Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

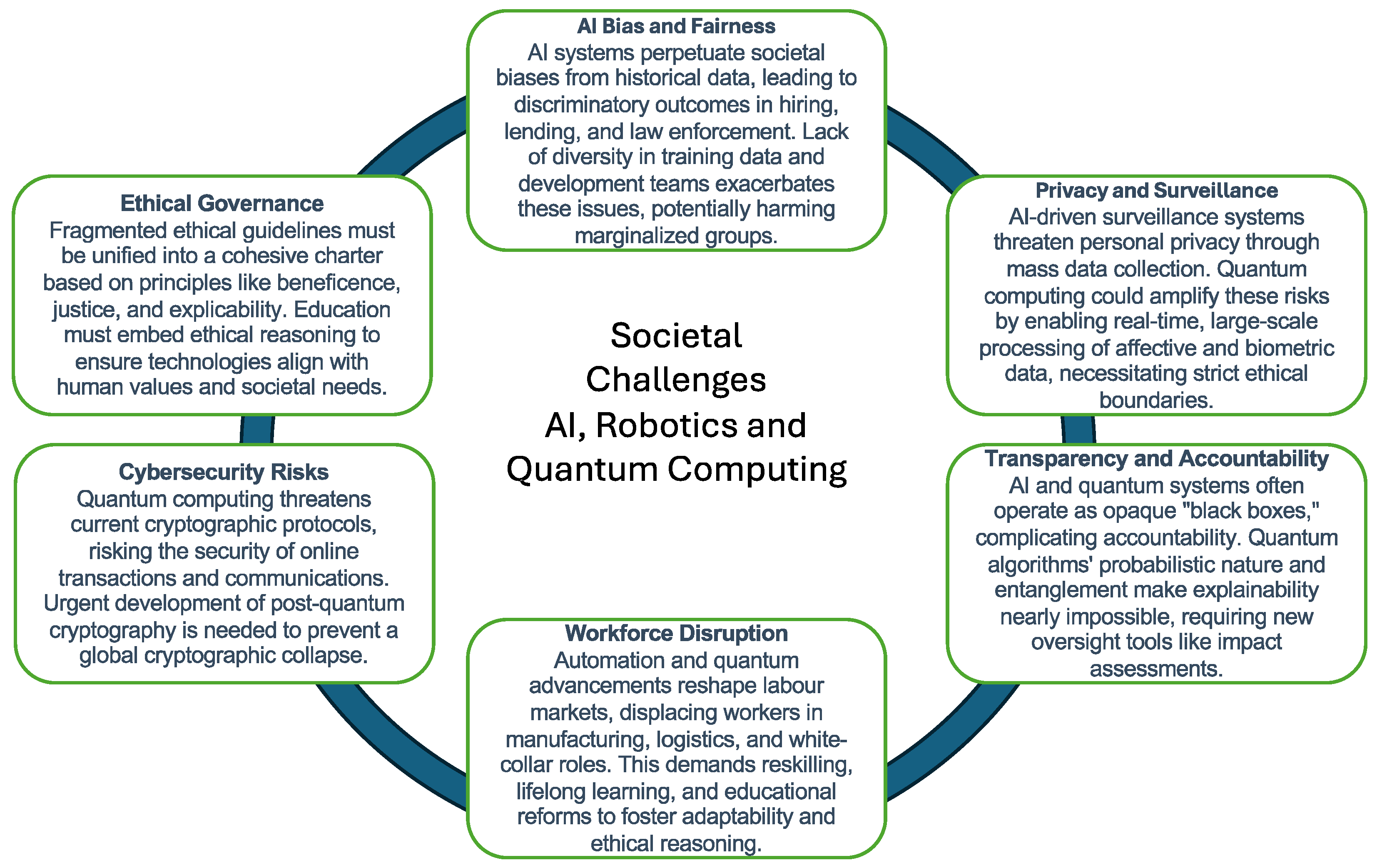

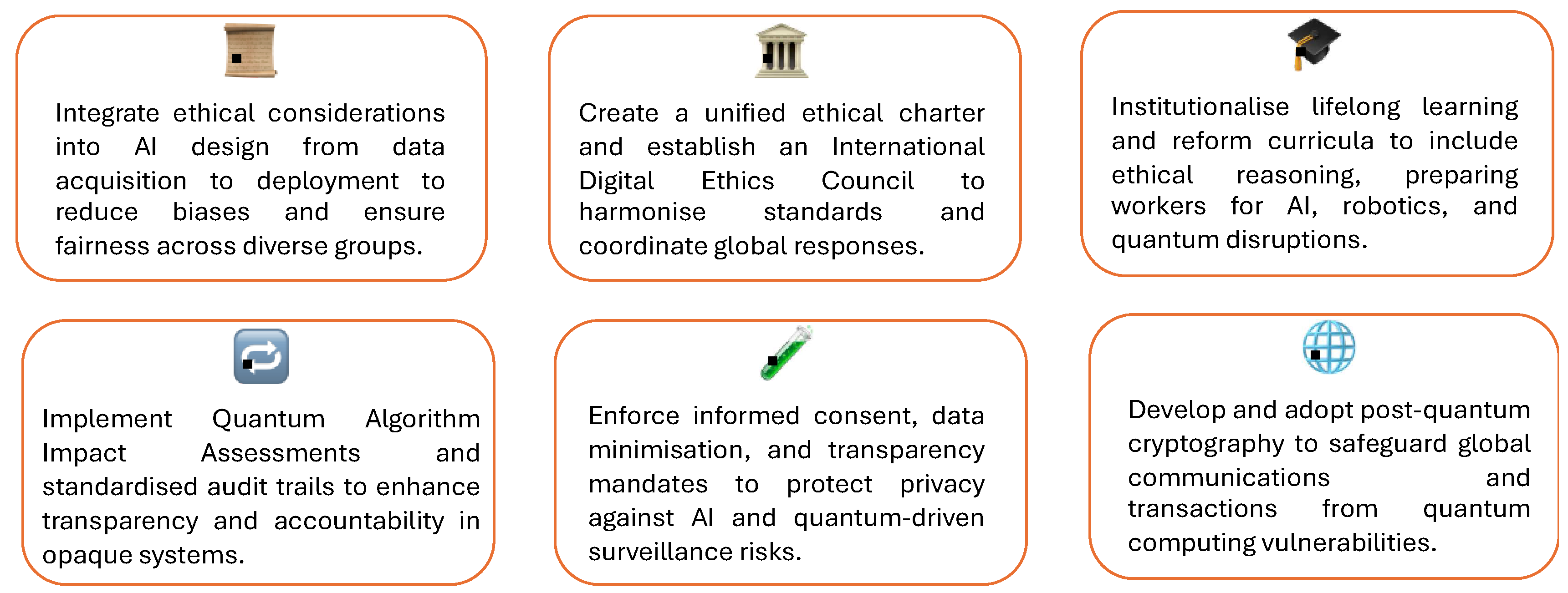

2. Ethical and Social Concerns in AI and Robotics

3. Quantum Computing and Its Emerging Ethical Challenges

4. Implications for Education and Workforce Development

5. Discussion: Reframing Ethics for Convergent Technologies

5.1. From Fragmentation to Cohesion: Rethinking Ethical Guidelines

5.2. The Limits of Explainability in AI and Quantum Systems

5.3. Accountability in the Quantum Age

5.4. Surveillance and Affective Data: Ethical Red Lines

5.5. Education as Infrastructure for Ethical Governance

6. Theoretical Foundations for Ethical Analysis

7. Methodology

8. Policy Implications

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mehrabi, N.; Morstatter, F.; Saxena, N.; Lerman, K.; Galstyan, A. A Survey on Bias and Fairness in Machine Learning. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, S.; Bonchi, F.; Castillo, C. Algorithmic Bias. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 2125–2126. [Google Scholar]

- Shoshana Zuboff The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power - Book - Faculty & Research - Harvard Business School. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=56791 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Bernstein, D.J.; Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography. Nat. 2017 5497671 2017, 549, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrell, J. How the machine ‘thinks’: Understanding opacity in machine learning algorithms. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathaee, Y. The Artificial Intelligence Black Box and the Failure of Intent and Causation. Harvard J. Law \& Technol. 2018, 31, 889. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, P.; Wagner, M. Autonomous Vehicle Safety: An Interdisciplinary Challenge. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2017, 9, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S.; Cotton, T.; Brundage, M.; Avin, S.; Clark, J.; Toner, H.; Eckersley, P.; Garfinkel, B.; Dafoe, A.; Scharre, P.; et al. The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Petruccione, F. Supervised Learning with Quantum Computers. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.B.; Osborne, M.A. The future of employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemuri, V.K. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies, by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee. J. Inf. Technol. Case Appl. Res. 2014, 16, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Restrepo, P. Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets. Journal of Political Economy 2020, 128, 2188–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Employment Outlook 2019. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Futures of Education: learning to become - UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370801 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Cox, A.M. Exploring the impact of Artificial Intelligence and robots on higher education through literature-based design fictions. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- authorCorporate:UNESCO Futures of Education: learning to become. 2019. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000370801 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- The Future of Jobs; Davos, 2016. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Ethics guidelines for trustworthy AI | Shaping Europe’s digital future. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Mittelstadt, B.D.; Allo, P.; Taddeo, M.; Wachter, S.; Floridi, L. The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A.; Ienca, M.; Vayena, E. The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019 19 2019, 1, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arute, F.; Arya, K.; Babbush, R.; Bacon, D.; Bardin, J.C.; Barends, R.; Biswas, R.; Boixo, S.; Brandao, F.G.S.L.; Buell, D.A.; et al. Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor. Nat. 2019 5747779 2019, 574, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L.; Cowls, J. A Unified Framework of Five Principles for AI in Society. Harvard Data Sci. Rev. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography---dealing with the fallout of physics success. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2017. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2017/314 (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Luis-Ferreira, F.; Jardim-Goncalves, R. A behavioral framework for capturing emotional information in an internet of things environment. AIP Conf. Proc. 2013, 1558, 1368–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis-Ferreira, F.; Jardim-Goncalves, R. Internet of Persons and Things inspired on Brain Models and Neurophysiology. Comput. Methods Soc. Sci. 2013, 1, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Westra, J.; Hasselt, H. Van; Dignum, V.; Dignum, F. On-line adapting games using agent organizations. 2008 IEEE Symp. Comput. Intell. Games, CIG 2008 2008, 243–250. [CrossRef]

- Make quantum readiness real | IBM. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/thought-leadership/institute-business-value/en-us/report/quantum-readiness (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Biamonte, J.; Wittek, P.; Pancotti, N.; Rebentrost, P.; Wiebe, N.; Lloyd, S. Quantum machine learning. Nature 2017, 549, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuld, M.; Killoran, N. Quantum Machine Learning in Feature Hilbert Spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 040504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosinski, M.; Stillwell, D.; Graepel, T. Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110, 5802–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.A.; D’Mello, S. Affect Detection: An Interdisciplinary Review of Models, Methods, and Their Applications. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2010, 1, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guston, D.H.; Sarewitz, D. Real-time technology assessment. Technol. Soc. 2002, 24, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krafft, P.M.; Young, M.; Kominers, S.D. The ethics of algorithms: Mapping the debate. Big Data \& Soc. 2020, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).