Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Mycobacteria

2. Early Studies on Liposome-Encapsulated Antibiotics for Tuberculosis Therapy

3. Early Studies on Liposomal Antibiotic Therapy of Mycobacterium Avium-Mycobacterium Intracellulare Infections

4. Encapsulation of Antibiotics in Liposomes

5. Therapy of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection

6. Therapy of Non-Tuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

7. Future Directions, Challenges and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vilchèze, C.; Kremer, L. Acid-fast positive and acid-fast negative Mycobacterium tuberculosis: The Koch paradox. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 10.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Elías, E.J.; Timm, J.; Botha, T.; Chan, W.-T.; Gomez, J.E.; McKinney, J.D. Replication dynamics of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in chronically infected mice. Infection and Immunity 2005, 73, 546–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düzgüneş, N. Medical microbiology and immunology for dentistry. 2015.

- Daley, C.L.; Caminero, J.A. Management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. In Proceedings of the Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine; 2018; pp. 310–324. [Google Scholar]

- Matteelli, A.; Lovatti, S.; Rossi, B.; Rossi, L. Update on multidrug-resistant tuberculosis preventive therapy toward the global tuberculosis elimination. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocorullo, M.; Stamilla, A.; Recchia, D.; Marturano, M.C.; Maci, L.; Stelitano, G. Mycobacterium abscessus Virulence Factors: An Overview of Un-Explored Therapeutic Options. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palucci, I.; Delogu, G. Alternative therapies against Mycobacterium abscessus infections. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2024, 30, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vladimirsky, M.; Ladigina, G. Antibacterial activity of liposome-entrapped streptomycin in mice infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 1982, 36, 375–377. [Google Scholar]

- Ladigina, G.; Vladimirsky, M. The comparative pharmacokinetics of 3H-dihydrostreptomycin in solution and liposomal form in normal and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected mice. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 1986, 40, 416–420. [Google Scholar]

- Orozco, L.C.; Quintana, F.O.; Beltrán, R.M.; de Moreno, I.; Wasserman, M.; Rodriguez, G. The use of rifampicin and isoniazid entrapped in liposomes for the treatment of murine tuberculosis. Tubercle 1986, 67, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Kandpal, H.; Gupta, H.; Singh, N.; Gupta, C. Tuftsin-bearing liposomes as rifampin vehicles in treatment of tuberculosis in mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1994, 38, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgüneş, N.; Perumal, V.K.; Kesavalu, L.; Goldstein, J.A.; Debs, R.J.; Gangadharam, P. Enhanced effect of liposome-encapsulated amikacin on Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare complex infection in beige mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1988, 32, 1404–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynamon, M.; Swenson, C.; Palmer, G.; Ginsberg, R. Liposome-encapsulated-amikacin therapy of Mycobacterium avium complex infection in beige mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1989, 33, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez, L.E.; Vau-Young, A.O.; Lin, J.-P.; Cogger, J.; Young, L.S. Treatment of disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection of beige mice with liposome-encapsulated aminoglycosides. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1990, 161, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemens, S.; Cynamon, M.; Swenson, C.; Ginsberg, R. Liposome-encapsulated-gentamicin therapy of Mycobacterium avium complex infection in beige mice. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 1990, 34, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesavalu, L.; Goldstein, J.A.; Debs, R.J.; Düzgüneş, N.; Gangadharam, P.R. Differential effects of free and liposome encapsulated amikacin on the survival of Mycobacterium avium complex in mouse peritoneal macrophages. Tubercle 1990, 71, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Tomioka, H. Therapeutic efficacy of liposome-entrapped rifampin against Mycobacterium avium complex infection induced in mice. Antimicrobial \Agents and Chemotherapy 1989, 33, 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Düzgüneş, N.; Ashtekar, D.R.; Flasher, D.L.; Ghori, N.; Debs, R.J.; Friend, D.S.; Gangadharam, P.R. Treatment of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex infection in beige mice with free and liposome-encapsulated streptomycin: role of liposome type and duration of treatment. Journal of Infectious Diseases 1991, 164, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadharam, P.R.; Ashtekar, D.A.; Ghori, N.; Goldstein, J.A.; Debs, R.J.; Düzgüneş, N. Chemotherapeutic potential of free and liposome encapsulated streptomycin against experimental Mycobacterium avium complex infections in beige mice. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 1991, 28, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzuto, G.; Molinari, A. Liposomes as nanomedical devices. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S. Liposomes for drug delivery: review of vesicular composition, factors affecting drug release and drug loading in liposomes. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2023, 51, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraee, H.; Etemadi, A.; Kouhi, M.; Alimirzalu, S.; Akbarzadeh, A. Application of liposomes in medicine and drug delivery. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2014, 44, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgüneş, N.; Nir, S. Mechanisms and kinetics of liposome–cell interactions. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 1999, 40, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Aslanabadi, A.; Atkinson, B.; Hojabri, M.; Munawwar, A.; Zareidoodeji, R.; Ray, K.; Habibzadeh, P.; Parlayan, H.N.K.; DeVico, A.; et al. Subcutaneous liposomal delivery improves monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics in vivo. Acta Biomaterialia 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, H.; Pan, X.; Hu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, H.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, G.; et al. High molecular weight hyaluronic acid-liposome delivery system for efficient transdermal treatment of acute and chronic skin photodamage. Acta Biomaterialia 2024, 182, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yuan, H.; Guo, C.; Feng, Y.; Qi, P.; Yin, T.; Zhang, Y.; He, H.; et al. Milk exosome–liposome hybrid vesicles with self-adapting surface properties overcome the sequential absorption barriers for oral delivery of peptides. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 21091–21111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, Y.; Shen, W.; Zeng, Y.; Miao, Y.; Feng, N.; Ci, T. Effects of surface charge of inhaled liposomes on drug efficacy and biocompatibility. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konduri, K.S.; Nandedkar, S.; Düzgüneş, N.; Suzara, V.; Artwohl, J.; Bunte, R.; Gangadharam, P.R. Efficacy of liposomal budesonide in experimental asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2003, 111, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurtault, B.; Frisch, B.; Pons, F. Liposomes as delivery systems for nasal vaccination: strategies and outcomes. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2010, 7, 829–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S. Factors affecting response variables with emphasis on drug release and loading for optimization of liposomes. Artificial Cells, Nanomedicine, and Biotechnology 2024, 52, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadiyan, Z.; Misran, M.; Kalantari, K.; Webster, T.; Kia, P.; Basrowi, N.; Rasouli, E.; Shameli, K. Advancements in liposomal nanomedicines: innovative formulations, therapeutic applications, and future directions in precision medicine. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2025, Volume 20, 1213–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Park, J. Food liposomes: Structures, components, preparations, and applications. Food Chemistry 2024, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgüneş, N. Liposomes, Part G; Academic Press: 2009; Volume 465.

- Awasthi, V.D.; Garcia, D.; Goins, B.A.; Phillips, W.T. Circulation and biodistribution profiles of long-circulating PEG-liposomes of various sizes in rabbits. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2003, 253, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Tang, X.; Gui, Y.; Lu, S.; Song, Y.; Deng, Y. Impact of formulation parameters and circulation time on PEGylated liposomal doxorubicin related hand-foot syndrome. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Liu, Y.; Fan, M.; Wei, S.; Ismail, M.; Zheng, M. PEG length effect of peptide-functional liposome for blood brain barrier (BBB) penetration and brain targeting. Journal of Controlled Release 2024, 372, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, J.; Umstätter, F.; Hertlein, T.; Mühlberg, E.; Beijer, B.; Wohlfart, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Haberkorn, U.; Ohlsen, K.; Fricker, G.; et al. Oral delivery of the vancomycin derivative FU002 by a surface-modified liposomal nanocarrier. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; He, Q. Synergistic cytotoxicity and co-autophagy inhibition in pancreatic tumor cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts by dual functional peptide-modified liposomes. Acta Biomaterialia 2019, 99, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshid, S.; Montanari, M.; Benedetti, S.; Moroni, S.; Aluigi, A.; Canonico, B.; Papa, S.; Tiboni, M.; Casettari, L. A microfluidic approach to fabricate sucrose decorated liposomes with increased uptake in breast cancer cells. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2022, 178, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban-Chmiel, R.; Marek, A.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Wieczorek, K.; Dec, M.; Nowaczek, A.; Osek, J. Antibiotic resistance in bacteria—a review. Antibiotics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

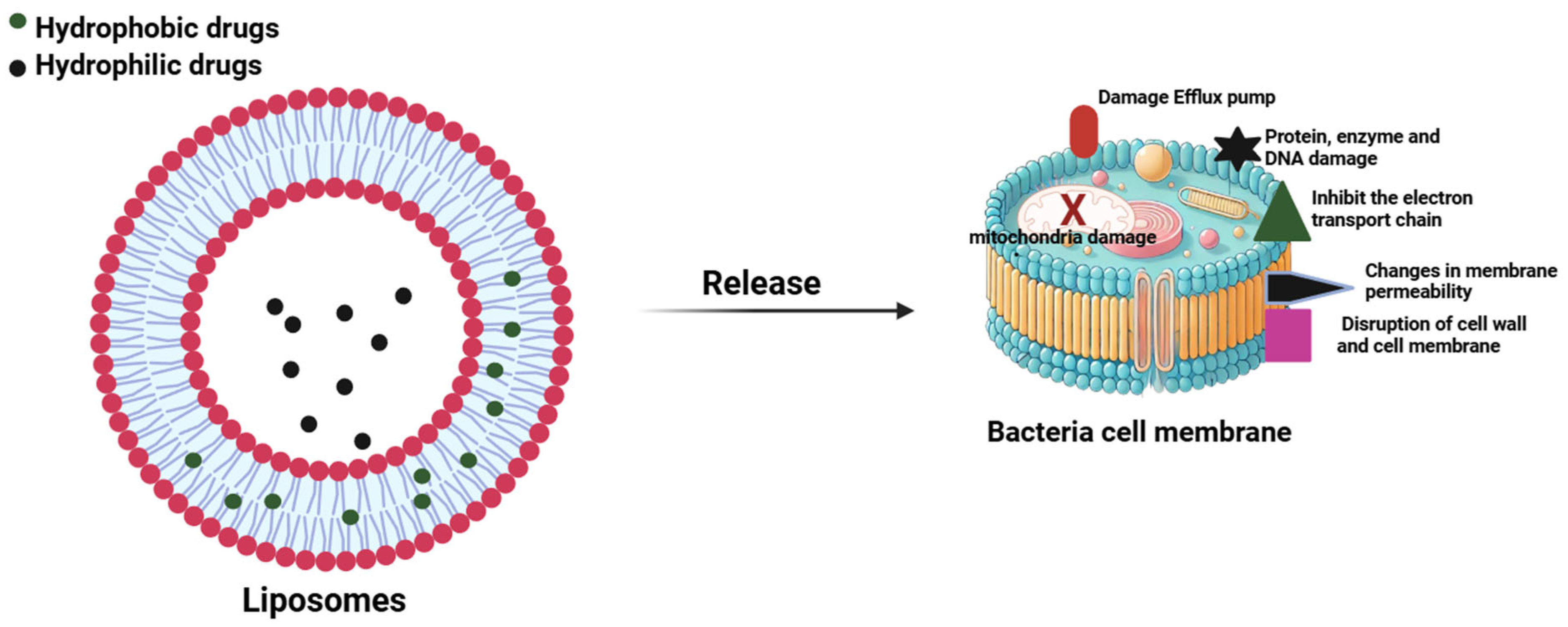

- Ferreira, M.; Ogren, M.; Dias, J.N.R.; Silva, M.; Gil, S.; Tavares, L.; Aires-da-Silva, F.; Gaspar, M.M.; Aguiar, S.I. Liposomes as antibiotic delivery systems: a promising nanotechnological strategy against antimicrobial resistance. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; De, M. Liposome-based antibacterial delivery: an emergent approach to combat bacterial infections. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 35442–35451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Kumar, S.; Singh, S.; Wani, M.Y. Overcoming resistance: Chitosan-modified liposomes as targeted drug carriers in the fight against multidrug resistant bacteria–a review. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, M.; Pinto, S.N.; Aires-da-Silva, F.; Bettencourt, A.; Aguiar, S.I.; Gaspar, M.M. Liposomes as a nanoplatform to improve the delivery of antibiotics into Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.E.; Koohi Moftakhari Esfahani, M.; Raza, A.; Adelnia, H.; Ebrahimi Shahmabadi, H. PEG-grafted liposomes for enhanced antibacterial and antibiotic activities: An in vivo study. NanoImpact 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trucillo, P.; Ferrari, P.F.; Campardelli, R.; Reverchon, E.; Perego, P. A supercritical assisted process for the production of amoxicillin-loaded liposomes for antimicrobial applications. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2020, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.P.; Pinho, J.O.; Pinto, S.N.; Gaspar, M.M. A step forwarded on the in vitro and in vivo validation of rifabutin-loaded liposomes for the management of highly virulent MRSA infections. Journal of Controlled Release 2025, 380, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Dey, S.; Shokeen, K.; Karpiński, T.M.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Kumar, S.; Manna, D. Sulfonium-based liposome-encapsulated antibiotics deliver a synergistic antibacterial activity. RSC Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 12, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpuz, M.; Temel, A.; Özgenç, E.; Tekintaş, Y.; Erel-Akbaba, G.; şenyigit, Z.; Atlıhan-Gündogdu, E. 99mTc-labeled, colistin encapsulated, theranostic liposomes for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Xu, C.; Cui, L.; Meng, G.; Yang, S.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Guo, X. PEG-α-CD/AM/liposome@ amoxicillin double network hydrogel wound dressing–multiple barriers for long-term drug release. Journal of Biomaterials Applications 2021, 35, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesendouz, S.A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Alizadeh, E.; Rahbarghazi, R.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Yousefi, S.; Milani, M. Bactericidal activity and biofilm eradication of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by liposome-encapsulated piperacillin/tazobactam. BioNanoScience 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdene, E.; Munkhjargal, O.; Batnasan, G.; Dorjbal, E.; Oidov, B.; Byambaa, A. Evaluation of liposome-encapsulated vancomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomedicines 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trucillo, P.; Cardea, S.; Baldino, L.; Reverchon, E. Production of liposomes loaded alginate aerogels using two supercritical CO2 assisted techniques. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.; Janovák, L.; Vraneš, J.; Meštrović, T.; Ljubin-Sternak, S.; Cseh, Z.; Endrész, V.; Burián, K.; Vanić, Ž.; Virok, D.P. Liposomal encapsulation increases the efficacy of azithromycin against Chlamydia trachomatis. Pharmaceutics 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Zou, P.; Chai, G.; Lin, Y.-W.; Velkov, T.; Li, J.; Pan, W.; Zhou, Q.T. Inhalable liposomal powder formulations for co-delivery of synergistic ciprofloxacin and colistin against multi-drug resistant Gram-negative lung infections. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wu, T.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, W.; Chen, L.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, L.; Yu, X.; et al. Chitosan-coated liposome with lysozyme-responsive properties for on-demand release of levofloxacin. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Ramirez, L.M.; Mehaffy, C.; Dobos, K.M. Systematic review of innate immune responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex infection in animal models. Frontiers in Immunology 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, S.S.R.; Gunosewoyo, H. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, current treatment regimens and new drug targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

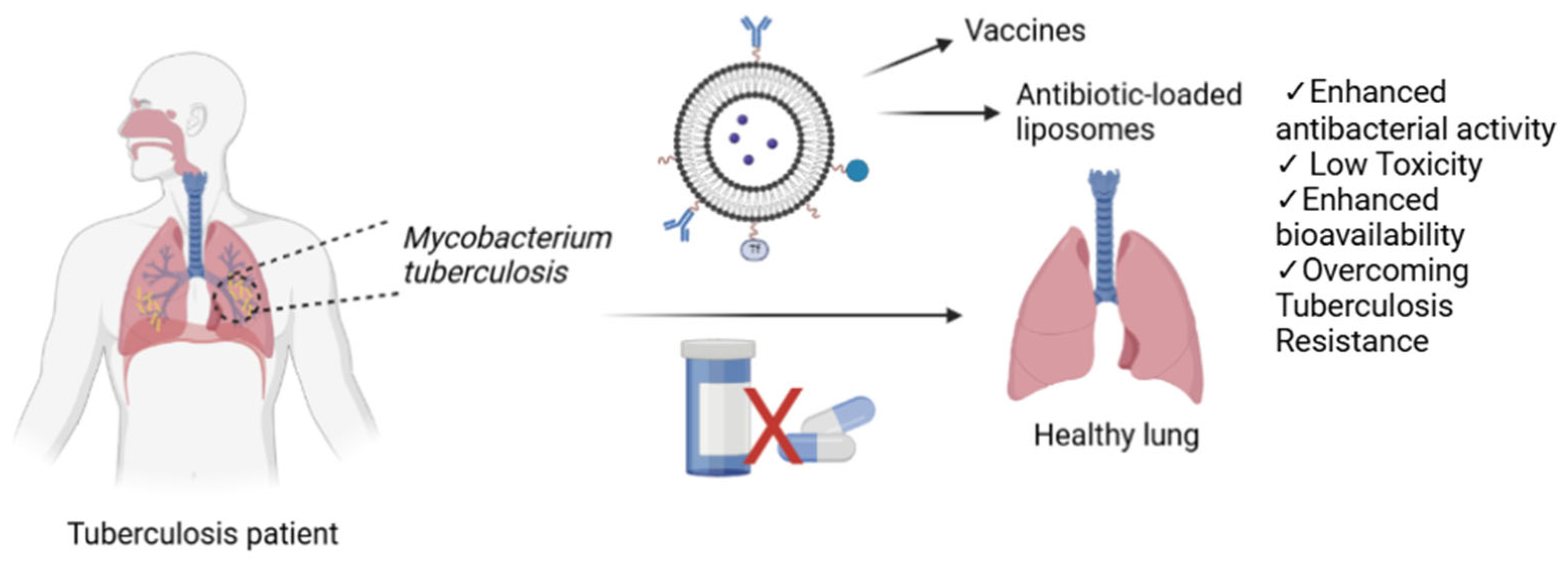

- Tretiakova, D.S.; Vodovozova, E.L. Liposomes as adjuvants and vaccine delivery systems. Biochemistry (Moscow), Supplement Series A: Membrane and Cell Biology 2022, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, G.R.; Hart, P.; Copland, A.; Kim, M.-Y.; Tran, A.C.; Poerio, N.; Singh, M.; Paul, M.J.; Fraziano, M.; Reljic, R. Immunization with Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigens encapsulated in phosphatidylserine liposomes improves protection afforded by BCG. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansury, D.; Ghazvini, K.; Jamehdar, S.A.; Badiee, A.; Tafaghodi, M.; Nikpoor, A.R.; Amini, Y.; Jaafari, M.R. Increasing cellular immune response in liposomal formulations of DOTAP encapsulated by fusion protein Hspx, PPE44, and Esxv, as a potential tuberculosis vaccine candidate. Reports of Biochemistry & Molecular Biology 2019, 7, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Luo, Y.; Lovell, J.F. Vaccine approaches for antigen capture by liposomes. Expert Review of Vaccines 2023, 22, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, V.K.; Fairfull-Smith, K.E.; Islam, N. Antibiotic loaded inhalable liposomal nanoparticles against lower respiratory tract infections: challenges, recent advances, and future perspectives. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2024, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, N.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, G.; Li, R.; Zhang, J. Bacteria-targeting liposomes for enhanced delivery of cinnamaldehyde and infection management. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2022, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justo, O.R.; Moraes, Â.M. Incorporation of antibiotics in liposomes designed for tuberculosis therapy by inhalation. Drug Delivery 2003, 10, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim Bekraki, A. Liposomes-and niosomes-based drug delivery systems for tuberculosis treatment. In Nanotechnology Based Approaches for Tuberculosis Treatment; 2020; pp. 107-122.

- Al-Jipouri, A.; Almurisi, S.H.; Al-Japairai, K.; Bakar, L.M.; Doolaanea, A.A. Liposomes or extracellular vesicles: a comprehensive comparison of both lipid bilayer vesicles for pulmonary drug delivery. Polymers 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Chaturvedi, S.; Attri, A.; Kalra, M.; Mishra, A.K. Targeted theranostic liposomes: rifampicin and ofloxacin loaded pegylated liposomes for theranostic application in mycobacterial infections. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 28919–28926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamimi, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Imam, S.S.; Alshehri, S.; Singh, S.K.; Webster, T.J. Transdermal delivery of isoniazid loaded elastic liposomes to control cutaneous and systemic tuberculosis. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2020, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ridy, M.S.; Mostafa, D.M.; Shehab, A.; Nasr, E.A.; Abd El-Alim, S. Biological evaluation of pyrazinamide liposomes for treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2007, 330, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimote, G.; Banerjee, R. Evaluation of antitubercular drug-loaded surfactants as inhalable drug-delivery systems for pulmonary tuberculosis. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2008, 89A, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nongkhlaw, R.; Nongrum, R.; Arunachalam, J.; Kalia, N.P.; Agnivesh, P.K.; Nongkhlaw, R. Drug-loaded liposomes for macrophage targeting in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: development, characterization and macrophage infection study. 3 Biotech 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Gautam, L.; Sharma, R.; Dube, D.; Vyas, S.; Vyas, S.P. Dual antitubercular drug loaded liposomes for macrophage targeting: development, characterisation, ex vivo and in vivo assessment. Journal of Microencapsulation 2020, 38, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kósa, N.; Zolcsák, Á.; Voszka, I.; Csík, G.; Horváti, K.; Horváth, L.; Bősze, S.; Herenyi, L. Comparison of the efficacy of two novel antitubercular agents in free and liposome-encapsulated formulations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-F.; Niu, N.-K.; Yin, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.-L.; Zhou, Z.-W.; He, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-W.; Zhang, X.; Duan, W.; et al. Novel targeting of PEGylated liposomes for codelivery of TGF-β1 siRNA and four antitubercular drugs to human macrophages for the treatment of mycobacterial infection: a quantitative proteomic study. Drug Design, Development and Therapy 2015. [CrossRef]

- Obiedallah, M.M.; Melekhin, V.V.; Menzorova, Y.A.; Bulya, E.T.; Minin, A.S.; Mironov, M.A. Fucoidan coated liposomes loaded with novel antituberculosis agent: preparation, evaluation, and cytotoxicity study. Pharmaceutical Development and Technology 2024, 29, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima Salviano, T.; dos Santos Macedo, D.C.; de Siqueira Ferraz Carvalho, R.; Pereira, M.A.; de Arruda Barbosa, V.S.; dos Santos Aguiar, J.; Souto, F.O.; Carvalho da Silva, M.d.P.; Lapa Montenegro Pimentel, L.M.; Correia de Sousa, L.d.Â.; et al. Fucoidan-coated liposomes: a target system to deliver the antimicrobial drug usnic Acid to macrophages infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2021, 17, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szachniewicz, M.M.; van den Eeden, S.J.F.; van Meijgaarden, K.E.; Franken, K.L.M.C.; van Veen, S.; Geluk, A.; Bouwstra, J.A.; Ottenhoff, T.H.M. Cationic pH-sensitive liposome-based subunit tuberculosis vaccine induces protection in mice challenged with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2024, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.P.; Kannan, M.E.; Jain, S.; Mishra, V.; Singh, P. Design of liposomal aerosols for improved delivery of rifampicin to alveolar macrophages. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2004, 269, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, V.V.; Kuzin, V.V.; Vladimirsky, M.A.; Vasilieva, I.A.E. Experimental studies of the liposomal form of lytic mycobacteriophage D29 for the treatment of tuberculosis infection. Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, S.L.; Reese, V.A.; Larsen, S.E.; Pecor, T.; Brown, B.P.; Granger, B.; Podell, B.K.; Fox, C.B.; Reed, S.G.; Coler, R.N. Therapeutic efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis using ID93 and liposomal adjuvant formulations. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maringolo Ribeiro, C.; Augusto Roque-Borda, C.; Carolina Franzini, M.; Fernanda Manieri, K.; Manaia Demarqui, F.; Leite Campos, D.; Temperani Amaral Machado, R.; Cristiane da Silva, I.; Tavares Luiz, M.; Delello Di Filippo, L.; et al. Liposome-siderophore conjugates loaded with moxifloxacin serve as a model for drug delivery against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2024, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.; Mandal, M.; Pinho, J.; Catalão, M.J.; Almeida, A.J.; Azevedo-Pereira, J.M.; Gaspar, M.M.; Anes, E. Liposomal delivery of saquinavir to macrophages overcomes cathepsin blockade by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and helps control the phagosomal replicative niches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, F.; Hanieh, P.N.; Sennato, S.; De Santis, F.; Forte, J.; Fraziano, M.; Casciardi, S.; Marianecci, C.; Bordi, F.; Carafa, M. Rifampicin-liposomes for Mycobacterium abscessus infection treatment: intracellular uptake and antibacterial activity evaluation. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.; Cao, R.; Yegiazaryan, A.; Owens, J.; Nguyen, T.; Sasaninia, K.; Vaughn, C.; Singh, M.; Truong, E.; Medina, A.; et al. Effects of oral liposomal glutathione in altering the immune responses against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the Mycobacterium bovis BCG strain in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnath, S.; Rajan, M.; Jeyaraj, M. Immunomodulating polyorganophosphazene-arginine layered liposome antibiotic delivery vehicle against pulmonary tuberculosis. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Guo, B.; Wang, S.; Ding, J.; Zhou, W. A thermo-responsive and self-healing liposome-in-hydrogel system as an antitubercular drug carrier for localized bone tuberculosis therapy. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2019, 558, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miretti, M.; Juri, L.; Cosiansi, M.C.; Tempesti, T.C.; Baumgartner, M.T. Antimicrobial effects of ZnPc delivered into liposomes on multidrug resistant (MDR)-Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 9726–9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciolla, F.; Truzzolillo, D.; Chauveau, E.; Trabalzini, S.; Di Marzio, L.; Carafa, M.; Marianecci, C.; Sarra, A.; Bordi, F.; Sennato, S. Influence of drug/lipid interaction on the entrapment efficiency of isoniazid in liposomes for antitubercular therapy: a multi-faced investigation. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2021, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, A.A.; Baldwin, S.L.; Reese, V.A.; Larsen, S.E.; Beebe, E.; Guderian, J.; Orr, M.T.; Fox, C.B.; Reed, S.G.; Coler, R.N. Prophylactic efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis using ID93 and lipid-based adjuvant formulations in the mouse model. Plos One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, L.; Viljoen, J.M.; Haynes, R.K.; Aucamp, M.; Ngwane, A.H.; du Plessis, J. Topical delivery of artemisone, clofazimine and decoquinate encapsulated in vesicles and their in vitro efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkanga, C.I.; Krause, R.W.M. Encapsulation of Isoniazid-conjugated phthalocyanine-in-cyclodextrin-In-Liposomes Using Heating Method. Scientific Reports 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truzzi, E.; Meneghetti, F.; Mori, M.; Costantino, L.; Iannuccelli, V.; Maretti, E.; Domenici, F.; Castellano, C.; Rogers, S.; Capocefalo, A.; et al. Drugs/lamellae interface influences the inner structure of double-loaded liposomes for inhaled anti-TB therapy: An in-depth small-angle neutron scattering investigation. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2019, 541, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.M.; Odell, J.A. Nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infections. Journal of thoracic disease 2014, 6, 210. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, S.; Bucke, W.; Leitzke, S.; Fortmann, L.; Smith, D.; Hänsch, H.; Hahn, H.; Bancroff, G.; Müller, R. Liposomal amikacin for treatment of M. avium infections in clinically relevant experimental settings. Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie 1996, 284, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Leifer, F.; Rose, S.; Chun, D.Y.; Thaisz, J.; Herr, T.; Nashed, M.; Joseph, J.; Perkins, W.R.; DiPetrillo, K. Amikacin liposome inhalation suspension (ALIS) penetrates non-tuberculous mycobacterial biofilms and enhances amikacin uptake into macrophages. Frontiers in Microbiology 2018, 9, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loukeri, A.A.; Papathanassiou, E.; Kavvada, A.; Kampolis, C.F.; Pantazopoulos, I.; Moschos, C.; Papavasileiou, A. Amikacin liposomal inhalation suspension for non-tuberculous mycobacteria lung infection: a Greek observational study. Medicina 2024, 60, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Drug | Method | Size | Target | Remarks | References |

| Rifabutin | Dehydration-rehydration | 100–115 nm | MRSA biofilm | Rifabutin-loaded liposomal formulations demonstrated superior efficacy compared to free vancomycin | [47] |

| Tetracycline, Amoxicillin | - | 270–340 nm | MRSA | Drug-loaded liposomes enhance the cellular uptake of antibiotics, thereby providing more effective treatment compared to their free forms. | [48] |

| Colistin | Thin layer hydration | 73–217 nm | Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection | Colistin-loaded cationic liposomes, with an encapsulation efficiency of 77%, had low MIC values against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. | [49] |

| Amoxicillin | Film hydration method | 210 nm | Staphylococcus aureus infection | Amoxicillin-loaded PEG--cyclodextrin- acrylamide-liposomes were incorporated into biocompatible hydrogels to prepare a wound dressing. The formulation demonstrated controlled drug release and effective antibacterial activity. | [50] |

| Piperacillin sodium | Film hydration method | 94.49 nm | Antibiotic resistance of clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Liposome-loaded Piperacillin exhibited superior antibacterial activity at a lower MIC value compared to its free form. | [51] |

| Vancomycin | Freeze–thaw method | 157 nm | MRSA | At a 1:102 dilution, free vancomycin failed to inhibit bacterial growth, whereas the liposome-loaded form achieved 100% inhibition. | [52] |

| Ampicillin | SuperLip | 200 nm | - | Ampicillin-loaded liposomes were entrapped in alginate gels. This method resulted in enhanced encapsulation efficiency and improved polydispersity index values, indicating a more effective formulation. | [53] |

| Azithromycin | Proliposome | 164- 187 nm | Chlamydia trachomatis | The formulations exhibited at least twofold higher activity compared to the free form against both clinical isolates and bacterial strains. | [54] |

| Ciprofloxacin and colistin | Thin film evaporation and sonication | 102.1- 119.7 nm | Clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa H131300444 and P. aeruginosa H133880624 | The formulation exhibited effective antibacterial properties against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterium responsible for pulmonary infections, while showing no cytotoxic effects on A549 cells. However, the encapsulation efficiency for both drugs remained below 50%. | [55] |

| Levofloxacin | Film hydration method | 127.6 nm | Staphylococcus aureus | Levofloxacin-loaded liposome formulations were coated with chitosan (CS). Following CS coating, an increase in particle size was observed, along with an enhancement in antibacterial activity. | [56] |

| Drug | Method | Size | Remarks | References |

| Cationic pH-sensitive liposome | Thin-film hydration | 164.6 nm | pH-sensitive cationic liposomes formulated with the Ag85B-ESAT6-Rv2034 fusion antigen and CpG and MPLA adjuvants have been shown to induce potent polyfunctional CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T-cell responses. Additionally, an increase in CD69⁺ B-cell sub-populations was observed. | [78] |

| Anionic and neutral liposomes | - | For improved pulmonary TB treatment, ID93 plus GLA-containing liposomal adjuvant formulations were developed. However, the anionic or neutral liposome + QS-21 liposomal formulations did not result in a significant reduction in M. tuberculosis bacterial load. Nevertheless, these formulations were observed to induce distinct immune responses. | [81] | |

| Moxifloxacin loaded liposome-siderophore conjugates | Film hydration technique | 200 nm | Liposome formulations with a spherical shape had an encapsulation efficiency of 46 % and demonstrated anti-TB activity with a MIC value of 0.32 µg/mL. | [82] |

| Saquinavir | Thin-film hydration | 116 nm | In the treatment of multidrug- and extensively drug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains, negatively charged Saquinavir-loaded liposomes were shown to enhance intracellular killing activity by human macrophages. | [83] |

| Rifampicin | Thin-Layer Evaporation | 117 nm | The prepared formulation demonstrated a greater reduction in intracellular M. abscessus viability compared to the free form of the drug. | [84] |

| Oral liposomal glutathione supplementation | - | - | Commercially available liposomal glutathione supplementation (L-GSH) has been shown to reduce oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). In vitro models have demonstrated its ability to decrease intracellular mycobacteria. | [85] |

| Rifampicin and isoniazid |

Lipid film hydration, sonication and extrusion | - | Antibiotic loaded, polyorganophosphazene-arginine-grafted liposomes exhibited a 73% RIF and 80% IZN release at endosomal pH. The liposomes demonstrated a dose-dependent inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in culture medium. | [86] |

| N′-Dodecanoylisonicotinohydrazide | ∼130 nm | For use in localized tuberculosis treatment, the Isoniazid derivative N′dodecanoylisonicotinohydrazide, a commonly used agent in tuberculosis therapy, was loaded into liposomes. PLGA-PEG-PLGA systems were incorporated to develop thermosensitive and self-healing hydrogel systems. Data obtained from in vivo microdialysis studies demonstrated the rapid release of the drug into the synovial fluid. | [87] | |

| Coumaran (2,3-dihydrobenzofuran) derivatives—TB501 and TB515— | Thin film hydration | ∼60 nm | The liposome formulation prepared with TB515 exhibited high encapsulation efficiency. Multicomponent pH-sensitive stealth liposomes encapsulating TB501 were highly effective against M. tuberculosis in macrophage cell lines. | [74] |

| Zn-phthalocyanine | Ethanol injection | 134 nm | ZnPC-loaded liposomes, prepared for the treatment of Rifampin-Isoniazid-resistant M. tuberculosis strains, achieved a 99.9% cell death rate in vitro through photodynamic therapy (PDT). | [88] |

| Isoniazid | Thin-film hydration | 37–45 nm | Biocompatible hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine-phosphatidylglycerol liposomes were developed as isoniazid carriers. The encapsulation efficiency was determined using UV and Laser Transmission Spectroscopy. | [89] |

| Glucopyranosyl lipid adjuvant (GLA) and the experimental tuberculosis vaccine, ID93, composed of four M. tuberculosis antigens |

Thin-film hydration, sonication, homogenization | 50–87 nm | For use as a vaccine in the treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, formulations containing a TLR4 agonist (GLA) and QS21, in combination with ID93, were developed. In an in vivo model, these formulations demonstrated a reduction in bacterial load in the lungs of mice infected with M. tuberculosis. Clinical studies involving human participants are ongoing to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the developed formulations. | [90] |

| Artemisone, Clofazimine and Decoquinate | Thin-film hydration | 147, 482, 253 nm |

Drug-loaded liposomes, synthesized in various sizes, exhibited 32–42% inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in culture medium. By contrast, drug-free liposomes induced only 12% inhibition. | [91] |

| Isoniazid-conjugated Phthalocyanine | “Heating Method” | 150–650 nm | A complex of γ-Cyclodextrin with Isoniazid-conjugated Phthalocyanine, was incorporated into crude soybean lecithin liposomes using a simple and measurable heating method. This pH-sensitive formulation exhibited 100% drug release at pH 4.4, while releasing only 40% at pH 7.4, demonstrating its potential applicability in targeted therapies. | [92] |

| Isoniazid and Rifampicin | Reverse Phase Evaporation | 332 - 361 nm | Liposomal formulations loaded with anti-TB drugs Isoniazid, Rifampicin, and their combination were developed for inhaled therapy. Isoniazid formulations exhibited a faster release compared to Rifampicin formulations, while their encapsulation efficiencies were found to be similar. | [93] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).