1. Introduction

Recently, dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs) have been the subject of numerous studies in the field of creating photoelectronic devices, since they are characterized by a significantly lower cost compared to traditional solar cells, ease of manufacture, and environmentally friendly production technology [

1]. At the same time, organic dyes are superior to organometallic ones due to their biodegradability, low cost, ease of production and purification, high molar extinction coefficient, and the possibility of molecular design [2-6].

Recent studies show that the best DSSCs based on metal-free organic dyes exhibit an energy conversion efficiency of 15.2% [

7].

As is known, the efficiency of solar cells is determined by the molecular structure of the dye, which is a π-conjugated system with terminal electron-donating and electron-accepting fragments [

8]. Many strategies have been considered in the literature to design highly efficient organic dyes depending on many factors such as planarity and rigidity of donors and acceptors, bond type, conjugation length, and side chains [

9,

10,

11,

12,

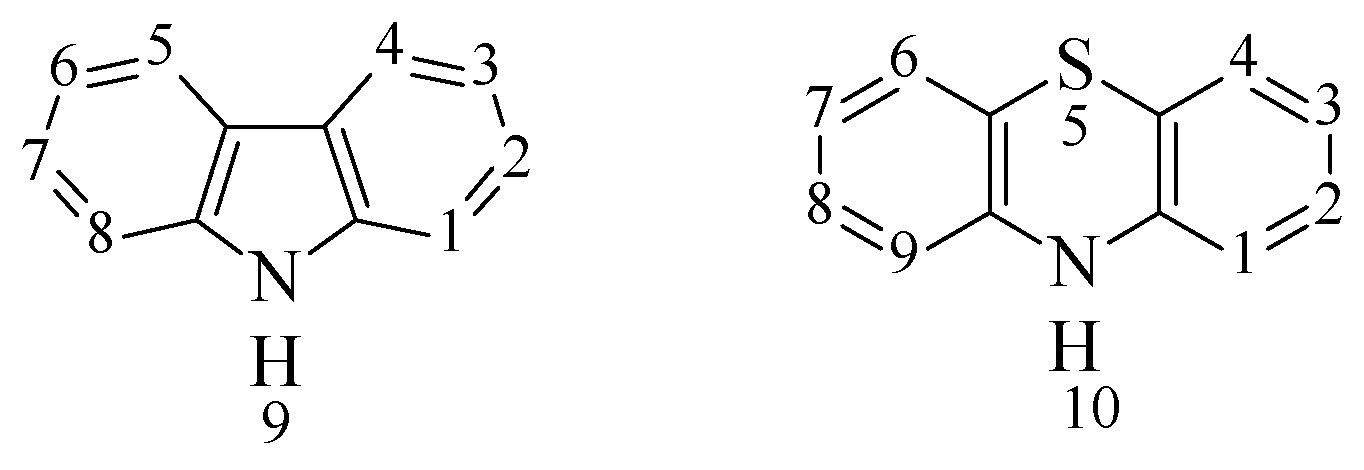

13]. Therefore, researchers face a significant challenge in designing electron donor moieties capable of highly efficient electron transfer and inhibition of molecular aggregation. In light of the previous considerations, phenothiazine (PTZ) and carbazole (CZ) are considered as effective options for donors (

Figure 1) [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

The introduction of carbazole and phenothiazine fragments into the structure of organic dyes is justified by their chemical stability and resistance to environmental influences. Substitution of hydrogen atoms at the nitrogen atom occurs easily, which makes it possible to improve solubility and adjust optical and electrical properties by introducing substituents. Carbazole and phenothiazine can be substituted at the 3rd and 6th or 7th atoms to form 3,6- or 3,7-disubstituted derivatives, respectively, which is used to bind to other aromatic fragments either directly or through various π-conjugated bridges. The advantage of carbazole is that new synthetic methods now allow obtaining compounds in which carbazole fragments are included in the structure of the compound due to the participation of different carbon atoms and the nitrogen atom of the carbazole cycle: 2C-7C, 1C-8C, 9N-2C, 9N-3C, which changes the optical and electrochemical properties of the resulting compound over a wide range [19-21]. In addition, the structure of carbazole contains a diphenyl fragment, which makes the molecule flat and rigid. This structure promotes more efficient intramolecular charge transfer, which leads to high mobility of charge carriers. Phenothiazine, due to the presence of two electron-saturated heteroatoms (nitrogen and sulfur), has stronger electron-donor properties compared to carbazole. In addition, the introduction of this fragment into the structure of the compound prevents the formation of excimers (dimers in the excited state) that arise as a result of the interaction of excited and unexcited molecules and lead to a decrease in the fluorescence quantum yield [

22]. This is explained, first of all, by the non-planar structure of the phenothiazine molecule, which has a butterfly conformation, in which the angle between the two benzene rings is 27.36 (9) [

23]. The difference in planarity when comparing CZ with PTZ can be useful from different points of view. The planar structure of CZ increases the degree of conjugation and the ability to transfer electrons, which can increase the photocurrent [

24]. The non-planar PTZ block (butterfly-like skeletons) can prevent π-stacking aggregation [

25,

26]. Meanwhile, the addition of long alkyl chains such as 2-ethylhexyl group to the nitrogen atoms in the structures plays a role in creating steric hindrance and then inhibiting the aggregation of molecules [

27].

The introduction of a carbazole or phenothiazine moiety has different effects on the optical, physical, physicochemical and electrochemical properties of the compounds, which in turn determines the nature and efficiency of photoelectronic devices. Below is a review demonstrating a comparative analysis of compounds containing electron-donating carbazole and phenothiazine moieties in their structure, used as materials for dye-sensitized solar cells.

In order to determine the relationship between the structure of dyes, their properties and the efficiency of the device, a description of the structure of DSSCs and their operating principle is presented below.

The cells consist of two electrodes and an iodine-containing electrolyte. One electrode usually consists of a mesoporous dye-saturated oxide semiconductor (TiO

2/ ZnO/ NiO) deposited on a transparent conductive substrate. The other electrode is a conductive glass plate onto which a reduction catalyst is deposited—metallic platinum or graphite [

28]. The advantages of using TiO

2 for the production of solar cells, compared to other materials, are chemical resistance, non-toxicity, and low cost of the oxide. Its feature is significant photoactivity, as well as a pronounced dependence of electrical properties on the surface morphology and type of crystal lattice. The band gap for TiO2, which does not absorb visible light, is 3.2 eV [

29].

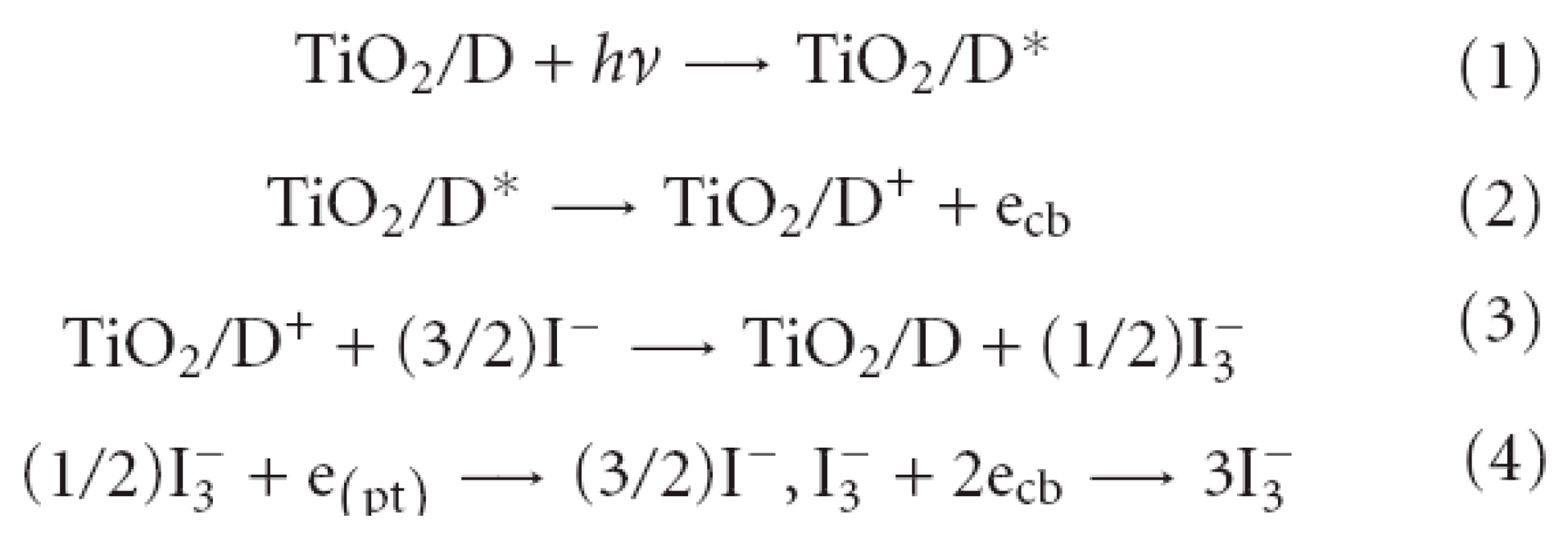

Figure 2 shows the operating principle of the cell [

30].

Light absorption occurs due to a monolayer of dye (D), chemically adsorbed on the surface of a semiconductor (e.g. TiO2) (1). After excitation by a light photon, the dye (D*) gives up an electron to the semiconductor (TiO2) (2), i.e. it passes into the conduction band of TiO2. The transition occurs very quickly and takes 10-15 s. In the semiconductor, the electron diffuses through the TiO2 film and reaches the glass electrode. The dye molecule is oxidized with the loss of an electron (D+). The dye molecule is restored to its original state by receiving an electron from the iodide ion (3), turning it into an iodine molecule, which in turn diffuses to the opposite electrode, receives an electron from it and again becomes a triiodide anion (4), which diffuses back to the photocathode, closing the circuit. According to this principle, a dye-sensitized solar cell converts solar energy into electric current flowing through an external conductor [30, 31]. To prevent liquid from leaking out during operation of the device, the cell is made hermetically sealed [31, 32]. An analysis of the literature covering research in the field of dye-sensitized solar cells [28, 33-35] allows us to formulate a number of basic requirements for organic dyes, the fulfillment of which is necessary to achieve high efficiency of DSSCs.

It is believed that the sensitizer for DSSCs should have a high molar absorption coefficient (ε), which characterizes how strongly a substance absorbs light at a given wavelength.

To ensure a high electron transfer rate, efficient conjugation of the donor and acceptor groups is necessary, and it is also important that the LUMO energy of the dye molecule is higher than the LUMO energy of TiO

2. This will allow the HOMO electrons of the dye molecule to move to the LUMO orbital of the semiconductor (TiO

2) rather than the dye when absorbing light quanta. The LUMO energy level is defined as the difference between the oxidation potential (E

ox) and the band gap (E

gopt), while it is worth noting that for TiO

2 this value is -0.5 V vs. NHE [

36].

The photosensitizer (dye) in the oxidized state should be easily reduced by the electrolyte used (pair I3-/I-), i.e. the oxidation potential of the dye should be greater than the oxidation potential of the electrolyte (Eox (I3-/I-) = 0.4 V).

It is better for the dye to be covalently bound to the semiconductor surface, thus the presence of “anchor” acid groups in its molecule is necessary;

One of the factors causing a decrease in the energy conversion efficiency of many organic dyes in DSSCs is the formation of dye aggregates on the semiconductor surface. This affects light absorption due to the internal filter effect. Therefore, to obtain optimal solar cell performance, it is necessary to avoid aggregation of organic dyes by structurally modifying the photosensitizer.

Another important aspect when using organic dyes is their stability, which is usually lower than that of metal complexes. This is due to the formation of an excited triplet state and the formation of unstable radicals. The dye must be resistant to side photochemical and electrochemical processes; have noticeable thermal stability (withstand about 108 cycles of device operation).

The efficiency of using the approach described above is demonstrated below using examples of compounds containing carbazole and phenothiazine fragments and which are structural analogues of each other.

2. D-π-A Type Organic Dyes

The D-π-A configuration is the most popular structure for organic dyes in DSSCs, which facilitates charge separation and transfer.

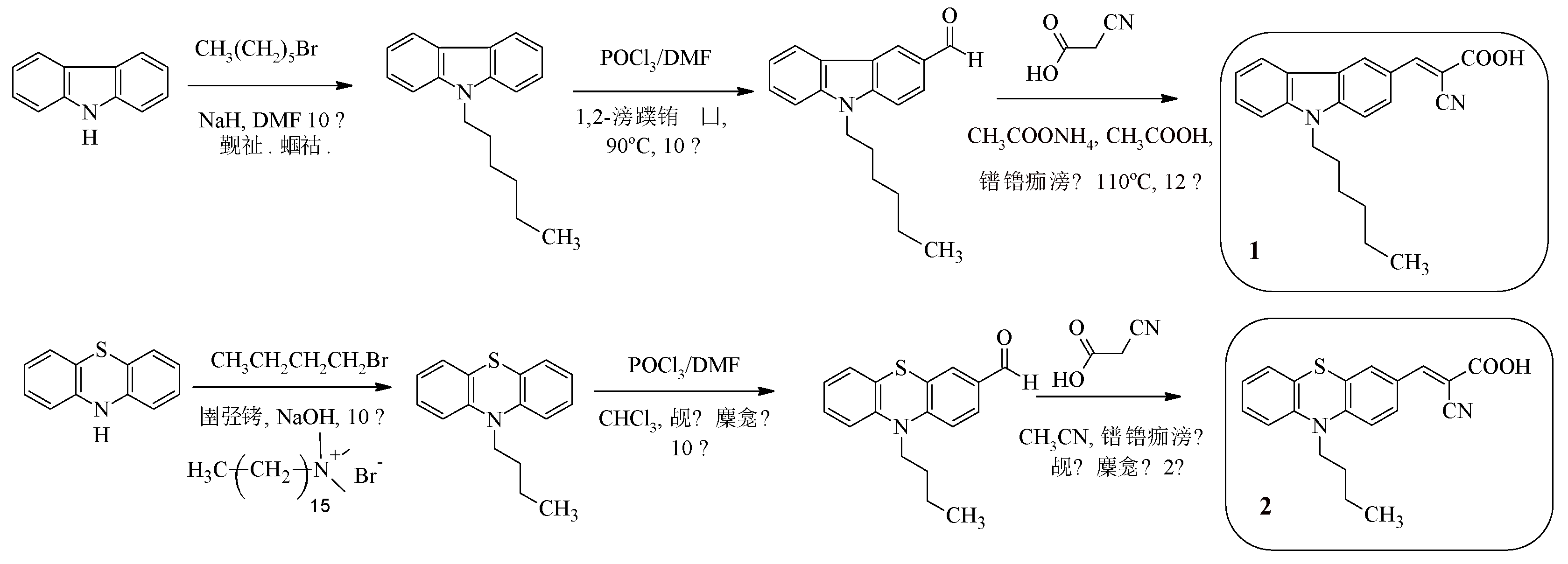

For example, compounds 1, 2 (

Scheme 1) contain alkyl chains in their composition in order to increase the solubility of the compounds, as well as to prevent dye aggregation.

The electron-withdrawing fragment of cyanoacrylic acid acts as an “anchor” group [37, 38]. Compounds 1, 2 differ from each other in the nature of the electron-donating fragment.

The synthesis of D-A dyes 1, 2 is a sequential implementation of three reactions - N-alkylation, formylation and the Knoevenagel reaction (

Scheme 1).

The photophysical properties of compounds 1, 2 are presented in

Table 1.

Compound 2, containing a phenothiazine fragment, absorbs in a longer-wavelength region of the spectrum compared to the carbazole-containing compound 1, which, in turn, leads to a decrease in the value of the band gap (1: Egopt = 2.88 eV, 2: Egopt = 2.37 eV).

It was found that the wavelength of the absorption maximum for dyes 1, 2 adsorbed on the titanium dioxide surface undergoes either a bathochromic shift (1: 33 nm) or a hypsochromic shift (2: 27 nm) compared to the absorption peaks for compound solutions, which in turn can lead to the formation of aggregates on TiO2.

Based on the results of electrochemical oxidation of compounds by cyclic voltammetry, it was proven that such structures have a more positive HOMO level compared to the electrolyte (I3-/I-). A quantitative estimate of this parameter is the oxidation potential (1: Eox = 1.44 V, 2: E_ox = 1.10 V, I3-/I-: Eox = 0.4 V). This fact indicates that the oxidized compounds are easily reduced by the redox couple of the electrolyte (I3-/I-), which indicates the effective regeneration of dyes.

To determine the LUMO energy levels, cyclic voltammetry data and absorption spectra data were used, which allow calculating the excited state oxidation potential (Eox-Egopt). The LUMO levels of compounds 1, 2 show more negative values compared to TiO2 (1: Eox-Egopt = -1.44 V, 2: Eox-Egopt = -1.27 V, TiO2: Eox-Egopt = -0.5 B), which contributes to the effective electron injection process.

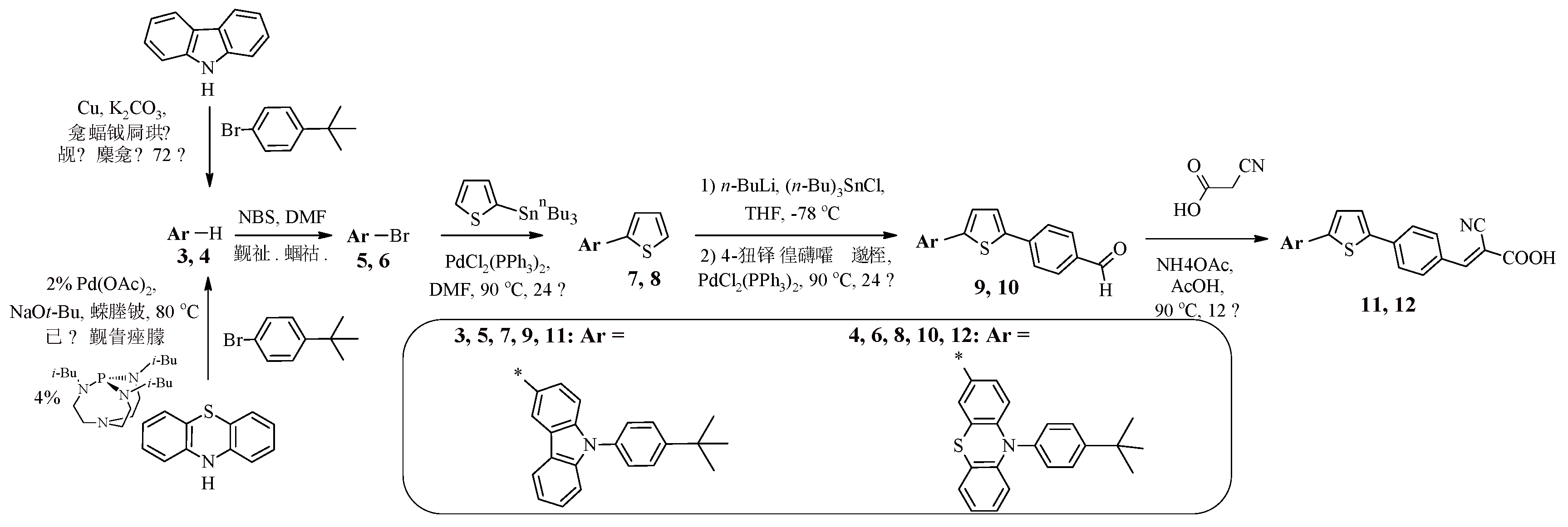

The introduction of a 4-

tert-butylphenyl fragment into the dye structure instead of alkyl chains is also one of the ways to provide steric hindrances in order to suppress intermolecular aggregation. Such an approach is presented in the article [

39]. Dyes 11, 12 contain in their structures 9-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-9

H-carbazole or 10-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-10

H-phenothiazine fragments connected via a thiophene-phenylene spacer to an electron-withdrawing fragment of cyanoacrylic acid (

Scheme 2). A multi-step approach was used to synthesize such compounds, including initial

N-arylation of the corresponding secondary amine (carbazole or phenothiazine) in the presence of copper salts (Ullmann reaction) or catalyzed by palladium complexes (Buchwald-Hartwig reaction) (

Scheme 2).

Further bromination of 9-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-9

H-carbazole 3 or 10-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-10

H-phenothiazine 4 afforded products 5, 6; subsequent chain extension was achieved by their initial reaction with 2-(tributylstannyl)thiophene under Stille reaction conditions to form 2-arylthiophenes 7, 8 (

Scheme 2). Afterwards, reaction with BuLi afforded the corresponding lithium derivatives, the reaction of which with tri(n-butyl)tin chloride afforded the corresponding organotin compounds. Their cross-coupling with 4-bromobenzaldehyde introduced an additional phenylene spacer into compounds 7, 8. The final stage was the condensation of carbaldehydes 9, 10 with cyanoacetic acid in the presence of catalytic amounts of ammonium acetate.

A study of the optical properties of compounds 11, 12 revealed the presence of two absorption maxima corresponding to electron transitions in the electron-donor fragment (short-wave peak) and transitions characterizing intramolecular charge transfer (long-wave peak).

It is worth noting that when replacing the 9-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-9

H-carbazole fragment in compound 11 with 10-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-10

H-phenothiazine, as in the previous example, a bathochromic shift of the wavelengths of the absorption maxima of the solutions of the compounds occurs, and the value of the molar extinction coefficient decreases (

Table 2).

It is interesting that the wavelength of the absorption maximum of the Cz-containing compound 11 adsorbed on the titanium dioxide surface is slightly shifted to the short-wave region of the spectrum (10 nm) compared to the absorption peak for the compound solution. This is explained, first of all, by the fact that when the carboxyl group is bound to TiO2, its electron-acceptor properties decrease. In the case of compounds 12, containing a phenothiazine fragment in their structure, this difference reaches 38 nm, which can lead to dye aggregation. In order to determine the efficiency of the solar cell, the HOMO and LUMO energies of the dyes 11, 12 were calculated. The results are presented in

Table 2. The compounds demonstrate a sufficiently high LUMO level compared to TiO

2 and a sufficiently low HOMO level compared to the ion pair of the electrolyte (I

3-/I

-), i.e. Such structures provide efficient dye regeneration, as well as an efficient electron injection process during the conversion of solar energy into electrical energy. Due to the fact that the compound 11, containing a 9-(4-

tert-butylphenyl)-9

H-carbazole fragment in its structure, has the lowest HOMO level, a device made on its basis, according to the authors of the article [

39], will demonstrate the most efficient charge regeneration. The light conversion efficiency of solar cells created on the basis of dyes 11, 12 was 6.70% and 6.32%, respectively.

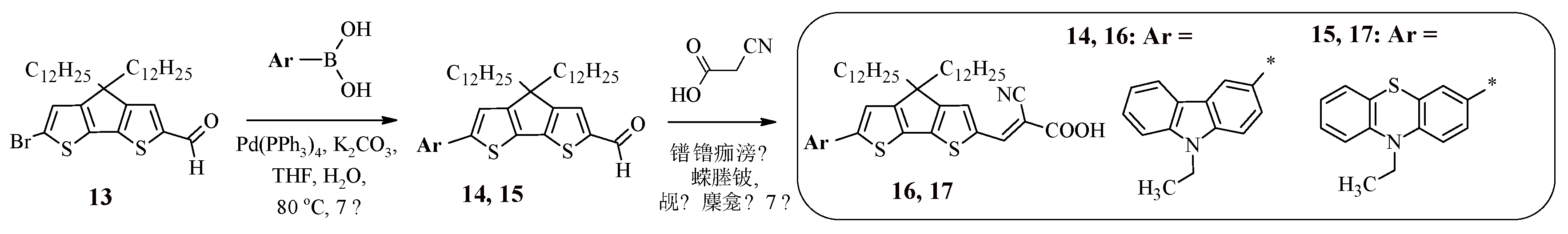

It was found that the use of condensed heterocyclic systems as a π-spacer has a number of advantages over their linearly linked analogs, namely, such structures enhance light absorption and also lead to the suppression of charge recombination [

40]. This explains the interest in the synthesis of dyes 16, 17, containing 4,4-didodecyl-4

H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b’]dithiophene as a spacer (

Scheme 3). The starting carbaldehyde 13 was obtained from 4

H-cyclopenta[2,1-b:3,4-b’]dithiophene by sequentially carrying out alkylation, formylation, and bromination reactions.

To introduce carbazole or phenothiazine fragments into the structure of the target product, the Suzuki reaction was used, the products of which (14, 15) upon interaction with cyanoacetic acid led to the production of dyes 16, 17.

Table 3 presents the results of studies of the optical and electrochemical properties of compounds 16, 17. The presence of a condensed heteroaromatic system in the structure of compounds 16, 17 led to the leveling of the electron-donor properties of carbazole and phenothiazine, since both dyes exhibit absorption at the same wavelength, while, as in the case of compounds 1, 2, 11, 12, compound 16, containing a carbazole fragment, has the highest value of the molar extinction coefficient.

Experimentally calculated values of HOMO and LUMO energies prove the efficiency of using such dyes in DSSCs (16: η = 7.5%, 17: η = 7.0%).

Previously described were Cz- and FTZ-containing dyes 11, 12, 16, 17 in the structure of which electron-donating heterocyclic fragments linearly linked to each other or condensed with each other are used as π-spacers.

3. D-A-π-A-Type Organic Dyes

In D-A-π-A-type compounds, an additional electron-withdrawing fragment allows for a significant facilitation of charge transfer from the donor to the acceptor located on the periphery of the molecule, and also helps to tune the absorption region and HOMO and LUMO levels. In addition, compounds of this type have high photostability [

41].

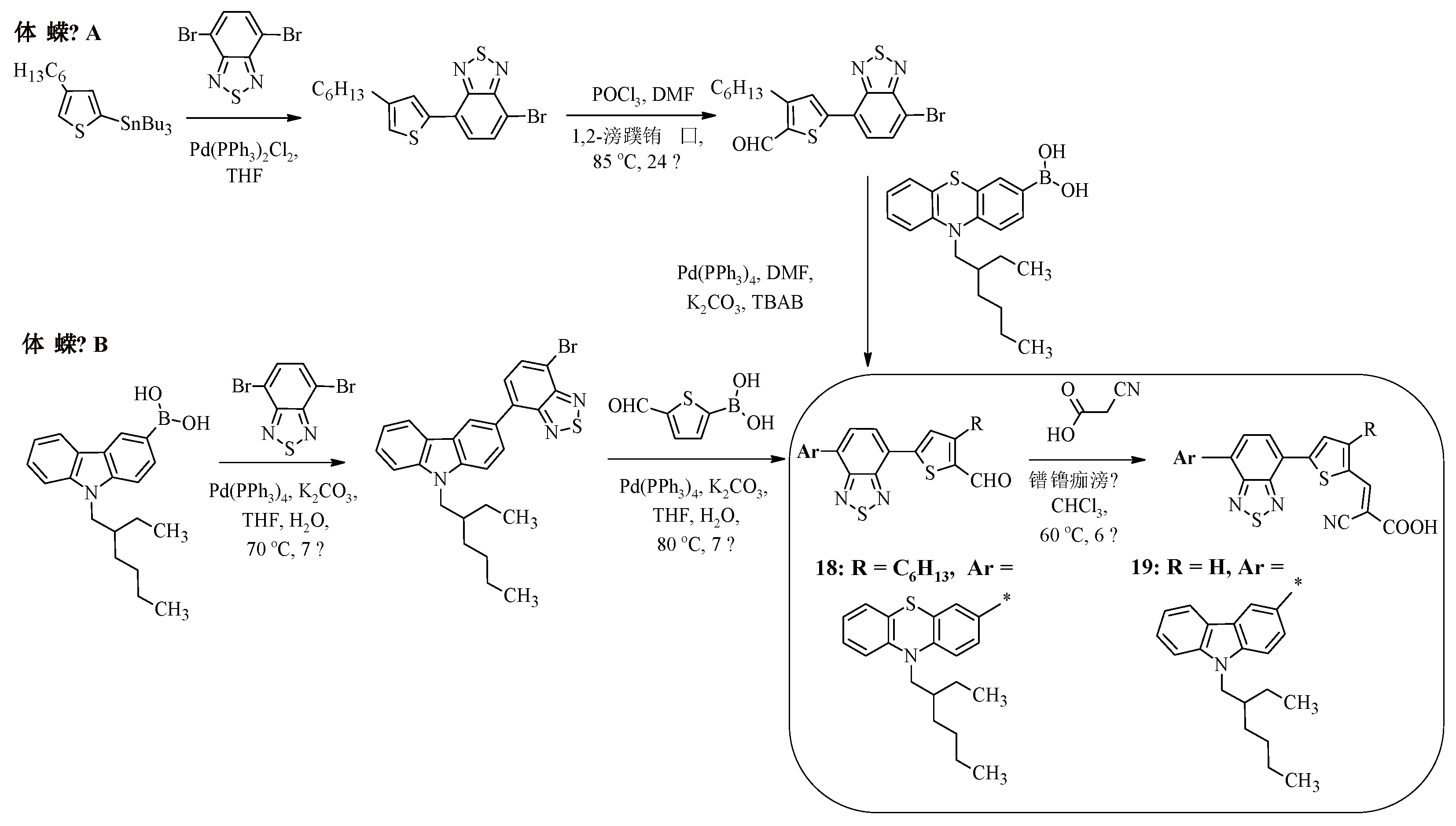

Scheme 4 shows the synthesis of compounds 18, 19, the carbazole or phenothiazine fragments of which are linked to a cyanoacrylic acid fragment via an additional benzothiadiazole bridge [42, 43]. It is worth noting that such structures can be obtained by two different methods. The first method involves carrying out 4 reactions – the Stille reaction, formylation, Suzuki reaction, and Knoevenagel reaction (Method A). The second method reduces the number of steps to three and involves a sequence of two Suzuki reactions, the final product of which, when reacted with cyanoacetic acid in chloroform with a catalytic amount of piperidine, leads to the formation of compounds 18, 19 (Method B).

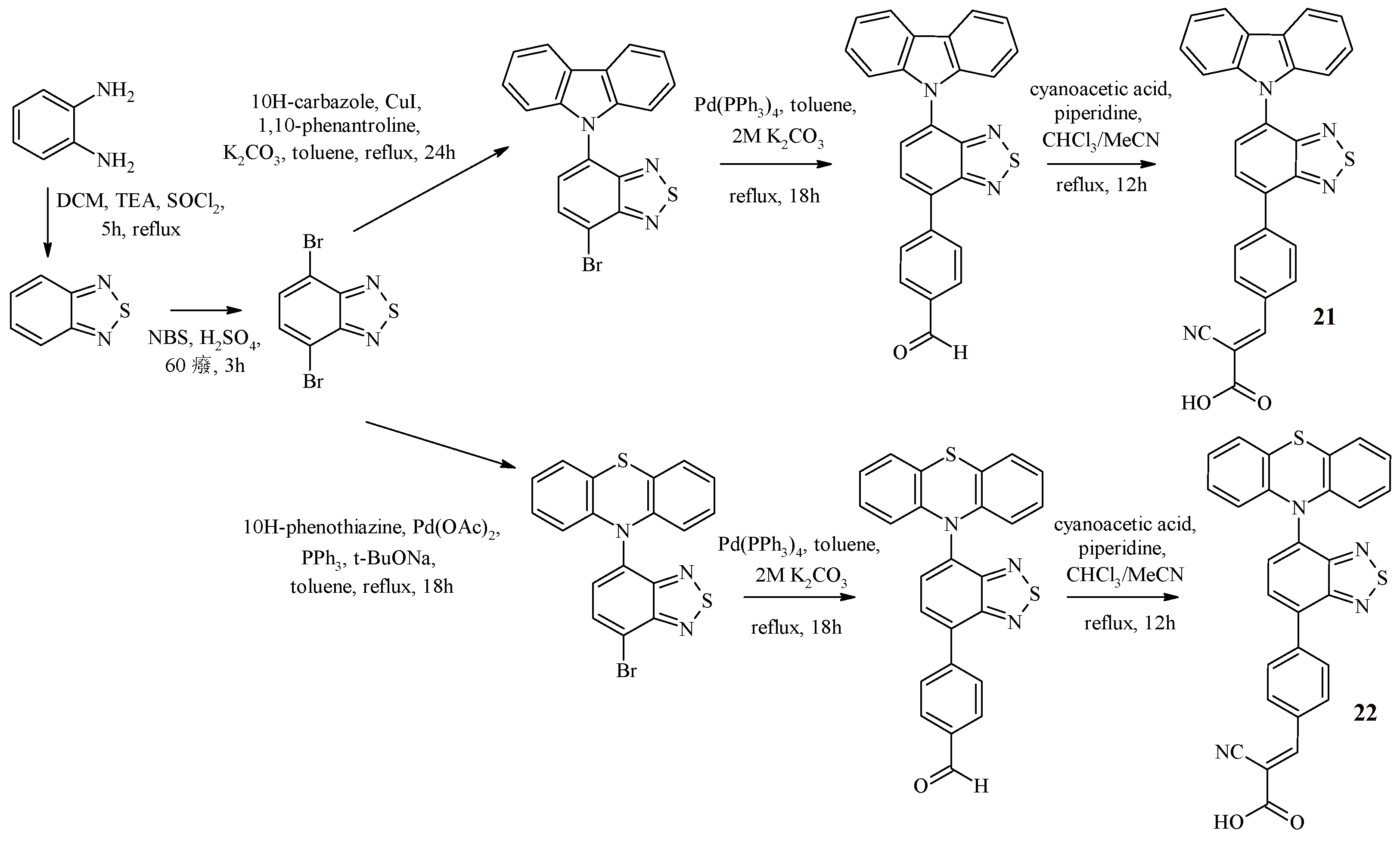

To clarify the question of how the introduction of an electron-withdrawing fragment as a π-spacer into the structure of dyes affects their photophysical properties, it is interesting to compare the properties of compound 18 with the characteristics of its analogue, compound 20 [

41] (

Figure 3).

The replacement of the thiophene ring in compound 20 with a benzothiadiazole ring (compound 18) leads to a slight shift in the wavelength of the absorption maximum to the long-wave region of the spectrum (18: λ

maxabs = 507 nm, 20: λ

maxabs = 494 nm), which allows expanding the spectral range of absorption. It is worth noting that the HOMO and LUMO energy values do not undergo significant changes (

Table 4), but the experimentally obtained values of the light conversion efficiency differ by almost two times (18: η = 5.00%, 20: η = 2.60%).

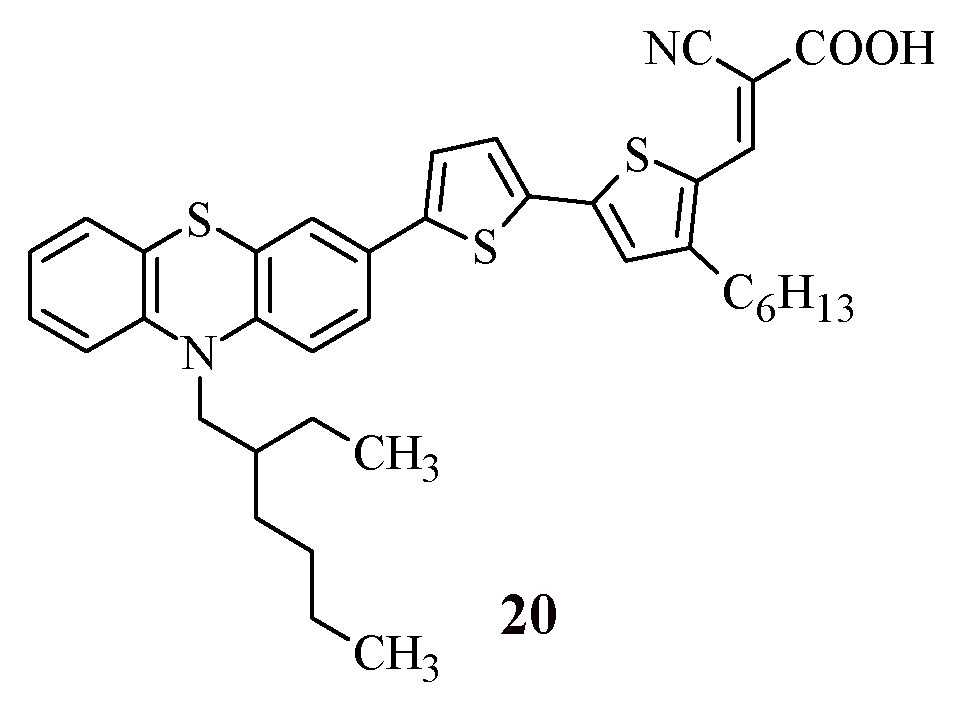

Recently, dyes 21, 22 have been synthesized containing carbazole or phenothiazine as an electron-donor fragment, as well as benzothiadiazole as an auxiliary acceptor, benzene as a π-bridge, and cyanoacrylic acid as an anchor group [

44] (

Scheme 5).

The synthesis of these dyes is shown in

Scheme 5 and included the initial preparation of 4,7-dibromobenzothiadiazole. The Buchwald-Hartwig reaction was used to introduce the phenothiazine fragment into the structure, and the Ullmann coupling reaction was used for the carbazole fragment. Further implementation of the palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of the obtained halides with 4-formylphenylboronic acid allowed us to obtain structures containing terminal aldehyde groups. The final stage of the synthesis of dyes 21, 22 was the Knoevenagel reaction. The study of optical and electrochemical properties is presented in

Table 5.

The synthesized dyes are characterized by a bathochromic shift of the absorption wavelength maxima in comparison with the compounds that do not contain a benzothiadiazole fragment [

45]. It is worth noting that compound 22, containing a phenothiazine fragment, has a longer-wavelength absorption region in comparison with the carbazole-containing compound 21, but 22 is characterized by a lower value of the molar absorption coefficient. The HOMO level values for dyes 21 (1.10 V) and 22 (1.04 V) are higher than such a value for the electrolyte (0.4 V for the redox pair I

−/I

3−), which ensures dye regeneration. At the same time, the HOMO level for the dye containing a phenothiazine fragment is less positive than that of the carbazole-containing dye, which is explained by the stronger electron-donor ability of the phenothiazine unit. On the other hand, the LUMO level values for dyes 21 (–1.39 V) and 22 (–1.16 V) are more negative than the conduction band of TiO

2 (– 0.5 V versus NHE), which ensures efficient electron injection into TiO

2.

The authors of the article tested the synthesized dyes in a DSSC. It was found that a cell based on a carbazole-containing dye is characterized by a higher value of energy conversion efficiency.

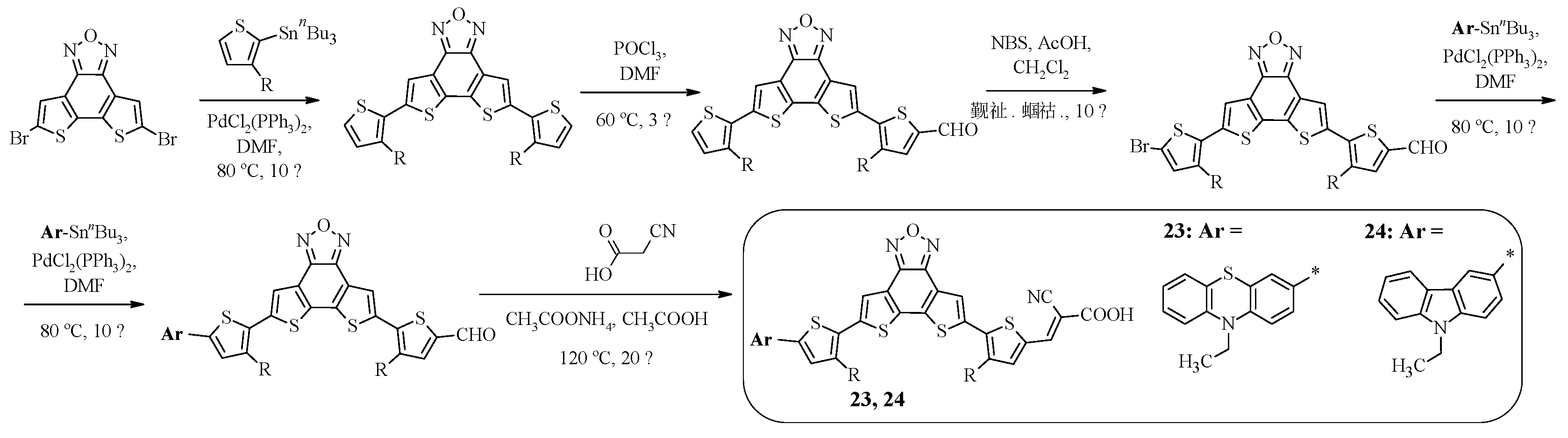

The series of compounds 23, 24 contains dithieno[3’,2’:3,4;2»,3»:5,6]benzo[1,2-c]furazan as a π-spacer [

46]. The advantage of introducing such an electron-withdrawing fragment is its rigid planar structure, which leads to efficient intramolecular charge transfer from the donor to the acceptor, and also allows reducing the reorganization energy of the dye molecule during photoexcitation. The synthetic approach to obtaining the compounds is presented in

Scheme 6. It uses a combination of the Stille reaction, formylation, bromination and, in the final stage, condensation.

As in the case of dyes 16, 17 containing a fused heterocyclic spacer, compounds 23, 24 demonstrate absorption in the same region, but their distinctive feature is the molar extinction coefficient, which reaches a higher value in the case of compounds of the D-A-π-A type (23, 24) in the presence of a phenothiazine fragment in the structure (

Table 6). The results of electrochemical oxidation of dyes 23, 24 confirm the pattern characteristic of compounds 1, 2, 11, 12, 16−19, namely, structures containing a carbazole fragment have a higher oxidation potential value and a deeper HOMO and LUMO level than FTZ-containing compounds, which is directly related to the light conversion efficiency (23: η = 1.42%, 24: η = 5.98%).

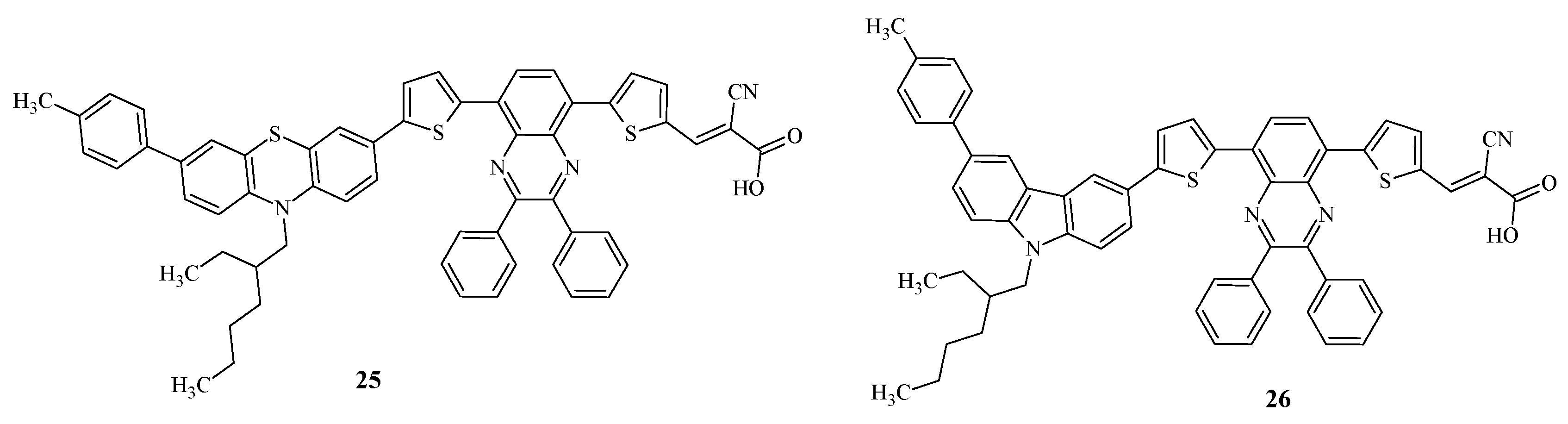

Recently, D-D-π-A-π-A quinoxaline dyes 25, 26 have been synthesized, differing from each other in the type of electron-donor fragment (

Figure 4) [

47].

Quinoxaline is a coplanar and rigid ring with strong electron-withdrawing ability due to two symmetric unsaturated nitrogen atoms in the pyrazine ring. In addition, the presence of the imine moiety increases the π-conjugation in the dye structure.

It has been shown that the introduction of 2,3-diphenylquinoxaline into the dye structure reduces charge recombination by inhibiting intermolecular aggregation due to two separate phenyl rings attached to the quinoxaline block [

48].

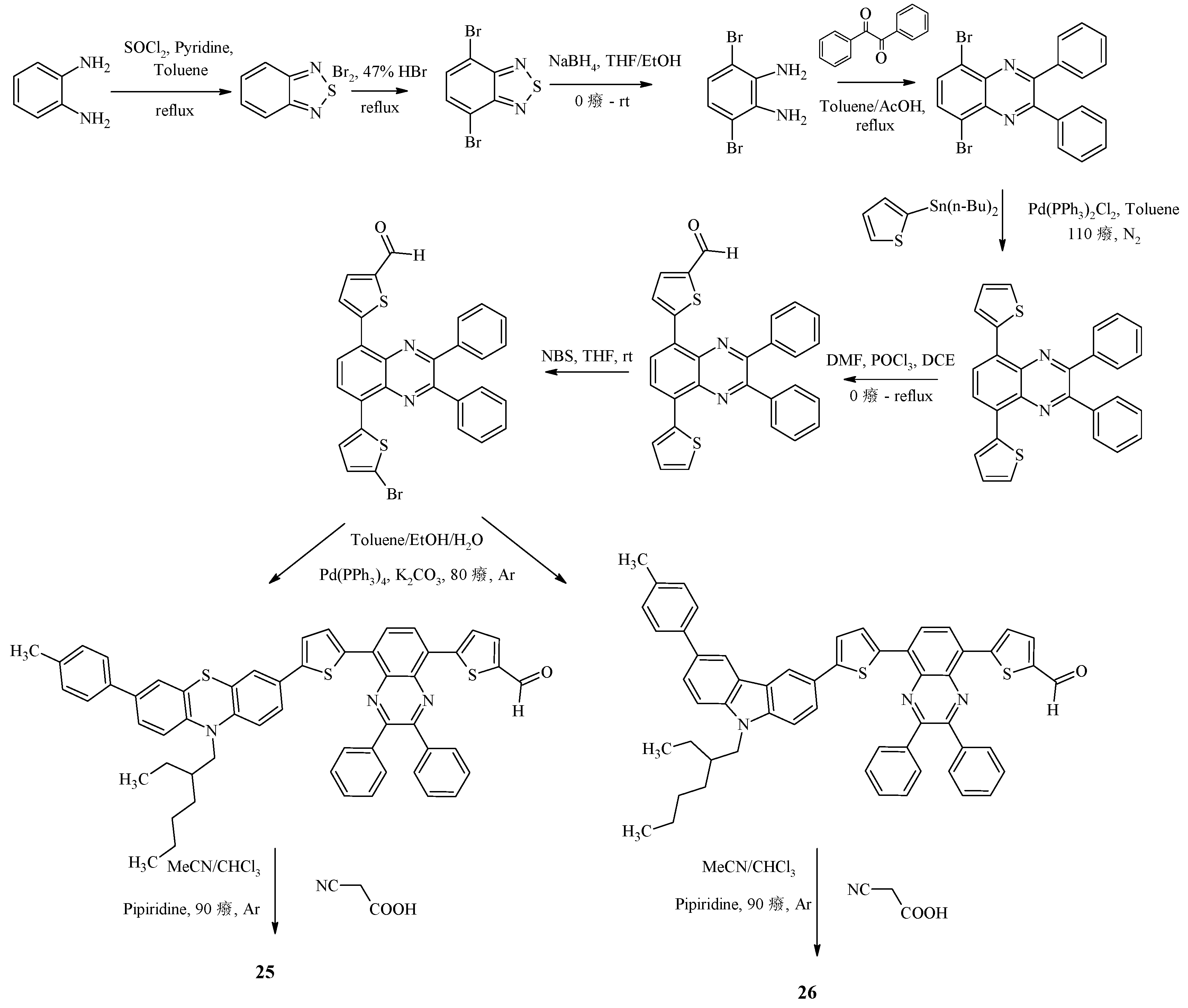

The multi-step synthesis of dyes 25, 26 is shown in

Scheme 7.

The results of the study of the optical and electrochemical properties of the dyes are presented in

Table 7.

The absorption spectra of the dyes demonstrate absorption bands in the region of 240-440 nm, which correspond to the π-π*-electron transition due to the presence of aromatic fragments in the structure. Also in the low-energy region, peaks are observed at 440-660 nm, characterizing the intramolecular charge transfer between donor and acceptor fragments. The dyes are characterized by high values of the molar extinction coefficient (

Table 7). It is important that these values are greater than those of standard ruthenium dyes N719 and N3 (14000 and 13900 M

− 1 cm

− 1, respectively). This fact proves that the presented dyes collect light significantly better than typical organometallic dyes.

For the presented type of structures, the dye 26, including a carbazole fragment, demonstrated a bathochromic shift of the absorption band, characterizing the intramolecular charge transfer, in comparison with the phenothiazine-containing dye. The authors believe that this is due to the increased planarity of the carbazole fragment compared to the phenothiazine, which has a non-planar butterfly shape. Parallel alignment of two benzene rings in the carbazole fragment provides smooth conjugation and, therefore, higher absorption.

The study of the electrochemical properties of the synthesized dyes showed that they are characterized by lower HOMO energies compared to the redox electrolyte (I

-/I

3-) (

Table 7). This fact indicates that oxidative regeneration of the dye is possible through I- in the DSSC electrolyte. On the other hand, the calculated LUMO values for the dyes are higher than that for TiO

2, indicating possible electron injection from excited dyes into TiO

2. As a result, all the dyes have sufficient fundamentality for their use as sensitizers in DSSCs.

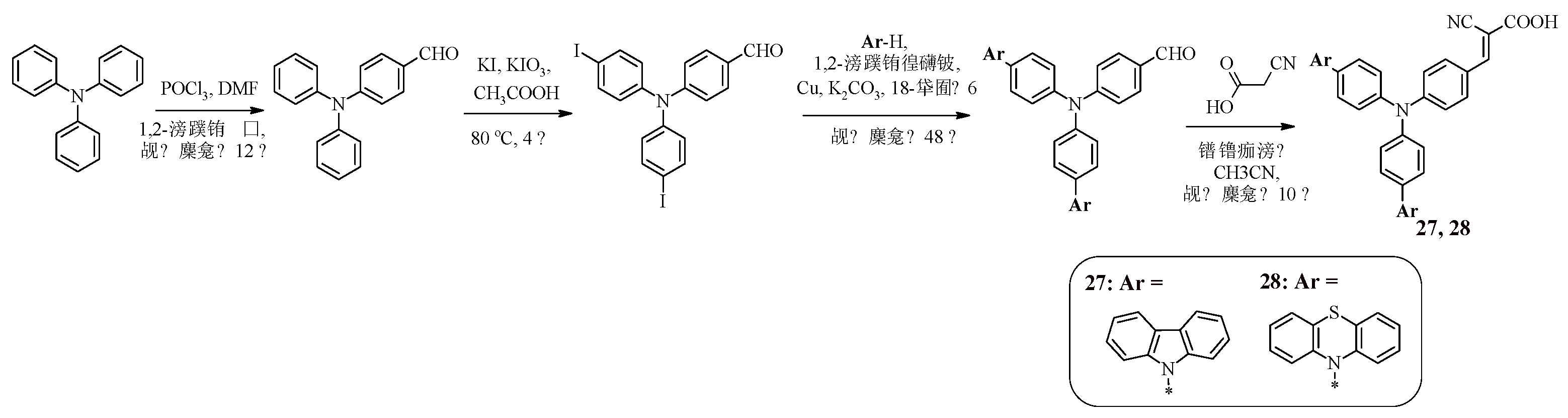

4. Organic Dyes with a Star-Shaped Structure

Several approaches to dye design that prevent intermolecular aggregation of dye molecules during solar cell operation have been previously presented, namely the introduction of long alkyl chains or a 4-

tert-butylphenyl fragment, as well as the use of a fused heteroaromatic system as a π-spacer. Dyes with a star-shaped structure are also of interest from the point of view of charge recombination suppression. For example, compounds 27, 28 contain a central triphenylamine core, on the periphery of which there are carbazole or phenothiazine fragments, as well as a cyanoacrylic acid fragment [

49]. The Ullmann reaction was used to synthesize such structures, the starting compound for which was 4-[bis(4-iodophenyl)amino]benzaldehyde, obtained in two stages from triphenylamine (

Scheme 8).

Table 8 presents the results of the study of the optical properties of dyes 27, 28.

Both compounds have one intense absorption band in the visible region of the spectrum. Moreover, for the phenothiazine-containing compound 28, as in the case of compound 23, a higher value of the molar absorption coefficient is characteristic. The absorption spectra for solutions of compounds 27, 28 in acetonitrile and the absorption spectra of compounds 27, 28 adsorbed on the surface of TiO

2 do not show a significant shift in the absorption wavelength, which indicates the prevention of aggregation of dyes on the titanium dioxide film (

Table 8).

The experimentally obtained values of HOMO energies of compounds 27, 28 (

Table 8) prove that the oxidized dyes formed as a result of the corresponding injection of electrons into the conduction band of TiO

2 will accept electrons from the electrolyte (I

3-/I

-), which will lead to their reduction. At the same time, a more negative value of the LUMO energy of the dyes (

Table 8) compared to the LUMO energy of TiO

2 (-0.5 V vs NHE) indicates that the process of electron injection from the dye molecule in the excited state into the conduction band of titanium dioxide is energetically allowed. It was found that the dyes 27, 28 do not exhibit significant differences in photophysical properties. However, the FTZ-containing compound 28 is characterized by a higher value of light conversion efficiency (27: η = 3.26%, 28: η = 4.54%), which is most likely due to its higher absorption capacity.

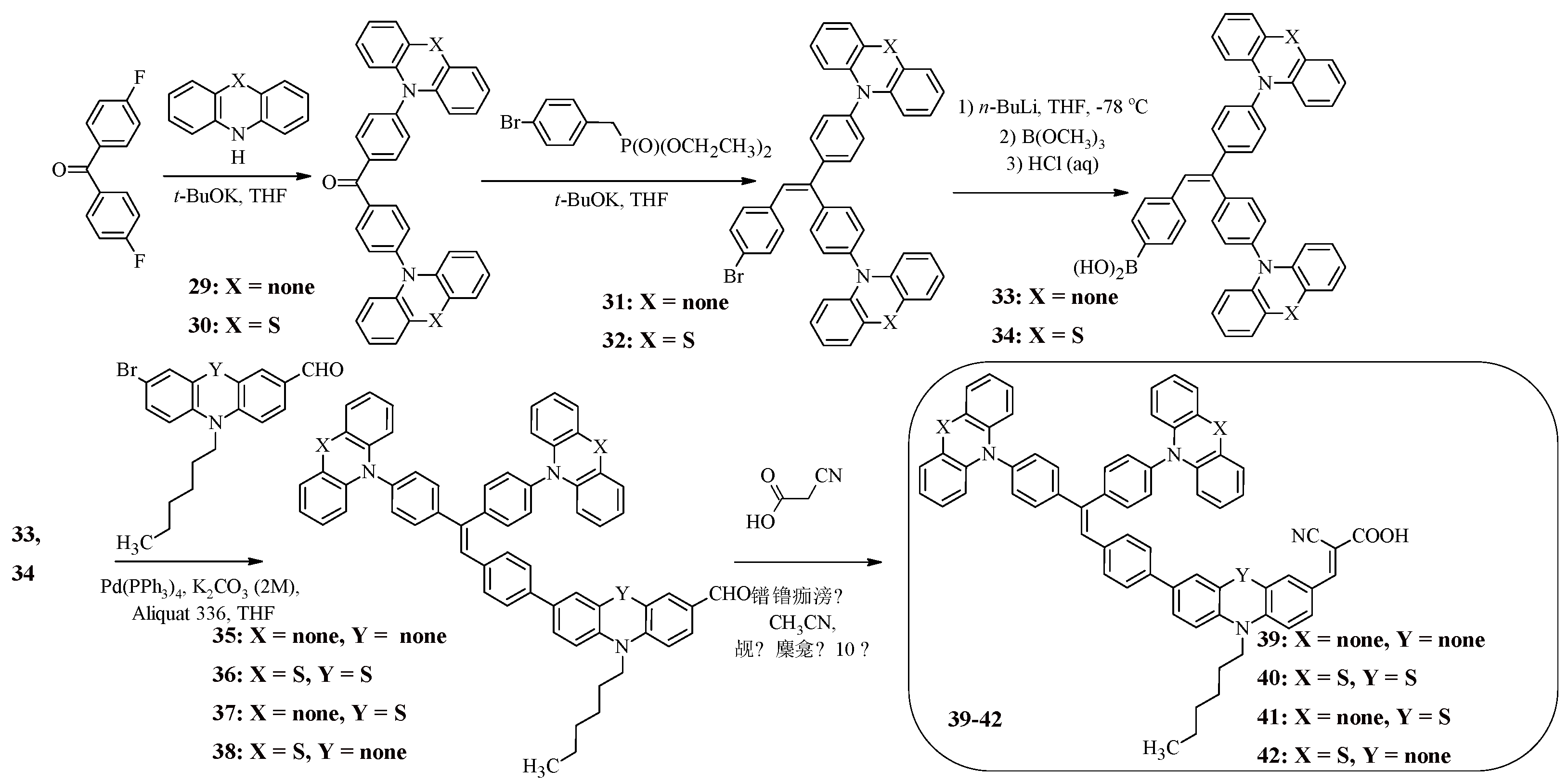

Along with triphenylamine, the introduction of which into the structure of the molecule allows to expand the absorption region and reduce the tendency to aggregation on the TiO

2 surface, triphenylethylene is of interest. For example, compounds 39-42 have a star-shaped structure, the central core of which is triphenylethylene, connected to terminal carbazole or phenothiazine fragments, as well as to the electron-withdrawing fragment of cyanoacrylic acid through electron-donating N-substituted carbazole or phenothiazine bridges (

Scheme 9) [

50]. The starting compound for the synthesis of such structures was bis(4-fluorophenyl)ketone, the products of whose interaction with carbazole or phenothiazine then entered into the Wadsworth-Emmons reaction, which led to the formation of the central triphenylethylene core (31, 32) (

Scheme 9). The presence of the bromine atom in compounds 31, 32 made it possible to obtain the corresponding boric acids 33, 34 from them, from which carbaldehydes 35-38 were then synthesized under Suzuki reaction conditions. The final stage was the Knoevenagel reaction, which led to the target dyes 39-42.

The spectra of dyes 39, 41 have several absorption peaks in the ultraviolet region (39: λ

maxabs = 238, 293, 341 nm, 41: λ

maxabs = 238, 293, 329, 341 nm), as well as one peak in the visible light region (39: λ

maxabs = 412 nm, 41: λ

maxabs = 462 nm), and the long-wave absorption maximum of compound 41 is shifted to the red region of the spectrum (50 nm) (

Table 9). The absorption spectra of the dyes 40, 42, containing phenothiazine fragments at the periphery of the molecule, in dichloromethane contain three absorption peaks (40: λ

maxabs = 258, 326, 466 nm, 42: λ

maxabs = 258, 335, 412 nm). It is also worth noting that for compound 40, a bathochromic shift of the absorption maximum wavelength is observed compared to compound 42, which is associated with the presence in its structure of a stronger electron-donating phenothiazine fragment, which is part of the π-spacer.

In the absorption spectra of dyes adsorbed on the surface of titanium dioxide, the absorption peaks are significantly shifted to the red region of the spectrum compared to the absorption wavelengths for solutions of compounds. The dyes 39-42 have a fairly deep HOMO level, about -5.0 eV, compared to the I

3-/I

- ion pair (E

HOMO = -4.60 eV) [

51], which indicates effective regeneration of the dye. It was found that FTZ-containing compounds 40, 41 have a more negative value of the LUMO level, which may indicate their higher efficiency in terms of using dyes in solar cells, as evidenced by the experimentally obtained values of light conversion efficiency (39: η = 2.14%, 40: η = 6.55%, 41: η = 5.51%, 42: η = 2.69%).

5. Organic Dyes of the A-D-A Type

The use of D-π-A configuration in organic dyes has some disadvantages, namely, the short length of π-conjugation contributes to a narrow absorption band. Although an increase in the length of π-conjugation will expand the absorption region, this structure is not very stable when irradiated with high-energy photons. In addition, such a structure can cause aggregation and charge recombination, which will lead to a decrease in photoelectric characteristics.

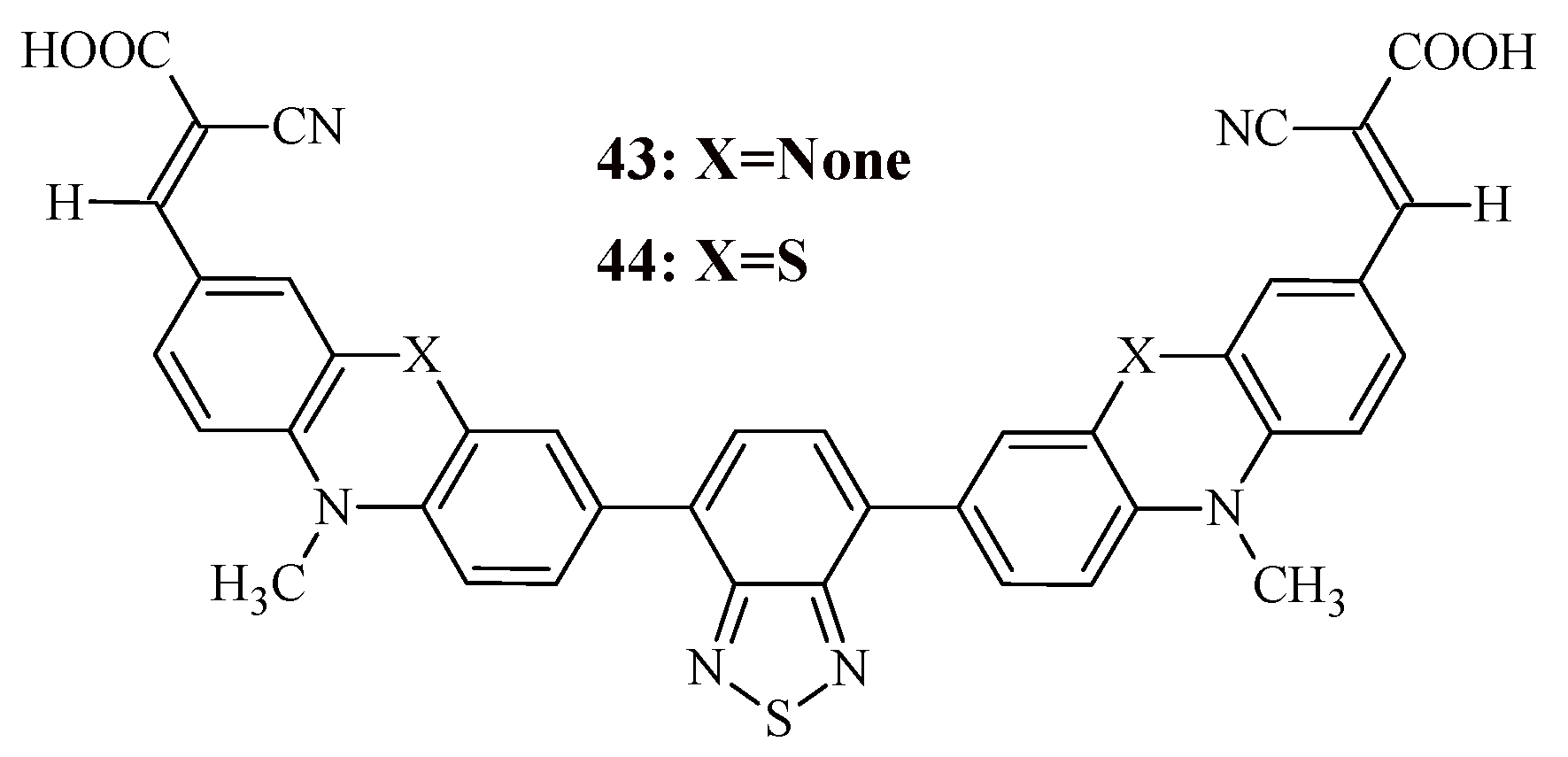

Therefore, new configurations of organic dyes are currently being developed, such as A-D-A-type structures. Recently, Murali et al. synthesized two organic sensitizers with the A-D-A-D-A configuration, in which the donor is carbazole or phenothiazine, the auxiliary acceptor is benzothiadiazole, and the terminal group is cyanoacrylic acid (

Figure 5) [

52].

The presence of two terminal electron-acceptor fragments in the dye structure facilitates efficient electron injection.

The synthesis of the dyes consisted of the following reactions: N-alkylation, Miyaura borylation reaction, Suzuki cross-coupling reaction, Vilsmeier-Haack reaction, and Knoevenagel reaction (

Scheme 10).

The study of optical and electrochemical properties of organic dyes 43, 44 is presented in

Table 10.

Both organic dyes exhibit two main absorption bands in the range of 340-410 nm and 420-540 nm. It is known that a wider absorption range contributes to better DSSC performance, since it allows collecting more photons.

The observed red shift in the absorption maxima of the dye 44 compared to the dye 43 may be due to the stronger electron-donating ability of the phenothiazine unit.

It is worth noting that for both organic dyes, the molar extinction coefficient values for the absorption maxima in the range of 420-540 nm, which characterize intramolecular charge transfer, are higher than those of the ruthenium dye N719 [

53]. It has been proven that high molar absorption coefficients of organic dyes allow obtaining a thinner nanocrystalline film on their basis, which leads to better device performance. In addition, it also promotes the diffusion of electrolyte in the film and reduces the possibility of recombination of light-induced charges during transport [54, 55].

In the absorption spectra of the dyes adsorbed on the transparent TiO2 thin film (2.5 mm), the absorption maxima of 43 and 44 showed a red shift of about 18 and 12 nm, respectively, compared to their dissolved state. The observed red shift of the absorption maxima and broadening of the absorption spectra for both dyes are possibly due to the formation of J-aggregates on the thin films.

To evaluate the possibility of electron transfer from the excited organic dye molecule to the conduction band of TiO

2 and from the redox couple in the electrolyte to the oxidized dye molecule, cyclic voltammetry measurements were performed for both dyes. The results are presented in

Table 10.

It was found that for organic dyes 43, 44, the ground state oxidation potential (Eox) was observed at 0.91 and 0.62 V, respectively, which is significantly higher than the iodide/triiodide oxidation-reduction potential (0.4 V). In addition, it is worth noting that the phenothiazine moiety has a significant effect on the oxidation potential of the dye, which leads to a lower Eox value for 44 compared to 43. The calculated excited state oxidation potentials for the dyes are more negative (43: E*ox = 1.45 V, 44: E*ox = 1.56 V) than the conduction band edge energy level of TiO2 (0.5 V). This fact indicates that the electron from the excited dye molecules can be effectively injected into the conduction band of TiO2. In general, the energy levels of the dyes 43, 44 are in good agreement with the requirements for efficient electron transfer in DSSC.

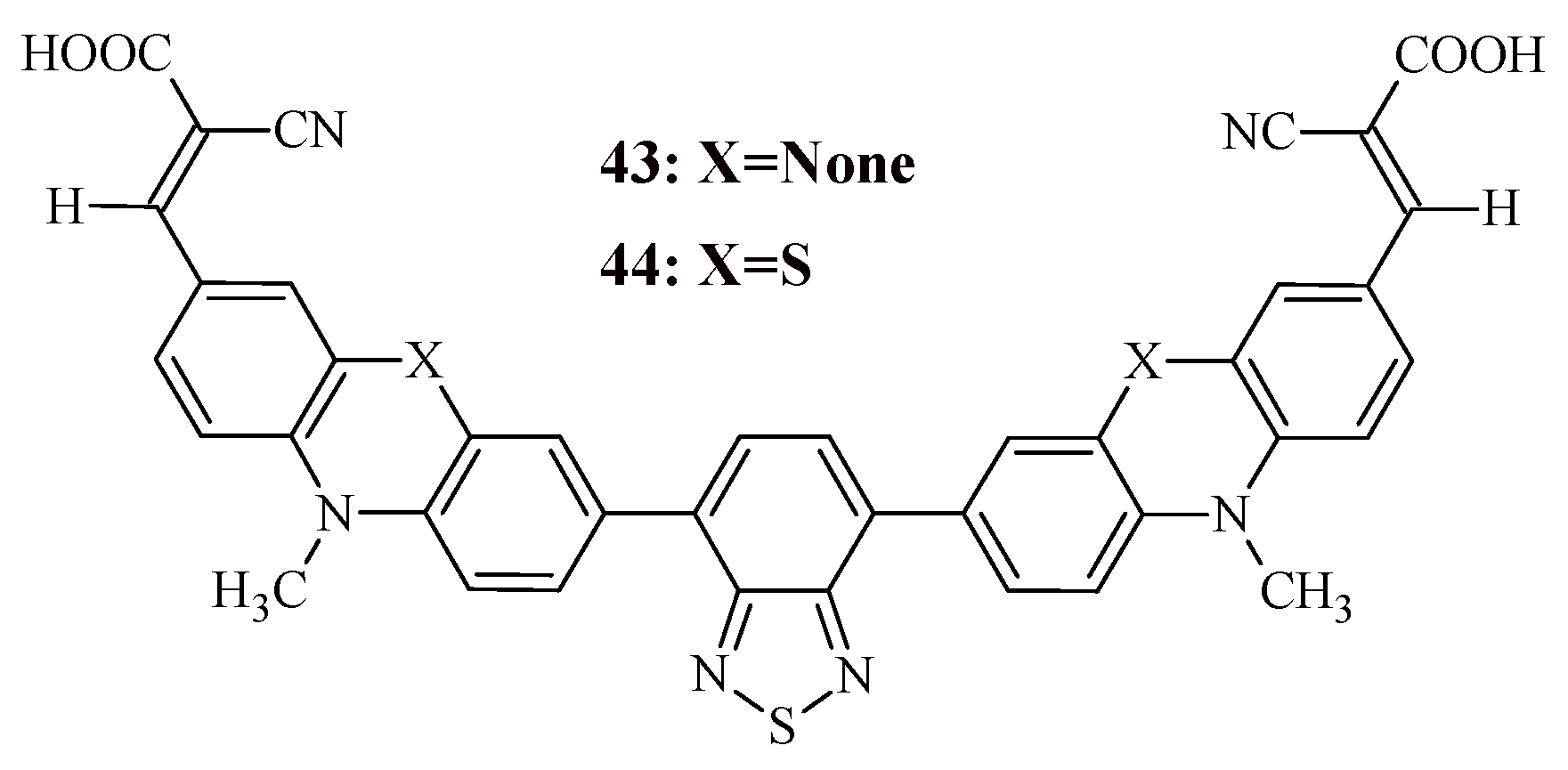

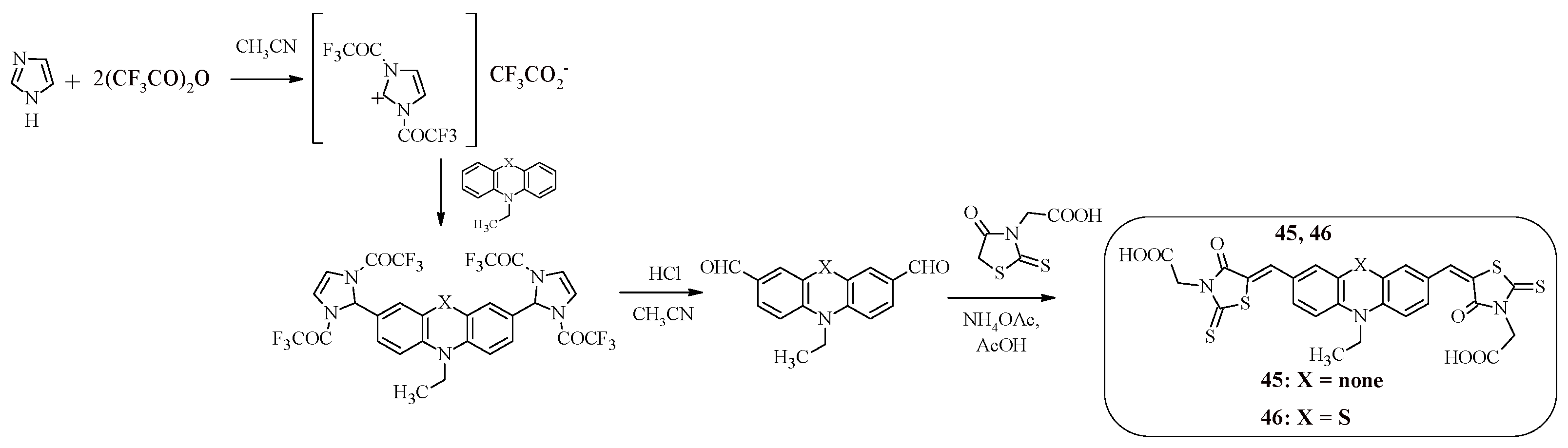

It is worth noting that rhodanine-3-acetic acid can be used as an “anchor” electron-withdrawing group in dyes instead of cyanoacrylic acid. For example, compounds 45, 46 (

Scheme 11), which are A-D-A-type structures, contain terminal rhodanine-3-acetic acid fragments linked to an N-ethylcarbazole or N-ethylphenathiazine fragment via a methylene bridge [

56].

An alternative approach to the Vilsmeier-Haack reaction was used to synthesize such structures, in which the starting dicarbaldehydes were obtained in two stages. Initially, the reaction product of imidazole with trifluoroacetic anhydride interacted with N-substituted carbazole or phenothiazine to form intermediate compounds containing trifluoroacetyl groups, the further hydrolysis of which led to the production of dicarbaldehydes. The final stage of the synthesis of compounds 45, 46 was the Knoevenagel reaction.

A comparative analysis of the photophysical characteristics of compounds 45, 46 is presented in

Table 11. As expected, the presence of a phenothiazine fragment in the structure of compound 46 shifts the absorption band to the long-wavelength region of the spectrum compared to the Cz-containing compound 45, which, in turn, leads to a decrease in the value of the band gap (45: E

gopt = 2.56 eV, 46: E

gopt = 2.18 eV).

Compound 45 is characterized by a more positive HOMO level, which indicates effective dye regeneration, but compound 46 has an effective electron injection process due to a deeper LUMO level. A study of the volt-ampere characteristics of solar cells found that the FTZ-containing compound 46 has the highest light conversion efficiency (45: η = 2.81%, 46: η = 4.91%).

6. Conclusions

Carbazole and phenothiazine are important structural fragments in the creation of materials for dye-sensitized solar cells. This is explained, first of all, by the fact that compounds containing Cz- or FTZ-fragments have high thermal and morphological stability. In addition, conjugated systems containing electron-donating carbazole and phenothiazine fragments in combination with the electron-accepting fragment of cyanoacrylic acid have a sufficiently deep HOMO level compared to the I3-/I- ion pair and are also characterized by a more negative LUMO energy value compared to TiO2. The first fact proves that the oxidized dyes formed as a result of the corresponding electron injection into the conduction band of TiO2 will accept electrons from the electrolyte (I3-/I-), which will lead to their reduction. The second fact indicates that the process of electron injection from the dye molecule in an excited state into the conduction band of titanium dioxide is energetically allowed. As a result, the use of such structures as materials for dye-sensitized solar cells will allow obtaining devices with high light conversion efficiency.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author under reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out within the framework of State Assignment (State Registration No. 124022200026-7).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, D.; Wei, W.; Hu, Y.H. Highly efficient dye-sensitized solar cells with composited food dyes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 10457–10463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.-X.; Huang, Z.-S.; Wang, L.; Cao, D. Quinoxaline-based organic dyes for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells: Effect of different electron-withdrawing auxiliary acceptors on the solar cell performance. Dyes Pigm. 2018, 159, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.-L.; Peng, Z.-J.; Gong, B.-Q.; Huang, C.-Y.; Guan, M.-Y. New 2D–π–2A organic dyes with bipyridine anchoring groups for DSSCs. New J. Chem. 2019, 43, 5820–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadsadee, S.; Promarak, V.; Sudyoadsuk, T.; Keawin, T.; Kungwan, N.; Jungsuttiwong, S. Theoretical study on factors influencing the efficiency of D–π′–A′–π–A isoindigo-based sensitizer for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.S.; Zang, X.F.; Hua, T.; Wang, L.; Meier, H.; Cao, D. 2,3-Dipentyldithieno [3,2-f:2’,3’-h]quinoxaline-based organic dyes for efficient dye-sensitized solar cells: effect of π-bridges and electron donors on solar cell performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 20418–20429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmovzh, T.N.; Knyazeva, E.A.; Tanaka, E.; Popov, V.V.; Mikhalchenko, L.V.; Robertson, N.; Rakitin, O.A. [1,2,5]Thiadiazolo[3,4-d]pyridazine as an internal acceptor in the D-A-π-A organic sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. Molecules 2019, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, D.; Suo, J.; Cao, Y.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Vlachopoulos, N.; Zakeeruddin, S. M.; Hagfeldt, A.; Gr¨atzel, M. Hydroxamic acid pre-adsorption raises the efficiency of cosensitized solar cells. Nature 2023, 613, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh-Yung Lin, R.; Wu, F.-L.; Chang, C.-H.; Chou, H.-H.; Chuang, T.-M.; Chu, T.-C. Y-shaped metal-free D-[small pi]-(A)2 sensitizers for high-performance dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 3092–3101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Li, T.; Robertson, N.; Xiang, H.; Wu, W.; Hua, J.; Zhu, W.H.; Tian, H. D-A-π-A motif quinoxaline-based bensitizers with high molar extinction coefficient for quasiolid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater.Interfaces 2016, 8, 31016–31024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddapuram, A.; Cheema, H.; McNamara, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hammer, N.; Delcamp, J. Quinoxaline-based dual donor, dual acceptor organic dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Chai, Z.; Su, J.; Chen, J.; Tang, R.; Fan, K.; Zhang, L.; Han, H.; Qin, J.; Peng, T.; Li, Q.; Li, Z. New sensitizers bearing quinoxaline moieties as an auxiliary acceptor for dye-sensitized solar cells. Dyes Pigment. 2013, 98, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Geng, Z.; Tian, H.; Zhu, W.H. Cosensitization of D-A-π-A quinoxaline organic dye: efficiently filling the absorption valley with high photovoltaic efficiency. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5296–5304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Jia, X.; Wang, Z.S.; Zhou, G. X-shaped organic dyes with a quinoxaline bridge for use in dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 9697–9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, R.; Zahoor, A. F.; Anjum, M. N.; Nazeer, U.; Haq, A. U.; Mansha, A.; Chaudhry, A. R.; Irfan, A. Synthesis And Photovoltaic Performance of Carbazole (Donor) Based Photosensitizers in Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells (DSSC): A Review. Top. Curr. Chem. 2025, 383, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadiga, D.; Selvakumar, M.; Shetty, P.; Sridhar Santosh, M.; Chandrabose, R. S.; Karazhanov, S. Recent developments in metal-free organic sensitizers derived from carbazole, triphenylamine, and phenothiazine for dye-sensitized solar cells. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 6584–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J. S.; Wan, Z. Q.; Jia, C. Y. Recent advances in phenothiazine-based dyes for dye-sensitized solar cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadhar, P. S.; Reddy, G.; Prasanthkumar, S.; Giribabu, L. Phenothiazine functional materials for organic optoelectronic applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 14969–14996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buene, A. F.; Almenningen, D. M. Phenothiazine and phenoxazine sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells–an investigative review of two complete dye classes. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 11974–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michinobu, T.; Osako, H.; Shigehara, K. Synthesis and properties of 1, 8-carbazole-based conjugated copolymers. Polymers 2010, 2, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kwon, Y. S.; Shin, W. S.; Moon, S. J.; Park, T. Carbazole-based copolymers: effects of conjugation breaks and steric hindrance. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 1909–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacareanu, L.; Catargiu, A. M.; Grigoras, M. Spectroelectrochemical characterization of isomeric conjugated polymers containing 2, 7-and 3, 6-carbazole linked by vinylene and ethynylene segments. High Perform. Polym. 2015, 27, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Yang, J.; Hua, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, L.; Long, Y.; Tian, H. Efficient and stable dye-sensitized solar cells based on phenothiazine sensitizers with thiophene units. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 1772–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalakshmi, V.; Gouthaman, S.; Sugunalakshmi, M.; Bargavi, S.; Lakshmi, S. Crystal structure of 10-ethyl-7-(9-ethyl-9Hcarbazol-3-yl)-10H-phenothiazine-3-carbaldehyde. Acta Cryst. 2017, E73, 726–728. [Google Scholar]

- Unny, D.; Sivanadanam, J.; Mandal, S.; Aidhen, I.S.; Ramanujam, K. Effect of flexible, rigid planar and non-planar donors on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, H845–H860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Pan, C.; Wang, G.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhang, M. Phenoxazine-based organic dyes with different chromophores for dye-sensitized solar cells. Org. Electron. 2013, 14, 2795–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.Y.; Li, L.; Wang, L. Synthesis and characterization of platinum(II) polymetallaynes functionalized with phenoxazine-based spacer. A comparison with the phenothiazine congener. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 897, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.E.; Hu, J.; Hong, Y. Novel metal-free organic dyes containing linear planar 11,12-dihydroindolo[2,3-a]carbazole donor for dye-sensitized solar cells: effects of π spacer and alkyl chain. Dyes Pigment. 2019, 164, 213–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratzel, M. Recent advances in sensitized mesoscopic solar cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1788–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashchuk, D. Yu.; Kokorin, A.I. Modern photoelectric and photochemical methods of solar energy conversion. Russ. Chem. J. 2008, 52, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Kalaignan, G. P.; Kang, Y. S. A review on mass transport in dye-sensitized nanocrystalline solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol., C. 2006, 7, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M. Progress in Ruthenium Complexes for Dye Sensitised Solar Cells. Platinum Metals Rev. 2009, 53, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, L.M.; Bermudes, V. de Z.; Ribeiro, H.A.; Mendes, A.M. Dye-sensitized solar cells: a safe bet for the future. Energy Environ. Sci. 2008, 1, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A.; Boschloo, G.; Sun, L.; Kloo, L.; Pettersson, H. Dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6595–6663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encyclopedia of electrochemical power sources Ed.-ih-Chief. J. Garche. Eds. C.K. Dyer, P.T. Moseley, Z. Ogumi, D.A. Rand, B. Scrosati. Elsevier Science, 2009. 4538 p. Millington K.R. Dye-sensitized solar cells. P. 10-21.

- Grätzel, M. Dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C: Photochem. Rev. 2003, 4, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagfeldt, A.; Grӓtzel, M. Light-induced redox reactions in nanocrystalline systems. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. S.; Yang, H. S.; Jung, D. Y.; Han, Y. S.; Kim, J. H. Effects of the number of chromophores and the bulkiness of a nonconjugated spacer in a dye molecule on the performance of dye-sensitized solar cells. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 2013, 420, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, R.; Pan, Y.; Li, L.; Hagfeldt, A.; Sun, L. Phenothiazine derivatives for efficient organic dye-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Commun. 2007, 3741–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y. J.; Chou, P.-T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Watanabe, M.; Liu, Zh.-Q.; Lin, J.-L.; Chen, K.-Y.; Sun, Sh.-Sh.; Liu, Ch.-Y.; Chow, T. J. High-Performance Organic Materials for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells: Triarylene-Linked Dyads with a 4-tert-Butylphenylamine Donor. Chem. Asian J. 2012, 7, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, J.; Cai, N.; Zhang, M.; Wang, P. Synchronously Reduced Surface States, Charge Recombination, and Light Absorption Length for High-Performance Organic Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 4461–4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhu, W. Organic sensitizers from D–p–A to D–A–p–A: effect of the internal electron-withdrawing units on molecular absorption, energy levels and photovoltaic performances. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 2039–2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Long, J.; Wang, G.; Pei, Y.; Zhao, B.; Tan, S. Effect of structural modification on the performances of phenothiazine-dye sensitized solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2015, 121, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keerthi, A.; Sriramulu, D.; Liu, Y.; Thuang, Ch.; Timothy, Y.; Wang, Q.; Valiyaveettil, S. Architectural influence of carbazole pushepullepull dyes on dye sensitized solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2013, 99, 787–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, B. S. Effect of electron donor groups on the performance of benzothiadiazole dyes with simple structures for dye-sensitized solar cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2024, 449, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Jia, C.; Zhou, L.; Huo, W.; Yao, X.; Shi, Y. Influence of different arylamine electron donors in organic sensitizers for dye-sensitized solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2012, 95, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.-Sh.; You, J.-H.; Hung, W.-I.; Kao, W.-S.; Chou, H.-H.; Lin, J. T. Organic Dyes Incorporating the Dithieno[3′,2′:3,4;2″,3″:5,6]benzo[1,2-c]furazan Moiety for Dye Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22612–22621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Marhabi, A. R.; El-Shishtawy, R. M.; Bouzzine, S. M.; Hamidi, M.; Al-Ghamdi, H. A.; Al-Footy, K. O. DD-π-A-π-A-based quinoxaline dyes incorporating phenothiazine, phenoxazine and carbazole as electron donors: Synthesis, photophysical, electrochemical, and computational investigation. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A 2023, 436, 114389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, D.; Przybylski, D.; Sołoducho, J. Synthesis and theoretical investigation using DFT of 2,3-diphenylquinoxaline derivatives for electronic and photovoltaic effects. J. Electron. Mater. 2021, 50, 5226–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Zh.; Jia, Ch.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Y. Influence of the antennas in starburst triphenylamine-based organic dyesensitized solar cells: phenothiazine versus carbazole. RSC Advances 2012, 2, 4507–4514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Ch.; Liao, J.-Y.; Chi, Zh.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Kuang, D.-B.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Xu, J. Metal-free organic dyes derived from triphenylethylene for dye-sensitized solar cells: tuning of the performance by phenothiazine and carbazole. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 8994–9005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Bai, Y.; Li, R.; Shi, D.; Wenger, S.; Zakeeruddin, S. M.; Grӓtzel, M.; Wang, P. Employ a bisthienothiophene linker to construct an organic chromophore for efficient and stable dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 92–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murali, M. G.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Valiyaveettil, S. New banana shaped A-D-π-D-A type organic dyes containing two anchoring groups for high performance dye-sensitized solar cells. Dyes Pigm. 2016, 134, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardo, S.; Meyer, G. J. Photodriven heterogeneous charge transfer with transitionmetal compounds anchored to TiO2 semiconductor surfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 115e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, J.; Wu, W.; Hua, J.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Tian, H. Starburst triphenylamine-based cyanine dye for efficient quasi-solid-state dye-sensitized solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2009, 2, 982e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazraji, A. C.; Hotchandani, S.; Das, S.; Kamat, P. V. Controlling dye (Merocyanine540) aggregation on nanostructured TiO2 films. An organized assembly approach for enhancing the efficiency of photosensitization. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 4693e700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-Y.; Tsao, M.-H.; Su, Sh.-G.; Wang, H. P.; Lin, Y.-Ch.; Chen, F.-L.; Chang, Ch.-W.; Sun, I-W. Synthesis, Characterization and Photovoltaic Properties of Di-Anchoring Organic Dyes. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2011, 22, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The structural formulas of carbazole and phenothiazine.

Figure 1.

The structural formulas of carbazole and phenothiazine.

Figure 2.

Operating principle of the Graetzel electrochemical cell [

30].

Figure 2.

Operating principle of the Graetzel electrochemical cell [

30].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1, 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds 1, 2.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 11, 12.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds 11, 12.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 16, 17.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of compounds 16, 17.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 18, 19.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of compounds 18, 19.

Figure 3.

Structural formula of compound 20.

Figure 3.

Structural formula of compound 20.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of compounds 21, 22.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of compounds 21, 22.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of compounds 23, 24.

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of compounds 23, 24.

Figure 4.

Structural formula of compound 25, 26.

Figure 4.

Structural formula of compound 25, 26.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of compounds 25, 26.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of compounds 25, 26.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of compounds 27, 28.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of compounds 27, 28.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of compounds 39-42.

Scheme 9.

Synthesis of compounds 39-42.

Figure 5.

Structural formula of compound 43, 44.

Figure 5.

Structural formula of compound 43, 44.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of compounds 43, 44.

Scheme 10.

Synthesis of compounds 43, 44.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of compounds 45, 46.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of compounds 45, 46.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of compounds 1, 2.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of compounds 1, 2.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

/

, eVf

|

| 1 |

349 (21406) |

382 |

2.88 |

1.44 |

-1.44 |

-5.83/-2.95 |

| 2 |

452 (19400) |

425 |

2.37 |

1.10 |

-1.27 |

−/− |

Table 2.

Photophysical properties of compounds 11, 12.

Table 2.

Photophysical properties of compounds 11, 12.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

/

, eVf

|

| 11 |

428 (40000) |

418 |

2.46 |

0.91 |

-1.55 |

-5.41/-2.95 |

| 12 |

446 (33900) |

408 |

2.39 |

0.56 |

-1.83 |

-5.06/-2.67 |

Table 3.

Photophysical properties of compounds 16, 17.

Table 3.

Photophysical properties of compounds 16, 17.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

| 16 |

532 (57500) |

2.11 |

1.15 |

-0.96 |

| 17 |

532 (46500) |

2.20 |

0.97 |

-1.23 |

Table 4.

Photophysical properties of compounds 18-20.

Table 4.

Photophysical properties of compounds 18-20.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Вe

|

| 18 |

420 (18900),

507 (22100) CHCl3

|

450 |

2.27 |

0.98 |

-1.29 |

| 19 |

484 (26206) THF |

505 |

2.20 |

0.44, 0.69 |

-1.26, -1.80 |

| 20 |

494 (26200) CHCl3

|

498 |

2.24 |

0.96 |

-1.28 |

Table 5.

Photophysical properties of compounds 21, 22.

Table 5.

Photophysical properties of compounds 21, 22.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, eVe

|

| 21 |

338 (31900),

434 (9600) |

478 |

2.49 |

1.10 |

-5.41/-1.39 |

| 22 |

362 (27200)

467 (1300) |

481 |

2.19 |

1.03 |

-5.06/-1.16 |

Table 6.

Photophysical properties of compounds 23, 24.

Table 6.

Photophysical properties of compounds 23, 24.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

/

, eVf

|

| 23 |

390 (26100),

464 (31400) |

504 |

2.35 |

0.99 |

-1.36 |

-5.39/-3.05 |

| 24 |

366 (14400),

462 (17000) |

476 |

2.34 |

1.27 |

-1.07 |

-5.67/-3.33 |

Table 7.

Photophysical properties of compounds 25, 26.

Table 7.

Photophysical properties of compounds 25, 26.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, eVb

|

, Vc

|

/

, eVd

|

| 25 |

511 (23434) |

2.21 |

0.73 |

-5.07/-2.86 |

| 26 |

526 (23214) |

2.09 |

0.79 |

-5.13/-3.04 |

Table 8.

Photophysical properties of compounds 27, 28.

Table 8.

Photophysical properties of compounds 27, 28.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

| 27 |

424 (13834) |

424 |

2.55 |

0.45 |

-2.10 |

| 28 |

422 (29367) |

416 |

2.63 |

0.64 |

-1.99 |

Table 9.

Photophysical properties of compounds 39-42.

Table 9.

Photophysical properties of compounds 39-42.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, eVb

|

, Vc

|

, Vd

|

/

, eVe

|

| 39 |

238 (57000),

293 (32000),

341 (30000),

412 (16000) |

2.45 |

0.75 |

-1.7 |

-5.02/-2.57 |

| 40 |

258 (88000),

326 (45000),

466 (14000) |

1.89 |

0.74 |

-1.15 |

-5.01/-3.12 |

| 41 |

238 (84000),

293 (48000),

329 (41000),

341 (40000),

462 (13000) |

1.92 |

0.76 |

-1.16 |

-5.03/-3.10 |

| 42 |

258 (72000),

335 (37000),

412 (21000) |

2.42 |

0.72 |

-1.7 |

-4.99/-2.57 |

Table 10.

Photophysical properties of compounds 43, 44.

Table 10.

Photophysical properties of compounds 43, 44.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

| 43 |

440 (29400) |

456 |

2.36 |

0.91 |

-1.45 |

| 44 |

471 (27800) |

482 |

2.18 |

0.62 |

-1.56 |

Table 11.

Photophysical properties of compounds 45, 46.

Table 11.

Photophysical properties of compounds 45, 46.

| |

, nm

(ε, M-1 cm-1)a

|

, nm

(TiO2)b

|

, eVc

|

, Vd

|

, Ve

|

/

|

| 45 |

295, 355, 403,

450 (26360) |

442 |

2.56 |

0.64 |

-1.92 |

-5.15/-2.59 |

| 46 |

298, 357,

489 (25480) |

488 |

2.18 |

0.55 |

-1.63 |

-5.06/-2.88 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).