This section describes the architectural and implementation details of TBMQ, the configuration and optimization of the persistence layer, and the experimental environment used to evaluate the system’s performance.

2.1. Architecture and Implementation Details

While the TBMQ 1.x version can 100 million clients [

28] at once and 3 million msg/s [

29], as a high-performance MQTT broker it was primarily designed to aggregate data from IoT devices and deliver it to back-end applications reliably (QoS 1). This architecture is based on operational experience accumulated by the TBMQ development team through IIoT and other large-scale IoT deployments, where millions of devices transmit data to a limited number of applications.

These deployments highlighted that IoT devices and applications follow distinct communication patterns. IoT devices or sensors publish data frequently but subscribe to relatively few topics or updates. In contrast, applications subscribe to data from tens or even hundreds of thousands of devices and require reliable message delivery. Additionally, applications often experience periods of downtime due to system maintenance, upgrades, failover scenarios, or temporary network disruptions.

To address these differences, TBMQ introduces a key feature: the classification of MQTT clients as either standard (IoT devices) or application clients. This distinction enables optimized handling of persistent MQTT sessions for applications. Specifically, each persistent application client is assigned a separate Kafka topic. This approach ensures efficient message persistence and retrieval when an MQTT client reconnects, improving overall reliability and performance. Additionally, application clients support MQTT’s shared subscription feature, allowing multiple instances of an application to efficiently distribute message processing.

Kafka [

30] serves as one of the core components. Designed for high-throughput, distributed messaging, Kafka efficiently handles large volumes of data streams, making it an ideal choice for TBMQ [

31]. With the latest Kafka versions capable of managing a huge number of topics, this architecture is well-suited for enterprise-scale deployments. Kafka’s robustness and scalability have been validated across diverse applications, including real-time data streaming and smart industrial environments [

31,

32,

33].

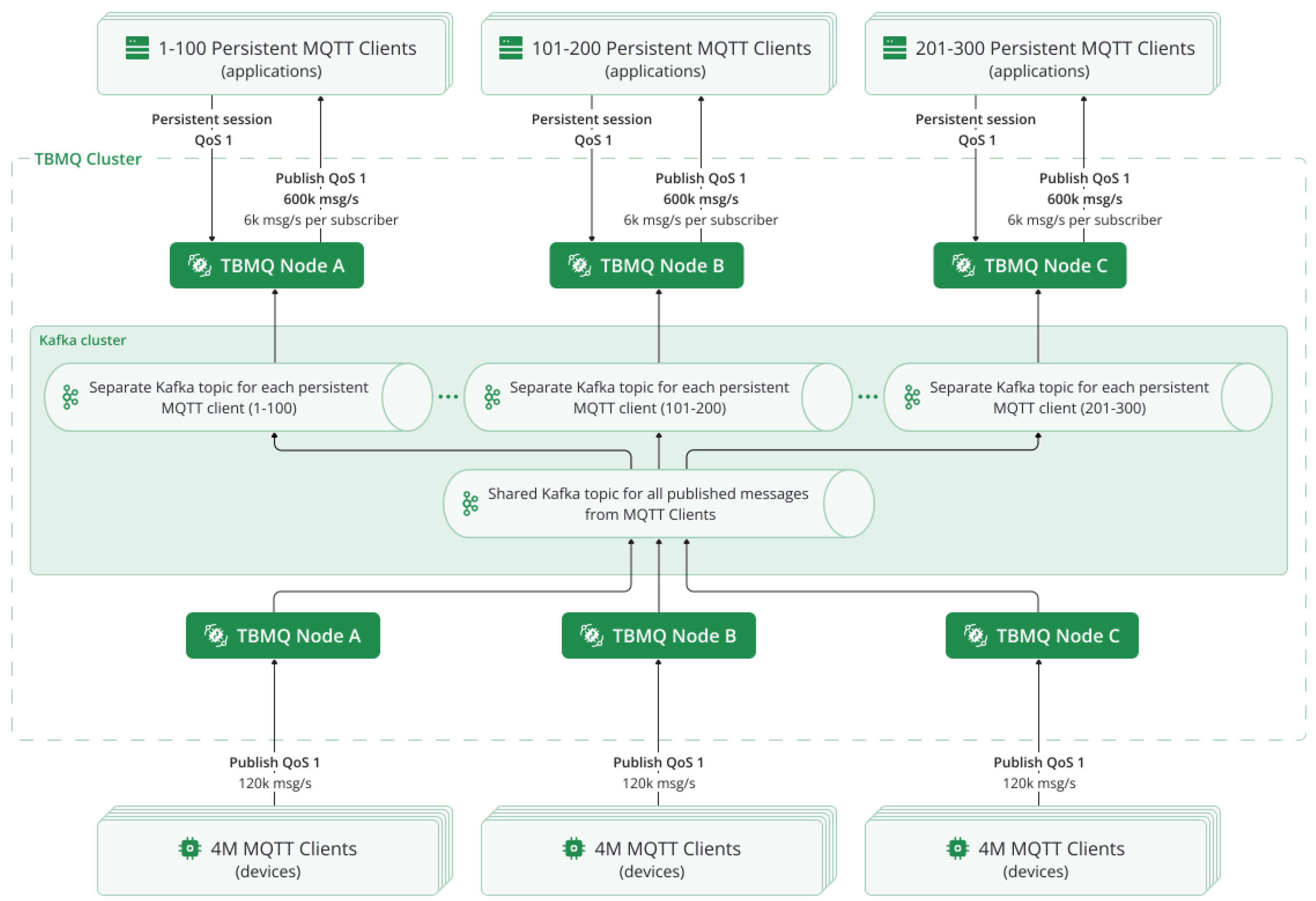

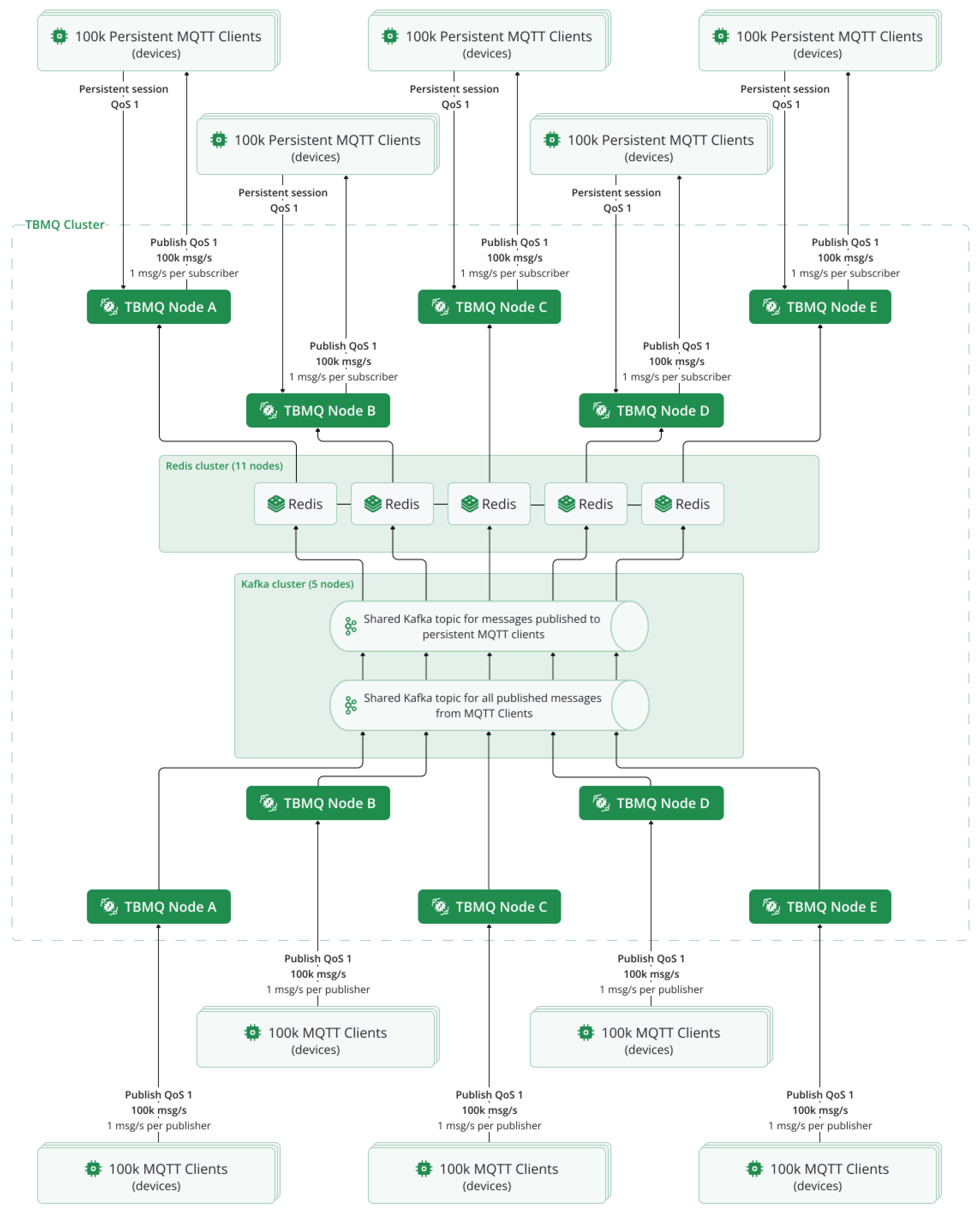

Figure 1 illustrates the full fan-in setup in a distributed TBMQ cluster.

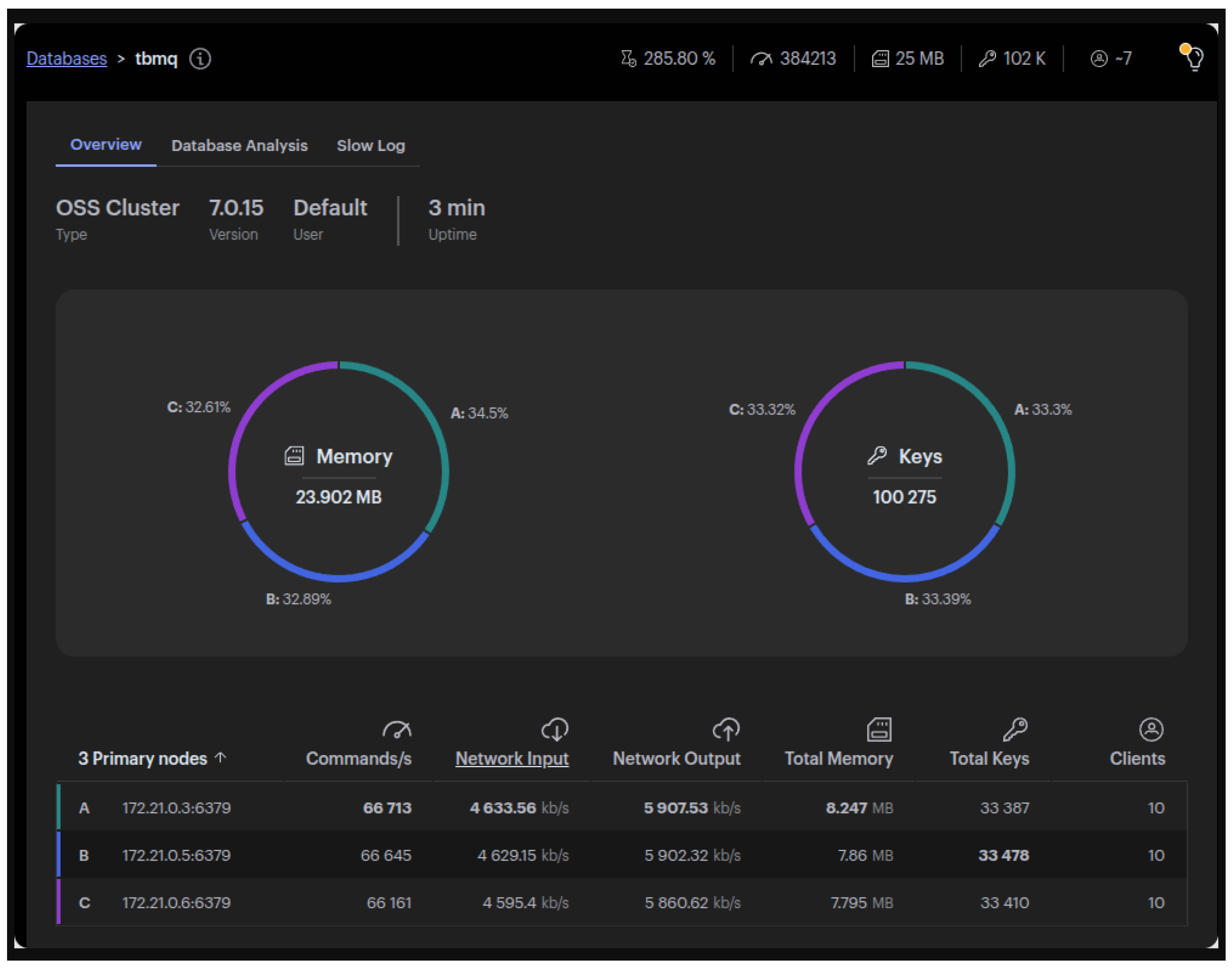

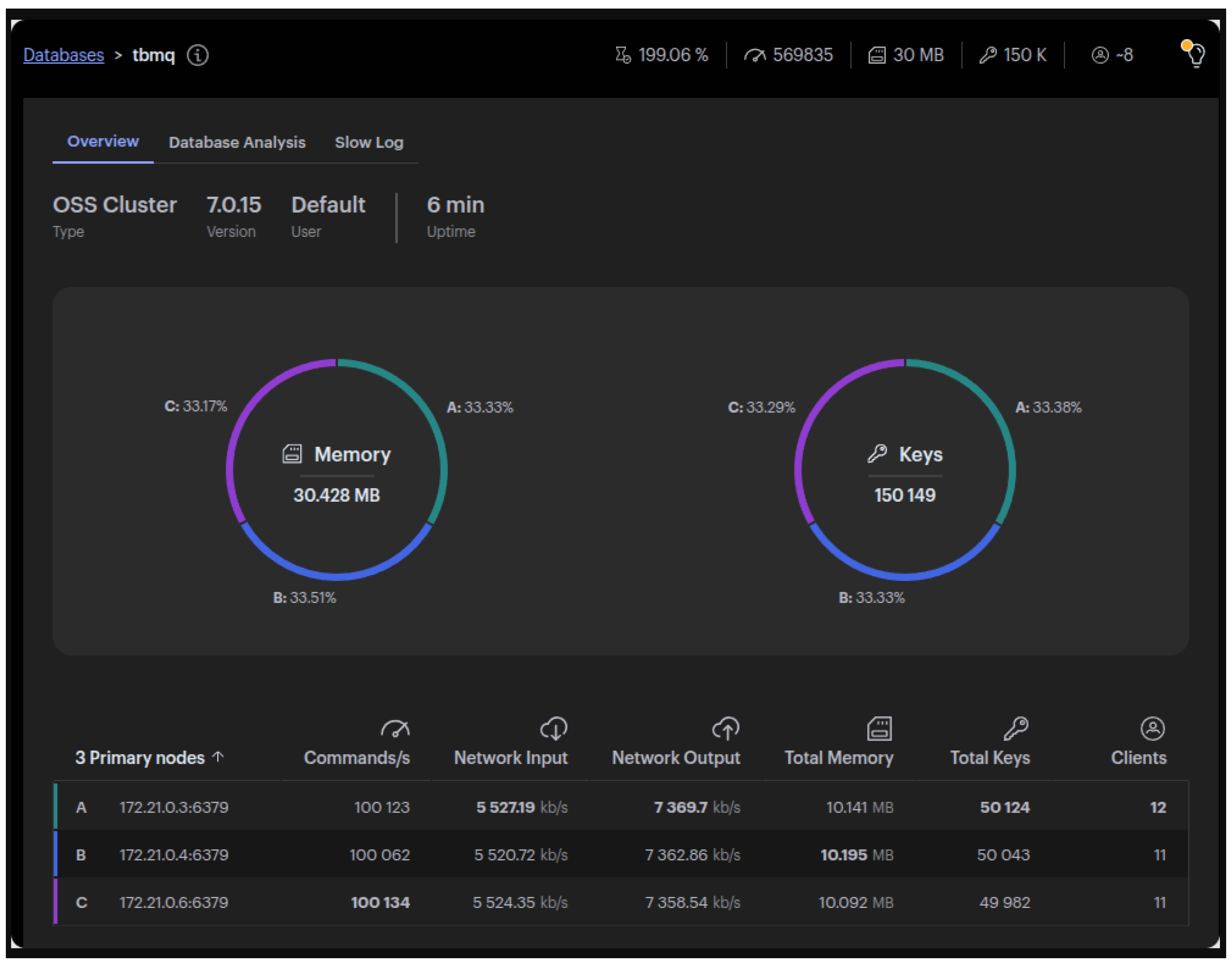

In TBMQ 1.x, standard MQTT clients relied on PostgreSQL for message persistence and retrieval, ensuring that messages were delivered when a client reconnected. While PostgreSQL performed well initially, it had a fundamental limitation—it could only scale vertically. It was anticipated that, as the number of persistent MQTT sessions grew, PostgreSQL’s architecture would eventually become a bottleneck. To address these scalability limitations, more robust alternatives were investigated to meet the increasing performance demands of TBMQ. Redis was quickly chosen as the best fit due to its horizontal scalability, native clustering support, and widespread adoption.

Unlike the fan-in, the point-to-point (P2P) communication pattern enables direct message exchange between MQTT clients. Typically implemented using uniquely defined topics, P2P is well-suited for private messaging, device-to-device communication, command transmission, and other direct interaction use cases.

One of the key differences between fan-in and peer-to-peer MQTT messaging is the volume and flow of messages. In a P2P scenario, subscribers do not handle high message volumes, making it unnecessary to allocate dedicated Kafka topics and consumer threads to each MQTT client. Instead, the primary requirements for P2P message exchange are low latency and reliable message delivery, even for clients that may go offline temporarily. To meet these needs, TBMQ optimizes persistent session management for standard MQTT clients, which include IoT devices.

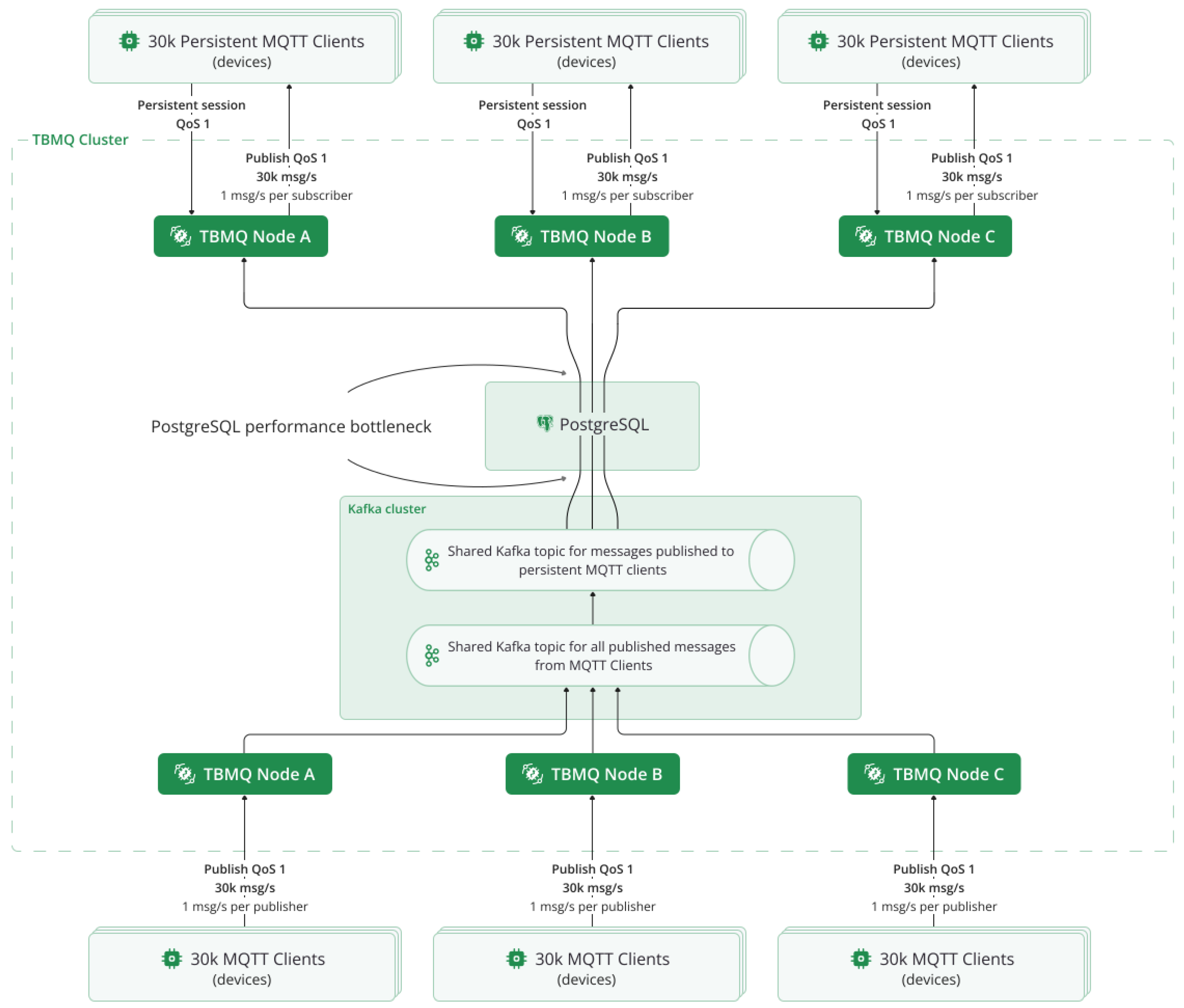

Figure 2 shows how standard MQTT clients publish and receive direct messages via TBMQ, while Redis supports session persistence and Kafka facilitates routing.

2.2. PostgreSQL Usage and Limitations

To fully understand the reasoning behind this shift, it’s important to first examine how MQTT clients operated within the PostgreSQL architecture. This architecture was built around two key tables.

The device_session_ctx was responsible for maintaining the session state of each persistent MQTT client:

Table "public.device_session_ctx"

Column | Type | Nullable

------------------+-----------------------+----------

client_id | character varying(255)| not null

last_updated_time | bigint | not null

last_serial_number| bigint |

last_packet_id | integer |

Indexes:

"device_session_ctx_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (client_id)

The key columns are last_packet_id and last_serial_number, which is used to maintain message order for persistent MQTT clients:

last_packet_id represents the packet ID of the last MQTT message received.

last_serial_number acts as a continuously increasing counter, preventing message order issues when the MQTT packet ID wraps around after reaching its limit of 65535.

The device_publish_msg table was responsible for storing messages that must be published to persistent MQTT clients (subscribers).

Table "public.device_publish_msg"

Column | Type | Nullable

------------------------+-----------------------+----------

client_id | character varying(255)| not null

serial_number | bigint | not null

topic | character varying | not null

time | bigint | not null

packet_id | integer |

packet_type | character varying(255)|

qos | integer | not null

payload | bytea | not null

user_properties | character varying |

retain | boolean |

msg_expiry_interval | integer |

payload_format_indicator| integer |

content_type | character varying(255)|

response_topic | character varying(255)|

correlation_data | bytea |

Indexes:

"device_publish_msg_pkey" PRIMARY KEY, btree (client_id, serial_number)

"idx_device_publish_msg_packet_id" btree (client_id, packet_id)

The key columns to highlight:

time – captures the system time (timestamp) when the message is stored. This field is used for periodic cleanup of expired messages.

msg_expiry_interval – represents the expiration time (in seconds) for a message. This is set only for incoming MQTT 5 messages that include an expiry property. If the expiry property is absent, the message does not have a specific expiration time and remains valid until it is removed by time or size-based cleanup.

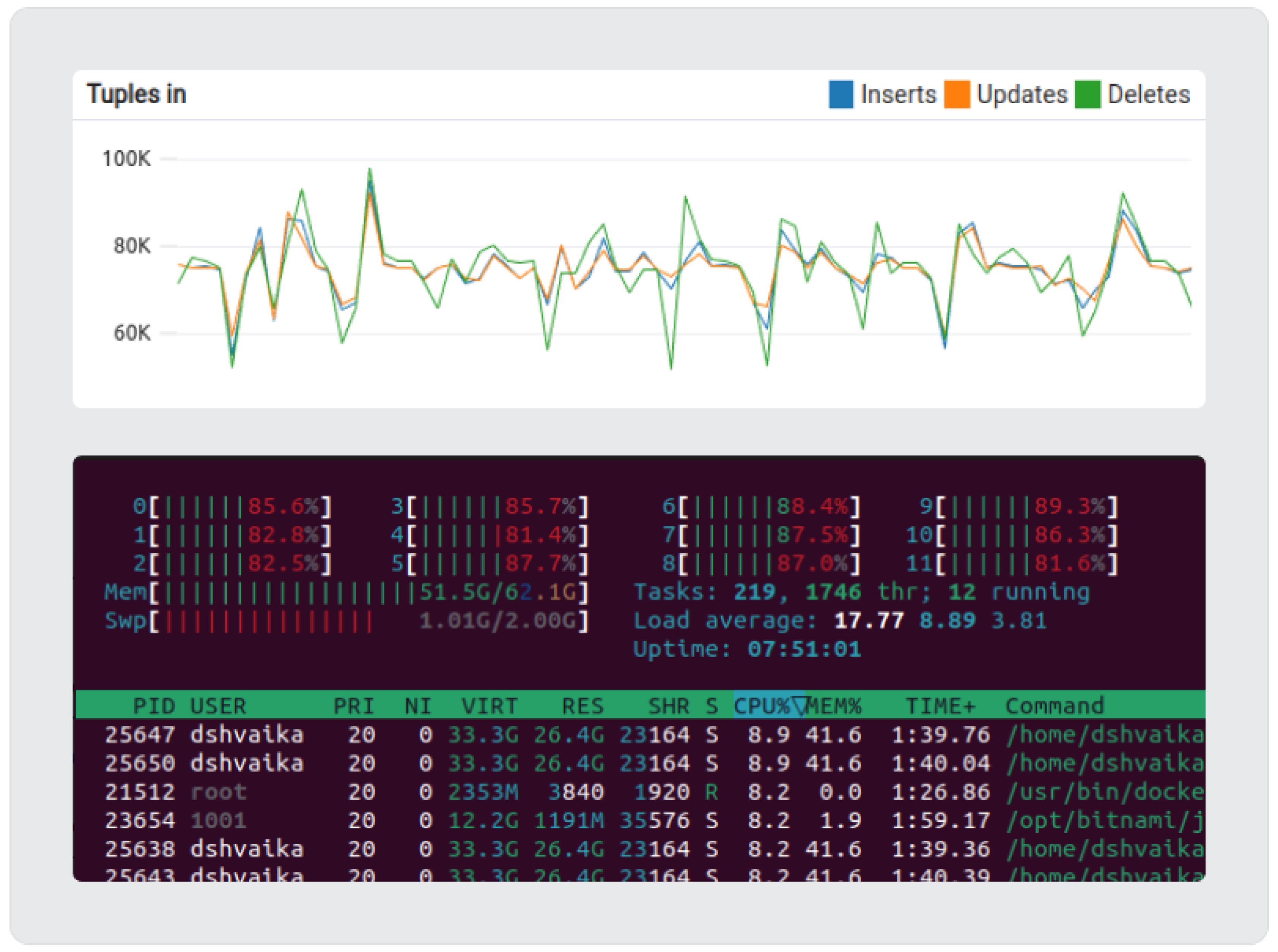

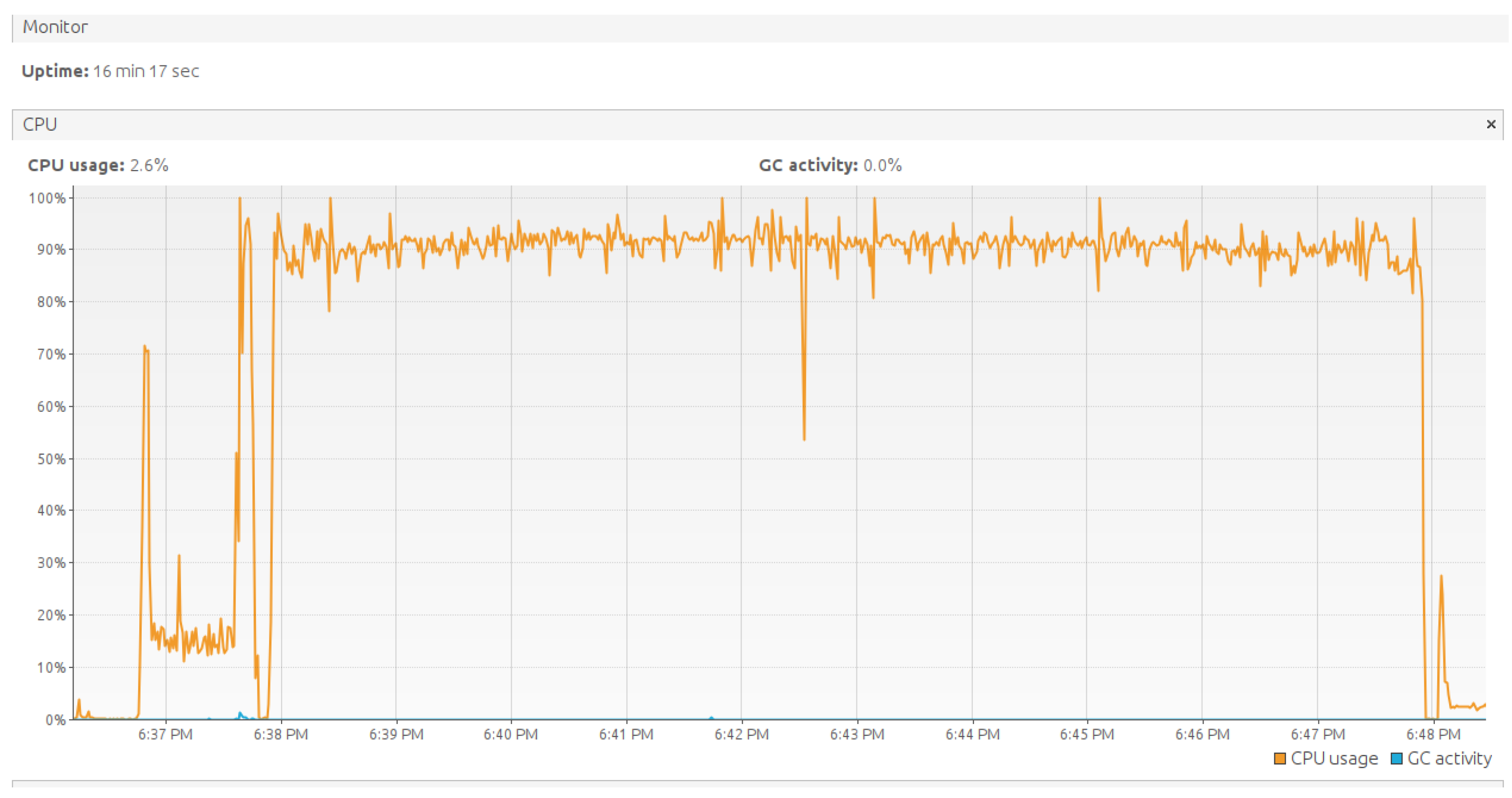

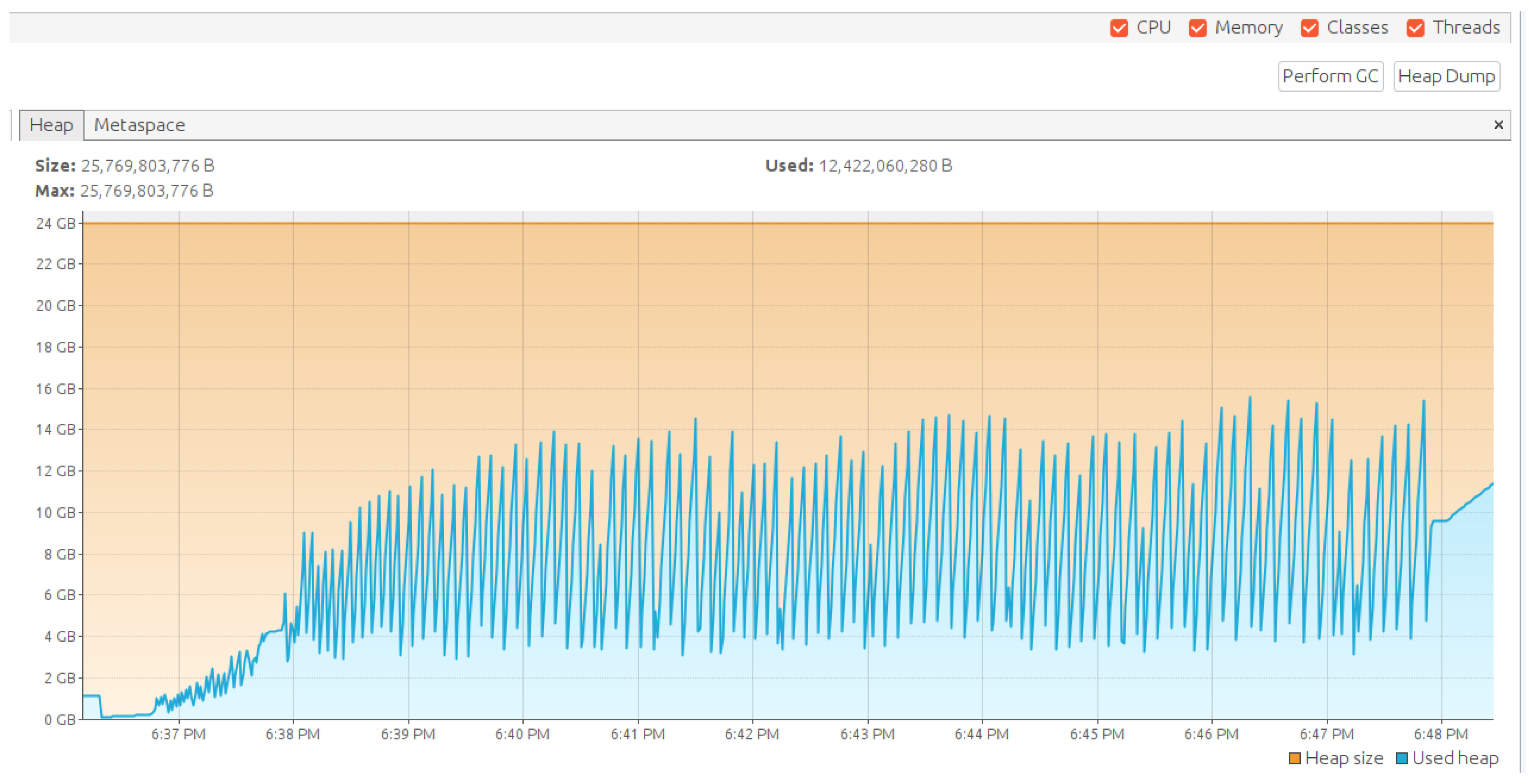

While this design ensured reliable message delivery, it also introduced performance constraints. To better understand its limitations, prototype testing was performed to evaluate PostgreSQL’s performance under the P2P communication pattern. Using a single instance with 64GB RAM and 12 CPU cores, message loads were simulated with a dedicated performance testing tool [

34] capable of generating MQTT clients and simulating the desired message load. The primary performance metric was the average message processing latency, measured from the moment the message was published to the point it was acknowledged by the subscriber. The test was considered successful only if there was no performance degradation, meaning the broker consistently maintained an average latency in the two-digit millisecond range.

Prototype testing ultimately revealed a throughput limit of 30k msg/s when using PostgreSQL for persistent message storage. Throughput refers to the total number of msg/s, including both incoming and outgoing messages,

Figure 3.

Based on the TimescaleDB blog post [

35], vanilla PostgreSQL can handle up to 300k inserts per second under ideal conditions. However, this performance depends on factors such as hardware, workload, and table schema. While vertical scaling can provide some improvement, PostgreSQL’s per-table insert throughput eventually reaches a hard limit. This experiment confirmed a fundamental scalability limit inherent to PostgreSQL’s vertically scaled architecture. Although PostgreSQL has demonstrated strong performance in benchmark studies under concurrent read-write conditions [

36], and has been used in large-scale industrial systems handling hundreds of thousands of transactions per second [

37], its architecture is primarily optimized for single-node operation and lacks built-in horizontal scaling. As the number of persistent sessions in TBMQ deployments scaled into the millions, this model created a bottleneck. Confident in Redis’s ability to overcome this bottleneck, the migration process was initiated to achieve greater scalability and efficiency. The migration process began with an evaluation of Redis data structures that could replicate the essential logic implemented with PostgreSQL.

2.3. Redis as a Scalable Alternative

The decision to migrate to Redis was driven by its ability to address the core performance bottlenecks encountered with PostgreSQL. Unlike PostgreSQL, which relies on disk-based storage and vertical scaling, Redis operates primarily in memory, significantly reducing read and write latency. Additionally, Redis’s distributed architecture enables horizontal scaling, making it an ideal fit for high-throughput messaging in P2P communication scenarios [

38]. Recent studies demonstrate the successful application of Redis in cloud and IoT scenarios, including enhancements through asynchronous I/O frameworks such as io_uring to further boost throughput under demanding conditions [

39]. In addition, migration pipelines from traditional relational databases to Redis have been validated as efficient strategies for improving system responsiveness and scalability [

40].

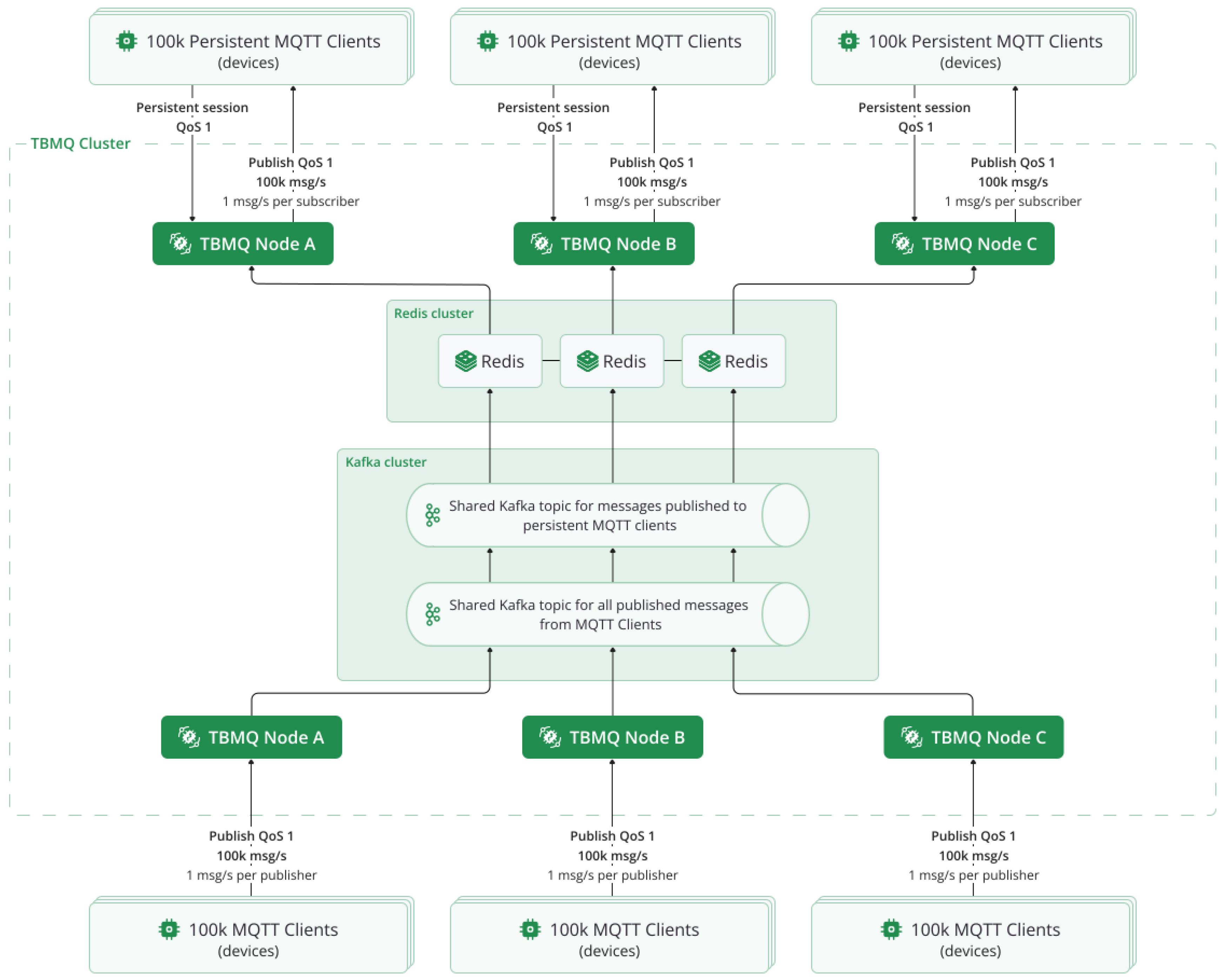

Figure 4 illustrates the updated architecture, where Redis replaces PostgreSQL as the persistence layer for standard MQTT clients.

With these benefits in mind, the migration process was initiated by evaluating data structures capable of preserving the functionality of the PostgreSQL approach while aligning with Redis Cluster constraints to enable efficient horizontal scaling. This also presented an opportunity to improve certain aspects of the original design, such as periodic cleanups, by leveraging Redis features like built-in expiration mechanisms.

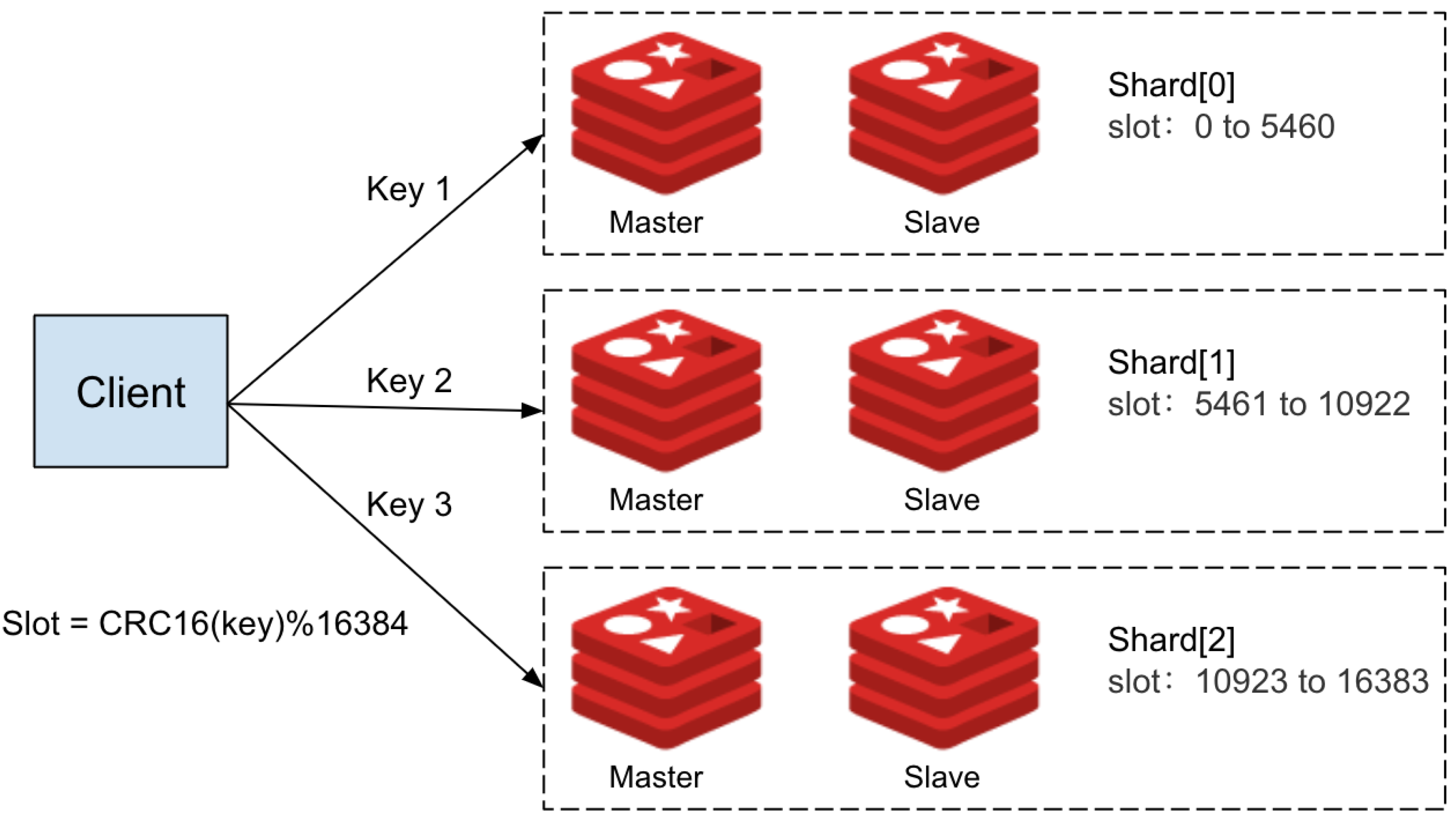

2.3.1. Redis Cluster Constraints

During the migration from PostgreSQL to Redis, it was identified that replicating the existing data model would require the use of multiple Redis data structures to efficiently handle message persistence and ordering. This, in turn, meant using multiple keys for each persistent MQTT Client session (see

Figure 5)..

Redis Cluster distributes data across multiple slots to enable horizontal scaling. However, multi-key operations must access keys within the same slot. If the keys reside in different slots, the operation triggers a cross-slot error, preventing the command from executing. The persistent MQTT client ID was embedded as a hash tag in key names to address this. By enclosing the client ID in curly braces , Redis ensures that all keys for the same client are hashed to the same slot. This guarantees that related data for each client stays together, allowing multi-key operations to proceed without errors.

2.3.2. Atomic Operations with Lua Scripting

Consistency is critical in a high-throughput environment like TBMQ, where many messages can arrive simultaneously for the same MQTT client. Hashtagging helps to avoid cross-slot errors, but without atomic operations, there is a risk of race conditions or partial updates. This could lead to message loss or incorrect ordering. It is important to make sure that operations updating the keys for the same MQTT client are atomic, Figure .

While Redis ensures atomic execution of individual commands, updating multiple data structures for each MQTT client required additional handling. Executing these sequentially without atomicity opens the door to inconsistencies if another process modifies the same data in between commands. That’s where Lua scripting comes in. Lua script executes as a single, isolated unit. During script execution, no other commands can run concurrently, ensuring that the operations inside the script happen atomically.

Based on this information, for operations such as saving messages or retrieving undelivered messages upon reconnection, a separate Lua script is executed. This ensures that all operations within a single Lua script reside in the same hash slot, maintaining atomicity and consistency.

2.3.3. Choosing the right Redis data structures

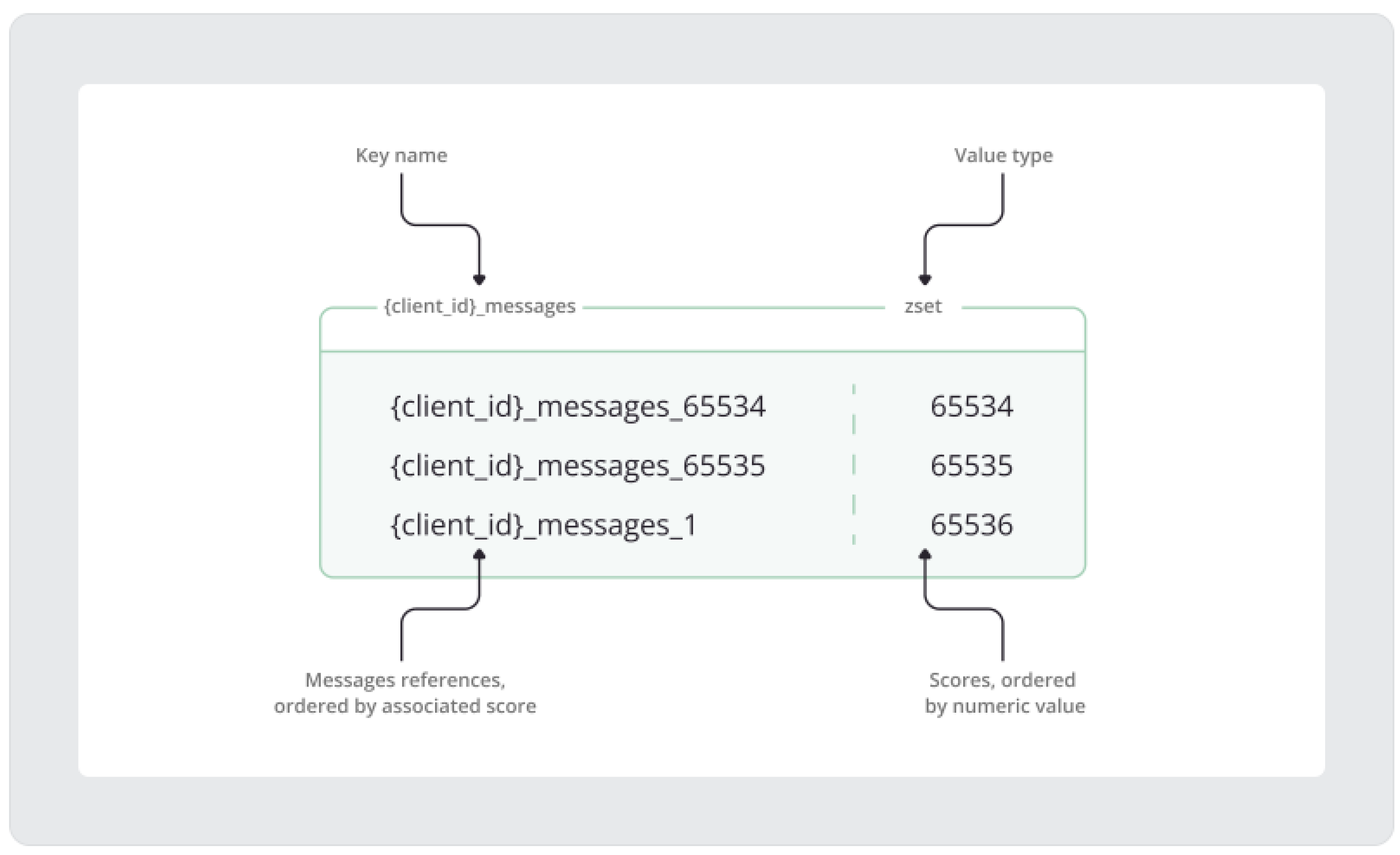

One of the key requirements of the migration was maintaining message order, a task previously handled by the serial_number column in PostgreSQL’s device_publish_msg table. An evaluation of Redis data structures identified sorted sets (ZSETs) as the most suitable replacement.

Redis sorted sets naturally organize data by score, enabling quick retrieval of messages in ascending or descending order. While sorted sets provided an efficient way to maintain message order, storing full message payloads directly in sorted sets led to excessive memory usage. Redis does not support per-member

within sorted sets. As a result, messages persisted indefinitely unless explicitly removed. Periodic cleanups using

ZREMRANGEBYSCORE were required, similar to the approach used in PostgreSQL, to remove expired messages. This operation carries a complexity of

, where

N is the number of elements in the set and

M is the number of elements removed. To address this limitation, message payloads were stored in string data structures, while the sorted set maintained references to these string keys.

Figure 6 illustrates this structure,

client_id is a placeholder for the actual client ID, while the curly braces around it are added to create a hash tag.

In the image above, you can see that the score continues to grow even when the MQTT packet ID wraps around.

Figure 6 illustrates the details illustrated in this image. At first, the reference for the message with the MQTT packet ID equal to 65534 was added to the sorted set:

ZADD {client_id}_messages65534{client_id}_messages_65534

Here, client_id_messages is the sorted set key name, where client_id acts as a hash tag derived from the persistent MQTT client’s unique ID. The suffix _messages is a constant added to each sorted set key name for consistency. Following the sorted set key name, the score value 65534 corresponds to the MQTT packet ID of the message received by the client. Finally, the reference key links to the actual payload of the MQTT message. Similar to the sorted set key, the message reference key uses the MQTT client’s ID as a hash tag, followed by the _messages suffix and the MQTT packet ID value.

In the following step, the message reference with a packet ID of 65535 is added to the sorted set. This is the maximum packet ID, as the range is limited to 65535.

ZADD {client_id}_messages65535{client_id}_messages_65535

Since the MQTT packet ID wraps around after 65535, the next message will receive a packet ID of 1. To preserve the correct sequence in the sorted set, the score is incremented beyond 65535 using the following Redis command:

ZADD {client_id}_messages65536{client_id}_messages_1

So at the next iteration MQTT packet ID should be equal to 1, while the score should continue to grow and be equal to 65536.

This approach ensures that the message’s references will be properly ordered in the sorted set regardless of the packet ID’s limited range.

Message payloads are stored as string values with SET commands that support expiration , providing complexity for writes and applications:

SET {client_id}_messages_1 "{

\"packetType\":\"PUBLISH\",

\"payload\":\"eyJkYXRhIjoidGJtcWlzYXdlc29tZSJ9\",

\"time\":1736333110026,

\"clientId\":\"client\",

\"retained\":false,

\"packetId\":1,

\"topicName\":\"europe/ua/kyiv/client/0\",

\"qos\":1

}" EX 600

Another benefit aside from efficient updates and applications is that the message payloads can be retrieved:

GET {client_id}_messages_1

or removed:

DEL {client_id}_messages_1

with constant complexity without affecting the sorted set structure.

Another very important element of Redis architecture for persistence message storage is the use of a string key to store the last MQTT packet ID processed:

GET {client_id}_last_packet_id "1"

This approach serves the same purpose as in the PostgreSQL solution. When a client reconnects, the server must determine the correct packet ID to assign to the next message that will be saved in Redis. An initial approach involved using the highest score in the sorted set as a reference. However, because scenarios may arise where the sorted set is empty or removed, storing the last packet ID separately was identified as the most reliable solution.

2.3.4. Managing Sorted Set Size Dynamically

This hybrid approach, leveraging sorted sets and string data structures, eliminates the need for periodic cleanups based on time, as per-message are now applied. In addition, to remain consistent with the PostgreSQL design, it was necessary to implement cleanup of the sorted set based on the message limit defined in the configuration.

Maximum number of PUBLISH messages stored for each persisted DEVICE client

limit: "${MQTT_PERSISTENT_SESSION_DEVICE_PERSISTED_MESSAGES_LIMIT:10000}"

This limit is an important part of a design that allows control and prediction of the memory allocation required for each persistent MQTT client. For example, a client might connect, triggering the registration of a persistent session, and then rapidly disconnect. In such scenarios, it is essential to ensure that the number of messages stored for the client (while waiting for a potential reconnection) remains within the defined limit, preventing unbounded memory usage.

if (messagesLimit > 0xffff) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException(

"Persisted messages limit can’t be greater than 65535!");

}

To reflect the natural constraints of the MQTT protocol, the maximum number of persisted messages for individual clients is set to 65535.

Dynamic management of the sorted set’s size was introduced in the Redis implementation to address this requirement. When new messages are added, the sorted set is trimmed to ensure the total number of messages remains within the desired limit, and the associated strings are also cleaned up to free up memory.

-- Get the number of elements to be removed

local numElementsToRemove = redis.call(’ZCARD’, messagesKey) - maxMessagesSize

-- Check if trimming is needed

if numElementsToRemove > 0 then

-- Get the elements to be removed (oldest ones)

local trimmedElements = redis.call(’ZRANGE’, messagesKey, 0, numElementsToRemove - 1)

-- Iterate over the elements and remove them

for _, key in ipairs(trimmedElements) do

-- Remove the message from the string data structure

redis.call(’DEL’, key)

-- Remove the message reference from the sorted set

redis.call(’ZREM’, messagesKey, key)

end

end

2.3.5. Message Retrieval and Cleanup

The design not only ensures dynamic size management during the persistence of new messages but also supports cleanup during message retrieval, which occurs when a device reconnects to process undelivered messages. This approach keeps the sorted set clean by removing references to expired messages.

-- Define the sorted set key

local messagesKey = KEYS[1]

-- Define the maximum allowed number of messages

local maxMessagesSize = tonumber(ARGV[1])

-- Get all elements from the sorted set

local elements = redis.call(’ZRANGE’, messagesKey, 0, -1)

-- Initialize a table to store retrieved messages

local messages = {}

-- Iterate over each element in the sorted set

for _, key in ipairs(elements) do

-- Check if the message key still exists in Redis

if redis.call(’EXISTS’, key) == 1 then

-- Retrieve the message value from Redis

local msgJson = redis.call(’GET’, key)

-- Store the retrieved message in the result table

table.insert(messages, msgJson)

else

-- Remove the reference from the sorted set if the key does not exist

redis.call(’ZREM’, messagesKey, key)

end

end

-- Return the retrieved messages

return messages

By leveraging Redis’ sorted sets and strings, along with Lua scripting for atomic operations, TBMQ achieves efficient message persistence and retrieval, as well as dynamic cleanup. This design addresses the scalability limitations of the PostgreSQL-based solution.

The following sections present the performance comparison between the new Redis-based architecture and the original PostgreSQL solution.