Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

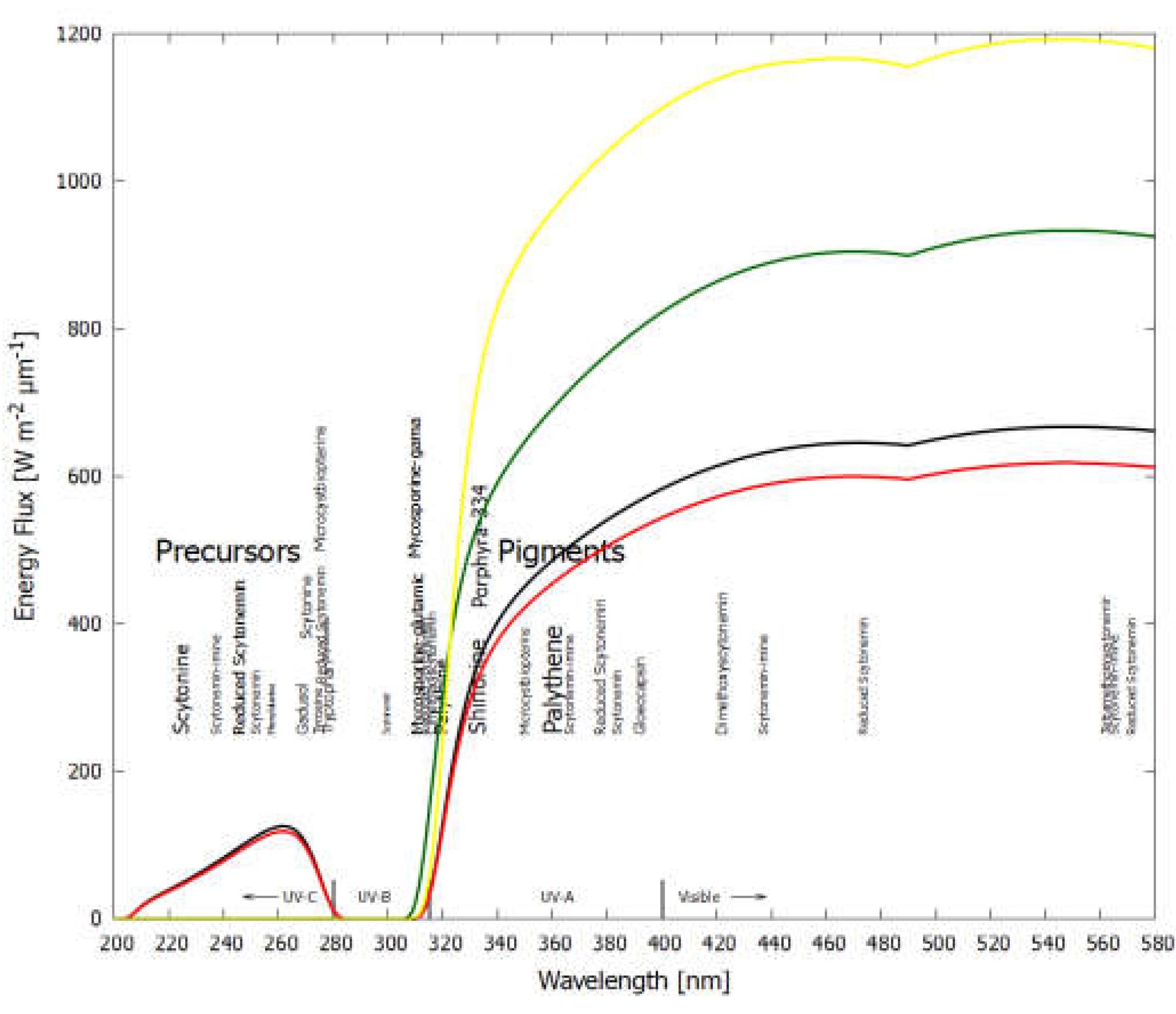

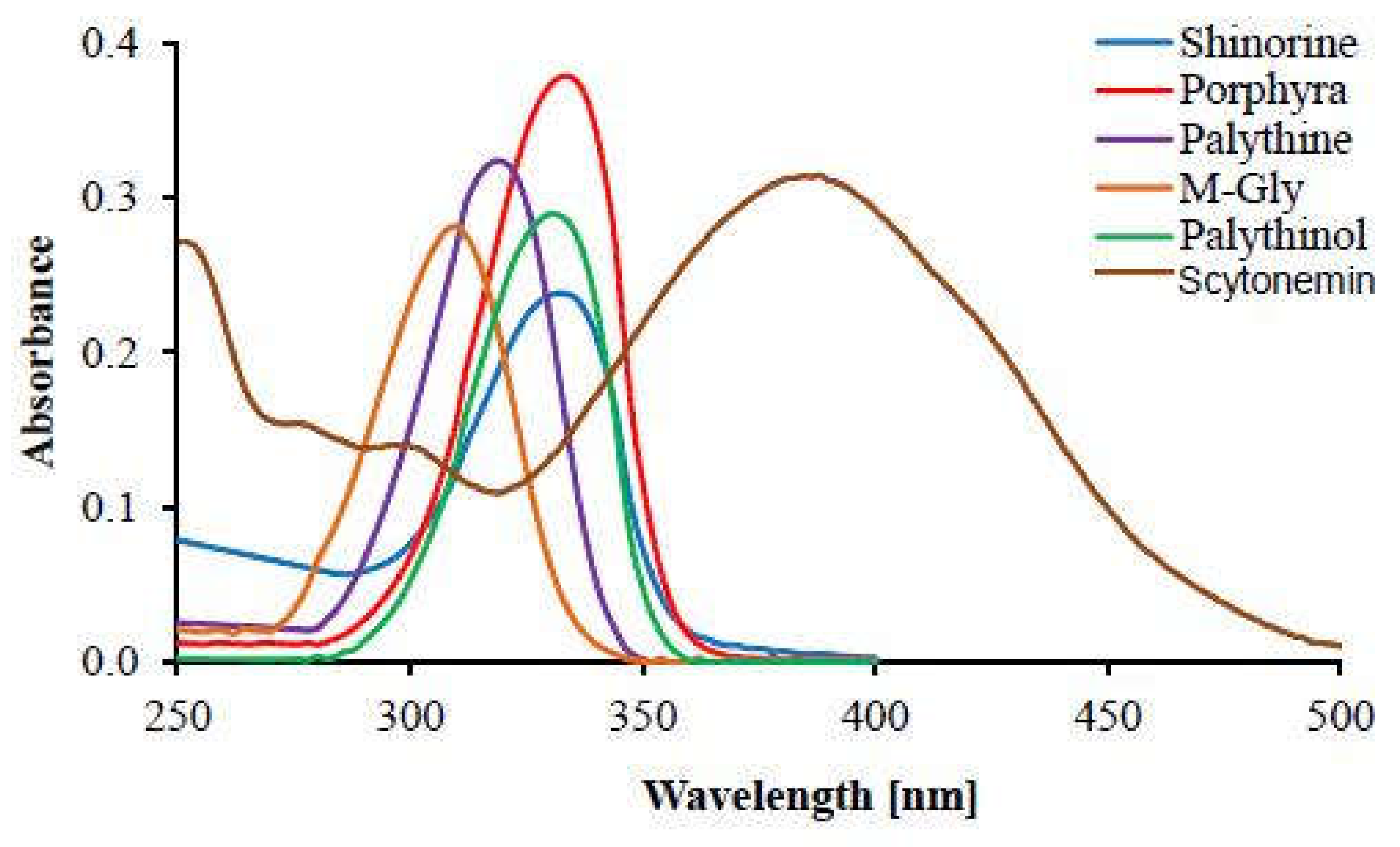

2. Properties of Cyanobacterial UV-Absorbing Pigments

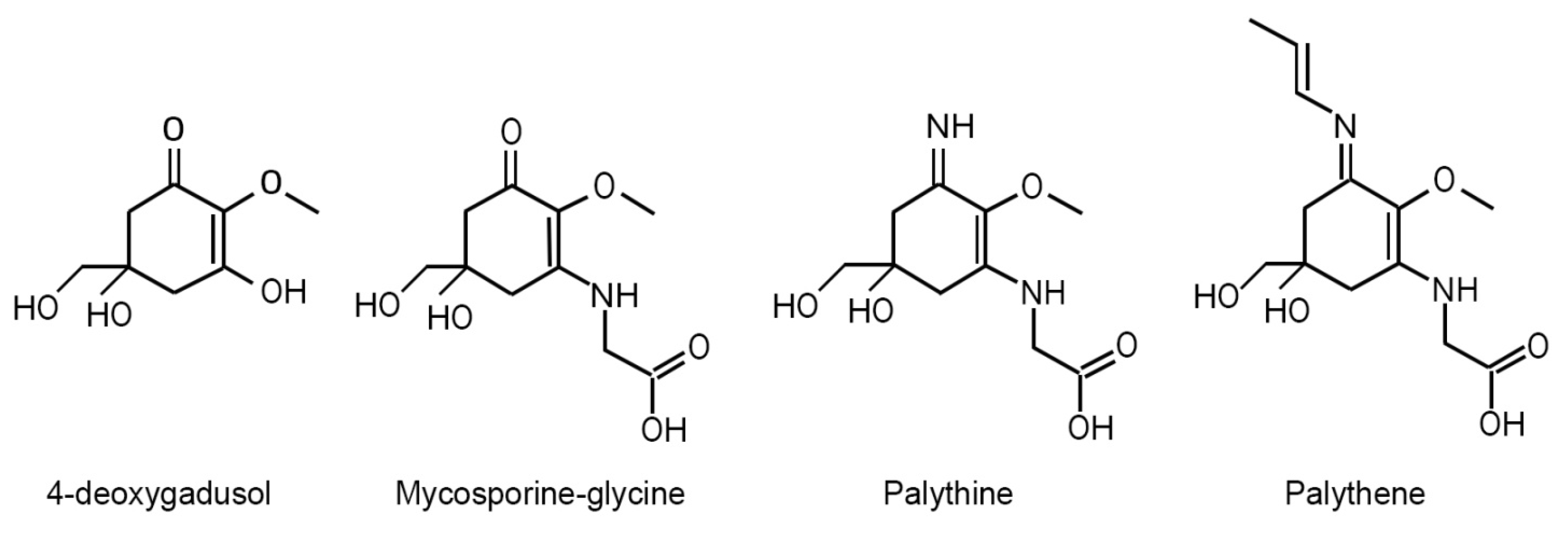

2.1. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs)

2.1.1. Physicochemical Properties

2.1.2. Ecological Distribution

2.1.3. Biosynthesis

2.1.4. Function: Traditional Protective View vs. Thermodynamic View

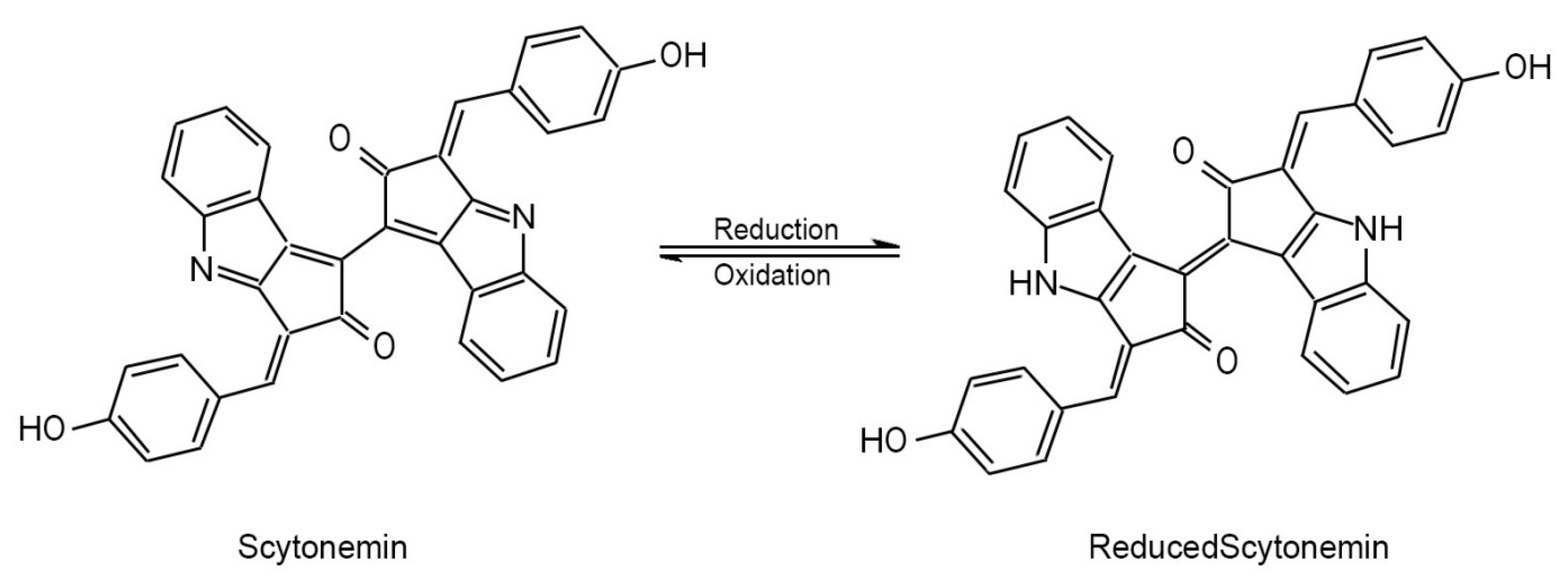

2.2. Scytonemins

2.2.1. Physicochemical Properties

2.2.2. Ecological Distribution

2.2.3. Biosynthesis

2.2.4. Function: Traditional Protective View vs. Thermodynamic View

- Inability to explain the strong visible absorption bands of scytonemin-imine, where photosynthetic pigments absorb. The question is raised by Grant and Louda (2013):

- 2.

- Inability to explain the production of the strongly UV-C/UV-B-absorbing methoxyscytonemins and scytonine, in spite of the absence of UV-C wavelengths and the low intensity of UV-B in today’s surface solar spectrum. The question is raised by Varnali and Edwards (2010):

- 3.

- Inability to explain why many species of cyanobacteria do not synthesize scytonemins nor MAAs but, nevertheless, successfully cope with UV-induced cellular damage by employing only metabolic repair mechanisms (Quesada and Vincent, 1997; Castenholz and Garcia-Pichel, 2000; Singh et al., 2023).

- 4.

- Soule et al. (2007) developed scytoneminless mutant of the cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme which proved to have indistinguishable growth rate from the wild type after both were subjected to UV-A irradiation. The conclusion of the authors was that other photoprotective mechanisms can fully accommodate the absence of scytonemin in the mutant.

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

References

- Abed, R.M.; Al Kharusi, S.; Schramm, A.; Robinson, M.D. Bacterial diversity, pigments and nitrogen fixation of biological desert crusts from the Sultanate of Oman. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 72, 418–428. [CrossRef]

- Arpin, N., Curt, R. and Favre-Bonvin, J.: Mycosporines: mise au point et donées nouvelles concernant leurs structures, leur distribution, leur localisation et leur biogenèse, Rev Mycol, 43,.

- 247–257, 1979.

- Arsın, S.; Delbaje, E.; Jokela, J.; Wahlsten, M.; Farrar, Z.M.; Permi, P.; Fewer, D. A Plastic Biosynthetic Pathway for the Production of Structurally Distinct Microbial Sunscreens. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 1959–1967. [CrossRef]

- Awramik, S.; Schopf, J.; Walter, M. Filamentous fossil bacteria from the Archean of Western Australia. 2003, 20, 357–374. [CrossRef]

- Babin, M., Stramski, D., Ferrari, G. M., Claustre, H., Bricaud, A., Obolensky, G., Hoepffner, N.: Variations in the light absorption coefficients of phyto-plankton, nonalgal particles, and dissolved organic matter in coastal waters around Europe, J. Geophys. Res, 108(C7), 3211, 2003.

- Balskus, E.P.; Walsh, C.T. Investigating the Initial Steps in the Biosynthesis of Cyanobacterial Sunscreen Scytonemin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 15260–15261. [CrossRef]

- Balskus, E.P.; Walsh, C.T. An Enzymatic Cyclopentyl[b]indole Formation Involved in Scytonemin Biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14648–14649. [CrossRef]

- Balskus, E.P.; Walsh, C.T. The Genetic and Molecular Basis for Sunscreen Biosynthesis in Cyanobacteria. Science 2010, 329, 1653–1656. [CrossRef]

- Balskus, E.P.; Case, R.J.; Walsh, C.T. The biosynthesis of cyanobacterial sunscreen scytonemin in intertidal microbial mat communities. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 77, 322–332. [CrossRef]

- Bandaranayake, W. M.: Mycosporines: are they nature’s sunscreens?, Natural Product Reports, 1998, 159–171, 1998.

- Belnap, J. and Lange, O. L.: Biological Soil Crusts: Structure, Function, and Management,.

- Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany, 2001.

- Beraldi-Campesi, H.; Farmer, J.D.; Garcia-Pichel, F. MODERN TERRESTRIAL SEDIMENTARY BIOSTRUCTURES AND THEIR FOSSIL ANALOGS IN MESOPROTEROZOIC SUBAERIAL DEPOSITS. PALAIOS 2014, 29, 45–54. [CrossRef]

- Berezin, M.Y.; Achilefu, S. Fluorescence Lifetime Measurements and Biological Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2641–2684. [CrossRef]

- Brenowitz, S. and Castenholz, R. W.: Long-term effects of UV and visible irradiance on natural populations of a scytonemin-containing cyanobacterium (Calothrix sp.), FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 24, 343–352, 1997.

- Bricaud, A.; Babin, M.; Claustre, H.; Ras, J.; Tièche, F. Light absorption properties and absorption budget of Southeast Pacific waters. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2010, 115. [CrossRef]

- Büdel, B., Karsten, U. and Garcia-Pichel, F.: Ultraviolet absorbing scytonemin and mycosporine-like amino acid derivatives in exposed, rock-inhabiting cyanobacterial lichens, Oecologia, 112, 165–172, 1997.

- Bultel-Poncé, V., Felix-Theodose, F., Sarlhou, C., Ponge, J. F. and Bodo, B.: New pigments from the terrestrial cyanobacterium Scytonema sp. collected on the Mitakara Inselberg, French Guyana, J Nat Prod, 67, 678–681, 2004.

- Busch, F.; Rajendran, C.; Heyn, K.; Schlee, S.; Merkl, R.; Sterner, R. Ancestral Tryptophan Synthase Reveals Functional Sophistication of Primordial Enzyme Complexes. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 709–715. [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.J.; Mayer, L.M. Enrichment of dissolved phenolic material in the surface microlayer of coastal waters. Nature 1980, 286, 482–483. [CrossRef]

- Carreto, J. I. and Carignan, M. O.: Mycosporine-like amino acids: relevant secondary metabolites. Chemical and ecological aspects, Mar Drugs, 9, 387−446, 2011.

- Carreto, J.; Carignan, M.; Daleo, G.; Marco, S. Occurrence of mycosporine-like amino acids in the red-tide dinoflagellate Alexandrium excavatum: UV-photoprotective compounds?. J. Plankton Res. 1990, 12, 909–921. [CrossRef]

- Carreto, J.I.; Carignan, M.O.; Montoya, N.G. A high-resolution reverse-phase liquid chromatography method for the analysis of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in marine organisms. Mar. Biol. 2004, 146, 237–252. [CrossRef]

- Carreto, J. I., Roy, S., Whitehead, K., Llewellyn, C. A. and Carignan, M. O.: UV-absorbing ‘pigments’: mycosporine-like amino acids. In: Roy, S., Llewellyn, C. A., Egeland, E. S. and Johnsen, G. (eds.) Phytoplankton pigments: characterisation, chemotaxonomy and applications in oceanography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 412−441, 2011.

- Carroll, A.K.; Shick, J.M. Dietary accumulation of UV-absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) by the green sea urchin (Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis). Mar. Biol. 1996, 124, 561–569. [CrossRef]

- Castenholz, R. W. and Garcia-Pichel, F.: Cyanobacterial responses to UV-radiation. In: Whitton, B. A. and Potts, M. (eds.) The ecology of cyanobacteria. Their diversity in time and space, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 591–611, 669, 2000.

- Castenholz, R. W. and Garcia-Pichel, F.: Cyanobacterial responses to UV radiation, In: Whitton, B. A. (ed.) Ecology of Cyanobacteria II: Their Diversity in Space and Time, Springer Netherlands, 481-499, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Clementson, L.A.; Oubelkheir, K.; Ford, P.W.; Blondeau-Patissier, D. Distinct Peaks of UV-Absorbing Compounds in CDOM and Particulate Absorption Spectra of Near-Surface Great Barrier Reef Coastal Waters, Associated with the Presence of Trichodesmium spp. (NE Australia). Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 3686. [CrossRef]

- Cockell, C. S. and Knowland, J.: Ultraviolet radiation screening compounds, Biol. Rev., 74, 311–345, 1999.

- Cohen, G. N.: Microbial Biochemistry, (3rd edition), Springer, Netherlands, pages: 85-90 and 415-440, 2014.

- Colica, G.; Li, H.; Rossi, F.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; De Philippis, R. Microbial secreted exopolysaccharides affect the hydrological behavior of induced biological soil crusts in desert sandy soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 68, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Conde, F. R., Churio, M. S. and Previtali, C. M.: The photoprotector mechanism of mycosporine-like amino acids. Excited state properties and photostability of porphyra-334 in aqueous solution, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, 56, 139–144, 2000.

- Conde, F.R.; Churio, M.S.; Previtali, C.M. The deactivation pathways of the excited-states of the mycosporine-like amino acids shinorine and porphyra-334 in aqueous solution. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2004, 3, 960–967. [CrossRef]

- Conde, F.R.; Churio, M.S.; Previtali, C.M. Experimental study of the excited-state properties and photostability of the mycosporine-like amino acid palythine in aqueous solution. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007, 6, 669–674. [CrossRef]

- Couradeau, E.; Karaoz, U.; Lim, H.C.; da Rocha, U.N.; Northen, T.; Brodie, E.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Bacteria increase arid-land soil surface temperature through the production of sunscreens. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10373–10373. [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, P.M.; Javalkote, V.S.; Mazmouz, R.; Pickford, R.; Puranik, P.R.; Neilan, B.A. Comparative Profiling and Discovery of Novel Glycosylated Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids in Two Strains of the Cyanobacterium Scytonema cf. crispum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5951–5959. [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. Metabolites Facilitating Adaptation of Desert Cyanobacteria to Extremely Arid Environments. Plants 2022, 11, 3225. [CrossRef]

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Adams, W.W., III. Photoprotection and Other Responses of Plants to High Light Stress. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 43, 599–626. [CrossRef]

- Demoulin, C.F.; Lara, Y.J.; Cornet, L.; François, C.; Baurain, D.; Wilmotte, A.; Javaux, E.J. Cyanobacteria evolution: Insight from the fossil record. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 140, 206–223. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J.G.; Castenholz, R.W. SCYTONEMIN, A CYANOBACTERIAL SHEATH PIGMENT, PROTECTS AGAINST UVC RADIATION: IMPLICATIONS FOR EARLY PHOTOSYNTHETIC LIFE. J. Phycol. 1999, 35, 673–681. [CrossRef]

- Dillon, J. G., Tatsumi, C. M., Tandingan, P. G. and Castenholz, R. W.: Effect of environmental factors on the synthesis of scytonemin, a UV-screening pigment, in a cyanobacterium (Chroococcidiopsis sp.), Arch. Microbiol., 177, 322–331, 2002.

- Dunlap, W.C.; Chalker, B.E. Identification and quantitation of near-UV absorbing compounds (S-320) in a hermatypic scleractinian. Coral Reefs 1986, 5, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, W. C. and Shick, J. M.: Ultraviolet radiation absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids in coral reef organisms: a biochemical and environmental environmental perspective, J Phycol, 34, 418–430, 1998.

- Edwards, H.G.M.; Villar, S.E.J.; Pullan, D.; Hargreaves, M.D.; Hofmann, B.A.; Westall, F. Morphological biosignatures from relict fossilised sedimentary geological specimens: a Raman spectroscopic study. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2007, 38, 1352–1361. [CrossRef]

- Ehling-Schulz, M. and Scherer, S.: UV protection in cyanobacteria, Eur J Phycol, 34, 329–338, 1999.

- Ehling-Schulz, M.; Bilger, W.; Scherer, S. UV-B-induced synthesis of photoprotective pigments and extracellular polysaccharides in the terrestrial cyanobacterium Nostoc commune. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 1940–1945. [CrossRef]

- Ekebergh, A.; Sandin, P.; Mårtensson, J. On the photostability of scytonemin, analogues thereof and their monomeric counterparts. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2015, 14, 2179–2186. [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.D.; Johansen, J.R. Microbiotic Crusts and Ecosystem Processes. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 1999, 18, 183–225. [CrossRef]

- Favre-Bonvin, J.; Arpin, N.; Brevard, C. Structure de la mycosporine (P 310). Can. J. Chem. 1976, 54, 1105–1113. [CrossRef]

- Favre-Bonvin, J.; Bernillon, J.; Salin, N.; Arpin, N. Biosynthesis of mycosporines: Mycosporine glutaminol in Trichothecium roseum. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2509–2514. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, D.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Mutational Studies of Putative Biosynthetic Genes for the Cyanobacterial Sunscreen Scytonemin in Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 735. [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, L.; Klisch, M.; Pancaldi, S.; Häder, D.-P. Complementary UV-Absorption of Mycosporine-like Amino Acids and Scytonemin is Responsible for the UV-Insensitivity of Photosynthesis in Nostoc flagelliforme. Mar. Drugs 2010, 8, 106–121. [CrossRef]

- Fleming, E. D. and Castenholz, R. W.: Effects of periodic desiccation on the synthesis of the UV-screening compound, scytonemin, in cyanobacteria, Environ Microbiol, 9, 1448–1455, 2007.

- Fuentes-Tristan, S.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Iqbal, H.M.; Carrillo-Nieves, D. Bioinspired biomolecules: Mycosporine-like amino acids and scytonemin from Lyngbya sp. with UV-protection potentialities. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2019, 201, 111684. [CrossRef]

- Fulton, J.M.; Arthur, M.A.; Freeman, K.H. Subboreal aridity and scytonemin in the Holocene Black Sea. Org. Geochem. 2012, 49, 47–55. [CrossRef]

- Fukuzaki, K.; Imai, I.; Fukushima, K.; Ishii, K.-I.; Sawayama, S.; Yoshioka, T. Fluorescent characteristics of dissolved organic matter produced by bloom-forming coastal phytoplankton. J. Plankton Res. 2014, 36, 685–694. [CrossRef]

- Galgani, L. and Engel, A.: Changes in optical characteristics of surface microlayers hint to photochemically and microbially mediated DOM turnover in the upwelling region off the coast of Peru, Biogeosciences, 13, 2453–2473, 2016.

- Gao, Q.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Microbial ultraviolet sunscreens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 791–802. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Jing, X.; Liu, X.; Lindblad, P. Biotechnological Production of the Sunscreen Pigment Scytonemin in Cyanobacteria: Progress and Strategy. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 129. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F. Solar Ultraviolet and the Evolutionary History of Cyanobacteria. Discov. Life 1998, 28, 321–347. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F. and Castenholz, R. W.: Characterization and biological implications of scytonemin, a cyanobacterial sheath pigment, J Phycol, 27, 395–409, 1991.

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Castenholz, R.W. Occurrence of UV-Absorbing, Mycosporine-Like Compounds among Cyanobacterial Isolates and an Estimate of Their Screening Capacity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 163–169. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel, F.; Sherry, N.D.; Castenholz, R.W. EVIDENCE FOR AN ULTRAVIOLET SUNSCREEN ROLE OF THE EXTRACELLULAR PIGMENT SCYTONEMIN IN THE TERRESTRIAL CYANOBACTERIUM Chiorogloeopsis sp.. Photochem. Photobiol. 1992, 56, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Geraldes, V.; Pinto, E. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs): Biology, Chemistry and Identification Features. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 63. [CrossRef]

- Glansdorff, P. and Prigogine, I.: Thermodynamic Theory of Structure, Stability, and Fluctuations, Wiley-Interscience, London, 1971.

- Gnanadesikan, A.; Emanuel, K.; Vecchi, G.A.; Anderson, W.G.; Hallberg, R. How ocean color can steer Pacific tropical cyclones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37. [CrossRef]

- Golubic, S. and Abed, R. M. M.: Entophysalis mats as environmental regulators, In: Seckbach, J. and Oren, A. (eds.) Microbial Mats, Modern and Ancient Microorganisms in Stratified Systems, Springer, Heidelberg, pp 237–251, 2010.

- Golubic, S. and Hofmann, H. J.: Comparison of Holocene and mid-Precambrian Entophysalidaceae (Cyanophyta) in stromatolitic algal mats: cell division and degradation, J.

- Paleontol., 50, 1074–1082, 1976.

- Grant, C.S.; Louda, J. Scytonemin-imine, a mahogany-colored UV/Vis sunscreen of cyanobacteria exposed to intense solar radiation. Org. Geochem. 2013, 65, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Guttman, M.; Leverenz, R.L.; Zhumadilova, K.; Pawlowski, E.G.; Petzold, C.J.; Lee, K.K.; Ralston, C.Y.; Kerfeld, C.A. Local and global structural drivers for the photoactivation of the orange carotenoid protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, E5567–E5574. [CrossRef]

- Hatakeyama, M.; Nakamura, S. “Button-on-a-String” Mechanism in Water, the Ultrafast UV-to-Heat Conversion by Mycosporine-like Amino Acid Porphyra-334 of Natural Sunscreen Compound. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2025. [CrossRef]

- Häder, D.-P.; Kumar, H.D.; Smith, R.C.; Worrest, R.C. Aquatic ecosystems: effects of solar ultraviolet radiation and interactions with other climatic change factors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2003, 2, 39–50. [CrossRef]

- Hickman-Lewis, K.; Cavalazzi, B.; Giannoukos, K.; D'Amico, L.; Vrbaski, S.; Saccomano, G.; Dreossi, D.; Tromba, G.; Foucher, F.; Brownscombe, W.; et al. Advanced two- and three-dimensional insights into Earth's oldest stromatolites (ca. 3.5 Ga): Prospects for the search for life on Mars. Geology 2022, 51, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Hirakawa, Y.; Kakegawa, T.; Furukawa, Y. Hexose phosphorylation for a non-enzymatic glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway on early Earth. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H. J.: Precambrian microflora, Belcher Islands, Canada: significance and systematic, J Paleontol., 50, 1040–1073, 1976.

- Holland, H. D.: The Geologic History of Seawater, In: Holland, H. D. and Turekian, K. K. (eds.), Treatise on Geochemistry, Volume 6; (ISBN: 0-08-044341-9); pp. 583–625, Elsevier Science, 2003.

- Horton, P.; Ruban, A.V.; Walters, R.G. REGULATION OF LIGHT HARVESTING IN GREEN PLANTS. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1996, 47, 655–684. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, D.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y. The vertical microdistribution of cyanobacteria and green algae within desert crusts and the development of the algal crusts. Plant Soil 2003, 257, 97–111. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Liu, Y., Paulsen, B. S. and Klaveness, D.: Studies on Polysaccharides from Three Edible Species of Nostoc (Cyanobacteria) with Different Colony Morphologies: Comparison of.

- 82. Monosaccharide Compositions and Viscosities of Polysaccharides from Field Colonies and.

- Suspension Cultures, J. Phycol., 34, 962–968, 1998.

- Hunsucker, S.W.; Tissue, B.M.; Potts, M.; Helm, R.F. Screening Protocol for the Ultraviolet-Photoprotective Pigment Scytonemin. Anal. Biochem. 2001, 288, 227–230. [CrossRef]

- Ingalls, A.E.; Whitehead, K.; Bridoux, M.C. Tinted windows: The presence of the UV absorbing compounds called mycosporine-like amino acids embedded in the frustules of marine diatoms. Geochim. et Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 104–115. [CrossRef]

- Ito, S. and Hirata, Y.: Isolation and structure of a mycosporine from the zoanthidian Palythoa tuberculosa, Tetrahedron Lett., 28, 2429–2430, 1977.

- Jain, S.; Prajapat, G.; Abrar, M.; Ledwani, L.; Singh, A.; Agrawal, A. Cyanobacteria as efficient producers of mycosporine-like amino acids. J. Basic Microbiol. 2017, 57, 715–727. [CrossRef]

- Jones, I.; George, G.; Reynolds, C. Quantifying effects of phytoplankton on the heat budgets of two large limnetic enclosures. Freshw. Biol. 2005, 50, 1239–1247. [CrossRef]

- Kahru, M.; Leppanen, J.-M.; Rud, O. Cyanobacterial blooms cause heating of the sea surface. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1993, 101, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Karentz, D.: Ultraviolet tolerance mechanisms in Antarctic marine organisms, Antarctic Research Series, 62, 93-110, 1994.

- Karentz, D.: Chemical defenses of marine organisms against solar radiation exposure: UV absorbing mycosporine-like amino acids and scytonemin. In: McClintock, J. B. and Baker, B. J. (eds.) Marine chemical ecology, CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp 481-519, 2001.

- Karentz, D.; Spero, H.J. Response of a natural Phaeocysris population to ambient fluctuations of UVB radiation caused by Antarctic ozone depletion. J. Plankton Res. 1995, 17, 1771–1789. [CrossRef]

- Karsten, U.: Defense strategies of algae and cyanobacteria against solar ultraviolet radiation. In: Amsler, C. D. (ed.), Algal Chemical Ecology, Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg, 2008.

- Karsten, U.; Dummermuth, A.; Hoyer, K.; Wiencke, C. Interactive effects of ultraviolet radiation and salinity on the ecophysiology of two Arctic red algae from shallow waters. Polar Biol. 2003, 26, 249–258. [CrossRef]

- Karsten, U., Lembcke, S. and Schumann, R: The effect of ultraviolet radiation on photosynthetic performance, growth and sunscreen compound in aeroterrestrial biofilm algae isolated from building facades, Planta, 225, 991–1000, 2007.

- Karsten, U.; Maier, J.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Seasonality in UV-absorbing compounds of cyanobacterial mat communities from an intertidal mangrove flat. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 1998, 16, 37–44. [CrossRef]

- Karunakaran, E., Mukherjee, J., Ramalingam, B. and Biggs, C. A.: “Biofilmology”: a multidisciplinary review of the study of microbial biofilms, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., 90, 1869-1881, 2011.

- Kehr, J.-C.; Dittmann, E. Biosynthesis and Function of Extracellular Glycans in Cyanobacteria. Life 2015, 5, 164–180. [CrossRef]

- A Keller, M.; Turchyn, A.V.; Ralser, M. Non-enzymatic glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway-like reactions in a plausible Archean ocean. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2014, 10, 725. [CrossRef]

- Kinzie, R.A. Effects of ambient levels of solar ultraviolet radiation on zooxanthellae and photosynthesis of the reef coral Montipora verrucosa. Mar. Biol. 1993, 116, 319–327. [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, A.R. The biosynthesis of shikimate metabolites. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2002, 20, 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kajiyama, S.-I.; Inawaka, K.; Kanzaki, H.; Kawazu, K. Nostodione A, a Novel Mitotic Spindle Poison from a Blue-Green Alga Nostoc commune. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. C-A J. Biosci. 1994, 49, 464–470. [CrossRef]

- Korbee, N., Figueroa, F. L. and Aguilera, J.: Accumulation of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs): biosynthesis, photocontrol and ecophysiological functions, Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 79, 119–132, 2006.

- Krissansen-Totton, J.; Arney, G.N.; Catling, D.C. Constraining the climate and ocean pH of the early Earth with a geological carbon cycle model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018, 115, 4105–4110. [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Elliott, D.R.; Chamizo, S.; Felde, V.J.M.N.L.; Thomas, A.D.; Lan, \. Editorial: Biological soil crusts: spatio-temporal development and ecological functions of soil surface microbial communities across different scales. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1447058. [CrossRef]

- Lara, Y.J.; McCann, A.; Malherbe, C.; François, C.; Demoulin, C.F.; Sforna, M.C.; Eppe, G.; De Pauw, E.; Wilmotte, A.; Jacques, P.; et al. Characterization of the Halochromic Gloeocapsin Pigment, a Cyanobacterial Biosignature for Paleobiology and Astrobiology. Astrobiology 2022, 22, 735–754. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, K.P.; Long, P.F.; Young, A.R. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids for Skin Photoprotection. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 25, 5512–5527. [CrossRef]

- Leach, C.M. ULTRAVIOLET-ABSORBING SUBSTANCES ASSOCIATED WITH LIGHT-INDUCED SPORULATION IN FUNGI. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 185–200. [CrossRef]

- Lepot, K., Deremiens, L., Namsaraev, Z., Compère, P., Gérard, E., Verleyen, E., Tavernier, I., Hodgson, D. A., Wilmotte, A., and Javaux, E. J.: Organo-mineral imprints in fossil cyanobacterial mats of an Antarctic lake, Geobiology, 12, 424–450, 2014.

- Lesser, M. Acclimation of phytoplankton to UV-B radiation:oxidative stress and photoinhibition of photosynthesis are not prevented by UV-absorbing compounds in the dinoflagellate Prorocentrum micans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1996, 132, 287–297. [CrossRef]

- Lifshits, M.; Kovalerchik, D.; Carmeli, S. Microcystbiopterins A–E, five O-methylated biopterin glycosides from two Microcystis spp. bloom biomasses. Phytochemistry 2016, 123, 69–74. [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, C.A.; Greig, C.; Silkina, A.; Kultschar, B.; Hitchings, M.D.; Farnham, G. Mycosporine-like amino acid and aromatic amino acid transcriptome response to UV and far-red light in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis fritschii PCC 6912. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Logozzo, L.; Tzortziou, M.; Neale, P.; Clark, J.B. Photochemical and Microbial Degradation of Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter Exported From Tidal Marshes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosciences 2021, 126. [CrossRef]

- Losantos, R.; Churio, M.S.; Sampedro, D. Computational Exploration of the Photoprotective Potential of Gadusol. ChemistryOpen 2015, 4, 155–160. [CrossRef]

- Losantos, R., Sampedro, D. and Churio, M. S.: Photochemistry and photophysics of mycosporine-like amino acids and gadusols, nature’s ultraviolet screens, Pure Appl. Chem., 87(9-10), 979–996, 2015b.

- Maes, W.; Pashuysen, T.; Trabucco, A.; Veroustraete, F.; Muys, B. Does energy dissipation increase with ecosystem succession? Testing the ecosystem exergy theory combining theoretical simulations and thermal remote sensing observations. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 3917–3941. [CrossRef]

- Mager, D. M. and Thomas, A. D.: Carbohydrates in cyanobacterial soil crusts as a source of carbon in the southwest Kalahari, Botswana, Soil Biol. Biochem., 42, 313–318, 2010.

- Mahmud, T.; Moore, D.C.; Dergachev, I.D.; Sun, H.; Varganov, S.A.; Tucker, M.J.; Jeffrey, C.S. Cortical polysaccharides play a crucial role in lichen UV protection. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Majerfeld, I. and Yarus, M.: A diminutive and specific RNA binding site for L-tryptophan, Nucleic Acids Res., 33, 5482–5493, 2005.

- Matsui, K.; Nazifi, E.; Hirai, Y.; Wada, N.; Matsugo, S.; Sakamoto, T. The cyanobacterial UV-absorbing pigment scytonemin displays radical-scavenging activity. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 137–144. [CrossRef]

- Matsumi, Y.; Kawasaki, M. Photolysis of Atmospheric Ozone in the Ultraviolet Region. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 4767–4782. [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, T.; Burgess, J.G.; Yamada, N.; Komatsu, K.; Yoshida, S.; Wachi, Y. An ultraviolet (UV-A) absorbing biopterin glucoside from the marine planktonic cyanobacterium Oscillatoria sp.. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 39, 250–253. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.: Thermodynamic origin of life. https://arxiv.org/abs/0907.0042 (last access: 25 July 2015), 2009.

- Michaelian, K. Thermodynamic dissipation theory for the origin of life. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2011, 2, 37–51. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. HESS Opinions "Biological catalysis of the hydrological cycle: life's thermodynamic function". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 2629–2645. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. A non-linear irreversible thermodynamic perspective on organic pigment proliferation and biological evolution.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 012010.

- Michaelian, K.: Thermodynamic Dissipation Theory of the Origin and Evolution of Life: Salient characteristics of RNA and DNA and other fundamental molecules suggest an origin of life driven by UV-C light, Self-published. Printed by CreateSpace, Mexico City, ISBN: 978-1541317482, 2016.

- Michaelian, K. Microscopic dissipative structuring and proliferation at the origin of life. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00424. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.; Simeonov, A. Fundamental molecules of life are pigments which arose and co-evolved as a response to the thermodynamic imperative of dissipating the prevailing solar spectrum. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 4913–4937. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K., Simeonov, A.: Thermodynamic Explanation for the Cosmic Ubiquity of.

- Organic Pigments. Astrobiol Outreach (2017) 5:156. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Dissipative Photochemical Origin of Life: UVC Abiogenesis of Adenine. Entropy 2021, 23, 217. [CrossRef]

- 2021; 133. Entropy 2021, 23(2), 217, ISSN 1099-4300. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K.: The Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Natural Selection: From Molecules.

- Michaelian, K. The Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics of Natural Selection: From Molecules to the Biosphere. Entropy 2023, 25, 1059. [CrossRef]

- Michaelian, K. The Pigment World: Life’s Origins as Photon-Dissipating Pigments. Life 2024, 14, 912. [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, K.T.; Komatsu, M.; Ikeda, H. Discovery of Gene Cluster for Mycosporine-Like Amino Acid Biosynthesis from Actinomycetales Microorganisms and Production of a Novel Mycosporine-Like Amino Acid by Heterologous Expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 5028–5036. [CrossRef]

- Moisan, T.A.; Mitchell, B.G. UV absorption by mycosporine-like amino acids in Phaeocystis antarctica Karsten induced by photosynthetically available radiation. Mar. Biol. 2001, 138, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Moliné, M., Libkind, D., de Garcia, V. and Giraudo, M. R.: Production of Pigments and Photo-Protective Compounds by Cold-Adapted Yeasts, In: Buzzini, P. and Margesin, R. (eds.) Cold-adapted Yeasts: Biodiversity, Adaptation Strategies and Biotechnological Significance, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp 193-224, 2014.

- Morel, A. Optical modeling of the upper ocean in relation to its biogenous matter content (case I waters). J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1988, 93, 10749–10768. [CrossRef]

- Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; Junge, W. On the origin of photosynthesis as inferred from sequence analysis. Photosynth. Res. 1997, 51, 27–42. [CrossRef]

- Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; A Cherepanov, D.; Galperin, M.Y. Survival of the fittest before the beginning of life: selection of the first oligonucleotide-like polymers by UV light. BMC Evol. Biol. 2003, 3, 12–12. [CrossRef]

- Murchie, E. H., & Ruban, A. V. (2020). Non-photochemical quenching in plants: From molecular mechanisms to crop improvement. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 71, 739–766. [CrossRef]

- Nägeli, C. Gattungen einzelliger Algen physiologisch und systematisch bearbeitet, von Carl Nägeli.; Smithsonian Institution: Washington, DC, United States, 1849; ISBN: .

- Nägeli, C. and Schwenderer, S.: Das Mikroskop, 2nd edn. Willhelm Engelmann Verlag, Leipzig, 505 p., 1877.

- Nelson, N.B.; Siegel, D.A. The Global Distribution and Dynamics of Chromophoric Dissolved Organic Matter. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2013, 5, 447–476. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, N.; Siegel, D.; Michaels, A. Seasonal dynamics of colored dissolved material in the Sargasso Sea. Deep. Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 1998, 45, 931–957. [CrossRef]

- Olivucci, M. (Ed.): Computational Photochemistry, Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005.

- Orellana, G.; Gómez-Silva, B.; Urrutia, M.; Galetović, A. UV-A Irradiation Increases Scytonemin Biosynthesis in Cyanobacteria Inhabiting Halites at Salar Grande, Atacama Desert. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1690. [CrossRef]

- Oren, A. and Gunde-Cimerman, N.: Mycosporines and mycosporinelike amino acids: UV protectants or multipurpose secondary metabolites? FEMS Microbiol Lett, 269, 1–10, 2007.

- Organelli, E.; Bricaud, A.; Antoine, D.; Matsuoka, A. Seasonal dynamics of light absorption by chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) in the NW Mediterranean Sea (BOUSSOLE site). Deep. Sea Res. Part I: Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2014, 91, 72–85. [CrossRef]

- Patara, L.; Vichi, M.; Masina, S.; Fogli, P.G.; Manzini, E. Global response to solar radiation absorbed by phytoplankton in a coupled climate model. Clim. Dyn. 2012, 39, 1951–1968. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, J., Rajneesh, Richa, Sonker, A.S., Kannaujiya, V. K. and Sinha, R. P.: Cyanobacterial extracellular polysaccharide sheath pigment, scytonemin: A novel multipurpose pharmacophore, In: Se-Kwon, K. (ed.) Marine Glycobiology: Principles and Applications, 1st edition, Taylor & Francis Group, 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300, Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 CRC Press, Pages 323–337, 2016.

- Pereira, S.; Zille, A.; Micheletti, E.; Moradas-Ferreira, P.; De Philippis, R.; Tamagnini, P. Complexity of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides: composition, structures, inducing factors and putative genes involved in their biosynthesis and assembly. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 33, 917–941. [CrossRef]

- putative genes involved in their biosynthesis and assembly. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 917–941, 2009.

- Ploutno, A. and Carmeli, S.: Prenostodione, a novel UV-absorbing metabolite from a natural bloom of the cyanobacterium Nostoc species, J Nat Prod, 64, 544-545, 2001.

- Pokorny, J.; Brom, J.; Cermak, J.; Hesslerova, P.; Huryna, H.; Nadezhdina, N.; Rejskova, A. Solar energy dissipation and temperature control by water and plants. Int. J. Water 2010, 5, 311. [CrossRef]

- Pope, M.A.; Spence, E.; Seralvo, V.; Gacesa, R.; Heidelberger, S.; Weston, A.J.; Dunlap, W.C.; Shick, J.M.; Long, P.F. O-Methyltransferase Is Shared between the Pentose Phosphate and Shikimate Pathways and Is Essential for Mycosporine-Like Amino Acid Biosynthesis in Anabaena variabilis ATCC 29413. ChemBioChem 2014, 16, 320–327. [CrossRef]

- Portwich, A. and Garcia-Pichel, F.: A novel prokaryotic UVB photoreceptor in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis PCC 6912, Photochem Photobiol, 71, 493–498, 2000.

- Portwich, A.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Biosynthetic pathway of mycosporines (mycosporine-like amino acids) in the cyanobacterium Chlorogloeopsis sp. strain PCC 6912. Phycologia 2003, 42, 384–392. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I.: Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes, Wiley, New York, 1967.

- Proteau, P.J.; Gerwick, W.H.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Castenholz, R. The structure of scytonemin, an ultraviolet sunscreen pigment from the sheaths of cyanobacteria. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1993, 49, 825–829. [CrossRef]

- Pullan, D.; Westall, F.; Hofmann, B.A.; Parnell, J.; Cockell, C.S.; Edwards, H.G.; Villar, S.E.J.; Schröder, C.; Cressey, G.; Marinangeli, L.; et al. Identification of Morphological Biosignatures in Martian Analogue Field Specimens Using In Situ Planetary Instrumentation. Astrobiology 2008, 8, 119–156. [CrossRef]

- Quesada, A. and Vincent, W. F.: Strategies of adaptation by Antarctic cyanobacteria to ultraviolet radiation, Eur J Phycol, 32, 335–342, 1997.

- Rastogi, R. P. and Incharoensakdi, A.: Characterization of UV-screening compounds, mycosporine-like amino acids, and scytonemin in the cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. CU2555, FEMS Microbiol Ecol., 87(1), 244-256, 2014.

- Rastogi, R. P. and Madamwar, D.: Cyanobacteria Synthesize their own UV-Sunscreens for Photoprotection, Bioenergetics, 5, 138, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R. P., Richa, S. R. P., Singh, S. P. and Häder, D. P.: Photoprotective compounds from marine organisms, J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 37, 537–558, 2010.

- Rastogi, R. P., Sinha, R. P., Moh, S. H., Lee, T. K., Kottuparambil, S., Kim, Y. J., Rhee, J. S., Choi, E. M., Brown, M. T., Häder, D. P. and Han, T.: Ultraviolet radiation and cyanobacteria, Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology, 141, 154–169, 2014.

- Rastogi, R.P.; Sinha, R.P.; Incharoensakdi, A. Partial characterization, UV-induction and photoprotective function of sunscreen pigment, scytonemin from Rivularia sp. HKAR-4. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1874–1878. [CrossRef]

- Řezanka, T.; Temina, M.; Tolstikov, A.G.; Dembitsky, V.M. Natural microbial UV radiation filters — Mycosporine-like amino acids. Folia Microbiol. 2004, 49, 339–352. [CrossRef]

- Richards, T. A., Dacks, J. B., Campbell, S. A., Blanchard, J. L., Foster, P. G., McLeod, R. and Roberts, C. W.: Evolutionary origins of the eukaryotic shikimate pathway: gene fusions, horizontal gene transfer, and endosymbiotic replacements, Eukaryot Cell, 5(9), 1517-1531, 2006.

- Roeselers, G.; Norris, T.B.; Castenholz, R.W.; Rysgaard, S.; Glud, R.N.; Kühl, M.; Muyzer, G. Diversity of phototrophic bacteria in microbial mats from Arctic hot springs (Greenland). Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 26–38. [CrossRef]

- Romera-Castillo, C., Sarmento, H., Álvarez-Salgado, X. A., Gasol, J. M. and Marrasé, C.: Production of chromophoric dissolved organic matter by marine phyto-plankton, Limnol.Oceanogr., 55(1), 446–454, 2010.

- Rosic, N.N. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids: Making the Foundation for Organic Personalised Sunscreens. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 638. [CrossRef]

- Rosic, N.N. Recent advances in the discovery of novel marine natural products and mycosporine-like amino acid UV-absorbing compounds. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 7053–7067. [CrossRef]

- Rosic, N.N.; Dove, S. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids from Coral Dinoflagellates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8478–8486. [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F. and De Philippis, R.: Role of Cyanobacterial Exopolysaccharides in Phototrophic Biofilms and in Complex Microbial Mats, Life (Basel), 5(2), 1218–1238, 2015.

- Rossi, F.; Potrafka, R.M.; Pichel, F.G.; De Philippis, R. The role of the exopolysaccharides in enhancing hydraulic conductivity of biological soil crusts. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Röttgers, R.; Koch, B.P. Spectroscopic detection of a ubiquitous dissolved pigment degradation product in subsurface waters of the global ocean. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 2585–2596. [CrossRef]

- Rowan, K. S.: Photosynthetic Pigments of Algae, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 112–210, 1989.

- Rozema, J.; Björn, L.; Bornman, J.; Gaberščik, A.; Häder, D.-P.; Trošt, T.; Germ, M.; Klisch, M.; Gröniger, A.; Sinha, R.; et al. The role of UV-B radiation in aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems—an experimental and functional analysis of the evolution of UV-absorbing compounds. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2002, 66, 2–12. [CrossRef]

- Ruban, A.V.; Berera, R.; Ilioaia, C.; Van Stokkum, I.H.M.; Kennis, J.T.M.; Pascal, A.; van Amerongen, H.; Robert, B.; Horton, P.; Van Grondelle, R. Identification of a mechanism of photoprotective energy dissipation in higher plants. Nature 2007, 450, 575–578. [CrossRef]

- Ručová, D.; Vilková, M.; Sovová, S.; Vargová, Z.; Kostecká, Z.; Frenák, R.; Routray, D.; Bačkor, M. Photoprotective and antioxidant properties of scytonemin isolated from Antarctic cyanobacterium Nostoc commune Vaucher ex Bornet & Flahault and its potential as sunscreen ingredient. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2839–2850. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, K.G.; McMinn, A.; Mitchell, K.A.; Trenerry, L. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids in Antarctic Sea Ice Algae, and Their Response to UVB Radiation. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. C-A J. Biosci. 2002, 57, 471–477. [CrossRef]

- Sagan, C. Ultraviolet selection pressure on the earliest organisms. J. Theor. Biol. 1973, 39, 195–200. [CrossRef]

- Sampedro, D. Computational exploration of natural sunscreens. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 5584–5586. [CrossRef]

- Schermann, J.-P. Spectroscopy and Modeling of Biomolecular Building Blocks; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NX, Netherlands, 2008; ISBN: .

- Schmid, D., Schürch, C. and Zülli, F.: UV-A sunscreen from red algae for protection against premature skin aging, Cosmet. Toilet. Manuf. Worldw., 115, 139–143, 2000.

- Schopf, J.W. Microfossils of the Early Archean Apex Chert: New Evidence of the Antiquity of Life. Science 1993, 260, 640–646. [CrossRef]

- Schopf, J.W.; Packer, B.M. Early Archean (3.3-Billion to 3.5-Billion-Year-Old) Microfossils from Warrawoona Group, Australia. Science 1987, 237, 70–73. [CrossRef]

- Schopf, J.W.; Kudryavtsev, A.B.; Agresti, D.G.; Wdowiak, T.J.; Czaja, A.D. Laser–Raman imagery of Earth's earliest fossils. Nature 2002, 416, 73–76. [CrossRef]

- Shick, J. M. and Dunlap, W. C.: Mycosporine-like amino acids and related gadusols: biosynthesis, accumulation, and UV protective functions in aquatic organisms, Annu Rev Plant.

- Physiol., 64, 223–262, 2002.

- Shick, J.M.; Romaine-Lioud, S.; Ferrier-Pagès, C.; Gattuso, J.-P. Ultraviolet-B radiation stimulates shikimate pathway-dependent accumulation of mycosporine-like amino acids in the coral Stylophora pistillata despite decreases in its population of symbiotic dinoflagellates. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999, 44, 1667–1682. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, D.A.; Maritorena, S.; Nelson, N.B.; Hansell, D.A.; Lorenzi-Kayser, M. Global distribution and dynamics of colored dissolved and detrital organic materials. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2002, 107, 21-1–21-14. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Häder, D.-P.; Sinha, R.P. Bioinformatics evidence for the transfer of mycosporine-like amino acid core (4-deoxygadusol) synthesizing gene from cyanobacteria to dinoflagellates and an attempt to mutate the same gene (YP_324358) in Anabaena variabilis PCC 7937. Gene 2012, 500, 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Klisch, M.; Sinha, R.P.; Häder, D.-P. Genome mining of mycosporine-like amino acid (MAA) synthesizing and non-synthesizing cyanobacteria: A bioinformatics study. Genomics 2009, 95, 120–128. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Čížková, M.; Bišová, K.; Vítová, M. Exploring Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs) as Safe and Natural Protective Agents against UV-Induced Skin Damage. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 683. [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Jha, S.; Rana, P.; Mishra, S.; Kumari, N.; Singh, S.C.; Anand, S.; Upadhye, V.; Sinha, R.P. Resilience and Mitigation Strategies of Cyanobacteria under Ultraviolet Radiation Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12381. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. P. and Häder, D. P.: UV-protectants in cyanobacteria, Plant Sci., 174, 278–289, 2008.

- Sinha, R.P.; Klisch, M.; Helbling, E.W.; Häder, D.-P. Induction of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in cyanobacteria by solar ultraviolet-B radiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2001, 60, 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R. P., Klisch, M., Vaishampayan, A. and Häder, D. P.: Biochemical and spectroscopic characterization of the cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp. Inhabiting Mango (Mangifera indica) trees: presence of an ultraviolet-absorbing pigment, scytonemin, Acta Protozool, 38, 291–298, 1999.

- Sinha, R. P., Singh, S. P. and Häder, D. P.: Database on mycosporines and mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) in fungi, cyanobacteria, macroalgae, phytoplankton and animals, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, 89, 29–35, 2007.

- Sinha, R.P.; Klisch, M.; Gröniger, A.; Häder, D.-P. Mycosporine-like amino acids in the marine red alga Gracilaria cornea — effects of UV and heat. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2000, 43, 33–43. [CrossRef]

- Son, M.; Pinnola, A.; Gordon, S.C.; Bassi, R.; Schlau-Cohen, G.S. Observation of dissipative chlorophyll-to-carotenoid energy transfer in light-harvesting complex II in membrane nanodiscs. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Soppa, M.A.; Pefanis, V.; Hellmann, S.; Losa, S.N.; Hölemann, J.; Martynov, F.; Heim, B.; Janout, M.A.; Dinter, T.; Rozanov, V.; et al. Assessing the Influence of Water Constituents on the Radiative Heating of Laptev Sea Shelf Waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Sorrels, C.M.; Proteau, P.J.; Gerwick, W.H. Organization, Evolution, and Expression Analysis of the Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for Scytonemin, a Cyanobacterial UV-Absorbing Pigment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4861–4869. [CrossRef]

- Soule, T.; Garcia-Pichel, F.; Stout, V. Gene Expression Patterns Associated with the Biosynthesis of the Sunscreen Scytonemin in Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133 in Response to UVA Radiation. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4639–4646. [CrossRef]

- Soule, T.; Palmer, K.; Gao, Q.; Potrafka, R.M.; Stout, V.; Garcia-Pichel, F. A comparative genomics approach to understanding the biosynthesis of the sunscreen scytonemin in cyanobacteria. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 336–336. [CrossRef]

- Soule, T.; Stout, V.; Swingley, W.D.; Meeks, J.C.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Molecular Genetics and Genomic Analysis of Scytonemin Biosynthesis in Nostoc punctiforme ATCC 29133. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 4465–4472. [CrossRef]

- Staleva, H.; Komenda, J.; Shukla, M.K.; Šlouf, V.; Kaňa, R.; Polívka, T.; Sobotka, R. Mechanism of photoprotection in the cyanobacterial ancestor of plant antenna proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015, 11, 287–291. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, S. M.: Earth System History, 3rd edn., W. H. Freeman and Company, New York, NY, 263–287, 2008.

- Starcevic, A., Akthar, S., Dunlap, W. C., Shick, J. M., Hranueli, D., Cullum, J. and Long, P. F.: Enzymes of the shikimic acid pathway encoded in the genome of a basal metazoan, Nematostella vectensis, have microbial origins, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 105, 2533–2537, 2008.

- Steinberg, D.K.; Nelson, N.B.; Carlson, C.A.; Prusak, A. Production of chromophoric dissolved organic matter (CDOM) in the open ocean by zooplankton and the colonial cyanobacterium Trichodesmium spp.. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 267, 45–56. [CrossRef]

- Storme, J.-Y.; Golubic, S.; Wilmotte, A.; Kleinteich, J.; Velázquez, D.; Javaux, E.J. Raman Characterization of the UV-Protective Pigment Gloeocapsin and Its Role in the Survival of Cyanobacteria. Astrobiology 2015, 15, 843–857. [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, A., Carpenter, E. J., Karentz, D. and Falkowski, P. G.: Bio-optical properties of the marine diazotrophic cyanobacteria Trichodesmium spp. I. Absorption and photosynthetic action spectra, Limnol Oceanogr, 44, 608–617, 1999.

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, J.; Dong, S.; Zhang, X.; Guo, L.; Guo, G. Distribution, Contents, and Types of Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids (MAAs) in Marine Macroalgae and a Database for MAAs Based on These Characteristics. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 43. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Li, X.-Y.; Wang, D.-D.; Wang, Y.-M.; Xue, C.-H.; Wen, M.; Zhang, T.-T. Supplementation of n-3 PUFAs in Adulthood Attenuated Susceptibility to Pentylenetetrazol Induced Epilepsy in Mice Fed with n-3 PUFAs Deficient Diet in Early Life. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21, 354. [CrossRef]

- Tamre, E.; Fournier, G.P. Inferred ancestry of scytonemin biosynthesis proteins in cyanobacteria indicates a response to Paleoproterozoic oxygenation. Geobiology 2022, 20, 764–775. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Li, Z.; Chen, N.; Luo, X.; Zhao, Q. Natural pigments derived from plants and microorganisms: classification, biosynthesis, and applications. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 23, 592–614. [CrossRef]

- Tice, M. M and Lowe, D. R.: Photosynthetic microbial mats in the 3,416-Myr-old ocean, Nature, 431(7008), 549–552, 2004.

- Tilstone, G.H.; Airs, R.L.; Vicente, V.M.; Widdicombe, C.; Llewellyn, C. High concentrations of mycosporine-like amino acids and colored dissolved organic matter in the sea surface microlayer off the Iberian Peninsula. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2010, 55, 1835–1850. [CrossRef]

- Trione, E.J.; Leach, C.M. Light-induced sporulation and sporogenic substances in fungi.. 1969, 59, 1077–83.

- Uemura, D.; Katayama, C.; Wada, A.; Hirata, Y. CRYSTAL AND MOLECULAR STRUCTURE OF PALYTHENE POSSESSING A NOVEL 360 NM CHROMOPHORE. Chem. Lett. 1980, 9, 755–756. [CrossRef]

- Ustin, S.L.; Valko, P.G.; Kefauver, S.C.; Santos, M.J.; Zimpfer, J.F.; Smith, S.D. Remote sensing of biological soil crust under simulated climate change manipulations in the Mojave Desert. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2008, 113, 317–328. [CrossRef]

- Van Kranendonk, M. J., Philippot, P., Lepot, K., Bodorkos, S. and Pirajno, F.: Geological setting of Earth’s oldest fossils in the c. 3.5 Ga Dresser Formation, Pilbara craton, Western Australia, Precambr. Res., 167, 93–124, 2008.

- Varnali, T.; Edwards, H.G.M. Ab initio calculations of scytonemin derivatives of relevance to extremophile characterization by Raman spectroscopy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 368, 3193–3203. [CrossRef]

- Varnali, T.; Edwards, H.G.M. Raman spectroscopic identification of scytonemin and its derivatives as key biomarkers in stressed environments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2014, 372, 20140197. [CrossRef]

- Vernet, M.; Whitehead, K. Release of ultraviolet-absorbing compounds by the red-tide dinoflagellateLingulodinium polyedra. Mar. Biol. 1996, 127, 35–44. [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsugo, S. Mycosporine-Like Amino Acids and Their Derivatives as Natural Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2015, 4, 603–646. [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.F.; Slamovits, C.H.; Keeling, P.J. Lateral Gene Transfer of a Multigene Region from Cyanobacteria to Dinoflagellates Resulting in a Novel Plastid-Targeted Fusion Protein. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006, 23, 1437–1443. [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.R.; Buick, R.; Dunlop, J.S.R. Stromatolites 3,400–3,500 Myr old from the North Pole area, Western Australia. Nature 1980, 284, 443–445. [CrossRef]

- Wellman, C. H., Strother, P. K., & Servais, T. (2021). The terrestrialization process: A palaeobotanical and palynological perspective. *Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences*, 49, 423–451. [CrossRef]

- Westall, F. Life on an Anaerobic Planet. Science 2009, 323, 471–472. [CrossRef]

- Westall, F., de Ronde, C. E. J., Southam, G., Grassineau, N., Colas, M., Cockell, C. and Lammer, H.: Implications of a 3.472-3.333 Gyr-old subaerial microbial mat from the Barberton greenstone belt, South Africa for the UV environmental conditions on the early Earth, Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society B, 361, 1857-1875, 2006.

- Whitehead, K.; Vernet, M. Influence of mycosporine-like amino acids (MAAs) on UV absorption by particulate and dissolved organic matter in La Jolla Bay. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2000, 45, 1788–1796. [CrossRef]

- Wurl, O.; Bird, K.; Cunliffe, M.; Landing, W.M.; Miller, U.; Mustaffa, N.I.H.; Ribas-Ribas, M.; Witte, C.; Zappa, C.J. Warming and Inhibition of Salinization at the Ocean's Surface by Cyanobacteria. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 4230–4237. [CrossRef]

- Wurfel, P.; Ruppel, W. The flow equilibrium of a body in a radiation field. J. Phys. C: Solid State Phys. 1985, 18, 2987–3000. [CrossRef]

- Wynn-Williams, D. D., Edwards, H. G. M. and Garcia-Pichel, F.: Functional biomolecules of Antarctic stromatolitic and endolithic cyanobacterial communities, Eur. J. Phycol., 34, 381–391, 1999.

- Wynn-Williams, D.; Edwards, H.; Newton, E.; Holder, J. Pigmentation as a survival strategy for ancient and modern photosynthetic microbes under high ultraviolet stress on planetary surfaces. Int. J. Astrobiol. 2002, 1, 39–49. [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, Y.; Tanoue, E. Chemical characterization of protein-like fluorophores in DOM in relation to aromatic amino acids. Mar. Chem. 2003, 82, 255–271. [CrossRef]

- Yarus, M.; Widmann, J.J.; Knight, R. RNA–Amino Acid Binding: A Stereochemical Era for the Genetic Code. J. Mol. Evol. 2009, 69, 406–429. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, P.; Peng, C. Pigment patterns and photoprotection of anthocyanins in the young leaves of four dominant subtropical forest tree species in two successional stages under contrasting light conditions. Tree Physiol. 2016, 36, 1092–1104. [CrossRef]

- Zwerger, M.J.; Hammerle, F.; Siewert, B.; Ganzera, M. Application of feature-based molecular networking in the field of algal research with special focus on mycosporine-like amino acids. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 1377–1392. [CrossRef]

| UV bio-pigments | (nm) | (M-1cm-1) | Electronic excited state lifetime (ns) | Fluorescence quantum yield () |

| Aromatic amino acids | ||||

| Phenylalaninea | 257 | 195 | 7.5 | 0.024 |

| Tyrosinea | 274 | 1405 | 2.5 | 0.14 |

| Tryptophana | 278 | 5579 | 3.03 | 0.13 |

| Mycosporines and MAAs | ||||

| Gadusolb | 269 | 12400 | / | non-fluorescent |

| Mycosporine-γ-aminobutyric acidc | 310 | 28900 | / | / |

| Mycosporine-glutamic acidc | 311 | 20900 | / | / |

| Palythineb, c | 320 | 36200 | / | non-fluorescent |

| Shinorineb | 333 | 44700 | 0.35 | 0.002 |

| Porphyra-334b | 334 | 42300 | 0.4 | 0.0016 |

| Palythenec | 360 | 50000 | / | / |

| Scytonemins | ||||

|

Scytonemind, e |

212, 252, 278, 300, 384 |

/ / / / 16200 |

/ |

non-fluorescent |

|

Reduced Scytonemind |

246, 276, 314, 378, 474, 572 |

30000, 14000, 15000, 22000, 14000, 7600 |

/ | / |

|

Scytonemin-iminef |

237, 366, 437, 564 |

/ / / / |

/ | / |

| Dimethoxyscytonemind | 215, 316, 422 |

60354 18143, 23015 |

/ | / |

| Tetramethoxyscytonemind | 212, 562 |

35928 5944 |

/ | / |

| Scytonined | 207, 225, 270 |

38948 37054, 22484 |

/ | / |

| Other poorly characterized cyanobacterial UV-absorbing pigments | ||||

| Gloeocapsing | 392 | / | / | / |

| Microcystbiopterinsh | ~ 275, ~ 350 |

10000, 3500 |

/ | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).