1. Introduction

Cluster of Differentiation 38 (CD38) is a type II transmembrane ecto-enzyme ubiquitously expressed in most tissues and cells in mice and humans [

1]. Predominantly, CD38 is highly expressed in B cells, plasma cells, natural killer cells, dendritic cells, T cells, monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and hematopoietic stem cells [

1]. CD38 is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD

+) glycohydrolase, which breaks down NAD

+ and generates nicotinamide (NAM), ADP-ribose (ADPR), and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. NAD

+ has limited ability to diffuse through cell membrane barriers and plays an important role in activating NAD

+-dependent signaling pathways in different subcellular compartments [

5]. NAD

+ can be reduced to NADH via dehydrogenases, and NAD

+ can be phosphorylated to NADP

+ via NAD

+ kinases [

6]. The NAD

+/NADH couple regulates cellular energy metabolism, glycolysis, and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. In contrast, NADP

+/NADPH maintains redox homeostasis and supports the biosynthesis of fatty and nucleic acids [

6]. Additionally, NAD

+ serve as a substrate for other NAD

+ consuming enzymes, including sirtuins and poly-(ADP-Ribose) polymerases (PARPs) [

7]. Sirtuins are NAD

+-dependent histone deacetylases, which regulate diverse cellular processes including cellular metabolism, mitochondrial homeostasis, autophagy, DNA repair, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response [

8,

9]. Whereas PARPs catalyze the covalent attachment of monomers or polymers of ADP-ribose units on a variety of amino acid residues on target proteins. PARPs play roles in DNA damage detection and repair, genomic stability, programmed cell death, and inflammation [

10,

11].

Individuals over 60 years of age account for 11% of world population in 2016 and it is projected to reach 22% by 2050 [

12]. In the aged population, a decline occurs in the NAD

+ level [

13,

14,

15]. In contrast, an enhancement occurs in the CD38 levels during aging [

16,

17], which may be associated with increased aging-related inflammation through a process called inflammaging [

18,

19]. Increased CD38 during aging leads to further NAD

+ depletion. Notably, decreased NAD

+ in the aging population affects many aging-associated immune dysfunctions, including mitochondrial dysfunction, intracellular accumulation of oxidative damaged macromolecules (DNA, lipids, and proteins), dysregulated energy metabolism, impaired cellular “waste disposal”, impaired adaptive stress response, compromised DNA repair, dysregulated neuronal Ca

2+ handling, stem cell exhaustion, and inflammation [

13]. Therefore, the decline of NAD

+ contributes to the pathogenesis of various of aging-associated diseases, including infection, neurodegenerative diseases [

13,

14,

15], cancer [

2], and type II diabetes [

2,

14,

20]. Hence, CD38 has become a therapeutic target for treating these aging-associated diseases [

1,

2,

3,

4,

13,

14,

21].

Aging is associated with development of many diseases, including periodontal disease, which is associated with comorbid systemic diseases, poor physical functioning, inflammatory dysregulation, and limited ability to self-care in frail older populations [

22]. A previous study [

23] showed that young mice do not develop measurable periodontal bone loss unless heavily infected with human periodontal pathogens. In contrast, old mice displayed significantly increased periodontal bone loss, accompanied by elevated expression of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-17A) and innate immune receptors involved in the induction or amplification of inflammation [including toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), CD14, CD11b, CD18, and complement C5a] [

23].

Oral bacterial pathogens, including

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (

Aa, a major oral pathogen associated with 90% of localized aggressive periodontitis and 30% to 50% of severe adult periodontitis [

24] and

Porphyromonas gingivalis (

Pg, another major oral pathogen in the initiation and development of severe forms of chronic periodontal disease [

25,

26]) activate TLRs and their downstream signaling pathways [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], including NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs [including extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 MAPK] [

32,

33], leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines [including IL-1β, IL-6, ΤNF-α, and receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL)] . These proinflammatory mediators subsequently cause periodontal tissue damage and alveolar bone loss.

Additionally, oral bacterial pathogens can modulate the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in specific cell types by activating NADPH oxidases (NOXs), which play roles in host defense to eliminate infected bacterial pathogens [

25,

26,

34,

35]. However, excessive ROS causes oxidative stress, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction in aging [

36]. The innate immune response also possesses many anti-oxidative enzymes, [including superoxide dismutase1 (Sod1), glutathione peroxidase 4 (Gpx4), Peroxiredoxin 1 (Prdx1), thioredoxin reductase 1 (Txnrd1), and catalase (Cat)], which reduce oxidative stress induced by bacterial pathogens [

6]. NADP

+/NADPH serve as coenzymes in the anti-oxidative response to maintain cellular redox homeostasis[

6,

37]. NAD

+ depletion with aging caused mitochondrial dysfunction, a decline in energy production and accumulation of ROS that produce high oxidative stress [

5].

A previous study [

16] showed that old (18-month-old) murine bone marrow-derived monocytes and macrophages (BMMs) displayed higher CD38 protein levels when stimulated by various doses (0.5 to 50 ng/ml) of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 20 h compared to young (3-month-old) mice controls. However, it was not clear if the enhanced CD38 levels in old murine BMMs were directly correlated to enhanced proinflammatory cytokine levels in old murine BMMs. Additionally, it was not clear if inhibition of CD38 by a CD38 specific inhibitor (78c) in old murine BMMs could attenuate proinflammatory cytokine levels, enhance NAD

+ expression, and reduce the oxidative stress induced by oral pathogens. In the present study, we first compared CD38 and NAD

+ levels in young vs. old murine BMMs with or without infection with the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg. Next, we determined if the CD38 protein expression was directly correlated with the activated NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein levels or the enhanced proinflammatory cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, ΤNF-α) levels in old murine BMMs when compared to young controls. Finally, we evaluated the effects of a CD38 specific inhibitor (78c) in CD38 and NAD

+ levels, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and oxidative stress in old murine BMMs induced by oral pathogens.

3. Discussion

Periodontitis is an inflammatory bone loss disease. Oral bacterial pathogens not only induce the generation of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, but also RANKL, the major osteoclast differentiation factor [

39]. RANKL binds with its receptor RANK, which promote osteoclast precursors (monocytes and macrophages) to differentiate and fuse to form multinucleated osteoclasts, leading to alveolar bone loss. In the current study, we demonstrated that old murine BMMs exhibited an abnormal immune response to infection with the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg, including a delayed activation of NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases, an enhanced CD38 expression, and a reduced NAD

+ expression compared with controls in young murine BMMs (

Figure 1,

Figure 2A&B). Our study is in accordance with a previous study [

16], which showed that old murine BMMs displayed higher CD38 protein expressions when stimulated by LPS for 20 h compared with young mice controls. Previously, Chini et al. [

40] showed that inducing senescence in human umbilical vain endothelial cells (HUVECs) by DNA damage through exposure to X-ray irradiation or gamma irradiation enhanced markers for senescence, including p21, p16

Ink4a, and PAI1. However, CD38 mRNA was not induced by these treatments [

40]. Instead, Chini et al. [

40] discovered that senescent cells induced by either X-ray irradiation or gamma irradiation secreted higher inflammatory cytokines, including IL6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant protein -1 (MCP1) than controls. When murine BMMs were incubated with conditioned media derived from senescent cells induced by either X-ray irradiation or gamma irradiation, the mRNA and protein levels of CD38 were induced [

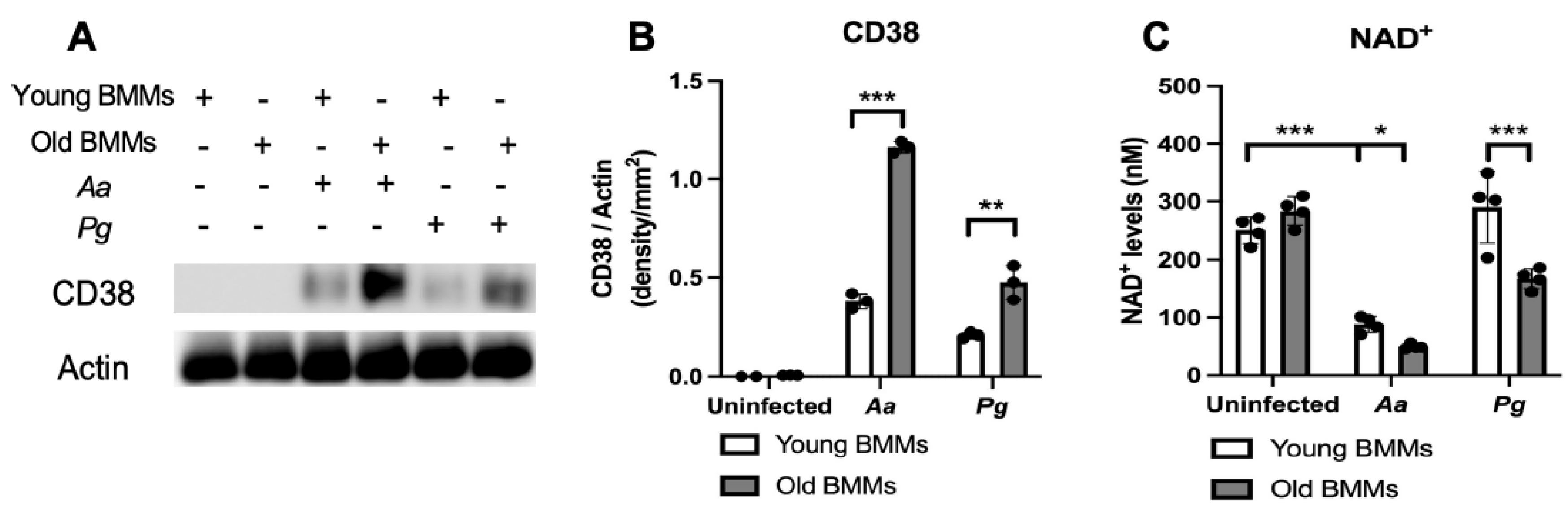

40]. In the current study, uninfected old murine BMMs and young murine BMMs expressed undetectable CD38 protein levels and similar NAD

+ levels (

Figure 1A-C). After infection with the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg for 24 h, CD38 protein levels were increased in both old and young murine BMMs (

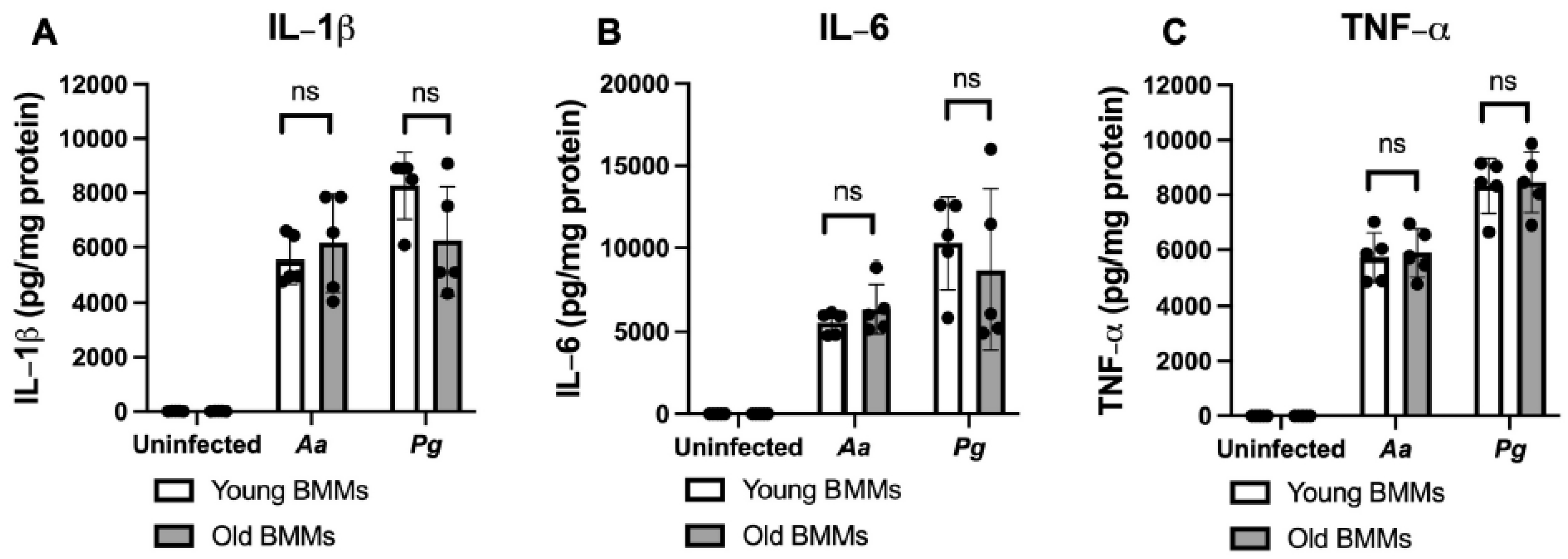

Figure 2A-C), supporting that CD38 is an inflammatory marker. However, we did not observe significant differences between the old murine BMMs and young murine BMMs in the activation of NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases or IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α cytokine expression 24 h after infection with

Aa or

Pg (

Figure 1C-H,

Figure 2A-C). This finding suggests that the high CD38 expression in old murine BMMs after infection with oral pathogens was not directly correlated with the activation of NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases nor the amount of pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) released in old murine BMMs.

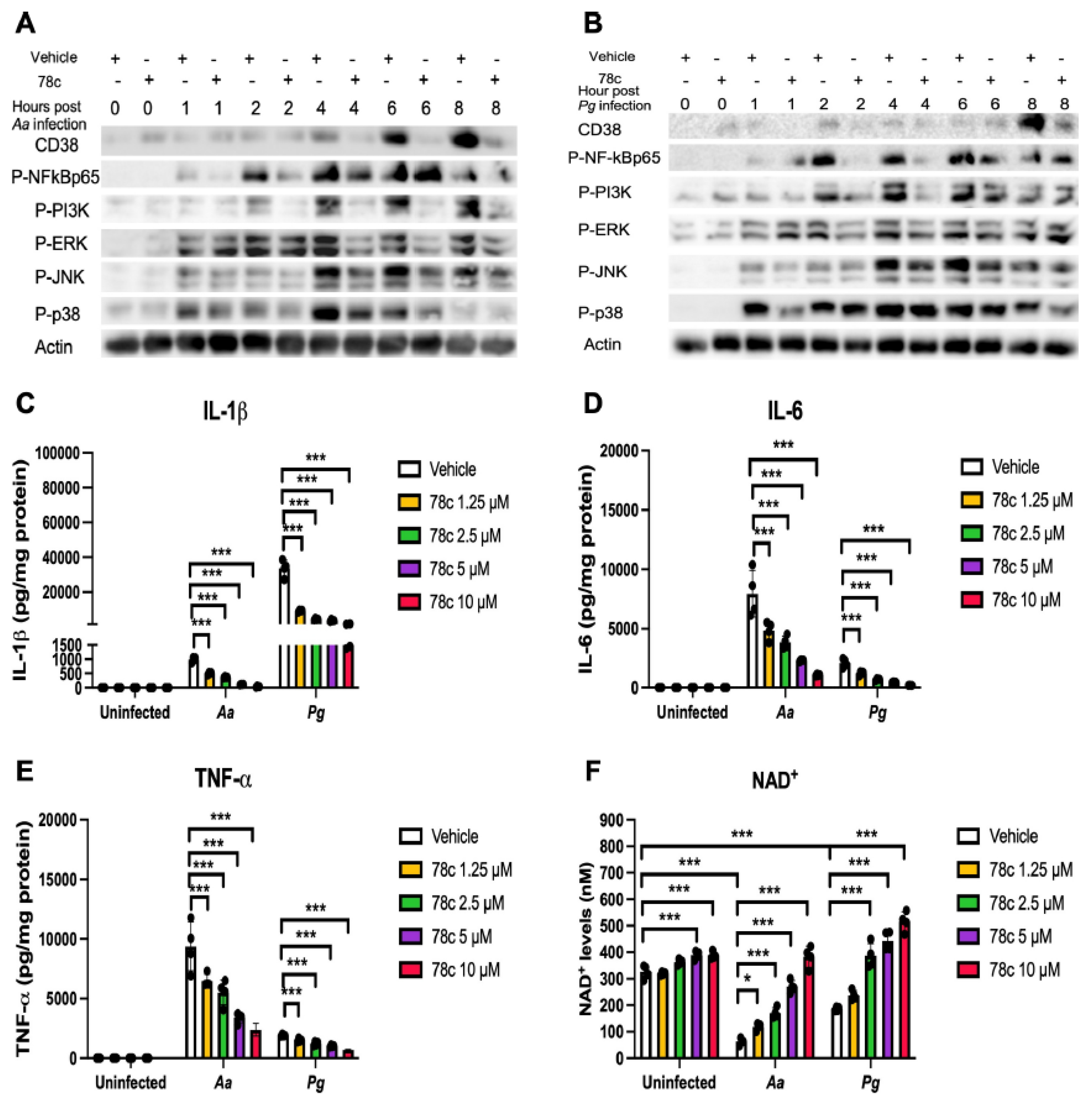

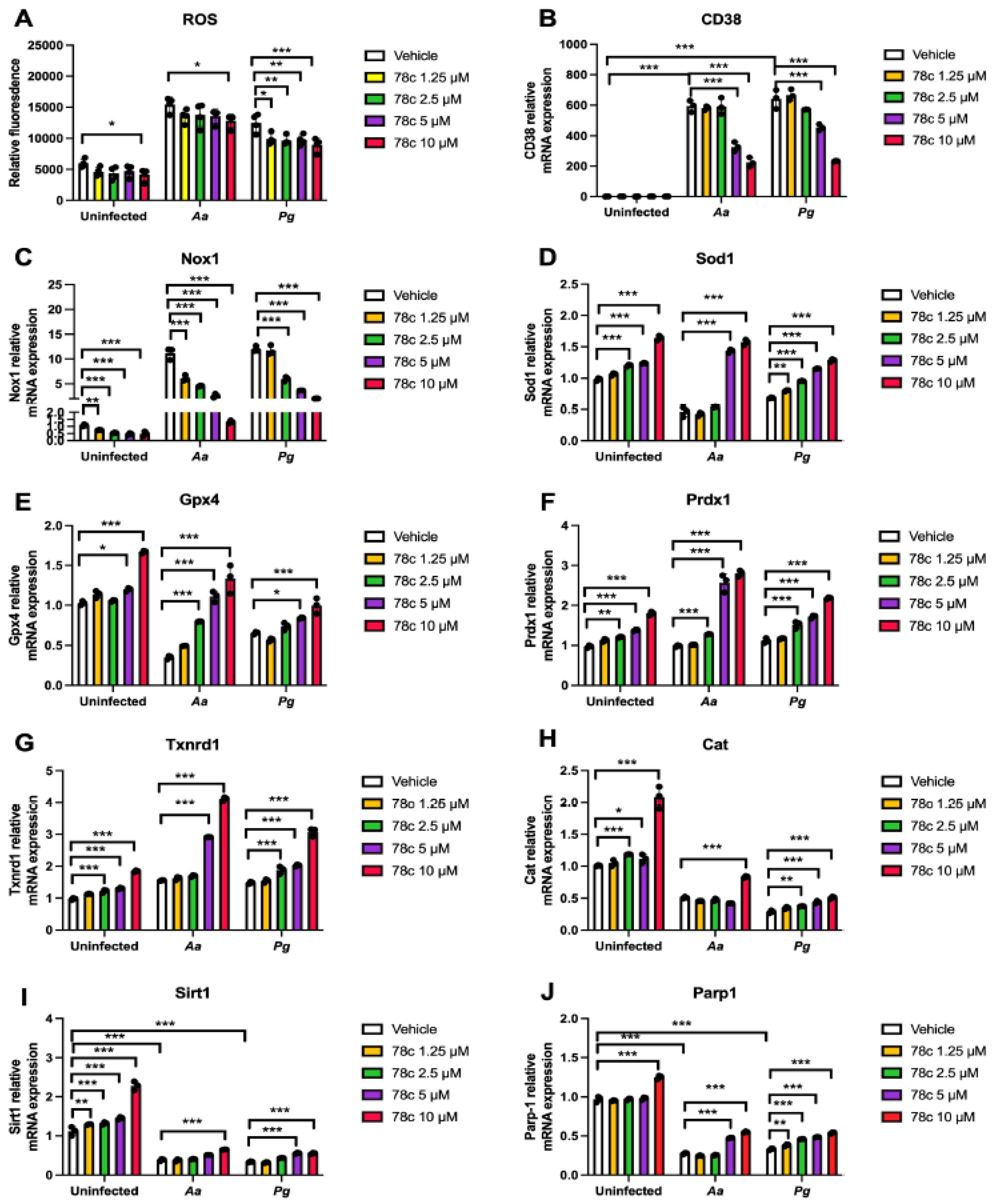

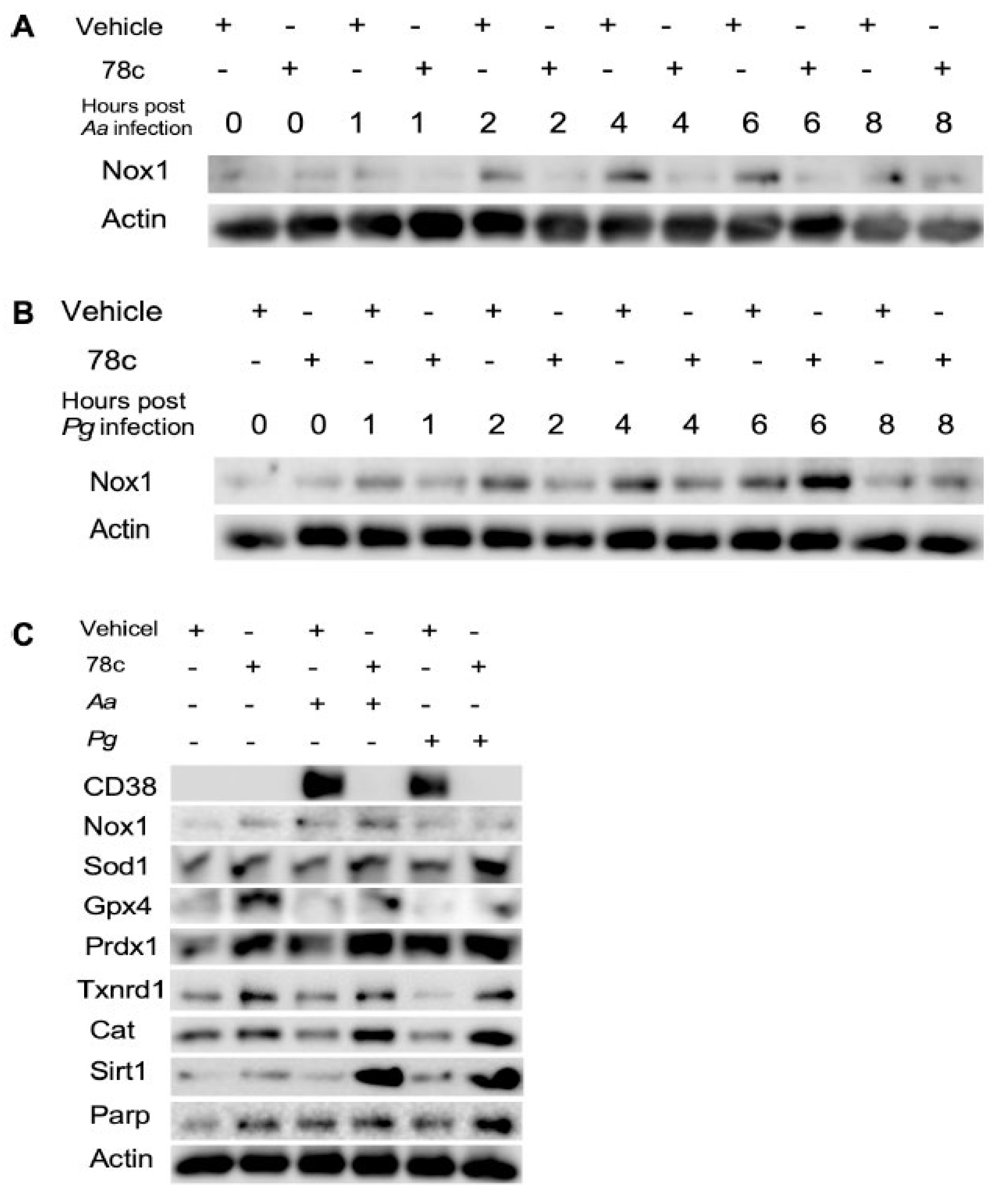

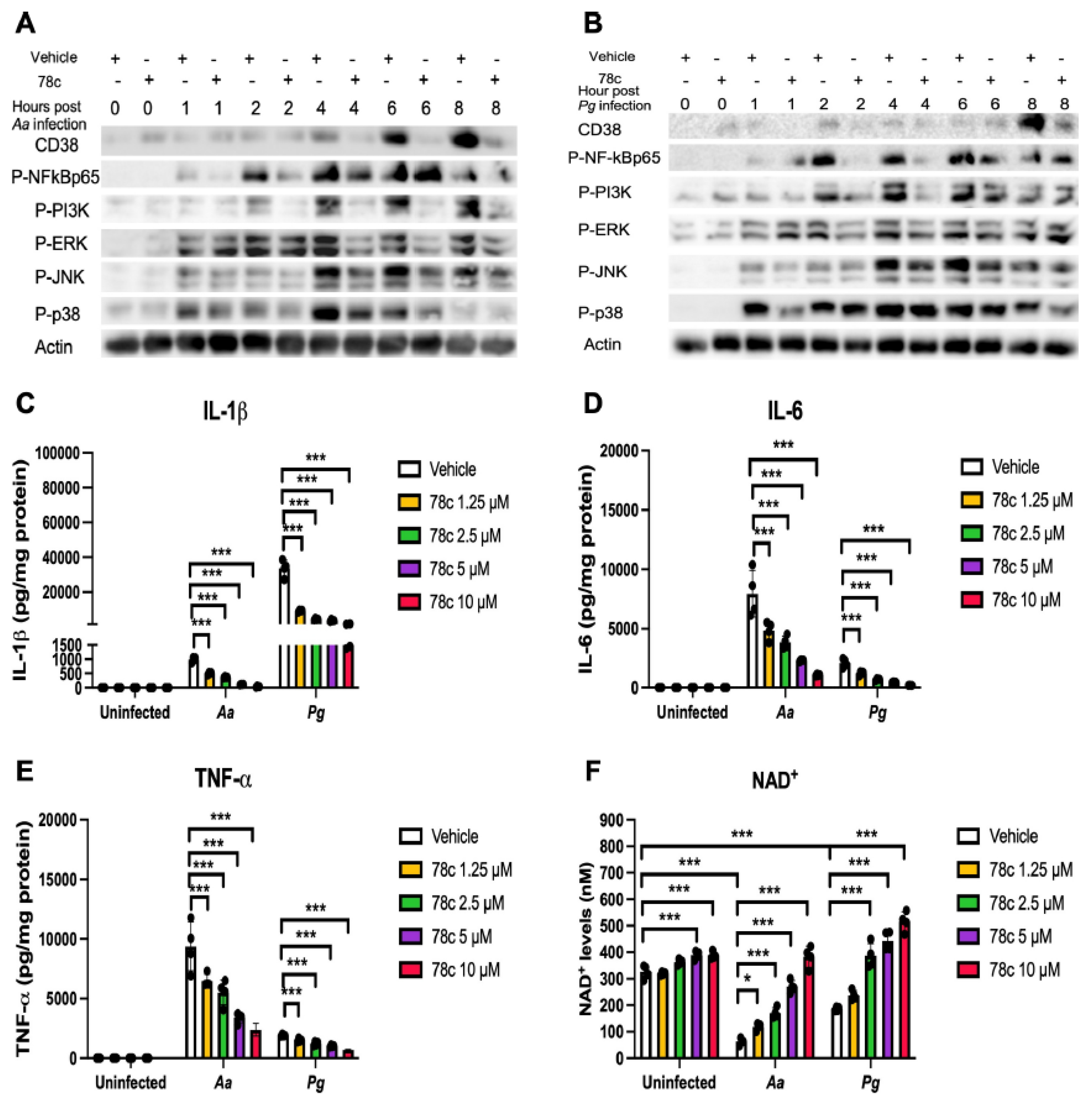

Our previous study [

38] demonstrated that treatment with 78c suppressed NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases induced by the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg in murine BMMs derived from TALLYHO/JngJ mice (type 2 diabetic mice). In accordance with our previous study, treatment with 78c also reduced the activation of NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases and attenuated the levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) that were induced by the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg in old murine BMMs (

Figure 4A-E). Because NADPH oxidase (Nox) activation is associated with sensing the molecular signatures of microbial pathogens by TLRs [

35] and ROS-mediated cellular signal pathways interplay with TLRs down-stream signaling pathways (including NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases) [

41], inhibition of NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases by 78c could reduce Nox1 expression induced by oral pathogens (

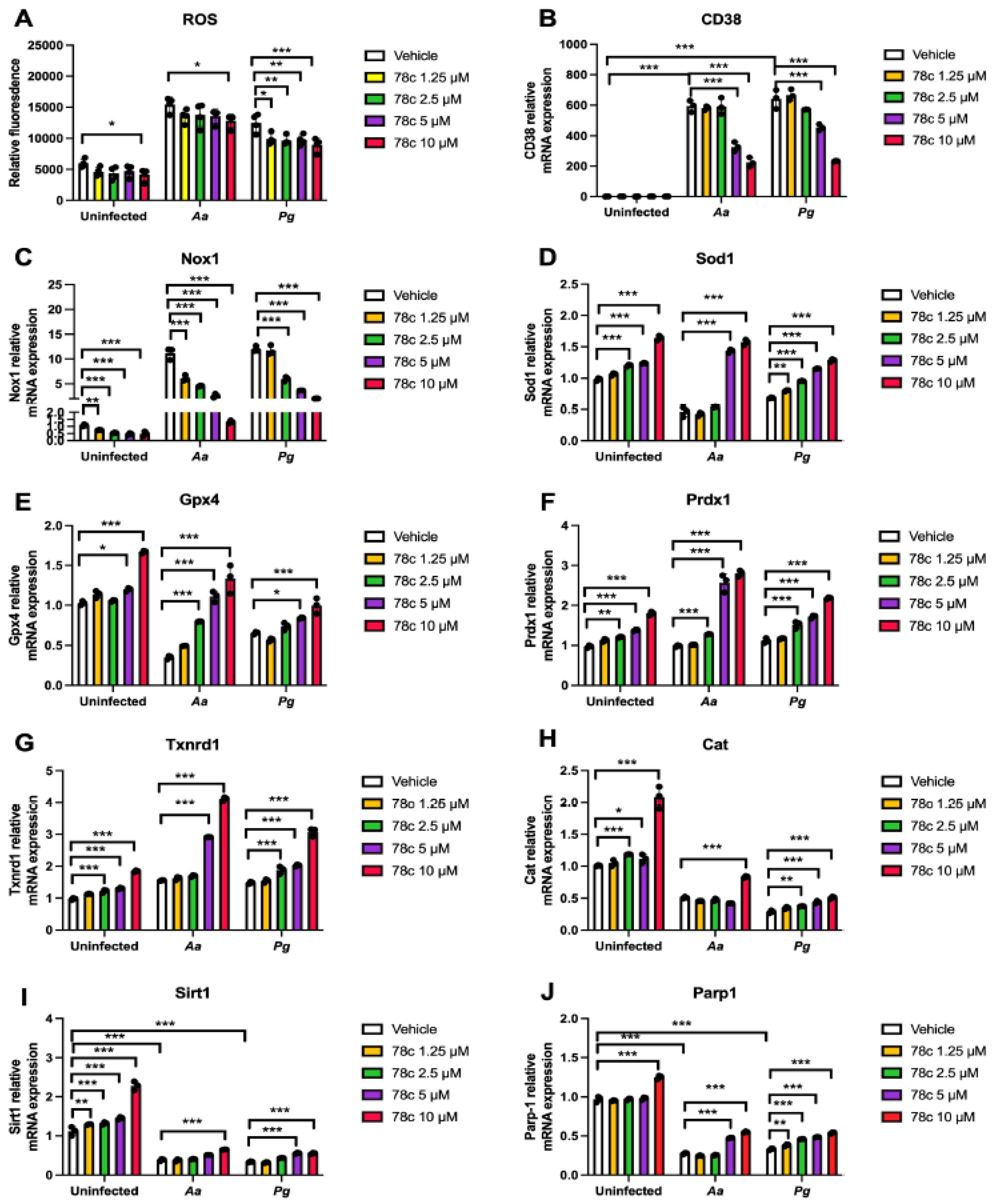

Figure 6A-B). The enhancement of anti-oxidant enzymes (including Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1,Txnrd1, and Cat) in murine BMMs treated with 78c (

Figure 5D-H,

Figure 6C) was caused by the increase of NAD

+ levels in 78c-treated cells (

Figure 4F). As NADPH/NADP

+ are involved in maintaining redox homeostasis by turning O

2- into H

2O

2 by Sod1 and subsequently turning H

2O

2 into H

2O by other anti-oxidant enzymes (including Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat) [

6,

37], inhibition of the degradation of NAD

+ by CD38 in 78c-treated murine BMMs could enhance NAD

+ and subsequently increase these anti-oxidant enzyme expressions. Our findings are in accordance with a prior study [

42], which demonstrated that inhibition CD38 by apigenin (a flavonoid with CD38 inhibitory activity) ameliorated oxidative stress by enhancing Sod and Gpx expressions in skeletal muscle of aged mice.

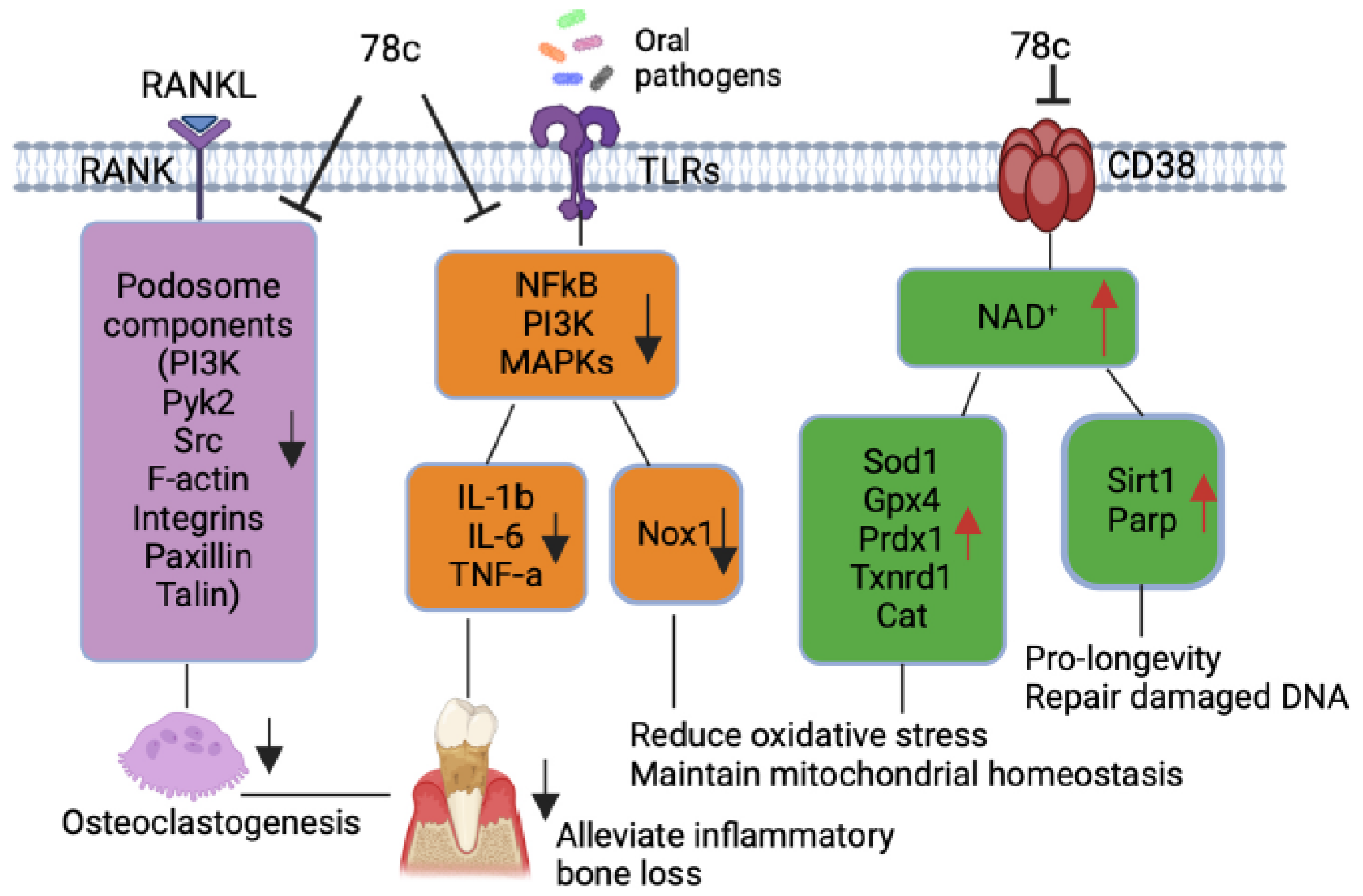

Additionally, our previous study [

38] demonstrated that treatment with 78c suppressed osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption induced by RANKL. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that treatment with 78c reduced podosome (basic cell adhesion unit) components, (including PI3K, Pyk2, Src, F-actin, integrins, paxillin, and talin) induced by RANKL. Treatment with 78c also attenuated osteoclastogenic factors, including the nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic calcineurin-dependent 1 (Nfatc1), cathepsin K (Ctsk), acid phosphatase 5 (Acp5), osteoclast stimulatory transmembrane protein (Ocstamp), and dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (Dcstamp), induced by RANKL. Therefore, treatment with 78c could potentially alleviate inflammatory bone loss in patients with periodontitis.

Previous studies [

9,

43] demonstrated that sirtuins play roles in extending the lifespan of organisms. Numerous studies reported that the SIR2, the first identified sirtuin protein in yeast, extended the lifespan in yeast [

44], C. elegans [

45], and Drosophila [

46]. The Sirt1 is the most studied and the mammalian closest ortholog to SIR2. Sirt1 expression declines with aging in animals and human tissues [

47]. In contrast, over-expression of Sir1 in the brain extended the lifespan of mice [

48]. Over-expression of Sirt1 in pancreatic β cells of mice also improved glucose tolerance and enhanced glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice at 3 to 8 m of age compared with controls [

49]. In the current study, treatment with 78c enhanced NAD

+ (

Figure 4F) and subsequently increased Sirt1 mRNA and protein expressions in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with oral pathogens (

Figure 5I and

Figure 6C), supporting that treatment with 78c is a promising therapeutic approach to treat aging-associated periodontitis, which can enhance NAD

+ and Sirt1, maintain mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolic function, and promote longevity. In response to the increase of NAD

+ in 78c-treated cells, we also observed enhanced Parp1 mRNA (

Figure 5J) and Parp protein levels (

Figure 6C) in old murine BMMs treated with 78c. This enhanced Parp could assist in repairing damaged DNA in cells. The Sirtuins and Parp can cleave NAD

+ and release nicotinamide (NAM) [

5,

37]. NAM can be recycled by

the enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT)

to

nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) and subsequently be synthesized to NAD

+ by NMN adenylyltransferases

(NMNATs) via the salvage pathway [

5,

37]. We observed that treatment with 78c (5 or 10 µM) displayed higher NAD

+ levels in old murine BMMs infected with

Pg compared with controls (

Figure 4F). This could be caused by enhanced Sirt1 and Parp levels in 78c-treated cells, which could in turn promote the regeneration of NAD

+ by the salvage pathway.

Previously, accumulated evidence suggests that NAD

+ levels decline with aging at a systemic level in diverse organisms, including rodents and humans, contributing to the development of many aging-associated diseases [

14,

50,

51]. These enhanced NAD

+ levels in the aging population are associated with chronic inflammation in aging patients, called inflammaging [

18,

19]. In the current study, the mice were bred in a specific pathogen-free condition, and the mice were relatively healthy without inflammation. Therefore, we did not detect CD38 protein levels in uninfected murine BMMs, and uninfected old murine BMMs expressed similar levels of NAD

+ compared with young controls. Because human bodies are exposed to varieties of pathogens and aging patients often have comorbidity with various chronic inflammation (including atherosclerosis, cardiovascular events, cancer, autoimmune diseases), aging patients could have high levels of CD38

+ and reduced levels of NAD

+ compared with young controls.

Scaling and root surface debridement are the traditional “gold standard” treatment for stage I-III periodontitis. There are still patients or sites that show poor response to non-surgical periodontal treatment and long-term supportive maintenance efforts. This could be due to sustained dysbiosis, bacteria invasion to periodontal tissues, or a non-resolving chronic inflammatory response. Previous studies [

52,

53] demonstrated that treatment with 78c in aged mice reversed age-related NAD

+ decline and increased lifespan and health span of naturally aged mice. Treatment with 78c improved several physiological and metabolic aging parameters, including glucose tolerance, muscle function, exercise capacity, and cardiac function in mouse natural and accelerated aging models [

52,

53]. Our previous study [

38] demonstrated that inhibition of CD38 by 78 attenuated IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokine expressions induced by the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg in murine BMMs derived from TALLYHO/JngJ mice (type 2 diabetic mice). Additionally, treatment with 78c reduced osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption induced by RANKL (

Figure 7) [

38]. In the current study, we also showed that treatment with 78c in old murine BMMs inhibited NF-κB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases as induced by the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg, and subsequently alleviated IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokine expressions, and Nox1 mRNA and protein expressions. Additionally, treatment with 78c suppressed CD38 and enhanced NAD

+ levels, and subsequently increased the mRNA and protein levels of anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1,Txnrd1, and Cat) in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with the oral pathogens

Aa or

Pg. Our and other peoples’ studies support that inhibition of CD38 by 78 could serve as an adjunctive therapy for aging-associated periodontitis to inhibit periodontal inflammation, attenuate osteoclastogenesis and alveolar bone resorption, alleviate oxidative stress, and prolong the health span of human beings.

The current study has some limitations. Although we showed that old murine BMMs displayed higher CD38 protein levels after infection with the oral pathogens Aa or Pg, it was not clear about the mechanisms that were associated with the increase of CD38 in old murine BMMs. Future studies should determine why old murine BMMs express higher CD38 compared to young controls after bacterial infection. Additionally, aging patients have various age-associated diseases (including atherosclerosis, neurodegenerative diseases, autoimmune diseases, and type II diabetes). We only determined CD38 expression in response to the oral pathogens Aa or Pg infection. Future studies should determine if old murine BMMs displayed higher CD38 in response to other stimuli and if inhibition of CD38 by 78c could reduce CD38, alleviate inflammation, and reduce oxidative stress induced by other stimuli. Furthermore, since we only conducted in vitro studies, future in vivo studies need to determine if treatment with 78c could alleviate periodontal inflammation, attenuate alveolar bone loss, and reduce oxidative stress in old animals with periodontitis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals, and Reagents

Old (18-month-old) and young (2-month-old) male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Young female and male mice were bred to generate 2 to 3-month-old young control mice. Mice were housed under a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle in specific pathogen-free conditions and had free access to food and water. All animal-related work was conducted in accordance with the guidelines laid down by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States regarding the usage of animals for experimental procedures and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical University of South Carolina (IACUC-2021-01287). 78c was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN, USA), dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as a 10 mM stock solution, and stored at −20 °C. An equal volume of DMSO (as compared to 10 mM 78c) was diluted in cell culture media and served as a vehicle control.

4.2. Generation of L929 Conditioned Media

L929 (mouse fibroblast cell line) was purchased from the American Type Cell Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). L929 cells (5 × 105) were plated in a T75 flask and cultured for six days in 30 mL of Dulbeco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cell culture media was filtered through a 0.22 μM filter, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C as L929 conditioned media (containing macrophage colony-stimulating factor, M-CSF).

4.3. Generation of Bone Marrow-Derived Monocytes and Macrophages (BMMs)

Murine bone marrow cells were harvested from old (18-month old) or young (2- to 3-month-old) male C57BL/6J mice by flushing bone marrow cells from the tibia and femur using 10 mL cell culture media with a 10 mL syringe and 27 gauge needle (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA). The cell culture media is complete minimal essential media (MEM)-α (ThermoFisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. To remove tissue debris, the bone marrow cells were filtered through a 40 μM nylon cell strainer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Then, murine bone marrow cells were cultured in a complete MEM-α media supplement with 20% L929 conditioned media for three days. The attached bone marrow-stromal cells were discarded. The suspended bone marrow cells were transferred to new cell culture plates and cultured in complete MEM-α media supplement with 20% L929 conditioned media for another seven days until cells were differentiated into attached BMMs. Previous studies [

54,

55] showed that the adherent bone marrow-derived macrophages were usually better than 90% pure using macrophage markers such as CD11b and F4/80. One day before infection, the attached murine BMMs were lifted by treating with 10 mM EDTA and were plated in new cell culture dishes in MEM-α media with 5% FBS and 20% L929 conditioned media without antibiotics.

4.4. Bacterial Culture

Oral bacterial pathogens

Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (

Aa, ATCC 43718) and

Porphyromonas gingivalis (

Pg, ATCC 33277) were originally obtained the American Type Culture Collection.

Aa was cultured in brain–heart infusion broth (Fisher Scientific, Suwanee, GA, USA) at 37 °C with 10% CO

2.

Pg was cultured to the early exponential phase in tryptic soy broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with yeast extract (Becton Dickinson, 1 mg/mL), menadione (Chem-Implex Int’l Inc., Wood Dale, IL, USA, 1μg/mL), and hemin (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, 5 μg/mL) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions and harvested as previously described [

26,

56,

57]. Briefly, the cell pellets of

Pg or

Aa were washed and resuspended with PBS before infection.

Pg concentration was determined using a Klett-Summerson photometer (Bel-Art, Wayne, NJ, USA), followed by serial dilution and plating on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with yeast extract (Becton Dickinson, 5 mg/mL), menadione (Chem-Implex Int’l Inc., Wood Dale, IL, USA, 1μg/mL), hemin (Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, 5 μg/mL), and sheep blood (Hemostat Laboratories, Dixon, CA) at 37 °C under anaerobic conditions. The K value 1.0 was equal to about 1.0 × 10

9 CFU/mL of

Pg.

Aa bacterial concentration was determined by measuring bacterial optical density at 600 nm followed by serial dilution and plating on brain heart infusion agar plates (Fisher Scientific). OD

600 = 1 was equal to about 3 × 10

8 CFU/mL of

Aa. Agar plate counts (CFU/mL) were used for both bacteria to calculate the multiplicity of infection (MOI), and MOI 20 was used for

Pg or

Aa infection of murine BMMs to detect noticeable cytokine expressions in the BMMs. A control group of cells were not infected with bacteria.

4.5. NAD+ Assay

The NAD+ levels were determined using a NAD+/NADH cell-based assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The NAD+ levels were calibrated by cell growth and viability determined using a CellTiter 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA).

4.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

IL-1β levels in cell lysates, IL-6, and TNF-α protein levels in cell culture media of BMMs were quantified using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The concentration of cytokines was normalized by protein concentration, which was determined using a DC protein Assay Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) in cell lysates (100 μL RIPA cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA)/well in a 12-well cell culture plate).

4.7. RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

According to the manufacturer’s instructions, total RNA was isolated from murine bone marrow cells using TRIZOL (ThermoFisher Scientific). Complementary DNA was synthesized using a TaqMan reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using the total RNA (1 μg). Real-time PCR was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies). PCR conditions used were as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. The following amplicon primers were obtained from Life Technologies: CD38 (Mm00483143_m1), Nox1 (Mm00549170_m1), Sod1 (Mm01344233_g1), Gpx4 (Mm04411498_m1), Prdx1(Mm01621996_s1), Txnrd1 (Mm00443675_m1), Cat (Mm00437992_m1), Sirt1 (Mm01168521_m1), Parp1 (Mm01321084_m1), and β-actin (Mm02619580_g1). Amplicon concentration was determined using threshold cycle values compared with standard curves for each primer. Sample mRNA levels were normalized to an endogenous control β-actin expression and were expressed as fold changes compared with control groups.

4.8. Western Blot Analysis

Per the manufacturer’s guidance, protein was extracted from murine BMMs using a RIPA cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Total protein (25 μg) was loaded on 10% Tris-HCl gels, electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The antibodies to CD38, p-PI3K, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, p-NF-κB p65, Sod1, Gpx4, Trdx1,Txnrd1(Trxr1), Cat, Sirt1, Parp, and pan-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). An antibody to Nox1 was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All primary antibodies were diluted in ratios of 1:500 or 1:1000. After washing, the nitrocellulose membranes were incubated at room temperature for one hour with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology) and developed using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific). Digital images and protein densitometry were analyzed with a G-BOX chemiluminescence imaging system (Syngene, Frederick, MD, USA).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were checked for normality using a QQ plot. The data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s or Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests. All statistical tests were performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 10.4.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Values are expressed as means ± standard error of the means (SEM) of three independent experiments. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered significant.

Figure 1.

Old murine BMMs exhibited significantly higher CD38 protein and lower NAD+ expressions after infection with either Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) than young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg (MOI 20) for 24 h. (A) Protein levels of CD38 and pan-actin in cell lysate were determined by Western Blot. (B) Protein densitometry of CD38 were quantified compared with control actin expression (n=3). (C) NAD+ levels in murine BMMs with or without bacterial infection (n=4). Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Old murine BMMs exhibited significantly higher CD38 protein and lower NAD+ expressions after infection with either Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) than young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg (MOI 20) for 24 h. (A) Protein levels of CD38 and pan-actin in cell lysate were determined by Western Blot. (B) Protein densitometry of CD38 were quantified compared with control actin expression (n=3). (C) NAD+ levels in murine BMMs with or without bacterial infection (n=4). Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Old murine BMMs displayed delayed immune responses to infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) compared to young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 1 to 24 h. (A) Protein levels of CD38, p-NFκBp65, p-PI3K, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, and pan-actin in cell lysate were determined by Western Blot. Protein densitometry of p-NFκBp65 (D), p-PI3K (E), p-ERK (F), p-JNK (G), and p-p38 (H) 24 h after bacterial infection were evaluated. Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (n=3, ns: no significance).

Figure 2.

Old murine BMMs displayed delayed immune responses to infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) compared to young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 1 to 24 h. (A) Protein levels of CD38, p-NFκBp65, p-PI3K, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, and pan-actin in cell lysate were determined by Western Blot. Protein densitometry of p-NFκBp65 (D), p-PI3K (E), p-ERK (F), p-JNK (G), and p-p38 (H) 24 h after bacterial infection were evaluated. Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (n=3, ns: no significance).

Figure 3.

Old murine BMMs displayed similar IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α cytokine levels 24 h after infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) compared to young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg (MOI 20) for 24 h. Cytokine levels of IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), and TNF-α (C) were quantified by ELISA and calibrated by protein expression in cell lysate. Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (n=5, ns: no significance).

Figure 3.

Old murine BMMs displayed similar IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α cytokine levels 24 h after infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) compared to young controls. Young and old murine BMMs were either uninfected or infected with an oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg (MOI 20) for 24 h. Cytokine levels of IL-1β (A), IL-6 (B), and TNF-α (C) were quantified by ELISA and calibrated by protein expression in cell lysate. Statistics were analyzed by ordinary one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (n=5, ns: no significance).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c suppressed CD38, NFκB, PI3K, and MAPKs; attenuated IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokine levels; and enhanced NAD+ in old murine BMMs after infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (10 µM) with or without infection with the oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 1 to 8 h. Protein levels of CD38, p-NFκBp65, p-PI3K, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, and pan-actin in cell lysate induced by Aa (A) or Pg (B) were determined by Western Blot. Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle (diluted DMSO) or 78c (1.25 to 10 µM) with or without infection of Aa or Pg for 24 h. Cytokine levels of IL-1β (C), IL-6 (D), and TNF-α (E) were quantified by ELISA and calibrated by protein expression in cell lysate. (F) NAD+ levels were measured and calibrated by cell growth and viability. Statistics were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n=4, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c suppressed CD38, NFκB, PI3K, and MAPKs; attenuated IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α pro-inflammatory cytokine levels; and enhanced NAD+ in old murine BMMs after infection with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (10 µM) with or without infection with the oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 1 to 8 h. Protein levels of CD38, p-NFκBp65, p-PI3K, p-ERK, p-JNK, p-p38, and pan-actin in cell lysate induced by Aa (A) or Pg (B) were determined by Western Blot. Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle (diluted DMSO) or 78c (1.25 to 10 µM) with or without infection of Aa or Pg for 24 h. Cytokine levels of IL-1β (C), IL-6 (D), and TNF-α (E) were quantified by ELISA and calibrated by protein expression in cell lysate. (F) NAD+ levels were measured and calibrated by cell growth and viability. Statistics were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (n=4, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Nox1, but enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat), Sirt1, and Parp1 mRNA levels in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (1.25 to 10 µM) with or without infection with either the oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 24h (ROS study) or 8 h (RT-qPCR study). (A) ROS was detected by measuring fluorescence in cells using a CellROXTM Green reagent and calibrated by cell growth and viability (n=4). (B) CD38 mRNA, (C) Nox1 mRNA, (D) Sod1 mRNA, (E) Gpx4 mRNA, (F) Prdx1 mRNA, (G) Txnrd1 mRNA, (H) Cat mRNA, (I) Sirt1 mRNA, and (J) Parp1 mRNA levels were quantified using RT-PCR and normalized by β-actin expression (n=3). Statistics were analyzed using an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and Nox1, but enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat), Sirt1, and Parp1 mRNA levels in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with either the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (1.25 to 10 µM) with or without infection with either the oral bacterial pathogen Aa or Pg for 24h (ROS study) or 8 h (RT-qPCR study). (A) ROS was detected by measuring fluorescence in cells using a CellROXTM Green reagent and calibrated by cell growth and viability (n=4). (B) CD38 mRNA, (C) Nox1 mRNA, (D) Sod1 mRNA, (E) Gpx4 mRNA, (F) Prdx1 mRNA, (G) Txnrd1 mRNA, (H) Cat mRNA, (I) Sirt1 mRNA, and (J) Parp1 mRNA levels were quantified using RT-PCR and normalized by β-actin expression (n=3). Statistics were analyzed using an ordinary one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c inhibited Nox1, but enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat), Sirt1, and Parp1 protein levels in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (10 µM) with or without infection of either of the oral bacterial pathogens Aa or Pg for various time points (1, 2, 4, 8, or 24h. Nox1 and pan-actin protein expressions in old murine BMMs infected with Aa (A) or Pg (B) were evaluated by Western blot. CD38, Nox1, Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, Cat, Sirt1, Parp, and pan-actin protein expression (C) in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with Aa or Pg for 24h were evaluated by Western blot.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of CD38 by 78c inhibited Nox1, but enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat), Sirt1, and Parp1 protein levels in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with the oral pathogens Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa) or Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg). Old murine BMMs were treated with vehicle or 78c (10 µM) with or without infection of either of the oral bacterial pathogens Aa or Pg for various time points (1, 2, 4, 8, or 24h. Nox1 and pan-actin protein expressions in old murine BMMs infected with Aa (A) or Pg (B) were evaluated by Western blot. CD38, Nox1, Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, Cat, Sirt1, Parp, and pan-actin protein expression (C) in old murine BMMs either uninfected or infected with Aa or Pg for 24h were evaluated by Western blot.

Figure 7.

Roles of a CD38 inhibitor (78c) in treating aging-associated with periodontitis. Treatment with 78c suppressed podosome component (PI3K, Pyk2, Src, F-actin, integrins, paxillin, and talin) expressions, subsequently inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Treatment with 78c inhibited NFκB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases induced by oral bacterial pathogens, suppressing IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and inflammation. Treatment with 78c reduced Nox1 expression, increased NAD+, and enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat) expression, subsequently reduce oxidative stress and maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. Treatment with 78c increased NAD+ consuming enzymes (Sirt1 and Parp) expressions, which subsequently promote longevity and the repair of DNA damages.

Figure 7.

Roles of a CD38 inhibitor (78c) in treating aging-associated with periodontitis. Treatment with 78c suppressed podosome component (PI3K, Pyk2, Src, F-actin, integrins, paxillin, and talin) expressions, subsequently inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. Treatment with 78c inhibited NFκB, PI3K, and MAPKs protein kinases induced by oral bacterial pathogens, suppressing IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and inflammation. Treatment with 78c reduced Nox1 expression, increased NAD+, and enhanced anti-oxidant enzymes (Sod1, Gpx4, Prdx1, Txnrd1, and Cat) expression, subsequently reduce oxidative stress and maintain mitochondrial homeostasis. Treatment with 78c increased NAD+ consuming enzymes (Sirt1 and Parp) expressions, which subsequently promote longevity and the repair of DNA damages.