Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Rationale

- Do opinion leaders still play a central role in mediating media effects?

- How have digital affordances, such as algorithmic gatekeeping and platform architectures, restructured information flows?

- What adaptations or alternative models are necessary to understand influence in the digital age?

1.2. Objectives and Structure

- Synthesize empirical research from 2005–2025 assessing the TSF theory in digital environments.

- Analyze the changing nature of opinion leadership and the structure of influence in digital media.

- Examine the application and testing of TSF in specific domains: politics, health, marketing, and misinformation.

- Critically evaluate the limitations of TSF and review complementary or alternative models.

- Provide a nuanced discussion and recommendations for future research.

2. The Original Two-Step Flow Theory and Early Critiques

2.1. Foundations of TSF

2.2. Early Critiques of TSF

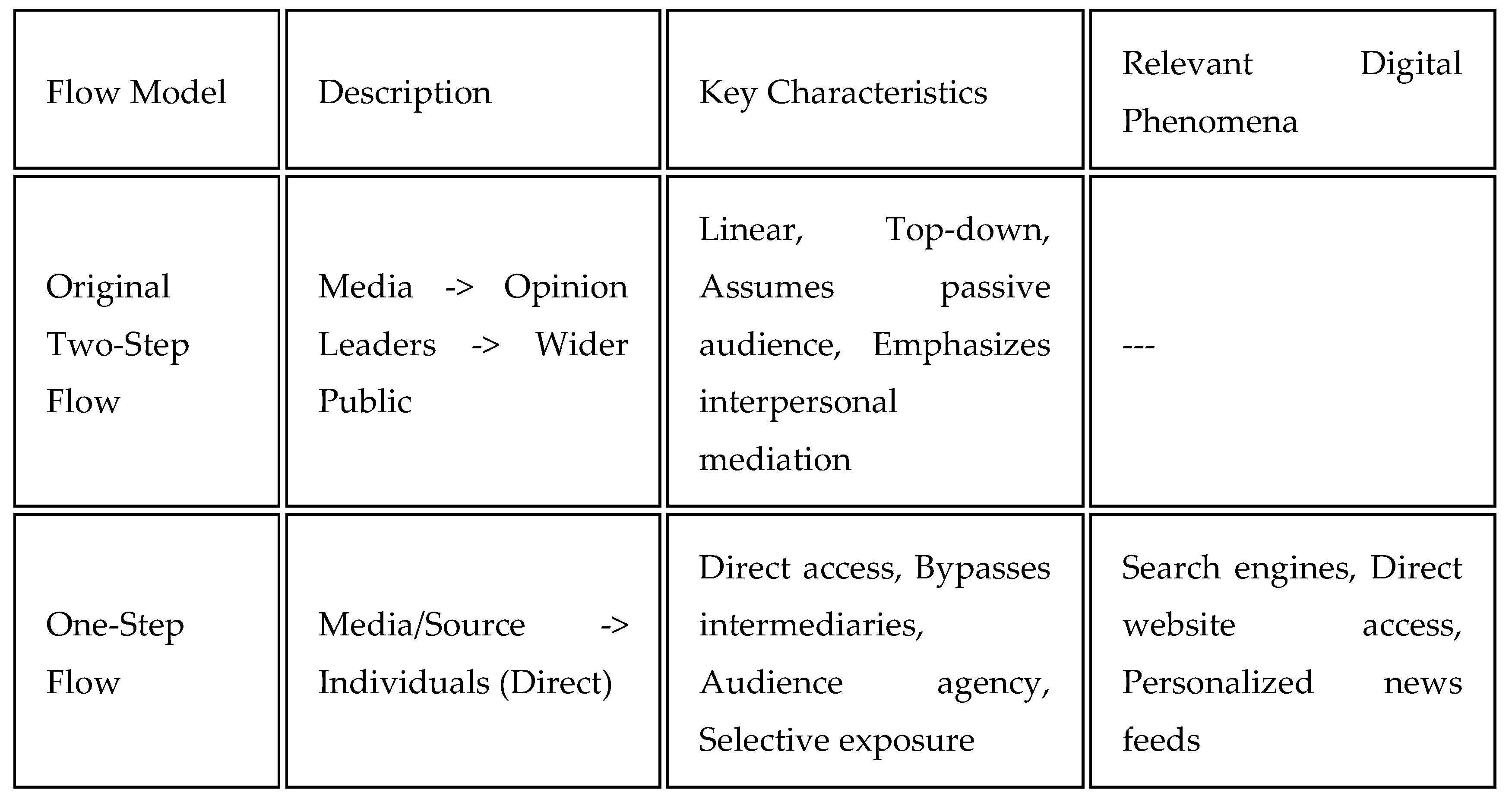

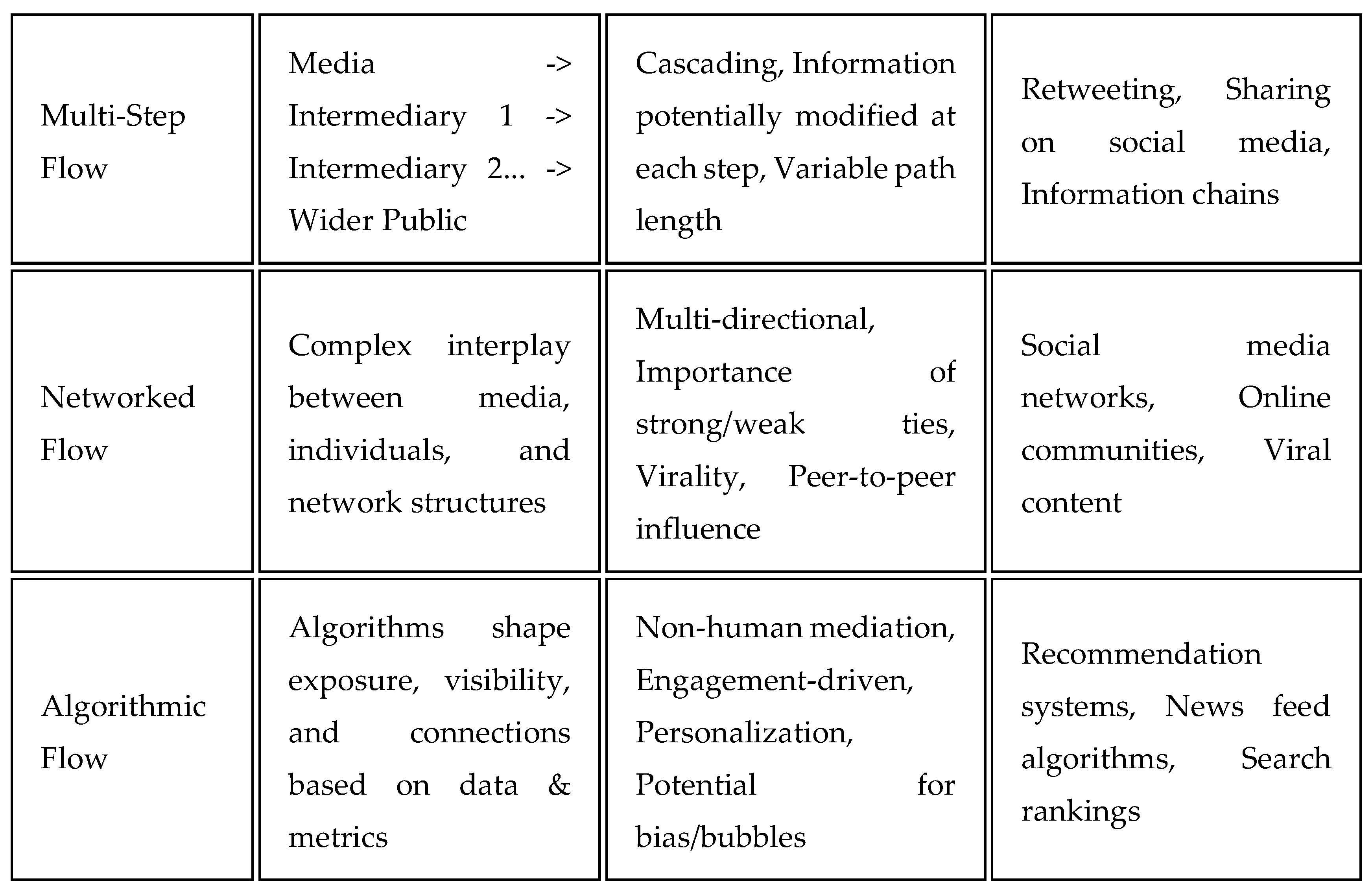

- Oversimplification: Critics argued that communication flows are more complex than a simple two-step process, often involving multi-step, one-step, or networked flows (Robinson, 1976; Troldahl, 1966; Van den Ban, 1964).

- Fluidity of Opinion Leadership: The leader-follower dichotomy was seen as artificial and context-dependent; individuals could be leaders in one domain and followers in another (Lin, 1971).

- Underestimation of Direct Media Effects: The model was critiqued for downplaying the direct effects of media, especially in agenda-setting and awareness (McCombs & Shaw, 1972).

- Active Audiences: The portrayal of opinion followers as passive recipients was challenged by research emphasizing audience agency and independent interpretation (Bauer, 1964).

3. The Two-Step Flow Theory in the Digital Media Ecosystem

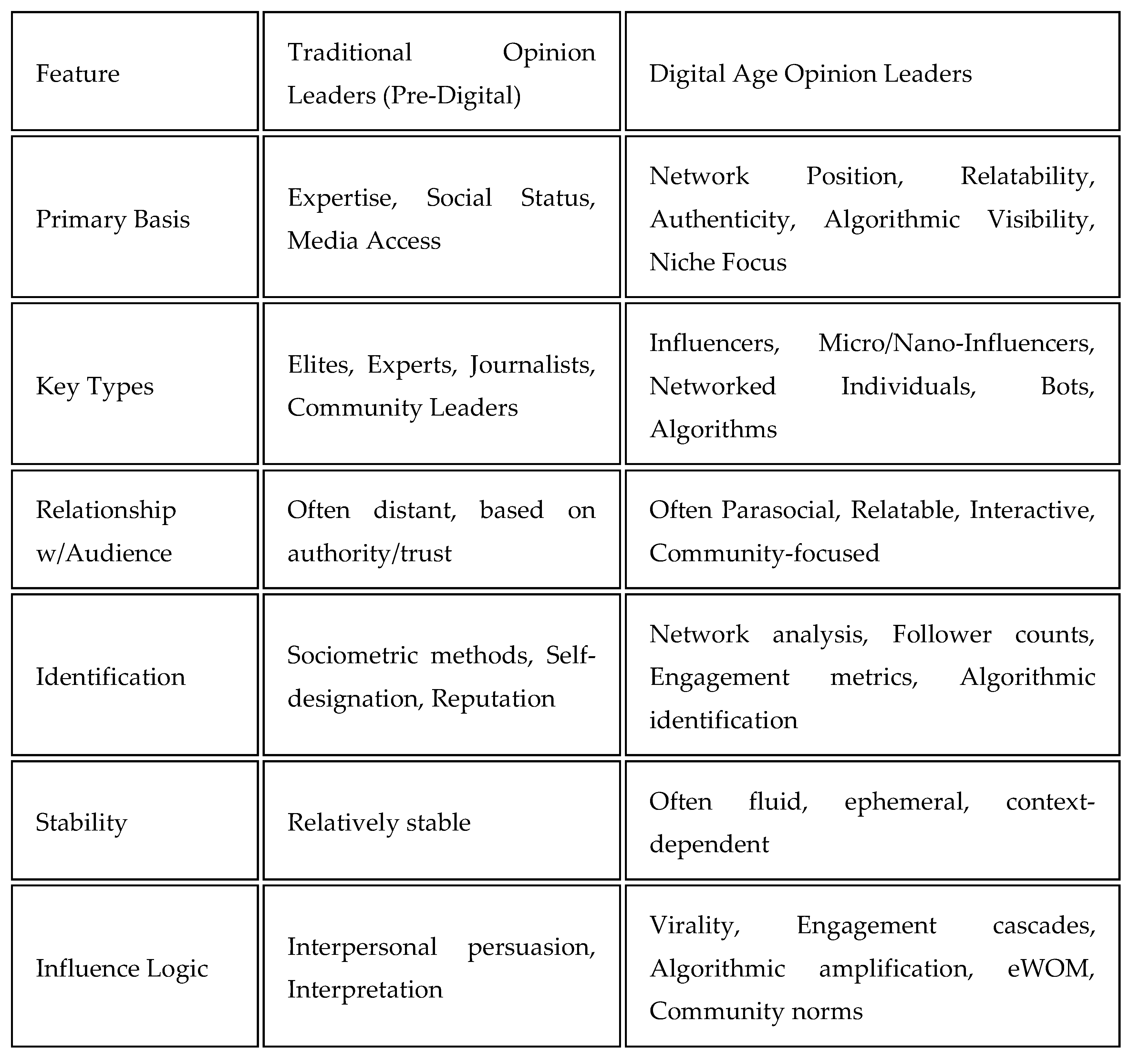

3.1. The Evolution of Opinion Leadership

|

3.1.1. Traditional Opinion Leaders in Digital Spaces

3.1.2. The Rise of Digital Influencers

3.1.3. Networked and Algorithmic Leadership

3.2. Transformation of Influence Pathways

|

|

3.2.1. Multi-Step and Networked Flows

3.2.2. One-Step and Direct Flows

3.2.3. Networked Flow and the Strength of Weak Ties

3.2.4. Echo Chambers and Filter Bubbles

3.3. Platform Architecture and Affordances

- Visibility and Social Metrics: Likes, shares, and follower counts provide visible social cues, amplifying perceived influence (Haim et al., 2018; van Dijck, 2013).

- Sharing Mechanisms: Features like retweets and shares accelerate diffusion and facilitate viral cascades (Guille et al., 2013; Kwak et al., 2010).

- Algorithmic Gatekeeping: Algorithms prioritize content based on engagement and user history, often amplifying certain voices while marginalizing others (Cotter et al., 2022).

- Context Collapse: Blurring of social contexts means messages intended for one group may reach unintended audiences, complicating targeted influence (Marwick & boyd, 2011).

4. Application and Testing of TSF in Digital Contexts

|

|

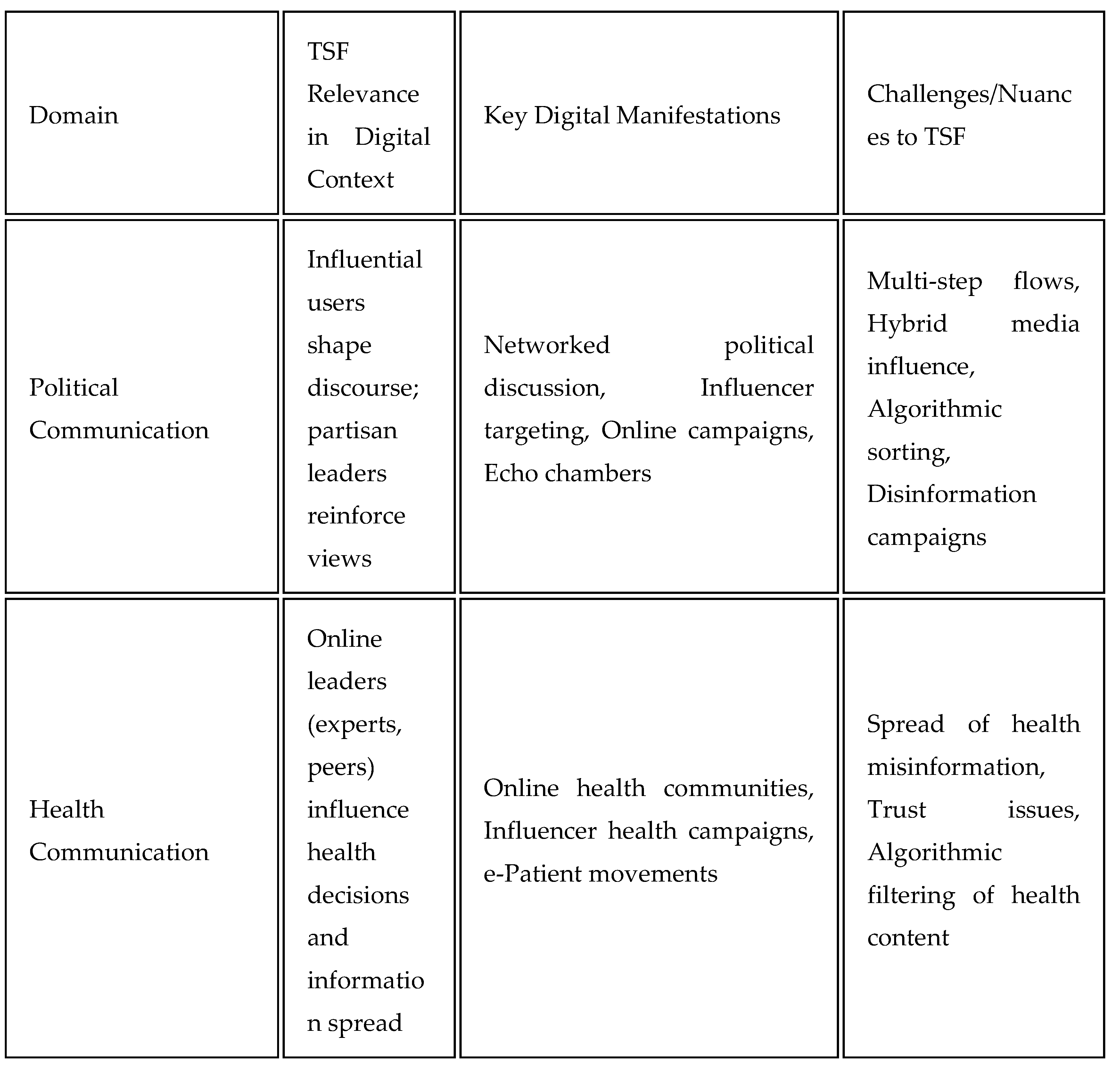

4.1. Political Communication

4.2. Health Communication

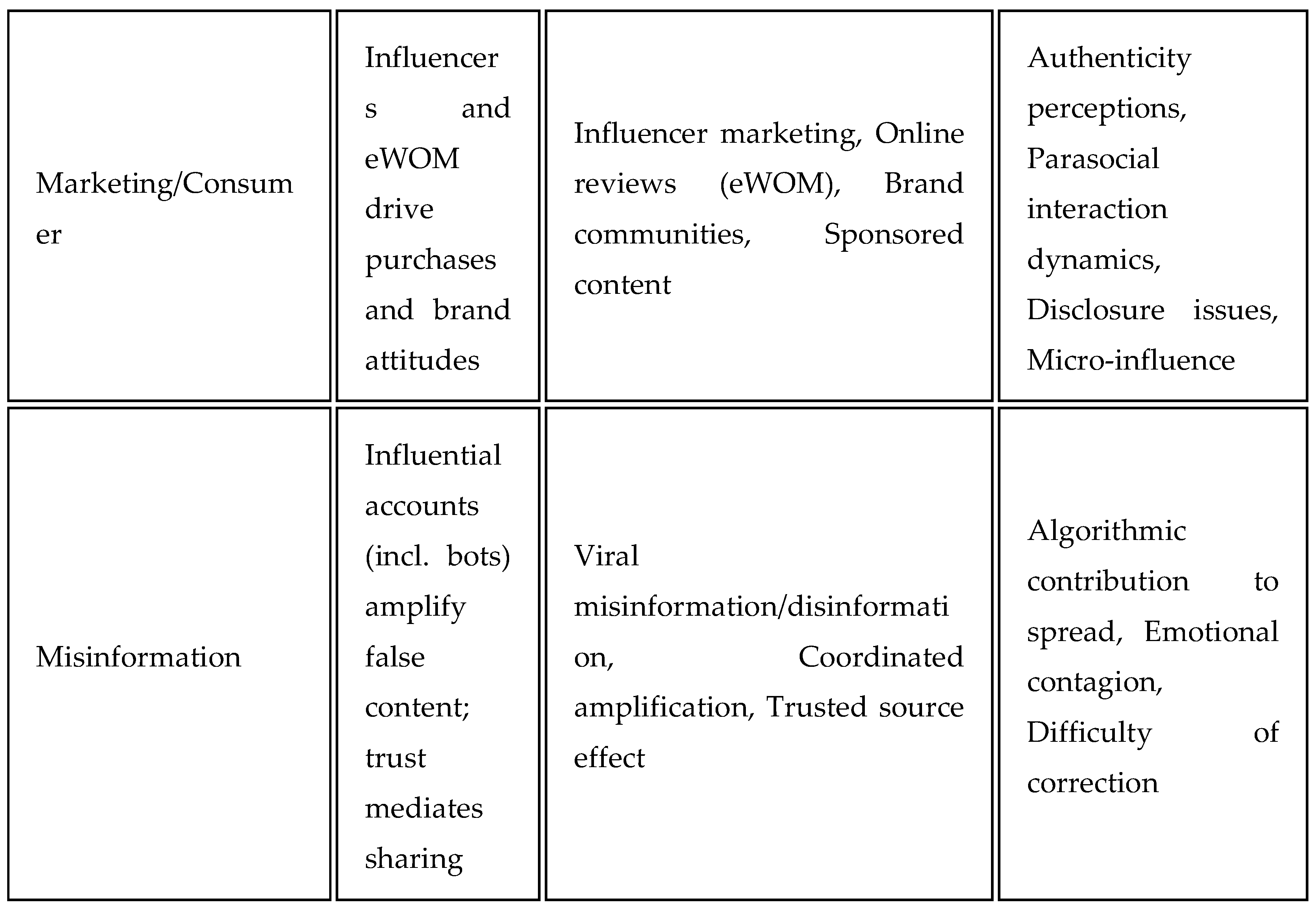

4.3. Marketing and Consumer Behavior

4.4. Misinformation and Disinformation

5. Critiques, Limitations, and Alternative Models

5.1. Critiques and Limitations of TSF in the Digital Age

- Oversimplification: The linear, two-step model is inadequate for describing multi-directional, networked, and algorithmically mediated information flows (Bennett & Segerberg, 2012; Castells, 2009).

- Fluid and Ephemeral Leadership: Online opinion leadership is highly contextual, transient, and often driven by algorithmic visibility rather than inherent expertise (boyd, 2010; Turcotte et al., 2015).

- Active Audiences and Direct Media Effects: Digital audiences actively seek, interpret, remix, and produce content, challenging the notion of passive followers and mediated influence (Jenkins, 2006; Livingstone, 2004).

- Algorithmic Mediation: TSF does not account for the powerful role of platform algorithms in shaping exposure, visibility, and influence (Bucher, 2017; Gillespie, 2014; Noble, 2018).

- Beyond Persuasion: Digital communication serves functions beyond persuasion, including community-building, identity expression, and deliberation, which are not addressed by TSF (Baym, 2010; Papacharissi, 2010).

- Online-Offline Nexus: Influence operates across digital and offline contexts, with complex feedback loops not captured by the original model (Couldry & Hepp, 2017; Wellman, 2001).

- Trust and Authenticity: The basis of trust in digital opinion leadership (parasocial relationships, algorithmic amplification) differs from face-to-face trust envisioned in TSF (Dubois et al., 2020; Marwick, 2015).

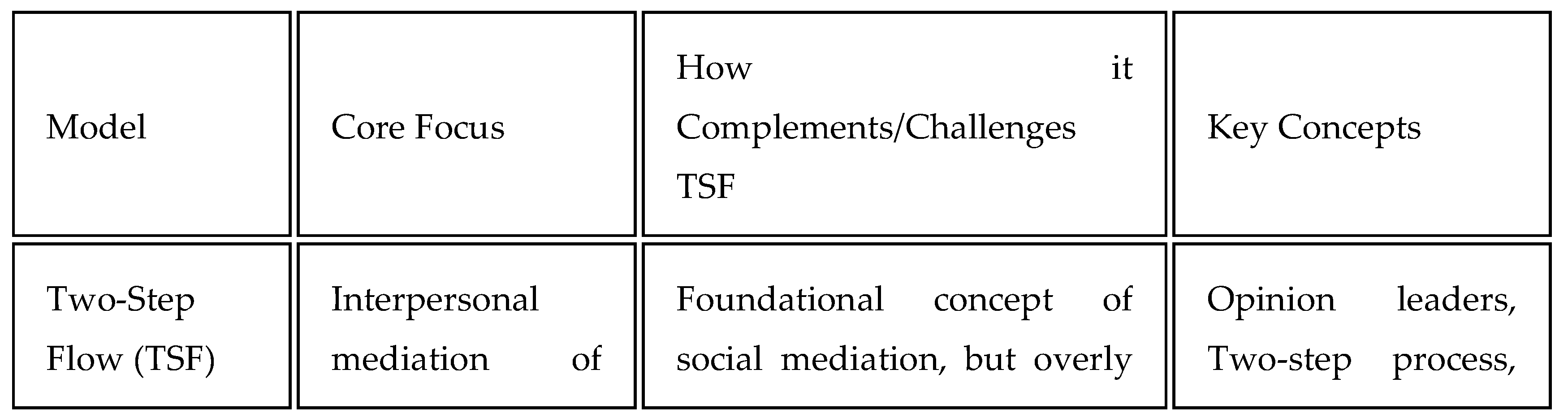

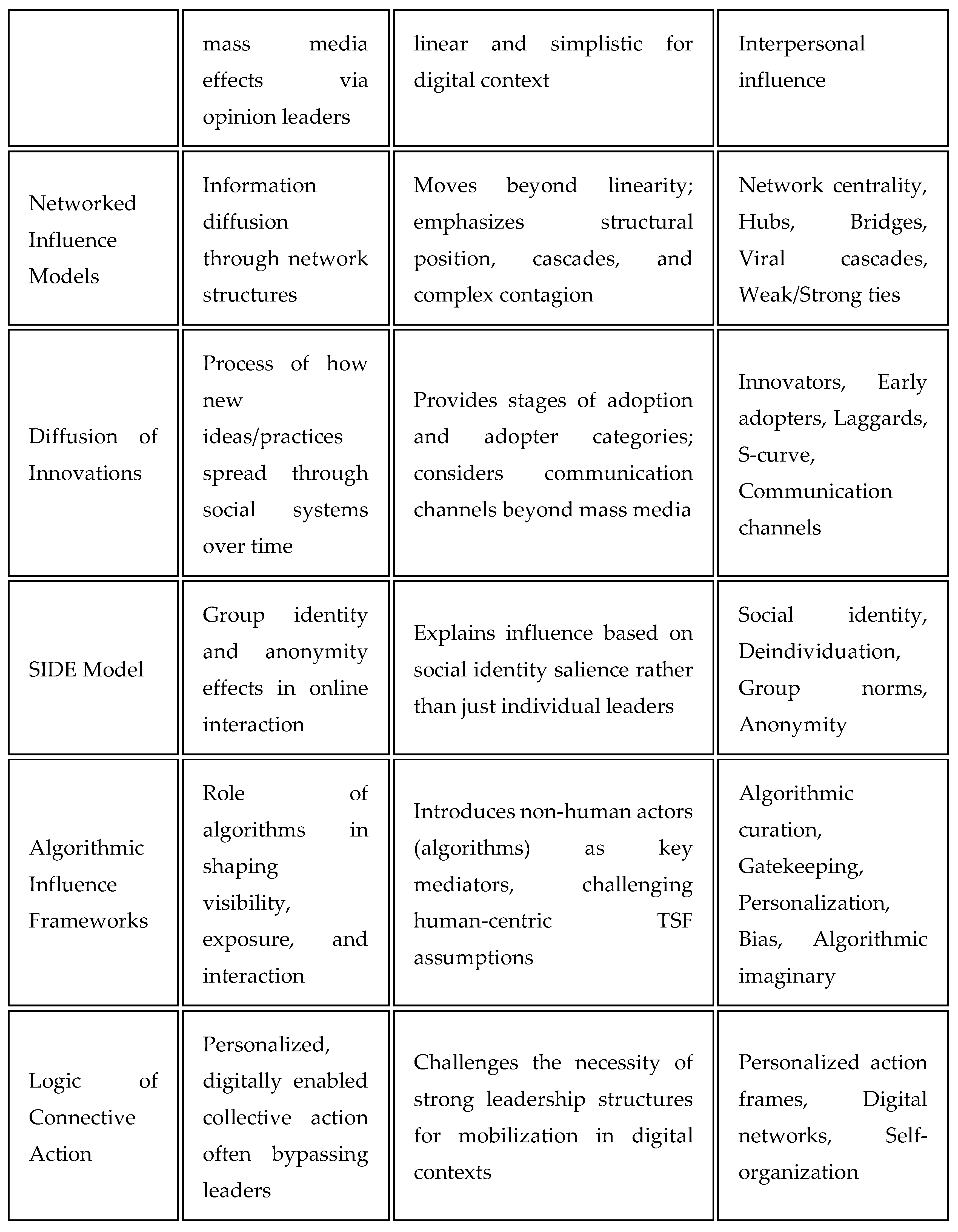

5.2. Alternative and Complementary Models

|

|

- Networked Influence Models: These models employ network science to analyze how structure and individual attributes interact to facilitate diffusion and cascades (Aral & Walker, 2012; Bakshy et al., 2012; Watts & Dodds, 2007).

- Diffusion of Innovations: Rogers’ (2003) diffusion model offers a process-oriented perspective, describing how innovations spread through social systems, involving multiple adopter categories and communication channels.

- Social Identity Model of Deindividuation Effects (SIDE): This framework explains how group identity and anonymity shape behavior and influence in digital environments (Postmes et al., 1998; Spears & Lea, 1994).

- Algorithmic Influence Frameworks: These models explore how algorithms mediate content exposure, confer visibility, and interact with social dynamics (Bucher, 2017; Cotter et al., 2022; Gillespie, 2014).

- Logic of Connective Action: Bennett and Segerberg (2012) propose that large-scale digital mobilization often bypasses traditional leaders via personalized, networked communication flows.

- Hybrid Models: Recent scholarship advocates for integrating TSF, network analysis, diffusion theory, and algorithmic studies to capture the interplay of social, structural, and technological factors (Hilbert et al., 2017; Weeks et al., 2017).

6. Synthesis and Future Research Directions

6.1. Synthesis of Findings

- Fragmentation and diversification of opinion leadership.

- Complex, multi-step, and networked information flows.

- Centrality of platform affordances and algorithmic gatekeeping.

- Contextual variation across issues, platforms, and cultural settings.

- The need for hybrid, integrative models that reflect the interplay of human, social, and technological factors.

6.2. Future Research Directions

- Integrated Models: Develop robust models integrating human agency, network structure, platform architecture, and content characteristics (Hilbert et al., 2017).

- Algorithmic Mediation: Investigate the role of algorithms as mediators, including their effects on opinion leadership, trust, and public perception (Bucher, 2017; Noble, 2018; Yeo et al., 2021).

- Cross-Platform Dynamics: Analyze how influence flows across multiple platforms and how platform ecosystems collectively shape public discourse (Chadwick et al., 2021).

- Longitudinal Analysis: Conduct longitudinal studies to understand the evolution of influence networks and the dynamics of opinion leadership over time (Aral & Dhillon, 2018).

- Online-Offline Interactions: Further explore the interplay between online and offline influence, including the translation of digital authority to real-world impact (Couldry & Hepp, 2017; Vaccari & Valeriani, 2016).

- Nuanced Leadership Typologies: Examine the diversity, motivations, and mechanisms of digital opinion leadership, moving beyond monolithic conceptions of "influencers" (Abidin, 2016; Dubois et al., 2020).

- Comparative and Global Research: Expand research beyond Western contexts to explore the applicability of TSF and related models globally (Valeriani & Vaccari, 2018).

- Influence in Malign Contexts: Investigate the role of human and algorithmic mediation in the spread of misinformation, hate speech, and polarization, developing targeted interventions (Benkler et al., 2018; Johnson et al., 2020).

7. Discussion

7.1. Enduring Relevance and Evolution of TSF

7.2. Limitations and Gaps

- The active role of audiences as content creators, remixers, and selective consumers (Bruns, 2008; Jenkins, 2006).

- The algorithmic mediation of visibility, reach, and influence (Bucher, 2017; Gillespie, 2014).

- The diversity of communication goals in digital environments, including community-building and identity work (Baym, 2010; Papacharissi, 2010).

- The interplay between online and offline influence.

- The ethical and societal implications of algorithmic and influencer-mediated communication.

7.3. Integrating TSF with Contemporary Models

8. Recommendations

- Adopt Hybrid Theoretical Frameworks: Combine TSF with network, diffusion, and algorithmic models to capture the complexity of digital influence.

- Prioritize Empirical Network Analysis: Employ network metrics and longitudinal data to empirically identify opinion leaders and influence pathways.

- Investigate Algorithmic Mediation: Critically examine how platform algorithms confer or diminish influence and shape public discourse.

- Embrace Cross-Platform and Cross-Cultural Research: Study influence diffusion across multiple platforms and diverse cultural settings.

- Examine Ethical Implications: Address the ethical challenges posed by algorithmic amplification, influencer marketing, and the spread of misinformation.

- Promote Digital and Algorithmic Literacy: Enhance public understanding of algorithmic curation to foster critical media consumption.

- Develop Interventions for Malign Influence: Design targeted interventions to mitigate the spread of misinformation, hate speech, and polarization.

- Foster Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Engage scholars from communication, sociology, computer science, psychology, and policy studies to develop integrative models.

9. Conclusion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Transparency

Competing Interests

References

- Abidin, C. (2016). Visibility labour: Engaging with influencers’ fashion brands and #OOTD advertorial campaigns on Instagram. Media International Australia, 161(1), 86–100. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R., & Prasad, J. (1998). A conceptual and operational definition of personal innovativeness in the domain of information technology. Information Systems Research, 9(2), 204–215. [CrossRef]

- An, J., Quercia, D., & Crowcroft, J. (2014). Partisan sharing: Facebook evidence and societal consequences. Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing (CSCW), 443-451. [CrossRef]

- Aral, S., & Dhillon, P. S. (2018). Digital influence and the diffusion of behavior. MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy Working Paper.

- Aral, S., & Walker, D. (2012). Identifying influential and susceptible individuals in networks. Science, 337(6092), 337–341. [CrossRef]

- Bakshy, E., Hofman, J. M., Mason, W. A., & Watts, D. J. (2011). Everyone's an influencer: Quantifying influence on twitter. Proceedings of the Fourth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), 65-74. [CrossRef]

- Bakshy, E., Messing, S., & Adamic, L. A. (2015). Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science, 348(6239), 1130–1132. [CrossRef]

- Bakshy, E., Rosenn, I., Marlow, C., & Adamic, L. A. (2012). The role of social networks in information diffusion. Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), 519-528. [CrossRef]

- Barberá, P., Jost, J. T., Nagler, J., Tucker, J. A., & Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right: Is online political communication more than an echo chamber? Psychological Science, 26(10), 1531–1542. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. A. (1964). The obstinate audience: The influence process from the point of view of social communication. American Psychologist, 19(5), 319–328. [CrossRef]

- Baym, N. K. (2010). Personal connections in the digital age. Polity Press.

- Benkler, Y., Faris, R., & Roberts, H. (2018). Network propaganda: Manipulation, disinformation, and radicalization in American politics. Oxford University Press.

- Bennett, W. L., & Manheim, J. B. (2006). The one-step flow of communication. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 608(1), 213–232. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768. [CrossRef]

- Bimber, B., & Davis, R. (2003). Campaigning online: The internet in U.S. elections. Oxford University Press.

- Boulianne, S. (2015). Social media use and participation: A meta-analysis of current research. Information, Communication & Society, 18(5), 524–538. [CrossRef]

- boyd, d. (2010). Social network sites as networked publics: Affordances, dynamics, and implications. In Z. Papacharissi (Ed.), A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites (pp. 39–58). Routledge.

- Bruns, A. (2008). Blogs, Wikipedia, Second Life, and beyond: From production to produsage. Peter Lang.

- Bruns, A., & Burgess, J. E. (2011). The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. Proceedings of the 6th European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) General Conference.

- Bucher, T. (2017). The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Information, Communication & Society, 20(1), 30–44. [CrossRef]

- Burki, T. K. (2019). Vaccine misinformation and social media. The Lancet Digital Health, 1(6), e258–e259. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2010). Determinants of the success of corporate blogs as a channel to build customer relationships. Management Decision, 48(6), 904–928. [CrossRef]

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519. [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. (2009). Communication power. Oxford University Press.

- Centola, D., & Macy, M. (2007). Complex contagion and the weakness of long ties. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3), 702–734. [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A., Dennis, J., & Smith, A. P. (2021). Politics in the pandemic: Platforms, civic spaces and emerging modes of political participation. Political Studies Association.

- Chen, J., Wang, Y., & Wang, X. (2018). Understanding the mechanisms of online health communities: A study of social support and online health opinion leaders. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(4), 764. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C. M., & Thadani, D. R. (2012). The impact of electronic word-of-mouth communication: A literature analysis and integrative model. Decision Support Systems, 54(1), 461–470. [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. (2015). The two-step flow of communication in the digital age: Assessing the roles of opinion leaders and web sites in the flow of political information. American Politics Research, 43(3), 438–466. [CrossRef]

- Conway, B. A., Kenski, K., & Wang, D. (2015). The rise of Twitter in the political campaign: Searching for intermedia agenda-setting effects in the presidential primary. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(4), 363–380. [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K., Cho, A., & Rader, E. (2022). Algorithmic mediation of collective action on social media. New Media & Society. [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N., & Hepp, A. (2017). The mediated construction of reality. Polity Press.

- De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. [CrossRef]

- Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), 554–559. [CrossRef]

- Di Gennaro, C., & Dutton, W. H. (2006). The internet and the public: Online and offline political participation in the United Kingdom. Parliamentary Affairs, 59(2), 299–313. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, E., Gruzd, A., & Jacobson, J. (2020). Journalists’ reliance on social media for newsgathering: A comparative study of Canadian and American practices. Digital Journalism, 8(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17(2), 138–149. [CrossRef]

- Eysenbach, G., Powell, J., Englesakis, M., Rizo, C., & Stern, A. (2004). Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: Systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ, 328(7449), 1166. [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, S., Goel, S., & Rao, J. M. (2016). Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly, 80(S1), 298–320. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, R. K., & Cantijoch, M. (2013). Conceptualizing and measuring participation in the digital age: The case of Britain. The British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 15(4), 529–548. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society (pp. 167–193). MIT Press.

- Goel, S., Watts, D. J., & Goldstein, D. G. (2012). The structure of online diffusion networks. Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce (EC), 623-638. [CrossRef]

- Gökalp, E., Eren, P. E., & Eren, M. Ş. (2022). Micro versus macro influencers on Instagram: The role of perceived authenticity and homophily. European Journal of Marketing, 56(13), 174–199. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Bailon, S., Borge-Holthoefer, J., & Moreno, Y. (2011). Broadcasters and hidden influentials in online protest diffusion. American Behavioral Scientist, 55(10), 1247–1266. [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V. A., Armour, K. M., & Wood, H. (2018). Young people learning about health: The role of online sources and digitally mediated communication. Media Education Research Journal, 26(2), 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B., & Lazer, D. (2019). Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science, 363(6425), 374–378. [CrossRef]

- Guille, A., Hacid, H., Favre, C., & Zighed, D. A. (2013). Information diffusion in online social networks: A survey. ACM SIGMOD Record, 42(2), 17–28. [CrossRef]

- Haim, M., Graefe, A., & Brosius, H.-B. (2018). Burst of the filter bubble? Effects of personalization on the diversity of online news. Digital Journalism, 6(3), 330–346. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D. L., Shneiderman, B., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Analyzing social media networks with NodeXL: Insights from a connected world. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Heldman, A. B., Schindelar, J., & Weaver, J. B., III. (2013). Social media engagement and public health communication: Implications for public health organizations being truly “social”. Public Health Reviews, 35(1), 13. [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., Walsh, G., & Gremler, D. D. (2004). Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 18(1), 38–52. [CrossRef]

- Hesse, B. W., Nelson, D. E., Kreps, G. L., Croyle, R. T., Arora, N. K., Rimer, B. K., & Viswanath, K. (2005). Trust and sources of health information: The impact of the Internet and its implications for health communication. Archives of Internal Medicine, 165(22), 2618–2624. [CrossRef]

- Hilbert, M., Vásquez, J., Halpern, D., Valenzuela, S., & Arriagada, E. (2017). One step, two step, network step? Complementary perspectives on communication flows in Twittered citizen protests. Social Science Computer Review, 35(4), 444–461. [CrossRef]

- Himelboim, I. (2011). Civil society and online political discourse: The network structure of unrestricted discussions. Communication Research, 38(5), 634–659. [CrossRef]

- Himelboim, I., McCreery, S., & Smith, M. (2012). Birds of a feather tweet together: Integrating network and content analyses to examine cross-ideology exposure on Twitter. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(2), 40–60. [CrossRef]

- Ho, S. S., Lwin, M. O., Lee, E. W. J., & Shin, W. (2021). Examining the effects of social media opinion leaders in evoking positive emotions and support for environmental causes among youths: The case of #SaveLeuserEcosystem. Journal of Communication, 71(1), 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., Swaminathan, V., & Brooks, G. (2019). Driving brand engagement through online social influencers: An empirical investigation of sponsored blogging campaigns. Journal of Marketing, 83(5), 78–96. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K. O., Ottenbacher, A. J., Green, A. P., Cannon-Diehl, M. R., Richardson, O., Bernstam, E. V., & Thomas, E. J. (2010). Social support in an Internet weight loss community. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 79(1), 5–13. [CrossRef]

- Iyengar, S., & Hahn, K. S. (2009). Red media, blue media: Evidence of ideological selectivity in media use. Journal of Communication, 59(1), 19–39. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York University Press.

- Jin, S. V., Muqaddam, A., & Ryu, E. (2019). Instafamous and social media influencer marketing. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(5), 567–579. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. F., Velásquez, N., Restrepo, N. J., Leahy, R., Gabriel, N., El Oud, S., Zheng, M., Manrique, P., Wuchty, S., & Lupu, Y. (2020). The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views. Nature, 582(7811), 230–233. [CrossRef]

- Kata, A. (2010). A postmodern Pandora's box: Anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet. Vaccine, 28(7), 1709–1716. [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. (1957). The two-step flow of communication: An up-to-date report on an hypothesis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 61–78. [CrossRef]

- Katz, E., & Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1955). Personal influence: The part played by people in the flow of mass communications. Free Press.

- Khamis, S., Ang, L., & Welling, R. (2017). Self-branding, ‘micro-celebrity’ and the rise of Social Media Influencers. Celebrity Studies, 8(2), 191–208. [CrossRef]

- Kite, J., Foley, B. C., Grunseit, A. C., & Freeman, B. (2016). Please like me: Insights into social media use by Australian health promotion agencies to disseminate campaigns. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 40(5), 468–474. [CrossRef]

- Kwak, H., Lee, C., Park, H., & Moon, S. (2010). What is Twitter, a social network or a news media? Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), 591-600. [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M., Habibi, M. R., Richard, M.-O., & Sankaranarayanan, R. (2012). The effects of social media based brand communities on brand community markers, value creation practices, brand trust and brand loyalty. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1755–1767. [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1944). The people's choice: How the voter makes up his mind in a presidential campaign. Duell, Sloan and Pearce.

- Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., Metzger, M. J., Nyhan, B., Pennycook, G., Rothschild, D., Schudson, M., Sloman, S. A., Sunstein, C. R., Thorson, E. A., Watts, D. J., & Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. E., & Watkins, B. (2016). YouTube vloggers’ influence on consumer luxury brand perceptions and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5753–5760. [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. (1971). The study of human communication. Bobbs-Merrill.

- Livingstone, S. (2004). Media literacy and the challenge of new information and communication technologies. The Communication Review, 7(1), 3–14. [CrossRef]

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A. E. (2015). Instafame: Luxury selfies in the attention economy. Public Culture, 27(1 75), 137–160. [CrossRef]

- Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. [CrossRef]

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. [CrossRef]

- Meraz, S. (2009). Is there an elite hold? Traditional media to social media agenda setting influence in blog networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 14(3), 682–707. [CrossRef]

- Messing, S., & Westwood, S. J. (2014). Selective exposure in the age of social media: Endorsements trump partisan source affiliation when selecting news online. Communication Research, 41(8), 1042–1063. [CrossRef]

- Napoli, P. M. (2014). On the central role of concentration in the communications policy discourse. International Journal of Communication, 8, 2850–2871.

- Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. NYU Press.

- Paek, H.-J., Kim, K., & Hove, T. (2010). Content analysis of antismoking videos on YouTube: Message sensation value, message appeals, and their relationships with viewer responses. Health Education & Behavior, 37(2), 208–229. [CrossRef]

- Papacharissi, Z. (Ed.). (2010). A networked self: Identity, community, and culture on social network sites. Routledge.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the internet is hiding from you. Penguin UK.

- Park, D.-H., Lee, J., & Han, I. (2007). The effect of on-line consumer reviews on consumer purchasing intention: The moderating role of involvement. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 11(4), 125–148. [CrossRef]

- Parmelee, J. H. (2014). The agenda-building function of political tweets. New Media & Society, 16(3), 434–450. [CrossRef]

- Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Lea, M. (1998). Breaching or building social boundaries? SIDE-effects of computer-mediated communication. Communication Research, 25(6), 689–715. [CrossRef]

- Quattrociocchi, W., Scala, A., & Sunstein, C. R. (2016). Echo chambers on Facebook. SSRN Electronic Journal. [CrossRef]

- Rainie, L., & Wellman, B. (2012). Networked: The new social operating system. MIT Press.

- Robinson, J. P. (1976). Interpersonal influence in election campaigns: Two step-flow hypotheses. Public Opinion Quarterly, 40(3), 304–319. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

- Schouten, A. P., Janssen, L., & Verspaget, M. (2020). Celebrity vs. influencer endorsements in advertising: The role of identification, credibility, and product-endorser fit. International Journal of Advertising, 39(2), 258–281. [CrossRef]

- Shao, C., Ciampaglia, G. L., Varol, O., Yang, K.-C., Flammini, A., & Menczer, F. (2018). The spread of low-credibility content by social bots. Nature Communications, 9(1), 4787. [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K., & Kefi, H. (2020). Instagram and YouTube bloggers promote it, why should I buy? How credibility and parasocial interaction influence purchase intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 53, 101742. [CrossRef]

- Spears, R., & Lea, M. (1994). Panacea or panopticon? The hidden power in computer-mediated communication. Communication Research, 21(4), 427–459. [CrossRef]

- Starbird, K., Maddock, J., Orand, M., Achterman, P., & Mason, R. M. (2014). Rumors, false flags, and digital vigilantes: Misinformation on Twitter after the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing. Proceedings of the iConference 2014, 654-662. [CrossRef]

- Starbird, K., Arif, A., & Wilson, T. (2019). Disinformation as collaborative work: Surfacing the participatory nature of strategic information operations. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3(CSCW), Article 127. [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2017). #Republic: Divided democracy in the age of social media. Princeton University Press.

- Thackeray, R., Neiger, B. L., Smith, A. K., & Van Wagenen, S. B. (2012). Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health, 12(1), 242. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S. T., Van Der Heide, B., Langwell, L., & Walther, J. B. (2008). Too much of a good thing? The relationship between number of friends and interpersonal impressions on Facebook. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(3), 531–549. [CrossRef]

- Troldahl, V. C. (1966). A field test of a modified "two-step flow of communication" model. Public Opinion Quarterly, 30(4), 609–623. [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J. A., Guess, A., Barberá, P., Vaccari, C., Siegel, A., Sanovich, S., Stukal, D., & Nyhan, B. (2018). Social media, political polarization, and political disinformation: A review of the scientific literature. Hewlett Foundation Working Paper.

- Turcotte, J., York, C., Irving, J., Scholl, R. M., & Pingree, R. J. (2015). News recommendations from social media opinion leaders: Effects on media trust and information seeking. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(5), 520–535. [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2015). Party campaigners or citizen campaigners? How social media use shapes campaign participation. Party Politics, 21(3), 421–431. [CrossRef]

- Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2016). Political conversations in online networks: Structural properties and determinants of discussion networks on social networking sites. Information, Communication & Society, 19(7), 931–949. [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, S., Halpern, D., & Katz, J. E. (2018). A network approach to the study of political participation and exposure to disagreement online. Social Science Computer Review, 36(2), 147–164. [CrossRef]

- Valeriani, A., & Vaccari, C. (2018). Political talk on mobile instant messaging services: A comparative analysis of six countries. Information, Communication & Society, 21(11), 1715–1731. [CrossRef]

- Van den Ban, A. W. (1964). A revision of the two-step flow of communications hypothesis. Gazette, 10(3), 237–250. [CrossRef]

- van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity: A critical history of social media. Oxford University Press.

- Vosoughi, S., Roy, D., & Aral, S. (2018). The spread of true and false news online. Science, 359(6380), 1146–1151. [CrossRef]

- Watts, D. J., & Dodds, P. S. (2007). Influentials, networks, and public opinion formation. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 441–458. [CrossRef]

- Weeks, B. E., Ardèvol-Abreu, A., & Gil de Zúñiga, H. (2017). Online influence? Social media use, opinion leadership, and political persuasion. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 29(2), 214–239. [CrossRef]

- Weimann, G. (1982). On the importance of marginality: One more step into the two-step flow of communication. American Sociological Review, 47(6), 764–773. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. (2001). Physical place and cyberplace: The rise of personalized networking. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 25(2), 227–252. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J., Lim, E.-P., Jiang, J., & He, Q. (2010). TwitterRank: Finding topic-sensitive influential twitterers. Proceedings of the Third ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Wright, K. B. (2016). Communication in health-related online social support groups/communities: A review of research on predictors of participation, applications of social support theory, and health outcomes. Review of Communication Research, 4, 65–87. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S. K., McKasy, M., & Cacciatore, M. A. (2021). Filtering out the noise: The role of trust, lay-expert gap, and algorithmic literacy in shaping public perceptions of algorithmic curation. Mass Communication and Society, 24(4), 483–506. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).