1. Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which rapidly spreads worldwide and was declared a Global Pandemic on March 11

th, 2020 [

1,

2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), SARS-CoV-2 has already infected more than 777 million people worldwide, with more than 7 million deaths, leading to unprecedented disruptions in healthcare systems, economies, and daily life [

3]. Brazil was among the nations most severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and there are more than 39 million confirmed cases with 716.075 deaths [

4]. The COVID-19 symptoms range from mild respiratory illness to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and multiple organ failure (MOF), particularly in vulnerable populations such as the elderly and those with underlying medical conditions [

5,

6,

7,

8]. In addition, several patients are experiencing long-term sequelae after resolution of acute disease, referred to Post COVID-19 condition (PCC) [

9,

10,

11]. The symptoms can persist for more than four weeks following the initial infection and may last for several years, encompassing a range of physical, cognitive, and psychological impairments [

12,

13]. The estimated global PCC prevalence ranges from 6% to 50%, affecting over 65 million individuals worldwide [

11,

14,

15,

16].

The dysregulation of the immune system, with massive production of inflammatory cytokines, has been associated with the COVID-19 progression to severe cases, ARDS development, coagulation dysfunction, and MOF [

17,

18]. The immunopathogenesis of COVID-19 involves the IFN-I delayed response, in addition to the activation of the inflammasome, extrusion of neutrophils extracellular traps (NETs) in the lung tissue, PANoptosis induced by the TNF and IFN-γ synergistic action, in addition to viral envelope TLR-2-engagement and proinflammatory cytokines induction [

19,

20,

21]. Activated inflammatory monocytes and macrophages secrete massive amounts of IL-6 and other inflammatory cytokines, contributing to the cytokine storm [

22]. CD4 Th1 T lymphocytes involved in the antiviral response present a cellular exhaustion phenotype and many cytotoxic CD8 T lymphocytes undergo apoptosis, failing to eliminate viral reservoirs [

19]. Furthermore, a depletion of germinal centers in the spleen and lymph nodes was observed due to cell death driven by excess TNF and IFN-γ, favoring the lymphopenia observed in patients and interfering with the antibody immune response [

19,

24].

The SARS-CoV-2 infection can compromise the immune function, leading to an inflammatory state that can persist for months in PCC patients [

10,

25]. Studies have shown that PCC patients presented increased systemic inflammatory cytokines (interferons and IL-6) and autoantibodies during months after acute COVID-19 [

25,

26]. Furthermore, the reduction of persistent PCC manifestations is associated with the immune function reestablishment within 2 years post-infection [

27].

The patient's immunocompetence can determine the immune response to SARS-CoV-2, and both, the immune and the clinical responses, can be impacted by the intestinal microbiota balance [

28]. There is a bidirectional connection across the gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosal compartments which influences the healthy or pathological immunity to SARS-CoV-2 [

29,

30,

31,

32]. The gut bacteriome plays a pivotal role in this axis, influencing both local and systemic immune responses. Disruptions in the gut microbiota composition and function have been implicated in the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, and more recently, in COVID-19 [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Also, the microbiota imbalance can compromise the integrity of the intestinal barrier, leading to increased gut permeability, bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, potentially triggering systemic inflammation and contributing to inflammatory diseases and COVID-19 severity [

37,

38,

39].

Emerging evidence highlights the gut-lung axis as a critical factor in respiratory health [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. There are no studies evaluating alterations in the gut microbiota in acute COVID-19 in the Brazilian population, nor evaluating the impact of this possible imbalance in the gut permeability and systemic production of inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate alterations in the gut bacteriome SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, and correlate them with gut permeability and systemic inflammation. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the gut-lung axis may offer novel strategies for preventing and treating pulmonary diseases and COVID-19 sequelae.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Ethical Aspects and Patients’ Enrollment

This observational study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee from Sao Paulo State University (Process number 4,310,336/2020). All participants, over 18 years of age, signed an informed consent form, and peripheral blood samples were collected, and fecal samples were requested and delivered within 5 days. The patients included in this study were enrolled between October 2020 and December 2021 in two different hospitals in Brazil (Ribeirao Preto Santa Casa and Botucatu Clinical Hospital), in addition to Sao Jose do Rio Preto Institute of Hematology Laboratory.

Two hundred and twenty unvaccinated SARS-CoV-2-infected patients were included based on their laboratory-confirmed oropharyngeal/nasopharyngeal swabs by RT-qPCR method. Clinical-laboratory data were collected, including gender, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), disease severity, symptoms, sequalae, comorbidities, medications, hospitalizations, ICU time, chest radiograph, and C-reactive protein levels. Exclusion criteria for control subjects included anti-inflammatories, immunosuppressants, antibiotics, and vaccination in the last 30 days, as well as inflammatory bowel diseases and chronic diarrheas.

2.2. Bacteriome Characterization by 16S Sequencing

DNA was obtained from 200 mg from fecal samples by using QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA), according to manufacturer protocol. The analysis of bacteriome was based on the sequencing of 16SV6 rDNA amplicons, in the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine™, following a clonal amplification (emulsion PCR). Pooled barcoded amplicons were attached to the surface of ion sphere particles (ISPs) using the IonPGM™. Template OT2 400 kit and the corresponding protocol. Emulsion PCR was carried out in the Ion OneTouch™ 2 System. After amplification quality checking, ISP enrichment was performed in the Ion OneTouch™ Enrichment System. Sequencing primers were then annealed to the ISPs’ single stranded DNA, following the Ion PGM sequencing 400 kit protocol. Low quality and polyclonal sequence reads, as well as primers and barcodes were filtered out and the 16SV6 rDNA sequences were available as a FastQ file. The raw data is deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA1189098.

2.3. Zonulin and Secretory Immunoglobulin A Quantification by ELISA Assays

Approximately 5 mL of peripheral blood were collected from participants in EDTA k2 tube and the plasma was separated by centrifugation at 1,372 g, for 10 min, 4°C. Plasma zonulin measurement were carried out by using the Human Zonulin ELISA Kit (Elabscience, Bethesda, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The fecal secretory immunoglobulin A (sIgA) was quantified by the commercial Human IgA ELISA kit (Elabscience, Bethesda, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For both ELISA assays, the optical density (OD) was read at 450 nm in a spectrophotometer (BioTek EPOCH2NS microplate). The calibration curves were constructed in Excel spreadsheets using the formula y = ax + b, where x and y were two dependent variables (OD and concentration). The concentrations were calculated by converting the OD (variable x) into ng/mL (variable y).

2.4. Cytokine Quantification by Cytometric Bead Array and ELISA Assay

Approximately 5 mL of peripheral blood were collected from participants in EDTA k2 tube and the plasma was separated by centrifugation at 1,372 g, for 10 min, 4°C. Plasma samples were used for cytokine quantification by using cytometric bead array (Human Th1/Th2/Th17 Kit, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The levels of interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) were detected by a flow cytometer (FACSCanto™ II, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Results were analyzed by BDFCAP array™ software and were expressed in pg/ml. The Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) cytokine was measured by TGF-β1 sandwich-ELISA Kit (Elabscience, Bethesda, MD, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The absorbance was read at 450 nm, and the results are presented as ng/mL.

2.5. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analyses

The sequence initial quality was assessed by using the FastQC program (v.0.11.9) [

40]. The reads were then submitted to the DADA2 pipeline (v.1.22.0) using the corresponding package in the R statistical program (v.4.1.2) (R Core Team, 2023) [

41]. The quality control steps included size truncation (truncLen = 250), leading trimming removal (trimLeft = 10) and quality filtering (maxEE = 2) by the “filterAndTrim” function. Amplicon variant sequences (ASVs) were identified for each sample, and possible chimeric sequences were filtered using the “removeBimeraDenovo” function. Taxonomic classification was performed by using the “assignTaxonomy” function, using the RDP reference database (v.18) [

42]. The ASVs were also aligned with BLAST against the NCBI RefSeq 16S rRNA database [

43].

The phylogenetic relationship between ASVs was established with the Neighbor-Joining algorithm using the "NJ" function and statistically validated by the bootstrap method with the "bootstrap.pml" function, both from the R package “phangorn” (v.2.10.0) [

44]. The counts, taxonomic annotations and the phylogenetic tree were exported in the “phyloseq” format (R package "phyloseq") (v.1.38.0) [

45]. The phyloseq object was transformed into compositional data by the "phyloseq_standardize_otu_abundance" function from the “metagMisc” package (v.0.04) for subsequent analyses [

46].

Sequencing coverage was assessed using rarefaction curves generated using the “amp_rarecurve” function from the “ampvis2” package (v.2.7.17) [

47]. For alpha diversity, observed richness and diversity indices (Shannon, Gini-Simpson and Faith's Phylogenetic Diversity) were estimated using the “alpha” function from the “microbiome” package (v.1.16.0) [

48]. Beta diversity was analyzed using the Bray-Curtis, Jaccard and UniFrac (Weighted and Unweighted) dissimilarity indices obtained using the “distance” function from the “phyloseq” package. The dispersion of samples within each group was also assessed.

The alpha diversity metrics, distance dispersion and relative abundances were compared using the Kruskal-Wallis test (

P < 0.05). When the data showed significance, the means were compared by the Wilcoxon post-hoc test paired at 5% probability (

P < 0.05). To assess the differences in beta diversity between the groups, Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) was used using the “adonis2” function of the “vegan” package (v.2.6.4) [

49]. The post-hoc analysis was performed with the “pairwise.adonis” function (R package “pairwiseAdonis”) (v.0.4) [

50]. The multidimensional distances were ordered by Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA). The graphical representations of the analyses were generated in the “R” program using the “ggplot2” package (v.3.5.1) [

51].

3. Results

3.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Infected Patients

A total of 221 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 were included in the analysis, of which, 79 were in the acute phase of the disease and 142 in the post-COVID-19 condition (PCC). In acute COVID-19 group, 58% of patients were female, 42% male, with mean age of 52 years, and classified in mild (n = 28), moderate (n = 41) and severe (n = 10). In PCC group, 62% of patients were female, 38% male, with mean age of 41 years, and classified in mild (n = 114), moderate (n = 13) and severe (n = 15). The control group (CTL) consisted of 85% female and 15% male, with mean age of 44 years. The C-reactive protein (CRP) concentrations were significantly higher in acute COVID-19, when compared with PCC patients (

P < 0.001).

Table 1 summarizes the clinical and demographic aspects of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and control subjects.

3.2. Bacteriome Signature in Patients Infected with SARS-CoV-2 Virus

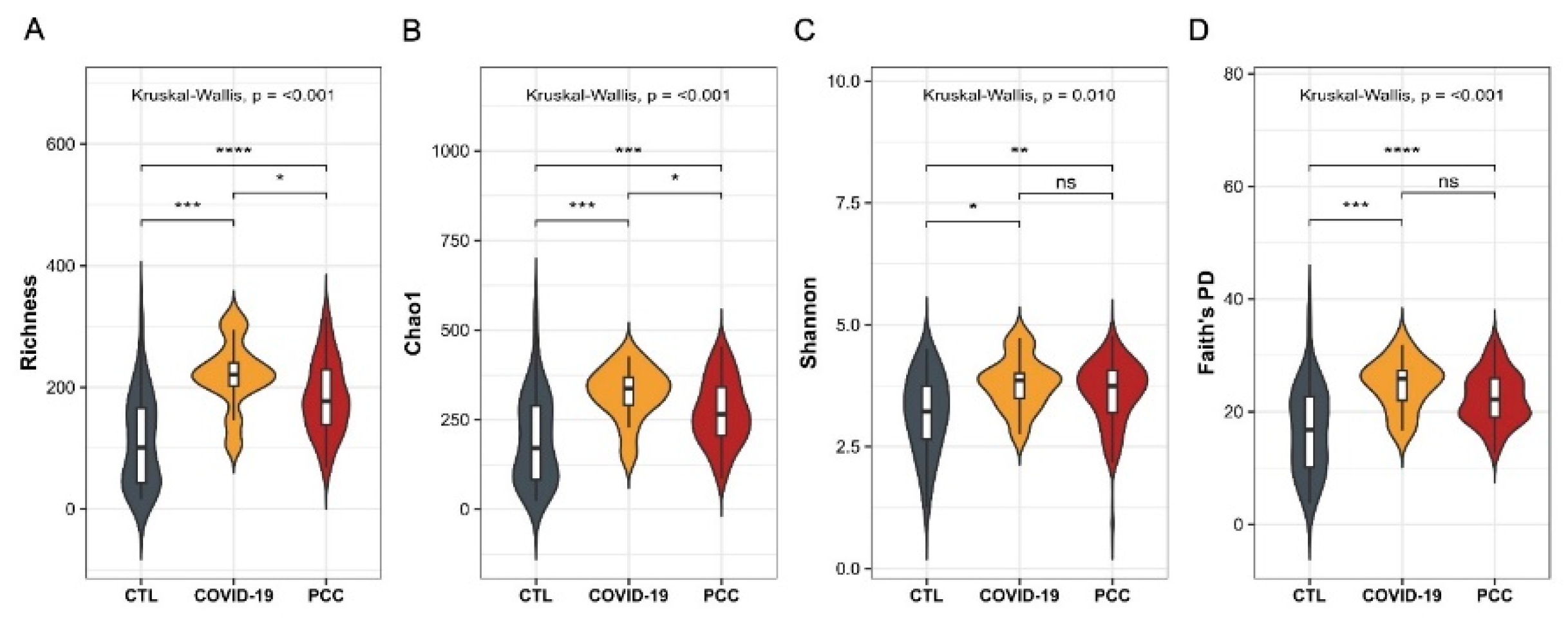

To investigate significant changes in the gut bacteriome of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, we performed the 16S sequencing and evaluated the alpha and beta diversities. For alpha diversity, observed richness and diversity indices were estimated. We observed significant differences (

P < 0.001) in Richness, Chao1, Shannon (

P = 0.010), and Faith's phylogenetic diversity metrics in patients’ samples (acute COVID-19 and PCC) when compared with control group (

Figure 1A-D). We also detected significant differences (

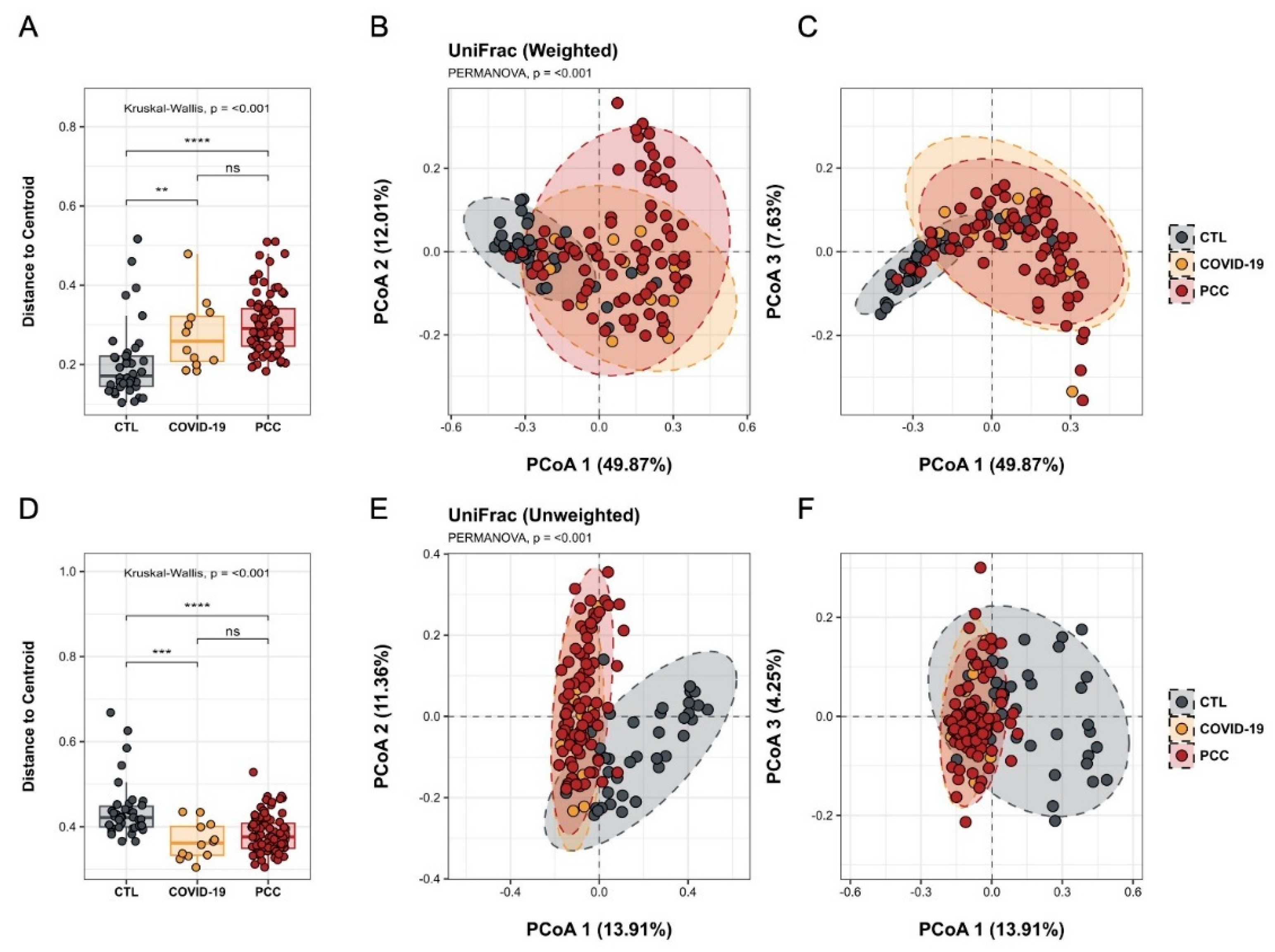

P < 0.001) in microbial communities found in acute COVID-19 and PCC patients, compared with controls, with different clusters in Principal Coordinate Analysis (PCoA) (

Figure 2 A-F).

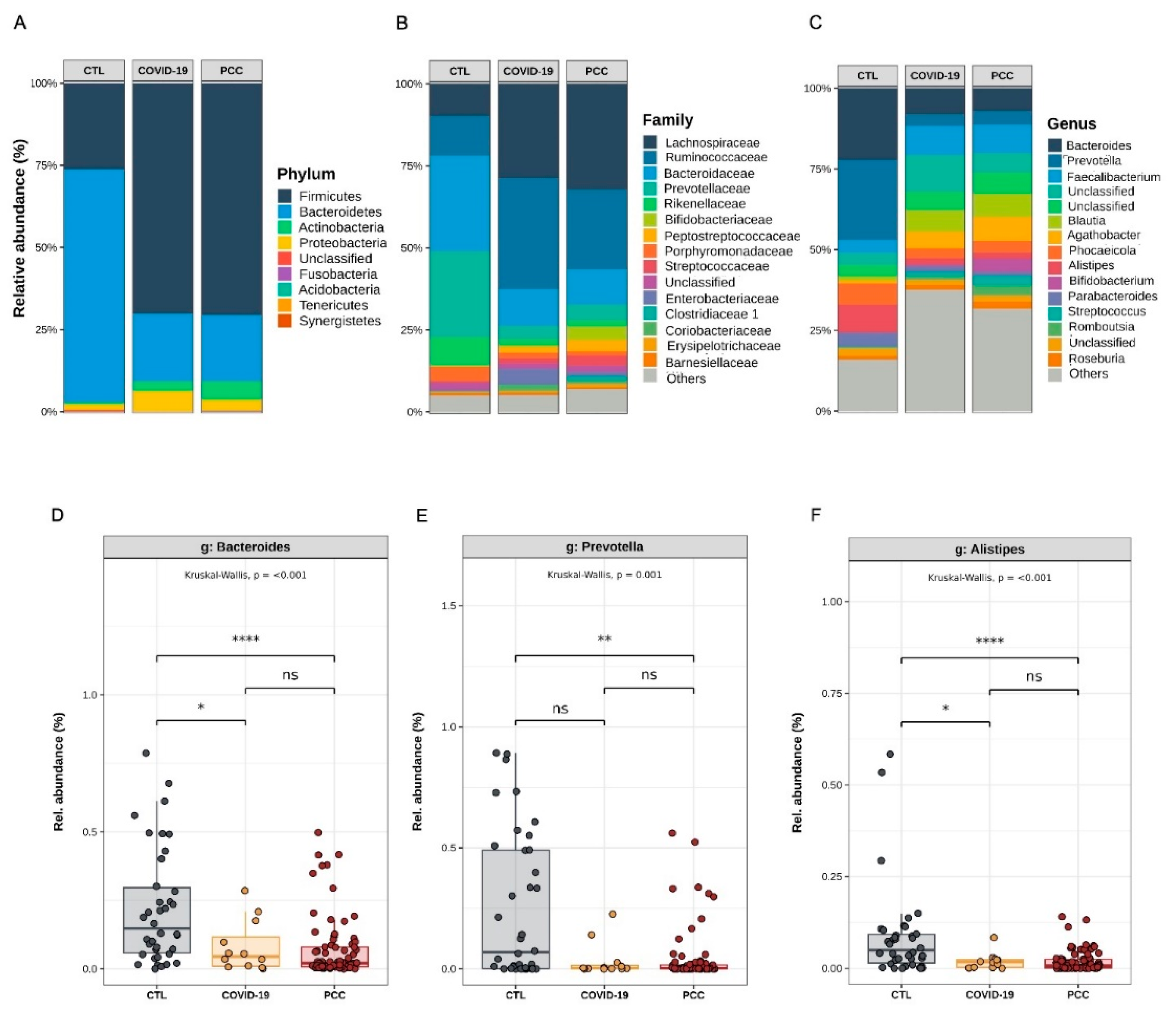

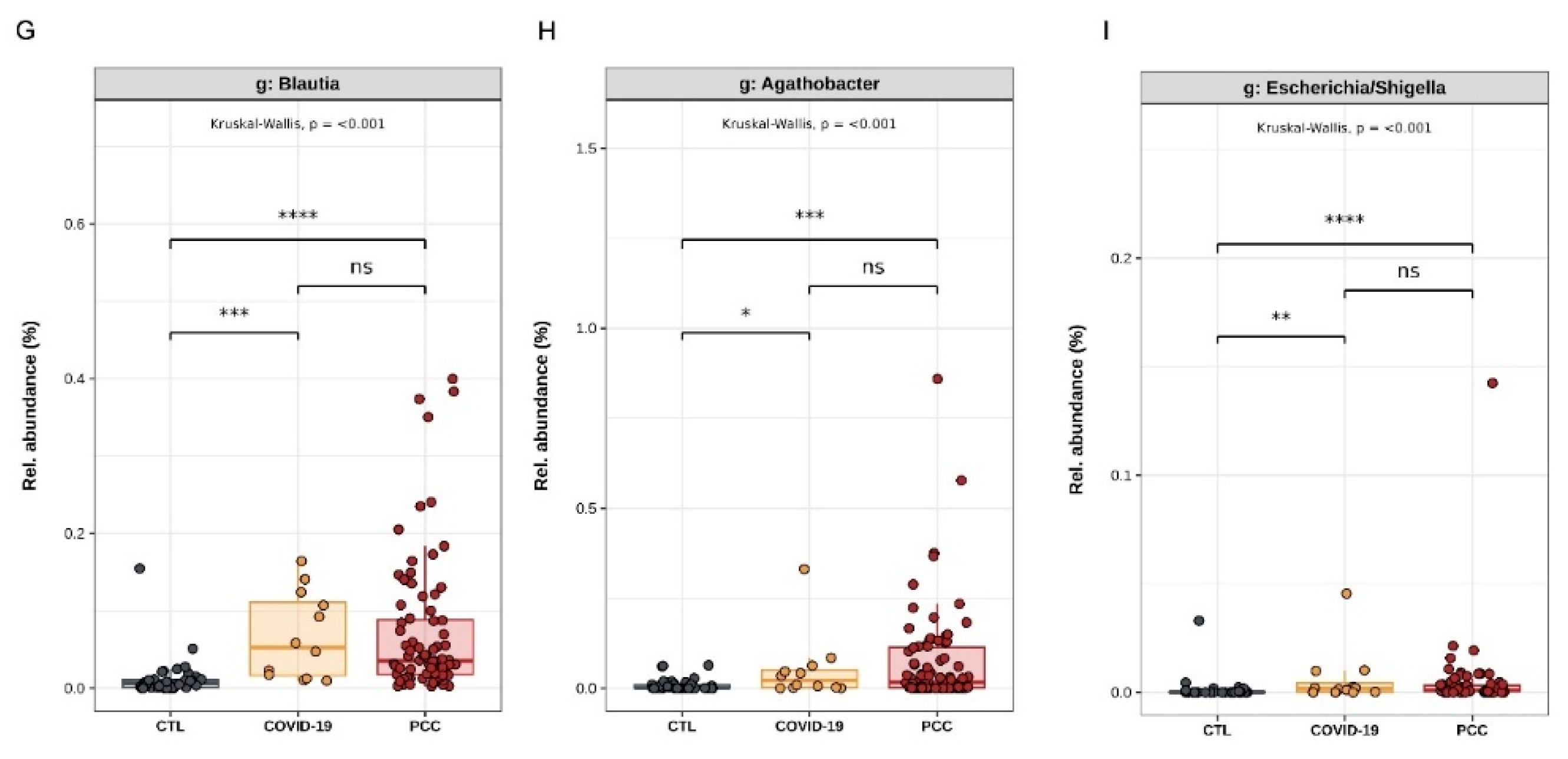

Regarding differential abundance analysis and taxonomic distribution, we observed significant differences (

P < 0.001) among acute COVID-19, PCC and controls in Bacteroidota (formerly Bacteroidetes) (22.4%

vs. 21.9%

vs. 73.3%) and Bacillota phyla (formerly Firmicutes) (67.9%

vs. 68.6%

vs. 24.2%) (

Figure 3A). Decreased

Prevotellaceae (4.4%

vs. 5.1%

vs. 31.2%) and

Bacteroidaceae (12.3%

vs. 11.7%

vs. 28.7%) abundances were detected in COVID-19 and PCC groups, as well as increased

Ruminococcaceae (31.5%

vs. 24.9%

vs. 12.2%) and

Lachnospiraceae (28.8%

vs. 30.4%

vs. 8.9%), compared with control group. In addition,

Enterobacteriaceae family was also significantly increased (

P = 0.013) in acute COVID-19 group (4.6%

vs. controls 0.28%) (

Figure 3 B). Finally,

Bacteroides (8.9%

vs. 7.5%

vs. 21.6%)

, Prevotella (3.7%

vs. 4.5%

vs. 29.7%) and

Alistipes genera (2.0%

vs. 1.8%

vs. 5.4%) were significantly decreased in COVID-19 and PCC groups, and

Blautia (7.1%

vs. 6.4%

vs. 0.71%),

Agathobacter (4.1%

vs. 7.1%

vs. 0.85%) and

Escherichia-Shigella (0.64%

vs. 0.50%

vs. 0.19%) increased, compared with control subjects (

Figure 3C-I).

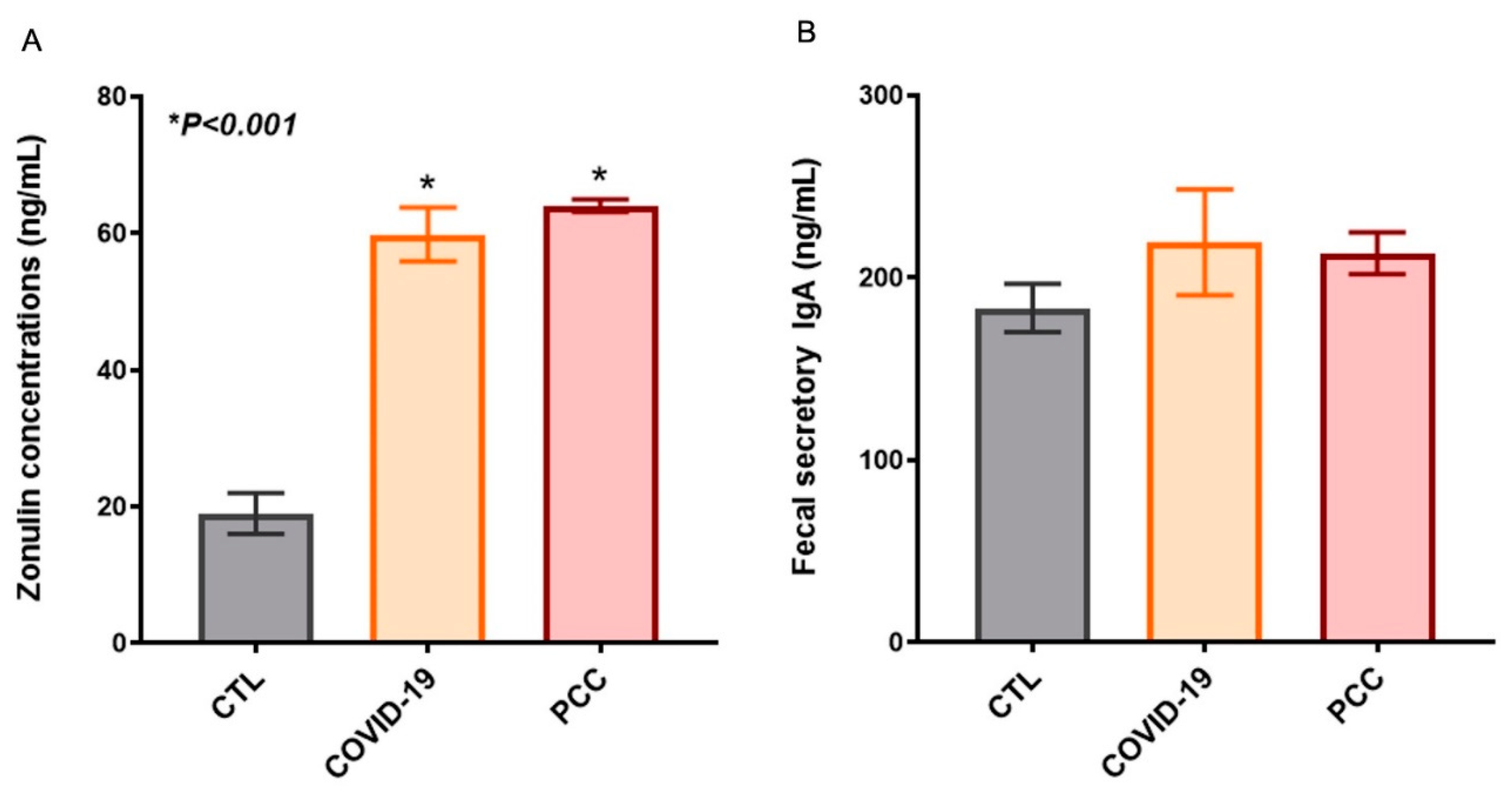

3.3. Increased Gut Permeability in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients

Since we detected significant changes in the intestinal bacteriome in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, we also checked the integrity of the gastrointestinal barrier by measuring plasma zonulin levels and fecal secretory IgA. We observed a significant increase (

P < 0.001) zonulin concentrations in acute COVID-19 (60 ± 3.9 ng/mL) and PCC patients (64 ± 0.9 ng/mL), when compared with control group (19 ± 3 ng/mL) (

Figure 4A). The secretory IgA concentrations in fecal samples from COVID-19 (220 ± 29 ng/mL) and PCC (214 ± 11 ng/mL) did not differ from control group (184 ± 13 ng/mL) (

Figure 4B).

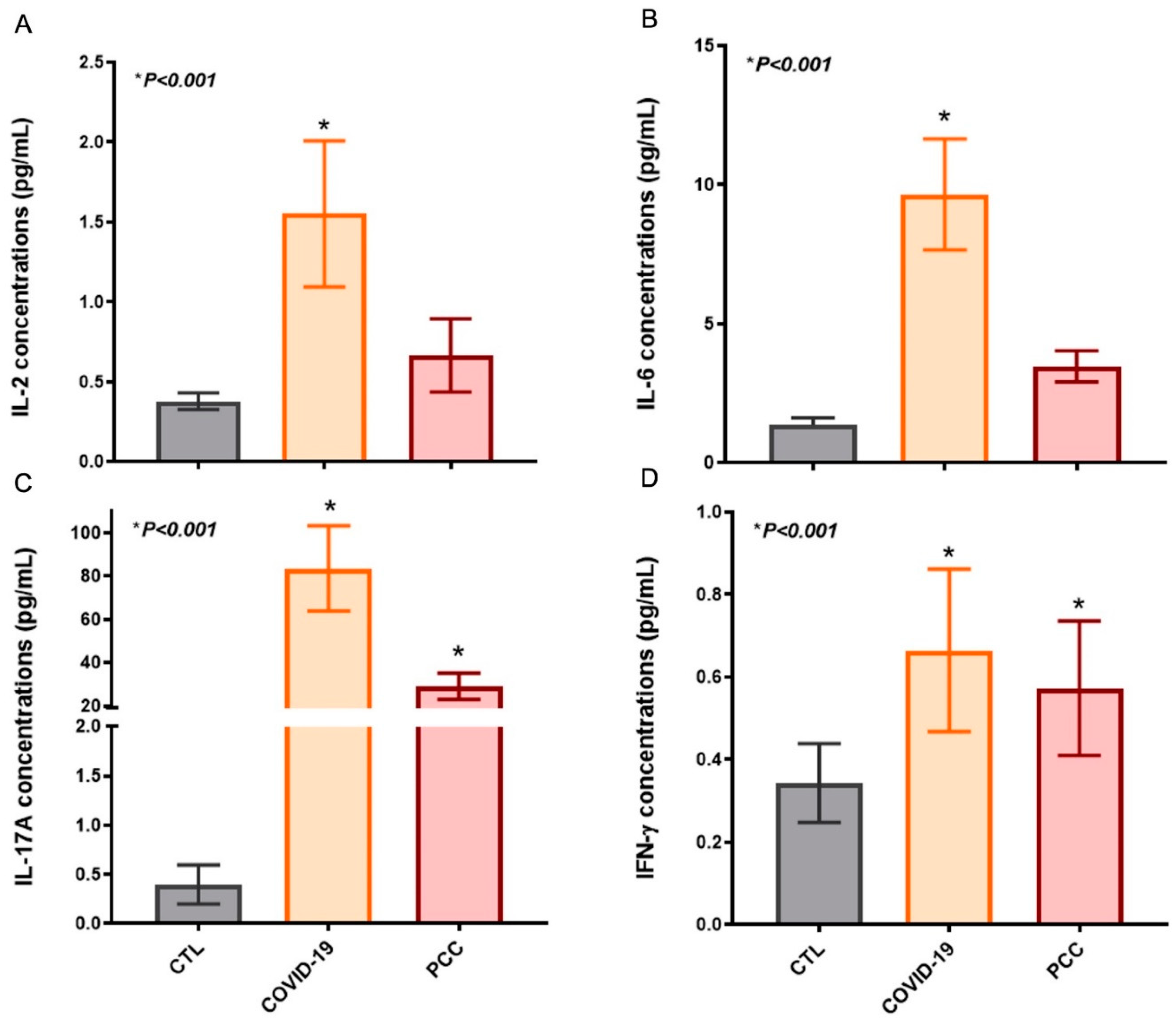

3.4. Increased Inflammatory Cytokines in SARS-CoV-2-Infected Patients

This In order to verify the systemic immunity in blood plasma samples, we quantified the IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-17A, IFN-γ, TGF-β and TNF concentrations in patients and healthy individuals. We detected significant differences in IL-2, IL-6, IL-17A and IFN-γ in acute COVID-19 (IL-2: pg/mL, IL-6: 9.7 ± 2.0, IL-17A: 84 ± 20, IFN-γ: 0.66 ± 0.20) and PCC (IL-2: pg/mL , IL-6: 3.5 ± 0.56, IL-17A: 29 ± 6.0, IFN-γ: 0.57 ± 0.16), when compared with controls (IL-2: pg/mL, IL-6: 1.4 ± 0.25, IL-17A: 0.40 ± 0.20, IFN-γ: 0.34 ± 0.09) (

Figure 5). No differences were found in IL-4, IL-10, TGF-β and TNF concentrations between SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and controls.

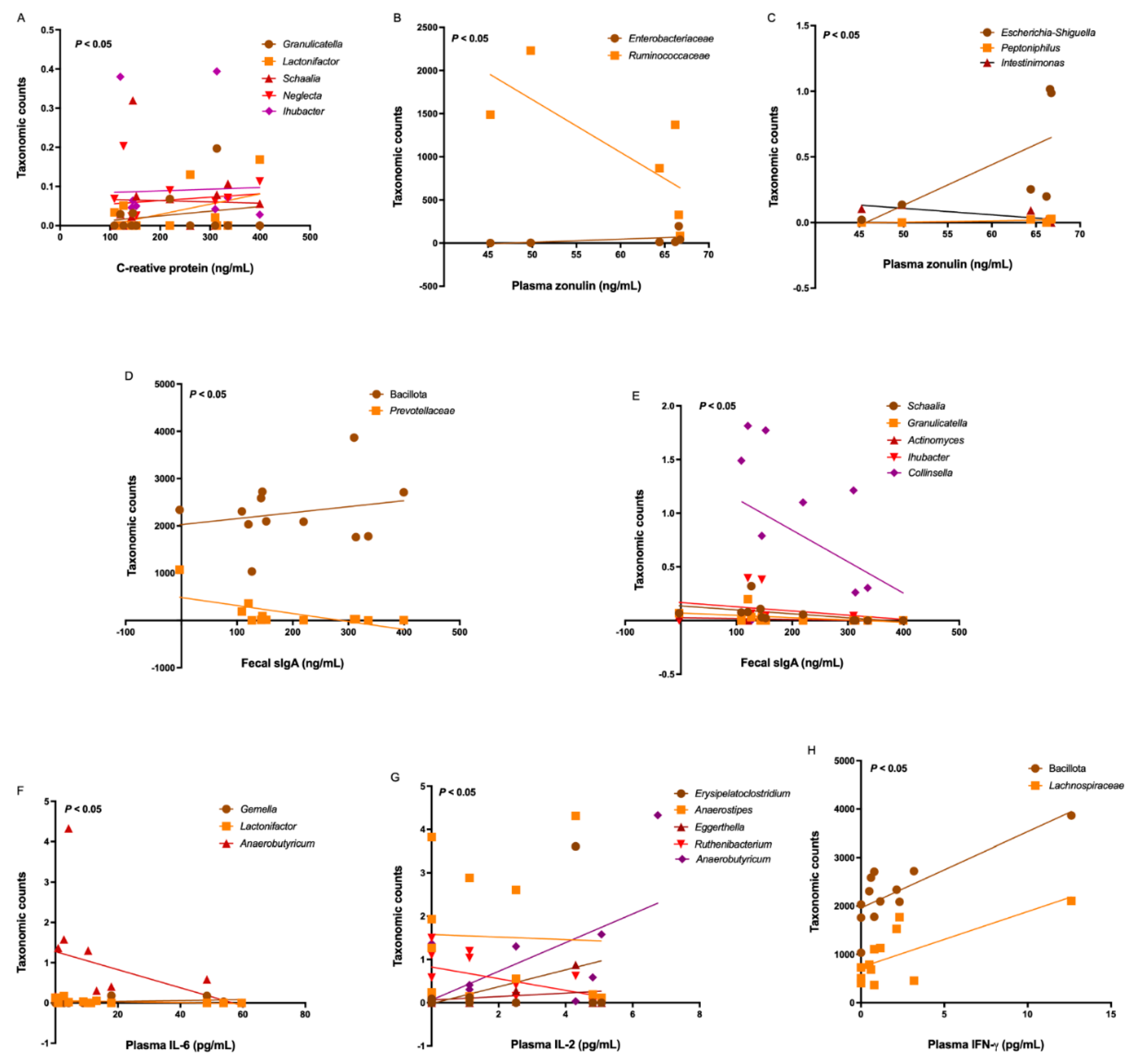

3.5. Correlations Among Bacteriome, Clinical Data, Gut Permeability, and Cytokines

Since we found significant differences in the gut bacteriome in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients, we investigated moderate-strong correlations between the bacterial taxonomic counts and clinical-laboratory data. No moderate-strong correlations between the bacterial taxonomic counts and clinical-laboratory data in PCC patients were found. On the other hand, some differentially increased genera in acute COVID-19 patients correlated with C-reactive protein levels, including

Schaalia (r = -0.87;

P < 0.001),

Ihubacter (r = -0.85;

P < 0.001),

Lactonifactor (r = 0.78;

P = 0.004),

Neglecta (r = 0.67;

P =0.014), and

Granulicatella (r = -0.54;

P =0.046). (

Figure 6A).

Regarding the gut permeability, some taxa differentially increased in acute COVID-19 patients correlated with zonulin concentrations, including

Enterobacteriaceae (r = 0.94;

P =0.008),

Ruminococcaceae (r = -0.88;

P =0.016),

Escherichia-Shiguella (r = 0.88;

P =0.016),

Peptoniphilus (r = 0.77;

P = 0.05), and

Intestinimonas (r = -0.92;

P = 0.011) (

Figure 6B-C). Although we found no differences in fecal secretory IgA levels between patients and controls, we observed some moderate-strong inverse correlations with some differentially increased taxa in acute COVID-19, including Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) (r = 0.54;

P = 0.035),

Prevotellaceae (r = -0.62;

P = 0.017),

Schaalia (r = -0.83;

P < 0.001),

Granulicatella (r = -0.65;

P = 0.013),

Actinomyces (r = -0.55;

P = 0.035),

Ihubacter (r = -0.53;

P = 0.038),

Collinsella (r = -0.51;

P = 0.045). Also, we observed a moderate-strong positive correlation of IgA levels with Bacillota phylum (r = 0.54;

P = 0.035) and

Lactonifactor genera (r = 0.79;

P = 0.002) (

Figure 6D-E).

Some differentially expressed genera in acute COVID-19 patients correlated with inflammatory IL-6 concentrations, including

Gemella (r = 0.58;

P = 0.025),

Lactonifactor (r = -0.58;

P = 0.025), and

Anaerobutyricum (r = -0.52;

P = 0.042) (

Figure 6F). Similarly, some genera correlated with IL-2 concentrations, such as

Erysipelatoclostridium (r = 0.77;

P = 0.003),

Anaerostipes (r = 0.58;

P = 0.025),

Eggerthella (r = 0.56;

P = 0.032),

Ruthenibacterium (r = 0.55;

P = 0.032), and

Anaerobutyricum (r = 0.52;

P = 0.042) (

Figure 6G). Also, IFN-γ levels correlated with taxonomic counts of Bacillota (formerly Firmicutes) (r = 0.70;

P = 0.006) and

Lachnospiraceae (r = 0.55;

P = 0.034) (

Figure 6H).

4. Discussion

Growing epidemiological and experimental data support the concept of the gut-lung axis, highlighting the connection between gut microbiota and lung health [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

52]. This axis involves two-way communication between the gastrointestinal and respiratory mucosa, mediated by microbial interactions, immune responses, and metabolic byproducts, which appear to influence the development and progression of several diseases, including COVID-19 [

28,

36,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Nevertheless, the bacteriome profile in SARS-CoV-2-infected Brazilian patients and the impact on gut permeability and systemic inflammatory cytokines have not yet been studied.

In this observational study, we investigated the gut bacteriome and permeability in acute COVID-19 and in Post-COVID-19 condition (PCC) patients, and correlate with systemic inflammatory cytokines in a cohort enrolled in the pre-vaccination period in Brazil.

Previous studies have reported significant alterations in the gut microbiota (bacteriome/mycobiome) in acute COVID-19 patients, including decreased microbial richness and diversity, along with a predominance of opportunistic microorganisms, and impaired short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) biosynthesis [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. Some studies identified a microbiota fingerprint associated with both disease severity and mortality in COVID-19, showing potential role as a disease severity predictor in hospitalized patients [

64,

65]. In addition, a marked reduction in beneficial gut commensals has been documented and has been inversely correlated with

proinflammatory cytokines and disease severity [

57,

58,

59,

60,

66]. Notably, more than 20% of adult COVID-19 patients fail to recover within three months and an imbalance in the gut microbiota persists even after SARS-CoV-2 virus negativity and respiratory symptoms’ resolution [

60,

67]. Recent studies showed intestinal dysbiosis in PCC patients and suggested a relationship between long-term sequalae, microbiota and metabolites disruption, and immune dysfunctions [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73]. In the present study we also observed significant differences in alpha and beta diversity metrics in acute COVID-19 and PCC, when compared with control subjects, with increased potential pathogenic members (

Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia-Shigella), and decreased beneficial commensal microbes (

Blautia, Alistipes)

, which are in agreement with previous studies.

Concerning the systemic immunity in acute COVID-19, clinical studies have shown a significant rise in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, IFN-γ, TNF, MCP-1) characterizing the cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or cytokine storm [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80]. CRS may arise directly from viral-induced tissue damage or indirectly through an overactive immune response, which leads to the infiltration of immune cells into affected tissues. Although this infiltration is initially intended to contain viral spread, it ultimately causes more damage than benefit [

75,

76]. The excessive immune response contributes to severe manifestations like ARDS, MOF, and increased mortality [

74,

75,

76]. Also, immune dysfunctions with impaired interaction between cellular and humoral adaptive immunity were observed in PCC patients, potentially resulting in immune dysregulation, persistent inflammation, and the clinical symptoms characteristic of this debilitating condition [

25,

26,

27,

81,

82]. In our study, we detected significant increase in plasma concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, IL-17A and IFN-γ in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients, in agreement with previous studies. Increased IL-6 levels have been consistently associated with disease severity in COVID-19 patients as have higher concentrations of CRP, a downstream inflammatory marker [

83,

84,

85,

86]. Increased IL-17 have been observed in severe COVID-19, and correlated with lung lesions and ARDS development [

74,

83]. Increased IFN-γ plays a central role in promoting a highly inflammatory macrophage phenotype within the lungs of severe COVID-19 patients [

87,

88]. Similar to other publications, we found some correlations between the bacteriome and inflammatory cytokines, suggesting that the bacteriome may influence the host's immune response to SARS-CoV-2 [

58,

60,

66,

71].

SARS-CoV-2 infection has been associated with increased gut permeability which may contribute to systemic inflammation and disease severity. Disruption of the gut epithelial barrier during COVID-19 and PCC can allow microbial products such as lipopolysaccharides and other endotoxins to translocate into the bloodstream, amplifying the host’s inflammatory response [

37,

38,

39,

89,

90]. Elevated levels of gut permeability markers, such as zonulin, LPS-binding protein, and intestinal fatty acid-binding protein, have been detected in COVID-19 patients and correlate with worse clinical outcomes [

91,

92,

93]. The gut-lung axis may play a critical role in COVID-19 pathophysiology, where compromised intestinal barrier function exacerbates pulmonary inflammation through the systemic circulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, and favors bacterial translocation and bacteremia [

92,

93]. We also detected increased gut permeability in our cohort, with high plasma zonulin levels in acute COVID-19 and PCC patients, in addition to strong positive correlation with

Enterobacteriaceae and

Escherichia-Shiguella, suggesting the involvement of a triad consisting of intestinal dysbiosis, leaky gut, and systemic inflammation in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients.

Our results reinforce the importance of the gut-lung axis and the role of the gut microbiota in modulating the immune responses and maintaining the intestinal barrier integrity, suggesting the capacity to modulate the immunity to SARS-CoV-2 through the gut microbiota. Our study presents some limitations, such as: 1) Lack of stratification analysis related to disease severity and antibiotic treatments; 2) We did not identify the circulating variants in our patients. The strengths of our study include: 1) Enrollment of patients in the pre-vaccination period, removing a confounder from the analyses; and 2) No studies evaluated variables such as microbiota, cytokines and permeability in Brazilian population, revealing important correlations to understand the gut-lung axis in acute COVID-19 and in long-term consequences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Gislane de Oliveira; Data curation, Gislane de Oliveira; Formal analysis, Larissa Souza, Lucas de Carvalho, Daniel Pinheiro and Gislane de Oliveira; Funding acquisition, Gislane de Oliveira; Investigation, Larissa Souza, Alexandre Ferreira-Junior, Pedro Estella, Ricardo Noda, Lhorena Sousa, Miguel Takao Murata and Gislane de Oliveira; Methodology, Larissa Souza, Alexandre Ferreira-Junior, Pedro Estella, Ricardo Noda, Lhorena Sousa, Miguel Takao Murata, Lucas de Carvalho and Josias Rodrigues; Project administration, Gislane de Oliveira; Resources, João Brisotti, Josias Rodrigues, Carlos Fortaleza and Gislane de Oliveira; Software, Lucas de Carvalho and Daniel Pinheiro; Supervision, João Brisotti, Daniel Pinheiro, Carlos Fortaleza and Gislane de Oliveira; Validation, Larissa Souza, Lhorena Sousa and Daniel Pinheiro; Visualization, João Brisotti, Josias Rodrigues and Carlos Fortaleza; Writing – original draft, Gislane de Oliveira; Writing – review & editing, Carlos Fortaleza and Gislane de Oliveira.

Funding

This research was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), process numbers #2018/16972-5 (Research grant for JR); #2023/03745-9 (Fellowship for LSS), by the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), process number #313190/2021-6 (Fellowship for GLVO), and by the covenant between UNESP and the Brazilian Ministry of Health, process number #15516/2022 (Research equipment for GLVO lab).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee from Sao Paulo State University (Process number 4,310,336/2020; September 30th,2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The 16S sequencing raw data is deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under BioProject PRJNA1189098.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Ana Lucia Barreto Penna, Professor Eleni Gomes, Professor Ricardo de Souza Cavalcante, Fernanda Chinelato Domingos, Bárbara Alves Chiarato, Camila Moreira Gomes, Luiza Ikeda Seixas Cardoso, Nelson Alves Pinheiro Neto.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021, 19(3):141-154. [CrossRef]

- Senevirathne TH, Wekking D, Swain JWR, Solinas C, De Silva P. COVID-19: From emerging variants to vaccination. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024, 76:127-141. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Available in https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c.

- Brazilian Ministry of Health. Coronavirus Panel. Available in https://covid.saude.gov.br/.

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA. 2020, 324(8):782-793. [CrossRef]

- Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or Moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383(18):1757-1766. [CrossRef]

- Berlin DA, Gulick RM, Martinez FJ. Severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383(25):2451-2460. [CrossRef]

- Brodin P. Immune determinants of COVID-19 disease presentation and severity. Nat Med. 2021, 27(1):28-33. [CrossRef]

- Gheorghita R, Soldanescu I, Lobiuc A, Caliman Sturdza OA, Filip R, Constantinescu-Bercu A et al. The knowns and unknowns of long COVID-19: from mechanisms to therapeutical approaches. Front Immunol. 2024, 15:1344086. [CrossRef]

- Hurme A, Viinanen A, Teräsjärvi J, Jalkanen P, Feuth T, Löyttyniemi E et al. Post-COVID-19 condition in prospective inpatient and outpatient cohorts. Sci Rep. 2025, 15(1):6925. [CrossRef]

- Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021, 27(4):601-615. [CrossRef]

- Parotto M, Gyöngyösi M, Howe K, Myatra SN, Ranzani O, Shankar-Hari M, Herridge MS. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19: understanding and addressing the burden of multisystem manifestations. Lancet Respir Med. 2023, 11(8):739-754. [CrossRef]

- Santos M, Dorna M, Franco E, Geronutti J, Brizola L, Ishimoto L et al. Clinical and Physiological Variables in Patients with Post-COVID-19 Condition and Persistent Fatigue. J Clin Med. 2024,13(13):3876. [CrossRef]

- Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ. Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023, 21(3):133-146. [CrossRef]

- Oelsner EC, Sun Y, Balte PP, Allen NB, Andrews H, Carson A et al. Epidemiologic Features of Recovery From SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2024, 7(6):e2417440. [CrossRef]

- Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition. A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022, 22(4):e102-e107. [CrossRef]

- Lamers MM, Haagmans BL. SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022, 20(5):270-284. [CrossRef]

- Steiner S, Kratzel A, Barut GT, Lang RM, Aguiar Moreira E, Thomann L et al. SARS-CoV-2 biology and host interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024, 22(4):206-225. [CrossRef]

- Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, Williams EP, Zalduondo L, Samir P et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ Triggers Inflammatory Cell Death, Tissue Damage, and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cytokine Shock Syndromes. Cell. 2021, 184(1):149-168.e17. [CrossRef]

- Diamond MS, Kanneganti TD. Innate immunity: the first line of defense against SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2022, 23(2):165-176. [CrossRef]

- Zheng M, Karki R, Williams EP, Yang D, Fitzpatrick E, Vogel P et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nat Immunol. 2021, 22(7):829-838. [CrossRef]

- Sette A, Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021, 184(4):861-880. [CrossRef]

- Pozdnyakova V, Weber B, Cheng S, Ebinger JE. Review of Immunologic Manifestations of COVID-19 Infection and Vaccination. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2025, 51(1):111-121. [CrossRef]

- Qi H, Liu B, Wang X, Zhang L. The humoral response and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022, 23(7):1008-1020. [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh C, Darley DR, Wilson DB, Howe A, Munier CML, Patel SK et al. Immunological dysfunction persists for 8 months following initial mild-to-moderate SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022, 23(2):210-216. [CrossRef]

- Yin K, Peluso MJ, Luo X, Thomas R, Shin MG, Neidleman J et al. Long COVID manifests with T cell dysregulation, inflammation and an uncoordinated adaptive immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat Immunol. 2024, 25(2):218-225. [CrossRef]

- Phetsouphanh C, Jacka B, Ballouz S, Jackson KJL, Wilson DB, Manandhar B et al. Improvement of immune dysregulation in individuals with long COVID at 24-months following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2024, 15(1):3315. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira GLV, Oliveira CNS, Pinzan CF, de Salis LVV, Cardoso CRB. Microbiota Modulation of the Gut-Lung Axis in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021, 12:635471. [CrossRef]

- Budden KF, Gellatly SL, Wood DL, Cooper MA, Morrison M, Hugenholtz P, Hansbro PM. Emerging pathogenic links between microbiota and the gut-lung axis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2017, 15(1):55-63. [CrossRef]

- Grayson MH, Camarda LE, Hussain SA, Zemple SJ, Hayward M, Lam V et al. Intestinal Microbiota Disruption Reduces Regulatory T Cells and Increases Respiratory Viral Infection Mortality Through Increased IFNγ Production. Front Immunol. 2018, 9:1587. [CrossRef]

- Dang AT, Marsland BJ. Microbes, metabolites, and the gut-lung axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12(4):843-850. [CrossRef]

- Enaud R, Prevel R, Ciarlo E, Beaufils F, Wieërs G, Guery B, Delhaes L. The Gut-Lung Axis in Health and Respiratory Diseases: A Place for Inter-Organ and Inter-Kingdom Crosstalks. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020, 10:9. [CrossRef]

- Zhang D, Li S, Wang N, Tan HY, Zhang Z, Feng Y. The Cross-Talk Between Gut Microbiota and Lungs in Common Lung Diseases. Front Microbiol. 2020, 11:301. [CrossRef]

- Stefan KL, Kim MV, Iwasaki A, Kasper DL. Commensal Microbiota Modulation of Natural Resistance to Virus Infection. Cell. 2020, 183(5):1312-1324.e10. [CrossRef]

- Ngo VL, Lieber CM, Kang HJ, Sakamoto K, Kuczma M, Plemper RK, Gewirtz AT. Intestinal microbiota programming of alveolar macrophages influences severity of respiratory viral infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2024, 32(3):335-348.e8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ma Y, Sun W, Zhou X, Wang R, Xie P et al. Exploring gut-lung axis crosstalk in SARS-CoV-2 infection: Insights from a hACE2 mouse model. J Med Virol. 2024, 96(1):e29336. [CrossRef]

- Giron LB, Dweep H, Yin X, Wang H, Damra M, Goldman AR et al. Plasma Markers of Disrupted Gut Permeability in Severe COVID-19 Patients. Front Immunol. 2021, 12:686240. [CrossRef]

- Prasad R, Patton MJ, Floyd JL, Fortmann S, DuPont M, Harbour A, Wright J, Lamendella R, Stevens BR, Oudit GY, Grant MB. Plasma Microbiome in COVID-19 Subjects: An Indicator of Gut Barrier Defects and Dysbiosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(16):9141. [CrossRef]

- Bernard-Raichon L, Venzon M, Klein J, Axelrad JE, Zhang C, Sullivan AP et al. Gut microbiome dysbiosis in antibiotic-treated COVID-19 patients is associated with microbial translocation and bacteremia. Nat Commun. 2022, 13(1):5926. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S., 2010. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. Babraham Bioinformatics, Babraham Institute, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJ, Holmes SP. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016, 13(7):581-3. [CrossRef]

- Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam SA, McGarrell DM et al. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33:D294-6. [CrossRef]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990, 215(3):403-10. [CrossRef]

- Schliep KP. phangorn: phylogenetic analysis in R. Bioinformatics. 2011, 27(4):592-3. [CrossRef]

- McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One. 2013, 8(4):e61217. [CrossRef]

- Mikryukov, V., 2022. metagMisc: Miscellaneous functions for metagenomic analysis.

- Andersen, K.S., Kirkegaard, R.H., Karst, S.M., Albertsen, M., 2018. ampvis2: an R package to analyse and visualise 16S rRNA amplicon data. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Lahti, L., Shetty, S., 2012. microbiome R package.

- Oksanen, J., Simpson, G.L., Blanchet, F.G., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., Minchin, P.R. et al. 2022. vegan: Community Ecology Package.

- Arbizu, P.M., 2017. pairwiseAdonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison using Adonis. R Core Team, 2023. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Wickham, H., 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer-Verlag New York.

- Sencio V, Machado MG, Trottein F. The lung-gut axis during viral respiratory infections: the impact of gut dysbiosis on secondary disease outcomes. Mucosal Immunol. 2021, 14(2):296-304. [CrossRef]

- Allali I, Bakri Y, Amzazi S, Ghazal H. Gut-Lung Axis in COVID-19. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2021, 2021:6655380. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Huang W, Fan Y, Chen GQ. Gastrointestinal Microenvironment and the Gut-Lung Axis in the Immune Responses of Severe COVID-19. Front Mol Biosci. 2021, 8:647508. [CrossRef]

- Wang B, Zhang L, Wang Y, Dai T, Qin Z, Zhou F, Zhang L. Alterations in microbiota of patients with COVID-19: potential mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022, 7(1):143. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Lau RI, Liu Q, Su Q, Chan FKL, Ng SC. Gut microbiota in COVID-19: key microbial changes, potential mechanisms and clinical applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023, 20(5):323-337. [CrossRef]

- Zuo T, Zhang F, Lui GCY, Yeoh YK, Li AYL, Zhan H et al. Alterations in Gut Microbiota of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020, 159(3):944-955.e8. [CrossRef]

- Gu S, Chen Y, Wu Z, Chen Y, Gao H, Lv L, Guo F et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71(10):2669-2678. [CrossRef]

- Zuo T, Liu Q, Zhang F, Lui GC, Tso EY, Yeoh YK et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021, 70(2):276-284. [CrossRef]

- Yeoh YK, Zuo T, Lui GC, Zhang F, Liu Q, Li AY et al. Gut microbiota composition reflects disease severity and dysfunctional immune responses in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2021, 70(4):698-706. [CrossRef]

- Nobre JG, Delgadinho M, Silva C, Mendes J, Mateus V, Ribeiro E et al. Gut microbiota profile of COVID-19 patients: Prognosis and risk stratification (MicroCOVID-19 study). Front Microbiol. 2022, 13:1035422. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu K, Hirata H, Tokuhira N, Motooka D, Nakamura S, Ueda A et al. Dysbiosis of gut microbiota in patients with severe COVID-19. Acute Med Surg. 2024, 11(1):e923. [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama Y, Ichiki T, Yamakawa T, Tsuji Y, Kuronuma K, Takahashi S et al. Gut microbiota and metabolites in patients with COVID-19 are altered by the type of SARS-CoV-2 variant. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15:1358530. [CrossRef]

- Bucci V, Ward DV, Bhattarai S, Rojas-Correa M, Purkayastha A, Holler D et al. The intestinal microbiota predicts COVID-19 severity and fatality regardless of hospital feeding method. mSystems. 2023, 8(4):e0031023. [CrossRef]

- Zhong J, Guo L, Wang Y, Jiang X, Wang C, Xiao Y et al. Gut Microbiota Improves Prognostic Prediction in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients Alongside Immunological and Hematological Indicators. Research (Wash D C). 2024, 7:0389. [CrossRef]

- Nagata N, Takeuchi T, Masuoka H, Aoki R, Ishikane M, Iwamoto N et al. Human Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolites Impact Immune Responses in COVID-19 and Its Complications. Gastroenterology. 2023, 164(2):272-288. [CrossRef]

- An Y, He L, Xu X, Piao M, Wang B, Liu T, Cao H. Gut microbiota in post-acute COVID-19 syndrome: not the end of the story. Front Microbiol. 2024, 15:1500890. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Gu S, Chen Y, Lu H, Shi D, Guo J et al. Six-month follow-up of gut microbiota richness in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2022, 71(1):222-225. [CrossRef]

- Liu Q, Mak JWY, Su Q, Yeoh YK, Lui GC, Ng SSS et al. Gut microbiota dynamics in a prospective cohort of patients with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Gut. 2022, 71(3):544-552. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Junior AS, Borgonovi TF, De Salis LVV, Leite AZ, Dantas AS, De Salis GVV et al. Detection of Intestinal Dysbiosis in Post-COVID-19 Patients One to Eight Months after Acute Disease Resolution. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022, 19(16):10189. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Wan Y, Zuo T, Yeoh YK, Liu Q, Zhang L et al. Prolonged Impairment of Short-Chain Fatty Acid and L-Isoleucine Biosynthesis in Gut Microbiome in Patients With COVID-19. Gastroenterology. 2022, 162(2):548-561.e4. [CrossRef]

- Su Q, Lau RI, Liu Q, Li MKT, Yan Mak JW, Lu W et al. The gut microbiome associates with phenotypic manifestations of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Cell Host Microbe. 2024, 32(5):651-660.e4. [CrossRef]

- Blankestijn JM, Baalbaki N, Beijers RJHCG, Cornelissen MEB, Wiersinga WJ, Abdel-Aziz MI et al. P4O2 Consortium. Exploring Heterogeneity of Fecal Microbiome in Long COVID Patients at 3 to 6 Months After Infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26(4):1781. [CrossRef]

- Darif D, Hammi I, Kihel A, El Idrissi Saik I, Guessous F, Akarid K. The pro-inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 pathogenesis: What goes wrong? Microb Pathog. 2021, 153:104799. [CrossRef]

- Zanza C, Romenskaya T, Manetti AC, Franceschi F, La Russa R, Bertozzi G et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: Immunopathogenesis and Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58(2):144. [CrossRef]

- Deng X, Tang K, Wang Z, He S, Luo Z. Impacts of Inflammatory Cytokines Variants on Systemic Inflammatory Profile and COVID-19 Severity. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2024, 14(2):363-378. [CrossRef]

- Islam F, Habib S, Badruddza K, Rahman M, Islam MR, Sultana S, Nessa A. The Association of Cytokines IL-2, IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ, and IL-10 With the Disease Severity of COVID-19: A Study From Bangladesh. Cureus. 2024, 16(4):e57610. [CrossRef]

- Safont G, Villar-Hernández R, Smalchuk D, Stojanovic Z, Marín A, Lacoma A et al. Measurement of IFN-γ and IL-2 for the assessment of the cellular immunity against SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep. 2024, 14(1):1137. [CrossRef]

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, Tao Y et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71(15):762-768. [CrossRef]

- Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021, 93(1):250-256. [CrossRef]

- Kervevan J, Staropoli I, Slama D, Jeger-Madiot R, Donnadieu F, Planas D et al. Divergent adaptive immune responses define two types of long COVID. Front Immunol. 2023, 14:1221961. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari A, Maddumage J, Eriksson EM, Annesley SJ, Lawson VA, Bryant VL, Gras S. Beyond acute infection: mechanisms underlying post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC). Med J Aust. 2024, 9:S40-S48. [CrossRef]

- Lucas C, Wong P, Klein J, Castro TBR, Silva J, Sundaram M et al. Longitudinal analyses reveal immunological misfiring in severe COVID-19. Nature. 2020, 584(7821):463-469. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood SBZ, Majid H, Arshad A, Zaib-Un-Nisa, Niazali N, Kazi K et al. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) as a Predictor of Clinical Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19. Clin Lab. 2023, 69(6). [CrossRef]

- Herold T, Jurinovic V, Arnreich C, Lipworth BJ, Hellmuth JC, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Klein M, Weinberger T. Elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP predict the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020, 146(1):128-136.e4. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Zhao B, Qu Y, Chen Y, Xiong J, Feng Y et al. Detectable Serum Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Viral Load (RNAemia) Is Closely Correlated With Drastically Elevated Interleukin 6 Level in Critically Ill Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis. 2020, 71(8):1937-1942. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Mears JR, Shakib L, Beynor JI, Shanaj S, Korsunsky I, et al. IFN-γ and TNF-α drive a CXCL10+ CCL2+ macrophage phenotype expanded in severe COVID-19 lungs and inflammatory diseases with tissue inflammation. Genome Med. 2021, 13(1):64. [CrossRef]

- Karki R, Sharma BR, Tuladhar S, Williams EP, Zalduondo L, Samir P et al. Synergism of TNF-α and IFN-γ Triggers Inflammatory Cell Death, Tissue Damage, and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cytokine Shock Syndromes. Cell. 2021, 184(1):149-168.e17. [CrossRef]

- Mouchati C, Durieux JC, Zisis SN, Labbato D, Rodgers MA, Ailstock K, Reinert BL, Funderburg NT, McComsey GA. Increase in gut permeability and oxidized ldl is associated with post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. Front Immunol. 2023, 14:1182544. [CrossRef]

- Gallo A, Murace CA, Corbo MM, Sarlo F, De Ninno G, Baroni S, et al. Gemelli against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Team. Intestinal Inflammation and Permeability in Patients Recovered from SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Dig Dis. 2025, 43(1):1-10. [CrossRef]

- Oliva A, Miele MC, Di Timoteo F, De Angelis M, Mauro V, Aronica R, Al Ismail D, Ceccarelli G, Pinacchio C, d'Ettorre G, Mascellino MT, Mastroianni CM. Persistent Systemic Microbial Translocation and Intestinal Damage During Coronavirus Disease-19. Front Immunol. 2021, 12:708149. [CrossRef]

- Oliva A, Cammisotto V, Cangemi R, Ferro D, Miele MC, De Angelis M, Cancelli F, Pignatelli P, Venditti M, Pugliese F, Mastroianni CM, Violi F. Low-Grade Endotoxemia and Thrombosis in COVID-19. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021, 12(6):e00348. [CrossRef]

- Palomino-Kobayashi LA, Ymaña B, Ruiz J, Mayanga-Herrera A, Ugarte-Gil MF, Pons MJ. Zonulin, a marker of gut permeability, is associated with mortality in a cohort of hospitalised peruvian COVID-19 patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12:1000291. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A) Richness observed; (B) Chao1 index; (C) Shannon diversity; (D) Faith's phylogenetic diversity.

Figure 1.

Alpha diversity analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A) Richness observed; (B) Chao1 index; (C) Shannon diversity; (D) Faith's phylogenetic diversity.

Figure 2.

Beta diversity analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients using Weighted e Unweighted UniFrac metrics. (A,D) Distances to Centroid; (B,C,E,F) Principal Coordinates Analysis with different clusters.

Figure 2.

Beta diversity analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients using Weighted e Unweighted UniFrac metrics. (A,D) Distances to Centroid; (B,C,E,F) Principal Coordinates Analysis with different clusters.

Figure 3.

Taxa distribution and differential abundance analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A-C) Taxa abundances (D-I) Genera differential abundance analysis.

Figure 3.

Taxa distribution and differential abundance analysis of the gut bacteriome from control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A-C) Taxa abundances (D-I) Genera differential abundance analysis.

Figure 4.

Zonulin plasma concentrations (A), and Fecal secretory IgA in control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients.

Figure 4.

Zonulin plasma concentrations (A), and Fecal secretory IgA in control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients.

Figure 5.

Cytokines’ concentrations in control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A) IL-2 plasma levels, (B) IL-6, (C) IL-17A, and (D) IFN-γ.

Figure 5.

Cytokines’ concentrations in control subjects (CTL), acute COVID-19 patients, and Post-COVID-19 Condition (PCC) patients. (A) IL-2 plasma levels, (B) IL-6, (C) IL-17A, and (D) IFN-γ.

Figure 6.

Correlations between taxonomic counts of gut bacteriome and clinical-laboratory data in acute COVID-19 patients. (A) C-reactive protein with differentially increased genera. (B-C) Plasma zonulin levels with differentially increased families and genera. (D-E) Fecal sIgA levels differentially increased Bacillota, Prevotellacea, and some genera. (F-H) Plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-2 and IFN-γ with differentially increased taxa.

Figure 6.

Correlations between taxonomic counts of gut bacteriome and clinical-laboratory data in acute COVID-19 patients. (A) C-reactive protein with differentially increased genera. (B-C) Plasma zonulin levels with differentially increased families and genera. (D-E) Fecal sIgA levels differentially increased Bacillota, Prevotellacea, and some genera. (F-H) Plasma concentrations of IL-6, IL-2 and IFN-γ with differentially increased taxa.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and controls.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients and controls.

| |

COVID-19

(n = 79) |

PCC

(n = 141) |

CTL

(n = 97) |

Biological sex

Female/Male |

46 F/ 33 M |

88 F/ 53 M |

83 F/ 14 M |

Age (Years)

Mean ± SD |

51.8 ± 16.3 |

40.8 ± 13.9 |

43.8 ± 13.6 |

BMI (Kg/m2)

Mean ± SD |

28.6 ± 6.2 |

29.1 ± 5.4 |

25.2 ± 4.8 |

CRP (mg/dL)

Mean ± SD |

78.6 ± 67.0 |

8.4 ± 9.6 |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).