1. Introduction

Demyelinating diseases (Dds) are chronic pathological processes that result from complex interactions between genetic and environmental variables, with the immune system’s involvement (Arneth, 2024; Moloney et al., 2024). One of the most widely studied Dds is multiple sclerosis (MS), which is characterized as a disorder of the central nervous system, where inflammation, demyelination, neurodegeneration, and death of glial cells occur (Guo et al., 2020; Osorio-Querejeta et al., 2017). MS affects about 2.1 million people worldwide; because it is a chronic degenerative disease, the patient often coexists with it for most of its useful life. Physical activity appears to aid in controlling multiple sclerosis symptoms (Fasczewski et al., 2017).

To study the complex mechanisms of Dds, such as MS, several experimental animal models, including toxic models of central demyelination, have been established (for review, see Denic et al., 2011; Torkildsen et al., 2013; Leo and Kipp, 2022). In the cuprizone toxicity model, young rodents are fed a diet containing cuprizone, a copper chelator, which leads to the death of oligodendrocytes and the activation of microglia (Skripuletz et al., 2011). Upon withdrawal of the cuprizone, spontaneous remyelination occurs. In rodents, cuprizone induces demyelination in the brain and cerebellum’s white and gray matter without affecting the peripheral nerves (Matsushima and Morell, 2001; Skripuletz et al., 2011). Apoptosis of primary oligodendrocytes in connection with microglia activation is a major histopathological feature of the animal model of demyelination by cuprizone. This pathological feature is also found in the formation of MS lesions in humans (Barnett and Prineas, 2004). Demyelinating conditions of the central nervous system constitute one of the causal factors of several limiting human neurological diseases, including aging ones.

In MS patients, physical exercise has been shown to produce beneficial therapeutic effects (Guo et al., 2020). On the other hand, in laboratory animals, regular physical exercise benefits the nervous system of the young, the adult, and the elderly (Batista-de-Oliveira et al., 2012; Fragoso et al., 2020). Physical exercise is known to improve the performance of tasks involving brain electrophysiological functions (Ozmerdivenli et al., 2005) and cognitive performance (Won et al., 2019) and attenuates the neural effects of aging (Batista-de-Oliveira et al., 2012; Latimer et al., 2011; Won et al., 2019). In the brains of animals, exercise is associated with neurogenesis and increased neuronal survival (Brown, 2003; Nguemeni et al., 2018; Van Praag et al., 1999). Exercise also increases vascular blood flow in the cerebellum and motor cortex (Black et al., 1990; Isaacs et al., 1992; Swain et al., 2003). Physical exercise on the treadmill at the beginning of life influences cerebral electrical activity, as evidenced by analyzing the propagation of the phenomenon known as cortical spreading depression [CSD] (Lima et al., 2014; Braz et al., 2023).

CSD consists of a reversible, propagating wave of reduction of the spontaneous cortical activity because of brain cell depolarization after electrical, mechanical, or chemical stimulation of one cortical point. Once initiated in the stimulated cortical area, CSD spreads slowly across the tissue (Leão, 1944; Guedes and Abadie-Guedes, 2019). CSD has been postulated as participating in several human neurological diseases, such as epilepsy, migraine, traumatic brain injury, and subarachnoid hemorrhage (see Lauritzen and Strong, 2017; Guedes and Abadie-Guedes, 2019 for an overview). Studies on animals revealed that CSD propagation can be accelerated or decelerated due to hormonal, pharmacologic, environmental, and nutritional manipulations (Guedes et al., 2017). These studies compellingly suggested that the analysis of CSD velocity of propagation represents a useful index to comprehend excitability-related processes underlying brain functioning (Guedes and Abadie-Guedes, 2019; Morais et al., 2020).

While, on one hand, there is still a lack of effective neuroprotective drugs designed to delay neurodegenerative processes, numerous reports suggest, on the other hand, that regular physical activity could potentially reduce the risk of neurological impairment in conditions such as MS, Stroke and Parkinson’s disease (Eldar and Marincek, 2000, Cotman et al. 2002, Smith and Zigmond, 2003, Zanotto et al., 2025; Clemente-Suárez et al., 2024). Furthermore, evidence of exercise-induced transcription enhancement of neurotrophic factors has been reported (Fragoso et al., 2020). Therefore, the effects of physical exercise are shown to be neuroprotective, promote brain health, precondition the brain against ischemic insult, and improve its long-term functioning (Zhang et al., 2013). Although pharmacological approaches are making great advances, there is evidence that non-pharmacological approaches, such as physical exercise, can promote anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective actions in patients with MS (Ochi, 2019).

This study aimed to examine the interaction between treadmill exercise and cuprizone-induced demyelination in the developing rat brain, as indexed by changes in the electrophysiological features of CSD, and on the immunolabeling pattern of glial reaction in exercised and sedentary rats. These parameters in normally myelinated rats have been compared to those of animals subjected to cuprizone diet-induced demyelination. We hypothesized that treadmill exercise would attenuate the brain’s ability to propagate CSD and protect against cuprizone-induced cortical demyelination and glial cells’ reaction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

The animals (Wistar rats) were handled following the norms of the Ethics Committee for Animal Research of our University (Approval protocol no. 23076.019381/2014-26), which complies with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, USA). Groups of 2-3 rats were housed in polypropylene cages (51 X 35.5 X 18.5 cm) in a room maintained at 23 ± 1 C with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 a.m.) and had free access to a lab chow diet with 23% protein.

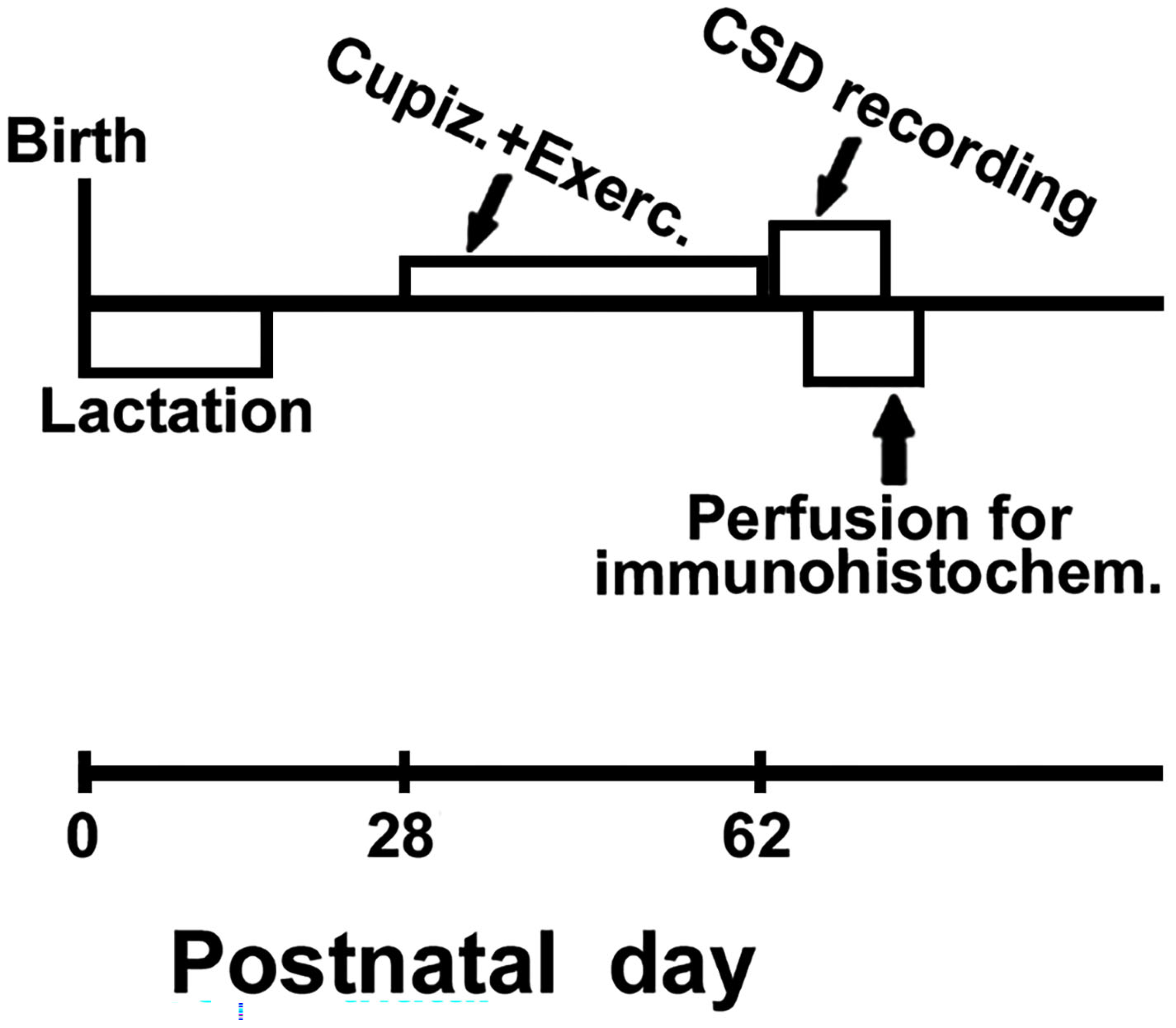

2.2. Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination

From postnatal day 28 (P28) to P62, rats were fed either the control diet (ConD; n = 19) or the cuprizone diet (CupD; n = 39), which contained 0.2% (w/w) cuprizone (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). We used cuprizone treatment as a model of toxic demyelination and remyelination (Merkler et al., 2009). As described below (part 2.3), both exercised (n=30) and sedentary animals (n=28) were subdivided into three treatment conditions, originating the six groups of this study: two groups received the control diet (9 exercised and 10 sedentary rats, respectively, groups no. 1 and 2), two groups received the demyelinating (cuprizone-based) diet (11 exercised and 10 sedentary rats; respectively groups no. 3 and 4), and two groups that, after

demyelination, were switched back to the control diet and experienced

remyelination for 6 weeks (10 exercised and 8 sedentary rats; groups no. 5 and 6). These six groups are presented in

Table 1.

2.3. Treadmill Exercise

The exercise was conducted on a motorized treadmill apparatus (Insight EP-131, 0° inclination) following the parameters of moderate exercise, as previously described (Lima et al., 2014). Over 7 weeks, one daily session of exercise (30 min/day) was performed on a 5-day/week basis, followed by a 2-day rest. The exercise was initiated on postnatal day 28 (P28) and terminated on P62 immediately before the CSD recording day. The treadmill running velocity was increased from 5 m/min during the first training week to 10 m/min during the second week and increased again to 15 m/min from the third week up to the end of the exercise period. The sedentary groups remained on the treadmill for the same period as the exercised animals; however, the treadmill was kept off. The body weights were measured on P30 and P60.

2.4. CSD Recording

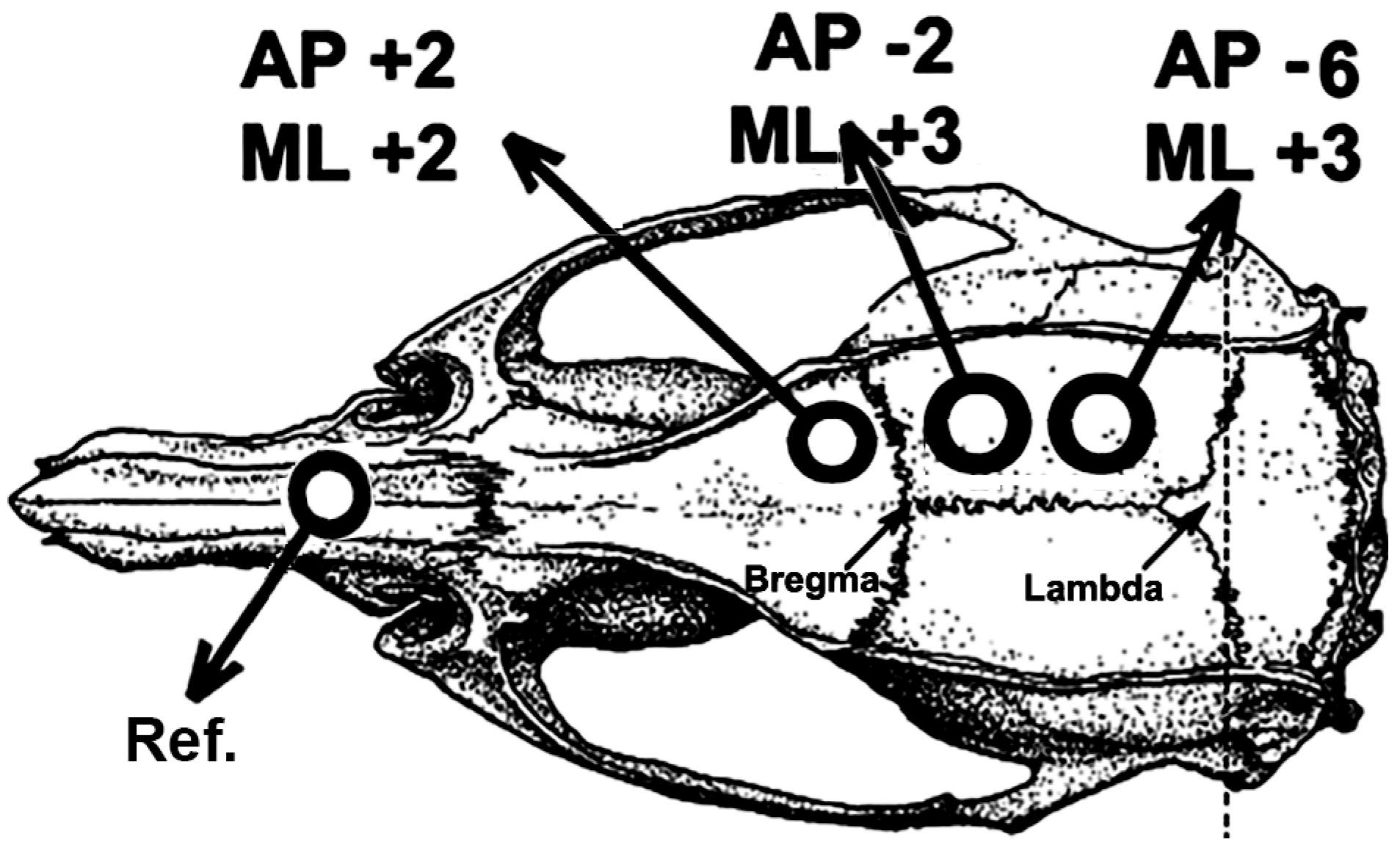

After the treadmill exercise and the demyelinating and re-myelinating dietary paradigms, rats were subjected to a CSD recording session for 4 h, as previously described (Lima et al., 2014). Under anesthesia (1g/kg urethane plus 40 mg/kg chloralose, i.p.), the rat’s head was secured into a stereotaxic apparatus (Kopf, USA), and three trephine holes (2–3 mm in diameter) were drilled on the right side of the skull. These holes - one at the frontal bone and two on the parietal bone - were aligned in the anterior-to-posterior direction and parallel to the midline. The center of the holes was set at the following stereotaxic coordinates (

Figure 1), according to the stereotaxic atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998): AP +2 / ML +2, AP -2 / ML +3 and AP -6 / ML +3. CSD episodes were elicited at 20-min intervals by applying, for 1 min, a cotton ball (1–2 mm diameter) soaked in 2% KCl solution (approximately 0.27 M) to the anterior (frontal) hole.

The slow direct-current (DC) potential change, which is the hallmark of CSD, was recorded at the two parietal points on the cortical surface using a pair of Ag-AgCl agar-Ringer electrodes. These electrodes consisted of plastic conic pipettes (5 cm length, 0.5 mm tip inner diameter), filled with Ringer solution solidified by adding 0.5% agar, into which a chlorided silver wire was inserted. A pair of such pipettes was fixed with cyanoacrylate glue so that each pair’s interelectrode distance was kept constant (distance for different pairs ranged from 4 to 6 mm). The electrode pair was attached to the electrode holder of the stereotaxic apparatus so the electrode tips could be gently placed on the intact dura-mater under low-power microscope control without excessive pressure on the cortical surface. A common reference electrode of the same type was placed on the nasal bones (

Figure 1). The CSD parameters (propagation velocity, amplitude, and duration of the negative DC-potential change) were measured as previously reported (Mendes-da-Silva et al., 2014). CSD velocity was calculated based on the time required for a CSD wave to cross the interelectrode distance. In measuring CSD parameters, the initial point of each DC negative rising phase was used as the reference point. During the recording session, rectal temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1°C using a heating blanket. At the end of the recording session, part of the animals was subjected to the perfusion-fixation procedures for subsequent immunohistochemical analysis (see point 2.5 below): trans-cardiac perfusion was performed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) followed by 0.4% paraformaldehyde fixation.

2.5. Immunohistochemical Analysis of Glial Cells

Eleven sedentary rats (groups 2, 4, and 6; n= 4, 3, and 4, respectively) and 11 exercised animals (groups 1, 3, and 5; n= 4, 3, and 4, respectively) were perfused, as described above. After being removed from the skull and immersed into the fixative for four hours, the brains were transferred to a 30% (w/v) sucrose solution for cryoprotection. Longitudinal serial sections (40-µm thickness) were obtained at -20

°C with a cryo-slicer (Leica 1850). Three series of sections were immunolabeled, respectively, 1) with mouse anti-APC to detect Oligodendrocytes (anti-APC, #OP62; Calbiochem); 2) with rat anti-myelin basic protein (MBP) antibody to detect myelin (anti-MBP, #MAB386, Millipore); 3) with a polyclonal antibody against the ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 (Iba1) to detect microglia (anti-Iba1, #019-19741; Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Free-floating, Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-washed (3 x for 5 min) sections were submitted to endogenous peroxidase blocking (2% H2O2 in 70% methanol for 10 min); then, sections were incubated for one h in Blocking Buffer solution (BB) containing 0.05 M (TBS) pH 7.4, 10% fetal calf serum, 3% bovine serum albumin and 1% Triton X-100. Afterward, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against rat anti-APC (1:250 diluted in BB solution) to detect Oligodendrocytes, mouse anti-MBP (1:1000 diluted in BB solution) to detect myelin, and rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:3000 diluted in BB solution) to detect microglia. After three washes with TBS + 1% Triton, sections were incubated at room temperature for one h with biotinylated secondary antibodies: rat anti-APC (1:500 diluted in BB solution) to detect Oligodendrocytes, mouse anti-MBP (1:200 diluted in BB solution) to detect myelin, and rabbit anti-Iba1 (1:500 diluted in BB solution) to detect microglia. Sections were then rinsed in TBS + 1% Triton and incubated with horseradish peroxidase streptavidin (1:500). The peroxidase reaction was visualized by incubating the sections in Tris buffer containing 0.5 mg/mL 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) and 0.33 μL/mL H

2O

2. Finally, sections were mounted, dehydrated in graded alcohols, and, after xylene treatment, were coverslipped in Entellan

®. For each animal, densitometric analysis was performed on four parallel longitudinal sections. In each section, we analyzed photomicrographs of four fields within the motor cortex (layer 5) using Image J software (National Institutes of Health, USA, version 1.46r). A Leica DMLS microscope coupled to a Samsung high-level color camera (model SHC-410NAD) was used to obtain digital images from brain sections. Images from the immunoreacted motor cortexes were obtained with a 20× microscope objective. Care was taken to obtain the digital images using the same light-intensity conditions. We analyzed the percentage of the area occupied by the immuno-labeled cells and their total immunoreactivity expressed as arbitrary units. A negative control section was included for each immunostaining reaction. In this section, the primary antibody was replaced with TBS. All negative control sections showed no specific staining.

Figure 2 presents the procedures along the experiment about the age range in which each procedure occurred.

2.6. Statistics

Intergroup differences were compared by ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis Analysis of Variance on Ranks, followed by a post hoc test when indicated. The statistical software used was “Sigmastat®” version 3.5. Differences were considered significant when p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Body Weight

At PND30, both sedentary and exercised animals that were treated with cuprizone displayed lower weights than the corresponding cuprizone-free groups (F

[1, 36] = 49.339;

p < 0.001). Such weight reduction persisted at PND60 (F [1,36] = 90.315;

p < 0.001). Furthermore, at PND60 the exercised groups presented with weight reduction in comparison with the corresponding sedentary groups (F

[1, 36] = 36.089;

p < 0.001). The mean ± SD body weights are in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Body weights (in g) of sedentary and exercised rats at postnatal days P30 and P60. Cuprizone-treated groups received a commercial diet containing 2 g/kg cuprizone from P28 to P62. Control groups received the same commercial diet but without cuprizone. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. * = p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding control group. # = p < 0.05 compared with the respective sedentary group.

Table 2.

Body weights (in g) of sedentary and exercised rats at postnatal days P30 and P60. Cuprizone-treated groups received a commercial diet containing 2 g/kg cuprizone from P28 to P62. Control groups received the same commercial diet but without cuprizone. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. * = p < 0.05 compared with the corresponding control group. # = p < 0.05 compared with the respective sedentary group.

| Groups |

Weight (in g) at

30 days (n)

|

Weight (in g) at

60 days (n)

|

| Control sedentary |

86.4 ± 14.3 (10) |

240.2 ± 13.1 (9) |

| Control Exercised |

87.4 ± 12.3 (10) |

201.3 ± 19.5 (9)# |

| Cuprizone-treated sedentary |

56.8 ± 16.8 (10)* |

181.3 ± 16.8 (9)* |

| Cuprizone-treated Exercised |

56.1 ± 10.7 (10)* |

151.7 ± 18.4 (9)*# |

3.2. CSD features

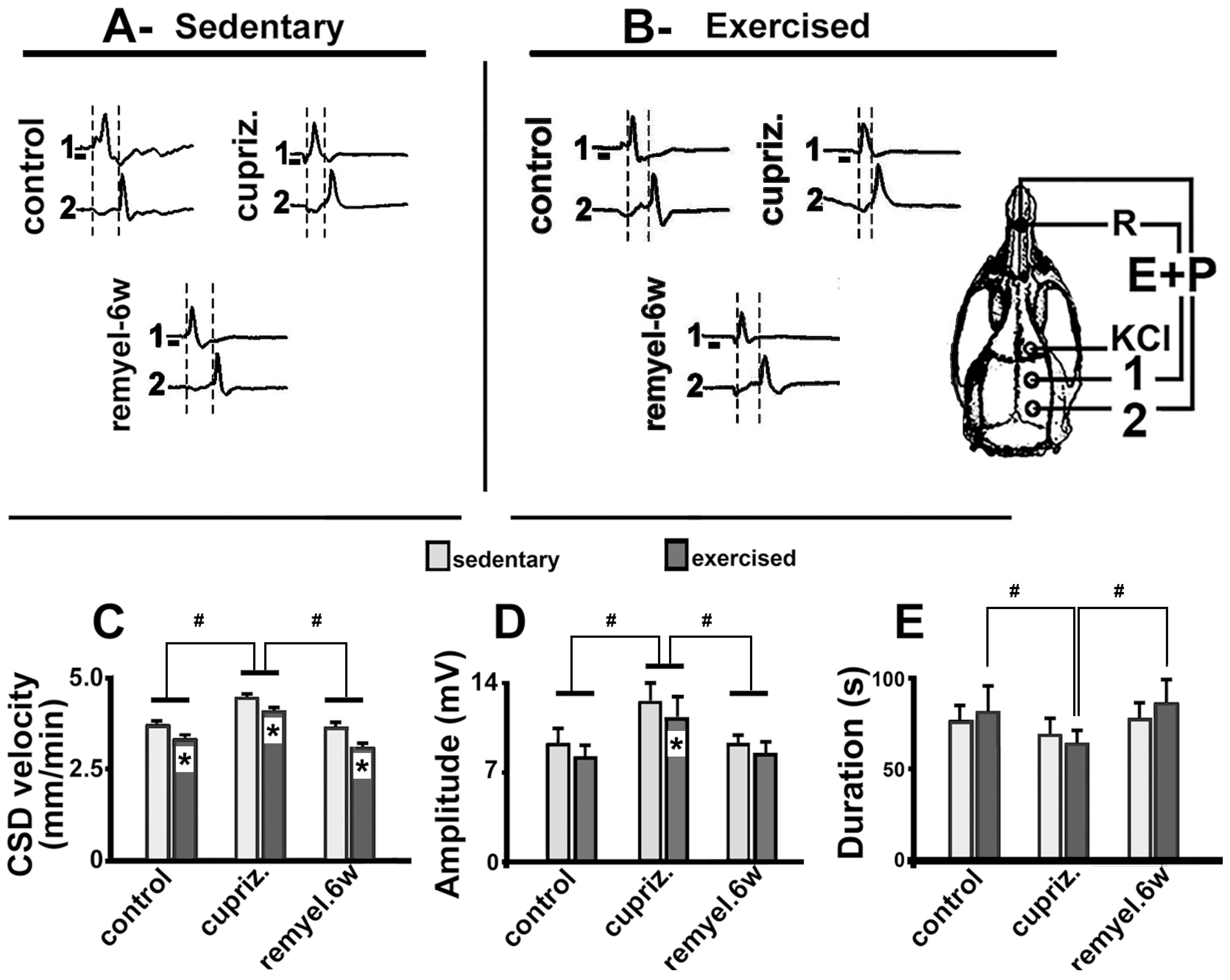

Typical electrophysiological recordings of CSD (slow DC potential change) are shown in

Figure 3 A and B. These recordings are from three sedentary (

Figure 3-A) and three exercised rats (

Figure 3-B), representing the three different dietary treatments: one rat from the control group, one from the cuprizone group, and one from the re-myelinated group. The 1-min stimulation with 2% KCl at one point of the frontal cortex usually elicited a single CSD episode that propagated without interruption and was recorded by the two electrodes located more posteriorly on the surface of the parietal cortex (see stimulation- and recording-points in the skull diagram of

Figure 3). In each recording point, the appearance of the slow potential change confirmed the presence of CSD after KCl application. As a rule, the electrophysiological changes caused by CSD always recovered after a few minutes, and we have kept a 20-min interval between subsequent KCl stimulations over the 4-h recording session, as mentioned in methods (part 2.4 above).

ANOVA revealed that both exercise (F

[1, 52] = 176.596;

p < 0.001) and cuprizone treatment (F

[2, 52] = 277.867;

p < 0.001) affected CSD propagation; no interaction between these two factors was observed (F

[3, 52] = 1.869;

p = 0.165). In the sedentary condition, the Holm-Sidak test indicated that cuprizone treatment was associated with increased CSD velocity (4.4 ± 0.2 mm/min) compared with the group fed the control diet (3.7 ± 0.1 mm/min;

p < 0.001). This effect was reversed in the remyelinated animals that, after cuprizone treatment, returned to the normal diet (without cuprizone) for 6 weeks (CSD velocities of 3.6 ± 0.1 mm/min). Compared with those velocities, treadmill exercise reduced the propagation rate of CSD (

p < 0.005) in all groups (3.3 ± 0.2 mm/min in the control group, 4.0 ± 0.1 mm/min in the demyelinated group, and 3.0 ± 0.1 mm/min in the re-myelinated group). Data are in the bar graphic of

Figure 3C.

The amplitude and duration of the negative slow potential shift, which is the hallmark of CSD, are shown in

Figure 3D and

3E, respectively. Regarding amplitude, ANOVA revealed a main effect of exercise (F

[1, 52] = 8.884;

p < 0.005) and cuprizone treatment (F

[2, 52] = 24.671;

p < 0.001); no interaction between the two factors (exercise and cuprizone treatment) was observed (F

[3, 52] = 0.237;

p = 0.790). The

post-hoc test indicated that exercised rats presented with a decreased (

p < 0.05) CSD amplitude (8.1 ± 0,9 mV) in comparison with the sedentary group (9.5 ± 1,8 mV). Cuprizone-treated animals presented with an increased (

p < 0.01) amplitude (12.4 ± 1.9 mV) in comparison with the control rats (9.5 ± 1.8 mV) and the remyelinated group (9.1 ± 0.8 mV). Regarding CSD duration, ANOVA revealed no significant intergroup difference among sedentary animals (F

[1, 52] = 0.372;

p = 0.544). In the exercised rats, demyelination was associated with shorter CSD duration (F

[2, 52] = 8.101;

p < 0.001).

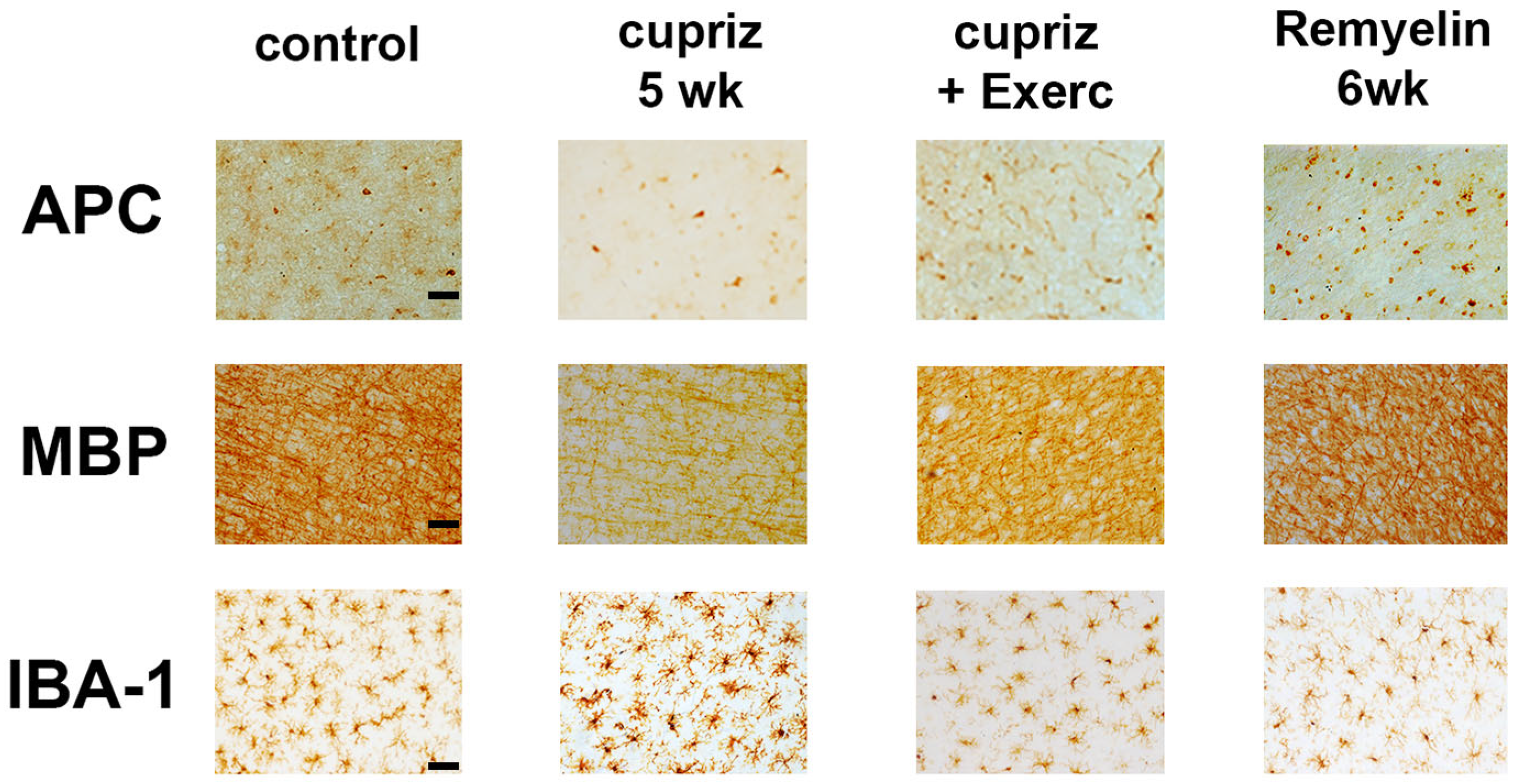

3.3. Immunohistochemistry and Densitometric Analysis

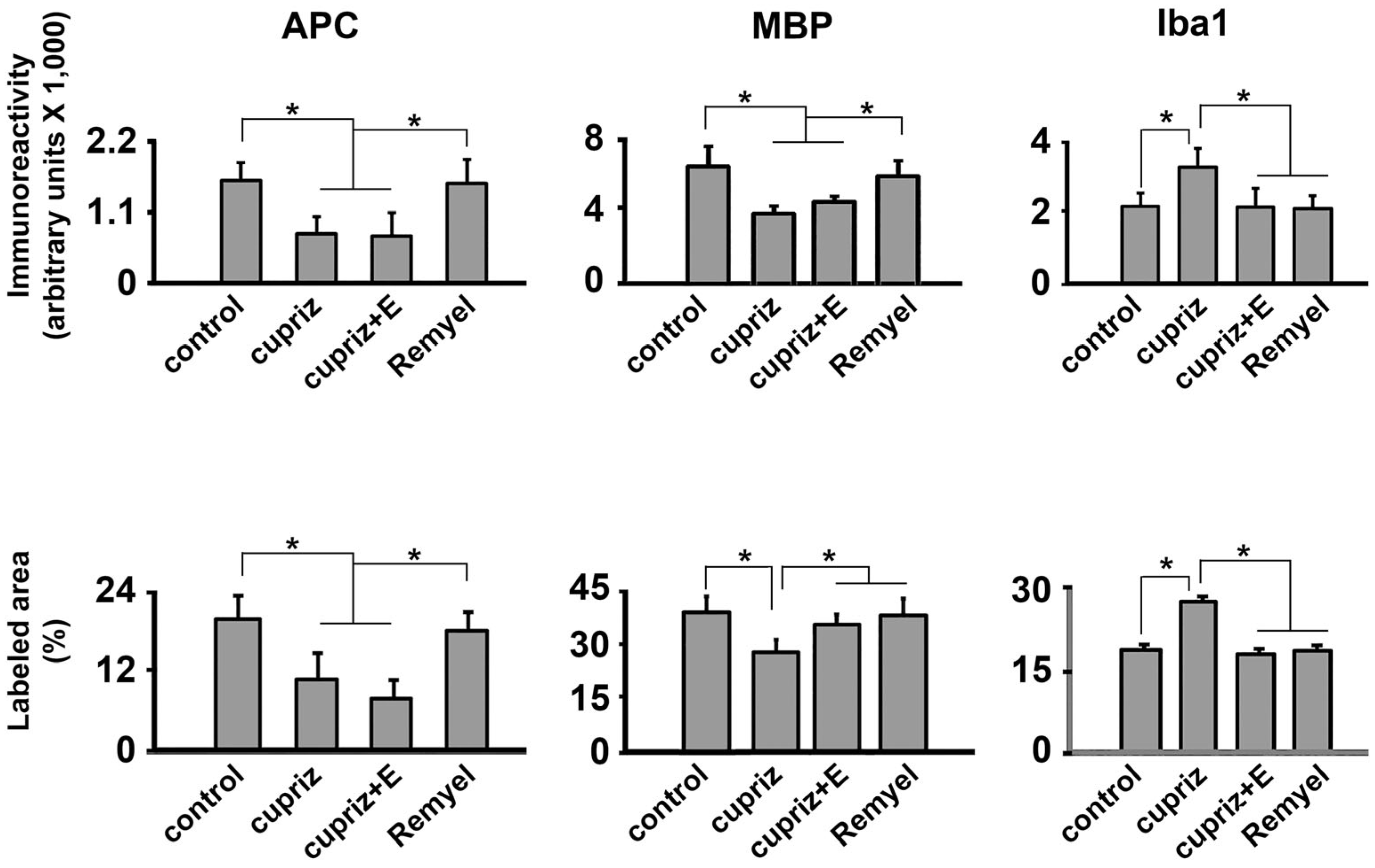

Figure 4 (photomicrographs) and 5 (bar graphics) show the effect of dietary administration of cuprizone and exercise on the immunolabeled APC, MBP, and Iba1-positive cells within the motor cortex.

The Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA revealed that the cuprizone treatment was associated with a decreased immunoreactivity for APC (H = 119.517 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p < 0.001) and MBP (H = 142.707 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p <0.001), and an increased immunoreactivity for Iba1-containing microglia (H = 83.812 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p <0.001) (

Figure 3 and 4). Microglial cells showed an increased immunoreactivity pattern in both the exercised and the cuprizone-treated groups. We had previously observed an immunoreactive pattern in the exercised groups, as microglia has both a pro-inflammatory and an anti-inflammatory effect (Lima et al., 2014).

Regarding the percentage of labeled area, the oligodendrocyte labeling (H = 138.911 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p <0.001) and the myelin labeled area (H = 107.105 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p <0.001) were significantly decreased in the groups treated with cuprizone compared with the control group. In contrast, cuprizone treatment was associated with an increased Iba1 labeled area (H = 106.458 with 3 degrees of freedom;

p <0.001). These data are in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

The cuprizone-induced demyelination model and various physical exercise paradigms are widely used to experimentally study pathological processes in the nervous system. The cuprizone model, for instance, is a well-established tool for inducing demyelination in rodents, mimicking certain aspects of multiple sclerosis in humans (Smith, 2021). Similarly, physical exercise has been shown to have neuroprotective effects and can influence various physiological processes in the brain (Fragoso et al., 2020). However, associating the two paradigms in a single study is not common. Our study pioneerly associated both models (cuprizone and exercise) and confirmed the deleterious effect of cuprizone on rat brain myelination, which was positively attenuated by treadmill exercise early in life. The effects of cuprizone and exercise could be demonstrated via electrophysiological measurements (CSD propagation) and glial immunohistochemical analysis.

The reduced body weight in the cuprizone-treated and exercised animals aligns with previous studies (Zhen et al., 2017 and Lima et al., 2014, respectively). The present results are also coherent with studies suggesting that cortical myelin is important in determining CSD propagation velocity (Merkler et al., 2009). We observed that cuprizone-demyelinated rats showed accelerated CSD propagation, indicating that cortical myelin is inversely correlated with the CSD propagation velocity. In support of this observation, demyelinated animals that were remyelinated (by further feeding again a cuprizone-free diet) presented with CSD velocities comparable to those of the control animals. In addition, our CSD propagation data support the previous suggestion about the involvement of cortical myelin in ion homeostasis in the cerebral cortex (Merkler et al., 2009).

Furthermore, the observation that the remyelinated animals presented with normal (control-like) CSD velocities reinforces the direct participation of myelin in CSD propagation rather than an indirect myelin action. The CSD modulation by myelin is dichotomous: transgenic mice expressing hypermyelinated brains displayed reduced CSD propagation velocity (Merkler et al., 2009), which supports the assumption that CSD propagation is inversely correlated with cortical myelin content. Interestingly, studies in early malnourished rats demonstrated that the malnourished brain propagates CSD significantly faster than the well-nourished control (Mendes-da-Silva et al., 2014), and malnourished animals presented with lower myelin content as compared with well-nourished animals (Patro et al., 2019). It is relevant to mention that, in contrast, rats that were overnourished during suckling (rats suckled in small litters, with three pups only) presented with decelerated CSD propagation (Rocha-de-Melo et al., 2006). Such evidence also supports the involvement of the brain’s myelin content in CSD propagation. Nevertheless, other nutrition-associated factors, like neurotransmitter activity, cell-packing density, or neuron-to-glia ratio, have also to be considered, as previously discussed (Merkler et al., 2009).

The development and maintenance of neural functions depend largely on the glial cell’s physiological activity. While oligodendrocytes are the cells responsible for myelination, the microglial cells are involved in the immune action in the brain, behaving, therefore, as immune cells of the nervous tissue (Carson, 2002; Pereira-Iglesias et al., 2025). The reduced glial cell activity is an important factor for our CSD findings as the evidence points to the glial cells’ participation in the cortical resistance to CSD propagation (Largo et al., 1997). Also, the present data on MBP-immunolabeling confirmed the occurrence of demyelination and remyelination processes, corroborating with previous investigations (Merkler et al., 2009; Tagge, 2016; Osorio-Querejeta, 2017). Running-exercised mice presented with plastic alterations in the brain, such as complex tree planting, that correlated with motor functions (Tatsumi, 2016). These alterations lead us to believe that the neural plasticity caused by exercise can attenuate the toxic effects of cuprizone.

Our studies evidenced the importance of physical exercise and its potential neuroprotection as a non-pharmacological intervention in pathologies where demyelination occurs. Studies in rodents and humans indicate that physical exercise improves both cognitive and motor functions in neurodegenerative models for stroke (Hugues et al., 2021), Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis (Clemente-Suárez et al., 2024; Cruise et al., 2011, Heyn et al., 2004). In a mouse study, exercise increased oligodendrogenesis in the intact spinal cord (Krityakiarana et al., 2010). Another relevant factor of our study is that myelin presented a lower immunoreactivity pattern in the groups treated with cuprizone. This lower immunoreactivity would be expected because the cells responsible for myelinization of the central nervous system were reduced. In a study in mice, exercise improved neuromuscular function and induced early protection against axonal damage and loss of proteins associated with myelin in the striatum and corpus callosum, in addition to an attenuation of microglia activation in these brain regions (Mandolesi et al., 2019). Preclinical studies suggest that exercise may involve multiple immunoregulatory mechanisms, probably due to T-cell response and brain infiltration attenuation. However, direct neurotrophin-mediated neuroprotective mechanisms are likely involved (Gentile et al., 2019).

5. Limitations of Our Study

5.1. Animal’s Sex

Our study examined only male rats; this limitation was motivated by the female rat’s hormonal oscillations, which are fast and can influence behavioral and brain CSD features (Accioly and Guedes, 2020) and can also influence the cuprizone effect (Xavier et al., 2023). We recognize the need to extend our observations to the female rat. However, it is a common strategy to concentrate some initial efforts on studying male rats and only then, with the male outcome as a well-established database, investigating female rats with the same methodologies. (Araújo et al., 2023).

5.2. Animal Species

Whether the demyelination/exercise interaction demonstrated here can be extrapolated from the rat to other mammal species and the developing human brain is unknown. At least among the two most used rodent species - rat and mouse - the cuprizone effects are about the same (Zhen et al., 2017). If this extrapolation can be confirmed, the evidence suggests a possible relevant implication of our novel findings in the developing rat brain. Nevertheless, we recognize the importance of replicating our findings in animal species other than the rat to strengthen our conclusions. However, the lack of such additional studies does not invalidate our results.

5.3. Routes of Cuprizone Administration

Two manners of cuprizone administration are used in animal experiments, both involving the oral route: 1) ingestion of a diet containing cuprizone (Merkler et al., 2009), which has been employed in our study, and 2) administration via gavage (Zhen et al., 2017). These two administration ways lead to similar demyelination patterns; they do not require sophisticated equipment or surgical procedures, which makes the drug administration easily reproducible. It would be exciting to compare the oral route with parenteral administration. However, the parenteral cuprizone administration has not been performed so far.

6. Conclusions

Our results indicate that cuprizone’s electrophysiological and glial cell immunoreactivity effects are attenuated by physical exercise. Exercise counteracted the cuprizone-induced changes on CSD propagation and Iba1-containing cells but not on MBP and APC-containing ones. Our data demonstrated that regular physical exercise is associated with a potential neuroprotective effect, which raises the possibility of benefiting patients with demyelinating disorders via this non-pharmacological, low-cost intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the financial support from the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq- grant no. 30.5998/2018-8). The Keizo Asami Immunopathology Laboratory (LIKA) granted us the use of its microscopy facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Accioly NE, Guedes RCA. (2020) Topical cortical application of ovarian hormones and modulation of brain electrical activity: analysis of spreading depression in well-nourished and malnourished female rats, Nutritional Neuroscience, 23:11, 887-895. [CrossRef]

- Araújo AO, Figueira-de-Oliveira ML, Noya AGAFC, Oliveira e Silva VP, Carvalho JM, Vieira LD, Guedes RCA. (2023) Effect of neonatal melatonin administration on behavioral and brain electrophysiological and redox imbalance in rats. Frontiers in Neuroscience 17:1269609. [CrossRef]

- Arneth B (2024). Genes, Gene Loci, and Their Impacts on the Immune System in the Development of Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25:12906. [CrossRef]

- Barnett MH, Prineas JW (2004) Relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis: pathology of the newly forming lesion. Ann Neurol 55:458–468. [CrossRef]

- Batista-de-Oliveira M, Lopes AAC, Mendes-da-Silva RF, Guedes RCA (2012). Aging-dependent brain electrophysiological effects in rats after distinct lactation conditions, and treadmill exercise: A spreading depression analysis. Exp. Gerontol. 47:452–457. [CrossRef]

- Black JE, Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Greenough WT (1990). Learning causes synaptogenesis, whereas motor activity causes angiogenesis in the cerebellar cortex of adult rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87: 5568-5572.

- Braz AF, Figueira de Oliveira ML, Costa DHS, Torres-Leal FL, Guedes RCA. (2023) Treadmill Exercise Reverses the Adverse Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Behavior and Cortical Spreading Depression in Young Rats. Brain Sciences 13, 1726. [CrossRef]

- Brown J, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Kempermann G, Van PH, Winkler J, Gage FH, Kuhn HG (2003). An environment that is enriched by physical activity stimulates hippocampal but not olfactory bulb neurogenesis. Europ. J. Neurosci. 17:2042-2046. [CrossRef]

- Carson M J (2002). Microglia as liaisons between the immune and central nervous systems: functional implications for multiple sclerosis. Glia 40, 218-31. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez VJ, Rubio-Zarapuz A, Belinchón-deMiguel P, Beltrán-Velasco AI, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. (2024). Impact of Physical Activity on Cellular Metabolism Across Both Neurodegenerative and General Neurological Conditions: A Narrative Review. Cells. 13:1940. [CrossRef]

- Cotman CW, Berchtold NC (2002). Exercise: a behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci., 25: 295-301.

- Cruise KE, Bucks RS, Loftus AM, Newton RU, Pegoraro R, Thomas MG (2011). Exercise and Parkinson’s: benefits for cognition and quality of life. Acta Neurol. Scand. 123, 13–19. [CrossRef]

- Denic A, Johnson AJ, Bieber AJ, Warrington AE, Rodriguez M, Pirko I (2011) The relevance of animal models in multiple sclerosis research. Pathophysiology 18:21–29. [CrossRef]

- Eldar R, Marincek C (2000). Physical activity for elderly persons with neurological impairment: a review, Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 32: 99-103.

- Fasczewski KS, Gill DL, Rothberger SM (2017). Physical activity motivation and benefits in people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil., 40:1-7. [CrossRef]

- Fragoso J, Jurema Santos GC, da Silva HT, Loizon E, Souza VON, Vidal H, Guedes RCA, Costa-Silva JH, Aragão RS, Pirola L, and Leandro CG (2020). Effects of maternal low-protein diet and spontaneous physical activity on the transcription of neurotrophic factors in the placenta and the brains of mothers and offspring rats. J. Devel. Origins Health Dis. [CrossRef]

- Gentile A, Musella A, De Vito F, Rizzo FR, Fresegna D, Bullitta S, Vanni V, Guadalupi L, Stampanoni Bassi M, Buttari F, Centonze D, Mandolesi G (2019). Immunomodulatory Effects of Exercise in Experimental Multiple Sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 10:2197. [CrossRef]

- Guedes RCA, Abadie-Guedes R (2019) Brain Aging and Electrophysiological Signaling: Revisiting the Spreading Depression Model. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 136, p.1-9. [CrossRef]

- Guedes RCA, Araújo MGR, Verçosa TC, Bion FM, Sá AL, Pereira Jr A, Abadie-Guedes R (2017). Evidence of an inverse correlation between serotonergic activity and spreading depression propagation in the rat cortex. Brain Res. 1672:29-34. [CrossRef]

- Guo LY, Lozinski B, Yong VW (2020). Exercise in multiple sclerosis and its models: Focus on the central nervous system outcomes. J Neurosci Res. 2020;98:509-523. [CrossRef]

- Heyn, P., Abreu, B.C., and Ottenbacher, K.J. (2004). The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: a meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 85, 1694–1704. [CrossRef]

- Hugues N, Pellegrino C, Rivera C, Berton E, Pin-Barre C, Laurin J (2021). Is High-Intensity Interval Training Suitable to Promote Neuroplasticity and Cognitive Functions after Stroke? Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22:3003. [CrossRef]

- Isaacs KR, Anderson BJ, Alcantara AA, Black JE, Greenough WT (1992). Exercise and the brain: angiogenesis in the adult rat cerebellum after vigorous physical activity and motor skill learning, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 12: 110-119. [CrossRef]

- Krityakiarana, W., Espinosa-Jeffrey, A., Ghiani, C.A., Zhao, P.M., Topaldjikian, N., Gomez-Pinilla, F., Yamaguchi, M., Kotchabhakdi, N., and de Vellis, J. (2010). Voluntary exercise increases oligodendrogenesis in spinal cord. Int. J. Neurosci. 120, 280–290. [CrossRef]

- Largo C, Ibarz JM, Herreras O (1997). Effects of the gliotoxin fluorocitrate on spreading depression and glial membrane potential in rat brain in situ. J Neurophysiol. 78:295-307. [CrossRef]

- Latimer CS, Searcy JL, Bridges MT, Brewer LD, Popovic J, Blalock EM, Landfield PW, Thibault O, Porter NM (2011). Reversal of Glial and Neurovascular Markers of Unhealthy Brain Aging by Exercise in Middle-Aged Female Mice. PLoS ONE 6 pp.1-8 e26812. [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen M, Strong AJ (2017). ‘Spreading depression of Leão’ and its emerging relevance to acute brain injury in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 37(5):1553-1570. [CrossRef]

- Leão AAP (1944).Lefio AAP (1944) Spreading depression of activity in the cerebral cortex. J Neurophysiol 7:359-390.

- Leo H, Kipp M (2022). Remyelination in Multiple Sclerosis: Findings in the Cuprizone Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 16093. [CrossRef]

- Lima CB, Soares GSF, Vitor SM, Andrade-da-Costa BLS, Castellano B, Guedes RCA (2014). Spreading depression features and Iba1 immunoreactivity in the cerebral cortex of developing rats submitted to treadmill exercise after treatment with monosodium glutamate. Int. J. Devl Neurosci. 33 98–105. [CrossRef]

- Mandolesi G, Bullitta S, Fresegna D, De Vito F, Rizzo FR, Musella A, Guadalupi L, Vanni V. Bassi MS, Buttari F, Viscomi MT, Centonze D, Gentile A (2019). Voluntary running wheel attenuates motor deterioration and brain damage in cuprizone-induced demyelination. Neurobiol Dis. 129:102-117. [CrossRef]

- Matsushima GK, Morell P (2001) The neurotoxicant, cuprizone, as a model to study demyelination and remyelination in the central nervous system. Brain Pathol 11:107–116. [CrossRef]

- Mendes-da-Silva RF, Cunha-Lopes AA, Bandim-da-Silva ME, Cavalcanti GA, Rodrigues ARO, Andrade-da-Costa BLS, Guedes RCA (2014). Prooxidant versus antioxidant brain action of ascorbic acid in well-nourished and malnourished rats as a function of dose: a cortical spreading depression and malondialdehyde analysis. Neuropharmacology, 86:155-160 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Merkler D, Klinker F, Jürgens T, Glaser R, Paulus W, Brinkmann BG, Sereda M, Guedes RCA, Stadelmann-Nessler, C., Brück W, Liebetanz D (2009). Propagation of spreading depression inversely correlates with cortical myelin content. Annals Neurol. 66:355-365. [CrossRef]

- Moloney E, Mashayekhi A, Sharma S, Kontogiannis V, Ansaripour A, Brownlee W, Paling D, Javanbakht M (2024). Comparative efficacy and tolerability of rituximab vs. other monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of relapsing multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized trials. Front. Neurol. 15:1479476. [CrossRef]

- Morais A, Liu T-T, Qin T, Sadhegian H, Ay I, Yagmur D, Mendes da Silva R, Chung D, Simon B, Guedes RCA, Chen S-P, Wang S-J, Yen J-C, Ayata C. (2020). Vagus nerve stimulation inhibits cortical spreading depression exclusively via central mechanisms. Pain 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Nguemeni C, McDonald MW, Jeffers MS, Livingston-Thomas J, Lagace D, Corbett D (2018). Short- and Long-term Exposure to Low and High Dose Running Produce Differential Effects on Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Neuroscience 369 202–211. [CrossRef]

- Ochi H (2019). Sports and Physical Exercise in Multiple Sclerosis. Brain Nerve. 71:143-152. [CrossRef]

- Ozmerdivenli R, Bulut S, Bayar H, Karacabey K, Ciloglu F, Peker I, Tan U. (2005). Effects of exercise on visual evoked potentials. Int J Neurosci., 115:1043-1050. [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Querejeta; M. Sáenz-Cuesta; M. Munõz-Culla; D. Otaegui (2017). Models for Studying Myelination, Demyelination and Remyelination. Neuromol Med. [CrossRef]

- Patro N, Naik AA, Patro IK (2019). Developmental Changes in Oligodendrocyte Genesis, Myelination, and Associated Behavioral Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Intra-generational Protein Malnutrition. Molecular Neurobiol. 56:595–610. [CrossRef]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (1998). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 4th ed. Academic Press, New York.

- Pereira-Iglesias M, Maldonado-Teixido J, Melero A, Piriz J, Galea E, Ransohoff RM, Sierra A (2025). Microglia as hunters or gatherers of brain synapses. Nature Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Rocha-de-Melo, AP, Cavalcanti, JB, Barros, AS, Guedes, RCA. Manipulation of rat litter size during suckling influences cortical spreading depression after weaning and at adulthood. Nutr. Neurosci. 9:155-160 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Swain RA, Harris AB, Wiener EC, Dutka MV, Morris HD, Theien BE, Konda S, Engberg K, Lauterbur PC, Greenough WT (2003). Prolonged exercise induces angiogenesis and increases cerebral blood volume in primary motor cortex of the rat. Neuroscience, 117: 1037-1046. [CrossRef]

- Skripuletz T, Gudi V, Hackstette D, Stangel M (2011) De- and remyelination in the CNS white and grey matter induced by cuprizone: the old, the new, and the unexpected. Histol Histopathol 26:1585–1597. [CrossRef]

- Smith AD, Zigmond MJ (2003). Can the brain be protected through exercise? Lessons from an animal model of parkinsonism, Exp. Neurol., 184: 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. (2021). Animal models of multiple sclerosis. Current Protocols, 1, e185. [CrossRef]

- Tagge I, O’Connor A, Chaudhary P, Pollaro J, Berlow Y, Chalupsky M, et al. (2016) SpatioTemporal Patterns of Demyelination and Remyelination in the Cuprizone Mouse Model. PLoS ONE 11(4): e0152480. [CrossRef]

- Tatsumi K, Okuda H, Morita-Takemura S, Tanaka T, Isonishi A, Shinjo T, Terada Y and Wanaka A (2016) Voluntary Exercise Induces Astrocytic Structural Plasticity in the Globus Pallidus. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 10:165. [CrossRef]

- Torkildsen Ø, Brunborg LA, Myhr K-M, Bø L. (2013). The cuprizone model for demyelination. Acta Neurol Scand., 117: 72–76. [CrossRef]

- Van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH (1999). Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A, 96: 13427-13431.

- Won J, Alfini AJ, Weiss LR, Michelson CS, Callow DD, Ranadive SM, Gentili RJ, Smith JC (2019). Semantic Memory Activation After Acute Exercise in Healthy Older Adults. J Internat. Neuropsychol. Soc. 25:557–568. [CrossRef]

- Xavier S, Younesi S, Sominsky L and Spencer SJ (2023) Inhibiting microglia exacerbates the early effects of cuprizone in males in a rat model of multiple sclerosis, with no effect in females. Front. Neurol. 14:989132. [CrossRef]

- Zanotto T, Galperin I, Kumar DP, Mirelman A, Yehezkyahu S, Regev K, Karni A, Schmitz-Hübsch T, Paul F, Lynch SG, Akinwuntan AE, He J, Troen BR, Devos H, Hausdorff JM, Sosnoff JJ (2024). Effects of a 6-Week Treadmill Training With and Without Virtual Reality on Frailty in People With Multiple Sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2025 106:187-194. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zhang P, Shen X, Tian S, Wu Y, Zhu Y, Jia J, Wu J, Hu H (2013). Early Exercise Protects the Blood-Brain Barrier from Ischemic Brain Injury via the Regulation of MMP-9 and Occludin in Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 14: 11096-11112. [CrossRef]

- Zhen W, Liu A, Lu J, Zhang W, Tattersall D, Wang J (2017). An Alternative Cuprizone-Induced Demyelination and Remyelination Mouse Model. ASN Neuro,1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).