Submitted:

06 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

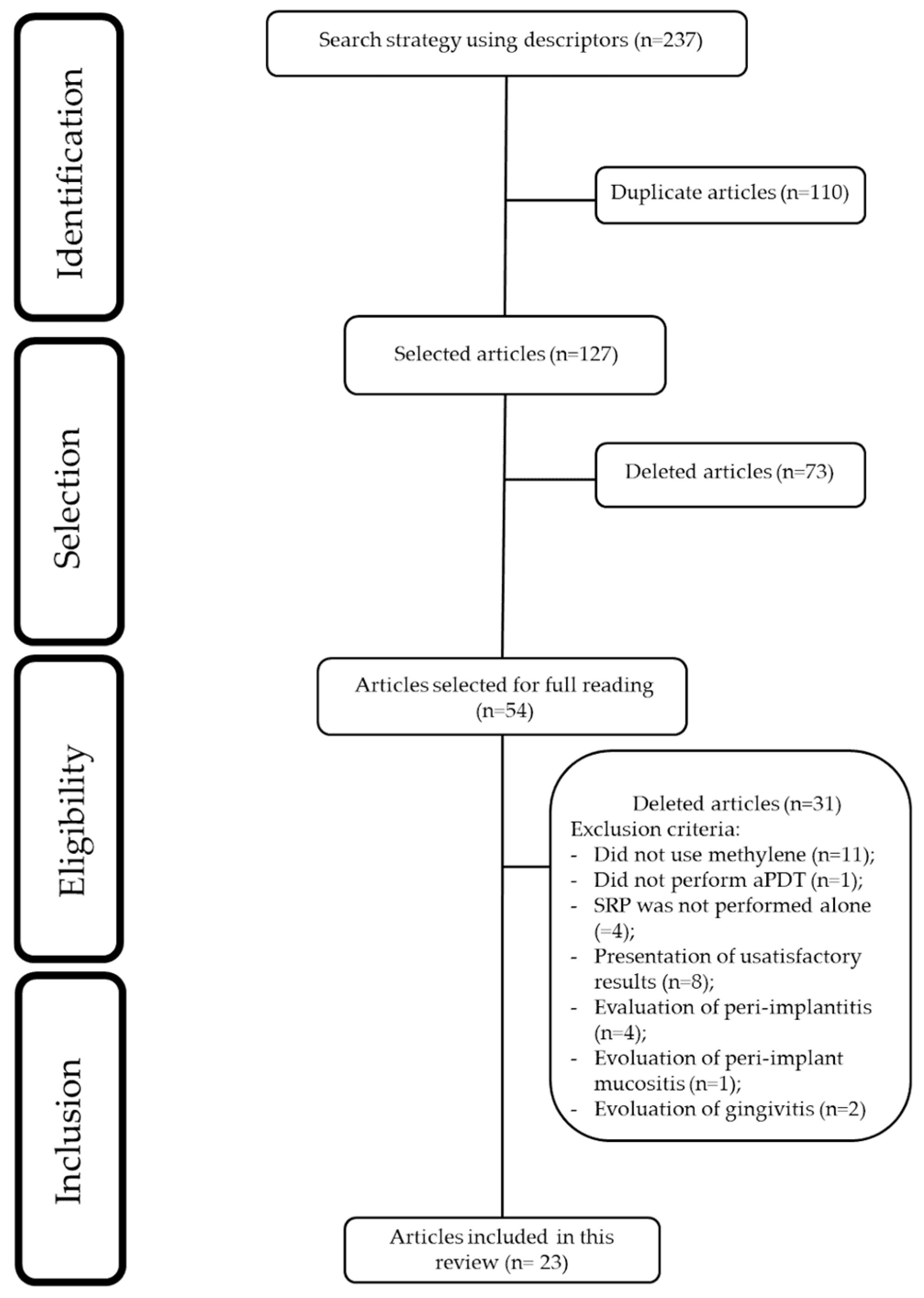

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibity Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process

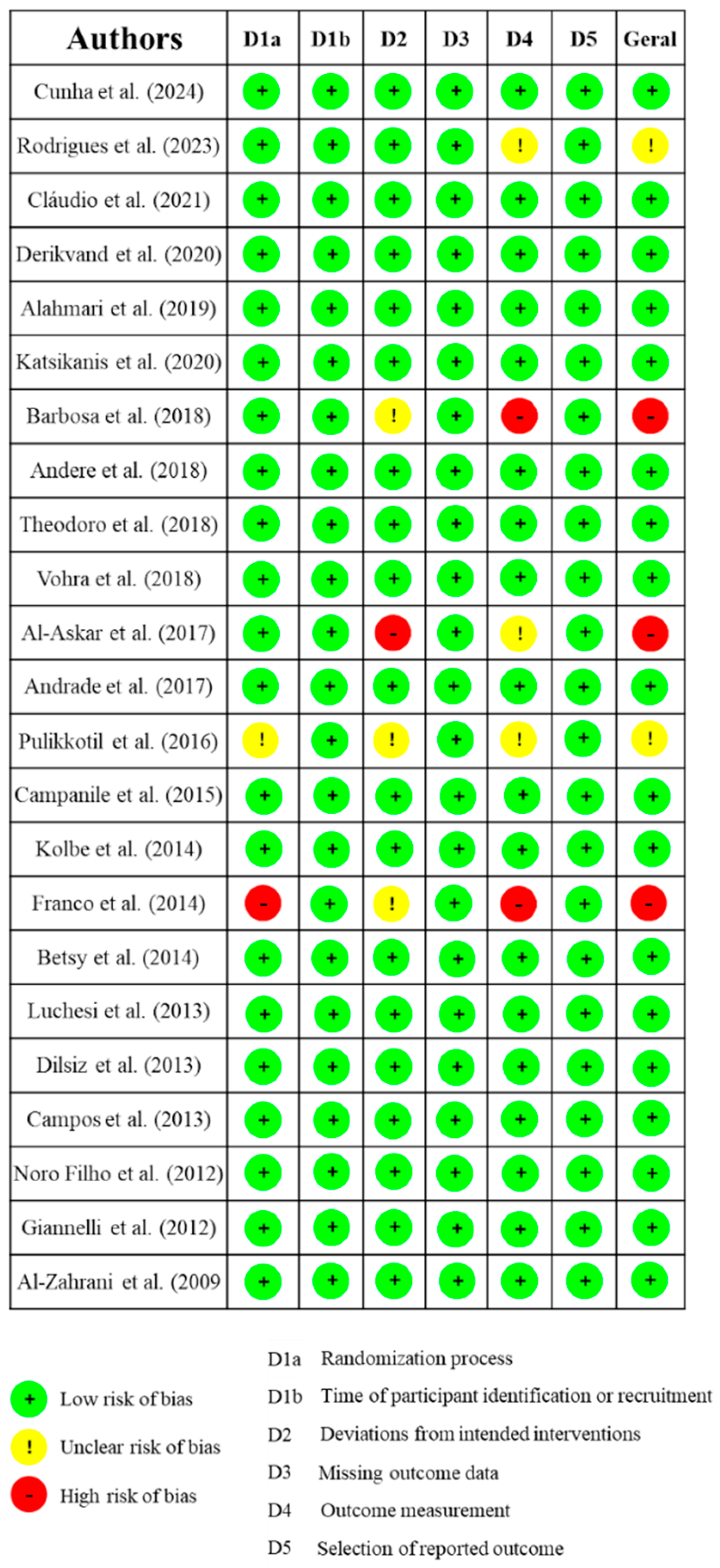

2.6. Risk of Bias

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Studies Included sin This Review

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Passanezi, E.; Damante, C. A.; de Rezende, M. L.; Greghi, S. L. Lasers in periodontal therapy. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 67, 268–291. [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; Herrera, D.; Kebschull, M.; Chapple, I.; Jepsen, S.; Beglundh, T.; Sculean, A.; Tonetti, M. S.; EFP Workshop Participants and Methodological Consultants. Treatment of stage I-III periodontitis—The EFP S3 level clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 Suppl 22(Suppl 22), 4–60. [CrossRef]

- Figuero, E.; Roldán, S.; Serrano, J.; Escribano, M.; Martín, C.; Preshaw, P. M. Efficacy of adjunctive therapies in patients with gingival inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 Suppl 22, 125–143. [CrossRef]

- Salvi, G. E.; Stähli, A.; Schmidt, J. C.; Ramseier, C. A.; Sculean, A.; Walter, C. Adjunctive laser or antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to non-surgical mechanical instrumentation in patients with untreated periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2020, 47 Suppl 22, 176–198. [CrossRef]

- Gois, M. M.; Kurachi, C.; Santana, E. J.; Mima, E. G.; Spolidório, D. M.; Pelino, J. E.; Salvador Bagnato, V. Susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus to porphyrin-mediated photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy: An in vitro study. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 391–395. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, J.; Rahban, D.; Aghamiri, S.; Teymouri, A.; Bahador, A. Photosensitizers in antibacterial photodynamic therapy: an overview. Laser therapy. 2018, 827(4), 293–302. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo-Godoi, L.M.A.; Garcia, M.T.; Pinto, J.G.; Ferreira-Strixino, J.; Faustino, E.G.; Pedroso, L.L.C.; Junqueira, J.C. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Mediated by Fotenticine and Methylene Blue on Planktonic Growth, Biofilms, and Burn Infections of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antibiotics. 2022, 11, 619. [CrossRef]

- Usacheva M. N; Teichert M. C.; Sievert C. E.; Biel M. A. Effect of Cat on the photobactericidal efficacy of methylene blue and toluidine blue against gram-negative bacteria and the dye affinity for lipopolysaccharides. Lasers Surg Med. 2006; 38(10):946-54.

- Cunha, P. O.; Gonsales, I. R.; Greghi, S. L. A.; Sant'ana, A. C. P.; Honório, H. M.; Negrato, C. A.; Zangrando, M. S. R.; Damante, C. A. Adjuvant antimicrobial photodynamic therapy improves periodontal health and reduces inflammatory cytokines in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2024, 32, e20240258. [CrossRef]

- Cláudio, M. M.; Nuernberg, M. A. A.; Rodrigues, J. V. S.; Belizário, L. C. G.; Batista, J. A.; Duque, C.; Garcia, V. G.; Theodoro, L. H. Effects of multiple sessions of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) in the treatment of periodontitis in patients with uncompensated type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled clinical study. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 35, 102451. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F. I.; Araújo, P. V.; Machado, L. J. C.; Magalhães, C. S.; Guimarães, M. M. M.; Moreira, A. N. Effect of photodynamic therapy as an adjuvant to non-surgical periodontal therapy: Periodontal and metabolic evaluation in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 22, 245–250. [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, M.; Al-Kheraif, A. A.; Ahmed, H. B.; Kellesarian, S. V.; Malmstrom, H.; Javed, F. Effectiveness of mechanical debridement with and without adjunct antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of periodontal inflammation among patients with prediabetes. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2017, 20, 91–94. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, M. S.; Bamshmous, S. O.; Alhassani, A. A.; Al-Sherbini, M. M. Short-term effects of photodynamic therapy on periodontal status and glycemic control of patients with diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 1568–1573. [CrossRef]

- Luchesi, V. H.; Pimentel, S. P.; Kolbe, M. F.; Ribeiro, F. V.; Casarin, R. C.; Nociti, F. H., Jr.; Sallum, E. A.; Casati, M. Z. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of class II furcation: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 781–788. [CrossRef]

- AlAhmari, F.; Ahmed, H. B.; Al-Kheraif, A. A.; Javed, F.; Akram, Z. Effectiveness of scaling and root planning with and without adjunct antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis among cigarette-smokers and never-smokers: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 25, 247–252. [CrossRef]

- Katsikanis, F.; Strakas, D.; Vouros, I. The application of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT, 670 nm) and diode laser (940 nm) as adjunctive approach in the conventional cause-related treatment of chronic periodontal disease: A randomized controlled split-mouth clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 1821–1827. [CrossRef]

- Theodoro, L. H.; Assem, N. Z.; Longo, M.; Alves, M. L. F.; Duque, C.; Stipp, R. N.; Vizoto, N. L.; Garcia, V. G. Treatment of periodontitis in smokers with multiple sessions of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy or systemic antibiotics: A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 22, 217–222. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R. D.; Araujo, N. S.; Filho, J. M. P.; Vieira, C. L. Z.; Ribeiro, D. A.; Dos Santos, J. N.; Cury, P. R. Photodynamic therapy as adjunctive treatment of single-rooted teeth in patients with grade C periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103776. [CrossRef]

- Derikvand, N.; Ghasemi, S. S.; Safiaghdam, H.; Piriaei, H.; Chiniforush, N. Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy with Diode laser and Methylene blue as an adjunct to scaling and root planning: A clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101818. [CrossRef]

- Andere, N. M. R. B.; Dos Santos, N. C. C.; Araujo, C. F.; Mathias, I. F.; Rossato, A.; de Marco, A. C.; Santamaria, M., Jr.; Jardini, M. A. N.; Santamaria, M. P. Evaluation of the local effect of nonsurgical periodontal treatment with and without systemic antibiotic and photodynamic therapy in generalized aggressive periodontitis. A randomized clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 24, 115–120. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, P. V.C.; Euzebio Alves, V. T.; de Carvalho, V. F.; De Franco Rodrigues, M.; Pannuti, C. M.; Holzhausen, M.; De Micheli, G.; Conde, M. C. Photodynamic therapy decrease immune-inflammatory mediators levels during periodontal maintenance. Lasers Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 9–17. [CrossRef]

- Pulikkotil, S. J.; Toh, C. G.; Mohandas, K.; Leong, K. Effect of photodynamic therapy adjunct to scaling and root planing in periodontitis patients: A randomized clinical trial. Aust. Dent. J. 2016, 61, 440–445. [CrossRef]

- Franco, E. J.; Pogue, R. E.; Sakamoto, L. H.; Cavalcante, L. L.; Carvalho, D. R.; de Andrade, R. V. Increased expression of genes after periodontal treatment with photodynamic therapy. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2014, 11, 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Betsy, J.; Prasanth, C. S.; Baiju, K. V.; Prasanthila, J.; Subhash, N. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the management of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2014, 41, 573–581. [CrossRef]

- Dilsiz, A.; Canakci, V.; Aydin, T. Clinical effects of potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser and photodynamic therapy on outcomes of treatment of chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 278–286. [CrossRef]

- Giannelli, M.; Formigli, L.; Lorenzini, L.; Bani, D. Combined photoablative and photodynamic diode laser therapy as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal treatment: A randomized split-mouth clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 962–970. [CrossRef]

- Campanile, V. S. M.; Giannopoulou, C.; Campanile, G.; Cancela, J. A.; Mombelli, A. Single or repeated antimicrobial photodynamic therapy as adjunct to ultrasonic debridement in residual periodontal pockets: Clinical, microbiological, and local biological effects. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, M. F.; Ribeiro, F. V.; Luchesi, V. H.; Casarin, R. C.; Sallum, E. A.; Nociti, F. H., Jr.; Ambrosano, G. M.; Cirano, F. R.; Pimentel, S. P.; Casati, M. Z. Photodynamic therapy during supportive periodontal care: clinical, microbiologic, immunoinflammatory, and patient-centered performance in a split-mouth randomized clinical trial. J. Periodontol. 2014, 85, e277–e286. [CrossRef]

- Campos, G. N.; Pimentel, S. P.; Ribeiro, F. V.; Casarin, R. C.; Cirano, F. R.; Saraceni, C. H.; Casati, M. Z. The adjunctive effect of photodynamic therapy for residual pockets in single-rooted teeth: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 317–324. [CrossRef]

- Vohra, F.; Akram, Z.; Bukhari, I. A.; Sheikh, S. A.; Javed, F. Short-term effects of adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in obese patients with chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2018, 21, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Noro Filho, G. A.; Casarin, R. C.; Casati, M. Z.; Giovani, E. M. PDT in non-surgical treatment of periodontitis in HIV patients: A split-mouth, randomized clinical trial. Lasers Surg. Med. 2012, 44, 296–302. [CrossRef]

- Jervøe-Storm, P. M.; Bunke, J.; Worthington, H. V.; Needleman, I.; Cosgarea, R.; MacDonald, L.; Walsh, T.; Lewis, S. R.; Jepsen, S. Adjunctive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy for treating periodontal and peri-implant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 7, CD011778. [CrossRef]

- Vohra, F.; Akram, Z.; Safii, S. H.; Vaithilingam, R. D.; Ghanem, A.; Sergis, K.; Javed, F. Role of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the treatment of aggressive periodontitis: A systematic review. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2016, 13, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Qadri, T.; Ahmed, H. B.; Al-Hezaimi, K.; Corbet, F. E.; Romanos, G. E. Is photodynamic therapy with adjunctive non-surgical periodontal therapy effective in the treatment of periodontal disease under immunocompromised conditions? J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pakistan 2013, 23, 731–736. [CrossRef]

- Sgolastra, F.; Petrucci, A.; Gatto, R.; Marzo, G.; Monaco, A. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2013, 28, 669–682. [CrossRef]

- Sgolastra, F.; Petrucci, A.; Severino, M.; Graziani, F.; Gatto, R.; Monaco, A. Adjunctive photodynamic therapy to non-surgical treatment of chronic periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2013, 40, 514–526. [CrossRef]

- Atieh, M. A. Photodynamic therapy as an adjunctive treatment for chronic periodontitis: A meta-analysis. Lasers Med. Sci. 2010, 25, 605–613. [CrossRef]

- Azarpazhooh, A.; Shah, P. S.; Tenenbaum, H. C.; Goldberg, M. B. The effect of photodynamic therapy for periodontitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 4–14. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, J. M.; Theodoro, L. H.; Bosco, A. F.; Nagata, M. J.; Bonfante, S.; Garcia, V. G. Treatment of experimental periodontal disease by photodynamic therapy in rats with diabetes. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 2156–2165. [CrossRef]

- Prates, R. A.; Yamada, A. M.; Suzuki, L. C.; França, C. M.; Cai, S.; Mayer, M. P.; Ribeiro, A. C.; Ribeiro, M. S. Histomorphometric and microbiological assessment of photodynamic therapy as an adjuvant treatment for periodontitis: A short-term evaluation of inflammatory periodontal conditions and bacterial reduction in a rat model. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2011, 29, 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, A. C.; Suaid, F. A.; de Andrade, P. F.; Oliveira, F. S.; Novaes, A. B., Jr.; Taba, M., Jr.; Palioto, D. B.; Grisi, M. F.; Souza, S. L. Adjunctive effect of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy to nonsurgical periodontal treatment in smokers: A randomized clinical trial. Lasers Med. Sci. 2015, 30, 617–625. [CrossRef]

- Savović, J.; Turner, R. M.; Mawdsley, D.; Jones, H. E.; Beynon, R.; Higgins, J. P. T.; Sterne, J. A. C. Association Between Risk-of-Bias Assessments and Results of Randomized Trials in Cochrane Reviews: The ROBES Meta-Epidemiologic Study, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 187, Issue 5, May 2018, Pages 1113–1122. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx344.

- Lulic, M.; Leiggener Görög, I.; Salvi, G. E.; Ramseier, C. A.; Mattheos, N.; Lang, N. P. One-year outcomes of repeated adjunctive photodynamic therapy during periodontal maintenance: A proof-of-principle randomized-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2009, 36, 661–666. [CrossRef]

- Moro, M. G.; de Carvalho, V. F.; Godoy-Miranda, B. A.; Kassa, C. T.; Horliana, A. C. R. T.; Prates, R. A. Efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) for nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease: A systematic review. Lasers Med. Sci. 2021, 36, 1573–1590. [CrossRef]

- Malgikar, S.; Harinath, R.; Vidya, S.; Satyanarayana.; Vikram, R.; Julieta, J. Clinical effects of photodynamic and low-level laser therapies as an adjunct to scaling and root planing of chronic periodontitis: A split-mouth randomized controlled clinical trial. Indian Journal of Dental Research, Mar–Apr 2016, 27, 121-126. |. [CrossRef]

- Annaji, S., Sarkar, I., Rajan, P., Pai, J., Malagi, S., Bharmappa, R., Kamath, V. Efficacy of Photodynamic Therapy and Lasers as an Adjunct to Scaling and Root Planing in the Treatment of Aggressive Periodontitis - A Clinical and Microbiologic Short Term Study. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research. JCDR. 2016, 10, ZC08–ZC12. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/13844.7165.

- Lui, J.; Corbet, E. F.; Jin, L. Combined photodynamic and low-level laser therapies as an adjunct to nonsurgical treatment of chronic periodontitis. J. Periodontal Res. 2011, 46, 89–96. [CrossRef]

- Damante CA. Laser parameters in systematic reviews. J Clin Periodontol. 2021 48, 550-552. Epub 2021 Jan 31. PMID: 33522004. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.; Greghi, S. L. A.; Sant'Ana, A. C. P.; Zangrando, M. S. R.; Damante, C. A. Multiple Sessions of Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy Improve Periodontal Outcomes in Patients with Down Syndrome: A 12-Month Randomized Clinical Trial. Dentistry journal, 2025, 13, 33. [CrossRef]

| Patient profile | Number of articles (n) | Reference |

| Diabetes | 5 | [9,10,11,12,13] |

| Furcation lesion | 1 | [14] |

| Smokers | 3 | [15,16,17] |

| Periodontitis | 9 | [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26] |

| Residual periodontal pockets | 3 | [27,28,29] |

| Different patient profiles (Obesity and HIV) | 2 | [30] (Obesity); [31] (HIV) |

| Authors, year and participant (n) | wavelength | Laser parameters | Optic fiber | Concentration of dye | Repetition | Main results |

| Cunha et al. (2024) (n=38) [9] | 650 | 100mW/80s | Optic fiber (d=600μm) | 10 mg/ml | 3 sessions | SRP group presented greater values of PD (p<0.05). There was a significant reduction of TNF-α in crevicular fluid of patients treated by aPDT (p<0.05) |

| Rodrigues et al. (2023) (n=14) [18] | 660 | 100mW/0.25 mW/cm² / 14.94 J/cm² /10s | NR | 1% | 2 sessions | aPDT promoted better results of PD after 3 months. There was 18% less probability of presenting a final PD > 4 mm compared to SRP. |

| Cláudio et al. (2021) ** (n=34) [10] | 660 | 157 J/ cm²/100 mW/50s | Optic fiber (d=0.03 cm²) | 10 mg/ml | 3 sessions | aPDT presented a reduction of NRP after 3 and 6 months (p<0.05). |

| Derikvand et al. (2020) (n=50) [19] | 660 | 150 mW/ 60s | NR | 100 μg/mL | Single | Reduction in PD at aPDT group after 3 and 6 months, in comparison to SRP group (p<0.01) |

| Katsikanis et al. (2020) ** (n=21) [16] |

670 | 350 mW/ 0.445 W/ cm²/ 120s | Diameter - 1 cm | 1% | 3 sessions | Only PI presented statistically significant differences at baseline (p=0.038) in SRP group. |

| Alahmari et al. (2019) (n=83) [15] | 660 | 150 mW/75 mW/cm²/60 s | Optic fiber (d=600μm) | 0.005% | Single | Only PI in SRP group presented statistically significant differences (p< 0.05) after 1 month. PD and CAL were greater in S group When compared to NS group. |

| Barbosa et al. (2018) (n=12) [11] | 660 | 40mW/120s/4.8J | - | 10 mg/ml | Single | There was no difference between groups for PD and CAL (p >0.05). aPDT group presented better results for PI after 1 month and BOP after 6 months. |

| Andere et al. (2018) (n=36) [20] | 660 | 60 mW / 129 J/cm² / 60s | Optic fiber | 10 mg/ml | Single | Group UPD+CLM+aPDT presented greater CAL values when compared to UPD and UPD+aPDT (p < 0.05). |

| Theodoro et al. (2018) (n=51) [17] | 660 | 100mW/160 J/cm2/48s | Optic fiber (d= 0.03 cm2) | 10 mg/ml | 3 sessions | After 6 months, group MTZ + AMX and aPDT presented lower PD, greater CAL and less BOP, but without statistical significant differences between SRP and aPDT. |

| Vohra et al. (2018) ** (n=52) [30] | 670 | 150mW/60 s | Optic fiber (d=0.6 mm) | 0.005% | Single | PI was better for SRP group after 1.5 and 3 months (p<0.05). |

| Al-Askar et al. (2017) * (n=70) [12] | 670 | 150 mW/60 s | NR | 0.005% | Single | There was no difference between groups and periods. There was no difference in CBL in all groups at 3 and 6 months. |

| Andrade et al. (2017) (n=28) [21] | 660 | 40mW/90s/90J/cm² | Optic Fiber (d=200μm) | 0.01% | Single | There were no differences between groups. There was a reduction in IL-8 in aPDT group after 3 months (p=0.04). |

| Pulikkotil et al. (2016) (n=20) [22] |

Red LED (628Hz) | 628 Hz/ 20s | NR | NR | Single | There was a significant reduction in BOP after 3 months in aPDT group. (p<0.01). There was no differences in A.a. quantification. |

| Campanile et al. (2015) (n=28) [27] | 670 | 280 mW, ±0.2 dB | Optic fiber | NR | Twice a week | aPDT group presented reduction in PD after 3 and 6 months. There was a reduction in C reactive protein. There were no microbiological differences. |

| Kolbe et al. (2014) (n=22) [28] | 660 | 0.06W, 129J/cm², 60s | Optic fiber (d=600μm) | 10mg/ml | Single | There were no statistically significant differences in clinical parameters. Reduction in Pg., Aa., and inflammatory cytokines. |

| Franco et al. (2014) ** (n=15) [23] | 660 | 0.06W/cm², 90s, 5.4Jcm² | Optic fiber (d=0.4mm) | 0.01% | Once a week - total of 4 sessions | Reduction in BOP in aPDT group (p<0.05). Increase in RANK/OPG and FGF-2 levels. |

| Betsy et al. (2014) (n=88) [24] | 655 | 1W, 0.06W/cm²,60s | Optic fiber (d=0.5mm) | 10mg/ml | Single | Significant reductions in PD, CAL, BOP, PI and GI for aPDT group (p<0.05). |

| Luchesi et al. (2013) (n=37) [14] | 660 | 0.06W, 129J/cm², 60s | Optic fiber (d=600μm) | 10mg/ml | Single | There were no statistically significant differences in clinical parameters. Reduction in Pg., Aa., and inflammatory cytokines up to 6 months. |

| Dilsiz et al. (2013) (n=24) [25] | 808 | 0.1W, 6J, 60s | Optic fiber (d=300μm) | 1% | Single | aPDT group presented reduction in PD and CAL after 6 months. (p<0.05). |

| Campos et al. (2013) (n=13) [29] | 660 | 0.06W, 129J/cm², 60s | Optic fiber (d=600μm) | 10mg/ml | Single | aPDT group presented reduction in PD, CAL, and BOP after 6 months. |

| Noro Filho et al. (2012) (n=12) [31] |

660 | 0.03W, 0.428W/cm², 57.14J/cm², 133s | Optic fiber (a= 0.07 cm²) | 0.01% | Single | aPDT presented reduction in PD after 6 months, BOP after 3 and 6 months. There were no differences in microbiological parameters. |

| Giannelli et al. (2012) (n=26) [26] | 635 | 0.1W, 120s (60s inside + 60s outside) d= 0.6mm | Optic fiber (d=0.6mm) | 0.3% | 4 to 10 sessions | aPDT presented reduction in PD, CAL, BOP and spirochetes after 12 months. |

| Al-Zahrani et al. (2009) (n=45) [13] | 670 | 60s | NR | 0.01% | Single | There were no significant differences. |

| Evaluation time (months) | Number of articles (n) | Reference |

| 0, 1, 3 e 6 | 3 | [9,11,24] |

| 0 e 3 | 4 | [13,18,23,29] |

| 0, 3 e 6 | 8 | [10,12,14,16,17,20,27,28] |

| 0, 1,5 3 e 6 | 2 | [19,31] |

| 0, 1 e 3 | 2 | [15,22] |

| 0, 1,5 e 3 | 1 | [30] |

| 0, 3 e 12 | 1 | [21] |

| 0 e 6 | 1 | [25] |

| 0 e 12 | 1 | [26] |

| Randomization process | ||

| Method used | Number of articles (n) |

Reference |

| Coin toss | 3 | [15,22,30] |

| Computer-generated list | 8 | [13,14,20,25,27,28,29,31] |

| Computer-generated numbers | 1 | [9] |

| Random numbers | 1 | [24] |

| Online randomizer | 3 | [10,17] |

| Deck of cards | 1 | [18] |

| Lottery draw | 1 | [19] |

| Randomization chart | 1 | [16] |

| Computer software | 2 | [11,21] |

| Drawing lots from an opaque bag | 1 | [12] |

| Sealed opaque envelopes | 1 | [26] |

| Not reported | 1 | [23] |

| Authors | Patient profile | PD | BOP (%) | CAL | PI (%) | GI | GR |

| Cunha et al. (2024) [9] | Periodontitis/Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus | SRP (p<0.05) |

NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Rodrigues et al. (2023) [18] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p=0.02 at 3 months |

- | NHE | - | - | NHE |

| Cláudio et al. (2021) [10] | Diabetes Mellitus | NHE | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | NHE |

| Derikvand et al. (2020) [19] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p<0.01) at 3 and 6 months | - | - | NHE | NHE | - |

| Alahmari et al. (2019) [15] | Smokers | NHE | NHE | NHE | SRP (p<0.01) at 1 month | - | - |

| Katsikanis et al. (2020) [16] | Moderate smoker | NHE | NHE | NHE | SRP (p=0.038) at baseline | - | - |

| Barbosa et al. (2018) [11] | Periodontitis / Diabetes Mellitus | NHE | aPDT (p=0.05) at 6 months | NHE | aPDT (p=0.02) only at 1-month follow-up | - | - |

| Andere et al. (2018) [20] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 months | NHE | NHE | - | - | NHE |

| Theodoro et al. (2018) [17] | Smokers | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - | - |

| Vohra et al. (2018) [30] | Obesity/Periodontitis | NHE | NHE | NHE | SRP (p<0.01) at 1.5 months and 3 months | - | - |

| Al-Askar et al. (2017) [12] | Pre-diabetes | NHE | NHE | - | NHE | - | - |

| Andrade et al. (2017) [21] | Periodontitis | NHE | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Pulikkotil et al. (2016) [22] | Periodontitis | NHE | aPDT (p<0.01) at 3 months | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Campanile et al. (2015) [27] | Residual pockets | aPDT (p=0.04) at 3 months | NHE | NHE | NHE | NHE | - |

| Kolbe et al. (2014) [28] | Residual pockets | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - | - |

| Franco et al. (2014) [23] | Periodontitis | NHE | aPDT (p<0.05) | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Betsy et al. (2014) [24] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 and 6 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 1 and 3 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 and 6 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 2 weeks | aPDT (p<0.05) at 1 and 3 months | NHE |

| Luchesi et al. (2013) [14] | Furcation Class III | NHE | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Dilsiz et al. (2013) [25] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p<0.05) at 6 months | NHE | aPDT (p<0.05) at 6 months | NHE | NHE | - |

| Campos et al. (2013) [29] | Residual pockets | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 months | - | - | - |

| Noro Filho et al. (2012) [31] | HIV | aPDT (p<0.05) at 6 months | aPDT (p<0.05) at 3 and 6 months | NHE | NHE | - | NHE |

| Giannelli et al. (2012) [26] | Periodontitis | aPDT (p<0.001) at 12 months | aPDT (p<0.001) at 12 months | aPDT (p<0.001) at 12 months | |||

| Al-Zahrani et al. (2009) [13] | Diabetes Mellitus | NHE | NHE | NHE | NHE | - | - |

| Authors and year | Selected articles and study participants (n) | Conclusion |

| Jervøe-Storm et al. (2024) [32] | 50 selected articles (n=1407) | The available evidence is quite limited, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the superior clinical benefits of aPDT as an adjunctive therapy in the active treatment or maintenance of periodontitis. Furthermore, the data suggest that the observed improvements may be too small to hold clinical relevance. To enhance the reliability of these findings, it is essential to conduct large, well-designed, and rigorously evaluated randomized controlled trials (RCTs), taking into account the variability of outcomes over time. |

| Salvi et al. (2020) [4] | 17 selected articles (n=370) | The available evidence on adjunctive therapy with lasers and aPDT is limited to a small number of controlled studies, with notable variability in study designs. |

| Vohra et al. (2016) [33] | 7 selected articles (n=218) |

In the use of aPDT for the treatment of aggressive periodontitis, the authors concluded that this therapeutic approach may be effective as an adjunct to SRP. However, further randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings. |

| Javed et al. (2013) [34] | 6 selected articles (n= 615 and 270*) | aPDT was analyzed as an adjunct to non-surgical periodontal therapy in immunocompromised patients. After review, only six articles were found, of which only one was a randomized clinical trial; the others were laboratory studies conducted in rats. Various factors, such as smoking and poor oral hygiene, may interfere with the outcomes, making it difficult to assess the effectiveness of this therapy. In conclusion, further studies are needed. |

| Sgolastra et al. (2013) [35] | 7 selected articles (n=261) |

After evaluating seven articles, the clinical outcomes were found to be modest, indicating a lack of scientific evidence and the need for further studies to assess the efficacy of aPDT as an adjunct to SRP. |

| Sgolastra et al. (2013) [36] | 14 selected articles (n=389) |

A more rigorous systematic review was recently published, including 14 studies, but without promising results. aPDT may have short-term effects, as the evidence does not indicate significant differences after six months. Therefore, the authors recommend conducting additional clinical trials with long-term follow-up. |

| Atieh, 2010 [37] | 4 selected articles (n= 161) |

The analysis included only four articles, with a post-therapy follow-up of three weeks. The results showed a clinical gain of 0.29 mm in attachment level and a reduction of 0.11 mm in probing depth. The authors concluded that the use of aPDT may be beneficial, but they cautioned about the limitation of the small number of studies included. |

| Azarpazhooh et al. (2010) [38] |

5 selected articles (n=74 and 62**) |

The review included five studies, three of which were similar to Atieh, 2010, without distinguishing the types of periodontitis between them, considering studies with follow-up at 3 and 6 months. The results showed a minimal gain in clinical attachment (0.34 mm) and a reduction in probing depth (0.25 mm). The authors concluded that aPDT was not shown to be more effective. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).