1. Introduction

FMS-related tyrosine kinase-3 (FLT3) is a receptor tyrosine kinase expressed on hematopoietic stem cells and early myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells. Regular physiologic interaction of FLT3 ligand with the FLT3 receptor promotes cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation via activation of the PI3K, STAT5, and RAS signaling pathways [

1]. The FLT3 receptor is encoded by the

FLT3 gene on chromosome 13, which consists of 24 exons and spans approximately 96 kb in length [

2]. Up to 30% of newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients have constitutive activation of the FLT3 receptor, predominantly caused by two types of mutations, resulting in increased downstream signaling that contributes to leukemogenesis. The most common types are internal tandem duplications (ITDs), which are in-frame insertions of a sequence of nucleotides that occur within the juxtamembrane domain (JMD) of the receptor (in approximately 25% of AML cases), followed by point mutations in the receptor protein’s second tyrosine kinase domain (TKD) (in approximately 5-7% of AML cases) [

1]. The latter most commonly involves codon 835 (e.g., p.Asp835Tyr), with a few cases reported for mutation or deletion of codon 836 [

3].

The presence of FLT3-ITD, a driver mutation, is associated with a high leukemic burden, significantly increased risk of relapse, and reduced overall survival. Consequently, AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutation(s) often require allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the first remission [

4]. These patients and those with FLT3-TKD mutations also benefit from adding FLT3 inhibitors, such as midostaurin, to induction chemotherapy [

5,

6]. Given these clinical implications, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European LeukemiaNet guidelines recommend routine molecular testing for

FLT3 mutations in all AML patients as part of the diagnostic workup [

7,

8] and for consideration in clinical trial enrollment [

7].

For providing rapid FLT3 mutation assay results, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) fragment analysis is the preferred technique for detecting ITD and TKD mutations [

4]. The most commonly used PCR assays are based on the design reported by Murphy et al. over 20 years ago [

9]. This assay simultaneously tests for the presence of both ITDs and codon 835/836 (i.e., TKD) mutations using PCR amplification with fluorescently labeled primers (and, for TKD mutations, subsequent restriction enzyme digestion) followed by fragment analysis using capillary electrophoresis (CE) readout to determine the size of the post-PCR amplicons [

9]. CE provides precise ITD mutation sizing and allows wild-type (wt) to mutated peak ratio calculation that may provide prognostic information [

9,

10,

11]. Alternatively, polyacrylamide (slab) gel electrophoresis (PAGE)-based readout can also be used [

12], although it does not allow precise ITD sizing or determination of ITD to wt peak ratio.

However, both CE and especially PAGE are relatively lengthy and technically demanding result readout modes. Therefore, to simplify the assay and further reduce its turnaround time, here we present a modification of the standard FLT3 PCR assay. This modification involves using the Agilent TapeStation system for result readout, which outputs electropherograms (EPGs) and gel images in less than two minutes with only 1-2µL of sample. As TapeStations are widely used in molecular diagnostics laboratories as part of next-generation sequencing (NGS) protocols, they could also be effectively repurposed for other applications, such as shown here for rapid and cost-effective FLT3 PCR testing.

2. Materials and Methods

We validated a modified PCR assay using the TapeStation instrument (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to detect FLT3-ITD and TKD mutations using 22 and 18 previously tested patient samples, respectively. All patient specimens used in the validation study previously underwent routine FLT3-ITD and TKD mutation assay by PCR, followed by PAGE-based readout [

12] and subsequent NGS testing.

The modified PCR assay consists of the following steps for the detection of ITD and TKD mutations: 1) DNA isolation; 2) DNA quantification by spectrophotometry; 3) PCR with two sets of primers, one set for ITD and one set for TKD mutations; 4) EcoRV digestion of PCR amplicons, done only for TKD mutation detection; 5) Fragment analysis using the TapeStation instrument; 6) Result interpretation by the TapeStation analysis software.

Steps 1&2. DNA isolation and quantification: Peripheral blood and bone marrow samples of at least 0.5 ml received in EDTA vacutainers (blue top) at 2-8°C were used for the assay. Frozen or severely hemolyzed samples received without appropriate patient identifiers and incomplete or no requisition forms were rejected. DNA extraction was performed using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or a Promega Maxwell® RSC Extractor using the Blood DNA Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). The DNA concentration was measured post-extraction using the NanoDrop One Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Step 3. PCR setup: ITD variants predominantly involve exon 14 of the

FLT3 gene and sometimes a portion of exon 15. The first set of primers detects ITDs of varying sizes, ranging from 15- 204bp, including those extending into exon 15, [

13,

14,

15]. The primers used are FLT3-11F (forward primer) and FLT3-11R (reverse primer) (

Table 1), aligning with the previous identification of exon 14 as exon 11 [

14]. The second primer set is designated as FLT3-AF & FLT3-AD (

Table 1). Two master mixes were prepared for FLT3-ITD and TKD mutation assays with an optimum DNA input of 50ng. The DNAs were amplified using different thermal cyclers (Eppendorf MasterCycler, Model 53331, VeritiPro, ABI 9700, ABI PTC-100).

Step 4. EcoRV digestion: The wild-type sequence at codon 835 of the FLT3 gene is at an EcoRV recognition site (GATATC). Missense mutations in codons 835 or 836 alter the EcoRV recognition site, and this biological consequence of the mutation itself is exploited for the assay. Therefore, post-PCR, the EcoRV restriction enzyme was added to the TKD test’s PCR product, and the tubes were incubated at 37°C overnight to ensure complete restriction site digestion. The PCR products for ITD detection were also incubated at room temperature for at least 2 hours before being directly loaded onto the TapeStation for fragment analysis.

Step 5. TapeStation automated electrophoresis: The TapeStation 4200 System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) is an automated electrophoresis instrument that uses the Agilent D1000 ScreenTape assay (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA.) to analyze DNA fragments from 35 to 1,000bp in size. The samples were loaded onto the ScreenTape devices and inserted into the TapeStation 4200 deck. A D1000 buffer containing the upper and lower DNA markers was loaded into wells in the TapeStation instrument. The analysis software outputs EPGs and gel images. The amplicon sizes of the test samples were compared against the electronic ladder and upper and lower DNA markers (

Supplemental Figure S1). The software automatically assigns base pair (bp) lengths to each peak and some quantitative data regarding the concentration, molarity, and percentage of the incorporated area. The results obtained from TapeStation were validated by comparing them with those of prior PAGE and/or NGS using the TruSight Myeloid Sequencing Panel on the MiSeqDx platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) or the Oncomine Myeloid Assay on the Genexus platform (ThermoFisher, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Step 6. Interpretation: Controls: Every run includes positive (i.e., sensitivity), negative-, and no-template controls (NTC). The positive controls for ITD and D835 mutations were prepared at 4% and 5%, respectively. A run was deemed acceptable only if the NTC lacked any signal.

ITD mutations: The germline band size using the 11F/11R primers is approximately 150bp in size (

Supplemental Figure S2A and lane H3 in 2B). The germline peak size was determined by testing 42 patients and control samples with an acceptable range of 144-156bp (± 3 standard deviations). The size and shape of the germline peaks (whether broader or narrower) can be influenced by the variability in PCR amplification and the amount of sample pipetted into the TapeStation. Any additional larger peak(s) indicate an ITD (

Supplemental Figure S2B, including lane A4).

Codon 835/836 mutations: The size of the undigested wild-type amplicon is approximately 184bp (

Supplemental Figure S3A and lane F4 in 3D). Amplicons generated from wild-type DNA post-

EcoRV digestion are approximately 94, 56, and 25bp in size (

Supplemental Figure S3B and lane F6 in 3D). However, the 25bp band coincides with the low molecular weight marker and is thus not assessed in the analysis. TKD mutations at codons 835 or 836 create restriction fragments of approximately 54, 92, and 156 bp in size (

Supplemental Figure S3C and lane G6 in 3D) post-

EcoRV digestion (while the undigested sample, just as the wt, shows a single peak at approximately 184bp (see lane G4 in

Supplemental Figure S3D). The absence of this peak post-digestion indicates the completeness of the restriction site digestion. A positive result is acceptable only if the 156bp band has a relative intensity more than or equal to the respective band of the 5% sensitivity control.

4. Discussion

Despite the widespread use of NGS in oncology diagnostics, rapid PCR-based testing for FLT3-ITD and TKD mutations remains standard practice in many clinical molecular diagnostics laboratories. This is due, in part, to the continued challenge of detecting very large ITDs by NGS, and also to quickly informing oncologists of the potential benefit of using FLT3 inhibitors in the induction cocktail for AML patients.

Post-PCR fragment analyses are typically performed by CE, or less frequently by PAGE. Both methods separate DNA amplicons by charge and size. In PAGE, the DNA molecules move through a slab gel matrix, forming bands that are viewed after staining and compared to a standard. In CE, fluorescently-labeled DNA molecules travel through a narrow tube filled with a fluid or gel, and a detector measures the separated components as peaks on an electropherogram for analysis.

PAGE provides high separation efficiency at minimal cost, making it one of the most widely used methods, especially in technology-restricted settings. However, the laborious process of PAGE and the increased technician time required are disadvantages for clinical laboratories with high throughput [

16]. CE-based methods offer faster separation and higher resolution because the thin tubes have a higher surface-to-volume ratio than slab gels, allowing for quicker heat dissipation and operation at high voltages without overheating. The narrow capillary tubes also enhance separation efficiency by reducing the lateral diffusion of molecules. One of the most significant advantages of CE is its ability to be completely automated, but it comes with a higher cost, and its run time is still non-negligible (

https://www.labcompare.com/10-Featured-Articles/585409-Tech-Compare-Capillary-vs-Gel-Electrophoresis).

In contrast, the TapeStation performs automated gel electrophoresis and is widely used to assess nucleic acid size, concentration, and integrity throughout the NGS library preparation process. The 4200 TapeStation system can run as many as 96 DNA samples (i.e., one can load 6 ScreenTape cartridges at a time, with 16 samples per cartridge) on a single plate, which can be completed in less than 20 minutes while eliminating contamination and carryover. Unlike PAGE, the automated analysis is more reproducible, avoiding the variabilities that could arise from using gels, staining, and UV photography in the PAGE technique. Another significant advantage of the TapeStation instrument is that partially used ScreenTape cartridges can be stored at 4°C for up to two weeks and reused any time before the expiry date. Moreover, the TapeStation offers full scalability with a constant cost per sample. A sample quantity as low as 2µL is sufficient to obtain accurate sizing of the amplicons.

In the current study, the TapeStation analysis identified all the ITD mutations detected by NGS and PAGE, demonstrating 100% concordance with these methods. Smaller ITDs are expected to form a shoulder close to the germline peak at ~150bp because only a smaller sequence of nucleotides is duplicated (

Figure 1A and

Figure 2A,

Supplemental Figures S2B and S4A). The peak is displaced towards the upper marker, with the ITD increasing in size (

Figure 1B,

Supplemental Figure S4B,C). The difference between the ITD and germline peak sizes generally correlates with the ITD size detected by NGS. For example, in

Figure 1A, the difference between the germline (150bp) and ITD peaks (164bp) is 14bp, close to the 15bp size reported by the NGS bioinformatics software. A similar finding could be observed in other cases (

Figure 2A,

Supplemental Figure S4A–C). However, this observation is only based on individual cases, and we did not perform any statistical correlation between ITD sizes determined by PCR and NGS methods. Spencer et al. identified an excellent concordance between the ITD sizes determined by PCR and NGS-based methods [

17]. However, in one of our samples (#1227-22), TapeStation revealed a 296bp peak farther from the germline peak, reported as 18bp on NGS rather than the expected 146bp (

Supplemental Figure S4C). One possibility for this discrepancy is PCR bias, which refers to the preferential amplification of shorter ITD inserts over the longer ones during DNA amplification. This leads to the underrepresentation of larger ITDs in the final DNA library, resulting in inaccurate detection and quantification [

18]. Another reason could be due to the misalignment and misassembly of the duplicated sequence by the bioinformatics pipeline, as observed by Spencer et al. [

17]. In our laboratory, we use an in-house developed algorithm for ITD detection by NGS, called “IndelDuper”. It is possible that our in-house developed pipeline under-called this particular ITD. We identified a recent case (not included in the validation set), #6325-24, which showed ITD misalignment by NGS and VAF drop-off (

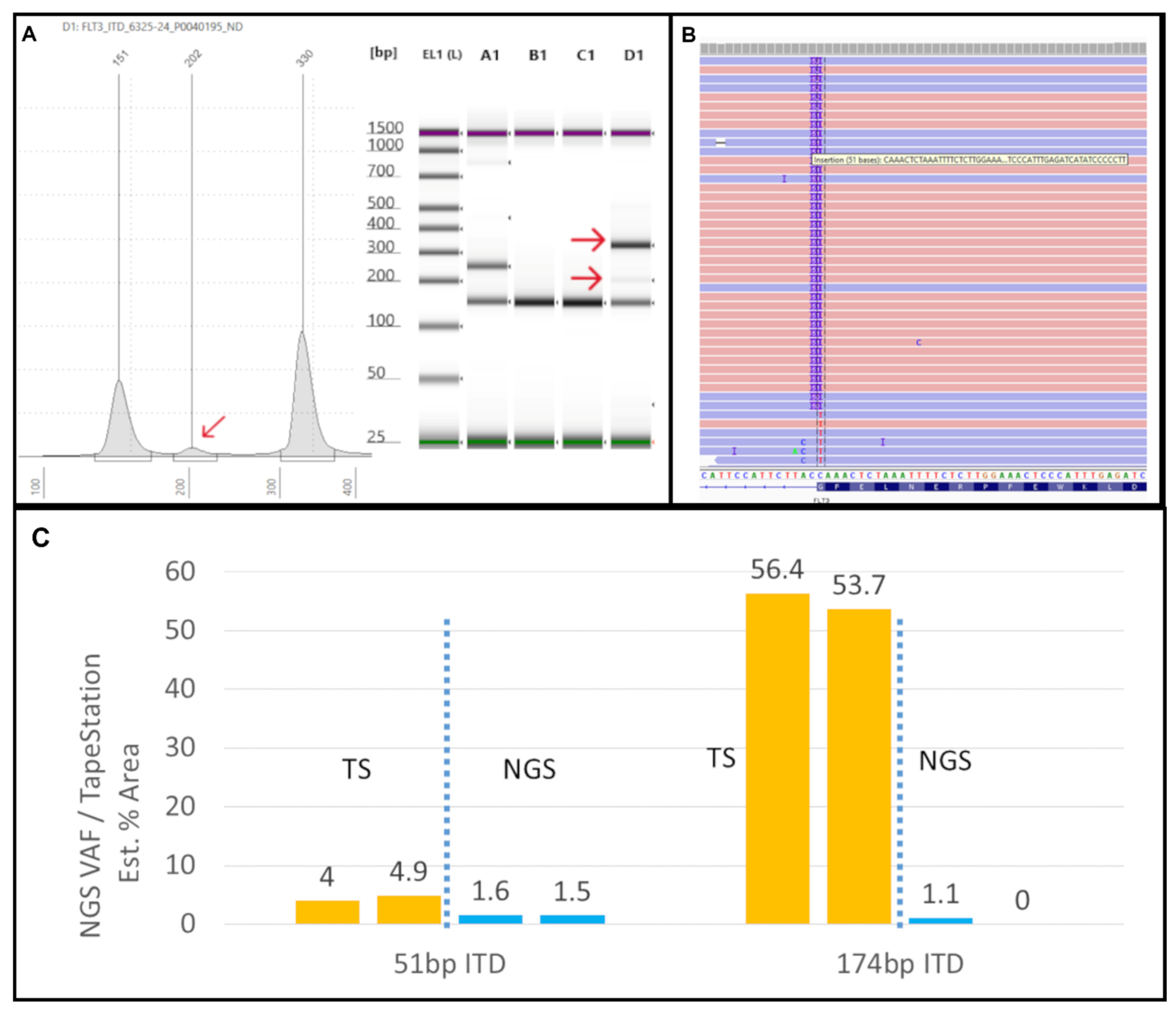

Figure 3). TapeStation showed 2 ITDs at 51bp and 174bp. The 51bp ITD was called at 1.6% VAF, which is concordant with the peak height by TapeStation (

Figure 3C). However, the 174bp was called twice by NGS due to a misalignment, leading to ITDs being called at both 173 and 174bp. These were called at 0.6% and 0.5%, leading to a combined VAF of 1.1%. However, based on the % area calculated from the TapeStation and the prominent peak, the true VAF appears closer to 50%. Indeed, we observed increasing VAF drop-offs for ITDs larger than 70bp.

The sensitivity of PCR fragment analysis with CE for FLT3-ITD is around 5% [

9,

10]. In line with the existing literature, the sensitivity of the TapeStation assay is 4%, and it is also effective in detecting weak positive ITDs with peak intensities much lower than the sensitivity control, suggestive of low VAF by NGS (

Figure 2A,

Supplemental Figure S4A,C). In most cases, low-intensity peaks had low VAFs compared to high-intensity peaks, but we did not perform a statistical analysis to compare the correlation between peak intensity on the TapeStation electropherogram and VAF by NGS. However, one case (#4902-22) with a large 204bp ITD showed a high-intensity peak with a VAF of 1% (

Supplemental Figure S4B). A more recent sample from the same patient showed the same discrepancy. Since our fragment length for NGS is 300bp, the ITD could have been significantly under-called by the bioinformatics algorithm due to its inability to align large ITD sequences. Our lowest VAF for ITD, successfully detected by the TapeStation software, is 0.5% (

Figure 2). Although we were not confident signing out the very low-intensity cases as frankly positive for ITD, repeat testing and careful manual inspection using the overlay view strengthened the suspicion for ITD and alerted the clinician. In many cases, in correlation with the final NGS result, such cases were confidently signed out as positive. While we reported a 100% concordance with NGS, some studies found a slightly lower concordance using the CE, the most widely used fragment analysis method [

17,

19]. This could be attributed to the differences in sample sizes, PCR-based methods, and the vast heterogeneity in bioinformatics pipelines used across various molecular labs. In summary, the sensitivity of our TapeStation assay was enhanced by resorting to careful manual inspection of the peaks and using an overlay view for low-level ITDs. The importance of manual review was also reiterated by Spencer et al. [

17].

Regarding FLT3 TKD variants, D835Y is the most common codon 835 mutation described in the literature, with few documented cases of D835H and D835E. Deletion of codon 836 occurred in 10.2% of cases in a large study comprising 3082 patients [

20]. TapeStation analysis identified the most common D835Y variant and detected the D835E (

Figure 5A), D835H (

Figure 5B and lane D5), and I836del variants (

Figure 5C–E). The results of TapeStation are in 100% concordance with NGS for codon 835/836 mutation analysis.

The I836del variant represents the deletion of isoleucine in the activation loop (A-loop) of the FLT3 TKD domain. Although less common than D835 mutations, it is considered a hotspot due to constitutive activation of the FLT3 receptor [

21]. The codon 836 deletion (and another specimen that harbored a

FLT3 D835del) showed a high molecular weight extraneous band on both digested and undigested samples on TapeStation. This is consistent with the results of PAGE and seems unique to these deletion mutations. Although incomplete digestion can cause extraneous peaks, it may not be the case here, as it was also detected in undigested samples. While we do not understand the reason for the presence of the extra peak, it is reproducible and highlights the presence of FLT3 codon 835/836 single amino acid deletion mutants.

The TapeStation analysis had an intra-run reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity of 100% for detecting TKD mutations. For the inter-run reproducibility study, one of the five samples showed a discrepancy with varied peak sizes between the two replicates. Notably, this sample had lower sensitivity (1.6%) than the positive control (5%), as verified by NGS. Such a discrepancy might be resolved by correlating with NGS on low-sensitivity samples. The ability to overlay and compare electropherograms of samples and controls makes visual inspection seamless and allows the detection of weak mutations. In the past, Mehta et al. also developed a home-brew assay for post-PCR fragment analysis using the TapeStation 4200 instrument for detecting MET exon 14 skipping mutations, with a reported concordance of 84.6% with NGS results [

22].

Three samples from the overall validation data showed both ITD and TKD mutations, and TapeStation results were concordant with NGS and PAGE results in all three cases (

Supplemental Table S5). The prevalence of dual ITD-TKD mutations in AMLs was reported as 1.7% (n=979) and 26% (n=452) in two studies, but their prognostic impact is unclear [

3,

23]. In an in vitro study, dual FLT3 ITD and TKD mutations have been implicated in resistance to FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in AML [

24].

A limitation of the modified assay is that very short insertions (VSI) and indels in the FLT3 juxtamembrane domain can not be detected via Tapestation readout. This limitation is significant, as FLT3 VSIs have been shown to behave similarly to average sized FLT3 ITDs with similar FLT3 inhibitor sensitivity profiles [

25]. Therefore, this assay is best suited as a companion test for rapid NGS platforms in diagnosing AML but is not appropriate for standalone FLT3 testing, where CE-based readout remains the standard.

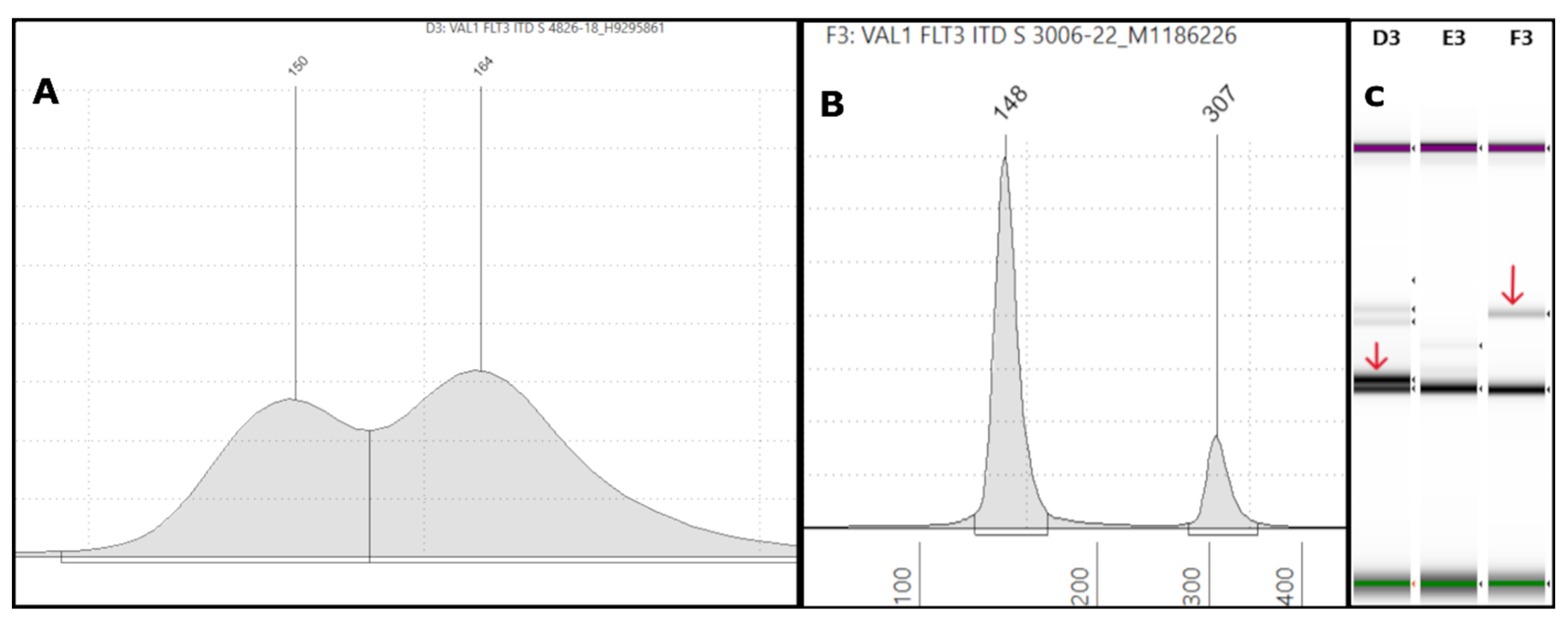

Figure 1.

Representative FLT3-ITD Tapestation results: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #4826-18 with a 164bp peak forming a shoulder near the 150bp germline peak, indicative of a smaller ITD, is shown. The intensity of the peak is high, suggesting a high variant allele frequency (VAF). The corresponding NGS showed a 15bp ITD with 40% VAF. (B) On the left side, the EPG of sample #3006-22 shows a high molecular weight peak at 307bp. Corresponding NGS revealed a large 153bp ITD in exon 15 with 6% VAF. (C) The corresponding gel image shows in lane D3 (sample #4826-18) a 164bp band with an intensity close to the 150bp germline band (red arrow), correlating with the high VAF of 40% on NGS. Lane F3 (sample #3006-22) shows a faint band well above the germline band (red arrow), consistent with the large 307bp ITD of low VAF (6%) by NGS.

Figure 1.

Representative FLT3-ITD Tapestation results: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #4826-18 with a 164bp peak forming a shoulder near the 150bp germline peak, indicative of a smaller ITD, is shown. The intensity of the peak is high, suggesting a high variant allele frequency (VAF). The corresponding NGS showed a 15bp ITD with 40% VAF. (B) On the left side, the EPG of sample #3006-22 shows a high molecular weight peak at 307bp. Corresponding NGS revealed a large 153bp ITD in exon 15 with 6% VAF. (C) The corresponding gel image shows in lane D3 (sample #4826-18) a 164bp band with an intensity close to the 150bp germline band (red arrow), correlating with the high VAF of 40% on NGS. Lane F3 (sample #3006-22) shows a faint band well above the germline band (red arrow), consistent with the large 307bp ITD of low VAF (6%) by NGS.

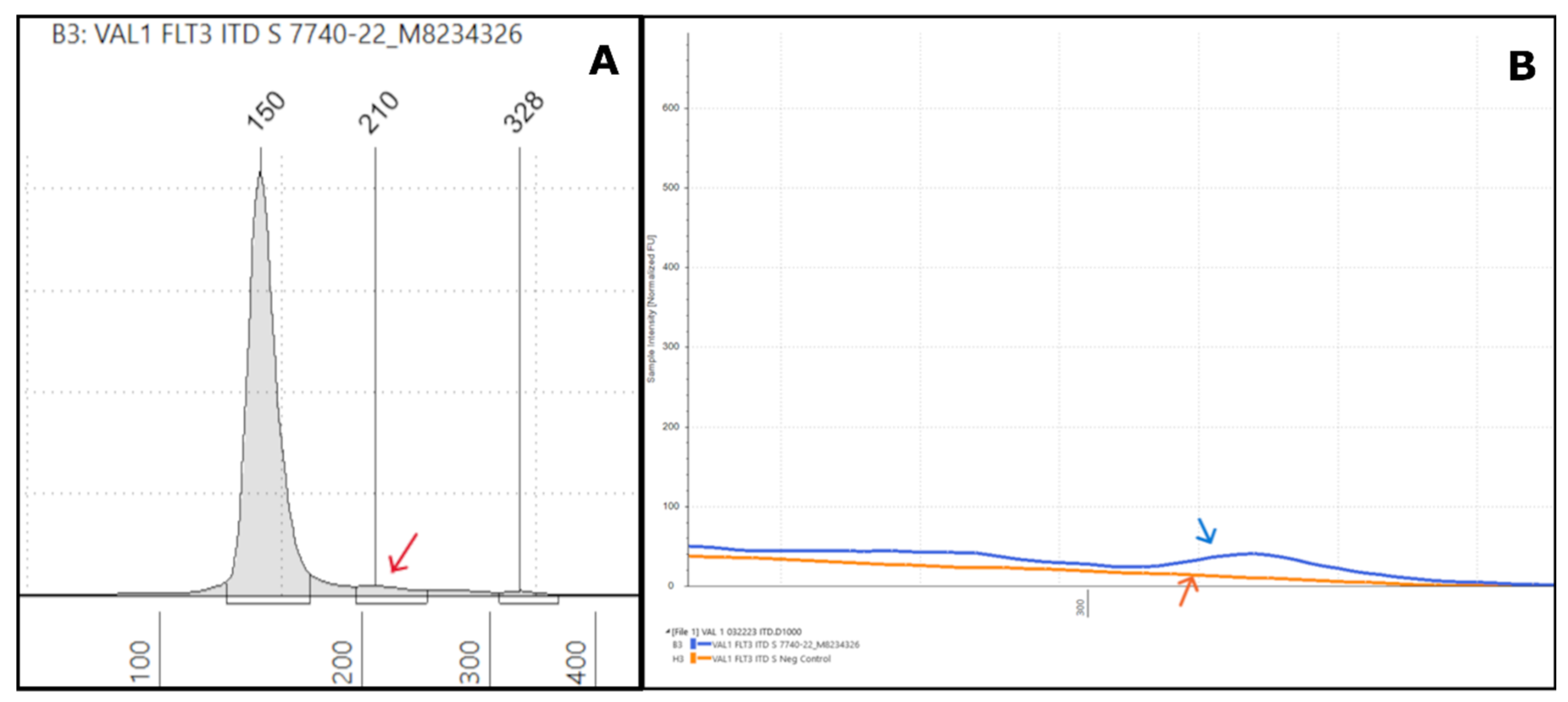

Figure 2.

Representative low-VAF FLT3-ITD Tapestation results: (A) An electropherogram of sample #7740-22 shows a weak positive ITD with a low-intensity peak at 210bp (red arrow), which was 63bp in size with <0.5% VAF by NGS. (B) The overlay image shows a similar but slightly higher intensity for the ITD (blue arrow) than the negative control (orange arrow).

Figure 2.

Representative low-VAF FLT3-ITD Tapestation results: (A) An electropherogram of sample #7740-22 shows a weak positive ITD with a low-intensity peak at 210bp (red arrow), which was 63bp in size with <0.5% VAF by NGS. (B) The overlay image shows a similar but slightly higher intensity for the ITD (blue arrow) than the negative control (orange arrow).

Figure 3.

Tapestation uncovers low-VAF FLT3-ITD not detected by NGS: (A) On the left, an electropherogram (EPG) of sample #6325-24 shows two ITDs of 202 (red arrow) and 330bp size. On the right, the corresponding gel image in lane D1 shows faint and bright bands at 202 and 330bp, respectively (red arrows). (B) The Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) image for sample #6325-24 shows only the 51bp ITD at a VAF of 1.5%. (C) The two ITD peaks are clear in the TapeStation (TS) EPG (run in duplicate). By NGS, the 51bp ITD was present at 51bp in IGV, but the 174bp ITD was not found at all in IGV (0%) and was only detected by the Genexus OMAv2 software (1%).

Figure 3.

Tapestation uncovers low-VAF FLT3-ITD not detected by NGS: (A) On the left, an electropherogram (EPG) of sample #6325-24 shows two ITDs of 202 (red arrow) and 330bp size. On the right, the corresponding gel image in lane D1 shows faint and bright bands at 202 and 330bp, respectively (red arrows). (B) The Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) image for sample #6325-24 shows only the 51bp ITD at a VAF of 1.5%. (C) The two ITD peaks are clear in the TapeStation (TS) EPG (run in duplicate). By NGS, the 51bp ITD was present at 51bp in IGV, but the 174bp ITD was not found at all in IGV (0%) and was only detected by the Genexus OMAv2 software (1%).

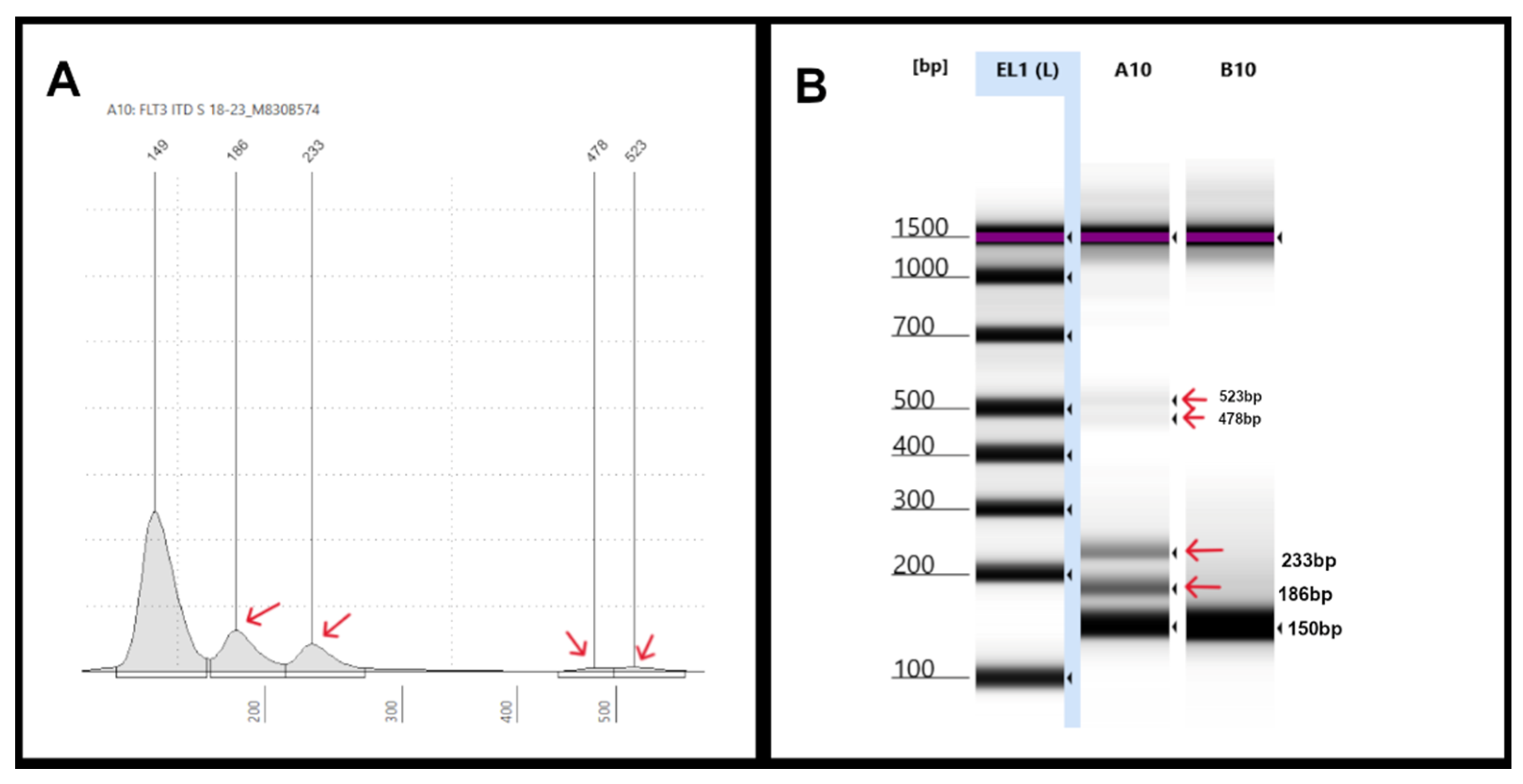

Figure 4.

Representative Tapestation result of samples with multiple FLT3-ITDs: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #18-23 shows two ITDs with peaks at 186bp and 233bp (red arrows). Small additional peaks were also seen at 478bp and 523bp (red arrows). (B) Gel image of sample #18-23 in lane A10 shows two bright bands corresponding to the 186bp and 233bp (red arrows) and two faint bands indicative of the non-specific peaks seen on EPG.

Figure 4.

Representative Tapestation result of samples with multiple FLT3-ITDs: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #18-23 shows two ITDs with peaks at 186bp and 233bp (red arrows). Small additional peaks were also seen at 478bp and 523bp (red arrows). (B) Gel image of sample #18-23 in lane A10 shows two bright bands corresponding to the 186bp and 233bp (red arrows) and two faint bands indicative of the non-specific peaks seen on EPG.

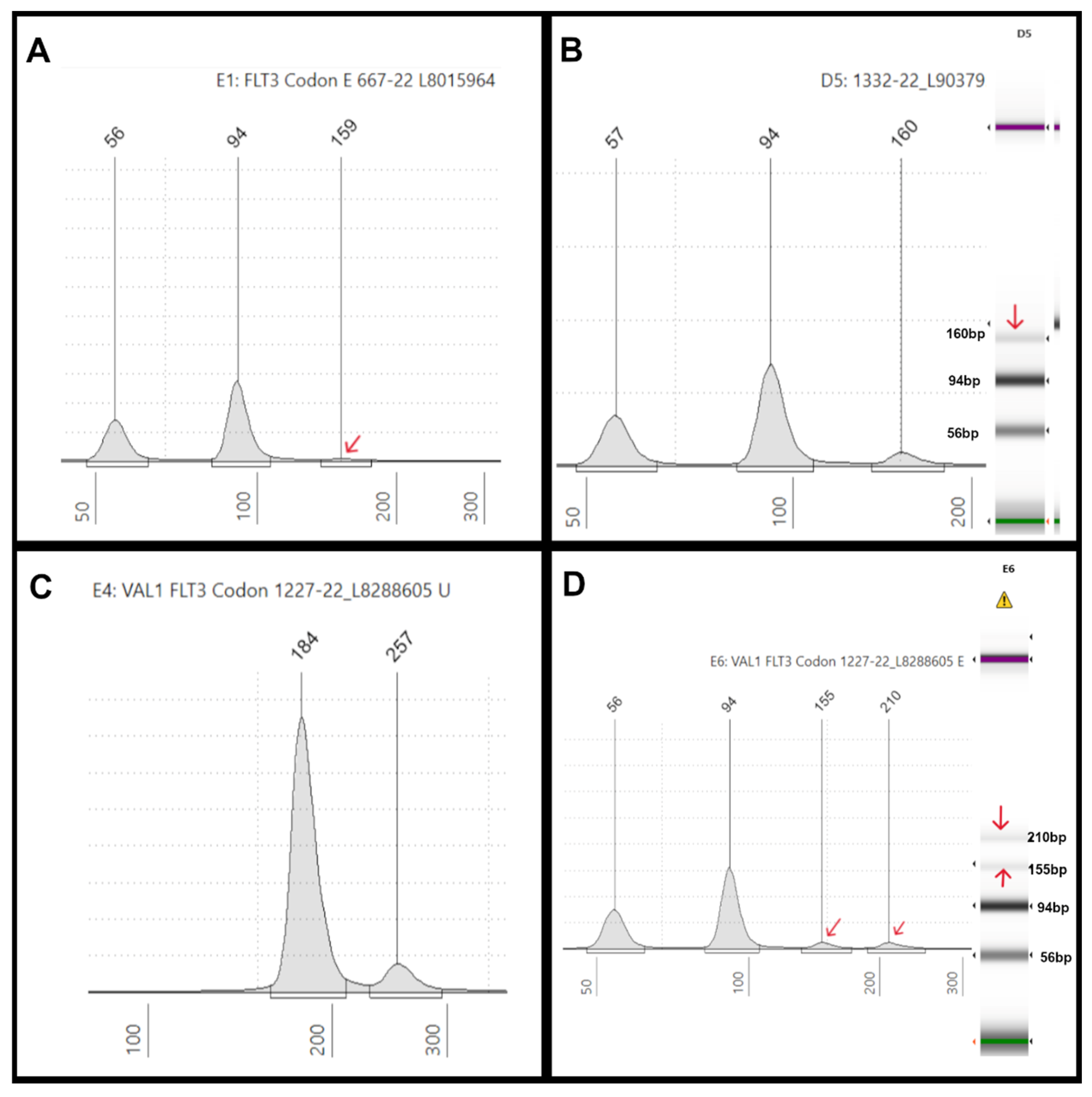

Figure 5.

TKD mutation illustrations: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of EcoRV digested sample #667-22 displaying three peaks at 56bp and 94bp (germline peaks), and 159bp (mutant peak indicated by the red arrow), which showed a FLT3-D835E mutation with 2% VAF by NGS. (B) An EPG of EcoRV digested sample #1332-22 showing three peaks at 57bp and 94bp (germline peaks), and 160bp (mutant peak), which showed a FLT3-D835H mutation with 12% VAF by NGS. On the right, the corresponding gel image in lane D5 shows three bands at 57bp, 94bp, and 160bp (red arrow), respectively. (C) An EPG of undigested sample #1227-22 shows an extraneous high molecular weight peak at 257bp in addition to the 184bp peak. (D) Sample #1227-22 after EcoRV digestion shows peaks at 56bp, 94bp, and 155bp (red arrows) as expected, similar to the positive control, but also has an extraneous peak at 210bp (red arrow), which is also seen in the corresponding gel image on the right (lane E6) (red arrows).

Figure 5.

TKD mutation illustrations: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of EcoRV digested sample #667-22 displaying three peaks at 56bp and 94bp (germline peaks), and 159bp (mutant peak indicated by the red arrow), which showed a FLT3-D835E mutation with 2% VAF by NGS. (B) An EPG of EcoRV digested sample #1332-22 showing three peaks at 57bp and 94bp (germline peaks), and 160bp (mutant peak), which showed a FLT3-D835H mutation with 12% VAF by NGS. On the right, the corresponding gel image in lane D5 shows three bands at 57bp, 94bp, and 160bp (red arrow), respectively. (C) An EPG of undigested sample #1227-22 shows an extraneous high molecular weight peak at 257bp in addition to the 184bp peak. (D) Sample #1227-22 after EcoRV digestion shows peaks at 56bp, 94bp, and 155bp (red arrows) as expected, similar to the positive control, but also has an extraneous peak at 210bp (red arrow), which is also seen in the corresponding gel image on the right (lane E6) (red arrows).

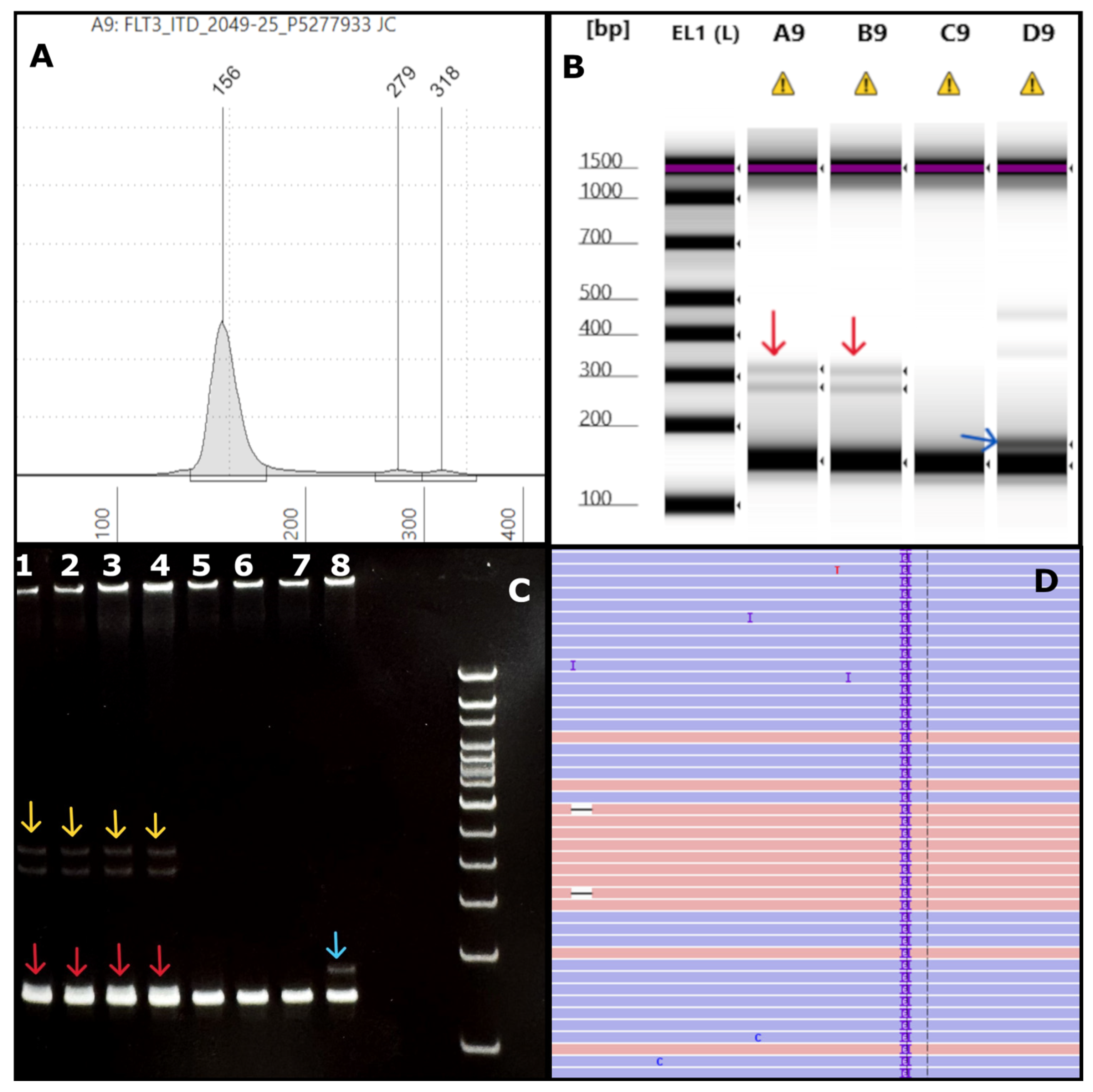

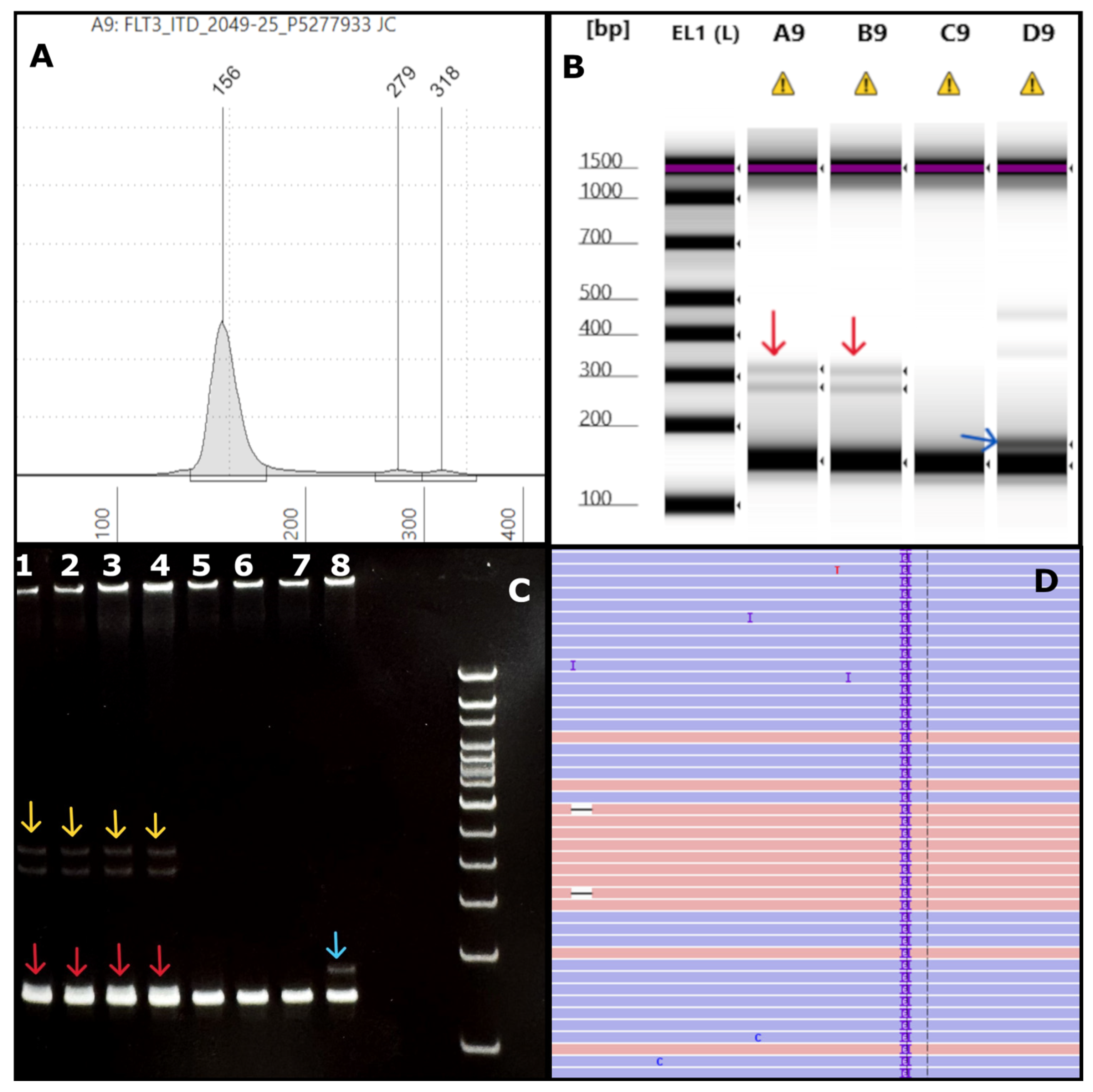

Figure 6.

AML case with very short insertion: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #2049-25 shows two ITDs of 123 bp and 162 bp in size (279 bp and 318 bp size markers). (B) The corresponding gel image in lanes A9 and B9 (sample run in duplicates) shows faint bands close to 300bp (red arrows) corresponding to the EPG peaks. Lanes D9 and C9 indicate positive (blue arrow) and negative controls, respectively. Note, the image is contrast enhanced for better visibility of the weak intensity large ITDs indicated by the red arrows. (C) The polyacrylamide gel electro-phoresis (PAGE) has the test sample run in duplicates in lanes 1-4, showing faint bands (yellow arrows) and a small insert (red arrows) slightly above the germline band. The other lanes denote positive (lane 8, blue arrow), negative controls (lane 7), and a different test sample (lanes 5-6). (D) Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) image for sample #2049-25 shows only a 6bp ITD at a VAF of 13%. By NGS, the 123bp and the 162bp ITDs were not found at all in IGV (0%) and were not detected by the Genexus OMAv2 software.

Figure 6.

AML case with very short insertion: (A) An electropherogram (EPG) of sample #2049-25 shows two ITDs of 123 bp and 162 bp in size (279 bp and 318 bp size markers). (B) The corresponding gel image in lanes A9 and B9 (sample run in duplicates) shows faint bands close to 300bp (red arrows) corresponding to the EPG peaks. Lanes D9 and C9 indicate positive (blue arrow) and negative controls, respectively. Note, the image is contrast enhanced for better visibility of the weak intensity large ITDs indicated by the red arrows. (C) The polyacrylamide gel electro-phoresis (PAGE) has the test sample run in duplicates in lanes 1-4, showing faint bands (yellow arrows) and a small insert (red arrows) slightly above the germline band. The other lanes denote positive (lane 8, blue arrow), negative controls (lane 7), and a different test sample (lanes 5-6). (D) Integrated Genome Viewer (IGV) image for sample #2049-25 shows only a 6bp ITD at a VAF of 13%. By NGS, the 123bp and the 162bp ITDs were not found at all in IGV (0%) and were not detected by the Genexus OMAv2 software.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in the assay.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used in the assay.

| Primer name |

Primer sequence |

Position on sequence in Accession AL445262.7 |

| FLT3-11F |

GCAATTTAGGTATGAAAGCCAGC |

17469 - 17447 |

| FLT3-11R |

CCAAACTCTAAATTTTCTCTTGGAAAC |

17335 - 17361 |

| FLT3-AF |

GCTTGTCACCCACGGGAAAG |

1811 - 1792 |

| FLT3-AD |

AGTGAGTGCAGTTGTTTACCATGATATC |

1642 - 1669 |