1. Introduction

The energy landscape has undergone significant transformation, with the drive towards efficiency evolving from mere rhetoric to an absolute global imperative. Power systems, constituting the nexus of this transformation, hinge upon a core tenet—optimization. This entails the systematic calibration of parameters to yield optimal outcomes.

Within power systems, optimization’s significance is undeniable. It seeks the judicious tuning of variables to either amplify or minimize a particular objective function. In mathematical terms, this aims to minimize

, encompassing variables

, in the space

. This endeavor, however, operates within the confines of specific constraints, both of equality,

, and inequality,

[

1].

In recent studies, hardware-centric designs have been explored for improved wind speed prediction under memory constraints [

1]. Furthermore, optimization techniques often struggle with noise disturbances, which can impair the performance of algorithms in power systems. For instance, image steganography and preprocessing techniques are used to achieve both data security and improved payload capacity, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of data transmission in such systems [

2]. Moreover, advances in physics-informed models, such as integrating physics-informed vectors in neural networks, have been shown to improve wind speed prediction, which is highly relevant to renewable energy forecasting [

3].

Within power systems, optimization’s significance is undeniable. It seeks the judicious tuning of variables to either amplify or minimize a particular objective function. In mathematical terms, this aims to minimize

, encompassing variables

, in the space

. This endeavor, however, operates within the confines of specific constraints, both of equality,

, and inequality,

as disscussed in [

4].

Central to power optimization, the Economical Load Dispatch (ELD) emerges as a paradigm of critical importance. In [

5], authors discussed that ELD’s objective is two-fold: ensuring economic feasibility while meticulously adhering to pre-defined constraints. Within the ELD spectrum, a distinction exists between those considering the valve point effect, leading to the more complex non-smooth ELD, and those which bypass it, resulting in smooth ELD. The challenges of non-smooth ELD stem largely from the nonlinear characteristics of cost functions.

An imperative in this domain is the harmonized power output across all generators, mandating their operation within prescribed thresholds. Simultaneously, it’s indispensable to factor in transmission losses, which amplify with increasing transmission distances.

While the optimization toolkit boasts both deterministic and stochastic algorithms, the former often grapples with real-world intricacies. Its inherent assumptions, like expecting continuous objective functions, curtail its versatility. Stochastic algorithms, unencumbered by such rigidity, have showcased superior adaptability, rendering them more suitable for multifarious optimization challenges.

The daunting nature of the ELD problem, marked by its non-convex characteristics, has necessitated a paradigm shift in approach. Traditional strategies often falter, paving the way for heuristic techniques. These heuristic methods, inherently adaptive, have gained traction, given their proclivity for handling the ELD’s complexities.

Nature-inspired algorithms, stemming from diverse natural phenomena, have burgeoned in response to the ELD challenge. While these algorithms make bold claims about their superiority, their heuristic and random essence ensures that no single strategy reigns supreme consistently. Their performance, often sporadic, varies across different scenarios, making universal superiority claims overly simplistic.

Yet, it’s vital to highlight heuristic methods’ susceptibility to noise disruptions, especially pronounced in ELD scenarios with variable loads. The dynamic ELD landscape, when marred with noise, can mislead heuristic algorithms, resulting in less than optimal or even flawed solutions. This emphasizes the urgency for robust protective measures when deploying heuristic algorithms in critical operations.

The selection of Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) as the noise model is underpinned by both its ubiquity in systems analysis and its relevance to real-world disturbances. AWGN, characterized by its flat spectral density and uncorrelated nature over time, offers a benchmark for noise that many real-world communication and control systems experience. From the Central Limit Theorem, a multitude of minor random disturbances in the system aggregate to form a noise which closely resembles AWGN. By designing our model to effectively handle AWGN, we inherently equip it to tackle a broad range of noise disturbances. This choice ensures not just academic robustness but also practical resilience, enabling the model to maintain optimal performance even in real-world noisy environments prevalent in power systems.

In this work, we introduce a robust scheme to address the challenges of the ELD problem, especially in scenarios with variable loads affected by noise. Our key contributions are:

Noise Mitigation: By leveraging an autoencoder model, we effectively remove the detrimental effects of Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) from the variable load demand signal. This acts as a safeguard, bolstering our system against potential noise attacks and ensuring solution reliability.

Integrated Parallel Processing Framework: Our framework capitalizes on the synergistic strengths of three established algorithms—Genetic Algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and a third unspecified algorithm—executing them concurrently through parallel processing. This multifaceted approach ensures robustness and enhances the speed of convergence, as the Genetic Algorithm and PSO actively share their best parent and global best positions, respectively, in each iteration. This collaborative mechanism not only expedites the optimization process but also significantly trims down the computational time, presenting a substantial improvement over traditional sequential execution methods.

Optimized Power Dispatch in Variable Load Conditions: Through comprehensive simulations, our framework has demonstrated its adeptness in handling variable load conditions, outperforming existing schemes significantly. Employing a novel approach, we transitioned from a static load of 2000 MWatt, common in previous studies, to a variable load scenario with a 10% tolerance around the 2000 MWatt benchmark. This allowed for a more realistic and challenging test environment. The integration of an auto-encoder significantly enhanced the robustness of our solution, as evident from the substantial reduction in discrepancies between demand and supply across various algorithms. This was particularly noticeable when comparing the performance with and without the auto-encoder, showcasing our framework’s ability to maintain stability and achieve optimal power dispatch even under fluctuating demands. Additionally, the parallel processing of Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization not only resulted in faster convergence but also in reduced computational time and cost, establishing our framework’s efficiency and effectiveness in real-world applications.

Preliminary evaluations of our approach yield promising results, demonstrating marked enhancements in overall optimization outcomes.

2. Related Work

Various techniques have been employed in ELD to minimize the fuel cost associated with power generation. Traditional ELD methods encompass Linear Programming (LP), Lagrange multiplier, Newton Raphson methods, and Dynamic Programming (DP) [

6,

7,

8]. Notably, these methods exhibit certain limitations, especially when tackling intricate optimization challenges. For example, the performance of Genetic Algorithms (GA) [

9,

10]and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) can degrade in the presence of noise, which is a common issue in real-world power systems. Recent research has shown that steganography techniques, such as those described in [

2], can enhance data security and payload capacity in environments where noise is a concern. Additionally, advances in neural network architectures have been integrated with physics-informed vectors for more accurate wind speed prediction, which can significantly improve the accuracy of renewable energy forecasting and optimize power generation scheduling [

3].

On the contrary, swarm intelligence displays promise in delivering valuable results for ELD. In the realm of ELD optimization, Genetic Algorithms (GA) can pinpoint global optima in situations where the problem is characterized as non-smooth, non-linear, or non-convex [

11]. A groundbreaking GA-centric strategy that also prioritizes environmental objectives was presented by Abido [

12]. Highlighting transmission loss and ramp-rate constraints, Hosseini and Kheradmandi delved into a GA-driven deregulated power system, albeit overlooking the penalty factor [

13]. Hong and Li [

6] showcased GA-based systems tailored for short-term scheduling, featuring an ensemble of diesel generators, solar photovoltaics, batteries, and wind power. Historically, diverse metaheuristic strategies like Simulated Annealing [

7], Particle Swarm Optimization [

14], and Grey Wolf Optimization [

15] have been adopted for ELD.

Although Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) have demonstrated substantial proficiency in achieving optimal power dispatch in various scenarios, their heuristic nature inherently leaves room for further refinement and improvement. Due to the stochastic elements and local optimal challenges associated with these algorithms, there is a perpetual quest for more reliable and efficient solutions. Recognizing this, we have proposed a novel algorithm that aims to surpass the limitations of GA, PSO, and ABC, striving for enhanced precision, faster convergence, and robust performance across a broader spectrum of operating conditions. This initiative represents our commitment to advancing the state of the art in power system optimization, ensuring that we are consistently pushing the boundaries and setting new benchmarks for efficiency and effectiveness.

Furthermore, despite the reasonable performance of Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) in standard scenarios, these algorithms have not been rigorously tested against noise attacks on the system, which can significantly impact their accuracy and reliability. To address this gap, our work introduces the challenge of Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) as an attack on the demand signal, providing a stringent test of these algorithms’ robustness under adversarial conditions. The performance of GA, PSO, and ABC is meticulously evaluated to understand their resilience and adaptability when faced with such noise-induced distortions. Acknowledging the potential vulnerabilities exposed through this testing, we advocate for the integration of an auto-encoder as a strategic countermeasure. The auto-encoder is meticulously designed to cleanse the demand signal, effectively stripping away the noise and thereby safeguarding the integrity of the power dispatch process. This innovative approach not only enhances the system’s resilience against noise attacks but also ensures that the optimization algorithms can operate on clean, reliable data, leading to more accurate and stable power dispatch solutions.

In this study, we harnessed the capabilities of the Genetic Algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization, and the Bee Colony Algorithm, executing them concurrently. This parallel execution not only reduced the production costs effectively but also streamlined the computation time for obtaining minimal power. When juxtaposed against running these algorithms sequentially, the time savings were evident. Additionally, an integrated auto-encoder model was employed to filter out noise from the demand signal, thereby enhancing the system’s resilience against noise disturbances.

3. Preliminary Knowledge

3.1. Genetic Algorithms (GA)

Genetic Algorithms (GAs) are optimization techniques inspired by natural selection [

16]. They’re used for complex optimization problems [

16,

17,

18,

19] and power optimization [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Key principles include:

- Chromosomes and Genes: Solutions are represented as chromosomes made of genes.

- Population: Set of potential solutions.

- Fitness Function: Evaluates solution quality.

Mathematical Interpretation of GA

- Fitness Function: evaluates solution quality.

- Selection: Probability of selecting chromosome

i:

3.2. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

PSO is an optimization method inspired by social organisms’ behavior [

25]. It’s applied in engineering [

26,

27,

28] and power optimization [

20,

29,

30]. Key components:

- Particles: Represent potential solutions.

- Global Best (gBest) and Personal Best (pBest): Best solutions found.

3.3. Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) Algorithm

The Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) Algorithm is a population-based optimization technique inspired by the foraging behavior of honey bees [

31]. It has been applied to various optimization problems [

32,

33] including power system optimization [

34,

35]. The algorithm operates based on the collaborative behavior of three types of bees: employed bees, onlooker bees, and scout bees. Key principles include:

Food Source Representation: Potential solutions are represented as food sources.

Bee Population: A colony of bees searching for the best food source.

Fitness Evaluation: Quality of a food source is evaluated using a fitness function.

Mathematical Interpretation of ABC

The position of a food source is represented as , and its nectar amount (quality of the solution) is evaluated using a fitness function . The bees employ different strategies to explore the search space and exploit the best-found solutions:

The ABC algorithm iteratively improves the position of the food sources until a termination criterion is met, aiming to find the global optimum of the problem.

3.4. Autoencoders for Noise Removal

Auto-encoders are a specific type of artificial neural network architecture designed for unsupervised learning. Their primary function is to learn efficient representations of input data, typically for the purpose of dimensionality reduction or feature extraction. Among the various types of autoencoders, Denoising Autoencoders are particularly designed to remove noise from input data, making them invaluable for tasks such as image denoising and signal enhancement [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

3.4.1. Key Components of Auto-encoders

Encoder: The encoder is the first half of the auto-encoder. It takes the input data and compresses or encodes it into a compact, lower-dimensional latent space. Mathematically, the encoding process can be represented as:

where

x is the input data and

z is the encoded representation.

Decoder: The decoder is the second half of the autoencoder. It takes the encoded data from the latent space and attempts to reconstruct or decode it back to its original form. The decoding process is given by:

where

is the reconstructed data.

The objective of training an autoencoder is to minimize the difference between the original input

x and its reconstruction

, often using a loss function like the mean squared error:

where

n is the number of data points.

4. Problem Formulation

The objective of Economic Load Dispatch (ELD) is to minimize the fuel cost of a power plant. This is achieved by formulating an objective function that comprises the sum of fuel costs for all generators. Neglecting the impact of valve points, the fuel cost equation for the

generator can be represented as follows:

Incorporating the valve point effect results in a non-smooth ELD, and consequently, the fuel cost function would be altered.

Here, the fuel cost coefficients that depend on generators’ properties are denoted by

,

,

,

, and

. The power generated by the

unit is denoted by

, while

represents the fuel cost to generate

power. Finally, to determine the total fuel cost

, it must be summed as follows:

The above problem may have an optimal solution, but its non-convex nature makes it hard to find a global optimal solution using conventional optimization techniques. Therefore, the suboptimal solution can be found using Heuristic computation techniques such as GA, PSO, and others. Furthermore, the problem is a constrained problem that is:

Where

is the power generated by the

unit,

is the demand at a certain time, and

is the line loss. However, to investigate the effect of noise in the signal the above can be rewritten as follows

Here, represents the discrete AWGN noise sample at the data point.

Beside this equality constraint, we have two inequality constraints that are capacity constraints given as follows:

This means that the power of the plant cannot exceed or reduce from the maximum or minimum production limits. Furthermore, practically speaking, a generator cannot abruptly reduce or increase its power above a threshold; therefore, a ramp rate constraint is given as follows:

Where is the lower ramp limit and is the upper ramp rate.

Various heuristic computation techniques have been utilized to address this problem, including genetic algorithm, ant colony optimization, bee colony optimization, particle swarm optimization, and others. Despite their efficacy, these algorithms suffer from sluggishness due to their iterative nature, and may be vulnerable to perturbations in power demand due to the potential introduction of noise. Consequently, there exists a persistent requirement for rapid and robust optimization techniques that can minimize the number of iterations required while also exhibiting resilience to noise-induced disturbances in the demand curve.

5. Proposed Methodology

This section delves into our proposed strategy to address the economic load dispatch problem. The upcoming subsections shed light on the relationship between power economic dispatch and the fitness function. Subsequently, we describe a two-stage solution: the first phase emphasizes noise removal from the demand signal, while the second phase focuses on determining the optimal power necessary to satisfy the demand.

5.1. Fitness Function in the Context of Power Economic Dispatch

Economic Power Dispatch aims to optimize the cost of power production. The main objective can be succinctly represented by minimizing the total power production cost, as articulated in the equation below. This minimization is subjected to specific constraints:

To solve this optimization problem using Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), a fitness function needs to be defined. The fitness function will evaluate how close a given solution is to the optimum, considering both the objective function and the constraints. In this case, the fitness function can be designed as a minimization problem where lower fitness values are better. The fitness function

is formulated as follows:

The penalties are introduced to ensure that the constraints are satisfied:

Equality Constraint Penalty: The penalty for the equality constraint is computed as the absolute deviation from zero:

Inequality Constraint Penalties: The penalties for the inequality constraints are computed for any violations:

Here, and are penalty factors that need to be chosen based on the importance of satisfying each constraint. High values of will strongly discourage constraint violations.

In summary, the fitness function encapsulates the objective of minimizing the total power production cost while ensuring that the constraints are adhered to. Both Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization will iteratively search for the solution that minimizes the fitness function, striving towards an optimal solution for the Economic Power Dispatch problem.

5.2. Auto-Encoder

An auto-encoder model is designed to filter out noise from power demand signals, thereby enhancing the security of power systems. This approach is particularly useful for counteracting potential attacks that involve injecting noise into sensor readings for power demand on load lines. By using an autoencoder, the system can accurately identify and eliminate this injected noise, ensuring that the optimal power dispatch system remains aligned with actual demand levels.

In this study, Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) is introduced into genuine power demand signals to simulate the noisy conditions. The autoencoder then serves as a denoising mechanism, effectively removing the noise and restoring the original signal.

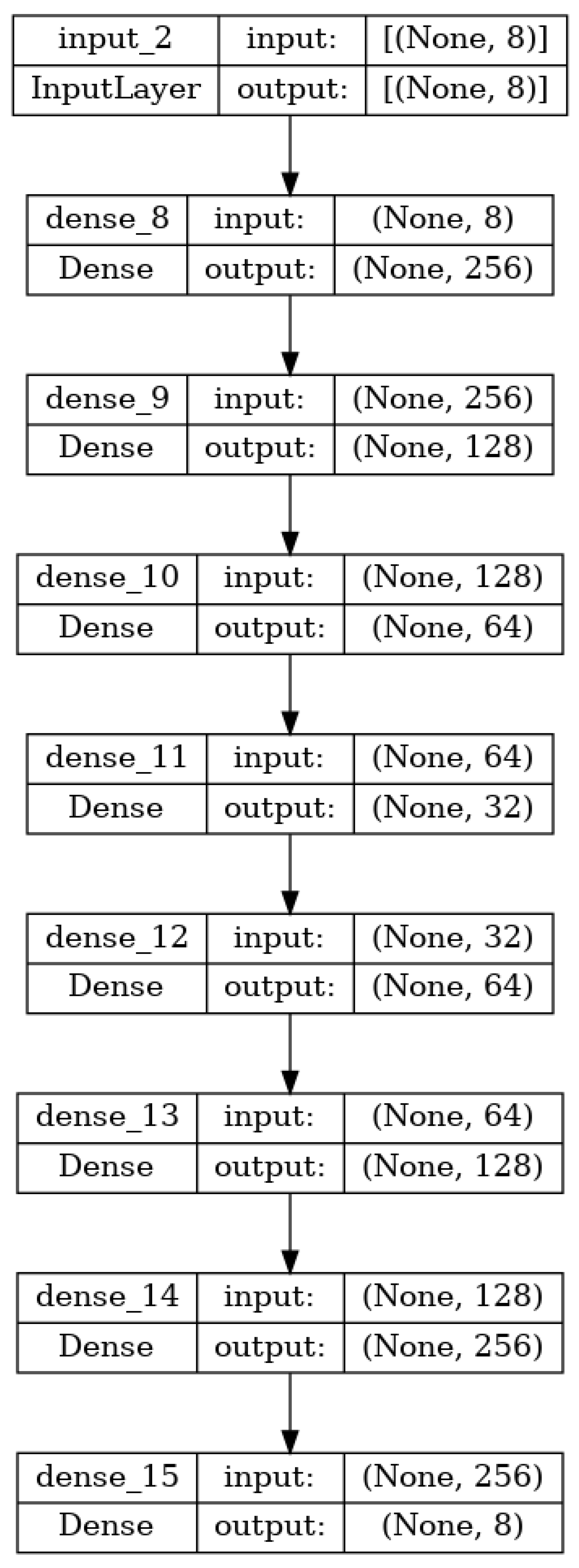

As shown in

Figure 1, the architecture of the employed autoencoder is specifically tailored for this task. The model takes eight noisy power demand samples as input. Among these eight samples, seven represent historical demand levels, while the eighth sample corresponds to the current power demand. Initially, the autoencoder projects these eight input samples onto a higher-dimensional space using a dense layer with 256 neurons. Subsequently, the model reduces dimensionality through a series of dense layers with 128, 64, and 32 neurons.

In the decoding phase, the autoencoder reverses this operation, incrementally increasing the dimensionality of the signal. The output is a reconstructed, noise-free signal where the eighth sample indicates the current power demand. This effectively safeguards the optimal power dispatch system from diverging due to noise interference.

The architecture of the autoencoder is both intuitive and meticulously designed for denoising the power demand signals contaminated by AWGN. After receiving the eight power demand samples, the encoder section of the autoencoder starts by elevating the dimensionality of the data, capturing intricate details via a dense layer housing 256 neurons. This transformation not only accommodates the noisy inputs but also extracts features and patterns that are vital for denoising. As the data moves through the subsequent layers, each with 128, 64, and 32 neurons respectively, the model focuses on compressing the data, retaining only the most significant features while discarding the noise-induced anomalies. This compression acts as a form of feature selection, emphasizing the true characteristics of the power demand signal. Upon reaching the core of the autoencoder, the decoding phase kicks in. Mirroring the encoding process but in reverse order, the data is expanded through layers with 64, 128, and 256 neurons. As the model reconstructs the signal, it aims to regenerate the original power demand characteristics without the noise. The final layer, which outputs eight samples, serves a dual purpose: it not only reproduces the seven historical power demand levels but also revitalizes the current power demand sample, purged of any noise. The elegance of this architecture lies in its symmetrical design, ensuring a seamless transition from noisy inputs to denoised outputs, hence fortifying the optimal power dispatch system’s resilience against noisy perturbations.

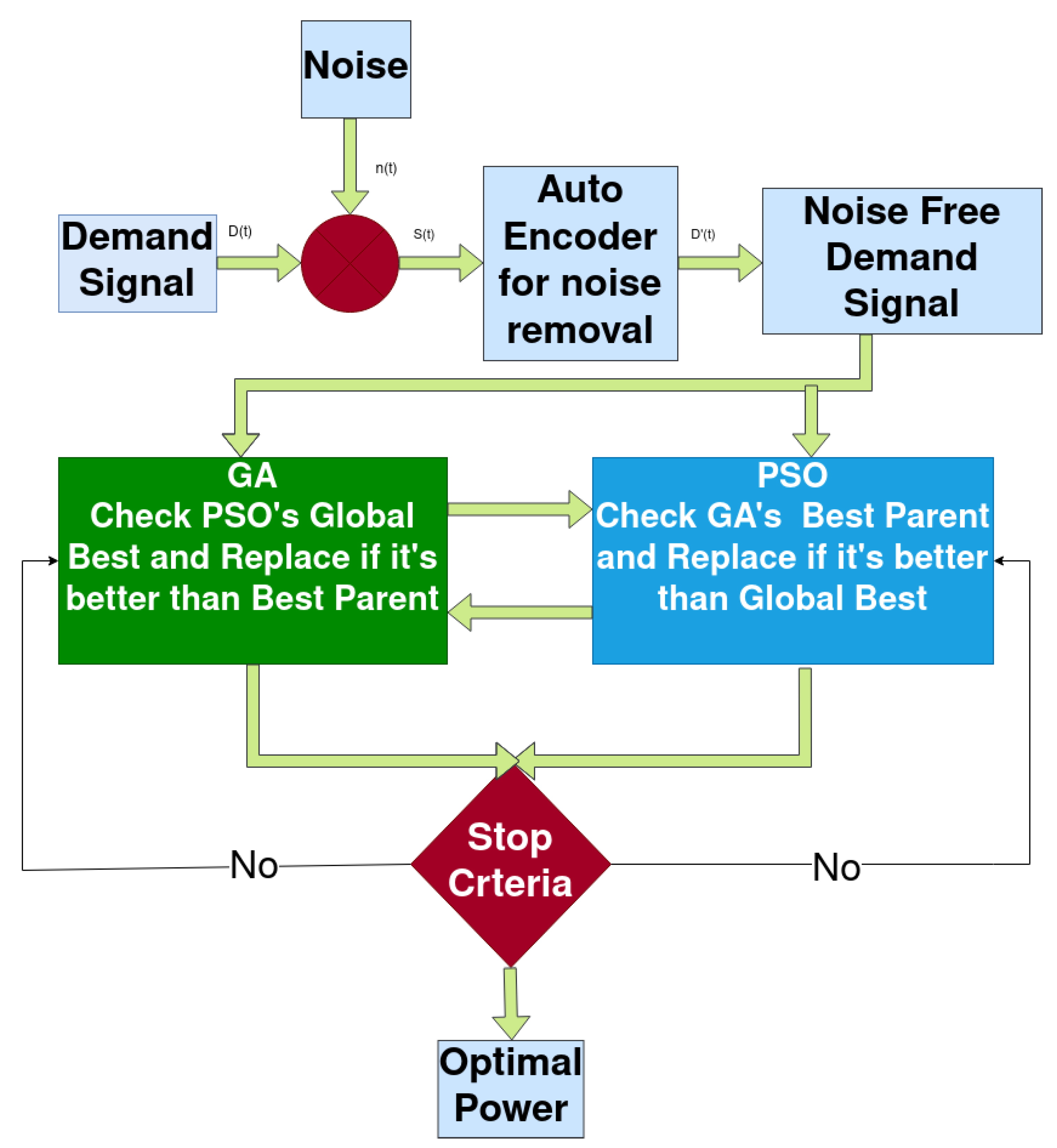

5.3. Parallel Heuristic Computation

The concurrent application of two heuristic computation algorithms, that are Genetic Algorithm and Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm, is performed on the power demand signal. The parallel performance of the proposed scheme follows the following steps.

- 1.

GA and PSO take the demand signal as input and run their first iteration and calculate the cost of power generation. GA calculates the best parents (BP), whereas the PSO finds its global best (GB) and both share their result with each other.

- 2.

Then the following comparisons are performed and the BP and GB are updated using the equation:

- 3.

Based on updated GB and BP, the genetic algorithm generates a new generation of solutions using mutation and crossover. Whereas, the PSO updates its particle’s position and velocity using Equations (1) and (2) respectively.

- 4.

Fitness of each solution is again tested for both GA and PSO. If the termination criteria is not reached, the algorithm repeats from step 2 again.

Utilizing Equation 9 to update the Global Best (GB) in Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and the Best Parent (BP) in Genetic Algorithm (GA) enhances the performance of the proposed system in two key ways. Firstly, it accelerates the convergence rate, making the algorithm more efficient. Secondly, it optimizes the cost of power generation when compared to running PSO and GA as standalone algorithms. Additionally, the incorporation of parallel processing significantly cuts down the computational time, offering a speed advantage over executing both algorithms sequentially, one after the other. Block diagram and pseudo code of proposed scheme is shown in

Figure 2 and

Table 1 respectively.

6. Simulations and Results

In this section, the simulation and results along with the comparison with the existing schemes are discussed.

6.1. Simulation Parameters

In this study, we employed the same parameters as those used in [

41]. While the prior research solely concentrated on a static load of 2000 MWatt, our study addresses variable loads. As a result, we introduced random load lines centered around 2000 MWatt. Each sample can fluctuate within a 10% tolerance of the 2000 MWatt benchmark. The previous research introduced an initial power, termed

. In our approach, the first sample retains this

value. However, from the second sample onward,

represents the optimized power generation of each generator from the preceding sample. We tested the algorithm on a load line of 10 samples, running it 500 times. The results were then averaged to validate the efficacy of our proposed method.

6.2. Results of Proposed Scheme

This section delves into the outcomes of the proposed scheme for the variable load line. The findings from this work can be categorized into two sub-sections. The first sub-section demonstrates the fesibility of using auto-encoder for noise mitigation. Meanwhile, the second sub-section explores the parallel utilization of two heuristic computation techniques that are GA and PSO.

6.2.1. Results of Auto-encoder

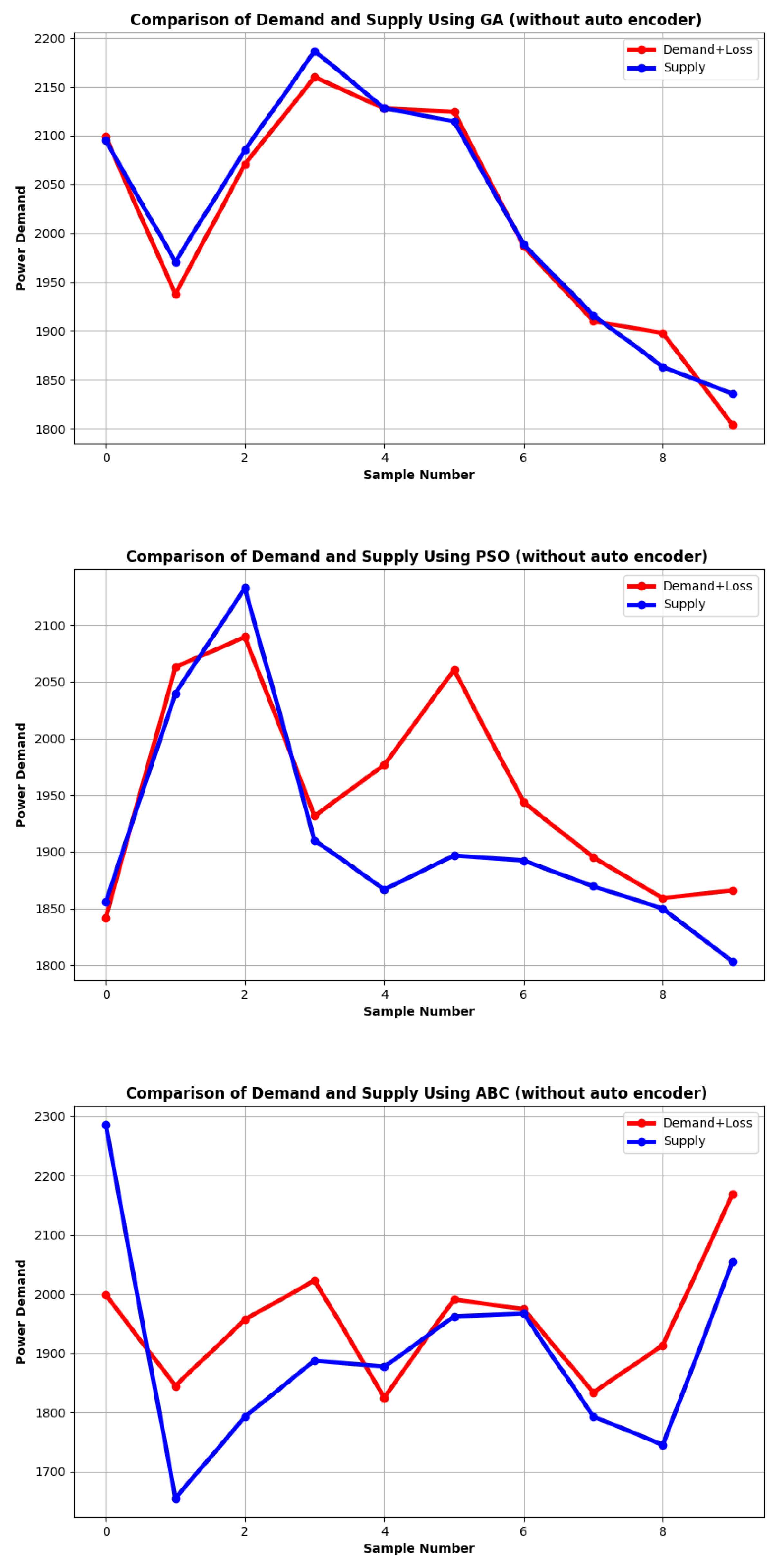

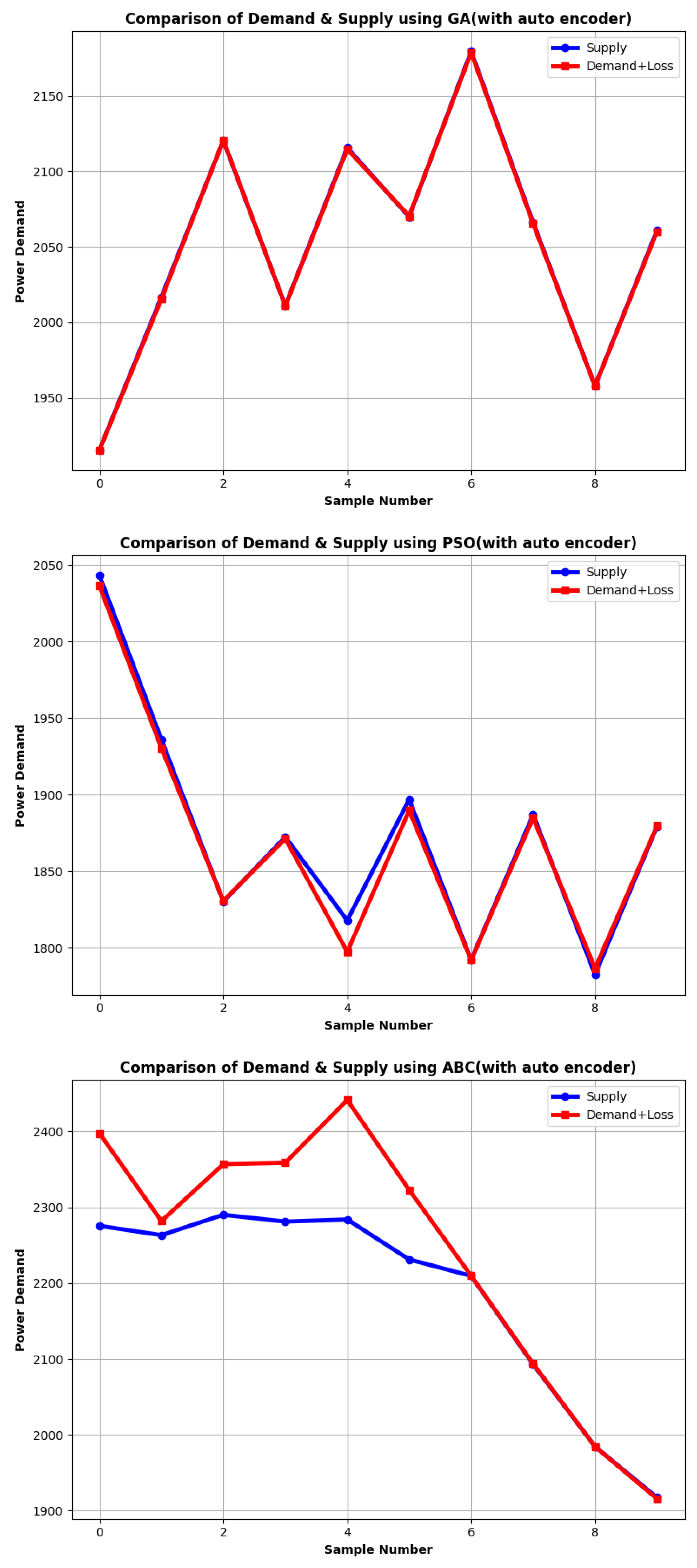

The auto-encoder plays a pivotal role in refining the noise within the demand signal, thereby facilitating a tighter alignment between the actual demand and power generated. Its significance becomes undeniably evident when observing the discrepancies between demand and supply across different algorithms in the absence of the auto-encoder. This mismatch can potentially undermine the entire power system’s stability, emphasizing the auto-encoder’s paramount importance.

Genetic Algorithm (GA): In

Figure 3a, the Genetic Algorithm (GA) is evaluated without the support of the auto-encoder. The detrimental influence of noise is evident as the GA struggles to accurately match the power demand. The distorted demand signal leads the GA away from its optimal solution. However, when the noise is filtered out using the auto-encoder, a stark improvement is witnessed.

Figure 4a showcases the GA’s refined performance, post noise-reduction. The difference between

Figure 3a and

Figure 4a is profound. With the noise mitigated, the GA’s results tightly align with the genuine demand, demonstrating the algorithm’s true capability when complemented by the auto-encoder.

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): Shifting to

Figure 3b, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm’s outcome under noisy conditions is highlighted. Much like the GA, PSO too grapples with the demand-signal noise, falling short of matching the genuine power demand. Yet, the narrative changes dramatically with the introduction of the auto-encoder.

Figure 4b contrasts starkly with its predecessor. The noise-filtered signal allows the PSO to achieve a closer alignment with the actual demand, validating the auto-encoder’s transformative impact.

Artificial Bee Colony (ABC): Lastly,

Figure 3c delves into the Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm’s performance devoid of the auto-encoder’s intervention. The noise within the demand signal poses challenges, creating a visible gap between demand and supply. The ABC, despite its efficient decision-making mechanism, cannot counteract the noise’s adverse effects. However, this scenario is upended in

Figure 4c. When synergized with the auto-encoder, the ABC algorithm’s optimization efforts witness a dramatic turnaround. The previously evident discrepancies nearly vanish, signifying the indispensable nature of the auto-encoder in power system optimization.

In essence, irrespective of the algorithm in use—be it GA, PSO, or ABC—the integration of the auto-encoder proves to be non-negotiable for optimal power demand alignment. It doesn’t merely bridge the gap between demand and supply but accentuates the intrinsic merits of each swarm intelligence algorithm, showcasing their peak potential in noise-free environments.

6.2.2. Parallel GA and PSO Performance Results

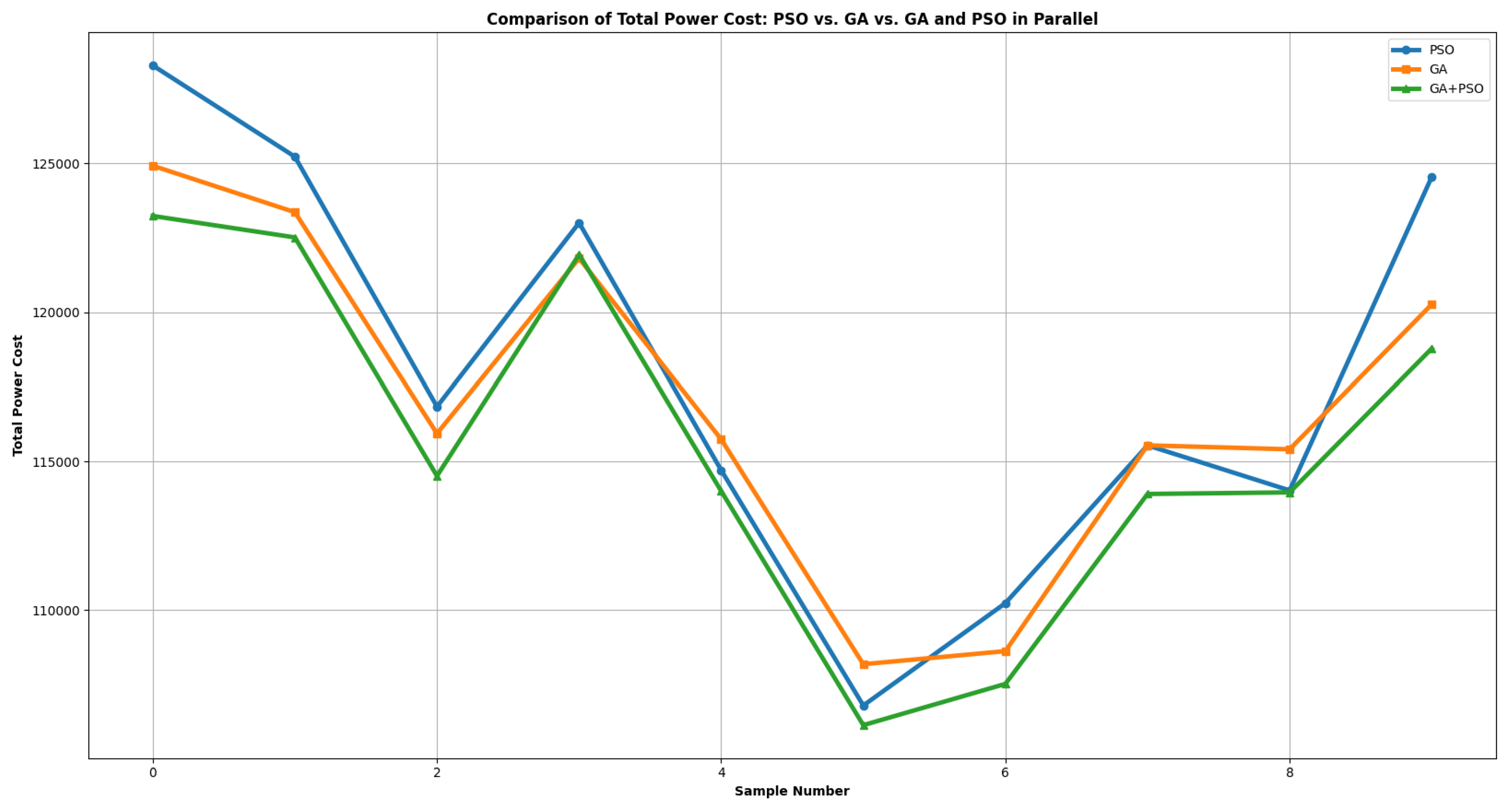

In this section, we discuss the results of employing parallel computing with both the genetic and PSO algorithms. The parallel execution of these algorithms have not only reduced the overall Cost required to achieve the required power but also reduced the computational time to achieve the optimal power of each each generator. Furthermore, the rate of convergence in parallel is also improved as compared to run these algorithms in series. These effects are discussed as follows.

Effect on Cost of Production

The effect of minimization of cost of production is shown in

Figure 5, the blue line represents the PSO algorithm’s outcome, while the orange line depicts the performance of the genetic algorithm. The green line demonstrates the cost obtained when both models run concurrently, sharing their global best and best parent at each iteration. Notably, the combined parallel processing of both algorithms frequently surpasses the individual performances of either the Genetic or PSO algorithm.

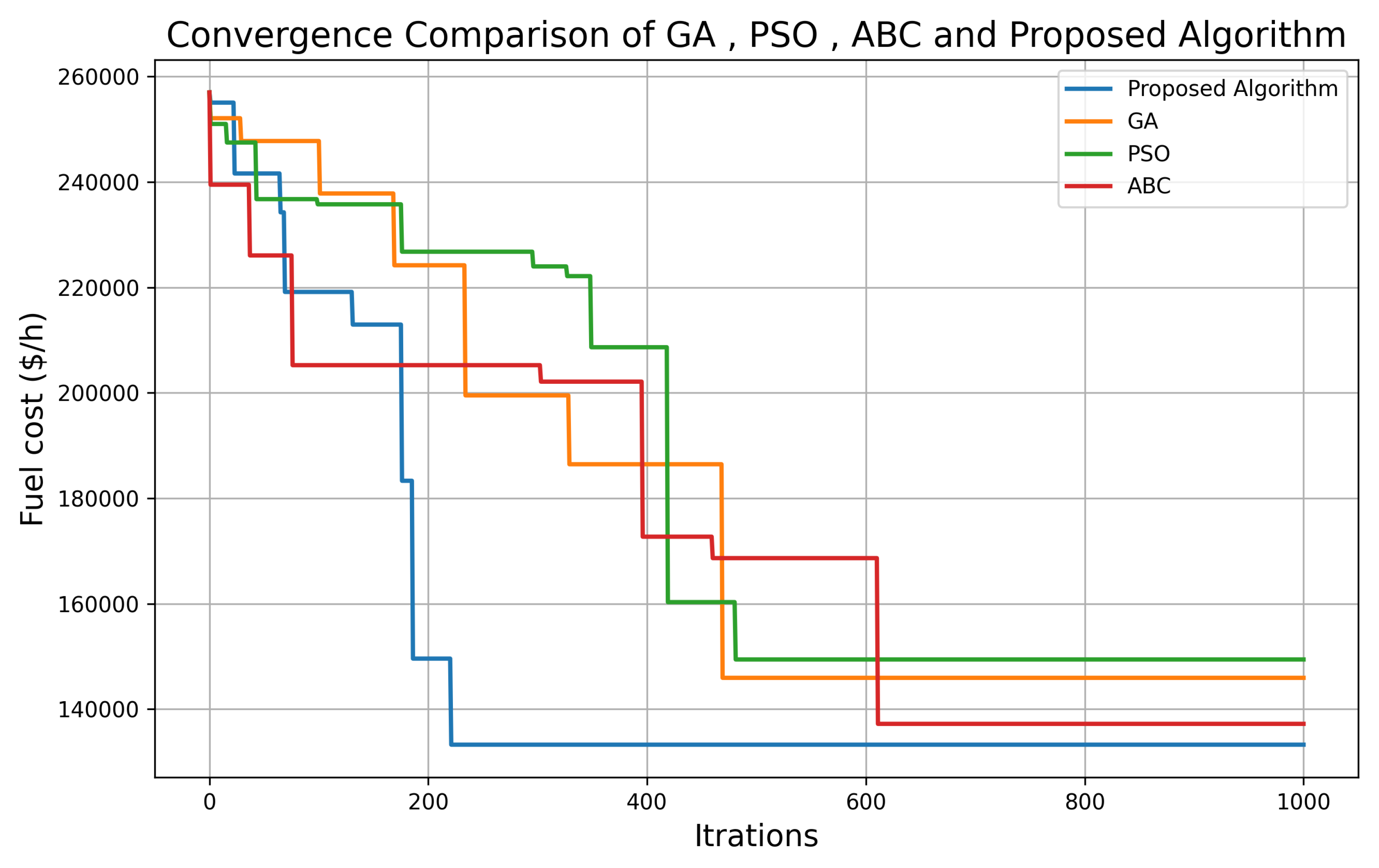

6.3. Analysis of Convergence Rates

The convergence rate of an optimization algorithm is instrumental in determining how expeditiously the algorithm approaches the optimal or near-optimal solution. To elucidate the distinctions in convergence rates between various algorithms, we undertook a meticulous comparison encompassing the Genetic Algorithm (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) algorithm, and our proposed parallel scheme integrating GA and PSO.

Referring to the accompanying figures that delineate the convergence trajectories, it’s evident that each algorithm manifests distinct convergence profiles. As presented in

Figure 6, the GA achieves its nadir in power cost subsequent to 400 iterations. Similarly,

Figure 6 illustrates that PSO, mirroring GA, also settles at its minimum post 400 iterations. On the contrary, the ABC algorithm, depicted in

Figure 6, showcases a more protracted convergence, reaching its optimal power cost after 550 iterations.

The focal point, however, remains our proposed algorithm which amalgamates GA and PSO in a parallelized manner, depicted in

Figure 6. Notably, this algorithm flaunts a precipitous convergence rate, attaining the optimal cost value after a mere 220 iterations. This rate of convergence is markedly swifter in comparison to the extant algorithms, being approximately twice as nimble as both GA and PSO, and more than double in celerity compared to ABC.

This accelerated convergence is scientifically pivotal. It intimates that the proposed scheme is not only proficient in economizing computational resources but also remarkably time-efficient. This is particularly salient in dynamic milieus where power demand oscillates, necessitating brisk optimizations. The pronounced convergence of our scheme also suggests its adeptness at swiftly acclimatizing to novel conditions, thereby assuring optimal power dispatch even under mutable circumstances, and hence amplifying the overarching reliability and efficacy of the power system.

In encapsulation, our proposed parallel framework unambiguously evinces superlative efficacy, demonstrating a convergence rate that stands head and shoulders above conventional algorithms, thereby underscoring its potency and adaptability in catering to optimal power dispatch challenges in variable load scenarios.

6.4. Comparison

Each row of

Table 2, designated by Generator No. from P1 to P10, demonstrates the generated power (in MW) and associated fuel cost (in

$/h) for that specific generator. The results are segmented between the ABC algorithm, GA, PSO, and the proposed scheme.

For instance, generator P1 under the ABC algorithm generated 254.3231 MW of power at a fuel cost of $20853.6661 per hour. In contrast, under the proposed scheme, the same generator produced 241.6069 MW but at a reduced fuel cost of $19781.0829 per hour. Similarly, under GA and PSO, the generator produced 303.0601 MW and 310.6411 MW at a fuel cost of $26467.3592 and $27138.9479 per hour respectively.

As we traverse the table, a consistent trend emerges across all algorithms. However, the proposed scheme demonstrates a unique edge. In every instance, the proposed scheme either reduces power generation to optimize cost or manages to generate more power with a better or comparable fuel cost. A prime example is generator P9, where the proposed scheme, even with an increased power output of 132.5667 MW compared to ABC’s 80.0000 MW, achieved a higher fuel cost. However, when assessed holistically over all generators, the overall fuel cost for the proposed scheme remains less than that of the ABC, GA, and PSO.

The penultimate row aggregates the results, highlighting that while the proposed scheme generated a slightly lower total power (2010.9204 MW) than the ABC (2078.1428 MW), GA (2079.95 MW), and PSO (2135.59 MW), it achieved a notably lesser fuel cost. Specifically, the proposed scheme incurred a fuel cost of $133251.8922, which is roughly $4000 less than the ABC’s total fuel cost of $137203.5121, and significantly lower than the fuel costs incurred by GA ($145933.16) and PSO ($149416.82).

Additionally, a pivotal metric to consider is the total power loss. The ABC had a significant power loss of 78.1428 MW, which is notably higher than the power loss of just 10.9204 MW for the proposed scheme. GA and PSO also experienced higher power losses of 79.95 MW and 81.59 MW respectively, further showcasing the efficiency of the proposed scheme.

In summary,

Table 2 underscores the efficacy of the proposed scheme against ABC, GA, and PSO. While both the total generated power and fuel cost might be the immediate metrics of interest, it’s the optimized balance between them that’s critical. Not only does the proposed scheme consistently reduce fuel costs across the majority of generators, but it also minimizes power losses, solidifying its superior performance against the Artificial Bee Colony algorithm, Genetic Algorithm, and Particle Swarm Optimization.

7. Conclusions

In the ever-changing landscape of energy dynamics, Economic Load Dispatch (ELD) emerges as a complex optimization puzzle within power systems. Conventional methodologies grapple with its intricate non-smooth and non-linear characteristics, prompting a shift towards heuristic strategies such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO). Nevertheless, these approaches face susceptibility to noise interference in scenarios marked by fluctuating loads.

To tackle these intricate challenges, our research introduces a two-fold solution. Initially, we employ an auto-encoder to proficiently eliminate noise from demand signals, bolstering system security. Subsequently, our Multi-Algorithm Approach combines GA and PSO in parallel, streamlining convergence and cost reduction. This innovative scheme showcases both resilience and efficiency, offering promising prospects for advancing power system optimization. These pioneering advancements carry substantial potential to enhance the efficiency and resilience of power systems, particularly when navigating variable loads and potential noise disturbances.

References

- Aslam, L.; Zou, R.; Awan, E.S.; Hussain, S.S.; Shakil, K.A.; Wani, M.A.; Asim, M. Hardware-Centric Exploration of the Discrete Design Space in Transformer–LSTM Models for Wind Speed Prediction on Memory-Constrained Devices. Energies 2025, 18, 2153. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, L.; Saeed, A.; Qureshi, I.M.; Amir, M.; Khan, W. Novel Image Steganography Based on Preprocessing of Secret Messages to Attain Enhanced Data Security and Improved Payload Capacity. Traitement du Signal 2020, 37. Image steganography hides secret messages in cover images by manipulating their content. There is a fundamental requirement of maximizing secrecy and payload capacity. This paper presents a novel algorithm for achieving two-layer security as well as improved payload capacity by preprocessing the secret images before hiding them in a cover image.

- Aslam, L.; Zou, R.; Awan, E.; Butt, S.A. Integrating Physics-Informed Vectors for Improved Wind Speed Forecasting with Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 14th Asian Control Conference (ASCC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1902–1907.

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. Artificial bee colony (ABC) optimization algorithm for solving constrained optimization problems 2007.

- He, X.; Rao, Y.; Huang, J. A novel algorithm for economic load dispatch of power systems 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Li, C. Short-term real-power scheduling considering fuzzy factors in an autonomous system using genetic algorithms 2006. [CrossRef]

- Roa-Sepulveda, C.; Pavez-Lazo, B. A solution to the optimal power flow using simulated annealing 2003. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, H.A.; Aslam, L.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Chaudhary, N.I.; Qureshi, I.M.; Malik, A.N. A New Computing Paradigm for Off-Grid Direction of Arrival Estimation Using Compressive Sensing. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2020, 2020, 9280198. [CrossRef]

- Durrani, F.A.K.; Baseer, S.; Mehmood, A.; Mehr-e Munir, L.A. REMOVAL OF ECG SIGNALS ARTIFACTS USING MULTISTAGE ADAPTIVE FILTERING TECHNIQUE.

- Aslam, L.; Ahmad, F.; Akhtar, S.; Awan, E.S.; Yaqoob, F. EFFECT OF FAULTY SENSORS ON ESTIMATION OF DIRECTION OF ARRIVAL AND OTHER PARAMETERS.

- Warsono, W.; Ozveren, C.; King, D.; Bradley, D. A review of the use of genetic algorithms in economic load dispatch 2008.

- Abido, M. A novel multiobjective evolutionary algorithm for environmental/economic power dispatch 2003. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Kheradmandi, M. Dynamic economic dispatch in restructured power systems considering transmission costs using genetic algorithm 2004.

- Safari, A.; Shayeghi, H. Iteration particle swarm optimization procedure for economic load dispatch with generator constraints 2011. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, M.; Roy, P.; Pal, T. Grey wolf optimization applied to economic load dispatch problems 2016. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic algorithms in search, optimization, and machine learning. Addison-Wesley Professional 1989.

- Mitchell, M. An introduction to genetic algorithms; MIT press, 1998.

- Hassan, A.M.; Zhou, X.; Aslam, L. Exploring New Frontiers in Facial Expression Recognition: Dual DenseNet-201 and Landmark Distance Analytics in the Wild. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 13th Data Driven Control and Learning Systems Conference (DDCLS), Kaifeng, China, 2024; pp. 2036–2043. [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in natural and artificial systems: an introductory analysis with applications to biology, control, and artificial intelligence 1992.

- Abido, M.A. Optimal power flow using particle swarm optimization. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2002, 24, 563–571.

- Wang, L.; Singh, C. Hybrid differential evolution with bi-population for multi-objective optimal power flow. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2008, 23, 71–78.

- Reddy, S.S.; Bijwe, P.R. Genetic algorithm solution to the unit commitment problem. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2007, 1, 382–392.

- Oka, K.; Tominaga, Y.; Iba, K. Multi-objective optimal power flow using different variants of NSGA-II. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2014, 55, 283–291.

- Yang, C.S.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.H. Real-time power system economic dispatch using genetic algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems 2013, 28, 356–366.

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. Proceedings of ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks 1995, pp. 1942–1948.

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R.C. Parameter selection in particle swarm optimization. Evolutionary programming VII 1998, 1447, 591–600.

- Poli, R.; Kennedy, J.; Blackwell, T. Particle swarm optimization—an overview. Swarm intelligence 2007, 1, 33–57.

- Zhang, W.; Xie, X. Adaptive particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Computational Intelligence in Robotics and Automation, 2003. Proceedings. IEEE, 2003, pp. 27–32.

- Eldahab, Y.; Abido, M. Enhanced particle swarm optimization for multi-objective optimal power flow with wind and thermal generators. Electric Power Systems Research 2016, 140, 418–430.

- Liang, Y.C.; Reeves, D.S. Particle swarm optimization-based algorithms for grid scheduling. Future Generation Computer Systems 2006, 22, 271–283.

- Karaboga, D. An idea based on honey bee swarm for numerical optimization. Technical report-tr06, Erciyes university, engineering faculty, computer engineering department 2005.

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. A powerful and efficient algorithm for numerical function optimization: artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. Journal of global optimization 2007, 39, 459–471. [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D.; Basturk, B. On the performance of artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. Applied soft computing 2008, 8, 687–697. [CrossRef]

- Abido, M.A. Multiobjective optimal VAR dispatch using strength pareto evolutionary algorithm. Electric Power Systems Research 2009, 79, 959–971.

- Gao, L.; Sheble, G.B.; Ma, J.; Zhang, M. Optimal active power flow incorporating shunt FACTS devices by modified artificial bee colony algorithm. Energy Conversion and Management 2010, 51, 995–1001.

- Vincent, P.; Larochelle, H.; Bengio, Y.; Manzagol, P.A. Extracting and composing robust features with denoising autoencoders. Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Machine learning 2008, pp. 1096–1103.

- Bengio, Y.; Yao, L.; Alain, G.; Vincent, P. Generalized denoising auto-encoders as generative models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2013, 26.

- Xie, J.; Xu, L.; Chen, E. Image denoising and inpainting with deep neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems 2012, 25, 341–349.

- Masci, J.; Meier, U.; Ciresan, D.; Schmidhuber, J. Stacked convolutional auto-encoders for hierarchical feature extraction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks. Springer, 2011, pp. 52–59.

- Zhou, D.; Krähenbühl, P.; Aubry, M.; Huang, Q.; Efros, A.A. Image restoration using convolutional auto-encoders with symmetric skip connections. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08921 2016.

- Hanif, M.; Mohammad, N. Artificial Bee Colony and Genetic Algorithm for Optimization of Non-smooth Economic Load Dispatch with Transmission Loss. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Big Data, IoT, and Machine Learning: BIM 2021. Springer, 2022, pp. 271–287.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).