Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

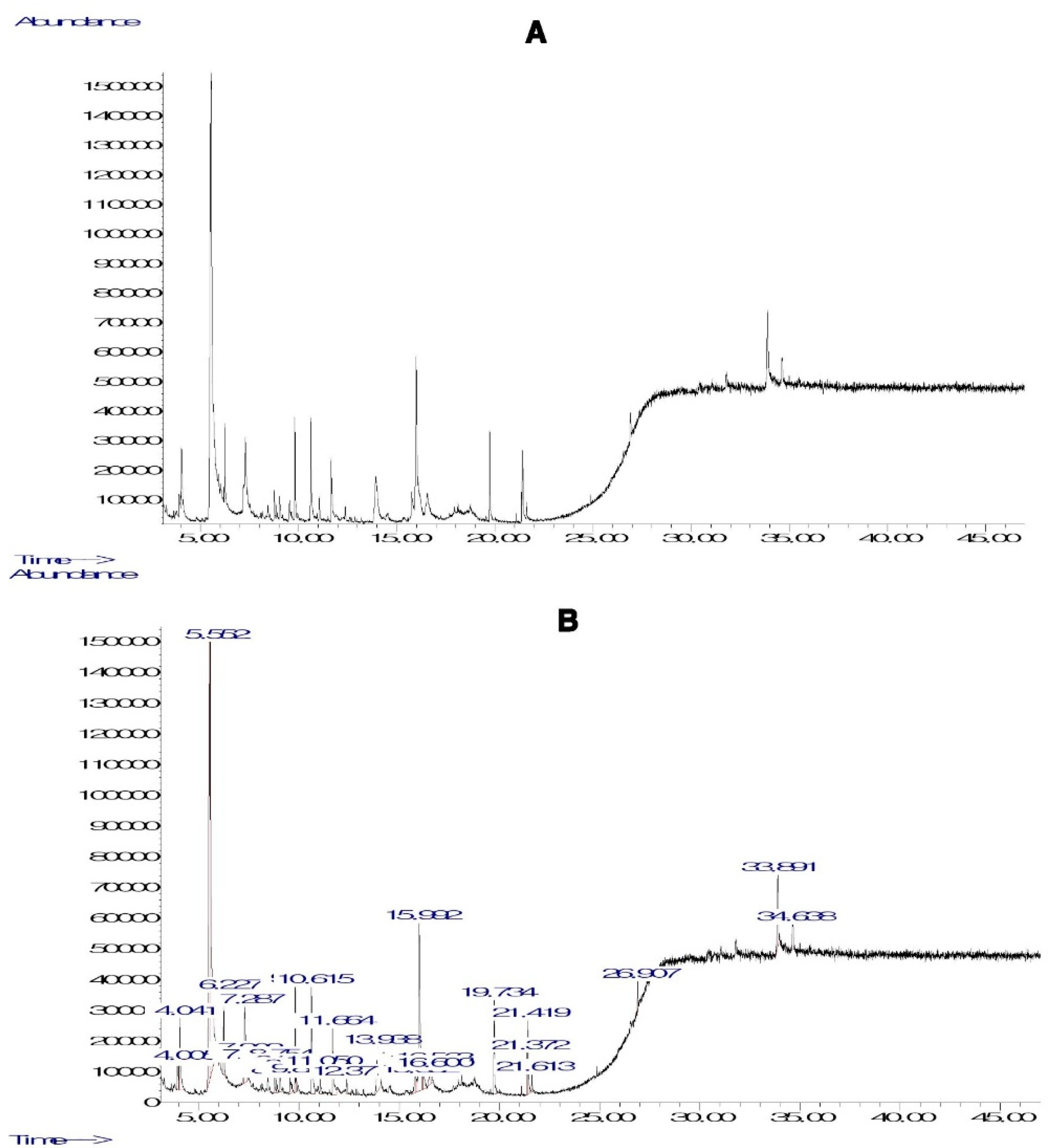

2.1. GC-MS Analysis and TP and TF Contents in PHF

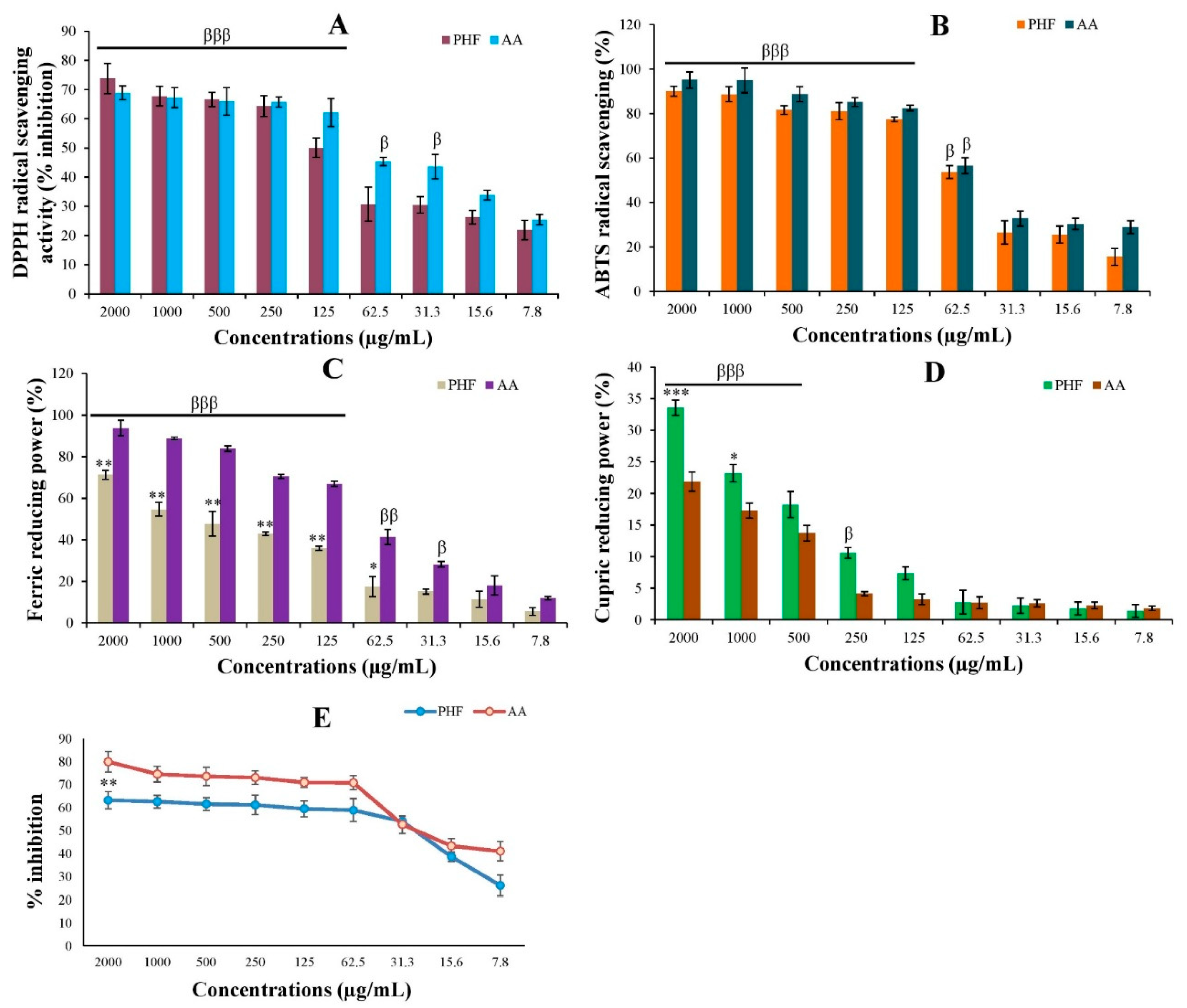

2.2. Antioxidant Activity of PHF

2.3. Protective Effects of PHF on the Detrimental Effects of CP in TM3 Cells

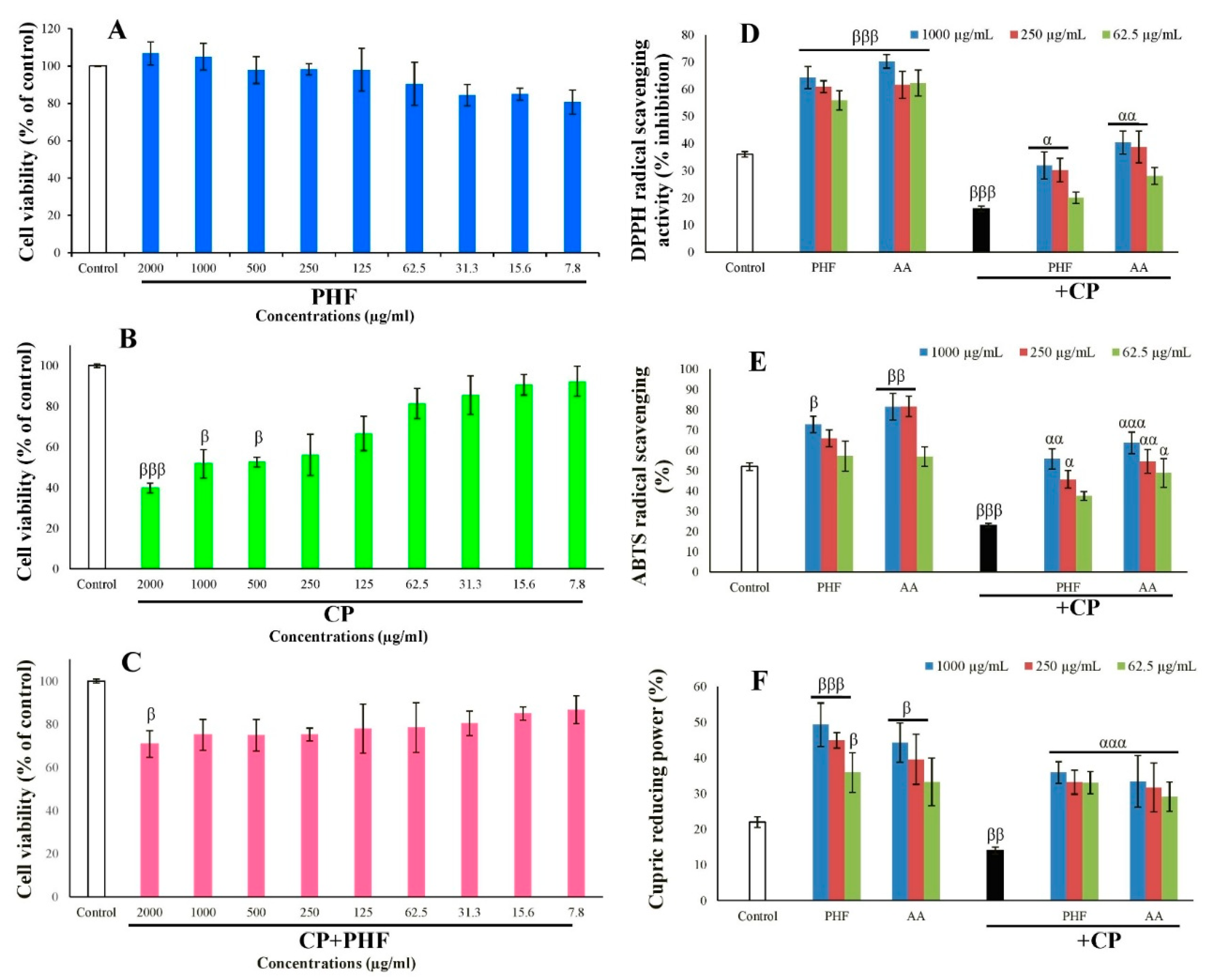

2.3.1. Cell Viability of TM3 Cells

2.3.2. Antioxidant Activities of PHF in TM3 Cells

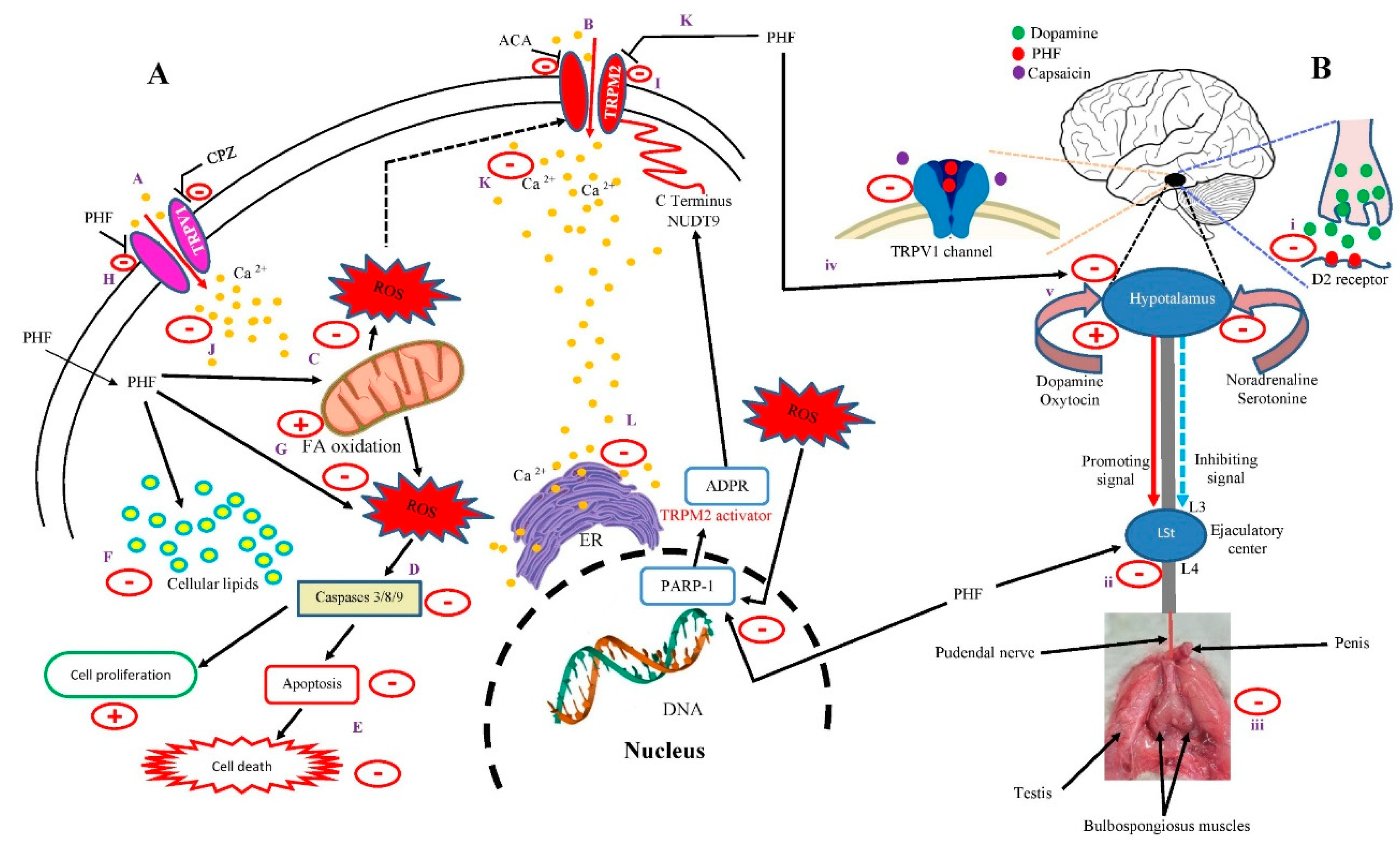

2.3.3. Apoptosis Through TRPV1 and TRPM2 Activation in TM3 Cells

2.3.4. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP) Through TRPV1 and TRPM2 Activation in TM3 Cells

2.3.5. ROS Generation Through TRPV1 and TRPM2 Activation in TM3 Cells

2.3.6. TM3 Cell Migration

2.4. Cytotoxicity Study of PHF

2.5. Fictive Ejaculation Study in Spinal Cord Transected Rats

2.5.1. Effects of Urethral and Penile Stimulations, and the Intravenous Injection of Saline Solution, CP, PHF, Dopamine, and Capsaicin on the Generator of Ejaculation in Spinal Rats

2.5.2. Effects of PHF on the Pro-Ejaculatory Activity of Dopamine and Capsaicin in Spinal Rats

2.6. Pharmacokinetics and ADME Properties of Compounds Found in PHF

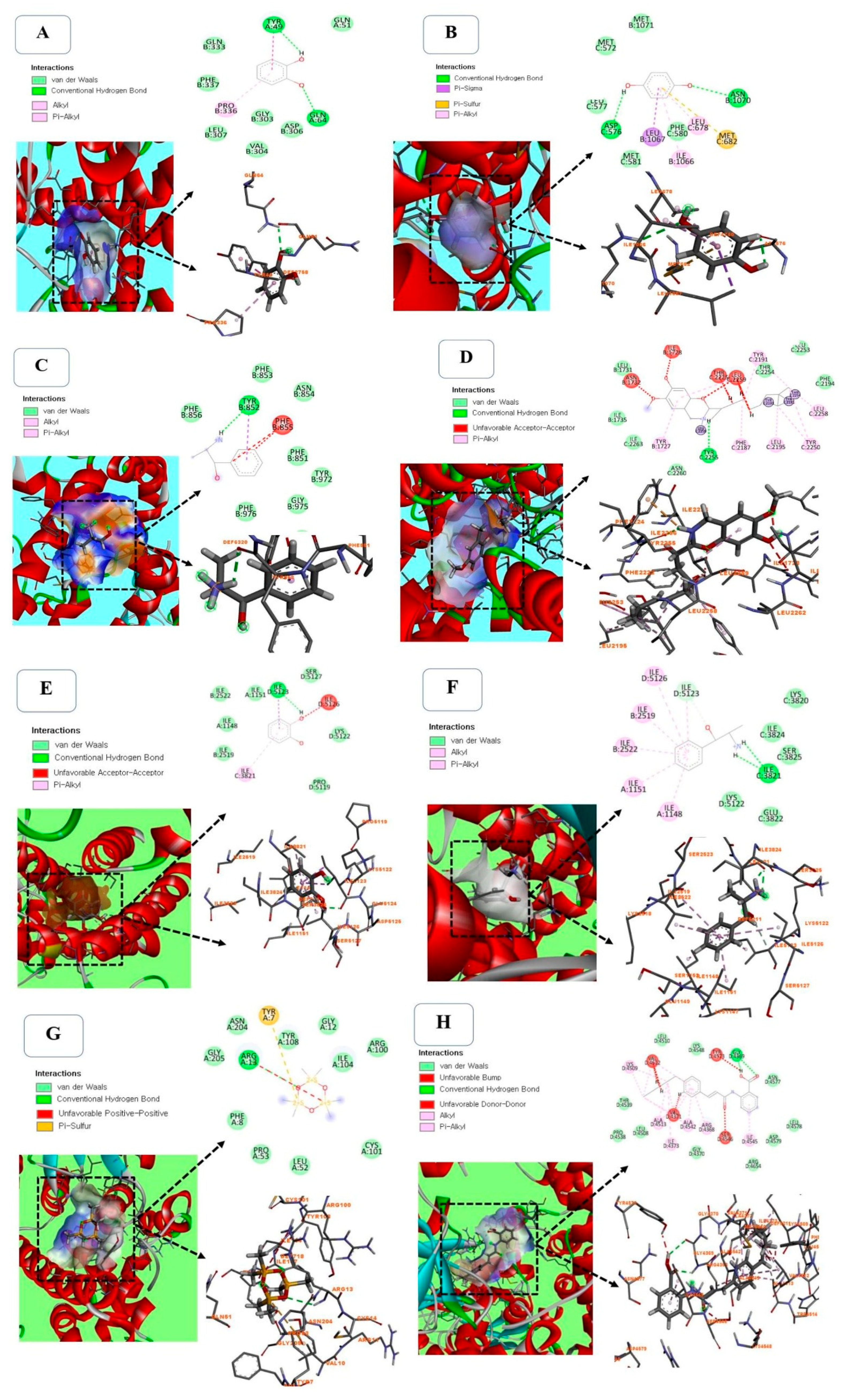

2.7. Molecular Docking Between Selected Compounds from PHF Against TRPV1 (PDB ID: 5IS0)

2.8. Molecular Docking Between Selected Compounds from PHF Against TRPM2 (PDB ID: 6PUS)

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of PHF, GC-MS Analysis, and Quantification of Total Phenolics (TP) and Total Flavonoids (TF)

3.2. In Vitro Studies

3.2.1. Antioxidant Study and Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation Inhibition

3.2.2. Cell Culture, Cell Viability, and Treatments

3.2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay: Hemolysis, HET-CAM Irritation Ex Vivo, and Cell Morphology

3.3. In Vivo Studies

3.3.1. Animals and Experimental Treatments

3.3.2. Surgical Procedure, and Activation and Recording of the Rhythmic Genital Motor Pattern of Ejaculation

3.4. In Silico Studies

3.4.1. Pharmacokinetics and ADME Properties

3.4.2. Molecular Docking

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABTS | (2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)) |

| ACA | N-(p-amylcinnamoyl)anthranilic acid |

| ADME | Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion |

| AO/EB | Acridine Orange/Ethidium Bromide |

| Bax | bcl-2-like protein 4 |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| CAP | Capsaicin |

| CHPx | Cumene hydroperoxide |

| CP | Cyclophosphamide |

| CPZ | Capsazepine |

| CUPRAC | Cupric reducing antioxidant capacity |

| DCF-DA | Diacetyldichlorofluorescein |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FRAP | Ferric-reducing antioxidant power |

| GC-MS | Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| HET-CAM | Hen's Egg Test-Chorioallantoic Membrane |

| MMP | Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-di-methylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| Na2CO3 | Sodium carbonate |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| NaOH | Sodium hydroxide |

| NFκB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PDB | Protein data bank |

| PHF | Polyherbal formulation |

| RBCs | Red blood cells |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| TF | Total flavonoid |

| TNFα | Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha |

| TP | Total phenolic |

| TPSA | Total polar surface area |

| TRPM2 | Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 |

| TRPV1 | Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 |

References

- Ahmed, A.R.; Hombal, S.M. Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan). A review on relevant pharmacology and clinical uses. A review on relevant pharmacology and clinical uses. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984, 11(6), 1115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elangovan, N.; Chiou, T.J.; Tzeng, W.F.; Sin-Tak, C. Cyclophosphamide treatment causes impairment of sperm and its fertilizing ability in mice. Toxicology 2006, 222, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masumoto, K.; Tsukimoto, M.; Kojima, S. Role of TRPM2 and TRPV1 cation channels in cellular responses to radiation-induced DNA damage. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1830(6), 3382–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazıroğlu, M. Activation of TRPM2 and TRPV1 Channels in dorsal root ganglion by NADPH oxidase and protein kinase C molecular pathways: a patch clamp study. J Mol Neurosci 2017, 61(3), 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, Y.; Nazıroğlu, M.; Özkaya, M.O. Low molecular weight heparin treatment reduced apoptosis and oxidative cytotoxicity in the thrombocytes of patients with recurrent pregnancy loss and thrombophilia: Involvements of TRPM2 and TRPV1 channels. J Obstet Gynaecol Res, 2023; 49, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noumi, E.; Zollo, P.H.A.; Lontsi, D. Aphrodisiac plants used in Cameroon. Fitoterapia 1998, 69, 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Watcho, P. , Deeh-Defo, P.B., Wankeu-Nya, M., Carro-Juarez, M., Nguelefack, T.B., Kamanyi, A., Mondia whitei (Periplocaceae) prevents and Guibourtia tessmannii (Caesalpiniaceae) facilitates fictive ejaculation in spinal male rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2013, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petnga, Y.B.T.; Momo, A.C.T.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Alumeti, D.M.; Fozin, G.R.B.; Deeh-Defo, P.B.; Ngadjui, E.; Watcho, P. Dracaena arborea (Dracaenaceae) increases sexual hormones and sperm parameters, lowers oxidative stress, and ameliorates testicular architecture in rats with 3 weeks of experimental varicocele. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2021, 1378112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wankeu-Nya, M.; Watcho, P.; Deeh-Defo, P.B.; Ngadjui, E.; Nguelefack, T.B.; Kamtchouing, P.; Kamanyi, A. Aqueous and ethanol extracts of Dracaena arborea (Wild) Link (Dracaenaceae) alleviate reproductive complications of diabetes mellitus in rats. Andrologia 2019, 51(10), e13381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, L.S. 1992. Ethnobotanical Uses of Plants in Nigeria. University of Benin Press, Benin City.

- Watcho, P.; Nchegang, B.; Nguelefack, T.; Kamanyi, A. Évaluation des effets prosexuels des extraits de Bridelia ferruginea chez le rat mâle naïf. Basic Clin. Androl 2010, 20, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeh, P.B.D.; Kim, M.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Naveen, K.V.; Wang, M.H. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, and cytotoxicity of the aqueous extracts of Dracaena arborea and Bridelia ferruginea: In vitro and in silico studies. S. Afr. J. Bot. 173, 46–5. [CrossRef]

- Deeh, P.B.D.; Asongu, E.; Wankeu, M.N.; Ngadjui, E.; Fazin, G.R.B.; Kemka, F.X.; Carro-Juarez, M.; Kamanyi, A.; Kamtchouing, P.; Watcho, P. Guibourtia tessmannii-induced fictive ejaculation in spinal male rat: involvement of D 1, D 2-like receptors. Pharm Biol 2017, 55, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deeh, P.B.D.; Watcho, P.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Ngadjui, E.; Usman, U.Z. The methanolic extract of Guibourtia tessmannii (caesalpiniaceae) and selenium modulate cytosolic calcium accumulation, apoptosis and oxidative stress in R2C tumour Leydig cells: Involvement of TRPV1 channels. Andrologia 2019, 51(3), e13216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcho, P.; Mpeck, I.M.; Deeh, P.B.D.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Ngadjui, E.; Bonsou, G.R.F.; Kamtchouing, P.; Kamanyi, A. Cyclophosphamide-induced reproductive toxicity: beneficial effects of Helichrysum odoratissimum (Asteraceae) in male Wistar rats. J Integr Med 2019, S2095, 4964: 30079–2. [CrossRef]

- Ajiboye, T.O.; Abdussalam, F.A.; Adeleye, A.O.; Iliasu, G.A.; Ariyo, F.A.; Adediran, Z.A.; Raji, K.O.; Raji, H.O. Bridelia ferruginea promotes reactive oxygen species detoxification in N-nitrosodiethylamine-treated rats. J Diet Suppl 2013, 10(3), 210–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmear, T.; Twilley, D.; Thipe, V.C.; Katti, K.V.; Mandiwana, V.; Kalombo, M.L.; Ray, S.S.; Rikhotso-Mbungela, R.; Bovilla, V.R.; Madhunapantula, S.; Langhanshova, L.; Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Fernandes, A.R.; Baptista, P.; Hlat,i S., Pretorius, J.; Lall, N. Anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative activity of Helichrysum odoratissimum Sweet. against lung cancer. S Afr J Bot 2024, 166, 525–538. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.I.; Kang, K.S. Function of capric acid in cyclophosphamide-induced intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, and barrier function in pigs. Sci Rep 2017, 7(1), 16530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoz-Camacho, R.; Rivera-Lazarín, A.L.; Vázquez-Guillen, J.M.; Caballero-Hernández, D.; Mendoza-Gamboa, E.; Martínez-Torres, A.C.; Rodríguez-Padilla, C. Cyclophosphamide and epirubicin induce high apoptosis in microglia cells while epirubicin provokes DNA damage and microglial activation at sub-lethal concentrations. EXCLI J 2022, 21, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althunibat, O.Y.; Abukhalil, M.H.; Jghef, M.M.; Alfwuaires, M.A.; Algefare, A.I.; Alsuwayt, B.; Alazragi, R.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Almuqati, A.F.; Karimulla, S.; Aladaileh, S.H. Hepatoprotective effect of taxifolin on cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in mice: Involvement of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. Biomol Biomed 2023, 23(4), 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; He, X.; Yang, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, W.; Guo, Z.; Hu, Y.; Liang, L.; Xie, W.; Xiong, H.; Wang, K.; Pang, M. TRPV1 induced apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells by activating calcineurin-NFAT2-p53 Signaling Pathway. Biomed Res Int 2019, 6712536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siregar, A.S.; Nyiramana, M.M.; Kim, E.J.; Shin, E.J.; Kim, C.W.; Lee, D.K.; Hong, S.G.; Han, J.; Kang, D. TRPV1 is associated with testicular apoptosis in mice. J Anim Reprod Biotechnol 2019, 34(4), 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildizhan, K.; Çinar, R.; Naziroğlu, M. The involvement of TRPM2 on the MPP+-induced oxidative neurotoxicity and apoptosis in hippocampal neurons from neonatal mice: protective role of resveratrol. Neurol Res 2022, 44(7), 636–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Li, M.; Wang, X. Capsaicin induces apoptosis and autophagy in human melanoma cells. Oncol Lett 2019, 17(6), 4827–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsou-Fozin, G.R.; Deeh-Defo.; Wankeu-Nya, M.; Ngadjui, E.; Kamanyi, A.; Watcho, P. Anti-androgenic, anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic effects of the aqueous and methanol extracts of Pterorhachis zenkeri (Meliaceae): Evidence from in vivo and in vitro studies. Andrologia 2020; 52(11), e13815. [CrossRef]

- Vimard, F.; Saucet, M.; Nicole, O.; Feuilloley, M.; Duval, D. Toxicity induced by cumene hydroperoxide in PC12 cells: protective role of thiol donors. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2011; 25(4), 205–1. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.Q.; Ma, X.W.; Dong, X.Y.; Tao, Z.R.; Lu, L.Z.; Zou, X.T. Effects of parental dietary linoleic acid on growth performance, antioxidant capacity, and lipid metabolism in domestic pigeons (Columba livia). Poult Sci 2020, 99(3), 1471–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awadallah, N.; Proctor, K.; Joseph, K.B.; Delay, E.R.; Delay, R.J. Cyclophosphamide has long-term effects on proliferation in olfactory epithelia. Chem Senses 2020, 45(2), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.; Yang, Y.T.; Wu, W.H.; Chueh, P.J.; Lin, M.H. Capsaicin attenuates cell migration via SIRT1 targeting and inhibition to enhance cortactin and β-catenin acetylation in bladder cancer cells. Am J Cancer Res 2019, 9(6), 1172–1182.

- Deeh, P.B.D.; Natesh, N.S.; Alagarsamy, K.; Arumugam, M.K.; Dasnamoorthy, R.; Sivaji, T.; Vishwakarma, V. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Pterorhachis zenkeri: characterization and evaluation of antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and androgenic properties in TM3 leydig cells exposed to cyclophosphamide. ADV TRADIT MED (ADTM) 2024b. [CrossRef]

- Olugbodi, J.O.; Uzunuigbe, E.O.; David, O.; Ojo, O.A. Effect of Glyphaea brevis twigs extract on cell viability, apoptosis induction and mitochondrial membrane potential in TM3 Leydig cells. Andrologia 2019, 51(7), e13312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæbø, I.P.; Bjørås, M.; Franzyk, H.; Helgesen, E.; Booth, J.A. Optimization of the hemolysis assay for the assessment of cytotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24(3), 2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.F.; Guan, G.; Wang, L. Hemocompatibility of surface modified silk fibroin materials: a review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2014, 38, 148–159. [Google Scholar]

- Soni, K.K.; Jeong, H.S.; Jang, S. Neurons for ejaculation and factors affecting ejaculation. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11(5), 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolen, L.M.; Allard, J.; Truitt, W.A.; McKenna, K.E. Central regulation of ejaculation. Physiol Behav 2004, 83(2), 203–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelayo, L.E.; Carro-Juárez, M.; Hernández-Hernández, F.; Trujillo, X.; Trujillo-Hernández, B.; Huerta, M. PNM-06 Capsaicin improves sexual behavior in male rat. J Sex Med 2017, 14(6), e384–e385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truitt, W.A.; Shipley, M.T.; Veening, J.G.; Coolen, L.M. Activation of a subset of lumbar spinothalamic neurons after copulatory behavior in male but not female rats. J Neurosci 2003, 23(1), 325–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, A.K.; Miegueu, P.; Bilanda, D.C.; Ngassam, M.F.N.; Watcho, P.; Djomeni, P.D.D.; Kamtchouing, P. Ejaculatory activities of Allanblackia floribunda stem bark in spinal male rats. Pharm Biol 2013, 51(8), 1014–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watcho, P.; Mbiakop, U.C.; Jeugo, H.G.A.; Wankeu, M.; Nguelefack, T.B.; Carro-Juarez, M.; Kamanyi, A. Delay of ejaculation induced by Bersama engleriana in nicotinamide/streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2014, 7S1, S603–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lipinski, C.A.; Lombardo, F.; Dominy, B.W.; Feeney, P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2001, 46, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hakeem, S.S.; Hassan, F.A.M.; Hifney, A.F.; Salem, S.H. Combating the causative agent of amoebic keratitis, Acanthamoeba castellanii, using Padina pavonica alcoholic extract: toxicokinetic and molecular docking approaches. Sci Rep 2024, 14(1), 13610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J. Prediction of blood-brain barrier permeation in drug discovery from in vivo, in vitro and in silico models. Drug Discov Today Tech 2004, 1(4), 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lu, J.; Sha, X.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, Z. TRPV1 regulates ApoE4-disrupted intracellular lipid homeostasis and decreases synaptic phagocytosis by microglia. Exp Mol Med 2023, 55(2), 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Zeng, M.; Peng, B.; Li, P.; Zhao, S. Transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) channels act as suppressors of the growth of glioma. Brain Res Bull 2024, 211, 110950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; He, N.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, D.; Wei, J.; Kang, W. Antimicrobial mechanism of hydroquinone. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2019, 189(4), 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M.; Levitt, J.; Pensabene, C.A. Hydroquinone therapy for post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation secondary to acne: not just prescribable by dermatologists. Acta Derm Venereol 2012, 92(3), 232–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, T.W. Hydroquinone for skin lightening: safety profile, duration of use and when should we stop? J Dermatolog Treat 2010, 21(5), 272–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byeon, S.E.; Yi, Y.S.; Lee, J.; Yang, W.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.; Hong, S.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, J.Y. Hydroquinone exhibits in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer activity in cancer cells and mice. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19(3), 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, K.; Wu, J.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Bi, L. Apoptosis induced by hydroquinone in bone marrow mononuclear cells in vitro. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi 2004, 22(3), 161–4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chepeleva, A.D.; Grobov, A.M.; Sirik, A.V.; Pliss, M. Antioxidant activity of hydroquinone in the oxidation of 1,4-substituted butadiene. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. 2021, 95, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, H.; Heizer, J.W.; Li, Y.; Chapman, K.; Ogden, C.A.; Andreasen, K.; Shapland, E.; Kucera, G.; Mogan, J.; Humann, J.; Lenz, L.L.; Morrison, A.D.; Perraud, A.L. Transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) ion channel is required for innate immunity against Listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108(28), 11578–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, N.; Kozai, D.; Kobayashi, R.; Ebert, M.; Mori, Y. Roles of TRPM2 in oxidative stress. Cell Calcium 2011, 50(3), 279–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertuğrul, A.; Özkaya, D.; Nazıroğlu, M. Curcumin attenuates hydroxychloroquine-mediated apoptosis and oxidative stress via the inhibition of TRPM2 channel signalling pathways in a retinal pigment epithelium cell line. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2023, 261(10), 2829–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieiralves, R.R.; Favorito, L.A. Dapoxetine and premature ejaculation. Int Braz J Urol 2023, 49(4), 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinelli, S.; Pascucci, T.; Bernardi, G.; Puglisi-Allegra, S.; Mercuri, N.B. Activation of TRPV1 in the VTA excites dopaminergic neurons and increases chemical- and noxious-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30(5), 864–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naziroğlu, M.; Uğuz, A.C.; Ismailoğlu, Ö.; Çiğ, B.; Özgü, C.; Borcak, M. Role of TRPM2 cation channels in dorsal root ganglion of rats after experimental spinal cord injury. Muscle Nerve 2013, 48(6), 945–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEC. 1986. Council Directive of 24 November 1986 on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes (86/609/EEC). OJEC. L358, 1–29.

- Benet, L.Z.; Hosey, C.M.; Ursu, O.; Oprea, T.I. BDDCS, the Rule of 5 and drug ability, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 101, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Retention Time (minute) | Area % | Molecular Weight | Molecular Formula | Name of the compound |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.041 | 2.97 | 88.11 | C4H8O2 | Oxirane, (methoxymethyl) |

| 5.789 | 16.33 | 154.25 | C10H18O | p-Menthone |

| 6.230 | 2.27 | 98.1 | C5H6O2 | 2-Hydroxycyclopent-2-en-1-one |

| 6.234 | 7.22 | 154.25 | C10H18O | Eucalyptol |

| 7.286 | 2.62 | 172.16 | C2H8N2O5S | Carbamimidic acid |

| 7.394 | 0.64 | 103.08 | C2H5N3O2 | Urea, n-methyl-n-nitroso- |

| 8.437 | 0.37 | 128.13 | C5H8N2O2 | Cycloglycylalanine |

| 8.754 | 0.82 | 126.2 | C7H14N2 | Cyclopentanone, dimethylhydrazone |

| 8.883 | 0.45 | 112.17 | C6H12N2 | Methanamine, n-(1-methyl-2-pyrrolidinylidene)- |

| 9.035 | 0.88 | 129.24 | C8H19N | 2-Heptanamine, 5-methyl- |

| 9.544 | 0.85 | 114.1 | C4H6N2O2 | Maleamide |

| 9.693 | 0.97 | 114.19 | C6H14N2 | N1,N1-dimethyl-n2-isopropylformamidine |

| 9.812 | 1.97 | 98.1 | C5H6O2 | 2(3h)-Furanone, 5-methyl- |

| 9.856 | 0.37 | 144.12 | C6H8O4 | 4h-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- |

| 10.613 | 3.96 | 110.11 | C6H6O2 | Pyrocatechol |

| 11.052 | 0.82 | 190.27 | C10H10N2S | N-(2-thienylmethyl)-2-pyridinamine |

| 11.663 | 3.08 | 110.11 | C6H6O2 | Hydroquinone |

| 12.375 | 0.39 | 374.38 | C12H18N6O6S | 5'-O-[n,n-dimethylsulfamoyl]adenosine |

| 12.981 | 2.38 | 151.21 | C9H13NO | (-)-Norephedrine |

| 13.940 | 4.31 | 104.1 | C4H8O3 | Tetrahydro-3,4-furandiol |

| 15.766 | 1.40 | 122.16 | C8H10O | 4,5,6,6a-Tetrahydro-2(1h)-pentalenone |

| 15.995 | 11.26 | 192,17 | C7H12O6 | Quinic acid |

| 16.148 | 0.68 | 343.29 | C14H17NO9 | Tetraacetyl-d-xylonic nitrile |

| 16.189 | 1.50 | 179.22 | C10H13NO2 | Alpha-methyl-DL-phenylalanine |

| 16.240 | 1.22 | 122.12 | C4H10O4 | Erythritol |

| 16.562 | 1.09 | 343.29 | C14H17NO9 | Tetraacetyl-d-xylonic nitrile |

| 16.600 | 0.36 | 102.13 | C5H10O2 | 2H-pyran-3-ol, tetrahydro- |

| 19.736 | 2.36 | 256.42 | C16H32O2 | Palmitic acid |

| 21.371 | 0.84 | 308.5 | C20H36O2 | Eicosadienoic acid |

| 21.684 | 0.75 | 342.9 | C20H35ClO2 | Linoleic acid |

| 21.987 | 2.97 | 282.5 | C18H34O2 | Oleic acid |

| 22.613 | 0.42 | 283.957 | C8H4FeO8 | (Tetrahydroxycyclopentadienone)tricarbonyliron(0) |

| 25.582 | 12.86 | 98.1 | C5H6O2 | 5-Methyl-2(5H)-furanone |

| 35.412 | 8.62 | 152.23 | C10H16O | Pulegone |

| Treatments | HET-CAM (Average) 0 s 30 s 2 min 5 min |

Irritation score | Irritation category |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaOH (0.1M), positive control | 0 5 8 9 | 22 | Strong irritation |

| 0.9% NaCl, negative control | 0 0 0 0 | 0 | Non-irritant |

| PHF (2000 µg/mL) | 0 0 0 0 | 0 | Non-irritant |

| Botanical name | Vernacular name | Common name | Part used | Family | Voucher specimen number | Percentage used | Period of collection | Region of collection (GPS coordinates) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mondia whitei | Limte | White's ginger | roots | Apocynaceae | 42920/HNC | 20 | April 2023 | Bafoussam (5° 28' 39.90" N 10° 25' 3.32" E) |

| Dracaena arborea | Keubgouh | African Dragon Tree | stem barks | Asparagaceae | 25361/SFR/Cam | 20 | April 2023 | Dschang (5° 26' 38.29" N, 10° 3' 11.95" E) |

| Bridelia ferruginea | Kimi | - | stem barks | Euphorbiaceae | 42920/HNC | 20 | April 2023 | Bangangté (5° 14' 60.00" N, 10° 49' 59.99" E) |

| Guibourtia tessmannii | Essingang | Bubinga | stem barks | Fabaceae | 1037/SRFCA | 20 | April 2023 | Ngoumou (3° 53' 45.25" N, 12° 20' 47.00"E) |

| Helichrysum odoratissimum | Mbantchuet | Imphepho | whole plant | Asteraceae | HNC 1640 | 20 | April 2023 | Dschang (5° 26' 38.29" N, 10° 3' 11.95" E) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).