1. Introduction

The water solvation effect exerts a profound influence on chemical and biological systems involving ions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. The hydration state of ions not only dictates ion transfer across various ion - conducting channels, such as those present in membranes and cells, but also affects the efficiency and capacity of ion adsorption within porous materials, including zeolites and organic frameworks [

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, hydration plays a crucial role in solvent extraction processes [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Despite the long - standing interest and extensive research on lithium solvent extraction in the lithium recovery field [

15,

16,

17,

18], particularly regarding the tri-butyl-phosphate ester (TBP) -FeCl

3 synergistic extraction system [

19,

20,

21,

22], its separation mechanism remains elusive from a computational perspective. Although recent DFT studies have shown that the HOMO - LUMO gap difference and electronic energy difference govern the extraction capabilities of TBP and tri-octyl-phosphate ester (TOP) [

23,

24], the Gibbs free energy changes associated with lithium and magnesium extraction consistently suggest that the extraction of these two ions is thermodynamically similar. Paradoxically, the binding energy of the extractant with magnesium is significantly higher than that with lithium. This discrepancy is likely attributed to inaccurate calculations of ion hydration in aqueous media. Therefore, a systematic and comprehensive investigation of the solvation states of Li

+ and Mg

2+ in magnesium brine is essential to clarify this conundrum.

Traditionally, solvation studies predominantly rely on the Molecular Dynamics (MD) method, treating the solvent as a continuous medium [

25,

26,

27], However, when applied to calculate water solvation, these models often fall short. This is because water solvation involves not only electrostatic attraction but also hydrogen bonding between ions and water molecules. A more accurate approach to studying solvation utilizes the explicit solvation model, which, although more computationally expensive, optimizes the geometry of ions in the presence of solvent molecules. Inspired by this explicit solvation approach, a novel concept emerges. By treating different solvation particles as clusters and expressing the solvation equilibrium as the Gibbs free energy change associated with the transfer reaction from one cluster to another, it becomes possible to efficiently determine the existing states of ions in solutions containing both magnesium and lithium.

A variety of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and post-Hartree-Fock (HF) calculation methods have been employed to elucidate solvation energies, cluster structural parameters, and theoretical spectra [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Extensive research efforts have separately focused on water clusters using diverse methodologies [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], as well as the hydration of Li

+ [

41,

42] and Mg

2+ [

43,

44,

45]. Liu et.al [

46] systemically investigated the clusters of

via DFT methods at the ωB97XD/6-311++G(d,p) theory level, Their findings indicated that a four - coordinated structure is the preferred configuration for the first hydration sphere, and when n ≥ 12, the second hydration layer consists of 8 water molecules. Vasilescu et al. [

47] investigated the magnesium hydration of

via DFT on the BPW91/6-311++G(3d,3p) theory level, and their hydration analysis showed excellent agreement with literature data and vibrational spectra. While these previous studies have yielded significant insights into the hydration of water, lithium, and magnesium individually, several limitations exist. Notably, during the optimization of magnesium hydration clusters, the dispersion correction, which is crucial for accurately calculating weak interactions such as hydrogen bonds, was not considered. Additionally, the lithium and magnesium hydration clusters were studied at different theoretical levels, rendering energy comparisons and the exploration of hydration equilibrium in mixed solutions challenging. In recent years, the D4 dispersion correction for wB97 - series basis sets has been demonstrated to be highly effective in energy - related studies [

48,

49], Therefore, to comprehensively understand the hydration equilibrium between lithium and magnesium hydration clusters, it is essential to perform calculations on the same theoretical level with D4 correction for both water and metal hydration clusters.Aiming to accurately quantify the hydration energy differences between magnesium and lithium in high - magnesium solutions and to establish a solid foundation for understanding the mechanisms underlying metal separation in aqueous phases, this study employed DFT with dispersion correction to calculate the structures of magnesium, lithium, and water clusters. Subsequently, the binding energies, hydration energies of these three types of clusters, and the solvation equilibrium of ions in high - magnesium solutions were analyzed through hydration reactions and water transfer processes.

The proposed method for calculating hydration energies in solution and exploring hydration equilibria offers a novel perspective. It is expected to facilitate more precise calculations of solvation energy changes in solvent extraction, membrane - based separations, and other related fields of separation science, thereby advancing the fundamental understanding and practical applications of these separation processes.

2. Calculation Detail

2.1. Initial Guess of the Different Clusters

As the hydration number increases, the structure of the hydration cluster becomes increasingly complex. Different computational methods may yield varying lowest - energy structures for the same cluster. To develop a more consistent and reliable cluster construction method, a uniform water - coordination principle was adopted. The core concept of this principle is to arrange the hydration water molecules around a particle in a spherical layer - by - layer manner. A new layer is formed only when the inner layer is saturated. When the central particle is a water molecule, the first hydration sphere consists of four water molecules, with each water molecule forming four hydrogen bonds and having a coordination number of four. For central ions such as lithium or magnesium, the first hydration sphere contains 4 and 6 water molecules, respectively, and the water molecules in the first sphere have a coordination number of 3. As the number of hydration water molecules increases, the coordination number of water molecules increments one by one until all reach a coordination number of 3.

The most stable structures of hydrated lithium and magnesium documented in the literature align well with this construction concept. The sole deviation is observed in water clusters, where the orientation of hydrogen bonds can give rise to some inconsistencies. A minor limitation of this construction principle is that the total energy of specific water clusters may exhibit slight variations. Nevertheless, this has negligible implications for the study of hydrated lithium and magnesium ions. In the present research, the water - transfer reaction from water clusters to ion clusters is the key factor governing hydration energy. Consequently, the solvent effects calculated using traditional implicit solvation models are not incorporated into the analysis. Given that the first hydration number of magnesium is 6, the second hydration sphere can accommodate up to 12 water molecules, as 12 hydrogen bonds can form between the water molecules in the first and second hydration spheres. Taking into account the water-to-magnesium ratio in brine, to comprehensively understand magnesium hydration in high-magnesium brine, a hydration number of 18 must be considered in this study. The detailed assumptions and justifications for this consideration are presented in the

supplementary materials. Same principle was also fit for the lithium and water clusters, so the

,

and

were calculated in this investigation.

2.2. Theoretical Calculation of the Different Clusters

The geometry structures of the constructed clusters were optimized using DFT at the wB97X - D4/def2 - TZVPPD level [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54] within the ORCA quantum chemistry package (version 5.0.4) [

55], The inclusion of D4 dispersion correction enhanced the calculation accuracy. Subsequently, a Hessian analysis was performed at the same theoretical level to verify that the obtained structures corresponded to the global minima on the potential energy surface. All structural visualizations were generated using Avogadro, leveraging the support provided by ORCA 4.2.1. The initial guessed structures, optimized structures of the clusters, along with some stable structural water clusters derived from the literature, are predominantly presented in the

supplementary materials.

For water clusters, the formation Gibbs free energy of a water cluster

can be expressed as Equation 1, and hydration Gibbs free energy of a water cluster

formed from

should be expressed as Equation 2

In an equilibrium solution, water transfer reactions are continuously occurring, with the Gibbs free energy change of the reaction approaching zero. Under these conditions, the solvation energy of an ion can be expressed as n*m

-1 times the Gibbs energy of formation of the most stable water cluster

in the solution, where n represents the hydration number of the ion and m is the number of water molecules in the cluster. The Gibbs free energy change for the water transfer reaction and the Gibbs free energy of formation of the ions are presented in Equation 3 and Equation 4, respectively. The Gibbs free energy values (at a concentration of 1 mol/L) used to calculate the ion hydration energy and the reaction Gibbs free energy changes are equivalent to the gaseous - phase Gibbs free energy values (at 1 atm) of the particles obtained directly from the thermodynamic analysis of frequency calculations. A liquid - standard correction of 1.89 kcal/mol is added to these gaseous - phase values to account for the transition from the gas phase to the solution phase.

In the equations,

stands for the Gibbs free energy of water transfer reaction from metal hydration ion

to

and forms

, and

is the formation Gibbs free energy of the

. Then the water transfer reaction Gibbs free energy change between different ions can be described by Equation 5, where the L is for another metal ion. For example, when M is Mg and L is lithium, the Gibbs free energy change in Equation 5 will stands the water transfer reaction from magnesium to lithium ion.

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Structure and Solvation of Water Cluster

Since water can adopt numerous distinct stable structures corresponding to various local minima on the potential energy surface, a meticulous comparison is essential when evaluating the calculated structures derived from the initial guesses in this study and those reported in previous literature to ascertain their stability.

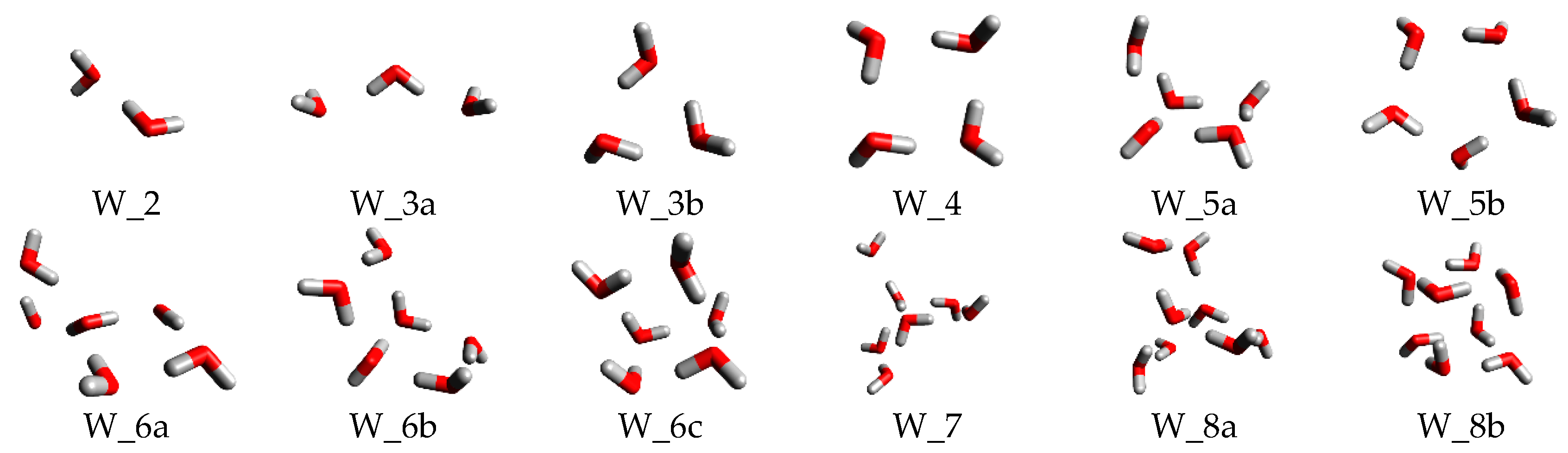

Figure 1 presents the cluster structures of

, encompassing both the configurations generated using the construction method developed in this research and those inspired by prior studies.

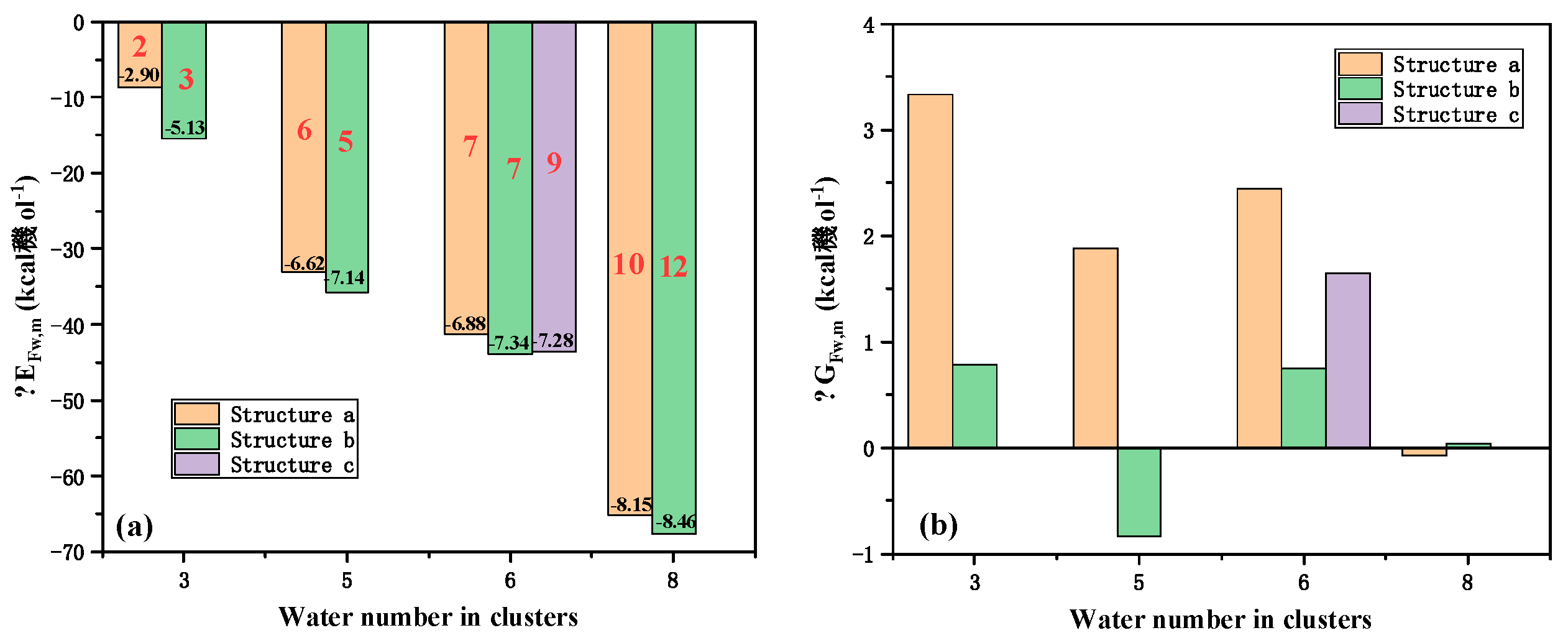

By easily compare the structures from our initial design and the literatures, we can find that difference happened between the clusters with water number of 3, 5, 6, 8. To better understand the influence of different structures on the formation Gibbs free energy, the

and

for the four clusters were calculated and showed in

Figure 2 with the hydrogen bonding number, the bonding energy

calculation also followed the Euq.1 where the Gibbs free energy was replaced by the electron energy obtained directly from the optimization process. The

for the cluster with a same water number almost has an equal value except the

, the difference may be caused by the triangle structure had one more hydrogen bonding, indicating that the hydrogen bonding formation in the cluster had a significant impact on

. By comparing the average bonding energy

, we can find that the dispersed structure with bigger circle may have a relatively larger average electron energy change due to a smaller tension and easy formation direction for hydrogen bonding, demonstrating that

has close relationship with the hydrogen bonding strength and direction. That is the water cluster which has more hydrogen bonds and less bended hydrogen bonds may have a bigger

. When the thermodynamics for clusters was considered, the difference in the electron energy seemed to be eliminated where the final

for each cluster was near zero and most of them even become positive, determining that the water cluster formation process may have little impact on the hydration of the ions thermodynamically. Even though the existing of

in low temperature can well accounted these phenomena [

56], it was still unexpected and beyond understanding, indicating that the thermodynamics may play an important role on the thermal stability of water clusters and suggesting that more effective and precise thermal analysis based on quantum study should be conducted to confirm this phenomenon. Considering the hydration Gibbs free energy water and that the hydration Gibbs energy of an ion is always negative, there should be little free water cluster in solutions, especially for the water clusters with water number within 1~8.

Besides the interesting phenomena above, we can summarize that water clusters with same water number in the cluster seem to have a similar bonding length and the stable optimized structures in literature can all be obtained in this study by using the similar structure as initial guess, and that the different Gibbs free energies are actually almost the same regardless of the different structures with equal water number, indicating that if we only care about the Gibbs free energy of a water cluster, the cluster construction method in this investigation can be applied and will not impact too much on the hydration Gibbs free energy calculation. To better understand the water clusters thermodynamical formation and stability, the

and

for water cluster

were calculated and demonstrated in

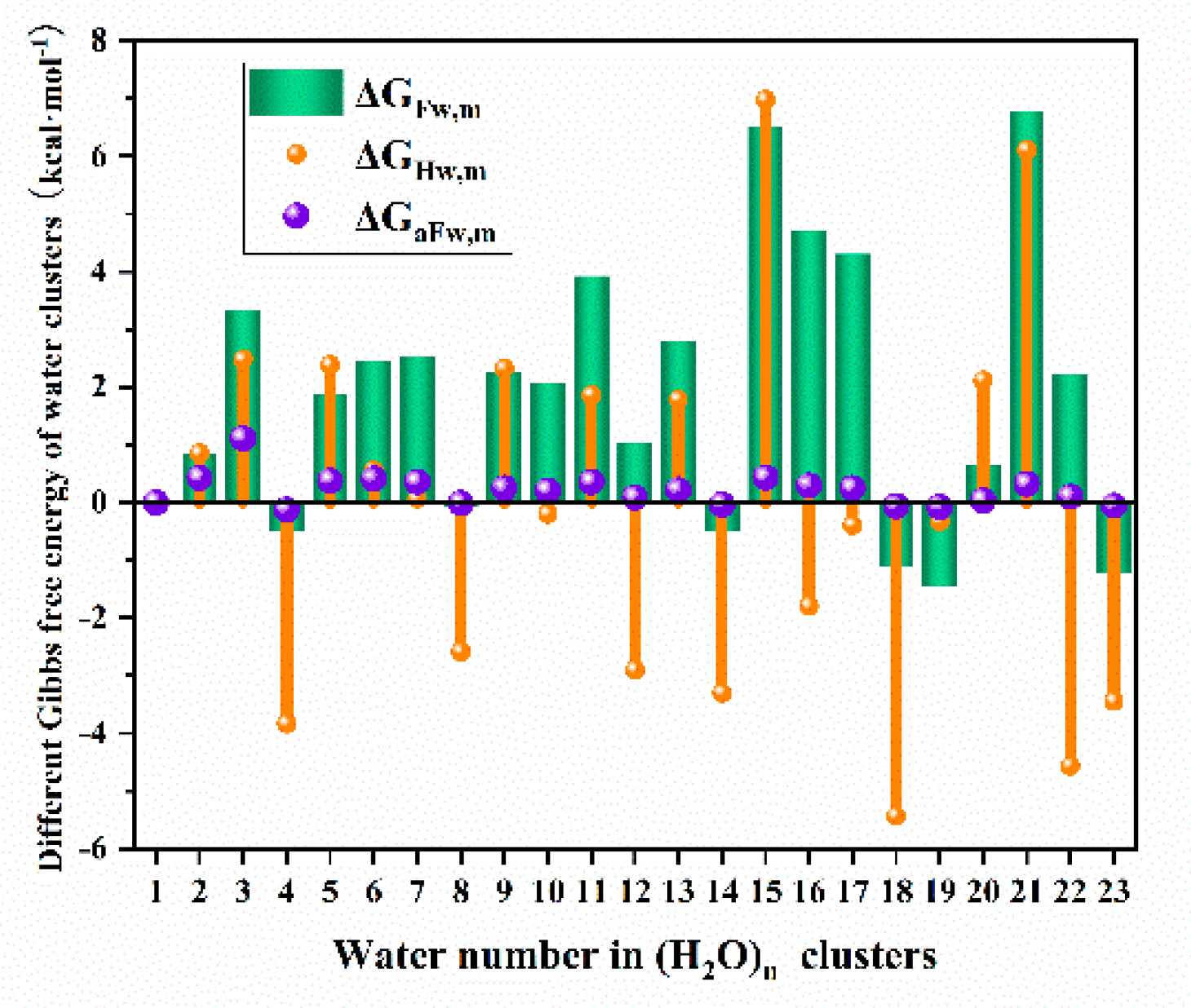

Figure 3.

From

Figure 3, it can be found that the clusters which have negative formation Gibbs free energy and can be formed thermodynamically were with a water number of 4, 8, 14, 18, 19 and 23, but none of the

were below -2 kcal·mol

-1. From the hydration Gibbs free energy analysis, we can see that the

of clusters with 4, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18, 19, 22 and 23 water all have negative value, meaning that these clusters are easily generated by the smaller clusters with one less water. This phenomenon was in consistence with fact in literature that the existence of

and

under very low temperatures were confirmed, demonstrating that these water clusters may not so much stable in room temperature when considering the thermodynamics, which can also be proved by the fact that the average Gibbs free energy

of all clusters near to be zero, that is to say the water will easily hydrate the ions becoming the hydration water but not to form the isolated water clusters in solution and the mono water may also be the main composition in liquid water considering the thermodynamics. Thus, for reasonable simplification, the water in solution will be treated as isolated molecule without the formation of clusters in our further investigation.

3.2. Solvation of Li+ and Mg2+ and Water Transfer Equilibrium

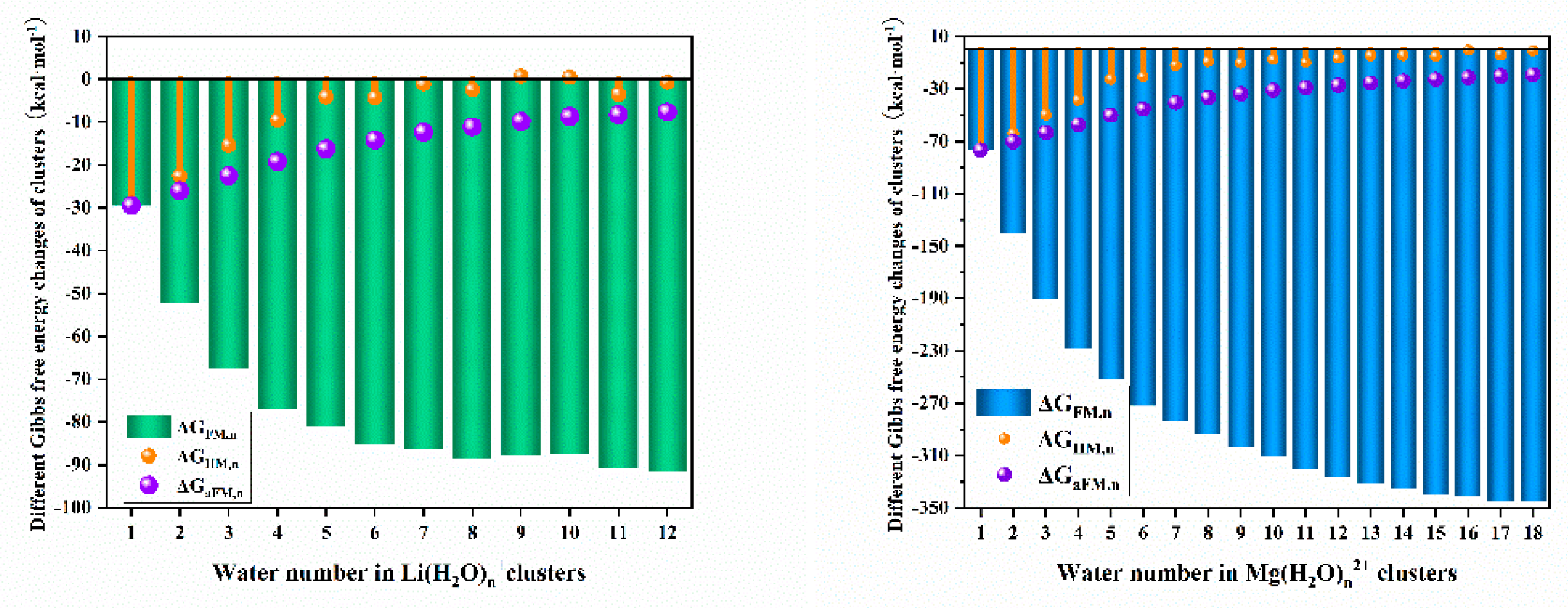

Following the above method, the Gibbs free energies respect with the water number in hydrated lithium and magnesium ions were calculated and demonstrated in

Figure 4. It can be found that the formation Gibbs free energy of

changed more than -5 kcal·mol

-1 compared to

when the water number is below 4 which is the saturation water number of the first hydration sphere of lithium. This means that the first hydration sphere has much stronger water-ion interaction than the water-water interaction in the second hydration sphere. By comparing the

of

and

, we can infer that the main particles should be much more

than water cluster in a lithium salt solution with a water/lithium molar ratio less than 12. And by comparing

, there should be much more

in the lithium solution than

. While by comparing the

of

and

, even the hydration number become 12, the

can always be better thermodynamically favored than water clusters, indicating that there is a big trend to form

but not the

.

Similar to , the clusters also showed that the water-ion interaction in the first hydration sphere is also much stronger than the water-water interaction in the second hydration sphere. Due to the higher charge, the magnesium hydration cluster has a much bigger than water cluster when the water number is not bigger than 15, and the value of the is larger than that of , indicating that the lithium hydration number may be only 4 when the water/magnesium molar ratio is less than 11, which is actually bigger than the ratio in the magnesium chloride solution with a concentration of 4.6 mol·L-1. This phenomenon pointed out that the normal assumption of magnesium with only six hydration water and lithium with four during the extraction of lithium in high magnesium brine is not suitable, and may cause overestimate of the extraction reaction Gibbs free energy change of magnesium. And by comparing of and , we can find that one water hydration can generate very close Gibbs energy change in and , meaning that the water hydration capability in is very close to that in in a solution with water/magnesium chloride mass ratio to be bigger than 3.43.

Overall, for both lithium - and magnesium - containing clusters, these ion - inclusive clusters exhibit notably higher formation and average formation Gibbs free energies. Additionally, within these clusters, the ion - water interactions in the first hydration sphere are significantly stronger than the water - water interactions in the second hydration sphere. The hydration states of ions vary depending on the metal’s charge and the number of hydration water molecules. Given these differences, a more in - depth study of the hydration equilibrium is warranted. Such an investigation holds the potential to enhance our understanding of the separation mechanism of lithium and magnesium in high - magnesium brine, providing crucial insights into the underlying processes governing their differentiation and extraction

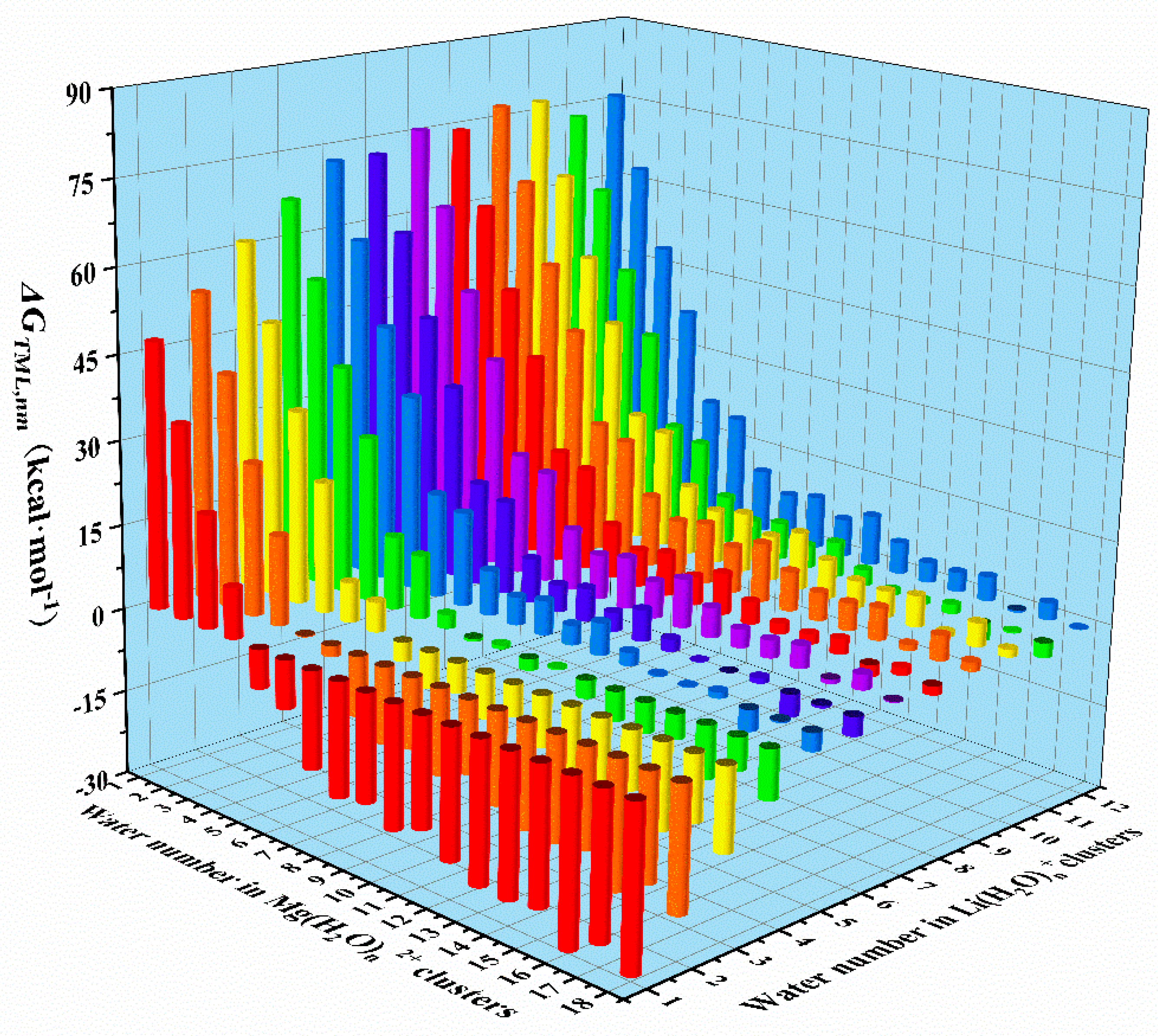

According to the Equation 5, the water transfer reaction Gibbs free energy changes were systemically calculated and showed in

Figure 5. The negative value of the

represents that the water transfer from

to

is thermodynamically favored or can spontaneously happen in room temperature, while the positive value means that the transfer cannot happen spontaneously. We can find that when the water number in

is less than 4, even the bare Li

+ ion cannot grab water from the magnesium-water clusters, and when the water number in

is greater than 6, even the

can grabbed the outer hydration water in

. When the water number is 5 in

,

can grabbed its outer hydration water, meaning that in a magnesium concentration of 4.6 mol·L

-1, the magnesium hydration number may be 10 with a lithium hydration number to be 4. This interaction is well consistent with the former comparison analysis between

and

. This equilibrium may not only be applied to discover the real state of metal ions, but also can be used to account for salting out effect for different ions.

3.3. Application of the Water Transfer Equilibrium in Lithium Extraction by TBP

From the above analysis, we can find that the hydration number of magnesium ion in the high magnesium solution with a concentration of 4.6 mol·L

-1 will be 10 and that of lithium ion is only 4, meaning that once the metal ions are extracted out of the aqueous solution, four more water would be released from the hydration sphere of the

comparing to the traditional structure

, while

would experience the same process as traditional theory, Thus the Gibbs free energy change difference

of

from

will be determined by the following Equation 6 and leave an impact on the extraction.

Then the can be calculated as 39.36 kcal·mol-1 for in the high magnesium solution. By substitute the Gibbs free energy with electron energy, the can be calculated as 55.09 kcal·mol-1 for .

This difference for the magnesium dehydration may cause magnesium extraction into organic phase much more difficult and realize the lithium and magnesium separation, and the real force of TBP extraction system for Li

+ separation from Mg

2+ may be discovered. The reaction shown as Equation 7 and Equation 8 summarized from reference 24 were the extraction reactions for lithium and magnesium by TBP-FeCl

3 in the high magnesium brines, and the Equation 8 should be corrected to Equation 9 according to above hypothesis. Then the calculated binding energy

and Gibbs free energy change

of the magnesium extraction reactions in literatures can be corrected by adding the relative value of Equation 6 and the results were listed in

Table 1. In order to make the comparison clear, the kJ·mol

-1 was applied as it in literature, and thus the correction should be converted to the same unit.

It can be found that the corrected was much smaller than that without considering the bigger hydration of magnesium and it then almost have a same value with lithium, indicating that the binding of magnesium and TBP is not much greater than that of lithium. When considering the thermodynamics, the of the magnesium extraction can be corrected by 164.77 kJ·mol-1, thus the become much bigger than the , determining a weak extraction of the magnesium comparing to lithium, which can well explain the separation of lithium from magnesium by TBP from the high magnesium solutions.

4. Conclusion

The clusters of , and were optimized at the wB97X - D4/def2 - TZVPPD theoretical level, followed by an analysis of the formation electron energy changes and various types of Gibbs free energies. Despite the diverse structures and formation electron energy changes exhibited by water clusters, the formation and hydration Gibbs free energies did not vary significantly with an increasing number of water molecules. Moreover, the theoretically predicted stable structures were in excellent agreement with experimental results. The study of lithium and magnesium clusters revealed that the ion - water interaction within the first hydration sphere is substantially stronger than the water - water interaction in the second hydration sphere. Based on the analysis of formation energy and the water molecule transfer equilibrium, the stable hydration states of ions in high - magnesium brine are proposed to be for lithium and for magnesium. The hypothesis of as the stable hydrated form of magnesium can effectively explain the separation of lithium from magnesium in high - magnesium bittern using the TBP extraction system, suggesting that the driving force for separation lies in the difference in the hydration of lithium and magnesium ions. The equilibrium method and the proposed hydrated ion hypothesis presented in this study not only contribute to a better understanding of the magnesium hydration state and the mechanism of lithium recovery through solvent extraction but also offer innovative perspectives for investigating various metal separation processes and salting - out effects.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U21A20305 ), Qinghai Provincial Department of science and Technology (2022-ZJ-728), Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (2021430). the Kunlun Talent Program of Qinghai Province (2022000092). We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jinfeng Li in regard to extractants.

References

- Bastos-González, D.; Pérez-Fuentes, L.; Drummond, C.; Faraudo, J. Ions at interfaces: the central role of hydration and hydrophobicity. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science 2016, 23, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Tan, T.; Yao, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, B.; Sun, C. Q. Molecular hydration: Interfacial supersolidity and its functionality. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 501, 215576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Föste, M.; Verheyen, C.; Jekle, M.; Becker, T. Fibres of milling and fruit processing by-products in gluten-free bread making: A review of hydration properties, dough formation and quality-improving strategies. Food Chemistry 2020, 306, 125451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerch, G. Polymer hydration and stiffness at biointerfaces and related cellular processes. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine 2018, 14, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Neu, M. P.; Garcia, E.; Morales, L. A. Hydration of plutonium oxide and process salts, NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, MgCl2: effect of calcination on residual water and rehydration. Waste Management 2000, 20, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K. D. Ion hydration: Implications for cellular function, polyelectrolytes, and protein crystallization. Biophysical Chemistry 2006, 119, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, P. R. Structural Parameters of the Nearest Environment of Zinc, Cadmium, and Mercury Ions in Aqueous Solutions of Their Salts (A Review). Russian Journal of General Chemistry 2024, 94, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariev, A. M.; Green, M. E. Water, Protons, and the Gating of Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels. Membranes 2024, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, Q.; Han, B.; Zhou, C. Mechanism of lithium ion selectivity through membranes: a brief review. Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2024, 10, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Su, D.; Miao, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y.; Leng, K.; Yu, Y. Separation and concentration of phospholipids and glycerides from ethanol extraction of krill by hydration and solvent partitioning. Separation and Purification Technology 2023, 317, 123900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareček, V. Electrochemical monitoring of the co-extraction of water with hydrated ions into an organic solvent. Electrochemistry Communications 2018, 88, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, Y.; Fujihara, R.; Katsuta, S.; Takeda, Y. Hydration Effect on the Ion-pair Extraction of Lithium Picrate by Hydrophobic Benzo-15-crown-5 Ether into Various Less-polar Diluents. Analytical Sciences 2007, 23, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernova, R. K. Hydration–Solvation Mechanism in Micellar Extraction. Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2003, 58, 628–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramov, A. A.; Dzhigirkhanov, M. S. A.; Iofa, B. Z.; Volkova, S. V. Hydration and Extraction of Oxyanions. Radiochemistry 2002, 44, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, T.; Lv, S.; Song, S.; Galván, H. J. O.; Quintana, M.; Zhao, Y. Adsorbents for lithium extraction from salt lake brine with high magnesium/lithium ratio: From structure-performance relationship to industrial applications. Desalination 2024, 579, 117480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-n.; Yu, D.-h.; Jia, C.-y.; Sun, L.-y.; Tong, A.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.-x.; Huang, L.-j.; Tang, J.-g. Advances and promotion strategies of membrane-based methods for extracting lithium from brine. Desalination 2023, 566, 116891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojid, M. R.; Lee, K. J.; You, J. A review on advances in direct lithium extraction from continental brines: Ion-sieve adsorption and electrochemical methods for varied Mg/Li ratios. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2024, 40, e00923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamina, B. Extraction of Cobalt and Lithium from Sulfate Solution Using Di(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric Acid/Kerosene Mixed Extractant. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2020, 94, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagasundaram, T.; Murphy, O.; Haji, M. N.; Wilson, J. J. The recovery and separation of lithium by using solvent extraction methods. Coordination Chemistry Reviews 2024, 509, 215727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, R.; Ren, Z.; Zhou, Z. Selective extraction of lithium from high magnesium/lithium ratio brines with a TBP–FeCl3–P204–kerosene extraction system. Separation and Purification Technology 2024, 328, 125066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, D.; Cui, J.; Zhang, Y. Recovery of lithium from high Mg/Li ratio salt-lake brines using ion-exchange with NaNTf2 and TBP. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 213, 105914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, L.; zhu, L. Solvent extraction of lithium from hydrochloric acid leaching solution of high-alumina coal fly ash. Chemical Physics Letters 2021, 771, 138510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Su, H.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, M.; Qi, T. Mechanisms for the separation of Li+ and Mg2+ from salt lake brines using TBP and TOP systems. Desalination 2024, 583, 117698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Chen, H.; Yu, J. Investigation on the Lithium Extraction Process with the TBP–FeCl3 Solvent System Using Experimental and DFT Methods. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2022, 61, 4672–4682. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, H.; Truong, T. N. A coupled RISM/MD or MC simulation methodology for solvation free energies. Chemical Physics Letters 2003, 381, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; E, J. Exploring detailed microcosmic mechanisms of sodium chloride deposition in supercritical water reactors from the aspect of solvation structure: A combination of MD and QM simulations. Journal of Molecular Liquids 2023, 383, 122118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, G.; Haseena, S.; Vennila, P.; Sixto-López, Y.; Siva, V.; Mishma, J. N. C.; Azad, S. A. K.; Mary, Y. S. Solvation effects, structural, vibrational analysis, chemical reactivity, nanocages, ELF, LOL, docking and MD simulation on Sitagliptin. Chemical Physics Impact 2024, 8, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinvald, I. I.; Kapustin, R. V.; Agrba, A. I.; Agrba, M. D. DFT Simulation of Cluster Structures in Organic Systems. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2023, 97, 2749–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandurist, P. S.; Pichugina, D. A.; Kuzmenko, N. E. Studying the Effect of Doping Au20(SR)16 Cluster with Copper and Silver in the Activation of CO and O2, Based on DFT Data. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2022, 96, 1715–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuz’mina, I. A.; Kovanova, M. A.; Perova, S. O. Calculating the Gibbs Energy of Solvation of Pyridine in Nonaqueous Solvents. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2023, 97, 1620–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bespalov, D. V.; Golovanova, O. A. Magnesium Glycinate and Tyrosinate: Structure Calculations and IR Spectra by the DFT Method. Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2024, 98, 1380–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, M. J.; Alfè, D.; Michaelides, A. Perspective: How good is DFT for water? The Journal of Chemical Physics 2016, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Grávalos, F.; Casals-Sainz, J. L.; Francisco, E.; Rocha-Rinza, T.; Martín Pendás, Á.; Guevara-Vela, J. M. DFT performance in the IQA energy partition of small water clusters. Theoretical Chemistry Accounts 2019, 139, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xantheas, S. S.; Dunning, T. H., Jr. The structure of the water trimer from ab initio calculations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1993, 98, 8037–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.; Laria, D.; Marceca, E. J.; Estrin, D. o. A. Isomerization, melting, and polarity of model water clusters: (H2O)6 and (H2O)8. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1999, 110, 9039–9047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L. X. Characterization of water octamer, nanomer, decamer, and iodide–water interactions using molecular dynamics techniques. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1999, 110, 1526–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansini, F. N. N.; Varandas, A. J. C. On the solvation model and infrared spectroscopy of liquid water. Chemical Physics Letters 2022, 801, 139739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, P. C.; Satorre Aznar, M. Á.; Escribano, R. Density and porosity of amorphous water ice by DFT methods. Chemical Physics Letters 2020, 745, 137222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanourgakis, G. S.; Aprà, E.; Xantheas, S. S. High-level ab initio calculations for the four low-lying families of minima of (H2O)20. I. Estimates of MP2/CBS binding energies and comparison with empirical potentials. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2004, 121, 2655–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xantheas, S. S. Ab initio studies of cyclic water clusters (H2O)n, n=1–6. III. Comparison of density functional with MP2 results. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1995, 102, 4505–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsányi, I.; Pusztai, L. Hydration structure in concentrated aqueous lithium chloride solutions: A reverse Monte Carlo based combination of molecular dynamics simulations and diffraction data. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2012, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tromp, R. H.; Neilson, G. W.; Soper, A. K. Water structure in concentrated lithium chloride solutions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1992, 96, 8460–8469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, K. M.; Casillas-Ituarte, N. N.; Roeselová, M.; Allen, H. C.; Tobias, D. J. Solvation of Magnesium Dication: Molecular Dynamics Simulation and Vibrational Spectroscopic Study of Magnesium Chloride in Aqueous Solutions. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 2010, 114, 5141–5148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnov, P. R.; Trostin, V. N. Structural parameters of hydration of Be2+ and Mg2+ ions in aqueous solutions of their salts. Russian Journal of General Chemistry 2008, 78, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, J. N. X-Ray Diffraction Studies of Aqueous Alkaline-Earth Chloride Solutions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1972, 56, 3783–3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Y.; Zhou, Y. Q.; Zhu, F. Y.; Zhang, W. Q.; Wang, G. G.; Jing, Z. F.; Fang, C. H. Micro hydration structure of aqueous Li+ by DFT and CPMD. The European Physical Journal D 2020, 74, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrian-Scotto, M.; Mallet, G.; Vasilescu, D. Hydration of Mg++: a quantum DFT and ab initio HF study. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 2005, 728, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najibi, A.; Goerigk, L. DFT-D4 counterparts of leading meta-generalized-gradient approximation and hybrid density functionals for energetics and geometries. Journal of Computational Chemistry 2020, 41, 2562–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeweyher, E.; Ehlert, S.; Hansen, A.; Neugebauer, H.; Spicher, S.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S. A generally applicable atomic-charge dependent London dispersion correction. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2019, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappoport, D.; Furche, F. Property-optimized Gaussian basis sets for molecular response calculations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2010, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigend, F. Accurate Coulomb-fitting basis sets for H to Rn. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2006, 8, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weigend, F.; Ahlrichs, R. Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldeweyher, E.; Bannwarth, C.; Grimme, S. Extension of the D3 dispersion coefficient model. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2017, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Systematic optimization of long-range corrected hybrid density functionals. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2008, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neese, F. Software update: The ORCA program system-Version 5.0. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 2022, 12, e1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.; Jordan, K.D. Monte Carlo simulation of (H2O)8: Evidence for a low-energy S4 structure and characterization of the solid ↔ liquid transition. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1991, 95, 3850–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).