Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Components of LPOS

2.1. Lactoperoxidase

| LPO activity (Units/mL) | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Cow | 1.4 | [42] |

| Ewe | 0.14-2.38 | [43] |

| Goat | 1.55 | [44] |

| 4.45 | [45] | |

| Buffalo | 0.9 | [46] |

| Guinea Pig | 22 | [42] |

| Human | 0.06-0.97 | [41] |

| Limit for bactericidal activity | 0.02 | [1] |

2.2. Thiocyanate (SCN-)

2.3. Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

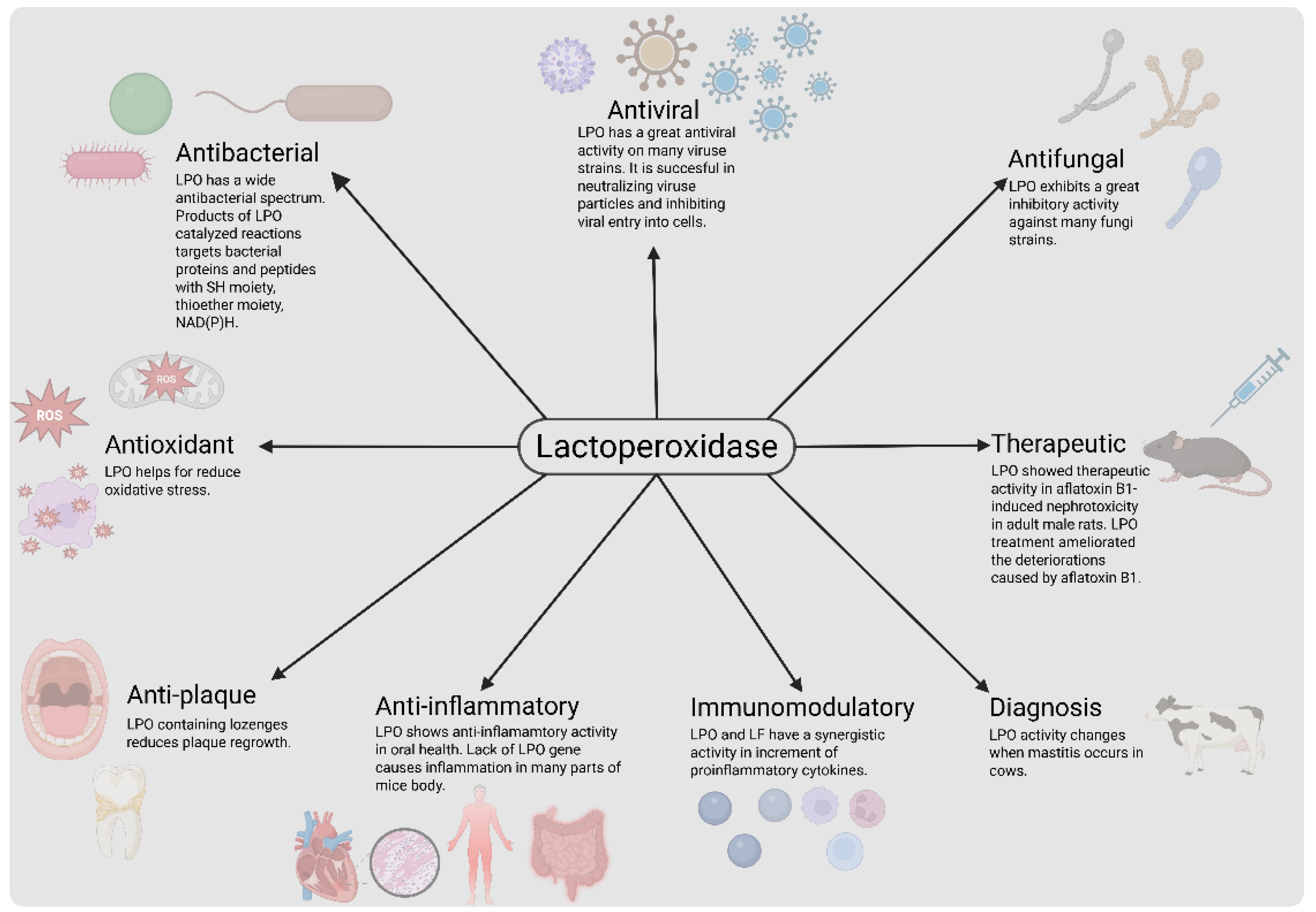

3. Biological Functions of LPO

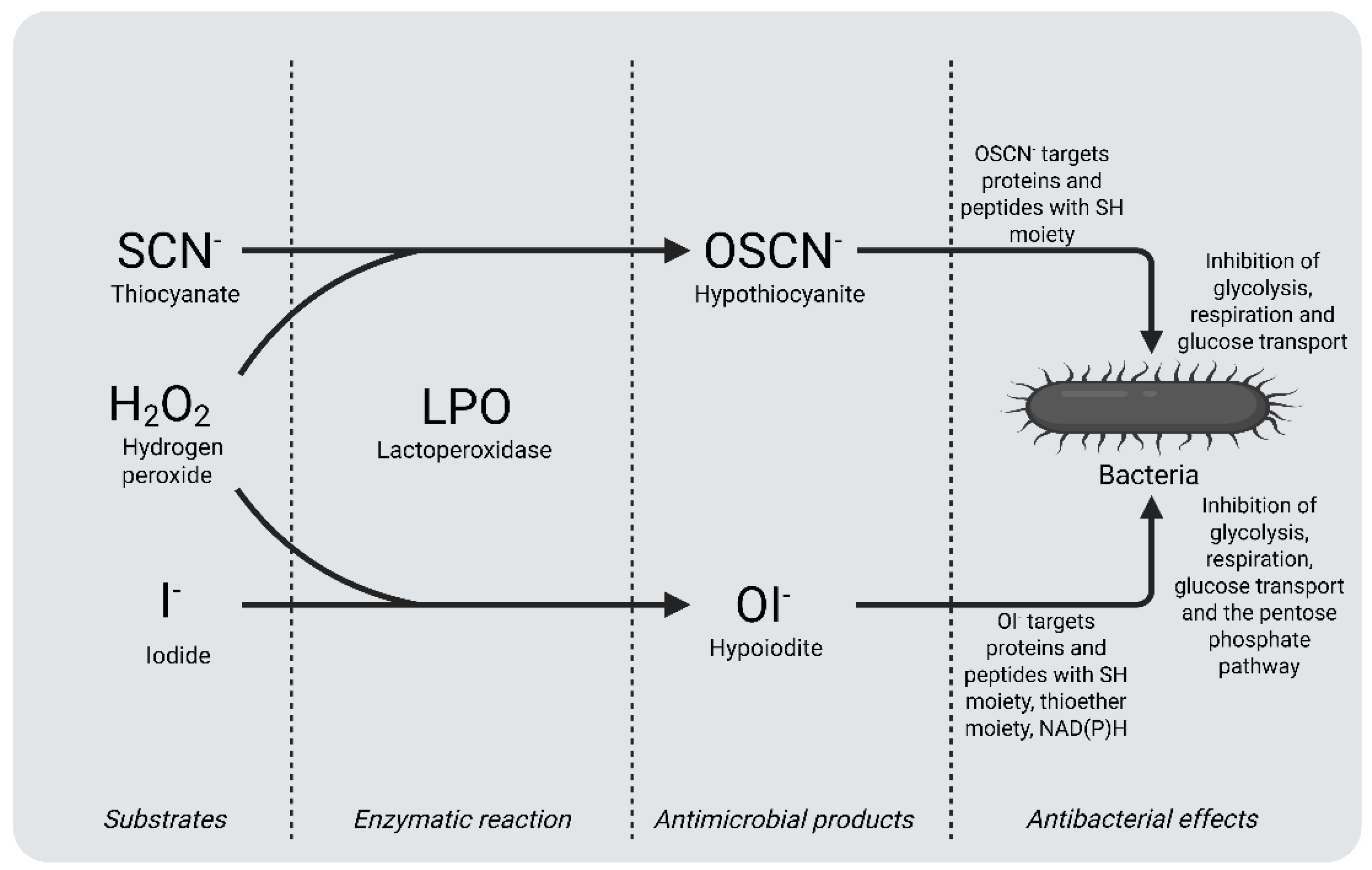

3.1. Antibacterial Properties of LPO

3.1.1. Antibacterial Properties of LPO in Milk and Milk Products

3.1.2. Antibacterial Properties of LPO in Meat and Meat Products

3.1.3. Antibacterial Properties of LPO in Oral Health

3.2. Antiviral Properties of LPO

3.3. Antifungal Properties of LPO

3.4. Other Properties of LPO

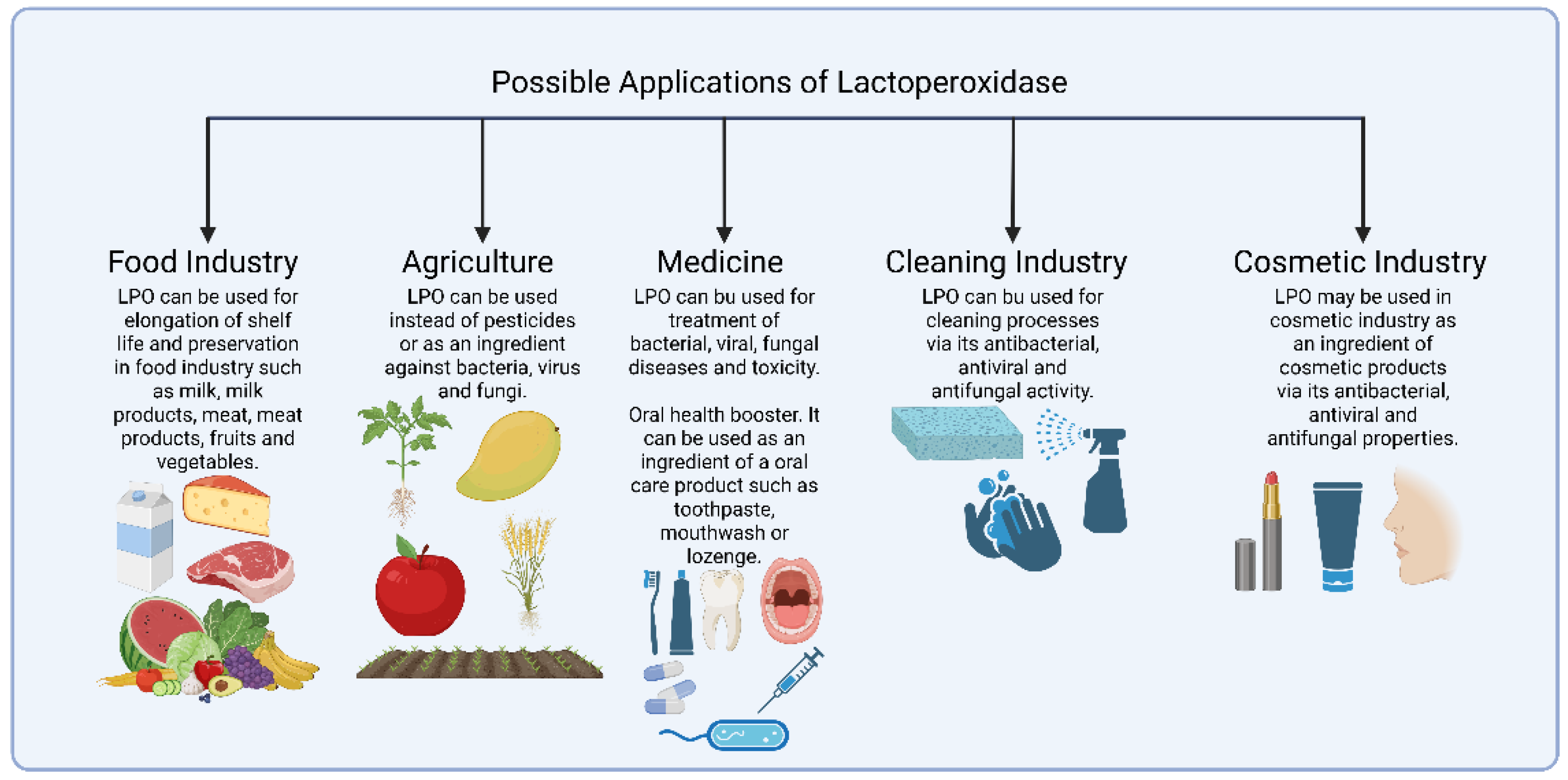

4. Potential Applications of Lactoperoxidase

5. Conclusion and Future Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reiter, B.; Harnulv, G. Lactoperoxidase Antibacterial System: Natural Occurrence, Biological Functions and Practical Applications; 1984; Vol. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Seifu, E.; Buys, E.M.; Donkin, E. Significance of the lactoperoxidase system in the dairy industry and its potential applications: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, Z.; Gulcin, I.; Ozdemir, H. An Important Milk Enzyme: Lactoperoxidase. In Milk Proteins - From Structure to Biological Properties and Health Aspects; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, A.K.; Kaushik, S.; Sinha, M.; Singh, R.P.; Sharma, P.; Sirsohi, H.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.P. Lactoperoxidase: Structural Insights into the Function, Ligand Binding and Inhibition. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2013, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ihalin, R.; Pienihäkkinen, K.; Lenander, M.; Tenovuo, J.; Jousimies-Somer, H. Susceptibilities of different Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans strains to lactoperoxidase–iodide–hydrogen peroxide combination and different antibiotics. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2003, 21, 434–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashenafi, T.; Zebib, H.; Woldegiorgis, A.Z. Improvement of Raw and Pasteurized Milk Quality through the Use of Lactoperoxidase Systems (LPSs) along the Dairy Value Chain, under Real Conditions in Ethiopia. Foods 2024, 13, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beňo, F.; Velková, A.; Hruška, F.; Ševčík, R. Use of Lactoperoxidase Inhibitory Effects to Extend the Shelf Life of Meat and Meat Products. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dashe, D.; Hansen, E.B.; Kurtu, M.Y.; Berhe, T.; Eshetu, M.; Hailu, Y.; Waktola, A.; Shegaw, A. Preservation of Raw Camel Milk by Lactoperoxidase System Using Hydrogen Peroxide Producing Lactic Acid Bacteria. Open J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 10, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, S.; da Silva, C.C.; da Silva, L.; Cicotti, M.P. Antimicrobial Capacity of a Hydroxyapatite–Lysozyme–Lactoferrin–Lactoperoxidase Combination Against Streptococcus mutans for the Treatment of Dentinal Caries. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molayi, R.; Ehsani, A.; Yousefi, M. The antibacterial effect of whey protein–alginate coating incorporated with the lactoperoxidase system on chicken thigh meat. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 878–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baarri, A.N.M.; Legowo, A.M.; Arum, S.K.; Hayakawa, S. Extending Shelf Life of Indonesian Soft Milk Cheese (Dangke) by Lactoperoxidase System and Lysozyme. Int J Food Sci 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Farshidi, M.; Ehsani, A. Effects of lactoperoxidase system-alginate coating on chemical, microbial, and sensory properties of chicken breast fillets during cold storage. J. Food Saf. 2018, 38, e12449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welk, A.; Patjek, S.; Gärtner, M.; Baguhl, R.; Schwahn, C.; Below, H. Antibacterial and antiplaque efficacy of a lactoperoxidase-thiocyanate-hydrogen-peroxide-system-containing lozenge. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, M.; Yoshida, A.; Wakabayashi, H.; Tanaka, M.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F.; Masuda, Y. Effect of tablets containing lactoferrin and lactoperoxidase on gingival health in adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Periodontal Res. 2019, 54, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, L.; Mahdi, N.; Al-Kakei, S.; Musafer, H.; Al-Joofy, I.; Essa, R.; Zwain, L.; Salman, I.; Mater, H.; Al-Alak, S.; et al. Treatment strategy by lactoperoxidase and lactoferrin combination: Immunomodulatory and antibacterial activity against multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 114, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, U.; Gingerich, A.; Widman, L.; Sarr, D.; Tripp, R.A.; Rada, B. Susceptibility of influenza viruses to hypothiocyanite and hypoiodite produced by lactoperoxidase in a cell-free system. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0199167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Ye, X.; Ng, T.B. Pharmacology Letters Accelerated Communication First Demonstration of an Inhibitory Activity of Milk Proteins against Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Reverse Transcriptase and the Effect of Succinylation; 2000; Vol. 67.

- Smith, M.L.; Sharma, S.; Singh, T.P. High dietary iodine intake may contribute to the low death rate from COVID-19 infection in Japan with activation by the lactoperoxidase system. Scand. J. Immunol. 2023, 98, e13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kho, H.-S.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Chang, J.-Y.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, S.-G. Candidacidal activities of the glucose oxidase-mediated lactoperoxidase system. Arch. Oral Biol. 2012, 57, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, C.; Elise, N.; Etienne, T.V.; Loiseau, G.; Montet, D. Antifungal activity of edible coating made from chitosan and lactoperoxidase system against Phomopsis sp. RP257 and Pestalotiopsis sp. isolated from mango. J. Food Saf. 2020, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussendrager, K.D.; Van Hooijdonk, A.C.M. Lactoperoxidase: Physico-Chemical Properties, Occurrence, Mechanism of Action and Applications. British Journal of Nutrition 2000, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, K. Therapeutic applications of whey protein. Alternative Medicine Review 2004, 9, 136–56. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, E.P.E.; Moraes, E.P.; Anaya, K.; Silva, Y.M.O.; Lopes, H.A.P.; Neto, J.C.A.; Oliveira, J.P.F.; Oliveira, J.B.; Rangel, A.H.N. Lactoperoxidase potential in diagnosing subclinical mastitis in cows via image processing. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0263714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köksal, Z.; Usanmaz, H.; Özdemir, H.; Gülçin, I.; Güney, M. Inhibition effects of some phenolic and dimeric phenolic compounds on bovine lactoperoxidase (LPO) enzyme. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2014, 6, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemi̇r, H.; Uğuz, M.T. In vitroeffects of some anaesthetic drugs on lactoperoxidase enzyme activity. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2005, 20, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisecioglu, M.; Cankaya, M.; Ozdemir, H. Effects of Some Vitamins on Lactoperoxidase Enzyme Activity. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2009, 79, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şisecioglu, M.; Gülçin, I.; Çankaya, M.; Ozdemir, H. The Inhibitory Effects of L-Adrenaline on Lactoperoxidase Enzyme Purified from Bovine Milk. Int. J. Food Prop. 2012, 15, 1190–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, I.; Çankaya, M.; Sisecioglu, M.; Gulcin, I.; Cankaya, M.; Atasever, A.; Ozdemir, H. The Effects of Norepinephrine on Lactoperoxidase Enzyme (LPO). Scientific Research and Essays 2010, 5, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar]

- Yata, M.; Sato, K.; Ohtsuki, K.; Kawabata, M. Fractionation of Peptides in Protease Digests of Proteins by Preparative Isoelectric Focusing in the Absence of Added Ampholyte: A Biocompatible and Low-Cost Approach Referred to as Autofocusing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazaki, K.; Nishio, M.; Kawano, N. Separation of Biologically Active Proteins from Whey. Rakuno Kagaku, Shokuhin no Kenkyu 1988, 37, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Uguz, M.T.; Ozdemir, H. Purification of Bovine Milk Lactoperoxidase and Investigation of Antibacterial Properties at Different Thiocyanate Mediated. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2005, 41, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Hayasawa, H.; Lönnerdal, B. Purification and quantification of lactoperoxidase in human milk with use of immunoadsorbents with antibodies against recombinant human lactoperoxidase. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langbakk, B.; Flatmark, T. Lactoperoxidase from human colostrum. Biochem. J. 1989, 259, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasever, A.; Ozdemir, H.; Gulcin, I.; Kufrevioglu, O.I. One-step purification of lactoperoxidase from bovine milk by affinity chromatography. Food Chem. 2013, 136, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.K.; Pandey, S.; Rani, C.; Ahmad, N.; Viswanathan, V.; Sharma, P.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, S.; Singh, T.P. Potassium-induced partial inhibition of lactoperoxidase: structure of the complex of lactoperoxidase with potassium ion at 2.20 Å resolution. JBIC J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 26, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Smith, M.L.; Yamini, S.; Ohlsson, P.-I.; Sinha, M.; Kaur, P.; Sharma, S.; Paul, J.A.K.; Singh, T.P.; Paul, K.-G. Bovine Carbonyl Lactoperoxidase Structure at 2.0Å Resolution and Infrared Spectra as a Function of pH. Protein J. 2012, 31, 598–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magacz, M.; Kędziora, K.; Sapa, J.; Krzyściak, W. The Significance of Lactoperoxidase System in Oral Health: Application and Efficacy in Oral Hygiene Products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel-ur-Rehman; Farkye, N.Y. Lactoperoxidase. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Science; Roginski, R., Fuquay, J.W., Fox, P.F., Eds.; Academic Press, 2003; pp. 939–941. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, K.G.; Ohlsson, P.I. The Chemical Structure of Lactoperoxidase. In The lactoperoxidase system: Chemistry and biological significance; Pruitt, K.M., Tenovuo, J.O., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, 1985; pp. 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Colas, C.; Kuo, J.M.; de Montellano, P.R.O. Asp-225 and Glu-375 in Autocatalytic Attachment of the Prosthetic Heme Group of Lactoperoxidase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 7191–7200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, B. Lactoperoxidase System of Bovine Milk. In The Lactoperoxidase System: Chemistry and Biological Significance; Pruitt, K.M., Tenovuo, J.O., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, 1985; pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, S.; Harkness, R.; Cockle, S. Lactoperoxidase Activity in Guinea-Pig Milk and Saliva: Correlation in Milk of Lactoperoxidase with Bactericidal Activity against Escherichia coli. Br J Exp Pathol 1979, 60, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Medina, M.; Gaya, P.; Nuñez, M. The lactoperoxidase system in ewes' milk: levels of lactoperoxidase and thiocyanate. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1989, 8, 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapico, P.; Gaya, P.; Nuñez, M.; Medina, M. Lactoperoxidase and thiocyanate contents of goats' milk during lactation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1990, 11, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Schoos, S.S.; Oliver, G.; Fernandez, F. Relationships between lactoperoxidase system components in Creole goat milk. Small Rumin. Res. 1999, 32, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härnulv, G.; Kandasamy, C. Increasing the Keeping Quality of Milk by Activation of Its Lactoperoxidase System: Results from Sri Lanka. Milchwissenschaft 1982, 37, 454–457. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T.; Sakamaki, K.; Kuroki, T.; Yano, I.; Nagata, S. Molecular Cloning and Characterization of the Chromosomal Gene for Human Lactoperoxidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997, 243, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fragoso, M.A.; Torbati, A.; Fregien, N.; Conner, G.E. Molecular heterogeneity and alternative splicing of human lactoperoxidase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 482, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheikh, I.A.; Jiffri, E.H.; Ashraf, G.M.; Kamal, M.A. Structural insights into the camel milk lactoperoxidase: Homology modeling and molecular dynamics simulation studies. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2019, 86, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, M.W. Copyright® International Association of Miik; 1986; Vol. 49.

- Wolfson, L.M.; Sumner, S.S. Copyright©, International Association of Milk; 1993; Vol. 56.

- Marks, N.; Grandison, A.; Lewis, M. Challenge testing of the lactoperoxidase system in pasteurized milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 91, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, P.M. Chemical Preservatives and Natural Antimicrobial Compounds. In Food Microbiology: Fundamentals and Frontiers; Doyle, M.P., Beuchat, L.R., Montville, T.J., Eds.; ASM Press, 1997; pp. 520–556. [Google Scholar]

- Björck, L.; Claesson, O.; Schuthes, W. The Lactoperoxidase-Thiocyanate-Hydrogen Peroxide System as a Temporary Preservative for Raw Milk in Developing Countries. Milchwissenschaft 1979, 34, 726–729. [Google Scholar]

- Korhonen, H. A New Method for Preserving Raw Milk—The Lactoperoxidase Antibacterial System. World Animal Review 1980, 35, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Metwally, M.M.K.; Nasr, M.M. Preservation of Raw Milk by Activation of the Lactoperoxidase System: Review Article. Egyptian Journal of Food Science 1992, 20, 175–196. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 3rd ed.; Clarendon Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B.; Clement, M.V.; Long, L.H. Hydrogen peroxide in the human body. FEBS Lett. 2000, 486, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, B.M.; Antony, E.; Haridas’, M. THIOCYANATE MEDIATED ANTIFUNGAL AND ANTIBACTERIAL PROPERTY OF GOAT MILK LACTOPEROXIDASE; Ehvier S&m Inc, 2000; Vol. 66.

- Cissé, M.; Polidori, J.; Montet, D.; Loiseau, G.; Ducamp-Collin, M.N. Preservation of mango quality by using functional chitosan-lactoperoxidase systems coatings. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 101, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, M.; Suzuki, M.; Wakabayashi, H.; Hayama, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Abe, F.; Abe, S. Synergistic anti-candida activities of lactoferrin and the lactoperoxidase system. Drug Discov. Ther. 2019, 13, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redwan, E.M.; Almehdar, H.A.; El-Fakharany, E.M.; Baig, A.-W.K.; Uversky, V.N. Potential antiviral activities of camel, bovine, and human lactoperoxidases against hepatitis C virus genotype 4. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 60441–60452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Fakharany, E.M.; Uversky, V.N.; Redwan, E.M. Comparative Analysis of the Antiviral Activity of Camel, Bovine, and Human Lactoperoxidases Against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016, 182, 294–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamakaze, J.; Lu, Z. Deletion of the lactoperoxidase gene causes multisystem inflammation and tumors in mice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.E.M.; Soliman, S.M.; Ashry, M. Therapeutic and antioxidant effects of lactoperoxidase on aflatoxin B1-induced nephrotoxicity in adult male rats. Egypt. Pharm. J. 2024, 23, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafort, F.; Parisi, O.; Perraudin, J.-P.; Jijakli, M.H. Mode of Action of Lactoperoxidase as Related to Its Antimicrobial Activity: A Review. Enzym. Res. 2014, 2014, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S. Microbiological Considerations: Pasteurized Milk. Int. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 10, 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deising, H.B.; Reimann, S.; Sérgio; Pascholati, S.F. MECHANISMS AND SIGNIFICANCE OF FUNGICIDE RESISTANCE. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology 2008, 39, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.A.; Hawkins, N.J.; Fraaije, B.A. The Evolution of Fungicide Resistance. Adv Appl Microbiol 2015, 90, 29–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollomon, D.W. Fungicide resistance: facing the challenge - a review. Plant Prot. Sci. 2015, 51, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalidis, G.A. Human Health and Ecosystem Quality Benefits with Life Cycle Assessment Due to Fungicides Elimination in Agriculture. Sustainability 2022, 14, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, D.B. Derivatives and kinetics of lactoperoxidase. Biochem. J. 1954, 56, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, M.; Hamilton, H.; Stotz, E. The Isolation And Purification Of Lactoperoxidase By Ion Exchange Chromatography. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 228, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Gunzburg, J.; Ghozlane, A.; Ducher, A.; Le Chatelier, E.; Duval, X.; Ruppé, E.; Armand-Lefevre, L.; Sablier-Gallis, F.; Burdet, C.; Alavoine, L.; et al. Protection of the Human Gut Microbiome From Antibiotics. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 217, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezie, A. The Effect of Different Heat Treatment on the Nutritional Value of Milk and Milk Products and Shelf-Life of Milk Products. A Review. J. Dairy Veter- Sci. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peila, C.; Moro, G.E.; Bertino, E.; Cavallarin, L.; Giribaldi, M.; Giuliani, F.; Cresi, F.; Coscia, A. The Effect of Holder Pasteurization on Nutrients and Biologically-Active Components in Donor Human Milk: A Review. Nutrients 2016, 8, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, L.; Johnson, G. 33 POSTHARVEST DISEASES OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLES.

- Schneider, E.P.; Dickert, K.J. Health Costs and Benefits of Fungicide Use in Agricultur:. J. Agromedicine 1994, 1, 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.; DeGrandi-Hoffman, G.; Liao, L.-H.; Tadei, R.; Harrison, J.F. The Challenge of Balancing Fungicide Use and Pollinator Health. In Advances in Insect Physiology; 2023; Vol. 64. [Google Scholar]

| Function | Study Design | Treatment | Results | Reference |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Susceptibilities of clinical isolates (n=12) and type strains (n=5) of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to LPO-I⁻-H2O2 combination and different antibiotics were tested. In combination 75 µg LPO, 100 nmol I⁻ and 1000 nmol H2O2 were used. |

The combination exhibited an inhibition on Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans similar to 2 microgram ampicillins. | [5] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Milk samples (n=250) consisting of morning and overnight samples, were tested. LPO in raw milk was activated by addition of 14 mL of freshly made NaSCN (1 mg/mL) solution per liter of milk and in total 10 mL of freshly made 1 mg/ mL H2O2 solution. |

The quality of the all LPOS-activated milk samples was found to be higher than all the control samples. | [6] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro and ex vivo |

In vitro: 14 mL TSB broth, 1 mL inoculum (Listeria innocua, Pseudomonas fluorescens, or Staphylococcus saprophyticus), 1 mL 1% LPO (sterile distilled water). Ex-vivo meat: 3 groups of pork (shoulder) cubes (2x2x2cm) were soaked in distilled water, TSB broth with Listeria innocua, and LPO solution (5 g LPO in 100 ml distilled water). 0.25% and 0.50% LPO solutions were used to make pork ham and pâté ex vivo. |

LPO has significant inhibitory effects on growth of Listeria innocua, Pseudomonas fluorescens and Staphylococcus saprophyticus. Study showed that LPO can be used to elongate shelf life of meat and meat products. | [7] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Specific dosage of LPOS components was not mentioned. Raw camel milk, pasteurized raw camel milk and boiled camel milk each were tested by itself, with addition of exogenous H2O2 or with addition of H2O2 producing lactic acid bacteria. | LPOS activated by H2O2 producing lactic acid bacteria have significantly positive effects on storage of raw camel milk. Weissella confusa 22282 was determined as the best strain of the strains tested in the study to produce H2O2. | [8] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Challenge 20 permanent third molars to replicate caries-affected dentin. Before sealing, five samples were treated with LPO, LF, lysozyme, and hydroxyapatite. The combination contains 0.018 mg LPO, LF, lysozyme, and hydroxyapatite powders. The total viable Streptococcus mutans count was measured before, 24h, 1 month, and 6 months after therapy. | LPO may be combined with LF, lysozyme and hydroxyapatite for treatment of dentinal caries. A significant reduction in Streptococcus mutans was observed 24 hours after treatment by the combination. | [9] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | A whey protein-alginate coating with LPOS was created and tested for its antibacterial properties on chicken thigh meat. The coatings were produced with varying concentrations of LPOS, including LPO, GO, Glu, KSCN, and H2O2. | A whey protein-alginate coating with LPOS has a substantial antibacterial impact, and this study found that the effect increases with LPOS content, with the largest effect at 8% LPOS. A study found that LPOS coating can extend chicken thigh meat shelf life. | [10] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Dangke samples were immersed in solutions of LPOS, lysozyme or LPOS+lysozyme at 30°C for 4 hours. Dangke which was immersed in distilled water was used as a control. LPOS was prepared with 300μL of LPO, 300μL of 0.9mM H2O2 and 300μL of 0.9mM KSCN. | The results showed that there is a significant inhibition of the growth of microbes in LPOS, lysozyme and LPOS+lysozyme immersed dangke samples stored for 8 hours, higher antimicrobial activity was observed in LPOS+lysozyme immersed dangke samples than other samples | [11] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | Effects of alginate coatings with and without LPOS on shelf life of chicken breast fillet were tested. LPOS-containing alginate coatings were produced with 2%, 4% and 6% (v/v) LPOS concentrations. LPOS was made of LPO, GO, Glu, KSCN, KI at ratios of 1.00:0.35:108,70:1.09:2.17 (w/w), respectively. 15.5 mg LPO was used. | The combinations of LPOS and alginate coating exhibited a significant positive effect on increasing the shelf life of the chicken breast fillets under refrigerated conditions. Higher effect was observed at higher LPOS concentrations. | [12] |

| Antibacterial | In vitro | The antibacterial activity of a system containing goat LPO, H2O2, and KSCN was tested on various bacteria by using the disc diffusion method | The system was effective on all tested strains. Inhibition zones were ranging from 22 mm to 26 mm and MIC values for goat milk LPO in the system were ranging from 49 µg/ml to 297 µg/ml | [59] |

| Antibacterial and Antiplaque | Four-replicate crossover study design | A study involving 16 volunteers was conducted to test four different oral hygiene treatments. The treatments were applied in five different sequences. The control group received a mouth rinse with Listerine twice daily. The B treatment involved lozenges containing 10 mg LPO 350 U/mg, 7.5 mg KSCN, and 0.083% H2O2 in a 1:2 H2O2/SCN⁻ ratio, while the C treatment used lozenges with 10 mg LPO 350 U/mg, 7.5 mg KSCN, and 0.040% H2O2 in a 1:2 H2O2/SCN⁻ ratio | The study found that LPOS-containing lozenges can be used in daily oral care for humans due to their anti-plaque regrowth and cariogenic bacteria reduction properties. Treatment B reduced more Streptococcus mutans than treatment C and D, while treatment A showed the most significant antiplaque-regrowth activity. Treatment C showed more reduction on Lactobacilli. | [13] |

| Antibacterial, antiplaque and anti-inflammation | A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled clinical trial study design |

150 adults were divided into 3 groups and treated by tablets in addition to their daily oral hygiene routine for 12 weeks. The first group was treated by high-dosage tablets that contained 60 mg/d bovine LF and 7.8 mg/d bovine LPO, the second group was treated by low-dosage tablets that contained 20 mg/d bovine LF and 2.6 mg/d bovine LPO, the third group was treated by placebo tablets. | After 12 weeks of treatment, the high dosage group had considerably lower gingival index (GI) than the placebo group. Both high and low dosage groups had considerably lower plaque index (PlI) at 12 weeks than baseline. The high dosage group had a considerably lower 12-week OHIP score. Results demonstrated that bovine LPO and bovine LF pills may improve oral health in healthy persons. |

[14] |

| Antibacterial and immunomodulatory | In vitro and in vivo | Camel colostrum LPO and camel colostrum LF were tested against 14 multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from patients with nosocomial pneumonia. The study used the agar well diffusion method to examine their inhibitory effect. In vivo, 5-6 weeks old mice were divided into five groups and exposed to experimental treatments. The mice were injected with different doses of PBS, imipenem, LF, LPO, and LPO, and exposed to different treatments. The results showed promising results in treating nosocomial pneumonia. | Studies have demonstrated that camel colostrum LPO and camel colostrum LF have significant antibacterial activity against Acinetobacter baumannii isolates. LPO showed higher activity than LF at the same concentrations. In vivo, a combination of imipenem, LPO, LF, and a crude combination significantly reduced bacteria in lung and blood cultures. LPO and LF also synergistically affected proinflammatory cytokines in treated mice | [15] |

| Antiviral | In vitro | The study tested influenza virus susceptibility to LPO products and substrate specificity in a cell-free system. Madin-Darby canine kidney cells were used to evaluate viral inactivation. The system used for virus inactivation included LPO, SCN⁻/I⁻, glucose, and glucose oxidase | All tested influenza strains were inactivated by LPO. LPO did not prefer substrates to inactivate H1N1 and H1N2 viruses. H3N2 strains were inactivated better using iodide than thiocyanate as the LPO substrate. |

[16] |

| Antiviral | In vitro | Milk proteins LF, angiogenin-1, α-lactalbumin, β-lactoglobulin, LPO, casein, lactogenin, and glycolactin inhibited HIV-1 RT, α-glucosidase, β-glucosidase, and β-glucuronidase, with succinylation effect examined using ELISA | LPO, both unmodified and succinylated, showed significant inhibitory activity on HIV-1 RT. Succinylated LPO showed small inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase and β-glucosidase. Unmodified proteins, except α-lactalbumin and casein, showed significant inhibition. Succinylation increased inhibitory activity of human LF, glycolactin β-lactoglobulin, and α-lactalbumin and casein. | [17] |

| Antiviral | The study is an evaluation of datas from different sources as a completion | A compilation that includes population, vaccination ratio, infection ratio, and rate of deaths caused by COVID-19 of some countries was prepared. | The study found that Asian countries with high iodine-containing diets, like Japan, South Korea, and India, had significantly lower COVID-19 death rates compared to western countries, possibly due to differences in iodine intake | [18] |

| Antiviral | In vitro | The antiviral activities of human LPO, bovine LPO, and camel LPO against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1) were evaluated using cytotoxic effect assay and plaque assay. The viruses were treated with LPO at different concentrations and infected with vero cells. | At concentrations of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, and 0.5 mg/ml, bovine milk LPO had 24, 38, 62, 80, 100% anti-HSV-1 activity, human colostrum had 10, 16, 30, 44, 66%, and camel milk had 12, 18, 34, 50, 70%. | [63] |

| Antiviral | In vitro | The study investigated the protective and neutralizing effects of bLPO, cLPO, and hLPO on Hepatitis C virus (HVC) genotype 4. HepG2 cells were pre-incubated with purified LPO samples and infected with 2% HCV infected serum. The effects of bLPO, cLPO, and hLPO on HCV replication were also examined. LF was used as a control due to its strong activity against HCV G4. | The study revealed that LPO, including bLPO, cLPO, and hLPO, did not protect cells from HCV entry, but they effectively neutralized HCV particles and inhibited entry into HepG2 cells. | [62] |

| Antifungal | In vitro | LPO-containing systems were investigated for candidacidal action against Candida albicans ATCC strains 18804, 10231, and 11006, comparing CFU and cell viability loss. The study also explored how component concentrations affected candidacidal action. | The system of bovine LPO, GO, glucose, and KSCN showed varying candidacidal activity on different strains. The system's activity increased with preincubation time, with the highest activity on Candida albicans ATCC strain 11006. | [19] |

| Antifungal | In vitro | The antifungal activity of LPOS was tested on various fungi, using a mixture of H2O2, KSCN, and goat milk LPO, with concentrations ranging from 30 to 1 mg/mL | Candida albicans and Pythium sp. were resistant to the goat milk LPO-H2O2-KSCN system. MIC values of goat LPO in the system against the other strains tested were determined in the study. | [59] |

| Antifungal | In vitro | The anti-candida activities of LF and LPOS were tested using bovine LF, bovine LPO, and Candida albicans. OSCN⁻ solution was produced by using the enzyme system that consisted of 0.16 mg/ml LPO with 7.5 mM NaSCN and 3.75 mM H2O2 in a buffer | LF and LPOS exhibit significant anti-candida activity on Candida albicans, impacting growth morphology, metabolic activity, and adhesive hyphal form, affecting cellular metabolism | [61] |

| Antifungal | In vitro | Postharvest mangoes were treated by chitosan coatings with or without LPOS. Two LPOS solutions were used, one of them containing iodine (LPOSI) while the other one did not. Antifungal activity was tested by using strains of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Phomopsis sp. RP257, Pestalotiopsis sp. and Lasiodiplodia Theobromae ngr 05 A | According to results, there is a synergistic effect of chitosan and LPOS. Inhibitory effect of the coatings was improved by LPOS in all cases. Some strains showed a resistance to chitosan while they were more sensitive to LPOS. | [60] |

| Antifungal | In vitro and in vivo | A coating made of chitosan solutions and LPOS was produced, tested in vitro and in vivo against fungal strains, with a 5% concentration in the film-forming solution | In vitro results showed that chitosan solutions at 1% and 1.5% without LPOS completely inhibited Pestalotiopsis sp. growth, while low inhibition was observed at 0.5%. In vivo results showed increased inhibition, with Phomopsis sp. RP257 less sensitive. LPOS with or without iodide increased inhibition at 0.5% chitosan. | [20] |

| Antioxidant and Therapeutic | In vivo | The study involved 40 adult male albino rats divided into four groups, each with 10 rats, and exposed to experimental treatments to investigate the effects of LPO on aflatoxin B1-induced nephrotoxicity | Measurements indicated that LPO treatment after AFB1 intoxication in group 4 approached all of the values to the values of group 1 which consist of healthy individuals. LPO treatment ameliorated the deteriorations caused by AFB1 | [65] |

| Antitumor and Anti-inflammation | In vivo | Researchers deleted the LPO gene from mice | LPO gene deletion in mice leads to higher rates of diseases like cardiomyopathy, carditis, arteriosclerosis, airway inflammation, glomerulonephritis, digestive system inflammation, and brain pathology. Tumors are also observed in 7 out of 19 one-year-old mice, some of which are overweight or obese | [64] |

| Diagnosis | In vitro and in silico | LPO activity in cow milk was measured to determine mastitis in dairy cows | LPO activity level can be used as a parameter to determine mammary gland health of cows due to LPO activity increases when mastitis occurs in cows. LPO activity reflects the mammary gland health of cows | [23] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).