Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Models and Methods

2.1. Oxygen Diffusion Kinetics in Neural Tissue

2.1.1. The Krogh-Erlang Model and Neural Adaptations

- is the oxygen partial pressure ( mmHg ) at radial distance from the capillary

- is the radial coordinate ( )

- is the tissue oxygen consumption rate ( tissue )

- is the Krogh diffusion coefficient, defined as tissue )

- is the oxygen diffusivity in tissue

- is the oxygen solubility in tissue ( tissue )

- is the capillary oxygen partial pressure ( mmHg )

- is the capillary radius ( )

- is the tissue cylinder radius ( )

- tissue (for neurons)

- tissue

- tissue

2.1.2. Modified Krogh Model with Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

- is the oxygen partial pressure at which consumption is half of the maximum ( mmHg ), typically for neural tissue

- Other parameters are as defined above

2.1.3. Model with Axial Diffusion for Neural Tissue

- is the axial coordinate along the capillary ( )

- Other parameters are as defined above

2.2. Mitochondrial Energy Production Models

2.2.1. Bertram-Pedersen-Luciani-Sherman (BPLS) Model

- is the mitochondrial NADH concentration (mM)

- is the mitochondrial ADP concentration (mM)

- is the mitochondrial membrane potential (mV)

- is the mitochondrial calcium concentration ( uM )

- γ is a scaling factor to convert flux units (dimensionless)

- f_m is the fraction of free (unbound) Ca^(2+) in the mitochondria (dimensionless)

- C_"mito " is the mitochondrial capacitance ( μM/mV )

- Flux equations include:

- Pyruvate dehydrogenase flux:

- J_pdh=(J_pdh^max [Ca^(2+) ]_m/K_pdh )⋅FBP/(FBP+K_FBP )(18)

- Respiration/Oxidation rate:

- J_o=(p_1 [NADH]_m)/(p_2+[NADH]_m )⋅1/(1+exp((p_3-Ψ_m )/p_4 ) )(19)

- ATP synthase rate:

- J_F1F0=(p_5 [ADP]_m⋅exp((p_6-p_7⋅([ADP]_m)/([ATP]_m )) Ψ_m⋅FRT))/(p_8+[ADP]_m )(20)

- With algebraic relations:

- ■([NAD]_m=NAD_"tot " -[NADH]_m@[ATP]_m=A_tot-[ADP]_m@RAT_m=([ATP]_m)/([ADP]_m ))(21),(22),(23)

2.2.2. Thermodynamically-Consistent Model

- is the rate constant for ATP synthesis

- is the standard free energy of ATP synthesis

- is the number of protons transported per ATP synthesized (typically 3-4)

- is the proton electrochemical gradient ( )

- is the gas constant

- is the temperature (K)

- (basal, glutamate-stimulated, K⁺-stimulated)]

2.3. Evolutionary Trade-off Models

2.3.1. Resource Allocation Y-Model

- is the total available resource (e.g., energy)

- is the allocation to trait A

- is the allocation to trait B

- is the total energy derived from oxygen consumption

- is the energy invested in ATP production

- is the energy "lost" to reactive oxygen species generation

- is the energy allocated to signalling functions

2.3.2. Performance-Efficiency Trade-off Model

- is the total fitness or performance

- is the performance function dependent on ATP production

- is the efficiency function dependent on oxygen consumption

- and are relative weights of performance and efficiency

2.3.3. Metabolic Scaling and Developmental Timing Model

- is the time required for neuronal development

- is the metabolic rate (oxygen consumption rate)

- and are scaling parameters that differ between species

- For human neurons, is approximately 0.25 , consistent with the West-Brown-Enquist metabolic scaling theory.

2.4. Methods for Computational Implementation

- Ordinary Differential Equation (ODE) Solvers: For whole-cell or tissue-level simulations, standard ODE solvers (e.g., Runge-Kutta methods) can be used to solve the systems of equations.

- Finite Element Methods: For spatial models of oxygen diffusion in neural tissue with complex geometries.

- Agent-Based Modelling: For studies involving mitochondrial dynamics and spatial heterogeneity, particularly useful for studying evolutionary adaptations at the subcellular level.

- Monte Carlo Simulations: To capture stochastic effects in mitochondrial function and evolution.

3. Results

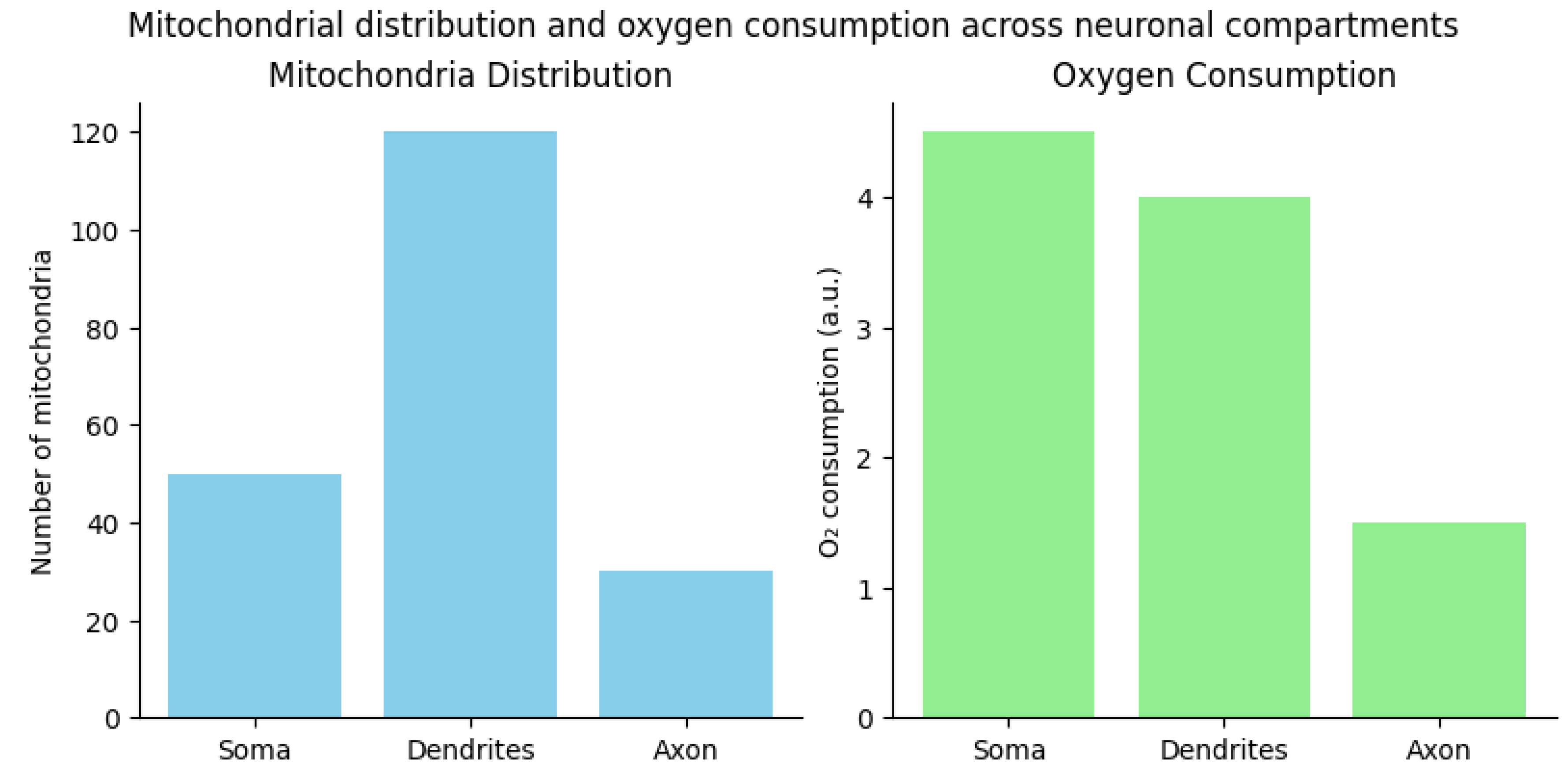

3.1. Mitochondrial Density and Distribution Data

| Compartment | Mitochondrial Density | Mobility | Oxygen Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soma | Highest (5-10 mitochondria/μm³) | Low | Moderate |

| Proximal dendrites | 3-5 mitochondria/μm³ | Moderate | High |

| Distal dendrites | 1-2 mitochondria/μm³ | High | Moderate |

| Axon initial segment | 0.5-1 mitochondria/μm³ | Low | Very high |

| Axon shaft | 0.1-0.5 mitochondria/μm³ | High | Low |

| Presynaptic terminals | 1-3 mitochondria/μm³ | Very low | Very high |

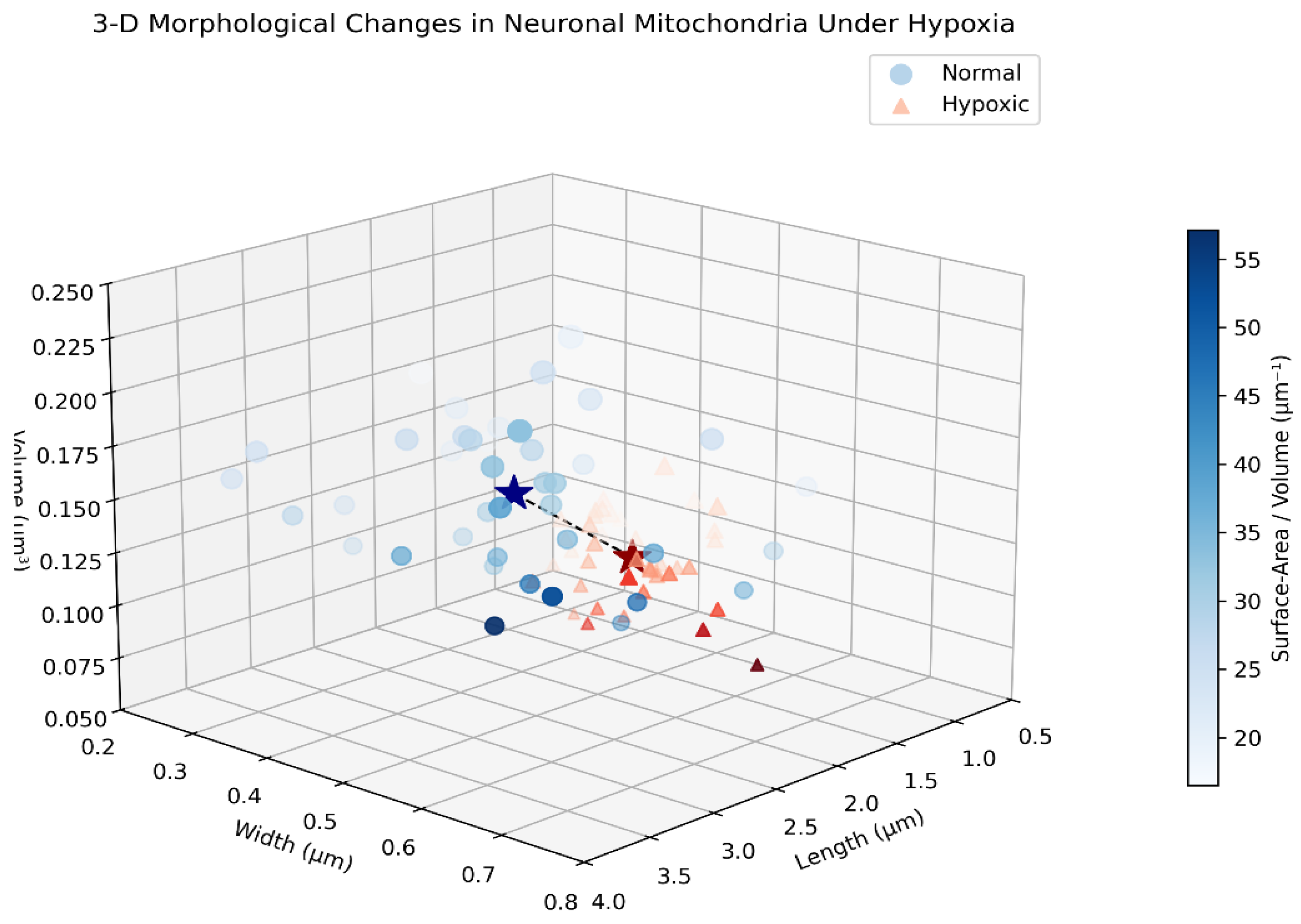

3.2. Mitochondrial Morphology Under Oxygen Constraints

| Parameter | Normal Condition | Hypoxic Condition | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average mitochondrial length | 2.8 μm | 1.2 μm | -57% |

| Fragmented mitochondria ratio | 15% | 65% | +333% |

| Mitochondrial surface area | 0.82 μm² | 0.54 μm² | -34% |

| Mitochondrial volume | 0.17 μm³ | 0.09 μm³ | -47% |

| Surface area/volume ratio | 4.82 μm⁻¹ | 6.00 μm⁻¹ | +24% |

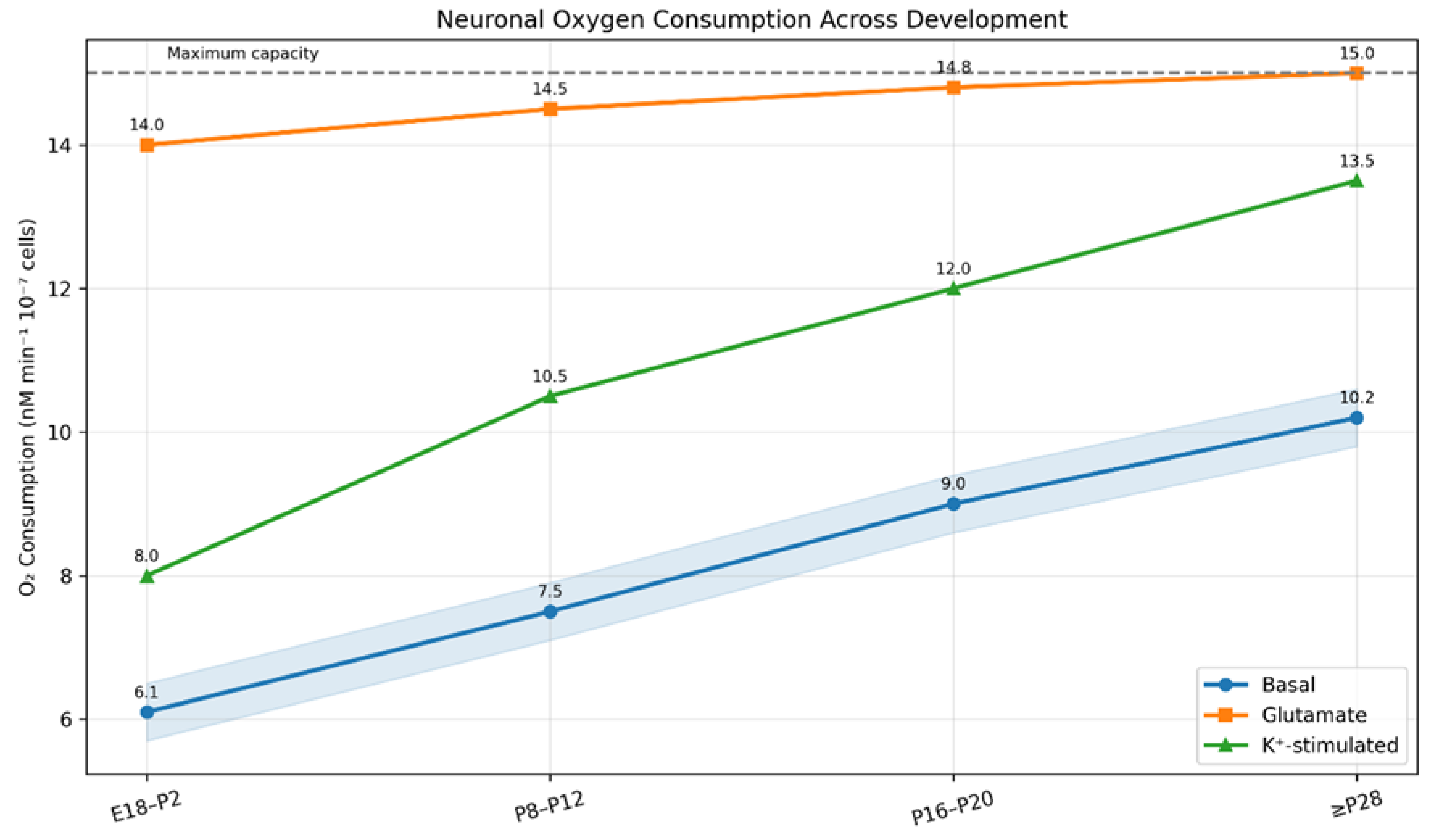

3.3. Mitochondrial Respiration Data

| Parameter | Value | Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Basal oxygen consumption | 6.1 nM/min/10⁷ cells | Immature neurons (E18-P2) |

| Basal oxygen consumption | 10.2 nM/min/10⁷ cells | Mature neurons (≥P28) |

| Glutamate-stimulated O₂ consumption | ≥14 nM/min/10⁷ cells | All age groups |

| Maximum oxygen consumption | 14-15 nM/min/10⁷ cells | Neurons ≥P8 |

| Oxygen consumption reduction | ~50% | After blocking spike discharge |

| Mitochondrial membrane potential | -139 mV | Resting cortical neurons |

| MMP regulation range | -108 to -158 mV | During activity |

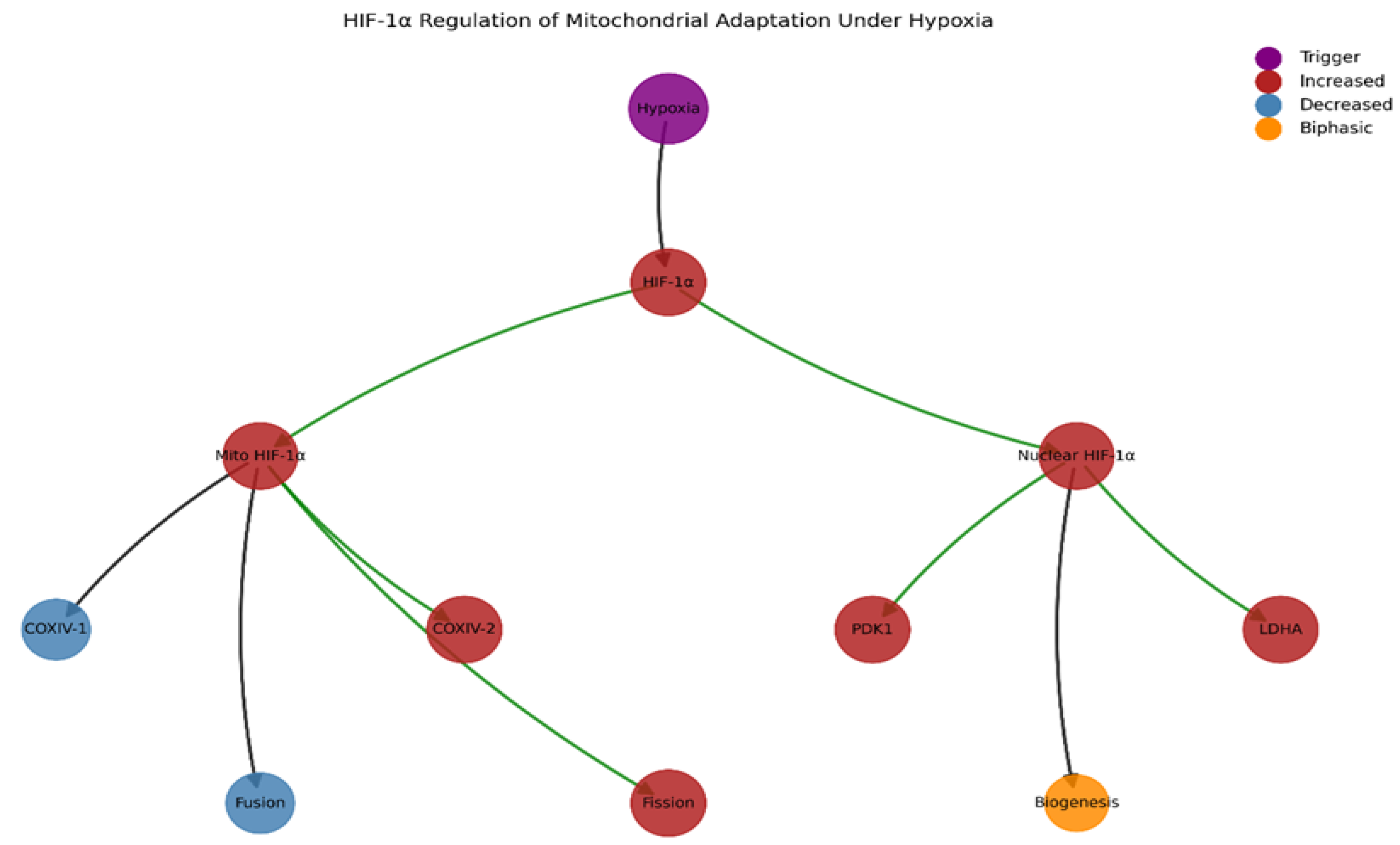

3.4. HIF-1α Regulation Network

| Parameter | Normal Oxygen | Hypoxia |

|---|---|---|

| HIF-1α mitochondrial association | <5% | 15-20% |

| COXIV-1/COXIV-2 ratio | 1.5 | 0.5-0.8 (1d), 2.2-2.5 (3-14d) |

| ATP production (hypoxia) | 100% (baseline) | 70-80% (acute), 85-95% (adapted) |

| ROS production | Low | 2-3× increase (acute), return to baseline (adapted) |

| Mitochondrial P-Drp1/Drp1 ratio | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Mitochondrial fusion protein (OPA1) | 100% (baseline) | 40-60% |

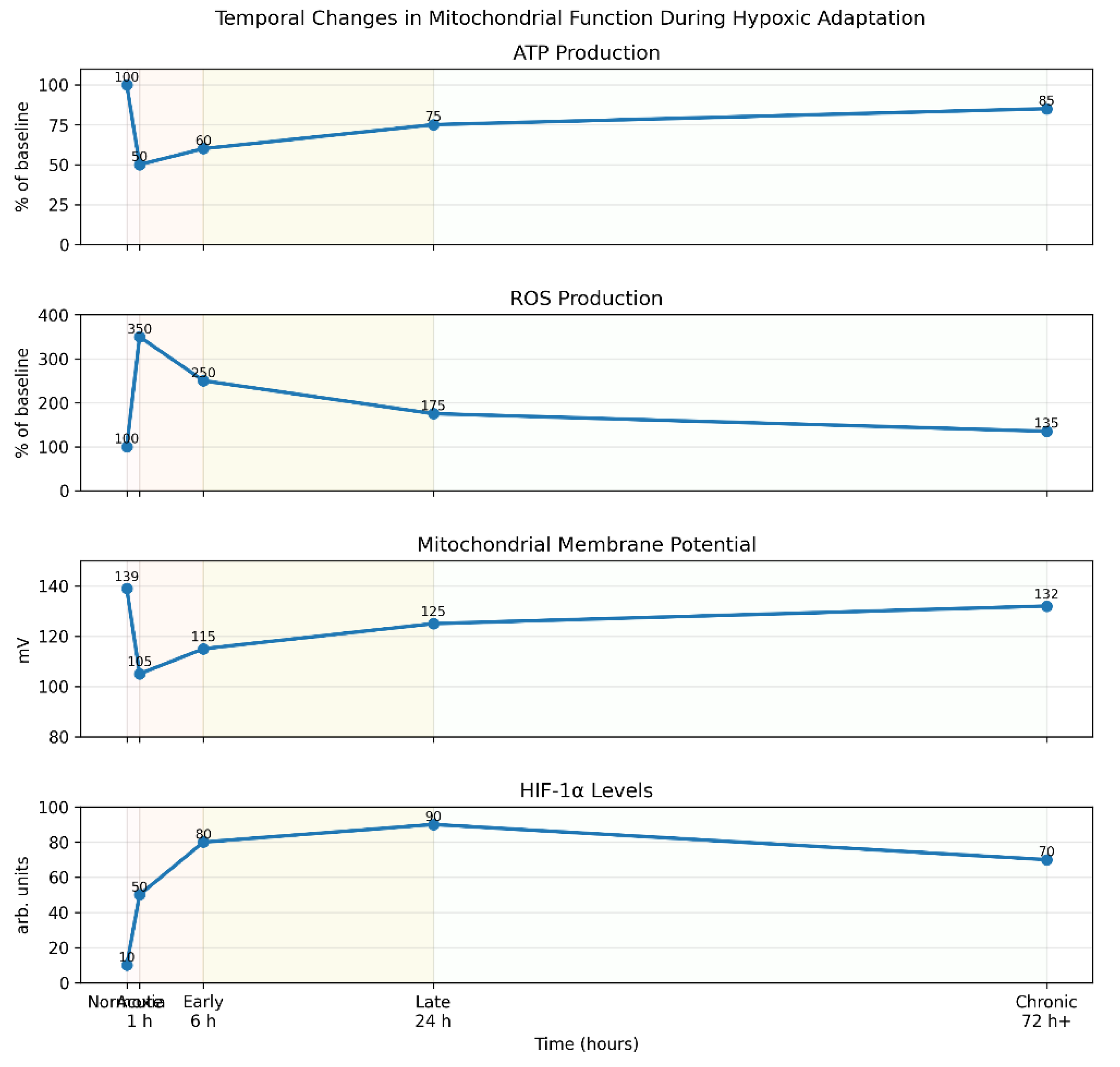

3.5. Temporal Changes During Adaptation

| Timepoint | ATP Production | ROS Production | Mitochondrial Membrane Potential | HIF-1α Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxia | 100% | 100% | -139 mV | Low |

| Acute hypoxia (1h) | 40-60% | 300-400% | -100 to -110 mV | Intermediate |

| Early adaptation (6h) | 50-70% | 200-300% | -110 to -120 mV | High |

| Late adaptation (24h) | 70-80% | 150-200% | -120 to -130 mV | Very high |

| Chronic adaptation (72h+) | 80-90% | 120-150% | -130 to -135 mV | High |

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolutionary Implications of Neuronal Mitochondrial Adaptations

4.2. Bioenergetic Mechanisms and Their Implications

4.3. Implications for Neurodevelopmental and Neurodegenerative Disorders

4.4. Future Directions and Therapeutic Implications

5. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix: Java Code for Visualizations

- import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

- import numpy as np

- import seaborn as sns

- from matplotlib.colors import LinearSegmentedColormap

- from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import Axes3D

- import networkx as nx

- from matplotlib.gridspec import GridSpec

- # Visualization 1: Mitochondrial distribution and oxygen consumption across neuronal compartments

- def plot_neuron_with_mitochondria():

- # Create figure and axis

- fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 8))

- # Custom colormaps for density and oxygen consumption

- density_cmap = LinearSegmentedColormap.from_list("Density",

- ["lightblue", "blue", "darkblue"])

- o2_cmap = LinearSegmentedColormap.from_list("O2_consumption",

- ["lightyellow", "orange", "red"])

- # Define neuronal regions and their properties

- # Format: [x, y, width, height, density, oxygen_consumption]

- soma = [5, 4, 3, 3, 0.9, 0.6] # High density, moderate consumption

- # Format: [[start_x, start_y], [end_x, end_y], width, density, oxygen_consumption]

- proximal_dendrite1 = [[8, 5.5], [12, 7], 0.8, 0.7, 0.8] # High density, high consumption

- proximal_dendrite2 = [[8, 4], [12, 3], 0.8, 0.7, 0.8]

- distal_dendrite1 = [[12, 7], [16, 8], 0.5, 0.4, 0.5] # Medium density, moderate consumption

- distal_dendrite2 = [[12, 3], [16, 2], 0.5, 0.4, 0.5]

- axon_initial = [[5, 2.5], [3, 2], 0.6, 0.2, 0.9] # Low density, very high consumption

- axon_shaft = [[3, 2], [1, 1], 0.3, 0.1, 0.3] # Very low density, low consumption

- terminals = [[0.5, 0.5, 0.7, 0.7, 0.6, 0.9], # Medium density, very high consumption

- [0.8, 1.2, 0.6, 0.6, 0.6, 0.9],

- [1.2, 0.8, 0.5, 0.5, 0.6, 0.9]]

- # Draw soma

- soma_circle = plt.Circle((soma[0], soma[1]), soma[2]/2, color=density_cmap(soma[4]))

- ax.add_patch(soma_circle)

- ax.text(soma[0], soma[1], "Soma\nHighest density\nModerate O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', color='white', fontsize=9)

- # Draw dendrites

- def draw_branch(start, end, width, density, o2):

- # Calculate angle and length

- dx = end[0] - start[0]

- dy = end[1] - start[1]

- angle = np.arctan2(dy, dx)

- length = np.sqrt(dx**2 + dy**2)

- # Draw the branch as a rectangle

- x = start[0]

- y = start[1]

- rect = plt.Rectangle((x, y-width/2), length, width,

- angle=angle*180/np.pi,

- color=density_cmap(density),

- alpha=0.8, origin='center')

- ax.add_patch(rect)

- # Add label

- mid_x = (start[0] + end[0]) / 2

- mid_y = (start[1] + end[1]) / 2

- offset_x = -np.sin(angle) * width

- offset_y = np.cos(angle) * width

- return mid_x + offset_x, mid_y + offset_y

- # Draw proximal dendrites

- label_pos = draw_branch(proximal_dendrite1[0], proximal_dendrite1[1],

- proximal_dendrite1[2], proximal_dendrite1[3], proximal_dendrite1[4])

- ax.text(label_pos[0], label_pos[1], "Proximal dendrites\nHigh density\nHigh O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', color='white', fontsize=8, rotation=15)

- draw_branch(proximal_dendrite2[0], proximal_dendrite2[1],

- proximal_dendrite2[2], proximal_dendrite2[3], proximal_dendrite2[4])

- # Draw distal dendrites

- label_pos = draw_branch(distal_dendrite1[0], distal_dendrite1[1],

- distal_dendrite1[2], distal_dendrite1[3], distal_dendrite1[4])

- ax.text(label_pos[0], label_pos[1], "Distal dendrites\nMedium density\nModerate O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', color='white', fontsize=8, rotation=10)

- draw_branch(distal_dendrite2[0], distal_dendrite2[1],

- distal_dendrite2[2], distal_dendrite2[3], distal_dendrite2[4])

- # Draw axon initial segment

- label_pos = draw_branch(axon_initial[0], axon_initial[1],

- axon_initial[2], axon_initial[3], axon_initial[4])

- ax.text(label_pos[0], label_pos[1]-0.5, "Axon initial segment\nLow density\nVery high O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', fontsize=8)

- # Draw axon shaft

- label_pos = draw_branch(axon_shaft[0], axon_shaft[1],

- axon_shaft[2], axon_shaft[3], axon_shaft[4])

- ax.text(label_pos[0]-0.5, label_pos[1]-0.3, "Axon shaft\nVery low density\nLow O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', fontsize=8)

- # Draw terminals

- for term in terminals:

- term_circle = plt.Circle((term[0], term[1]), term[2]/2, color=density_cmap(term[4]))

- ax.add_patch(term_circle)

- ax.text(terminals[0][0], terminals[0][1]-0.8, "Presynaptic terminals\nMedium density\nVery high O₂",

- ha='center', va='center', fontsize=8)

- # Set limits and remove axes

- ax.set_xlim(0, 17)

- ax.set_ylim(0, 9)

- ax.axis('off')

- # Legend for mitochondrial density

- sm_density = plt.cm.ScalarMappable(cmap=density_cmap)

- sm_density.set_array([])

- cbar_density = plt.colorbar(sm_density, ax=ax, location='right', shrink=0.6)

- cbar_density.set_label('Mitochondrial Density')

- cbar_density.set_ticks([0, 0.5, 1])

- cbar_density.set_ticklabels(['Low', 'Medium', 'High'])

- # Title

- plt.title('Mitochondrial Distribution and Oxygen Consumption across Neuronal Compartments', fontsize=14)

- plt.tight_layout()

- return fig

- # Create and display the neuron visualization

- neuron_fig = plot_neuron_with_mitochondria()

- plt.savefig('visualization1_mitochondrial_distribution.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

- plt.close()

- # Visualization 2: 3D morphological changes in mitochondria under hypoxia

- def plot_mitochondrial_morphology():

- # Create sample data for mitochondrial morphology

- np.random.seed(42) # For reproducibility

- # Normal mitochondria - longer, larger, less fragmented

- n_normal = 40

- normal_length = 2.8 + 0.5 * np.random.randn(n_normal)

- normal_length[normal_length < 1.5] = 1.5 # Enforce minimum length

- normal_width = 0.5 + 0.1 * np.random.randn(n_normal)

- normal_width[normal_width < 0.3] = 0.3 # Enforce minimum width

- normal_volume = 0.17 + 0.03 * np.random.randn(n_normal)

- normal_volume[normal_volume < 0.1] = 0.1 # Enforce minimum volume

- # Hypoxic mitochondria - shorter, smaller, more fragmented

- n_hypoxic = 40

- hypoxic_length = 1.2 + 0.3 * np.random.randn(n_hypoxic)

- hypoxic_length[hypoxic_length < 0.7] = 0.7 # Enforce minimum length

- hypoxic_length[hypoxic_length > 2.0] = 2.0 # Enforce maximum length

- hypoxic_width = 0.4 + 0.08 * np.random.randn(n_hypoxic)

- hypoxic_width[hypoxic_width < 0.2] = 0.2 # Enforce minimum width

- hypoxic_volume = 0.09 + 0.02 * np.random.randn(n_hypoxic)

- hypoxic_volume[hypoxic_volume < 0.05] = 0.05 # Enforce minimum volume

- # Create 3D scatter plot

- fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 9))

- ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

- # Plot normal mitochondria

- normal = ax.scatter(normal_length, normal_width, normal_volume,

- color='blue', s=50, label='Normal Mitochondria')

- # Plot hypoxic mitochondria

- hypoxic = ax.scatter(hypoxic_length, hypoxic_width, hypoxic_volume,

- color='red', s=50, label='Hypoxic Mitochondria')

- # Calculate and plot surface area/volume ratio

- def calculate_surface_area(length, width):

- # Approximate as cylinders with spherical caps

- radius = width / 2

- cylinder_length = length - 2*radius

- cylinder_surface = 2 * np.pi * radius * cylinder_length

- caps_surface = 4 * np.pi * radius**2

- return cylinder_surface + caps_surface

- # Add centroids for each group

- ax.scatter(np.mean(normal_length), np.mean(normal_width), np.mean(normal_volume),

- color='darkblue', s=200, marker='*', label='Normal Centroid')

- ax.scatter(np.mean(hypoxic_length), np.mean(hypoxic_width), np.mean(hypoxic_volume),

- color='darkred', s=200, marker='*', label='Hypoxic Centroid')

- # Add connecting line between centroids to highlight the shift

- ax.plot([np.mean(normal_length), np.mean(hypoxic_length)],

- [np.mean(normal_width), np.mean(hypoxic_width)],

- [np.mean(normal_volume), np.mean(hypoxic_volume)],

- 'k--', alpha=0.5)

- # Add parameter labels and ranges

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.2, 'Normal Length: 2.8 μm', color='blue')

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.19, 'Hypoxic Length: 1.2 μm (-57%)', color='red')

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.16, 'Normal Volume: 0.17 μm³', color='blue')

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.15, 'Hypoxic Volume: 0.09 μm³ (-47%)', color='red')

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.12, 'Normal SA/V: 4.82 μm⁻¹', color='blue')

- ax.text(3.2, 0.6, 0.11, 'Hypoxic SA/V: 6.00 μm⁻¹ (+24%)', color='red')

- # Label axes

- ax.set_xlabel('Length (μm)', fontsize=12)

- ax.set_ylabel('Width (μm)', fontsize=12)

- ax.set_zlabel('Volume (μm³)', fontsize=12)

- # Set axis limits

- ax.set_xlim(0.5, 4)

- ax.set_ylim(0.2, 0.8)

- ax.set_zlim(0.05, 0.25)

- # Add legend and title

- ax.legend(loc='upper left', fontsize=10)

- plt.title('3D Morphological Changes in Neuronal Mitochondria under Hypoxia', fontsize=14)

- # Adjust view angle

- ax.view_init(elev=20, azim=45)

- plt.tight_layout()

- return fig

- # Create and display the mitochondrial morphology visualization

- morphology_fig = plot_mitochondrial_morphology()

- plt.savefig('visualization2_mitochondrial_morphology.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

- plt.close()

- # Visualization 3: Neuronal oxygen consumption rates during development

- def plot_o2_consumption_development():

- # Data for oxygen consumption rates over developmental stages

- age_groups = ['E18-P2', 'P8-P12', 'P16-P20', '≥P28']

- basal_o2 = [6.1, 7.5, 9.0, 10.2] # Values in nM/min/10⁷ cells

- glutamate_o2 = [14.0, 14.5, 14.8, 15.0] # Values in nM/min/10⁷ cells

- k_plus_o2 = [8.0, 10.5, 12.0, 13.5] # Values in nM/min/10⁷ cells

- # Create multi-line plot

- fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

- # Plot each dataset

- ax.plot(age_groups, basal_o2, 'o-', linewidth=2, color='blue', label='Basal')

- ax.plot(age_groups, glutamate_o2, 's-', linewidth=2, color='red', label='Glutamate-stimulated')

- ax.plot(age_groups, k_plus_o2, '^-', linewidth=2, color='green', label='K⁺-stimulated')

- # Add data points with values

- for i, v in enumerate(basal_o2):

- ax.text(i, v+0.2, f"{v}", color='blue', fontweight='bold', ha='center')

- for i, v in enumerate(glutamate_o2):

- ax.text(i, v+0.2, f"{v}", color='red', fontweight='bold', ha='center')

- for i, v in enumerate(k_plus_o2):

- ax.text(i, v+0.2, f"{v}", color='green', fontweight='bold', ha='center')

- # Add shaded area showing the developmental increase

- ax.fill_between(range(len(age_groups)), basal_o2, alpha=0.1, color='blue')

- # Add annotation for key developmental transitions

- ax.annotate('Synaptogenesis\nincreases', xy=(1, 9), xytext=(1.2, 7),

- arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05, width=1.5))

- ax.annotate('Mature activity\npatterns emerge', xy=(3, 13), xytext=(2.5, 11),

- arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05, width=1.5))

- # Customize the plot

- ax.set_xlabel('Developmental Stage', fontsize=12)

- ax.set_ylabel('Oxygen Consumption Rate (nM/min/10⁷ cells)', fontsize=12)

- ax.set_title('Neuronal Oxygen Consumption Rates During Development', fontsize=14)

- ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

- # Add maximum consumption capacity line

- ax.axhline(y=15, color='gray', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

- ax.text(0.1, 15.2, 'Maximum Respiratory Capacity', color='gray', fontsize=10)

- # Add legend

- ax.legend(loc='lower right')

- plt.tight_layout()

- return fig

- # Create and display the oxygen consumption visualization

- o2_fig = plot_o2_consumption_development()

- plt.savefig('visualization3_oxygen_consumption.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

- plt.close()

- # Visualization 4: HIF-1α regulation of mitochondrial adaptation under hypoxia

- def plot_hif1a_network():

- # Create a directed graph

- G = nx.DiGraph()

- # Add nodes with their states under hypoxia

- nodes = {

- 'Hypoxia': {'state': 'trigger', 'pos': (0, 0)},

- 'HIF-1α': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (0, -1)},

- 'Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (-2, -2)},

- 'Nuclear\nHIF-1α': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (2, -2)},

- 'COXIV-1': {'state': 'decreased', 'pos': (-3, -3)},

- 'COXIV-2': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (-1, -3)},

- 'PDK1': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (1, -3)},

- 'LDHA': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (3, -3)},

- 'Mitochondrial\nfusion': {'state': 'decreased', 'pos': (-2, -4)},

- 'Mitochondrial\nfission': {'state': 'increased', 'pos': (0, -4)},

- 'Mitochondrial\nbiogenesis': {'state': 'biphasic', 'pos': (2, -4)},

- }

- # Add nodes to the graph

- for node, attr in nodes.items():

- G.add_node(node, state=attr['state'], pos=attr['pos'])

- # Add edges representing relationships

- edges = [

- ('Hypoxia', 'HIF-1α'),

- ('HIF-1α', 'Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α'),

- ('HIF-1α', 'Nuclear\nHIF-1α'),

- ('Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α', 'COXIV-1'),

- ('Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α', 'COXIV-2'),

- ('Nuclear\nHIF-1α', 'PDK1'),

- ('Nuclear\nHIF-1α', 'LDHA'),

- ('Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α', 'Mitochondrial\nfusion'),

- ('Mitochondrial\nHIF-1α', 'Mitochondrial\nfission'),

- ('Nuclear\nHIF-1α', 'Mitochondrial\nbiogenesis'),

- ]

- # Add edges to the graph

- G.add_edges_from(edges)

- # Prepare node colors based on state

- node_colors = []

- for node in G.nodes():

- state = G.nodes[node]['state']

- if state == 'increased':

- node_colors.append('red')

- elif state == 'decreased':

- node_colors.append('blue')

- elif state == 'trigger':

- node_colors.append('purple')

- else: # biphasic

- node_colors.append('orange')

- # Prepare edge styles

- edge_colors = []

- for u, v in G.edges():

- source_state = G.nodes[u]['state']

- target_state = G.nodes[v]['state']

- if source_state == target_state:

- edge_colors.append('green') # Same direction effect

- else:

- edge_colors.append('red') # Opposing effect

- # Create figure

- fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 10))

- # Get positions from node attributes

- pos = nx.get_node_attributes(G, 'pos')

- # Draw the graph

- nx.draw_networkx_nodes(G, pos, node_size=2000, node_color=node_colors, alpha=0.7)

- nx.draw_networkx_labels(G, pos, font_size=10, font_weight='bold')

- nx.draw_networkx_edges(G, pos, edge_color=edge_colors, width=2, arrowsize=20,

- connectionstyle='arc3,rad=0.1')

- # Add legend for node colors

- legend_elements = [

- plt.Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='w', markerfacecolor='red', markersize=15, label='Increased'),

- plt.Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='w', markerfacecolor='blue', markersize=15, label='Decreased'),

- plt.Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='w', markerfacecolor='purple', markersize=15, label='Trigger'),

- plt.Line2D([0], [0], marker='o', color='w', markerfacecolor='orange', markersize=15, label='Biphasic'),

- ]

- ax.legend(handles=legend_elements, loc='upper right')

- # Add annotations

- plt.annotate('Electron Transport\nChain Adaptation', xy=(-2, -3), xytext=(-4, -2.5),

- arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05, width=1), fontsize=10)

- plt.annotate('Metabolic\nShift', xy=(2, -3), xytext=(4, -2.5),

- arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05, width=1), fontsize=10)

- plt.annotate('Morphological\nAdaptation', xy=(0, -4), xytext=(0, -5),

- arrowprops=dict(facecolor='black', shrink=0.05, width=1), fontsize=10)

- plt.title('HIF-1α Regulation of Mitochondrial Adaptation under Hypoxia', fontsize=14)

- # Remove axes

- plt.axis('off')

- plt.tight_layout()

- return fig

- # Create and display the HIF-1α network visualization

- hif_fig = plot_hif1a_network()

- plt.savefig('visualization4_hif1a_network.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

- plt.close()

- # Visualization 5: Temporal changes in mitochondrial function during hypoxic adaptation

- def plot_temporal_adaptation():

- # Create data for the temporal changes

- time_points = [0, 1, 6, 24, 72] # Hours

- time_labels = ['Normoxia', 'Acute\n(1h)', 'Early\n(6h)', 'Late\n(24h)', 'Chronic\n(72h+)']

- # Data as percentages of baseline (normoxia)

- atp_production = [100, 50, 60, 75, 85]

- ros_production = [100, 350, 250, 175, 135]

- membrane_potential = [139, 105, 115, 125, 132] # Absolute values in mV

- hif1a_levels = [10, 50, 80, 90, 70] # Arbitrary units

- # Create multi-panel visualization

- fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

- gs = GridSpec(4, 1, height_ratios=[1, 1, 1, 1])

- # ATP Production Panel

- ax1 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0])

- ax1.plot(time_points, atp_production, 'o-', linewidth=2, color='blue', label='ATP Production')

- ax1.set_ylabel('% of Baseline')

- ax1.set_title('ATP Production')

- ax1.set_ylim(0, 110)

- ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

- # Add data point labels

- for i, v in enumerate(atp_production):

- ax1.text(time_points[i], v+5, f"{v}%", ha='center')

- # ROS Production Panel

- ax2 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1])

- ax2.plot(time_points, ros_production, 'o-', linewidth=2, color='red', label='ROS Production')

- ax2.set_ylabel('% of Baseline')

- ax2.set_title('ROS Production')

- ax2.set_ylim(0, 400)

- ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

- # Add data point labels

- for i, v in enumerate(ros_production):

- ax2.text(time_points[i], v+20, f"{v}%", ha='center')

- # Membrane Potential Panel

- ax3 = fig.add_subplot(gs[2])

- ax3.plot(time_points, membrane_potential, 'o-', linewidth=2, color='green', label='Membrane Potential')

- ax3.set_ylabel('mV')

- ax3.set_title('Mitochondrial Membrane Potential')

- ax3.set_ylim(80, 150)

- ax3.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

- # Add data point labels

- for i, v in enumerate(membrane_potential):

- ax3.text(time_points[i], v+3, f"{v} mV", ha='center')

- # HIF-1α Levels Panel

- ax4 = fig.add_subplot(gs[3])

- ax4.plot(time_points, hif1a_levels, 'o-', linewidth=2, color='purple', label='HIF-1α Levels')

- ax4.set_ylabel('Arbitrary Units')

- ax4.set_title('HIF-1α Levels')

- ax4.set_ylim(0, 100)

- ax4.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

- # Add data point labels

- for i, v in enumerate(hif1a_levels):

- ax4.text(time_points[i], v+5, f"{v}", ha='center')

- # Set common x-axis labels

- ax4.set_xlabel('Time')

- ax4.set_xticks(time_points)

- ax4.set_xticklabels(time_labels)

- # Hide x labels for top plots

- ax1.set_xticklabels([])

- ax2.set_xticklabels([])

- ax3.set_xticklabels([])

- # Add adaptive phases

- for ax in [ax1, ax2, ax3, ax4]:

- ax.axvspan(0, 1, alpha=0.1, color='red', label='Acute Phase')

- ax.axvspan(1, 6, alpha=0.1, color='orange', label='Early Adaptation')

- ax.axvspan(6, 24, alpha=0.1, color='yellow', label='Late Adaptation')

- ax.axvspan(24, 72, alpha=0.1, color='green', label='Chronic Adaptation')

- # Add overall title

- fig.suptitle('Temporal Changes in Mitochondrial Function During Hypoxic Adaptation', fontsize=16)

- # Add legend for phases only on the top panel

- handles, labels = ax1.get_legend_handles_labels()

- ax1.legend(handles=handles[1:], labels=['Acute Phase', 'Early Adaptation', 'Late Adaptation', 'Chronic Adaptation'],

- loc='lower right', fontsize=8)

- plt.tight_layout()

- plt.subplots_adjust(top=0.92, hspace=0.4)

- return fig

- # Create and display the temporal adaptation visualization

- temporal_fig = plot_temporal_adaptation()

- plt.savefig('visualization5_temporal_adaptation.png', dpi=300, bbox_inches='tight')

- plt.close()

- # Display messages to confirm all visualizations have been created

- print("All visualizations have been created successfully:")

- print("1. Visualization1: Mitochondrial distribution and oxygen consumption across neuronal compartments")

- print("2. Visualization2: 3D morphological changes in mitochondria under hypoxia")

- print("3. Visualization3: Neuronal oxygen consumption rates during development")

- print("4. Visualization4: HIF-1α regulation of mitochondrial adaptation under hypoxia")

- print("5. Visualization5: Temporal changes in mitochondrial function during hypoxic adaptation")

References

- Attwell, D.; Laughlin, S.B. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2001, 21, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Bertram, R.; Pedersen, M.G.; Luciani, D.S.; Sherman, A. A simplified model for mitochondrial ATP production. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2006, 243, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortassa, S.; O'Rourke, B.; Aon, M.A. Redox-optimized ROS balance and the relationship between mitochondrial respiration and ROS. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 2014, 1837, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, F.O.; Fabre, N.N.; Ragland, G.J. The mitochondrial genome of the amblypygid Damon diadema (Simon, 1876) (Arachnida, Amblypygi, Phrynichidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2019, 4, 1706–1707. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, G.C.; Bartol, T.M.; Sejnowski, T.J.; Rangamani, P. Mitochondrial morphology provides a mechanism for energy buffering at synapses. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.C.; Eaton, S.L.; Brunton, P.J.; Atrih, A.; Smith, C.; Lamont, D.J.; Wishart, T.M. Proteomic profiling of neuronal mitochondria reveals modulators of synaptic architecture. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2017, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.W.; Burger, G.; Lang, B.F. The origin and early evolution of mitochondria. Genome Biology 2001, 2, reviews1018–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, C.; Gleeson, P.; Attwell, D. Updated energy budgets for neural computation in the neocortex and cerebellum. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2012, 32, 1222–1232. [Google Scholar]

- Iwata, R.; Casimir, P.; Vanderhaeghen, P. Mitochondria metabolism sets the species-specific tempo of neuronal development. Science 2023, 379, eabn4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, I.H.; Zazzeron, L.; Goli, R.; Alexa, K.; Schatzman-Bone, S.; Dhillon, H. Hypoxia as a therapy for mitochondrial disease. Science 2016, 352, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A. The number and distribution of capillaries in muscles with calculations of the oxygen pressure head necessary for supplying the tissue. Journal of Physiology 1919, 52, 409–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagerlund, T.D.; Low, P.A. Axial diffusion and Michaelis-Menten kinetics in oxygen delivery in rat peripheral nerve. American Journal of Physiology 1991, 260, R430–R440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.J.; Auwerx, J. Mitochondria: A "pacemaker" for species-specific development. Molecular Cell 2023, 83, 824–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukyanova, L.D. Mitochondrial signaling in hypoxia. Open Journal of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases 2014, 4, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti, P.J.; Allaman, I. A cellular perspective on brain energy metabolism and functional imaging. Neuron 2015, 86, 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misgeld, T.; Schwarz, T.L. Mitostasis in neurons: maintaining mitochondria in an extended cellular architecture. Neuron 2017, 96, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mootha, V.K.; Bunkenborg, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Hjerrild, M.; Wisniewski, J.R.; Stahl, E. Integrated analysis of protein composition, tissue diversity, and gene regulation in mouse mitochondria. Cell 2003, 115, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niven, J.E.; Laughlin, S.B. Energy limitation as a selective pressure on the evolution of sensory systems. Journal of Experimental Biology 2008, 211, 1792–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumsey, W.L.; Schlosser, C.; Nuutinen, E.M.; Robiolio, M.; Wilson, D.F. Cellular energetics and the oxygen dependence of respiration in cardiac myocytes isolated from adult rat. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1990, 265, 15392–15402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) pathway. Science's STKE 2007, 2007, cm8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speijer, D. Oxygen radicals shaping evolution: why fatty acid catabolism leads to peroxisomes while neurons do without it: FADH₂/NADH flux ratios determining mitochondrial radical formation were crucial for the eukaryotic invention of peroxisomes and catabolic tissue differentiation. BioEssays 2011, 33, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Speijer, D. How and why did mitochondria become essential parts of eukaryotic cells? BioEssays 2022, 44, 2200090. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C.T.; McElwain, J.C. Ancient atmospheres and the evolution of oxygen sensing via the hypoxia-inducible factor in metazoans. Physiology 2010, 25, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, W.W.; Wei, A.C. Kinetic Mathematical Modeling of Oxidative Phosphorylation in Cardiomyocyte Mitochondria. Cells 2022, 11, 4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. A general model for ontogenetic growth. Nature 2001, 413, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.F.; Rumsey, W.L. Factors modulating the oxygen dependence of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 1988, 222, 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.F.; Owen, C.S.; Erecińska, M. Quantitative dependence of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation on oxygen concentration: a mathematical model. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 1979, 195, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yellen, G. Fueling thought: Management of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation in neuronal metabolism. Journal of Cell Biology 2018, 217, 2235–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).