Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

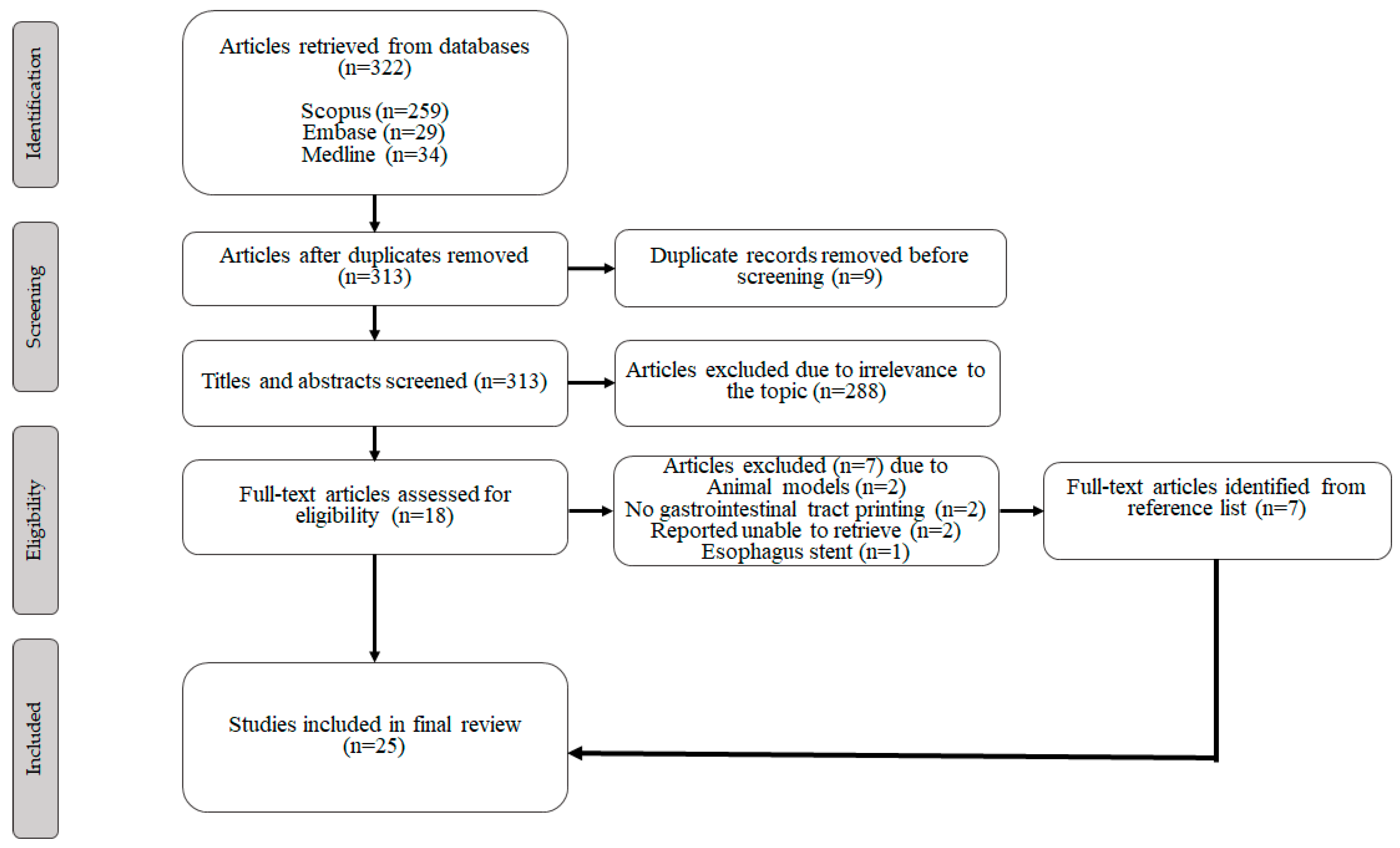

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Article Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics and Findings

3.3. 3D Printing Details

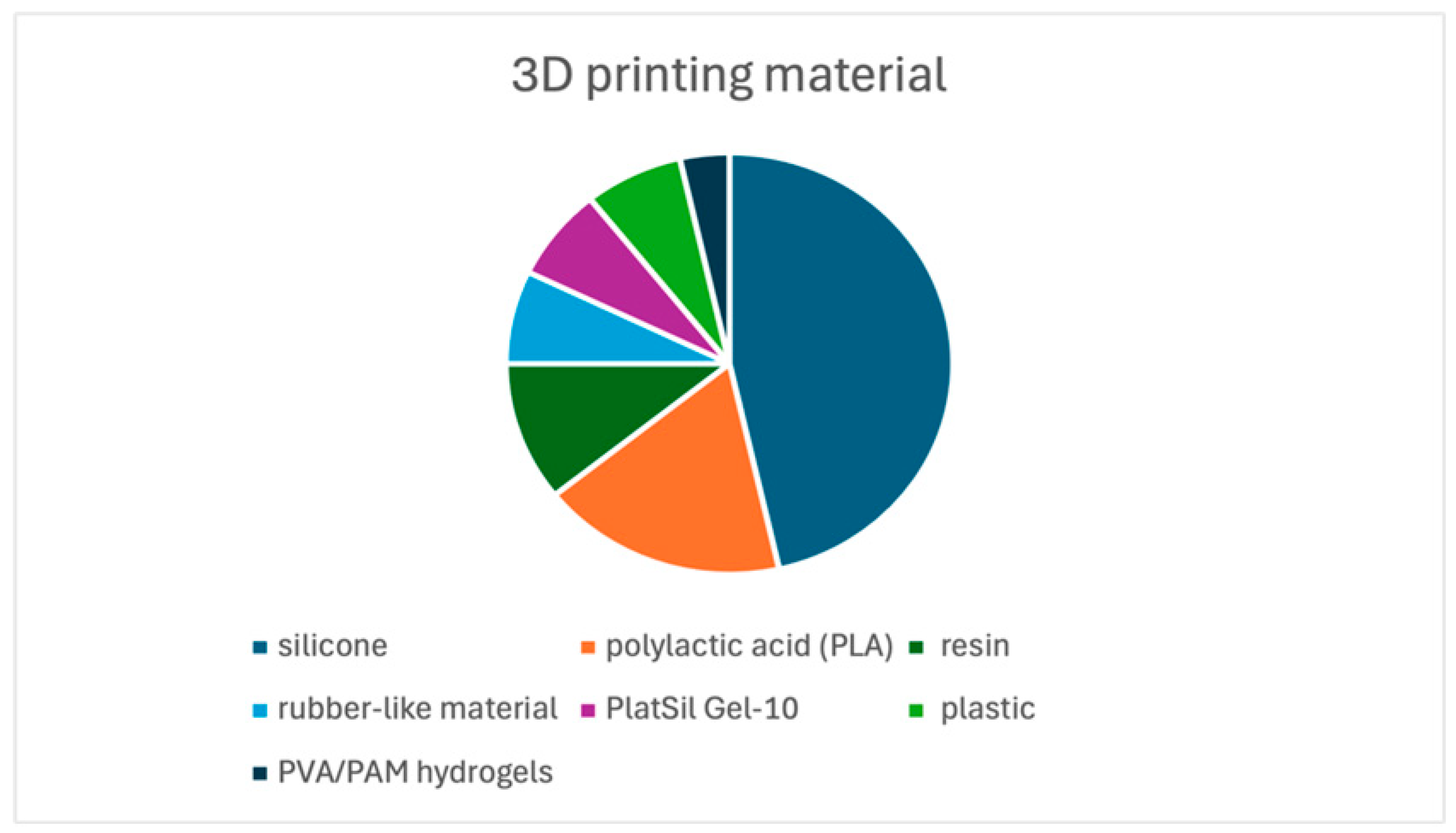

3.3.1. 3D Printing Processing and Materials

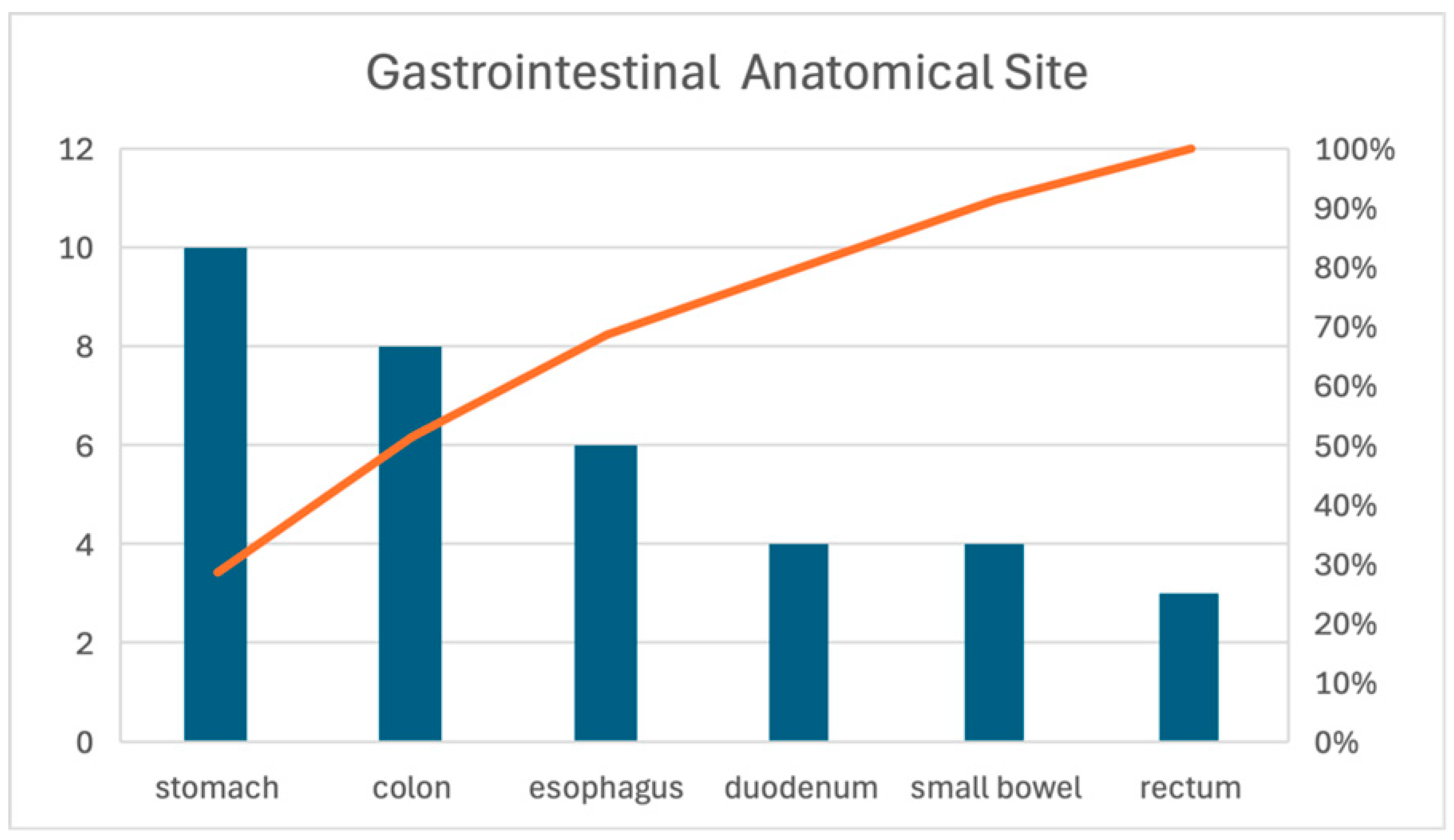

3.3.2. Printed Gastrointestinal Organs

3.4. Purposes of 3D-Printed Gastrointestinal Models

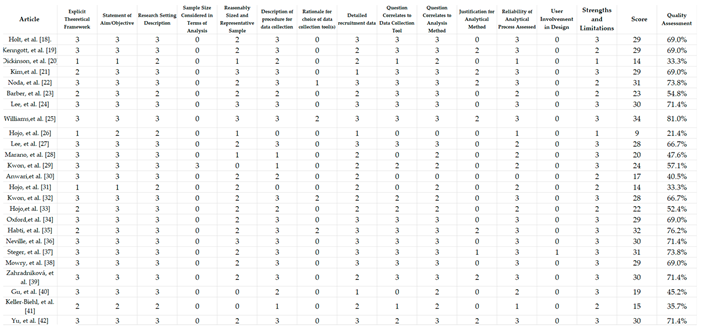

3.5. Quality of the Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. 3D Printing Methods and Materials for the Gastrointestinal Tract

4.2. 3D Printing of Gastrointestinal Organs and Their Applications

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| BT | Balloon tamponade tube |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| GD | Gastroduodenal |

| HSBA | Hand-sewn bowel anastomosis |

| MR | Magnetic resonance |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| PAM | Polyacrylamide |

| NA | Not applicable |

| QATSDD | Quality assessment tool for studies with diverse designs |

| TEP | Transeosophadeal prosthesis |

References

- R. Javan; D. Herrin; A. Tangestanipoor. Understanding Spatially Complex Segmental and Branch Anatomy Using 3D Printing: Liver, Lung, Prostate, Coronary Arteries, and Circle of Willis. Acad. Radiol. 2016, 23, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, J. S.; Morris, J. M.; Foley, T. A.; Williamson, E. E.; Leng, S.; McGee, K. P.; Kuhlmann, J. L.; Nesberg, L. E.; Vrtiska, T. J. Three-dimensional Physical Modeling: Applications and Experience at Mayo Clinic. Radiographics 2015, 35, 1989–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marconi, S.; Pugliese, L.; Botti, M.; Peri, A.; Cavazzi, E.; Latteri, S.; Auricchio, F. ; Pietrabissa, A Value of 3D printing for the comprehension of surgical anatomy. Surg. Endosc 2017, 31, 4102–4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, I.; Gupta, A.; Sun, Z. Clinical Value of Virtual Reality versus 3D Printing in Congenital Heart Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupulescu C; Sun. Z. 3D printing of patient-specific kidney models to facilitate pre-surgical planning of renal cell carcinoma using CT datasets. AMJ 2021, 14, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, T.; Williams, A.; Sun, Z. Three-Dimensional Printed Liver Models for Surgical Planning and Intraoperative Guidance of Liver Cancer Resection: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci 2023, 13, 10757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ng, C. K. C.; Wong, Y. H.; Yeong, C. H. 3D-Printed Coronary Plaques to Simulate High Calcification in the Coronary Arteries for Investigation of Blooming Artifacts. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D. H.; Wake, N.; Witowski, J.; Rybicki, F. J.; Sheikh, A. Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) 3D Printing Special Interest Group (SIG) clinical situations for which 3D printing is considered an appropriate representation or extension of data contained in a medical imaging examination: abdominal, hepatobiliary, and gastrointestinal conditions. 3D. Print. Med 2020, 6, 13–13. [Google Scholar]

- Finocchiaro, M.; Cortegoso Valdivia, P.; Hernansanz, A.; Marino, N.; Amram, D.; Casals, A.; Menciassi, A.; Marlicz, W.; Ciuti, G.; Koulaouzidis, A. Training Simulators for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy: Current and Future Perspectives. Cancers 2021, 13, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buscaglia, J. M.; Fakhoury, J.; Loyal, J.; Denoya, P. I.; Kazi, E.; Stein, S. A.; Scriven, R.; Bergamaschi, R. Simulated colonoscopy training using a low-cost physical model improves responsiveness of surgery interns. Colorectal. Dis 2015, 17, 530–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. S.; Marks, J. M. Overview of methods for flexible endoscopic training and description of a simple explant model. Asian. J. Endosc. Surg. 2011, 4, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghdel, M.; Alizadeh, A. A.; Ghasemi, Y.; Hosseinpour, H.; Foroutan, H.; Shahriarirad, S.; Imanieh, M. H. Utilization of 3D-Printed Polymer Stents for Benign Esophageal Strictures in Patients with Caustic Ingestion. J. 3D. Print. Med 2021, 5, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povey, M.; Powell, S.; Howes, N.; Vimalachandran, D.; Sutton, P. Evaluating the potential utility of three-dimensional printed models in preoperative planning and patient consent in gastrointestinal cancer surgery. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2021, 103, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontovounisios, C.; Tekkis, P.; Bello, F. 3D imaging and printing in pelvic colorectal cancer: ‘The New Kid on the Block’. Tech. Coloproctol 2019, 23, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yang, D.; Huang, Y.; Liao, K.; Yuan, X.; Hu, B. 3D-printed model in the guidance of tumor resection: a novel concept for resecting a large submucosal tumor in the mid-esophagus. Endoscopy 2020, 52, E273–E274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C; Mulrow, C. D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Br. Med. J 2021, 372, n71–n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirriyeh, R.; Lawton, R.; Gardner, P.; Armitage, G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: the development and evaluation of a new tool. J. Eval. Clin. Pract 2012, 18, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, B. A.; Hearn, G.; Hawes, R.; Tharian, B.; Varadarajulu, S. Development and evaluation of a 3D printed endoscopic ampullectomy training model (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc 2015, 81, 1470–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenngott, H. G.; Wünscher, J. J.; Wagner, M.; Preukschas, A.; Wekerle, A. L.; Neher, P.; Suwelack, S.; Speidel, S.; Nickel, F.; Oladokun, D.; Maier-Hein, L.; Dillmann, R.; Meinzer, H. P.; Müller-Stich, B. P. OpenHELP (Heidelberg laparoscopy phantom): development of an open-source surgical evaluation and training tool. Surg. Endosc 2015, 29, 3338–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, K. J. M. B. S.; Matsumoto, J. M. D.; Cassivi, S. D. M. D. M. S.; Reinersman, J. M. M. D.; Fletcher, J. G. M. D.; Morris, J. M. D.; Wong Kee Song, L. M. M. D.; Blackmon, S. H. M. D. M. P. H. Individualizing Management of Complex Esophageal Pathology Using Three-Dimensional Printed Models. Ann. Thorac. Surg 2015, 100, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G. B.; Park, J.-H.; Song, H.-Y.; Kim, N.; Song, H. K.; Kim, M. T.; Kim, K. Y.; Tsauo, J.; Jun, E. J.; Kim, D. H.; Lee, G. H. 3D-printed phantom study for investigating stent abutment during gastroduodenal stent placement for gastric outlet obstruction. 3D. Print. Med. 2017, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noda, K.; Kitada, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Colvin, H. S.; Hata, T.; Mizushima, T. A novel physical colonoscopy simulator based on analysis of data from computed tomography colonography. Surg. Today 2017, 47, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, S. R.; Kozin, E. D.; Naunheim, M. R.; Sethi, R.; Remenschneider, A. K.; Deschler, D. G. 3D-printed tracheoesophageal puncture and prosthesis placement simulator. Am. J. Otolaryngol 2018, 39, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Ahn, J. Y.; Han, M.; Lee, G. H.; Na, H. K.; Jung, K. W.; Lee, J. H.; Kim, D. H.; Choi, K. D.; Song, H. J.; Jung, H.-Y. Efficacy of a Three-Dimensional-Printed Training Simulator for Endoscopic Biopsy in the Stomach. Gut. Liver 2018, 12, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; McWilliam, M.; Ahlin, J.; Davidson, J.; Quantz, M. A.; Bütter, A. A simulated training model for laparoscopic pyloromyotomy: Is 3D printing the way of the future? J. Pediatr. Surg. 2018, 53, 937–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, D.; Nishikawa, T.; Takayama, T.; Hiyoshi, M.; Emoto, S.; Nozawa, H.; Kawai, K.; Hata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Shuno, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Sasaki, K.; Murono, K.; Ishii, H.; Sonoda, H.; Hoshina, K.; Ishihara, S. 3D printed model-based simulation of laparoscopic surgery for descending colon cancer with a concomitant abdominal aortic aneurysm. Tech. Coloproctol 2019, 23, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. S.; Ahn, J. Y.; Lee, G. H. A Newly Designed 3-Dimensional Printer-Based Gastric Hemostasis Simulator with Two Modules for Endoscopic Trainees (with Video). Gut. Liver 2019, 13, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marano, L.; Ricci, A.; Savelli, V.; Verre, L.; Di Renzo, L.; Biccari, E.; Costantini, G.; Marrelli, D.; Roviello, F. From digital world to real life: A robotic approach to the esophagogastric junction with a 3D printed model. BMC Surg 2019, 19, 153–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, C.-I.; Shin, Y.; Hong, J.; Im, M.; Kim, G. B.; Koh, D. H.; Song, T. J.; Park, W. S.; Hyun, J. J.; Jeong, S. Production of ERCP training model using a 3D printing technique (with video). BMC. Gastroenterol 2020, 20, 145–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwari, V.; Lai, A.; Ursani, A.; Rego, K.; Karasfi, B.; Sajja, S.; Paul, N. 3D printed CT-based abdominal structure mannequin for enabling research. 3D Print. Med. 2020, 6, 3–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojo, D.; Emoto, S.; Kawai, K.; Nozawa, H.; Hata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Ishihara, S. Potential Usefulness of Three-dimensional Navigation Tools for the Resection of Intra-abdominal Recurrence of Colorectal Cancer. J. Gastrointest. Surg 2020, 24, 1682–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Choi, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, M.; Park, Y. K.; Park, D. H.; Kim, N. Modelling and manufacturing of 3D-printed, patient-specific, and anthropomorphic gastric phantoms: a pilot study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18976–18976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojo, D.; Kawai, K.; Murono, K.; Nozawa, H.; Hata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishikawa, T.; Shuno, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Sasaki, K.; Emoto, S.; Ishii, H.; Sonoda, H.; Ishihara, S. Establishment of deformable three-dimensional printed models for laparoscopic right hemicolectomy in transverse colon cancer. ANZ J. Surg 2021, 91, E493–E499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxford, K.; Walsh, G.; Bungay, J.; Quigley, S.; Dubrowski, A. Development, manufacture and initial assessment of validity of a 3-dimensional-printed bowel anastomosis simulation training model. Can. J. Surg 2021, 64, E484–E490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habti, M.; Bénard, F.; Arutiunian, A.; Bérubé, S.; Cadoret, D.; Meloche-Dumas, L.; Torres, A.; Kapralos, B.; Mercier, F.; Dubrowski, A.; Patocskai, E. Development and Learner-Based Assessment of a Novel, Customized, 3D Printed Small Bowel Simulator for Hand-Sewn Anastomosis Training. Curēus 2021, 13, e20536–e20536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, J. J.; Chacon, C. S.; Haghighi-Osgouei, R.; Houghton, N.; Bello, F.; Clarke, S. A. Development and validation of a novel 3D-printed simulation model for open oesophageal atresia and tracheo-oesophageal fistula repair. Pediatr. Surg. Int 2022, 38, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, J.; Kwade, C.; Berlet, M.; Krumpholz, R.; Ficht, S.; Wilhelm, D.; Mela, P. The colonoscopic vacuum model–simulating biomechanical restrictions to provide a realistic colonoscopy training environment. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg 2023, 18, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowry, C.; Kohli, R.; Bhat, C.; Truesdale, A.; Menard-Katcher, P.; Scallon, A.; Kriss, M. Gastroesophageal Balloon Tamponade Simulation Training with 3D Printed Model Improves Knowledge, Skill, and Confidence. Dig. Dis. Sci 2023, 68, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahradniková, P.; Babala, J.; Pechanová, R.; Smrek, M.; Vitovič, P.; Laurovičová, M.; Bernát, T.; Nedomová, B. Inanimate 3D printed model for thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula. Front. Pediatr 2023, 11, 1286946–1286946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Jang, H.-L.; Choi, D.-W.; Kim, K. S.; Shin, Y. R.; Cheung, D. Y.; Lee, B. I.; Kim, J. I.; Lee, H. H. Development of colonic stent simulator using three-dimensional printing technique: a simulator development study in Korea. Clin. Endsc 2024, 57, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller-Biehl, L.; Otoya, D.; Khader, A.; Timmerman, W.; Fernandez, L.; Amendola, M. Just the gastrointestinal stromal tumor: A case report of medical modeling of a rectal gastrointestinal stromal tumor. SAGE. Open. Med. Case. Rep 2024, 12, 2050313X231211124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Xu, X.; Ma, L.; Zhao, F.; Mao, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z. Versatile and Tunable Performance of PVA/PAM Tridimensional Hydrogel Models for Tissues and Organs: Augmenting Realism in Advanced Surgical Training. ACS. Appl. Bio. Mater 2024, 7, 6261–6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masood SH; Song WQ. Development of new metal/polymer materials for rapid tooling using fused deposition modelling. Mater. Design 2004, 25, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwah OM; Shukri MS; Mohamad EJ; Johar MA; Haq RH; Khirotdin RK. Direct investment casting for pattern developed by desktop 3D printer. Matec Web of Conferences 2017, 135, 8. [Google Scholar]

| Search Strategy 1 |

AND |

Search Strategy 2 |

AND |

Search Strategy 3 |

| “3D print” or “3D-printed” or “3D printing” or “3 dimensional print” or “3 dimensional printed” or “3 dimensional printing” or “three dimensional print” or “three dimensional printed” or “three dimensional printing” or “additive manufacturing” | “gastrointestinal” or “gastric” or “stomach” or “colon” or “intestine”* or “esophagus” or “bowel” or “duodenum” or “rectum” | “medical education” or “medical training” or “presurgical” or “surgical plan” or “surgical planning” or “simulation” |

| Article | Year | Purpose | Country of Origin | Study Design | Sample Size | Key Findings | Limitations | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holt et al [18] |

2015 |

Develop a training model that can be used to improve technical skills, knowledge, and confidence in performing endoscopic ampullectomy |

USA |

Experimental study |

Stomach and duodenum model n = 1; participants n = 16 |

The training increased the confidence of 11 participants in using the model, with a mean score of 2.2 to 2.9. Participants’ ampullectomy technique improved (66.7%), which continued to increase with additional sessions involving the use of the model (73.3%). The model had an overall visual realism score of 3.2. | Resistance was encountered when passing through the stomach. There was a separation potential during endoscope maneuvers when using a rigid base and ampoule holder combination with a flexible stomach–duodenum. |

||||||||||||||

| Kenngott et al [19] |

2015 | Design a phantom with realistic anatomy, haptics, modularity, and reproducibility |

Germany |

Experimental study |

Torso model n=1; Rectum models n = 10; surgical residents n = 5; surgical consultant n = 1 | Accurate reproduction from 3D digital model to silicone organ was achieved. Accuracy of the silicone rectal models showed an average mean square error of 2.26 mm when compared to the original CT images. | The overall haptic realism was not calculated. |

||||||||||||||

| Dickinson et al [20] |

2015 | Develop 3D-printed models for complex esophageal cases |

USA |

Case report | Esophagus model n = 2 |

These 3D-printed models provided a good understanding of the anatomic relationships of complex esophagus cases. | The sample size was small. |

||||||||||||||

| Kim et al [21] |

2017 | Develop a flexible anthropomorphic 3D-printed model of malignant gastroduodenal (GD) strictures for an in vitro experiment | Korea | Experimental study | Gastroduodenal model n = 1 |

The 3D-printed GD phantom model aided in comparing food passage between the stent abutment and non-stent abutment. |

The flexibility of the 3D-printed model was not sufficient to mimic actual GD properties and lacked gastric peristalsis. |

||||||||||||||

| Noda et al [22] | 2017 | Design a physical simulator using 3D printing technology for a more realistic colonoscope insertion | Japan | Experimental study | Colonoscopy model n=1. Very experienced colonoscopists n = 5; experienced colonoscopists n = 9; less experienced colonoscopists n = 2 | The new simulator was determined to be significantly more realistic than the CM15 model in terms of anatomical structure, visual response, haptic response, and looping. | This simulator was made from stiff silicone and did not allow complete deflation | ||||||||||||||

| Barber et al [23] | 2018 | Develop a reusable three-dimensional (3D)-printed tracheoesophageal prosthesis (TEP) simulator to facilitate comprehension and rehearsal before actual procedures | USA | Experimental study | Esophageal lumen n = 1; junior residents n = 5; senior residents n = 5 | All 10 participants agreed that the simulator exercise provided a beneficial experience, anatomic visualization, and safe practice for actual TEP procedures. | It was a small-sample-size study and lacked longitudinal data. There was no follow-up to validate the survey responses from junior and senior residents. | ||||||||||||||

|

Lee et al [24] |

2018 | Create a stomach model for biopsy training and investigate its efficacy and realism | Korea | Experimental study | Stomach model n = 1; residents n = 10; first-year fellows n = 6; second-year fellows n = 5; faculty members n = 5 | The time taken to complete the training procedure with the 3D biopsy simulator decreased significantly with repeated trials (the completion times were significantly shorter than that in the first trial in all of these groups: 169. 6 versus 347 seconds in the resident group; 85.7 versus 143.8 seconds in the first year fellow group; 96 versus 127.2 seconds in the second year fellow group and 91.2 versus 114.2 seconds in the faculty group, with p all <0.05). | Gastric peristalsis and the movement of the stomach owing to heartbeat and respiration were not reproduced. The elasticity could not reach the same level as that of a real stomach. There was a possible bias in evaluating the simulator using questionnaires. | ||||||||||||||

| Williams et al [25] | 2018 | Evaluate the use of a 3D model of infant hypertrophic pyloric stenosis as a teaching tool for surgical residents | Canada | Experimental study | Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis model n=1; medical students n = 4; general surgery residents n = 8; adult general surgeons n = 3; pediatric surgeons n = 2 | For inexperienced participants, the time to complete the procedure was significantly reduced. Over 70% of the participants agreed that the 3D-printed model accurately simulated certain components of the pyloromyotomy and would be a good training tool for beginners (73.9%) and experts (71.4%). | The sample size was small. The adult version of the box trainer caused some problems with pediatric instruments. Some participants’ self-assessment of their laparoscopic skills was above or below their actual level. Whether practice on this model translated into improved performance in the operating room was not evaluated. | ||||||||||||||

|

Hojo et al [26] |

2019 | Develop a 3D-printed colon model to aid in laparoscopic surgery for descending colon cancer with concomitant abdominal aortic aneurysm | Japan | Case report | Colon model n = 1 | The 3D-printed simulation helped determine the port site and visualize the vascular structures before laparoscopic surgery under challenging conditions. | There was one case that lacked 3D printing details. | ||||||||||||||

| Lee et al [27] | 2019 | Develop a novel 3D-printed simulator to overcome the limitations of the previous endoscopic hemostasis simulators | Korea | Experimental study | Stomach hemostasis model n = 1; endoscopists n = 21 (first-year fellows n = 11; experts n = 10) | The endoscopic handling in the 3D-printed simulator was realistic and reasonable for endoscopic training and could reduce patients’ risks. The procedure time of the beginner group decreased sharply after each trial (procedure completing times for hemoclipping and injection was 116.1 and 161.3 seconds for 1st trial, and reduced to 30.5 and 43 seconds for 5th trial). | The gastric movement was not reproduced. The evaluation using questionnaires could have been biased. The model’s elasticity differed from that of the actual stomach. The model was not compared with other simulators. | ||||||||||||||

| Marano et al [28] | 2019 | Develop a life-size 3D-printed esophagus model that included the proximal stomach, the thoracic aorta, and the diaphragmatic crus for presurgical planning | Italy | Case report | Esophagus model including the proximal stomach n = 1 | This model helped surgeons verify the critical structures and plan all possible maneuvers. | There is no information provided about the number of surgeons participating in the study, and how useful it is to assist with surgical planning. | ||||||||||||||

| Kwon et al [29] | 2020 | Develop a 3D-printed optimized endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) training mode | South Korea | Descriptive survey | Lower stomach and duodenum models n = 8 | The 3D model, which was durable, relatively cheap, and easy to make, allowed trainees to practice various specialized ERCP procedures. | The model did not reflect the same order as humans. Its surface tension was higher than that of the biological tissue. | ||||||||||||||

| Anwari et al [30] | 2020 | Design and construct a low-cost 3D-printed abdominal model with radiologically tissue-realistic and modular anthropomorphism | Canada | Descriptive survey | Small and large bowel model n = 1 | Outline the specific steps in creating a 3D-printed anthropomorphic abdominal model using CT-based scans with radiologically accurate tissue characteristics. | The model was not validated. | ||||||||||||||

| Hojo et al [31] | 2020 | Use 3D-printed models and 3D virtual images to help resect intraabdominal recurrence of colorectal cancer | Japan | Descriptive survey | Colon models n = 2 | The 3D-printed model provided patient-specific anatomy and accurately identified the location of the recurrent lesion for surgeons. | The sample size was small. The study design was retrospective and lacked statistical analyses. | ||||||||||||||

| Kwon et al [32] | 2020 | Develop 3D-printed gastric models with patient-specific, anthropomorphic, and mechanical characteristics similar to those of the human stomach for the intragastric balloon technique | South Korea | Experimental study | Stomach model n = 3 | 3D printed models were printed with materials comprising Agilus, Elastic and Flexa to test their mechanical properties. The mean elongation and tensile strengths of Agilus, Elastic and Flexa were 264%, 145% and 146%, and 1.14, 1.59 and 21.6 MPa, respectively. Agilus was the most flexible material with elongation showing most similar ranges compared to human stomach. | Small sample size with no analysis of these 3D printed models in clinical training or practical value. | ||||||||||||||

| Hojo et al [33] | 2021 | Establish a 3D-printed model comprising the superior mesenteric artery and superior mesenteric vein to optimize laparoscopic right hemicolectomy | Japan | Experimental study | Duodenummodel n = 5 | The application of 3D-printed models simulated the surgical site effectively in colorectal surgery and helped young surgeons understand the anatomical relationship in the variable intraoperative views. | The limitations were the technical difficulties and the time required to create the 3D models. This retrospective study lacked effectiveness in clinical application. | ||||||||||||||

| Oxford et al [34] | 2021 | Test the face and content validity of a 3D-printed bowel anastomosis simulator | Canada | Experimental study | Large intestine n = 1; small intestine n = 1; senior residents n = 3; general surgeons n = 6 | The simulator was regarded as highly realistic and helpful for training. An overall score of 3.98 was ranked for training and 4.11 for simulation-based medical education. | The layers and the wall of the simulator need to be improved. The study lacked control group comparisons with the human bowel and other available simulators. | ||||||||||||||

| Habti et al [35] | 2021 | Develop a 3D-printed, low-cost, and realistic bowel model for hand-sewn bowel anastomosis (HSBA) training | Canada | Experimental study | Small intestine simulator n = 18; surgical residents n = 16 | The simulators were considered realistic and useful tools to learn and practice HSBA. | The residents’ experience was limited. The silicone tore off quickly during suturing. | ||||||||||||||

| Neville et al [36] | 2022 | Create and validate a novel, affordable 3D-printed simulation model for open esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula repair | UK | Experimental study | Esophagus n = 1; experienced group (consultants n = 11; senior registrar n = 1) inexperienced group (senior house officers n = 3; registrars n = 20; consultants n = 5) | The 3D-printed model was cost effective, reusable, and visually and functionally comparable to the actual procedure. The anatomical realism of the model was scored 4.2 out of 5.0, surgical realism 3.9. All participants strongly agreed that the model was useful for paediatric surgery training (mean score 4.9). | The availability of evaluation training resources can differ significantly between countries. Self-reported levels of experience are likely to be inaccurate. The impact of this model-based training on patient outcomes remains unknown. | ||||||||||||||

| Steger et al [37] | 2023 | Develop and validate a novel model using 3D printing technology for adhesion forces between the colon and the abdominal wall | Germany | Experimental study | Colon training model n = 1; medical student n = 1; assistant doctors n = 3; surgeons n = 5; gastrointestinal endoscopy experts n = 2 | The simulator was considered more realistic in terms of anatomical representation, including visual and tactile feedback and colon shape, and it permitted a more realistic distinction between different skill levels. | The impact of this simulator on actual clinical practice outcomes remains unknown. | ||||||||||||||

| Mowry et al [38] | 2023 | Develop a 3D-printed balloon tamponade tube (BT) model and evaluate the performance of gastroenterology fellows and faculty in BT tube placement after training with the model | USA | Experimental study | Esophagus and stomach model n = 1; gastroenterology fellows n = 15; gastroenterology faculty n = 14 | The participants’ knowledge and confidence in placing a BT tube improved significantly after 3D-printed simulator training. Sefl-confidence was significantly increased in both the fellow group (from 3.7 to 6.5, p<0.001) and faculty group (from 4.8 to 8.0, p<0.001). A high degree of satisfaction was from both groups after training. | This was a single-center, small-sample-size study. No data were available on the time to competence or the sustainability of the training beyond 3 months. Moreover, the impact of the training on clinical outcomes was not assessed. | ||||||||||||||

| Zahradniková et al [39] | 2023 | Develop an inexpensive and reusable 3D-printed model for thoracoscopic esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula repair training | Slovakia | Experimental study | Esophagus model n = 1; medical students n = 7; pediatric surgery trainees n = 4; experienced surgeons n = 7 | Most participants observed that the 3D model was an appropriate training tool. The highest ratings in the physical attribute area were for the overall impression and the tool’s usefulness as a simulator with a mean score of 4.66 and 4.75. Participants ranked the model’s realism and working environment with a mean score of 4.25 and 4.5, respectively. | This was a single-center, with a small sample size study. | ||||||||||||||

| Gu et al [40] | 2024 | Develop a large intestine model using 3D-printed technology to provide training in colonoscope insertion, cecum intubation, loop reduction, and stenting within stenotic areas | Korea | Retrospective descriptive study | Large intestine model n = 1 | The model allowed the repeated practice of basic colonoscope insertion and stent placement for colonic stenosis and achieved a life-like representation of colonic malignant tumor-induced stenosis. | The surface tension of silicone is greater than that of human colonic mucosa. Hence, the increased friction between the model surface and the endoscope resulted in strong resistance when the endoscope was inserted. This model did not create a stenosis module at the exact angulation location. | ||||||||||||||

| Keller-Biehl et al [41] | 2024 | Create a 3D rectal model, including the tumor and surrounding structures, to help in preoperative and intraoperative planning | USA | Case report | Gastrointestinal stromal tumour model n = 1 | The 3D model added value to patient care and helped the patient understand the surgery. | The model did not provide any new information or alter the surgical plan. The more expensive model did not offer additional or better information than the cheaper one. | ||||||||||||||

| Yu et al [42] | 2024 | Create a 3D-printed gastrointestinal model using the PVA/PAM tridimensional hydrogel | China | Experimental study | Novel elastic hydrogel model for surgical training n = 1 | The new-material 3D-printed model exhibited high appearance levels, overall difficulty, stomach wall structure, tissue elasticity, and tactile feedback. | The content validity of the model needs to be improved, particularly in terms of enhancing surgical skills and shortening the learning curve. | ||||||||||||||

| Article | Organs Printed | Imaging Modalities Used for 3D Printing | Software for Image Processing and Segmentation | 3D Printer | 3D Printer Materials | 3D Printing Methods | Printing Time | Printing Cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holt et al. [18] |

Stomach and duodenum |

N/A |

Solidworks Corp, Waltham, Mass | Connex 260 v; Stratasys Inc, Eden Prairie, Minn | Silicone rubber | N/A |

N/A |

$1,175 |

|

| Kenngott et al. [19] |

Rectum |

CT image |

MITK (German Cancer Research Center Heidelberg); VTK (Kitware Inc., New York, USA); ITK (Kitware Inc., New York, USA) | Z 450, Z Corporation, Burlington, USA) |

Soft silicone (Ecoflex 0010, Ecoflex 0030, and Dragon SkinFX/Pro) Silicone additive slacker (Smooth-On Inc., Easton, USA) |

N/A |

N/A |

$200 |

|

| Dickinson et al. [20] |

Esophagus |

CT |

Proprietary software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium); Mimics software (Objet350 Connex multi-material, Stratasys, Eden Prairie, MN) | PolyJet 3D printer (Stratasys) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

| Kim, et al. [21] |

Stomach and duodenum |

CT | Inhouse advanced software (AVIEW, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, Korea) | Objet500 Connex3, Stratasys Corporation, Rehovot, Israel | Rubber-like material (Tango™ Family) |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

| Noda et al. [22] |

Sigmoid colon and rectum |

CT | VINCENT Ver3.3, FUJIFILM Med. Sys. Corp. Japan, Tokyo, Japan) | Fortus 360Lmc-L, Stratasys, USA |

Silicone |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

| Barber et al. [23] |

Esophagus |

N/A |

Fusion 360 CAD software (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA) |

Ultimaker 2 + 3D printer (Ultimaker, The Netherlands) | Polylactic acid (PLA) |

N/A |

N/A |

$35–$50 |

|

| Lee et al. [24] |

Stomach |

CT |

3D slicer version 4.5.0 MeshMixer 3.0 (Autodesk, San Rafael, CA, USA) |

(FDM) 3D printer (clone S270 and clone K300, K. Clone, Daejeon, Korea; Replicator 2, MakerBot, Brooklyn, NY, USA) | PlatSil Gel-10 (Polytech, Easton, PA, USA) silicone |

Fused deposition modeling (FDM) |

N/A |

$230 |

|

| Williams et al. [25] |

Stomach |

N/A |

CAD software |

Lulzbot TAZ4 3D printer (Aleph Objects Inc., Colorado, USA) |

PLA silicone rubber (Smooth-On Inc., Pennsylvania, USA) | N/A |

N/A |

$30/stomach |

|

| Hojo et al. [26] |

Colon |

CT |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

|

| Lee et al. [27] |

Stomach |

N/A |

Netfabb professional version 5 (Netfabb GmbH, Lupburg, Germany) | Form 2 (Formlabs Inc, Somerville, MA, USA) |

Soft silicone, Platsil Gel-10 (Polytek, Easton, PA, USA) | N/A |

N/A |

$200 |

|

| Marano et al. [28] |

Esophagus, proximal stomach | CT | N/A |

N/A |

Curing resin |

Stereolithography |

48 working hours |

$230 |

|

| Kwon et al. [29] |

Lower stomach and duodenum | CT |

MeshLab MeshMixer |

3DM DW-06, 3DMaterials, Zeron-2500, Zeron, Korea |

Silicone material (Dragon Skin 10, Smooth-On, USA) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Anwari et al. [30] |

Small and large bowel |

CT |

Vitrea®, v.6.9, Vital Images, Minnetonka, MN Slicer software (Boston, MA); CAD software (Blender, v.2.78 Amsterdam, NL) | Rostock Max V2 printer |

Acrylonitrile butadiene styrene plastic |

FDM |

N/A |

$900 (including the liver, colon, kidneys, and spleen) |

|

| Hojo et al. [31] |

Colon | CT |

N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Kwon et al. [32] |

Stomach |

CT | Mimics Research 17.0 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) |

Elastic/Form 2, Formlabs Inc., MA, USA; Flexa 693/XFAB, DWS Inc., Meccanica, Italy; Agilus Translucent, Vero Magenta/Objet500, Stratasys, Ltd., MN, USA) | Rubber-like material (Agilus Transparent; Stratasys Ltd.) silicone (MED6-6606; NuSil, CA, USA) | Laser stereolithography PolyJet printing |

N/A | N/A | |

| Hojo et al. [33] |

Duodenum |

CT | OsiriX MD (Pixmeo Sarl, Bernex, Switzerland); Meshmixer version 3.5 (Autodesk Inc., Venice, CA, USA) | Airwolf 3D, Fountain Valley, CA, USA) |

PLA |

FDM |

10 h |

$10 |

|

| Oxford et al. [34] |

Small and large bowel | N/A |

Fusion 360 CAD software |

Ultimaker S5 3D printer |

Smooth-On silicone | N/A |

N/A |

$2.67–$131 |

|

| Habti et al. [35] |

Small bowel |

N/A |

Fusion360™ (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA) |

Ultimaker S5 3D printer (Ultimaker B.V., Utrecht, The Netherlands) |

3D-Fuel™ Pro PLA filament material (Fargo, ND) silicone | N/A |

N/A |

$35 |

|

| Neville et al. [36] |

Esophagus |

CT |

ITK-SNAP version 3.8.0; Meshmixer and Fusion 360 (Autodesk Inc., CA, United States) |

Prusa i3 MK3S 3D printer (Prusa Research, Prague, Czech Republic) |

Platinum-catalyzed silicone (Smooth-On Inc., Pennsylvania, United States) | N/A |

N/A |

£20 |

|

| Steger et al [37] |

Colon |

N/A |

Autodesk ReCap; Meshmixer (Autodesk, Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA); Fusion 360 (Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA) | SLA printer Formlabs2 (Formlabs GmbH, Berlin, Germany) |

Durable resin |

N/A | N/A | £260 |

|

| Mowry et al [38] |

Esophagus and a portion of the stomach | N/A |

N/A | N/A | Plastic (NinjaFLEX) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Zahradniková et al [39] |

Esophagus |

CT |

3D Slicer Blender3D |

Prusa i3 MK3S |

Prusament PLA plastic silicone | FDM |

slightly <24 h | N/A |

|

| Gu et al [40] |

Large intestine | CT |

MEDIP PRO v2.0.0 (Medical IP Co., Ltd.) | FDM-type 3D printer |

silicone |

FDM | N/A | N/A | |

| Keller-Biehl et al [41] |

Rectum |

CT |

Mimics Materialise (Belgium), medical segmentation software |

Dynamism xRize 3D printer (Denver, USA); Stratasys J750 Digital Anatomy Printer (Minnesota, USA) | Colorful resin, a translucent and flexible material |

N/A |

6–8 h |

$30–$300 |

|

| Yu et al [42] |

Stomach and small and large bowel |

CT and MR |

Mimics Materialise Magic 24 software |

FDM printer |

PVA/PAM hydrogels |

FDM |

N/A | N/A | |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).