1. Introduction

Functional foods, including berries and virgin olive oil, have raised attention for health benefits in aging. Although strong evidence has been raised about Lamiaceae species activities,including those relevant to brain function, such as antioxidants, cholinesterase inhibition and anti-inflammatory properties [

1,

2], there are rare evaluations on the potential benefits of Lamiaceae species on the normal aging process. Li and colleagues (2022) reported that

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi, using an aging model with an injection of D-galactose in young adult rats, has a potential anti-aging effect [

3].

It is interesting to cite that a systematic review including clinical trials performed with healthy or participants with cognitive impairment, including dementia conditions, concluded that

Salvia officinalis and

S. lavandulaefolia may improve the cognitive performance both in healthy and patients [

4]. Several studies have reported in vitro anticholinesterase activity of several Salvia species, such as

Salvia lavandulaefolia and

Salvia leriifolia [

5,

6]. However there are few studies reporting in vivo anticholinesterase effects of Lamiaceae species. The neuroprotective properties of some members of the

Ocimum genus (family Lamiaceae) have also been studied.

Ocimum sanctum Linn is a species widely used in the Ayurveda traditional medicine, called as tulsi, their extracts protect against ischemia-reperfusion and hypoperfusion-induced cerebral damage, reducing the cellular membrane damage (antilipoperoxidant activity) [

7]. In vitro antioxidant activity and neuroprotective effects of

O. sanctum were observed on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in SH-SY5Y human neurons, such as reducing the lipid peroxidation levels and reactive species generation [

8]. Mataram et al (2021) showed the potential neuroprotective of

O. sanctum extract [

9]. In addition, it was demonstrated that

O. basilicum L. has antioxidant properties in several in vitro systems [

10]. Besides, treatment with

O. basilicum protects against ischemia-reperfusion and hypoperfusion-induced cerebral damage [

11,

12].

The present work is focused on

O. americanum L. (Lamiaceae, “alfavaca”, “manjericão, “Americanum basil”), which is commonly used for seasoning [

13], in order to open new insights about the potential use of this species as a nutraceutical or functional food. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first work investigating the potential neuroprotective effects of an

O. americanum extract. Our hypothesis was that

O. americanum is a neuroprotective species especially in the aging process by modulating anticholinesterase activity, oxidative stress and/or inflammatory status.

The aim of this study was to study in vitro and in vivo neuroprotective effects of Ocimum americanum ethanol extract (OAEE). Specifically we investigated (1) the effects of OAEE incubation in hippocampal slices of young adult and late middle-aged rats exposed to oxidative stress; (2) the functional (aversive memory performance) and neurochemical (hippocampal cellular oxidative state and anticholinesterase activity) effects of an acute treatment with OAEE, as well as (3) the impact of a chronic administration with a diet supplementation of OAEE on several biochemical parameters, such as cellular oxidative state, anticholinesterase activity and neuroinflammatory parameters, of hippocampus from young adult and late middle-aged male rats.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Preparation of the Ethanol Extract

Ocimum americanum (Lamiaceae) was collected in Rio Grande do Sul State (Brazil) and authenticated by Mara Rejane Ritter (Departamento de Botânica, Instituto de Biociências, UFRGS, RS, Brazil). Voucher specimens were deposited in the Herbario do Vale do Taquari (HVAT 1922) Botany and Paleobotany Sector of UNIVATES Natural Science Museum (Lajeado, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil).

One hundred grams of fresh leaves of

O. americanum was soaked in 1000 mL of ethanol (90%) for 7 days at room temperature. The solvent was filtered and dried under vacuum, resulting in the ethanol extract (OAEE). The content of total phenolic compounds in our extract was 23.61 QE. Total phenolic compounds content was determined using the Folin – Ciocalteu reagent, following a slightly modified Singleton’s method using quercetin as standard [

14].

2.2. Animals

Male Wistar rats aged 3 and 16-18 months-old were used. The animals were maintained under standard conditions (12 h light/dark, 22±2 °C) with food and water ad libitum. The NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication No. 80-23, revised 1996) was followed in all experiments. The Local Ethics Committee approved all handling and experimental conditions (GPPG-HCPA 09-638).

2.3. In vitro Experiments

2.3.1. Animals, Preparation and Incubation of Hippocampal Slices

Male Wistar rats aged 3 and 16-18 months were decapitated, and the hippocampi were quickly dissected out and transverse sections (400 µm) were prepared using a McIlwain Tissue Chopper. Slices were then transferred immediately into 24-well plates, each well containing 0.3 mL of HEPES-saline buffer (containing in mM): 120 NaCl; 25 HEPES; 10 glucose; 2 KCl; 1 CaCl

2; 1 MgSO

4; 1 KH

2PO

4; adjusted to pH 7.4. The medium was changed after 30 min by a fresh buffer and the slices were incubated with different concentrations of the OAEE (0, 0.1, and 1 μg/mL) for 60 min at 35°C [

15]. The medium was then changed for a fresh buffer in the absence or presence of H

2O

2 (2mM) for 60 mim at 35°C [

16]. After incubation with H

2O

2, cellular viability (mitochondrial activity) and cell damage (membrane lysis) assays were performed. The incubation of hippocampal slices from both 3- and 16-18 months-old rats with H

2O

2 resulted in marked changes in cellular viability (MTT assay). The H

2O

2 is widely used as an oxidative injury model in rat hippocampal slices [

16,

17]. For the in vitro assays OAEE was firstly dissolved in 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and was further adjusted to final concentration; a maximum final concentration of DMSO in OAEE-treated samples was 0.001%, which was used as a control group.

2.3.2. Cellular Viability

Mitochondrial activity was evaluated by the colorimetric 3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. Hippocampal slices were incubated for 30 min at 35°C in the presence of MTT (5 mg/mL). Active mitochondrial dehydrogenases of living cells cause cleavage and reduction of the soluble yellow MTT dye to the insoluble purple formazan, which was extracted in DMSO; the optical density was measured at 560/630 nm [

15].

2.3.3. Cellular Damage

Cell damage was quantified by measuring lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) released into the medium. After 60 min of incubation with H

2O

2, LDH activity was determined using a commercial kit (Doles Reagents, Goiânia, Brazil). Each experiment was normalized by subtracting the background levels of control wells. Samples were quantified using a standard curve; the optical density was measured at 490 nm [

17].

2.4. In Vivo Acute Experiments

2.4.1. Animals and Treatment

Male Wistar rats of 3 months of age were treated with saline, DMSO 20% (control group) or OAEE (100 and 300 mg/kg) by gavage. Animals received the treatments immediately after single training on inhibitory avoidance and were tested for short-term memory 90 minutes after training. Behavioral observations were performed in soundproof rooms during the same period of the day.

2.4.2. Inhibitory Avoidance Task

The single-trial step-down inhibitory avoidance (IA) conditioning was employed as a model of fear-motivated memory. The IA behavioral training and retention test procedures were described in previous reports [

20]. The IA apparatus was a 50 cm×25 cm×25 cm acrylic box (Albarsch, Porto Alegre) whose floor consisted of parallel caliber stainless steel bars (1 mm diameter) spaced 1 cm apart. A 7 cm wide, 2.5 cm high platform was placed on the floor of the box against the left wall. On the training trial, rats were placed on the platform and their latency to step down on the grid with all four paws was measured with an automatic device. Immediately after stepping down on the grid, rats received a 0.5 mA, 2.0 s foot shock and were removed from the apparatus. The test trials were procedurally identical to training, except that no foot shock was presented. Step-down latencies on the test trial (maximum 180 s) were used as a measure of IA retention.

2.4.3. Tissue Preparation

Rats were decapitated 30 minutes after the test on inhibitory avoidance; hippocampi were quickly dissected out and instantaneously placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at -70

oC until biochemical assays. For assays of cellular oxidative state, the hippocampi were homogenized in 10 volumes of ice-cold phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 2mM) and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF, 1mM) in a Teflon-glass homogenizer. The homogenate was centrifuged at 960 x

g for 10 min and the supernatant was used for the assays. To evaluate the acetylcholinesterase activity, the hippocampi were homogenized in 10 volumes of ice-cold phosphate buffer (0.5 M, pH 7.5) and centrifuged at 900 x

g for 10 min, the resulting supernatant was used as enzyme source [

18].

2.4.4. Reactive Species Levels

It was used 2’-7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as a probe to measure the reactive species content [

2]. An aliquot of the sample was incubated with DCFH-DA (100 μM) at 37

oC for 30 min. The formation of the oxidized fluorescent derivative (DCF) was monitored at excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 nm 525 nm, respectively. All procedures were performed in the dark and blanks containing DCFH-DA (no supernatant) were processed for measurement of autofluorescence [

18].

2.4.5. Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARS)

Lipid peroxidation (LPO) was evaluated by thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) test [

2]. Aliquots of samples were incubated with 10% trichloroacetic acid and 0.67% thiobarbituric acid. The mixture was heated (30 min) in a boiling water bath. Afterwards, n-butanol was added and the mixture was centrifuged. The organic phase was collected to measure fluorescence at excitation and emission wavelengths of 515 and 553 nm, respectively. 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane, which is converted to malondialdehyde (MDA), was used as standard.

2.4.6. Acetylcholinesterase Activity

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity was determined by slight modifications of a colorimetric method described by Ellman and colleagues [

19], using acetylthiocholine iodide (ASCh) as a substrate. The total volume of reaction mixtures was 300 µL (10 µL of supernatant, 30 µL of Ellman’s reagent [0.01 M 5-5’-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoic acid)], 30 µL of ASCh, 230 µL of buffer), and each sample of the enzyme source material was analyzed in triplicate. The blank reading was obtained for each reaction mixture after 10 min of incubation, before the addition of ASCh (75 mM). Thereafter, absorbance (412 nm) readings were taken for 4 min at 30-s intervals.

2.5. In Vivo Chronic Experiments

2.5.1. Animals and EEOA Supplementation

Male Wistar rats aged 3 and 16-18 months were randomly divided into six groups and fed diet with or without OAEE supplementation during 4 weeks. Animals had free access to isocaloric diets Commercial non-purified diet from Nuvilab-CR1 (Curitiba, Brazil; caloric density 4.16 cal/g) that contained (g/ 100 g) total fat 11, protein 22, fiber 3 ash 6, carbohydrates 56, salts, and vitamins as recommended by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (Horwitz W. Official methods of analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Association of Official Analytical Chemists, Washington, D.C. 1980). The animals received the experimental diets, 0% (control diet), 0.01% (diet supplemented with OAEE at a final concentration of 0.1 g/kg) and 0.2% (diet supplemented with OAEE at a final concentration of 2 g/kg) [

20]. The animals were observed daily for clinical signs of toxicity and mortality to clarify the toxicity profile of OAEE.

2.5.2. Tissue Preparation

After 4 weeks of supplementation, rats were decapitated and the hippocampi were quickly dissected out and instantaneously placed in liquid nitrogen and stored at -70oC until biochemical assays. For measurement of TNF-α and IL-1β content, the hippocampus was homogenized in phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4), containing 1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) and 1 mM PMSF. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 X g for 5 min at 4ºC and the supernatant was used. For assessment of reactive species levels, thiobarbituric acid reactive substances and acetylcholinesterase activity, the homogenization of hippocampal samples and the procedures were performed as described in the section in vivo acute experiments.

2.5.3. Measurement of Cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β, Content

The Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) levels in the hippocampus were determined using Ready-To-Go Cytokine Elisa Kit (eBioscience, catalog number 88-7346 and 88-6010, respectively) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.6. Protein Determination

Protein was measured by the Coomassie blue method using bovine serum albumin as standard [

21].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as percentage of control and are displayed as median (25th/75th percentiles) or mean (±SEM). The data distribution pattern was evaluated by the test of normality (Kolmogorov–Smirnov). The in vitro neuroprotective effects were evaluated by Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test with H2O2 exposure and treatments as factors. It was employed Kruskal–Wallis followed by Dunn’s test in inhibitory avoidance task and acetylcholinesterase activity data. The effect of acute treatment was evaluated by One-way ANOVA and post hoc Tukey test. The chronic supplementation effects were evaluated by Two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test with age and supplementation as factors. Analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software on a PC-compatible computer. In all tests, p<0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3. Results

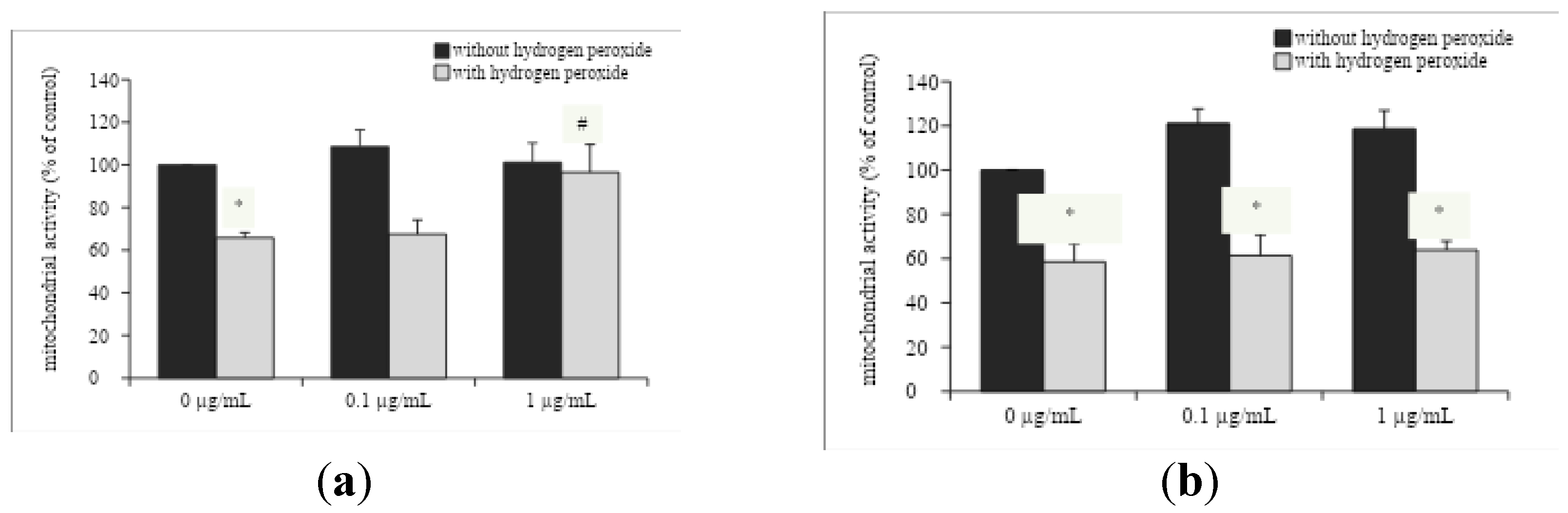

3.1. In Vitro Neuroprotective Effect of Ocimum Americanum Extract in Young Adult and Late Middle-Aged Rats

The H

2O

2 incubation significantly impaired mitochondrial activity in hippocampal slices from young adult and late middle-aged rats (

Figure 1A, F

(1,36)=22.164, p<0.0001;

Figure 1B, F

(1,44)=93.416, p<0.0001; respectively). The in vitro incubation with 1 µg/mL OAEE reversed H

2O

2-induced decreases on mitochondrial activity in hippocampal slices from young adult rats (p=0.05), without any effect in aged rats. In accordance, there was a significant interaction between two factors, H

2O

2 and OAEE (F

(2,36)=5.530, p=0.042).

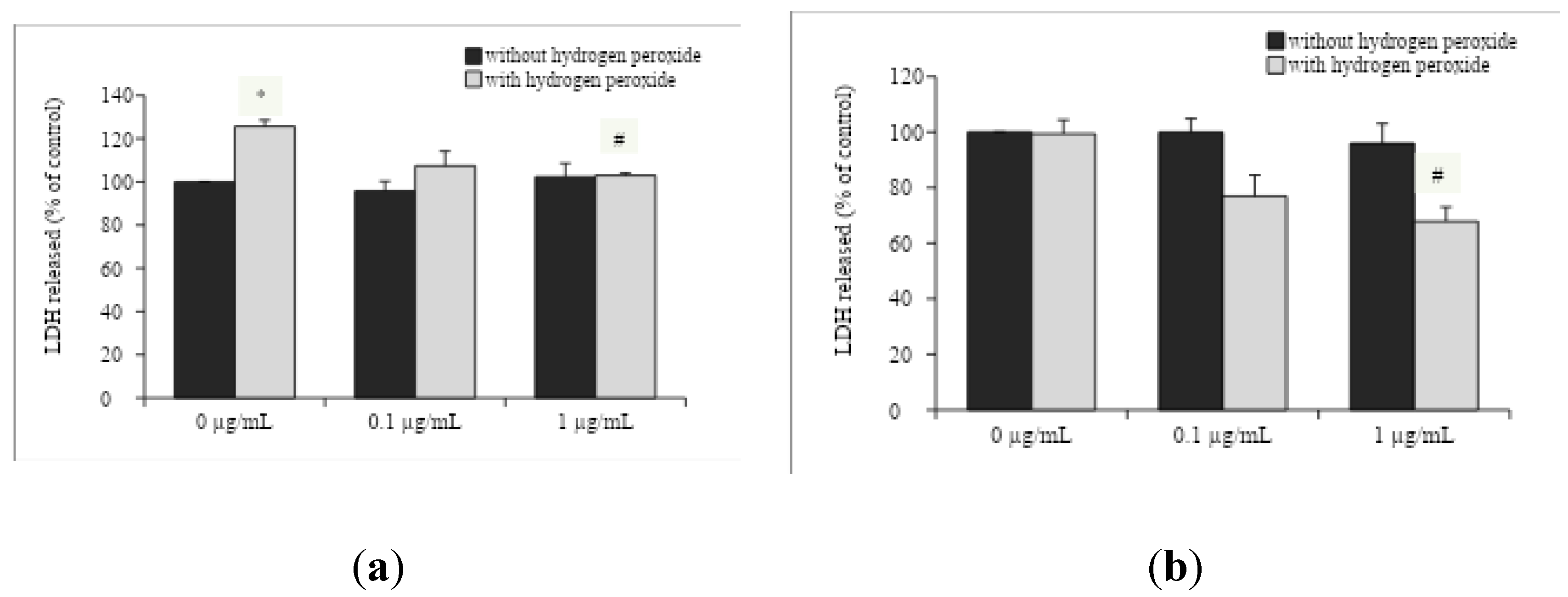

The exposure to H

2O

2 enhanced the LDH released into the incubation medium by hippocampal slices from young adult rats (

Figure 2A, F

(1,33)=14.532, p=0.001), without any effect in aged rats (

Figure 2B). Interestingly, the in vitro incubation with 1 μg/mL OAEE reversed H

2O

2 -induced increases in LDH released by slices from young adult (F

(2,33)=4.956, p=0.014) and aged rats (F

(2,41)=5.315, p=0.009).

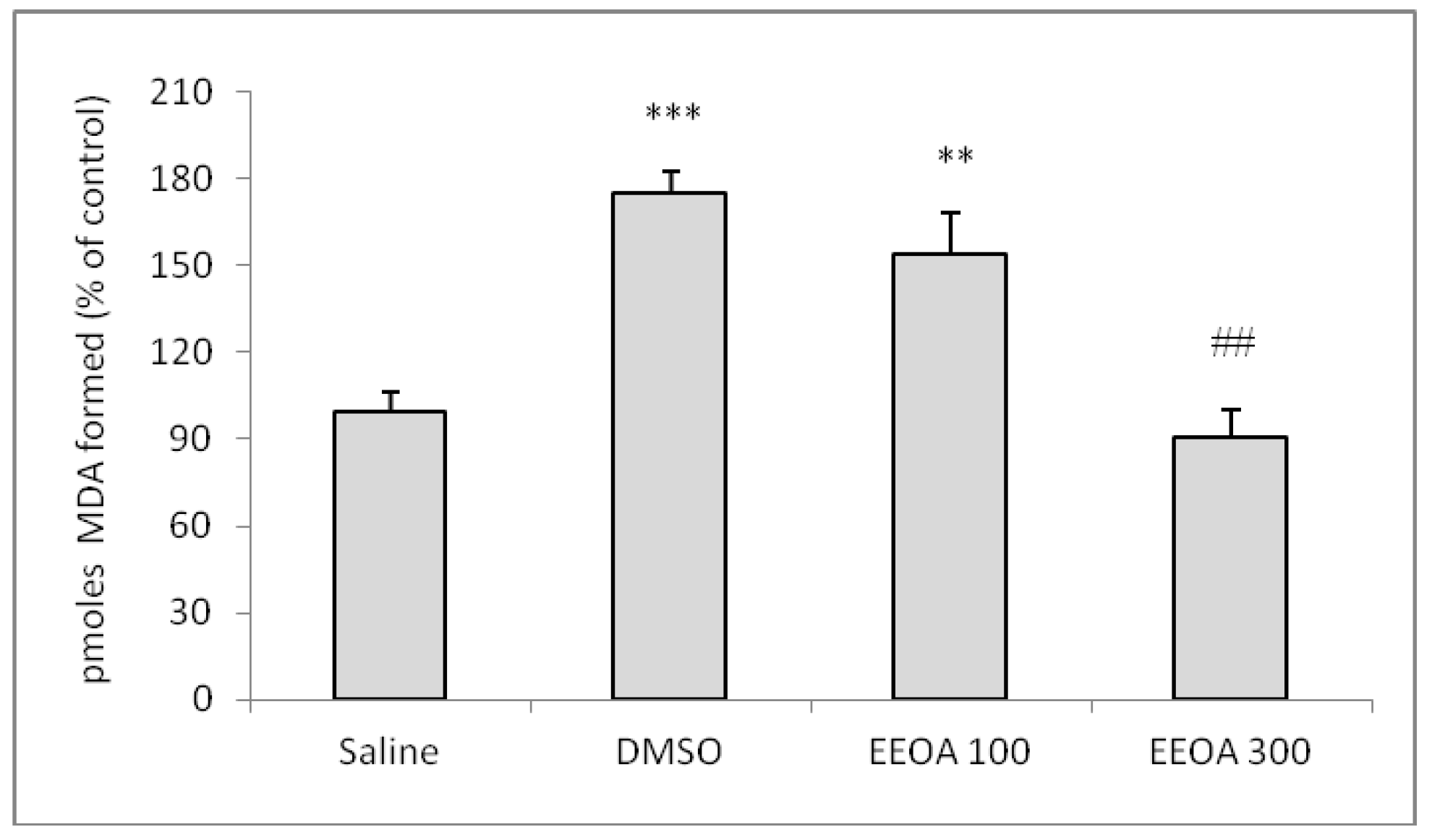

3.2. Effect of acute treatment with Ocimum americanum extract in young adult rats

Latencies to step down from the platform during training did not differ among groups (data not shown). The immediately post-training acute treatment with OAEE did not alter the short-term aversive memory evaluated in the inhibitory avoidance task. The acute treatment with OAEE did not modify the species reactive levels in hippocampus, evaluated by formation of the DCF (data not shown). The administration (v.o.) of DMSO significantly increased the LPO levels when compared to saline group, and 300 mg/kg OAEE was able to reverse this effect to control levels (

Figure 3, F

(3,20)=17.78; p<0.0001). In addition, the acute administration of OAEE did not alter the AChE activity in the hippocampus from young adult rats (data not shown).

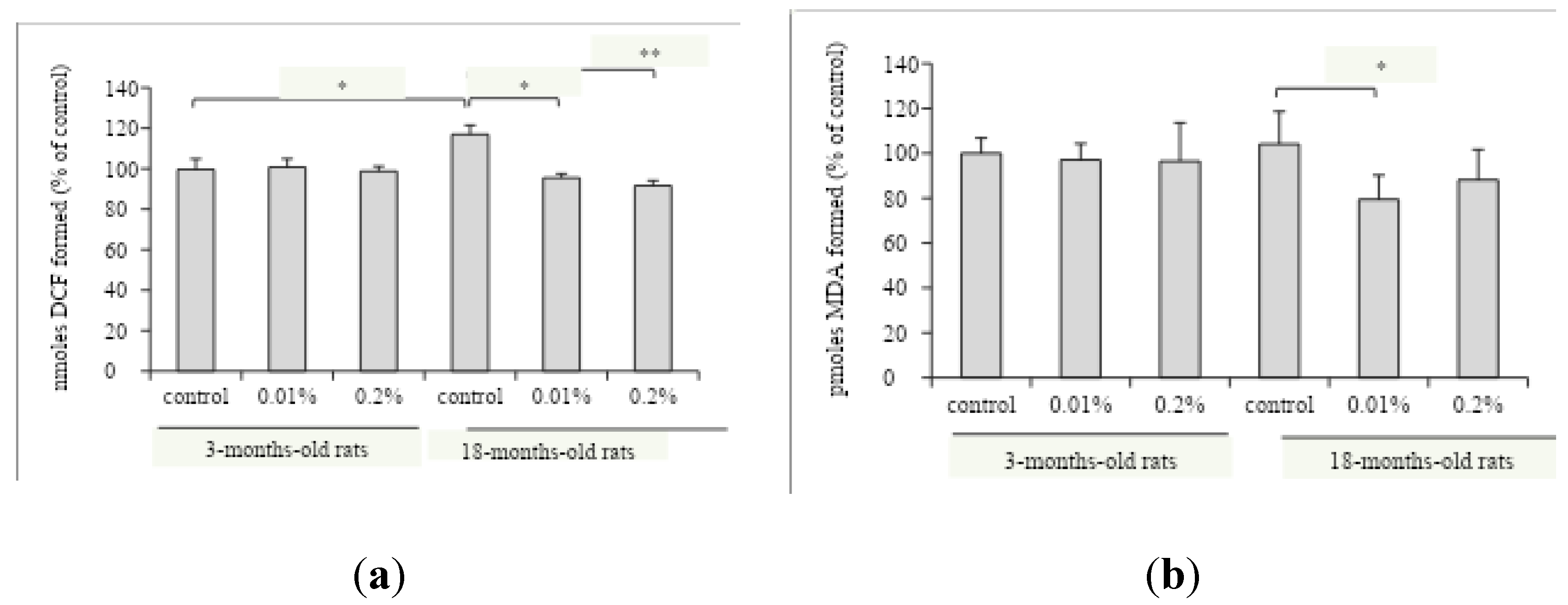

3.3. Effect of Ocimum Americanum Extract Supplementation in Young Adult and Aged Rats

The supplementation with OAEE (0.01 and 0.2%) during 4 weeks decreased the reactive species content in the hippocampus of late middle-aged rats compared to those obtained from the late middle-aged control group (

Figure 4A, p<0.0001). An age-dependent effect on reactive species levels was found (

Figure 4A, F

(1,39)=4.311, p=0.046). Interestingly, the OAEE did not modify the reactive species content in the hippocampus from young adult rats. Besides, there was a significant interaction between two factors, age and OAEE supplementation (F

(2,39)=18.669, p<0.0001). The supplementation with 0.01% OAEE reduced the TBARS levels in aged rats (

Figure 4B, p=0.032), without any effect in young adult rats. Furthermore, two-way ANOVA showed the effect of OAEE supplementation (F

(2,31)=3.354, p=0.051).

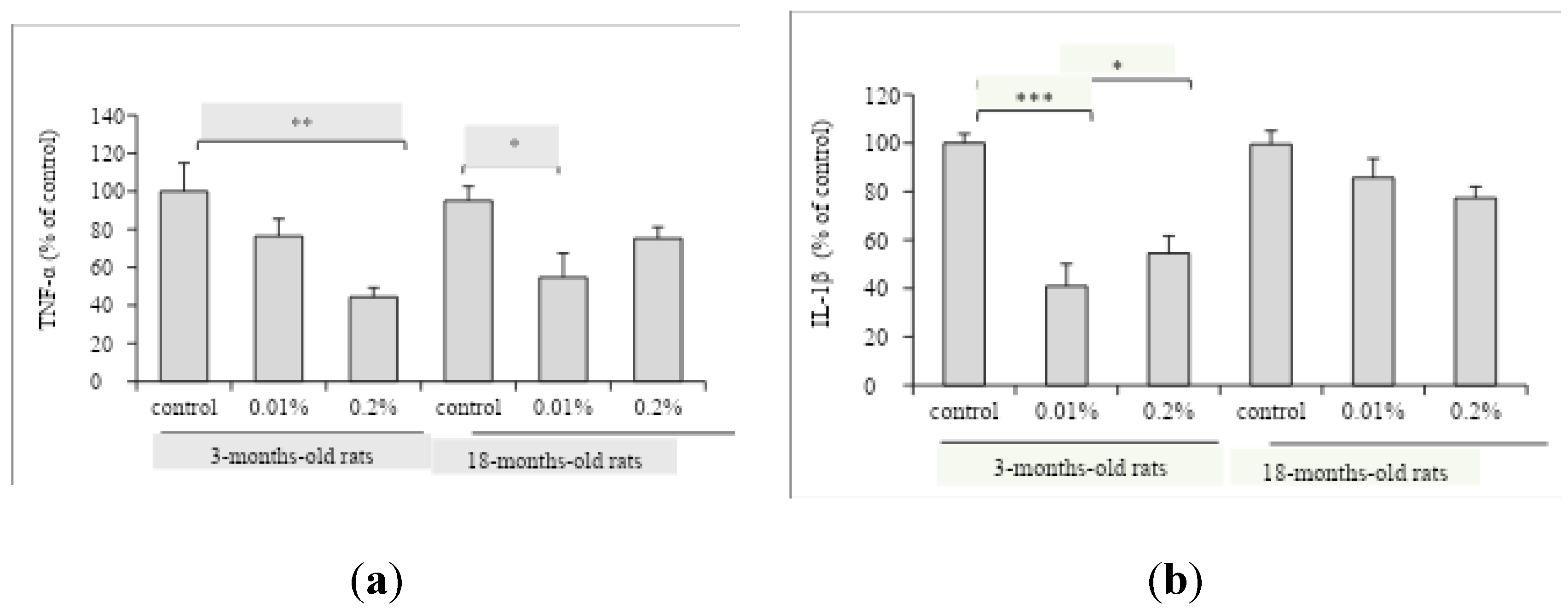

Besides, the modulation of OAEE supplementation on neuroinflammatory processes in the hippocampus from young adult and aged rats was evaluated. The OAEE reduced the content of TNF-α in hippocampus from young adult and late middle-aged rats, since two-way ANOVA showed the effect of OAEE supplementation (F

(2,27)=8.421, p=0.002,

Figure 5A). The OAEE (0.01% and 0.2%) decreased the content of IL-1β in the hippocampus, however there was an interaction between two factors, age and OAEE supplementation (F

(2,31)=5.296, p=0.012,

Figure 5B) because major changes were induced in young adult. The chronic supplementation with OAEE at tested doses did not modify the AChE activity in both ages (data not shown).

4. Discussion

The findings raised here demonstrated that the extract of O. americanum has neuroprotective action especially in the aging process. Mechanistically, Ocimum americanum-mediated neuroprotection can be attributed to its antioxidant and anti-neuroinflammatory properties. To our knowledge, this is the first work investigating the O. americanum effects in the aging process.

O. americanum extract was able to protect cell membranes, because it was observed reduction of released LDH in hippocampal slices from both young adult and late middle-aged rats, while mitochondrial activity (MTT assay) was improved only in young adult rats, without any effect in late middle-aged ones. Accordingly, the neuroprotective action of some species of Lamiaceae family against the oxidative damage induced by H

2O

2 in different cell types have been described [

8,

22,

23]. Asadi and colleagues [

22] demonstrated that the pre-treatment with

Salvia species from Iran significantly protected neuron-like PC12 cells against H

2O

2 -induced toxicity.

Rosmarinus officinalis was effective attenuating the disruption of mitochondrial membrane and cell death induced by H

2O

2 in SH-SY5Y cells [

22]. It is relevant to consider that even in the aging process, OAEE had beneficial effects on cellular membranes. This in vitro data may be related to other findings here described, since both acute and chronic treatments reduced LPO.

Acute administration of OAEE in young adult rats was able to reverse increases of LPO induced by DMSO. DMSO can exhibit a pro-oxidant action [

24]. In accordance, chronic administration of

O. americanum extract was able to decrease the LPO in 16-18-months-old rats. These findings are in agreement with those that describe the effect of other

Ocimum species preventing the LPO induced by ischemia/reperfusion and noise exposure [

11,

25]. Therefore, it is possible to suggest that the effect of this extract on H

2O

2 –induced cell damage can be related, at least in part, with its antilipoperoxidant activity. Kelm and colleagues (2000) reported that all flavonoid compounds characterized from

O. sanctum, such as apigenin have excellent antioxidant activity, with the exception of cirsimaritin, besides several compounds have anti inflammatory properties by cyclooxygenase inhibition [

26].

In accordance with our previous results, reactive species content was significantly increased in hippocampus from 16-18-months-old rats [

27], which seems to be critically involved in pathological alterations related to aging. This is relevant, since we previously observed that the free radical levels and total antioxidant capacity were significantly altered in the hippocampus from mature rats (6 months) [

18]. Accordingly, a dietary intake of a variety of antioxidants, like herbs and spices, might be beneficial for preserving brain function [

20]. A longitudinal study found a significant inverse correlation between flavonoids intake and the risk of dementia in a cohort of subjects above 65 years of age [

28]. Chronic supplementation with OAEE for 4 weeks was able to reduce the age-induced increase of reactive species levels. Taken together, we can suggest that

O. americanum can have adaptogenic properties, normalizing the steady state (homeostasis) against injury conditions [

29].

Another novel finding that emerged from our study involves a potential interaction between

O. americanum and neuroinflammatory parameters. The chronic supplementation with OAEE modulated pro-inflammatory cytokines levels in hippocampus from 3- and 16-18-months-old rats. Specifically, OAEE was able to reduce the TNF-α content in 3- and 16-18-months-old rats, as well the IL-1β levels in hippocampus from 3-months-old rats, with a modest impact in late middle-aged animals. These results are relevant since it was described that inflammatory cytokines profile may be involved, at least in part, to the aging-related impairments [

30].

Both the acute treatment or the chronic supplementation with

O. americanum extract did not alter hippocampal AChE activity. Considering that several reports have shown in vitro anticholinesterase activities of species of Lamicaeae family [

6], our results indicate the need of studies investigating the in vivo effect with herbs and spices on this parameter. Chiang et al (2021) demonstrated that a sage extract (

Salvia officinalis) was able to induce Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression, a signaling protein related to neuroprotection, and memory performance. This work opened new perspectives, including those involved with neurotrophins [

31].

The ethanol extract of Ocimum americanum seems to have neuroprotective compounds. Although, at this point, neither the active compound(s) nor the exact mechanism(s) by which O. americanum extract exerts its activities are completely known, although, it is fair to assume that the activities here described for OAEE can be related at least in part to the presence of phenolic compounds, which are widespread found in Lamiaceae family.

5. Conclusions

We can point out that the antioxidant properties, preventing the lipoperoxidation, as well anti-neuroinflammatory effect, might be related at least in part to neuroprotective effect. Our findings are the first evidence to support the idea of the potential use of Ocimum americanum as a nutraceutical or functional food in the aging process. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to understand the molecular mechanisms involved with its neuroprotective effect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V., G.L. and I.R.S.; methodology, C.V., G.L., K.B., C.S., F.S.M., A.V., G.L.V.P. and I.R.S.; validation, C.V., G.L., K.B., A.V. and G.L.V.P.; formal analysis, C.V., G.L., K.B., A.V. and I.R.S; investigation, C.V., G.L., K.B., C.S., F.S.M., A.V., G.L.V.P.; resources, G.L.V.P., C.A.N. and I.R.S.; data curation, C.V.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V., C.A.N. and I.R.S.; writing—review and editing, C.A.N. and I.R.S.; visualization, C.V., G.L., A.V., C.A.N. and I.R.S.; supervision, I.R.S.; project administration, I.R.S..; funding acquisition, I.R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Brazilian funding agencies: CNPq (Grant - 476634/2013-0) CNPq fellowships I.R. Siqueira (308040/2022-8), C. Vanzella, C. Spindler, A. Vizuete); Graduate Research Group (GPPG/FIPE-Fundo de incentivo à pesquisa e eventos of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA, Grant # 09-638); CAPES fellowships (G.A. Lovatel; K. Bertoldi; F.S. Moysés).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Local Ethics Committee approved all handling and experimental conditions (GPPG-HCPA 2009-638). The NIH “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication No. 80-23, revised 1996) was followed in all experiments, in accordance with Law 11,794, called “Arouca Law”.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OAEE |

Ocimum americanum ethanol extract |

| MTT |

3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide |

| LDH |

lactate dehydrogenase |

| EDTA |

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid |

| PMSF |

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride |

| DCFH-DA |

2’-7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate |

| LPO |

lipid peroxidation |

| TBARS |

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| MDA |

malondialdehyde |

| AChE |

acetylcholinesterase |

| ASCh |

acetylthiocholine iodide |

| PBS |

phosphate buffer saline |

| EGTA |

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid |

| IL-1β |

interleukin-1β |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α |

References

- Kennedy, D.O.; Scholey, A.B. The Psychopharmacology of European Herbs with Cognition-Enhancing Properties. Curr. Pharm. Des 2006, 12 (35), pp. 4613–4623. [CrossRef]

- Eidi, M.; Eidi, A.; Bahar, M. Effects of Salvia officinalis L. (sage) leaves on memory retention and its interaction with the cholinergic system in rats. Nutrition 2006, 22(3), pp. 321-326, . [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, L.; Gao, L.; Du, G.; Qin, X.; Zhou, Y. The leaves of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi attenuate brain aging in D-galactose-induced rats via regulating glutamate metabolism and Nrf2 signaling pathway. Exp Gerontol. 2022, 170, 111978. [CrossRef]

- Miroddi, M.; Navarra, M.; Quattropani, M.C.; Calapai, F.; Gangemi, S.; Calapai, G. Systematic review of clinical trials assessing pharmacological properties of Salvia species on memory, cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2014, 20(6), 485-95. [CrossRef]

- Perry, N.S.; Houghton, P.J.; Theobald, A.; Jenner, P.; Perry, E.K. In-vitro Inhibition of Human Erythrocyte Acetylcholinesterase by Salvia lavandulaefolia Essential Oil and Constituent Terpenes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000 52(7), pp. 895–902. [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, M.R.; Tundis, R.; Conforti, F.; Menichini, F.; Bonesi, M.; Nadjafi, F.; Frega, N.G.; Menichini, F. Salvia leriifolia Benth (Lamiaceae) extract demonstrates in vitro antioxidant properties and cholinesterase inhibitory activity. Nutr Res. 2010 30(12), pp. 823-830. [CrossRef]

- Yanpallewar, S.U.; Rai, S.; Kumar, M.; Acharya, S.B. Evaluation of antioxidant and neuroprotective effect of Ocimum sanctum on transient cerebral ischemia and long-term cerebral hypoperfusion. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004 74(1), pp. 155-164. [CrossRef]

- Venuprasad, M.P.; Hemanth Kumar, K.; Khanum, F. Neuroprotective effects of hydroalcoholic extract of Ocimum sanctum against H2O2 induced neuronal cell damage in SH-SY5Y cells via its antioxidative defence mechanism. Neurochem Res. 2013 38(10), pp.2190-200. [CrossRef]

- Mataram, M.B.A.; Hening, P.; Harjanti, F.N.; Karnati, S.; Wasityastuti, W., Nugrahaningsih, D.A.A.; Kusindarta, D.L.; Wihadmadyatami, H. The neuroprotective effect of ethanolic extract Ocimum sanctum Linn. in the regulation of neuronal density in hippocampus areas as a central autobiography memory on the rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Chem Neuroanat. 2021 111:101885. [CrossRef]

- Kaurinovic, B.; Popovic, M.; Vlaisavljevic, S.; Trivic, S. Antioxidant capacity of Ocimum basilicum L. and Origanum vulgare L. extracts. Molecules 2011 16(9), pp. 7401–7414. [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.S.; Arora, S.; Shri, R. Role of Ocimum basilicum L. in prevention of ischemia and reperfusion-induced cerebral damage, and motor dysfunctions in mice brain. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011 137(3), pp. 1360-1365. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Krishan, P.; Shri, R. Improvement of memory and neurological deficit with Ocimum basilicum L. extract after ischemia reperfusion induced cerebral injury in mice. Metab Brain Dis 2018 33, pp. 1111–1120. [CrossRef]

- Yucharoen, R.; Anuchapreeda, S.; Tragoolpua, Y. Anti-herpes simplex virus activity of extracts from the culinary herbs Ocimum sanctum L., Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum americanum L. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011 10(5), pp. 860-866.

- Ivanova, D.; Gerova, D.; Chervenkov, T.; Yankova, T. Polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of Bulgarian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol. 2005 96, pp. 145-150. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.R.; Cimarosti, H.; Fochesatto, C.; Nunes, D.S.; Salbego, C.; Elisabetsky, E.; Netto, C.A. Neuroprotective effects of Ptychopetalum olacoides Bentham (Olacaceae) on oxygen and glucose deprivation induced damage in rat hippocampal slices. Life Sci 2004 75(15), pp. 1897–1906. [CrossRef]

- Posser, T.; Franco, J. L.; dos Santos, D.A.; Rigon, A.P.; Farina, M.; Dafre, A.L.; Teixeira Rocha, J.B.; Leal, R.B. Diphenyl diselenide confers neuroprotection against hydrogen peroxide toxicity in hippocampal slices Brain Res 2008 1199, pp. 138-147 . [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.R.; Elsner, V.R.; Leite, M.C.; Vanzella, C.; F.; Moysés, D.S.; Spindler, C.; Godinho, G.; Battú, C.; Wofchuk, S.; Souza, D.O.; Gonçalves, C.A.; Netto, C.A. Ascorbate uptake is decreased in the hippocampus of ageing rats,” Neurochem Int. 2011 58, pp. 527-532. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.R.; Fochesatto, C.; de Andrade, A.; Santos, M.; Hagen, M.; Bello-Klein, A.; Netto, C.A. Total antioxidant capacity is impaired in different structures from aged rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005 23(8), pp. 663–671. [CrossRef]

- Ellman, G.L.; Courtney, K.D.; Andres, V.; Featherstone, R. M. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1961 7, pp. 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Kolosova, N.G.; Shcheglova, T.V.; Sergeeva, S.V.; Loskutova, L.V. Long-term antioxidant supplementation attenuates oxidative stress markers and cognitive deficits in senescent-accelerated OXYS rats,” Neurobiol Aging. 2006 27(9), pp. 1289-1297. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding,” Anal Biochem 1976 72(1-2), pp. 248-254. [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Ahmadiani, A.; Esmaeili, M.A.; Sonboli, A.; Ansari, N.; Khodagholi, F. In vitro antioxidant activities and an investigation of neuroprotection by six Salvia species from Iran: A comparative study. Food Chem Toxicol. 2010 48(5), pp. 1341-1349. [CrossRef]

- Park, S.E.; Kim, S.; Sapkota, K.; Kim, S.J. Neuroprotective effect of Rosmarinus officinalis extract on human dopaminergic cell line, SH-SY5Y. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010 30(5), pp. 759-767. [CrossRef]

- Sanmartín-Suárez, C.; Soto-Otero, R., Sánchez-Sellero, I.; Méndez-Álvarez, E. Antioxidant properties of dimethyl sulfoxide and its viability as a solvent in the evaluation of neuroprotective antioxidants. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2011 63(2), pp. 209-215. [CrossRef]

- Bora, K.S.; Shri, R.; Monga, J. Cerebroprotective effect of Ocimum gratissimum against focal ischemia and reperfusion-induced cerebral injury. Pharm. Biol. 2011 49(2), pp. 175–181. [CrossRef]

- Kelm, M.A.; Nair, M.G.; Strasburg, G.M.; DeWitt, D.L. Antioxidant and cyclooxygenase inhibitory phenolic compounds from Ocimum sanctum Linn. Phytomedicine. 2000 7(1), pp. 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.R.; Cimarosti, H.; Fochesatto, C.; Salbego, C.; Netto, C.A. Age-related susceptibility to oxygen and glucose deprivation damage in rat hippocampal slices Brain Res. 2004 1025(1-2), pp. 226-230. [CrossRef]

- Commenges, D.; Scotet, V.; Renaud, S.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Dartigues, J.F. Intake of flavonoids and risk of dementia. Eur J Epidemiol 2000 16(4), pp. 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Richard, E.J.; Illuri, R.; Bethapudi, B.; Anandhakumar, S.; Bhaskar, A.; Velusami, C.C.; Mundkinajeddu, D.; Agarwal, A. Anti-stress Activity of Ocimum sanctum: Possible Effects on Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis. Phytother Res. 2016 30(5), pp. 805-814. [CrossRef]

- Lovatel, G.A.; Elsner, V.R.; Bertoldi, K.; Vanzella, C.; Moysés, F.S.; Vizuete, A.; Spindler, C.; Cechinel, L.R.; Netto, C.A.; Muotri, A.R.; Siqueira, I. R. Treadmill exercise induces age-related changes in aversive memory, neuroinflammatory and epigenetic processes in the rat hippocampus. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2013 101, pp. 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, N.; Ray, S.; Lomax, J.; Goertzen, S.; Komarnytsky, S.; Ho, C.T.; Munafo, J.P. Jr. Modulation of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) Signaling Pathway by Culinary Sage (Salvia officinalis L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2021 9 22(14). p.7382. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).