Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Mapping Pinus kesiya Forest

2.3. Carbon Density of Pinus kesiya Forest

| Biomass component | Biomass model | Carbon conversion coefficient |

| Stem | WS=0.0808 D2.5374 | 0.52 |

| Branches | WB=0.0007 D3.4663 | 0.50 |

| Leaves | WL=0.0015 D2.504 | 0.51 |

| Roots | WR=0.0023 D3.0644 | 0.53 |

2.4. Estimating Carbon Stock in Pinus kesiya Forest

2.5. Correlation Between Carbon Stock and Topography

3. Results

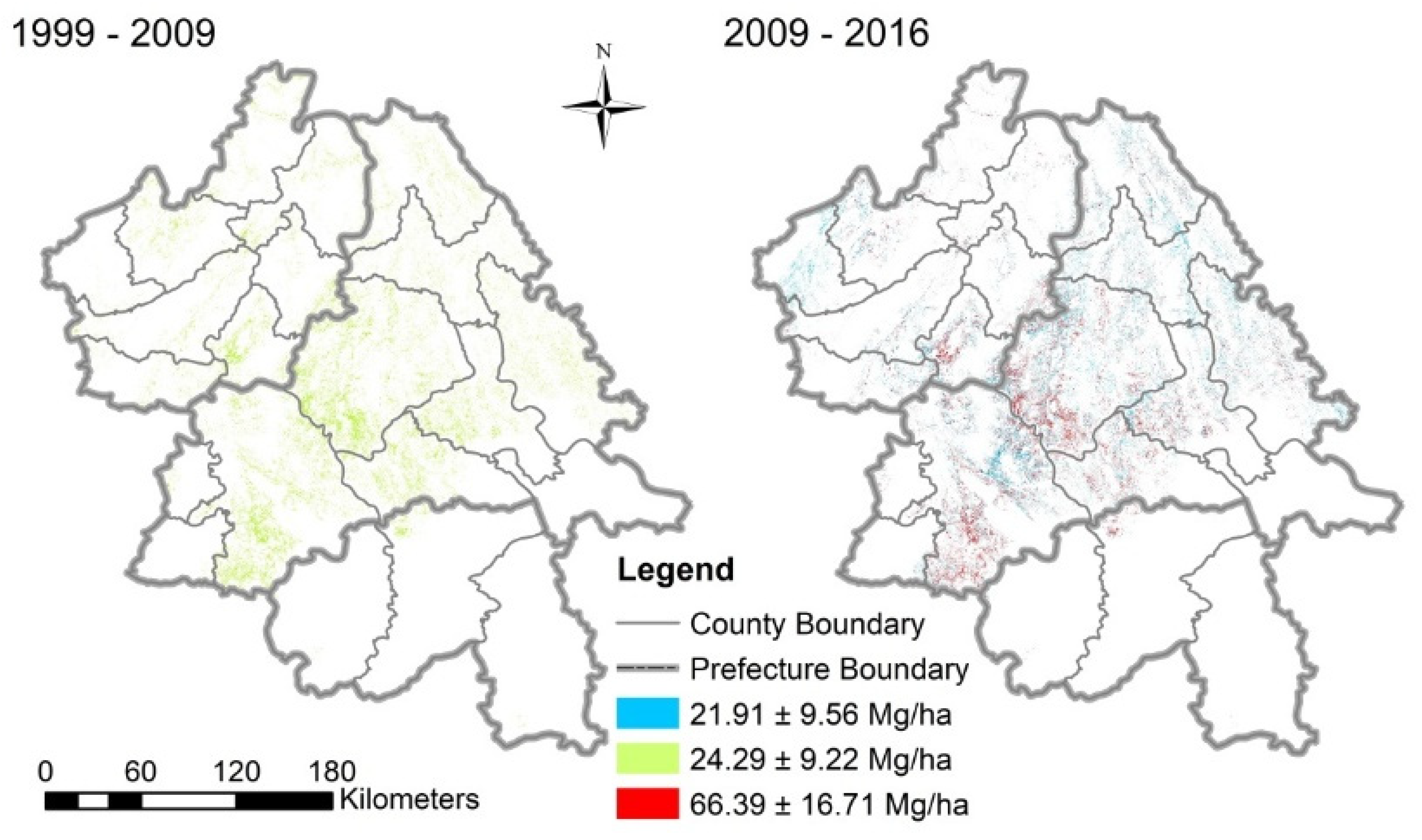

3.1. Pinus kesiya Forest MAPPING

3.2. Carbon Density at Different Forest Ages

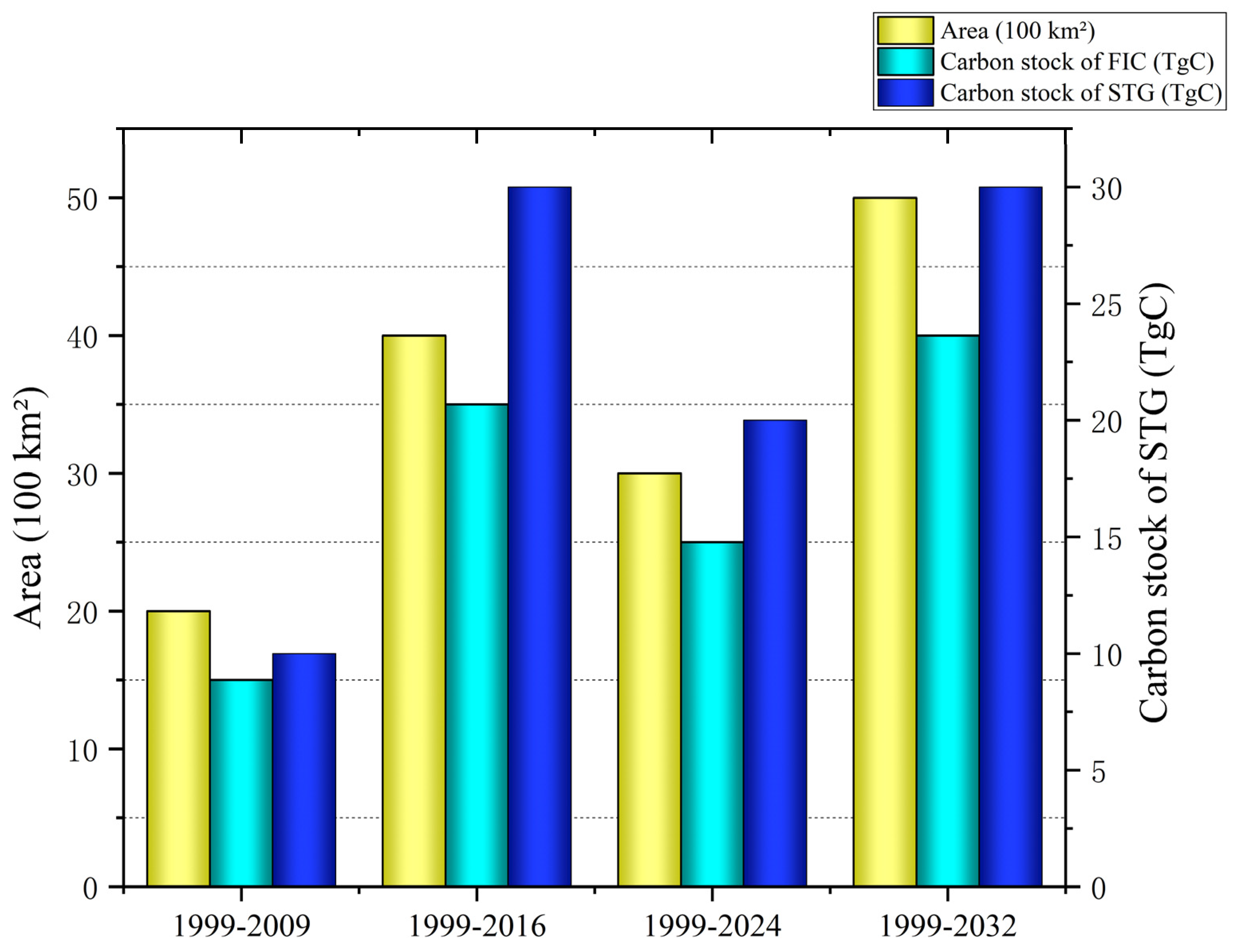

3.3. Carbon Stock Changes in Pinus kesiya Forest Planted Under GFGP

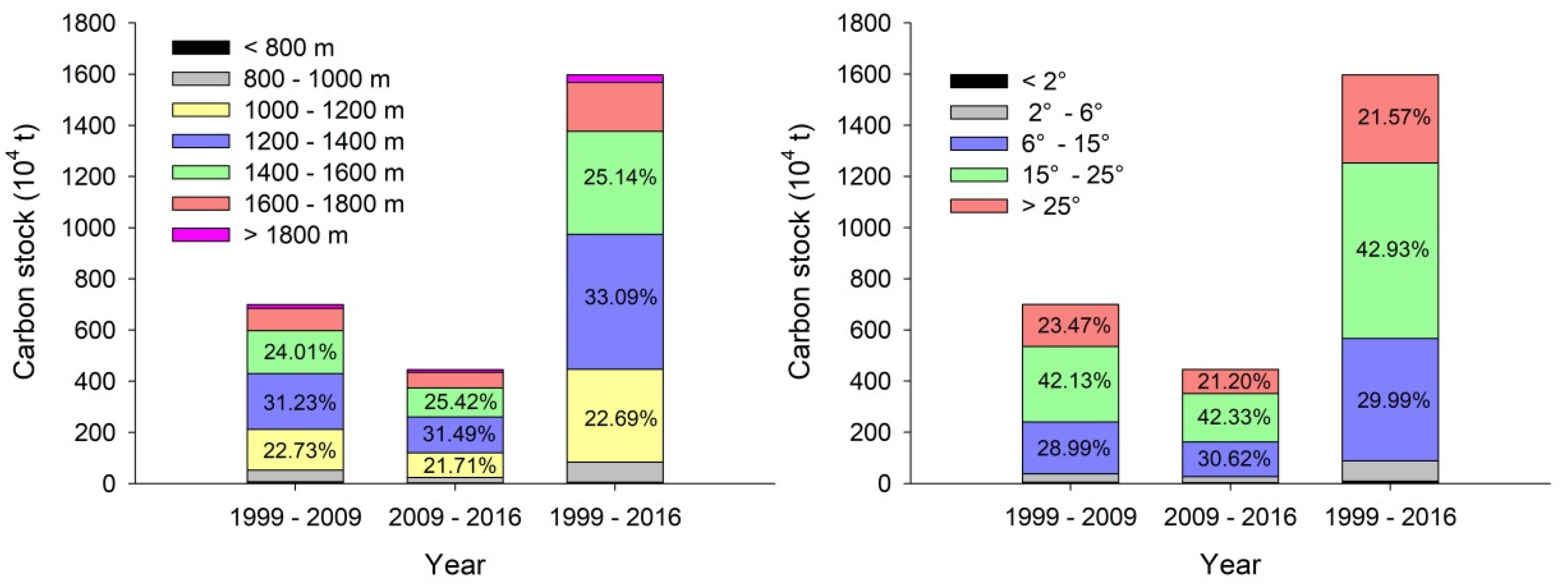

3.4. Carbon Stock Accumulation in Forest on Different Slope and Elevation Classes

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of GFGP on Regional Carbon Stocks

4.2. Impact of Forest Age on Carbon Density and Implications of Forest Management

4.3. Factors Affecting Carbon Density

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data availability statement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Lucas, R.M.; Mitchell, A.L.; Armston, J. Measurement of Forest Above-Ground Biomass Using Active and Passive Remote Sensing at Large (Subnational to Global) Scales. Curr for Rep 2015, 1, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarvey, J.C.; Thompson, J.R.; Epstein, H.E.; Shugart, H.H. Carbon storage in old-growth forests of the Mid-Atlantic: toward better understanding the eastern forest carbon sink. Ecology (Durham) 2015, 96, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Guo, Z.; Hu, H.; Kato, T.; Muraoka, H.; Son, Y. Forest biomass carbon sinks in East Asia, with special reference to the relative contributions of forest expansion and forest growth. Global Change Biol 2014, 20, 2019–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and Climate Change: Forcings, Feedbacks, and the Climate Benefits of Forests. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arora, V.K.; Montenegro, A. Small temperature benefits provided by realistic afforestation efforts. Nat Geosci 2011, 4, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuss, S.; Canadell, J.G.; Peters, G.P.; Tavoni, M.; Andrew, R.M.; Ciais, P.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, C.D.; Kraxner, F.; Nakicenovic, N.; et al. Betting on negative emissions. Nat Clim Change 2014, 4, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, A.; Pugh, T.A.M.; Bayer, A.D.; Li, W.; Leung, F.; Bondeau, A.; Doelman, J.C.; Humpenöder, F.; Anthoni, P.; Bodirsky, B.L.; et al. Large uncertainty in carbon uptake potential of land-based climate-change mitigation efforts. Global Change Biol 2018, 24, 3025–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O.; Fonseca, M.G.; Rosan, T.M.; Vedovato, L.B.; Wagner, F.H.; Silva, C.V.J.; Silva Junior, C.H.L.; Arai, E.; Aguiar, A.P.; et al. 21st Century drought-related fires counteract the decline of Amazon deforestation carbon emissions. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 512–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometto, J.P.; Aguiar, A.P.; Assis, T.; Soler, L.; Valle, P.; Tejada, G.; Lapola, D.M.; Meir, P. Amazon forest biomass density maps: tackling the uncertainty in carbon emission estimates. Climatic Change 2014, 124, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneth, A.; Sitch, S.; Pongratz, J.; Stocker, B.D.; Ciais, P.; Poulter, B.; Bayer, A.D.; Bondeau, A.; Calle, L.; Chini, L.P.; et al. Historical Carbon Dioxide Emissions Caused by Land-Use Changes are Possibly Larger than Assumed. Nat Geosci 2017, 10, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, J.B.; Birdsey, R.A.; Joyce, L.A.; Ryan, M.G. Tree age, disturbance history, and carbon stocks and fluxes in subalpine Rocky Mountain forests. Global Change Biol 2008, 14, 2882–2897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EGGERS, J.; LINDNER, M.; ZUDIN, S.; ZAEHLE, S.; LISKI, J. Impact of changing wood demand, climate and land use on European forest resources and carbon stocks during the 21st century. Global Change Biol 2008, 14, 2288–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waggoner, P.E. Using the Forest Identity to Grasp and Comprehend the Swelling Mass of Forest Statistics. The International Forestry Review 2008, 10, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avitabile, V.; Herold, M.; Heuvelink, G.B.M.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Asner, G.P.; Armston, J.; Ashton, P.S.; Banin, L.; Bayol, N.; et al. integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Global Change Biol 2016, 22, 1406–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.C.; Costa, M.H.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; de Barros Viana Hissa, L. Historical land use change and associated carbon emissions in Brazil from 1940 to 1995. Global Biogeochem Cy 2012, 26, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ma, Y.; Aide, T.M.; Liu, W. Past, present and future land-use in Xishuangbanna, China and the implications for carbon dynamics. Forest Ecol Manag 2008, 255, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, F.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X.; Fisher, B.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y.; Yu, D.W.; Wilcove, D.S. Opportunities for biodiversity gains under the world’s largest reforestation programme. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Significant trade-off for the impact of Grain-for-Green Programme on ecosystem services in North-western Yunnan, China. The Science of the Total Environment 2017, 574, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. China’s new forests aren’t as green as they seem. Nature 2011, 477, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyog, N.D.; Lumbres, R.I.C.; Lee, Y.J. Mapping of the spatial distribution of carbon storage of the Pinus kesiya Royle ex Gordon (Benguet pine) forest in Sagada, Mt. Province, Philippines. J Sustain Forest 2018, 37, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamyong, S.; Sumanochitraporn, S. Role of a Pine (Pinus kesiya) Plantation on Water Storage in the Doi Tung Reforestation Royal Project, Chiang Rai Province, Northern Thailand. 2014.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wan, C. Carbon sequestration potential of the stands under the Grain for Green Program in Yunnan Province, China. Forest Ecol Manag 2009, 258, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Su, J.; Lang, X.; Liu, W.; Ou, G. Positive relationship between species richness and aboveground biomass across forest strata in a primary Pinus kesiya forest. Sci Rep-Uk 2018, 8, 2227–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiaojiao, W.U.; Guanglong, O.U.; Qingtai, S.; University, S.F. Remote sensing estimation of the biomass of Pinus kesiya var. langbianensis forest based on BP neural networks. Journal of Central South University of Forestry & Technology 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lumbres, R.I.C.; Lee, Y.J. Aboveground biomass mapping of La Trinidad forests in Benguet, Philippines, using Landsat Thematic Mapper data and k-nearest neighbor method. Forest Science & Technology 2014, 10, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Fonseca, G.A.B.D.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Zhu, H.; Yang, J. A Phylogenetic Perspective on Biogeographical Divergence of the Flora in Yunnan, Southwestern China. Sci Rep-Uk 2017, 7, 43032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHEN, Q.; ZHENG, Z.; FENG, Z.; MA, Y.; SHA, L.; XU, H.; NONG, P.; LI, Z. Biomass and carbon storage of Pinus kesiya var. langbianensis in Puer, Yunnan. Yunnan Da Xue Hsüen Bao. Zi Ran Ke Xue Ban 2014, 36, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zianis, D.; Mencuccini, M. On simplifying allometric analyses of forest biomass. Forest Ecol Manag 2004, 187, 311–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, C.; Fan, Q.; Li, W.; Wu, Y.; Xu, H.; Ou, G. Spatial Effects Analysis on Individual-Tree Aboveground Biomass in a Tropical Pinus Kesiya Var. Langbianensis Natural Forest in Yunnan, Southwestern China. Forests 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, C.A.; Del Valle, J.I.; Orrego, S.A.; Moreno, F.H.; Harmon, M.E.; Zapata, M.; Colorado, G.J.; Herrera, M.A.; Lara, W.; Restrepo, D.E.; et al. Total carbon stocks in a tropical forest landscape of the Porce region, Colombia. Forest Ecol Manag 2007, 243, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU, D.; CHEN, Y.; CAI, W.; DONG, W.; XIAO, J.; CHEN, J.; ZHANG, H.; XIA, J.; YUAN, W. in The contribution of China’s Grain to Green Program to carbon sequestration : Coupled Natural and Human Systems: A Landscape Ecology Perspective, Dordrecht, 2014/1/1, 2014; Springer: Dordrecht, 2014; pp 1675-1688.

- Carriere, A.; Le Bouteiller, C.; Tucker, G.E.; Klotz, S.; Naaim, M. Impact of vegetation on erosion; insights from the calibration and test of a landscape evolution model in alpine badland catchments. Earth Surf Proc Land 2020, 45, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Xu, J.; Dai, Z.; Cannon, C.H.; Grumbine, R.E. Increasing tree cover while losing diverse natural forests in tropical Hainan, China. Reg Environ Change 2014, 14, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulesza, K.; Hościło, A. Temporal Patterns of Vegetation Greenness for the Main Forest-Forming Tree Species in the European Temperate Zone. Remote Sensing (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 16, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, F.; Jaramillo, V.J.; Bhaskar, R.; Gavito, M.; Siddique, I.; Byrnes, J.E.K.; Balvanera, P. Carbon Accumulation in Neotropical Dry Secondary Forests: The Roles of Forest Age and Tree Dominance and Diversity. Ecosystems (New York) 2018, 21, 536–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregitzer, K.S.; Euskirchen, E.S. Carbon cycling and storage in world forests: biome patterns related to forest age. Global Change Biol 2004, 10, 2052–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Su, J.; Liu, W.; Lang, X.; Huang, X.; Jia, C.; Zhang, Z.; Tong, Q.; Hui, D. Changes in Biomass Carbon and Soil Organic Carbon Stocks following the Conversion from a Secondary Coniferous Forest to a Pine Plantation. Plos One 2015, 10, e135946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, G.; Wang, Q. Effects of climate and forest age on the ecosystem carbon exchange of afforestation. J Forestry Res 2020, 31, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Brandt, M.; Yue, Y.; Ciais, P.; Rudbeck Jepsen, M.; Penuelas, J.; Wigneron, J.; Xiao, X.; Song, X.; Horion, S.; et al. Forest management in southern China generates short term extensive carbon sequestration. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 110–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.M.; Martins, S.V.; de Oliveira Neto, S.N.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Martorano, L.G.; Monsanto, L.D.; Cancio, N.M.; Gastauer, M. Intensification of shifting cultivation reduces forest resilience in the northern Amazon. Forest Ecol Manag 2018, 430, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Liu, S.; Sun, P.; Agathokleous, E. Impacts of forest management intensity on carbon accumulation of China’s forest plantations. Forest Ecol Manag 2020, 472, 118252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiwu, Z.; Wangjun, L.; Yiping, Z.; Mingchun, P.; Chongyun, W.; Liqing, S.; Yuntong, L.; Qinghai, S.; Xuehai, F.; Yanqiang, J. Responses of the Carbon Storage and Sequestration Potential of Forest Vegetation to Temperature Increases in Yunnan Province, SW China. Forests 2018, 9, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baishya, R.; Barik, S.K. Estimation of tree biomass, carbon pool and net primary production of an old-growth Pinus kesiya Royle ex. Gordon forest in north-eastern India. Annals of Forest Science. 2011, 68, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Guan, D.; Xiao, L.; Peart, M.R. Ecosystem carbon storage affected by intertidal locations and climatic factors in three estuarine mangrove forests of South China. Reg Environ Change 2019, 19, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COHEN, W.B.; GOWARD, S.N. Landsat’s Role in Ecological Applications of Remote Sensing. Bioscience 2004, 54, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.Y.; Chen, A.P.; Peng, C.H.; Zhao, S.Q.; Ci, L. Changes in forest biomass carbon storage in China between 1949 and 1998. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Fotis, A.T.; Morin, T.H.; Fahey, R.T.; Hardiman, B.S.; Bohrer, G.; Curtis, P.S. Forest structure in space and time: Biotic and abiotic determinants of canopy complexity and their effects on net primary productivity. Agr Forest Meteorol 2018, 250-251, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Shi, Y.; Fang, H.; Zhou, G.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, J.; Ji, B.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; et al. Vegetation carbon stocks driven by canopy density and forest age in subtropical forest ecosystems. The Science of the Total Environment 2018, 631-632, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HOUGHTON, R.A. Why are estimates of the terrestrial carbon balance so different? Global Change Biol 2003, 9, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Path row | 1999 | 2009 | 2016 |

| 129-44 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 129-45 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 130-43 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 130-44 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 130-45 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 131-43 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 131-44 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 131-45 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 132-43 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 132-44 | TM | TM | OLI |

| 1999-2009 | 1999 | ||||||

| Pinus kesiya | Other forest | Shrubland | Farmland | Construction land | Water | ||

| Pinus kesiya | 5515.21 | 2708.89 | 2158.91 | 662.31 | 2.03 | 4.20 | |

| Other forest | 1299.43 | 24734.79 | 4746.38 | 3458.61 | 12.09 | 53.33 | |

| 2009 | Shrubland | 673.96 | 2547.54 | 4950.40 | 3407.16 | 15.40 | 5.61 |

| Farmland | 506.70 | 2442.33 | 6152.59 | 19482.85 | 148.67 | 72.55 | |

| Construction land | 3.81 | 99.33 | 111.99 | 726.44 | 136.17 | 18.40 | |

| Water | 1.50 | 29.63 | 23.85 | 89.27 | 10.70 | 174.25 | |

| 2009-2016 | 2009 | ||||||

| Pinus kesiya | Other forest | Shrubland | Farmland | Construction land | Water | ||

| Pinus kesiya | 7417.54 | 2187.67 | 1007.49 | 990.69 | 9.79 | 1.36 | |

| Other forest | 1745.18 | 26207.42 | 3742.85 | 4396.05 | 169.65 | 21.11 | |

| 2016 | Shrubland | 1244.42 | 3443.72 | 4198.67 | 4922.32 | 96.24 | 4.82 |

| Farmland | 558.38 | 2182.25 | 2475.19 | 17265.03 | 456.38 | 49.59 | |

| Construction land | 82.98 | 218.04 | 141.99 | 970.02 | 333.22 | 11.80 | |

| Water | 3.14 | 66.13 | 33.99 | 261.94 | 30.87 | 240.53 | |

| 1999-2009 | 2009-2016 | 1999-2016 | |

| Slope class | P value | P value | P value |

| S1 - S2 | - 0.0072 ** | - 0.0082 ** | - 0.0123 * |

| S1 - S3 | - 0.0051 ** | - 0.0037 ** | - 0.0088 ** |

| S1 - S4 | - 0.0033 ** | - 0.0019 ** | - 0.0065 ** |

| S1 - S5 | - 0.0006 *** | - 0.0005 *** | - 0.0024 ** |

| S2 - S3 | - 0.0049 ** | - 0.0032 ** | - 0.0084 ** |

| S2 - S4 | - 0.0032 ** | - 0.0018 ** | - 0.0063 ** |

| S2 - S5 | - 0.0005 *** | - 0.0004 *** | - 0.0019 ** |

| S3 - S4 | - 0.0034 ** | - 0.0034 ** | - 0.0070 ** |

| S3 - S5 | + 0.2342 n.s. | + 0.0746 n.s. | + 0.0871 n.s. |

| S4 - S5 | + 0.0175 * | + 0.0067 ** | + 0.0153 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).