1. Introduction

The exponential growth of digital information over the past two decades has fundamentally transformed how organizations manage, store, and analyze data [

1,

2,

3]. As industries such as finance, healthcare, and government expand their digital footprints, they increasingly rely on Data Lakes—scalable, flexible storage architectures capable of managing vast volumes of structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data [

4,

5]. Data Lakes offer opportunities for comprehensive analytics and innovation but simultaneously introduce new challenges related to data security, privacy preservation, and regulatory compliance [

6,

7].

In parallel, the accelerated adoption of cloud computing and distributed processing platforms, such as Databricks, has further reshaped the data landscape, enabling organizations to perform complex analytics on massive datasets more efficiently [

8]. However, this growing computational capacity comes with heightened risks. The handling of sensitive personal and financial information at scale, often in hybrid or multicloud environments, increases the attack surface for cyber threats and subjects organizations to stricter regulatory scrutiny [

9,

10].

Security breaches, data misuse, and non-compliance with data protection regulations such as GDPR can have devastating legal and reputational consequences. Recognizing these risks, the paradigm of Secure by Design has gained traction. This approach advocates integrating security mechanisms into every stage of system development, from the earliest architectural decisions to deployment and operation [

9,

11]. Unlike traditional perimeter-based security strategies, Secure by Design frameworks promote resilience, adaptability, and the minimization of vulnerabilities from inception.

Among the techniques developed to protect sensitive information in complex data environments, Format-Preserving Encryption (FPE) has emerged as a particularly promising solution [

12,

13]. By encrypting data without altering its original format, FPE enables the preservation of database schema integrity and the compatibility of encrypted data with existing analytics workflows. Its relevance has grown in sectors where maintaining the usability of data while ensuring its confidentiality is crucial, such as in banking environments handling customer financial data [

14,

15].

Despite advances in Big Data infrastructure, encryption techniques, and data governance frameworks, some existing solutions address these challenges in a fragmented manner, often applying security mechanisms such as strong encryption or data obfuscation that compromise the usability of the data for analytical purposes. This trade-off becomes particularly problematic in contexts that require both data protection and analytical continuity, such as financial or healthcare environments where insights must be derived from sensitive data. The absence of such integrated, Secure-by-Design approaches capable of balancing protection with usability highlights a critical gap in current Data Lake implementations.

To address this gap, this paper proposes a Secure-by-Design protocol for managing sensitive data in Data Lakes. The protocol uses Databricks’ distributed processing capabilities, Delta Lake storage optimization, and FPE techniques to enhance data security and governance without compromising analytic usability. The methodology adopted follows the Design Science Research approach [

16,

17], ensuring a structured, iterative development and validation process based on both theoretical foundations and practical experimentation.

This paper consists of the following sections:

Section 2 contains the background concepts that underpin the proposed solution, including data portability, Secure by Design principles, Data Lake architectures, ingestion strategies, and encryption techniques.

Section 3 describes the methodology applied to design and validate the protocol.

Section 4 details the protocol architecture and its components.

Section 5 presents the results of the validation and expert feedback. Finally,

Section 6 discusses the implications of the findings and challenges encountered.

2. Background

The development of a protocol for data portability in banking environments poses unique challenges, given the need to balance regulatory compliance, data security, and system interoperability. To address these challenges, it is essential to explore key concepts that form the foundation of this research. Data Portability ensures that users retain control over their data and that it can be transferred between systems securely and seamlessly. The Secure by Design approach is particularly relevant in banking, where integrating security into every stage of system development is critical to safeguard sensitive financial information.

Additionally, the technical infrastructure supporting the protocol—such as Data Lake Architecture, Data Ingestion processes, and Data Governance frameworks—plays a pivotal role in ensuring the secure and efficient management of data portability. Advanced encryption techniques, such as Format-Preserving Encryption (FPE), are also central to enabling the secure handling of sensitive banking data without compromising usability. The following sections provide an in-depth exploration of these topics, reviewing the literature and establishing the conceptual framework for the proposed protocol.

2.1. Data Portability and Interoperability in the Context of Cloud Computing and Data Protection

Data portability and interoperability are closely related concepts within the domains of data protection and cloud computing. Data portability is a key provision of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), granting users the right to transfer their personal data across different online services [

18,

19]. This principle not only enhances user control over personal information but also promotes interoperability among digital platforms by enabling data to be reused across different systems.

In the context of cloud computing, data portability extends beyond the mere transfer of files. Applications often require data to be formatted in specific ways to ensure correct functionality. Therefore, it is essential to guarantee that both structured and unstructured data are accessible and compatible with the systems that will process them upon migration. Achieving this requires the implementation of standards that govern data export and conversion, as well as interoperable storage access services [

20].

However, the practical implementation of data portability faces several challenges, particularly due to the lack of clear guidelines specifying which data should be included in portability requests. The absence of a well-defined regulatory framework introduces uncertainty for both users and service providers, hindering the development and adoption of effective solutions [

21].

2.2. Security by Design

Secure by Design (SBD) is a philosophy for developing secure software systems from the earliest stages of the development lifecycle [

9]. It emphasizes the integration of security considerations during the design phase to minimize vulnerabilities and reduce the need for rework in later stages [

22]. Its goal is to create inherently secure systems that are resilient to attacks by incorporating both technical and organizational aspects [

10]. This approach is embraced by companies such as Google, which highlights that security must be an integral part of software product design. Additionally, the design process should be user-centered, emphasizing that developers are also users [

23]. Therefore, this philosophy for developing secure software systems should also focus on the areas of cloud computing and Big Data to create safer products and apply them to domains such as data analysis.

In this context, [

11] presents a new SBD framework for deploying Big Data frameworks in cloud computing. Their proposed methodology facilitates the development and deployment of secure cloud applications by addressing risks from the design phase to mitigate vulnerabilities and threats. It promotes the adoption of secure IaaS models through an SBD approach, integrating the Apache Hadoop 3.0 ecosystem and advanced Big Data technologies, mapping security concerns into a model that optimizes the configuration of reliable BigCloud systems.

Similarly, [

6] proposes a comprehensive methodological approach to incorporating security and privacy into the development of Big Data ecosystems, grounded in existing standards and best practices. The proposal introduces a structured process consisting of 12 phases, addressing everything from requirements definition to risk implementation and management. The approach proposed by [

6] aligns with the SBD philosophy, integrating security measures from the earliest stages of development.

2.3. Infrastructure

Big Data infrastructure is emerging as a critical component for managing complex, large-scale information that exceeds the capabilities of conventional processing systems [

1]. Big Data applications require specialized cloud infrastructures to efficiently handle massive amounts of complex data. Researchers have proposed various approaches to optimize resource allocation in the cloud for Big Data [

24].

Big Data exhibits characteristics that make the tools and infrastructure required non-trivial, often represented by challenges known as the "V’s of Big Data." In [

2], the author identifies Volume, Variety, Velocity, Veracity, and Value as key characteristics. Additionally, the author highlights process-related challenges such as data acquisition and storage, preprocessing, data analysis and modeling, visualization, and ensuring security and privacy.

It is important to note that the infrastructure required to process large amounts of data is often provided by external cloud services. Companies commonly opt to contract third-party computational services rather than deploying their own resources.

Distributed computing is one of the most sought-after resources for handling large datasets, as it enables efficient data processing.

In [

25], the author discusses how cloud computing differs from traditional computing, emphasizing key aspects such as scalability, cost-effectiveness, accessibility, security, and flexibility. The study includes real-world use cases where organizations extract valuable insights from large datasets, highlighting the use of cloud computing in fields such as genomic informatics, Twitter, Nokia, and RedBus, illustrating the widespread adoption of Big Data infrastructure.

In [

8], the author reviews their proposed Databricks architecture, using a use case involving the processing of 1 TB of data every five days. Historical data is stored in a Delta Lake based on AWS S3 and processed with Spark. This study references concrete cloud tools such as Databricks, AWS S3, and Spark, providing insights into how cloud-based infrastructure solutions are implemented.

In [

26], the author presents the advantages and limitations of a cloud-based architecture to provide guidance for implementing a Data Lake architecture. The advantages include storage capacity, cost-effectiveness, auto-scaling, and data security, among others. The author highlights that data security is tied to the responsibility and guarantees offered by cloud providers. This security approach forms a foundation for ensuring privacy and protecting personal and sensitive data. However, once the data enters production, the risk of breaches increases.

2.4. Format Preserving Encryption

FPE is an encryption method designed to deterministically encrypt a plaintext

X into a ciphertext

Y , under the control of a symmetric key

K, while ensuring that

Y retains the same format as

X [

12]. This encryption technique is particularly useful for masking information while preserving its original format, offering data portability and the potential to store encrypted information in databases without altering their schema. Various researchers have contributed to this form of encryption. For instance, [

13] provides a framework for addressing limitations related to specific formats, and [

27] offers recommendations regarding block cipher modes of operation, with a focus on approved methods for FPE.

FPE has also found its place in cloud computing and Big Data environments, where vast amounts of personal and sensitive data are processed daily. Big Data tools play a critical role in handling this data, and FPE emerges as a vital technique for maintaining privacy and protecting sensitive information in these contexts.

In this regard, [

14] proposes an FPE-based scheme using Spark for data processing, presenting an example that could be applied in banking environments. However, the author does not delve into aspects such as data ingestion, storage architecture, or data governance.

Similarly, [

15] explores the use of FPE through the optimized FF1-SM4 algorithm. The proposed scheme utilizes FF1-SM4 for desensitizing sensitive character strings in relational databases, alongside Pallier encryption for numerical data to enable homomorphic computations. The author claims to ensure security by protecting sensitive data using either FF1-SM4 or Pallier in both private and public cloud environments.

In [

7], the author presents an FPE-based encryption scheme designed to safeguard sensitive database information while preserving the original format and length of the data. This approach leverages the AES algorithm combined with XOR operations and translation methods to ensure that the encrypted data maintains referential integrity and the format required by existing applications and queries.

Moreover, [

28] introduces a protocol called B-FPE for the secure sharing of medical records using blockchain. FPE ensures that encrypted data retains the same format as the original data (e.g., Social Security numbers or birth dates), enabling interoperability among healthcare service providers without compromising data security.

These examples highlight the growth of FPE and its practical use cases, demonstrating its potential as a powerful tool for protecting data. The reviewed elements provide a foundation for employing FPE in our proposed protocol.

2.5. Data Lake Architecture

Data Lake repositories are a widely used type of tool due to their advantages over other types of repositories, such as Data Warehouses. In [

5], the author defines a Data Lake as a low-cost repository capable of storing structured, unstructured, and semi-structured data. In [

4], the author adds that a Data Lake serves as a landing zone for raw data from various sources. This allows us to observe how data is managed in these environments and the complexities involved in handling it. In [

29], the author provides a definition of a Data Lake as a scalable system for storing and analyzing data of any type, preserved in its native format and primarily used by data specialists for knowledge extraction.

From these definitions, a clear pattern emerges: the data entering these repositories can have varying formats and structures. This is why the implementation of Data Lakes must involve Data Lake architectures, which provide a conceptual organization of how data is structured within a Data Lake [

30]. These architectures facilitate data capture, use, and reuse while avoiding redundant processing [

31].

The architectures can be divided into two types, referred to as Zones and Ponds [

30]. Additionally, [

29] proposes a functional and maturity-based architecture aimed at addressing the contradictions of Zone and Pond architectures.

For this work, we will focus on the Zone-based architecture, which allows data to be divided into refinement zones. One of its advantages is the ability to access raw data in the raw zone, even when transformed or preprocessed data is available [

30].

2.6. Data Ingestion

Data ingestion helps transfer data from a source to a Data Lake [

29]. According to [

32], ingestion is characterized by three types: Batch, Streaming, and Orchestrated.

Batch ingestion refers to the transfer of data from its origin to its destination at a defined periodicity, typically in intervals of hours, days, or months [

32]. On the other hand, Streaming ingestion involves real-time data transfer, though achieving true real-time capabilities can be challenging. This ingestion type is characterized by a constant flow of data, aiming to ingest it as it is generated [

32].

In this context, [

33] focuses on Batch and Streaming ingestion, proposing a fusion of the two with Orchestrated ingestion, resulting in Batch-Orchestrated and Streaming-Orchestrated ingestion. The author also suggests a set of mandatory and optional characteristics for the ingestion process. Among the optional characteristics is data processing, which refers to scenarios where data must undergo critical manipulation, such as obfuscation of sensitive information.

This transformation-oriented approach to ingestion is also discussed in [

34], where the author proposes enriched ingestion with access controls. The proposal includes a taxonomy of transformations for confidentiality or integrity, utilizing encryption or hashing mechanisms and mentioning encryption techniques. Additionally, the author addresses data transformation through anonymization, highlighting that encrypted data becomes unusable for analysis.

2.7. Data governance

Data governance is a critical component of an organization’s information management strategies, essential for ensuring data quality and security [

35]. It encompasses the definition of policies, standards, and organizational structures to effectively manage data [

36]. Effective data governance is vital for managing data throughout its lifecycle, from capture to destruction, and is particularly important for organizations such as banks and public entities [

35,

37]. Data governance plays a crucial role in ensuring data security and privacy, especially in cloud computing environments. It involves implementing frameworks and policies to manage data access, ownership, and protection [

38,

39]. Organizations face the challenge of maintaining data privacy and security in the Big Data era, requiring robust governance strategies [

39,

40].

Various roles within data governance can be identified, each with specific responsibilities. In [

41], the author explores six roles in data governance, with particular emphasis on Data Owners and Data Stewards.

Data Owners are responsible for managing datasets, facilitating access, and ensuring proper data usage. This role involves creating governance policies and being accountable for ensuring that their data complies with governance standards [

41].

On the other hand, Data Stewards represent business processes and act as custodians of the data, focusing on its maintenance. They possess domain-specific knowledge and are responsible for ensuring data adherence to governance policies and procedures [

41].

In [

42], the author introduces additional roles, some focused on security, such as the Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) and Data Security Officer. However, these roles are less commonly found in organizations.

3. Methodology

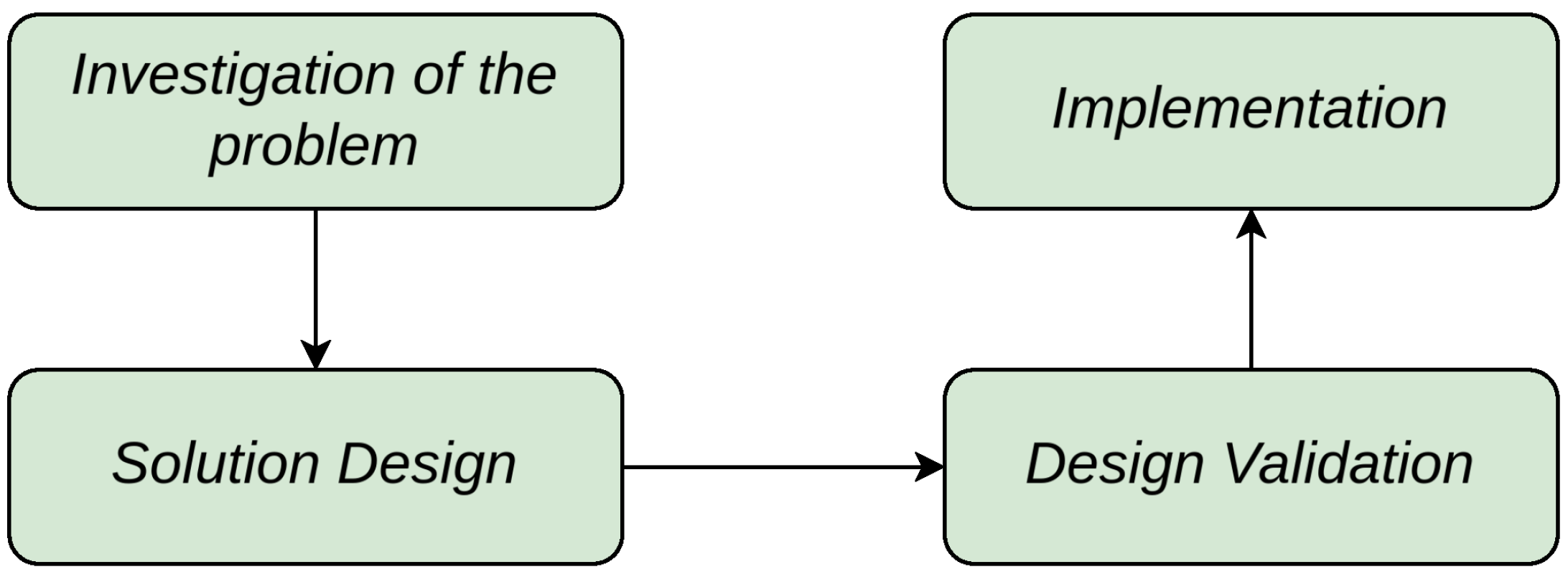

3.1. Design Science

The methodology used for this work is Design Science, as described by [

16], which is applied to research in information systems and software engineering. The author proposes the use of workflows known as the "regulative cycle," structured into four subtasks shown in

Figure 1.

The definition of the four components of the regulative cycle is divided into two major areas: the understanding of the state of the art, which refers to the investigation of the problem, and the proposal of the protocol through its design, validation, and implementation.

3.1.1. Conceptual Analysis

In the initial phase of this research, a systematic mapping of the literature was conducted to gather information on encryption techniques applied to Big Data tools and Data Lake repositories for the protection of personal and sensitive data. This mapping is presented in

Section 3.2. To achieve this, the systematic mapping methodology proposed by Petersen [

43] was employed, providing a structured approach to organizing the activities necessary for the development of the systematic mapping.

The primary objective of this systematic mapping is to identify and classify the various encryption techniques utilized in Big Data tools and Data Lake repositories. This phase aims to address the critical need for safeguarding personal and sensitive information by offering a comprehensive overview of existing methods, as well as the requirements for their practical implementation.

3.1.2. Solution Design

To develop the proposed protocol, we conducted a systematic literature review to identify foundational elements and requirements, synthesizing these insights within a secure-by-design framework to create an initial version [

23,

44].

This version was refined through two Delphi-based expert consultation rounds [

45], ensuring theoretical robustness and practical applicability, particularly for regulated environments like banking.

The protocol’s design builds on findings from the systematic mapping (

Section 5.1), incorporating key elements into its architecture. It leverages the Software Reference Architecture (SRA) for semantic-aware Big Data systems [

46] as a foundational reference.

3.1.3. Design Validation

Once the solution design stage is over, the protocol validation stage begins, based on a variation of usability and quality surveys originally proposed in [

46,

47] and later adapted by [

33,

48], applied to experts in the Big Data area in banking environments, in order to ensure that key indicators are obtained according to the qualitative scale of [

49].

The first part of the survey focuses on the profile of participants. The key questions in this section aim to obtain dimensions of the expert’s experience expressed in time, as well as their role in the teams and tasks performed during their professional practice. The questions can be reviewed in the

Table 1.

For the Usability criterion, the survey worked on the basis of [

47], a form of 10 numbered expressions, answered on a Likert scale with values shown to the respondent between 1 and 5, related to the concepts of "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree", respectively. For odd-numbered questions (SQ2.1, SQ2.3, SQ2.5, SQ2.7, SQ2.9), high values are expected; for even-numbered questions (SQ2.2, SQ2.4, SQ2.6, SQ2.8, SQ2.10), low values are desirable. The questions for this section are detailed in

Table 2.

The usability score has values between 0 and 100 and is calculated through the following:

where

For the Quality criterion, the survey worked on the basis of [

46], building a form of 7 numbered expressions, answered on a Likert scale with values shown to the respondent between 1 and 5, related to the concepts of "Strongly Disagree" to "Strongly Agree". The expressions are aligned to the quality sub-characteristics as shown in

Table 3.

In this section, the highest possible value for each question is desirable, so the Quality value is calculated using the following equation which normalises the result obtained between 0 and 100:

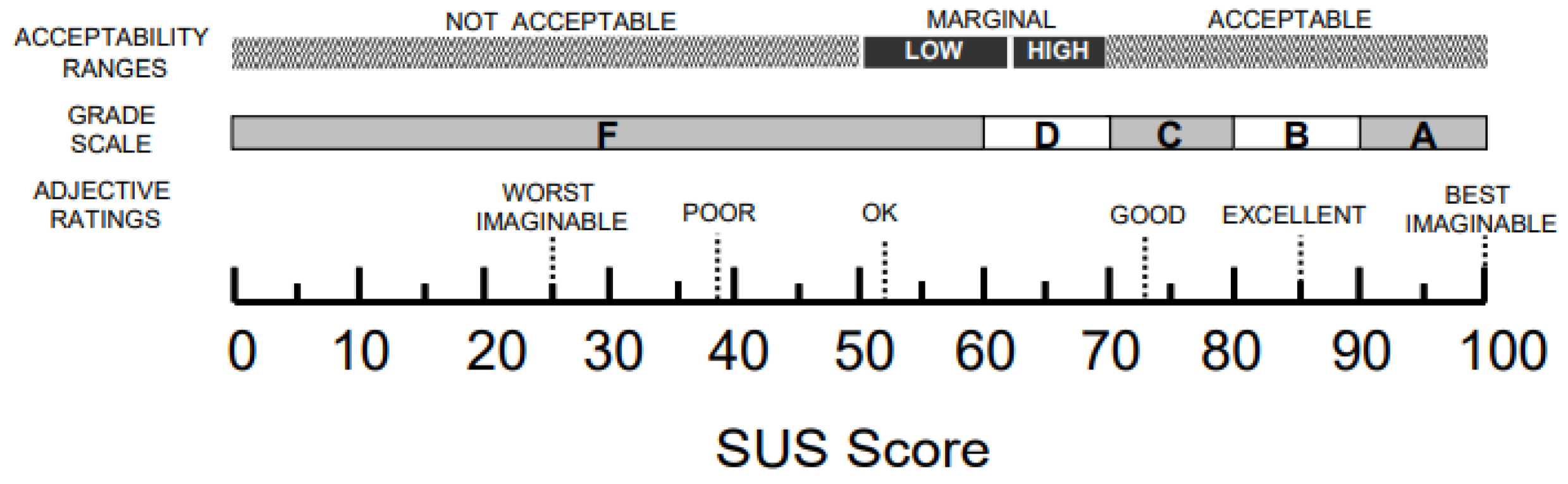

Finally, to analyze the scores resulting from Usability and Quality, they will be analyzed under the Bangor Qualitative Scale [

49], which allows a perspective associated with adjectives over the numerical value as is shown in

Figure 2. The use of this scale will give us a perspective of the degree of "approval" that the proposal has in the 2 criteria previously exposed, having the desirable minimum acceptability of "marginally high" and an ideal of "acceptable".

3.1.4. Implementation

The final stage of the workflow described in

Section 3.1 was implemented through the development of a guide that documents the procedure for applying the proposed protocol. This guide integrates the feedback gathered during the design validation phase, enabling the refinement of the proposed procedures. As a result, the documented guidelines are ensured to be both applicable and effective, aligning with the requirements and expectations identified in the earlier stages of the workflow.

3.2. Systematic Mapping of the Literature

3.2.1. Research Questions

The proposed research questions position us in the search and exploration of methodological and technical contributions in the literature, as well as in identifying challenges and gaps in the implementation of encryption.

3.2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All documents resulting from the search strings applied in the search engines were subjected to systematic inclusion and exclusion criteria, allowing for a quick filtering process.

Inclusion Criteria:

- (i)

Language: Only studies published in English and Spanish are included, ensuring that the documents are accessible and relevant to the international academic literature.

- (ii)

Publication Date: Only works published between 2014 and January 2024 are considered to include all relevant documents in the field of data protection in Big Data and Data Lakes environments.

- (iii)

Sources: Only works from scientific journals and conferences are accepted.

Exclusion Criteria:

- (i)

Study Domain: All works not focused on the field of information security in Big Data environments and Data Lake repositories are excluded, ensuring that the research is exclusively focused on the topic of interest.

- (ii)

Accessibility: Documents that could not be fully accessed or were not relevant to the analysis were excluded.

- (iii)

Duplication: Duplicate documents between academic search engines were excluded, retaining only one and discarding the others.

This filtering process ensures that the included studies are relevant, up-to-date, and come from reliable sources, facilitating the review of encryption techniques in the context of personal and sensitive data protection in Big Data and Data Lakes environments.

3.2.3. Search and Selection Process

The search string used consists of key terms within the domain, applied in IEEE Xplore, Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and ACM Library. The use of these search engines is based on their broad coverage, quality, and focus on scientific articles.

The key terms used were “data lake” and (“privacy” OR “encryption”). By applying the corresponding Boolean expressions in each search engine, the search string is structured as follows: (“data lake” AND (“privacy" OR "encryption”)). Including these terms allows us to focus on Data Lake repositories and, by extension, Big Data technologies, while the terms “privacy” and “encryption” enable the identification of works specifically discussing data privacy preservation and encryption within this domain.

Based on these search strings, inclusion criteria that could be automated by the search engines were applied, filtering directly by language, publication date, and sources whenever possible.

The preliminary search results are reflected in

Table 5, where applying the aforementioned search string yielded 26 documents from IEEE Xplore, 10 documents from WoS, 533 documents from Scopus, and 161 documents from ACM Library.

The document selection process consists of three stages. In the first stage, non-automated inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria are applied as an initial filter to the obtained results, reviewing the title, abstract, introduction, and conclusions. In the second stage, the documents addressing topics related to information security and cryptography in Big Data and/or Data Lakes are validated and identified. In the third stage, documents specifically discussing encryption applied to personal and sensitive data are filtered. This process results in the following list of relevant articles for the study: [

34,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58].

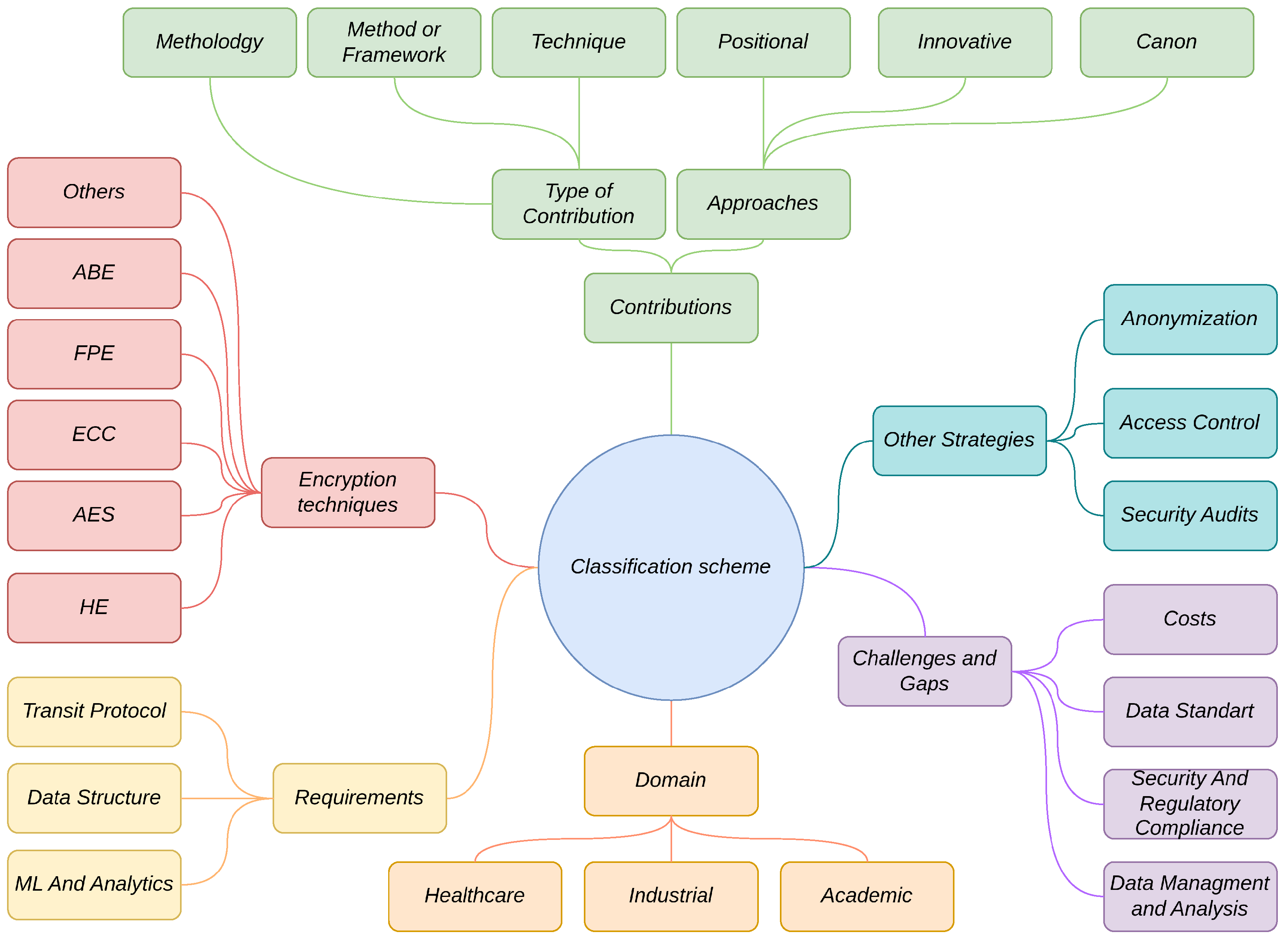

3.2.4. Classification Scheme

In this study, six classification schemes were applied to the selected studies:

Type of Contribution and Approach: The analyzed documents are classified according to the type of contribution and approach adopted. Regarding the contribution, three main categories are identified: (1) Methodology, which encompasses systematic techniques and tools to address problems; (2) Method or framework, which provides consistent structures or principles to solve specific problems; and (3) Technique, which includes specific improvements such as algorithms or specific implementations. Regarding the approaches, the documents can adopt one of the following: (1) Innovative, introducing significant advancements with new ideas, methods, or technologies; (2) Positional, analyzing phenomena from a particular viewpoint in relation to the context and existing practices; or (3) Canon, based on established practices, established methods, or accepted standards in the field. Each document may contribute more than one contribution but only one type of approach.

Encryption Techniques: In the context of Big Data and Data Lake repositories, the encryption techniques used to protect personal and sensitive data include Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), recognized for its effectiveness and performance; Homomorphic Encryption (HE), which allows operations on encrypted data without the need to decrypt it; Format-Preserving Encryption (FPE), which maintains the original format of the data, facilitating its integration with existing systems; Elliptic-Curve Cryptography (ECC), which stands out for offering a level of security comparable to other traditional cryptographic techniques but with smaller keys, reducing storage and processing requirements, ideal for resource-limited environments; and Attribute-Based Encryption (ABE), which ensures fine-grained encrypted access control to externalized data. Other emerging techniques are also identified, expanding the available options according to the specific requirements presented by the documents.

Format Requirements: Format requirements for data are classified according to their state. For data in use, the requirements focus on the needs for analysis and machine learning, ensuring that the data can be processed efficiently without fully decrypting it. For data at rest, the requirements focus on the data’s structure, ensuring its correct integration and storage while maintaining its integrity. Finally, for data in transit, the requirements are grouped according to the communication protocols and technologies employed, ensuring secure transmission of data across networks or between systems.

Other Protection Strategies: Refers to other ways of protecting data in the context of the research. This includes anonymization, which involves modifying the original data to hide sensitive information and prevent the identification of individuals or entities; access control, which encompasses policies and mechanisms that determine who can access the data and under what conditions, ensuring that only authorized individuals have access to the information; and security audits, which involve the continuous monitoring and review of activities related to data access and usage, with the goal of identifying vulnerabilities and ensuring compliance with security policies.

Domain of the Document’s Development: The application domain of the document can be classified into three areas: Industrial, Healthcare, and Academic. The Industrial domain refers to documents where the research focus is developed in the context of an organization or industrial sector. The Healthcare domain refers to research focused on medical data or data protection within the healthcare field. Finally, the Academic domain encompasses documents aimed at presenting general research without a specific focus on the industry or healthcare sector.

Challenges and Gaps: The challenges and gaps identified in the reviewed documents can be classified into four key areas: Costs, which limit the adoption of advanced technologies; Data Standards, necessary to ensure interoperability and facilitate information exchange between systems; Security and Regulatory Compliance, which are essential for protecting sensitive data and complying with regulations such as Chilean law N. 19.628; and Data Management and Analysis, which refers to the challenges associated with efficiently managing and processing large volumes of data in Big Data and Data Lakes contexts. This scheme highlights the most relevant areas for future research and the development of technological solutions.

4. Proposal

Based on the analysis of the

Section 2, this work presents a protocol designed to ensure data portability in Data Lakes while incorporating the principles of Secure by Design. The main objective is to safeguard the protection of personally identifiable data and ensure proper control over its usage. This proposal positions security as a fundamental pillar in Big Data applications operating on Data Lakes. The protocol is structured into multiple layers, corresponding to the different stages of Big Data processes, following the model proposed by [

46] and illustrated in

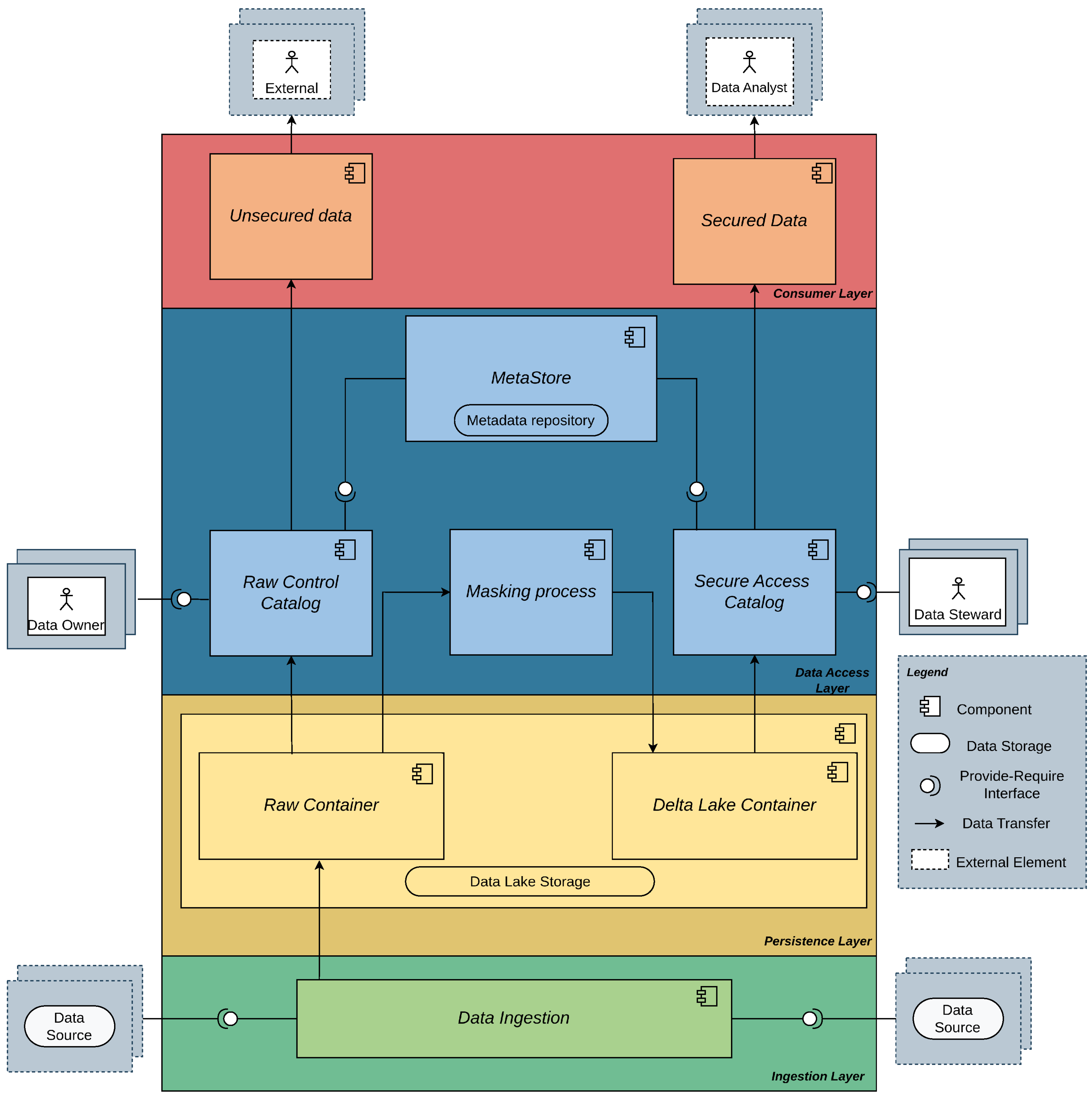

Figure 5.

The protocol design encompasses the data ingestion stage, where data is collected from various sources and formats and initially stored in a Data Lake in its raw format. From this stage, the protocol enables two possible paths:

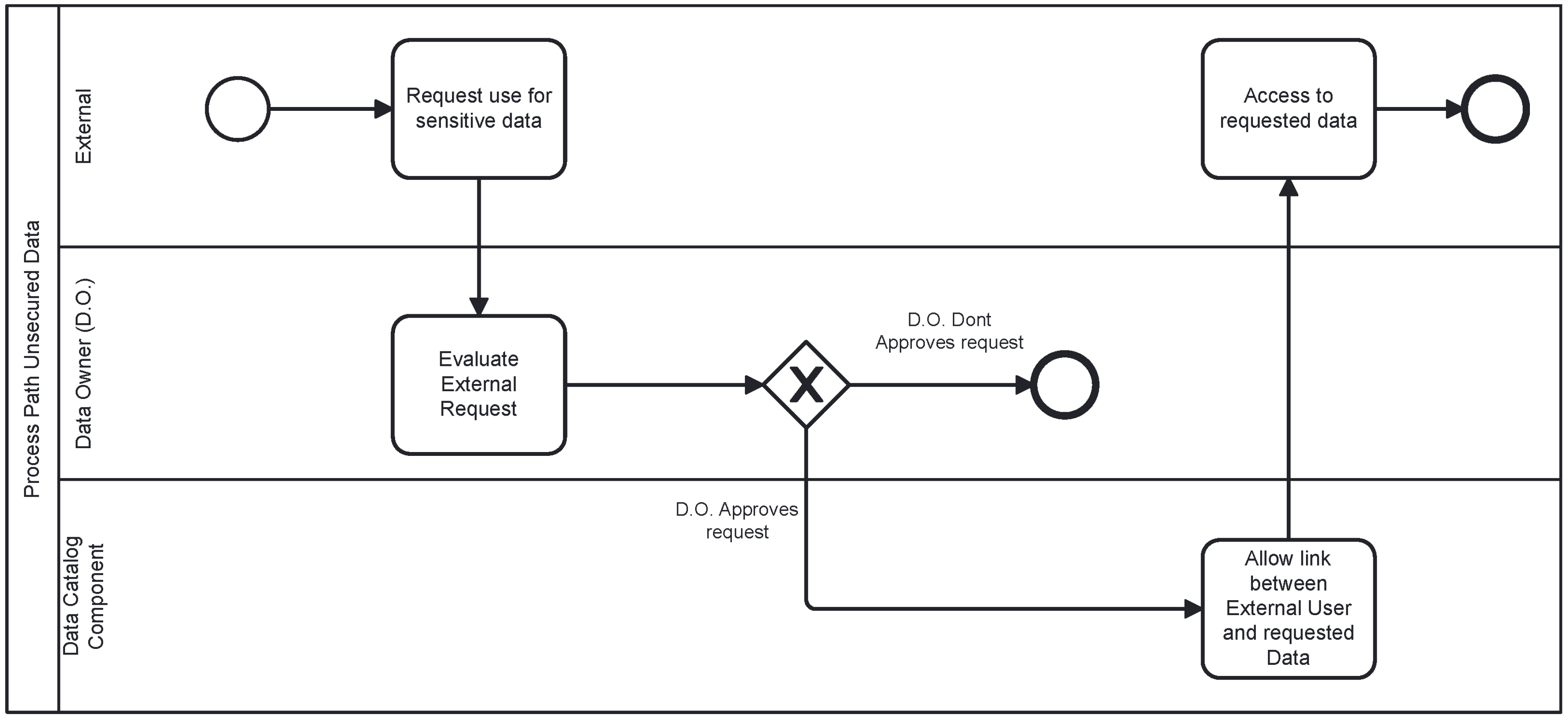

Unsecured Path: Represented in

Figure 3, this path involves accessing the data without encryption measures, reserved exclusively for extraordinary cases, such as requests from entities with superior authority, for example, for judicial, law enforcement, or legal compliance purposes.

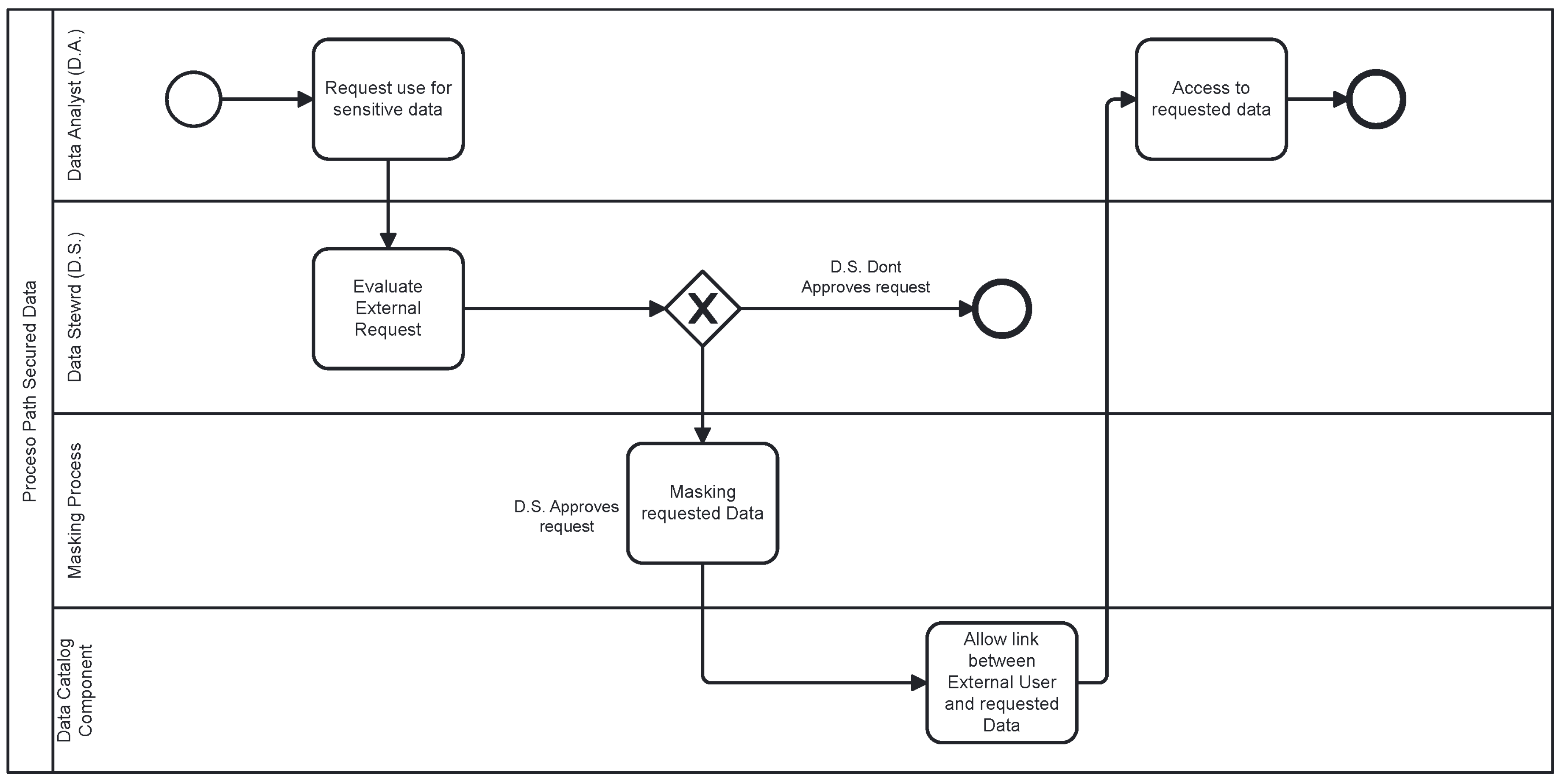

Secured Path: Represented in

Figure 4, in this path, the data undergoes an encryption scheme based on masking through FPE (Format Preserving Encryption) and is transformed into the Delta Lake format. This allows controlled and secure data consumption under the supervision of Data Stewards, who regulate access and ensure compliance with security policies.

However, it is important to note that the protocol cannot guarantee control over the use of data once it has been transferred to third parties. Therefore, the responsibility lies with the Data Owners, Data Stewards, and requesters, who must adhere to the principles and regulations established for the ethical and secure handling of information.

Figure 5.

Architectural representation of data flow and protocol components.

Figure 5.

Architectural representation of data flow and protocol components.

4.1. Ingestion Layer

The ingestion layer is responsible for loading or collecting data from external sources and ensuring its proper entry into the protocol. Once inside, this layer immediately transfers the data to the persistence layer, where the Data Lake storage is located. This ensures that the data does not remain in the ingestion layer longer than necessary.

Data Ingestion. This component is responsible for extracting data from external sources and transporting it to the Data Lake. Although this component can be considered an autonomous process, within the context of this protocol, no distinction is made between the types of ingestion (Batch or Stream), as both are treated equally.

4.2. Persistence Layer

This is the data landing layer, where data is stored and can only be accessed by the Data Owner, who has authority over the data and is responsible for its proper management. This layer is divided into two containers, which serve as a division between the Raw data, which is unencrypted, and the data in Delta Lake format, which is encrypted.

Raw Container. This container within the proposed Data Lake stores the information exactly as it arrives into the protocol and can only be accessed directly by the Data Owner.

Delta Lake Container. This container stores the data in encrypted Delta Lake format. Through this container, the Data Steward will grant access to users via the Secure Access Catalog component, allowing the data to be consumed.

4.3. Data Access Layer

This layer is responsible for access management and data masking using the tools provided by Databricks, as well as offering the necessary interfaces for integration with other components of the protocol. In this layer, the Data Steward defines which data will be securely sent to the consumption layer, thanks to the preprocessing of data masking. It also allows data to be transferred to the export layer in an unsecured manner, meaning without masking. The components of this layer are divided into services, tools, and workspaces provided by Databricks.

Raw Control Catalog. This component is responsible for accessing raw data without the security layer provided by the Masking Process component. These data can only be accessed by the Data Owner, who has full control and is responsible for managing the shared, unprotected data. The unsecured data is then transferred to the Consumption layer, where it is consumed by external parties that require the data in its raw form.

Secure Access Catalog. This component is responsible for accessing the data encrypted with FPE stored in the Delta Lake Container. These data are managed by the Data Steward, who has the authority to share the masked data with the Consumer Layer, where external parties to the protocol can freely use the data.

Masking Process. This component enables data masking using an FPE scheme. In Databricks, Spark is used as the collector, which serves as the primary tool for connecting to data sources [

33]. Above Spark is PySpark, a Python-based interface that facilitates interaction with Spark. With these tools, the masking scheme is developed on Spark using PySpark, ensuring optimal performance in data processing. The transformed data is then converted into Delta Lake format and can be stored in the Delta Lake Container, where it can later be accessed through the Secure Access Catalog.

4.4. Consumer Layer

The consumption layer is the final stage of the protocol, responsible for the output of the data. The components in this layer represent the data consumed in either Raw or Delta Lake format, as needed. The exported data is consumed by external actors to the protocol and can be classified into two categories:

Safe Data. These are the encrypted data exported in Delta Lake format for secure consumption, typically intended for analysis by external actors to the protocol. These data undergo the masking scheme and, with authorization from the Data Steward, are protected before being shared.

Unsafe Data. These are the data exported in various formats but extracted directly from the Data Lake without going through the masking scheme. As a result, they are shared in an unsecured manner and lack the necessary controls to ensure their protection.

5. Results

5.1. Systematic Mapping Results

5.1.1. Data Extraction and Mapping

The data extraction is crucial for organizing relevant information and answering the research questions. The results of this study are shown using bubble charts created with the tool [

59] and a bar graph.

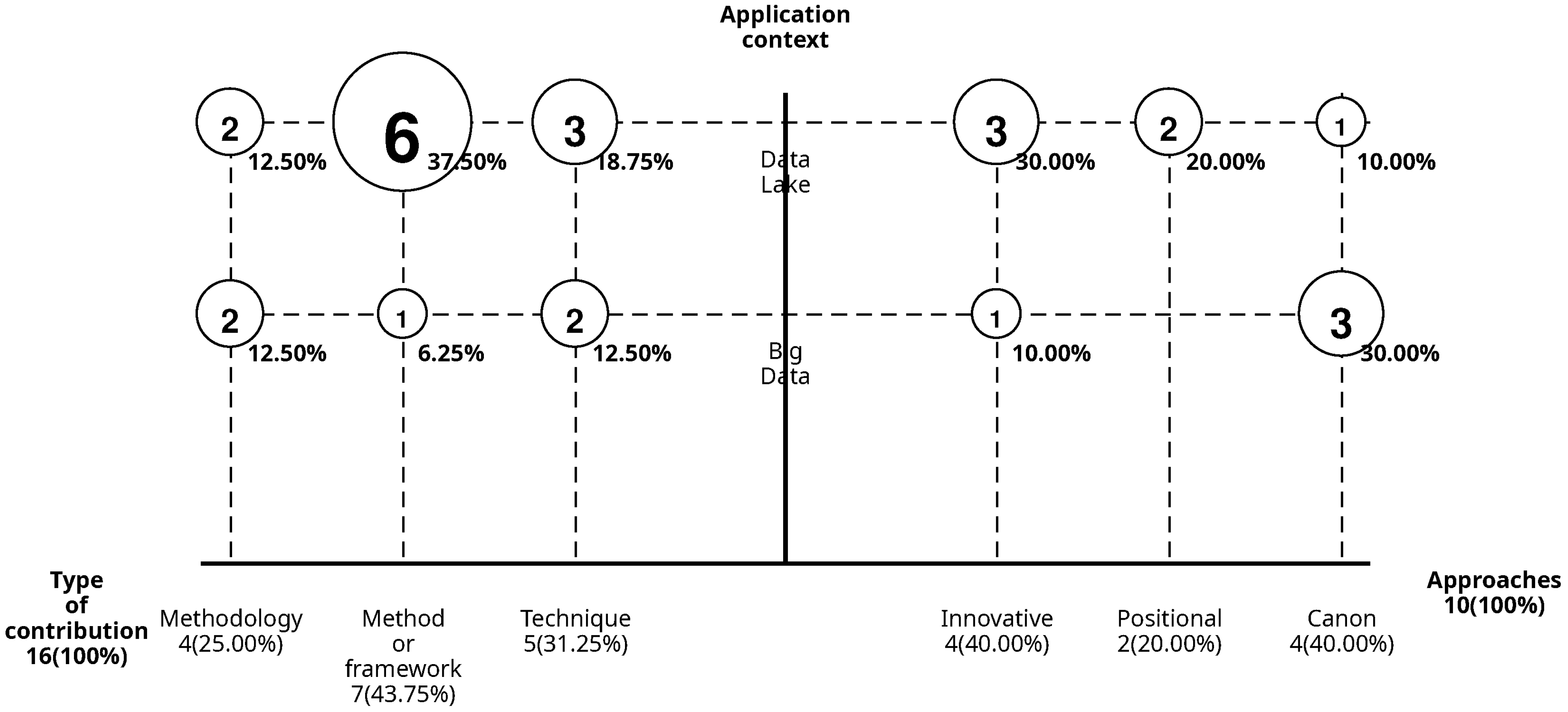

Figure 6 focuses on representing the results of the contributions and types of approaches found in the documents, providing a high-level view of the documents identified in the mapping and the trends observed.

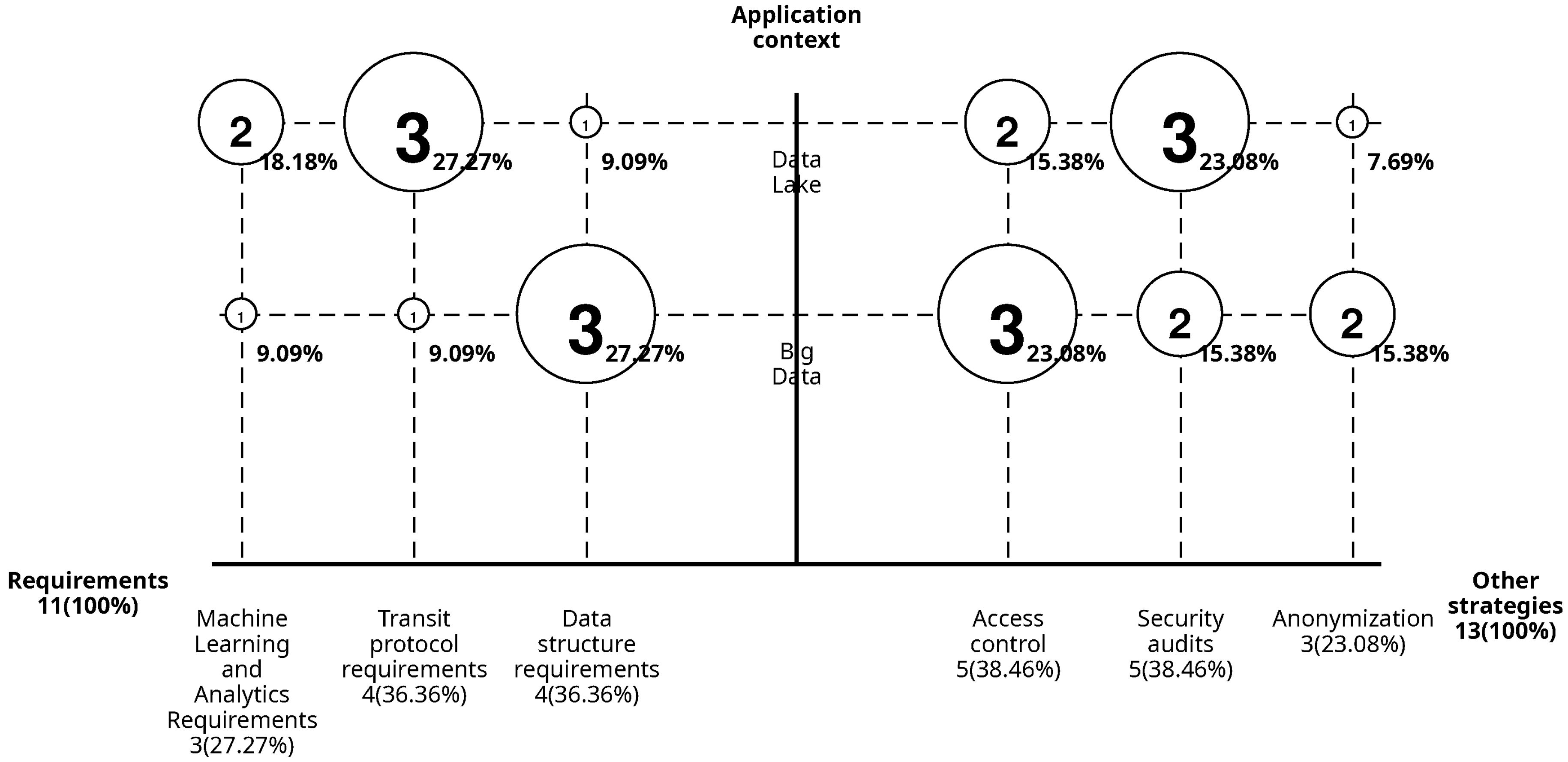

Figure 8 details the requirements found for data to undergo encryption at different stages and other strategies for data protection identified in the documents.

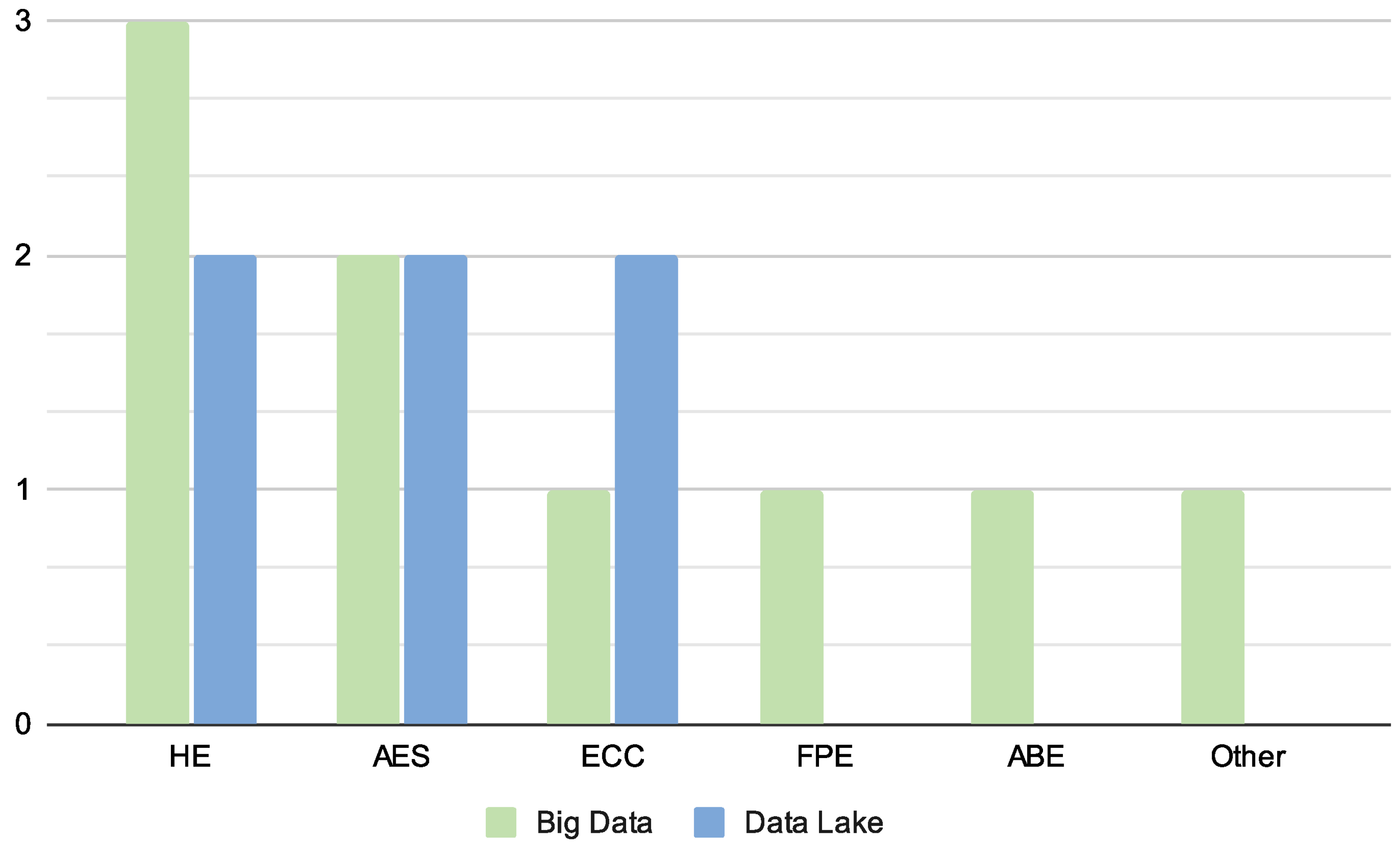

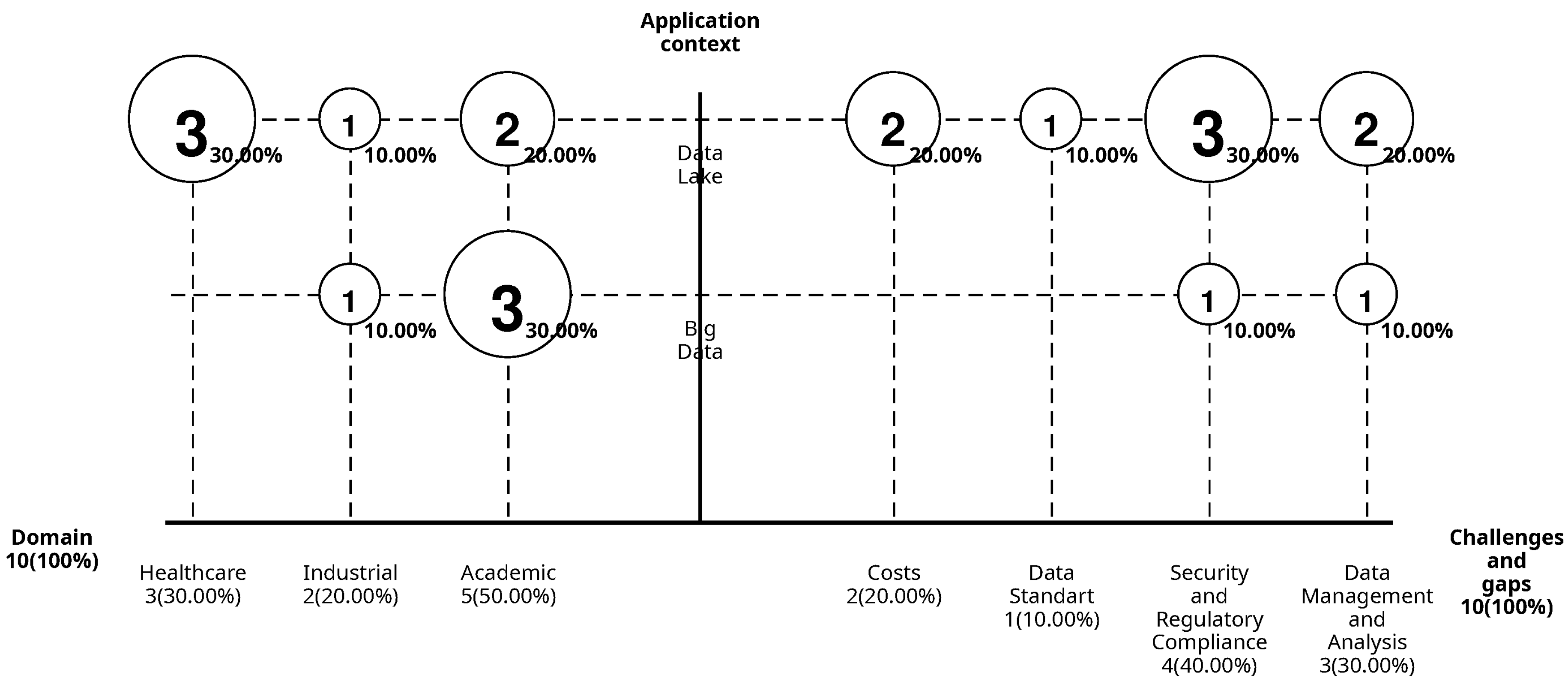

Figure 9 represents the domains of the documents found in the mapping and the challenges they present for future work in the area. The bar chart in

Figure 7 represents the encryption techniques found in Big Data and Data Lakes based on our exclusion criteria. The information presented in the bubble diagrams is divided into two axes: the positive and negative X-axis corresponds to the classification exposed in

Section 3.2.4, while the Y-axis represents the context in which it is applied (on Big Data or Data Lakes).

5.1.2. Analysis and Discussion

RQ1 What types of contributions are found in the selected documents?

Figure 6 shows that the most common type of contribution in the selected documents is Method or Framework, accounting for 43.75%, followed by Technique at 31.25%, and Methodology at 25%. Each document may contribute more than one type of contribution, but only one approach, with innovative approaches standing out at 40%. Of these, 30% are related to Data Lakes, and 40% are associated with Big Data. Finally, documents with a position approach represent 20% and are exclusively focused on Data Lakes.

The results reveal a tendency towards innovations in Data Lakes, while Big Data often involves the use of already established tools. With these tools, methods or frameworks are proposed over other types of contributions.

RQ2 What encryption techniques are used on Big Data tools for processing personal and sensitive data?

Figure 7 shows the encryption techniques used in Big Data tools to protect personal and sensitive data. According to our classification scheme, the most common techniques are HE (Homomorphic Encryption) and AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), due to their ability to perform operations on encrypted data and their high performance, respectively. Techniques like ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography), FPE (Format Preserving Encryption), and ABE (Attribute-Based Encryption) each appear once. Within the “Other” group, Proxy Re-encryption stands out, which is a technique based on the heterogeneous re-encoding of encrypted text, useful for scenarios requiring delegated secure access in distributed environments.

The results indicate a need for encryption techniques that offer differentiating features from conventional ones like HE. While AES is more widely used than other forms of encryption such as FPE and ABE in this context, the latter techniques present promising security potential and contributions to the ecosystem. Their appeal lies in features such as format preservation and access.

RQ3 What encryption techniques are applied to data in Data Lake repositories?

Figure 7 presents the encryption techniques identified in Data Lakes, highlighting that HE (Homomorphic Encryption), AES (Advanced Encryption Standard), and ECC (Elliptic Curve Cryptography) are the most commonly used, each appearing twice. These techniques stand out for their ability to handle large volumes of data securely: HE allows operations on encrypted data, AES is efficient and widely adopted, and ECC provides security with smaller keys, making it ideal for resource-constrained environments. On the other hand, techniques such as FPE (Format Preserving Encryption), ABE (Attribute-Based Encryption), and others were not mentioned in the reviewed documents.

RQ4 What data format requirements are necessary for encryption in use, at rest, or in transit?

Figure 8 highlights that the most frequent format requirements correspond to data structure, accounting for 36.36%. These are primarily observed in Big Data (27.27%), while their presence in Data Lakes is lower (9.09%). On the other hand, requirements related to transmission protocols and technologies also represent 36.36%, but these are more significant in Data Lakes (27.27%), with a smaller percentage in Big Data (9.09%). Finally, learning and analysis requirements make up 27.27% in total, with a greater incidence in Data Lakes (18.18%) than in Big Data (9.09%).

RQ5 What other strategies for protecting personal and sensitive data are found in the selected documents?

Figure 8 shows that additional strategies used to protect personal and sensitive data include access control and security audits, both representing a total of 38.46%, with differences in their distribution: access control is more common in Big Data (23.08%) than in Data Lakes (15.38%), while security audits are more prevalent in Data Lakes (23.08%) than in Big Data (15.38%). On the other hand, anonymization is the least common practice, with 15.38% in Big Data and only 7.69% in Data Lakes.

RQ6 What are the industry domains presented where personal and sensitive data protection is applied?

Figure 9 shows that the Academic domain is the most common, representing 30% of the documents in Big Data and 20% in Data Lakes, reflecting a predominant focus on general and theoretical research. The Health domain, present exclusively in Data Lakes with 30%, highlights its interest in protecting sensitive data related to medical information. Lastly, the Industrial domain accounts for 20% of the total, equally divided between Big Data and Data Lakes (10% each), focusing on practical applications for businesses, organizations, or related areas.

RQ7 What types of challenges and gaps are presented for future work in the reviewed documents?

Figure 9 identifies the most common challenges and gaps in the reviewed documents. The primary challenge is security, privacy, and regulatory compliance, present in 30% of studies related to Data Lakes and 10% in Big Data. This reflects the importance of ensuring the protection of sensitive data and adhering to specific regulations. Data management and analysis emerge as challenges in 20% of Data Lake documents and 10% in Big Data, emphasizing the technical difficulties related to data scalability and complexity. Other challenges, such as costs (20%) and data immutability and standards (10%), are unique to Data Lakes environments. These findings underscore the need for ongoing research to address these challenges in both Data Lakes and Big Data contexts, with a particular focus on enhancing data security, managing large-scale datasets, and ensuring compliance with regulatory requirements.

5.2. Survey Results

To assess the usability and quality of the proposed protocol, the validation process described in

Section 3.1.3 was carried out. This section presents the results of the survey through which the proposal was evaluated.

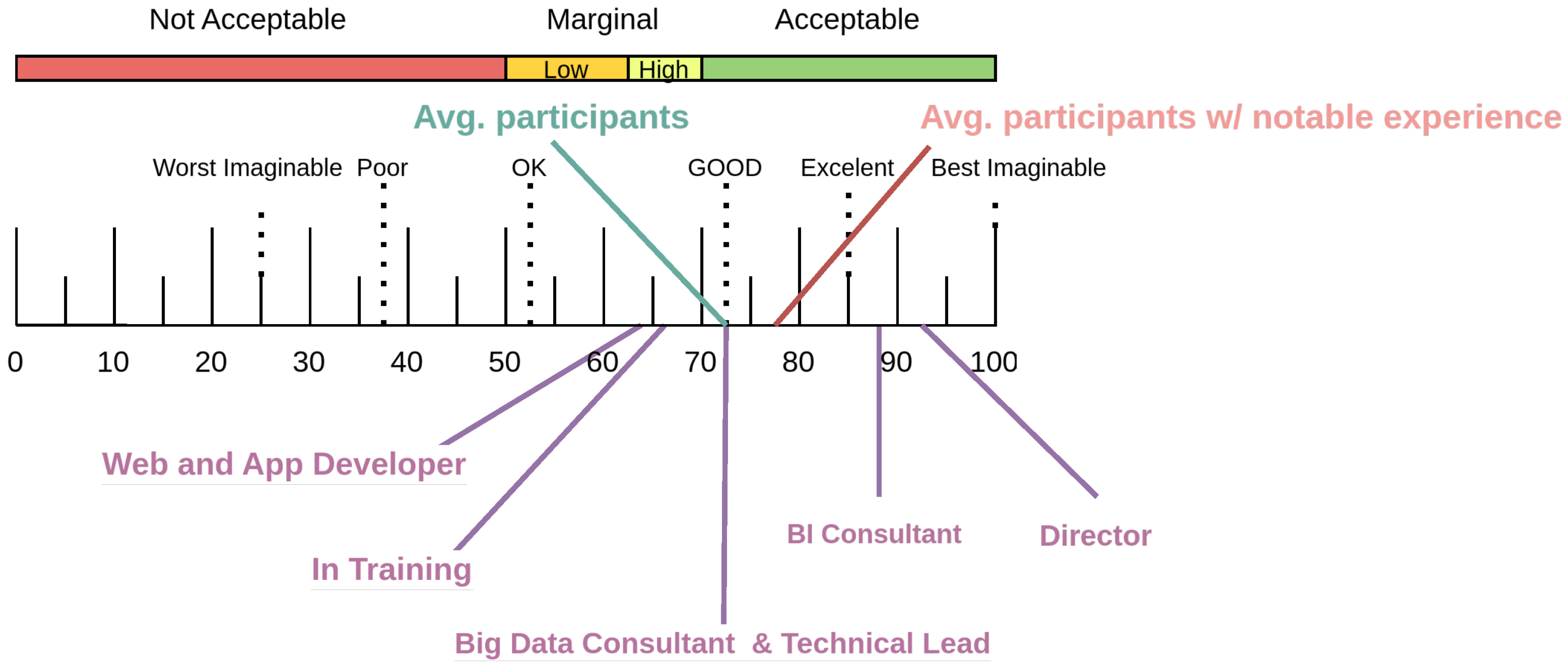

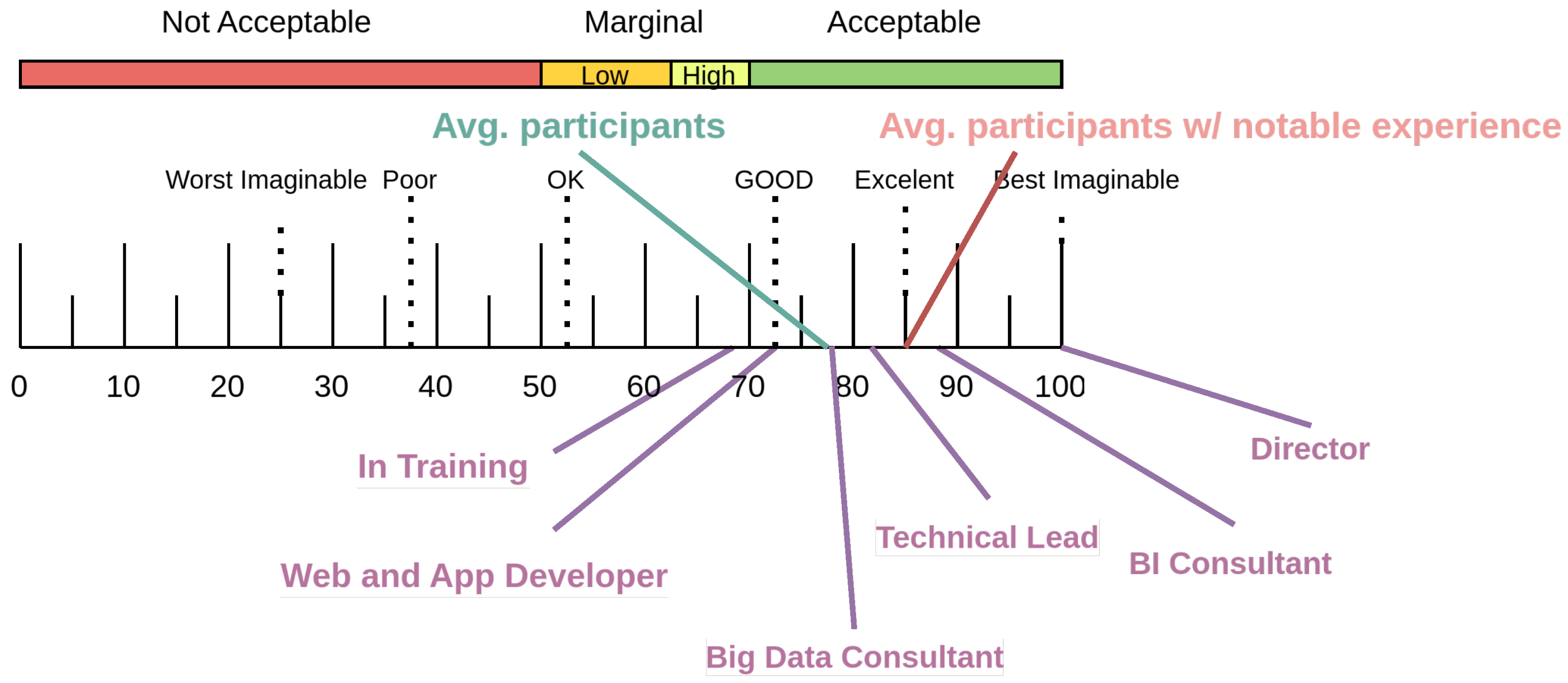

The results of the usability and quality questions are presented in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, where the roles within the company are represented in purple, the overall average of all individuals in green, and the average of individuals with notable experience in red.

5.2.1. Participant Profile

Gathering the profile of respondents allows us to support and evaluate our proposal based on their professional experience. The results are presented in

Table 6, highlighting the number of individuals by role and their average years of experience in IT, Big Data, and Data Lakes. Within this group of respondents, a subgroup of 10 individuals with more than five years of experience in the field was identified, providing perspectives based on a broader professional trajectory and enabling a more detailed analysis of the collected data.

5.2.2. Usability Assessment by Role

The usability evaluation yielded generally favorable results, with the overall average score exceeding 70 on a 0–100 scale. These values are presented in

Figure 10, which shows that the mean score across participants is above the commonly accepted usability threshold.

When disaggregating the data by professional role, two distinct clusters emerge. The first cluster includes Web and Application Developers (mean = 64.17) and participants currently undergoing training (mean = 66.25), both of which rated the protocol within the marginally acceptable range (classified as “Ok”). The second cluster comprises roles that assessed usability more positively: Big Data Consultants (mean = 73.96) and Technical Leads (mean = 72.50) placed usability in the “Good” category. Notably, Business Intelligence Consultants (mean = 88.75) and the Director (mean = 92.50) rated the usability as “Excellent.”

Taken together, these results yield a global average usability score of 72.23, situating the protocol within the “Good” category. Furthermore, participants with extensive professional experience exhibited a notably higher average score of 77.25, approaching the upper boundary of the “Good” range and suggesting a positive correlation between experience and perceived usability.

5.2.3. Quality Assessment by Role

The results of the quality-related assessment indicate even more favorable outcomes compared to the usability evaluation, with the overall mean score approaching 80. These values are depicted in

Figure 11, where a noticeable improvement is evident when analyzing responses across different organizational roles.

The only role with a mean score below the 70-point threshold was that of participants currently in training (mean = 66.96). In contrast, all other roles reported scores above this threshold. Web and Application Developers achieved a mean score of 72.62, while Big Data Consultants reported a higher mean of 78.57, nearing the upper boundary of the “Good” category.

Notably, all remaining roles surpassed the 80-point mark: Technical Leads (mean = 82.14), Business Intelligence Consultants (mean = 87.50), and the Director, who assigned the maximum score on the scale.

Overall, the mean score for quality assessment was 77.81, representing a marked increase relative to the usability results. Furthermore, individuals with considerable professional experience reported an average score of 85, thereby positioning their perception of quality within the “Excellent” category.

5.2.4. Analysis of Outlier Responses in Usability Evaluation

Among the collected data, two items deviated notably from the overall positive trend observed in the usability evaluation. These items correspond to Questions 2.4 and 2.10 in

Table 2, titled “I think I would need the support of a technician to be able to use this protocol” and “I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get started with this protocol,” respectively.

As illustrated in

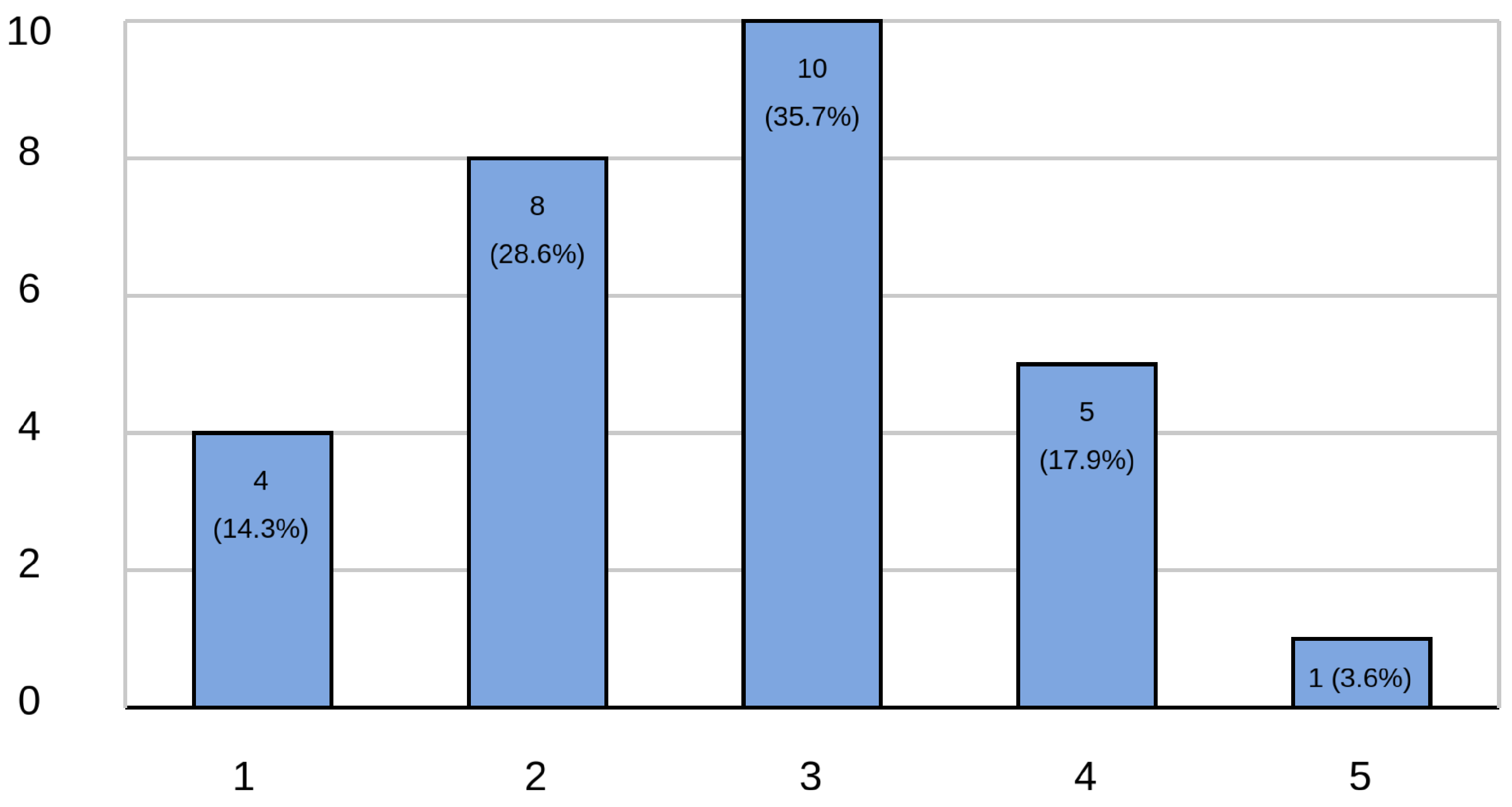

Figure 12, responses to Question 2.4 revealed that 21.5% of participants perceived a degree of complexity in the protocol’s implementation. Specifically, 17.9% selected value 4 and 3.6% selected value 5 on the Likert scale, indicating agreement with the need for technical support. The largest proportion of responses clustered around the neutral midpoint (value 3), accounting for 35.5% of participants. Meanwhile, 42.9% of responses aligned with the expected trend, suggesting ease of use—distributed between value 1 (14.3%) and value 2 (28.6%).

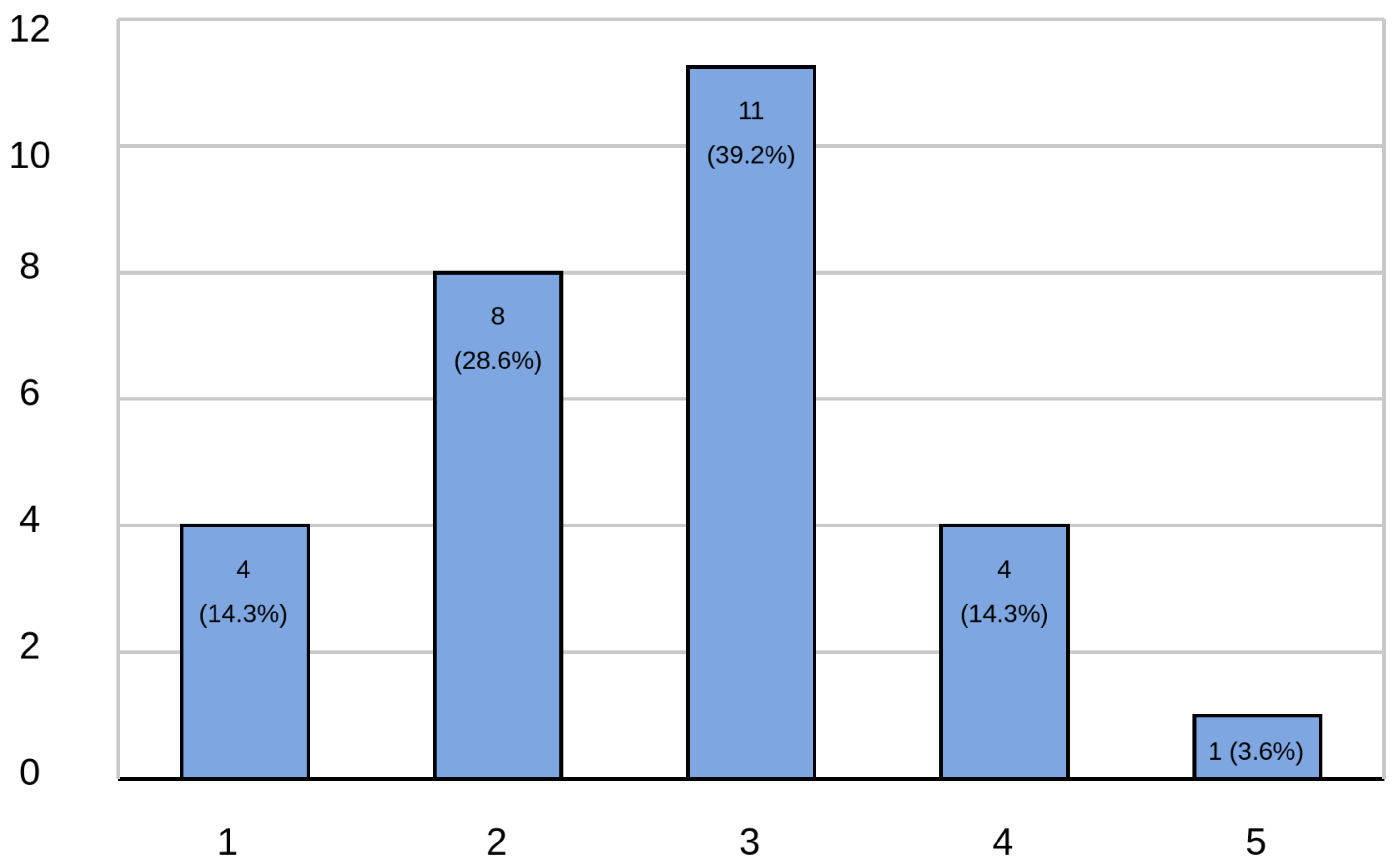

Similarly, results for Question 2.10, shown in

Figure 13, revealed that 17.9% of respondents indicated a need for prior learning to effectively use the protocol (value 4: 14.3%; value 5: 3.6%). Additionally, 39.2% of responses were neutral (value 3), highlighting a possible uncertainty or variability in users’ prior knowledge. However, the majority of participants (42.9%) disagreed with the statement, suggesting minimal learning was required. These responses were split between value 1 (13.8%) and value 2 (28.6%).

These results suggest that while the overall usability of the protocol was rated positively, a subset of users perceived potential barriers to initial adoption, particularly regarding the need for technical assistance or prior learning.

6. Discussion

The results obtained from the usability and quality questions indicate positive evaluations according to the scale proposed by [

49]. Considering that scores above 70 are regarded as “good,” most roles within the organization achieved values within or above this threshold. The two roles that showed comparatively lower scores were those labeled In Training and Web and Application Developer. This trend may be attributed to a lack of experience in the Big Data domain, as these participants—according to the profiling table (

Table 6)—reported the least experience in both general IT and in areas specifically related to Big Data and Data Lakes.

The overall average score closely aligns with the responses provided by Big Data Consultants. This is particularly relevant, as these professionals are expected to be the primary users of the protocol in real-world scenarios. Their positive evaluation suggests a strong consistency between general perceptions and those of the domain experts.

Additionally, participants with substantial experience—those with the highest number of years working in the field—reported the highest scores on usability and quality questions. This finding supports the notion that the proposed protocol is well received even by individuals with advanced knowledge and expertise in the area.

In summary, the usability and quality results suggest that the protocol is well suited for implementation in the banking context. No responses fell within the “not acceptable” range as defined by Bangor et al. [42], and the majority were situated within the “acceptable” or higher categories. These findings indicate that the protocol meets, and in many cases exceeds, the minimum expected standards for usability and quality in this sector.

6.1. Analysis of Outlier Responses Regarding Protocol Usability

From a general perspective, the data show acceptable values; however, it is crucial to analyze the two questions that yielded responses deviating from the expected trend.

Based on the responses to question 2.4, as shown in

Figure 12, there is a high concentration of responses at value 3, which may be interpreted as a neutral stance. Additionally, a considerable number of participants indicated that they would require technical support to implement the protocol. Although this figure is lower than that of participants who believed they would not need assistance, the high proportion of neutral responses suggests uncertainty about the challenges of applying the protocol in a professional setting.

This combination of neutral and affirmative responses regarding the need for technical assistance may be due to a lack of familiarity with configuring data catalogs, as well as the inherent complexity involved in implementing a Format Preserving Encryption scheme.

On the other hand, this result may also be influenced by the diversity of roles among the survey participants. While the survey included Big Data consultants, who are expected to have greater knowledge on the topic, it also involved individuals in roles that may not be familiar with the tools required to use the protocol.

A similar analysis can be conducted for the responses to question 2.10, shown in

Figure 13. Once again, there is a high concentration of responses at value 3, suggesting a neutral stance. However, there is also a significant number of affirmative responses indicating a need to acquire new knowledge prior to implementing the protocol.

As with question 2.4, the high proportion of neutral responses may reflect uncertainty in understanding the components of the protocol. This is further supported by the affirmative responses indicating that participants feel the need to learn various concepts before implementation.

This phenomenon may be partially explained by the profile of the respondents, as several were still in training and came from web application development backgrounds. However, the abundance of neutral responses also suggests that the protocol may be perceived as moderately complex from a theoretical standpoint.

Its comprehension may require familiarity with component diagrams and their layers, as well as more technical aspects such as the structure of a data catalog with designated stakeholders, or the concept of Format Preserving Encryption, which may be unfamiliar to individuals outside the field of cryptography.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.L., G.A., and J.F.L.; validation, J.L., G.A.; writing—original draft preparation, G.A., A.B.M. and M.B.L; writing—review and editing, J.L., G.A., J.F.L., A.B.M. and M.B.L; supervision, J.L. and J.F.L., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded (partially) by Dirección de Investigación, Universidad de La Frontera, Grant PP24-0027, and Research Grant DIUFRO DI25-0084.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABE |

Attribute-Based Encryption |

| AES |

Advanced Encryption Standard |

| BD |

Big Data |

| BI |

Business Intelligence |

| CISO |

Chief Information Security Officer |

| DL |

Data Lake |

| ECC |

Elliptic-Curve Cryptography |

| FPE |

Format-Preserving Encryption |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| HE |

Homomorphic Encryption |

| IaaS |

Infrastructure as a Service |

| IT |

Information Technology |

| SBD |

Secure by Design |

| SRA |

Software Reference Architecture |

| SUS |

System Usability Scale |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Mental map. Visualization of the classification scheme for systematic mapping.

Figure A1.

Mental map. Visualization of the classification scheme for systematic mapping.

References

- Chen, J.; Wang, H. Guest Editorial: Big Data Infrastructure I. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2018, 4, 148–149. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, R.; Yadav, R. Big data: Big data analysis, issues and challenges and technologies. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, 2021, Vol. 1022, p. 012014.

- Lagos, J.; San Martin, D.; Aillapán, G. BDS-Analytics: Towards a PySpark Library for a Preliminary Exploratory Big Data Analysis. In Proceedings of the Developments and Advances in Defense and Security; Rocha, Á.; Vaseashta, A., Eds., Singapore, 2025; pp. 369–379.

- Panwar, A.; Bhatnagar, V. Data lake architecture: a new repository for data engineer. International Journal of Organizational and Collective Intelligence (IJOCI) 2020, 10, 63–75.

- Guamán, M.A.; Vaca, M.N.; Salazar, K.V.; Yuquilema, J.B. Systematic mapping of literature of a data lake. mktDESCUBRE 2018, 1, 50–66.

- Moreno, J.; Fernandez, E.B.; Serrano, M.A.; Fernandez-Medina, E. Secure development of big data ecosystems. IEEE access 2019, 7, 96604–96619. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Jain, S.; Agarwal, M. Ensuring data security in databases using format preserving encryption. In Proceedings of the 2018 8th International Conference on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–5.

- Kumar, D.; Li, S. Separating storage and compute with the databricks lakehouse platform. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 9th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–2.

- Mouratidis, H.; Kang, M. Secure by Design: Developing Secure Software Systems from the Ground Up. Int. J. Secur. Softw. Eng. 2011, 2, 23–41.

- Shirtz, D.; Koberman, I.; Elyashar, A.; Puzis, R.; Elovici, Y. Enhancing Energy Sector Resilience: Integrating Security by Design Principles. ArXiv 2024, abs/2402.11543.

- Awaysheh, F.M.; Aladwan, M.N.; Alazab, M.; Alawadi, S.; Cabaleiro, J.C.; Pena, T.F. Security by design for big data frameworks over cloud computing. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 2021, 69, 3676–3693. [CrossRef]

- Bellare, M.; Ristenpart, T.; Rogaway, P.; Stegers, T. Format-preserving encryption. In Proceedings of the Selected Areas in Cryptography: 16th Annual International Workshop, SAC 2009, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, August 13-14, 2009, Revised Selected Papers 16. Springer, 2009, pp. 295–312.

- Weiss, M.; Rozenberg, B.; Barham, M. Practical solutions for format-preserving encryption. arXiv preprint arXiv:1506.04113 2015.

- Cui, B.; Zhang, B.; Wang, K. A data masking scheme for sensitive big data based on format-preserving encryption. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) and IEEE International Conference on Embedded and Ubiquitous Computing (EUC). IEEE, 2017, Vol. 1, pp. 518–524.

- Wu, M.; Huang, J. A Scheme of Relational Database Desensitization Based on Paillier and FPE. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Machine Learning, Big Data and Business Intelligence (MLBDBI). IEEE, 2021, pp. 374–378.

- Wieringa, R. Design science as nested problem solving. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th international conference on design science research in information systems and technology, 2009, pp. 1–12.

- Wieringa, R.J. Design science methodology for information systems and software engineering; Springer, 2014.

- Wohlfaxrth, M. Data Portability on the Internet: An Economic Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interaction Sciences, 2017.

- Wohlfarth, M. Data Portability on the Internet. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2019, 61, 551 – 574.

- Bozman, J.; Chen, G. Cloud computing: The need for portability and interoperability. IDC Executive Insights 2010, pp. 74–75.

- Huth, D.; Stojko, L.; Matthes, F. A Service Definition for Data Portability. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Enterprise Information Systems, 2019.

- Kadam, S.P.; Joshi, S.D. Secure by design approach to improve security of object oriented software. 2015 2nd International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom) 2015, pp. 24–30.

- Kern, C. Secure by Design at Google. Technical report, Google Security Engineering, 2024.

- Arostegi, M.; Torre-Bastida, A.I.; Bilbao, M.N.; Ser, J.D. A heuristic approach to the multicriteria design of IaaS cloud infrastructures for Big Data applications. Expert Systems 2018, 35.

- Megahed, M.E.; Badry, R.M.; Gaber, S.A. Survey on Big Data and Cloud Computing: Storage Challenges and Open Issues. In Proceedings of the 2023 4th International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Zagan, E.; Danubianu, M. Cloud DATA LAKE: The new trend of data storage. In Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications (HORA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–4.

- Dworkin, M. Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation. Methods and Techniques 2001.

- Konduru, S.S.; Saraswat, V. Privacy preserving records sharing using blockchain and format preserving encryption. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2023.

- Sawadogo, P.; Darmont, J. On data lake architectures and metadata management. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 2021, 56, 97–120. [CrossRef]

- Giebler, C.; Gröger, C.; Hoos, E.; Schwarz, H.; Mitschang, B. Leveraging the data lake: current state and challenges. In Proceedings of the Big Data Analytics and Knowledge Discovery: 21st International Conference, DaWaK 2019, Linz, Austria, August 26–29, 2019, Proceedings 21. Springer, 2019, pp. 179–188.

- Madsen, M. How to Build an enterprise data lake: important considerations before jumping in. Third Nature Inc 2015, pp. 13–17.

- Gupta, S.; Giri, V. Practical Enterprise Data Lake Insights: Handle Data-Driven Challenges in an Enterprise Big Data Lake; Apress, 2018.

- Lagos, J.; Cravero, A. Process Formalization Proposal for Data Ingestion in a Data Lake. In Proceedings of the 2022 41st International Conference of the Chilean Computer Science Society (SCCC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–8.

- Anisetti, M.; Ardagna, C.A.; Braghin, C.; Damiani, E.; Polimeno, A.; Balestrucci, A. Dynamic and scalable enforcement of access control policies for big data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Management of Digital EcoSystems, 2021, pp. 71–78.

- Quinto, B.; Quinto, B. Big data governance and management. Next-Generation Big Data: A Practical Guide to Apache Kudu, Impala, and Spark 2018, pp. 495–506.

- Muñoz, A.P.; Martí, L.; Sánchez-Pi, N. Data Governance, a Knowledge Model Through Ontologies. In Proceedings of the Congreso Internacional de Tecnologías e Innovación, 2021.

- Mahanti.; Rupa. Data Governance Implementation – Critical Success Factors. Software Quality Professional Magazine 2018, 20.

- Saed, K.A.; Aziz, N.A.; Ramadhani, A.W.; Hassan, N.H. Data Governance Cloud Security Assessment at Data Center. 2018 4th International Conference on Computer and Information Sciences (ICCOINS) 2018, pp. 1–4.

- N.Maniam, J.; Singh, D. TOWARDS DATA PRIVACY AND SECURITY FRAMEWORK IN BIG DATA GOVERNANCE. International Journal of Software Engineering and Computer Systems 2020.

- Liu, W. How Data Security Could Be Achieved in The Process of Cloud Data Governance? In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Management Science and Software Engineering (ICMSSE 2022). Atlantis Press, 2022, pp. 114–120.

- Dingre, S.S. Exploration of Data Governance Frameworks, Roles, and Metrics for Success. Journal of Artificial Intelligence & Cloud Computing 2023.

- Khatri, V.; Brown, C.V. Designing data governance. Communications of the ACM 2010, 53, 148–152.

- Petersen, K.; Feldt, R.; Mujtaba, S.; Mattsson, M. Systematic mapping studies in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 12th international conference on evaluation and assessment in software engineering (EASE). BCS Learning & Development, 2008.

- Sommerville, I. Software engineering. 10th. Book Software Engineering. 10th, Series Software Engineering 2015, 10.

- Steurer, J. The Delphi method: an efficient procedure to generate knowledge. Skeletal Radiology 2011, 40, 959–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-011-1145-z. [CrossRef]

- Nadal, S.; Herrero, V.; Romero, O.; Abelló, A.; Franch, X.; Vansummeren, S.; Valerio, D. A software reference architecture for semantic-aware Big Data systems. Information and software technology 2017, 90, 75–92. [CrossRef]

- Brooke John. SUS: A ’Quick and Dirty’ Usability Scale. In Usability Evaluation In Industry; CRC Press, 1996; pp. 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781498710411-35.

- Lagos, J.; Cravero, A. Reference architecture for data ingestion in Data Lake. In Proceedings of the 2023 18th Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies (CISTI). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–9.

- Bangor Aaron.; Kortum Philip.; Miller James. Determining what individual SUS scores mean. Journal of Usability Studies 2009. https://doi.org/10.5555/2835587.2835589. [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Bhatnagar, V. A cognitive approach for blockchain-based cryptographic curve hash signature (BC-CCHS) technique to secure healthcare data in Data Lake. Soft Computing 2021, p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Rieyan, S.A.; News, M.R.K.; Rahman, A.M.; Khan, S.A.; Zaarif, S.T.J.; Alam, M.G.R.; Hassan, M.M.; Ianni, M.; Fortino, G. An advanced data fabric architecture leveraging homomorphic encryption and federated learning. Information Fusion 2024, 102, 102004. [CrossRef]

- Yeng, P.K.; Diekuu, J.B.; Abomhara, M.; Elhadj, B.; Yakubu, M.A.; Oppong, I.N.; Odebade, A.; Fauzi, M.A.; Yang, B.; El-Gassar, R. HEALER2: A Framework for Secure Data Lake Towards Healthcare Digital Transformation Efforts in Low and Middle-Income Countries. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Networks and Computer Communications (ETNCC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–9.

- Shang, X.; Subenderan, P.; Islam, M.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Gupta, N.; Panda, A. One stone, three birds: Finer-grained encryption with apache parquet@ large scale. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2022, pp. 5802–5811.

- Hamadou, H.B.; Pedersen, T.B.; Thomsen, C. The danish national energy data lake: Requirements, technical architecture, and tool selection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1523–1532.

- Revathy, P.; Mukesh, R. Analysis of big data security practices. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd International Conference on Applied and Theoretical Computing and Communication Technology (iCATccT). IEEE, 2017, pp. 264–267.

- Rawat, D.B.; Doku, R.; Garuba, M. Cybersecurity in big data era: From securing big data to data-driven security. IEEE Transactions on Services Computing 2019, 14, 2055–2072. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, C.; Guan, S. A data lake-based security transmission and storage scheme for streaming big data. Cluster Computing 2024, 27, 4741–4755. [CrossRef]

- Kai, L.; Liang, Z.; Yaojing, Y.; Dazhu, Y.; Min, Z. Research on Federated Learning Data Management Method Based on Data Lake Technology. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Computers, Information Processing and Advanced Education (CIPAE). IEEE, 2023, pp. 385–390.

- Ancán, O.; Reyes, M. Cabuplot: Categorical Bubble Plot for systematic mapping studies, 2020.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).