Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The Early Evidence on Developing Immunity

2. Methods

2.1. Trends in Fatality Infection Ratio

2.2. Extrapolation to Ultimate Pandemic Mortality Burden

3. Results

3.1. Seropositivity and Exposure Response

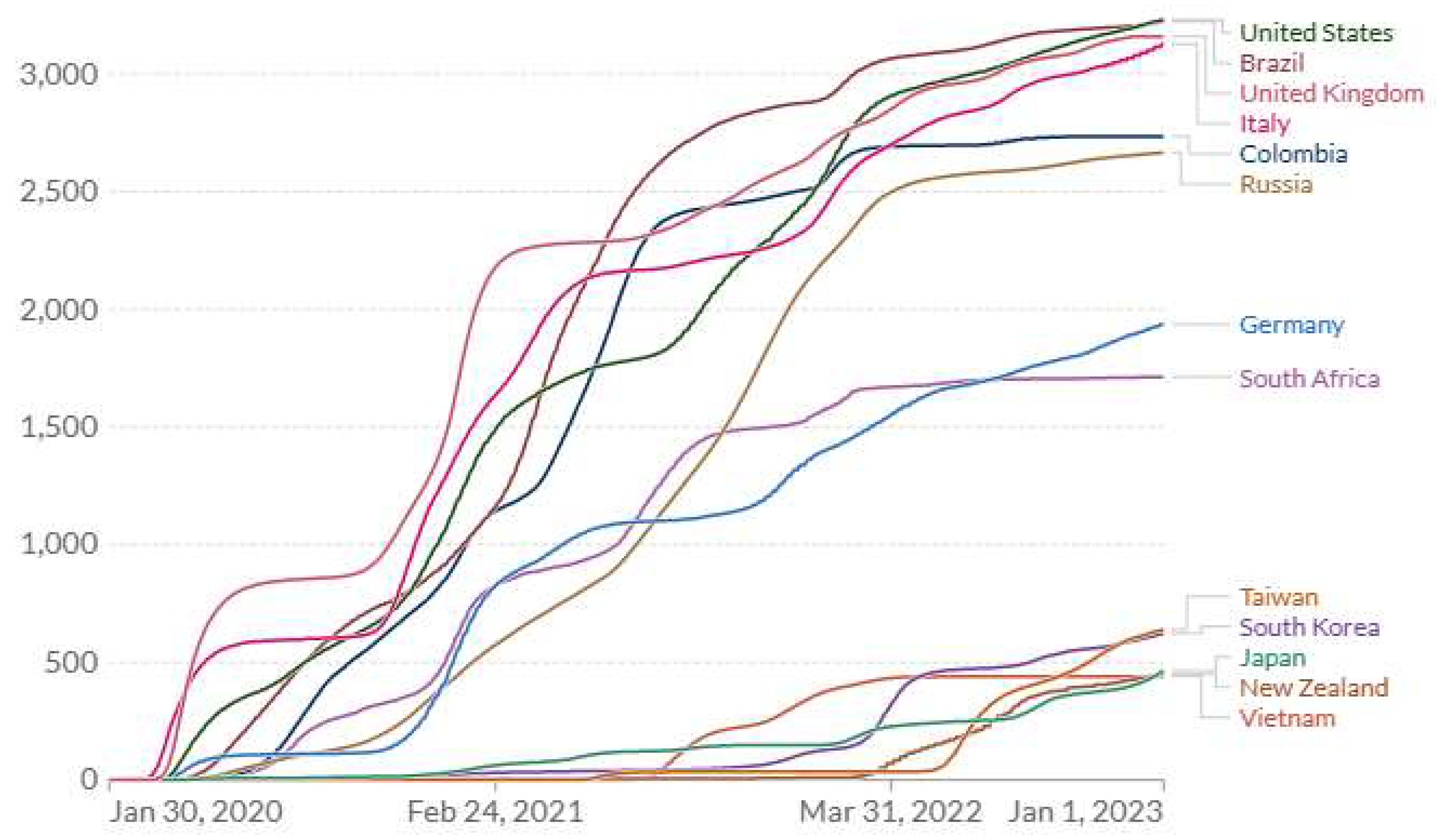

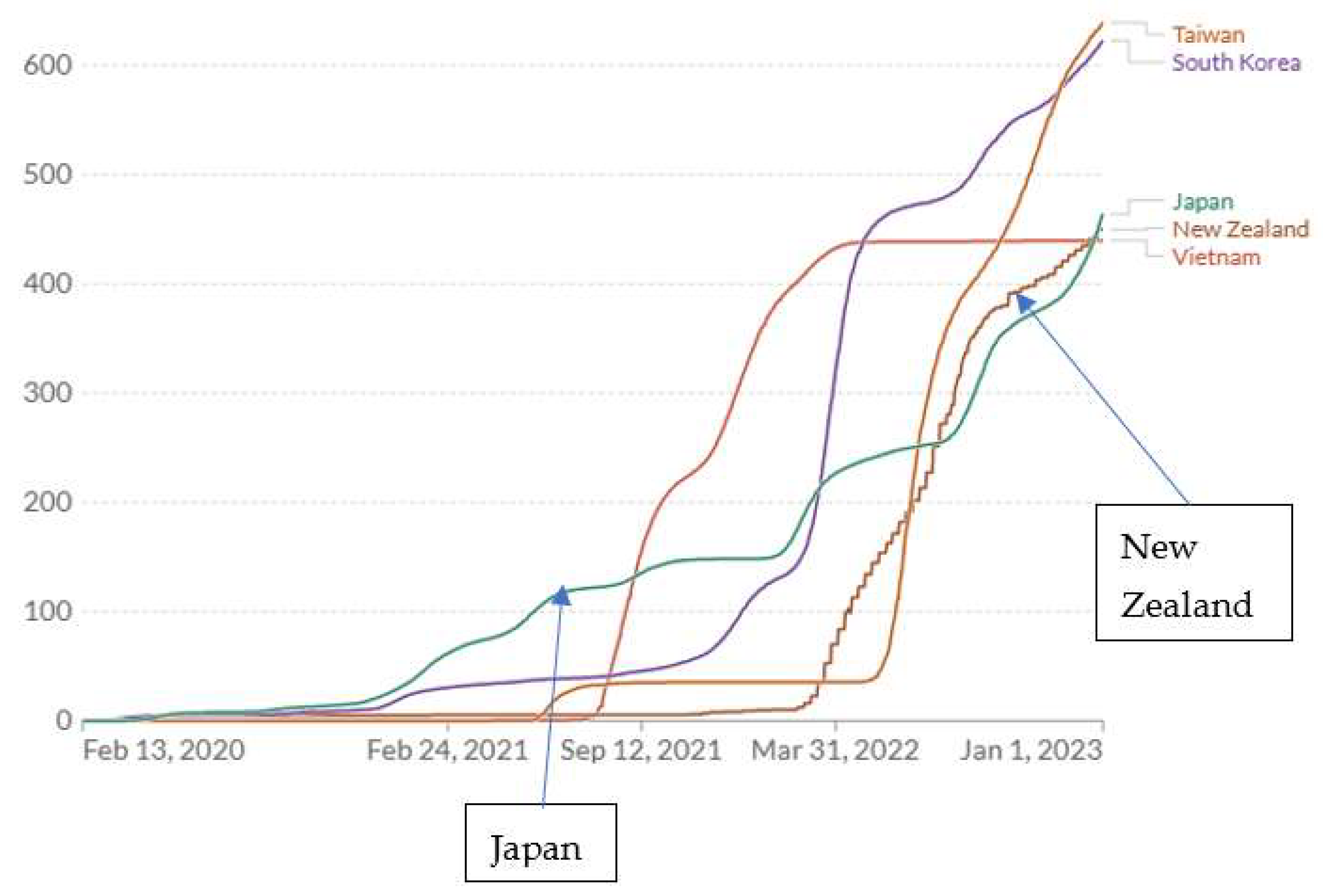

3.2. Retrospective Empirical Evidence from the COVID-19 Pandemic Across Countries

3.3. The Chinese COVID-19 Pandemic Experience

3.4. Drivers of Pandemic Control Decisions

4. Discussion

4.1. Conclusions

- Taiwan and possibly some other countries achieved very low COVID-19 mortality rates without resorting to comprehensive lockdowns.

- The countries maintaining very low COVID-19 mortality rates also largely suppressed natural COVID-19 immunity.

- Widespread acceptance of face masks in the zero-COVID countries suggests this is a critical component of exposure control along with distancing and isolation procedures. Downsizing routine respiratory protection from full cannister to N95 facemasks and primitive cloth masks would be appropriate based on exposure surveys.

- The policies followed in Japan during 2020-2021 appear to have been close to optimal for minimizing COVID-19 cumulative mortality.

- Decisions to relax strong COVID-1 suppression based on diminishing case or fatality rates resulted in high mortality among residual unprotected populations.

- A primary prevention emphasis where ambient COVID-19 air concentrations would be systematically monitored to achieve levels in an optimal range. Supplemental sampling protocols would target: educational, retail, transportation, medical, recreational, and workplaces. Sampling the built environment would inform distancing, filtration and air-change goals. Efficient, low-cost sampling and high-throughput virus determination technology would be promoted.

- Assessment of seropositivity prevalence in place of routine, repetitive mass (costly) PCR testing for new cases. Seropositivity information would be needed to a) specify the operational parameters of the exposure control strategy, b) inform secondary prevention (e.g., allocation of masks), c) identify the remaining unprotected population, and d) facilitate decision-making in the workplace.[39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46] Seropositivity surveys would be conducted on small representative samples of local populations, but for some subpopulations would attempt to survey everyone: nursing homes, anyone having routine contact with the public or other workers; travelers by air or rail who could be required to show seropositivity documentation (or a current negative PCR test). Low-cost, high throughput seropositivity testing would drive innovations as happened with PCR testing for COVID-19 cases.

4.2. Strengths, Limitations and Needs

Acknowledgments

References

- Goldstein J. 68% Have Antibodies in This Clinic. Can a Neighborhood Beat a Next Wave? New York Times July 9, 2020; https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-antibodies.html ; published July 9, 2020 Updated July 10, 2020.

- Bendavid E, Mulaney B, Sood N, et al. COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in Santa Clara County, California. Intl J Epidemiol 2021; 50: 410-419. [CrossRef]

- Bartsch SM, Ferguson MC, McKinnell JA, et al. The potential health care costs and resource use associated with COVID-19 in the United States. Health Affairs 2020; 39: 927-935. [CrossRef]

- Bartsch SM, O’Shea KJ, Wedlock PT, et al. The benefits of vaccinating with the first available COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine. Am J Prev Med 2021; 60: 605−613.

- Conlen M, Smart C. When could the U.S. reach herd immunity? It’s complicated. New York Times Feb 24, 2021.

- Pei S, Yamana TK, Kandula S, et al. Burden and characteristics of COVID-19 in the United States during 2020. Nature 2021; 598: 338-341. [CrossRef]

- Barron J. Coronovirus update. New York Times Jan 26, 2021.

- Clarke KEN, Jones JM, Deng Y, et al. Seroprevalence of Infection-Induced SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies — United States, September 2021–February 2022. MMWR 2022 (April 29); 71: 606-608.

- Morawska L, Cao J. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: The world should face the reality. Environ Intl 2020; 139: 105730.

- Anderson EL, Turnham P, Griffin JR, et al. Consideration of the aerosol transmission for COVID-19 and public health. Risk Analysis 2020; 40: 902-907. [CrossRef]

- Lee LYW, Rozmanowski S, Pang M, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2) infectivity by viral load, s gene variants and demographic factors, and the utility of lateral flow devices to prevent transmission. Clin Infectious Dis 2022; 74: 407-415. https://doi.10.1093/cid/ciab421.

- Pujadas E, Chaudhry F, McBride R, et al. SARS-Co V-2 viral load predicts COVID-19 mortality. Lancet / respiratory (letter) 2020; 8: e70. [CrossRef]

- Coronavirus Resource Center, Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE), Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD; https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/about , https://systems.jhu.edu/research/public-health/ncov/.

- Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Rodés-Guirao L et al. (2020). Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Global Change Data Lab: Published online at OurWorldInData.org: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

- Ho H-L, Wang F-Y, Lee H-R, et al. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 in Taiwan revealed by testing anti-SARS-CoV-2 serological antibodies on 14,765 hospital patients. Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific 3 (2020) 100041. [CrossRef]

- Carlton LH, Chen T, Whitcombe AL, et al. Charting elimination in the pandemic: a SARS-CoV-2 serosurvey of blood donors in New Zealand. Epidemiol Infection 2021; 149: e173, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Nah E-H, Cho S, Park H, et al. Nationwide seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in asymptomatic population in South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e049837. [CrossRef]

- Hasan T, Pham TN, Nguyen TA, et al. Sero-prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in high-risk populations in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18 6353. [CrossRef]

- Gornyk D, Harries M, Glöckner S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Germany—a population-based sequential study in seven regions. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2021; 118: 824-831. [CrossRef]

- Doi A, Iwata K, Kuroda H, et al. Estimation of seroprevalence of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) using preserved serum at an outpatient setting in Kobe, Japan: A cross-sectional study. Clin Epidemiol Global Health 2021; 11: 100747. [CrossRef]

- Reuters. Only 5% of Spain’s population has coronavirus antibodies, despite severe outbreak: study. https://globalnews.ca/news/7144280/spain-immunity-study-coronavirus/ Updated July 6, 2020, accessed Nov 17, 2022.

- Ahlander J, Pollard N. Swedish antibody study shows long road to immunity as COVID-19 toll mounts. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-sweden-strategy/swedish-antibody-study-shows-long-road-to-immunity-as-COVID-19-toll-mounts-idUSKBN22W2YC , May 20, 2020; accessed Nov 17, 2022.

- Huergo LF, Paula NM, Gonçalves ACA, et al. sars-cov-2 seroconversion in response to infection and vaccination: a time series local study in Brazil. Microbiol Spectrum 2022; 10: 10.1128/ spectrum.01026-2022.

- Wells PM, Doores KJ, Couvreur S, et al. Estimates of the rate of infection and asymptomatic COVID-19 disease in a population sample from SE England. J Infection 2020; 81: 931-936. [CrossRef]

- Shakiba M, Nazemipour M, Heidarzadeh A, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic COVID-19 infection using a seroepidemiological survey. Epidemiol Infection 2020; 148: e300, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Talaei M, Faustini S, Holt H, et al. Determinants of pre-vaccination antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2: a population-based longitudinal study (COVIDENCE UK). BMC Medicine 2022; 20: 87. [CrossRef]

- Prakash O, Solanki B, Sheth JK, et al. Assessing seropositivity for IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in Ahmedabad city of India: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2021; 11: e044101. https://doi.10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044101.

- Stefanelli P, Bella A, Fedele G, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in an area of northeastern Italy with a high incidence of COVID-19 cases: a population-based Study. Clin Microbiol Infection 2021; 27: 633.e1e633.e7. [CrossRef]

- Alhazmi A, Alamer E, Abdelwahab S, et al. Community-based seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies following the First Wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Jazan Province, Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18: 12451. [CrossRef]

- Bin-Ghouth AS, Al-Shoteri S, Mahmoud N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Aden, Yemen: a population-based study. Intl J Infectious Dis 2022; 115: 239-244. [CrossRef]

- Mattar S, Alvis-Guzman N, Garay E, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 seroprevalence among adults in a tropical city of the Caribbean area, Colombia: Are we much closer to herd immunity than developed countries? Open Forum Inf Dis 2020; 7: ofaa550. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari A, Yin J. Short-term effects of ambient ozone, pm2.5, and meteorological factors on COVID-19 confirmed cases and deaths in Queens, New York. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17: 4047. https://doi.10.3390/ijerph17114047.

- Madhi SA, Kwatra G, Myers JE, et al. Population immunity and COVID-19 severity with omicron variant in South Africa. N Engl J Med 2022; 386: 1314-1326. https://doi.10.1056/NEJMoa2119658.

- Einhauser S, Peterhoff D, Beileke S, et al. Time trend in SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity, surveillance detection- and infection fatality ratio until Spring 2021 in the Tirschenreuth County—results from a population-based longitudinal study in Germany. Viruses 2022; 14: 1168. [CrossRef]

- Qin A, Chang A, Qian I. Eyes on its economy, Taiwan shifts to coexisting with COVID. New York Times May 10, 2022.

- Xiao M, Hvistendahl M, Glanz J. Data briefly hinted at China’s hidden COVID toll. New York Times July 20, 2023.

- Du Z, Wang Y, Yuan Bai Y, et al. Estimate of COVID-19 deaths, China, December 2022–February 2023. Emerg Inf Disease 2023 29:2121-2124.

- Stern RA, Koutrakis P, Martins MAG, et al. Characterization of hospital airborne SARS-CoV-2. Respir Res 2021; 22: 73. [CrossRef]

- USDA. https://www.ers.usda.gov/COVID-19/rural-america/meatpacking-industry/ May 13, 2021.

- Hassan A. Coronavirus cases and deaths were vastly underestimated in U.S. meatpacking plants, a House report says. New York Times, Oct. 28, 2021 https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/28/world/meatpacking-workers-COVID-cases-deaths.html.

- House report. Memorandum: Coronavirus infections and deaths among meatpacking workers at top five companies were nearly three times higher than previous estimates. U.S. House of Representatives, Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, October 27, 2021. https://coronavirus-democrats-oversight.house.gov/sites/democrats.coronavirus.house.gov/files/2021.10.27%20Meatpacking%20Report.Final.pdf.

- Grabell M. The plot to keep meatpacking plants open during COVID-19. Propublica, May 13, 2022; https://www.propublica.org/article/documents-COVID-meatpacking-tyson-smithfield-trump.

- Mutambudzi M, Niedzwiedz C, Macdonald EB, et al. Occupation and risk of severe COVID-19: prospective cohort study of 120 075 UK Biobank participants. Occup Environ Med 2021; 78: 307-314.

- Billock RM, Steege AL, Miniño A. COVID-19 mortality by usual occupation and industry: 46 States and New York City, United States, 2020. National Vital Statistics Reports 2022; 71(6): 1-33, October 28, 2022.

- Carlsten C, Gulati M, Hines S, et al. COVID-19 as an occupational disease. Amer J Ind Med 2021; 64: 227-237.

- Michaels D, Wagner GR. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and worker safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA 2020; 324: 1389-1390.

- Cole HVS, Anguelovski I, Baró F, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: power and privilege, gentrification, and urban environmental justice in the global north. Cities & Health 2021; 5(No. S1): S71-S75; [CrossRef]

- Benmarhnia T. Linkages between air pollution and the health burden from COVID-19: methodological challenges and opportunities. Am J Epidemiol 2020; 189(11): 1238-1243.

- Terrell KA, James W. Racial disparities in air pollution burden and COVID-19 deaths in Louisiana, USA, in the context of long-term changes in fine particulate pollution. Environ Justice 2022; 15(5), published online:14 Oct 2022; [CrossRef]

- Ellis A. Examining an intersection of environmental justice and COVID-19 risk assessment: a review. University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Honors Theses, 2021; https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses/347.

- Mandavilli A, Qui L, Athes E. Dairy workers at risk in outbreak of bird flu. New York Times May 10, 2024.

- Bright R. Testing can stop the spread of bird flu. New York Times June 4, 2024.

| Country/region (ref:1-5,15-34) | Survey date mm/dd/yyyy |

Seropositivity | IFR1 | FIR1 | CFR1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwan | 07-15-2020 | 0.0005 | 0.00058 | 17242 | 0.0153 |

| New Zealand | 12-16-2020 | 0.0010 | 0.0050 | 200 | 0.0124 |

| S Korea | 11-01-2020 | 0.0024 | 0.0037 | 268 | 0.0175 |

| Vietnam/high risk region | 10-15-2020 | 0.004 | 0.000092 | 111112 | - |

| Germany/7 regions | 08-15-2020 | 0.020 | 0.015 | 67 | 0.040 |

| US/California (Santa Clara) | 03-20-2020 | 0.028 | 0.0017 | 5882 | 0.075 |

| Japan/Kobe | 04-07-2020 | 0.033 | 0.000022 | 428572 | 0.021 |

| Spain | 07-06-2020 | 0.052 | 0.0115 | 87 | 0.113 |

| Sweden | 07-23-2020 | 0.073 | 0.00736 | 136 | 0.075 |

| Germany/Tirschenreuth | 11-22-2020 | 0.092 | 0.023 | 43 | 0.084 |

| Brazil/Matinhos | 07-01-2021 | 0.11 | - | - | - |

| UK/Southeast | 05-12-2020 | 0.12 | - | - | - |

| Iran/Guilan | 04-15-2020 | 0.12 | - | - | - |

| UK | 01-15-2021 | 0.15 | 0.0108 | 93 | 0.034 |

| India/Ahmedabad | 12-31-2020 | 0.18 | - | - | - |

| US/New York State | 06-15-2020 | 0.22 | - | - | - |

| Italy | 05-10-2020 | 0.23 | 0.0022 | 455 | 0.140 |

| US/New York City | 06-26-2020 | 0.26 | - | - | - |

| Saudi Arabia/Jazan | 11-01-2020 | 0.26 | - | - | - |

| Yemen/Aden | 12-01-2020 | 0.27 | - | - | - |

| US | 12-31-2020 | 0.31 | 0.0033 | 303 | 0.0173 |

| Colombia/Monteria | 10-14-2020 | 0.55 | 0.0058 | 172 | 0.063 |

| US/NYC(Queens) | 06-15-2020 | 0.68 | 0.00212 | 4762 | - |

| SA/Gauteng | 12-15-2020 | 0.68 | 0.000612 | 16392 | 0.028 |

| country | year | Cases per million | Deaths per million | CFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 2020 | 36865 | 1407 | 0.0382 |

| 2021 | 154782 | 1223 | 0.0079 | |

| 2022 | 165862 | 529 | 0.0032 | |

| US | 2020 | 59763 | 1036 | 0.0173 |

| 2021 | 102538 | 1406 | 0.0137 | |

| 2022 | 135553 | 789 | 0.0058 | |

| Brazil | 2020 | 35673 | 906 | 0.0254 |

| 2021 | 67859 | 1971 | 0.0290 | |

| 2022 | 65205 | 346 | 0.0053 | |

| Japan | 2020 | 1902 | 28.2 | 0.0148 |

| 2021 | 12082 | 119 | 0.0099 | |

| 2022 | 221871 | 316 | 0.0014 | |

| S Korea | 2020 | 1192 | 17.7 | 0.0148 |

| 2021 | 11068 | 92.3 | 0.0083 | |

| 2022 | 549669 | 513 | 0.0009 | |

| New Zealand | 2020 | 417 | 5.0 | 0.0120 |

| 2021 | 2306 | 4.3 | 0.0019 | |

| 2022 | 401277 | 440 | 0.0011 | |

| Taiwan | 2020 | 33.4 | 0.29 | 0.0087 |

| 2021 | 679.6 | 35.3 | 0.0520 | |

| 2022 | 369572 | 603 | 0.0016 | |

| Vietnam | 2020 | 14.9 | 0.36 | 0.0242 |

| 2021 | 17617 | 331 | 0.0188 | |

| 2022 | 99749 | 108 | 0.0011 |

| Country | Cum. cases/K | Cum. deaths/M | CFR1 | Cum. cases/K | Cum. deaths/M | CFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| as of July 1, 2020 | as of Dec 31, 2024 | |||||

| UK | 4.20 | 834 | 0.199 | 367 | 3404 | 0.009 |

| Italy | 4.08 | 589 | 0.144 | 452 | 3345 | 0.007 |

| US | 8.14 | 381 | 0.047 | 303 | 3548 | 0.012 |

| Brazil | 6.98 | 289 | 0.041 | 178 | 3339 | 0.019 |

| Germany | 2.34 | 108 | 0.046 | 457 | 2081 | 0.005 |

| S Africa | 2.81 | 47.5 | 0.017 | 65.2 | 1645 | 0.025 |

| Japan | 0.153 | 7.88 | 0.052 | 270 | 598 | 0.002 |

| S Korea | 0.250 | 5.44 | 0.022 | 668 | 694 | 0.001 |

| New Zealand | 0.295 | 4.44 | 0.015 | 519 | 876 | 0.002 |

| Taiwan2 | 0.018 | 0.29 | 0.016 | - | - | - |

| Vietnam3 | 0.003 | - | - | 117 | 433 | 0.004 |

| Country | Pop (M) |

Cum. mort. rate/M @ end 2022 | Annual mort. rate /M @ end 20221 |

% Vacc. @ end 2022 |

Avg. FIR | Proportion at risk @ end2022 (prevalence) | Annual mort. rate/M @ end 2022 in population at-risk2 |

Cum. mort. rate/M @ end 2024 |

Pandemic deaths @ end 2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 329 | 3230 | 367 | 68.6 | 2273 | 0.126 | 2913 | 3548 | 1,167,292 |

| UK | 67.1 | 3159 | 367 | 76.54 | 94 | 0.204 | 1799 | 3404 | 228,408 |

| Italy | 59.5 | 3128 | 573 | 81.3 | 945 | 0.171 | 3351 | 3345 | 199,028 |

| Germany | 83.2 | 1937 | 520 | 76.5 | 75 | 0.239 | 2176 | 2081 | 173,139 |

| Taiwan7 | 23.6 | 639 | 460 | 86.3 | 2666 | 0.155 | 2968 | 11827 | 27,893 |

| S Korea | 51.7 | 623 | 393 | 86.3 | 266 | 0.155 | 2535 | 694 | 35,880 |

| New Zealand | 5.1 | 450 | 267 | 79.8 | 200 | 0.223 | 1197 | 876 | 4,468 |

| Japan | 126.3 | 464 | 986 | 83.2 | 2666 | 0.188 | 5245 | 598 | 75,527 |

| Japan8 | 126.3 | 235 | 80 | 82.0 | 266 | 0.209 | 383 | 3488 | 43,952 |

| Japan9 | 126.3 | 145 | 80 | 81.0 | 266 | 0.223 | 359 | 2769 | 34,859 |

| Country |

Pop (M) |

Initial annual mortality rate/M1 | Annual mortality rate/M2 @ end 2022 |

Proportion at risk @ end 20223,4 (prevalence) |

Annual mortality rate/M in population at risk @ end 20224 |

| US | 329 | 2591 | 367 | 0.126 | 2913 |

| UK | 67.1 | 6751 | 367 | 0.204 | 1799 |

| Taiwan | 23.6 | 0.29 | 460 | 0.155 | 2968 |

| S Korea | 51.7 | 14.3 | 393 | 0.155 | 2535 |

| Japan | 126 | <10 | 986 | 0.188 | 5245 |

| estimate from July 2022 | <10 | 804 | 0.209 | 383 | |

| estimate from Feb 2022 | <10 | 804 | 0.223 | 359 | |

| China, 0% immunity3 | 1400 | <1815 | <1815 | 1.0 | 54776 |

| China, 10% immunity3 | <1815 | <1815 | 0.9 | 58936 | |

| China, 20% immunity3 | <1815 | <1815 | 0.8 | 63686 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).