1. Introduction

In Mexico, the main types of meat consumed are beef, pork, lamb, and poultry. Specifically in Yucatán, the pig industry has seen significant growth in recent years due to its accessibility in terms of price and the economic impact it generates [

1]. However, the expansion of farms and the increased number of animals per pen have led to a rise in the generation and discharge of pig farm wastewater into the karstic soils of Yucatán. In Yucatán, it is estimated that over 6,000,000 m³ of pig wastewater are generated annually. Of this volume, more than 30% receives no prior treatment before being discharged, often directly onto the ground or in areas near the farms [

2]. Due to the highly permeable nature of the karstic soils and the shallow depth of the groundwater, the region is particularly vulnerable to contamination from untreated pig farm effluents [

3]. These wastes contaminate the environment through both direct and indirect contact, leading to issues such as water quality degradation, unpleasant odors, accumulation and saturation of organic matter in the soil, increased salinity, elevated concentrations of metals, and potential health risks, among others [

4,

5]. On the other hand, due to their high content of organic matter and mineral elements, these wastes can be utilized by plants during growth as a type of biofertilizer [

6]. However, it is essential to conduct further studies to determine appropriate disposal methods and optimal sites for final discharge, as well as strategies for reuse, in order to enhance their utility while minimizing the risk of environmental contamination [

7].

Several studies suggest the use of liquid manures and leachates as biological fertilizers or biofertilizers. In this context, [

8] reported positive results in Capsicum plant performance following the application of liquid swine excreta. Similarly, [

9] evaluated the effects of bovine manure and chemical fertilizers on the morphological development of husk tomato (

Physalis ixocarpa Brot.) seedlings. In maize seedlings, bovine manure leachate was found to influence both plant height and fresh weight in treated groups [

10]. Additionally, the use of manures such as bovine manure has been reported to increase nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) concentrations in tomato plants [

11]. In

Capsicum annuum L. plants, goat manure leachates have also been shown to enhance both plant height and leaf number [

12].”

The use of waste from pig farms represents a sustainable alternative for agricultural production. However, due to the limited information available regarding the interaction and response of plants in contact with piggery wastewater, it is imperative to generate knowledge on this subject. This would allow for the development of a biological fertilizer with reduced environmental and public health risks. Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of swine wastewater on the distribution, elemental concentration, and morphology of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) seedlings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

The experiment was conducted at the Faculty of Engineering of the Autonomous University of Yucatán, specifically in the Environmental Engineering Laboratory A greenhouse structure was built, enclosed with mesh and covered with plastic sheeting, to produce habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) seedlings irrigated with treated swine wastewater.

2.2. Swine Wastewater Collection and Characterization

The swine wastewater used in this study was collected from a pig farm selected based on its size, production scale, location, compliance with regulatory, and the presence of an on-site wastewater treatment plant (WWTP). The WWTP system includes a pumping station, solids separator, anaerobic biodigester, and facultative lagoons equipped with aeration and zoning. The wastewater for the experiment was obtained after the final stage of treatment. According to Mexican regulations (NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021 and NOM-003-ECOL-1997), this treated swine wastewater mets the requirements for agricultural reuse.

2.3. Experimental Design and Plant Material

The experimental design was a completely randomized design (CRD) with five replicates per treatment. Each replicate consisted of 10 seedlings. Seeds of habanero pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) were sown individually into polystyrene trays (200 cells) filled with peat moss-based substrate. After germination, seedlings were irrigated with different treatments: T1 = 20% wastewater + 80% water; T2 = 40% wastewater + 60% water; T3 = 60% wastewater + 40% water; T4 = 80% wastewater + 20% water; T5 = 100% wastewater; T6 = control (100% water, grown with conventional fertilization). Irrigation was performed three times per week over a period of 40 days. The control group received a conventional nutrient solution with 190 mg L⁻¹ of NPK (Poly-Feed 19-19-19, Haifa Chemicals, Mexico City, Mexico). Environmental conditions averaged 32 ± 3 °C daily temperature and 60% relative humidity.

2.4. Evaluated Variables

In the swine wastewater and its dilutions according to each treatment, physicochemical parameters were determined, including pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Suspended Solids (SS), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN), and Total Phosphorus (TP), in accordance with current regulations. In the seedlings, physiological variables such as seed emergence and emergence rate were evaluated, as well as morphological and growth variables, including elemental distribution and concentration, as well as seedling quality indices.

2.5. Emergency Test and Emergency Rate Index

Seedling emergence and emergence rates were evaluated in polystyrene trays filled with germination substrate. One seed was placed in each cell, and a seedling was considered to have emerged when the hypocotyl hook was visible. The count was conducted daily for a period of 7 days. The variables were calculated according to [

13].

2.6. Evaluation of the Morphological Traits of the Seedlings

Seedling height was measured from the base to the tip of the apical shoot using a tape measure. After 40 days of emergence, seedlings were harvested and separated into roots and shoots (leaves + stem). Each section was dried and weighed to determine dry biomass. Based on the biomass data, the Shoot-to-Root Ratio (SRR) and the Dickson Quality Index (DQI) were calculated following the method described by [

14].

2.7. Elemental Analysis of Seedlings

Elemental analysis was conducted 40 days after seedling emergence. Five seedlings per treatment were selected and placed on graphite plates. Elemental distribution and concentration were determined using an X-ray microfluorescence analyzer (M4 TORNADO, Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA) operating at 50 kV and a distance of 3 cm. Scans were performed across the entire surface of each seedling. The elements quantified included potassium (K), calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), chlorine (Cl), and sulfur (S).

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Percentage data were transformed using the arcsine square root method. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for the evaluated variables at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. When significant differences were found between treatments, means were compared using Tukey’s test (α = 0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistica version 7 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters of Swine Wastewater

The treatments with swine wastewater did not show significant differences in pH. In terms of EC, the control treatment had the lowest value (878 µS/cm), with T1 being close at 2120 µS/cm, while the 100% wastewater treatment (T5 = 7233 µS/cm) increased the EC by up to 87%. A similar trend was observed for chemical oxygen demand (COD); treatments with a higher proportion of wastewater showed the highest values (T5 = 563 and T4 = 485 mg/L), with the organic load in the wastewater influencing the COD concentrations in the treatments. In total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), the percentage of wastewater in the treatments increased the concentration of this element by up to 98% compared to the control (T6 = 5.8 mg/L). On the other hand, the total phosphorus (TP) results were reversed: T1 (11.2 mg/L), with the lowest percentage of wastewater, had higher values compared to the other treatments, while those with higher wastewater concentrations, as well as the control, showed lower values (

Table 1). The percentage of swine wastewater in the various treatments influenced the physiological characteristics of the seeds and seedlings of habanero pepper.

3.2. Seedling Emergence and Emergence Rate

Significant differences were found between treatments for the physiological variables of the seeds. For emergence, treatments T1 (97%) and the control (98%) were statistically superior to the other treatments. Similarly, for emergence rate, these treatments had the highest values, with 13.09 and 13.58 seedlings/day, respectively. In both variables, the percentage of swine wastewater modified seed vigor expression, decreasing emergence and the number of seedlings per day, while the 20% dilution enhanced the number of seedlings and consequently resulted in a higher percentage (

Table 2).

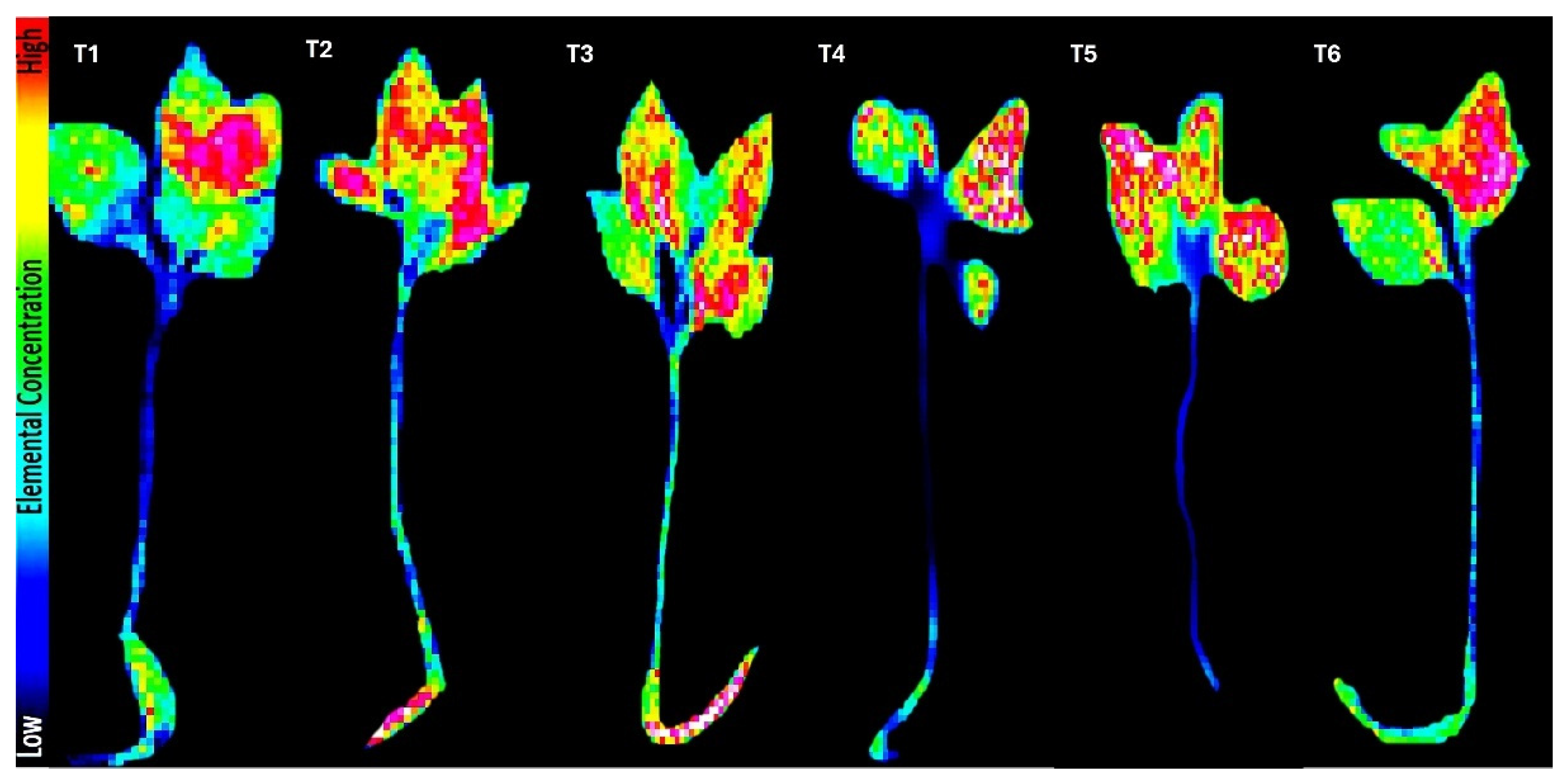

3.3. Distribution of Essential Elements in Habanero Pepper Seedlings

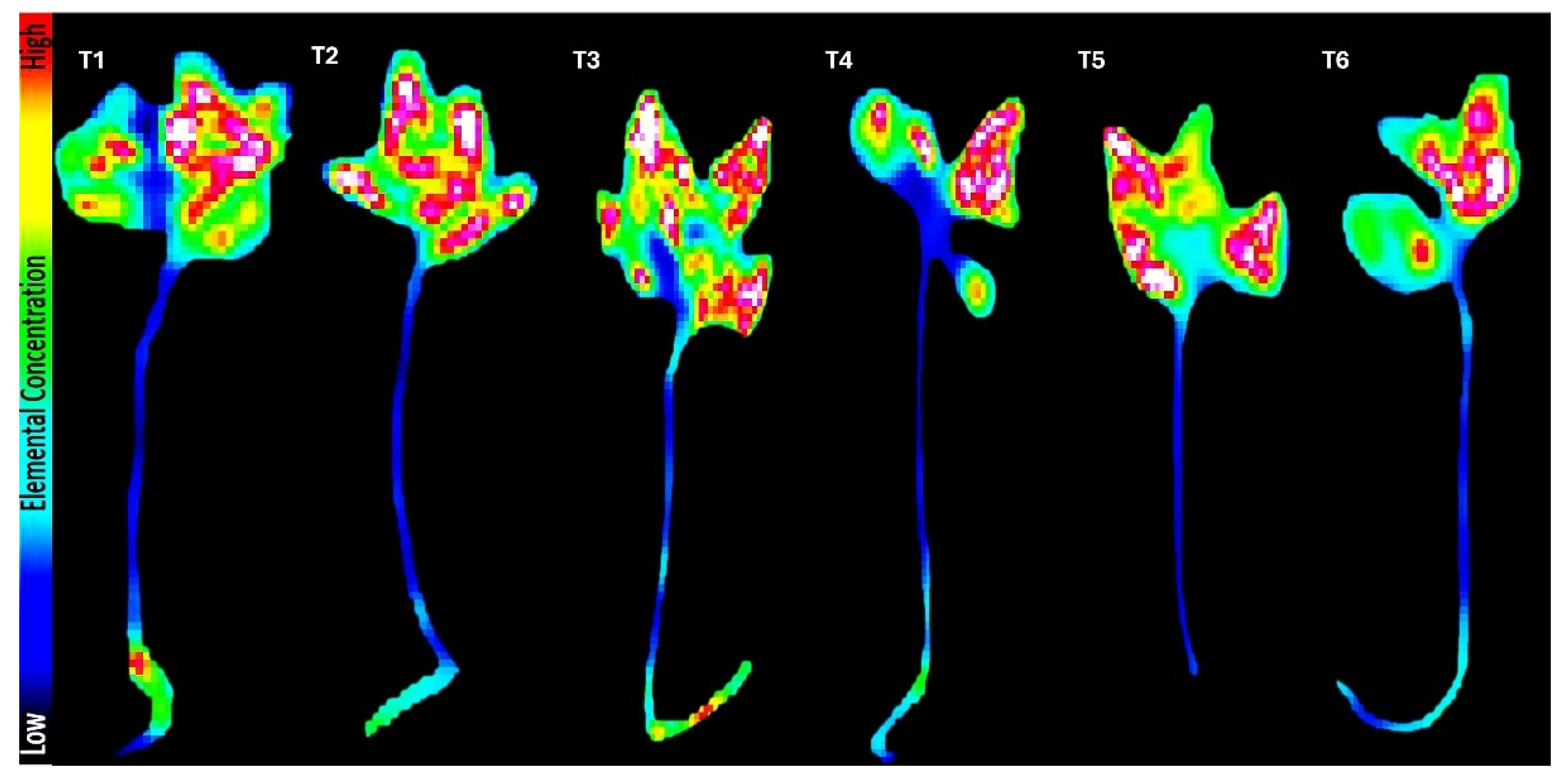

Swine wastewater influenced the distribution and concentration of essential elements in habanero pepper seedlings. The dilution of the wastewater was a key factor in the distribution of certain elements, such as potassium (K), with treatments T1 and the control (T6) showing higher K accumulation in growth areas, such as the stem and root meristems. The increased presence of K facilitated vital processes like protein synthesis, photosynthesis, and overall growth. In contrast, higher wastewater concentrations reduced potassium distribution, likely due to the excess organic load present in the wastewater (

Figure 1).

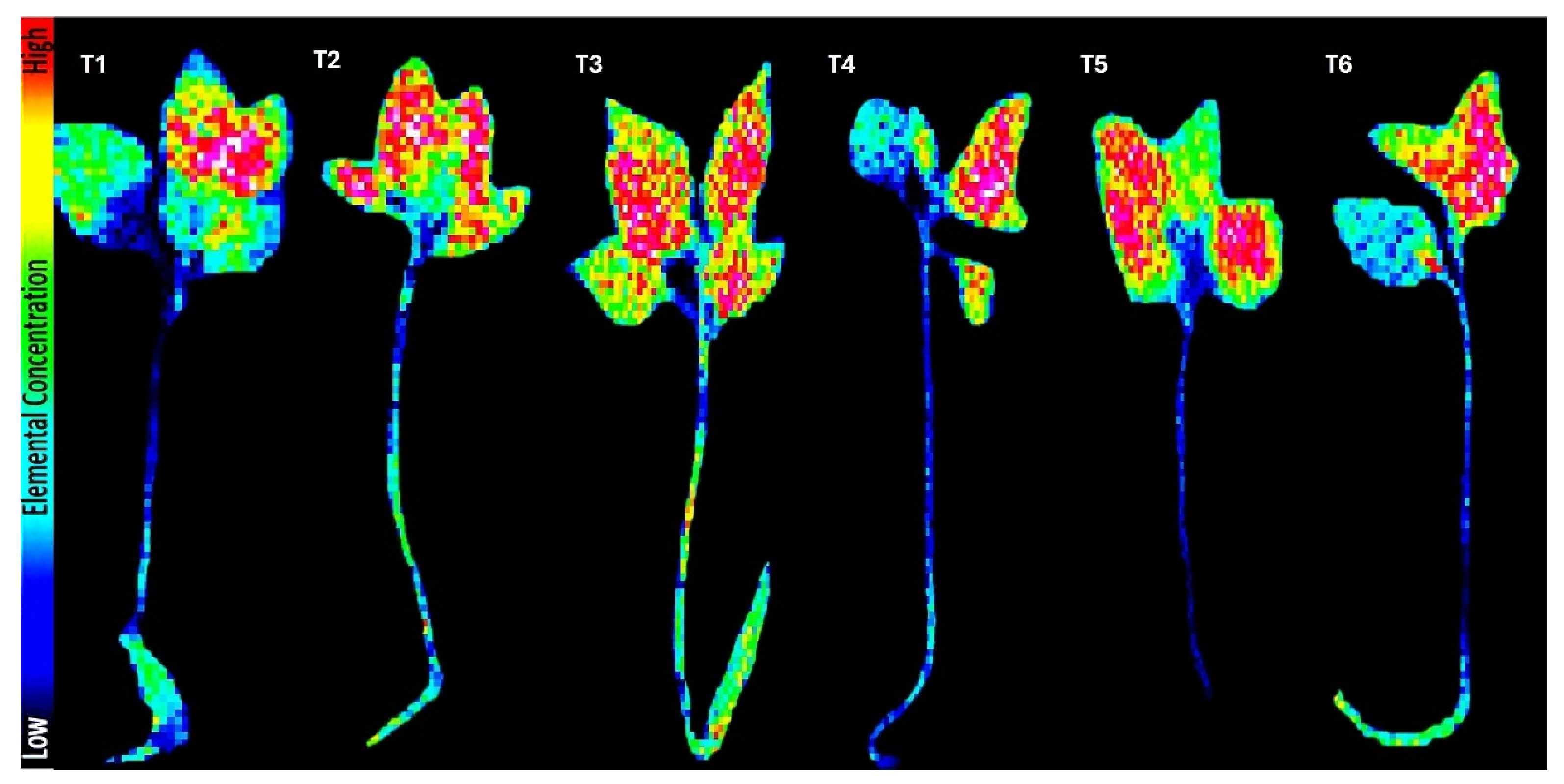

Ca, similar to K, was distributed in the growth areas of the seedlings, as it is an element that acts as a metabolic activator and is involved in plant growth. In the treatments with 20% and 40% swine wastewater (T1 and T2), a higher distribution was observed in the growth meristems, even higher than the Control (T6). The distribution was also found in the root, but in smaller amounts, while treatment T5 showed the lowest distribution (

Figure 2).

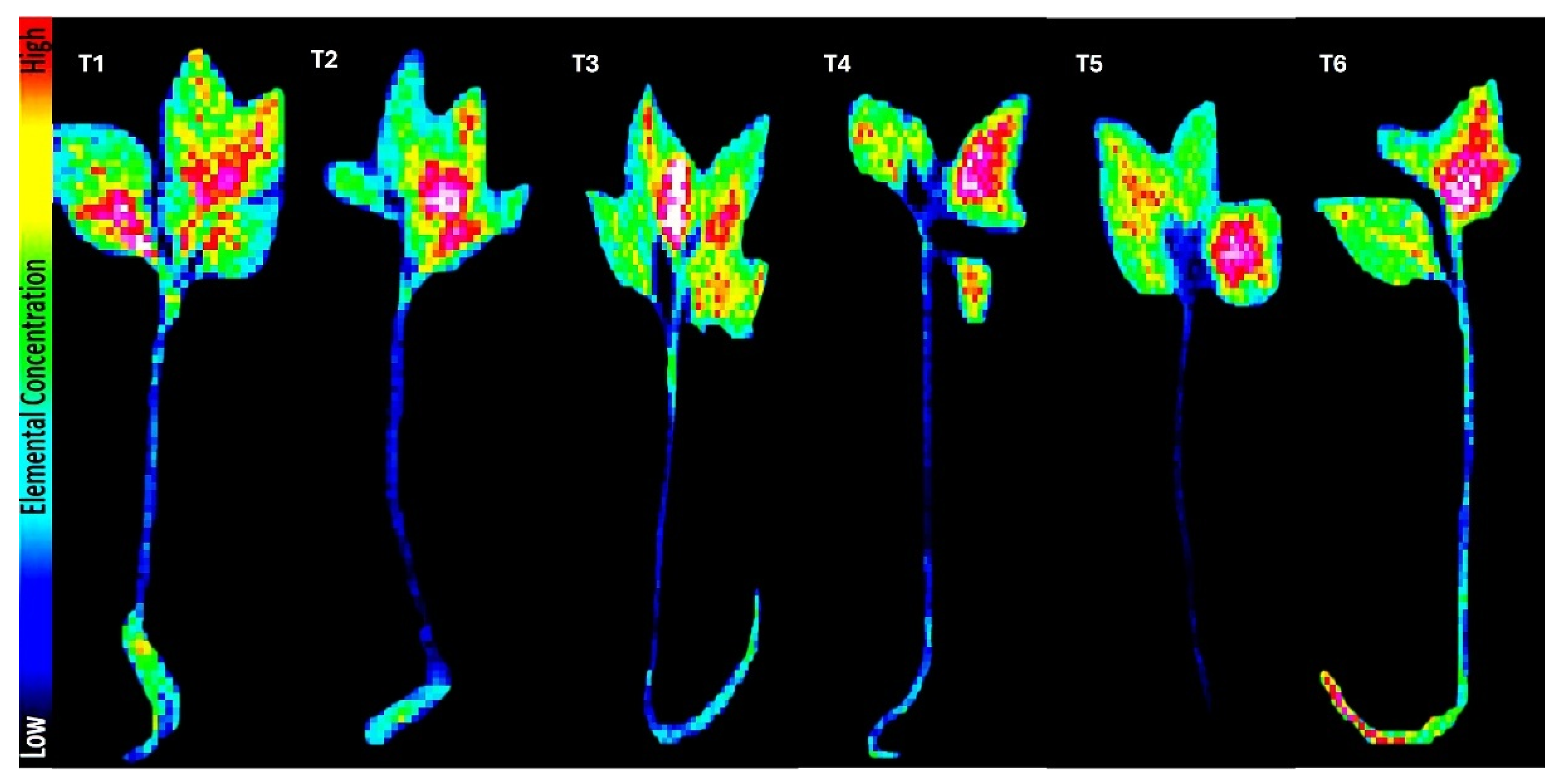

P, being a mobile element, was found in the stem and roots of the seedlings. A similar distribution was observed in most treatments (T1, T2, T3, and Control), except for treatments T4 and T5, which showed lower elemental distribution. This could be due to inhibition of element absorption as a result of a higher concentration of another element, which was observed in the smaller seedlings obtained from these treatments (

Figure 3).

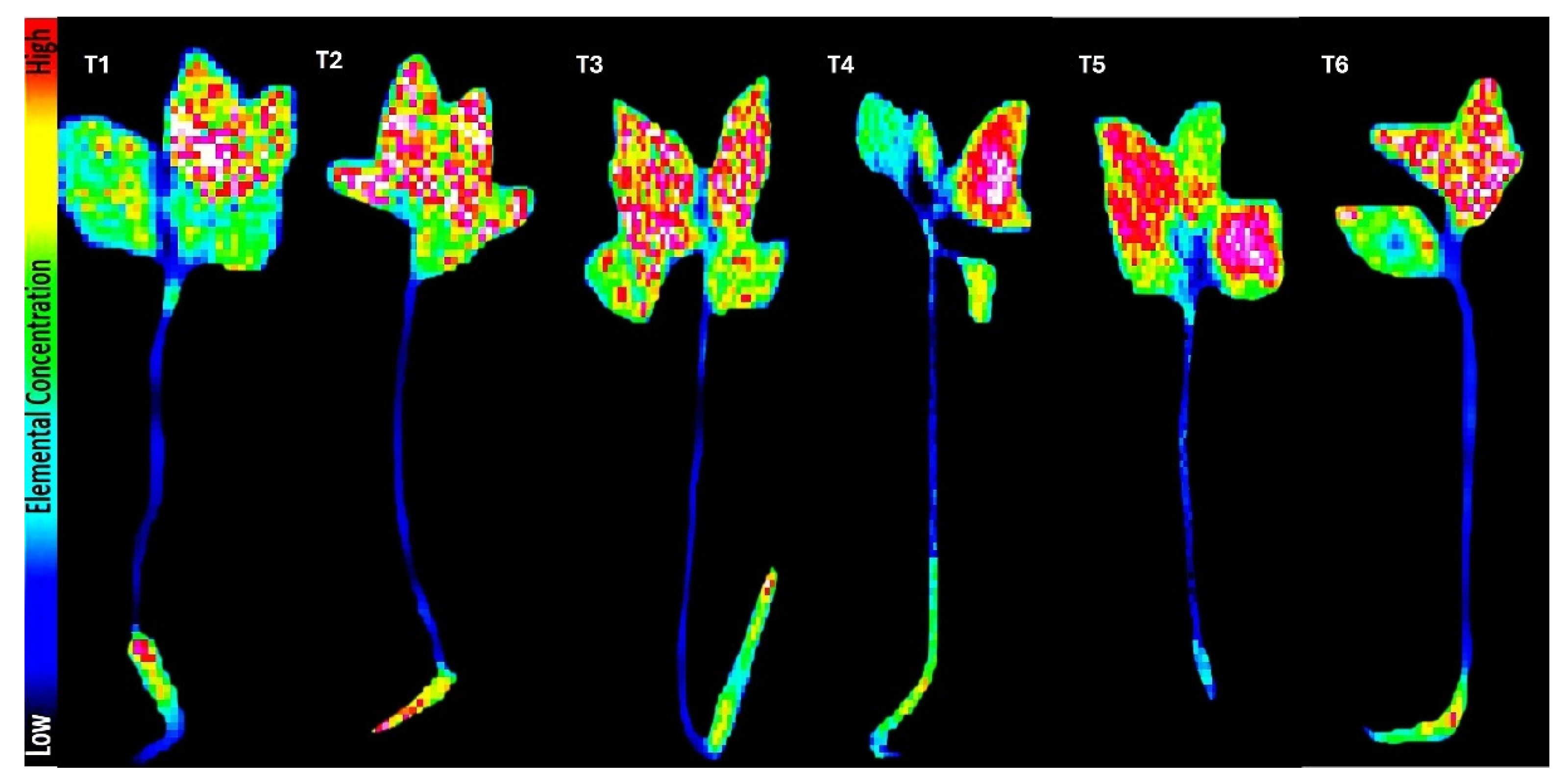

Cl, being a non-essential element for plants, is generally required in low concentrations. However, in treatments with a higher presence of wastewater (T5, T4, and T3), a greater distribution of this element was observed. This is due to the fact that swine wastewater has higher concentrations of this element, which originates from the cleaning of pens and other activities in pig farms. As a result, the seedlings showed higher concentrations. In contrast, treatments with lower dilutions (T1 and T2) and the Control showed lower elemental presence (

Figure 4).

The elemental analysis revealed a high presence of S in treatments with higher concentrations of wastewater (T5 and T4). The prolonged contact time with the wastewater hindered the seedlings’ ability to achieve optimal growth, and also resulted in a decrease in seedling survival due to prolonged intoxication. However, low dilutions of wastewater (T1 and T2) and the Control (T6) showed a lower distribution of S, which favored better growth in the seedlings (

Figure 5).

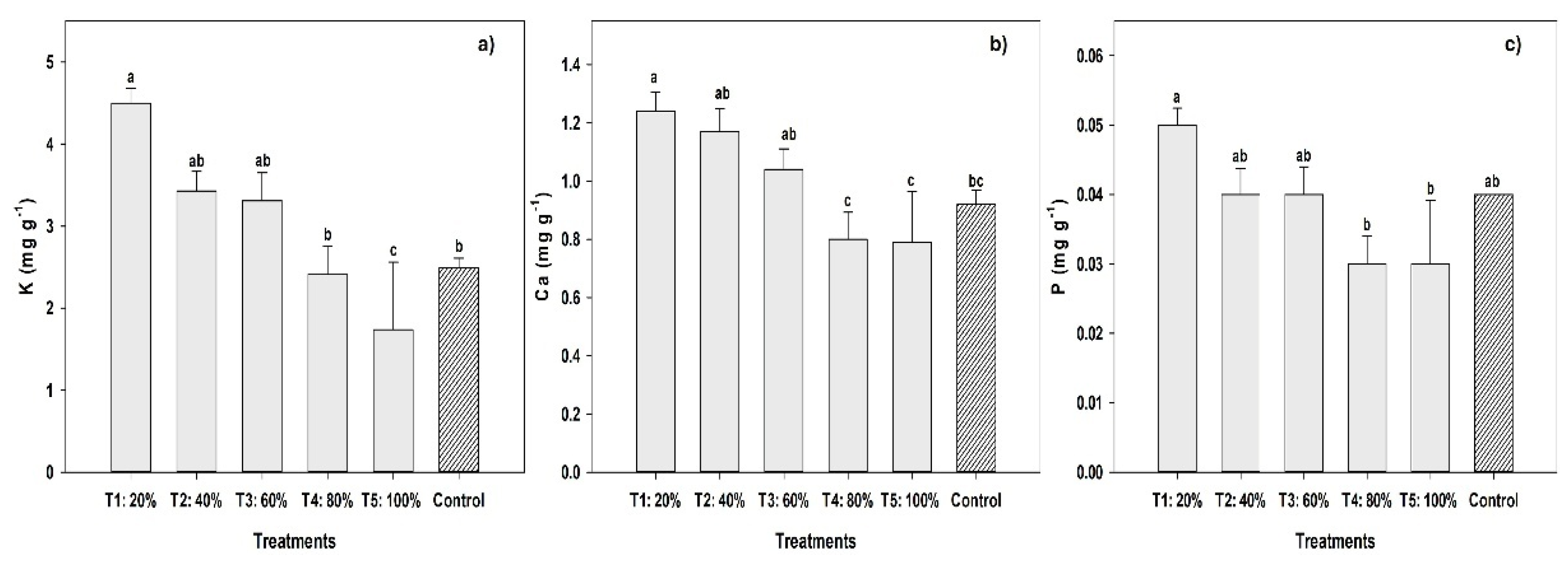

3.4. Concentration of Essential and Non-Essential Elements in Habanero Pepper Seedlings

Swine wastewater played a significant role in the concentration of essential (K, Ca, and P) and non-essential elements (Cl and S) in habanero pepper seedlings. Treatment T1 exhibited the highest concentration of potassium (K) at 4.5 mg g⁻¹, which was 44% higher compared to the control (T6) and more than 60% higher than T5, which had the lowest potassium concentration (1.74 mg g⁻¹) (

Figure 1a). Similarly, calcium (Ca) concentration was highest in T1 (1.24 mg g⁻¹), followed by T2 (1.17 mg g⁻¹) and T3 (1.04 mg g⁻¹), all of which were higher than the Control and treatments with higher wastewater concentrations (T4 and T5) (

Figure 1b). Phosphorus (P) showed a similar trend, with T1 having the highest concentration at 0.05 mg g⁻¹, comparable to the Control (T6: 0.04 mg g⁻¹). In contrast, T4 (0.03 mg g⁻¹) and T5 (0.03 mg g⁻¹) had the lowest phosphorus concentrations (

Figure 1c). These findings demonstrate that the concentration of essential elements in the seedlings was significantly affected by both the nutrient content and the organic load of the swine wastewater. The dilution of the wastewater was crucial for optimizing the absorption of these elements, which in turn supported the proper morphological development of the seedlings.

Figure 6.

Concentration of Essential Elements: K (a), Ca (b), and P (c) in Habanero Pepper Seedlings Irrigated with Swine Wastewater and Its Dilutions. T1: 20% swine wastewater + 80% water; T2: 40% swine wastewater + 60% water; T3: 60% swine wastewater + 40% water; T4: 80% swine wastewater + 20% water; T5: 100% swine wastewater; T6: 100% water (Control).

Figure 6.

Concentration of Essential Elements: K (a), Ca (b), and P (c) in Habanero Pepper Seedlings Irrigated with Swine Wastewater and Its Dilutions. T1: 20% swine wastewater + 80% water; T2: 40% swine wastewater + 60% water; T3: 60% swine wastewater + 40% water; T4: 80% swine wastewater + 20% water; T5: 100% swine wastewater; T6: 100% water (Control).

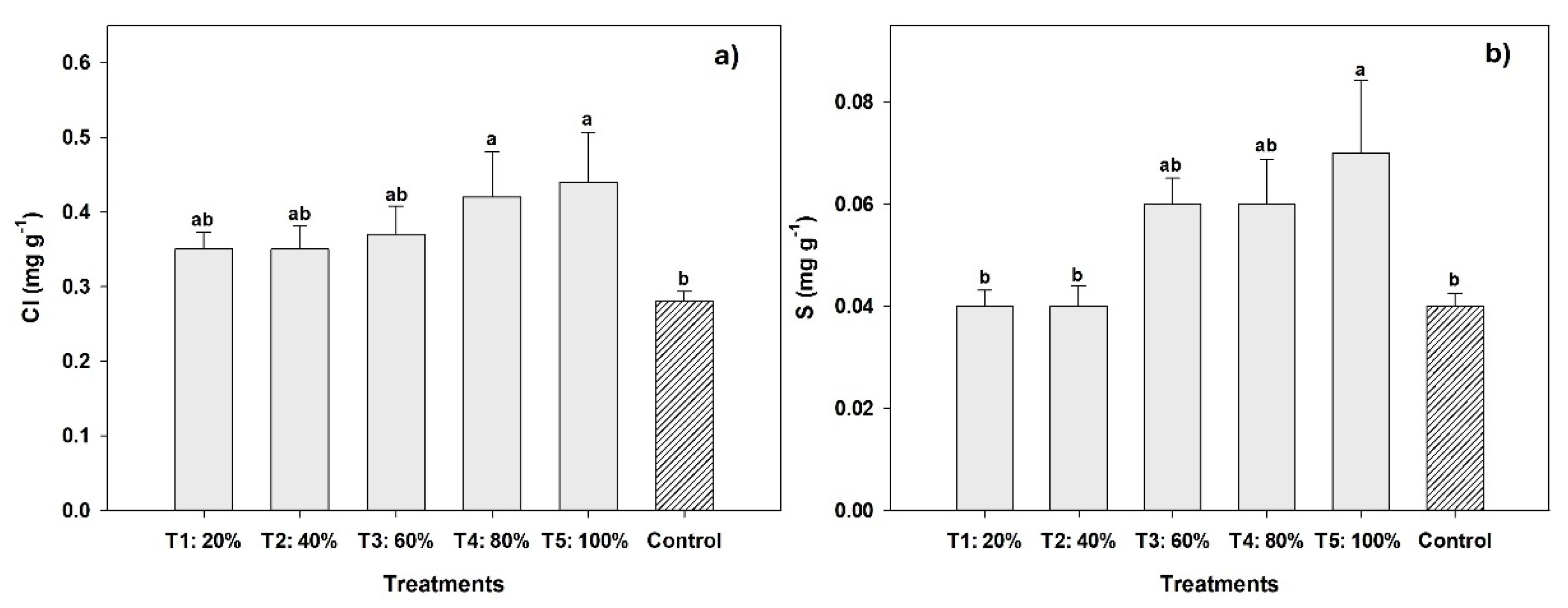

The concentration of Cl and S was highest in treatments T5 (0.44 and 0.07 mg g⁻¹, respectively) and T4 (0.40 and 0.06 mg g⁻¹, respectively). The higher concentrations of these elements can be attributed to activities carried out in swine farms, which increase the levels in the wastewater. Consequently, these higher concentrations were reflected in the seedlings irrigated with the wastewater, leading to toxicity. This toxicity resulted in the death of some seedlings in treatment T5. In contrast, treatments with lower percentages of swine wastewater (T1 and T2), as well as the control, exhibited lower concentrations of Cl and S (

Figure 7). These lower concentrations did not interfere with the interaction of other elements and, in fact, promoted better seedling growth.

3.5. Morphological Characteristics in Habanero Pepper Seedlings

Significant differences were observed in the carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio with respect to the concentration of swine wastewater. Treatments with higher concentrations exhibited higher values: T5 = 4.2 and T4 = 4.07. This indicates that these treatments had a higher nitrogen content in the leaves compared to the other treatments. However, these treatments did not show the highest morphological growth. Regarding seedling height, treatments T1 (8.11 cm) and T6 (7.87 cm) exhibited the greatest growth, while the treatment with the highest wastewater concentration (T5 = 3.31 cm) showed the lowest height. In all growth variables (dry biomass), treatment T1 was statistically superior in terms of dry weight of the stem, root, and total weight (130.94, 41.83, and 172.77 mg, respectively), even surpassing the control treatment. The C/N ratio in treatment T1 allowed for a balance between nitrogen and carbon concentration, promoting enhanced plant growth (

Table 3).

The morphological characteristics obtained led to the production of high-quality seedlings, as evidenced by the higher values in the Stem Index and Dickson Quality Index. The 20% swine wastewater treatment recorded the best values (4.26 and 0.023, respectively), statistically similar to the control (3.85 and 0.022, respectively), but 36% higher compared to T5, which had the lowest indices (2.69 and 0.005, respectively) (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Swine Wastewater

The pH and EC values are critical parameters influencing nutrient availability and uptake in plants. The swine wastewater and its dilutions used in this study showed variations within these parameters, which can fluctuate depending on factors such as pig age, diet, and the treatment system employed [

15]. Treatments with 20% swine wastewater (T1 = 7.5) and the control (T6 = 7.0) maintained a neutral pH, and their EC values were below 3000 µS/cm (

Table 1). These conditions favored a balanced availability and absorption of nutrients by the seedlings. According to [

8], these parameters tend to decrease with lower proportions of swine effluents, and increase with higher concentrations. Conversely, high pH and EC values (>3000 µS/cm) can reduce nutrient uptake efficiency and disrupt plant–nutrient interactions, ultimately leading to nutritional imbalances that adversely affect plant growth, development, and productivity [

16,

17]. This was evident in seedlings under treatment T5, where pH and EC values exceeded optimal thresholds (9.2 and 7233 µS/cm, respectively), resulting in reduced growth (

Table 1 and

Table 3).

Regarding chemical oxygen demand (COD), 100% swine wastewater (T5) exhibited the highest organic load among all treatments. Nevertheless, the observed values were considerably lower than those reported by [

6], who documented COD levels ranging from 3000 to 9000 mg/L in similar effluents. Such variations may be attributed to differences in farm size, herd density, feeding practices, and waste management strategies [

6]. In treatment T1, dilution of the wastewater reduced organic load by 74%, resulting in a COD value of 144 mg/L, while the control registered <20 mg/L (

Table 1), both values notably lower than those reported in the literature.

Swine wastewater typically contains high concentrations of total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), as observed in treatment T5 (711 mg/L), which is primarily attributed to the mixture of urine and undigested feed from pigs. Although the values obtained in this study are lower than those reported by [

3], who found TKN concentrations ranging from 1260 to 2861 mg/L, they still exceed the permissible limits established by the NOM-001-SEMARNAT-2021 standard, which ranges between 15 and 40 mg/L. The 20% dilution of swine wastewater (T1) effectively reduced TKN levels, facilitating the availability of nitrogen for seedling uptake (

Table 1).

Regarding total phosphorus (TP), lower concentrations of wastewater in the treatments increased the availability of the element. Treatment T1 recorded the highest value (11.2 mg/L), which is notably higher than the 4.45 mg/L reported for swine effluents by [

15]. Greater phosphorus availability contributed to improved seedling growth and vegetative development (

Table 1). Several studies have shown that liquid leachates from livestock manure, containing appreciable concentrations of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, enhance growth in tomato and

Capsicum annuum (chile xcat’ik) plants [

18,

19].

4.2. Physiological Responses of Habanero Pepper Seeds

Seeds imbibed with diluted swine wastewater, particularly at 20% concentration (T1), exhibited a significant increase in emergence rate (97%) and uniformity (13.09 seedlings day⁻¹) compared to other treatments (

Table 2). The mineral content present in the diluted wastewater likely facilitated the uptake of key nutrients such N, K, Ca and P enhancing seed metabolic activity and promoting faster and more uniform seedling development. It has been reported that the assimilation and accumulation of essential minerals like N, P, K, and iron during early germination stages can influence internal physiological processes, thereby enhancing vigor and seedling emergence [

20]. However, excessive nutrient concentrations, high organic load, and elevated electrical conductivity (EC) can produce phytotoxic effects, compromising seed performance and viability [

17]. Such negative impacts were evident in treatment T5, which, despite its high elemental and organic content, resulted in poor physiological performance across the evaluated variables (

Table 2).

4.3. Distribution of Essential Elements in Habanero Pepper Seedlings

The distribution of essential elements in habanero pepper seedlings varied according to the concentration of swine wastewater in the treatments. Higher levels of potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P) were observed in treatments T1 (20% wastewater) and T2 (40% wastewater), particularly in key growth zones such as apical meristems and root tips (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). These nutrients are known to play fundamental roles in metabolic processes including protein synthesis, photosynthesis, and energy transfer mechanisms involved in biosynthetic and catabolic pathways [

22]. A higher elemental distribution of K, Ca, and P in T1 and T2 enhanced nutrient activity and availability within the seedlings, which was reflected in increased growth and morphological development. The dilution of raw wastewater appears to have moderated the high organic and nutrient load, promoting better elemental availability and facilitating nutrient uptake and translocation within plant tissues.

Previous studies have shown that nutrient-rich liquid leachates from organic manures enhance the distribution and accumulation of essential elements such as N, P, and K in tomato leaves [

18], and also improve SPAD readings in pepper plants following bovine manure applications [

21]. Similarly, Calero-Hurtado [

23] reported improved growth in bean and cotton plants irrigated with leachates derived from vegetable waste and manures. Swine manure, when properly treated, contains valuable nutrients required for plant development and can serve as a viable alternative to costly chemical fertilizers [

8].

In this context, the favorable elemental distribution observed in T1 and T2, especially in growth regions (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3), underscores the importance of nutrient accessibility during early developmental stages. Essential elements like N, K, Mg, P, Ca, and Fe are closely linked to photosynthetic activity and energy transference in plant systems [

24]. A reduced elemental distribution observed in treatments T4 and T5 limited photosynthetic activity, metabolic processes, and energy transference in the seedlings, which was reflected in diminished vegetative growth (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The excessive organic and nutrient load in undiluted wastewater (T5) appeared to hinder rather than promote elemental distribution, negatively affecting seedling development.

Non-essential elements are generally not required in large quantities by plants, and thus their distribution should be lower compared to macronutrients. However, treatments with higher concentrations of swine wastewater 80% (T4) and 100% (T5) showed increased accumulation of chlorine (Cl) and sulfur (S) in the apical meristems of the seedlings (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The elevated presence of these elements is attributed to their high concentrations in the wastewater, resulting from various management activities on pig farms. Excessive accumulation of Cl and S can disrupt the ionic balance within the plant, hindering the uptake and translocation of other essential elements. This imbalance may lead to elemental deficiencies, water stress, and nutrient toxicity, ultimately impairing biomass accumulation and overall plant growth [

17]. Conversely, treatments with higher wastewater dilutions (T1 and T2), as well as the Control, showed lower levels of Cl and S in the leaves, which likely favored interactions with other nutrients (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Although Cl and S are involved in the synthesis of various secondary metabolites and contribute to key physiological functions, their excess can negatively affect plant development [

25].

Dilutions of swine wastewater at 20% (T1) and 40% (T2) increased the concentration of potassium (K), calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P) compared to the other treatments (

Figure 6), even surpassing the Control treatment (T6). The reduction in organic load due to dilution enhanced the availability and uptake of nutrients present in the wastewater, which was reflected in improved vegetative growth, as the seedlings received adequate amounts of nutrients required for their development. One of the key physiological processes influenced by proper nutrient availability particularly N, P, K, Ca and Fe is photosynthesis. Thus, maintaining an appropriate concentration of essential elements in accordance with the plant’s phenological stage is critical [

24,

26]. The concentrations of N and P are especially important for plant growth, as they play a central role in photosynthesis and energy transfer within the biosynthetic and degradation pathways of metabolism [

12,

22]. Similar results have been reported in

Capsicum annuum L., where the application of goat manure leachate enhanced both leaf number and plant height, likely due to the higher nutrient content in the organic amendment [

12]. In contrast, lower nutrient availability is typically associated with reduced growth and development, as was evident in the treatments with 80% (T4) and 100% (T5) swine wastewater, which recorded the lowest nutrient concentrations and poorest plant performance (

Figure 6).

The higher organic and nutritional load of the pig wastewater (T4 and T5) did not influence the concentration of essential elements, but it did increase the absorption and distribution of S and Cl in the seedlings (

Figure 7). The high concentration prevented the plants from achieving greater growth, simultaneously limiting the absorption of other elements. However, these elements are not required in large quantities by various species [

27], and the amounts required by the plants are generally supplied by rainfall [

28]. Cl accumulates primarily in the chloroplasts of the leaves and is essential for photosynthetic function [

29]. In this context, seedlings from treatments T1 and T2, which registered a lower concentration of the element, showed greater plant growth (

Figure 7). The effects of Cl depend on the species’ sensitivity and the external concentration; high concentrations of Cl can damage leaf cells and, consequently, cause photosynthesis issues [

30]. Regarding S, the treatments with lower concentrations (T1 and T2) exhibited better morphological response, while treatments T5 and T4, with higher values, negatively affected plant growth. Some studies suggest that sulfur concentration influences biomass, general morphology, yield, and nutritional value of plants [

31].

4.4. Morphological Responses of Habanero Chile Seedlings Irrigated with Pig Wastewater

Pig wastewater adversely affected the carbon/nitrogen (C/N) ratio in the treatments. The low C/N ratio was due to the high nitrogen content in the wastewater, meaning that the seedlings absorbed a larger amount of nitrogen. This can promote plant growth in moderate amounts, or, in excess, lead to a nutritional imbalance [

31]. This was observed in T5 (100% wastewater), where the seedlings presented an ionic imbalance that affected their morphology (

Table 3). The treatments with diluted wastewater and the control had a lower range of 3.4-3.7. Although the C/N ratio was lower, this allowed the plants to have greater height and biomass accumulation (

Table 3). Despite the low ratio, the presence of nitrogen influenced the plant’s development. Nitrogen content can enhance protein synthesis and other processes that boost plant growth [

31].

The lower concentration of pig wastewater in T1 (20% wastewater) increased the height and dry biomass accumulation in the stem, roots, and total biomass (

Table 3). The physicochemical parameters in the wastewater were favorable for the interaction between elements, enhancing seedling growth (

Table 1 and

Table 3). Therefore, the nutritional content in the wastewater was a determining factor in plant growth and development. The use of liquid manure and leachates in agriculture has been beneficial for seedling production in nurseries, as well as an alternative production method [

32]. In pepper plants, the application of goat manure leachate increased plant height and leaf number due to the high nutrient content in goat manure [

12]. Similarly, in bean (

Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and cotton (

Gossypium hirsutum) plants, the application of bovine manure leachates improved plant growth [

23,

33].

The values obtained regarding the growth and development of seedlings were fundamental for producing quality seedlings (SSR, DQI)). Specifically, the treatment with 20% pig wastewater (T1) showed the best morphological response in the seedlings, demonstrating higher quality compared to the other treatments, including the control (T6) (

Table 3). These results are consistent with previous studies where bovine and ovine manure leachates were used in seedlings of

Capsicum annuum L. and coffee, where values for the SRR ranged from 4.0 to 4.7 and for the DQI from 0.18 to 0.40 [

34,

35]. In this sense, seedlings produced with diluted pig wastewater represent a viable alternative, with greater vigor and survival, which enhances their successful transplantation in the definitive field.

5. Conclusions

The use of 100% pig wastewater increased the physicochemical parameters, which negatively affected the physiological attributes of the seeds during seedling development. A higher concentration of wastewater reduced the distribution and concentration of K, Ca, and P, while increasing the presence and concentration of Cl and S in the leaves. The use of 100% wastewater had a detrimental impact on the morphology of the seedlings. In contrast, diluting the wastewater to 20% decreased the organic and nutritional load, which enhanced elemental absorption in the seeds and promoted more uniformity and emergence of the seedlings. This dilution increased the distribution and concentration of K, Ca, and P in both the leaves and roots of the seedlings, which in turn enhanced their growth and morphological development. The use of 20% diluted wastewater for seedling production represents a viable alternative for plant production in seedbeds, enabling the production of homogeneous, vigorous, and high-quality plants in a shorter period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H.N., C.D.H.P. and M.V.L.; methodology, C.D.H.P., G.G.V., C.A.L. and C.P.C.; software, M.V.L., C.D.H.P. and G.G.V.; validation, M.V.L., E.H.N., G.G.V., C.A.L. and R.M.N.; formal analysis, M.V.L., C.D.H.P. and C.Q.F.; investigation, E.H.N., C.D.H.P. and G.G.V.; resources, C.A.L., C.P.C. and. C.Q.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H.N., C.D.H.P. and M.V.L.; writing—review and editing, E.H.N., G.G.V. and R.M.N.; visualization, C.D.H.P., C.A.L., and C.P.C; supervision, E.H.N., M.V.L., G.G.V. and C.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the first and corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The first author gratefully acknowledges the support of the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation of Mexico (SECIHTI).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- SIAP-SADER. Producción pecuaria de México. Servicio de Información Agropecuaria, Secretaria de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. México 2019. https://www.inforural.com.

- Bautista, F.; Aguilar, Y.; Díaz, E.; Cano, A.; Ramírez, S. Los territorios kársticos de la península de Yucatán: caracterización, manejo y riesgos. Asociación Mexicana de Estudios sobre el Karst. Ciudad de México. Los suelos como plantas de tratamiento de las aguas residuales porcinas. 2021,196 pp. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352750661 [accessed Apr 2025].

- Bautista, F.; Aguilar, Y.; Gijón-Yescas, N. Las granjas porcinas en zonas de karst: ¿Cómo pasamos de la contaminación a la sustentabilidad? Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 2022, 25: #093. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Valencia, L.H.; García-Reyes, R.B.; Ulloa-Mercado, R.G.; Arellano-Gil, M.; García-González, A. Biotechnological potential for the valorization of waste generated from pig farms and wheat cultivation. Entreciencias: Diálogos en la Sociedad del Conocimiento, 2019, vol. 7, núm. 21, pp. 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Polanco, A.G.; Beilin, K. Toxic bodies: water and women in Yucatan. Hispanic Issues On-Line, 2019, 24, pp. 168-193.

- Valdez-Vázquez, M.; Bobadilla-Vidrio, Y.G.; García-Reyes, R. B. ; Martínez-Rodríguez. C. M.; Alvarez-Valencia, L. H. Influencia de la separación de agua residual porcina en fracciones sólida y líquida, en la producción de metano con Iodo anaerobio granular y disperso. Biotecnia, 2022, vol. 24, núm. 1, pp. 107-115. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wei, Q.; Qiang, Z.; Xuan, W.; Yan, M.; Qing, C. Evaluation of crop residues and manure production and their geographical distribution in China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2018, 188, pp. 954-965. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gutiérrez, A.; Dzul-Mukul, C. R.; Borges-Gómez, L.; Latournerie-Moreno, L.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Ayora-Ricalde, G. Potential use of pork farm effluents for Capsicum chinense production. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2015, Vol. 38 (4) 383 -387,2015.

- Caballero-Salinas, J.C.; Ovando-Salinas, S.G.; Núñez-Ramos, E.; Aguilar-Cruz, F. Sustratos alternativos para la producción de plántulas de tomate de cáscara (Physalis ixocarpa Brot.) en Chiapas. Revista Siembra, 2020, 7(2), 14-21. [CrossRef]

- Preciado-Rangel, P.; García-Hernández, J. L.; Segura-Castruita, M.Á.; Salas-Pérez, L.; Ayala-Garay, A.V.; Esparza-Rivera, J.R.; Troyo-Diéguez, E. Efecto del lixiviado de vermicomposta en la producción hidropónica de maíz forrajero. Terra Latinoamericana, 2014, 32(4), 333-338.

- Durukan, H.; Demirbas, A.; Tutar, U. The effects of solid and liquid vermicompost application on yield and nutrient uptake of tomato plant. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology, 2019, 7(7), 1069-1074.

- Torres-García, A.; Héctor-Ardisana, E.F.; Fosado-Téllez, O.; Cué-García, J.L.; Mero-Muñoz, J.A.; León-Aguilar, R.; Peñarrieta-Bravo, S. Respuesta del pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.) ante aplicaciones foliares de diferentes dosis y fuentes de lixiviados de vermicompost. Bioagro, 2019, 31(3), 213-220.

- Hernández-Pinto, C.; Garruña, R.; Andueza-Noh, R.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Zavala-León, M. J.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, A. Post-harvest storage of fruits: An alternative to improve physiological quality in habanero pepper seeds. Revista Bio Ciencias 2020, 7, e796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, A.; Leaf, A.L.; Hosner, J.F. Quality appraisal of white spruce and white pine seedlings stock in nurseries. The Forestry Chronicle, 1960; 36, 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, M.; Espinosa, S.; Cárdenas, M. Determinación de parámetros del agua residual de una granja porcina en el municipio Torbes, Táchira. Revista científica Unet. Ciencias exactas. 2017, Vol. 29(2): 161-172.

- Bilal, H.M.; Zulfiqar, R.; Adnan, M.; Umer, M.S.; Islam, H.; Zaheer, H.; Abbas, W. M.; Haider, F.; Ahmad, I. Impact of salinity on citrus production; A review. International Journal of Applied Research. 2020, 6: 173-176.

- Amalfitano, C.; Del Vacchio, L.; Somma, S.; Cuciniello, A.; Caruso, G. Effects of cultural cycle and nutrient solution electrical conductivity on plant growth, yield and fruit quality of ‘Friariello’ pepper grown in hydroponics. Horticultural Science. 2017, 44: 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Durukan, H.; Demirbas, A.; Tutar, U. The effects of solid and liquid vermicompost application on yield and nutrient uptake of tomato plant. Turkish Journal of Agriculture-Food Science and Technology, 2019, 7(7), 1069-1074.

- Gamboa-Angulo, J.; Ruíz-Sánchez, E.; Alvarado-López, C.; Gutiérrez-Miceli, F.; Ruíz-Valdiviezo, V.M.; Medina-Dzul, K. Efecto de biofertilizantes microbianos en las características agronómicas de la planta y calidad del fruto del chile xcat’ik (Capsicum annuum L.). Terra Latinoamericana, 2020, 38(4), 817-826. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pinto, C.D.; Alvarado-López, C.J.; Garruña, R.; Andueza-Noh, R.H.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Zamora-Bustillos, R.; Ballina-Gómez, H.S.; Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Samaniego-Gámez, B.Y.; Samaniego-Gámez, S.U. Kinetics of Macro and Micronutrients during Germination of Habanero Pepper Seeds in Response to Imbibition. Agronomy. 2022, Vol. 12, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño-Guerra, J. L.; Héctor-Ardisana, E. F.; Torres-García, A.; Fosado-Téllez, O. Respuestas del crecimiento y el rendimiento en pimiento (Capsicum annuum L.) híbrido Nathalie a un lixiviado de vermicompost bovino. La Técnica: Revista de las Agrociencias, 2020, 2(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Luna-Fletes, J. A.; Cruz-Crespo, E.; Can-Chulim, A.; Chan-Cupul, W.; Luna-Esquivel, G.; García-Paredes, J.D.; Mancilla-Villa, O. R. Producción de plántulas de chile habanero con fertilización orgánica y biológica. Terra Latinoamericana, 2022, 39, e988. [CrossRef]

- Calero-Hurtado, A.; Pérez Díaz, Y.; González-Pardo, H.Y.; Yanes-Simón, L.A.; Peña-Calzada, K.; Olivera-Viciedo, D.; Meléndrez-Rodríguez, J.F. Respuesta agroproductiva de la habichuela a la aplicación de vermicompost lixiviado y microorganismos eficientes. Revista de la Facultad de Ciencias, 2020, 9(1), 112-124. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Kang, Y.G. ; Chang-Yoon, Seok-Kim, J.H. Effects of Zerovalent Iron Nanoparticles on Photosynthesis and Biochemical Adaptation of Soil-Grown Arabidopsis thaliana. Nanomaterials. 2019, 9: 1543. [CrossRef]

- Gohain, B.P.; Rose, T.J.; Liu, L.; Barkla, B.J.; Raymond, C.A.; King, G.J. Remobilization and fate of sulphur in mustard. Ann Bot. 2019, August 16;124(3):471–480. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Terrazas, M.I.; Santillán-Carrillo, I.E.; Holguín-Mina, R.; Sariñana-Aldaco, O. Impacto de la conductividad eléctrica de la solución nutritiva en la biomasa, pigmentos fotosintéticos y compuestos nitrogenados en lechuga. Biotecnia, 2022, 24(3), 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Cázarez-Flores, L. L.; Partida-Ruvalcaba, L.; Velázquez-Alcaraz, T.J.; Ayala-Tafoya, F.; Díaz-Valdés, T.; Yáñez-Juárez, M.G.; López-Orona, C.A. Silicio y cloro en el crecimiento, rendimiento y calidad postcosecha de pepino y tomate. Terra Latinoamericana, 2022, 40, e994. [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s mineral nutrition of higher plants. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press. 2011.

- Tingxuan, L.; Changquan, W.; Guorui, M.; Xizhou, Z.; Rensui, Z. Research progress of chloride-containing fertilizers. Southwest China Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 2022, 15(2), 86-91.

- Geilfus, C.M. Review on the significance of chlorine for crop yield and quality. Plant Science, 2018, 270, 114-122. [CrossRef]

- Jobe, T.O.; Zenzen, I.; Rahimzadeh-Karvansara, P.; Kopriva, S. Integration of sulfate assimilation with carbon and nitrogen metabolism in transition from C3 to C4 photosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2019, 70(16):4211–4221. [CrossRef]

- Alatorre-Rosas, R.; Quero-Carrillo, A.R.; Miranda-Jiménez, L.; Ramírez-Alarcón, S.; Villanueva-Verduzco, C.; Jarquín-Nieto, I.A.; Villanueva-Sánchez, E. Biofertilizantes: la solución a la productividad en el campo. Texcoco, Estado de México, México: Universidad Autónoma Chapingo-Colegio de Postgraduados. 2015.

- Chinga, W.; Torres-García, A.; Chirinos, D.T.; Marmol, L.E. Efecto de un lixiviado de vermicompost sobre el crecimiento y producción del algodón. Revista Científica Ecuatoriana, 2020, 7(2), 32-40. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo-Alcalá, P.; Cruz-Hernández, J.; Taboada-Gaytán, O.R. Abonos orgánicos comerciales, estiércoles locales y fertilización química en la producción de plántula de chile poblano. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana, 2020, 43(1), 35-44. [CrossRef]

- Julca-Otiniano, A.; Borjas-Ventura, R.; Bello-Amez, S.; Ladera-Manyari, Y.; Rebaza-Fernández, D. El crecimiento del café var. Caturra roja y su relación con la aplicación de abonos orgánicos. Revista de la Facultad de Ingeniería de la USIL, 2015, 2(2), 75-89.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).