Submitted:

03 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

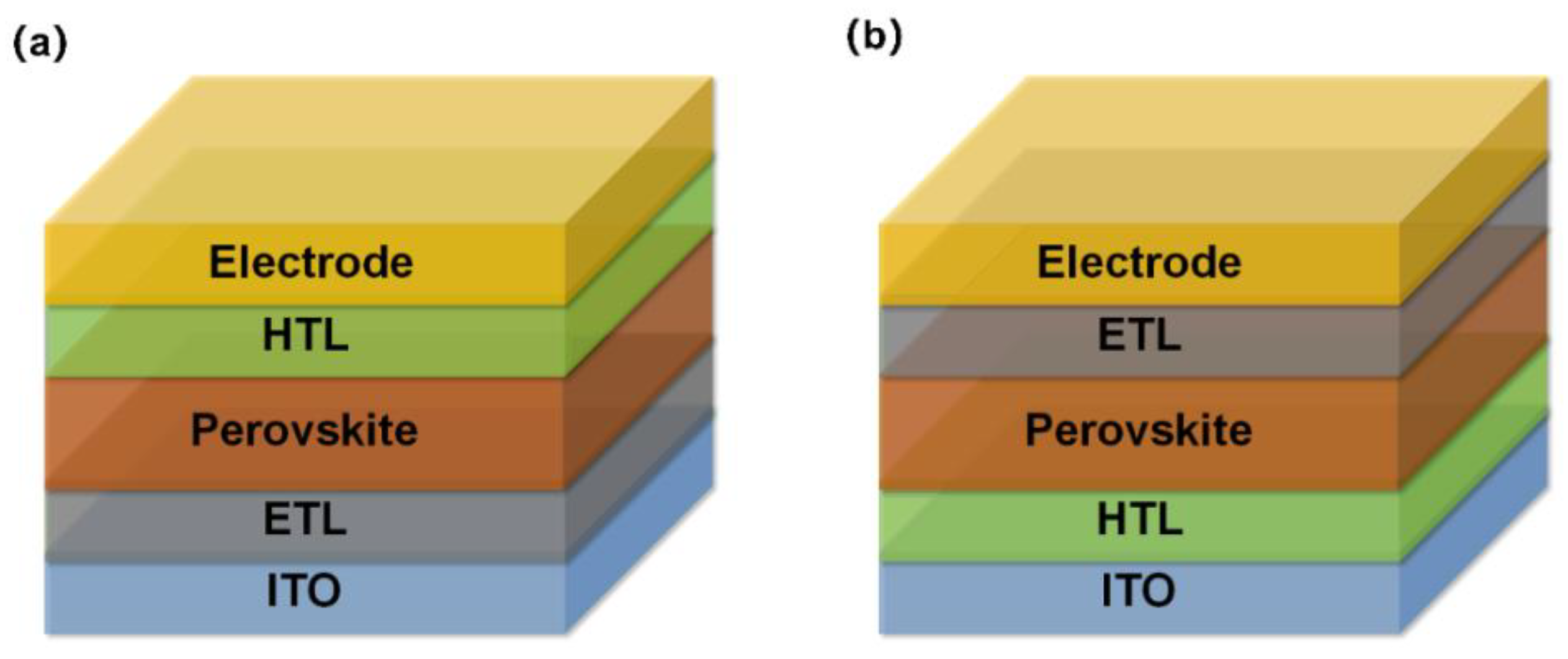

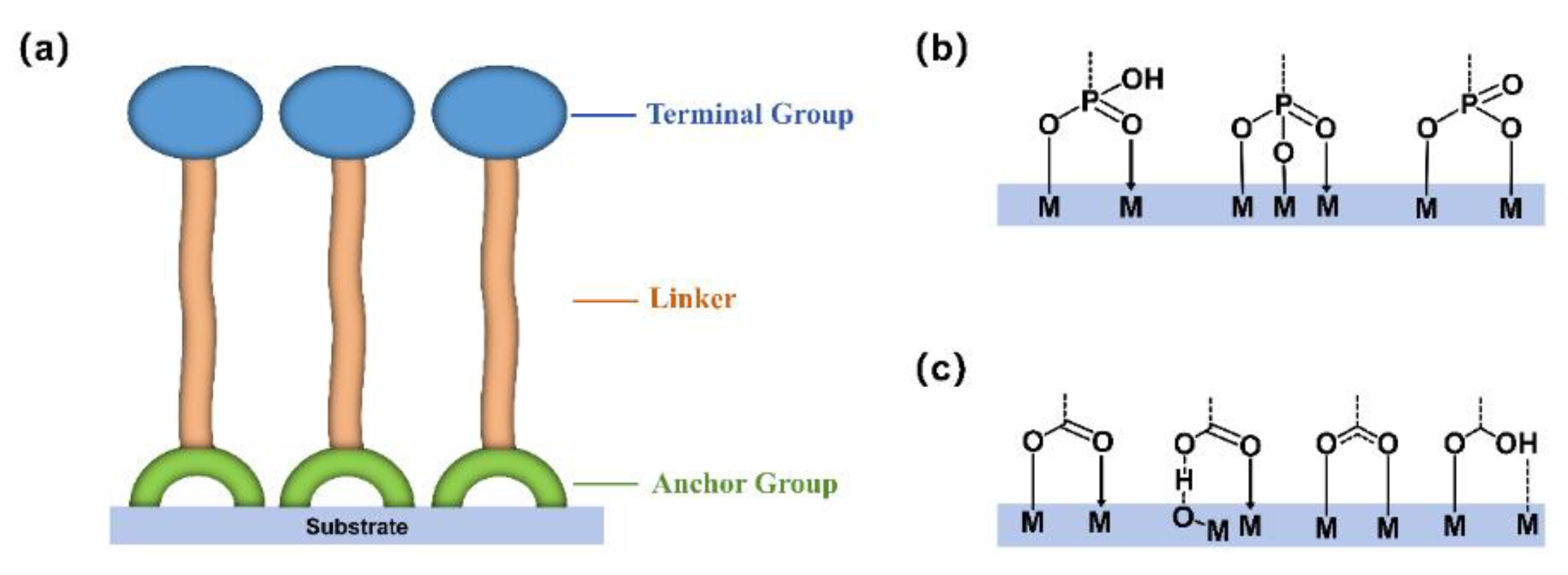

2. Self-Assembled Monolayers

2.1. Structural Composition and Anchoring Mechanisms of SAMs

2.2. Deposition Methods of SAMs

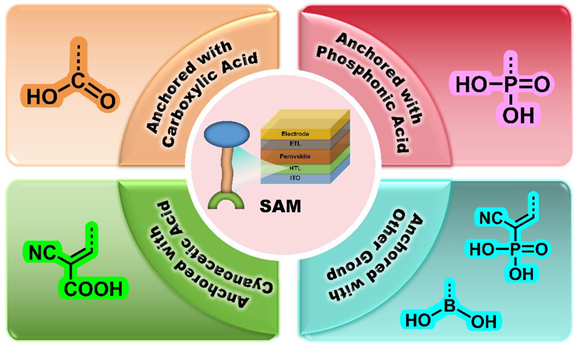

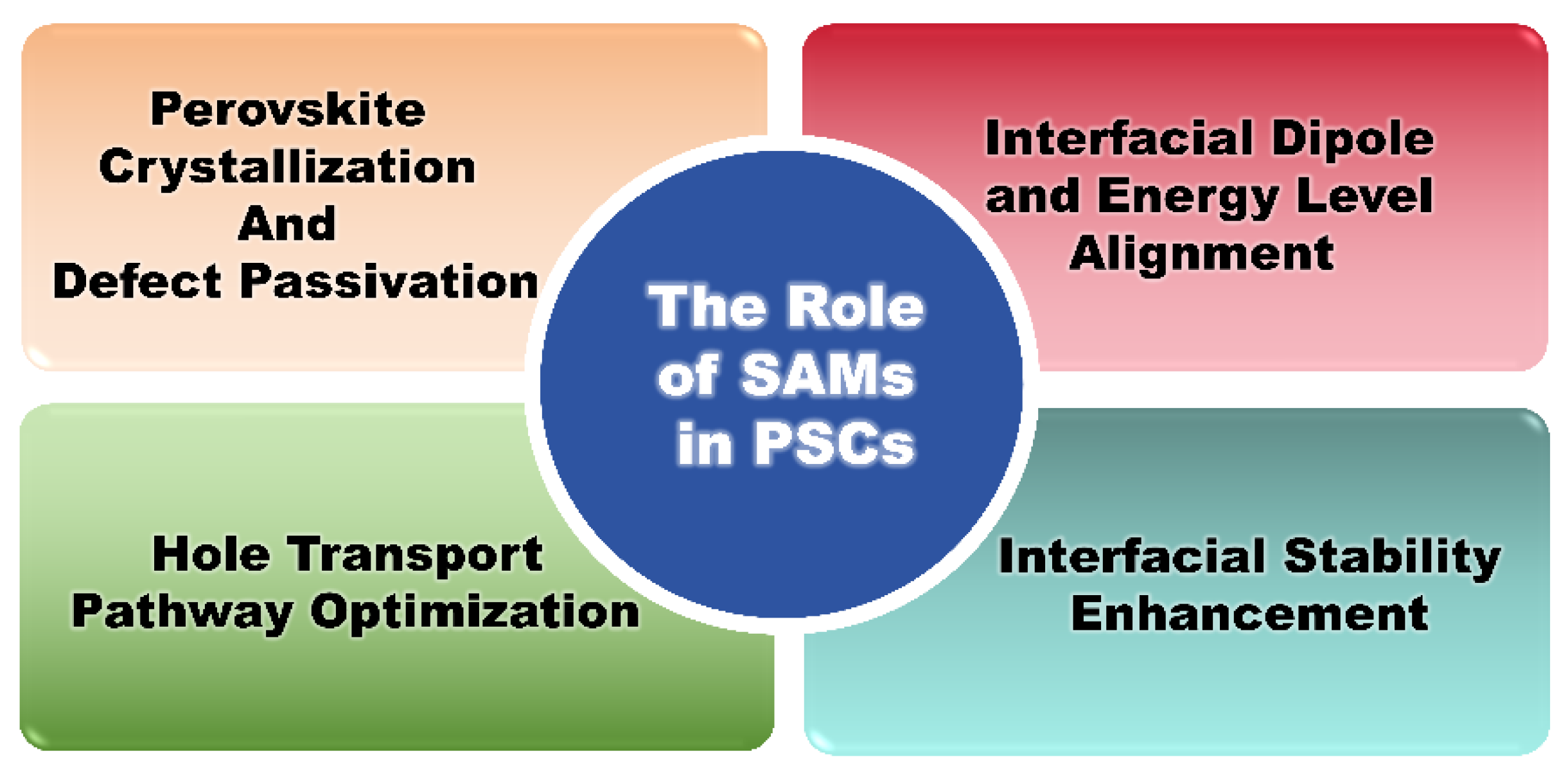

3. Role of SAMs in PSCs

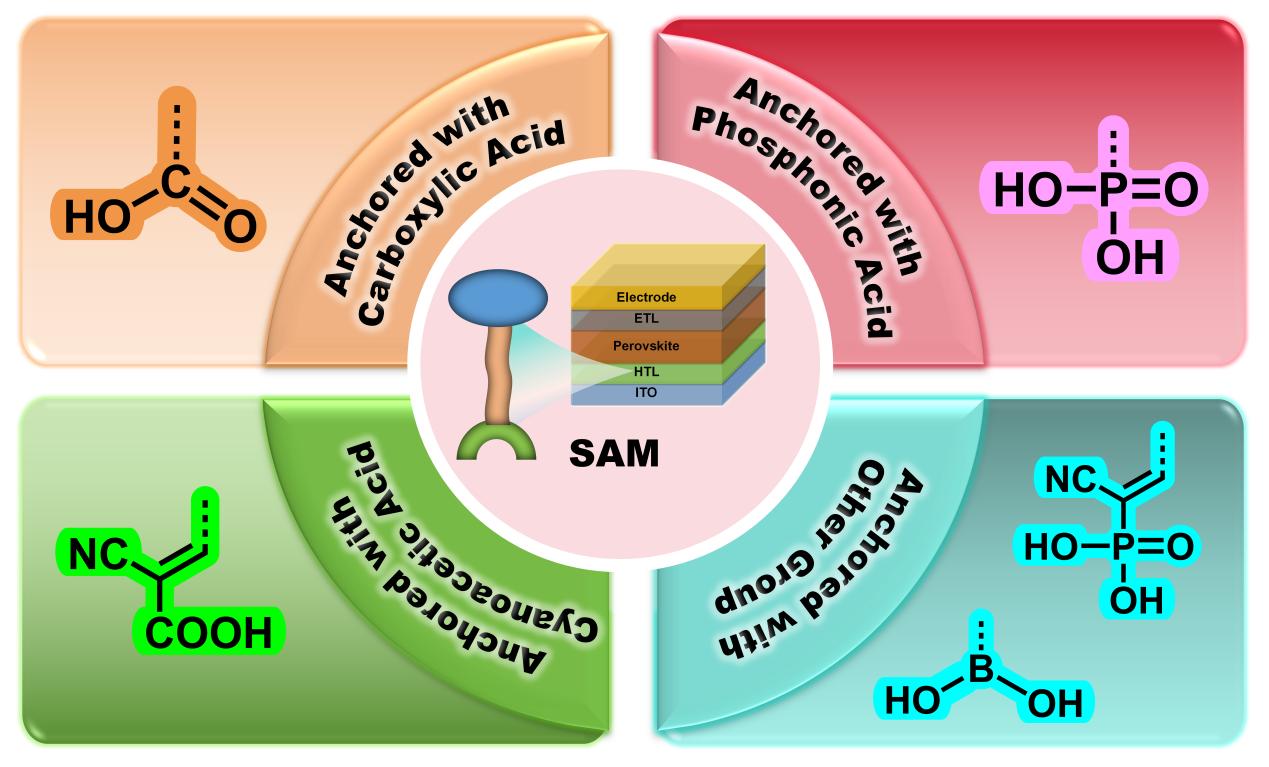

4. Application of SAMs in Perovskite Solar Cells

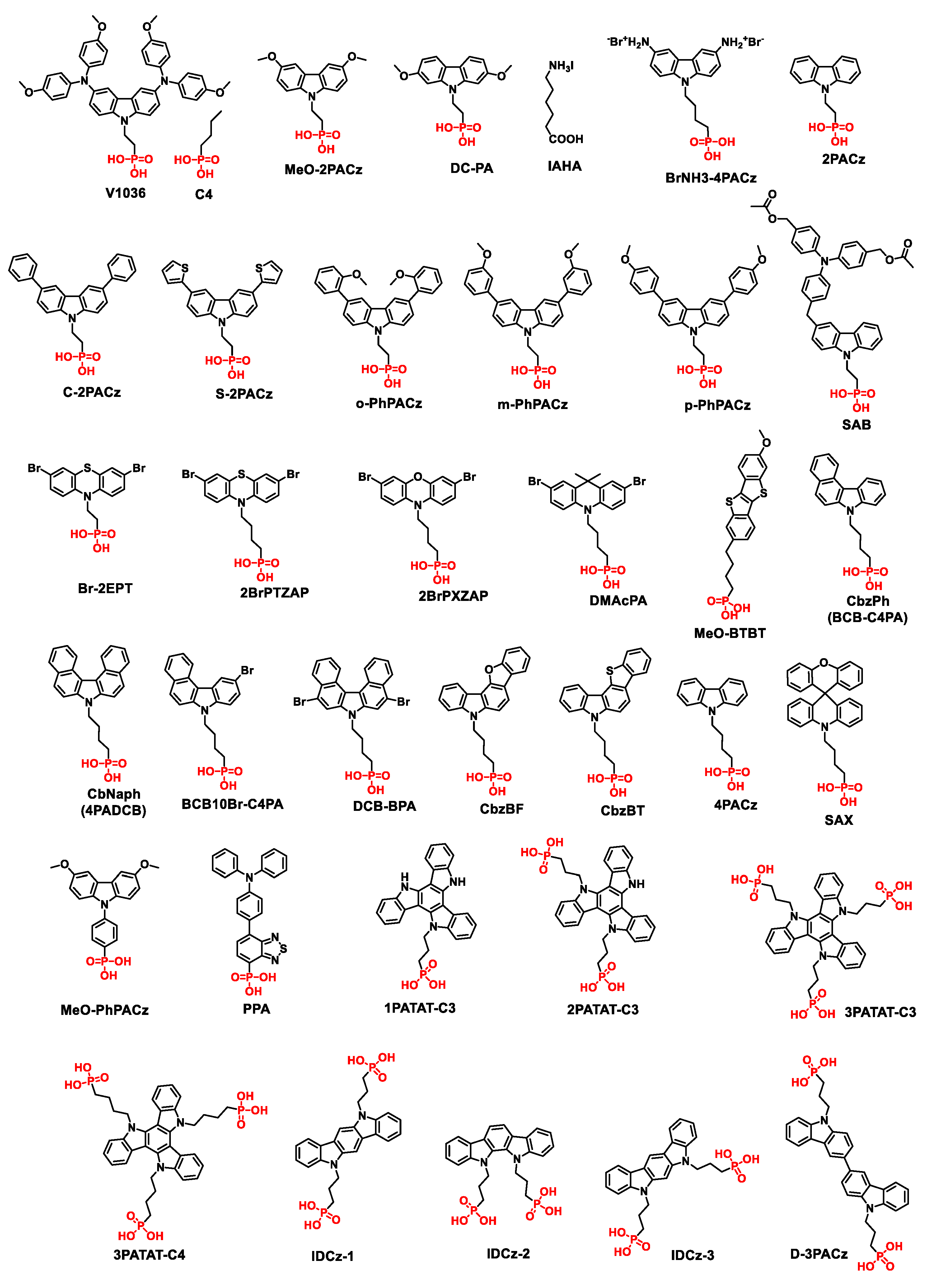

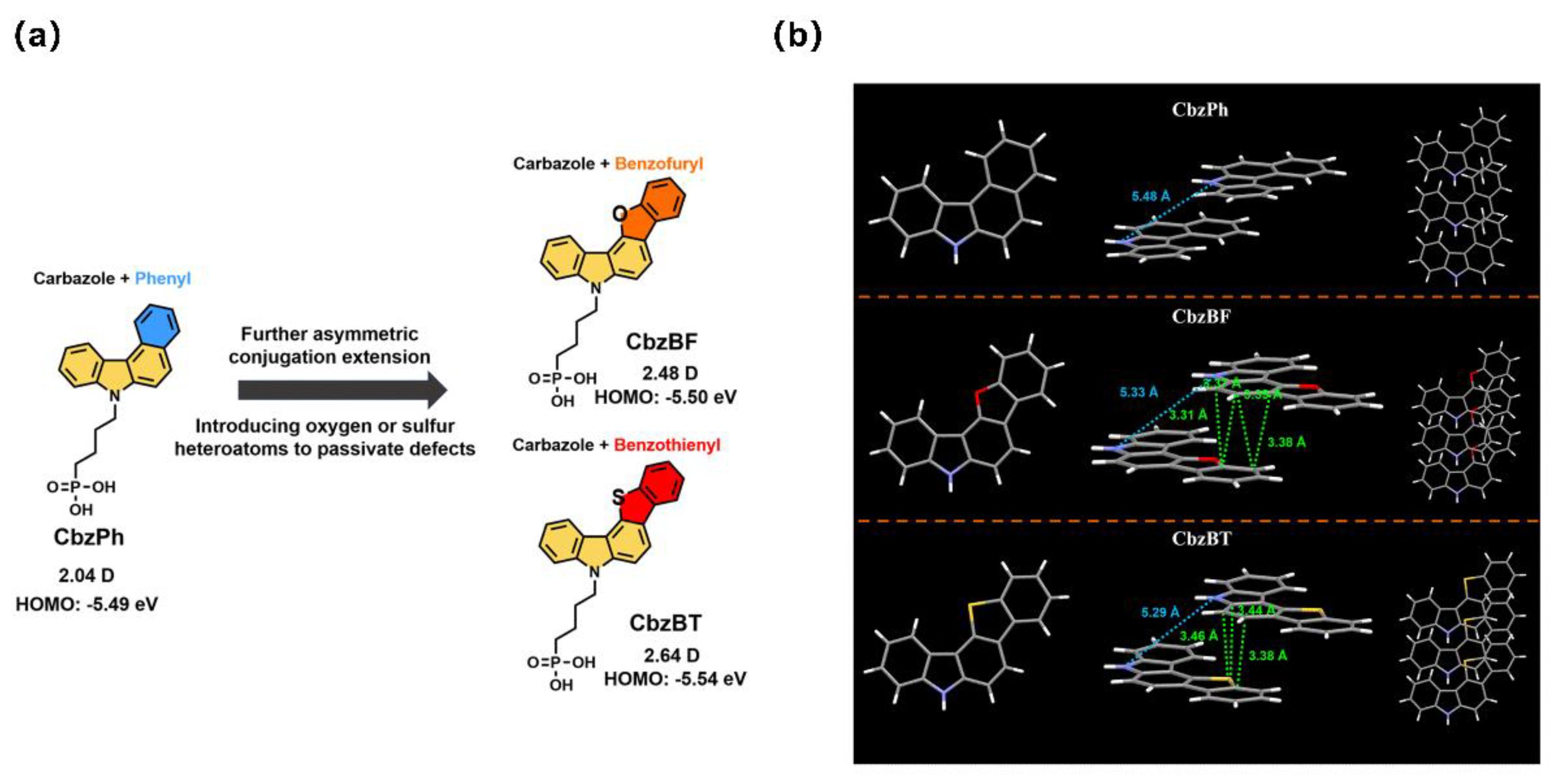

4.1. SAMs Anchored with Phosphonic Acid

4.2. SAMs Anchored with Carboxylic Acid

4.3. SAMs Anchored with Cyanoacetic Acid

4.4. SAMs Anchored with Other Functional Groups

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

5.1. Design of Molecular Structure

5.2. Device Commercial Production

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Graphical Abstract

References

- Leijtens, T.; Eperon, G.E.; Pathak, S.; Abate, A.; Lee, M.M.; Snaith, H.J. Overcoming ultraviolet light instability of sensitized TiO2 with meso-superstructured organometal tri-halide perovskite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L. PEM water electrolysis for hydrogen production: fundamentals, advances, and prospects. Carb Neutrality 2022, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrahee, I.; Li, Y.; Xing, G. Carbon-based Perovskite Solar Cells: From Current Fabrication Methodologies to Their Future Commercialization at Low Cost. Innov Discov 2025, 1, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Shin, S.S.; Seo, J. Toward Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells: Progress, Strategies, and Perspectives. Acs Energy Lett 2022, 7, 2084–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranks, S.D.; Eperon, G.E.; Grancini, G.; Menelaou, C.; Alcocer, M.J.P.; Leijtens, T.; Herz, L.M.; Petrozza, A.; Snaith, H.J. Electron-Hole Diffusion Lengths Exceeding 1 Micrometer in an Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Absorber. Sci 2013, 342, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, C.-R.; Im, J.-H.; Lee, K.-B.; Moehl, T.; Marchioro, A.; Moon, S.-J.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Yum, J.-H.; Moser, J.E.; Grätzel, M.; Park, N.-G. Lead Iodide Perovskite Sensitized All-Solid-State Submicron Thin Film Mesoscopic Solar Cell with Efficiency Exceeding 9%. Sci Rep 2012, 2, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Best Research-Cell Efficiencies. https://www.nrel.gov/pv/assets/pdfs/cell-pv-eff-emergingpv.pdf.

- Luo, X., Lin, X., Gao, F., Zhao, Y., Li, X., Zhan, L., Qiu, Z., Wang, J., Chen, C., Meng, L., Gao, X., Zhang, Y., Huang, Z., Fan, R., Liu, H., Chen, Y., Ren, X., Tang, J., Chen, C.-H., Yang, D., Tu, Y., Liu, X., Liu, D., Zhao, Q., You, J., Fang, J., Wu, Y., Han, H., Zhang, X., Zhao, D., Huang, F., Zhou, H., Yuan, Y., Chen, Q., Wang, Z., Liu, S. F., Zhu, R., Nakazaki, J., Li, Y., Han, L. Recent progress in perovskite solar cells: from device to commercialization. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 65, 2369–2416. [CrossRef]

- Kojima, A.; Teshima, K.; Shirai, Y.; Miyasaka, T. Organometal Halide Perovskites as Visible-Light Sensitizers for Photovoltaic Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6050–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, J.-W.; Jung, H.S.; Shin, H.; Park, N.-G. High-Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7867–7918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.D.; Yang, T.C.J.; Jain, S.M.; Wilson, G.J.; Sonar, P. Development of Dopant-Free Organic Hole Transporting Materials for Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1903326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Li, C.-Z. Recent advances in perovskite solar cells: efficiency, stability and lead-free perovskite. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 11462–11482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Yuan, N.; Ding, J.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S. Multifunctional indaceno [1,2-b:5,6-b′]dithiophene chloride molecule for stable high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 66, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urieta-Mora, J.; García-Benito, I.; Molina-Ontoria, A.; Martín, N. Hole transporting materials for perovskite solar cells: a chemical approach. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 8541–8571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, J.Y.; Zhong, Y.W. Low-Cost, High-Performance Organic Small Molecular Hole-Transporting Materials for Perovskite Solar Cells. Chinese J Org Chem 2021, 41, 1447–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.-Y.; Li, D.; Shi, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Jiang, X.; Hao, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, Y.-W.; Liu, S.F.; Mai, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ning, Z.; Wang, L.; Xu, B.; Meng, L.; Bian, Z.; Ge, Z.; Zhan, X.; You, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, Q. Recent progress in perovskite solar cells: material science. Sci. China Chem. 2022, 66, 10–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhao, D.; Li, Z.A. Recent advances in the design of dopant-free hole transporting materials for highly efficient perovskite solar cells. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2018, 29, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; You, P.; Tai, Q.; Yang, A.; Cao, J.; Zheng, F.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J.; Chan, P.K.L.; Yan, F. Solution-Phase Epitaxial Growth of Perovskite Films on 2D Material Flakes for High-Performance Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liao, J.-F.; Pan, H.; Xing, G. Interfacial Engineering for High-Performance PTAA-Based Inverted 3D Perovskite Solar Cells. Sol. RRL 2022, 6, 2200647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yan, Y.; Fang, Z.; Mi, G.; Pei, M.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; Ma, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Cheng, C.; Shi, Y. Al2O3 nanoparticles as surface modifier enables deposition of high quality perovskite films for ultra-flexible photovoltaics. Adv. Powder Mater. 2024, 3, 100142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangala, S.; Misra, R. Spiro-linked organic small molecules as hole-transport materials for perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 18750–18765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Xie, L.-H.; Sun, Y.-G.; Ren, B.-Y.; Liu, Q.-L. Research Progress of Hole Transport Materials Based on Spiro Aromatic-Skeleton in Perovskite Solar Cells. Acta Chimica Sinica 2021, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-P.; Kong, F.-T.; Chen, W.-C.; Yu, T.; Guo, F.-L.; Chen, J.; Dai, S.-Y. Application of Organic Hole-Transporting Materials in Perovskite Solar Cells. Acta Phys.-Chim. Sin. 2016, 32, 1347–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Cao, D. Dopant-free hole transport materials for perovskite solar cells: Isoindigo and dibenzonaphthyridine derivatives. Dyes Pigments 2025, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova, N.; Tress, W.; Humphry-Baker, R.; Dar, M.I.; Bojinov, V.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Grätzel, M. Light Harvesting and Charge Recombination in CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells Studied by Hole Transport Layer Thickness Variation. ACS NANO 2015, 9, 4200–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L.; You, J.; Guo, T.-F.; Yang, Y. Recent Advances in the Inverted Planar Structure of Perovskite Solar Cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 49, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dai, X.; Xu, S.; Jiao, H.; Zhao, L.; Huang, J. Stabilizing perovskite-substrate interfaces for high-performance perovskite modules. Sci 2021, 373, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, X.; Wu, X.; Zhong, C.; Liu, D.; Lei, D.; Jen, A.K.Y.; Li, Z.A.; Zhu, Z. Efficient Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells with Low Voltage Loss Achieved by a Pyridine-Based Dopant-Free Polymer Semiconductor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 7227–7233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guo, H.; Wu, Y. Advantages and challenges of self-assembled monolayer as a hole-selective contact for perovskite solar cells. MF 2023, 2, 012105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isikgor, F.H.; Zhumagali, S.; T. Merino, L.V.; De Bastiani, M.; McCulloch, I.; De Wolf, S. Molecular engineering of contact interfaces for high-performance perovskite solar cells. Nat Rev Mater 2022, 8, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Li, Y.; Zhong, Y. Towards cost-efficient and stable perovskite solar cells and modules: utilization of self-assembled monolayers. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 3958–3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto Galvis, C.E.; González Ruiz, D.A.; Martínez-Ferrero, E.; Palomares, E. Challenges in the design and synthesis of self-assembling molecules as selective contacts in perovskite solar cells. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 1534–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.-R.; Shao, J.-Y.; Zhong, Y.-W. Self-assembled monolayers as hole-transporting materials for inverted perovskite solar cells. Mol. Syst. Des. Eng. 2023, 8, 1440–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; Roldán-Carmona, C.; Sohail, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. Applications of Self-Assembled Monolayers for Perovskite Solar Cells Interface Engineering to Address Efficiency and Stability. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2002989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afraj, S.N.; Kuan, C.H.; Lin, J.S.; Ni, J.S.; Velusamy, A.; Chen, M.C.; Diau, E.W.G. Quinoxaline-Based X-Shaped Sensitizers as Self-Assembled Monolayer for Tin Perovskite Solar cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2213939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galoppini, E. Linkers for anchoring sensitizers to semiconductor nanoparticles. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ye, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, H.; Zhan, L.; Jiang, X.; Li, Y.; Ji, X.; Liu, S.; Yu, M.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, R.; Liu, Z.; Ning, Z.; Neher, D.; Han, L.; Lin, Y.; Tian, H.; Chen, W.; Stolterfoht, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, W.-H.; Wu, Y. Minimizing buried interfacial defects for efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. Sci 2023, 380, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.M.; Wei, M.; Lempesis, N.; Yu, W.; Hossain, T.; Agosta, L.; Carnevali, V.; Atapattu, H.R.; Serles, P.; Eickemeyer, F.T.; Shin, H.; Vafaie, M.; Choi, D.; Darabi, K.; Jung, E.D.; Yang, Y.; Kim, D.B.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Chen, B.; Amassian, A.; Filleter, T.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Graham, K.R.; Xiao, L.; Rothlisberger, U.; Grätzel, M.; Sargent, E.H. Low-loss contacts on textured substrates for inverted perovskite solar cells. Nature 2023, 624, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, H.; Shi, J.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, P.; Li, F.; Gong, J.; Fang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, J.; Han, A.; Zhang, L.; Liu, W.; Meng, F.; Cui, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, M. Fully Textured, Production-Line Compatible Monolithic Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells Approaching 29% Efficiency. Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2206193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phung, N.; Verheijen, M.; Todinova, A.; Datta, K.; Verhage, M.; Al-Ashouri, A.; Köbler, H.; Li, X.; Abate, A.; Albrecht, S.; Creatore, M. Enhanced Self-Assembled Monolayer Surface Coverage by ALD NiO in p-i-n Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 14, 2166–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Xiong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Ma, F.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chu, X.; Zhang, X.; You, J. Homogenized NiOx nanoparticles for improved hole transport in inverted perovskite solar cells. Sci 2023, 382, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.L.; Harake, M.; Bent, S.F. Sequential Use of Orthogonal Self-Assembled Monolayers for Area-Selective Atomic Layer Deposition of Dielectric on Metal. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 10, 2202134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Montague, M.; Hammond, P.T. Selective deposition in multilayer assembly: SAMs as molecular templates. Supramol. Sci. 1997, 4, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-W.; Tseng, Y.-H.; Hsu, C.-S.; Chen, J.-T. Area-Selective Atomic Layer Deposition on Metal/Dielectric Patterns: Amphiphobic Coating, Vaporizable Inhibitors, and Regenerative Processing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 28817–28824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farag, A.; Feeney, T.; Hossain, I.M.; Schackmar, F.; Fassl, P.; Küster, K.; Bäuerle, R.; Ruiz-Preciado, M.A.; Hentschel, M.; Ritzer, D.B.; Diercks, A.; Li, Y.; Nejand, B.A.; Laufer, F.; Singh, R.; Starke, U.; Paetzold, U.W. Evaporated Self-Assembled Monolayer Hole Transport Layers: Lossless Interfaces in p-i-n Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2203982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, S.P.; Scheres, L.; Marcelis, A.T.M.; Zuilhof, H. Covalent Surface Modification of Oxide Surfaces. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6322–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, R.; Zuo, L. Self-assembly monolayers boosting organic–inorganic halide perovskite solar cell performance. J. Mater. Res. 2018, 33, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Cho, S.J.; Byeon, S.E.; He, X.; Yoon, H.J. Self-Assembled Monolayers as Interface Engineering Nanomaterials in Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2002606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, T.; Xiao, C.; Gao, D.; Patel, J.B.; Kuciauskas, D.; Magomedov, A.; Scheidt, R.A.; Wang, X.; Harvey, S.P.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, C.; Morales, D.; Pruett, H.; Wieliczka, B.M.; Kirmani, A.R.; Padture, N.P.; Graham, K.R.; Yan, Y.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; McGehee, M.D.; Zhu, Z.; Luther, J.M. Co-deposition of hole-selective contact and absorber for improving the processability of perovskite solar cells. Nat Energy 2023, 8, 462–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yan, K.; Wang, X.; Li, B.; Niu, B.; Yan, M.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, K.; Fang, Y.; Yu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.Z. High-Efficiency Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells via In Situ Passivation Directed Crystallization. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2408101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Wang, D.; Shang, W.; Li, Y.; Zeng, J.; Zhu, P.; Zhang, B.; Mei, L.; Chen, X.K.; Xu, Z.X.; Lin, F.R.; Xu, B.; Jen, A.K.Y. Spin-Coated and Vacuum-Processed Hole-Extracting Self-Assembled Multilayers with H-Aggregation for High-Performance Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202411730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Zheng, J.; Duan, W.; Yang, J.; Mahmud, M.A.; Lian, Q.; Tang, S.; Liao, C.; Bing, J.; Yi, J.; Leung, T.L.; Cui, X.; Chen, H.; Jiang, F.; Huang, Y.; Lambertz, A.; Jankovec, M.; Topič, M.; Bremner, S.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Cheng, C.; Ding, K.; Ho-Baillie, A. Molecular engineering of hole-selective layer for high band gap perovskites for highly efficient and stable perovskite-silicon tandem solar cells. Joule 2023, 7, 2583–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Cai, S.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, D.; Gong, S.; Khan, D.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, K.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.-G.; Chen, X.; Jen, A.K.Y.; Xu, Z.-X. Conjugated linker-boosted self-assembled monolayer molecule for inverted perovskite solar cells. Joule 2024, 8, 2123–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, T.; Pu, X.; Feng, G.; Jia, S.; Bai, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, Q.; Li, X. Enhancing Hole Transport Uniformity for Efficient Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells through Optimizing Buried Interface Contacts and Suppressing Interface Recombination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202412601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, A.; Park, K.H.; Nguyen, H.D.; Siddique, Y.; Shah, S.F.A.; Tran, H.; Park, S.; Lee, S.I.; Lee, K.K.; Han, C.H.; Kim, K.; Ahn, S.; Jeong, I.; Park, Y.S.; Hong, S. Novel Phenothiazine-Based Self-Assembled Monolayer as a Hole Selective Contact for Highly Efficient and Stable p-i-n Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 12, 2103175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Wang, Y.; Hao, M.; Li, B.; Yang, K.; Ji, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Chi, W.; Guo, X.; Huang, W. Green-Solvent-Processable Low-Cost Fluorinated Hole Contacts with Optimized Buried Interface for Highly Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 43547–43557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Han, G.S.; Jung, H.S. Managing the lifecycle of perovskite solar cells: Addressing stability and environmental concerns from utilization to end-of-life. eScience 2024, 4, 100243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, A.; Al-Ashouri, A.; Kasparavičius, E.; Strazdaite, S.; Niaura, G.; Jošt, M.; Malinauskas, T.; Albrecht, S.; Getautis, V. Self-Assembled Hole Transporting Monolayer for Highly Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.J.; Li, Y.; Xing, G.C.; Cao, D.R. Surface passivation of perovskite with organic hole transport materials for highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Mater Today Adv 2022, 16, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xia, J.; Liu, T.; Wang, K. Modifying PTAA/Perovskite Interface via 4-Butanediol Ammonium Bromide for Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. SMALL 2023, 19, 2208243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bi, L.; Huang, X.; Feng, Q.; Liu, M.; Chen, M.; An, Y.; Jiang, W.; Lin, F.R.; Fu, Q.; Jen, A.K.Y. Bilayer interface engineering through 2D/3D perovskite and surface dipole for inverted perovskite solar modules. eScience 2024, 4, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, H.; Zheng, N.; Bai, G.; Zha, Y.; Qi, H.; Bian, Z.; Zhan, X.; Liu, Z. Enhancing performance of tin-based perovskite solar cells via fused-ring electron acceptor. eScience 2023, 3, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Liu, X.; Chen, J. Opportunities and challenges of hole transport materials for high-performance inverted hybrid-perovskite solar cells. Exploration 2023, 3, 20220027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ji, L.; Liu, R.; Zhang, C.; Mak, C.H.; Zou, X.; Shen, H.-H.; Leu, S.-Y.; Hsu, H.-Y. A review on morphology engineering for highly efficient and stable hybrid perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 12842–12875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Z.A. Recent advances in developing high-performance organic hole transporting materials for inverted perovskite solar cells. Front. Optoelectron. 2022, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Ashouri, A.; Magomedov, A.; Roß, M.; Jošt, M.; Talaikis, M.; Chistiakova, G.; Bertram, T.; Márquez, J.A.; Köhnen, E.; Kasparavičius, E.; Levcenco, S.; Gil-Escrig, L.; Hages, C.J.; Schlatmann, R.; Rech, B.; Malinauskas, T.; Unold, T.; Kaufmann, C.A.; Korte, L.; Niaura, G.; Getautis, V.; Albrecht, S. Conformal monolayer contacts with lossless interfaces for perovskite single junction and monolithic tandem solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3356–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Qi, F.; Li, F.; Wu, S.; Lin, F.R.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lee, C.S.; Jen, A.K.Y. Co-assembled Monolayers as Hole-Selective Contact for High-Performance Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells with Optimized Recombination Loss and Long-Term Stability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

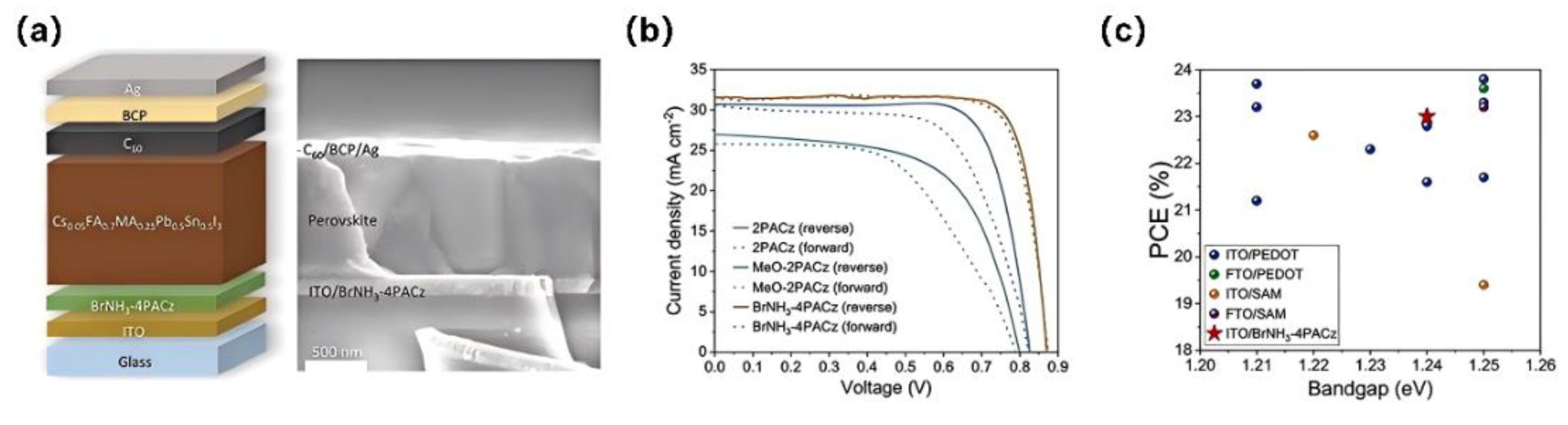

- Zhumagali, S.; Li, C.; Marcinskas, M.; Dally, P.; Liu, Y.; Ugur, E.; Petoukhoff, C.E.; Ghadiyali, M.; Prasetio, A.; Marengo, M.; Pininti, A.R.; Azmi, R.; Schwingenschlögl, U.; Laquai, F.; Getautis, V.; Malinauskas, T.; Aydin, E.; Sargent, E.H.; De Wolf, S. Efficient Narrow Bandgap Pb-Sn Perovskite Solar Cells Through Self-Assembled Hole Transport Layer with Ionic Head. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 2404617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ding, B.; Han, M.; Yang, Z.; Chen, J.; Shi, P.; Xue, X.; Ghadari, R.; Zhang, X.; Wang, R.; Brooks, K.; Tao, L.; Kinge, S.; Dai, S.; Sheng, J.; Dyson, P.J.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Ding, Y. Extending the π-Conjugated System in Spiro-Type Hole Transport Material Enhances the Efficiency and Stability of Perovskite Solar Modules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, L. Simultaneously enhancing hole extraction and defect passivation with more conductive hole-selective self-assembled molecules for efficient inverted perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 15644–15653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Guan, X.; Wang, L.; Deng, L.-l.; Li, G.; Abate, A.; Li, M. Tailored Lattice-Matched Carbazole Self-Assembled Molecule for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 8004–8011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

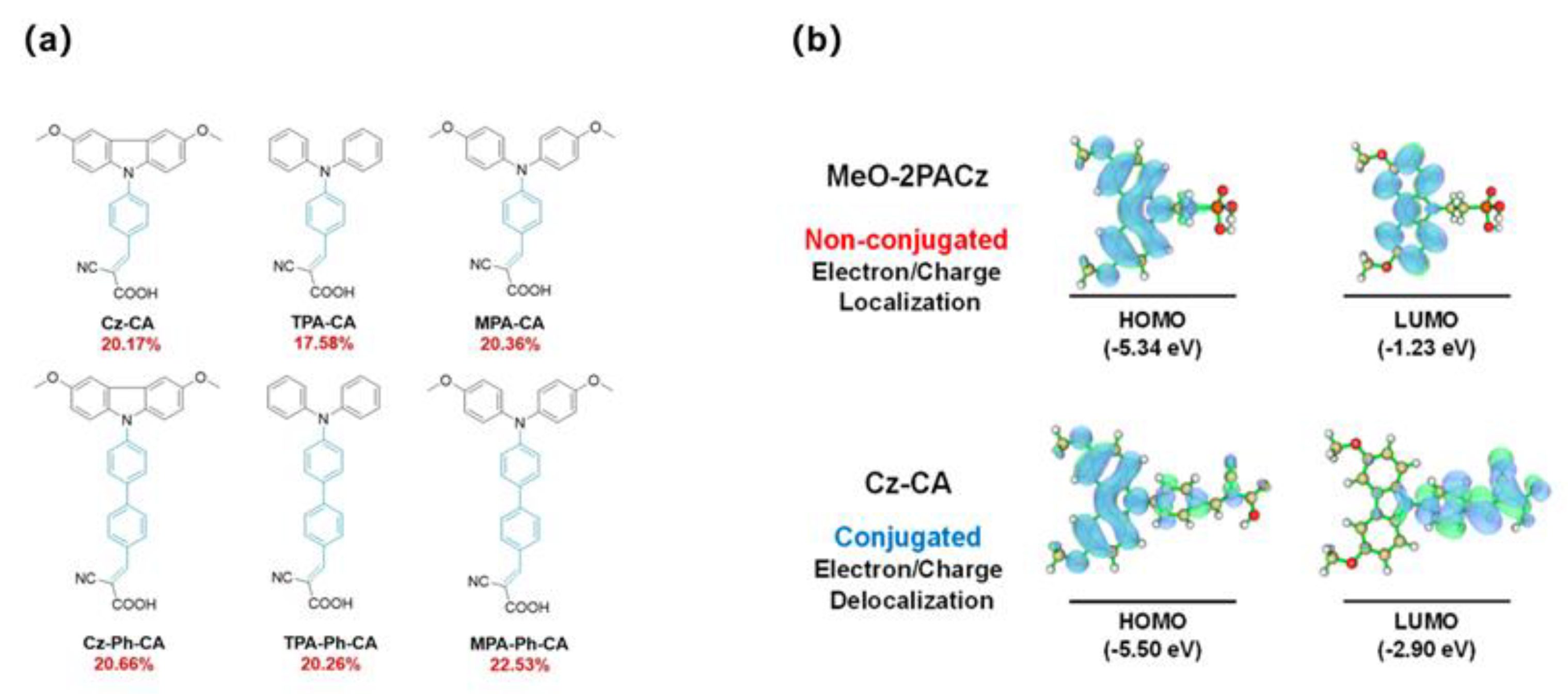

- Dong, B.; Wei, M.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, Y.; Ran, Y.; Cui, M.; Su, Z.; Fan, Q.; Bi, Z.; Edvinsson, T.; Ding, Z.; Ju, H.; You, S.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Li, X.; Hagfeldt, A.; Grätzel, M.; Liu, Y. Self-assembled bilayer for perovskite solar cells with improved tolerance against thermal stresses. Nat Energy 2025, 10, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tan, Q.; Chen, G.; Gao, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Xiu, J.; Chen, W.; He, Z. Simple and robust phenoxazine phosphonic acid molecules as self-assembled hole selective contacts for high-performance inverted perovskite solar cells. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, Q.; Li, Z.; Luo, G.; Zhang, X.; Che, B.; Chen, G.; Gao, H.; He, D.; Ma, G.; Wang, J.; Xiu, J.; Yi, H.; Chen, T.; He, Z. Inverted perovskite solar cells using dimethylacridine-based dopants. Nature 2023, 620, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

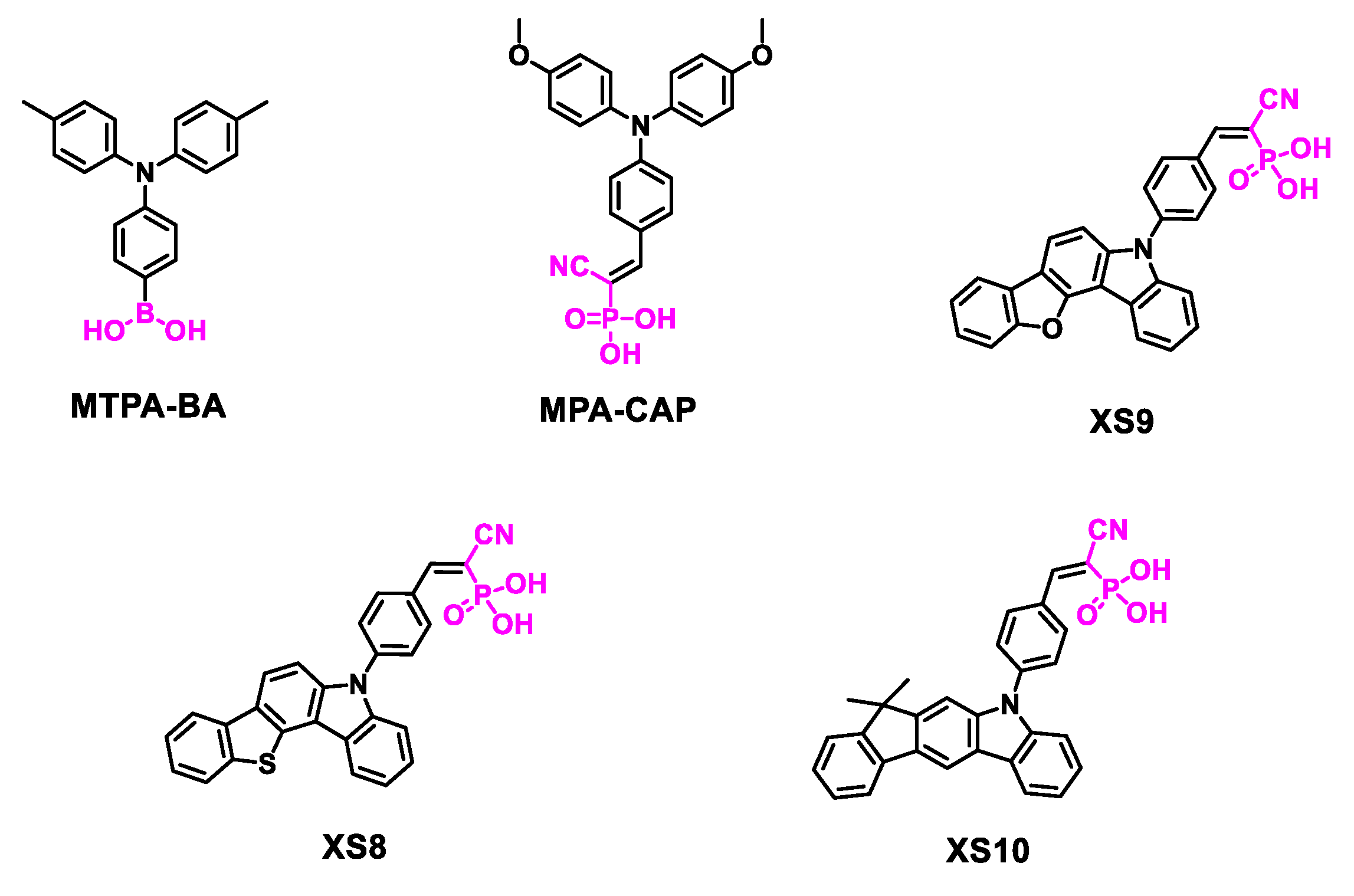

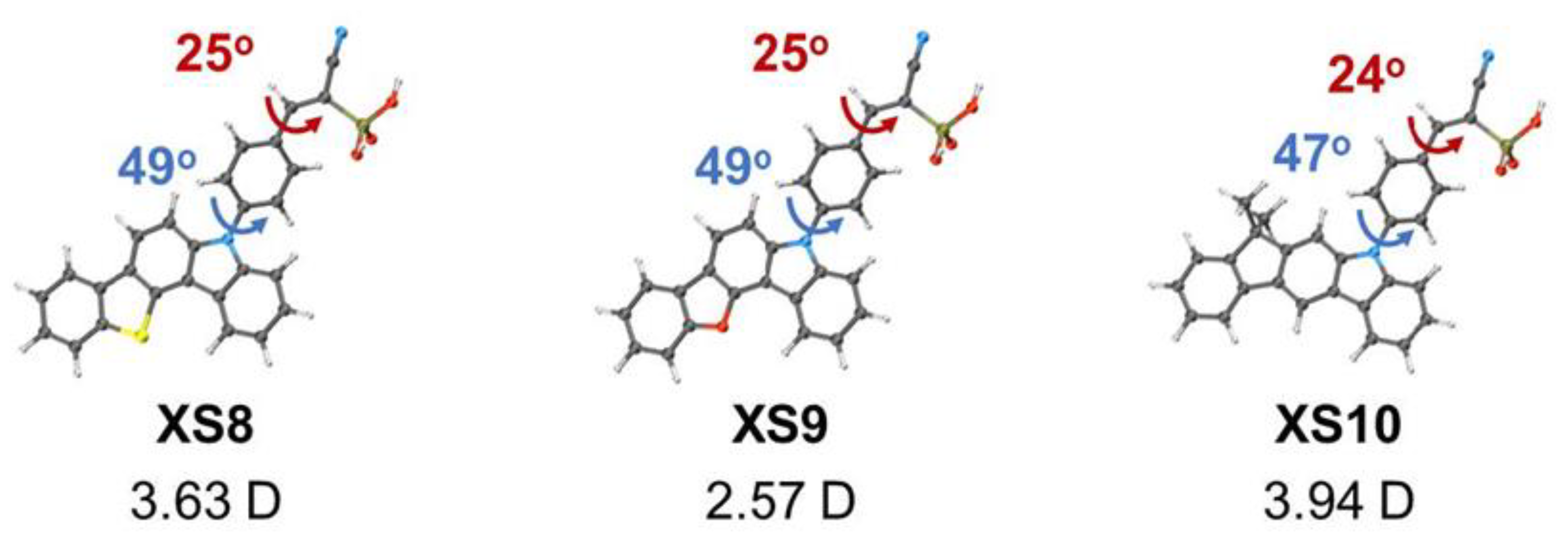

- Liu, M.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; An, Y.; Yao, Z.; Fan, B.; Qi, F.; Liu, K.; Yip, H.L.; Lin, F.R.; Jen, A.K.Y. Defect-Passivating and Stable Benzothiophene-Based Self-Assembled Monolayer for High-Performance Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2303742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Li, F.; Li, M.; Qi, F.; Lin, F.R.; Jen, A.K.Y. π-Expanded Carbazoles as Hole-Selective Self-Assembled Monolayers for High-Performance Perovskite Solar Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202213560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, C.; Yu, J.; Zhao, D.; Tang, W. Versatile Self-Assembled Molecule Enables High-Efficiency Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells and Organic Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2023, 13, 2300694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Wang, W.; He, R.; Zhu, J.; Jiao, W.; Luo, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wei, K.; Zhang, J.; Tsang, S.-W.; Chen, C.; Tang, W.; Zhao, D. Achieving a high open-circuit voltage of 1.339 V in 1.77 eV wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells via self-assembled monolayers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2024, 17, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Lin, F.R.; Jen, A.K.Y. Rational molecular design of multifunctional self-assembled monolayers for efficient hole selection and buried interface passivation in inverted perovskite solar cells. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 2778–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, R.; Tian, L.; Zhao, K.; Shen, J.; Jin, D.; Peng, Z.; Yao, L.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Jin, L.; Chu, S.; Wang, S.; Tian, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Shi, P.; Wang, X.; Fan, W.; Sun, X.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.-Z.; Wu, G.; Shi, W.; Wang, H.-F.; Deng, T.; Wang, R.; Yang, D.; Xue, J. Molecular contacts with an orthogonal π-skeleton induce amorphization to enhance perovskite solar cell performance. Nat. Chem. 2025, 17, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Liang, L.; Yu, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Gao, P. Fully Aromatic Self-Assembled Hole-Selective Layer toward Efficient Inverted Wide-Bandgap Perovskite Solar Cells with Ultraviolet Resistance. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 63, e202315281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, X.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, L.; You, S.; Li, W.; Gong, Z.; Huang, R.; Cui, Y.; Rong, Y.; Zeng, H.; Li, X. Tailoring Multifunctional Self-Assembled Hole Transporting Molecules for Highly Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.A.; Funasaki, T.; Ueberricke, L.; Nojo, W.; Murdey, R.; Yamada, T.; Hu, S.; Akatsuka, A.; Sekiguchi, N.; Hira, S.; Xie, L.; Nakamura, T.; Shioya, N.; Kan, D.; Tsuji, Y.; Iikubo, S.; Yoshida, H.; Shimakawa, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Wakamiya, A. Tripodal Triazatruxene Derivative as a Face-On Oriented Hole-Collecting Monolayer for Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 7528–7539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yan, P.; Yang, D.; Guan, H.; Yang, S.; Cao, X.; Liao, X.; Ding, P.; Sun, H.; Ge, Z. Bisphosphonate-Anchored Self-Assembled Molecules with Larger Dipole Moments for Efficient Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells with Excellent Stability. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2401537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, T.; Liu, W.; Xu, H.; Chen, H.; Wong, K.L.; Zhang, W.; Su, Q.; Wang, T.; Xu, S.; Liu, X.; Lv, W.; Geng, R.; Yin, J.; Song, X. Self-assembled hole-transport material incorporating biphosphonic acid for dual-defect passivation in NiOx-based perovskite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2024, 12, 33066–33075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Can, M.; Rodriguez-Seco, C.; Aktas, E.; Pudi, R.; Cambarau, W.; Demic, S.; Palomares, E. Semiconductor self-assembled monolayers as selective contacts for efficient PiN perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktas, E.; Pudi, R.; Phung, N.; Wenisch, R.; Gregori, L.; Meggiolaro, D.; Flatken, M.A.; De Angelis, F.; Lauermann, I.; Abate, A.; Palomares, E. Role of Terminal Group Position in Triphenylamine-Based Self-Assembled Hole-Selective Molecules in Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 17461–17469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, E.; Aktas, E.; Mendéz, M.; Arkan, E.; Sánchez, J.G.; Martínez-Ferrero, E.; Silvestri, F.; Barrena, E.; Can, M.; Demic, S.; Palomares, E. Monodentate versus Bidentate Anchoring Groups in Self-Assembling Molecules (SAMs) for Robust p–i–n Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Luo, Y.; He, R.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Yi, Z.; Thiesbrummel, J.; Wang, C.; Lang, F.; Lai, H.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, W.; Cui, G.; Ren, S.; Hao, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yao, F.; Lin, Q.; Wu, L.; Zhang, J.; Stolterfoht, M.; Fu, F.; Zhao, D. A donor–acceptor-type hole-selective contact reducing non-radiative recombination losses in both subcells towards efficient all-perovskite tandems. Nat Energy 2023, 8, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Chen, H. Interfacial Modification of NiOx for Highly Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2024, 14, 2400616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Fan, H.; Xu, X.; Li, G.; Gu, X.; Luo, D.; Shan, C.; Yang, Q.; Dong, S.; Miao, C.; Xie, Z.; Lu, G.; Wang, D.H.; Sun, P.P.; Kyaw, A.K.K. A Fluorination Strategy and Low-Acidity Anchoring Group in Self-Assembled Molecules for Efficient and Stable Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, M.A.; Funasaki, T.; Adachi, Y.; Hira, S.; Tan, T.; Akatsuka, A.; Yamada, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; Matsushige, Y.; Kaneko, R.; Asahara, C.; Nakamura, T.; Murdey, R.; Yoshida, H.; Kanemitsu, Y.; Wakamiya, A. Molecular Design of Hole-Collecting Materials for Co-Deposition Processed Perovskite Solar Cells: A Tripodal Triazatruxene Derivative with Carboxylic Acid Groups. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025, 147, 2797–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, R.; Tang, Y.; Su, Z.; Hu, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Xue, Y.; Gao, X.; Li, G.; Pascual, J.; Abate, A.; Li, M. Anchoring Charge Selective Self-Assembled Monolayers for Tin–Lead Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2312264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Yao, L.; Liu, C.; Yavuz, I.; Shen, J.; Shi, P.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Y.; Jin, D.; Tian, Y.; Wang, S.; Fan, W.; Xu, J.; Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Tian, L.; Liu, R.; Değer, C.; Wang, R.; Xue, J. Tailoring the π-conjugation in self-assembled hole-selective molecules for perovskite photovoltaics. Sci. China Mater. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Zhuang, X.; Tang, Y.; Li, B.; Yao, X.; Feng, X.; Zhang, X.; Su, M.; He, Z.; Marks, T.J.; Facchetti, A.; Guo, X. Teaching an Old Anchoring Group New Tricks: Enabling Low-Cost, Eco-Friendly Hole-Transporting Materials for Efficient and Stable Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 16632–16643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, R.; Mu, C.; Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, W.-H. Conjugated Self-Assembled Monolayer as Stable Hole-Selective Contact for Inverted Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Materials Lett. 2022, 4, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afraj, S.N.; Kuan, C.H.; Cheng, H.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Liu, C.L.; Shih, Y.S.; Lin, J.M.; Tsai, Y.W.; Chen, M.C.; Diau, E.W.G. Triphenylamine-Based Y-Shaped Self-Assembled Monolayers for Efficient Tin Perovskite Solar Cells. SMALL 2024, 21, 2408638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Huang, Z.-S. Self-assembled organic molecules with a fused aromatic ring as hole-transport layers for inverted perovskite solar cells: the effect of linkers on performance. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 6833–6841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Hu, H.; Zhang, S.; Ji, X.; Cao, X.-M.; Ning, Z.; Zhu, W.-H.; Tian, H.; Wu, Y. Neglected acidity pitfall: boric acid-anchoring hole-selective contact for perovskite solar cells. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, X.; Zhang, D.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, H.; Huang, J.; Su, J.; Xu, B. Fused Carbazole-based Self-Assembled Monolayers Enable Efficient Perovskite Solar Cells and Perovskite Light-Emitting Diodes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2401617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1036 | -4.7 | ITO/V1036+C4/Cs0.05 (MA0.17FA0.83)0.95Pb (I0.83Br0.17)3/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.09 | 21.4 | 76.5 | 17.8 | [58] |

| MeO-2PACz | -5.1 | ITO/MeO-2PACz/Cs0.05 (MA0.17FA0.83)0.95Pb (I0.83Br0.17)3/C60/BCP/Cu (Ag) | 1.144 | 21.9 | 80.2 | 20.8 | [66] |

| DC-PA | -5.38 | ITO/DC-PA+IAHA/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.16 | 24.66 | 82.45 | 23.59 | [67] |

| BrNH3-4PACz | -5.18 | ITO/BrNH3-4PACz/Cs0.05FA0.70MA0.25Sn0.5Pb0.5I3/EDA/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.88 | 32 | 82 | 23 | [68] |

| 2PACz | -5.44 | ITO/ 2PACz / Cs0.2FA0.8PbI3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.01 | 21.87 | 79.23 | 17.5 | [70] |

| C-2PACz | -5.46 | ITO/ C-2PACz / Cs0.2FA0.8PbI3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.05 | 22.45 | 77.37 | 18.16 | [70] |

| S-2PACz | -5.48 | ITO/ S-2PACz / Cs0.2FA0.8PbI3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.05 | 22.66 | 78.65 | 18.65 | [70] |

| o-PhPACz | -5.00 | FTO/ o-PhPACz / perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.16 | 25.81 | 83.5 | 24.7 | [71] |

| m-PhPACz | -5.01 | FTO/ m-PhPACz / perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.18 | 25.8 | 85.4 | 26.2 | [71] |

| p-PhPACz | -5.22 | FTO/ p-PhPACz / perovskite/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.17 | 25.78 | 82 | 25.5 | [71] |

| SAB | -5.57 | FTO/ SAB / FA0.84MA0.11Cs0.05 Pb (I0.987Br0.013)3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.174 | 26.2 | 85.5 | 26.3 | [72] |

| Br-2EPT | -5.47 | TCO/Br-2EPT/FA0.92MA0.08Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.09 | 25.11 | 82 | 22.44 | [55] |

| 2BrPTZAP | -5.77 | ITO/2BrPTZAP/Cs0.05 (FA0.85MA0.15)0.95Pb (I0.85Br0.15)3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.18 | 22.29 | 80.02 | 22.06 | [73] |

| 2BrPXZAP | -5.59 | ITO/2BrPXZAP/Cs0.05 (FA0.85MA0.15)0.95Pb (I0.85Br0.15)3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.19 | 22.51 | 81.69 | 22.93 | [73] |

| Table 1 (Continued) | |||||||

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) |

JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref. |

| DMAcPA | -5.98 | ITO/ (DMAcPA)Perovskite/PEABr/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.187 | 25.69 | 84.73 | 25.86 | [74] |

| MeO-BTBT | -5.39 | ITO/MeO-BTBT/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.16 | 24.87 | 85.28 | 24.53 | [75] |

| CbzPh | -5.36 | ITO/CbzPh/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.12 | 23.43 | 73.06 | 19.2 | [76] |

| CbzNaph | -5.24 | ITO/CbzNaph/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.17 | 24.69 | 83.39 | 24.1 | [76] |

| BCB10Br-C4PA | -5.63 | ITO/BCB10Br-C4PA/FA0.8Cs0.2Pb (I0.6Br0.4)3/C60/ALD-SnO2/Cu | 1.286 | 17.54 | 82.61 | 18.63 | [77] |

| four-terminal TSC:ITO/BCB10Br-C4PA/FA0.8Cs0.2Pb (I0.6Br0.4)3/C60 /ALD-SnO2/transparentelectrode/glass/ITO /PEDOT:PSS/ (FASnI3)0.6 (MAPbI3)0.4/C60/BCP/Cu |

1.264 | / | / | 26.24 | |||

| DCB-BPA | -5.56 | ITO/DCB-BPA/FA0.8Cs0.2PbI1.8Br1.2/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.33 | 17.75 | 82.70 | 19.53 | [78] |

| four-terminal TSC:ITO/DCB-BPA/FA0.8Cs0.2PbI1.8Br1.2/C60/SnO2 /IZO/transparentelectrode/glass/ITO/PEDOT:PSS/ (FASnI3)0.6 (MAPbI3)0.4/C60/BCP/Cu |

/ | / | / | 26.90 | |||

| CbzBF | -5.50 | ITO/CbzBF/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.09 | 24.00 | 83.04 | 21.72 | [79] |

| CbzBT | -5.54 | ITO/CbzBT/Cs0.05MA0.15FA0.80PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.16 | 24.54 | 84.41 | 24.04 | [79] |

| 4PACz | -5.43 | ITO/4PACz /Cs0.05 (FA0.98 MA0.02)0.95Pb I0.98 Br0.02 )3/LiF/C60 /BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 25.2 | 78.1 | 22.4 | [80] |

| Table 1 (Continued) | |||||||

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) |

JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref. |

| SAX | -5.49 | ITO/SAX/Cs0.05 (FA0.98 MA0.02)0.95Pb I0.98 Br0.02 )3/LiF/C60 /BCP/Ag | 1.17 | 25.7 | 83.4 | 25.1 | [80] |

| MeO-PhPACz | -5.61 | ITO/MeO-PhPACz/Cs0.05FA0.8MA0.15Pb (I0.75Br0.25)3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 24.83 | 82.0 | 23.24 | [81] |

| PPA | -5.28 | ITO/PPA/Cs0.05FA0.85MA0.1PbI3/OABr/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.10 | 24.70 | 79.2 | 21.52 | [82] |

| 1PATAT-C3 | -5.46 | ITO or FTO/1PATAT-C3/Cs0.05FA0.80MA0.15PbI2.75Br0.25/ EDAI2/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.06 | 24.00 | 82 | 21.1 | [83] |

| 2PATAT-C3 | -5.49 | ITO or FTO/2PATAT-C3/Cs0.05FA0.80MA0.15PbI2.75Br0.25/ EDAI2/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 23.3 | 83 | 22.2 | [83] |

| 3PATAT-C3 | -5.48 | ITO or FTO/3PATAT-C3/Cs0.05FA0.80MA0.15PbI2.75Br0.25/ EDAI2/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.13 | 24.5 | 83 | 23.0 | [83] |

| 3PATAT-C4 | -5.5 | ITO or FTO/3PATAT-C4/Cs0.05FA0.80MA0.15PbI2.75Br0.25/ EDAI2/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 23.3 | 83 | 22.1 | [83] |

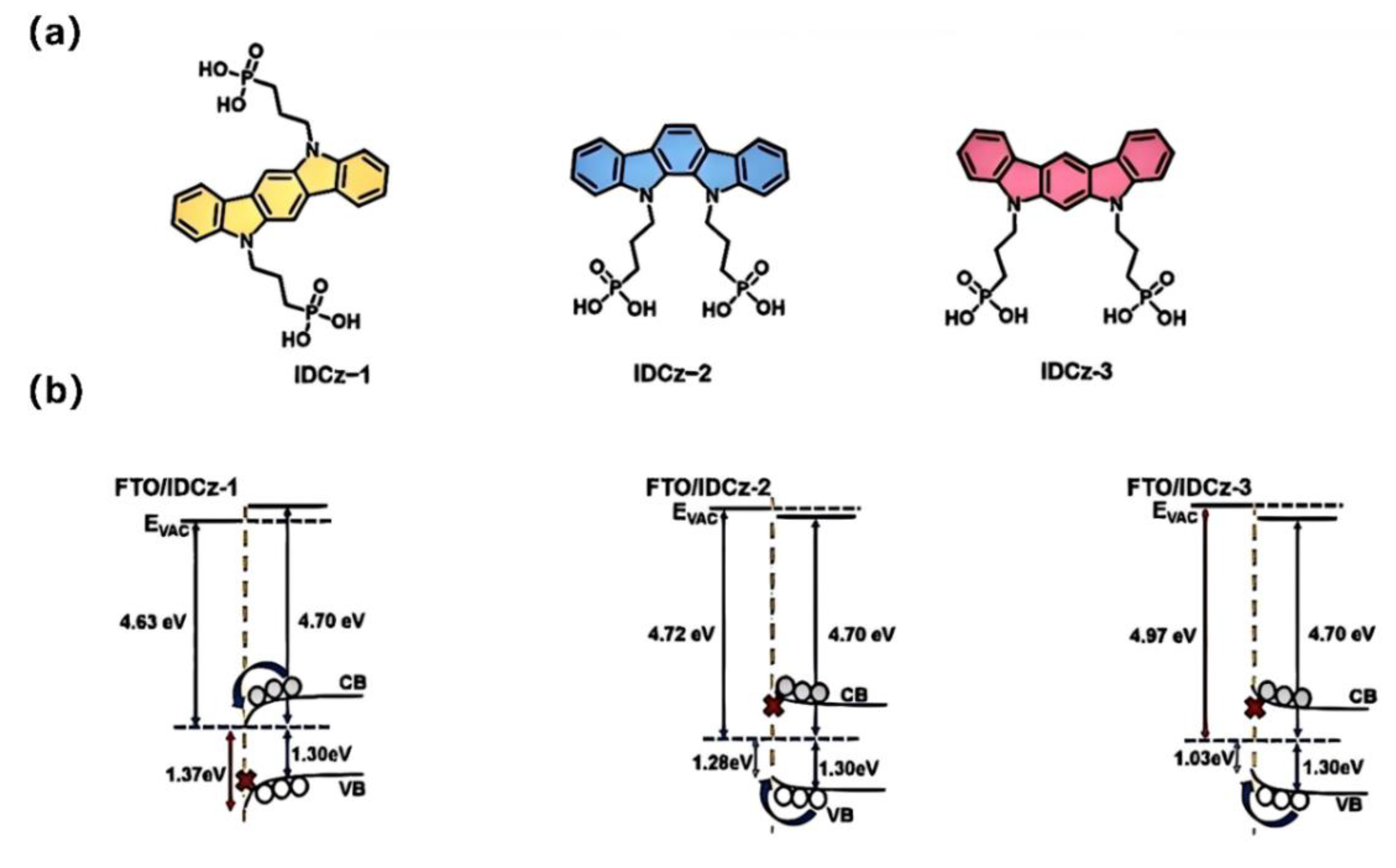

| IDCz-1 | -4.94 | FTO/ IDCz-1/Cs0.05FA0.85MA0.1PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.01 | 25.27 | 81.92 | 20.97 | [84] |

| IDCz-2 | -5.11 | FTO/ IDCz-2/Cs0.05FA0.85MA0.1PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.11 | 25.43 | 81.61 | 23.11 | [84] |

| IDCz-3 | -5.26 | FTO/ IDCz-3/Cs0.05FA0.85MA0.1PbI3/PI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.16 | 25.59 | 84.74 | 25.15 | [84] |

| D-3PACz | -5.06 | ITO/NiOx/D-3PACz/FAPbI3/PCBM/ BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 25.29 | 82.5 | 23.8 | [85] |

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

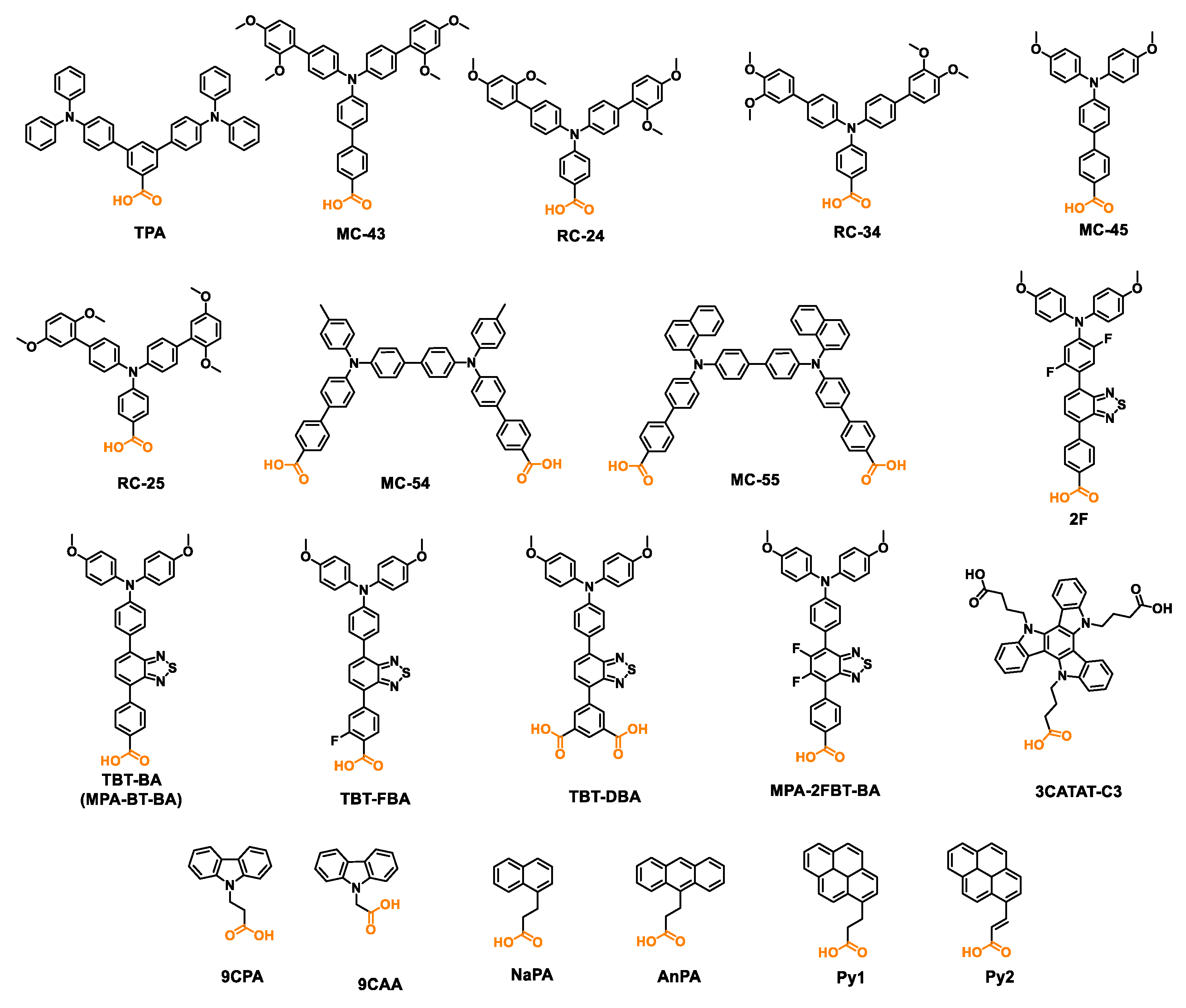

| TPA | -5.33 | ITO/TPA/MAPbI3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.06 | 19.4 | 77 | 15.9 | [86] |

| MC-43 | -5.11 | ITO/MC-43/MAPbI3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.07 | 20.3 | 80 | 17.3 | [86] |

| RC-24 | -5.13 | ITO/RC-24/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.123 | 22.3 | 79 | 19.8 | [87] |

| RC-25 | -5.22 | ITO/RC-25/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.116 | 22.1 | 79 | 19.6 | [87] |

| RC-34 | -5.32 | ITO/RC-34/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.109 | 22.5 | 79 | 19.7 | [87] |

| MC-45 | -5.12 | ITO/MC-45/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.09 | 20.56 | 74.35 | 16.69 | [88] |

| MC-54 | -5.16 | ITO/MC-54/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.10 | 22.32 | 79.15 | 19.52 | [88] |

| MC-55 | -5.26 | ITO/MC-55/Cs0.05FA0.79MA0.16Pb (I0.84Br0.16)3/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.09 | 21.90 | 79.32 | 18.99 | [88] |

| 2F | -5.42 | ITO/2F/FA0.8Cs0.2Pb (I0.6Br0.4)3/TEACl/C60/SnO2/Cu | 1.31 | 17.93 | 82.31 | 19.33 | [89] |

| ITO/2F/FA0.8Cs0.2Pb (I0.95Br0.05)3/TEACl/C60/SnO2/Cu | 1.15 | 23.59 | 82.42 | 22.36 | |||

| ITO/2F/FA0.6MA0.3Cs0.1Pb0.5Sn0.5I3/EDAI2/C60/SnO2/Cu | 0.872 | 32.55 | 81.89 | 23.24 | |||

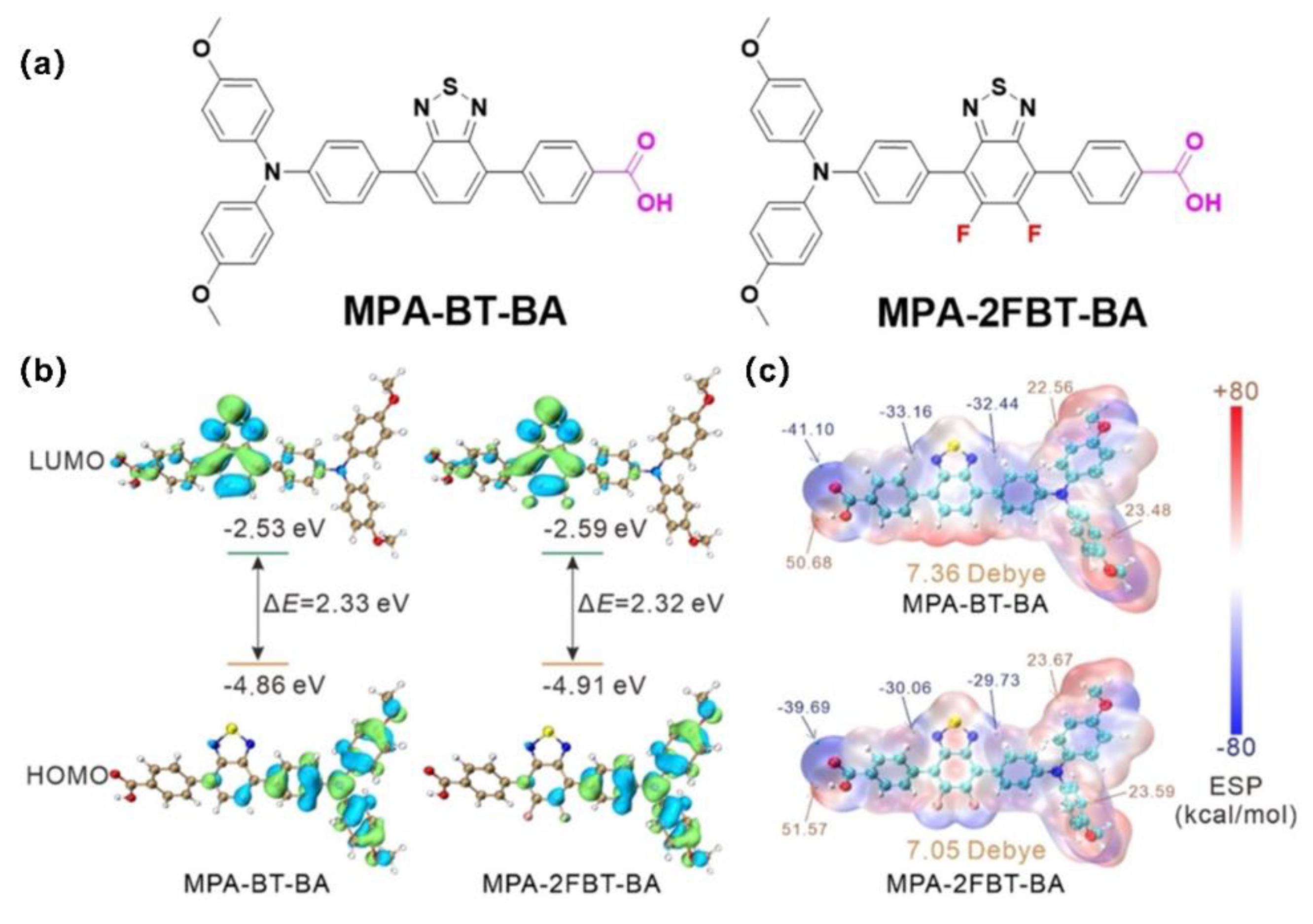

| TBT-BA | -5.10 | ITO/TBT-BA /Cs0.04 (FA0.96MA0.04)0.96Pb (I0.96Br0.04)3 /PEAI/PCBM/BCP/Ag |

1.19 | 24.9 | 83.7 | 24.8 | [90] |

| TBT-FBA | -5.15 | ITO/TBT-FBA /Cs0.04 (FA0.96MA0.04)0.96Pb (I0.96Br0.04)3 /PEAI/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.17 | 24.8 | 82.4 | 24.0 | [90] |

| Table 2 (Continued) | |||||||

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) |

JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref |

| TBT-DBA | -5.21 | ITO/TBT-DBA /Cs0.04 (FA0.96MA0.04)0.96Pb (I0.96Br0.04)3 /PEAI/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.13 | 25.0 | 81.5 | 23.1 | [90] |

| MPA-2FBT-BA | -4.91 | ITO/ MPA-2FBT-BA /MAPbI3/PC61BM/BCP/Ag | 1.13 | 22.79 | 78.95 | 20.32 | [91] |

| 3CATAT-C3 | -5.46 | ITO/3CATAT-C3 /Cs0.05FA0.80MA0.15PbI2.75Br0.25/EDAI2/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.11 | 25.1 | 83 | 23.1 | [92] |

| 9CPA | -5.19 | FTO/9CPA/Cs0.1FA0.6MA0.3Pb0.5Sn0.5I3/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.89 | 32.5 | 76 | 22.1 | [93] |

| 9CAA | -5.35 | FTO/9CAA/Cs0.1FA0.6MA0.3Pb0.5Sn0.5I3/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.89 | 32.8 | 79 | 23.1 | [93] |

| NaPA | -6.68 | ITO/ NaPA /FA0.9MA0.05Cs0.05PbI3/LiF/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.928 | 24.5 | 69.8 | 15.9 | [94] |

| AnPA | -6.07 | ITO/ AnPA /FA0.9MA0.05Cs0.05PbI3/LiF/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.017 | 24.6 | 76.5 | 19.1 | [94] |

| Py1 | -5.92 | ITO/ Py1/FA0.9MA0.05Cs0.05PbI3/LiF/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.095 | 25.0 | 81.3 | 22.3 | [94] |

| Py2 | -5.56 | ITO/ Py2/FA0.9MA0.05Cs0.05PbI3/LiF/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.151 | 26.1 | 84.1 | 25.2 | [94] |

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

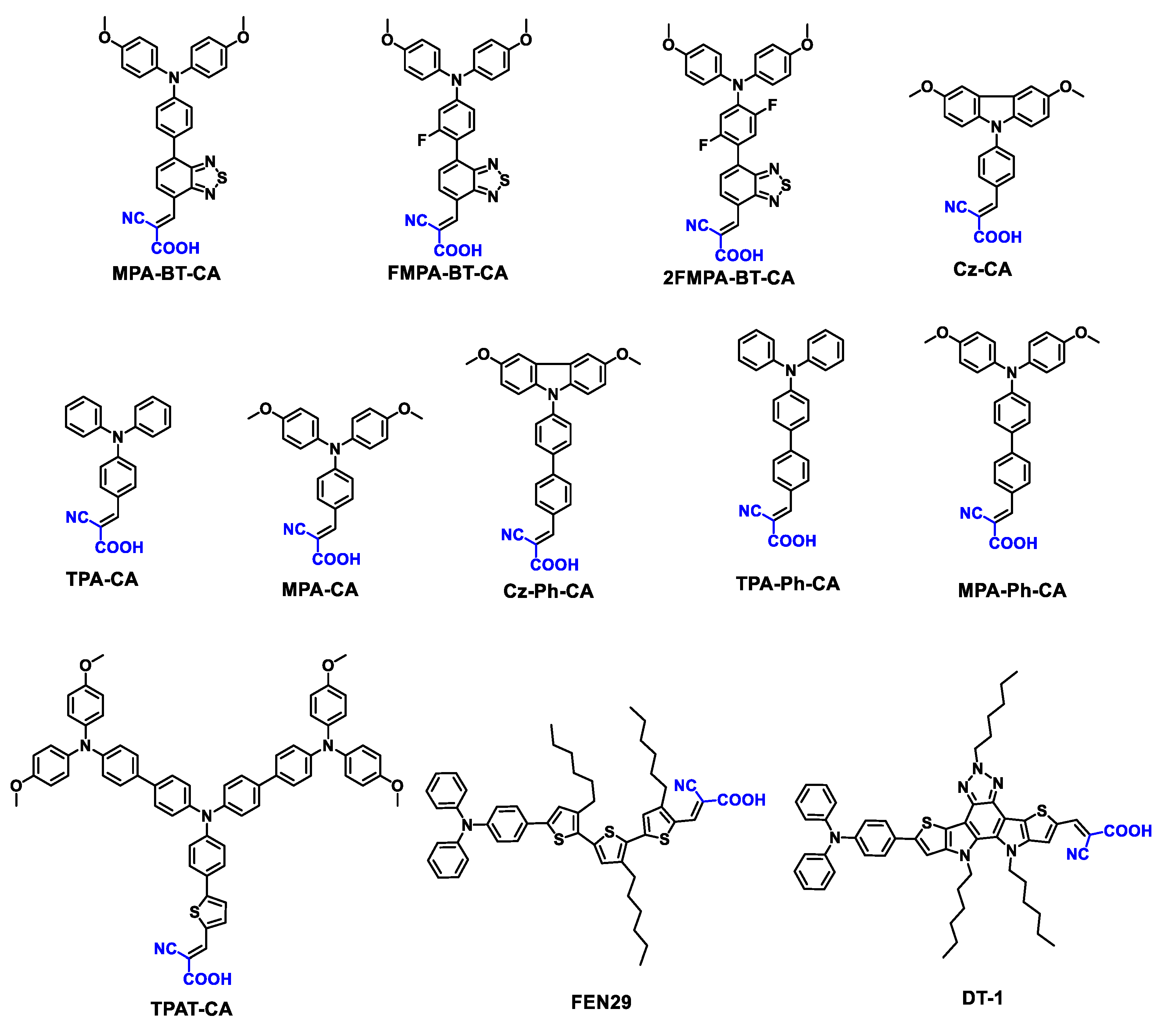

| MPA-BT-CA | -5.29 | ITO/MPA-BT-CA/ (FA0.17MA0.94PbI3.11)0.95 (PbCl2)0.05/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.13 | 22.25 | 84.8 | 21.24 | [95] |

| FMPA-BT-CA | -5.45 | ITO/FMPA-BT-RA/perovskite/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.151 | 23.33 | 83.3 | 22.37 | [56] |

| 2FMPA-BT-CA | -5.37 | ITO/2FMPA-BT-RA/perovskite/C60/BCP/Cu | 1.143 | 22.81 | 83.1 | 21.68 | [56] |

| Cz-CA | -5.72 | ITO/Cz-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3/PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag | / | / | / | 20.17 | [96] |

| TPA-CA | -5.87 | ITO/TPA-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3/PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag | / | / | / | 20.66 | [96] |

| MPA-CA | -5.45 | ITO/MPA-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3/PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag | / | / | / | 17.58 | [96] |

| Cz-Ph-CA | -5.53 | ITO/Cz-Ph-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3/PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag | / | / | / | 20.26 | [96] |

| TPA-Ph-CA | -5.61 | ITO/TPA-Ph-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3 /PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag |

/ | / | / | 20.36 | [96] |

| MPA-Ph-CA | -5.39 | ITO/MPA-Ph-CA/Cs0.05 (MA0.08FA0.92)0.95Pb (I0.92Br0.08)3 /PEAI/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag |

1.139 | 23.55 | 84.02 | 22.53 | [96] |

| Table 3 (Continued) | |||||||

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref |

| TPAT-CA | -5.24 | ITO/TPAT-CA/FASnI3/C60/BCP/Ag | 0.58 | 19.2 | 72.6 | 8.1 | [97] |

| FNE29 | -5.04 | ITO/FNE29/MAPbI3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.038 | 22.68 | 71.2 | 16.75 | [98] |

| DT-1 | -5.37 | ITO/DT-1/MAPbI3/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.11 | 23.00 | 80.9 | 20.65 | [98] |

| SAMs | HOMO (eV) | Device structure | VOC (V) | JSC (mA/cm2) |

FF (%) | PCE (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MTPA-BA | -5.48 | ITO/MTPA-BA/Cs0.05 (FA0.95MA0.05)0.95Pb (I0.95Br0.05)3/PCBM/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.14 | 23.24 | 85.2 | 22.62 | [99] |

| MPA-CAP | -5.4 | ITO/MPA-CAP/Cs0.05 (FA0.95MA0.05)0.95Pb (I0.95Br0.05)3/F-PEAI/C60/BCP/Ag | 1.21 | 24.78 | 84.7 | 25.4 | [37] |

| XS8 | -5.53 | ITO/ XS8/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.05 | 21.29 | 73.16 | 16.11 | [100] |

| XS9 | -5.49 | ITO/ XS9/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.02 | 22.27 | 71.32 | 15.77 | [100] |

| XS10 | -5.37 | ITO/ XS10/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 1.09 | 22.71 | 81.85 | 20.28 | [100] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).