Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The History and Evolution of GPUs

1.2. GPU vs CPU: Similarities and Differences in Architecture and Fundamentals

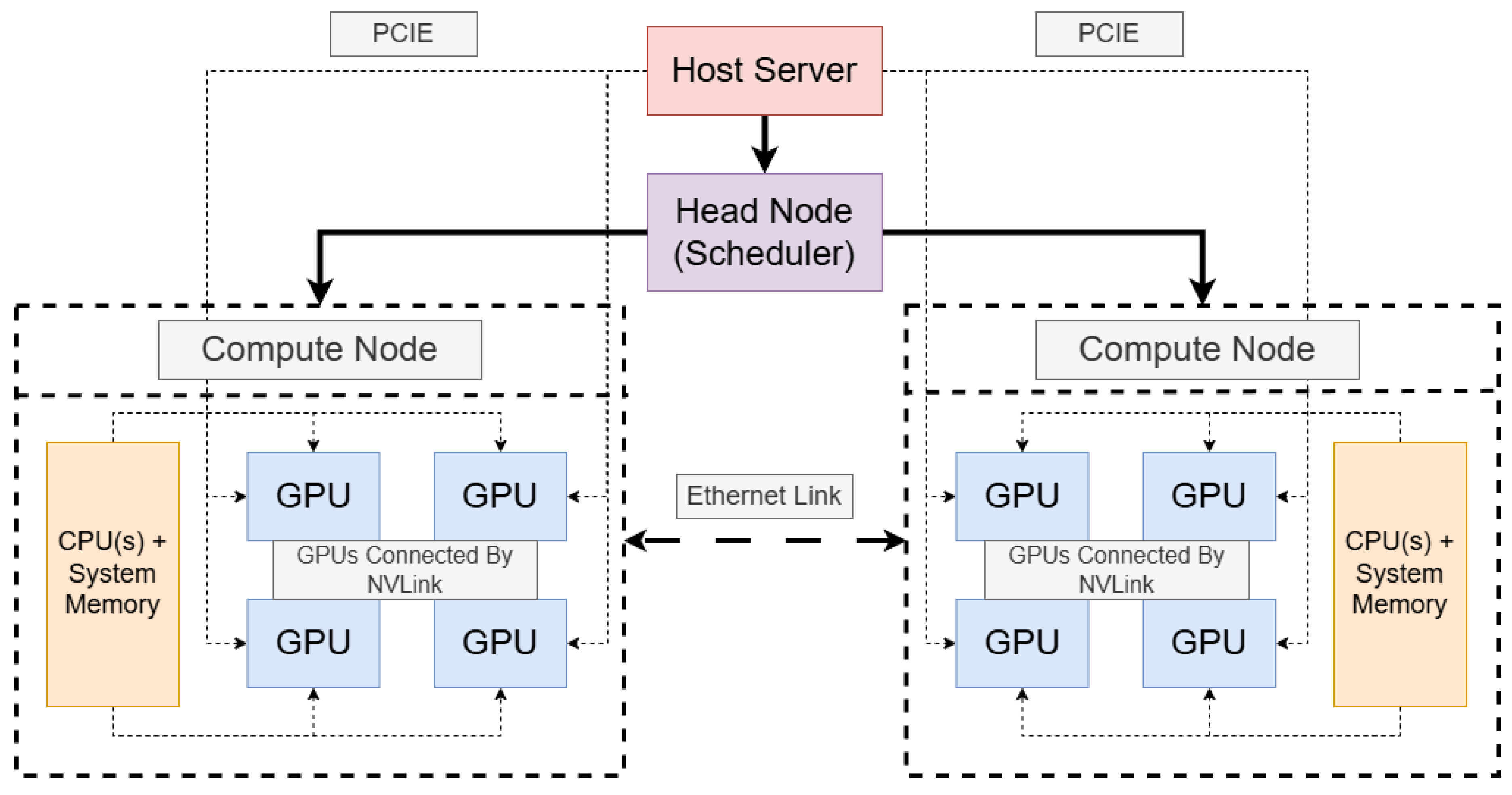

1.3. Cluster Computing and the Necessity of GPU Scheduling Algorithms

1.4. Paper Overview

2. Models

2.1. Components of a Model

- GPU demand (which may be fractional or span multiple GPUs),

- estimated runtime ,

- release time (for online arrivals),

- optional priority or weight.

2.2. Categorization of Models

- First-fit: assign each job to the first available GPU or time slot.

- Best-fit: assign each job to the GPU or slot that minimizes leftover capacity.

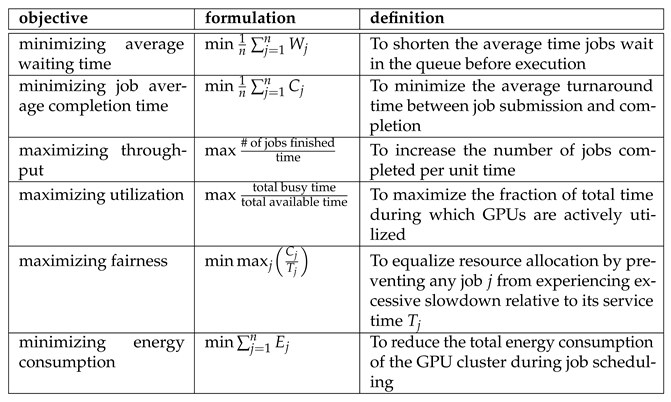

2.3. Evaluation Metrics and Validation Methods for Scheduling Models

- Theoretical analysis, which proves bounds on performance or fairness under idealized assumptions;

- Simulation, which enables controlled studies—often using trace-driven or synthetic workloads—to compare designs across diverse scenarios;

- Real-world experiments, which deploy schedulers on actual clusters to evaluate behavior under production traffic and uncover practical considerations such as implementation overhead or robustness to unexpected load spikes. Together, these methods provide a comprehensive picture of a model’s strengths, limitations, and applicability.

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Models

- Queueing models – Pros: Analytically tractable; provide closed-form performance bounds and optimal policies under stochastic assumptions. Cons: Scale poorly to large systems without relaxation or decomposition; approximations may sacrifice true optimality.

- Optimization models – Pros: Express rich constraints and system heterogeneity; deliver provably optimal schedules within the model’s scope. Cons: Become intractable for large, dynamic workloads without heuristic shortcuts or periodic re-solving; deterministic inputs may not capture runtime variability.

- Heuristic methods – Pros: Extremely fast and scalable; simple to implement and tune for specific workloads; robust in practice. Cons: Lack formal performance guarantees; require careful parameterization to avoid starvation or unfairness.

- Learning-based approaches – Pros: Adapt to workload patterns and capture complex, nonlinear interactions (e.g., resource interference) that fixed rules miss. Cons: Incur training overhead and cold-start penalties; produce opaque policies that demand extensive validation to prevent drift and ensure reliability.

3. Scheduling Algorithms and Their Performance

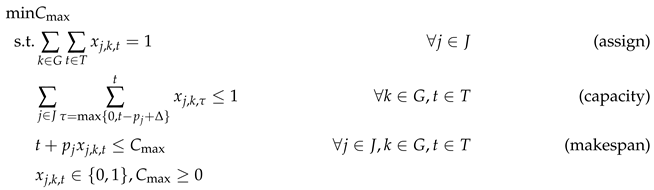

3.1. Classical Optimization Algorithms

- First-Fit (FF). Scan the queue and assign the first job whose demand fits the current free set B of GPUs.

- Best-Fit (BF). Among jobs that fit, choose the one minimizing the leftover capacity .

- Continuous relaxation. Replace with , solve the LP, then round the fractional solution.

- List-scheduling rounding. Sort jobs by LP-derived completion times and assign greedily to the earliest available GPU.

3.2. Queueing-Theoretic Approaches

3.3. Learning-Based Adaptive Algorithms

-

Exploration vs. exploitation.Learning demands trying suboptimal actions, which in live clusters can degrade performance. Most systems therefore train offline on simulators or historical traces, but must retrain or fine-tune when workloads or hardware change.

-

State-space explosion.Real clusters host hundreds of jobs, blowing up the state. Abstractions—DeepRM’s image grid, Decima’s graph embeddings, or transformer/attention mechanisms [161]—are essential to focus on relevant features.

-

Stability and safety.Unconstrained RL policies may starve jobs or violate service guarantees. Hybrid designs combine learned policies with hard constraints (e.g., maximum wait time or GPU caps) to enforce correctness.

-

Interpretability.RL models are often opaque, making it hard to diagnose why a particular scheduling decision occurred. This opacity can hinder trust in mission-critical environments [162].

3.4. Comparative Analysis

-

Minimizing average job completion time (JCT).Theoretically, SRPT and Gittins-index scheduling are optimal when job sizes or distributions are known [79]. In practice, shortest-job-first (SJF) with accurate runtime predictions yields strong results.

-

Maximizing utilization.Packing heuristics, best-fit allocation, and non-preemptive strategies (e.g., FCFS or backfilling) maintain high GPU occupancy and minimize idle intervals.

-

Ensuring fairness.Time-sharing mechanisms such as LAS or round-robin prevent job starvation. Cluster-level extensions — like Themis’s auction-based allocation — provide explicit fairness guarantees at the cost of added coordination overhead [81].

-

Multi-objective optimization.To balance responsiveness, fairness, and efficiency, heuristic frameworks often employ weighted-sum priority scores (e.g., blending estimated slowdown with job importance). RL policies can natively address multiple objectives through reward shaping, dynamically discovering trade-offs via techniques like the “power-of-two-choices.”

3.5. Summary of Scheduling Algorithms and Their Applicability Concerns

-

Offline deterministic scenarios.When job characteristics are fully known in advance, ILP or dynamic programming (DP) formulations yield optimal schedules, whereas simple greedy heuristics can perform very poorly.

-

Online workloads with heavy-tailed jobs.In cases where job sizes are unknown and heavy-tailed distributions prevail—typical of many training workloads—queueing-theoretic policies such as Gittins or LAS effectively balance fairness and mean slowdown [79].

-

Online workloads with predictable jobs.If runtimes are periodic or otherwise predictable, static reservations or simple rules (e.g., SJF) often suffice, although dynamic SJF still performs near-optimally when predictions are accurate.

-

Heterogeneous resources.For clusters with diverse GPU types, algorithms like Gavel normalize throughput across devices [169]. A two-stage approach—first matching jobs to resource classes (e.g., via ML or bipartite matching) and then applying standard scheduling within each class—can also be effective.

-

Multi-tenant cloud environments.Fairness and isolation are paramount. Partial-auction mechanisms (e.g., Themis) or fair-share frameworks (e.g., DRF) are widely adopted, often supplemented by inner-loop policies like SJF to optimize per-job latency.

-

Resource-manager interfacing.Obtaining real-time availability requires communicating with the cluster’s control plane or writing scheduler extenders/plugins (e.g., for Kubernetes) [170].

-

Distributed and batch workloads.Handling multi-node jobs and systems like Slurm, which lack fine-grained preemption support, complicates dynamic rescheduling.

-

Framework coordination.

-

GPU-specific interfaces.Scheduler plugins may need to invoke NVIDIA APIs to manage MIG partitions or query per-device utilization.

-

Scheduler overhead and latency.Advanced policies — such as AlloX’s matching [120] or Decima’s neural-policy evaluation [123] — can introduce noticeable decision latency. Amortizing this cost (e.g. by only reevaluating every minute) trades responsiveness for efficiency, but in practice most systems lean heavily on heuristics that make sub-millisecond decisions.

-

Preemption, checkpointing, and oversubscription.While many fairness-driven and queueing models employ preemption, writing GPU state to disk remains expensive. Techniques like graceful preemption at iteration boundaries mitigate impact [171]. Alternatively, oversubscription with throttling (e.g., SALUS) multiplexes GPU memory and streams to avoid full context switches, at the expense of reduced per-job throughput [173].

-

Monitoring and adaptivity.Adaptive schedulers require fine-grained telemetry (via node agents or in-band probes) so that migration and admission controls are based on up-to-date data. This monitoring itself adds overhead and must be designed carefully to avoid stale data or oscillatory scheduling behavior.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For deep-learning supercomputers, MARBLE refines FF by dynamically resizing each job’s GPU allocation using its empirical scalability curve, further boosting throughput [139]. |

References

- Dally, W.J.; Keckler, S.W.; Kirk, D.B. Evolution of the graphics processing unit (GPU). IEEE Micro 2021, 41, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, J. The History of the GPU-Steps to Invention; Springer, 2023.

- Peddie, J. What is a GPU? In The History of the GPU-Steps to Invention; Springer, 2023; pp. 333–345.

- Cano, A. A survey on graphic processing unit computing for large-scale data mining. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2018, 8, e1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S. Energy Estimates Across Layers of Computing: From Devices to Large-Scale Applications in Machine Learning for Natural Language Processing, Scientific Computing, and Cryptocurrency Mining. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE High Performance Extreme Computing Conference (HPEC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Hou, Q.; Qiu, C.; Mu, K.; Qi, Q.; Lu, Y. A cloud gaming system based on NVIDIA GRID GPU. In Proceedings of the 2014 13th International Symposium on Distributed Computing and Applications to Business, Engineering and Science. IEEE, 2014, pp. 73–77.

- Pathania, A.; Jiao, Q.; Prakash, A.; Mitra, T. Integrated CPU-GPU power management for 3D mobile games. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 51st Annual Design Automation Conference, 2014, pp. 1–6.

- Mills, N.; Mills, E. Taming the energy use of gaming computers. Energy Efficiency 2016, 9, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teske, D. NVIDIA Corporation: A Strategic Audit 2018.

- Moya, V.; Gonzalez, C.; Roca, J.; Fernandez, A.; Espasa, R. Shader performance analysis on a modern GPU architecture. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO’05). IEEE, 2005, pp. 10–pp.

- Kirk, D.; et al. NVIDIA CUDA software and GPU parallel computing architecture. In Proceedings of the ISMM, 2007, Vol. 7, pp. 103–104.

- Peddie, J. Mobile GPUs. In The History of the GPU-New Developments; Springer, 2023; pp. 101–185.

- Gera, P.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Hong, S.; George, V.; Luk, C.K. Performance characterisation and simulation of Intel’s integrated GPU architecture. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on Performance Analysis of Systems and Software (ISPASS). IEEE, 2018, pp. 139–148.

- Rajagopalan, G.; Thistle, J.; Polzin, W. The potential of gpu computing for design in rotcfd. In Proceedings of the AHS Technical Meeting on Aeromechanics Design for Transformative Vertical Flight, 2018.

- McClanahan, C. History and evolution of gpu architecture. A Survey Paper 2010, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, V.W.; Kim, C.; Chhugani, J.; Deisher, M.; Kim, D.; Nguyen, A.D.; Satish, N.; Smelyanskiy, M.; Chennupaty, S.; Hammarlund, P.; et al. Debunking the 100X GPU vs. CPU myth: an evaluation of throughput computing on CPU and GPU. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 37th annual international symposium on Computer architecture, 2010, pp. 451–460.

- Bergstrom, L.; Reppy, J. Nested data-parallelism on the GPU. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th ACM SIGPLAN international conference on Functional programming, 2012, pp. 247–258.

- Thomas, W.; Daruwala, R.D. Performance comparison of CPU and GPU on a discrete heterogeneous architecture. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Circuits, Systems, Communication and Information Technology Applications (CSCITA). IEEE, 2014, pp. 271–276.

- Svedin, M.; Chien, S.W.; Chikafa, G.; Jansson, N.; Podobas, A. Benchmarking the nvidia gpu lineage: From early k80 to modern a100 with asynchronous memory transfers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th International Symposium on Highly Efficient Accelerators and Reconfigurable Technologies, 2021, pp. 1–6.

- Bhargava, R.; Troester, K. Amd next generation" zen 4" core and 4 th gen amd epyc™ server cpus. IEEE Micro 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, M.D.; Marty, M.R. Amdahl’s law in the multicore era. Computer 2008, 41, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, J.; Bilbao, C.; Saez, J.C.; Prieto-Matias, M. Exploiting elasticity via os-runtime cooperation to improve cpu utilization in multicore systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 32nd Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-Based Processing (PDP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 35–43.

- Jones, C.; Gartung, P. CMSSW Scaling Limits on Many-Core Machines, 2023, [arXiv:hep-ex/2310.02872].

- Gorman, M.; Engineer, S.K.; Jambor, M. Optimizing Linux for AMD EPYC 7002 Series Processors with SUSE Linux Enterprise 15 SP1. SUSE Best Practices 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z.; Qiu, F.; Kaufman, A.; Yoakum-Stover, S. GPU cluster for high performance computing. In Proceedings of the SC’04: Proceedings of the 2004 ACM/IEEE conference on Supercomputing. IEEE, 2004, pp. 47–47.

- Kimm, H.; Paik, I.; Kimm, H. Performance comparision of tpu, gpu, cpu on google colaboratory over distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 14th International Symposium on Embedded Multicore/Many-core Systems-on-Chip (MCSoC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 312–319.

- Wang, Y.E.; Wei, G.Y.; Brooks, D. Benchmarking TPU, GPU, and CPU platforms for deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.10701 2019.

- Narayanan, D.; Shoeybi, M.; Casper, J.; LeGresley, P.; Patwary, M.; Korthikanti, V.; Vainbrand, D.; Kashinkunti, P.; Bernauer, J.; Catanzaro, B.; et al. Efficient large-scale language model training on gpu clusters using megatron-lm. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the international conference for high performance computing, networking, storage and analysis, 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Palacios, J.; Triska, J. A comparison of modern gpu and cpu architectures: And the common convergence of both. Oregon State University 2011.

- Haugen, P.; Myers, I.; Sadler, B.; Whidden, J. A Basic Overview of Commonly Encountered types of Random Access Memory (RAM).

- Kato, S.; McThrow, M.; Maltzahn, C.; Brandt, S. Gdev:{First-Class}{GPU} Resource Management in the Operating System. In Proceedings of the 2012 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 12), 2012, pp. 401–412.

- Kato, S.; Brandt, S.; Ishikawa, Y.; Rajkumar, R. Operating systems challenges for GPU resource management. In Proceedings of the Proc. of the International Workshop on Operating Systems Platforms for Embedded Real-Time Applications, 2011, pp. 23–32.

- Wen, Y.; O’Boyle, M.F. Merge or separate? Multi-job scheduling for OpenCL kernels on CPU/GPU platforms. In Proceedings of the general purpose GPUs; 2017; pp. 22–31.

- Tu, C.H.; Lin, T.S. Augmenting operating systems with OpenCL accelerators. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems (TODAES) 2019, 24, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chazapis, A.; Nikolaidis, F.; Marazakis, M.; Bilas, A. Running kubernetes workloads on HPC. In Proceedings of the International Conference on High Performance Computing. Springer, 2023, pp. 181–192.

- Weng, Q.; Yang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Tang, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, L. Beware of Fragmentation: Scheduling {GPU-Sharing} Workloads with Fragmentation Gradient Descent. In Proceedings of the 2023 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 23), 2023, pp. 995–1008.

- Kenny, J.; Knight, S. Kubernetes for HPC Administration. Technical report, Sandia National Lab.(SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States); Sandia …, 2021.

- Burns, B.; Grant, B.; Oppenheimer, D.; Brewer, E.; Wilkes, J. Borg, Omega, and Kubernetes: Lessons learned from three container-management systems over a decade. Queue 2016, 14, 70–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilapalli, V.K.; Murthy, A.C.; Douglas, C.; Agarwal, S.; Konar, M.; Evans, R.; Graves, T.; Lowe, J.; Shah, H.; Seth, S.; et al. Apache hadoop yarn: Yet another resource negotiator. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th annual Symposium on Cloud Computing, 2013, pp. 1–16.

- Kato, S.; Lakshmanan, K.; Rajkumar, R.; Ishikawa, Y.; et al. {TimeGraph}:{GPU} Scheduling for {Real-Time}{Multi-Tasking} Environments. In Proceedings of the 2011 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 11), 2011.

- Duato, J.; Pena, A.J.; Silla, F.; Mayo, R.; Quintana-Ortí, E.S. rCUDA: Reducing the number of GPU-based accelerators in high performance clusters. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on High Performance Computing & Simulation. IEEE, 2010, pp. 224–231.

- Agrawal, A.; Mueller, S.M.; Fleischer, B.M.; Sun, X.; Wang, N.; Choi, J.; Gopalakrishnan, K. DLFloat: A 16-b floating point format designed for deep learning training and inference. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th Symposium on Computer Arithmetic (ARITH). IEEE, 2019, pp. 92–95.

- Yeung, G.; Borowiec, D.; Friday, A.; Harper, R.; Garraghan, P. Towards {GPU} utilization prediction for cloud deep learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Cloud Computing (HotCloud 20), 2020.

- Jeon, M.; Venkataraman, S.; Phanishayee, A.; Qian, J.; Xiao, W.; Yang, F. Analysis of {Large-Scale}{Multi-Tenant}{GPU} clusters for {DNN} training workloads. In Proceedings of the 2019 USENIX Annual Technical Conference (USENIX ATC 19), 2019, pp. 947–960.

- Wu, G.; Greathouse, J.L.; Lyashevsky, A.; Jayasena, N.; Chiou, D. GPGPU performance and power estimation using machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 21st international symposium on high performance computer architecture (HPCA). IEEE, 2015, pp. 564–576.

- Boutros, A.; Nurvitadhi, E.; Ma, R.; Gribok, S.; Zhao, Z.; Hoe, J.C.; Betz, V.; Langhammer, M. Beyond peak performance: Comparing the real performance of AI-optimized FPGAs and GPUs. In Proceedings of the 2020 international conference on field-programmable technology (ICFPT). IEEE, 2020, pp. 10–19.

- Nordmark, R.; Olsén, T. A Ray Tracing Implementation Performance Comparison between the CPU and the GPU, 2022.

- Sun, Y.; Agostini, N.B.; Dong, S.; Kaeli, D. Summarizing CPU and GPU design trends with product data. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.11313 2019.

- Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Jin, L.; Xu, L.; Cao, Z.; Fan, P.; Kaeli, D.; Ma, S.; Guo, Y.; Yang, J. Priority-based PCIe scheduling for multi-tenant multi-GPU systems. IEEE Computer Architecture Letters 2019, 18, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, B. Enhancing Machine Learning Performance: The Role of GPU-Based AI Compute Architectures. J. Knowl. Learn. Sci. Technol. ISSN 2959 2024, 6386, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Buyya, R. Cluster computing at a glance. High Performance Cluster Computing: Architectures and Systems 1999, 1, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jararweh, Y.; Hariri, S. Power and performance management of gpus based cluster. International Journal of Cloud Applications and Computing (IJCAC) 2012, 2, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesolowski, L.; Acun, B.; Andrei, V.; Aziz, A.; Dankel, G.; Gregg, C.; Meng, X.; Meurillon, C.; Sheahan, D.; Tian, L.; et al. Datacenter-scale analysis and optimization of gpu machine learning workloads. IEEE Micro 2021, 41, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindratenko, V.V.; Enos, J.J.; Shi, G.; Showerman, M.T.; Arnold, G.W.; Stone, J.E.; Phillips, J.C.; Hwu, W.m. GPU clusters for high-performance computing. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Cluster Computing and Workshops. IEEE, 2009, pp. 1–8.

- Jayaram Subramanya, S.; Arfeen, D.; Lin, S.; Qiao, A.; Jia, Z.; Ganger, G.R. Sia: Heterogeneity-aware, goodput-optimized ML-cluster scheduling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2023, pp. 642–657.

- Xiao, W.; Bhardwaj, R.; Ramjee, R.; Sivathanu, M.; Kwatra, N.; Han, Z.; Patel, P.; Peng, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Gandiva: Introspective cluster scheduling for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 13th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 18), 2018, pp. 595–610.

- Narayanan, D.; Santhanam, K.; Kazhamiaka, F.; Phanishayee, A.; Zaharia, M. {Heterogeneity-Aware} cluster scheduling policies for deep learning workloads. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), 2020, pp. 481–498.

- Li, A.; Song, S.L.; Chen, J.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Tallent, N.R.; Barker, K.J. Evaluating modern gpu interconnect: Pcie, nvlink, nv-sli, nvswitch and gpudirect. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2019, 31, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousha, P.; Ramesh, B.; Suresh, K.K.; Chu, C.H.; Jain, A.; Sarkauskas, N.; Subramoni, H.; Panda, D.K. Designing a profiling and visualization tool for scalable and in-depth analysis of high-performance GPU clusters. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 26th International Conference on High Performance Computing, Data, and Analytics (HiPC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 93–102.

- Liao, C.; Sun, M.; Yang, Z.; Xie, J.; Chen, K.; Yuan, B.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z. LoHan: Low-Cost High-Performance Framework to Fine-Tune 100B Model on a Consumer GPU. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.06504 2024.

- Isaev, M.; McDonald, N.; Vuduc, R. Scaling infrastructure to support multi-trillion parameter LLM training. In Proceedings of the Architecture and System Support for Transformer Models (ASSYST@ ISCA 2023), 2023.

- Weng, Q.; Xiao, W.; Yu, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, C.; He, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Lin, W.; Ding, Y. {MLaaS} in the wild: Workload analysis and scheduling in {Large-Scale} heterogeneous {GPU} clusters. In Proceedings of the 19th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 22), 2022, pp. 945–960.

- Kumar, A.; Subramanian, K.; Venkataraman, S.; Akella, A. Doing more by doing less: how structured partial backpropagation improves deep learning clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd ACM International Workshop on Distributed Machine Learning, 2021, pp. 15–21.

- Hu, Q.; Sun, P.; Yan, S.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Characterization and prediction of deep learning workloads in large-scale gpu datacenters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Crankshaw, D.; Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Franklin, M.J.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Stoica, I. Clipper: A {Low-Latency} online prediction serving system. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 17), 2017, pp. 613–627.

- Peng, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Guo, C. Optimus: an efficient dynamic resource scheduler for deep learning clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirteenth EuroSys Conference, 2018, pp. 1–14.

- Yu, M.; Tian, Y.; Ji, B.; Wu, C.; Rajan, H.; Liu, J. Gadget: Online resource optimization for scheduling ring-all-reduce learning jobs. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2022-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2022, pp. 1569–1578.

- Qiao, A.; Choe, S.K.; Subramanya, S.J.; Neiswanger, W.; Ho, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ganger, G.R.; Xing, E.P. Pollux: Co-adaptive cluster scheduling for goodput-optimized deep learning. In Proceedings of the 15th {USENIX} Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation ({OSDI} 21), 2021.

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Octopus: SLO-aware progressive inference serving via deep reinforcement learning in multi-tenant edge cluster. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Service-Oriented Computing. Springer, 2023, pp. 242–258.

- Chaudhary, S.; Ramjee, R.; Sivathanu, M.; Kwatra, N.; Viswanatha, S. Balancing efficiency and fairness in heterogeneous GPU clusters for deep learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, 2020, pp. 1–16.

- Pinedo, M.L. Scheduling: Theory, Algorithms, and Systems, 6th ed.; Springer, 2022.

- Shao, J.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; An, B.; Cao, D. GPU scheduling for short tasks in private cloud. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Service-Oriented System Engineering (SOSE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 215–2155.

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Jin, X. Multi-resource interleaving for deep learning training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2022 Conference, 2022, pp. 428–440.

- Mohan, J.; Phanishayee, A.; Kulkarni, J.; Chidambaram, V. Looking beyond {GPUs} for {DNN} scheduling on {Multi-Tenant} clusters. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 22), 2022, pp. 579–596.

- Reuther, A.; Byun, C.; Arcand, W.; Bestor, D.; Bergeron, B.; Hubbell, M.; Jones, M.; Michaleas, P.; Prout, A.; Rosa, A.; et al. Scalable system scheduling for HPC and big data. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2018, 111, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Sun, P.; Gao, W.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Yan, S.; Luo, Y. Astraea: A fair deep learning scheduler for multi-tenant gpu clusters. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2021, 33, 2781–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Menache, I.; Kandula, S. Resource management with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 15th ACM workshop on hot topics in networks, 2016, pp. 50–56.

- Feitelson, D.G.; Rudolph, L.; Schwiegelshohn, U.; Sevcik, K.C.; Wong, P. Theory and practice in parallel job scheduling. In Proceedings of the Job Scheduling Strategies for Parallel Processing: IPPS’97 Processing Workshop Geneva, Switzerland, April 5, 1997 Proceedings 3. Springer, 1997, pp. 1–34.

- Gu, J.; Chowdhury, M.; Shin, K.G.; Zhu, Y.; Jeon, M.; Qian, J.; Liu, H.; Guo, C. Tiresias: A {GPU} cluster manager for distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the 16th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 19), 2019, pp. 485–500.

- Gao, W.; Ye, Z.; Sun, P.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Chronus: A novel deadline-aware scheduler for deep learning training jobs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Cloud Computing, 2021, pp. 609–623.

- Mahajan, K.; Balasubramanian, A.; Singhvi, A.; Venkataraman, S.; Akella, A.; Phanishayee, A.; Chawla, S. Themis: Fair and efficient {GPU} cluster scheduling. In Proceedings of the 17th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 20), 2020, pp. 289–304.

- Lin, C.Y.; Yeh, T.A.; Chou, J. DRAGON: A Dynamic Scheduling and Scaling Controller for Managing Distributed Deep Learning Jobs in Kubernetes Cluster. In Proceedings of the CLOSER, 2019, pp. 569–577.

- Bian, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, W.; You, Y. Online evolutionary batch size orchestration for scheduling deep learning workloads in GPU clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Wang, Q.; Shi, S.; Wang, C.; Chu, X. Communication contention aware scheduling of multiple deep learning training jobs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.10105 2020.

- Rajasekaran, S.; Ghobadi, M.; Akella, A. {CASSINI}:{Network-Aware} Job Scheduling in Machine Learning Clusters. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24), 2024, pp. 1403–1420.

- Yeung, G.; Borowiec, D.; Yang, R.; Friday, A.; Harper, R.; Garraghan, P. Horus: Interference-aware and prediction-based scheduling in deep learning systems. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2021, 33, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, S.; Kothapalli, K.; Purini, S. Share-a-GPU: Providing simple and effective time-sharing on GPUs. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 25th International Conference on High Performance Computing (HiPC). IEEE, 2018, pp. 294–303.

- Kubiak, W.; van de Velde, S. Scheduling deteriorating jobs to minimize makespan. Naval Research Logistics (NRL) 1998, 45, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokoto, E. Scheduling to minimize the makespan on identical parallel Machines: an LP-based algorithm. Investigacion Operative 1999, 97107. [Google Scholar]

- Kononov, A.; Gawiejnowicz, S. NP-hard cases in scheduling deteriorating jobs on dedicated machines. Journal of the Operational Research Society 2001, 52, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Guan, Y.; Qian, K.; Gao, J.; Xiao, W.; Dong, J.; Fu, B.; Cai, D.; Zhai, E. Crux: Gpu-efficient communication scheduling for deep learning training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2024 Conference, 2024, pp. 1–15.

- Zhong, J.; He, B. Kernelet: High-throughput GPU kernel executions with dynamic slicing and scheduling. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2013, 25, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, D.; Zhu, B.; Li, Z.; Zhuo, D.; Gonzalez, J.E.; Stoica, I. Fairness in serving large language models. In Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 24), 2024, pp. 965–988.

- Ghodsi, A.; Zaharia, M.; Hindman, B.; Konwinski, A.; Shenker, S.; Stoica, I. Dominant resource fairness: Fair allocation of multiple resource types. In Proceedings of the 8th USENIX symposium on networked systems design and implementation (NSDI 11), 2011.

- Sun, P.; Wen, Y.; Ta, N.B.D.; Yan, S. Towards distributed machine learning in shared clusters: A dynamically-partitioned approach. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–6.

- Mei, X.; Chu, X.; Liu, H.; Leung, Y.W.; Li, Z. Energy efficient real-time task scheduling on CPU-GPU hybrid clusters. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2017-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–9.

- Guerreiro, J.; Ilic, A.; Roma, N.; Tomas, P. GPGPU power modeling for multi-domain voltage-frequency scaling. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Symposium on High Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA). IEEE, 2018, pp. 789–800.

- Wang, Q.; Chu, X. GPGPU performance estimation with core and memory frequency scaling. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2020, 31, 2865–2881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, R.; Vogt, R.; Majumder, J.; Alam, A.; Burtscher, M.; Zong, Z. Effects of dynamic voltage and frequency scaling on a k20 gpu. In Proceedings of the 2013 42nd international conference on parallel processing. IEEE, 2013, pp. 826–833.

- Gu, D.; Xie, X.; Huang, G.; Jin, X.; Liu, X. Energy-Efficient GPU Clusters Scheduling for Deep Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.06381 2023.

- Filippini, F.; Ardagna, D.; Lattuada, M.; Amaldi, E.; Riedl, M.; Materka, K.; Skrzypek, P.; Ciavotta, M.; Magugliani, F.; Cicala, M. ANDREAS: Artificial intelligence traiNing scheDuler foR accElerAted resource clusterS. In Proceedings of the 2021 8th International Conference on Future Internet of Things and Cloud (FiCloud). IEEE, 2021, pp. 388–393.

- Sun, J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, J.; Shi, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, F.; Wang, Z. Helios: An efficient out-of-core GNN training system on terabyte-scale graphs with in-memory performance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00837 2023.

- ZHOU, Y.; ZENG, W.; ZHENG, Q.; LIU, Z.; CHEN, J. A Survey on Task Scheduling of CPU-GPU Heterogeneous Cluster. ZTE Communications 2024, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Stafman, L.; Or, A.; Freedman, M.J. Slaq: quality-driven scheduling for distributed machine learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2017 Symposium on Cloud Computing, 2017, pp. 390–404.

- Narayanan, D.; Kazhamiaka, F.; Abuzaid, F.; Kraft, P.; Agrawal, A.; Kandula, S.; Boyd, S.; Zaharia, M. Solving large-scale granular resource allocation problems efficiently with pop. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACM SIGOPS 28th Symposium on Operating Systems Principles, 2021, pp. 521–537.

- Tumanov, A.; Zhu, T.; Park, J.W.; Kozuch, M.A.; Harchol-Balter, M.; Ganger, G.R. TetriSched: global rescheduling with adaptive plan-ahead in dynamic heterogeneous clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eleventh European Conference on Computer Systems, 2016, pp. 1–16.

- Fiat, A.; Woeginger, G.J. Competitive analysis of algorithms. Online algorithms: The state of the art 2005, pp. 1–12.

- Günther, E.; Maurer, O.; Megow, N.; Wiese, A. A new approach to online scheduling: Approximating the optimal competitive ratio. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual ACM-SIAM Symposium on Discrete Algorithms. SIAM, 2013, pp. 118–128.

- Mitzenmacher, M. Scheduling with predictions and the price of misprediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.00732 2019.

- Han, Z.; Tan, H.; Jiang, S.H.C.; Fu, X.; Cao, W.; Lau, F.C. Scheduling placement-sensitive BSP jobs with inaccurate execution time estimation. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2020, pp. 1053–1062.

- Mitzenmacher, M.; Shahout, R. Queueing, Predictions, and LLMs: Challenges and Open Problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.07545 2025.

- Gao, W.; Sun, P.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Titan: a scheduler for foundation model fine-tuning workloads. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th Symposium on Cloud Computing, 2022, pp. 348–354.

- Zheng, P.; Pan, R.; Khan, T.; Venkataraman, S.; Akella, A. Shockwave: Fair and efficient cluster scheduling for dynamic adaptation in machine learning. In Proceedings of the 20th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 23), 2023, pp. 703–723.

- Zheng, H.; Xu, F.; Chen, L.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, F. Cynthia: Cost-efficient cloud resource provisioning for predictable distributed deep neural network training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 48th International Conference on Parallel Processing, 2019, pp. 1–11.

- Mu’alem, A.W.; Feitelson, D.G. Utilization, predictability, workloads, and user runtime estimates in scheduling the IBM SP2 with backfilling. IEEE transactions on parallel and distributed systems 2002, 12, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goponenko, A.V.; Lamar, K.; Allan, B.A.; Brandt, J.M.; Dechev, D. Job Scheduling for HPC Clusters: Constraint Programming vs. Backfilling Approaches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 18th ACM International Conference on Distributed and Event-based Systems, 2024, pp. 135–146.

- Kolker-Hicks, E.; Zhang, D.; Dai, D. A reinforcement learning based backfilling strategy for hpc batch jobs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SC’23 Workshops of the International Conference on High Performance Computing, Network, Storage, and Analysis, 2023, pp. 1316–1323.

- Kwok, Y.K.; Ahmad, I. Static scheduling algorithms for allocating directed task graphs to multiprocessors. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 1999, 31, 406–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, L.F.; Sakellariou, R.; Madeira, E.R. Dag scheduling using a lookahead variant of the heterogeneous earliest finish time algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2010 18th Euromicro conference on parallel, distributed and network-based processing. IEEE, 2010, pp. 27–34.

- Le, T.N.; Sun, X.; Chowdhury, M.; Liu, Z. Allox: compute allocation in hybrid clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Fifteenth European Conference on Computer Systems, 2020, pp. 1–16.

- Gu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Dai, H.; Chen, G.; Zhang, K.; Che, Y.; Huang, Y. Liquid: Intelligent resource estimation and network-efficient scheduling for deep learning jobs on distributed GPU clusters. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2021, 33, 2808–2820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Nomura, A.; Barton, R.; Zhang, H.; Matsuoka, S. Machine learning predictions for underestimation of job runtime on HPC system. In Proceedings of the Supercomputing Frontiers: 4th Asian Conference, SCFA 2018, Singapore, March 26-29, 2018, Proceedings 4. Springer International Publishing, 2018, pp. 179–198.

- Mao, H.; Schwarzkopf, M.; Venkatakrishnan, S.B.; Meng, Z.; Alizadeh, M. Learning scheduling algorithms for data processing clusters. In Proceedings of the ACM special interest group on data communication; 2019; pp. 270–288.

- Zhao, X.; Wu, C. Large-scale machine learning cluster scheduling via multi-agent graph reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management 2021, 19, 4962–4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Stoica, I. Efficient coflow scheduling without prior knowledge. ACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication Review 2015, 45, 393–406. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bhasi, V.M.; Singh, S.; Kesidis, G.; Kandemir, M.T.; Das, C.R. Gpu cluster scheduling for network-sensitive deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16492 2024.

- Gu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Han, Z.; Cheng, P.; Yang, F.; Huang, G.; Jin, X.; Liu, X. ElasticFlow: An elastic serverless training platform for distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 2, 2023, pp. 266–280.

- Even, G.; Halldórsson, M.M.; Kaplan, L.; Ron, D. Scheduling with conflicts: online and offline algorithms. Journal of scheduling 2009, 12, 199–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, C.O.; Pecero, J.E.; Bouvry, P. Scalable, low complexity, and fast greedy scheduling heuristics for highly heterogeneous distributed computing systems. The Journal of Supercomputing 2014, 67, 837–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; He, J.; Chen, K.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Z. Collaborative filtering and deep learning based recommendation system for cold start items. Expert systems with applications 2017, 69, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ma, K.; Yan, X.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Z.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, H.; Yu, F. Elastic deep learning in multi-tenant GPU clusters. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2021, 33, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Sivathanu, M.; Viswanatha, S.; Gulavani, B.; Nehme, R.; Agrawal, A.; Chen, C.; Kwatra, N.; Ramjee, R.; Sharma, P.; et al. Singularity: Planet-scale, preemptive and elastic scheduling of AI workloads. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.07848 2022.

- Saxena, V.; Jayaram, K.; Basu, S.; Sabharwal, Y.; Verma, A. Effective elastic scaling of deep learning workloads. In Proceedings of the 2020 28th International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–8.

- Gujarati, A.; Karimi, R.; Alzayat, S.; Hao, W.; Kaufmann, A.; Vigfusson, Y.; Mace, J. Serving {DNNs} like clockwork: Performance predictability from the bottom up. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), 2020, pp. 443–462.

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Shen, H. Job scheduling for large-scale machine learning clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on emerging Networking EXperiments and Technologies, 2020, pp. 108–120.

- Schrage, L. A proof of the optimality of the shortest remaining processing time discipline. Operations Research 1968, 16, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Kim, T.; Kim, S.; Shin, J.; Park, K. Elastic resource sharing for distributed deep learning. In Proceedings of the 18th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 21), 2021, pp. 721–739.

- Graham, R.L. Combinatorial scheduling theory. In Mathematics Today Twelve Informal Essays; Springer, 1978; pp. 183–211.

- Han, J.; Rafique, M.M.; Xu, L.; Butt, A.R.; Lim, S.H.; Vazhkudai, S.S. Marble: A multi-gpu aware job scheduler for deep learning on hpc systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 20th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster, Cloud and Internet Computing (CCGRID). IEEE, 2020, pp. 272–281.

- Baptiste, P. Polynomial time algorithms for minimizing the weighted number of late jobs on a single machine with equal processing times. Journal of Scheduling 1999, 2, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.L.; Layland, J.W. Scheduling algorithms for multiprogramming in a hard-real-time environment. Journal of the ACM (JACM) 1973, 20, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, Z. Online job scheduling in distributed machine learning clusters. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2018-IEEE Conference on Computer Communications. IEEE, 2018, pp. 495–503.

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S.; Sethi, R. The complexity of flowshop and jobshop scheduling. Mathematics of operations research 1976, 1, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.L. Bounds for certain multiprocessing anomalies. Bell system technical journal 1966, 45, 1563–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Liu, H.N.; Long, J.; Xiao, B. Competitive analysis of network load balancing. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 1997, 40, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Pang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, C.; Jiao, L.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Z. Online scheduling algorithm for heterogeneous distributed machine learning jobs. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2022, 11, 1514–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memeti, S.; Pllana, S.; Binotto, A.; Kołodziej, J.; Brandic, I. Using meta-heuristics and machine learning for software optimization of parallel computing systems: a systematic literature review. Computing 2019, 101, 893–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, A.B.; Jette, M.A.; Grondona, M. Slurm: Simple linux utility for resource management. In Proceedings of the Workshop on job scheduling strategies for parallel processing. Springer, 2003, pp. 44–60.

- Scully, Z.; Grosof, I.; Harchol-Balter, M. Optimal multiserver scheduling with unknown job sizes in heavy traffic. ACM SIGMETRICS Performance Evaluation Review 2020, 48, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, I.A.; Urvoy-Keller, G.; Biersack, E.W. Analysis of LAS scheduling for job size distributions with high variance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2003 ACM SIGMETRICS international conference on Measurement and modeling of computer systems, 2003, pp. 218–228.

- Sultana, A.; Chen, L.; Xu, F.; Yuan, X. E-LAS: Design and analysis of completion-time agnostic scheduling for distributed deep learning cluster. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 49th International Conference on Parallel Processing, 2020, pp. 1–11.

- Menear, K.; Nag, A.; Perr-Sauer, J.; Lunacek, M.; Potter, K.; Duplyakin, D. Mastering hpc runtime prediction: From observing patterns to a methodological approach. In Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing 2023: Computing for the Common Good; 2023; pp. 75–85.

- Luan, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, Z.; Dai, Y. SCHED2: Scheduling Deep Learning Training via Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–7.

- Qin, H.; Zawad, S.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhao, D.; Yan, F. Swift machine learning model serving scheduling: a region based reinforcement learning approach. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2019, pp. 1–23.

- Peng, Y.; Bao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.; Meng, C.; Lin, W. DL2: A deep learning-driven scheduler for deep learning clusters. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2021, 32, 1947–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Quan, W.; Wen, M.; Fang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhang, C.; Luo, L. Deep learning research and development platform: Characterizing and scheduling with qos guarantees on gpu clusters. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2019, 31, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Co-scheML: Interference-aware container co-scheduling scheme using machine learning application profiles for GPU clusters. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Cluster Computing (CLUSTER). IEEE, 2020, pp. 104–108.

- Duan, J.; Song, Z.; Miao, X.; Xi, X.; Lin, D.; Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Jia, Z. Parcae: Proactive,{Liveput-Optimized}{DNN} Training on Preemptible Instances. In Proceedings of the 21st USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation (NSDI 24), 2024, pp. 1121–1139.

- Yi, X.; Zhang, S.; Luo, Z.; Long, G.; Diao, L.; Wu, C.; Zheng, Z.; Yang, J.; Lin, W. Optimizing distributed training deployment in heterogeneous GPU clusters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on emerging Networking EXperiments and Technologies, 2020, pp. 93–107.

- Ryu, J.; Eo, J. Network contention-aware cluster scheduling with reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 29th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2742–2745.

- Fan, Y.; Lan, Z.; Childers, T.; Rich, P.; Allcock, W.; Papka, M.E. Deep reinforcement agent for scheduling in HPC. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS). IEEE, 2021, pp. 807–816.

- Hu, Q.; Zhang, M.; Sun, P.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, T. Lucid: A non-intrusive, scalable and interpretable scheduler for deep learning training jobs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 2, 2023, pp. 457–472.

- Zhou, P.; He, X.; Luo, S.; Yu, H.; Sun, G. JPAS: Job-progress-aware flow scheduling for deep learning clusters. Journal of Network and Computer Applications 2020, 158, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Ren, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, P.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y.; Lin, W.; Jia, Y. {AntMan}: Dynamic scaling on {GPU} clusters for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 20), 2020, pp. 533–548.

- Xie, L.; Zhai, J.; Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, P.; Yan, S. Elan: Towards generic and efficient elastic training for deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 40th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS). IEEE, 2020, pp. 78–88.

- Ding, J.; Ma, S.; Dong, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Wang, W.; Zheng, N.; Wei, F. Longnet: Scaling transformers to 1,000,000,000 tokens. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.02486 2023.

- Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Feng, D.; Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Yao, X.; Yu, D.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, F.; Dou, D. Heterps: Distributed deep learning with reinforcement learning based scheduling in heterogeneous environments. Future Generation Computer Systems 2023, 148, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, M.C.; Chou, J. DynamoML: Dynamic Resource Management Operators for Machine Learning Workloads. In Proceedings of the CLOSER, 2021, pp. 122–132.

- Narayanan, D.; Santhanam, K.; Phanishayee, A.; Zaharia, M. Accelerating deep learning workloads through efficient multi-model execution. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Workshop on Systems for Machine Learning, 2018, Vol. 20.

- Jayaram, K.; Muthusamy, V.; Dube, P.; Ishakian, V.; Wang, C.; Herta, B.; Boag, S.; Arroyo, D.; Tantawi, A.; Verma, A.; et al. FfDL: A flexible multi-tenant deep learning platform. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Middleware Conference, 2019, pp. 82–95.

- Narayanan, D.; Santhanam, K.; Kazhamiaka, F.; Phanishayee, A.; Zaharia, M. Analysis and exploitation of dynamic pricing in the public cloud for ml training. In Proceedings of the VLDB DISPA Workshop 2020, 2020.

- Wang, S.; Gonzalez, O.J.; Zhou, X.; Williams, T.; Friedman, B.D.; Havemann, M.; Woo, T. An efficient and non-intrusive GPU scheduling framework for deep learning training systems. In Proceedings of the SC20: International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis. IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–13.

- Yu, P.; Chowdhury, M. Fine-grained GPU sharing primitives for deep learning applications. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2020, 2, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Ye, Z.; Fu, T.; Luo, J.; Wei, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, T. Tear up the bubble boom: Lessons learned from a deep learning research and development cluster. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 40th International Conference on Computer Design (ICCD). IEEE, 2022, pp. 672–680.

- Cui, W.; Zhao, H.; Chen, Q.; Zheng, N.; Leng, J.; Zhao, J.; Song, Z.; Ma, T.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; et al. Enable simultaneous dnn services based on deterministic operator overlap and precise latency prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2021, pp. 1–15.

- Amaral, M.; Polo, J.; Carrera, D.; Seelam, S.; Steinder, M. Topology-aware gpu scheduling for learning workloads in cloud environments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis, 2017, pp. 1–12.

- Zhao, H.; Han, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, F.; Zhou, L.; Yang, M.; Lau, F.C.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; et al. {HiveD}: Sharing a {GPU} cluster for deep learning with guarantees. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX symposium on operating systems design and implementation (OSDI 20), 2020, pp. 515–532.

- Jeon, M.; Venkataraman, S.; Qian, J.; Phanishayee, A.; Xiao, W.; Yang, F. Multi-tenant GPU clusters for deep learning workloads: Analysis and implications. Technical report, Microsoft Research 2018.

- Li, W.; Chen, S.; Li, K.; Qi, H.; Xu, R.; Zhang, S. Efficient online scheduling for coflow-aware machine learning clusters. IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing 2020, 10, 2564–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.B.; Naghibijouybari, H.; Gupta, A.; Abu-Ghazaleh, N.; Marquez, A.; Barker, K. Spy in the gpu-box: Covert and side channel attacks on multi-gpu systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2023, pp. 1–13.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).