Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Hierarchical Clustering

Cluster Validation and Optimal Number of Clusters

- Silhouette Score: This measures how similar an object is to its own cluster compared to other clusters, with values ranging from -1 to 1. Higher values indicate better-defined clusters with greater separation from neighboring clusters [28,41,42,43]. Mathematically, the Silhouette Score s(i) is given by:where is the average intra-cluster distance for amino acid , and is the average nearest-cluster distance. Values range from (poor clustering) to (excellent clustering).

- Calinski-Harabasz Index (Variance Ratio Criterion): This measures the ratio of between-cluster dispersion to within-cluster dispersion, with higher values indicating better clustering solutions with dense, well-separated clusters [44]. By standard definition, the Calinski-Harabasz Index (CH) is given by:where is the total number of amino acids. Higher values indicate better-defined clusters.

- Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI): This measures the average similarity between each cluster and its most similar cluster serving as an internal evaluation scheme that relies on inherent dataset features, with lower values indicating better clustering with greater separation between clusters [45]. By standard definition, the Davies-Boulding Index is computed as follows:where,

- 4.

- Inertia (Within-Cluster Sum of Squares): This measures the compactness of clusters by summing the squared distances of samples to their nearest cluster center, with lower values indicating more compact clusters [14]. Mathematically, Inertia is represented by:representing the within-cluster sum of squared distances to the centroid ().

- 5.

- Consensus Clustering for Stability Assessment

- For each of 100 iterations, randomly sample 80% of the amino acids.

- Apply hierarchical clustering to the subsampled data using the previously identified optimal linkage method and distance metric.

- Record the clustering assignments for the subsampled amino acids.

- Construct a consensus matrix where each element (i,j) shows the proportion of times amino acids i and j were clustered together across iterations.

- Analyze the matrix to identify stable clusters and evaluate the overall stability of the clustering solution.

- 6.

- Cophenetic Correlation: Cophenetic Correlation, often referred to as the Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient, is a statistical measure used to evaluate how faithfully a dendrogram (a hierarchical clustering tree) preserves the pairwise distances between the original data points [47]. It is widely used in biostatistics and other fields involving clustering, such as taxonomy or consumer behavior analysis, to assess the quality of clustering solutions. The coefficient compares the original distances or dissimilarities between data points with the cophenetic distances, which are defined as the height of the node (or link) at which two points are first joined together in the dendrogram [47]. A value closer to 1 indicates a high degree of similarity between the original distances and the dendrogram structure, suggesting a better representation of the data's inherent relationships. The Cophenetic Correlation Coefficient (c) is calculated as the linear correlation coefficient between the original distances and the cophenetic distances. Let:

Algorithm Comparison

Visualization

Results

Optimal Linkage Method Selection

Cluster Validation and Optimal Number of Clusters

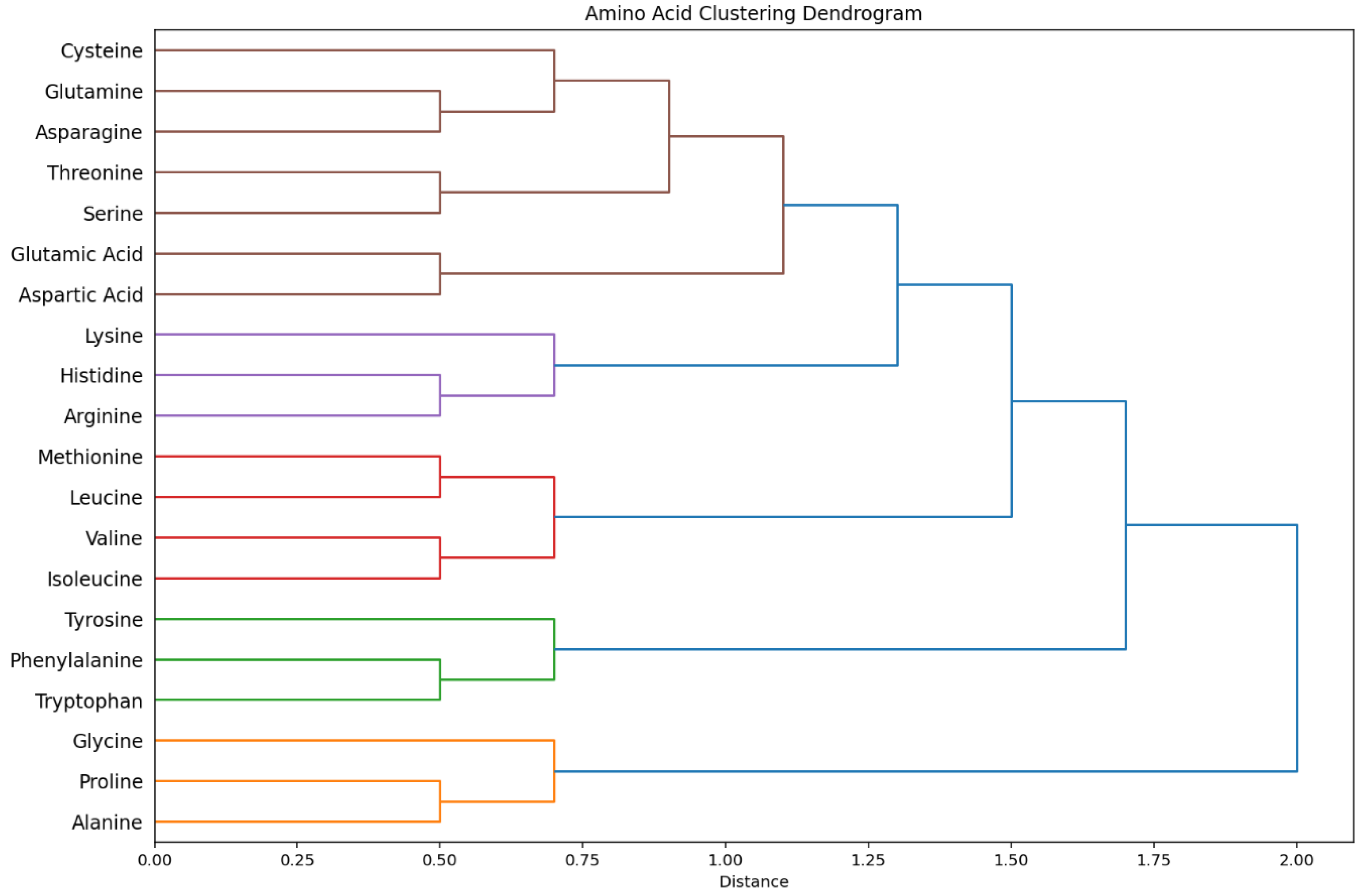

Hierarchical Cluster Structure

Consensus Clustering Results

Algorithm Comparison

Discussion

Comparison with Existing Amino Acid Classifications

Novel Associations and Insights

Implications for Protein Structure and Function

Methodological Strengths and Limitations

Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kakraba, S., A Hierarchical Graph for Nucleotide Binding Domain 2. 2015, East Tennessee State University: United States -- Tennessee. p. 61.

- Kakraba, S. and D. Knisley, A graph-theoretic model of single point mutations in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator. JOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN BIOTECHNOLOGY, 2016. 6(1): P. 780-786. [CrossRef]

- Netsey, E.K.; et al., A Mathematical Graph-Theoretic Model of Single Point Mutations Associated with Sickle Cell Anemia Disease. JOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN BIOTECHNOLOGY, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Netsey, E.K.; et al., Structural and functional impacts of SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein mutations: Insights from predictive modeling and analytics (preprint). JMIR Preprints, 2025.

- Netsey, E.K.; et al., A Mathematical Graph-Theoretic Model of Single Point Mutations Associated with Sickle Cell Anemia Disease. JOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN BIOTECHNOLOGY, 2021. 9: P. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S., Drugs That Protect Against Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. 2021, University of Arkansas at Little Rock: United States -- Arkansas. p. 209.

- Kakraba, S.; et al., A Novel Microtubule-Binding Drug Attenuates and Reverses Protein Aggregation in Animal Models of Alzheimer's Disease. Front Mol Neurosci, 2019. 12: P. 310. [CrossRef]

- Bowroju, S.K.; et al., Design and Synthesis of Novel Hybrid 8-Hydroxy Quinoline-Indole Derivatives as Inhibitors of Aβ Self-Aggregation and Metal Chelation-Induced Aβ Aggregation. Molecules, 2020. 25(16). [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M.; et al., Aggregate Interactome Based on Protein Cross-linking Interfaces Predicts Drug Targets to Limit Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. iScience, 2019. 20: P. 248-264. [CrossRef]

- Ayyadevara, S.; et al., Aspirin-Mediated Acetylation Protects Against Multiple Neurodegenerative Pathologies by Impeding Protein Aggregation. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2017. 27(17): P. 1383-1396. [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S.; et al., Thiadiazolidinone (TDZD) Analogs Inhibit Aggregation-Mediated Pathology in Diverse Neurodegeneration Models, and Extend C. elegans Life- and Healthspan. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023. 16(10). [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, B. and B. Schwikowski, Consensus Clustering for Robust Bioinformatics Analysis. bioRxiv, 2024: P. 2024.03.21.586064.

- Venkatarajan, M.S. and W. Braun, New quantitative descriptors of amino acids based on multidimensional scaling of a large number of physical–chemical properties. Molecular modeling annual, 2001. 7(12): P. 445-453. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M. and K. Ye, Determining the number of clusters using the weighted gap statistic. Biometrics, 2007. 63(4): P. 1031-7. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; et al. Optimizing Parkinson’s Disease Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Data Aggregation Methods Using Multiple Voice Recordings via an Automated Artificial Intelligence Pipeline. Data, 2025. 10. [CrossRef]

- Kakraba, S.; et al., AI-enhanced multi-algorithm R shiny app for Predictive Modeling and analytics- A case study of Alzheimer’s disease diagnostics (preprint). JMIR Preprints, 2024.

- Tibshirani, R., G. Walther, and T. Hastie, Estimating the Number of Clusters in a Data Set Via the Gap Statistic. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology, 2001. 63(2): P. 411-423.

- Yue, S.; et al., Extension of the gap statistics index to fuzzy clustering. Soft Computing, 2013. 17(10): P. 1833-1846. [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.K.; et al., Determining the optimal number of clusters by Enhanced Gap Statistic in K-mean algorithm. Egyptian Informatics Journal, 2024. 27: P. 100504. [CrossRef]

- Venkatarajan, M. and W. Braun, New quantitative descriptors of amino acids based on multidimensional scaling of a large number of physical-chemical properties. Journal of Molecular Modeling, 2001. 7(12): P. 445-453. [CrossRef]

- Cosar, B.; et al., SARS-CoV-2 Mutations and their Viral Variants. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev, 2022. 63: P. 10-22. [CrossRef]

- Éliás, S.; et al., Prediction of polyspecificity from antibody sequence data by machine learning. Frontiers in Bioinformatics, 2024. 3.

- McKenna, A. and S. Dubey, Machine learning based predictive model for the analysis of sequence activity relationships using protein spectra and protein descriptors. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 2022. 128: P. 104016. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; et al., Methods to analyze genetic alterations in cancer to identify therapeutic peptide vaccines and kits therefore, in US Patent, Uspto, Editor. 2019, MEDGENOME Inc.

- Jain, S.S., Predictive Modelling of Directed Evolution for De-Novo Design of Solid Binding Peptides (Doctoral dissertation), in ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. 2021.

- Yang, Z.; et al., Optimizing Parkinson’s Disease Prediction: A Comparative Analysis of Data Aggregation Methods Using Multiple Voice Recordings via an Automated Artificial Intelligence Pipeline. Data, 2025. 10(1): P. 4. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M. and K. Ye, Determining the Number of Clusters Using the Weighted Gap Statistic. Biometrics, 2007. 63. [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J., Silhouettes: A graphical aid to the interpretation and validation of cluster analysis. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 1987. 20: P. 53-65. [CrossRef]

- Pommié, C.; et al., IMGT standardized criteria for statistical analysis of immunoglobulin V-REGION amino acid properties. J Mol Recognit, 2004. 17(1): P. 17-32. [CrossRef]

- Kyte, J. and R.F. Doolittle, A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1982. 157(1): P. 105-132. [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, J., Lifting the crown—Citation z-score. Journal of Informetrics, 2007. 1(2): P. 145-154.

- Anderson, D.F., A Proof of the Global Attractor Conjecture in the Single Linkage Class Case. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics, 2011. 71(4): P. 1487-1508. [CrossRef]

- Stuetzle, W. and R. and Nugent, A Generalized Single Linkage Method for Estimating the Cluster Tree of a Density. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 2010. 19(2): P. 397-418. [CrossRef]

- Seifoddini, H.K., Single linkage versus average linkage clustering in machine cells formation applications. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 1989. 16(3): P. 419-426. [CrossRef]

- Vijaya, S. Sharma, and N. Batra. Comparative Study of Single Linkage, Complete Linkage, and Ward Method of Agglomerative Clustering. in 2019 International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data, Cloud and Parallel Computing (COMITCon). 2019.

- Gere, A., Recommendations for validating hierarchical clustering in consumer sensory projects. Curr Res Food Sci, 2023. 6: P. 100522. [CrossRef]

- Strauss, T. and M.J. von Maltitz, Generalising Ward's Method for Use with Manhattan Distances. PLoS ONE, 2017. 12(1): P. e0168288.

- Harris, C.R.; et al., Array programming with NumPy. Nature, 2020. 585(7825): P. 357-362. [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; et al., Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2011. 12: P. 2825-2830.

- Van Rossum, G.D., Jr., Python Reference Manual. 1995: Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica.

- Kawashima, S. and M. Kanehisa, AAindex: Amino Acid index database. Nucleic Acids Research, 2000. 28(1): P. 374-374. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, L. and P.J. Rousseeuw, Finding groups in data. 99 ed. Probability & Mathematical Statistics S. 1990, Nashville, TN: John Wiley & Sons. 368.

- Wolf, L.J., E. Knaap, and S. Rey, Geosilhouettes: Geographical measures of cluster fit. Environment and Planning B, 2019. 48(3): P. 521-539. [CrossRef]

- Ikotun, A.M., F. Habyarimana, and A.E. Ezugwu, Cluster validity indices for automatic clustering: A comprehensive review. Heliyon, 2025. 11(2): P. e41953. [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.J. and D. Dueck, Clustering by passing messages between data points. Science, 2007. 315(5814): P. 972-6. [CrossRef]

- Monti, S.; et al., Consensus Clustering: A Resampling-Based Method for Class Discovery and Visualization of Gene Expression Microarray Data. Machine Learning, 2003. 52(1): P. 91-118. [CrossRef]

- Saraçli, S., N. Doğan, and İ. Doğan, Comparison of hierarchical cluster analysis methods by cophenetic correlation. Journal of Inequalities and Applications, 2013. 2013(1): P. 203. [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L. and D.W. Bouldin, A cluster separation measure. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, 1979. 1(2): P. 224-7.

- Virtanen, P.; et al., SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nature Methods, 2020. 17(3): P. 261-272.

- Burley, S.K. and G.A. Petsko, Amino-aromatic interactions in proteins. FEBS Lett, 1986. 203(2): P. 139-43. [CrossRef]

- Breimann, S.; et al., AAontology: An Ontology of Amino Acid Scales for Interpretable Machine Learning. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2024. 436(19): P. 168717. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.R.; et al., PROFEAT: A web server for computing structural and physicochemical features of proteins and peptides from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res, 2006. 34(Web Server issue): P. W32-7. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; et al., Cation-π interactions in protein-ligand binding: Theory and data-mining reveal different roles for lysine and arginine. Chem Sci, 2018. 9(10): P. 2655-2665. [CrossRef]

- Aledo, J.C., Methionine in proteins: The Cinderella of the proteinogenic amino acids. Protein Sci, 2019. 28(10): P. 1785-1796. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Tamayo, J.C.; et al., Analysis of the interactions of sulfur-containing amino acids in membrane proteins. Protein Sci, 2016. 25(8): P. 1517-24. [CrossRef]

- Poole, L.B., The basics of thiols and cysteines in redox biology and chemistry. Free Radic Biol Med, 2015. 80: P. 148-57. [CrossRef]

- Högel, P.; et al., Glycine Perturbs Local and Global Conformational Flexibility of a Transmembrane Helix. Biochemistry, 2018. 57(8): P. 1326-1337. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, P. and D. Pal, The interrelationships of side-chain and main-chain conformations in proteins. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology, 2001. 76(1): P. 1-102. [CrossRef]

- Röder, K., The effects of glycine to alanine mutations on the structure of GPO collagen model peptides. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2022. 24(3): P. 1610-1619. [CrossRef]

| Method | Cophenetic correlation |

|---|---|

| Ward | 0.695 |

| Average | 0.847 |

| Complete | 0.616 |

| Single | 0.724 |

| Number of Clusters | Silhouette Score | Calinski-Harabasz Index | Davies-Bouldin Index | Inertia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 0.573 | 21.45 | 0.82 | 1245.71 |

| 3 | 0.492 | 18.93 | 1.04 | 893.24 |

| 4 | 0.431 | 16.75 | 1.27 | 702.58 |

| 5 | 0.397 | 14.62 | 1.49 | 582.13 |

| Metric | Value | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Average Consensus | 0.682 | Moderate overall cluster stability |

| Maximum Pair Consensus | 0.912 | Arginine-Histidine (cation-π interactions) |

| Minimum Pair Consensus | 0.083 | Glycine-Tryptophan (structural opposites) |

| High-Stability Clusters | 0.85+ | Aromatic triad, branched aliphatics |

| Low-Stability Pairs | <0.30 | Glycine/Proline with most residues |

| Algorithm | Silhouette | Calinski-Harabasz | Davies-Bouldin | Biological Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agglomerative | 0.573 | 21.45 | 0.82 | Excellent (hierarchical structure) |

| KMeans | 0.548 | 19.83 | 0.91 | Good (rigid spherical clusters) |

| DBSCAN | 0.412 | 15.27 | 1.35 | Poor (density challenges) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).