Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

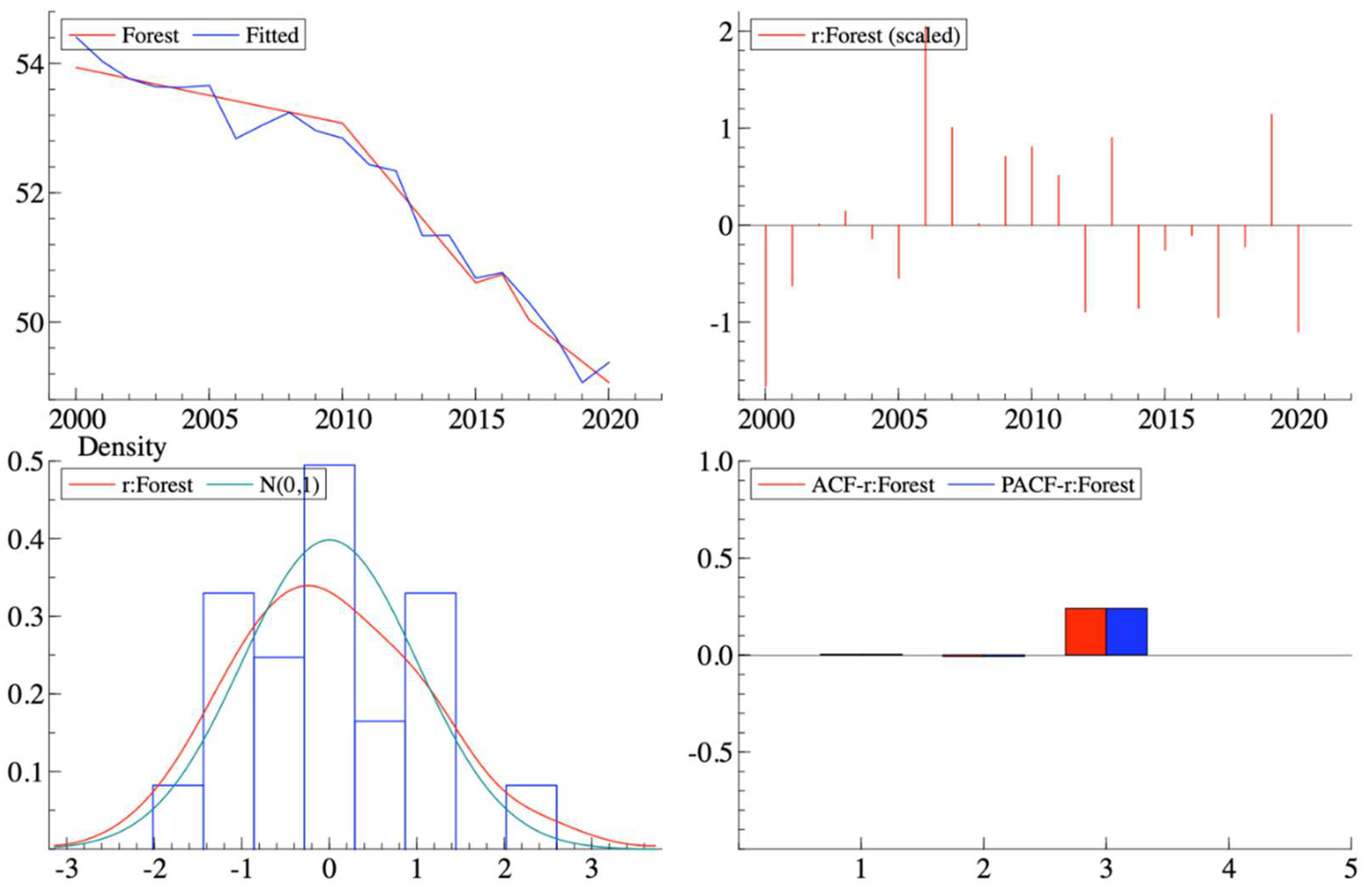

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

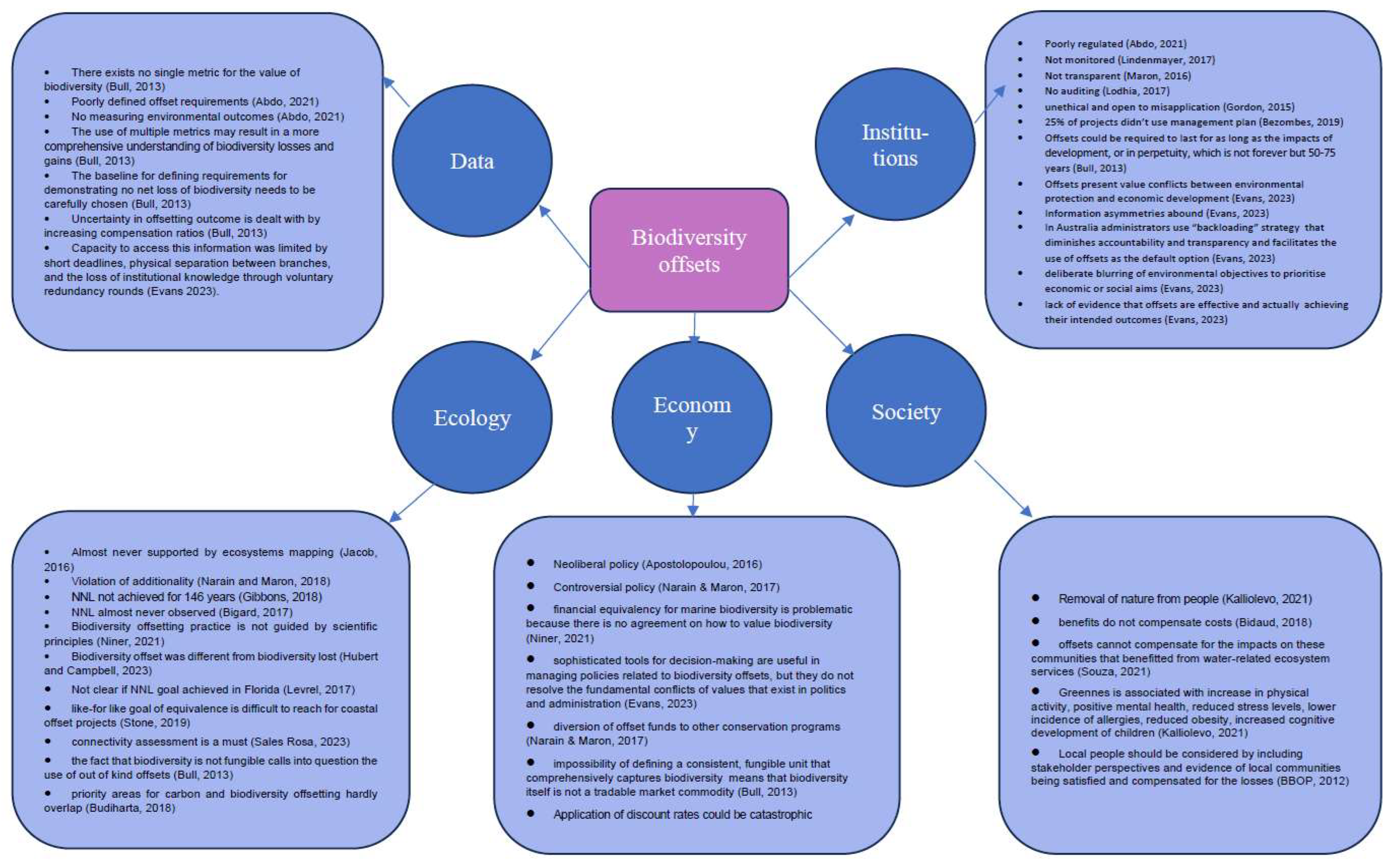

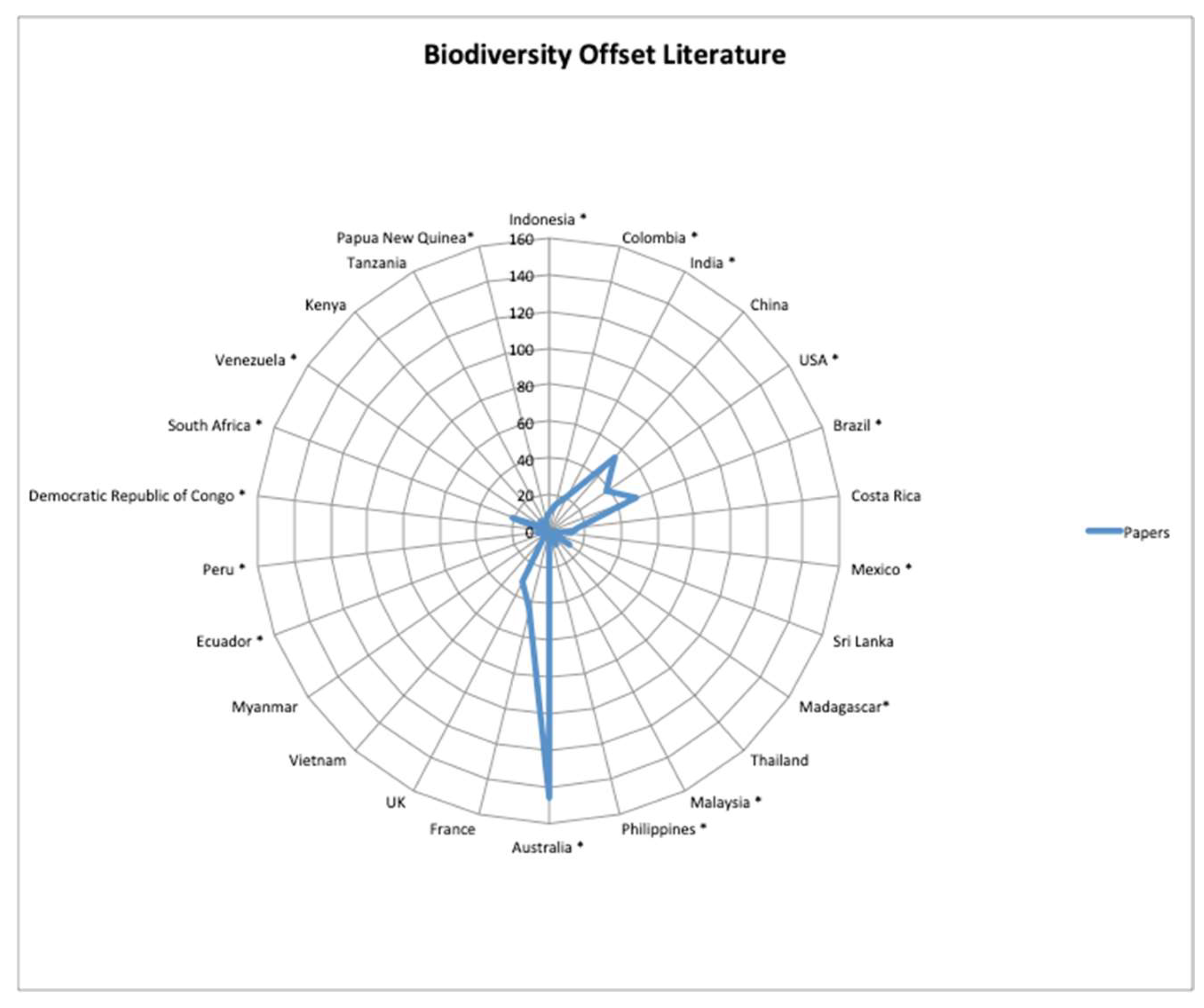

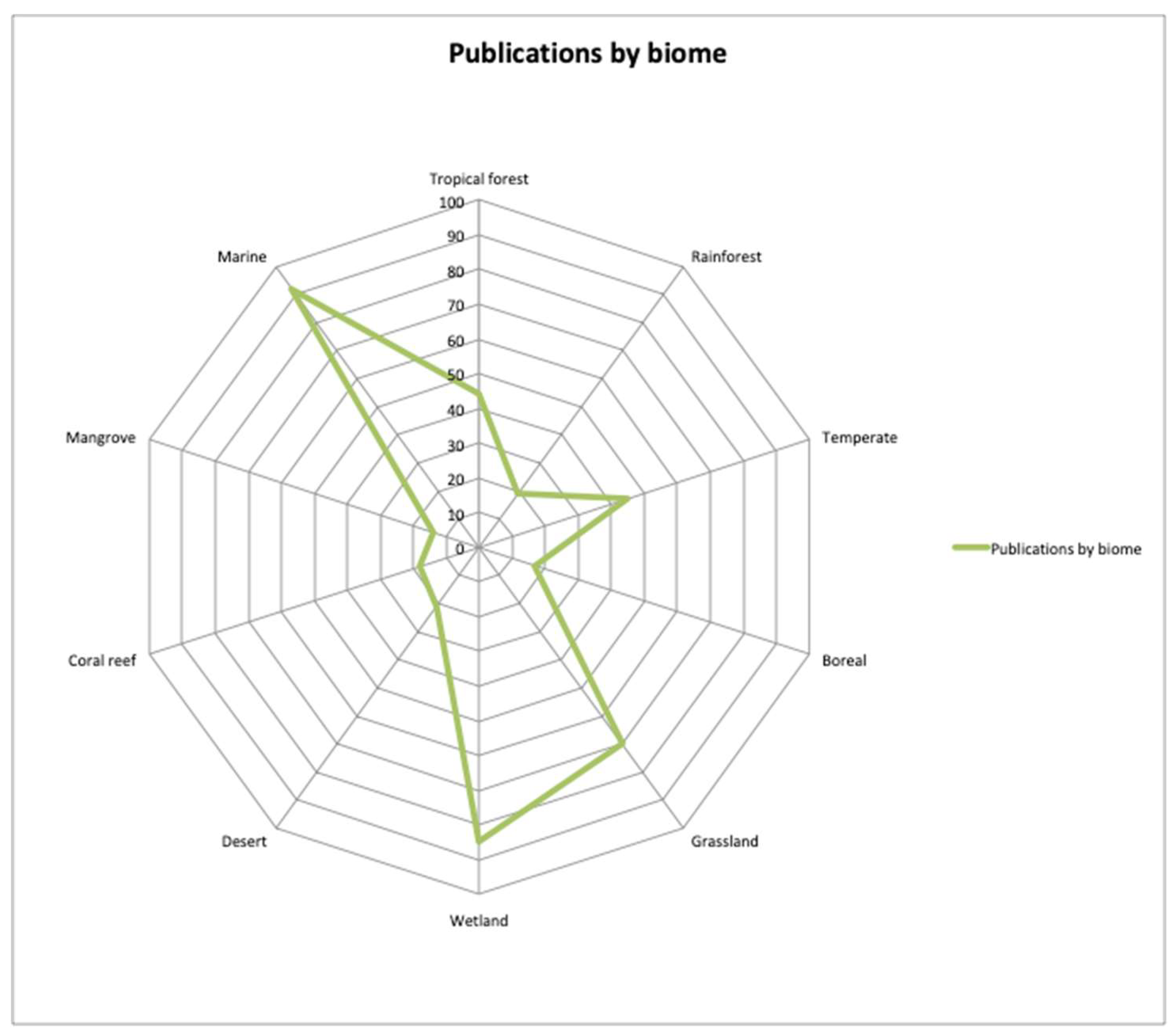

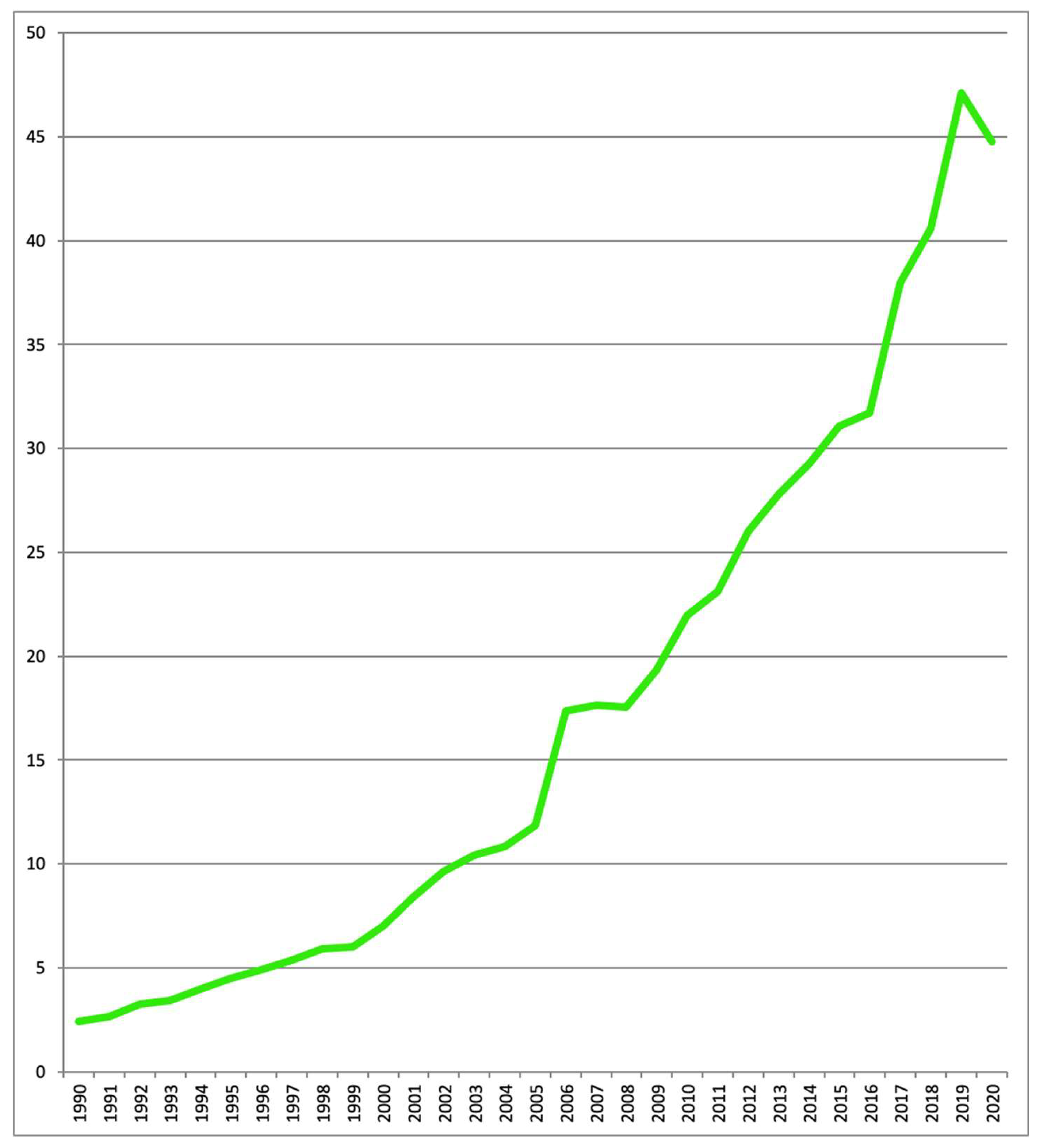

2. Literature Review

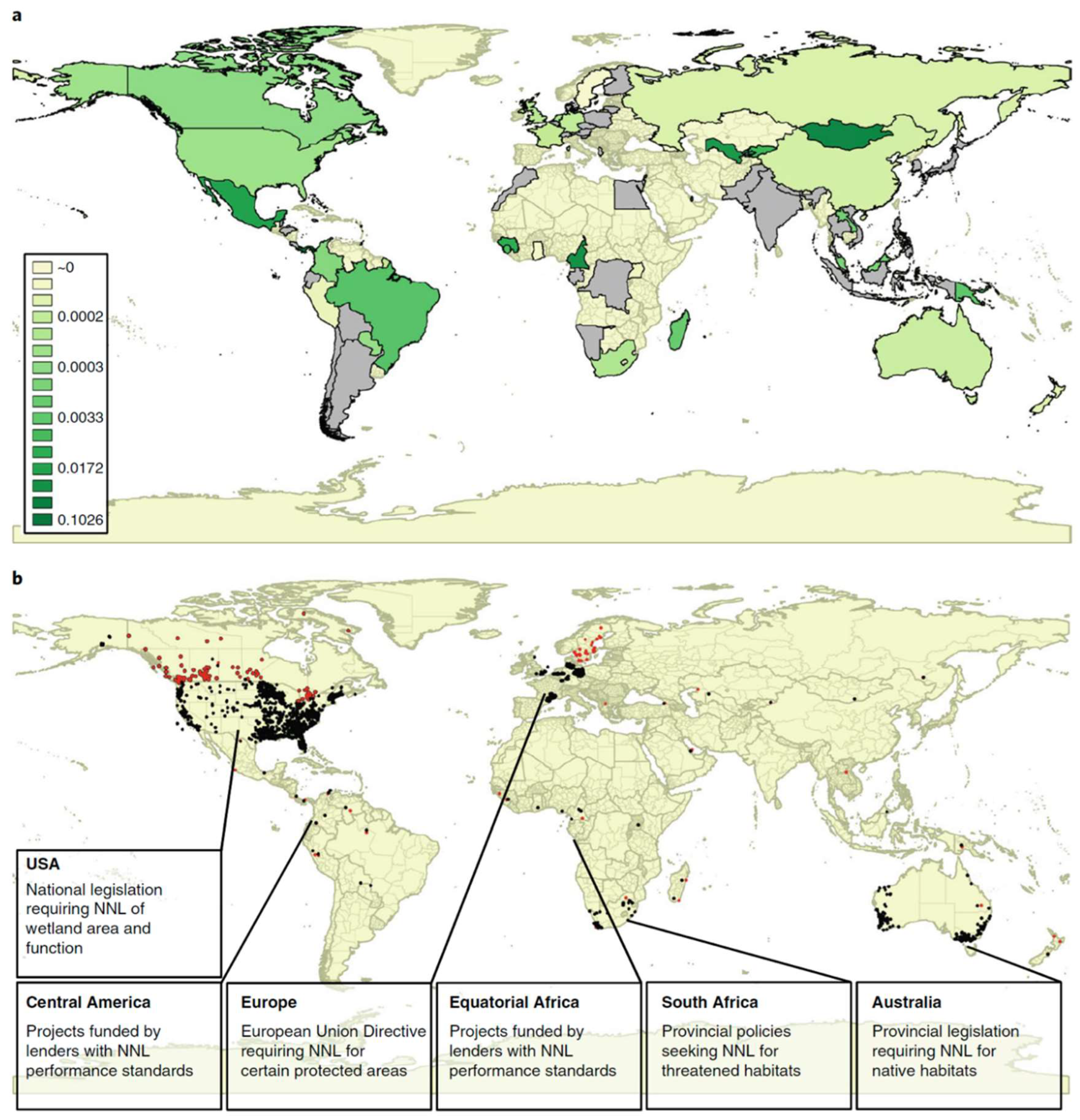

Institutions

Data

Ecology

Economics

Society

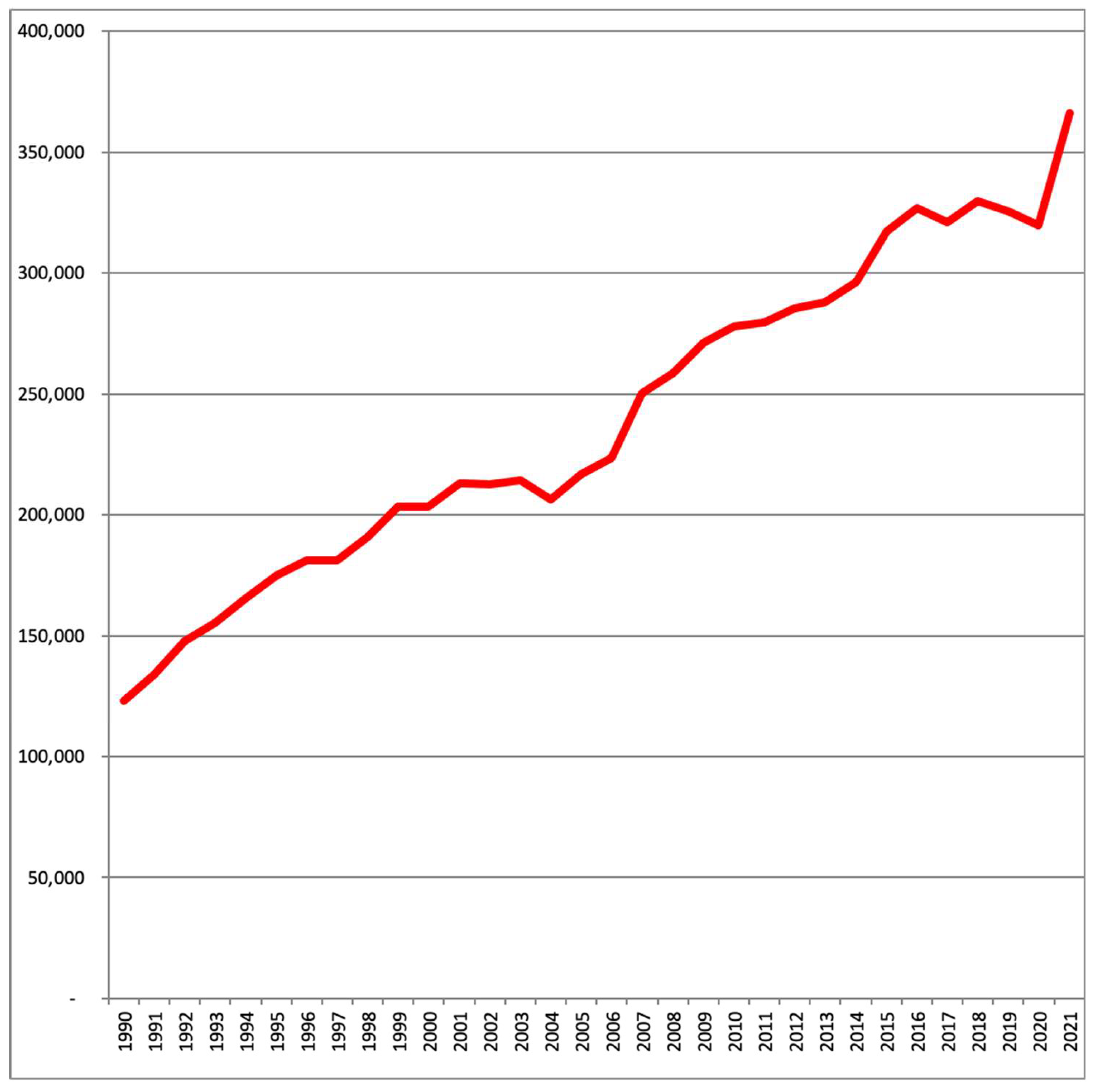

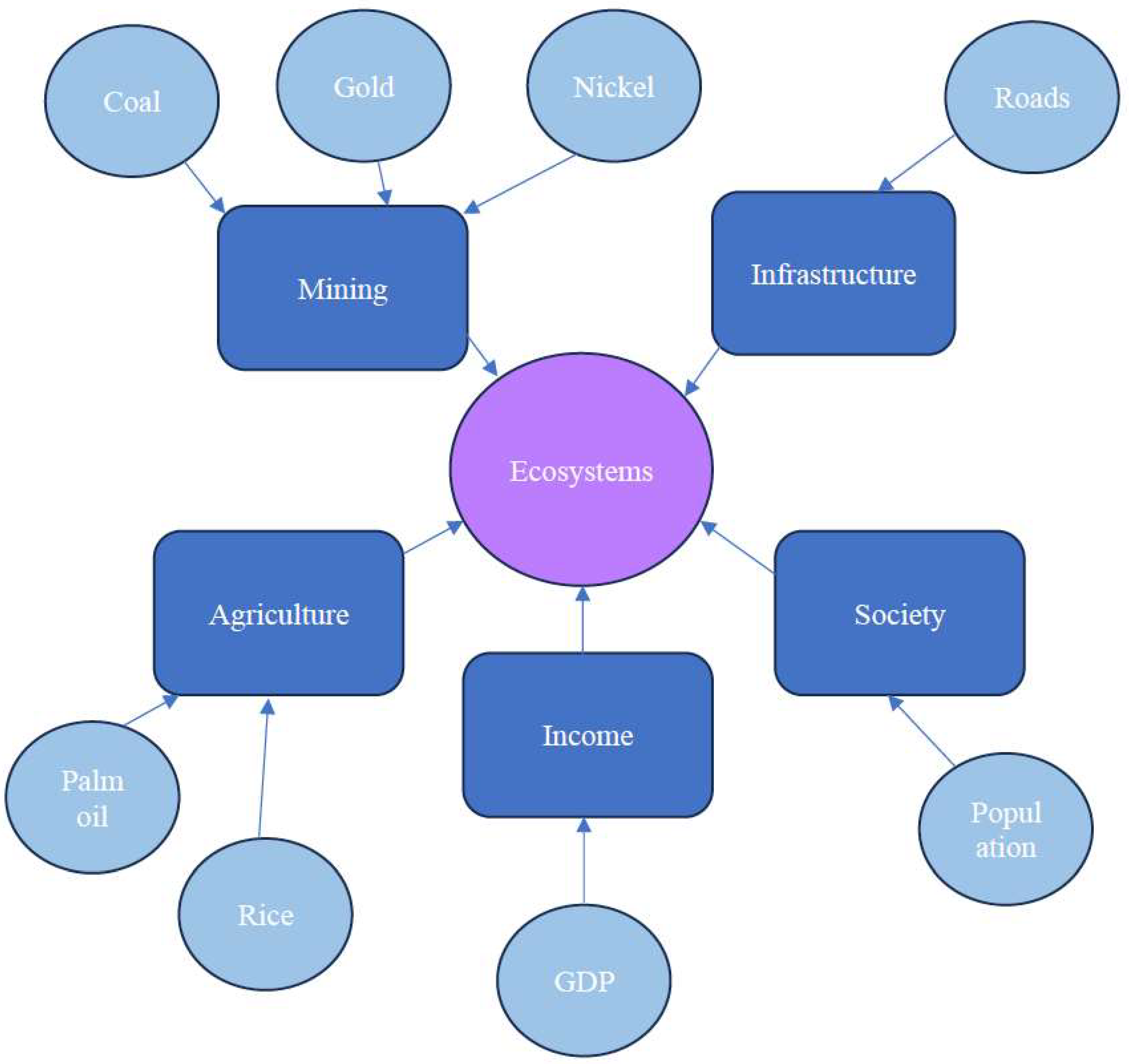

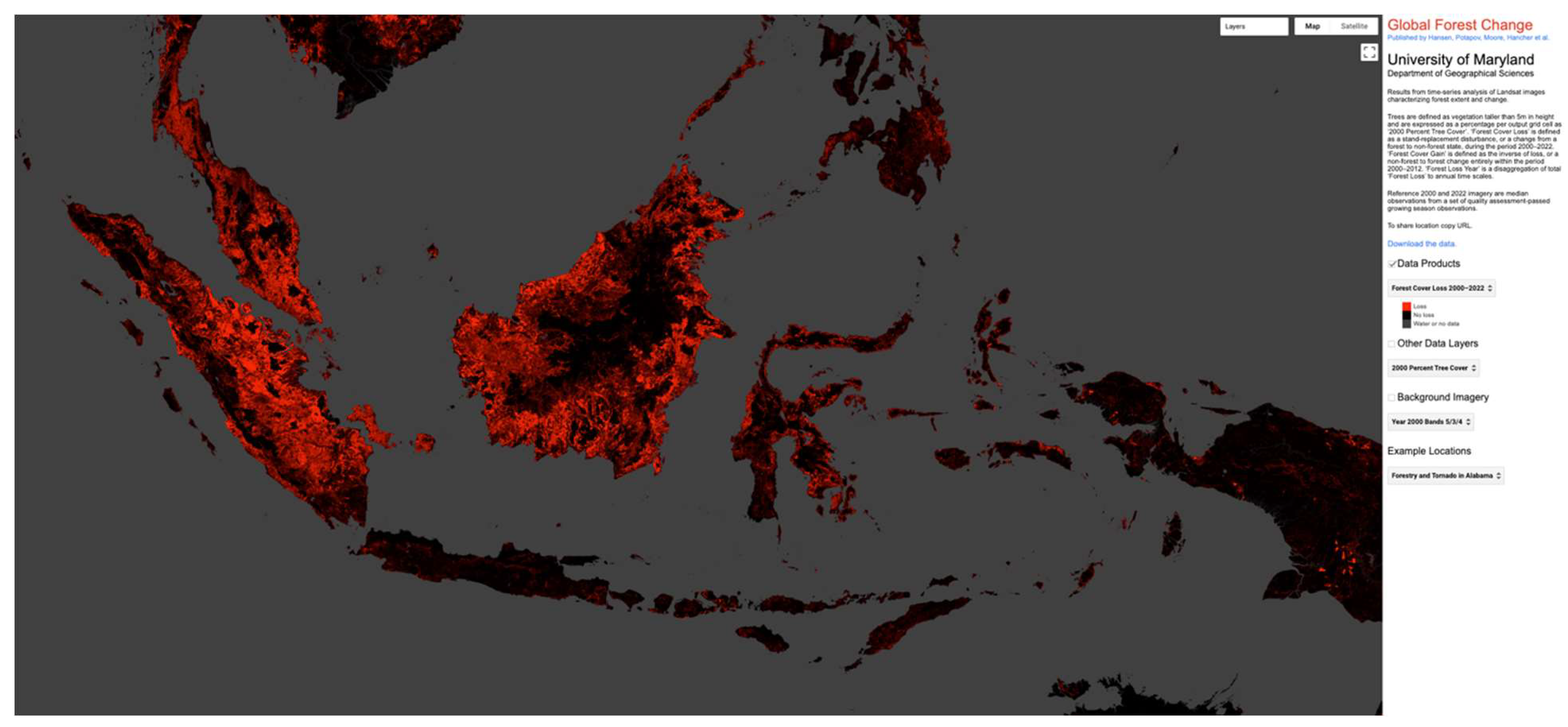

3. Analysis of the State of the Environment in Indonesia

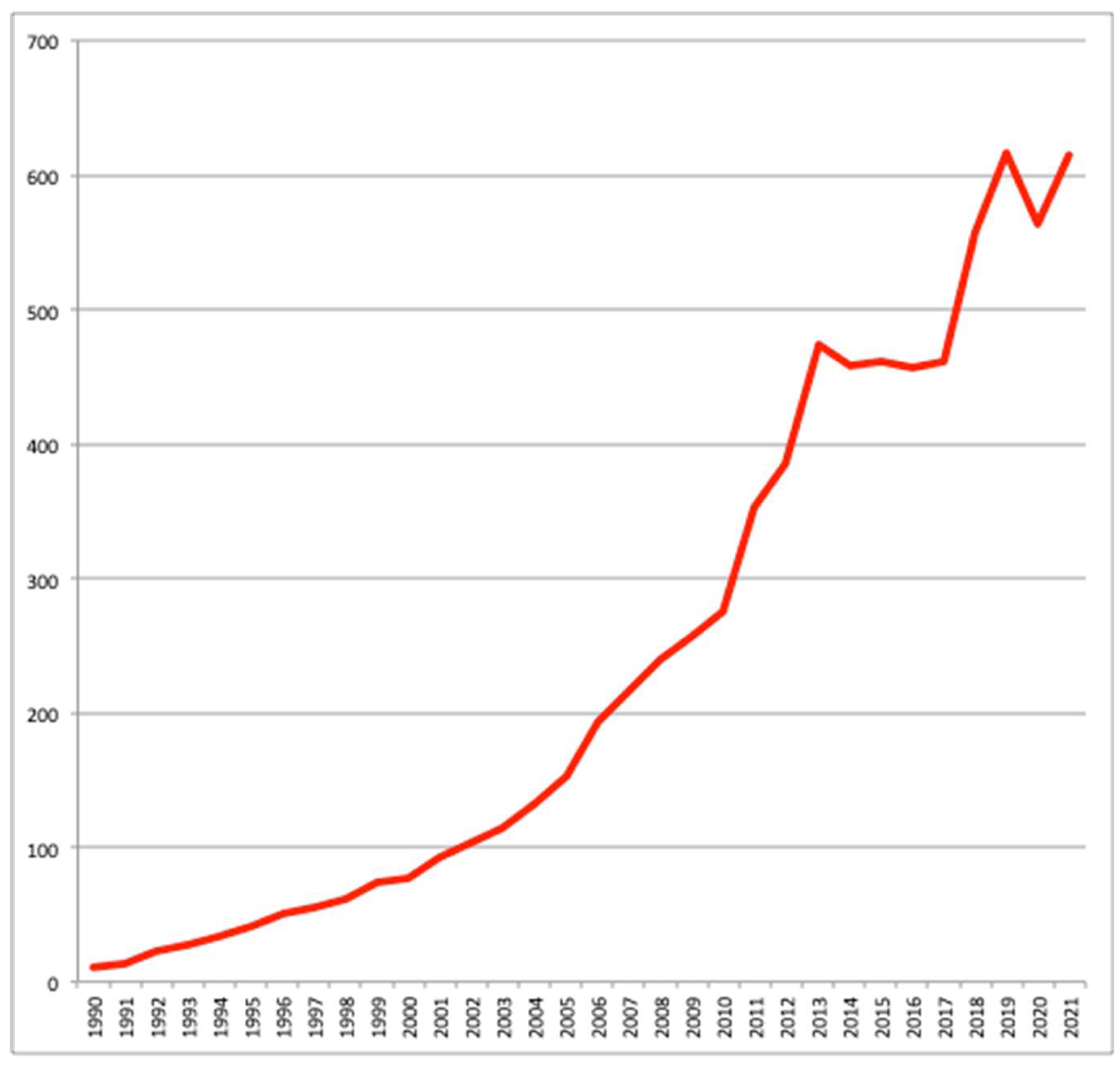

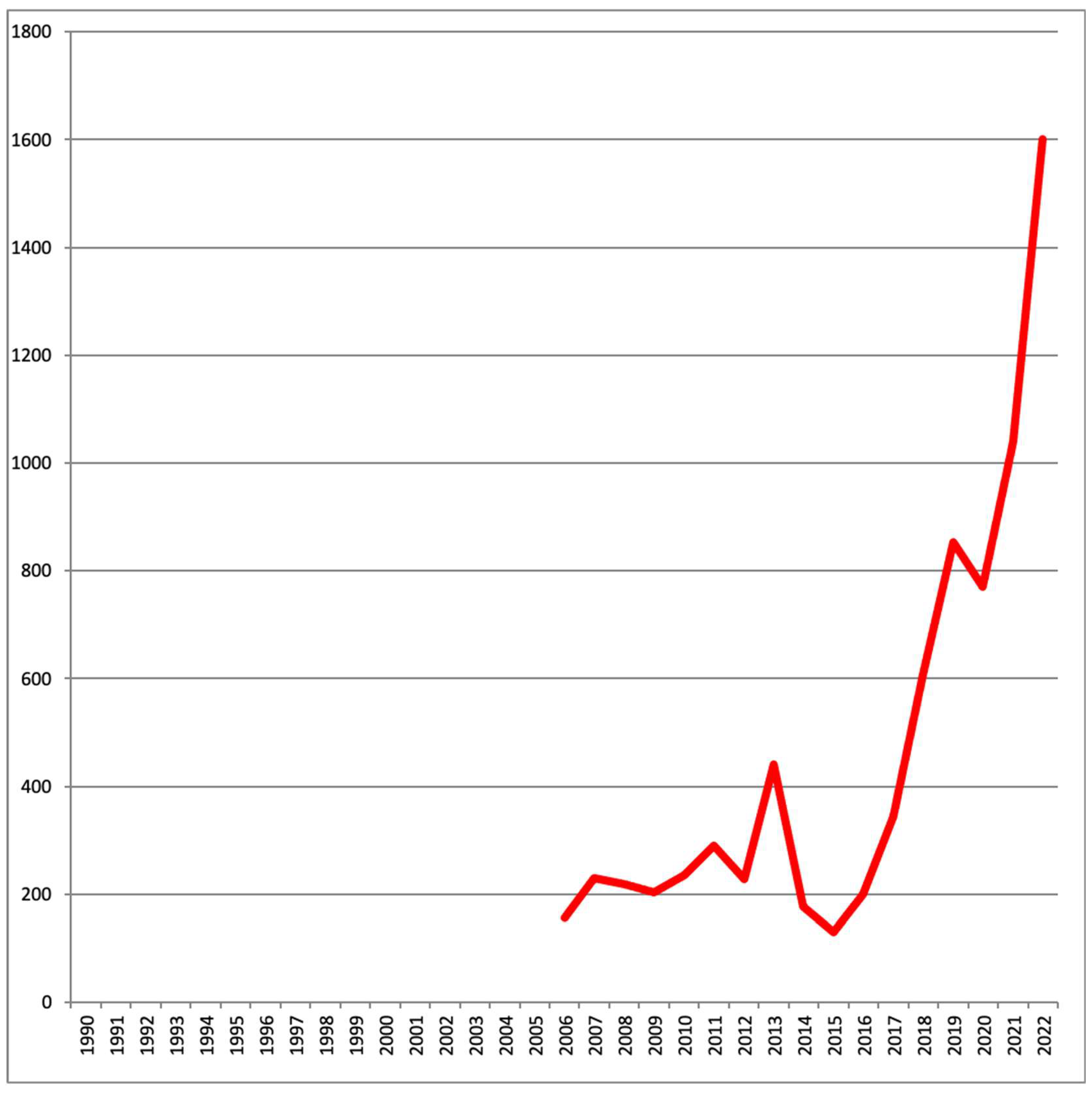

Mining

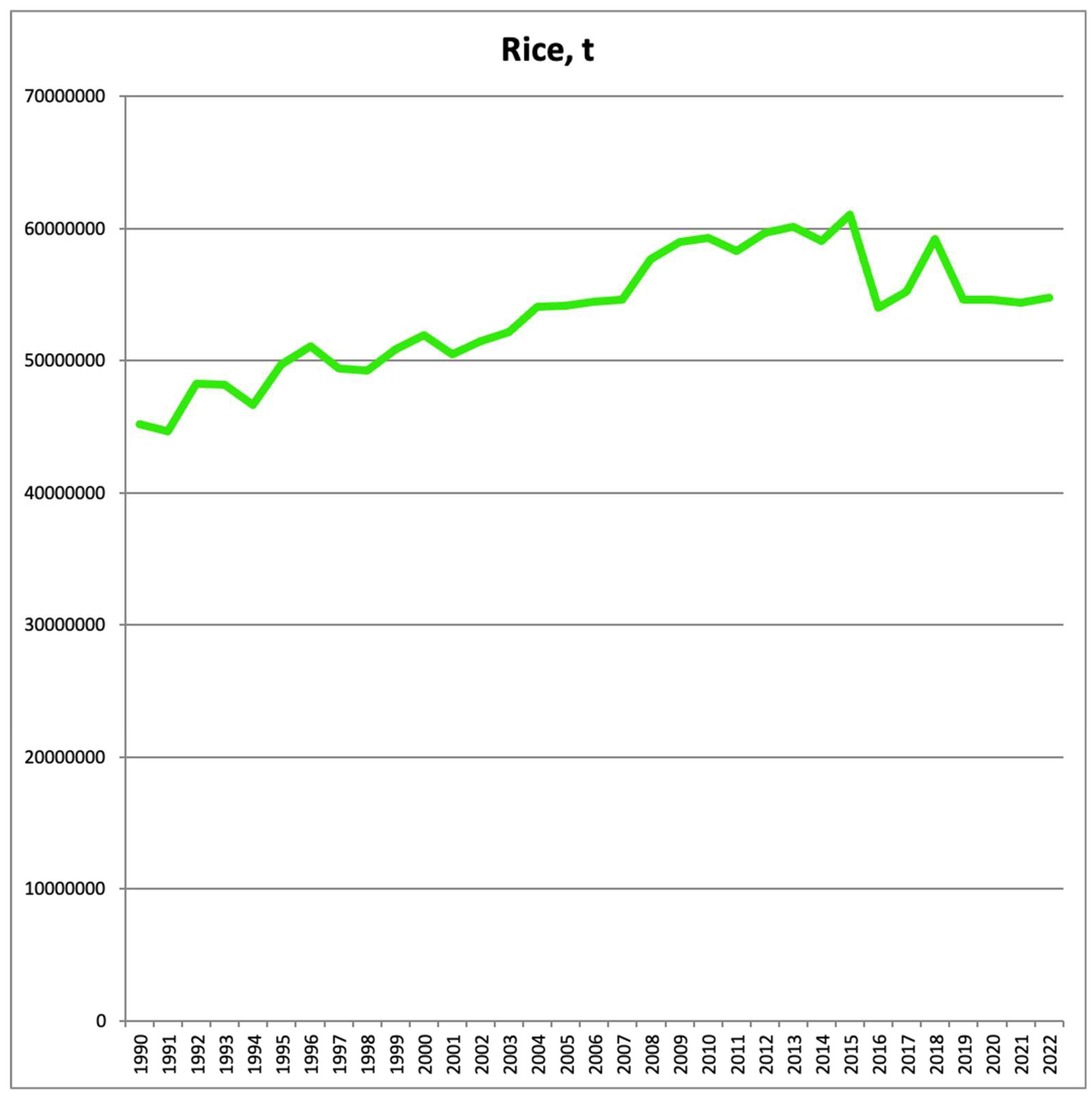

Agriculture

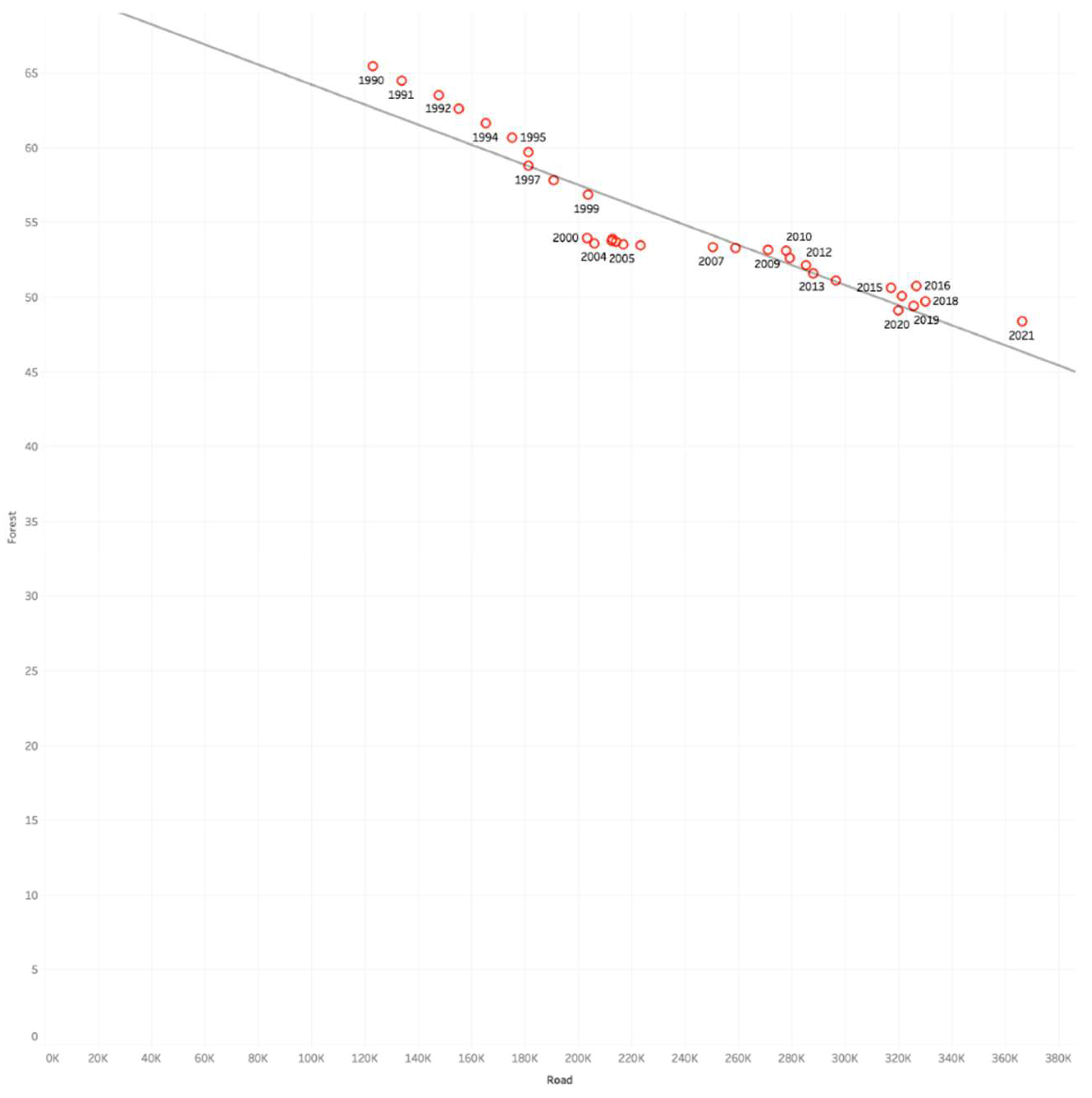

Infrastructure

Transport

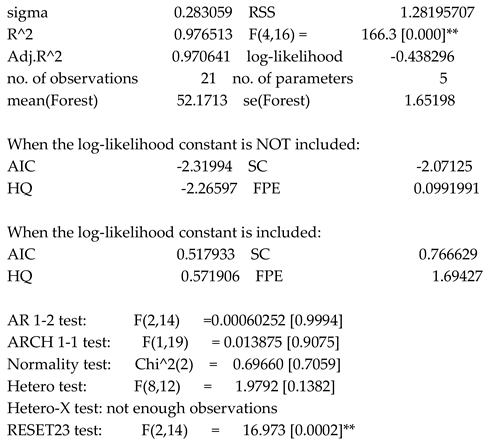

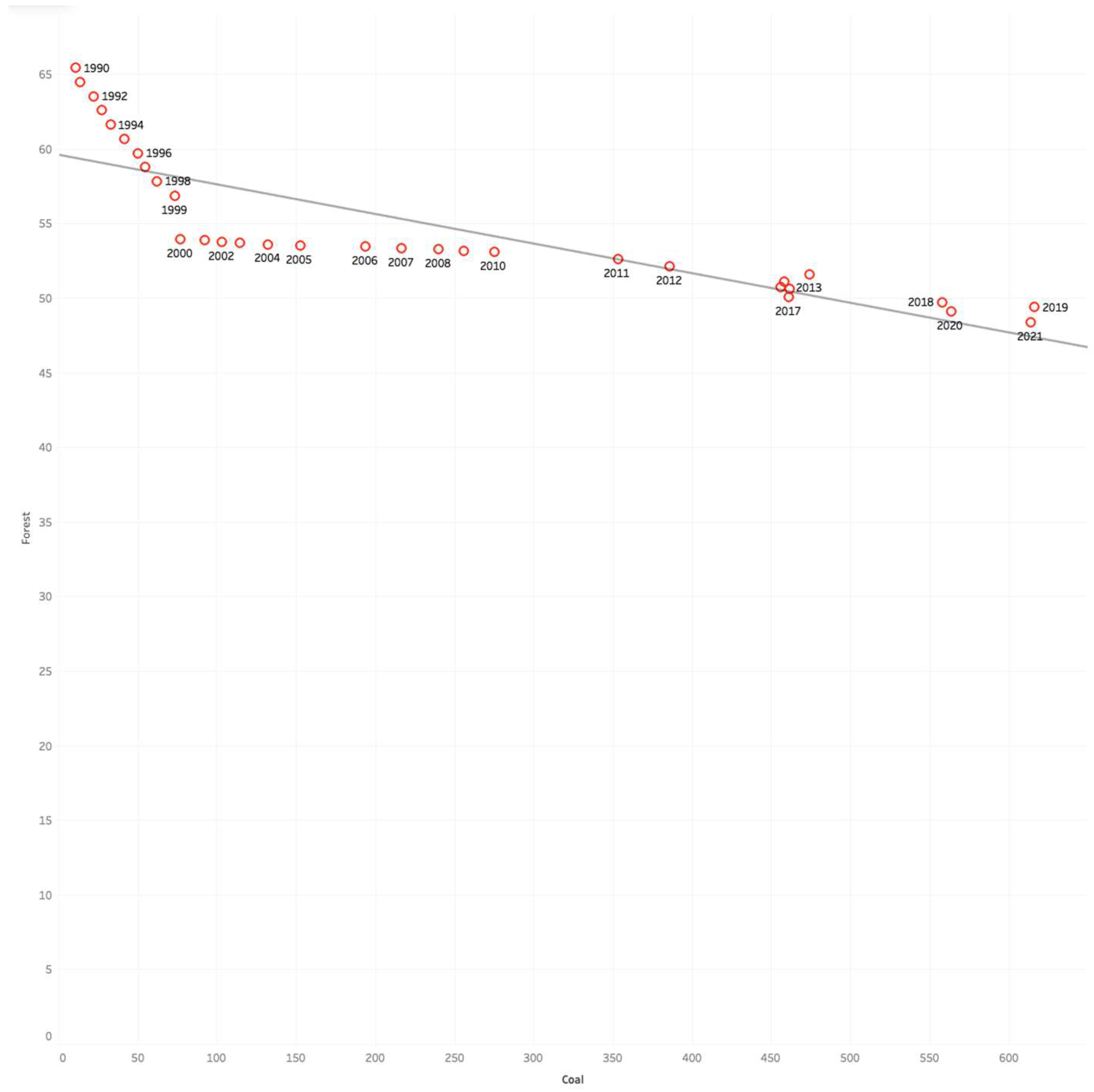

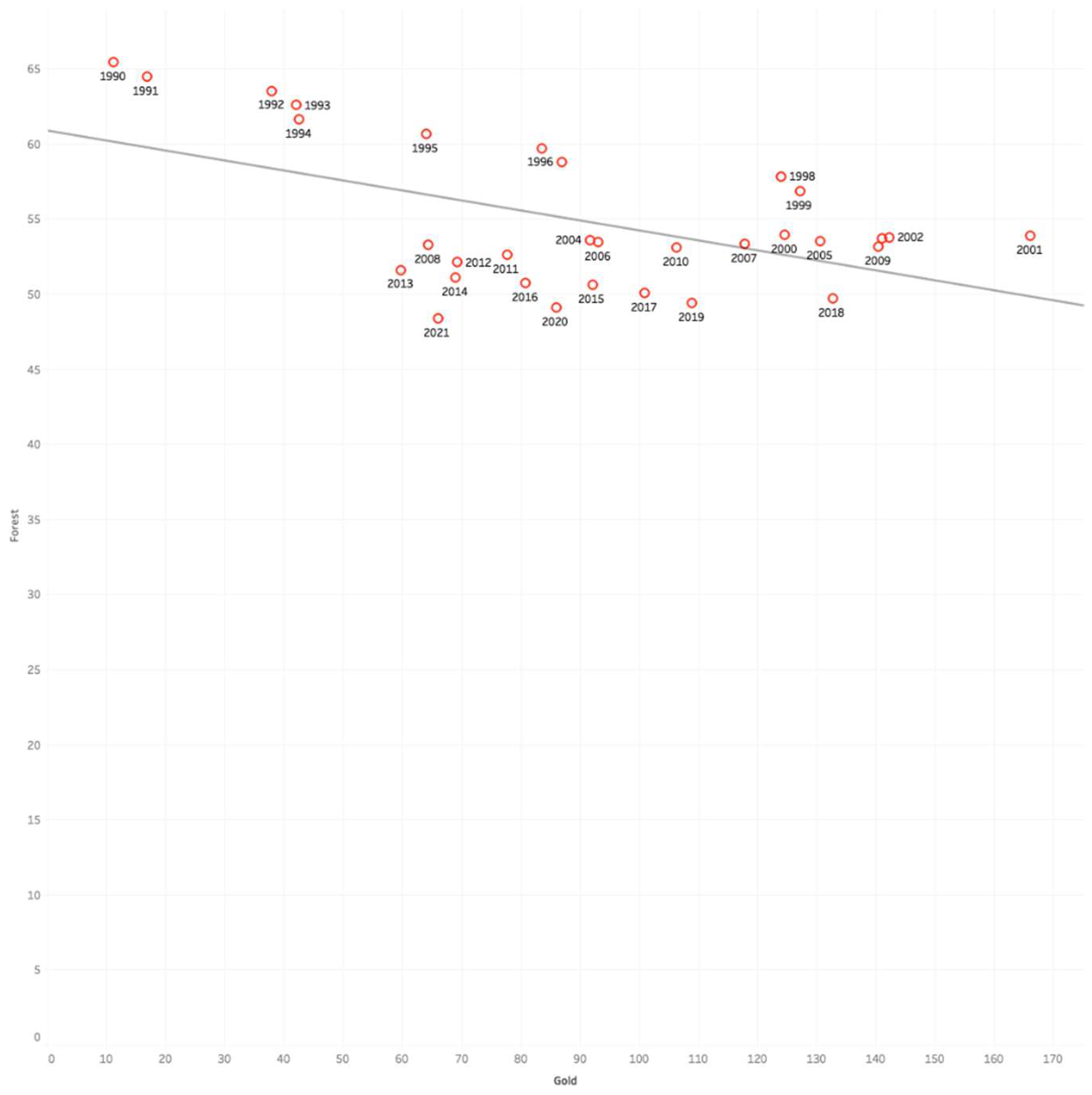

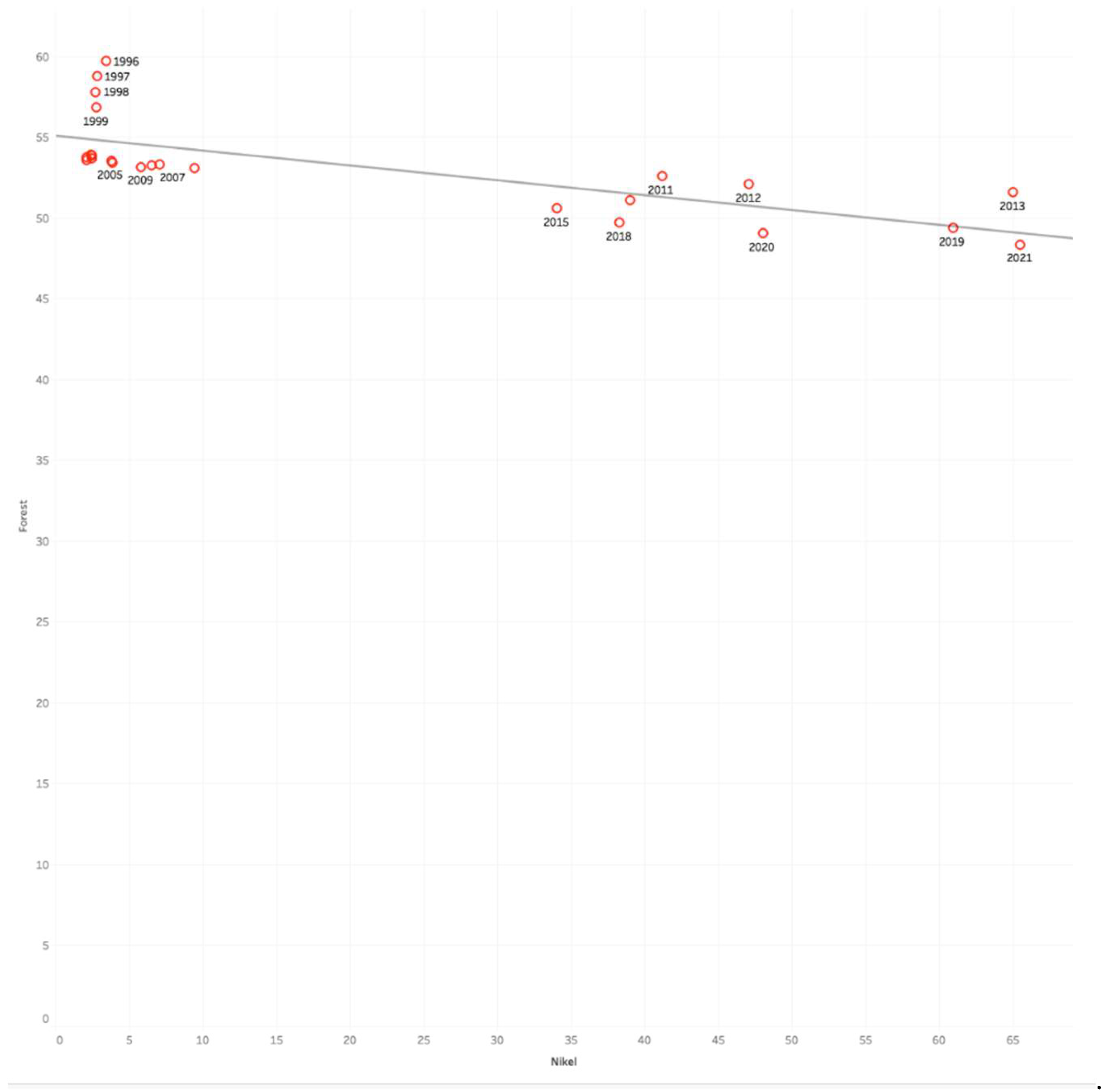

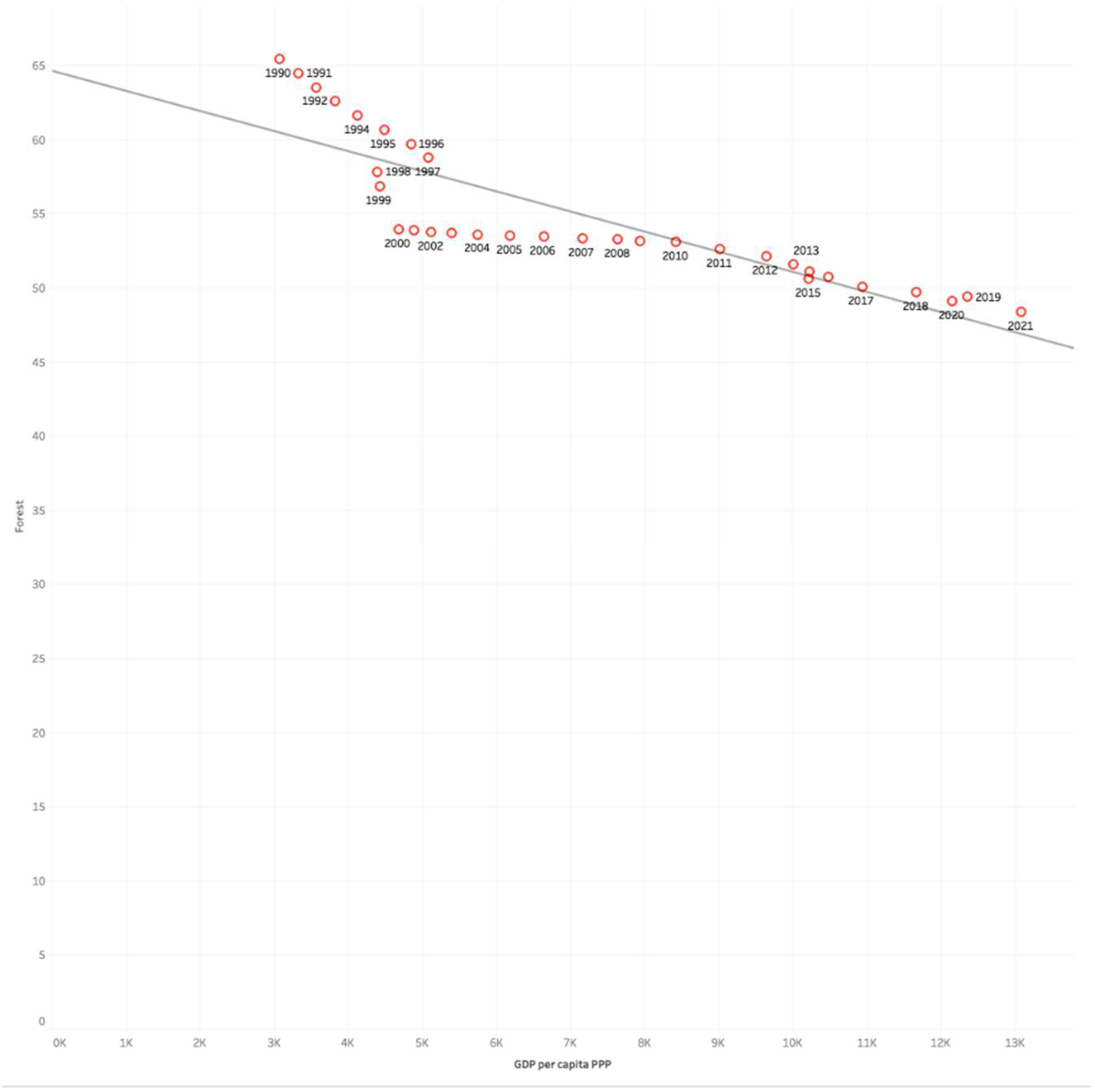

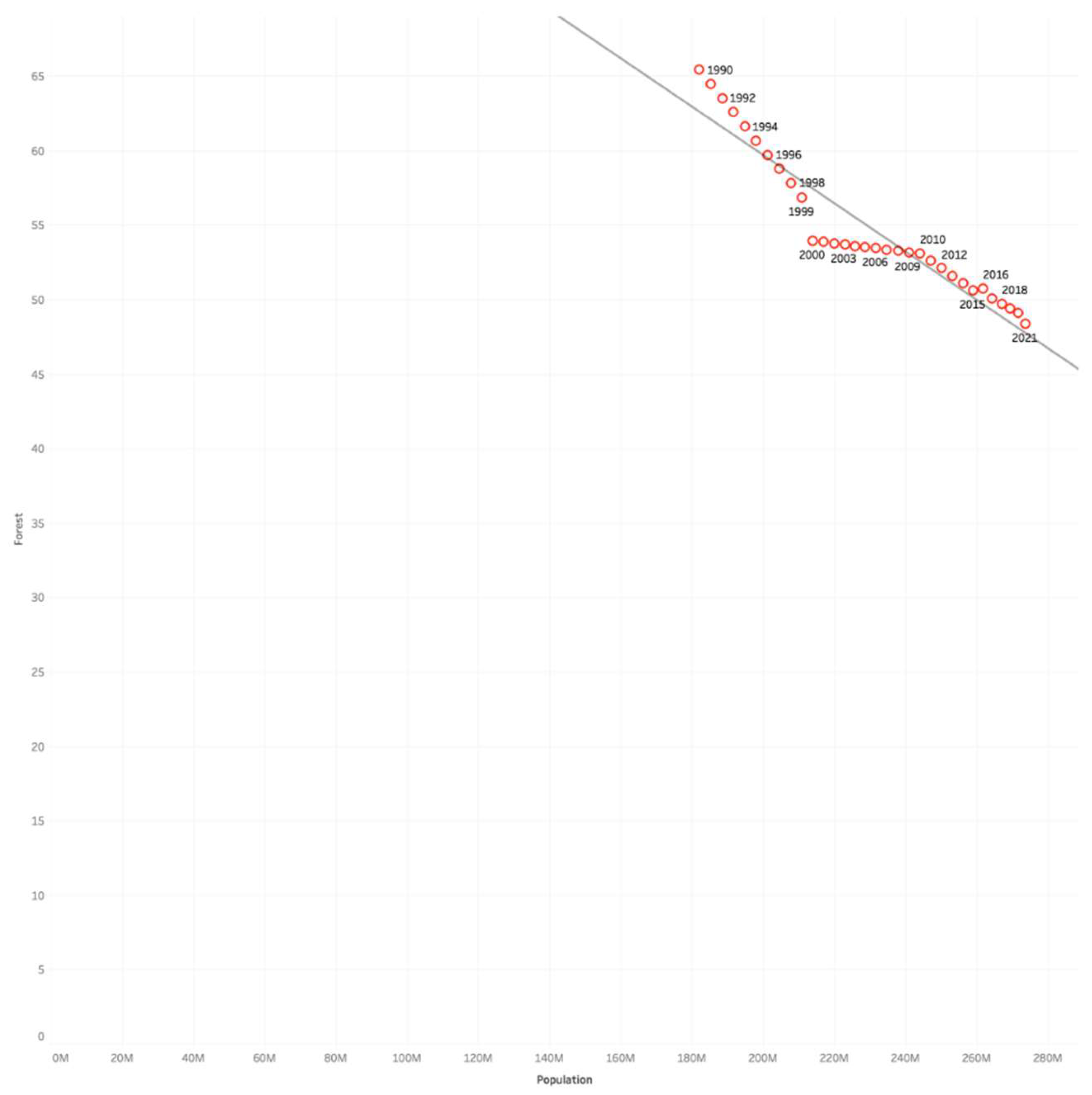

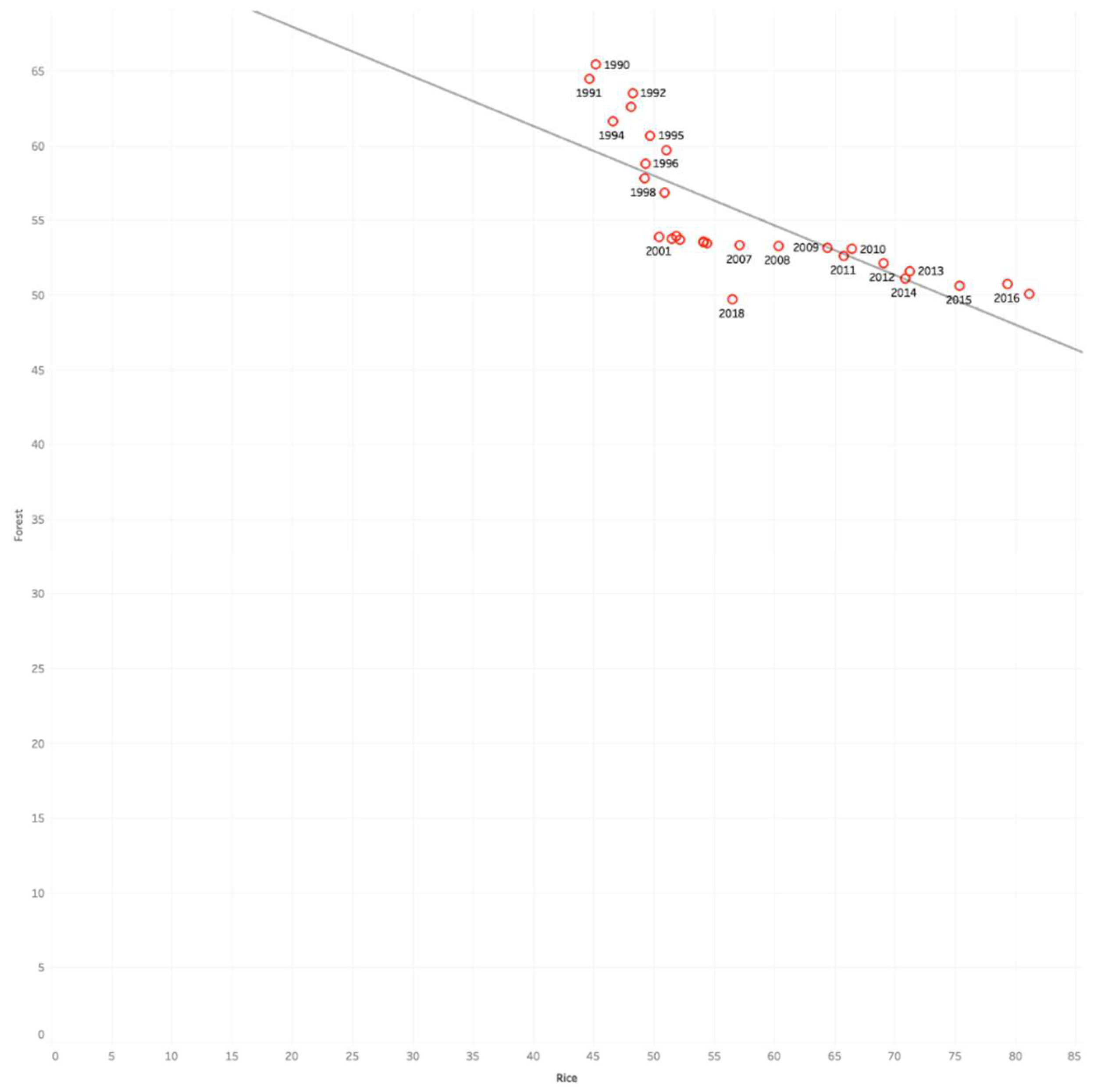

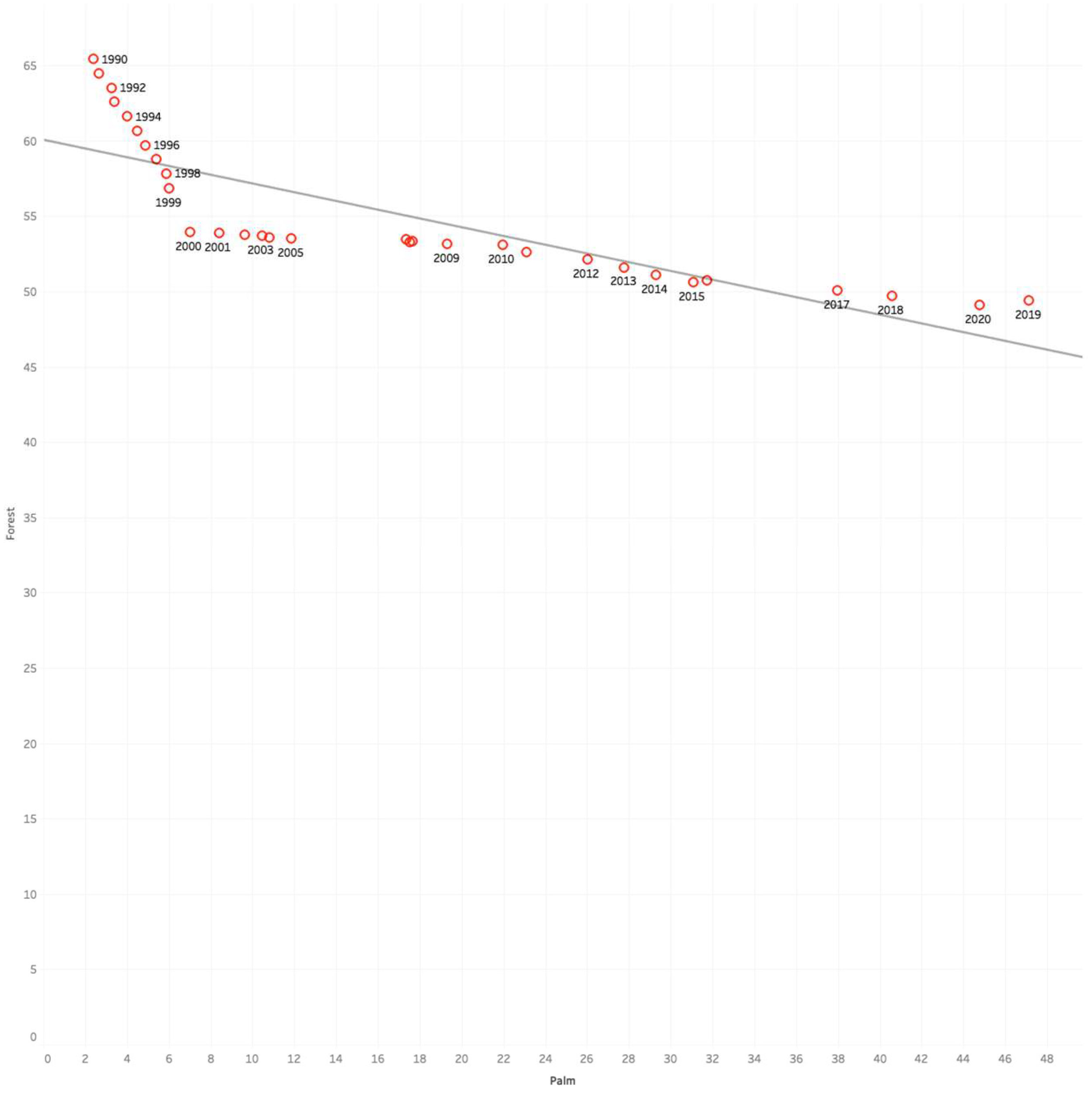

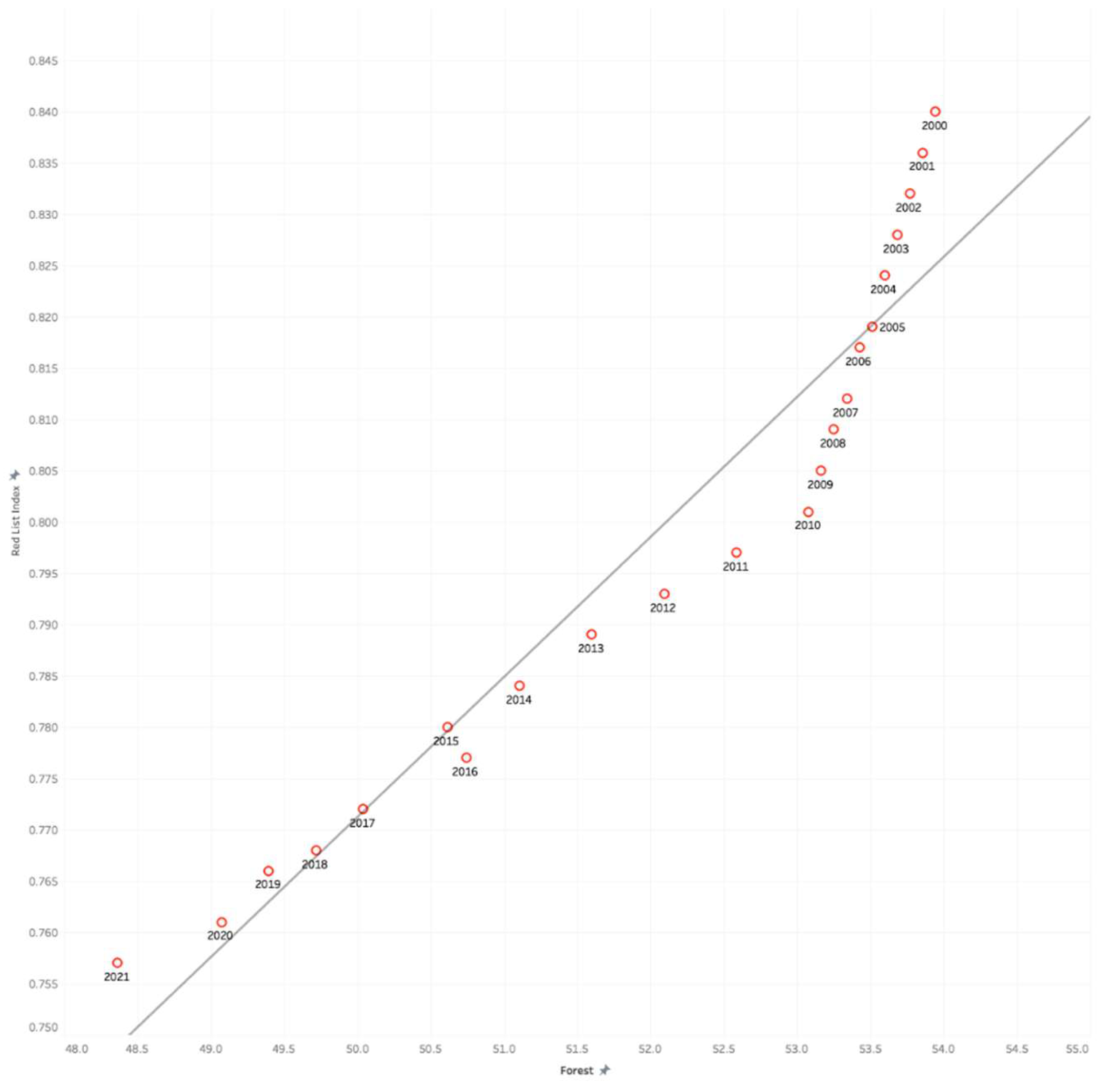

4. Multi-Factor Econometric Model of Ecosystem Deterioration in Indonesia

| Box 1. |

|

5. Discussion

- Acknowledge Indonesia’s Global Significance for Biodiversity: Indonesia is one of the most important biodiversity hubs globally, and preserving its ecosystems must be a national and international priority.

- Address the Drivers of Deforestation: Palm oil production, coal mining, and population pressures have been major contributors to forest loss. Effective policies to curb these pressures are urgently needed to reverse the trend of deforestation.

- Implement Comprehensive Ecosystem Services Mapping: Conduct nationwide mapping of ecosystem services at a resolution of 1x1 km or finer to identify critical biodiversity hotspots.

- Protect High-Value Areas: Exclude the top 25% of areas with the highest multidimensional biodiversity value from all economic and infrastructure development activities.

- Redefine the Economic Framework: Adopt a framework of ecological economics, placing the economic system firmly within environmental boundaries. Recognize ecosystems as holistic systems with intrinsic and instrumental value.

- Foster Transparency and Accountability: Establish robust monitoring systems in collaboration with Indonesia’s Statistical Office, Geospatial Information Agency, and Space Agency to ensure transparency and long-term tracking of biodiversity offset outcomes.

- Develop Centers of Green Economic Growth: Focus on low-resource, high-value industries such as software development, education, health, eco-tourism, and financial services. Actively pursue ecosystem restoration and regeneration alongside economic development.

- Strengthen Research and Capacity Building: Expand research centers focused on satellite imagery and ecosystem modeling, fostering local expertise in sustainable development and ecological management.

- Position Indonesia as a Global Conservation Leader: By adopting an innovative, data-driven approach, Indonesia can lead mega-diverse nations in developing conservation strategies that align with global biodiversity goals.

6. Conclusions.

Acknowledgments

Glossary

- Biodiversity

- CBD Kunming Montreal Biodiversity Framework

- Ecosystem

- Ecosystem services

- Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services

- Environmental Impact Assessment

- Mitigation hierarchy

- Multi-criteria decision aid

- Econometrics

- ELECTRE TRI

- PRISMA

- No Net Loss

- Net Positive Impact

Nature-based Solutions

ANNEX 1

References

- Abdo, L., Griffin, S., Kemp, A., & Coupland, G. (2021). Disparity in biodiversity offset regulation across Australia may reduce effectiveness. Australasian Journal of Environmental Management, 28(2), 81–103. [CrossRef]

- ADB. (2020). Biodiversity Offset Management Plan. INO: Sarulla Geothermal Power Generation Project. ADB. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/42916/42916-014-dpta-en_9.pdf.

- Akhlas, A. W. (2020a, October 9). Environmental concerns, protests may discourage foreign investment: Moody’s. Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/10/09/environmental-concerns-protests-may-discourage-foreign-investment-moodys.html.

- Akhlas, A. W. (2020b, October 22). IMF Concered over Jobs Law Environment Rules. Jakarta Post. https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2020/10/21/imf-concerned-over-jobs-law-environment-rules.html.

- Alagood, R. K. (2016). Mythology of Mitigation Banking. Environmental Law Reporter, Vol. 46. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2737694.

- Alamgir, M., Campbell, M. J., Sloan, S., Suhardiman, A., Supriatna, J., & Laurance, W. F. (2019). High-risk infrastructure projects pose imminent threats to forests in Indonesian Borneo. Scientific Reports, 9(1). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghobari, H., & Dewidar, A. Z. (2021). Integrating GIS-Based MCDA Techniques and the SCS-CN Method for Identifying Potential Zones for Rainwater Harvesting in a Semi-Arid Area. Water, 13(5), 704. [CrossRef]

- Ampri, I., Falconer, A., Wahyudi, N., Rosenberg, A., Ampera, M. B., Tuwo, A., Glenday, S., & Wilkinson, J. (2014). The Landscape of Public Climate Finance in Indonesia. An Indonesian Ministry of Finance & CPI. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/The-Landscape-of-Public-Finance-in-Indonesia.pdf.

- Anderson, Z. R., Kusters, K., McCarthy, J., & Obidzinski, K. (2016). Green growth rhetoric versus reality: Insights from Indonesia. Global Environmental Change, 38, 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Anonymous. (2020). The United Nations must get its new biodiversity targets right. Nature, 578(7795), 337–338. [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulou, E. (2016). Biodiversity offsetting in England: Governance rescaling, socio-spatial injustices, and the \hack\break neoliberalization of nature. Web Ecology, 16(1), 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Asih, A. S., Zamroni, A., Alwi, W., Sagala, S. T., & Putra, A. S. (2022). Assessment of Heavy Metal Concentrations in Seawater in the Coastal Areas around Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia. Iraqi Geological Journal, 55(1B), 14–22. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Flores, Juárez-Mancilla, Hinojosa-Arango, Cruz-Chávez, López-Vivas, & Arizpe-Covarrubias. (2020). A Practical Index to Estimate Mangrove Conservation Status: The Forests from La Paz Bay, Mexico as a Case Study. Sustainability, 12(3), 858. [CrossRef]

- Bakirman, T., & Gumusay, M. U. (2020). A novel GIS-MCDA-based spatial habitat suitability model for Posidonia oceanica in the Mediterranean. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 192(4), 231. [CrossRef]

- Balling, J., Verbesselt, J., De Sy, V., Herold, M., & Reiche, J. (2021). Exploring Archetypes of Tropical Fire-Related Forest Disturbances Based on Dense Optical and Radar Satellite Data and Active Fire Alerts. Forests, 12(4), 456. [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, R. (2019). Visioning Futures: Improving infrastructure planning to harness nature’s benefits in a warming world. WWF. https://files.worldwildlife.org/wwfcmsprod/files/Publication/file/3ntj8trz40_WWF_Visioning_Futures_2020_lo_res.pdf?_ga=2.187021992.1692908604.1708095626-1062575565.1708095624.

- BBOP. (2012). Guidance Notes to the Standard on Biodiversity Offsets. Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme. https://www.forest-trends.org/wp-content/uploads/imported/BBOP_Standard_Guidance_Notes_20_Mar_2012_Final_WEB.pdf.

- Benayas, J. M. R., Newton, A. C., Diaz, A., & Bullock, J. M. (2009). Enhancement of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services by Ecological Restoration: A Meta-Analysis. Science, 325(5944), 1121–1124. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N. J., & Satterfield, T. (2018). Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conservation Letters, 11(6), e12600. [CrossRef]

- Bezombes, L., Kerbiriou, C., & Spiegelberger, T. (2019). Do biodiversity offsets achieve No Net Loss? An evaluation of offsets in a French department. Biological Conservation, 231, 24–29. [CrossRef]

- Bidaud, C., Schreckenberg, K., & Jones, J. P. G. (2018). The local costs of biodiversity offsets: Comparing standards, policy and practice. Land Use Policy, 77, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Bigard, C., Pioch, S., & Thompson, J. D. (2017). The inclusion of biodiversity in environmental impact assessment: Policy-related progress limited by gaps and semantic confusion. Journal of Environmental Management, 200, 35–45. [CrossRef]

- Blomkamp, E., Sholikin, M. N., Nursyamsi, F., Lewis, J. M., & Toumbourou, T. (2018). Understanding Policymaking in Indonesia: In Search of a Policy Cycle. University of Melbourne and Indonesian Centre for Law and Policy Studies. https://www.ksi-indonesia.org/file_upload/Understanding-Policy-Making-in-Indonesia-in-Searc-06Feb2018141656.pdf.

- Boentoro, M. R. B., & Wherrett, T. (2021). Limits of acceptable change for sustainable management of the Pelawan Biodiversity Park, Bangka Belitung Islands. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 913(1). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Borgert, T., Donovan, J. D., Topple, C., & Masli, E. K. (2019). Determining what is important for sustainability: Scoping processes of sustainability assessments. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 37(1), 33–47. [CrossRef]

- Brears, R. (2022). Financing nature-based solutions: Exploring public, private, and blended finance models and case studies. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brockhaus, M., Obidzinski, K., Dermawan, A., Laumonier, Y., & Luttrell, C. (2012). An overview of forest and land allocation policies in Indonesia: Is the current framework sufficient to meet the needs of REDD+? Forest Policy and Economics, 18, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Brondízio, E. S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., & Ngo, H. T. (Eds.). (2019). The global assessment report of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

- Budiharta, S., Meijaard, E., Gaveau, D. L. A., Struebig, M. J., Wilting, A., Kramer-Schadt, S., Niedballa, J., Raes, N., Maron, M., & Wilson, K. A. (2018). Restoration to offset the impacts of developments at a landscape scale reveals opportunities, challenges and tough choices. Global Environmental Change, 52, 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Bull, J. W., Gordon, A., Milner-Gulland, E. J., Singh, N. J., & Suttle, K. B. (2013). Biodiversity offsets in theory and practice. Oryx, 47(3), 369–380. Cambridge Core. [CrossRef]

- Bull, J. W., & Strange, N. (2018). The global extent of biodiversity offset implementation under no net loss policies. Nature Sustainability, 1(12), 790–798. [CrossRef]

- Cabernard, L., & Pfister, S. (2022). Hotspots of Mining-Related Biodiversity Loss in Global Supply Chains and the Potential for Reduction through Renewable Electricity. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(22), 16357–16368. [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Secretariat of the Republic of Indonesia. (2019). Government Establishes Environment Fund Management Agency. https://setkab.go.id/en/govt-establishes-environmental-fund-management-agency/.

- Cammerino, A. R. B., Ingaramo, M., Piacquadio, L., & Monteleone, M. (2023). Assessing and Mapping Forest Functions through a GIS-Based, Multi-Criteria Approach as a Participative Planning Tool: An Application Analysis. Forests, 14(5), 934. [CrossRef]

- Carreras Gamarra, M. J., & Toombs, T. P. (2017). Thirty years of species conservation banking in the U.S.: Comparing policy to practice. Biological Conservation, 214, 6–12. [CrossRef]

- Castilhos, Z. C., Rodrigues-Filho, S., Rodrigues, A. P. C., Villas-Bôas, R. C., Siegel, S., Veiga, M. M., & Beinhoff, C. (2006). Mercury contamination in fish from gold mining areas in Indonesia and human health risk assessment. Selected Papers from the 7th International Conference on Mercury as a Global Pollutant, Ljubljana, Slovenia June 27 - July 2, 2004, 368(1), 320–325. [CrossRef]

- CIFOR. (2024). Provincial Council on Climate Change East Kalimantan, Indonesia. https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/flyer/7434-Flyer.pdf.

- Damastuti, E., & De Groot, R. (2019). Participatory ecosystem service mapping to enhance community-based mangrove rehabilitation and management in Demak, Indonesia. Regional Environmental Change, 19(1), 65–78. [CrossRef]

- Darbi, M. (2020). Biodiversity Offsets Between Regulation and Voluntary Commitment: A Typology of Approaches Towards Environmental Compensation and No Net Loss of Biodiversity. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Darmadi, N. S., Bawono, B. T., & Hafidz, J. (2023). Forest Land Conversion for Oil Palm Plantations and Legal Protection and Social Welfare of Indigenous Communities. Environment and Ecology Research, 11(3), 467–474. [CrossRef]

- Darvill, R., & Lindo, Z. (2016). The inclusion of stakeholders and cultural ecosystem services in land management trade-off decisions using an ecosystem services approach. Landscape Ecology, 31(3), 533–545. [CrossRef]

- Demir, S., Demirel, Ö., & Okatan, A. (2021). An ecological restoration assessment integrating multi-criteria decision analysis with landscape sensitivity analysis for a hydroelectric power plant project: The Tokat-Niksar case. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 193(12), 818. [CrossRef]

- Department of Energy and Mineral Resources, East Kalimantan Province. (2024). Main Duties and Functions. https://esdm.kaltimprov.go.id/index.php/profil/dinas/tugas-pokok-dan-fungsi.

- Dhyani, S., Adhikari, D., Dasgupta, R., & Kadaverugu, R. (2023). Ecosystem and species habitat modeling for conservation and restoration. Springer.

- Duadji, N., Purba, D., Juliana, A., Wulandari, F., Zenitha, S., Budiati, A., Kurniasih, D., & Djausal, G. (2023). Biodiversity management policy in indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1277(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Dwiyahreni, A. A., Fuad, H. A. H., Muhtar, S., Soesilo, T. E. B., Margules, C., & Supriatna, J. (2021). Changes in the human footprint in and around Indonesia’s terrestrial national parks between 2012 and 2017. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 4510. [CrossRef]

- East Kalimantan Provincial Forestry Service. (2019). Vision and Mission of the Forestry Service of East Kalimantan Province 2019 to 2023. https://dishut.kaltimprov.go.id/profil/visi-dan-misi.

- Ecosystems: Complexity, diversity and nature’s contribution to humanity (1st edition). (2018). Environment Europe Press.

- Ekstrom, J., Bennun, L., & Mitchell, R. (2015). A cross-sector guide for implementing the Mitigation Hierarchy. Cross Sector Biodiversity Initiative. https://www.ipieca.org/resources/a-cross-sector-guide-for-implementing-the-mitigation-hierarchy.

- Emamat, M. S. M. M., Mota, C. M. D. M., Mehregan, M. R., Sadeghi Moghadam, M. R., & Nemery, P. (2022). Using ELECTRE-TRI and FlowSort methods in a stock portfolio selection context. Financial Innovation, 8(1), 11. [CrossRef]

- Ernyasih, E., Mallongi, A., Daud, A., Palutturi, S., Stang, S., Thaha, A. R., Ibrahim, E., & Madhoun, W. A. (2023). Health risk assessment through probabilistic sensitivity analysis of. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 9(4), 933–950. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2013). Green Infrastructure Strategy—Enhancing Europe’s Natural Capital, Brussels, 6.5.2013, COM(2013) 249 final. European Commission. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:d41348f2-01d5-4abe-b817-4c73e6f1b2df.0014.03/DOC_1&format=PDF.

- European Commission. (2020). EU Guidance on Integrating Ecosystems and their Services into Decision-Making. https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/nature-and-biodiversity/green-infrastructure_en.

- Evans, M. C. (2023). Backloading to extinction: Coping with values conflict in the administration of Australia’s federal biodiversity offset policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 82(2), 228–247. [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, A. I., Azizah, N., Yati, E., Atmojo, A. T., Rohman, A., Putra, R., Rahadianto, M. A. E., Ramadhanti, D., Ardani, N. H., Robbani, B. F., Nuha, M. U., Perdana, A. M. P., Sakti, A. D., Aufaristama, M., & Wikantika, K. (2023). Potential Loss of Ecosystem Service Value Due to Vessel Activity Expansion in Indonesian Marine Protected Areas. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 12(2), 75. [CrossRef]

- Filoche, G. (2017). Playing musical chairs with land use obligations: Market-based instruments and environmental public policies in Brazil. Land Use Policy, 63, 20–29. [CrossRef]

- Fisher, B., Turner, R. K., & Morling, P. (2009). Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecological Economics, 68(3), 643–653. [CrossRef]

- Florentine, S., Gibson-Roy, P., Dixon, K. W., & Broadhurst, L. (Eds.). (2023). Ecological Restoration: Moving Forward Using Lessons Learned. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gaveau, D. L. A., Santos, L., Locatelli, B., Salim, M. A., Husnayaen, H., Meijaard, E., Heatubun, C., & Sheil, D. (2021). Forest loss in Indonesian New Guinea (2001–2019): Trends, drivers and outlook. Biological Conservation, 261, 109225. [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P., Macintosh, A., Constable, A. L., & Hayashi, K. (2018). Outcomes from 10 years of biodiversity offsetting. Global Change Biology, 24(2), e643–e654. [CrossRef]

- GIZ. (2024). Sustainable Infrastructure Tools. https://sustainable-infrastructure-tools.org/.

- Global Forest Watch. (2024). Forest Watch Designed for Action. https://www.globalforestwatch.org/map/country/IDN/.

- Gómez-Baggethun, E., & Ruiz-Pérez, M. (2011). Economic valuation and the commodification of ecosystem services. Progress in Physical Geography: Earth and Environment, 35(5), 613–628. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, A., Bull, J. W., Wilcox, C., & Maron, M. (2015). FORUM: Perverse incentives risk undermining biodiversity offset policies. Journal of Applied Ecology, 52(2), 532–537. [CrossRef]

- Government of Indonesia. (1990). Law No.5 of 1990 concerning Conservation of Living Resources and their Ecosystems. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ins3867.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (1999a). Law No. 18 of 1999 on Construction Services. http://www.flevin.com/id/lgso/translations/Laws/Law%20No.%2018%20of%201999%20on%20Construction%20Services.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (1999b). Law No. 41 of 1999 Concerning Forestry. https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/forestry-act-no-41-of-1999-lex-faoc036649/.

- Government of Indonesia. (2004a). Law No. 31 of 2004 on Fisheries. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ins51065Eng.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (2004b). Law No. 32 of 2004 concerning Regional Administration. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ins198699.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (2004c). Law No. 38 of 2004 concerning Roads as amended by Law No. 11/2020 on Job Creation and lastly amended by Law No. 2/2022.

- Government of Indonesia. (2007a). Law No. 26 of 2007 concerning Spatial Planning. https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/law-of-the-republic-of-indonesia-no-26-of-2007-concerning-spatial-planning-lex-faoc163446/.

- Government of Indonesia. (2007b). Law No. 27 of 2007 concerning Investment. https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/law-no-25-of-2007-concerning-investment-lex-faoc201875/.

- Government of Indonesia. (2009a). Law No. 30 of 2009 concerning Electricity. https://www.ecolex.org/details/legislation/law-no-302009-on-electricity-lex-faoc091864/.

- Government of Indonesia. (2009b). Law No. 32 of 2009 on Environmental Protection and Management. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/ins97643.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (2010). Law No. 13 in 2010 on Horticulture.

- Government of Indonesia. (2012). Law No.2 of 2012 concerning Acquisition of Land for Development in the Public Interest. https://peraturan.go.id/files2/uu-no-2-tahun-2012_terjemah.pdf.

- Government of Indonesia. (2013). Law No. 19 of 2013 on the Protection and Empowerment of Farmers. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC169497/.

- Government of Indonesia. (2019). Law N.17 of 2019 on Water Resources. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC192861.

- Government of Indonesia. (2022). Law No. 2 of 2022 on Job Creation.

- Government of Indonesia. (2023). Law No. 6 of 2023 concerning the Stipulation of Government Regulations intended to become Law, in Lieu of Law no. 2 of 2022 concerning Job Creation. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC221248/.

- Green Climate Fund. (2016). PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (Indonesia). https://www.greenclimate.fund/ae/ptsmi.

- Greene, W. (2018). Econometric analysis (Eighth edition). Pearson.

- Hadad, I. (1998). The Indonesian Biodiversity Foundation (Yayasan KEHATI). Profiles of the NEFS. UN Convention on Biological Diversity. CBD. https://www.cbd.int/financial/trustfunds/Indonesia-kehati.pdf.

- Hadi, S. P., Hamdani, R. S., & Roziqin, A. (2023). A sustainability review on the Indonesian job creation law. Heliyon, 9(2), e13431. [CrossRef]

- Handayani, I. G. A. K. R., Sulistiyono, A., Leonard, T., Gunardi, A., & Najicha, F. U. (2018). Environmental management strategy in mining activities in forest area accordance with the based justice in Indonesia. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 21(2). Scopus. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85050293493&partnerID=40&md5=d0b28cb5d2238eb382e77d3cb23b09f7.

- Hapsari, L., & Budiharta, S. (2021). Integrating indicators of natural regeneration, enrichment planting, above-ground carbon stock, micro-climate and soil to asses vegetation succession in postmining reclamation in tropical forest. Turkish Journal of Botany, 45(5), 457–467. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P. A., Berry, P. M., Simpson, G., Haslett, J. R., Blicharska, M., Bucur, M., Dunford, R., Egoh, B., Garcia-Llorente, M., Geamănă, N., Geertsema, W., Lommelen, E., Meiresonne, L., & Turkelboom, F. (2014). Linkages between biodiversity attributes and ecosystem services: A systematic review. Ecosystem Services, 9, 191–203. [CrossRef]

- Hasibuan, H. S., & Mulyani, M. (2022). Transit-Oriented Development: Towards Achieving Sustainable Transport and Urban Development in Jakarta Metropolitan, Indonesia. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(9), Article 9. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Helmi, H., Hafrida, H., Fitria, F., & Najwan, J. (2019). Documenting legal protection of indigenous forests in realizing indigenous legal community rights in Jambi Province. Library Philosophy and Practice, 2019. Scopus. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85072802844&partnerID=40&md5=19ebf070776b08a564d066e99e9b3c50.

- Ho, P., Nor-Hisham, B. M. S., & Zhao, H. (2020). Limits of the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in Malaysia: Dam Politics, Rent-Seeking, and Conflict. Sustainability, 12(24), Article 24. [CrossRef]

- Holl, K. (2020). Primer of Ecological Restoration. Island Press; eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=nlebk&AN=2965730&site=ehost-live&authtype=ip,uid.

- Hubert Ta, L., & Campbell, B. (2023). Environmental protection in Madagascar: Biodiversity offsetting in the mining sector as a corporate social responsibility strategy. Extractive Industries and Society, 15. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- IDH. (2024). The National Initiative on Sustainable and Climate Smart Oil Palm Smallholders (NI SCOPS). IDH Sustainable Trade Inititative, Government of the the Netherlands. https://www.idhsustainabletrade.com/uploaded/2020/10/200930-NI-SCOPS_2-pager_Indonesia_Final.pdf.

- Indonesia Investments. (2024, January 18). Perusahaan Listrik Negara. https://www.indonesia-investments.com/business/indonesian-companies/perusahaan-listrik-negara-pln-soe/item409.

- IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Version 1). Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- IPBES. (2022). Methodological assessment of the diverse values and valuation of nature of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Isworo, S., & Oetari, P. S. (2022). Flora and fauna in the areas around artisanal gold mining in Selogiri Sub-district, Wonogiri, Indonesia. Biodiversitas, 23(12), 6600–6618. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Isworo, S., & Oetari, P. S. (2023). Diversity of vegetation, birds, dragonflies and butterflies at coal mining reclamation sites in South Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biodiversitas, 24(10), 5376–5390. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C., Vaissiere, A.-C., Bas, A., & Calvet, C. (2016). Investigating the inclusion of ecosystem services in biodiversity offsetting. Ecosystem Services, 21, 92–102. [CrossRef]

- Jannah, M., Kholish, Moh., & Tohari, I. (2020). Legalization of Waqf Forests in Indonesia: The Registration Process. Indonesia Law Review, 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Jati, A. S., Samejima, H., Fujiki, S., Kurniawan, Y., Aoyagi, R., & Kitayama, K. (2018). Effects of logging on wildlife communities in certified tropical rainforests in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Forest Ecology and Management, 427, 124–134. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Jhariya, D. C., Kumar, T., & Pandey, H. K. (2020). Watershed prioritization based on soil and water hazard model using remote sensing, geographical information system and multi-criteria decision analysis approach. Geocarto International, 35(2), 188–208. [CrossRef]

- Jong, H. N. (2020). Indonesia’s omnibus law a ‘major problem’ for environmental protection. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2020/11/indonesia-omnibus-law-global-investor-letter/.

- Jong, H. N. (2024, February 13). Palm oil deforestation makes comeback in Indonesia after decade-long slump. Mongabay. https://news.mongabay.com/2024/02/palm-oil-deforestation-makes-comeback-in-indonesia-after-decade-long-slump/.

- Kalliolevo, H., Gordon, A., Sharma, R., Bull, J. W., & Bekessy, S. A. (2021). Biodiversity offsetting can relocate nature away from people: An empirical case study in Western Australia. Conservation Science and Practice, 3(10), e512. [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, Ç. K., Çakır, Ç., Birinci, S., & Kızılkan, Y. (2021). GIS-Fuzzy DEMATEL MCDA model in the evaluation of the areas for ecotourism development: A case study of “Uzundere”, Erzurum-Turkey. Applied Geography, 136, 102577. [CrossRef]

- Kenneth R. Olson & Lois Wright Morton. (2017). Managing the upper Missouri River for agriculture, irrigation, flood control, and energy. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 72(5), 105A. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H. (2020). Indonesia plans $430bn infra spend by 2024. Infrastructure Investor. https://www.infrastructureinvestor.com/indonesia-plans-430bn-infra-spend-by-2024/#:~:text=Last%20year%2C%20the%20government%20said,invest%20the%20%24180%20billion%20balance.

- Kim, Y.-S., Bae, J. S., Fisher, L. A., Latifah, S., Afifi, M., Lee, S. M., & Kim, I.-A. (2016). Indonesia’s Forest Management Units: Effective intermediaries in REDD+ implementation? Forest Policy and Economics, 62, 69–77. [CrossRef]

- Koh, N. S., Hahn, T., & Boonstra, W. J. (2019). How much of a market is involved in a biodiversity offset? A typology of biodiversity offset policies. Journal of Environmental Management, 232, 679–691. [CrossRef]

- Koshim, A., Sergeyeva, A., Kakimzhanov, Y., Aktymbayeva, A., Sakypbek, M., & Sapiyeva, A. (2023). Sustainable Development of Ecotourism in “Altynemel” National Park, Kazakhstan: Assessment through the Perception of Residents. Sustainability, 15(11), 8496. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. (Ed.). (2012). The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: Ecological and economic foundations ; [TEEB: The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity] (1. publ. in paperback). Routledge.

- Lai, J. Y. (2020). In Pursuit of Just Forest Governance: Lessons from the Everyday Practices of Environmental Impact Assessment in Indonesia [University of Edinburgh]. https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/37993/Lai2021.pdf.

- LAN. (2024). History of LAN RI. https://lan.go.id/?page_id=57.

- Larekeng, S. H., Nursaputra, M., Nasri, N., Hamzah, A. S., Mustari, A. S., Arif, A. R., Ambodo, A. P., Lawang, Y., & Ardiansyah, A. (2022). A Diversity Index Model based on Spatial Analysis to Estimate High Conservation Value in a Mining Area. Forest and Society, 6(1), 142–156. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Levrel, H., Scemama, P., & Vaissière, A.-C. (2017). Should We Be Wary of Mitigation Banking? Evidence Regarding the Risks Associated with this Wetland Offset Arrangement in Florida. Ecological Economics, 135, 136–149. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Lim, F. K. S., Carrasco, L. R., Edwards, D. P., & McHardy, J. (2023). Land-use change from market responses to oil palm intensification in Indonesia. Conservation Biology. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D. B., Crane, M., Evans, M. C., Maron, M., Gibbons, P., Bekessy, S., & Blanchard, W. (2017). The anatomy of a failed offset. Biological Conservation, 210, 286–292. [CrossRef]

- Listyarini, S., Warlina, L., & Sambas, A. (2021). Air Quality Monitoring System in South Tangerang Based on Arduino Uno: From Analysis to Implementation. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 1115(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Lodhia, S., Martin, N., & Rice, J. (2018). Appraising offsets as a tool for integrated environmental planning and management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 178, 34–44. [CrossRef]

- Losos, E. (2019). Reducing Environmental Risks from Belt and Road Initiative Investments in Transportation Infrastructure. World Bank Group. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/700631548446492003/pdf/WPS8718.pdf.

- Mafira, T., Mecca, B., & Muluk, S. (2020). Indonesia Environment Fund: Bridging the Financing Gap in Environmental Programs. https://climatepolicyinitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Indonesia-Environment-Bridging-the-financing-gap.pdf.

- Maron, M., Bull, J. W., Evans, M. C., & Gordon, A. (2015). Locking in loss: Baselines of decline in Australian biodiversity offset policies. Biological Conservation, 192, 504–512. [CrossRef]

- Maron, M., Gordon, A., Mackey, B. G., Possingham, H. P., & Watson, J. E. M. (2016). Interactions Between Biodiversity Offsets and Protected Area Commitments: Avoiding Perverse Outcomes. Conservation Letters, 9(5), 384–389. [CrossRef]

- Maron, M., Hobbs, R. J., Moilanen, A., Matthews, J. W., Christie, K., Gardner, T. A., Keith, D. A., Lindenmayer, D. B., & McAlpine, C. A. (2012). Faustian bargains? Restoration realities in the context of biodiversity offset policies. Biological Conservation, 155, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Alier, J. (2023). Land, Water, Air and Freedom: The Making of World Movements for Environmental Justice. Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mathys, A. S., Van Vianen, J., Rowland, D., Narulita, S., Palomo, I., Pascual, U., Sutherland, I. J., Ahammad, R., & Sunderland, T. (2023). Participatory mapping of ecosystem services across a gradient of agricultural intensification in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Ecosystems and People, 19(1), 2174685. [CrossRef]

- MECCE, & UNESCO. (2024). CCE Country Profile: Indonesia. Country Profiles. Interactive Data Platform. https://mecce.ca/country_profiles/cce-country-profile-indonesia/.

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Program) (Ed.). (2005). Ecosystems and human well-being: Synthesis. Island Press.

- Ministerie van Landbouw, N. en V. (2023). SustainPalm: Indonesia and the Netherlands cooperation on sustainable palm oil - Nieuwsbericht - Agroberichten Buitenland [Nieuwsbericht]. Ministerie van Landbouw, Natuur en Voedselkwaliteit. https://www.agroberichtenbuitenland.nl/actueel/nieuws/2023/02/28/sustainpalm---indonesia-and-the-netherlands-cooperation-on-sustainable-palm-oil.

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. (2024a). Directorate General of New Renewable Energy and Energy Conservation. https://www.esdm.go.id/en/profile/duties-functions/directorate-general-of-new-renewable-energy-and-energy-conservation.

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. (2024b, January 18). Duties & Functions. Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. Republic of Indonesia. https://www.esdm.go.id/en/profile/duties-functions/kementerian-esdm.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024a). Performance Evaluation of Peat Degradation Control. http://pkgppkl.menlhk.go.id/v0/en/evaluasi-pengendalian-kerusakan-gambut/.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024b, January 18). Badan Penelitian, Pengembangan dan Inovasi Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan. Forestry and Environmental Research, Development and Innovation Agency. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/badan-standardisasi-instrumen-lhk-bsi.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024c, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Konservasi Sumberdaya Alam dan Ekosistem (KSDAE) Kementrian LHK. Directorate General of Natural Resources and Ecosystems Conservation. Direktorat Jenderal KSDAE. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/direktorat-jenderal-konservasi-sumberdaya-alam-dan-ekosistem-ksdae.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024d, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Penegakkan Hukum Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan Kementrian LHK. Directorate General on Environmental and Forestry Law Enforcement. Direktorat Jenderal GAKKUM. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/direktorat-jenderal-penegakkan-hukum-lingkungan-hidup-dan-kehutanan.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024e, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Pengelolaan Sampah, Limbah, Bahan Beracun dan Berbahaya (PSLB3) Kementrian LHK. DG for Waste and B3 Toxic and Hazardous Materials Management. Direktorat Jenderal PSLB3. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/direktorat-jenderal-pengelolaan-sampah-limbah-bahan-beracun-dan-berbahaya-pslb-3.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024f, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Pencemaran dan Kerusakan Lingkungan—Kementerian Lingkungan Hidup dan Kehutanan. Directorate General for Pollution and Environmental Degradation Control. https://ppkl.menlhk.go.id/website/index.php?q=13&s=bd307a3ec329e10a2cff8fb87480823da114f8f4.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024g, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim Kementrian LHK. Directorate General of Climate Change. Direktorat Jenderal Pengendalian Perubahan Iklim. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/direktorat-jenderal-pengendalian-perubahan-iklim.

- Ministry of Environment and Forestry. (2024h, January 18). Direktorat Jenderal Planologi Kehutanan dan Tata Lingkungan (PKTL) Kementrian LHK. Directorate General DG of Planology. Direktorat Jenderal Planologi Kehutanan dan Tata Lingkungan. https://www.menlhk.go.id/profile/echelon/direktorat-jenderal-planologi-kehutanan-dan-tata-lingkungan-pktl.

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. (2009). Regulation of the Minister of Finance on the Infrastructure Finance Company. https://ojk.go.id/id/kanal/iknb/regulasi/lembaga-jasa-keuangan-khusus/peraturan-keputusan-menteri/Documents/479.pdf.

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. (2022). Environment, Social, and Governance (ESG) Framework in Government Support and Facility for Infrastructure Financing. UNDP. https://kpbu.kemenkeu.go.id/backend/Upload/guideline/GUIDELINE22111200170842.pdf.

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. (2024a). Fiscal Policy Agency. https://fiskal.kemenkeu.go.id/.

- Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia. (2024b). Task and Functions. https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/en/profile/tugas-dan-fungsi.

- Ministry of National Development Planning. (2023). Public Private Partnership. Infrastructure Plan in Indonesia. https://perpustakaan.bappenas.go.id/e-library/file_upload/koleksi/migrasi-data-publikasi/file/Unit_Kerja/Direktorat%20Pengembangan%20Pendanaan%20Pembangunan/PPP%20Book%202023.pdf.

- Mississippi State University. (2024). Strategic Conservation Assessment of Gulf Coast Landscapes. https://sca-tool-suite.herokuapp.com/tool.

- Muchtar, S., & Yunus, A. (2019). Environmental law enforcement in forestry crime: A disjunction between ideality and reality. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 343(1), 012066. [CrossRef]

- Mujetahid, A., Nursaputra, M., & Soma, A. S. (2023). Monitoring Illegal Logging Using Google Earth Engine in Sulawesi Selatan Tropical Forest, Indonesia. Forests, 14(3), 652. [CrossRef]

- Muradian, R., Arsel, M., Pellegrini, L., Adaman, F., Aguilar, B., Agarwal, B., Corbera, E., Ezzine de Blas, D., Farley, J., Froger, G., Garcia-Frapolli, E., Gómez-Baggethun, E., Gowdy, J., Kosoy, N., Le Coq, J. F., Leroy, P., May, P., Méral, P., Mibielli, P., … Urama, K. (2013). Payments for ecosystem services and the fatal attraction of win-win solutions. Conservation Letters, 6(4), 274–279. [CrossRef]

- Mutawali, M., Maskun, M., Wahab, H. A., & Yeyeng, A. T. (2023). Implementation of FLEGT Licensing Scheme in Deforestation Law Enforcement: Improvements and Handling in Indonesia. Jurnal Hukum Unissula, 39(2), 130–156.

- Narain, D., & Maron, M. (2018). Cost shifting and other perverse incentives in biodiversity offsetting in India. Conservation Biology, 32(4), 782–788. [CrossRef]

- Narendra, B. H., Siregar, C. A., Turjaman, M., Hidayat, A., Rachmat, H. H., Mulyanto, B., Maharani, R., Rayadin, Y., Prayudyaningsih, R., Yuwati, T. W., Prematuri, R., & Susilowati, A. (2021). Managing and reforesting degraded post-mining landscape in Indonesia: A review. Land, 10(6). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Nath, A. J., Kumar, R., Devi, N. B., Rocky, P., Giri, K., Sahoo, U. K., Bajpai, R. K., Sahu, N., & Pandey, R. (2021). Agroforestry land suitability analysis in the Eastern Indian Himalayan region. Environmental Challenges, 4, 100199. [CrossRef]

- Natural England. (2023a). Green Infrastructure Planning and Design Guide. https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/GreenInfrastructure/downloads/Design%20Guide%20-%20Green%20Infrastructure%20Framework.pdf.

- Natural England. (2023b). Green Infrastructure Standards. https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/GreenInfrastructure/downloads/Green%20Infrastructure%20Standards%20for%20England%20Summary%20v1.1.pdf.

- Natural England. (2023c). Natural England Green Infrastructure Principles. https://designatedsites.naturalengland.org.uk/GreenInfrastructure/downloads/GreenInfrastructurePrinciples.pdf.

- Naylor, R. L., Higgins, M. M., Edwards, R. B., & Falcon, W. P. (2019). Decentralization and the environment: Assessing smallholder oil palm development in Indonesia. Ambio, 48(10), Article 10. [CrossRef]

- Neupane, P. R., Wiati, C. B., Angi, E. M., Köhl, M., Butarbutar, T., Reonaldus, & Gauli, A. (2019). How REDD+ and FLEGT-VPA processes are contributing towards SFM in Indonesia – the specialists’ viewpoint. International Forestry Review, 21(4), 460–485. [CrossRef]

- Niner, H. J., Jones, P. J. S., Milligan, B., & Styan, C. (2021). Exploring the practical implementation of marine biodiversity offsetting in Australia. Journal of Environmental Management, 295. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Nishi, M., & Subramanian, S. M. (Eds.). (2023). Ecosystem restoration through managing socio-ecological production landscapes and seascapes (SEPLS). Springer.

- Norgaard, R. B. (2010). Ecosystem services: From eye-opening metaphor to complexity blinder. Special Section - Payments for Environmental Services: Reconciling Theory and Practice, 69(6), 1219–1227. [CrossRef]

- Novianti, V., Marrs, R. H., Choesin, D. N., Iskandar, D. T., & Suprayogo, D. (2018). Natural regeneration on land degraded by coal mining in a tropical climate: Lessons for ecological restoration from Indonesia. Land Degradation and Development, 29(11), 4050–4060. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H. Y. S. H., Indrajaya, Y., Astana, S., Murniati, Suharti, S., Basuki, T. M., Yuwati, T. W., Putra, P. B., Narendra, B. H., Abdulah, L., Setyawati, T., Subarudi, Krisnawati, H., Purwanto, Saputra, M. H., Lisnawati, Y., Garsetiasih, R., Sawitri, R., Putri, I. A. S. L. P., … Rahmila, Y. I. (2023). A Chronicle of Indonesia’s Forest Management: A Long Step towards Environmental Sustainability and Community Welfare. Land, 12(6), 1238. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H. Y. S. H., Nurfatriani, F., Indrajaya, Y., Yuwati, T. W., Ekawati, S., Salminah, M., Gunawan, H., Subarudi, S., Sallata, M. K., Allo, M. K., Muin, N., Isnan, W., Putri, I. A. S. L. P., Prayudyaningsih, R., Ansari, F., Siarudin, M., Setiawan, O., & Baral, H. (2022). Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services from Indonesia’s Remaining Forests. Sustainability, 14(19), 12124. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, H. Y. S. H., Skidmore, A., & Hussin, Y. A. (2022). Verifying Indigenous based-claims to forest rights using image interpretation and spatial analysis: A case study in Gunung Lumut Protection Forest, East Kalimantan, Indonesia. GeoJournal, 87(1), 403–421. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2016). Biodiversity Offsets: Effective Design and Implementation. OECD. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2019). Good Governance for Critical Infrastructure Resilience. OECD. [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2020). A Comprehensive Overview of Global Biodiversity Finance. https://www.oecd.org/environment/resources/biodiversity/report-a-comprehensive-overview-of-global-biodiversity-finance.pdf.

- OECD. (2022). Recommendation of the Council on the Governance of Infrastructure, OECD/LEGAL/0460. https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0460.

- O’Neill, J. (2023). Natural capital and biodiversity. In E. Bertrand & V. Panitch, The Routledge Handbook of Commodification (1st ed., pp. 337–350). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 89. [CrossRef]

- Perdinan, Tjahjono, R. E. P., Infrawan, D. Y. D., Aprilia, S., Adi, R. F., Basit, R. A., Wibowo, A., Kardono, & Wijanarko, K. (2024). Translation of international frameworks and national policies on climate change, land degradation, and biodiversity to develop integrated risk assessment for watershed management in Indonesia. Watershed Ecology and the Environment, 6, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Perera, O., & Uzsoki, D. (2017). Biodiversity and Infrastructure: A better nexus? WWF Switzerland. https://www.wwf.ch/sites/default/files/doc-2017-11/Final%20WWF%20IISD%20Study-mainstreaming%20biodiversity%20into%20infrastructure%20sector.pdf.

- Permadi, I., Maharani, D. P., & Ayub, Z. A. (2023). Averting Deforestation: Designing the Model of a Public Participation-Based Environmental Agreement of Shifting Functionality of Forest. Journal of Indonesian Legal Studies, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Potschin, M., Haines-Young, R. H., Fish, R., & Turner, R. K. (Eds.). (2016). Routledge handbook of ecosystem services. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- PT SMI. (2024). PT SMI at Glance. https://ptsmi.co.id/pt-smi-at-glance.

- Purnomo, H., Okarda, B., Puspitaloka, D., Ristiana, N., Sanjaya, M., Komarudin, H., Dermawan, A., Andrianto, A., Kusumadewi, S. D., & Brady, M. A. (2023). Public and private sector zero-deforestation commitments and their impacts: A case study from South Sumatra Province, Indonesia. Land Use Policy, 134, 106818. [CrossRef]

- Putri, E. I. K., Dharmawan, A. H., Hospes, O., Yulian, B. E., Amalia, R., Mardiyaningsih, D. I., Kinseng, R. A., Tonny, F., Pramudya, E. P., Rahmadian, F., & Suradiredja, D. Y. (2022). The Oil Palm Governance: Challenges of Sustainability Policy in Indonesia. Sustainability, 14(3), 1820. [CrossRef]

- PwC. (2023, September). Mining in Indonesia: Investment, Taxation and Regulatory Guide 2023. https://www.pwc.com/id/en/energy-utilities-mining/assets/mining/mining-guide-2023.pdf.

- Quinta-Nova, L., & Ferreira, D. (2022). Analysis of the suitability for ecotourism in Beira Baixa region using a spatial decision support system based on a geographical information system. Regional Science Policy & Practice, rsp3.12583. [CrossRef]

- Razak, T. B., Boström-Einarsson, L., Alisa, C. A. G., Vida, R. T., & Lamont, T. A. C. (2022). Coral reef restoration in Indonesia: A review of policies and projects. Marine Policy, 137, 104940. [CrossRef]

- Regional Development Planning Agency of East Kalimantan. (2024). Realization of Quality Regional Development Planning in the Context of Making East Kalimantan a Leading Agro-Industry and Energy Center. https://bappeda.kaltimprov.go.id/page/visi-dan-misi.

- Rodríguez-Merino, A., García-Murillo, P., & Fernández-Zamudio, R. (2020). Combining multicriteria decision analysis and GIS to assess vulnerability within a protected area: An objective methodology for managing complex and fragile systems. Ecological Indicators, 108, 105738. [CrossRef]

- Rolando, J. L., Turin, C., Ramírez, D. A., Mares, V., Monerris, J., & Quiroz, R. (2017). Key ecosystem services and ecological intensification of agriculture in the tropical high-Andean Puna as affected by land-use and climate changes. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 236, 221–233. [CrossRef]

- Roy, B. (1996). Multicriteria Methodology for Decision Aiding (Vol. 12). Springer US. [CrossRef]

- Russell, M. (2020). Political institutions in Indonesia: Democracy, decentralisation, diversity. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2020)646149.

- Rustiadi, E., Pravitasari, A. E., Priatama, R. A., Singer, J., Junaidi, J., Zulgani, Z., & Sholihah, R. I. (2023). Regional Development, Rural Transformation, and Land Use/Cover Changes in a Fast-Growing Oil Palm Region: The Case of Jambi Province, Indonesia. Land, 12(5). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Sales Rosa, J. C., Campos, P. B. R., Nascimento, C. B., Souza, B. A., Valetich, R., & Sánchez, L. E. (2023). Enhancing ecological connectivity through biodiversity offsets to mitigate impacts on habitats of large mammals in tropical forest environments. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal, 41(5), 333–348. [CrossRef]

- Samiappan, S., Shamaskin, A., Liu, J., Liang, Y., Roberts, J., Sesser, A. L., Westlake, S. M., Linhoss, A., Evans, K. O., Tirpak, J., Hopkins, T. E., Ashby, S., & Burger, L. W. (2022). Evidence-based land conservation framework using multi-criteria acceptability analysis: A geospatial tool for strategic land conservation in the Gulf coast of the United States. Environmental Modelling & Software, 156, 105493. [CrossRef]

- Samiappan, S., Shamaskin, A., Liu, J., Linhoss, A., & Evans, K. (2020). Strategic Conservation of Gulf Coast Landscapes Using Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis and Open Source Remote Sensing and GIS Data. IGARSS 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 6662–6665. [CrossRef]

- Satriastanti, F. E. (2016). Indonesia exploring new model to fund national parks. https://news.mongabay.com/2016/09/indonesia-exploring-new-model-to-fund-national-parks/.

- Sembiring, R., Fatimah, I., & Widyaningsih, G. A. (2020). Indonesia’s Omnibus Bill on Job Creation: A Setback for Environmental Law? Chinese Journal of Environmental Law, 4(1), 97–109. [CrossRef]

- Sesser, A. L., Westlake, S. M., Schafer, C., Roberts, J., Samiappan, S., Allen, Y., Linhoss, A., Hopkins, T. E., Liu, J., Shamaskin, A., Tirpak, J., Smith, R. N., & Evans, K. O. (2022). Co-producing decision support tools for strategic conservation of Gulf Coast Landscapes. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability, 4, 100156. [CrossRef]

- SFI. (2021). Sustainable Finance Roadmap Phase II (2021—2025). Sustainable Finance Indonesia. https://www.ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/publikasi/Documents/Pages/Roadmap-Keuangan-Berkelanjutan-Tahap-II-%282021-2025%29/Roadmap%20Keuangan%20Berkelanjutan%20Tahap%20II%20%282021-2025%29.pdf.

- SFI. (2022). Indonesia Green Taxonomy. Sustainable Finance Indonesia. https://ojk.go.id/id/berita-dan-kegiatan/info-terkini/Documents/Pages/Taksonomi-Hijau-Indonesia-Edisi-1---2022/Taksonomi%20Hijau%20Edisi%201.0%20-%202022.pdf.

- Shamaskin, A., Samiappan, S., Liu, J., Roberts, J., Linhoss, A., & Evans, K. (2019). Multi-Attribute Ecological and Socioeconomic Geodatabase for the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Region of the United States. Data, 5(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, S. (2012). Ecological economics: Sustainability in practice. Springer.

- Shmelev, S. E., Agbleze, L., & Spangenberg, J. H. (2023). Multidimensional Ecosystem Mapping: Towards a More Comprehensive Spatial Assessment of Nature’s Contributions to People in France. Sustainability, 15(9). [CrossRef]

- Shmelev, S. E., & Speck, S. U. (2018). Green fiscal reform in Sweden: Econometric assessment of the carbon and energy taxation scheme. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 90, 969–981. [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, J., Nuryawan, A., Harahap, M. M., Ismail, M. H., Rauf, A., Kurniawan, H., Gandaseca, S., & Karuniasa, M. (2023). Mangrove cover change (2005–2019) in the Northern of Medan City, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Geocarto International, 38(1). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Siregar, Y. P. (2021). Accelerating Regional Development of the Outer Islands: The Implementation of Special Economic Zones in Indonesia, 2011–18. Korea Development Institute School of Public Policy and Management. https://www.effectivecooperation.org/system/files/2021-07/GDI%20Case%20Study%20Indonesia%20SEZ.pdf.

- Sloan, S., Campbell, M. J., Alamgir, M., Collier-Baker, E., Nowak, M. G., Usher, G., & Laurance, W. F. (2018). Infrastructure development and contested forest governance threaten the Leuser Ecosystem, Indonesia. Land Use Policy, 77, 298–309. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G. (2023, July 20). Mapping a more sustainable palm oil future in Indonesia. CIFOR Forests News. https://forestsnews.cifor.org/83622/mapping-a-more-sustainable-palm-oil-future-in-indonesia?fnl=.

- Söderbaum, P. (2013). Ecological economics in relation to democracy, ideology and politics. Ecological Economics, 95, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Souza, B. A., Rosa, J. C. S., Siqueira-Gay, J., & Sánchez, L. E. (2021). Mitigating impacts on ecosystem services requires more than biodiversity offsets. Land Use Policy, 105, 105393. [CrossRef]

- Spangenberg, J. H., & Settele, J. (2010). Precisely incorrect? Monetising the value of ecosystem services. Ecosystem Services – Bridging Ecology, Economy and Social Sciences, 7(3), 327–337. [CrossRef]

- Spash, C. L. (2015). Bulldozing biodiversity: The economics of offsets and trading-in Nature. Biological Conservation, 192, 541–551. [CrossRef]

- Spencer, K. L., Deere, N. J., Aini, M., Avriandy, R., Campbell-Smith, G., Cheyne, S. M., Gaveau, D. L. A., Humle, T., Hutabarat, J., Loken, B., Macdonald, D. W., Marshall, A. J., Morgans, C., Rayadin, Y., Sanchez, K. L., Spehar, S., Sugardjito, J., Wittmer, H. U., Supriatna, J., & Struebig, M. J. (2023). Implications of large-scale infrastructure development for biodiversity in Indonesian Borneo. Science of the Total Environment, 866. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Stone, R., Callaway, R., & Bull, J. C. (2019). Are biodiversity offsetting targets of ecological equivalence feasible for biogenic reef habitats? Ocean and Coastal Management, 177, 97–111. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Sulistyowati, L., Yolanda, Y., & Andareswari, N. (2023). Harbor water pollution by heavy metal concentrations in sediments. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management, 9(4), 885–898. [CrossRef]

- Suryanto, Nurrochmat, D., Tarigan, S., Siregar, I., Yassir, I., Tandio, T., & Abdulah, L. (2023). Defining the objectives and roles of Indonesian production forest governance through the multi-business forestry policy narrative. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1266(1), 012030. [CrossRef]

- Takam Tiamgne, X., Kanungwe Kalaba, F., Raphael Nyirenda, V., & Phiri, D. (2022). Modelling areas for sustainable forest management in a mining and human dominated landscape: A Geographical Information System (GIS)- Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) approach. Annals of GIS, 28(3), 343–357. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A., Saran, S., & Avishek, K. (2021). HABITAT SUITABILITY ANALYSIS OF TIGERS USING DECISION SUPPORT SYSTEM OF INDIAN BIO-RESOURCE INFORMATION NETWORK (IBIN) PORTAL. https://a-a-r-s.org/proceeding/ACRS2021/6%20Environmental%20Domain/ACRS21_088.pdf.

- TNFD. (2023). Recommendations of the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures. https://tnfd.global/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Recommendations_of_the_Taskforce_on_Nature-related_Financial_Disclosures_September_2023.pdf?v=1695118661.

- Triana, K., & Wahyudi, A. J. (2020). GIS Developments for Ecosystem-based Marine Spatial Planning and the Challenges Faced in Indonesia. ASEAN Journal on Science and Technology for Development, 36(3). [CrossRef]

- UK national ecosystem assessment: Technical report. (2011). United Nations Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre.

- UN. (1992a). Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1992/06/19920605%2008-44%20PM/Ch_XXVII_08p.pdf.

- UN. (1992b). Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf.

- UN CBD. (2022). Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, CBD/COP/DEC/15/4 19 December 2022. UNEP. https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf.

- UN ESCAP. (2018). The Republic of Indonesia. Fact Sheet. https://sdghelpdesk.unescap.org/sites/default/files/2018-02/Fact_Sheet_Indonesia.pdf.

- UNDP. (2014). The Indonesian Palm Oil Platform Palm and the National Action Plan. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/gcp/UNDP_GCP_Indonesia---Palm-Oil-Platform-and-National-Action-Plan.pdf.

- UNDP. (2024, January 18). Indonesia: Sustainable Palm Oil. https://www.undp.org/facs/indonesia-sustainable-palm-oil.

- UNDRR. (2023, March 14). Ministry of Environment and Forestry (Indonesia). http://www.undrr.org/organization/ministry-environment-and-forestry-indonesia.

- UNEP. (2002). Environmental Impact Assessment: Training Resource Manual. https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/26503/EIA_Training_Resource_Manual.pdf.

- UNEP (Ed.). (2010). Mainstreaming the economics of nature: A synthesis of the approach, conclusions and recommendations of teeb. UNEP.

- UNEP. (2018). Assessing Environmental Impacts: A Global Review of Legislation. https://www.unep.org/resources/assessment/assessing-environmental-impacts-global-review-legislation.

- UNEP. (2022a). How innovative finance is helping to protect Indonesia’s forests. https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/how-innovative-finance-helping-protect-indonesias-forests.

- UNEP. (2022b). International Good Practice Principles for Sustainable Infrastructure. https://www.unep.org/resources/publication/international-good-practice-principles-sustainable-infrastructure.

- UNEP. (2023). State of Finance for Nature 2023: The Big Nature Turnaround - Repurposing $7 Trillion to Combat Nature Loss. United Nations Environment Programme. [CrossRef]

- Utama, K. W., Saraswati, R., Putrijanti, A., & Sukmadewi, Y. D. (2023). Environmental protection barriers in Indonesia in the form of Administrative Effort. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1270(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. (2015). Markets in environmental governance. From theory to practice. Ecological Economics, 117, 225–233. [CrossRef]

- Wageningen University. (2023). SustainPalm: Sustainable oil palm Indonesia. WUR. https://www.wur.nl/en/project/sustainpalm-sustainable-oil-palm-indonesia.htm.

- Wang, J.-J., Jing, Y.-Y., Zhang, C.-F., & Zhao, J.-H. (2009). Review on multi-criteria decision analysis aid in sustainable energy decision-making. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 13(9), 2263–2278. [CrossRef]

- Wende, W., Tucker, G.-M., Quétier, F., Rayment, M., & Darbi, M. (Eds.). (2018). Biodiversity Offsets. Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2021). WHO global air quality guidelines. Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), ozone, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide. WHO. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/345329/9789240034228-eng.pdf.

- Widayanti, T. F., Syarif, L. M., Aswan, M., Hakim, M. Z., Djafart, E. M., & Ratnawati. (2022). Implementation of Biodiversity Conventions in Protecting and Conserving Indonesia’s Marine Environment. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 1118(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Woodbury, D. J., Yassir, I., Doroski, D. A., Queenborough, S. A., & Ashton, M. S. (2020). Filling a void: Analysis of early tropical soil and vegetative recovery under leguminous, post-coal mine reforestation plantations in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Degradation and Development, 31(4), 473–487. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Yanamandra, S. (2020). Sustainable Infrastructure: An Overview Placing infrastructure in the context of sustainable development. University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/sustainable-infrastructure-an-overview.pdf.

- Yu, L., Cao, Y., Cheng, Y., Zhao, Q., Xu, Y., Kanniah, K., Lu, H., Yang, R., & Gong, P. (2023). A study of the serious conflicts between oil palm expansion and biodiversity conservation using high-resolution remote sensing. Remote Sensing Letters, 14(6), 654–668. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Yunanto, T., Mitlöhner, R., & Bürger-Arndt, R. (2019). Vegetation development and the condition of natural regeneration after coal mine reclamation in East Kalimantan, Indonesia. 2019-September, 1289–1302. Scopus. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Lee, J. S. H., Elmore, A. J., Fatimah, Y. A., Numata, I., Zhang, X., & Cochrane, M. A. (2022). Spatial patterns and drivers of smallholder oil palm expansion within peat swamp forests of Riau, Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters, 17(4). Scopus. [CrossRef]

- zu Ermgassen, S. O. S. E., Baker, J., Griffiths, R. A., Strange, N., Struebig, M. J., & Bull, J. W. (2019). The ecological outcomes of biodiversity offsets under “no net loss” policies: A global review. Conservation Letters, 12(6), e12664. [CrossRef]

- Zuhry, N., Suprapto, D., & Hendrarto, B. (2021). Biodiversity of the “Karang Jeruk” coral reef ecosystem in Tegal regency, Central Java, Indonesia. 755(1). Scopus. [CrossRef]

| Coefficient | Std.Error | t-value | t-prob | Part.R^2 | |

| Constant | 74.1573 | 7.388 | 10.0 | 0.0000 | 0.8630 |

| Population | -1.20977e-07 | 4.172e-0 | -2.9 | 0.0104 | 0.3445 |

| GDP | 0.00171139 | 0.0004377 | 3.91 | 0.0012 | 0.4886 |

| Palm | -0.140027 | 0.02694 | -5.2 | 0.0001 | 0.6281 |

| Coal | -0.0114079 | 0.003215 | -3.55 | 0.0027 | 0.4404 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).