Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

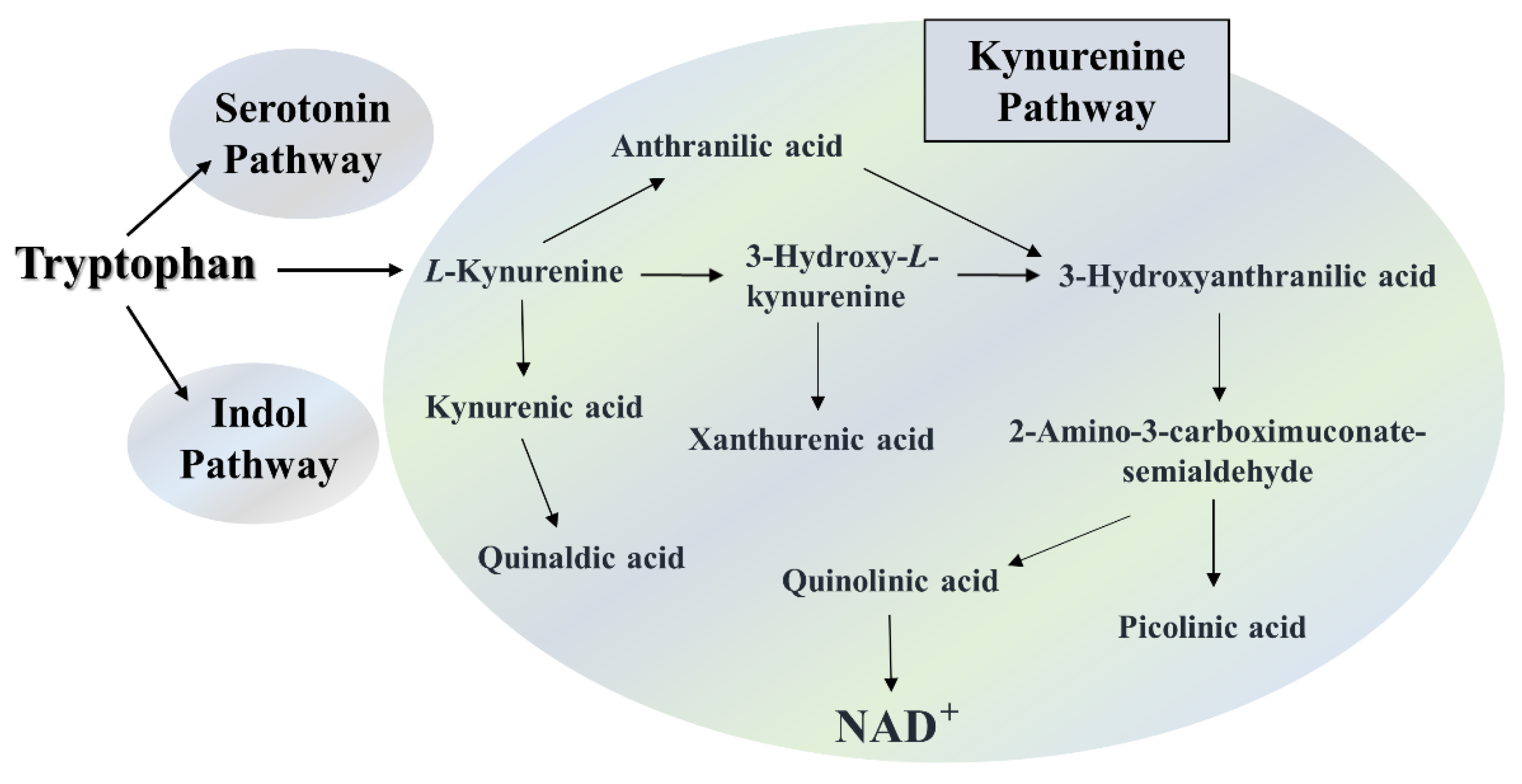

1. Introduction

2. Results

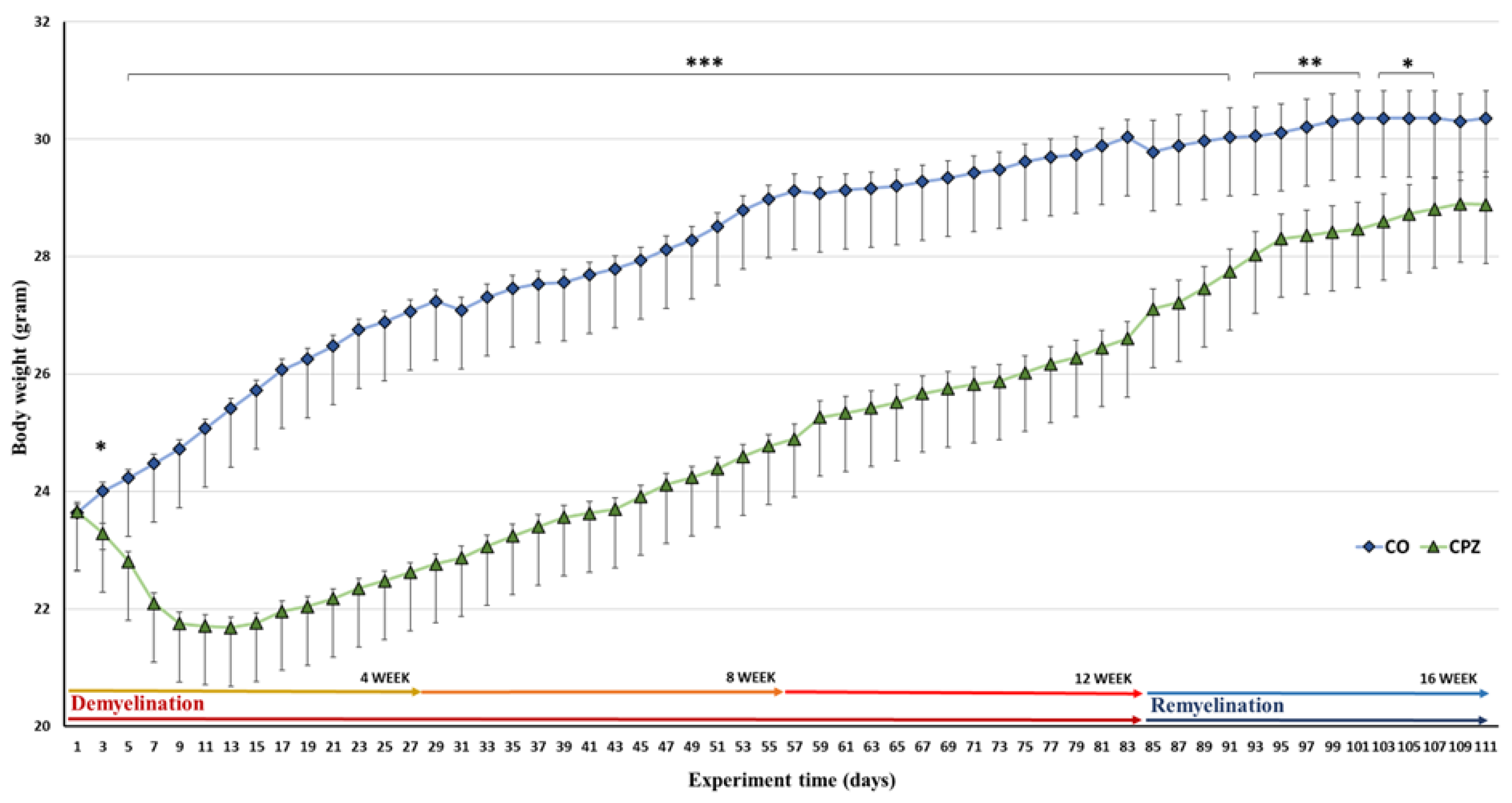

2.1. Investigation of Animals’ Body Weight

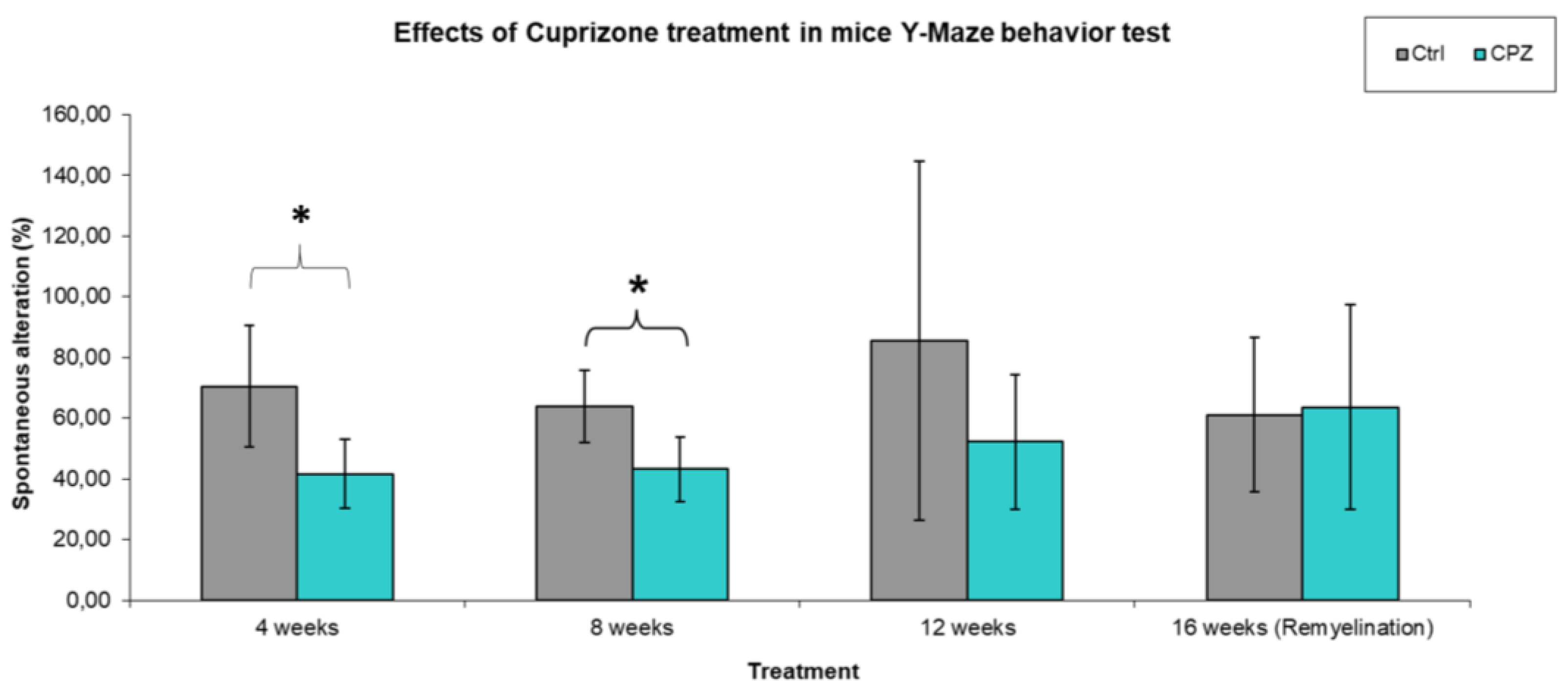

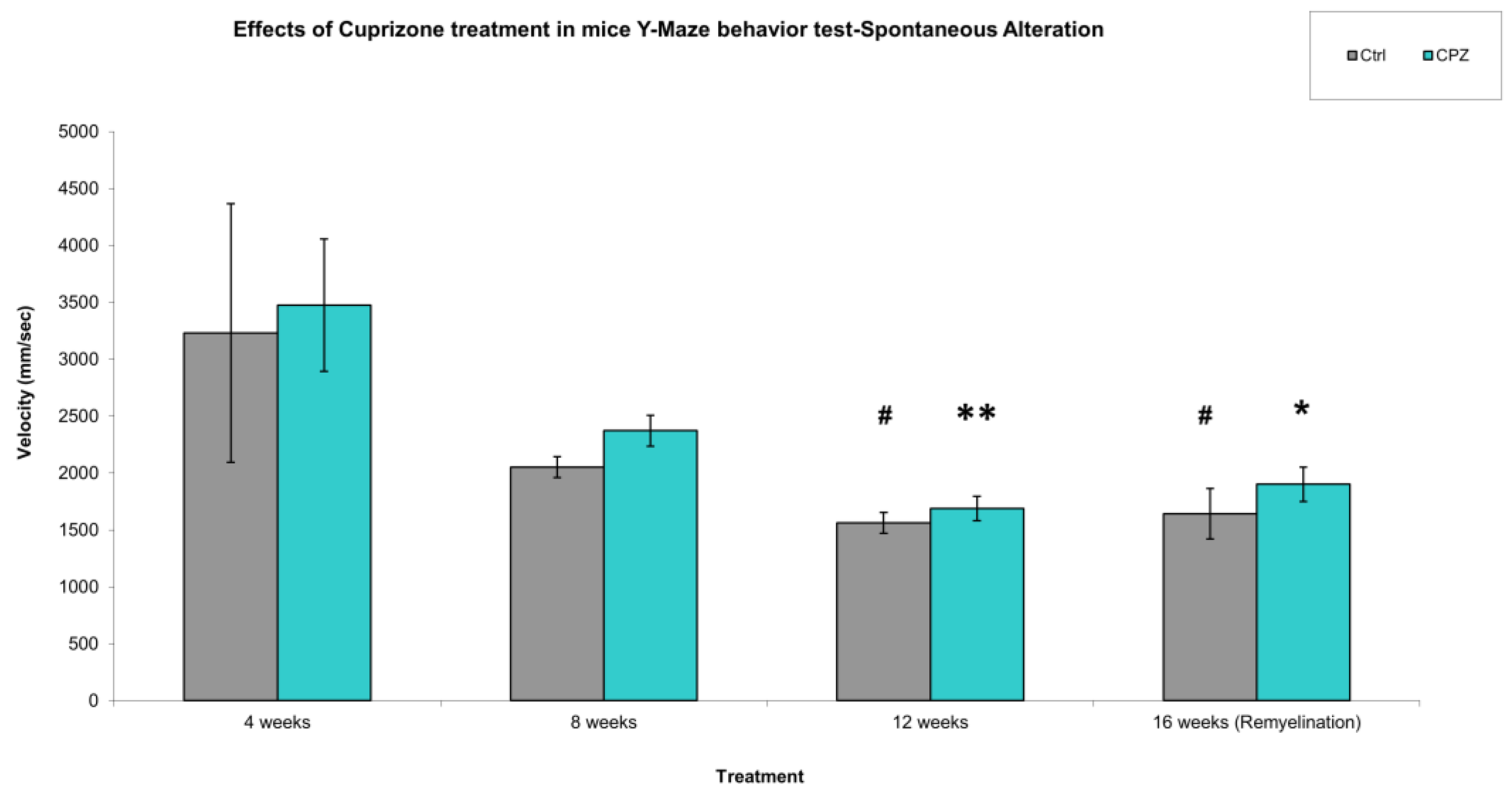

2.2. Behavioral Test

2.2.1. Spontaneous Alteration

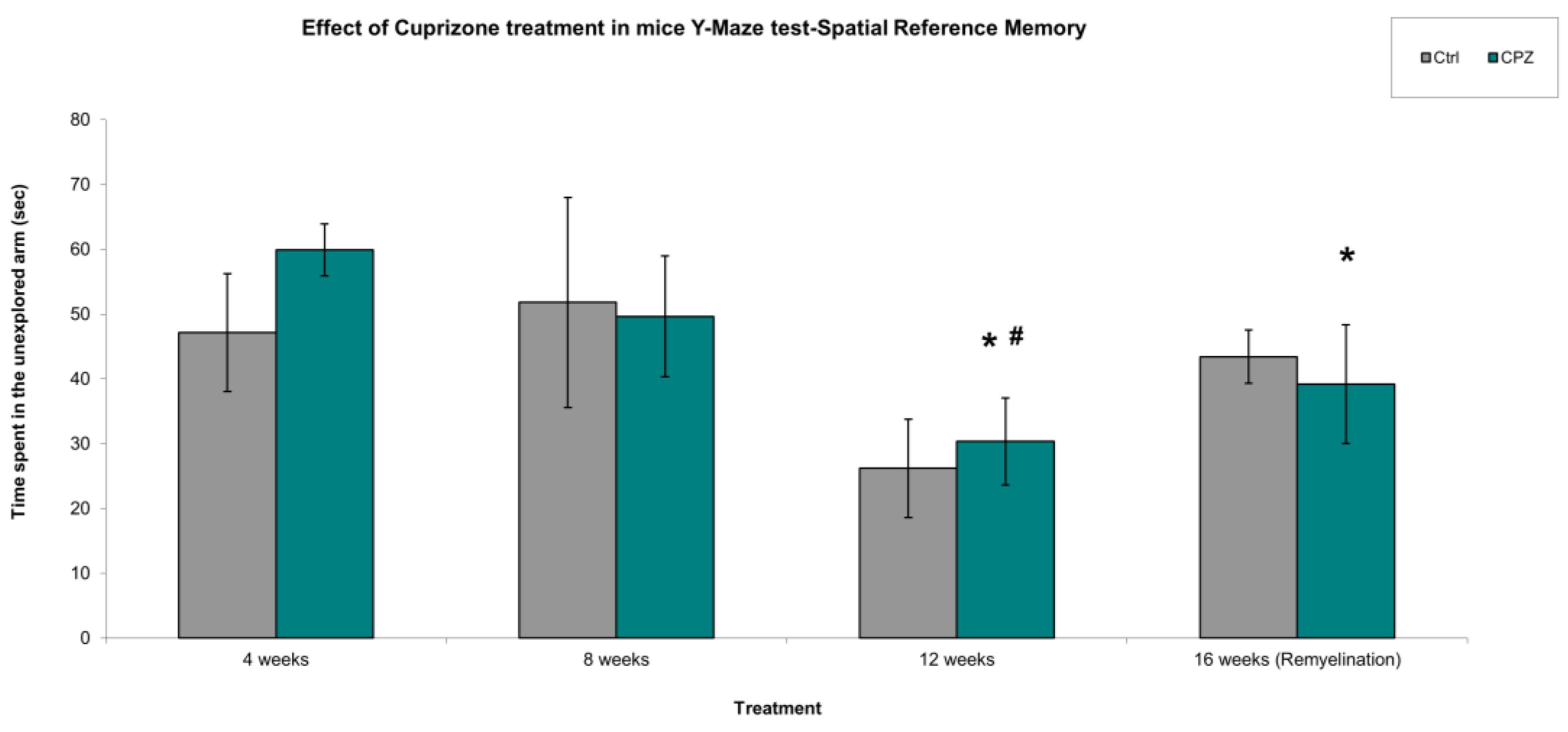

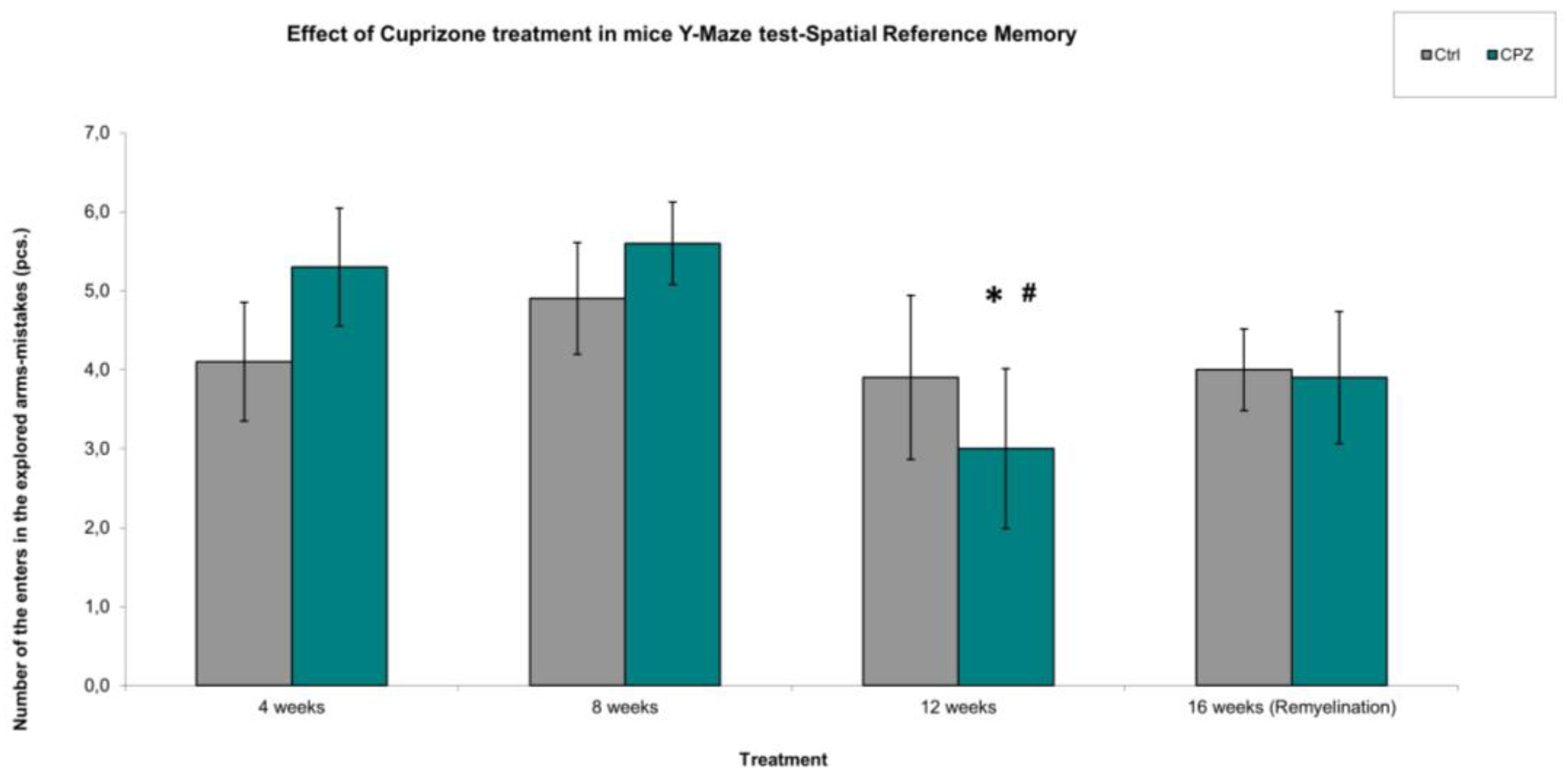

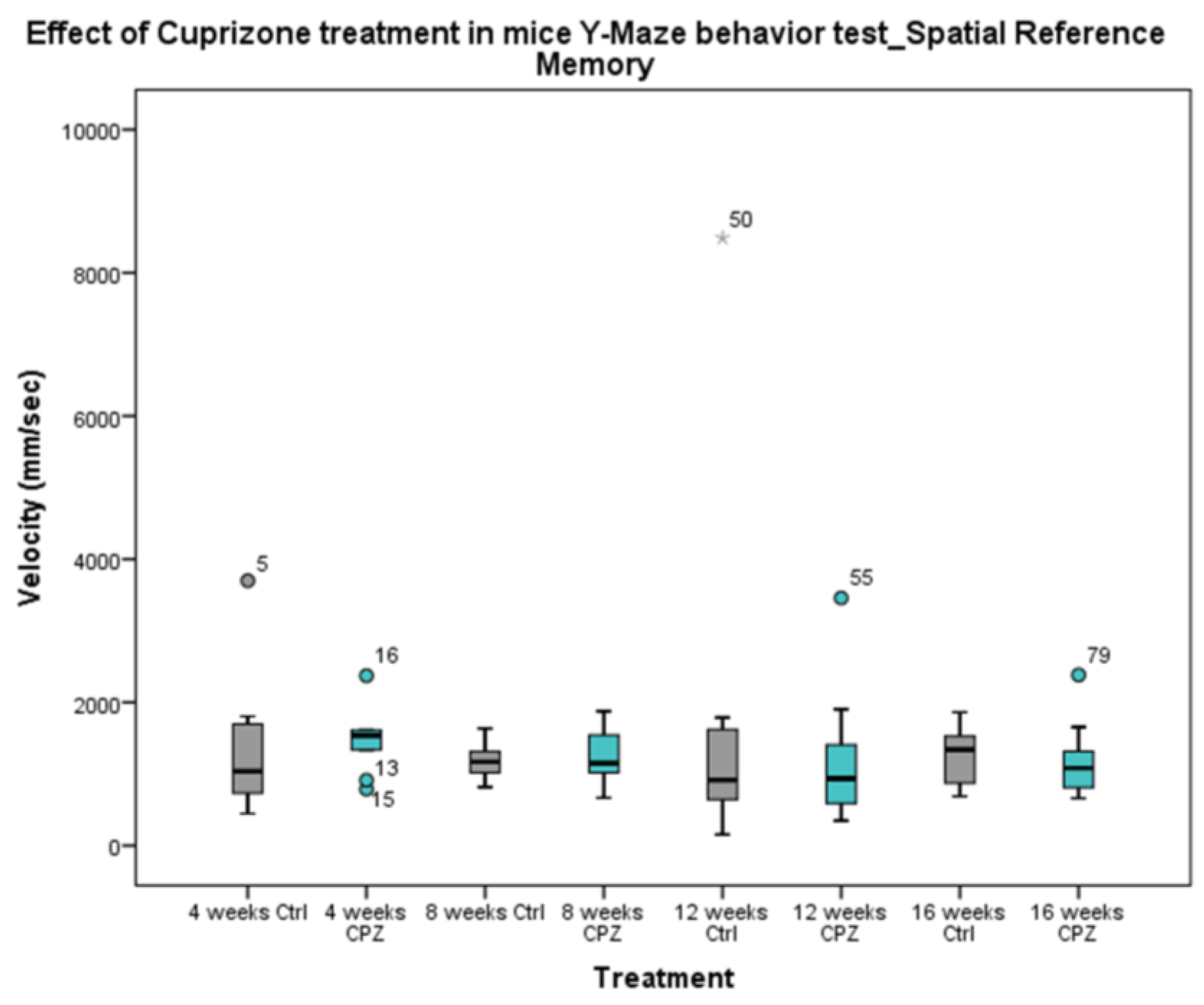

2.2.2. Spatial Reference Memory

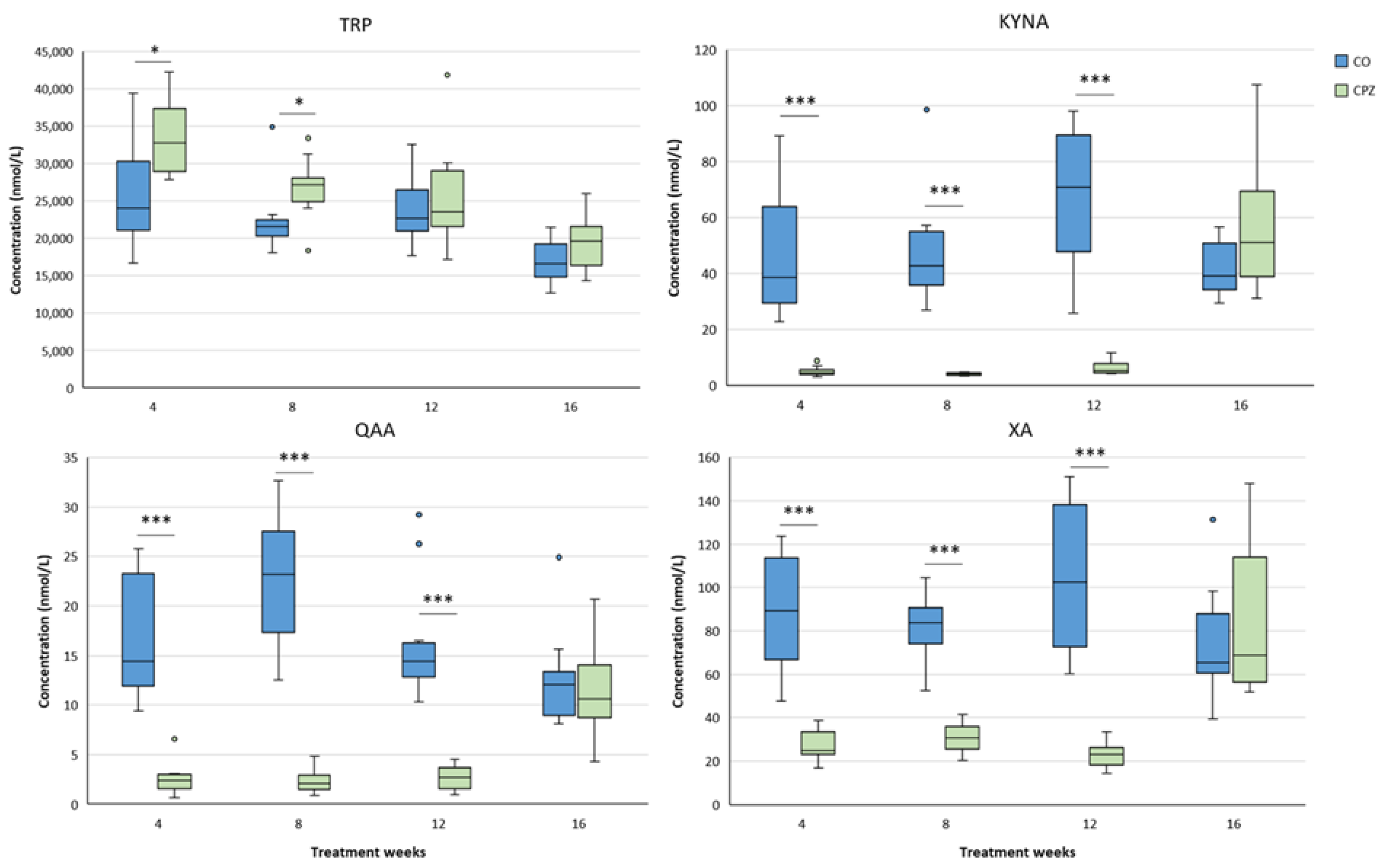

2.3. Bioanalytical Measurement of Tryptophan Metabolites

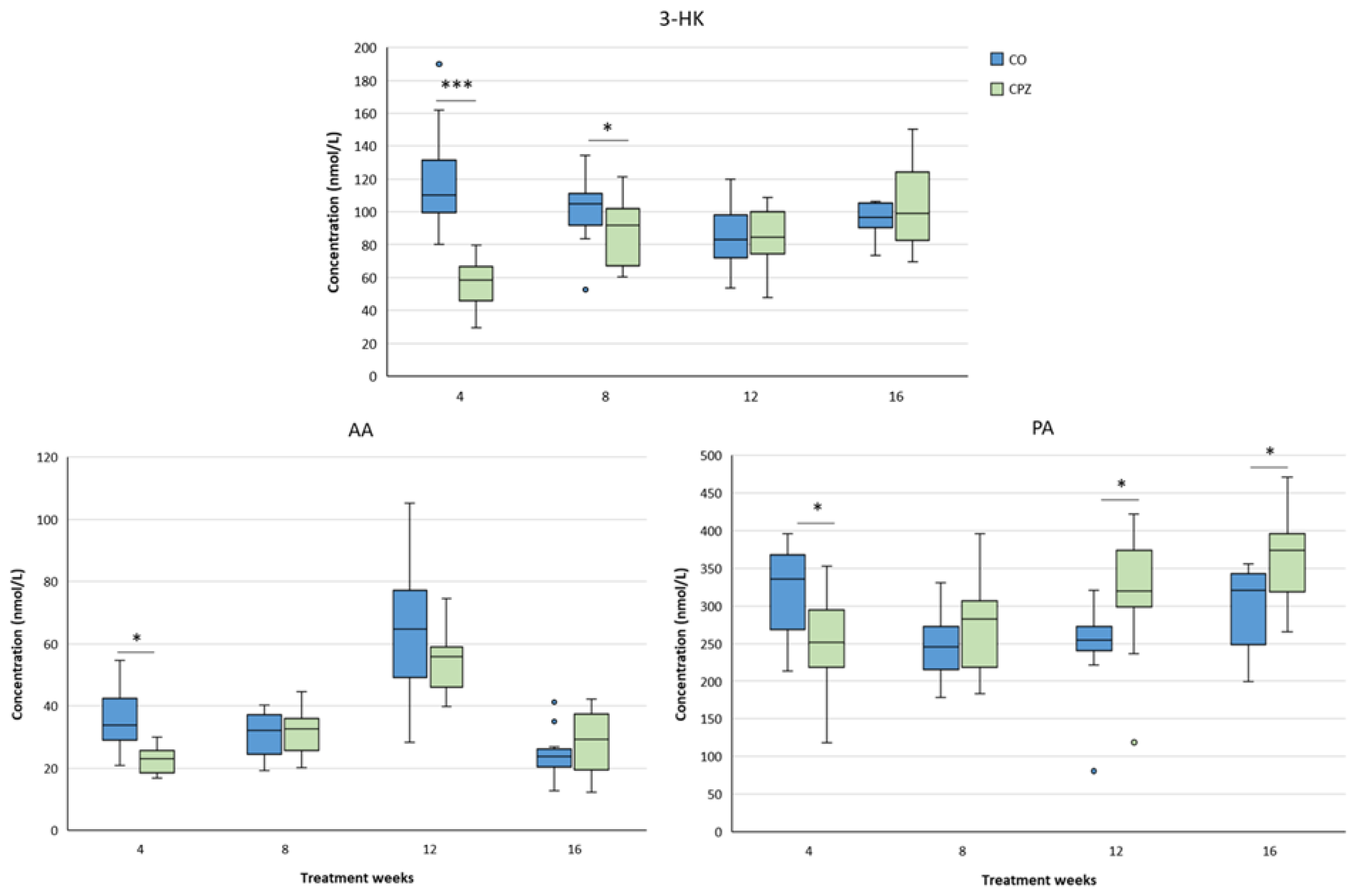

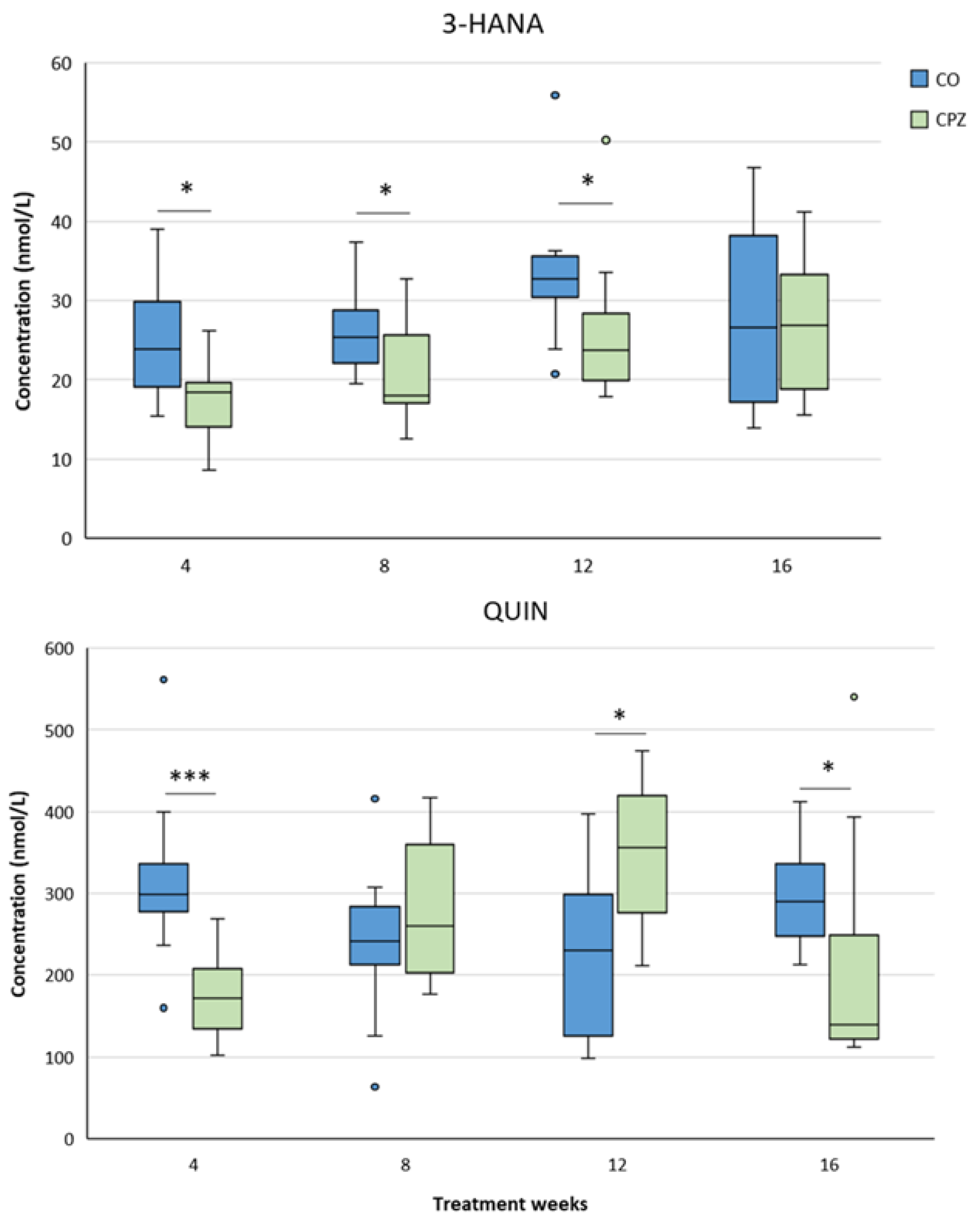

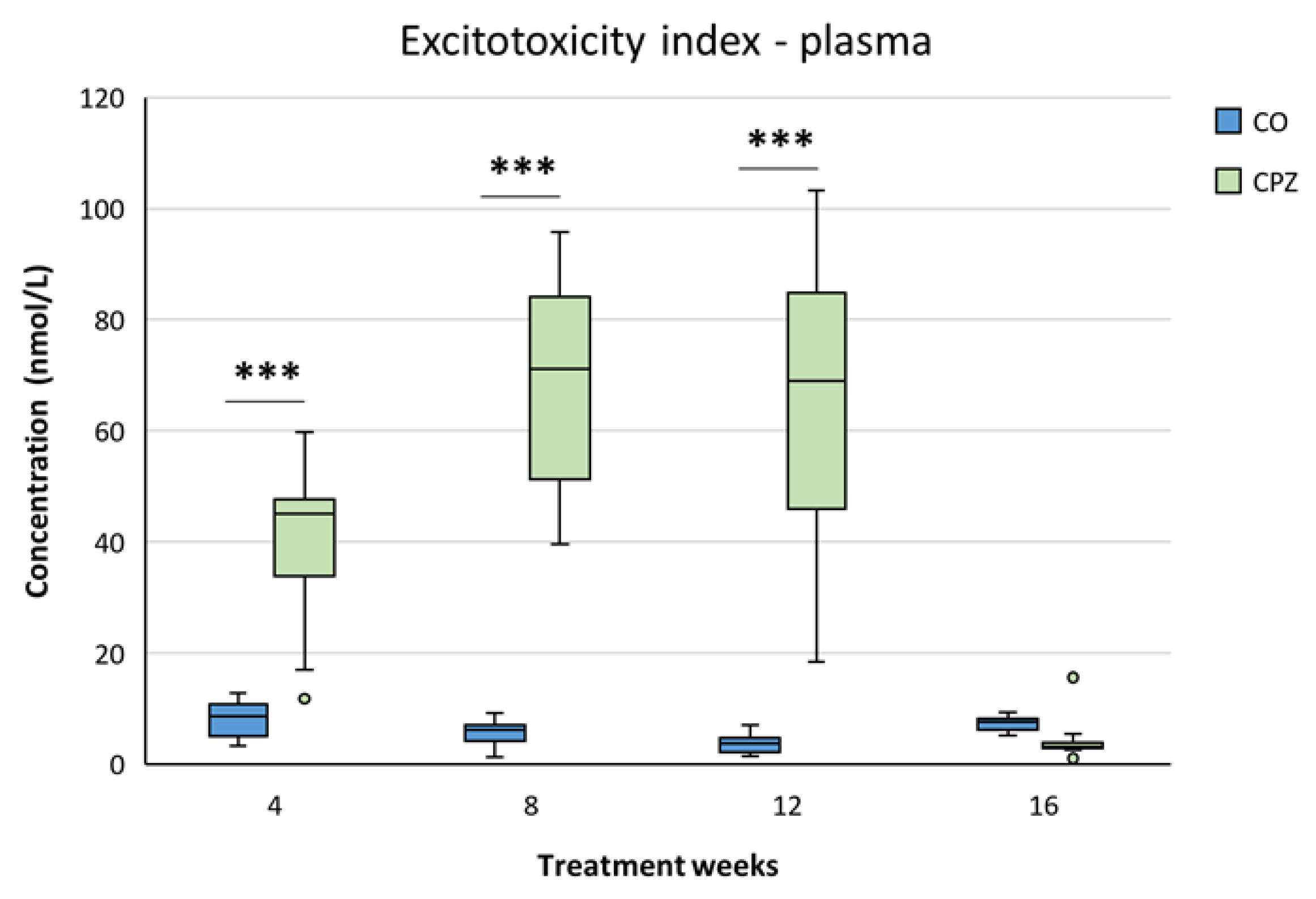

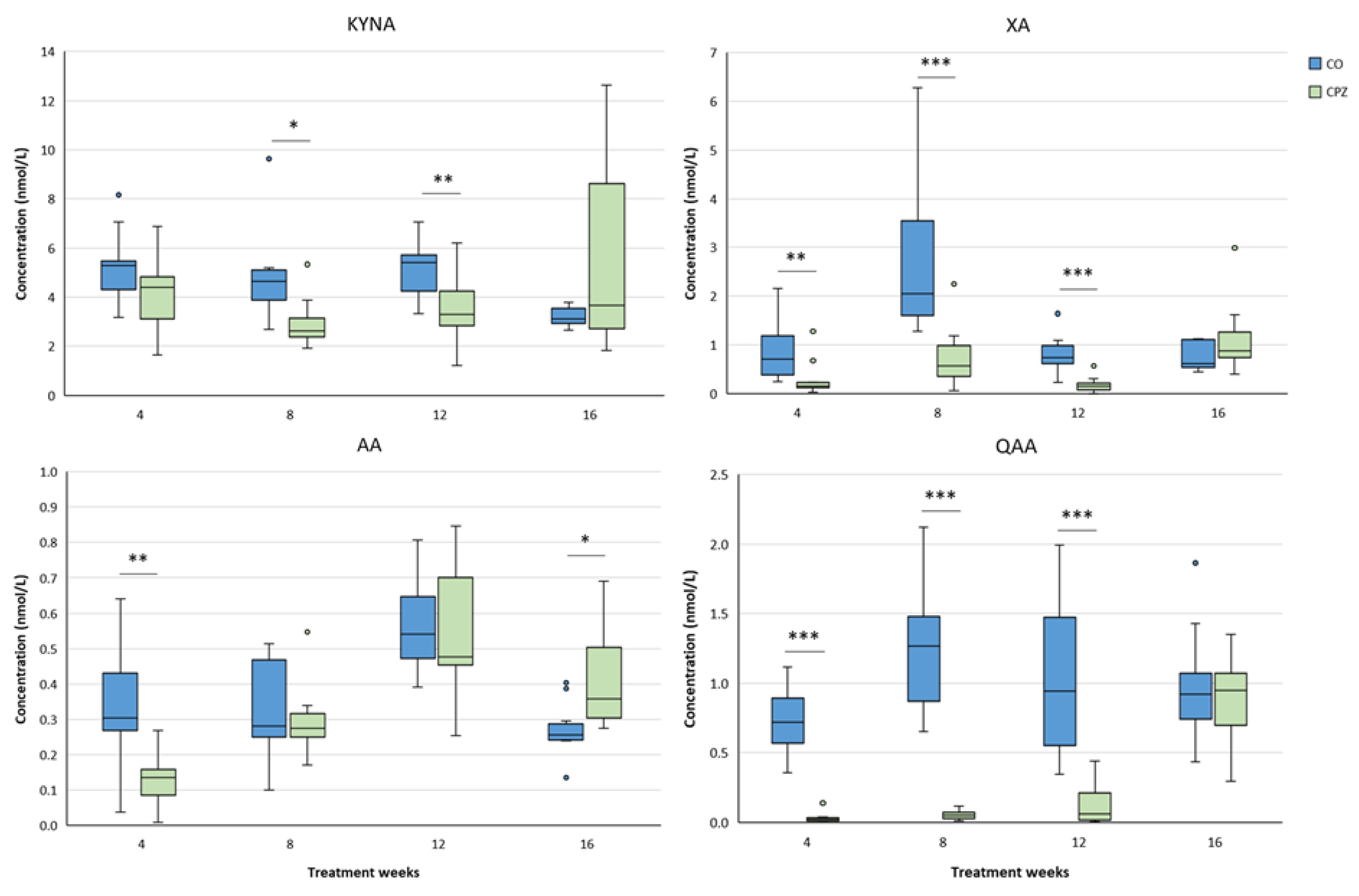

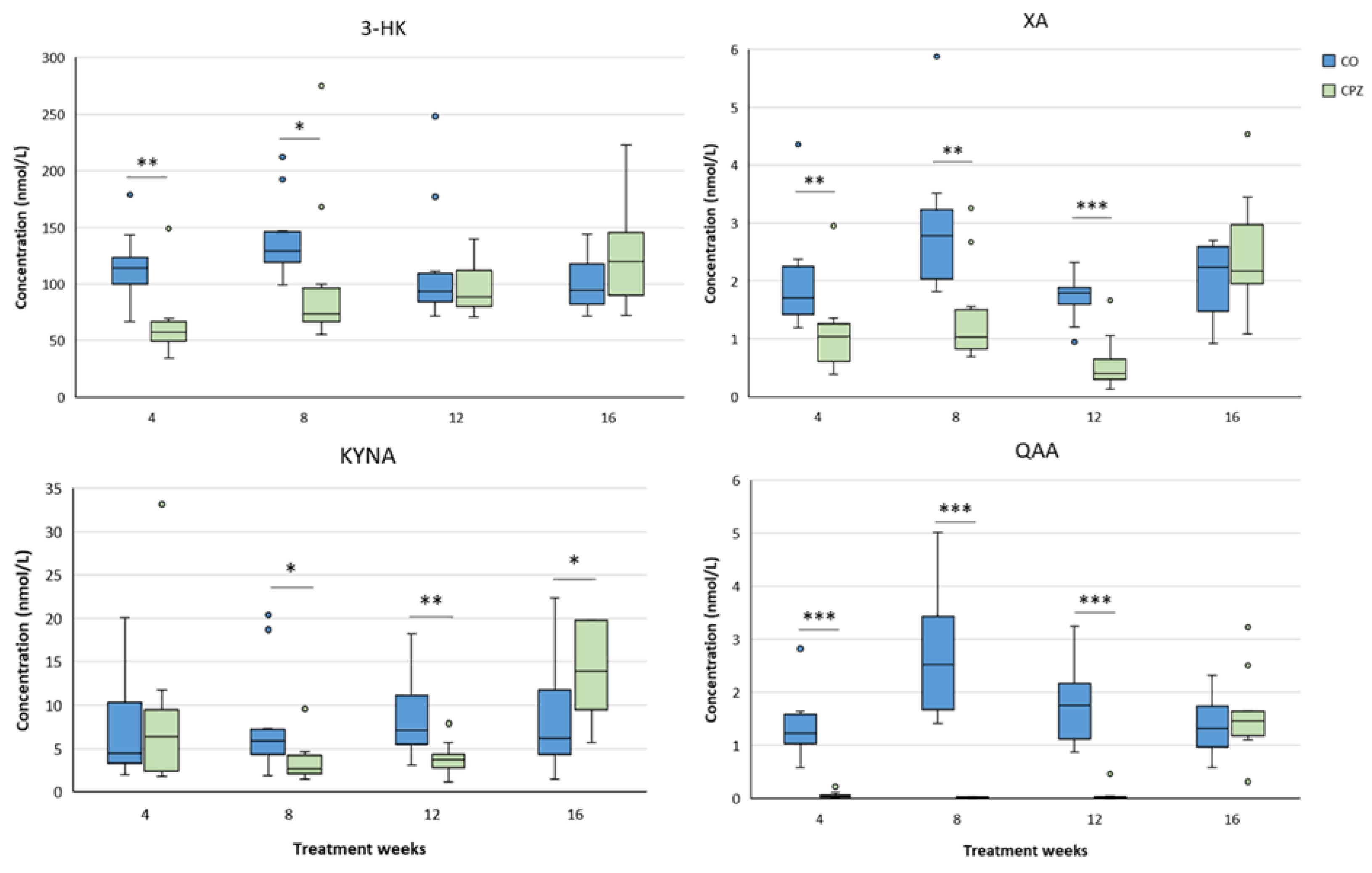

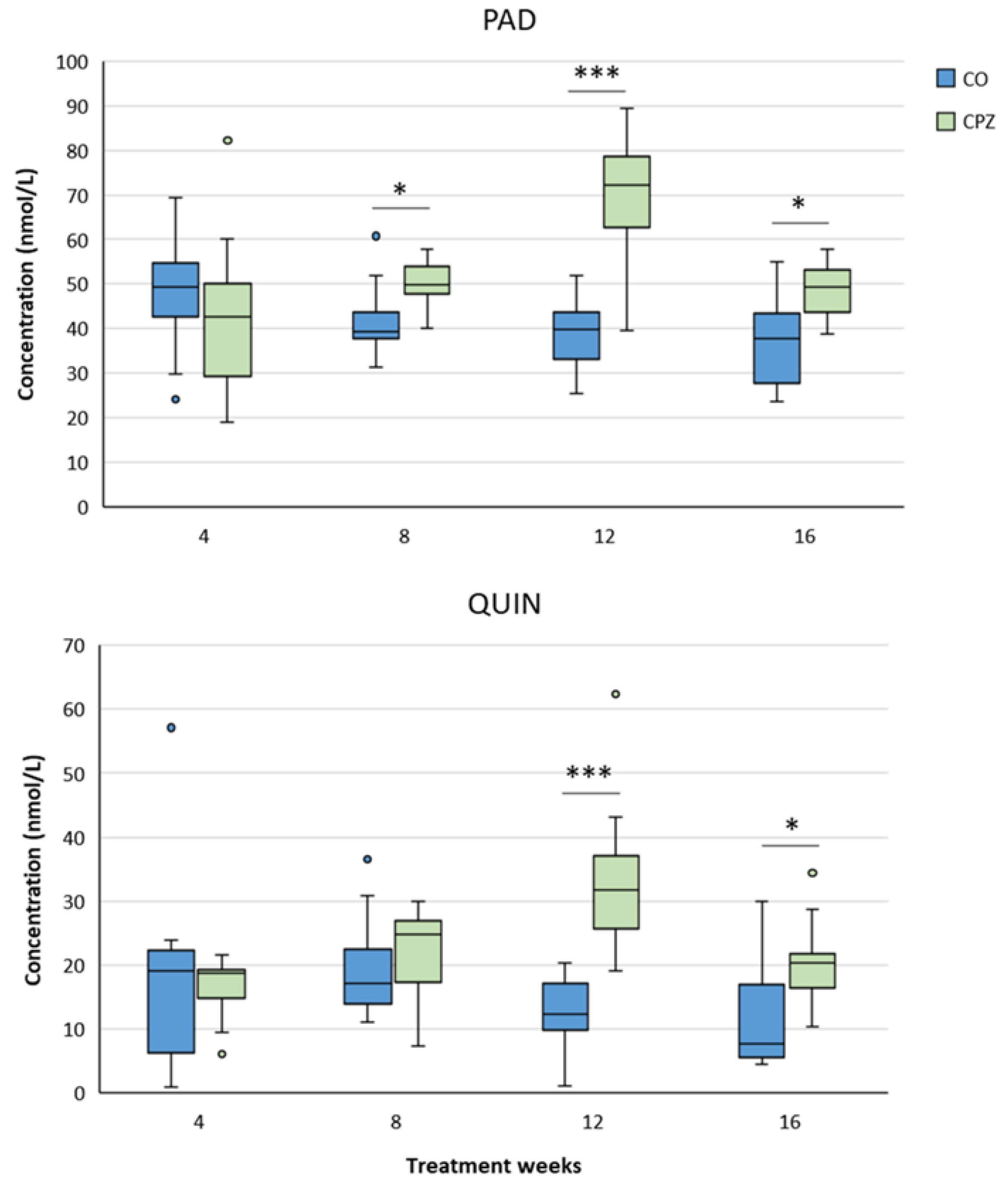

2.3.1. Plasma

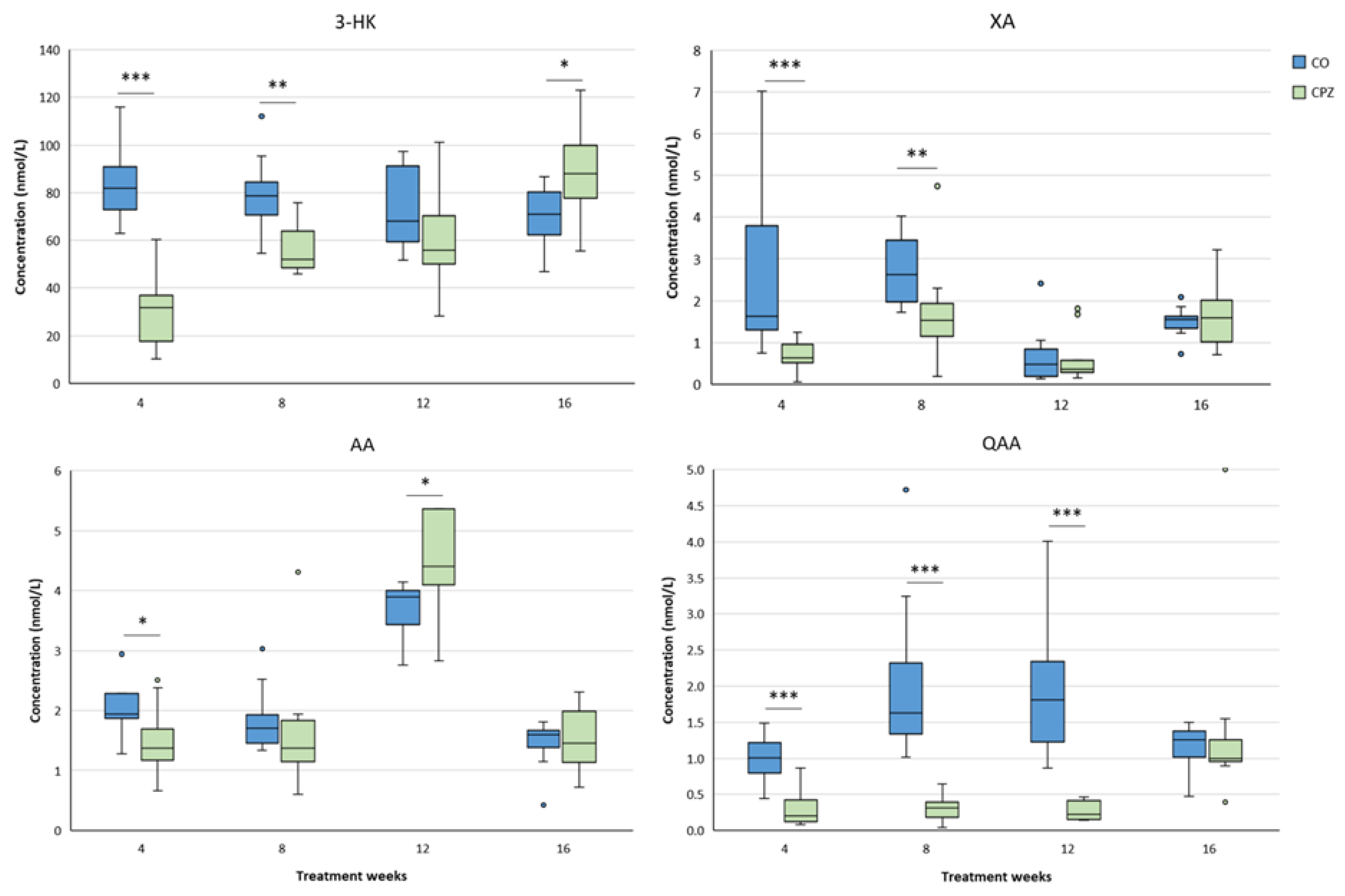

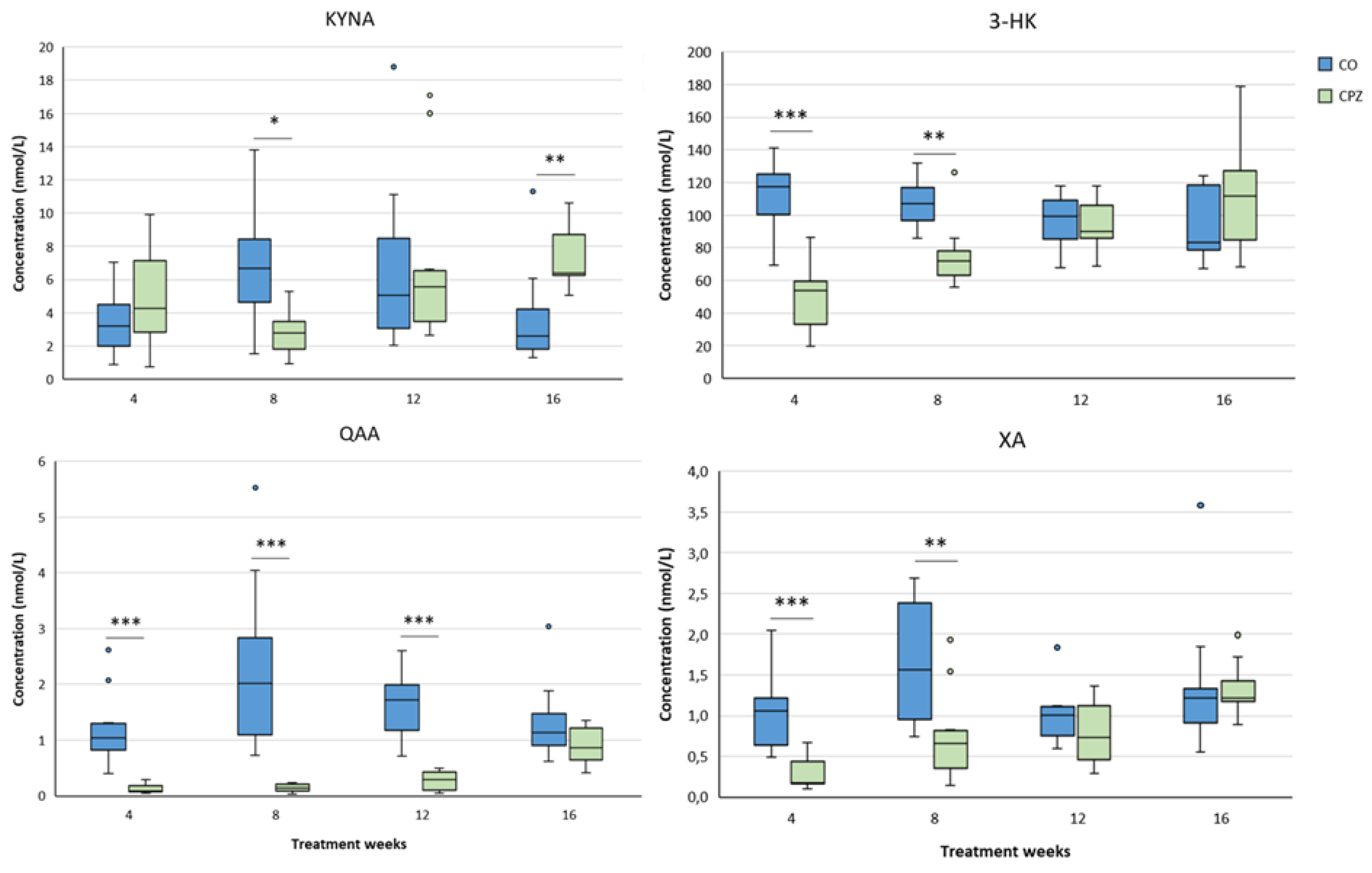

2.3.2. Striatum

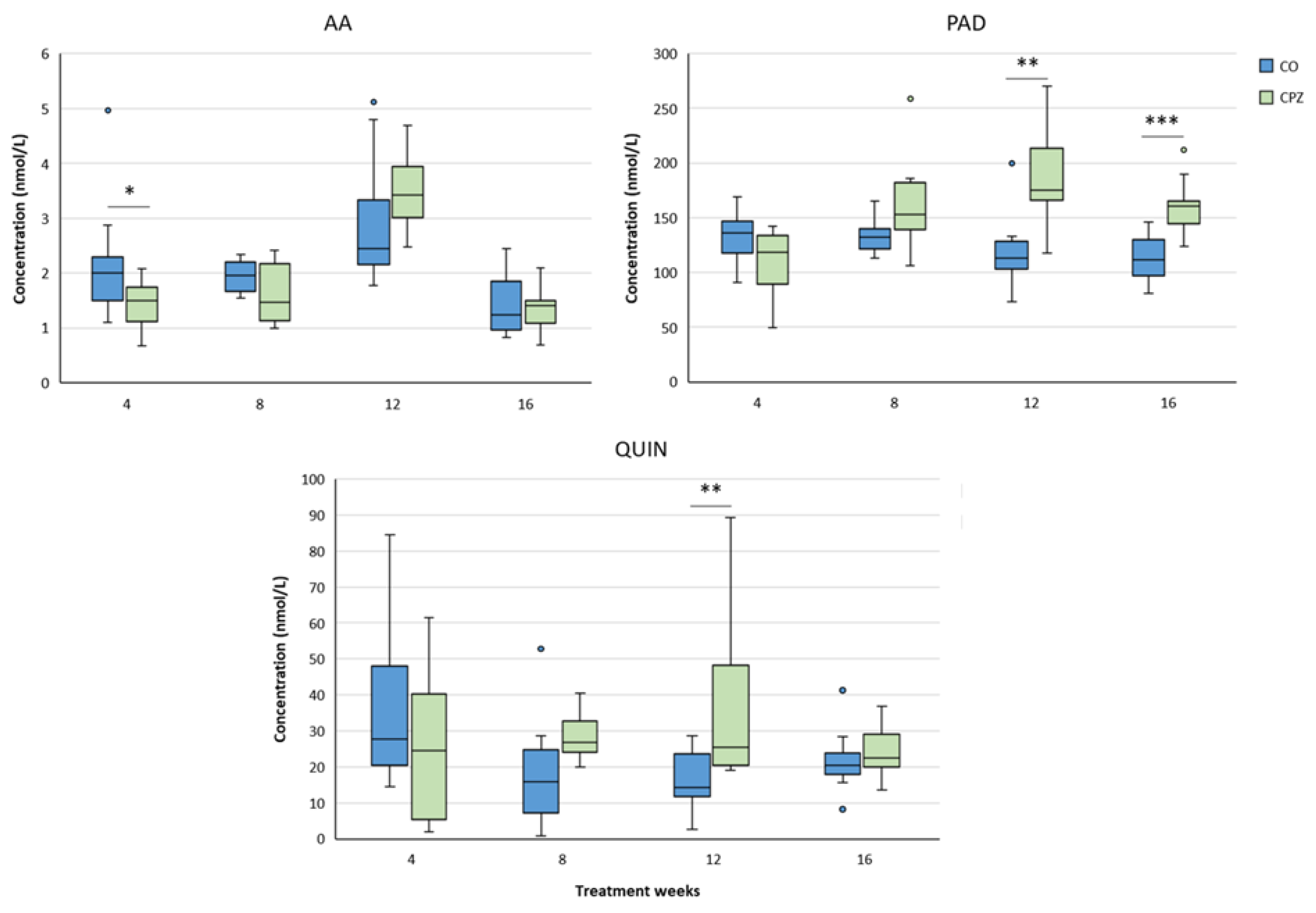

2.3.3. Cortex

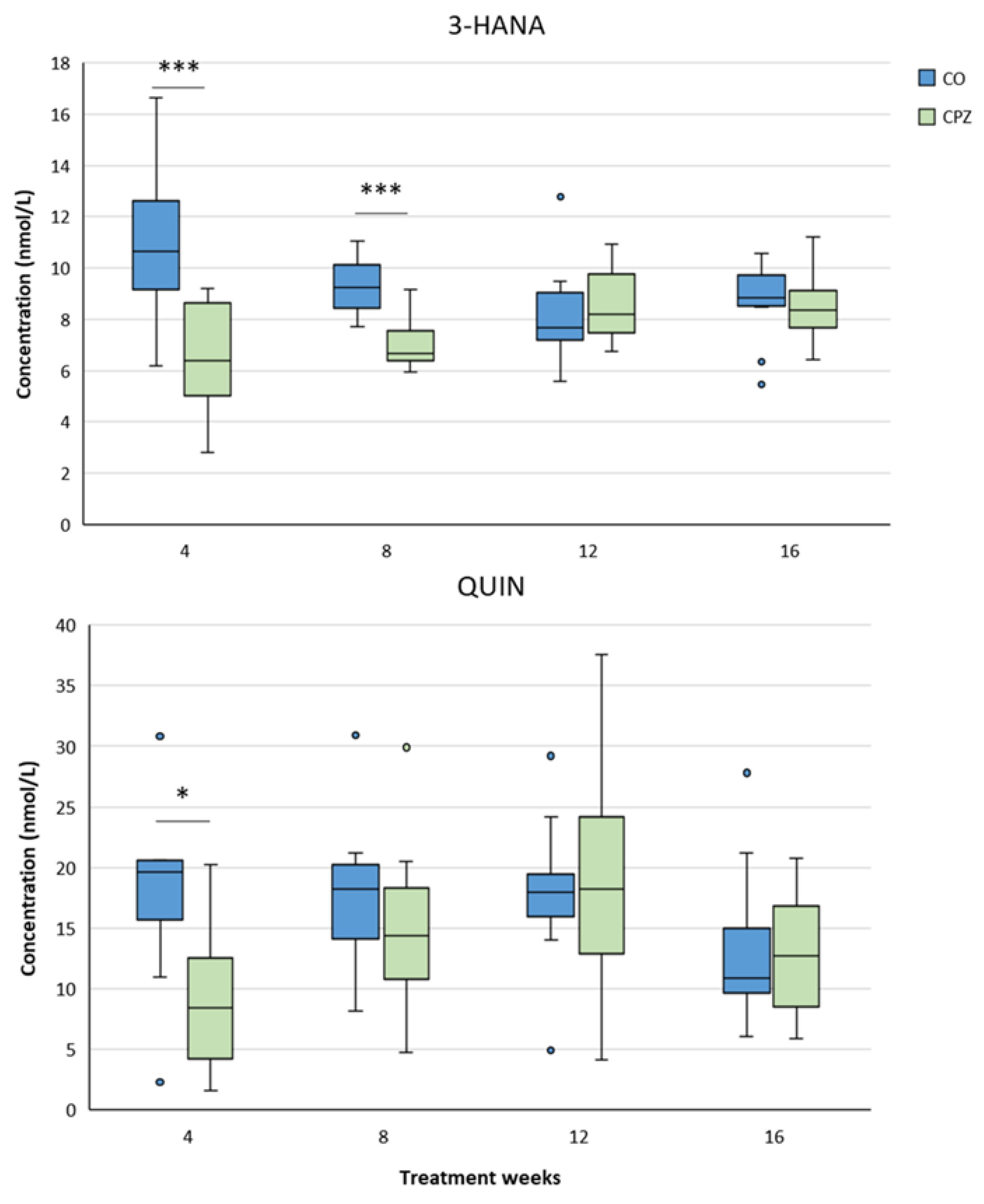

2.3.4. Hippocampus

2.3.5. Brainstem

2.3.6. Cerebellum

3. Discussion

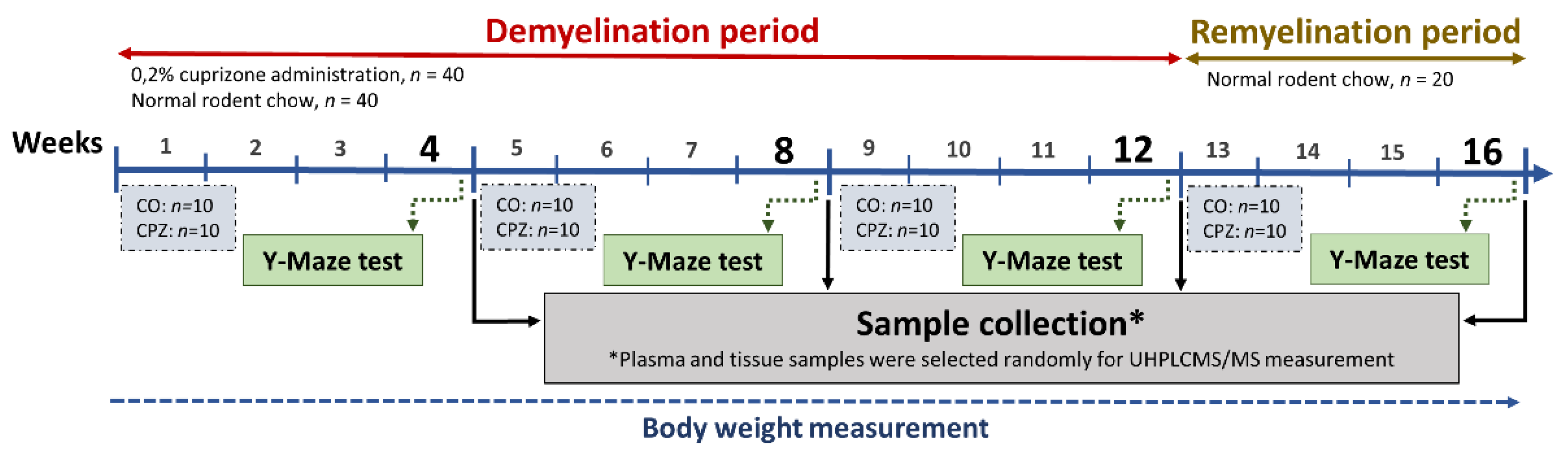

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Experiments and Sample Collection

4.2. Behavioral Investigation

4.3. Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC–MS/MS) Measurement

4.4. Excitotoxicity Index

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Declaration of conflicting interests

Abbreviations

| AA | Anthranilic acid |

| AMPA | amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| CO | Control |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CPZ | Cuprizone |

| 3-HANA | 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid |

| 3-HK | 3-hydroxy-L-kynurenine |

| KP | Kynurenine pathway |

| KYN | Kynurenine |

| KYNA | Kynurenic acid |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| NAD+ | Nicotineamide adenine dinucleotide |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartate |

| PA | Picolinic acid |

| PAD | Derivatized picolinic acid |

| PPMS | Primary progressive multiple sclerosis |

| RRMS | Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis |

| SPMS | Secondary progressive multiple sclerosis |

| TRP | Tryptophan |

| XA | Xanthurenic acid |

| QAA | Quinaldic acid |

| QUIN | Quinolinic acid |

References

- Walton C, King R, Rechtman L, Kaye W, Leray E, Marrie RA, et al. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Mult Scler 2020;26:1816–21. [CrossRef]

- Moles L, Egimendia A, Osorio-Querejeta I, Iparraguirre L, Alberro A, Suárez J, et al. Gut Microbiota Changes in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis and Cuprizone Mice Models. ACS Chem Neurosci 2021;12:893–905. [CrossRef]

- Woo MS, Engler JB, Friese MA. The neuropathobiology of multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2024;25:493–513. [CrossRef]

- Cagol A, Schaedelin S, Barakovic M, Benkert P, Todea R-A, Rahmanzadeh R, et al. Association of Brain Atrophy With Disease Progression Independent of Relapse Activity in Patients With Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2022:e221025. [CrossRef]

- Frischer JM, Weigand SD, Guo Y, Kale N, Parisi JE, Pirko I, et al. Clinical and Pathological Insights into the Dynamic Nature of the White Matter Multiple Sclerosis Plaque. Ann Neurol 2015;78:710–21. [CrossRef]

- Lubetzki C, Zalc B, Williams A, Stadelmann C, Stankoff B. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis: from basic science to clinical translation. The Lancet Neurology 2020;19:678–88. [CrossRef]

- Reich DS, Lucchinetti CF, Calabresi PA. Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2018;378:169–80. [CrossRef]

- McGinley MP, Goldschmidt CH, Rae-Grant AD. Diagnosis and Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis: A Review. JAMA 2021;325:765–79. [CrossRef]

- Brochet B, Clavelou P, Defer G, De Seze J, Louapre C, Magnin E, et al. Cognitive Impairment in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: Effect of Disease Duration, Age, and Progressive Phenotype. Brain Sci 2022;12:183. [CrossRef]

- Tan LSY, Francis HM, Lim CK. Exploring the roles of tryptophan metabolism in MS beyond neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration: A paradigm shift to neuropsychiatric symptoms. Brain Behav Immun Health 2021;12:100201. [CrossRef]

- Morrow SA. Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis: Past, Present, and Future. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2024;34:469–79. [CrossRef]

- Deloire M, Salort E, Bonnet M, Arimone Y, Boudineau M, Amieva H, et al. Cognitive impairment as marker of diffuse brain abnormalities in early relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005;76:519–26. [CrossRef]

- Brochet B, Ruet A. Cognitive Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis With Regards to Disease Duration and Clinical Phenotypes. Front Neurol 2019;10:261. [CrossRef]

- Meca-Lallana V, Gascón-Giménez F, Ginestal-López RC, Higueras Y, Téllez-Lara N, Carreres-Polo J, et al. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis and monitoring. Neurol Sci 2021;42:5183–93. [CrossRef]

- Denney DR, Lynch SG, Parmenter BA, Horne N. Cognitive impairment in relapsing and primary progressive multiple sclerosis: mostly a matter of speed. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2004;10:948–56. [CrossRef]

- Ruet A, Deloire M, Charré-Morin J, Hamel D, Brochet B. Cognitive impairment differs between primary progressive and relapsing-remitting MS. Neurology 2013;80:1501–8. [CrossRef]

- Praet J, Guglielmetti C, Berneman Z, Van der Linden A, Ponsaerts P. Cellular and molecular neuropathology of the cuprizone mouse model: clinical relevance for multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014;47:485–505. [CrossRef]

- Sen MK, Mahns DA, Coorssen JR, Shortland PJ. Behavioural phenotypes in the cuprizone model of central nervous system demyelination. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2019;107:23–46. [CrossRef]

- Kawabata R, Yamamoto S, Kamimura N, Yao I, Yoshikawa K, Koga K. Cuprizone-induced demyelination provokes abnormal intrinsic properties and excitatory synaptic transmission in the male mouse anterior cingulate cortex. Neuropharmacology 2025;271:110403. [CrossRef]

- Nomura T, Bando Y, Nakazawa H, Kanemoto S, Yoshida S. Pathological changes in mice with long term cuprizone administration. Neurochemistry International 2019;126:229–38. [CrossRef]

- Kipp M, Nyamoya S, Hochstrasser T, Amor S. Multiple sclerosis animal models: a clinical and histopathological perspective. Brain Pathology 2017;27:123–37. [CrossRef]

- Gudi V, Gingele S, Skripuletz T, Stangel M. Glial response during cuprizone-induced de- and remyelination in the CNS: lessons learned. Front Cell Neurosci 2014;8. [CrossRef]

- Lovelace MD, Varney B, Sundaram G, Franco NF, Ng ML, Pai S, et al. Current Evidence for a Role of the Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Immunol 2016;7. [CrossRef]

- Bansi J, Koliamitra C, Bloch W, Joisten N, Schenk A, Watson M, et al. Persons with secondary progressive and relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis reveal different responses of tryptophan metabolism to acute endurance exercise and training. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2018;314:101–5. [CrossRef]

- Vécsei L, Szalárdy L, Fülöp F, Toldi J. Kynurenines in the CNS: recent advances and new questions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2013;12:64–82. [CrossRef]

- Davidson M, Rashidi N, Nurgali K, Apostolopoulos V. The Role of Tryptophan Metabolites in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:9968. [CrossRef]

- Dopkins N, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. The role of gut microbiome and associated metabolome in the regulation of neuroinflammation in multiple sclerosis and its implications in attenuating chronic inflammation in other inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Immunology 2018;154:178–85. [CrossRef]

- Gao J, Xu K, Liu H, Liu G, Bai M, Peng C, et al. Impact of the Gut Microbiota on Intestinal Immunity Mediated by Tryptophan Metabolism. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2018;8:13. [CrossRef]

- Sauma S, Casaccia P. Gut-brain communication in demyelinating disorders. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2020;62:92–101. [CrossRef]

- Badawy AA-B. Kynurenine pathway and human systems. Experimental Gerontology 2020;129:110770. [CrossRef]

- Rajda C, Majláth Z, Pukoli D, Vécsei L. Kynurenines and Multiple Sclerosis: The Dialogue between the Immune System and the Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci 2015;16:18270–82. [CrossRef]

- Biernacki T, Sandi D, Bencsik K, Vécsei L. Kynurenines in the Pathogenesis of Multiple Sclerosis: Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Rejdak K, Petzold A, Kocki T, Kurzepa J, Grieb P, Turski WA, et al. Astrocytic activation in relation to inflammatory markers during clinical exacerbation of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neural Transm 2007;114:1011. [CrossRef]

- Rejdak K, Bartosik-Psujek H, Dobosz B, Kocki T, Grieb P, Giovannoni G, et al. Decreased level of kynurenic acid in cerebrospinal fluid of relapsing-onset multiple sclerosis patients. Neuroscience Letters 2002;331:63–5. [CrossRef]

- Lim CK, Bilgin A, Lovejoy DB, Tan V, Bustamante S, Taylor BV, et al. Kynurenine pathway metabolomics predicts and provides mechanistic insight into multiple sclerosis progression. Sci Rep 2017;7. [CrossRef]

- Saraste M, Matilainen M, Rajda C, Galla Z, Sucksdorff M, Vécsei L, et al. Association between microglial activation and serum kynurenine pathway metabolites in multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2022:103667. [CrossRef]

- Polyák H, Cseh EK, Bohár Z, Rajda C, Zádori D, Klivényi P, et al. Cuprizone markedly decreases kynurenic acid levels in the rodent brain tissue and plasma. Heliyon 2021;7:e06124. [CrossRef]

- Polyák H, Galla Z, Nánási N, Cseh EK, Rajda C, Veres G, et al. The Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic System Is Suppressed in Cuprizone-Induced Model of Demyelination Simulating Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Biomedicines 2023;11:945. [CrossRef]

- Polyák H, Galla Z, Rajda C, Monostori P, Klivényi P, Vécsei L. Plasma and Visceral Organ Kynurenine Metabolites Correlate in the Multiple Sclerosis Cuprizone Animal Model. Int J Mol Sci 2025;26:976. [CrossRef]

- Tömösi F, Kecskeméti G, Cseh EK, Szabó E, Rajda C, Kormány R, et al. A validated UHPLC-MS method for tryptophan metabolites: Application in the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2020;185:113246. [CrossRef]

- Fathi M, Vakili K, Yaghoobpoor S, Tavasol A, Jazi K, Mohamadkhani A, et al. Dynamic changes in kynurenine pathway metabolites in multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Front Immunol 2022;13:1013784. [CrossRef]

- Negrotto L, Correale J. Amino Acid Catabolism in Multiple Sclerosis Affects Immune Homeostasis. The Journal of Immunology 2017;198:1900–9. [CrossRef]

- Aeinehband S, Brenner P, Ståhl S, Bhat M, Fidock MD, Khademi M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid kynurenines in multiple sclerosis; relation to disease course and neurocognitive symptoms. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2016;51:47–55. [CrossRef]

- Rajda C, Galla Z, Polyák H, Maróti Z, Babarczy K, Pukoli D, et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Chain Is Associated with Kynurenine Pathway Metabolite Changes in Multiple Sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21. [CrossRef]

- Kessler M, Terramani T, Lynch G, Baudry M. A glycine site associated with N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors: characterization and identification of a new class of antagonists. J Neurochem 1989;52:1319–28.

- Birch PJ, Grossman CJ, Hayes AG. Kynurenate and FG9041 have both competitive and non-competitive antagonist actions at excitatory amino acid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol 1988;151:313–5. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón R, Blanco-Ayala T, Ugalde-Muñiz P, Carrillo-Mora P, Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Silva-Adaya D, et al. On the antioxidant properties of kynurenic acid: Free radical scavenging activity and inhibition of oxidative stress. Neurotoxicology and Teratology 2011;33:538–47. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González A, Alvarez-Idaboy JR, Galano A. Free-radical scavenging by tryptophan and its metabolites through electron transfer based processes. J Mol Model 2015;21:213. [CrossRef]

- Goda K, Hamane Y, Kishimoto R, Ogishi Y. Radical scavenging properties of tryptophan metabolites. Estimation of their radical reactivity. Adv Exp Med Biol 1999;467:397–402. [CrossRef]

- Hartai Z, Klivenyi P, Janaky T, Penke B, Dux L, Vecsei L. Kynurenine metabolism in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2005;112:93–6. [CrossRef]

- Kepplinger B, Baran H, Kainz A, Ferraz-Leite H, Newcombe J, Kalina P. Age-related increase of kynurenic acid in human cerebrospinal fluid - IgG and beta2-microglobulin changes. Neurosignals 2005;14:126–35. [CrossRef]

- Andiné P, Lehmann A, Ellrén K, Wennberg E, Kjellmer I, Nielsen T, et al. The excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid administered after hypoxic-ischemia in neonatal rats offers neuroprotection. Neuroscience Letters 1988;90:208–12. [CrossRef]

- Atlas A, Franzen-Röhl E, Söderlund J, Jönsson EG, Samuelsson M, Schwieler L, et al. Sustained Elevation of Kynurenic Acid in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Encephalitis. Int J Tryptophan Res 2013;6:89–96. [CrossRef]

- Myint A-M, Kim YK, Verkerk R, Scharpé S, Steinbusch H, Leonard B. Kynurenine pathway in major depression: evidence of impaired neuroprotection. J Affect Disord 2007;98:143–51. [CrossRef]

- Kupjetz M, Wences Chirino TY, Joisten N, Zimmer P. Kynurenine pathway dysregulation as a mechanistic link between cognitive impairment and brain damage: Implications for multiple sclerosis. Brain Research 2024:149415. [CrossRef]

- González Esquivel D, Ramírez-Ortega D, Pineda B, Castro N, Ríos C, Pérez de la Cruz V. Kynurenine pathway metabolites and enzymes involved in redox reactions. Neuropharmacology 2017;112:331–45. [CrossRef]

- Baran H, Staniek K, Kepplinger B, Stur J, Draxler M, Nohl H. Kynurenines and the respiratory parameters on rat heart mitochondria. Life Sciences 2003;72:1103–15. [CrossRef]

- Badawy AA-B. Hypothesis kynurenic and quinolinic acids: The main players of the kynurenine pathway and opponents in inflammatory disease. Medical Hypotheses 2018;118:129–38. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka M, Spekker E, Szabó Á, Polyák H, Vécsei L. Modelling the neurodevelopmental pathogenesis in neuropsychiatric disorders. Bioactive kynurenines and their analogues as neuroprotective agents—in celebration of 80th birthday of Professor Peter Riederer. J Neural Transm 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chobot V, Hadacek F, Weckwerth W, Kubicova L. Iron chelation and redox chemistry of anthranilic acid and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid: A comparison of two structurally related kynurenine pathway metabolites to obtain improved insights into their potential role in neurological disease development. J Organomet Chem 2015;782:103–10. [CrossRef]

- Darlington LG, Forrest CM, Mackay GM, Smith RA, Smith AJ, Stoy N, et al. On the biological importance of the 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid: Anthranilic acid ratio. International Journal of Tryptophan Research 2010;3:51–9. [CrossRef]

- Lima VLA, Dias F, Nunes RD, Pereira LO, Santos TSR, Chiarini LB, et al. The Antioxidant Role of Xanthurenic Acid in the Aedes aegypti Midgut during Digestion of a Blood Meal. PLoS One 2012;7:e38349. [CrossRef]

- Murakami K, Ito M, Yoshino M. Xanthurenic acid inhibits metal ion-induced lipid peroxidation and protects NADP-isocitrate dehydrogenase from oxidative inactivation. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2001;47:306–10. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Ortega D, Ramiro-Salazar A, González-Esquivel D, Ríos C, Pineda B, Pérez de la Cruz V. 3-Hydroxykynurenine and 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Enhance the Toxicity Induced by Copper in Rat Astrocyte Culture. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:2371895. [CrossRef]

- Fazio F, Lionetto L, Curto M, Iacovelli L, Copeland CS, Neale SA, et al. Cinnabarinic acid and xanthurenic acid: Two kynurenine metabolites that interact with metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology 2017;112:365–72. [CrossRef]

- Neale SA, Copeland CS, Uebele VN, Thomson FJ, Salt TE. Modulation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by the kynurenine pathway member xanthurenic acid and other vglut inhibitors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013;38:1060–7. [CrossRef]

- Bosco MC, Rapisarda A, Massazza S, Melillo G, Young H, Varesio L. The tryptophan catabolite picolinic acid selectively induces the chemokines macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha and -1 beta in macrophages. J Immunol 2000;164:3283–91. [CrossRef]

- Melillo G, Cox GW, Biragyn A, Sheffler LA, Varesio L. Regulation of nitric-oxide synthase mRNA expression by interferon-gamma and picolinic acid. J Biol Chem 1994;269:8128–33.

- Melillo G, Cox GW, Radzioch D, Varesio L. Picolinic acid, a catabolite of L-tryptophan, is a costimulus for the induction of reactive nitrogen intermediate production in murine macrophages. J Immunol 1993;150:4031–40.

- Guillemin GJ, Kerr SJ, Smythe GA, Smith DG, Kapoor V, Armati PJ, et al. Kynurenine pathway metabolism in human astrocytes: a paradox for neuronal protection. J Neurochem 2001;78:842–53. [CrossRef]

- Grant RS, Coggan SE, Smythe GA. The Physiological Action of Picolinic Acid in the Human Brain. Int J Tryptophan Res 2009;2:71–9.

- Anderson JM, Hampton DW, Patani R, Pryce G, Crowther RA, Reynolds R, et al. Abnormally phosphorylated tau is associated with neuronal and axonal loss in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Brain 2008;131:1736–48. [CrossRef]

- Staats Pires A, Krishnamurthy S, Sharma S, Chow S, Klistorner S, Guillemin GJ, et al. Dysregulation of the Kynurenine Pathway in Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis and Its Correlations With Progressive Neurodegeneration. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2025;12:e200372. [CrossRef]

- Guillemin GJ. Quinolinic acid, the inescapable neurotoxin. FEBS J 2012;279:1356–65. [CrossRef]

- Sandi D, Fricska-Nagy Z, Bencsik K, Vécsei L. Neurodegeneration in Multiple Sclerosis: Symptoms of Silent Progression, Biomarkers and Neuroprotective Therapy—Kynurenines Are Important Players. Molecules 2021;26:3423. [CrossRef]

- Rios C, Santamaria A. Quinolinic acid is a potent lipid peroxidant in rat brain homogenates. Neurochem Res 1991;16:1139–43. [CrossRef]

- Pierozan P, Zamoner A, Krombauer Soska Â, Bristot Silvestrin R, Oliveira Loureiro S, Heimfarth L, et al. Acute intrastriatal administration of quinolinic acid provokes hyperphosphorylation of cytoskeletal intermediate filament proteins in astrocytes and neurons of rats. Experimental Neurology 2010;224:188–96. [CrossRef]

- Rahman A, Ting K, Cullen KM, Braidy N, Brew BJ, Guillemin GJ. The Excitotoxin Quinolinic Acid Induces Tau Phosphorylation in Human Neurons. PLoS One 2009;4:e6344. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Huitrón R, Ugalde Muñiz P, Pineda B, Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Ríos C, Pérez-de la Cruz V. Quinolinic Acid: An Endogenous Neurotoxin with Multiple Targets. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2013;2013:104024. [CrossRef]

- Brundin L, Sellgren CM, Lim CK, Grit J, Pålsson E, Landén M, et al. An enzyme in the kynurenine pathway that governs vulnerability to suicidal behavior by regulating excitotoxicity and neuroinflammation. Transl Psychiatry 2016;6:e865. [CrossRef]

- Capucciati A, Galliano M, Bubacco L, Zecca L, Casella L, Monzani E, et al. Neuronal Proteins as Targets of 3-Hydroxykynurenine: Implications in Neurodegenerative Diseases. ACS Chem Neurosci 2019;10:3731–9. [CrossRef]

- Okuda S, Nishiyama N, Saito H, Katsuki H. 3-Hydroxykynurenine, an Endogenous Oxidative Stress Generator, Causes Neuronal Cell Death with Apoptotic Features and Region Selectivity. Journal of Neurochemistry 1998;70:299–307. [CrossRef]

- Guidetti P, Schwarcz R. 3-Hydroxykynurenine potentiates quinolinate but not NMDA toxicity in the rat striatum. European Journal of Neuroscience 1999;11:3857–63. [CrossRef]

- Colín-González AL, Maya-López M, Pedraza-Chaverrí J, Ali SF, Chavarría A, Santamaría A. The Janus faces of 3-hydroxykynurenine: Dual redox modulatory activity and lack of neurotoxicity in the rat striatum. Brain Research 2014;1589:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Leipnitz G, Schumacher C, Dalcin KB, Scussiato K, Solano A, Funchal C, et al. In vitro evidence for an antioxidant role of 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid in the brain. Neurochemistry International 2007;50:83–94. [CrossRef]

- Okuda S, Nishiyama N, Saito H, Katsuki H. Hydrogen peroxide-mediated neuronal cell death induced by an endogenous neurotoxin, 3-hydroxykynurenine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:12553–8.

- Chiarugi A, Cozzi A, Ballerini C, Massacesi L, Moroni F. Kynurenine 3-mono-oxygenase activity and neurotoxic kynurenine metabolites increase in the spinal cord of rats with experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Neuroscience 2001;102:687–95. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Ocampo J, Ramírez-Ortega D, Vázquez Cervantes GI, Pineda B, Montes de Oca Balderas P, González-Esquivel D, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction related to cell damage induced by 3-hydroxykynurenine and 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid: Non-dependent-effect of early reactive oxygen species production. NeuroToxicology 2015;50:81–91. [CrossRef]

- Krause D, Suh H-S, Tarassishin L, Cui QL, Durafourt BA, Choi N, et al. The Tryptophan Metabolite 3-Hydroxyanthranilic Acid Plays Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Roles During Inflammation. Am J Pathol 2011;179:1360–72. [CrossRef]

- Lee W-S, Lee S-M, Kim M-K, Park S-G, Choi I-W, Choi I, et al. The tryptophan metabolite 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid suppresses T cell responses by inhibiting dendritic cell activation. International Immunopharmacology 2013;17:721–6. [CrossRef]

- Oxenkrug G, van der Hart M, Roeser J, Summergrad P. Anthranilic Acid: A Potential Biomarker and Treatment Target for Schizophrenia. Ann Psychiatry Ment Health 2016;4.

- Cathomas F, Guetter K, Seifritz E, Klaus F, Kaiser S. Quinolinic acid is associated with cognitive deficits in schizophrenia but not major depressive disorder. Sci Rep 2021;11:9992. [CrossRef]

- Musella A, Gentile A, Rizzo FR, De Vito F, Fresegna D, Bullitta S, et al. Interplay Between Age and Neuroinflammation in Multiple Sclerosis: Effects on Motor and Cognitive Functions. Front Aging Neurosci 2018;10:238. [CrossRef]

- Lechner-Scott J, Agland S, Allan M, Darby D, Diamond K, Merlo D, et al. Managing cognitive impairment and its impact in multiple sclerosis: An Australian multidisciplinary perspective. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2023;79:104952. [CrossRef]

- Benedict RHB, Amato MP, DeLuca J, Geurts JJG. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis: clinical management, MRI, and therapeutic avenues. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:860–71. [CrossRef]

- McNicholas N, O’Connell K, Yap SM, Killeen RP, Hutchinson M, McGuigan C. Cognitive dysfunction in early multiple sclerosis: a review. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine 2018;111:359–64. [CrossRef]

- Alharthi HM, Almurdi MM. Association between cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction among patients with multiple sclerosis: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Med Res 2023;28:110. [CrossRef]

- Margoni M, Preziosa P, Rocca MA, Filippi M. Depressive symptoms, anxiety and cognitive impairment: emerging evidence in multiple sclerosis. Transl Psychiatry 2023;13:264. [CrossRef]

- De Meo E, Portaccio E, Giorgio A, Ruano L, Goretti B, Niccolai C, et al. Identifying the Distinct Cognitive Phenotypes in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2021;78:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Geurts JJ, Barkhof F. Grey matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. The Lancet Neurology 2008;7:841–51. [CrossRef]

- Linker RA, Lee D-H, Ryan S, Van Dam AM, Conrad R, Bista P, et al. Fumaric acid esters exert neuroprotective effects in neuroinflammation via activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway. Brain 2011;134:678–92. [CrossRef]

- das Neves SP, Santos G, Barros C, Pereira DR, Ferreira R, Mota C, et al. Enhanced cognitive performance in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mice treated with dimethyl fumarate after the appearance of disease symptoms. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2020;340:577163. [CrossRef]

- Mandolesi G, Grasselli G, Musumeci G, Centonze D. Cognitive deficits in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: neuroinflammation and synaptic degeneration. Neurol Sci 2010;31:255–9. [CrossRef]

- Kopanitsa MV, Lehtimäki KK, Forsman M, Suhonen A, Koponen J, Piiponniemi TO, et al. Cognitive disturbances in the cuprizone model of multiple sclerosis. Genes, Brain and Behavior 2021;20:e12663. [CrossRef]

- Stone TW, Darlington LG. The kynurenine pathway as a therapeutic target in cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. Br J Pharmacol 2013;169:1211–27. [CrossRef]

- Prescott C, Weeks AM, Staley KJ, Partin KM. Kynurenic acid has a dual action on AMPA receptor responses. Neurosci Lett 2006;402:108–12. [CrossRef]

- Rózsa E, Robotka H, Vécsei L, Toldi J. The Janus-face kynurenic acid. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2008;115:1087–91. [CrossRef]

- Martos D, Tuka B, Tanaka M, Vécsei L, Telegdy G. Memory Enhancement with Kynurenic Acid and Its Mechanisms in Neurotransmission. Biomedicines 2022;10:849. [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri F, Ebadi Z, Asadollahzadeh E, Naser Moghadasi A. Gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis-related cognitive impairment. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 2022;67:104165. [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter A-K, Guest PC, Sarnyai Z. The Y-Maze for Assessment of Spatial Working and Reference Memory in Mice. Methods Mol Biol 2019;1916:105–11. [CrossRef]

- Galla Z, Rácz G, Grecsó N, Baráth Á, Kósa M, Bereczki C, et al. Improved LC-MS/MS method for the determination of 42 neurologically and metabolically important molecules in urine. Journal of Chromatography B 2021;1179:122846. [CrossRef]

- Galla Z, Rajda C, Rácz G, Grecsó N, Baráth Á, Vécsei L, et al. Simultaneous determination of 30 neurologically and metabolically important molecules: A sensitive and selective way to measure tyrosine and tryptophan pathway metabolites and other biomarkers in human serum and cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of Chromatography A 2021;1635:461775. [CrossRef]

- Barone P. The ‘Yin’ and the ‘Yang’ of the kynurenine pathway: excitotoxicity and neuroprotection imbalance in stress-induced disorders. Behavioural Pharmacology 2019;30:163. [CrossRef]

- Globus MY-T, Ginsberg MD, Busto R. Excitotoxic index — a biochemical marker of selective vulnerability. Neuroscience Letters 1991;127:39–42. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).