1. Introduction

Casein, the major milk protein in bovine milk, and whey proteins are sustainable, biobased materials for gel systems. These milk-based protein systems are widely used in food and biotechnology applications due to their high functionality, storage stability, and versatility, such as in beverages, fermented dairy products, and protein-enriched formulations. They also have potential as drug carriers in tissue engineering, wound healing, and diagnostics as biosensors, offering mechanical strength, stability, biocompatibility, and conductivity [

1,

2]. Their structured gel networks are key to tailoring texture and rheology, with structural modifications crucially affecting the swelling of micellar casein-based fibers and microparticles in applications like encapsulation or tissue scaffolds [

3,

4,

5].

The acid-induced gelation of milk proteins is a complex process influenced by heat, pH, protein composition, and both covalent and non-covalent interactions. Particularly, the interactions between casein micelles and thermally denatured whey proteins, such as β-lactoglobulin (β-Lg), largely determine gel structure and strength. These interactions occur through thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, forming stable, three-dimensional networks [

6,

7,

8].

In bovine milk, about 95% of casein is found as unstructured aggregates called casein micelles. These micelles consist of α

S1-, α

S2-, β-, and κ-casein as well as colloidal calcium phosphate. They vary in size between 80–400 nm and hold approximately 3.3 g of water per gram of protein [

9]. In their native state, κ-casein forms a stabilizing "hairy" surface layer that protects the micelles [

10,

11]. If this stabilizing effect is lost due to acidification or rennet enzymes, the micelles precipitate and aggregate, forming submicron-sized aggregates that, once a critical size is reached, form a coherent gel, as demonstrated by single-particle tracking via fluorescence microscopy [

12]. The gel structure links particles like a string of pearls, separated by water-filled cavities.

Before acidification, milk proteins are often heated above 70°C, causing whey proteins to denature and interact with casein micelles, particularly through hydrophobic interactions and covalent disulfide bonds involving κ-casein [

13,

14]. High-temperature treatment leads to high-molecular-weight complexes between denatured whey proteins and κ-casein, which remain partly associated with casein micelles [

15]. Subsequently, acidification occurs, causing caseins to precipitate and form a gel matrix. Disulfide bridges and free thiol groups are crucial in this process, determining gel strength [

16,

17]. β-Lactoglobulin is the main source of thiol groups in milk. In cow's milk serum, β-lactoglobulin is present at 3.5–5 g/L, and its structure consists of two β-sheets stabilized by disulfide bridges (Cys66–Cys160; Cys106–Cys119). A free thiol group (Cys121) inside the structure becomes exposed after thermal unfolding, making it reactive [

18,

19,

20].

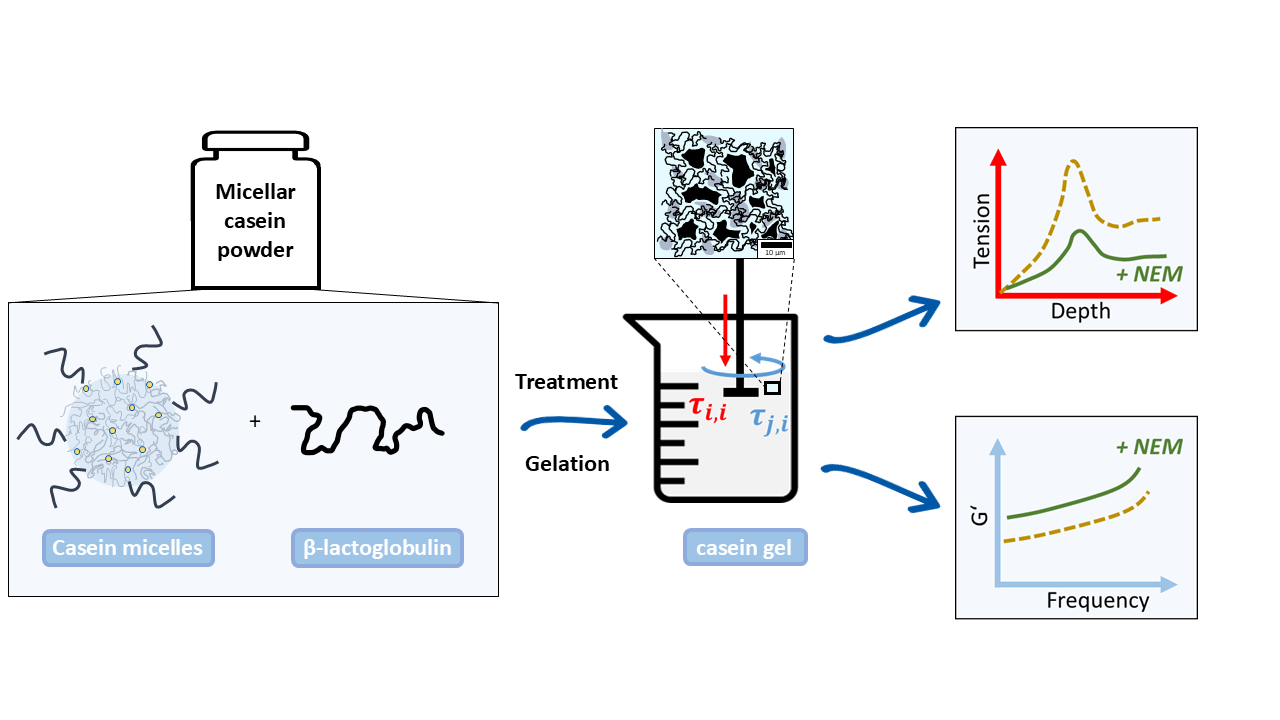

Figure 1 shows the interaction between denatured β-lactoglobulin and casein micelles. First, a buried thiol group in β-lactoglobulin is exposed due to thermal denaturation (Inset 1). Via thiol-disulfide exchange, β-lactoglobulin covalently binds to κ-casein by cleaving its disulfide bond, leaving a new thiol group for further crosslinking. NEM blocks this process by inhibiting the thiol groups of β-lactoglobulin, preventing further crosslinking (Inset 2).

After lowering the pH below the isoelectric point of casein micelles, a gel forms. However, the gelation process in suspensions from micellar casein powder (MCP) must be examined in detail due to its structural particularities, making it crucial to understand the underlying mechanisms that govern this unique behavior. MCP contains 84% total protein, of which 78.4±0.5% is casein and 5.6±% is whey protein, with 34.6±0.8% in its native form [

21,

22]. Unlike fresh milk, milk protein concentrates (MPC) are depleted in lactose and serum minerals due to ultrafiltration [

23]. MPC also differ from fresh milk in having reduced urea levels, calcium chelators, and varying calcium ion activities, which lead to different heat stability behaviors [

13,

24]. MCP, however, combines microfiltration and diafiltration, allowing some whey proteins, lactose, and serum minerals to pass through. The casein/whey ratio in MCP is 93:7, higher than in fresh milk or MPC [

13,

21]. Unlike traditional milk powders, MCP has recently gained commercial relevance due to its heat stability, making it suitable for sterilized food products without affecting protein structure [

25]. During MCP manufacturing, whey proteins are already denatured and partially associated with casein micelles, which influences the gelation process [

21].

These structural features affect how gels form under thermal or chemical conditions, especially the interaction between covalent and physical crosslinking within the network. A key element of these networks are WP/κ-casein complexes that form during heat treatment and exist as micelle-bound or soluble aggregates [

20,

27,

28]. Studies show that Bound Denatured Whey Proteins (BDWP), which covalently bind to casein micelles, significantly increase the storage modulus (G′) of acid gels [

28]. In contrast, Soluble Denatured Whey Proteins (SDWP) that do not interact with casein lead to weaker gels. However, these gels have limited gel strength, prompting research on methods to adjust gel strength (Anema, 2021; Schmidt, 1981). Inhibitors like N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) can reduce gel strength and elasticity, as covalent crosslinks between β-lactoglobulin and casein decrease with increasing inhibitor concentration [

17,

29].

This study investigates gelation mechanisms in systems consisting of micellar casein powder (MCP) with partially associated whey proteins. MCP is gaining importance as a functional food raw material, though its gelation properties are underexplored. Specifically, the effects of whey proteins on mechanical properties in the elastic and elastic-plastic regions have been little studied. The aim is to explore the rheological and mechanical properties of acid gels made from heat-treated MCP suspensions with and without NEM, compared to untreated MCP suspensions. Both covalent and non-covalent interactions that affect gel strength and deformation will be considered, with special attention to the impact of thermally treated whey proteins interacting with casein micelles. The use of thiol blockers like NEM will also be examined to distinguish between physical and chemical crosslinking in the gel structure.

2. Results

Differently treated samples were prepared from suspensions of micellar casein powder (MC) to investigate the influence of heat and thiol blocking on disulfide bridge formation. MC, untreated served as a control and was left at room temperature. MC, heat treated was heated to 70 °C for 11 minutes to induce thermally induced structural changes and possible protein cross-linking. In the other two samples, NEM was added prior to heat treatment to irreversibly block free thiol groups.

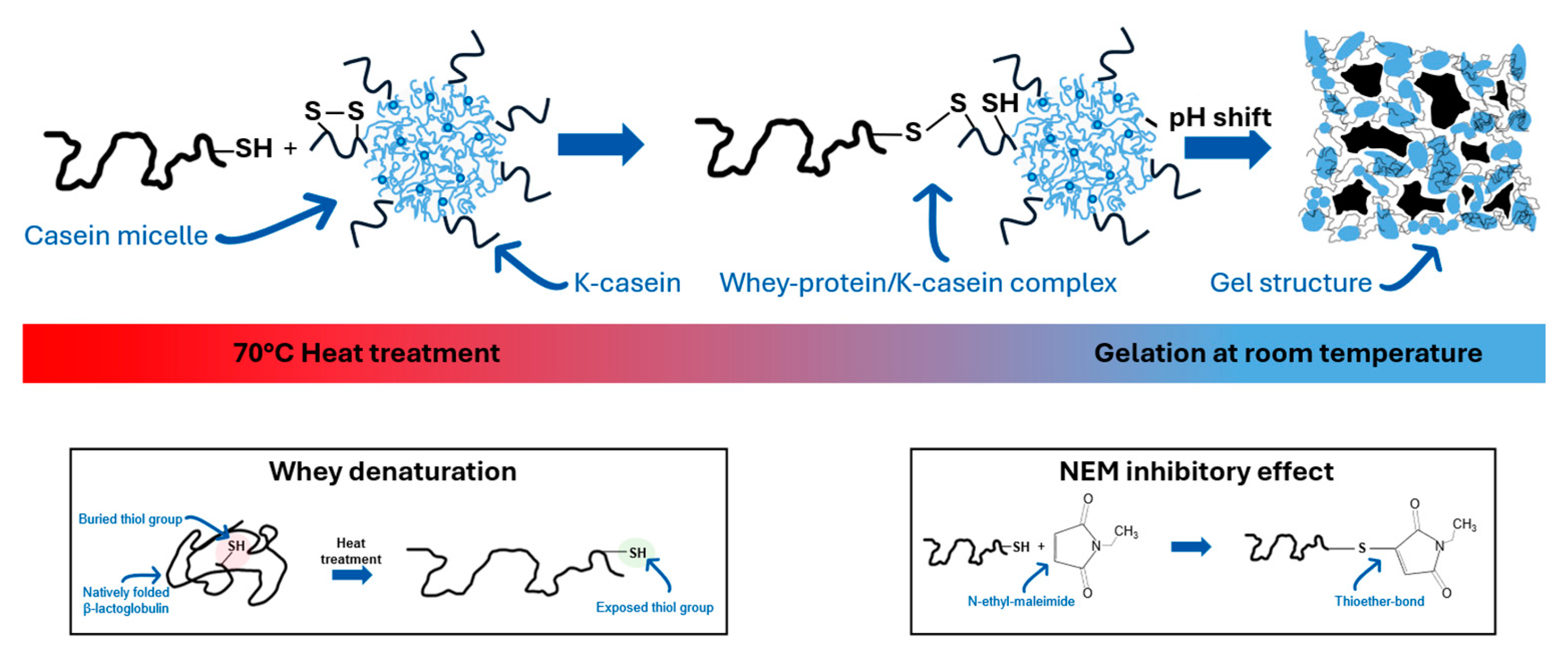

The disulfide bridges were determined using Ellman's reagent (DTNB) in combination with a reducing agent. The difference in absorbance with and without reducing agent was used as a measure of the number of reducible disulfide bridges. The results in

Figure 2 show the relative number of disulfide bridges in the total system (a) and in the supernatant b), each in relation to the value of MC, untreated.

In the total system, MC, heat-treated shows a significant increase in disulfide bridges (2.7 times compared to MC, untreated). This indicates a pronounced heat-induced cross-linking, especially between whey proteins and the structurally open casein micelles. However, in the samples with added NEM (MC, heat-treated + 40 mM NEM and MC, heat-treated + 100 mM NEM) the measured number of reducible disulfide bridges is almost zero. This shows that the alkylation by NEM has effectively blocked the thiol groups so that the SH groups released by the reduction could no longer be detected by the Ellman reagent.

In the supernatant, which contains mainly soluble whey proteins, the number of disulfide bridges in heat-treated MC remains almost unchanged compared to untreated MC. This is not because disulfide bridges do not form in whey proteins on heating, but because unfolded proteins are in an aggregated state and be pelleted during high-speed centrifugation. As a result, they are no longer present in the supernatant and are therefore not detected. However, these denatured whey proteins can expose reactive thiol groups and participate in thiol-disulfide exchange reactions, contributing to the increased disulfide bond content observed in the total system through intermolecular cross-linking with other whey proteins or casein micelles. In MC, heat-treated + 40 mM NEM, a reduced but still significant proportion of disulfide bridges was detected (0.2-fold), indicating incomplete alkylation. This may be due to limited accessibility of certain thiol or disulfide groups, possibly because they are embedded in compactly folded whey proteins, whose tertiary structure shields reactive groups more effectively than the structurally open casein micelles. In MC, heat-treated + 100 mM NEM, the value was almost zero, indicating an almost complete blocking of the thiol groups by the higher NEM concentration.

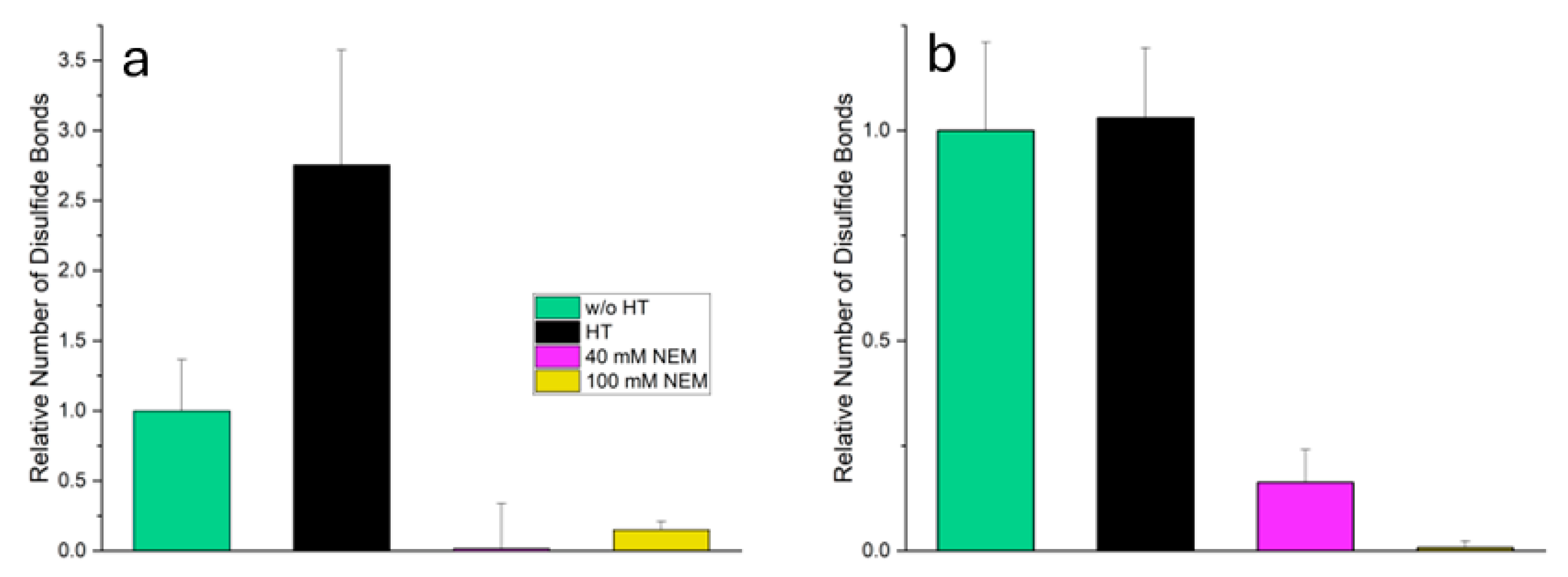

2.1. Microstructure of the gels

The macroscopic appearance of the gel of heat untreated micellar casein (

Figure 3a) shows a loose, weakly cross-linked structure, interspersed with channels about 1 µm wide, which make the network appear permeable. At the sub-microscopic level (see inset), the aggregates are composed of particles about 400 nm in size, which in turn are composed of many smaller spherical subunits. This finely structured hierarchical organization appears against a black background, which may indicate the absence of free denatured whey proteins in the surrounding medium.

After heat treatment (

Figure 3b), the gel has a much more compact appearance, with shorter, partially widened channels, some of which look almost like cavities. Again, the aggregates consist of approximately 400 nm units with substructure (see inset), but the background is now fluorescent, indicating denatured whey proteins that may not have been fully incorporated into the network.

In

Figure 3c (heat treatment + 40 mM NEM) the network appears finer meshed with uniform channels of approximately 500 nm width. The aggregates are significantly smaller (~250 nm, see inset), appear smoother, with no recognizable substructure, and show a thin (~50 nm) fluorescent shell - presumably due to surface adsorbed denatured whey proteins.

In

Figure 3d (heat treatment + 100 mM NEM), the submicroscopic structure is similar (see inset), but the channels are significantly widened to about 2 µm, indicating a looser, larger-pored network. The stronger inhibition of disulfide bridge formation at high NEM concentrations visibly results in a lower network density.

2.2. Gel Firmness During Shearing

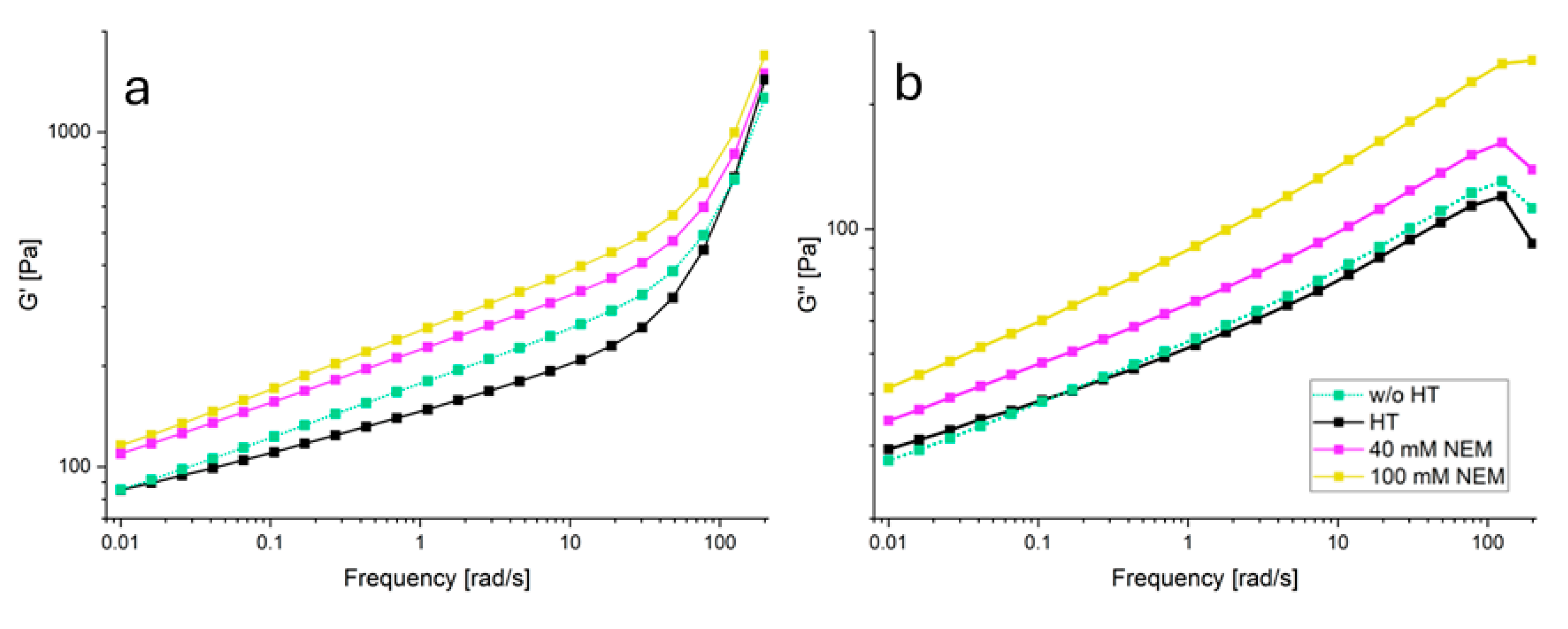

Acid gels containing differently pre-treated micellar casein were subjected to oscillatory shearing to investigate the effect of the disulfide network on the viscoelastic behavior. In

Figure 4 the material functions storage modulus G' and loss modulus G'' are plotted over a wide frequency range. With increasing NEM concentration, both G' and G'' increase over the whole frequency range without the shape of the curve changing significantly. The latter indicates that the mechanism of how the gels respond to shear is little changed by NEM. Two frequency ranges with different behavior can be identified for G' (

Figure 4a). In the first range, up to about 20 rad/s, there is a linear increase in the double logarithmic plot for all gel samples. Over the entire frequency range, G' is highest for the 100 mM NEM gel, followed by the 40 mM NEM gel, the untreated gel and the lowest values are observed for the heat-treated gel without NEM. At higher frequencies (>20 rad/s to 200 rad/s), G' continues to increase linearly for all samples, but at a significantly higher rate, with the increase being more pronounced for the gels without NEM compared to those with NEM.

G'' (

Figure 4b) also increases linearly in the double-log plot for all samples up to 100 rad/s. The untreated gel and the heat-treated gel without NEM show almost identical behavior, while the gels with NEM again (40 mM and 100 mM) show higher G'' values. The highest G'' values are observed in the gel with 100 mM NEM.

2.3. Gel Firmness in the Compression Test

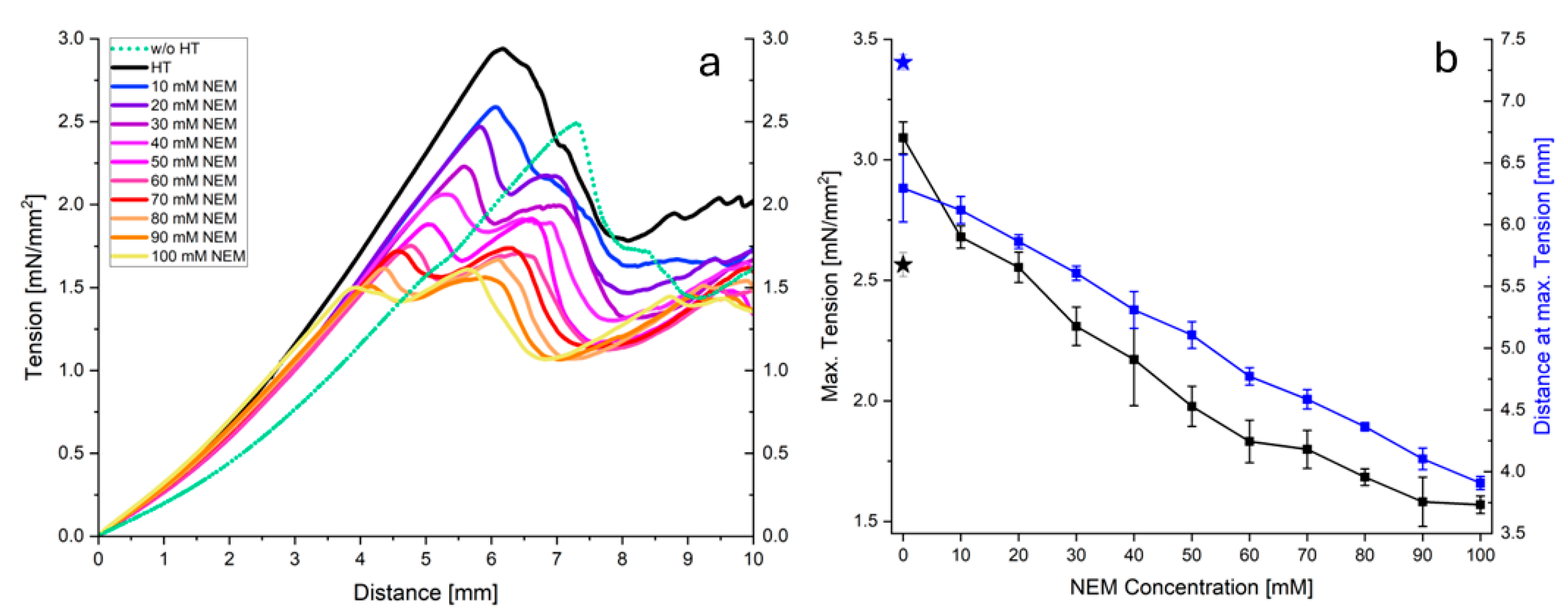

In addition to the shear effect, the behaviour of the gels under compressive load was also investigated using a cylindrical specimen.

Figure 5a shows the stress-strain curves obtained for acid gels prepared from micellar casein pretreated at 60 °C and different NEM concentrations. In general, a linear, two-phase, progressive course to a maximum value can be observed for all curves (

Figure 5a). It can clearly be seen that as the NEM concentration increases, both the increase in the second phase and the maximum value reached decrease. Thereafter the stress decreases due to irreversible gel damage, which was not considered for further analysis. In

Figure 5b, the maximum stress (peak maximum) and Young's modulus (initial increase) are plotted as a function of NEM concentration. The maximum stress in the gel decreases almost linearly with increasing NEM concentration. In contrast, despite the large error bars, it can be seen that the elasticity of the gel changes in a parabolic fashion. Up to 40 mM NEM, the modulus of elasticity first decreases and then increases again as the concentration of the thiol blocker is further increased.

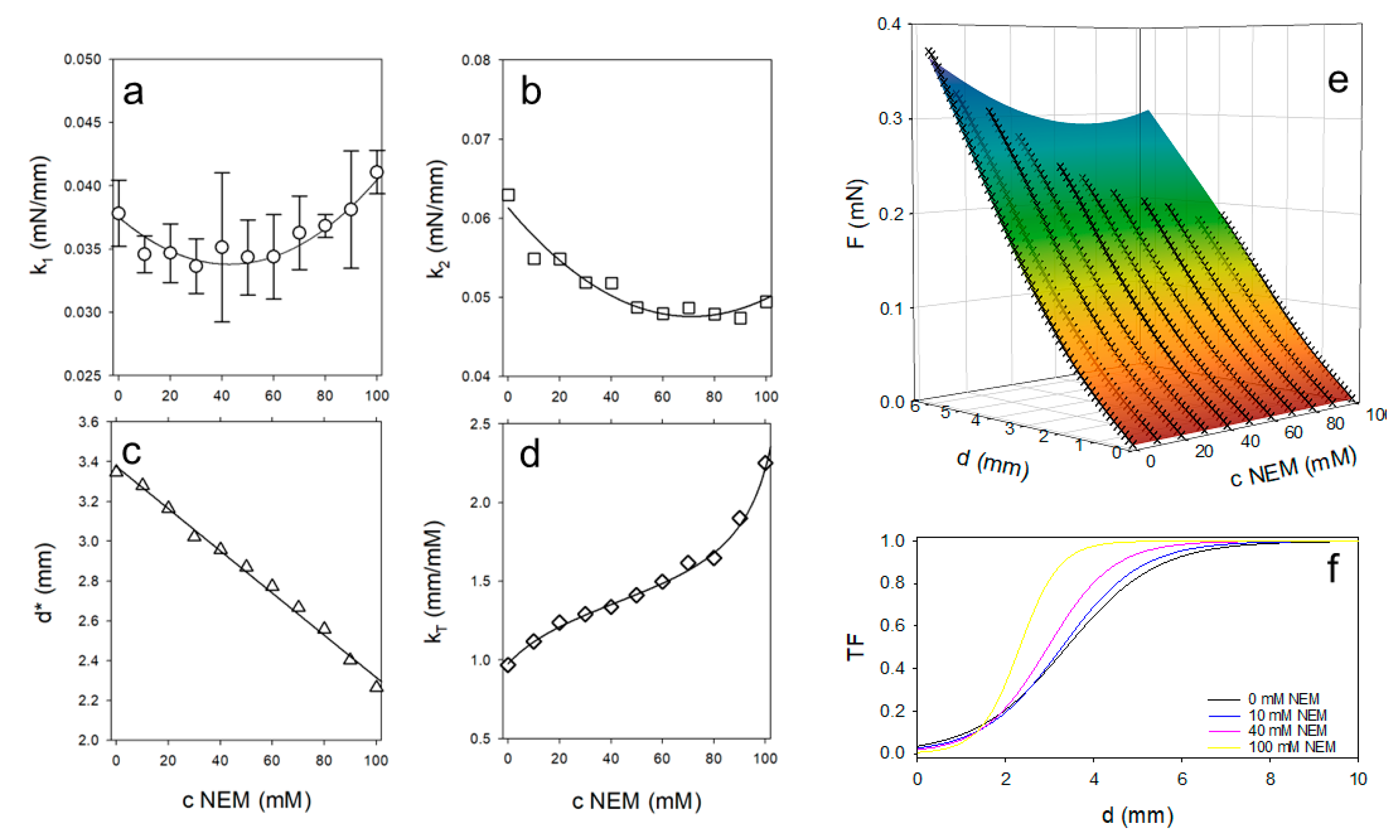

In order to investigate the elastic-plastic behavior of the gels up to the maximum stress, a model has been established which links two linear force-displacement functions with the slopes k1 and k2 with a transition function TF:

If d << d*, the denominator of TF becomes very large and TF -> 0. As a result, the first summand of equation 1 dominates the model curve. On the other hand, if d* >> d, the exponential term tends to 0 and the second summand describes the further course of the measurement curve. Equation 1 was fitted to the original data (force instead of pressure) using a non-linear fit. The values of the fit parameters are plotted as symbols in

Figure 6a–d. As shown in

Figure 6a, the values for k

1 change in a parabolic fashion with NEM concentration. Up to approximately 40 mM NEM, the slope of the force-displacement curves initially decreases and then increases as the concentration of thiol blocker is further increased. In contrast, the slope of the second part of the curve, k

2, decreases degressively with increasing NEM concentration. The value d* indicates the depth of penetration into the gel at which TF = ½ and thus the transition between the two linear sections occurs.

Figure 6c shows that d* decreases linearly with increasing NEM concentration. The steepness of the transition, described by k

T, initially increases to a plateau value at intermediate NEM concentrations and then increases steeply again as shown in

Figure 6d. The symmetry of the values for k

1 and k

T around a central region indicates two different gel structures induced by the addition of NEM. In order to characterize the transition region via a characteristic NEM concentration c*, equation 1 was extended to include concentration-dependent functional relationships for the fit parameters, where simple parabolas have been chosen for k

1 and k

2 via

a linear function for d* via

and a point symmetric function for k

T via

The parameter values in equations 4 and 5 were determined directly by fitting the data in

Figure 6c,d (see

Table 1, printed in regular type). In particular, the characteristic NEM concentration for the transition region was determined to be c* = 42.7 mM. The parameter values for equation 3, describing the more scattering parameters k

1 and k

2, were determined by simultaneously fitting the overall model to all force-distance curves over the entire concentration range (see

Table 1, printed in bold).

Figure 6e shows the very good simultaneous model fit (R

2 = 0.998) to all data as a hypersurface. Using the concentration dependence of k

T, the transition functions, TF, could be calculated for selected NEM concentrations. As shown in

Figure 6f, the transition between the two regions of the force-displacement curve is steeper and occurs at a lower depth of penetration of the sample into the gel as the NEM concentration increases.

3. Discussion

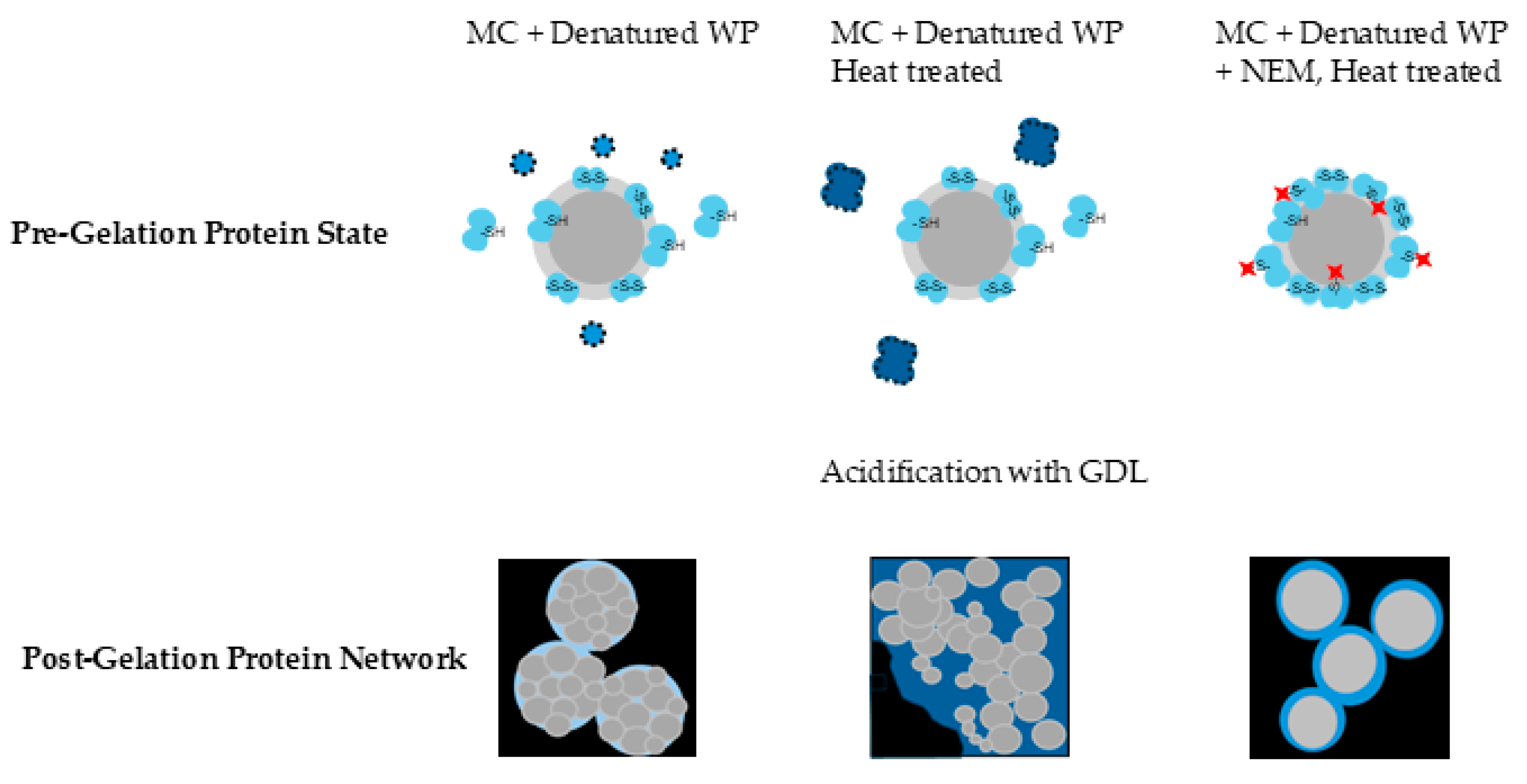

The present study investigated the effects of NEM on the microstructure and mechanical behavior of acidified gels of micellar casein powder. The results show a concentration-dependent transition in gel structure and function, which is closely related to the thiol-blocking activity of NEM.

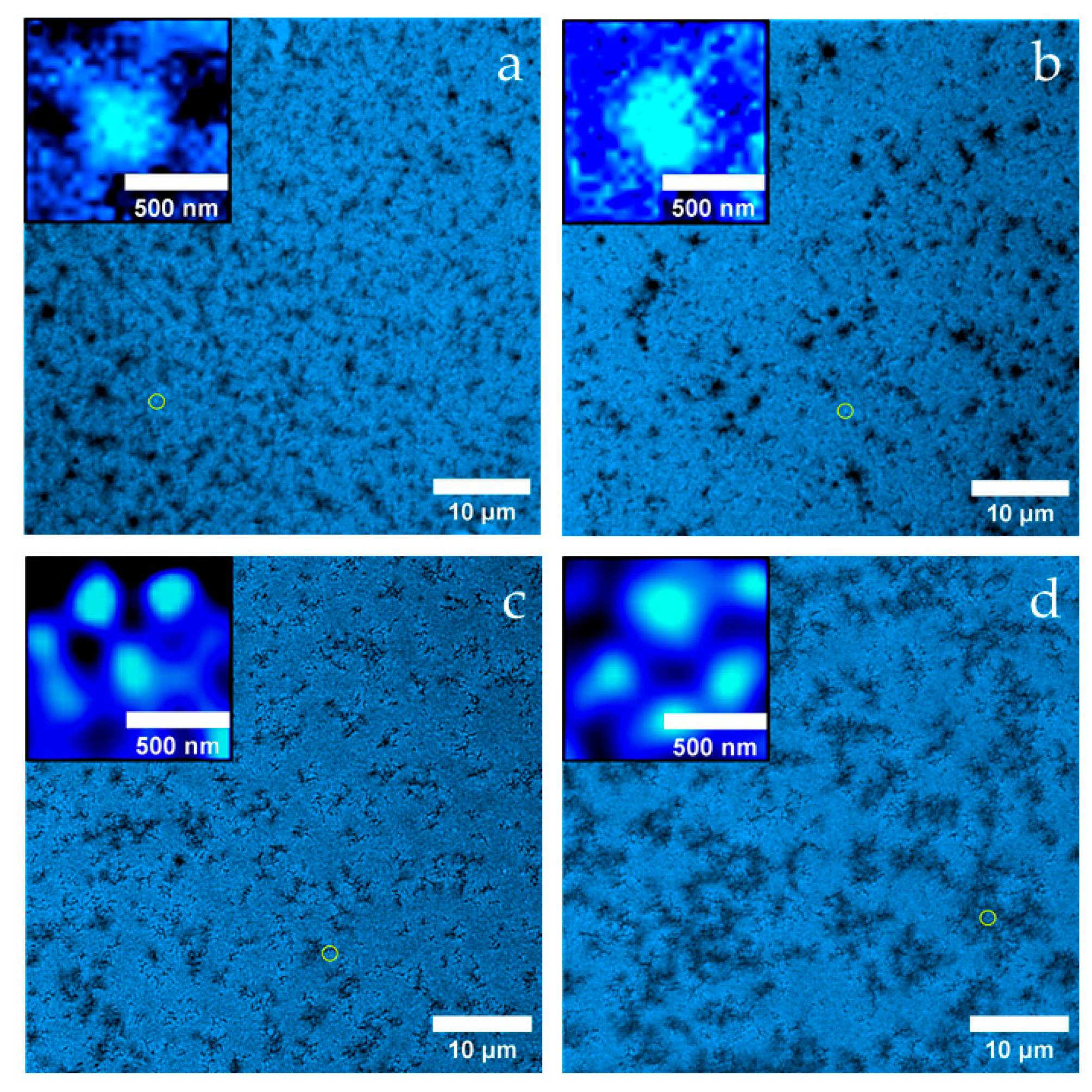

The gel networks of both the untreated reference and the heat-treated micellar casein sample without NEM consisted of differently sized particles, which formed as a result of acid-induced alterations in micellar structure [

30]. The gel obtained from heat-treated micellar casein without NEM showed a more compact microstructure compared to the untreated reference. In particular, background fluorescence was observed indicating the presence of unbound denatured whey protein aggregates (

Figure 7, bottom row). Aggregates are highlighted in the schematic representation of the initial state, where the denatured whey protein aggregates are shown as freely dispersed or partially associated with the micellar surfaces (

Figure 7, top row). These aggregates are likely to intercalate between the casein micelles and weaken the cohesion of the network at the molecular level, resulting in a slightly less cohesive gel. Accordingly, this sample exhibited the lowest G' and G'' values across all conditions tested, indicating reduced shear stability and reduced elastic and viscous resistance. However, in compression tests this gel exhibited the highest fracture stress, suggesting mechanical reinforcement likely mediated by disulfide cross-links between denatured whey proteins and casein micelles, despite its limited resistance to shear deformation. These covalent bonds appear to be more important under conditions of plastic deformation, where they increase the load-bearing capacity of the gel network.

In contrast, gels containing NEM (40 and 100 mM) showed smaller, smoother aggregates with no internal substructure and peripheral fluorescence, suggesting surface-bound hydrophobically associated whey proteins. The initial state of these gels (

Figure 7, top row) shows the presence of thiol-blocked denatured whey proteins which bind to the surface of the casein micelles forming a protective layer around them. This protective layer prevents the 250 nm casein particles/micelles from disintegrating during acidification, which was the case in the samples without NEM. This aligns with the observation by Lucey et al., who found that small amounts of denatured whey proteins associated with casein micelles during low-heat processing resulted in stronger gels with higher G′ values [

28]. These gels exhibited the highest G' and G'' values across the frequency range, indicating increased shear stability and a denser, physically stabilized network. G' remained greater than G'' across the entire frequency range, confirming the predominantly elastic nature of these gels. The normal force tests show a two-phase response with two linear force increases, the first corresponding to elastic behavior and the second reflecting plastic deformation due to polymer chain slippage. The maximum force decreases almost linearly with increasing NEM concentration, while the penetration depth at which this is achieved also decreases continuously. This shows that the plastic deformability of the material is reduced with increasing NEM and the gel becomes less resistant. These findings are consistent with those of Vasbinder et al, who demonstrated that the presence of whey protein aggregates significantly increases gel hardness, whereas NEM-induced thiol blockade reduces gel hardness by preventing disulfide bond formation between protein components [

29]. Our observation of high gel hardness but relatively low storage modulus in gels containing whey protein aggregates supports the findings of Lucey et al., although Vasbinder et al. questioned this correlation based on discrepancies between force-distance slopes and modulus data [

28,

29]. This duality between gel hardness and storage modulus is also reflected in our own experiments, in which an increase in the NEM concentration changes the mechanical properties of the gel, particularly with regard to plastic deformation.

The initial elastic increase of the force-displacement curve shows a parabolic course: it decreases up to average NEM concentrations of c* = 42 mM and increases again at higher concentrations. This can be explained by the disappearance of large rigid aggregates, followed by an increasing stiffness of the remaining matrix. In contrast, the second, plastic increase decreases continuously, indicating a higher polymer chain mobility with increasing NEM concentration. Due to the reduced cross-linking via disulfide bridges, the chains can slide more easily, which means that the gel offers less resistance to plastic deformation. This increased mobility also explains the lower maximum force and the earlier occurrence of this force at lower penetration depths, as the gel becomes more flexible overall.

The initial broad transition curve between the elastic and plastic regions becomes progressively sharper with increasing NEM concentration and takes on an increasingly stepped shape. This indicates an abrupt change in resistance to plastic deformation. The increasing homogeneity of the mechanical properties of the gel is supported by the changes in microstructure discussed above.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that NEM modulates gel properties by altering microstructure and cross-linking capacity. While NEM increases shear resistance by forming compact physical networks, it reduces covalent cross-linking and hence mechanical integrity under compressive loading. This dual effect highlights the complex interplay between molecular interactions and macroscopic gel mechanics.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals

For the suspensions, micellar casein powder MC88 was used (MILEI GmbH, Germany). N-ehtylmaleimide (NEM) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Glucono delta-lactone (GDL) was bought from Thermo Fisher (Thermo Fisher, USA). Simulated milk ultrafiltrate (SMUF) was prepared according to the composition proposed by Dumpler [

31]. All salts for the SMUF solution were of analytical grade. To inhibit bacterial growth, 0.5 g/L sodium azide was added to the mixture.

4.2. Preparation of Casein Suspensions

Simulated milk ultrafiltrate (SMUF) was prepared according to the procedure described by Dumpler et. al. To prevent bacterial growth, 0.5g/L sodium azide was added. Lactose was dissolved in SMUF by moderate stirring. Then, MC88 was added to obtain a final casein concentration of 5% w/w. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h, at 4°C for 16 h and for 1 h at 37°C to fully hydrate the casein micelles. NEM was added in concentrations from 0-100 mM/L and to obtain a homogeneous gel, the solution was then gently stirred at 30°C for 24 h.

4.3. Heat Treatment and Gelation

To initiate denaturation of β-lg, the solution was heated at 70°C for 11 min and subsequently cooled in ice water for 10 min. 0.5g GDL /g casein was added to initiate the gelation process. The mixture was stored at room temperature for about 20 h prior to testing.

4.4. Mechanical Tests

Deformation tests were performed with the texture analyzer AGS-X (Shimadzu, Japan). A circular plunger with 12.7 mm in diameter penetrated the gels and a force-distance curve was obtained at a crosshead speed of 0.1 mms-1. Gel hardness was expressed as the maximum stress at the maximum peak of the force-distance curve (Bourne, 1978). Elasticity was determined in the range from 0-1.5mm where the lines show linear progression. All experiments were at least performed in triplicate.

4.5. Rheology

Storage modulus G’ and loss modulus G’’ were determined using a MCR501 Rheometer (Anton Paar, Austria). Measurements were performed using the plate-plate geometry PP25 with a stainless steel plate (d = 25 mm) and tinplate single-use cups (d = 65 mm), which were filled with 3.5 g of the casein solution prior to gelation. The gap height was set to 1 mm. After application of the axial force, the edges of the sample were removed using a scalpel. Liquid paraffin oil was applied to the edges to reduce evaporation. Additionally, a solvent trap further minimized moisture evaporation. Then, the sample was allowed to rest for five minutes prior to testing to reduce any tension effects due to application. Frequency sweeps were carried out at 0.65% constant strain which was found to be within the linear viscoelastic range determined by an amplitude test. Frequency sweeps were carried out between a range of 0.01 and 200 rad/s. All measurements were performed at room temperature and at least in triplicate.

4.6. Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy

Imaging was performed using the LSM 980 Airyscan 2 confocal scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Germany). Subsequently to GDL addition, the gels were stained with the fluorescent dye pyranine (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Excitation was at 340 nm and emission was detected at 512 nm.

4.7. Determination of Disulfide Bonds

Disulfide bonds in the samples were reduced as follows: Samples were diluted in SMUF buffer and incubated with 5 mM/L Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP, Apollo Scientific, UK) at room temperature for 30 min in a shaking incubator. Following reduction, free thiol groups were quantified using Ellman's reagent 5,5'-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB, Apollo Scientific, UK). Samples were incubated with 1.5 mM/L DTNB at room temperature for 15 min again in a shaking incubator. For the measurement of the serum phase, the samples were centrifuged at 70.100 g and 25°C for 1 h using an Optima XPN-80 ultracentrifuge (Beckman Coulter, USA). Absorbance was measured at 412 nm using a BioTek Snyergy HTX microplate reader (Agilent Technologies, USA), and baseline scattering (800–900 nm) was subtracted from all measurements. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of blocked thiol groups on the structure and mechanical properties of casein-based gels, all subjected to identical heat treatment. By selectively blocking free thiol groups prior to denaturation, the formation of covalent disulfide bridges between whey proteins and casein was suppressed. While spherical protein aggregates were observed in all samples, the thiol-blocked gels exhibited significantly smaller aggregates and smooth surfaces without internal substructure, probably due to reduced hydration and increased physical aggregation.

A particularly striking feature was the complementary mechanical behavior: under shear stress, the thiol-blocked gels exhibited the highest storage (G′) and loss moduli (G″) of all samples tested, with moduli increasing with increasing blocker concentration. However, these networks proved to be pressure sensitive in compression tests, failing after only minimal deformation. In contrast, the heat-treated sample without NEM showed the highest fracture stress, suggesting that disulfide cross-linking plays a critical role in compressive strength. This ambivalent behavior suggests the formation of dense, physically stabilized network structures that are highly resistant to shear but less resilient under compressive load due to suppressed covalent cross-linking.

The results suggest that by selectively modifying the cross-linking mechanisms, it is possible to precisely control the mechanical properties of the gels. Products with specific texture requirements, such as those requiring high spread ability while maintaining dimensional stability, could benefit from physically dominated gel structures. This opens up potential applications in a wide range of products with specific texture requirements.

In the future, the use of additional modifiers, such as specialized additives or blockers, could further optimize the balance between shear stability and compressive strength. Overall, the deliberate separation of covalent and physical network formation opens up new possibilities for the development of innovative, functional food structures.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, T.P. and R.G.; methodology, T.P. and R.G.; validation, T.P. and R.G.; formal analysis, R.G. and T.P.; investigation, T.P.; resources, R.G.; data curation, T.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G. and T.P.; writing—review and editing, R.G. and T.P.; visualization, T.P. and R.G.; supervision, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. rer. nat. Sabrina Ernst from the Confocal Microscopy Facility at University Hospital Aachen for her support with confocal microscopy. We are also grateful to MILEI GmbH for the generous provision of micellar casein powder. Special thanks are extended to Ms. Alexandra Airich for her valuable assistance in the laboratory.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Yang, Y.; Xu, Q.; Wang, X.; Bai, Z.; Xu, X.; Ma, J. Casein-based hydrogels: Advances and prospects. Food Chemistry 2024, 138956. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.T.; Chassenieux, C.; Nicolai, T.; Schmitt, C. Effect of the pH and NaCl on the microstructure and rheology of mixtures of whey protein isolate and casein micelles upon heating. Food Hydrocolloids 2017, 70, 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Thill, S.; Schmidt, T.; Wöll, D.; Gebhardt, R. A regenerated fiber from rennet-treated casein micelles. Colloid Polym Sci. 2021, 299(5), 909–914. [CrossRef]

- Asaduzzaman, M.; Gebhardt, R. Influence of Post-Treatment Temperature on the Stability and Swelling Behavior of Casein Microparticles. Macromolecular Materials and Engineering 2023, 308(4), 2200661. [CrossRef]

- Bastard, C.; Schulte, J. C. T.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Hohn, C.; Kittel, Y.; De Laporte, L.; Gebhardt, R. Casein microparticles filled with cellulase to enzymatically degrade nanocellulose for cell growth. Biomaterials Science 2025. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. H.; Wong, M.; Anema, S. G.; Havea, P.; Guyomarc’h, F. Effects of adding low levels of a disulfide reducing agent on the disulfide interactions of β-lactoglobulin and κ-casein in skim milk. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2012, 60(9), 2337-2342. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Singh, H.; Creamer, L. K. Heat-induced interactions of β-lactoglobulin A and κ-casein B in a model system. Journal of Dairy Research 2003, 70(1), 61-71. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H. D.; Swaisgood, H. E. Disulfide bond formation between thermally denatured β-lactoglobulin and κ-casein in casein micelles. Journal of Dairy Science 1990, 73(4), 900-904. [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, T.; Gazi, I.; Luyten, H.; Nieuwenhuijse, H.; Alting, A.; Schokker, E. Hydration of casein micelles and caseinates: Implications for casein micelle structure. International Dairy Journal 2017, 74, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Dalgleish, D. G. On the structural models of bovine casein micelles—review and possible improvements. Soft matter 2011, 7(6), 2265-2272. [CrossRef]

- De Kruif, C. G.; Huppertz, T.; Urban, V. S.; & Petukhov, A. V. Casein micelles and their internal structure. Advances in colloid and interface science 2012, 171, 36-52.

- Thill, S.; Schmidt, T.; Wöll, D.; Gebhardt, R. Single particle tracking as a new tool to characterise the rennet coagulation process. International Dairy Journal 2020, 105, 104659. [CrossRef]

- Anema, S. G. Heat-induced changes in caseins and casein micelles, including interactions with denatured whey proteins. International Dairy Journal 2021, 122, 105136. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.H. Gelation and Coagulation. In: J.P. Cherry (Ed.), Protein Functionality in Foods. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society, 1981, 131–147,. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; & Latham, J. M. Heat stability of milk: Aggregation and dissociation of protein at ultra-high temperatures. International Dairy Journal 1993, 3(3), 225-237. [CrossRef]

- Vasbinder, A. J.; Alting, A. C.; Visschers, R. W.; de Kruif, C. G. Texture of acid milk gels: formation of disulfide cross-links during acidification. International Dairy Journal 2003, 13(1), 29-38. [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Cheftel, J. C. Texture characteristics, protein solubility, and sulfhydryl group/disulfide bond contents of heat-induced gels of whey protein isolate. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1988, 36(5), 1018-1025. [CrossRef]

- Ruprichová, L.; Králová, M.; Borkovcová, I.; Vorlová, L.; Bedáňová, I. Determination of whey proteins in different types of milk. Acta Veterinaria Brno 2014, 83(1), 67-72. [CrossRef]

- Lavoisier, A.; Vilgis, T. A.; Aguilera, J. M. Effect of cysteine addition and heat treatment on the properties and microstructure of a calcium-induced whey protein cold-set gel. Current research in food science 2019, 1, 31-42. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, Y.; Cao, J.; Jiang, L.; Wang, P.; Ren, F.; Yi, H. Exploration of dynamic interaction between β-lactoglobulin and casein micelles during UHT milk process. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 277, 134367. [CrossRef]

- Warncke, M.; Kulozik, U. Functionality of MC88-and MPC85-enriched skim milk: Impact of shear Conditions in rotor/stator Systems and high-pressure Homogenizers on powder Solubility and rennet gelation behavior. Foods 2021, 10(6), 1361. [CrossRef]

- Meena, G. S.; Singh, A. K.; Panjagari, N. R.; Arora, S. Milk protein concentrates: opportunities and challenges. Journal of food science and technology 2017, 54, 3010-3024. [CrossRef]

- Schokker, E. P.; Church, J. S.; Mata, J. P.; Gilbert, E. P.; Puvanenthiran, A.; Udabage, P. Reconstitution properties of micellar casein powder: Effects of composition and storage. International Dairy Journal 2011, 21(11), 877-886. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, S. V.; Megemont, M.; Gazi, I.; Kelly, A. L.; Huppertz, T.; O'Mahony, J. A. Heat stability of reconstituted milk protein concentrate powders. International Dairy Journal 2014, 37(2), 104-110. [CrossRef]

- Beliciu, C. M.; Sauer, A.; Moraru, C. I. The effect of commercial sterilization regimens on micellar casein concentrates. Journal of dairy science 2012, 95(10), 5510-5526. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G. J.; Williams, R. P. W.; Dunstan, D. E. Comparison of casein micelles in raw and reconstituted skim milk. Journal of Dairy Science 2007, 90(10), 4543-4551. [CrossRef]

- Donato, L.; Guyomarc'h, F. Formation and properties of the whey protein/κ-casein complexes in heated skim milk–A review. Dairy Science and Technology 2009, 89(1), 3-29.

- Lucey, J. A.; Tamehana, M.; Singh, H.; Munro, P. A. Effect of interactions between denatured whey proteins and casein micelles on the formation and rheological properties of acid skim milk gels. Journal of Dairy Research 1998, 65(4), 555-567. [CrossRef]

- Vasbinder, A. J.; van de Velde, F.; de Kruif, C. G. Gelation of casein-whey protein mixtures. Journal of Dairy Science 2004, 87(5), 1167-1176.

- Foroutanparsa, S.; Brüls, M.; Tas, R. P.; Maljaars, C. E. P.; Voets, I. K. Super resolution microscopy imaging of pH induced changes in the microstructure of casein micelles. Food Structure 2021, 30, 100231. [CrossRef]

- Dumpler, J. Preparation of simulated milk ultrafiltrate. In Heat Stability of Concentrated Milk Systems: Kinetics of the Dissociation and Aggregation in High Heated Concentrated Milk Systems 2017, 103-122. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).