remove low-quality content [

5]. The model uses an encoder-decoder architecture, where the encoder processes the input and the decoder generates the output. T5 is flexible and scalable, making it suitable for a wide range of tasks, from simple text classification to complex text generation. [

4]

This study investigates the use of deep learning applications in solving monoalphabetic substitution ciphers in English. The T5 model, is adapted here to treat cipher decryption as a sequence-to-sequence problem. The model is fine-tuned to directly map ciphertext sequences to their corresponding plaintext or alphabet, enabling it to decode mono-alphabetic ciphers without the need for explicit rule-based or heuristic techniques.

To enhance the accuracy of decryption, an additional correction model, also trained using the T5 architecture, is applied to the output of the initial decryption. This correction model further refines the plain-text predictions by addressing residual errors in the sequence, significantly improving overall performance.

Lastly, to improve the accuracy, an algorithm was developed to improve the biased output of the correction model. This algorithm counted the number of substitutions for each letter and decided which letter was substituted with which letter.

During training, datasets consisting of mono-alphabetic encrypted text are provided, and the model learns to map cipher-text to plain-text and alphabet through minimizing a cross-entropy loss function. Hyperparameters such as the learning rate and batch size are optimized to improve decryption performance. The performance of each model is evaluated based on accuracy scores, loss values, and overall decryption success rate across a set of test samples.

The results, detailed in Benchmarks

Section 3.6, demonstrate the T5 model’s effectiveness in deciphering mono-alphabetic substitution ciphers, with accuracy reaching 73.56% on the English test set. With the inclusion of the correction model, accuracy increased to 82.81%. Adding the correction algorithm, the accuracy was further increased to 90.97%. Finally, with the addition of the second pass through the correction model, we reached a maximum accuracy of 91.96%

These findings suggest that the T5 model, when trained on mono-alphabetic ciphers, can achieve effective decryption performance, indicating its potential utility in cryptographic applications and NLP-related cryptanalysis research.

2. Related Works

Cryptanalysis, the study of methods to break cryptographic systems, has evolved significantly over the years. Early cryptanalysis techniques primarily focused on mathematical and statistical methods, such as frequency analysis for breaking simple ciphers like monoalphabetic substitution ciphers. While these methods remain foundational, recent advancements in machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced new opportunities and challenges in the field of cryptanalysis.

Previous work has been done to implement an algorithm that cryptanalyzed substitution cipher before. In fact, the idea of implementing an algorithm that automatically solved substitution cipher has been quite popular for some time. But their reliance on algorithmic methods limited their accuracy for shorter texts. Most notably, in an article published in 1995 by T. Jakobsen their algorithm only passes 90% accuracy after around 300 letters. [

14]

Utilizing machine learning and natural language processing, H. Sam has trained a model that is effective even for shorter texts. He passed 90% accuracy for sentences around the length of 100 characters. But since he published his study in 2007, new large language models have been trained and the n-gram model he used became out-dated. [

15]

2.1. Traditional Cryptanalysis Techniques

Traditional cryptanalytic methods have historically relied on mathematical algorithms and heuristics to decipher encrypted data. Among the most well-known methods are frequency analysis and brute-force attacks, which work well on simple encryption schemes like monoalphabetic substitution ciphers. However, as encryption techniques have evolved to be more complex, the need for more sophisticated approaches has become apparent. Despite their long-standing success, these traditional methods face limitations when applied to modern cryptographic algorithms, particularly those that are designed to resist known attack vectors.

2.2. Machine Learning Approaches in Cryptanalysis

In recent years, the integration of machine learning techniques in cryptanalysis has gained considerable attention. Supervised learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning methods have been proposed to tackle complex cryptographic algorithms. For instance, neural networks, particularly Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), have shown promise in analyzing and breaking certain types of encryption, including substitution ciphers and even more advanced algorithms. Deep learning models could be trained to reverse simple cipher encryptions, marking a significant step forward from traditional methods. These techniques have the advantage of being able to learn complex patterns in encrypted data without relying on predefined rules.

The article by Al-Janabi et al. [

6], provides a comprehensive review of the application of intelligent techniques such as machine learning and evolutionary algorithms in cryptanalysis. The review highlights the significant advancements made in the field, particularly in the context of breaking modern cryptographic algorithms. The authors emphasize that as AI technologies continue to evolve, they will have an increasingly prominent role in the analysis and decryption of cryptographic systems. Machine learning algorithms, particularly deep learning models like Transformers and neural networks, are seen as powerful tools in cryptanalysis, offering the potential to automate the process of breaking encryption schemes with greater efficiency than traditional methods.

However, the article also identifies several challenges in the implementation of AI-driven cryptanalysis. These include the need for large datasets, the complexity of training models on high-dimensional cryptographic systems, and the ethical implications of using AI for breaking encryption. The authors suggest that while AI presents vast opportunities, it also introduces new security concerns, as adversaries could use similar techniques to compromise encryption systems, thereby posing a potential threat to the security of sensitive data.

2.3. Machine Learning in Breaking Monoalphabetic Substitution Ciphers

In the context of monoalphabetic substitution ciphers, machine learning methods have been explored as a way to automate decryption. Friedman [

7] and Kasiski’s [

8] frequency analysis remains an important method, but more recent work has shifted towards leveraging AI techniques for improved performance. The use of deep learning models, such as T5 and BERT in breaking simple ciphers, has shown promising results. These models, trained on large corpora of language data, can identify patterns and make predictions about the likely mappings between ciphertext and plaintext letters.

Further, machine learning has been applied to solve substitution ciphers, with various approaches demonstrating notable success. Kambhatla et al. utilized neural language models combined with beam search, achieving results that outperformed traditional cryptanalysis methods [

9]. Hauer et al. took a different tack, integrating language models with Monte Carlo Tree Search to effectively decrypt substitution ciphers [

10]. Greydanus employed recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to address the complexities of the Enigma machine, showcasing the potential of neural networks in historical cipher decryption [

11]. Gohr advanced the field by enhancing attacks on the Speck cipher using deep learning techniques tailored to that specific cryptographic system [

12]. In contrast, our approach leverages the Transformer architecture, specifically the T5 model (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer), as an innovative alternative to these methods, providing a unified text-to-text framework for cryptanalysis that is both versatile and powerful.

Building on these advancements, our method adopts the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, which has proven highly effective at modeling complex sequence relationships—an essential aspect of solving substitution ciphers. Unlike recurrent models, Transformers handle long sequences more efficiently, avoiding the limitations of sequential processing. By utilizing the T5 model’s text-to-text formulation and its extensive pretraining on the C4 corpus, our approach excels at recognizing and reconstructing patterns within ciphertext. This allows for accurate plaintext recovery while offering a more scalable and streamlined solution compared to prior methods like beam search or Monte Carlo Tree Search.

3. Methodology

In this section, we detail the comprehensive methodology developed and employed for the cryptanalysis of monoalphabetic substitution ciphers using a sequence-to-sequence deep learning approach. First, we present the hyperparameters used to fine-tune the T5-base model and describe the dataset preparation process. Then, we examine two different output strategies: plain text and alphabet sequence, and compare their effectiveness. We further introduce a correction model designed to enhance the output accuracy, followed by a post-processing correction algorithm to resolve remaining inconsistencies. Finally, we explain the benchmarking process using the Levenshtein distance metric and provide quantitative results that highlight the progressive improvements achieved through each stage of the pipeline.

3.1. Hyperparameters

The training processes of models were conducted on an NVIDIA P100 GPU and took approximately 9.5 hours to complete. The hyperparameters used for fine-tuning are listed in

Table 1.

3.2. Plain Text As Output

For preparing the dataset, the models were trained using the first 383,600 rows for the text model, 575,500 rows for the alphabet model, and 487,500 for the correction models from the

“agentlans/high-quality-english-sentences” [

16] dataset available on Hugging Face [

17], which consists of 1.53 million rows in total. The dataset was preprocessed to suit the requirements of the task by randomly encrypting the sentences using monoalphabetic substitution ciphers. Each sentence was transformed into ciphertext by mapping each letter of the plaintext to a unique letter in the alphabet according to a randomly generated substitution key. This ensured that the encryption was both systematic and unpredictable for every sentence. The resulting ciphertext served as the input to the model, while the corresponding plaintext and sequence of alphabet acted as the output, creating a sequence-to-sequence dataset specifically tailored for training the cryptanalysis model. The model was trained for plain text as output. Here are examples from encoded text data:

Here encoded text passes through the model and the model outputs the answer itself. But this technique comes with a problem. The T5 model tries to make outputs meaningful so even though the models cannot predict the exact word, it assumes that output has to be a meaningful regular sentence.

For instance:

Encoded Text (Input): Vqvsbfcv cl jwtclbtt clqiwsbt jwtclbtt rovclclz vr rxb jwtclbtt qborcycqvrb ibdbi.

Plain Text (Desired Output): Academia in business includes business training at the business certificate level.

Decoded Text (Actual Output): Acupunct in syringes includes syringes tying to the syringes reeditive layer.

Alongside not being properly deciphered, the output of this model proved to be exclusively problematic as the output was indistinguishable from a correct sentence. This proved to be harder to improve the model (for instance, with a second corrector model) as the output seemed to be correct without really being.

3.3. Alphabet Sequence As Output

In this concept of data, encoded text is passed through the model and it outputs its alphabet sequence. For instance:

Encoded text (Input): Hd adcdcwda yod drdqyn zk zsa boiluozzu.

Alphabet (Output): rcme...wi.fl.sh.nvu.d.b.to

Plain text: We remember the events of our childhood.

For example here, in the alphabet, ‘r’ is the first letter of the sequence which is matched with ‘a’. Because of that the letter ‘a’ is changed with all the ‘r’ letters in the encoded text. Since some letters are not used it is not possible to know what they got substituted for. The ‘.’ refers to the letter being unknown. Bringing this perspective to the model, it doesn’t have to make a meaningful regular sentence. After that with the alphabet model, plain text can be solved simply by mapping the letters.

For instance:

Encoded Text (Input): Kxxt gc ogcz dvjd dvx sicbxrpxcsxb lip gotibx jfx di zfju jddxcdgic di dvx mxbbic lip jfx dflgcy di dxjsv dvxo, cid di tpcgbv dvxo.

Alphabet (Output): .rnt.ui.oawfb.dl.pcsyh.e

Decoded Text (Processed Output): Wees in dinz that the conreplencer fol idsore aue to zuay attention to the berron fol aue tufiny to teach thed, not to slnirh thed.

Plain Text (Desired Processed Output): Keep in mind that the consequences you impose are to draw attention to the lesson you are trying to teach them, not to punish them.

Thanks to that, this solution increases the accuracy of the first model while still leaving room for improvement.

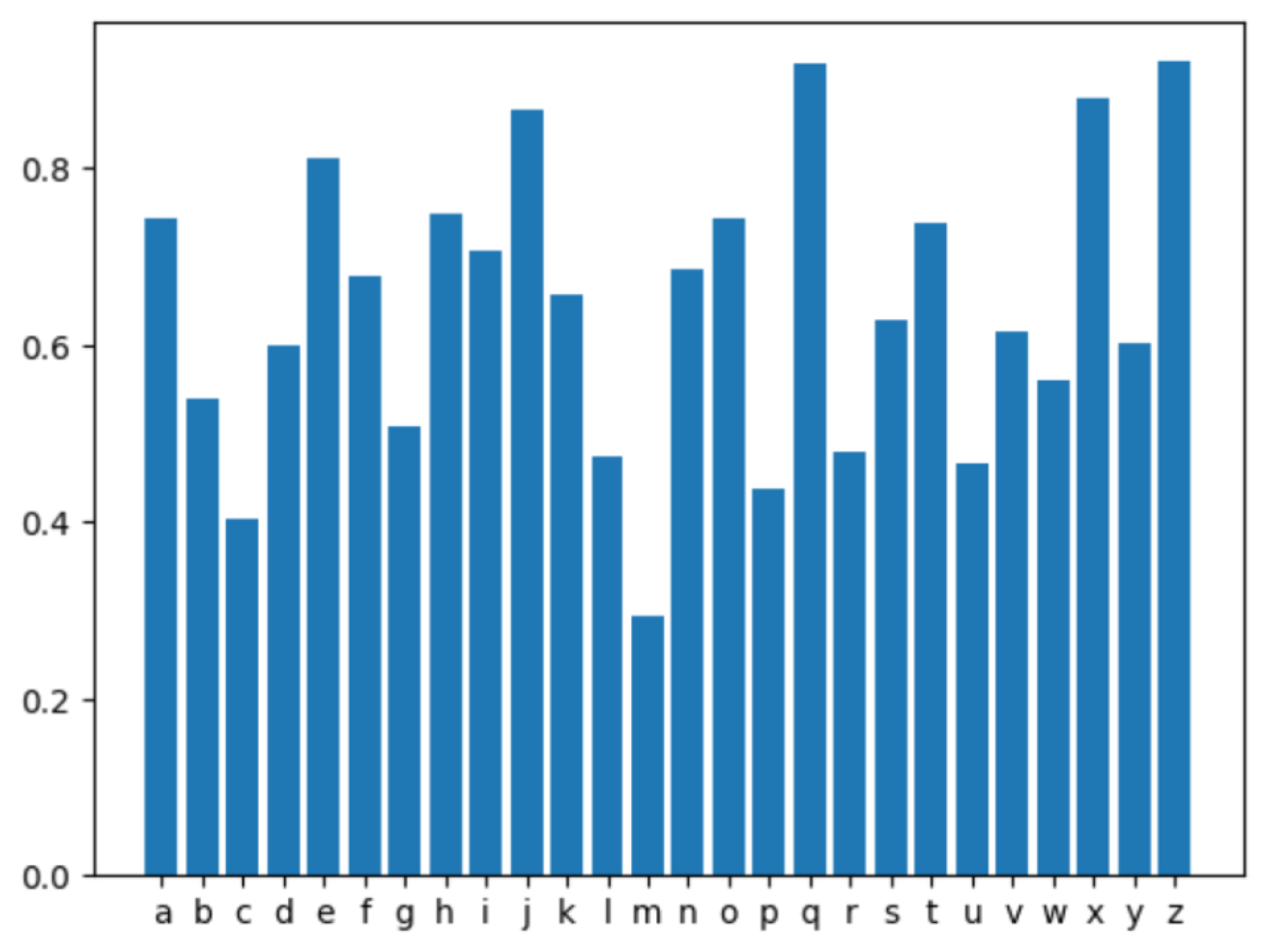

Figure 1.

The accuracy of the alphabet sequence as output model based on characters.

Figure 1.

The accuracy of the alphabet sequence as output model based on characters.

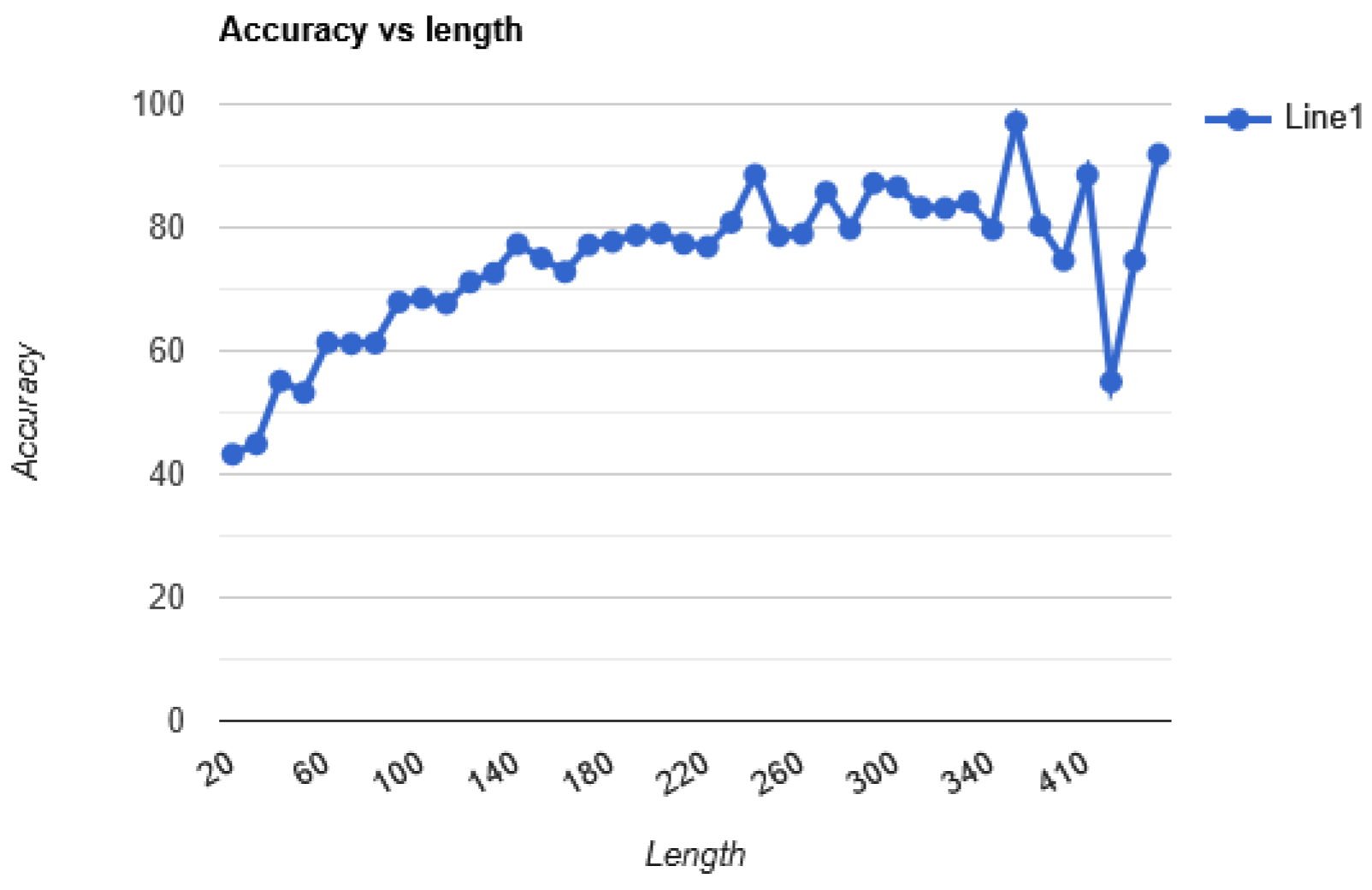

Figure 2.

The average accuracy of the alphabet sequence as output model based on length.

Figure 2.

The average accuracy of the alphabet sequence as output model based on length.

3.4. The Correction Model

After increasing the accuracy of the model with the Alphabet sequence as output model and minimizing the assumption error, the model becomes available for improvement. This improvement comes in the form of a second model. Passing the output of the first model through the second model, the second model corrects the grammatical and logical errors, leading to a more correct sentence. This wasn’t available with the Plaintext as output model since the output was already correct grammatically and logically.

The dataset was obtained by ciphering the plaintext using a partially scrambled alphabet. The alphabet was scrambled with the goal of mimicking the output of the alphabet sequence as output model. In order to get the closest results, a small portion of the data was passed through the alphabet sequence as output model. Then the output was examined and an algorithm was written to mimic the output.

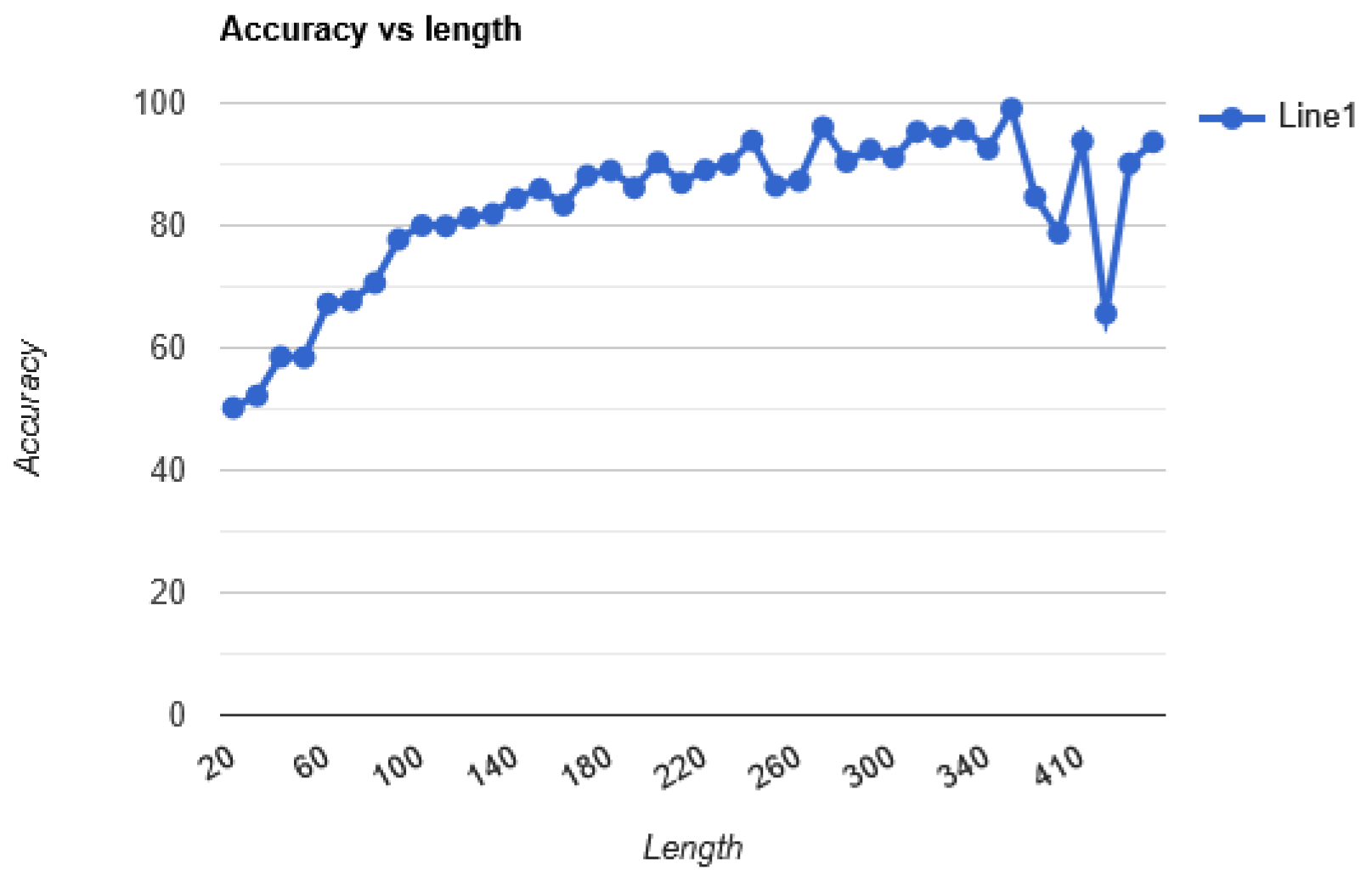

Figure 3.

The average accuracy of the solver based on length after the Correction model is added.

Figure 3.

The average accuracy of the solver based on length after the Correction model is added.

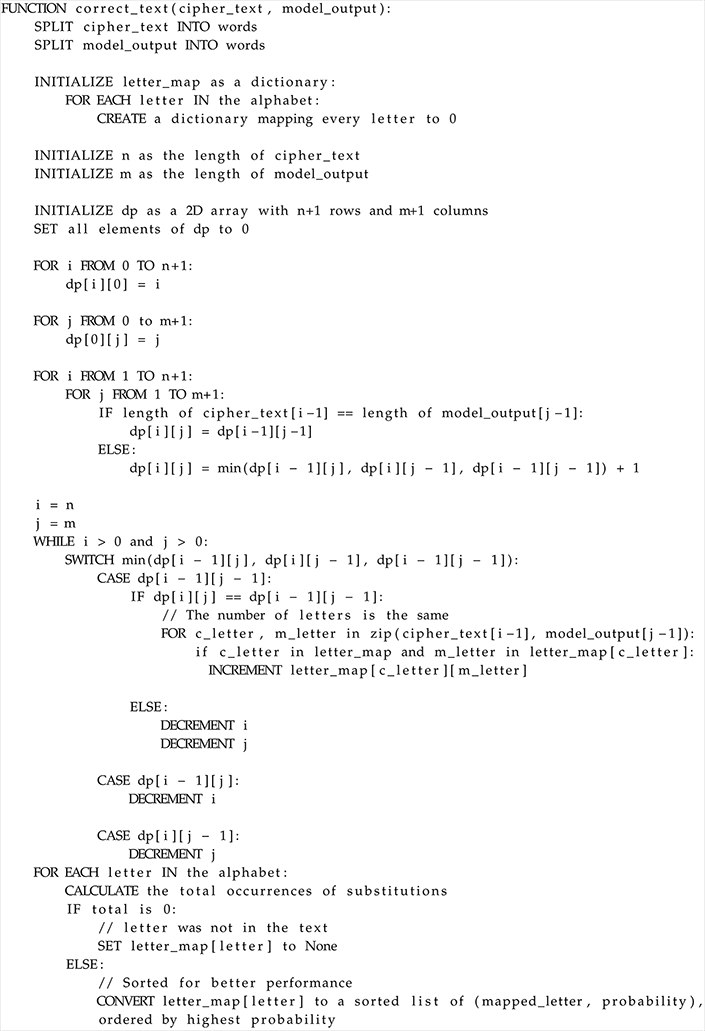

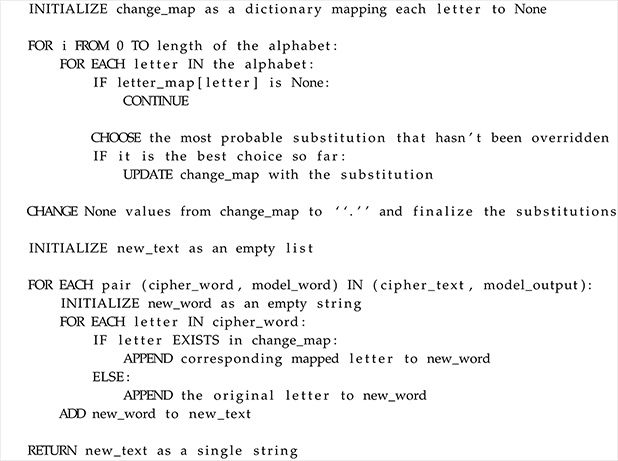

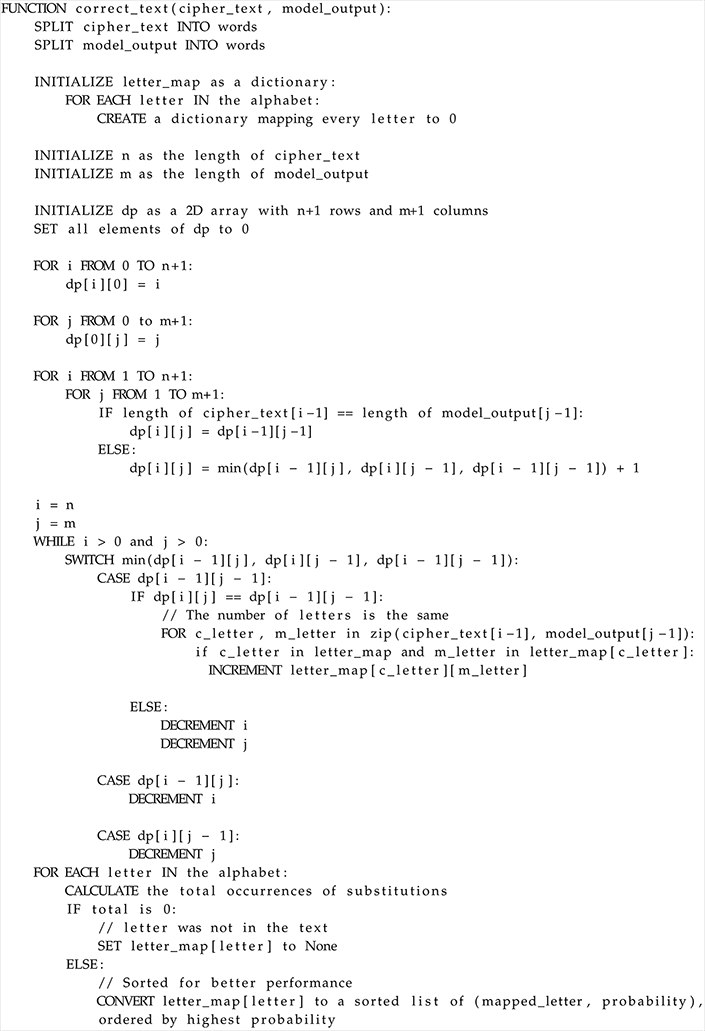

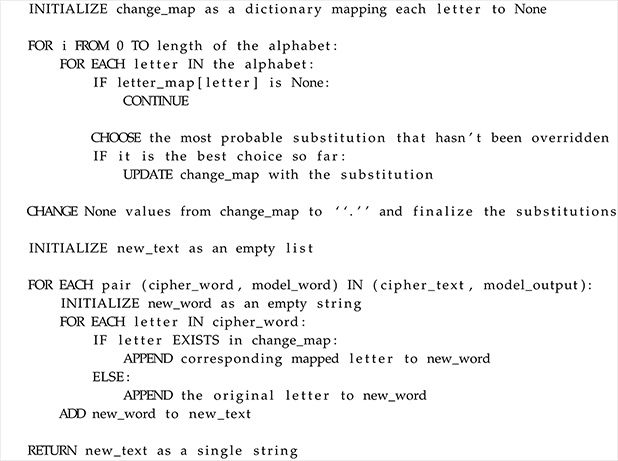

3.5. The Correction Algorithm

The correction model presented a problem: It changed the lengths of the words and the substitution was not consistent. The same letter was not always substituted for the same letter. That, of course, meant that the output was still not correct and could be improved upon. The best way to do that was to implement an algorithm that attempted to correct the mistakes made by the correction model. An algorithm was best suited for this task as, unlike LLMs, an algorithm has consistent results. This algorithm had to take the cipher-text and the output of the correction model as input and return a corrected version based on the letter configuration of the cipher-text.

To do this, the algorithm counts how many times a specific letter was substituted for another. Then, replaces that letter in the cipher-text with the letter it got substituted for the most. First, the algorithm breaks the cipher-text and the model output into words, then if the number of words are different between the texts, uses a Levenshtein edit-distances like algorithm to calculate which word corresponds to which. Also, if the length of the words is different, then those words are not taken into consideration when counting letters as different lengths mean the word was most certainly different from original. Taking it into consideration will contaminate the final key, reducing accuracy. A detailed psuedo-code of the algorithm can be found in the

Appendix A.3 section.

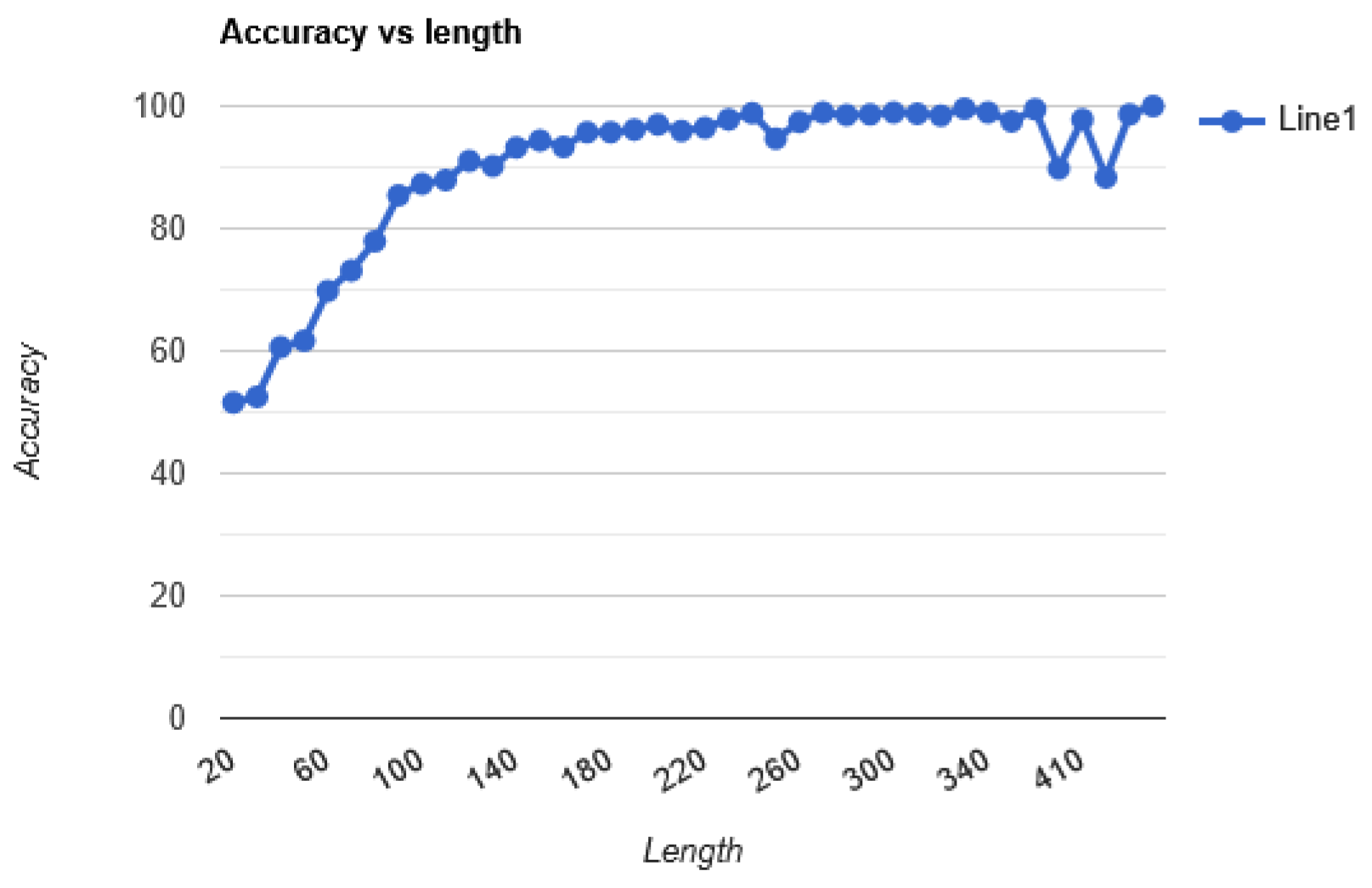

Figure 4.

The average accuracy of the solver based on length after the Correction algorithm is implemented.

Figure 4.

The average accuracy of the solver based on length after the Correction algorithm is implemented.

3.6. Benchmarks

The Levenshtein distance, also known as edit distance, is a metric that quantifies the difference between two strings by calculating the minimum number of single-character operations—insertions, deletions, or substitutions—required to transform one string into the other. This metric is particularly useful in natural language processing and computational linguistics because it provides a straightforward numerical representation of how similar or dissimilar two sequences are. For example, the transformation of the word “kitten” to “sitting” requires three operations: replacing ’k’ with ’s’, replacing ’e’ with ’i’, and appending ’g’ at the end. [

13]

In this project, Levenshtein distance was employed as a benchmark to evaluate the performance of the decryption and correction models. By comparing the output generated by the models with the corresponding ground truth plaintext, the error margin in terms of character differences was objectively measured. This benchmarking approach allowed valuable insights to be gained into the model’s ability to accurately decrypt and correct monoalphabetic substitution ciphers, and improvements were quantified and fine-tuned based on a consistent, well-understood metric.

The similarity percentage

S between two strings

and

is expressed as:

Where:

is the Levenshtein distance between and ,

and are the lengths of the strings and , respectively.

The overall evaluation metric

E is calculated by comparing the final output of the model with the corresponding ground truth. It is based on the cumulative Levenshtein distance between the model’s final output and the ground truth across all test samples:

Where:

is the Levenshtein distance between the model’s final output and the ground truth for the i-th sample,

n is the total number of test samples,

is the length of the ground truth string .

This formula provides a final score that quantifies the overall accuracy of the decryption and correction models, where a higher score indicates better performance.

The benchmark was performed on 1000 encrypted data points, and the average results can be seen in Table 2. The first 1000 test data from the aglentans dataset which was used for the benchmark. But instead of using the “train” dataset which was used when training the model, the “test” dataset was used when conducting the benchmarks. So the model hasn’t seen the benchmark dataset before. The average length of the cipher-texts used was 136.64 characters. The data was encrypted randomly using Python’s random library.

4. Discussion

Linguistic methods such as frequency analysis has been a very important aspect of cryptanalysis in the past. Now, with the implementation of stronger ciphers this millennia old method was deemed useless. Only in puzzles and brain teaser was it able to survive. Although we are not the first to break a substitution cipher this study shows that large language models are really effective at solving basic ciphers.

Using bigger datasets and experimenting with different versions or models, higher accuracies could be reached. Also by improving the algorithms used, a solver with near perfect accuracy could be reached even for relatively small texts.

Using similar methods, a model that solves poly-alphabetical substitution ciphers could also be developed. Expanding the idea out of the traditional substitution ciphers, a model that solves permutation ciphers is also a possibility to consider.

Although not feasible in the near feature, with immense computational power and huge datasets, a model can take on the challenge of breaking modern ciphers such as AES or DES. Such task is essentially challenging since modern ciphers are designed to have minimal corelation between the plain-text and the cipher-text.

5. Conclusions

We proved that AI and transformer architectures could be used to crypt-analyze cipher-text for basic ciphers. The high accuracy we got imply that this method is very useful when trying to crack an english substitution cipher. This study also shows how proficient transformers are in NLP, easily beating one of the most challenging linguistic problems. This allows less capable individuals to take a shot at cracking ciphers as well as helping skilled individuals.

All models developed in this study have been open-sourced under the Apache-2.0 License. These resources ensure full reproducibility of our results and support further research in AI-driven cryptanalysis. The following assets are publicly available:

Codebase: The complete implementation, training scripts, and benchmarking tools are available on the

GitHub repository.

Appendix A Appendix

Appendix A.1. Generation Examples

Table A1.

15 Generation Examples

Table A1.

15 Generation Examples

| Encrypted Text |

Similarity |

Decoded Text |

Plain Text |

| Rbdnpqb gabu nwb wbijsnrlb gabu nwb ipda bnqkbw gj dlbny nyx dnwb tjw. |

92.96% |

Because they are disposable they are much easier to clean and care for. |

Because they are removable they are much easier to clean and care for. |

| Jbbqlnase uq JMJ fujuafuabf as 2009, mwjlu nafwjfw ijf umw strywl qsw bjtfw qk nwjum as yqum Qmaq jsn Iwfu Oaleasaj, jsn fulqdw ijf kqtlum as bjtfwf qk nwjum. |

96.84% |

According to ADA statistics in 2009, heart disease was the number one cause of death in both Ohio and West Virginia, and study was fourth in causes of death. |

According to AHA statistics in 2009, heart disease was the number one cause of death in both Ohio and West Virginia, and stroke was fourth in causes of death. |

| Oqnlgs zeyln kzqolyk, zey kzqoygzk pluu jnbfzlfy lgkznqfzlgs kjvnzk bgo ydynflky, pvnmlgs bk ilzgykk bgo gqznlzlvg fvbfeyk bgo zeya pluu bukv ltjuytygz cbnlvqk jnvxyfzk bgo ycygzk. |

94.53% |

During their studies, the students will practice incorporating sports and exercise, working as business and nutrition coaches and they will also implement various projects and events. |

During their studies, the students will practice instructing sports and exercise, working as fitness and nutrition coaches and they will also implement various projects and events. |

| Dgg: Vahkbar tad ckdhnegbd lprr zg dggpvt optogb zprrd Pv dyphg nm hogdg pvcbgadgd, vahkbar tad cnvhpvkgd hn zg a tbgah gvgbtf zkf. |

100.00% |

See: Natural gas customers will be seeing higher bills in spite of these increases, natural gas continues to be a great energy buy. |

See: Natural gas customers will be seeing higher bills in spite of these increases, natural gas continues to be a great energy buy. |

| Jdhf-ydtkf dhf sdckg-ydtkf kexcxvgmtu xnnxgcvhmcmkt dyxvhf xh Hks Wkdjdhf’t tvycgxnmedj hxgcbkgh nkhmhtvjd. |

93.46% |

The Classics and Ancient History department does not have wide provisions for independent research at an undergraduate level apart from the final year dissertation. |

The Classics and Ancient History department does not have many provisions for independent research at an undergraduate level apart from the final year dissertation. |

| Fwa qia tn ctfw ktvklofktv ovu dwtftabapfgtvkp istja obogsi ykbb dgtzkua o wtsa ykfw sohksqs dgtfapfktv ovu ov osdba yogvkvx kv fwa azavf tn o nkga. |

93.24% |

The use of both ignition and photoelectric smoke alarms will provide a home with savings protection and an ample warning in the event of a fire. |

The use of both ionization and photoelectronic smoke alarms will provide a home with maximum protection and an ample warning in the event of a fire. |

| Vt vo tuxpxzgpx npxzxplhax tg lpplrqx xaxktpgwxo vr tux xaxktpgaetvk kxaa og tult tux dltxp tg hx tpxltxw vr tux xaxktpgaetvk kxaa mle rgt ougptkjt dvtugjt tgjkuvrq tux xaxktpgwx. |

92.18% |

It is therefore preferable to change electrodes in the electrolytic cell so that the waves to be treated in the electrolytic cell may not direct without causing the electrode. |

It is therefore preferable to arrange electrodes in the electrolytic cell so that the water to be treated in the electrolytic cell may not shortcut without touching the electrode. |

| Ryxzybdk zah jivguk ymzy hbwgabr Nbp zuubrrgpgvgyk jqxbvk pk ymb uiawixezaub iw hgdgyzv xbriqxubr ngym ybumaguzv dqghbvgabr uza vbzh yi z hzadbx ymzy ’diih baiqdm’ rivqygiar ezk wzgv yi pb hbjvikbh; ymbk zvri wzgv yi uiarghbx z nghbx ebzrqxb iw qrbx bojbxgbaub ga zuubrrgpgvgyk ebzrqxbebay. |

92.76% |

Strategy and policy that defines Web accessibility policy by the combination of digital resources with technical guidelines can lead to a danger that ’cood entry’ solutions may fail to be developed; they also fail to consider a wider measure of user experience in accessibility measurement. |

Strategy and policy that defines Web accessibility purely by the conformance of digital resources with technical guidelines can lead to a danger that ’good enough’ solutions may fail to be deployed; they also fail to consider a wider measure of user experience in accessibility measurement. |

| Z aryudo tk yuxg pwktavzoptw-ogrtaropx jdzxl gtdry fpdd jr ogzo tua yusraxtvsuoray fpdd jr zjdr ot kpwq xarzophr ytduoptwy ot satjdrvy, fgpxg fr qt wto rhrw uwqrayozwq — satjdrvy kzxrq jm ogr vpdpozam, ktuwq pw grzdogxzar, zwq hpaouzddm zdd togra zarzy tk guvzw rwqrzhta. |

95.26% |

A result of such information-theoretic black holes will be that our microcosmologists will be able to find creative solutions to problems, which we do not even understand — problems faced by the military, found in healthcare, and virtually all other areas of human endeavor. |

A result of such information-theoretic black holes will be that our supercomputers will be able to find creative solutions to problems, which we do not even understand — problems faced by the military, found in healthcare, and virtually all other areas of human endeavor. |

| Oran xfzmaxfbfio rfljn os finmxf fker ekigagkof eki jfxysxb orf xawsxsmn gmoafn kig splawkoasin orko jslaef syyaefxn kxf ekllfg mjsi os jfxysxb. |

93.75% |

This requirement helps to ensure each candidate can perform the various duties and operations that police officers are called upon to perform. |

This requirement helps to ensure each candidate can perform the rigorous duties and obligations that police officers are called upon to perform. |

| Qmg ghhpzq mle nqe zppqe nf FNV’e Unenpf 2020 Nfnqnlqnug, tmnam iolage lf gyimlene pf gfmlfanfb qgamfpopbx-zgolqgd nfeqzvaqnpf lfd nfugeqygfq nf qmlq qgamfpopbx. |

99.38% |

The effort has its roots in NIV’s Vision 2020 Initiative, which places an emphasis on enhancing technology-related instruction and investment in that technology. |

The effort has its roots in NIU’s Vision 2020 Initiative, which places an emphasis on enhancing technology-related instruction and investment in that technology. |

| Shfbmj sq f $25,000 icfbs lcqk shw Lcwg E. Wkwcjqb Lqdbgfsyqb, shw jzhqqe nyee zqkrwbjfsw zqkkdbyso rfcsbwcj lybfbzyfeeo. |

84.00% |

Thanks to a $25,000 grant from the Fred L. Eisenhower Foundation, the school will investigate community problems financially. |

Thanks to a $25,000 grant from the Fred L. Emerson Foundation, the school will compensate community partners financially. |

| Gplwjpi jac ztcd vcdd urvyficeetic (8) rlm gryc etic jarj utuudce ric vpgwln ptj, pi jarj jac aomipncl we yccfwln r urvyficeetic pl jac krjci. |

82.39% |

Monitor the fuel cell temperature (8) and make sure that molecules are coming out, or that the hydrogen is leaving a temperature on the water. |

Monitor the fuel cell backpressure (8) and make sure that bubbles are coming out, or that the hydrogen is keeping a backpressure on the water. |

| Fre qxtmvf tencq: tmqmsu vgaet xgzzdceq fg vteyesf vtgvet ekxrnsue tnfe ncpdqfhesf; msfetsnz vtmxe nsc nqqef cmqzgxnfmgsq qggset gt znfet zenc fg bmsnsxmnz ekxeqq nsc qfteqq; nsc bmsnzzl, ekxrnsue tnfe teynzdnfmgs gt bnqfet nvvtexmnfmgs gxxdtq. |

84.02% |

The script reads: using cover rolls to prevent cover exchange rate adjustment; internal crime and asset dispositions taken on later lead to financial stress and stress; and finally, exchange rate regulation on faster acceleration runs. |

The script reads: rising power colludes to prevent proper exchange rate adjustment; internal price and asset dislocations sooner or later lead to financial excess and stress; and finally, exchange rate revaluation or faster appreciation occurs. |

| Gsq bgomqigb bgzh wi gzby uqazobq nq azi awigxwd gsq zttb gsqh zxq obcir. |

87.67% |

The students stand on task because we can control the hours they are in. |

The students stay on task because we can control the apps they are using. |

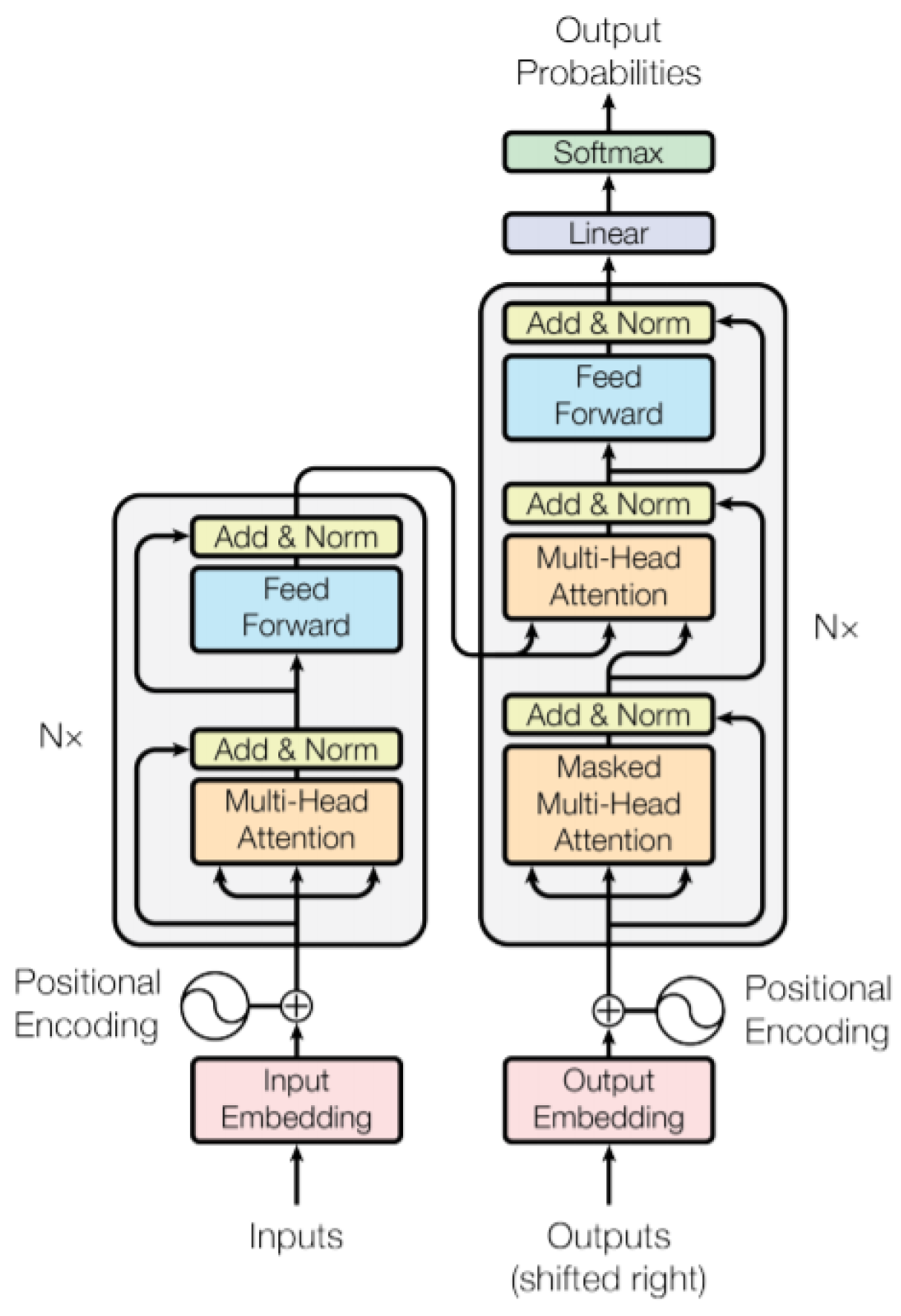

Appendix A.2. Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer (T5) Model

The T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) Base model is a Transformer-based architecture that employs an encoder-decoder framework for handling natural language processing tasks. We focused on the T5-Base variant in this study. T5 uses a text-to-text approach, treating every task as a sequence-to-sequence problem. This means the input and output are always text, regardless of the task. For example, in our cryptanalysis application, the input is the ciphertext, and the output is either the plaintext or the encryption key. Also, in our autocorrection application input is a text with typos and output is corrected text. T5-Base consists of two main components: an encoder and a decoder. The encoder processes the input sequence, and the decoder generates the output sequence. Both components are built using Transformer layers. The encoder in T5-Base is a stack of 12 Transformer layers. Each layer consists of two main sub-components: self-attention and feed-forward network (FFN). [

4]

Appendix A.2.1. Embedding Layer

Self-attention is a core part of Transformer models, enabling them to process sequences by considering all tokens in relation to each other. Unlike RNNs and LSTMs, which struggle with long-range dependencies, self-attention captures dependencies regardless of token position. Each token generates Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) vectors. Attention scores are calculated by the dot product of Q and K, then normalized with softmax. The token’s representation is updated using a weighted sum of the value vectors, allowing the model to focus on relevant information across the sequence.

Appendix A.2.2. Self-Attention Mechanism

Self-attention is a core part of Transformer models, enabling them to process sequences by considering all tokens in relation to each other. Unlike RNNs and LSTMs, which struggle with long-range dependencies, self-attention captures dependencies regardless of token position. Each token generates Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) vectors. Attention scores are calculated by the dot product of Q and K, then normalized with softmax. The token’s representation is updated using a weighted sum of the value vectors, allowing the model to focus on relevant information across the sequence.

Appendix A.2.3. Query, Key, and Value Vectors

The input sequence of tokens is first transformed into three different representations — Query, Key, and Value. These are linear projections of the input embeddings using learned weight matrices

,

, and

:

Where:

Q is the matrix of query vectors for each token.

K is the matrix of key vectors for each token.

V is the matrix of value vectors for each token.

Appendix A.2.4. Attention Scores

To determine each token’s importance to another, we compute attention scores as the dot product of a token’s query vector with the key vectors of all others. The score between tokens i and j is:

Where:

is the query vector for token i,

is the key vector for token j,

is the dimensionality of the key vectors, used for scaling.

Higher scores mean stronger attention.

Appendix A.2.5. Softmax Normalization

To normalize attention scores into probabilities, we apply the softmax function row-wise, making the attention weights interpretable and usable for weighting value vectors.

Appendix A.2.6. Weighted Sum of Values

The final step is computing a weighted sum of value vectors, where each token’s output is influenced by all others based on attention scores:

This enables each token to gather context-aware information from the entire sequence.

Appendix A.2.7. Multi-Head Attention

Instead of a single attention mechanism, Transformers use multi-head attention, applying attention multiple times in parallel with different weights. The outputs are concatenated and linearly transformed, allowing the model to capture diverse token relationships and dependencies.

The multi-head attention process is:

Where:

h is the number of attention heads,

Each head computes its own self-attention,

is a final linear transformation that projects the concatenated heads into the output space.

Self-attention enables Transformers to model complex token relationships by computing attention scores and weighted value sums. Multi-head attention enhances this by capturing diverse dependencies, making it essential for models like T5 in tasks like cryptanalysis. [

18]

Appendix A.2.8. Feed-Forward Network (FFN)

The Feed-Forward Network (FFN) in Transformers follows self-attention, independently transforming each token to enhance its representation. The FFN consists of two fully connected (dense) layers with a nonlinear activation function in between. Its operation can be represented mathematically as follows:

Where:

x: Input token representation (dimension ).

: Learnable weight matrices.

has dimensions .

has dimensions .

: Bias terms for the respective layers.

: Model dimension.

: Dimension of the intermediate layer, typically in Transformer-based models.

Activation: A nonlinear activation function such as ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) or GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit).

In T5, the FFN follows the standard Transformer structure, refining token representations in two stages: self-attention (or cross-attention in the decoder) and FFN. The input is normalized with LayerNorm, processed through the FFN, and then added back to the input via a residual connection, improving gradient flow and stabilizing training [

19].

Appendix A.2.9. T5 Model Architecture

The T5 model consists of an architecture mentioned above. Below is the visual representation of its architecture and layers.

Figure A1.

T5 Model Architecture

Figure A1.

T5 Model Architecture

In

Figure A1, the architecture of the model can be seen [

18]. The model also adds positional encodings to inputs to provide the necessary information about the sequence order, enabling the model to understand the relative or absolute position of each token [

20].

Appendix A.3. Correction Algorithm

References

- A. Eskicioglu and L. Litwin, "Cryptography,” IEEE Potentials, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 36-38, Feb.-Mar. 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. Blackledge and N. Mosola, ”Applications of artificial intelligence to cryptography,” Trans. Mach. Learn. Artif. Intell., vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 1–47, Jun. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://journals.scholarpublishing.org/index.php/TMLAI/article/view/8219.

- A. Nitaj and T. Rachidi, “Applications of neural network-based AI in cryptography,” Cryptography, vol. 7, no. 3, p. 39, Aug. 2023. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- C. Raffel, N. Shazeer, A. Roberts, K. Lee, S. Narang, M. Matena, Y. Zhou, W. Li, and P. J. Liu, “Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer,” Journal of Machine Learning Research, vol. 21, no. 140, pp. 1–67, 2020. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1910.10683.

- J. Dodge et al., “Documenting Large Webtext Corpora: A Case Study on the Colossal Clean Crawled Corpus,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08758, Sept. 30, 2021. [Online]. Available: arxiv.org/abs/2104.08758.

- S. T. Al-Janabi, B. Al-Khateeb, and A. J. Abd, “Intelligent Techniques in Cryptanalysis: Review and Future Directions,” UHD Journal of Science and Technology, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 1–10, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. F. Friedman, The Index of Coincidence and Its Applications in Cryptanalysis, Laguna Hills, CA: Aegean Park Press, 1987. [Online]. Available: https://www.cryptomuseum.com/people/friedman/files/TIOC_Aegean_1987.

- A. L. Hananto, A. Solehudin, A. S. Y. Irawan, and B. Priyatna, “Analyzing the Kasiski Method Against Vigenere Cipher,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.04519, Dec. 2019. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.04519.

- N. Kambhatla, A. M. Bigvand, and A. Sarkar, “Decipherment of substitution ciphers with neural language models,” in Proc. 2018 Conf. Empirical Methods Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, Oct. 2018, pp. 869–874. [Online]. Available: https://aclanthology.org/D18-1102.

- B. Hauer, R. Hayward, and G. Kondrak, “Solving substitution ciphers with combined language models,” in Proc. 25th Int. Conf. Computational Linguistics: Technical Papers (COLING), Dublin, Ireland, Aug. 2014, pp. 2314–2325. [Online]. Available: https://aclanthology.org/C14-1218.

- S. Greydanus, “Learning the enigma with recurrent neural networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.07576, Aug. 2017. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.07576.

- A. Gohr, “Improving attacks on round-reduced Speck32/64 using deep learning,” in Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2019, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, Aug. 2019, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 11693, pp. [CrossRef]

- R. Haldar and D. Mukhopadhyay, “Levenshtein Distance Technique in Dictionary Lookup Methods: An Improved Approach,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1101.1232, Jan. 6, 2011. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1101.1232.

- T. Jakobsen, “A fast method for cryptanalysis of substitution ciphers,” Cryptologia, vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 265–274, 1995. [CrossRef]

- W. H. Samual, “Solving Substitution Ciphers” Department of Computer Science, University of Toronto. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14053080.

- A. Tseng, “high-quality-english-sentences,” Huggingface.co, Dec. 23, 2024. https://huggingface.

- Hugging Face, “Hugging Face. The AI community building the future. The platform where the machine learning community collaborates on models, datasets, and applications,” 2024. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.

- A. Vaswani et al., “Attention Is All You Need,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03762, 2017. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762.

- G. Bebis and M. Georgiopoulos, “Feed-forward neural networks,” in IEEE Potentials, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 27-31, Oct.-Nov. 1994. [CrossRef]

- P.-C. Chen, H. Tsai, S. Bhojanapalli, H. W. Chung, Y.-W. Chang ve C.-S. Ferng, “A Simple and Effective Positional Encoding for Transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08698, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.08698.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).