Submitted:

05 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

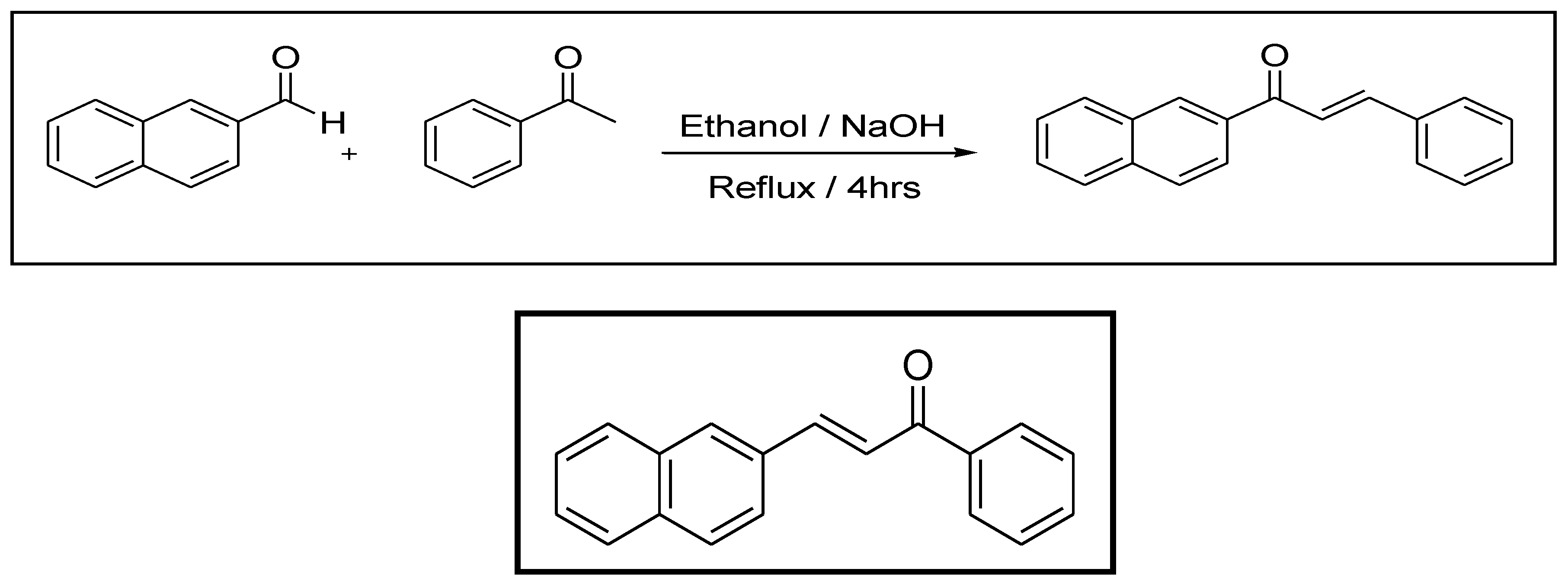

2.1.1. Design and Synthesis

2.2. Instrumentation

2.2.1. UV-Vis Spectroscopy

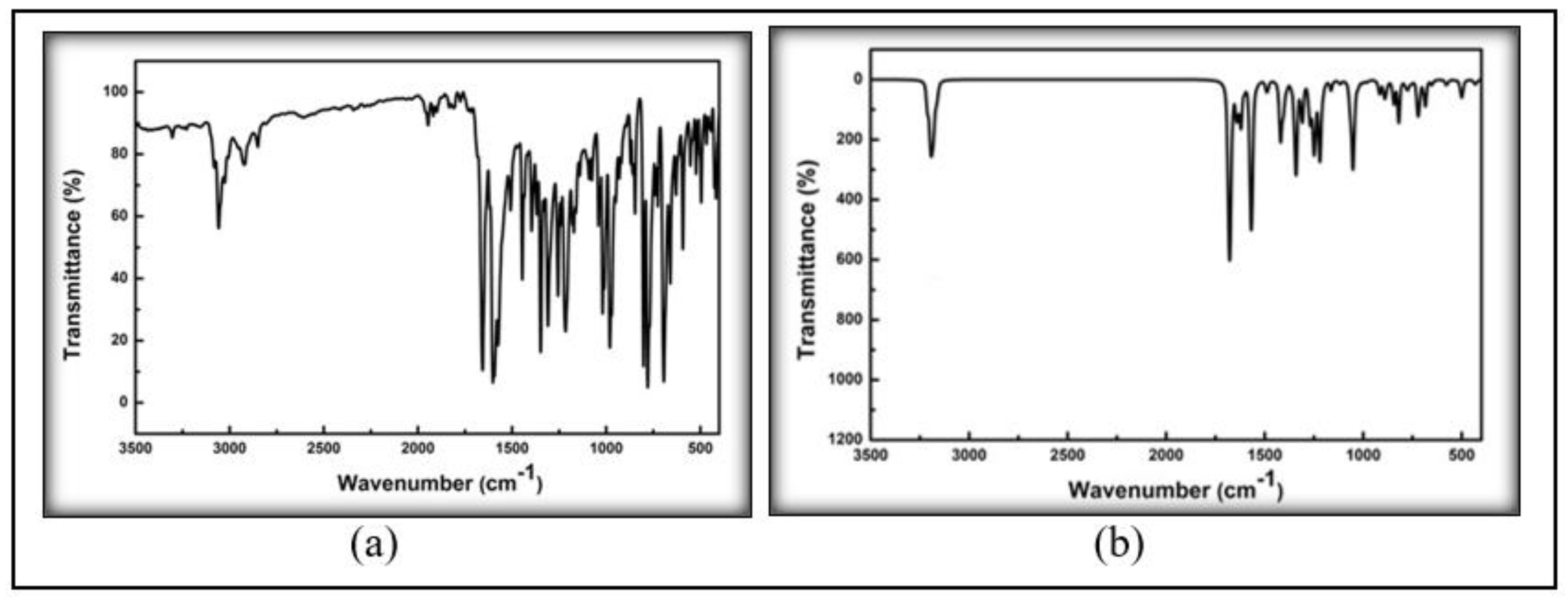

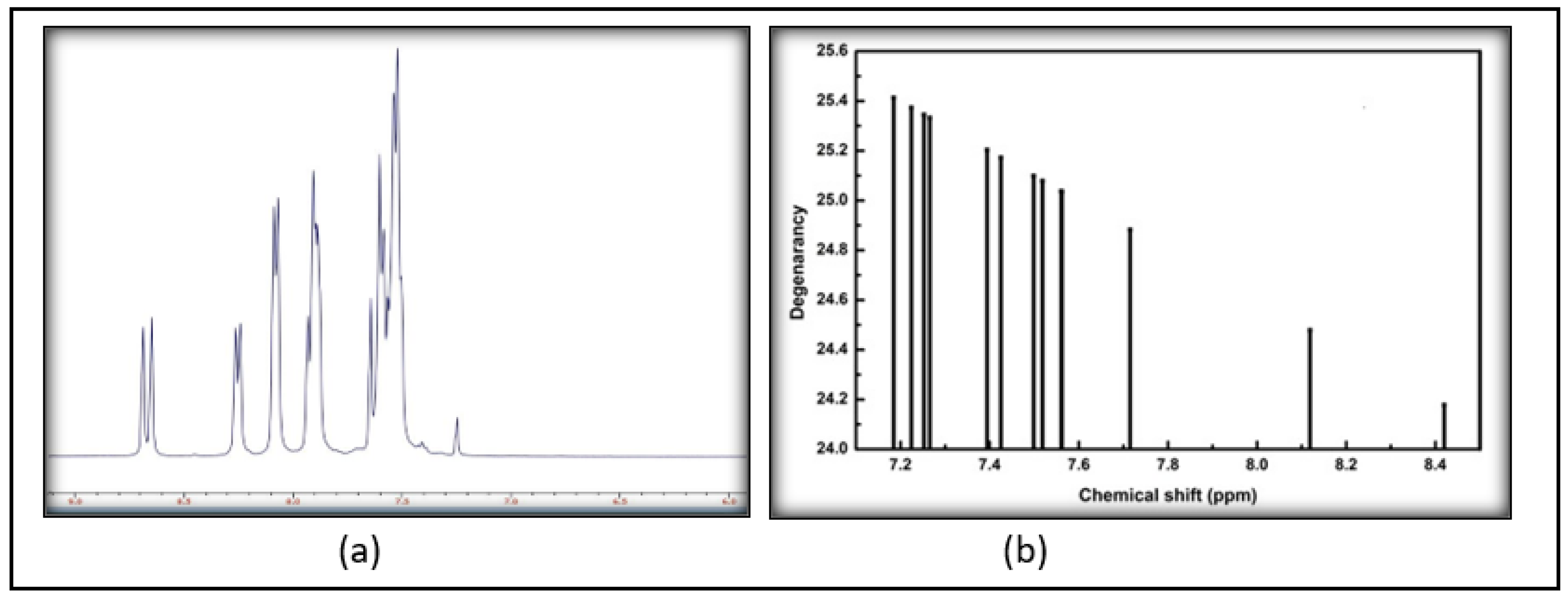

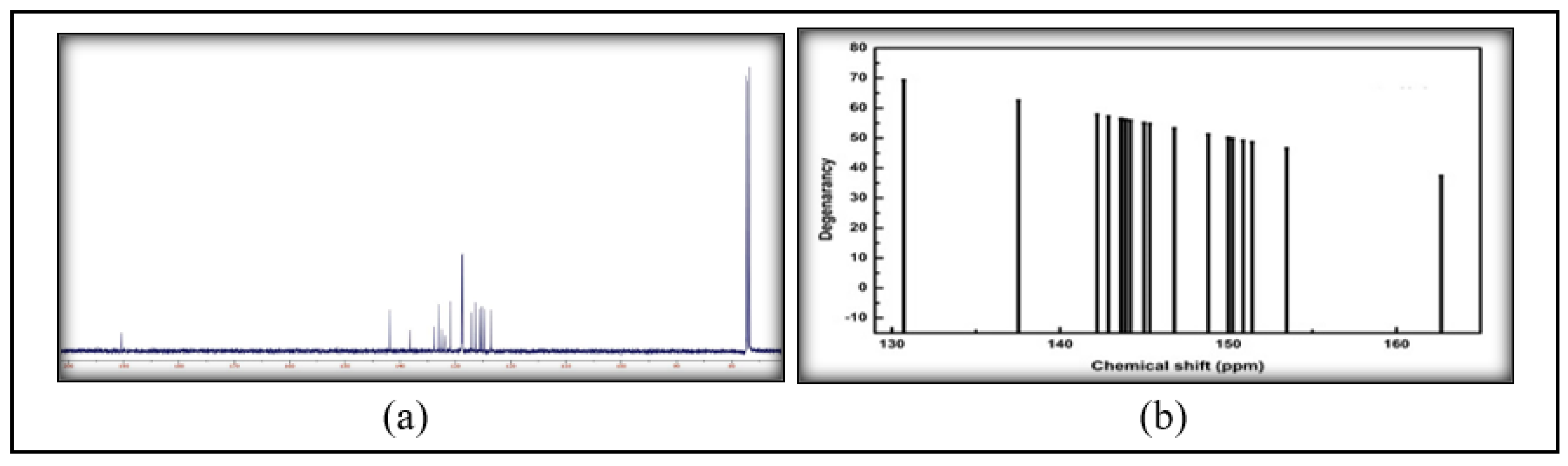

2.2.2. FT-IR and NMR

2.2.3. Photoluminescence Spectroscopy and Fluorescence Quantum Yield (Φf)

2.2.4. Nonlinear Optical Measurements

2.2.5. Computational Methods

2.2.6. Electrochemical Characterization

2.3. Biological Evaluation

2.3.1. Structure Preprocessing, Validation and Molecular Docking

2.3.2. Molecular Dynamic Simulation and Trajectory Analysis

2.3.3. Free Energy and Decomposition

2.3.4. Free Energy and Decomposition

2.3.5. Cytotoxicity Studies

2.3.6. Apoptosis by Flow Cytometer

3. Results and Discussions

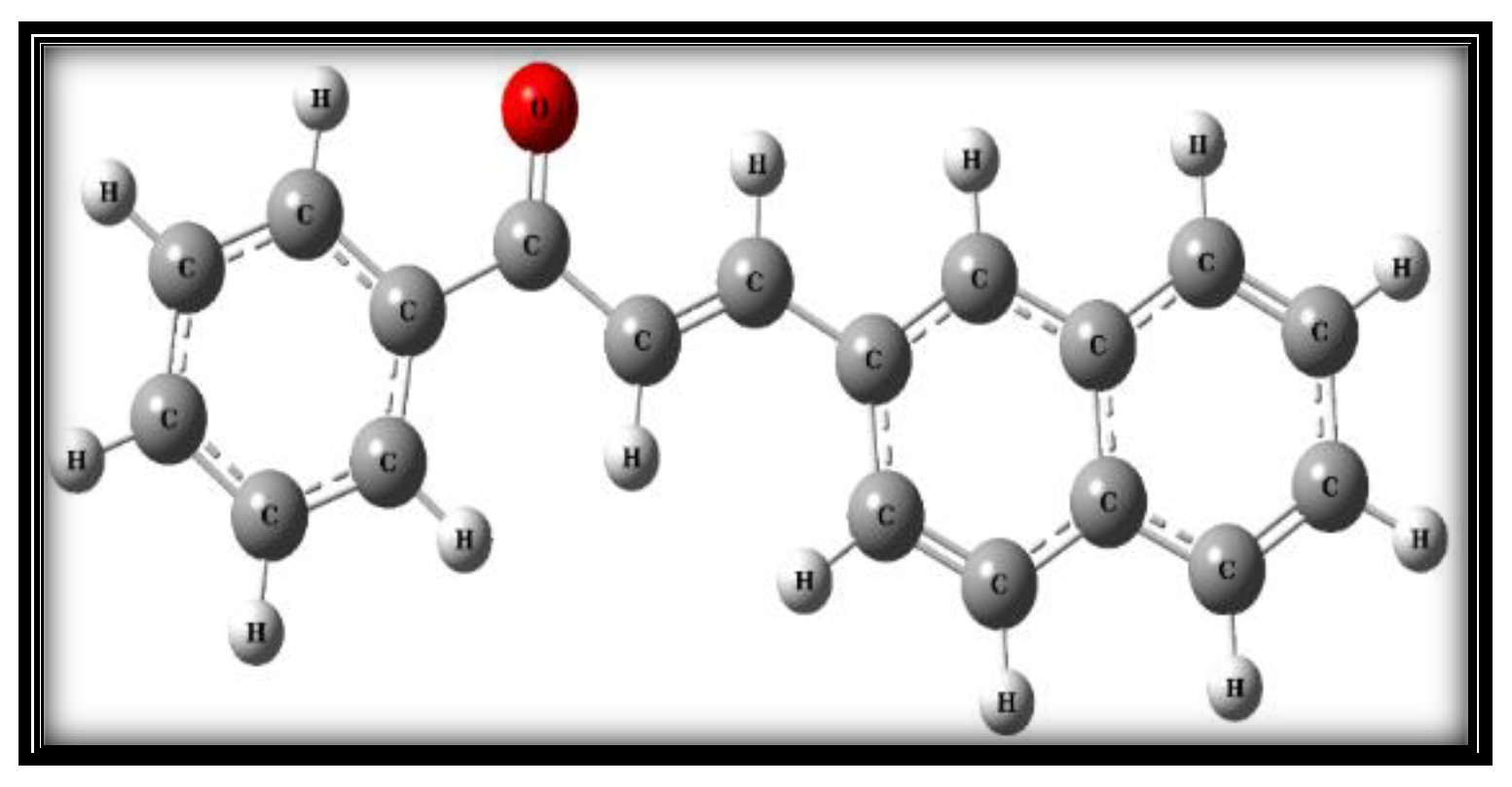

3.1. Structural Analysis

3.2. Spectroscopic Analysis

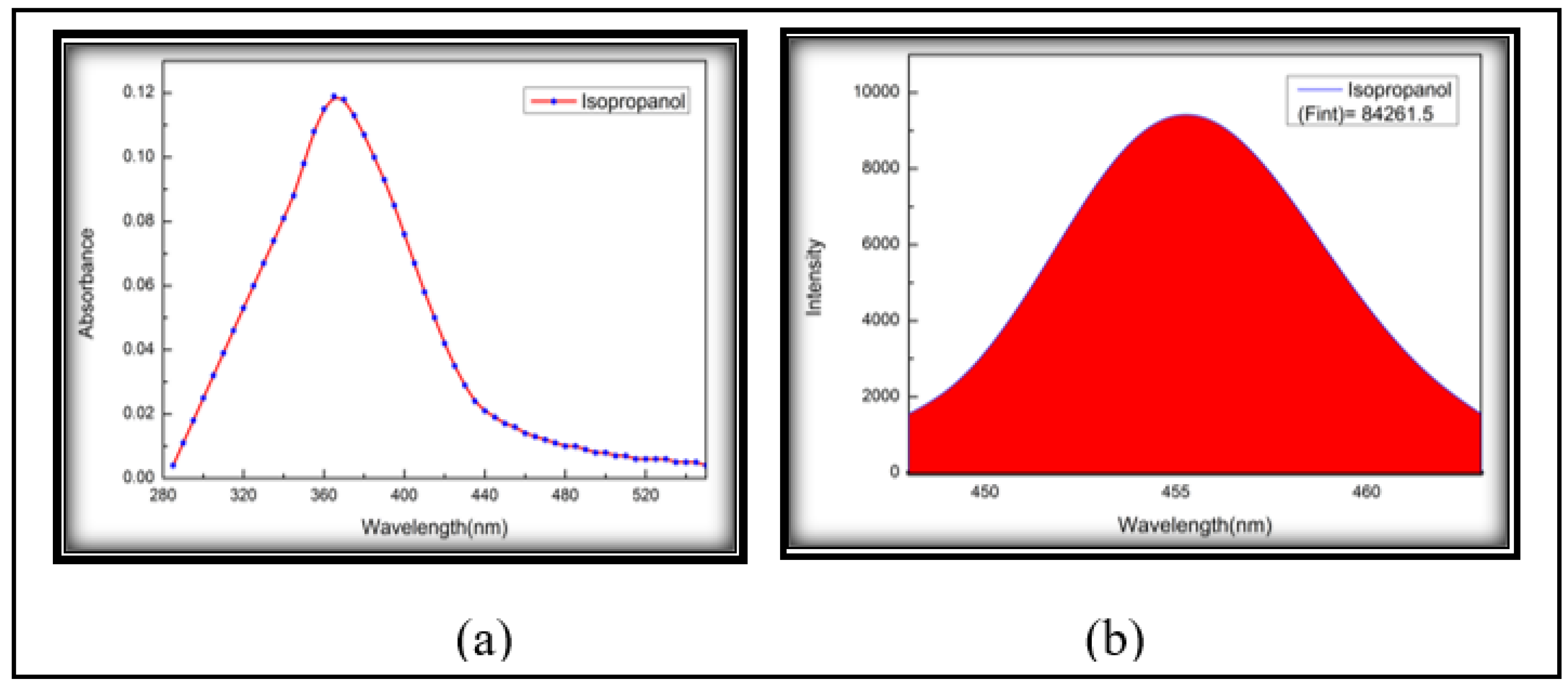

3.2.1. Photophysical Properties

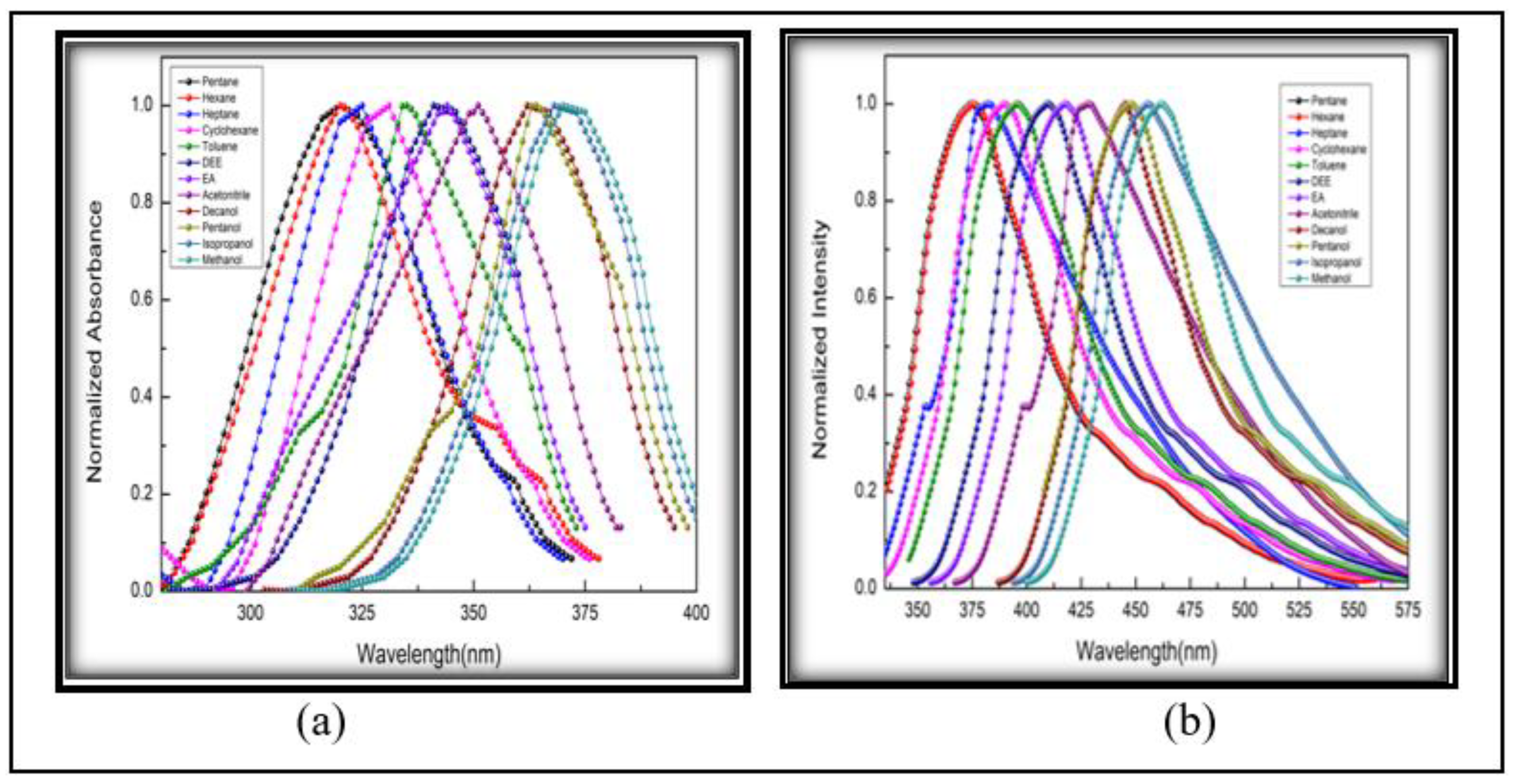

3.2.2. Solvatochromic Analysis

|

Radius ‘r’ (Ao) |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

D |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.89 | 3.51 | 5.72 | 10.74 | 12.88 | 1.19 | 2.47 | 14.41 | 12.91 | 18.07 | 13.08 | 2.14 | 1.29 | 1.20 | 00 |

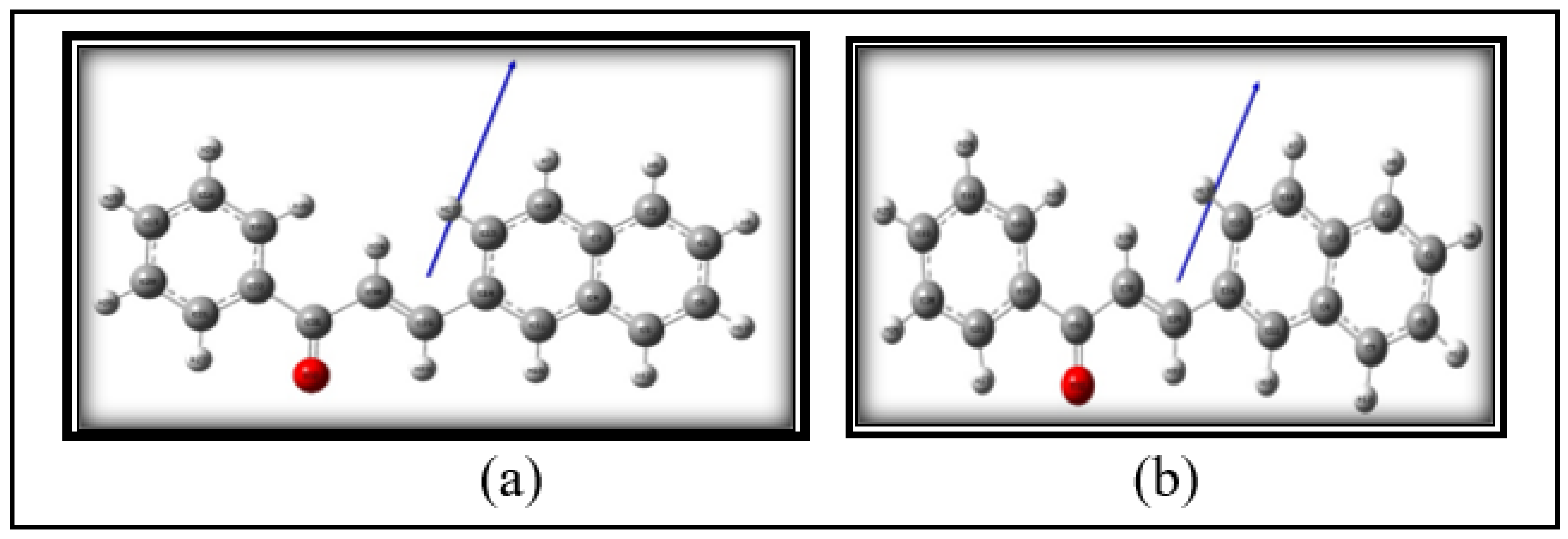

3.2.3. Computational Analysis

3.3. Fluorescence Quantum Yield (Photonic Efficiency)

3.4. Nonlinear Optical Studies

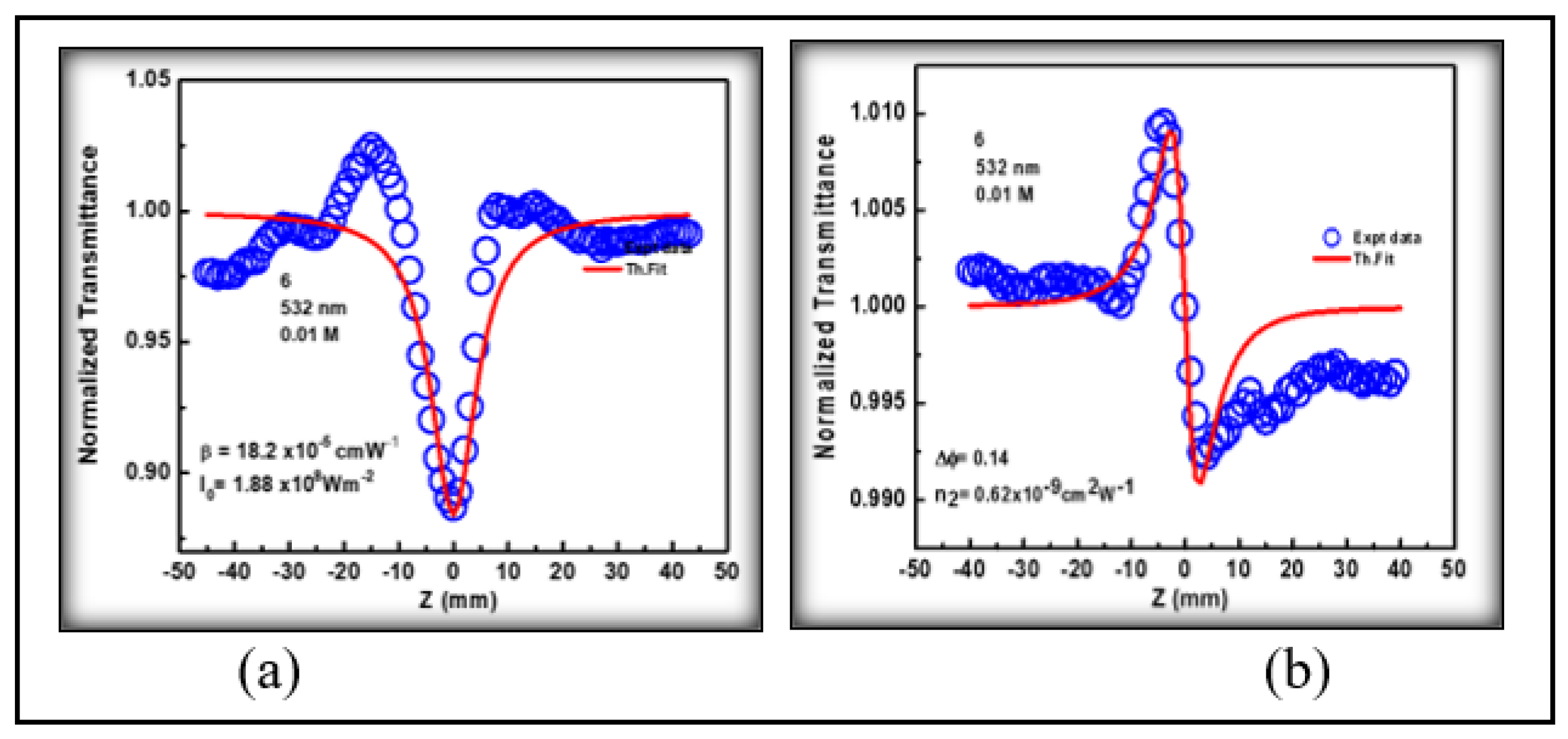

3.4.1. Third Order Nonlinear Optical Properties

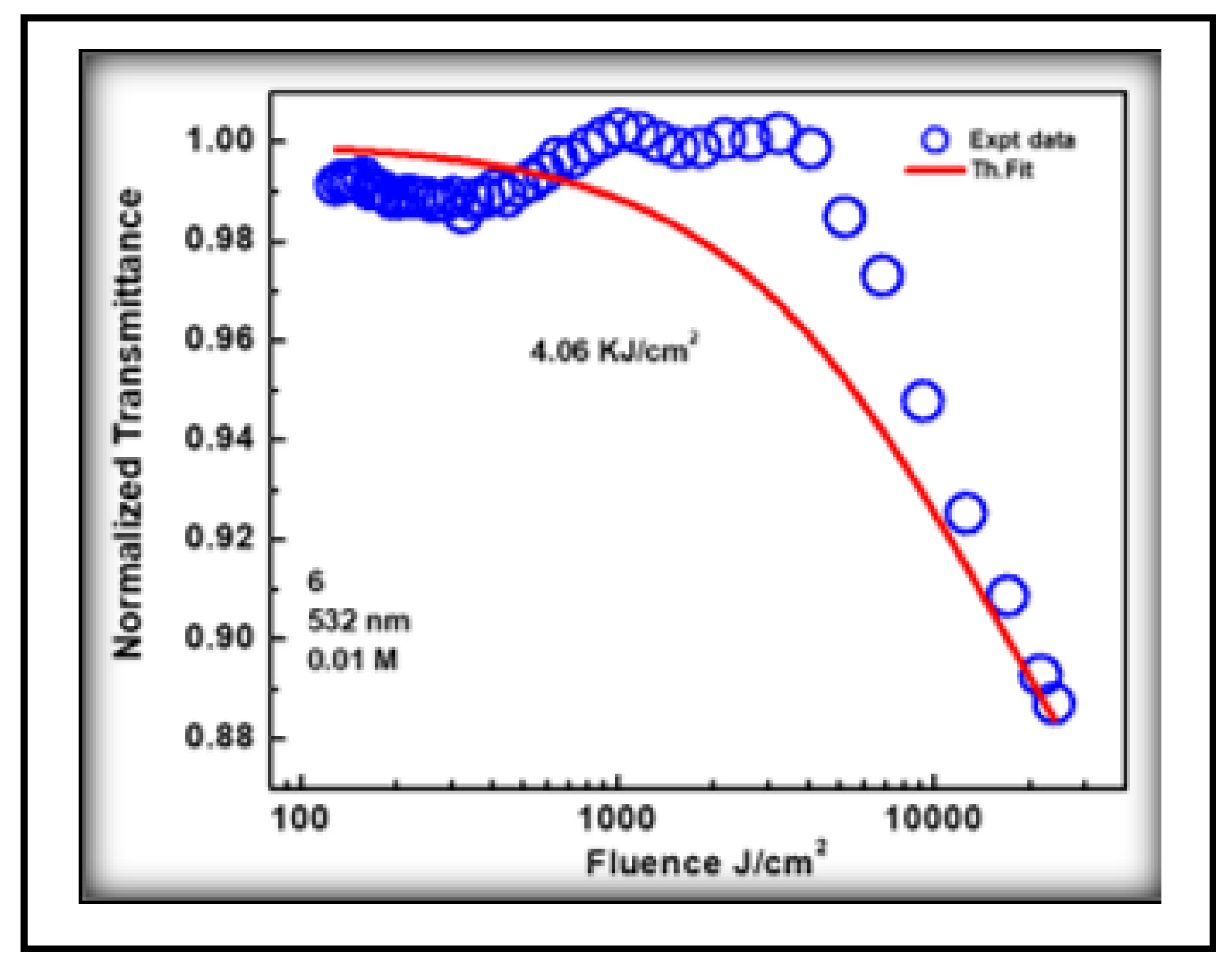

3.4.2. Optical Limiting

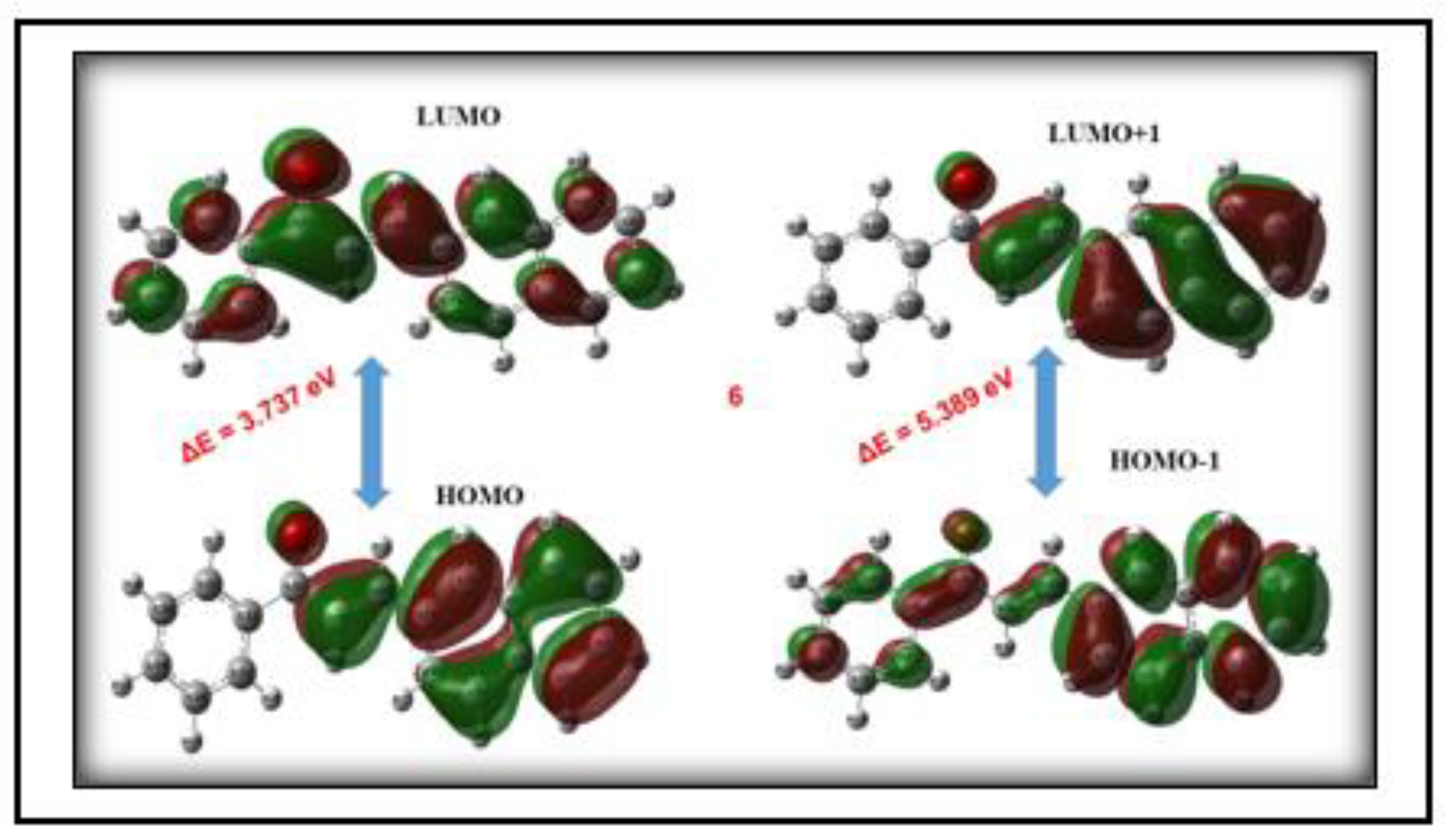

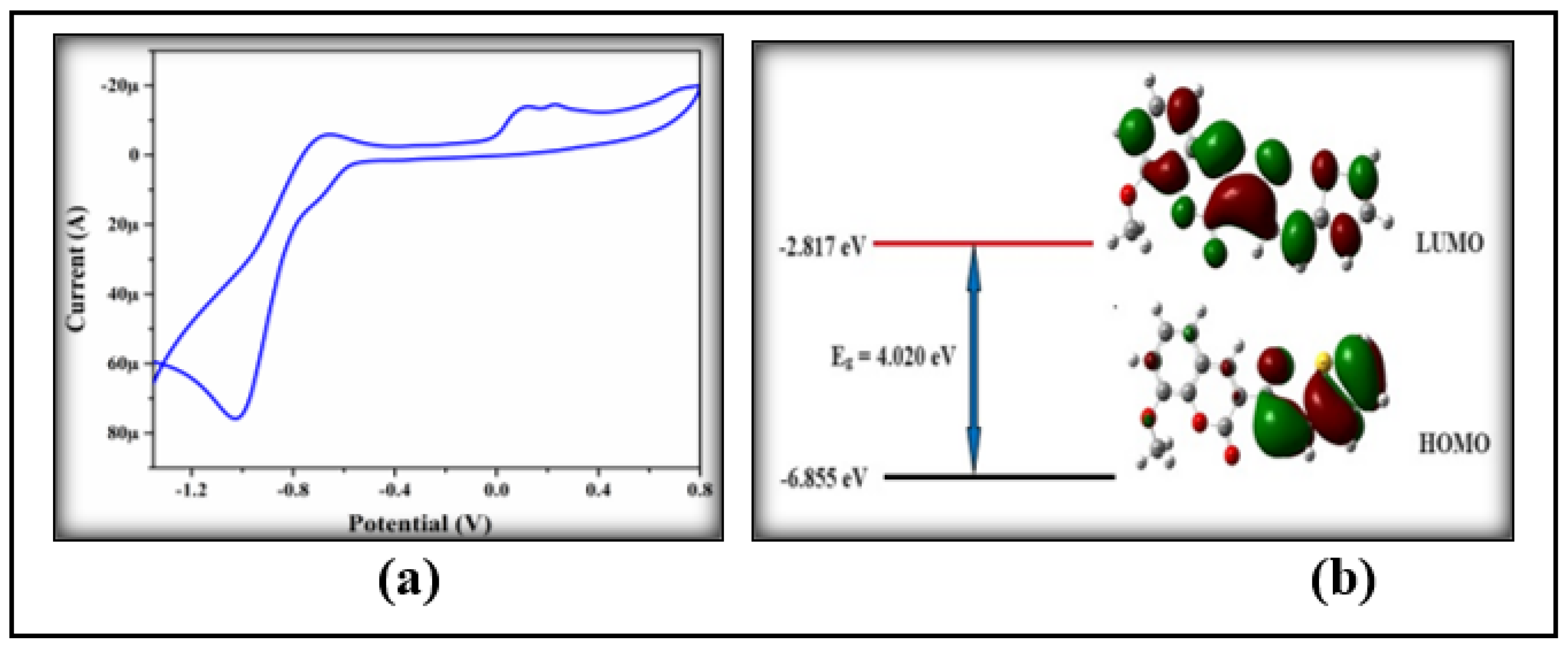

3.4.3. HOMO-LUMO Analysis

3.4.4. The Global Chemical Reactivity Descriptors (GCRD)

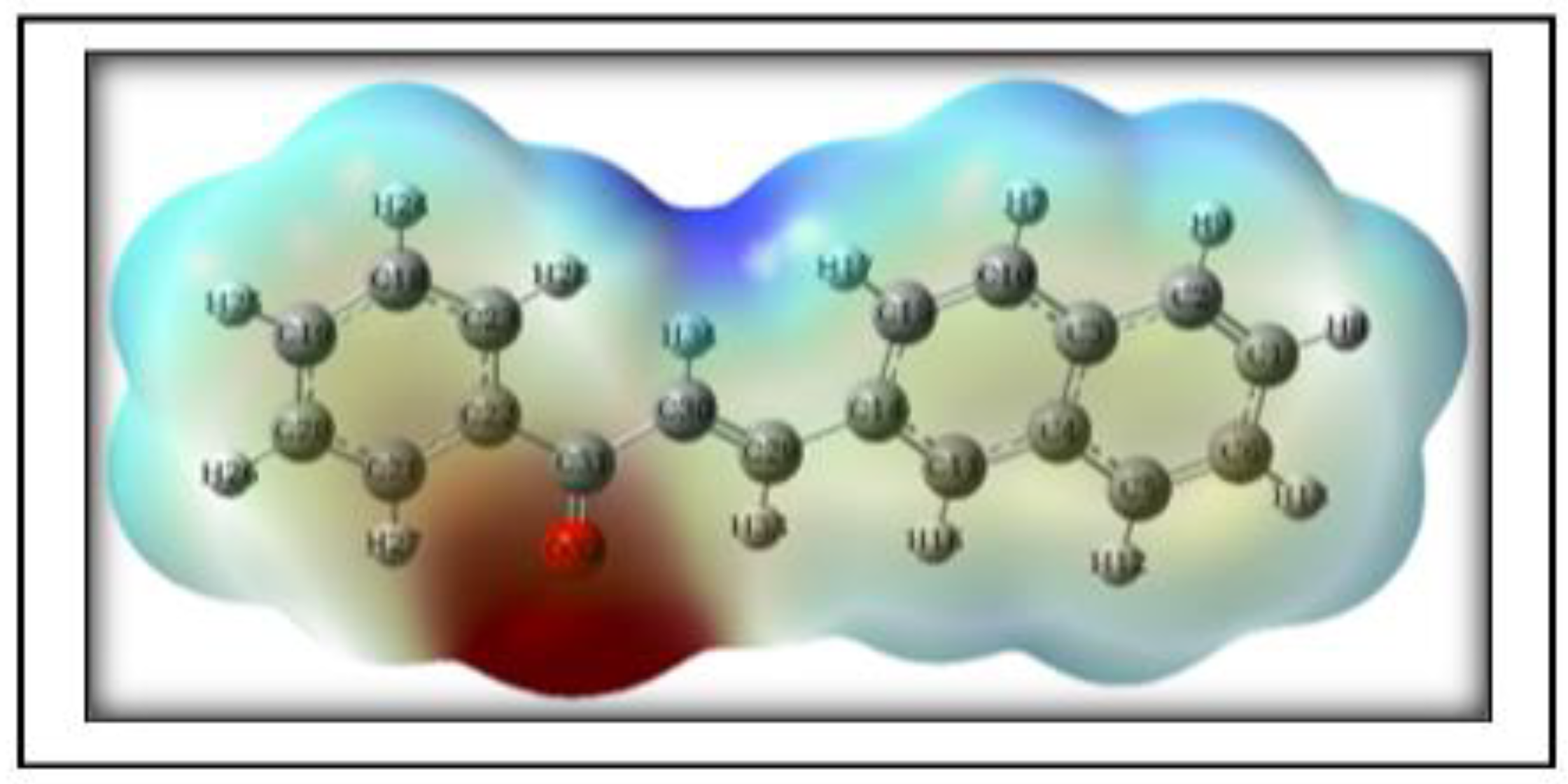

3.4.5. Molecular Electrostatic Potential (MEP)

3.5. Electrochemical Property

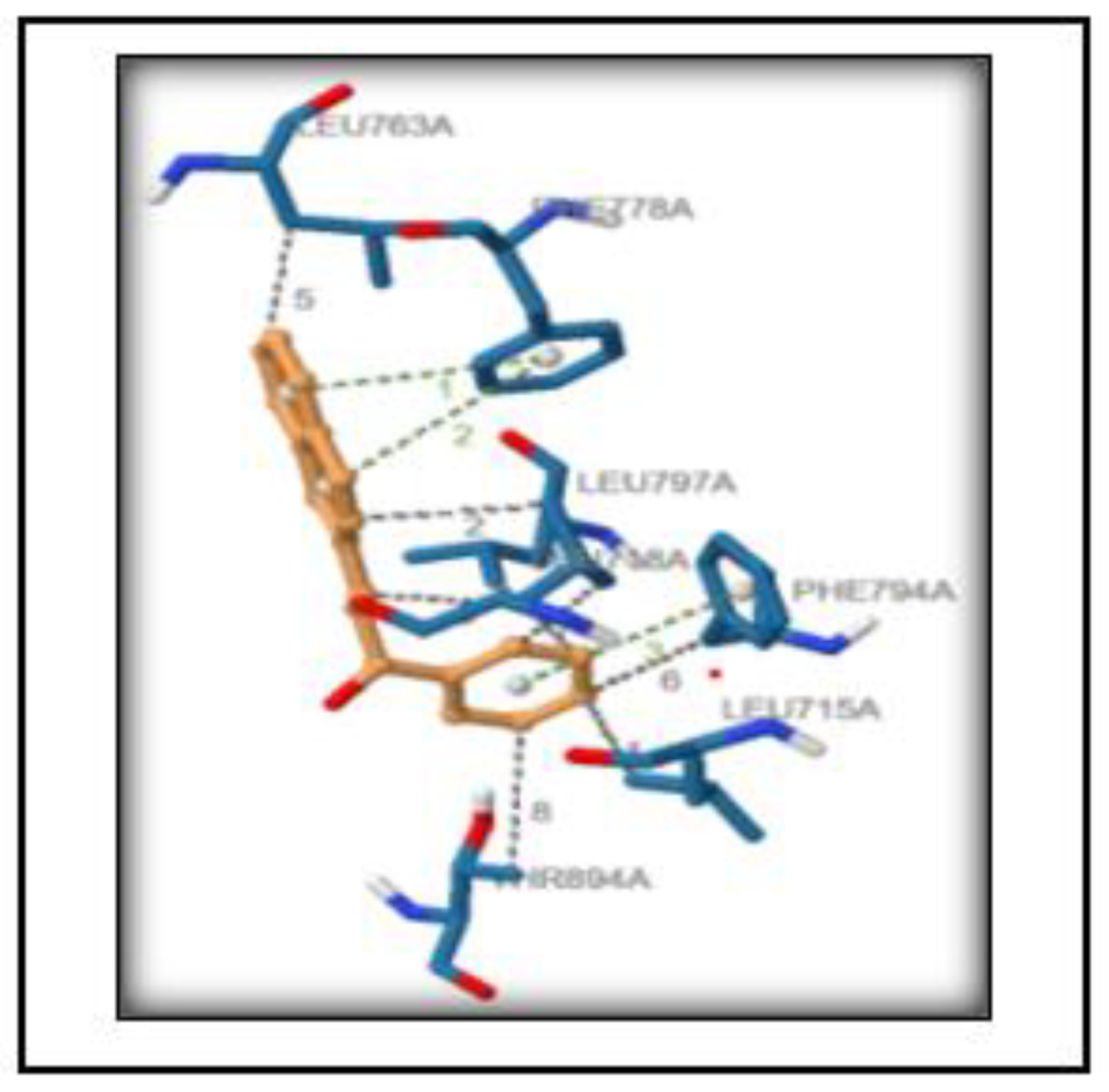

3.6. Structure Preprocessing, Validation and Molecular Docking

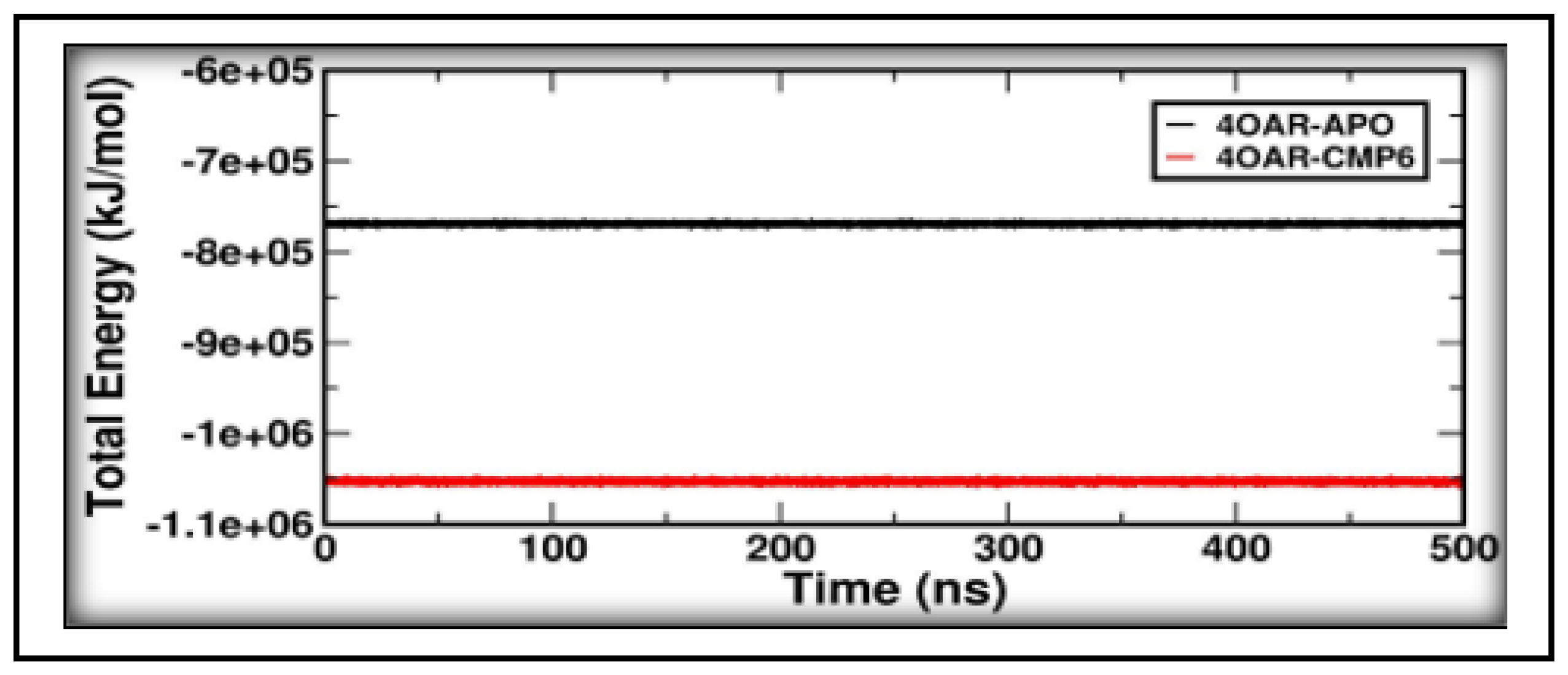

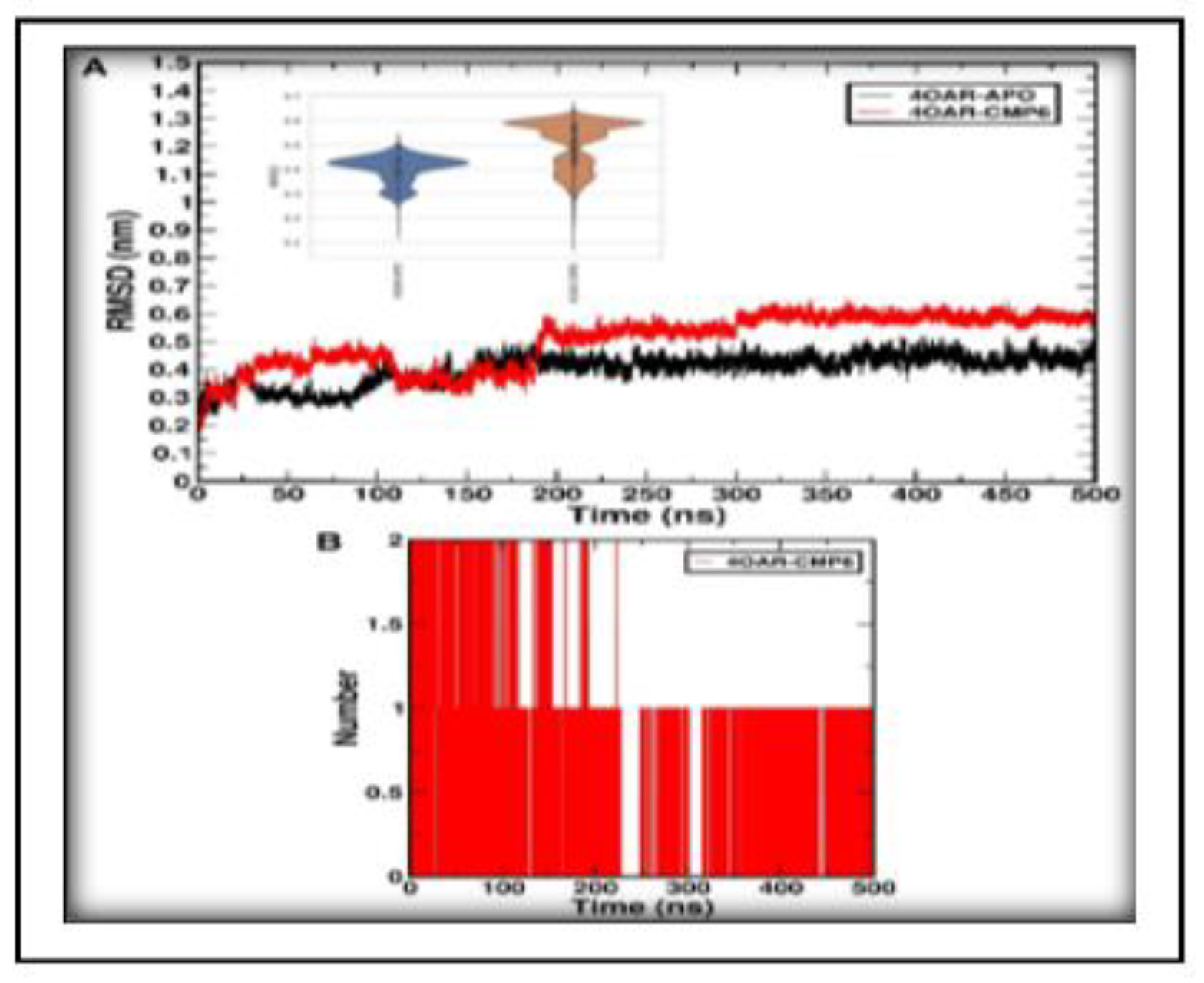

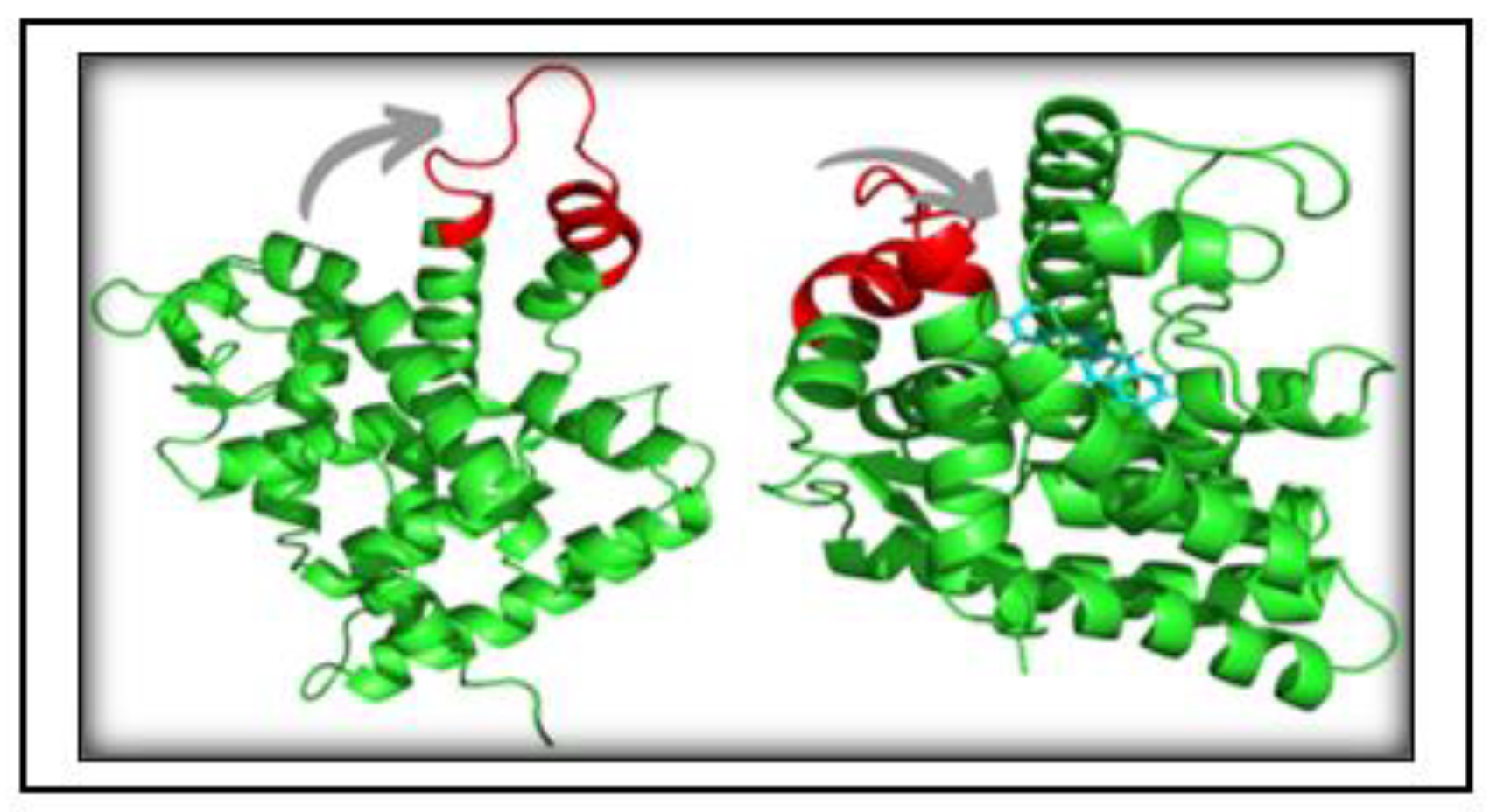

3.7. Simulation trajectory analysis

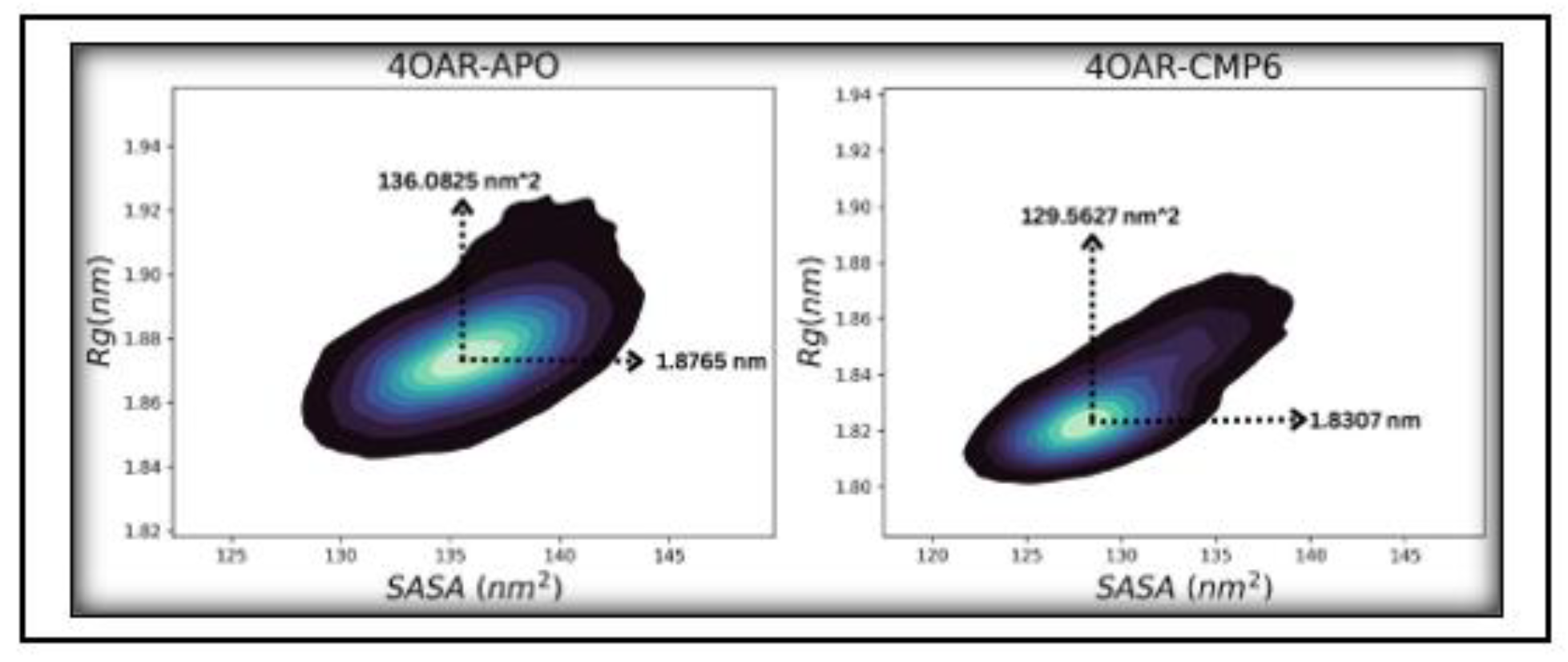

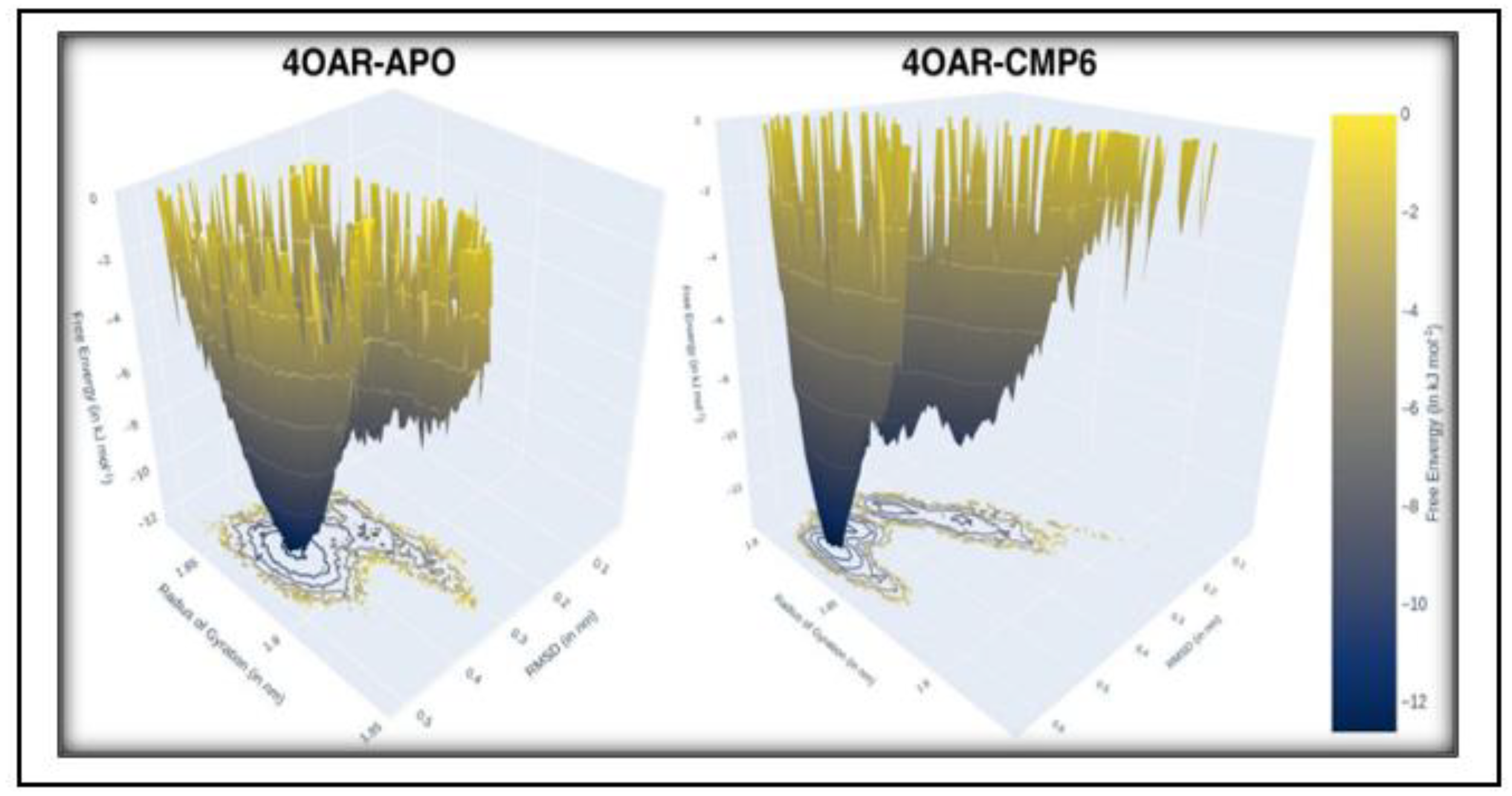

3.8. Conformational Minima and Total System Energy

3.9. Conformational Minima and Total System Energy

3.9. Binding Free Energy and Decomposition

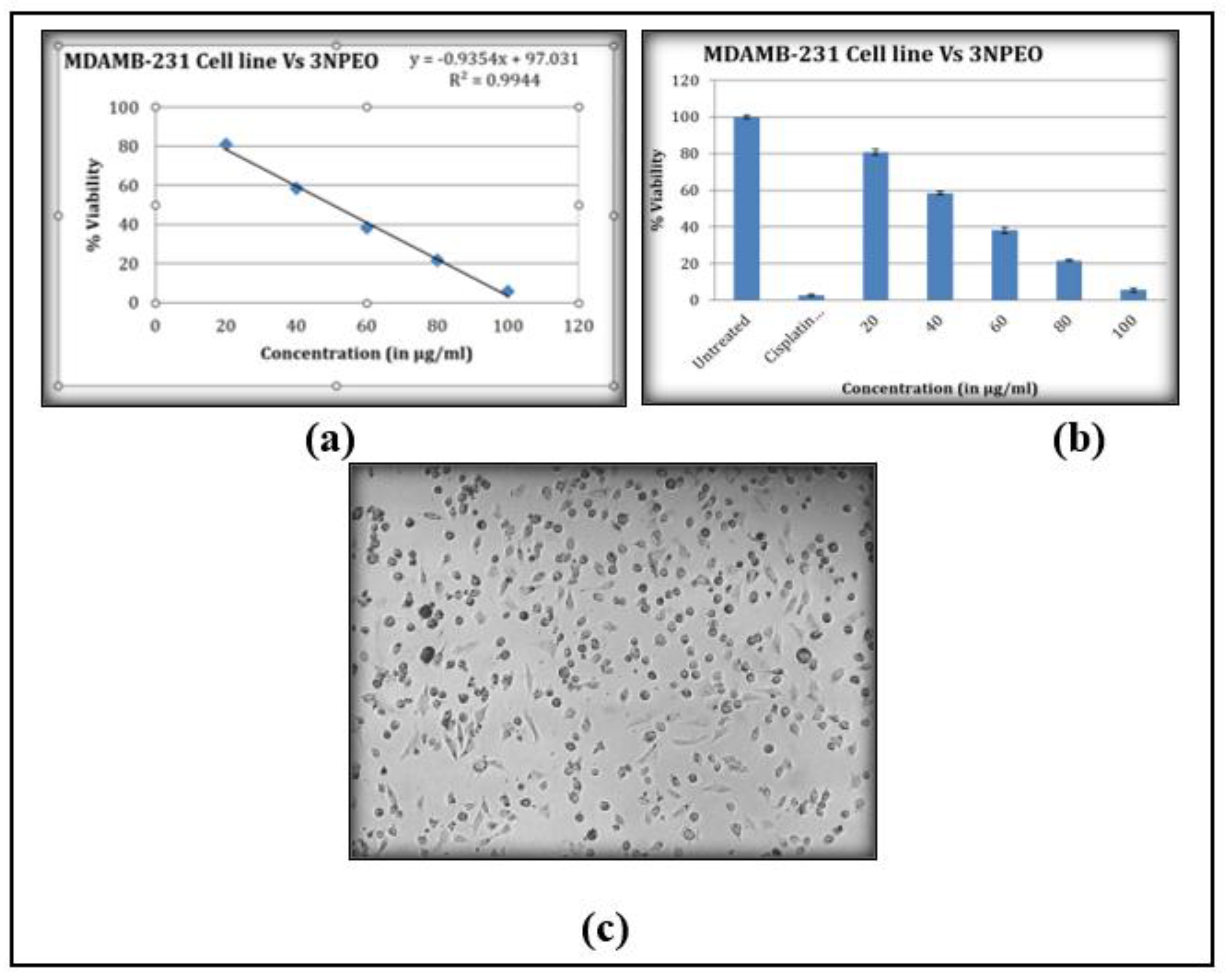

3.10. Cytotoxicity Studies

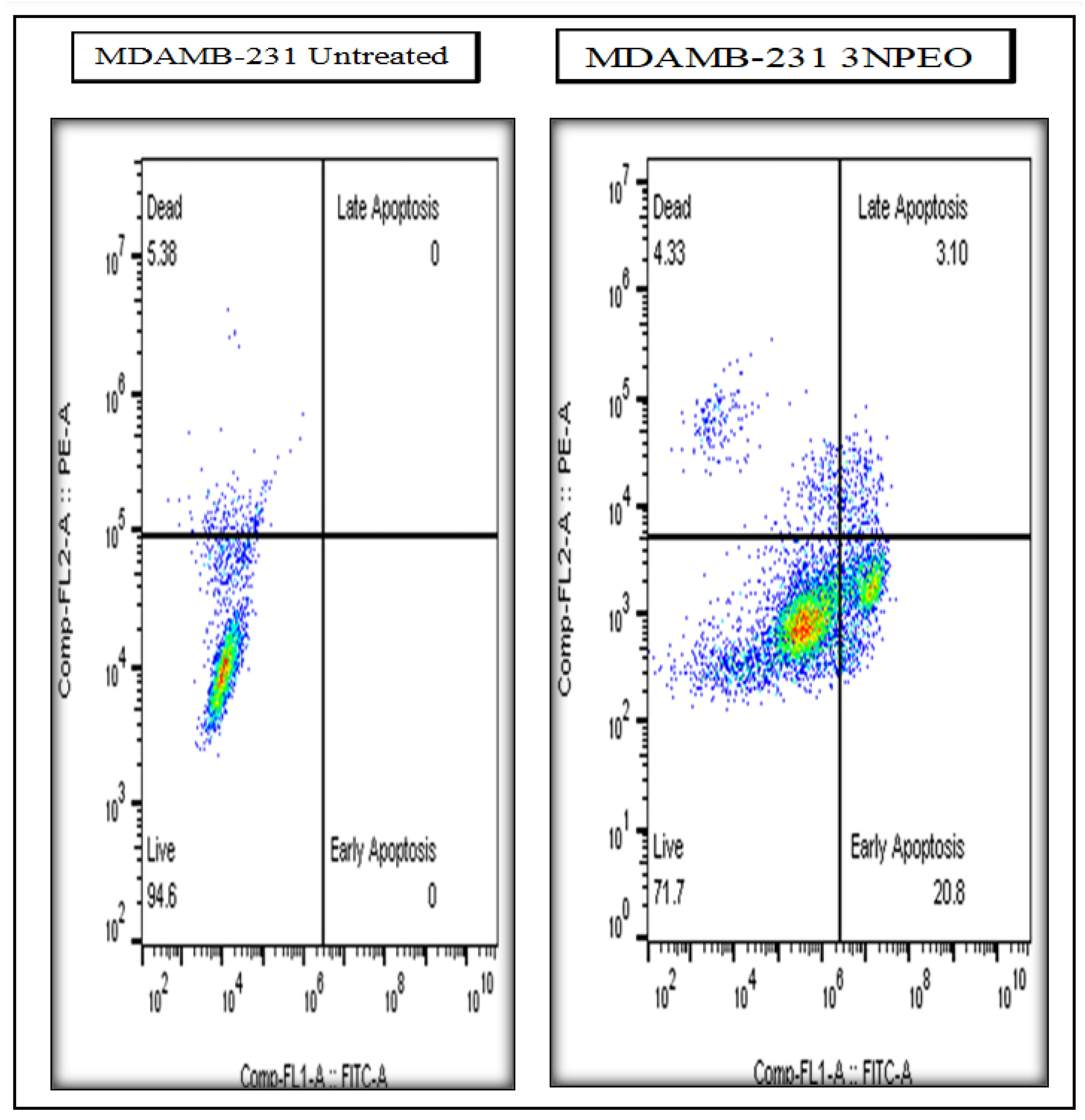

3.11. Detection of Early and Late Apoptosis

4. Conclusions

Associated Content

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- D.N. Dhar, The Chemistry of Chalcones and Related Compounds, John Wiley & Sons, 1981.

- R. G. M da Costa, R de Queiroz Garcia, R. M. d. R. Fiuza, L. Maqueira, A. Pazini, De Boni, L.; Limberger, J. Synthesis, photophysical properties and aggregation-induced enhanced emission of bischalcone-benzothiadiazole and chalcone-benzothiadiazole hybrids. J. Lumin. 2021, 239, 118367. [CrossRef]

- R. Irfan, S. Mousavi, M. Alazmi, R. S. Z. Saleem, A comprehensive review of aminochalcones. Molecules, 2020, 25, 5381.

- C. Zhuang, W. Zhang, C. Sheng, W. Zhang, C. Xing, Z. Miao, Chalcone: a privileged structure in medicinal chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 7762−7810. [CrossRef]

- M.K.M. Ali, A.O Elzupir, M.A. Ibrahem, I.I. Suliman, A. Modwi, Hajo Idriss, K.H. Ibnaouf, Characterization of optical and morphological properties of chalcone thin films for optoelectronics applications. Optik 2017, 145, 529−533. [CrossRef]

- Vinay S. Sharma, Anuj S. Sharma, Nikhil K. Agarwal, Priyanka A. Shah and Pranav S. Shrivastav, Self-assembled blue-light emitting materials for their liquid crystalline and OLED applications: from a simple molecular design to supramolecular materials. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2020, 5, 1691−1705. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Fayed, A novel chalcone-analogue as an optical sensor based on ground and excited states intramolecular charge transfer: A combined experimental and theoretical study. Chem. Phys. 2006, 324, 631−638. [CrossRef]

- Jean M.F. Custodio, Fernando Gotardo, Wesley F. Vaz, Giulio D.C. D’Oliveira, Leonardo R. de Almeida, Ruben D. Fonseca, Leandro H.Z. Cocca, Caridad N. Perez, Allen G. Oliver, Leonardo de Boni, Hamilton B. Napolitano, Benzenesulfonyl incorporated chalcones: Synthesis, structural and optical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1208, 127845. [CrossRef]

- Devaraj Anandkumar, Shanmugam Ganesan, Perumal Rajakumar and Pichai Maruthamuthu, Synthesis, photophysical and electrochemical properties and DSSC applications of triphenylamine chalcone dendrimers via click chemistry. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 11238−11249. [CrossRef]

- Ainizatul Husna Anizaim, Dian Alwani Zainuri, Muhamad Fikri Zaini, Ibrahim Abdul Razak, Hazri Bakhtiar, Suhana Arshad, Comparative Analyses of New Donor-π-Acceptor Ferrocenyl-Chalcones Containing Fluoro and Methoxy-Fluoro Acceptor Units as Synthesized Dyes for Organic Solar Cell Material. PLoS One 2020, 15 (11), No. e0241113.11. [CrossRef]

- Haichuang Lan, Tao Guo, Feijun Dan, Yujie Li, Qian Tang, Ratiometric Fluorescence Chemodosimeter for Hydrazine in Aqueous Solution and Gas Phase Based on Quinoline-Malononitrile. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2022, 271, 120892. [CrossRef]

- Sneha Kagatikar, Dhanya Sunil, Dhananjaya Kekuda, M.N. Satyanarayana, Suresh.D. Kulkarni, Y.N. Sudhakar, Anoop Kishore Vatti, Aditya Sadhanala, Pyrene- Based Chalcones as Functional Materials for Organic Electronics Application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 293, No. 126839. [CrossRef]

- René Maltais, Jenny Roy, Donald Poirier, Turning a Quinoline-Based Steroidal Anticancer Agent into Fluorescent Dye for Its Tracking by Cell Imaging. ACS. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 12 (5), 822−826. [CrossRef]

- C.H. Praveen Kumar, Manjunatha S. Katagi, B.P. Nandeshwarappa, Novel Synthesis of Quinoline Chalcone Derivatives - Design, Synthesis, Characterization and Antimicrobial Activity. Chem. Data Collect. 2022, 42, No. 100955. [CrossRef]

- Shivangi Sharma and Shivendra Singh, Synthetic Routes to Quinoline-Based Derivatives Having Potential Anti-Bacterial AndAnti-Fungal Properties. Curr. Org. Chem. 2022, 26 (15), 1453−1469. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed M. Kaddah, Alaa R. I. Morsy, Abdelgawad A. Fahmi, Mustafa M. Kamel, Mounir M. Elsafty, Sameh A. Rizk & Sayed K. Ramadan, Synthesis and Biological Activity on IBD Virus of Diverse Heterocyclic Systems Derived from 2-Cyano-N-((2-Oxo-1,2-Dihydroquinolin-3-Yl)Methylene)-Acetohydrazide. Synth. Commun. 2021, 51 (22), 3366−3378.

- Ibrahim Ali M Radini, Tarek M Y Elsheikh3, Emad M El-Telbani, Rizk E Khidre, New Potential Antimalarial Agents: Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Some Novel Quinoline Derivatives as Antimalarial Agents. Molecules 2016, 21 (7), 909. [CrossRef]

- Jhesua Valencia, Vivian Rubio, Gloria Puerto, Luisa Vasquez, Anthony Bernal, José R. Mora, Sebastian A. Cuesta, José Luis Paz, Braulio Insuasty, Rodrigo Abonia, Jairo Quiroga, Alberto Insuasty, Andres Coneo, Oscar Vidal, Edgar Márquez and Daniel Insuasty, QSAR Studies, Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Novel Quinolinone-Based Thiosemicarbazones against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Antibiotics, 2023, 12 (1), 61.

- Andrea Bacci, Francesca Corsi, Massimiliano Runfola, Simona Sestito, Ilaria Piano, Clementina Manera, Giuseppe Saccomanni, Claudia Gargini and Simona Rapposelli, Design, Synthesis, and In Vitro Evaluation of Novel 8-Amino-Quinoline Combined with Natural Antioxidant Acids. Pharmaceuticals, 2022, 15 (6), 688. [CrossRef]

- Mamdouh F. A. Mohamed and Gamal El-Din A. Abuo-Rahma, Molecular Targets and Anticancer Activity of Quinoline−Chalcone Hybrids: Literature Review. RSC Adv. 2020, 10 (52), 31139−31155. [CrossRef]

- Y. S. Kivshar, Nonlinear optics: The next decade, Opt. Exp. 16 (2008) 22126. [CrossRef]

- Jean M. F. Custodio, Giulio D. C. D’Oliveira, Fernando Gotardo, Leandro H. Z. Cocca, Leonardo De Boni, Caridad N. Perez, Lauro J. Q. Maia, Clodoaldo Valverde, Francisco A. P. Osório, and Hamilton B. Napolitano, Chalcone as Potential Nonlinear Optical Material: A Combined Theoretical, Structural, and Spectroscopic Study, J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 10, 5931–594. [CrossRef]

- P. N. Prasad, D. J. Williams, Introduction to Nonlinear Optical Effects in Organic Molecules and Polymers, Wiley, New York, 1991.

- R. L. Sutherland, Hand book of Nonlinear Optics, second edition, Marcel Dekker Inc, 2003.

- Humera Baig, Amber Iqbal, Alvina Rasool, Syed Zajif Hussain, Javed Iqbal, Meshari Alazmi, Nawaf Alshammari, Amira Alazmi, Amer AlGhadhban, Abdel Moneim E. Sulieman, Kamaleldin B. Said,Habib-ur Rehman, and Rahman Shah Zaib Saleem, Synthesis and Photophysical, Electrochemical, and DFT Studies of Piperidyl and Pyrrolidinyl Chalcones, ACS Omega 2023, 8, 28499−28510. [CrossRef]

- Daniel Insuasty, Mario Mutis, Jorge Trilleras, Luis A. Illicachi, Juan D. Rodríguez, Andrea Ramos-Hernández, Homero G. San-Juan-Vergara, Christian Cadena-Cruz, José R. Mora, José L. Paz, Maximiliano Méndez-López, Edwin G. Pérez, Margarita E. Aliaga, Jhesua Valencia, and Edgar Márquez, Synthesis, Photophysical Properties, Theoretical Studies, and Living Cancer Cell Imaging Applications of New 7-(Diethylamino)quinolone Chalcones, ACS Omega 2024, 9, 17, 18786-18800. [CrossRef]

- M.N. Gomes, E.N. Muratov, M. Pereira, J.C. Peixoto, L.P. Rosseto, P.V.L. Cravo, C.H. Andrade, B.J. Neves, Chalcone Derivatives: Promising Starting Points for Drug Design, Molecules, 2017, 22, 1210. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Kusanur, M.V. Kulkarni, A Novel Route for the Synthesis of Recemic 4-(Coumaryl) Alanines and Their Antimicrobial Activity, , Asian J. of Chem., 2014, 26(4), 1077. [CrossRef]

- Raviraj Kusanur, Manjunath Ghate, Manohar Kulkarni, Synthesis and biological activities of some substituted 4-{4-(1, 5-diphenyl-1H-pyrazol-3-yl) phenoxymethyl} coumarins, Indian Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry, 2004,13 (3), 201-204.

- Dayanand Patagar, Akshay Uttarkar, Swarna M Patra, Jagadish H Patil, Raviraj Kusanur, Vidya Niranjan, H G Ashok Kumar, Spiro benzodiazepine substituted fluorocoumarins as potent anti-anxiety agents, Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry, 2021,47 (2), 390-398. [CrossRef]

- M. Sheik-Bahae, A.A. Said, T.H. Wei, D.J. Hagan, E.W. Van Stryland, Sensitive measurement of optical nonlinearities using a single beam, IEEE J. Quant. Electron., 1990, 26, 760–769. [CrossRef]

- M. Sheik Bahae, D.C. Hutchings, D.J. Hagan, E.W. Van Stryland, Dispersion of bound electronic nonlinear refraction in solids, IEEE J. Quant. Electron, 199127, 1296–1309. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Frisch, G. W. Trucks, H. B. Schlegel, G. E. Scuseria, M. A. Robb, J. R. Cheeseman, G. Scalmani, V. Barone, G. A. Petersson, H. Nakatsuji, X. Li, M. Caricato, A. V. Marenich, J. Bloino, B. G. Janesko, R. Gomperts, B. Mennucci, H. P. Hratchian, J. V. Ortiz, A. F. Izmaylov, J. L. Sonnenberg, D. Williams-Young, F. Ding, F. Lipparini, F. Egidi, J. Goings, B. Peng, A. Petrone, T. Henderson, D. Ranasinghe, V. G. Zakrzewski, J. Gao, N. Rega, G. Zheng, W. Liang, M. Hada, M. Ehara, K. Toyota, R. Fukuda, J. Hasegawa, M. Ishida, T. Nakajima, Y. Honda, O. Kitao, H. Nakai, T. Vreven, K. Throssell, J. A. Montgomery, Jr., J. E. Peralta, F. Ogliaro, M. J. Bearpark, J. J. Heyd, E. N. Brothers, K. N. Kudin, V. N. Staroverov, T. A. Keith, R. Kobayashi, J. Normand, K. Raghavachari, A. P. Rendell, J. C. Burant, S. S. Iyengar, J. Tomasi, M. Cossi, J. M. Millam, M. Klene, C. Adamo, R. Cammi, J. W. Ochterski, R. L. Martin, K. Morokuma, O. Farkas, J. B. Foresman, and D. J. Fox, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2016. Gaussian 16, Revision C.01.

- Narayanan Eswar, Ben Webb, Marc A Marti-Renom, M S Madhusudhan, David Eramian, Min-Yi Shen, Ursula Pieper, Andrej Sali, Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using Modeller, Curr. Protoc. Bioinforma., 2006, 15, Oct: Chapter 5: Unit-5.6.

- M. Ahmad, W. Bauer, S. Katz, Ulcerative colitis, hyperamylasemia, and asymptomatic pancreatic calcifications: making the case for pancreatitis as an extra luminal manifestation., Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 2307–9.

- A.K. Malde, L. Zuo, M. Breeze, M. Stroet, D. Poger, P.C. Nair, C. Oostenbrink, A.E. Mark, An Automated Force Field Topology Builder (ATB) and Repository: Version 1.0, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2011, 7, 4026–4037. [CrossRef]

- R. Anandakrishnan, B. Aguilar, A. V Onufriev, H++ 3.0: automating pK prediction and the preparation of biomolecular structures for atomistic molecular modeling and simulations., Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, W537-41. [CrossRef]

- P. Mark, L. Nilsson, Structure and Dynamics of the TIP3P, SPC, and SPC/E Water Models at 298 K, J. Phys. Chem. A., 2001,105, 9954–9960. [CrossRef]

- S.C. Tuble, J. Anwar, J.D. Gale, An Approach to Developing a Force Field for Molecular Simulation of Martensitic Phase Transitions between Phases with Subtle Differences in Energy and Structure, J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2004,126, 396–405. [CrossRef]

- T. Darden, D. York, L. Pedersen, Particle mesh Ewald: An N ⋅log( N ) method for Ewald sums in large systems, J. Chem. Phys., 1993, 98, 10089–10092.

- B. Hess, H. Bekker, H.J.C. Berendsen, J.G.E.M. Fraaije, LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations, J. Comput. Chem., 1997, 18, 1463–1472.

- B.R. Miller, T.D. McGee, J.M. Swails, N. Homeyer, H. Gohlke, A.E. Roitberg, MMPBSA.py : An Efficient Program for End-State Free Energy Calculations, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 2012, 8, 3314–3321.

- R. Kumari, R. Kumar, A. Lynn, g_mmpbsa —A GROMACS Tool for High-Throughput MM-PBSA Calculations, J. Chem. Inf. Model., 2014, 54, 1951–1962.

- N.B. Gummagol, D.A. Yaraguppi, S.B. Patil, P.S. Patil, N.R. Patil, N.H. Ayachit, Exploring the anticancer potential of novel chalcone derivatives: Synthesis, characterization, computational analysis, and biological evaluation against breast cancer, J. Mol. Struct., 2025, 1320, 139586. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Muddapur, N. R. Patil, S. S. Patil, R. M. Melavanki and R. A. Kusanur, Estimation of Ground and Excited State Dipole Moments of aryl Boronic acid Derivative by Solvatochromic Shift Method, J. Fluoresc., 24, (2014) 1651–165949. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Patil, G. V. Muddapur, N. R. Patil, R. M. Melavanki, R. A. Kusanur, Fluorescence characteristics of aryl boronic acid derivative (PBA), Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 138, (2015) 85-91.

- G. V. Muddapur, R. M. Melavanki, P. G. Patil, D. Nagaraja, N. R. Patil, Photophysical properties of 3MPBA: Evaluation and co-relation between solvatochromism and quantum yield in different solvents, J. Mol. Liq., 224(1), (2016) 201-210. [CrossRef]

- G. V. Muddapur, R M Melavanki, K Sharma, H T Srinivasa, J Thipperudrappa, Fluorescence properties of aromatic asymmetric di-ketone compound in polar and non-polar solvents, Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1473 (1), (2020) 012044.

- R.M. Melavanki, G. V. Muddapur, H.T. Srinivasa, S.S. Honnanagoudar, N. R. Patil Solvation, rotational dynamics, photophysical properties study of aromatic asymmetric di-ketones: An experimental and theoretical approach J. Mol. Liq., 337 (2021) 116456.

- Sirilak Wangngae, Kantapat Chansaenpak, Jukkrit Nootem, Utumporn Ngivprom, Sirimongkon Aryamueang, Rung-Yi Lai, and Anyanee Kamkaew, Photophysical Study and Biological Applications of Synthetic Chalcone-Based Fluorescent Dyes, Molecules 2021, 26, 2979. [CrossRef]

- Humera Baig, Rimsha Irfan, Alvina Rasool, Syed Zajif Hussain, Sabir Ali Siddique, Javed Iqbal, Meshari Alazmi, Nawaf Alshammari, Amira Alazmi, Amer AlGhadhban, Abdel Moneim E. Sulieman, Kamaleldin B. Said, Habib-ur- Rehman, Rahman Shah Zaib Saleem, Synthesis, photophysical, voltammetric, and DFT studies of 4-aminochalones, J. Photochem. & Photobiol., A: Chemistry, 2023, 442(1), 114790.

- Tanisha Sachdeva , Marilyn Daisy Milton, AIEE active novel red-emitting D-π-A phenothiazine chalcones displaying large Stokes shift, solvatochromism and “turn-on” reversible mechano fluorochromism, Dyes and Pigments, 2020,181, 108539.

- Shangfeng Wang, Benhao Li, Fan Zhang, Molecular Fluorophores for Deep-Tissue Bioimaging, ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1302−1316. [CrossRef]

- NR Patil, Raveendra M Melavanki, SB Kapatkar, NH Ayachit, J Saravanan, Solvent Effect on Absorption and Fluorescence Spectra of Three Biologically Active Carboxamides (C1, C2 and C3). Estimation of Ground and Excited State Dipole Moment from Solvatochromic Method Using Solvent Polarity Parameters, J. Fluoresc., 2011, 21, 1213–1222. [CrossRef]

- Raveendra M Melavanki, NR Patil, SB Kapatkar, NH Ayachit, Siva Umapathy, J Thipperudrappa, AR Nataraju, Solvent effect on the spectroscopic properties of 6MAMC and 7MAMC, J. Mol. Liq., 2011, 158 (2), Pages 105-110. [CrossRef]

- Tapati Mallik & Debashis Banerjee, Solvation and Solvatochromism: An Overview, Ind. J. Chem., 2022, 61, 472-481. [CrossRef]

- P. Bhavya, Raveendra Melavanki, M. N. Manjunatha, Varsha Koppal, N. R. Patil and V.T. Muttannavar, Solvent Effects on the Photophysical Properties of Coumarin Dye, AIP Conference Proceedings 1953, (2018), 080022.

- V. V. Koppal, G. V. Muddapur, N. R. Patil and R. M. Melavanki, Spectroscopic studies of biologically active coumarin laser dye: Evaluation of dipole moments by solvatochromic shift method, AIP Conf. Proc. 1728, (2016), 020411.

- V.V. Koppal, P.G. Patil, R.M. Melavanki and N.R. Patil., Study on Solvent Effect and Estimation of Dipole Moments of Laser Dye 3ADHC, Materials Today: Proceedings 5 (2018) 2759–2764. [CrossRef]

- Varsha V. Koppal, P. G. Patil, Raveendra Melavanki, Raviraj Kusanur, and N. R. Patil, Solvent Effect on the Relative Quantum Yield and Preferential Solvation of Biologically Active Coumarin Derivative, Macromol. Symp., 387, (2019), 1800210. [CrossRef]

- A. Gaur, P. Gaur, D. Sharma, D.K. Sharma, N. Singh, B.P. Malik, Study of transmittance dependence closed-aperture Z-scan curves in the materials with nonlinear refraction and strong absorption, Optik 123 (2012) 1583–1587. [CrossRef]

- X.Q. Yan, Z.B. Liu, X.L. Zhang, W.Y. Zhou, J.G. Tian, Polarization dependence ofZ-scan measurement: theory and experiment, Opt Express 17 (2009) 6397–6406. [CrossRef]

- F. D’Amore, J. Osmond, S. Destri, M. Pasini, V. Rossi, W. Porzio, Effects of backbone modification on the linear and third order nonlinear optical properties in fluorene based copolymers, Synth. Met. 149 (2005) 123–127. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Kiran, D. Udayakumar, K. Chandrashekaran, A.V.Adhikari, H.D.Shashikala, Z-Scan and degenerate four wave mixing studies on newly synthesized copolymers containing alternating substituted thiophene and 1,3,4-oxadiazole units, J. Phys. B 39 (18) (2006) 3747-3756. [CrossRef]

- A. Ekbote, P.S.Patil, S.R. Maidur, T.S. Chia, C.K. Quah, Structural, third-order optical nonlinearities and figures of merit (E)-1-(3-substituted phenyl)-3-(4-fluorophenyl) prop2-en-1-one under CW regime: new Chalcone derivatives for optical limiting applications, Dyes Pigments 139 (2017) 720-729. [CrossRef]

- P. Thanikaivelan, V. Subramanian), J. Raghava Rao, Balachandran Unni Nair, Application of quantum chemical descriptor in quantitative structure activity and structure property relationship, Chem. Phy. Lett., 2000, 323, 59–70. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Murray, K. Sen, Molecular electrostatic potentials: concepts and applications, Elsevier, 1996.

- E. Scrocco, J. Tomasi, Advances in Quantum Chemistry, Vol. 2, P. Lowdin, ed, in, Academic Press, New York, 1978.

- Nanjundaswamy, S., Gurumallappa, Hema, M.K., Karthik, C.S., Rajabathar, J.R., Arokiyaraj, S., Lokanath, N.K., Mallu, P., Synthesis, crystal structure, in-silico ADMET, molecular docking and dynamics simulation studies of thiophene-chalcone analogues. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1247, 131365.

- Mahalakshmi Thillainayagam, Kullappan Malathi & Sudha Ramaiah, In - Silico molecular docking and simulation studies on novel chalcone and flavone hybrid derivatives with 1, 2, 3-triazole linkage as vital inhibitors of Plasmodium falciparum dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2018, 36, 3993–4009.

- Mahalakshmi Thillainayagam, Kullappan Malathi, Anand Anbarasu, Harpreet Singh, Renu Bahadur & Sudha Ramaiah, Insights on inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum plasmepsin I by novel epoxyazadiradione derivatives – molecular docking and comparative molecular field analysis, Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2019, 37 (12), 3168-3182. [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S.H., Uzairu, A., Shallangwa, G.A., Uba, S., Umar, A.B.,. In-silico activity prediction, structure-based drug design, molecular docking and pharmacokinetic studies of selected quinazoline derivatives for their antiproliferative activity against triple negative breast cancer (MDA-MB231) cell line, Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 2. [CrossRef]

- Kamala K. Vasu, Hemantkumar D. Ingawale, Sneha R. Sagar, Jayesh A. Sharma, Daivat H. Pandya, and Milee Agarwal, 2-((1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)methyl)-3-phenylquinazolin-4(3H)-ones: Design, Synthesis and Evaluation as Anti-cancer Agents, Curr. Bioact. Compd., 2018, 14, 254–263. [CrossRef]

- Giuseppa Pistritto, Daniela Trisciuoglio, Claudia Ceci, Alessia Garufi, and Gabriella D’Orazi, Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging (Albany. NY)., 2016, 8, 603–619. [CrossRef]

- Zbigniew Darzynkiewicz, Elzbieta Bedner, Piotr Smolewski, Flow cytometry in analysis of cell cycle and apoptosis. Semin. Hematol. 2001, 38, 179–193.

| Sl. No. | Solvents |

λa (nm) |

λf (nm) |

(cm-1) |

(cm-1) |

) (cm-1) |

(cm-1) |

(cm-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pentane | 320.00 | 375.00 | 31250.00 | 26666.67 | 4583.33 | 57916.67 | 28958.33 |

| 2 | Hexane | 320.00 | 376.60 | 31250.00 | 26553.37 | 4696.63 | 57803.37 | 28901.69 |

| 3 | Heptane | 325.00 | 382.00 | 30769.23 | 26178.01 | 4591.22 | 56947.24 | 28473.62 |

| 4 | Cyclohexane | 331.90 | 390.00 | 30129.56 | 25641.03 | 4488.53 | 55770.58 | 27885.29 |

| 5 | 1 4 Dioxane | 332.00 | 392.00 | 30120.48 | 25510.20 | 4610.28 | 55630.69 | 27815.34 |

| 6 | Toluene | 335.20 | 396.00 | 29832.94 | 25252.53 | 4580.41 | 55085.46 | 27542.73 |

| 7 | TCE | 338.00 | 402.00 | 29585.80 | 24875.62 | 4710.18 | 54461.42 | 27230.71 |

| 8 | DEE | 341.70 | 410.00 | 29265.44 | 24390.24 | 4875.19 | 53655.68 | 26827.84 |

| 9 | DCE | 343.00 | 415.00 | 29154.52 | 24096.39 | 5058.13 | 53250.90 | 26625.45 |

| 10 | EA | 344.90 | 418.00 | 28993.91 | 23923.44 | 5070.47 | 52917.36 | 26458.68 |

| 11 | THF | 348.00 | 423.00 | 28735.63 | 23640.66 | 5094.97 | 52376.29 | 26188.15 |

| 12 | Acetonitrile | 351.30 | 428.00 | 28465.70 | 23364.49 | 5101.21 | 51830.18 | 25915.09 |

| 13 | DMF | 352.00 | 430.00 | 28409.09 | 23255.81 | 5153.28 | 51664.90 | 25832.45 |

| 14 | DMSO | 355.00 | 435.00 | 28169.01 | 22988.51 | 5180.51 | 51157.52 | 25578.76 |

| 15 | Water | 360.00 | 441.00 | 27777.78 | 22675.74 | 5102.04 | 50453.51 | 25226.76 |

| 16 | Decanol | 362.00 | 445.00 | 27624.31 | 22471.91 | 5152.40 | 50096.22 | 25048.11 |

| 17 | Octanol | 363.00 | 446.00 | 27548.21 | 22421.52 | 5126.68 | 49969.73 | 24984.87 |

| 18 | Pentanol | 364.00 | 448.00 | 27472.53 | 22321.43 | 5151.10 | 49793.96 | 24896.98 |

| 19 | Butanol | 367.00 | 452.00 | 27247.96 | 22123.89 | 5124.06 | 49371.85 | 24685.93 |

| 20 | Isopropanol | 368.00 | 455.00 | 27173.91 | 21978.02 | 5195.89 | 49151.94 | 24575.97 |

| 21 | Ethanol | 369.00 | 458.00 | 27100.27 | 21834.06 | 5266.21 | 48934.33 | 24467.17 |

| 22 | Methanol | 370.00 | 462.00 | 27027.03 | 21645.02 | 5382.01 | 48672.05 | 24336.02 |

| Correlations | Slope (m) | Intercept |

Correlation factor (r) |

Number of solvents (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bilot Kawaski’s correlation |

786.07 | 4574.17 | 0.98 | 22 |

| -8673.38 | 61402.92 | 0.99 | 22 | |

| Lippert - Mataga | 2304.82 | 4561.99 | 0.98 | 22 |

| Bakhshiev’s | 802.98 | 4588.12 | 0.97 | 21 |

| Kawski-Chamma-Viallet’s | -9177.84 | 33602.13 | 0.99 | 21 |

| Reichardt | 937.53 | 4651.53 | 0.98 | 20 |

| Sl. No. | Solvents | N | OD | Fint | Φ | τ0 (ns) |

Kr 109 (S-1) |

Knr 109 (S-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hexane | 1.375 | 0.240 | 156847.12 | 0.578 | 1.320 | 0.438 | 0.320 |

| 2 | Heptane | 1.388 | 0.342 | 46816.213 | 0.123 | 1.630 | 0.076 | 0.538 |

| 3 | Cyclohexane | 1.426 | 0.118 | 113862.115 | 0.917 | 1.284 | 0.714 | 0.064 |

| 4 | Pentanol | 1.409 | 0.122 | 23826.105 | 0.181 | 1.575 | 0.115 | 0.520 |

| 5 | Butanol | 1.399 | 0.122 | 49067.2595 | 0.368 | 1.458 | 0.252 | 0.433 |

| 6 | Iso-Propanol | 1.378 | 0.119 | 84261.500 | 0.629 | 1.729 | 0.364 | 0.215 |

| 7 | Ethanol | 1.361 | 0.239 | 109265.055 | 0.396 | 1.591 | 0.249 | 0.380 |

| 8 | Methanol | 1.328 | 0.118 | 109265.055 | 0.763 | 2.045 | 0.373 | 0.116 |

| 9 | Acetonitrile | 1.344 | 0.140 | 47916.138 | 0.289 | 1.840 | 0.157 | 0.386 |

| 10 | DMSO | 1.479 | 0.558 | 304283.865 | 0.558 | 1.964 | 0.284 | 0.225 |

| Molecule | α0 (cm-1) |

β (cmW-1) x10-5 |

n2 (cm2W-1) x 10-9 |

Re χ(3) (e.s.u) x 10-6 |

Im χ(3) (e.s.u) x 10-6 |

χ(3) (e.s.u) x 10-6 |

γh (e.s.u) x 10-26 |

OL kJ/cm2 |

W x 103 |

T |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3NPEO | 4.52 | 1.82 | -0.62 | 0.84 | 0.44 | 0.94 | 0.39 | 4.06 | 49.4 | 0.15 |

| Compound | HOMO (eV) | LUMO (eV) | E0−0 | λonset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theor. | Expl. | Theor. | Expl. | Theor. | Expl. | Ao | |

| 3NPEO | -6.855 | -4.849 | -2.817 | -1.498 | 4.020 | 3.351 | 370 |

| Energy Term | Energy in kJ/mol |

|---|---|

| van der Waal energy | -166.204 +/- 12.377 |

| Electrostatic energy | -25.227 +/- 7.903 |

| Polar solvation energy | 83.791 +/- 5.629 |

| SASA energy | -18.248 +/- 0.662 |

| Binding energy | -125.888 +/- 11.935 |

| Treatments and cell line | Early Apoptosis | Late Apoptosis | Total Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3NPEO - (MDAMB-231) | 20.80 | 3.10 | 23.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).