Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Baseline Clinical Characteristics

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Characterization of the Study Cohort

3.2. Identification of Risk Factors for OS of Patients with GC

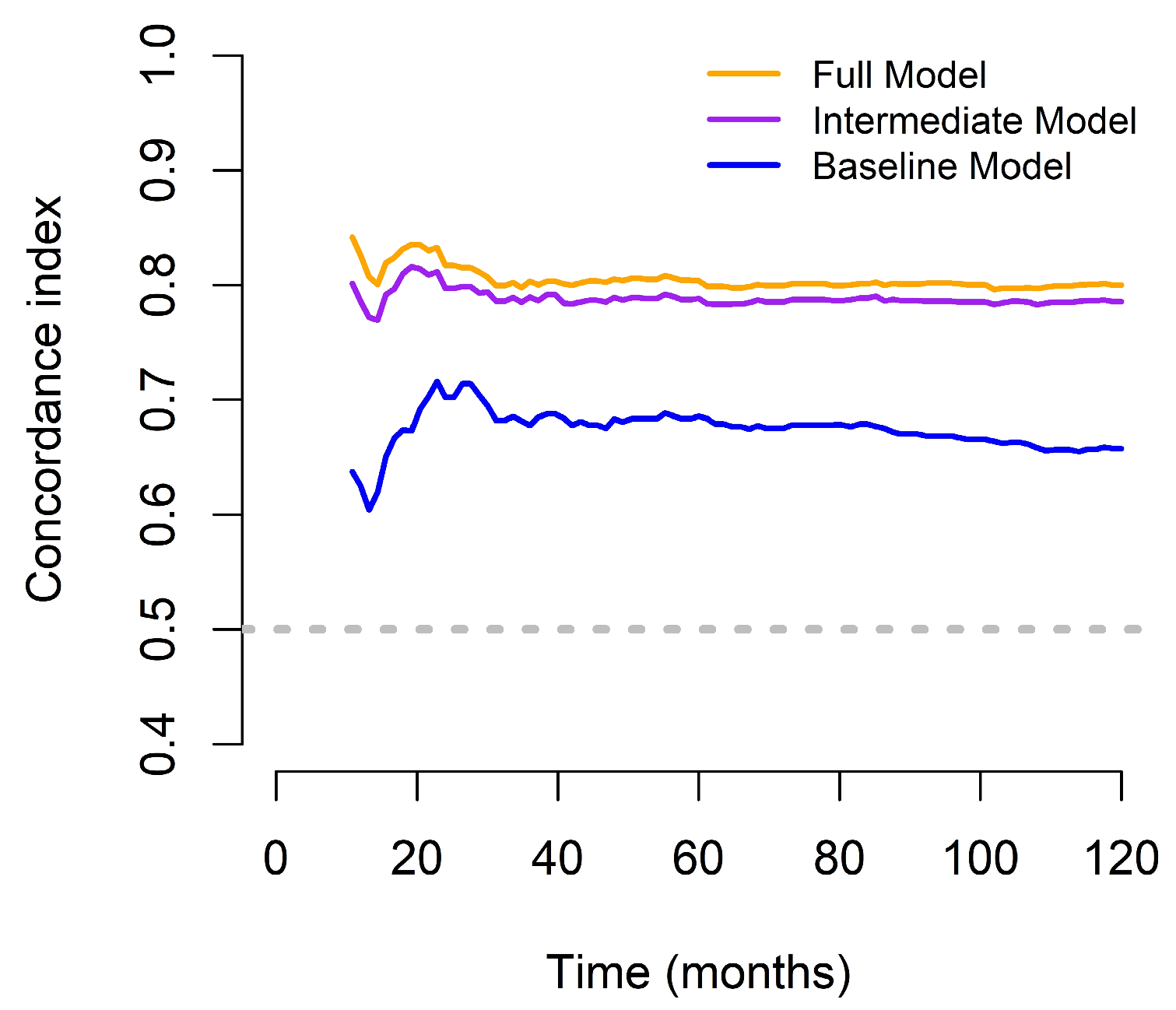

3.3. Comparison of Different OS Predictive Models

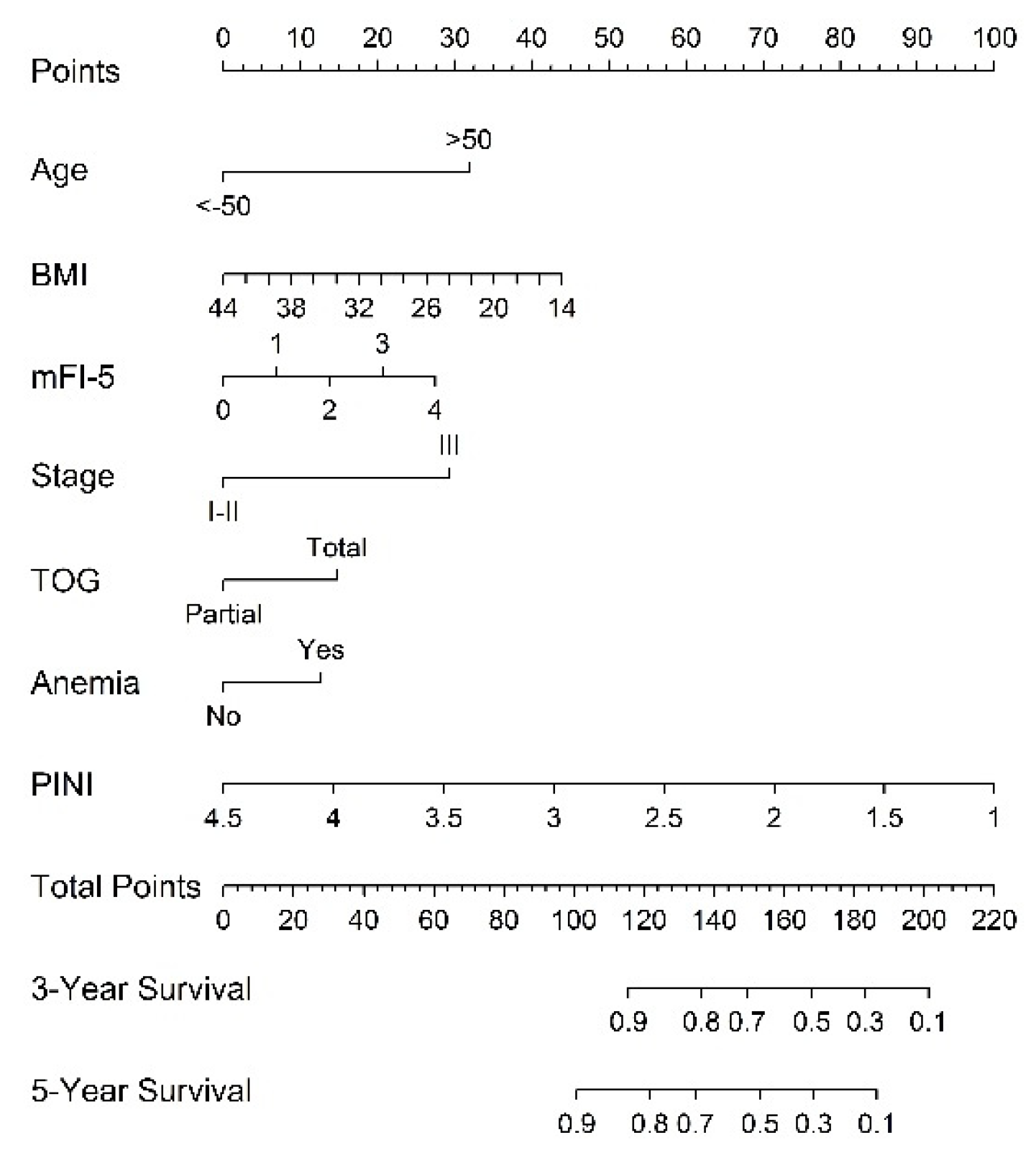

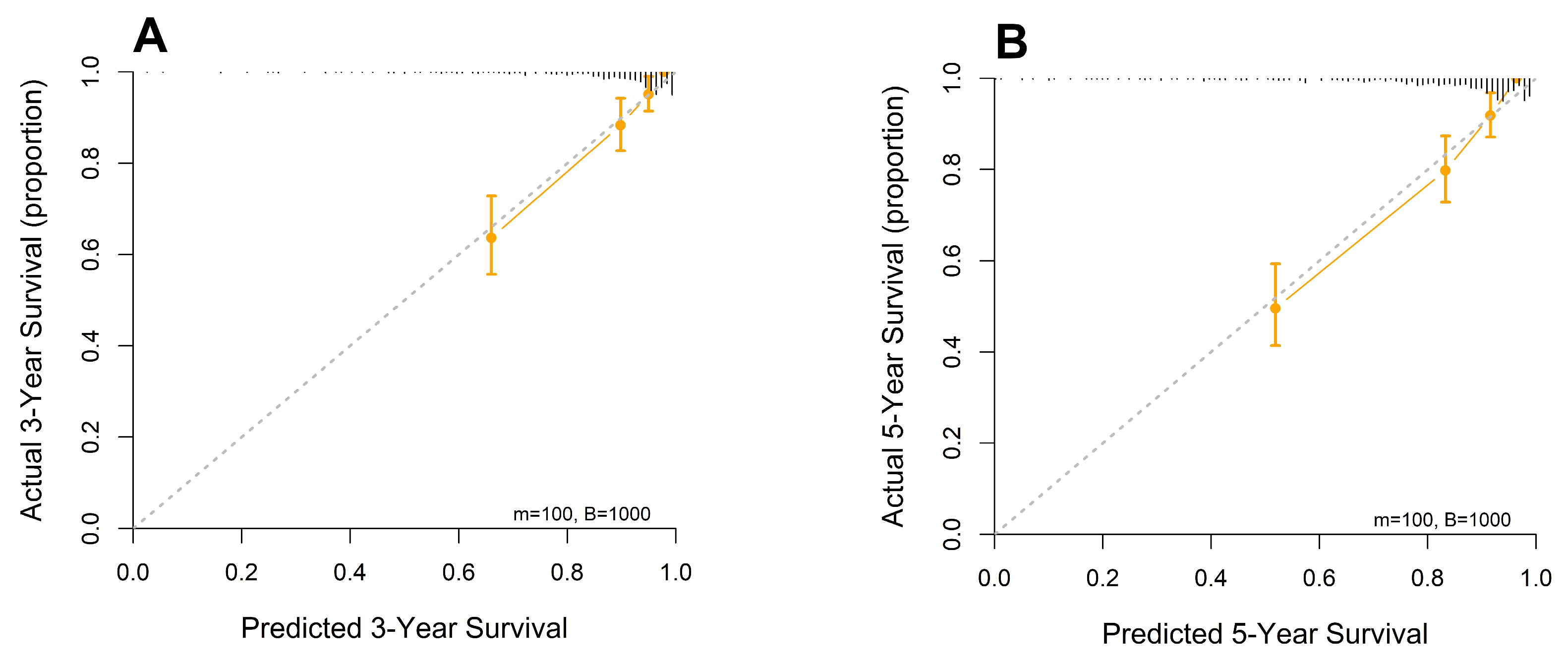

3.4. Establishment and Validation of the Constructed Nomogram

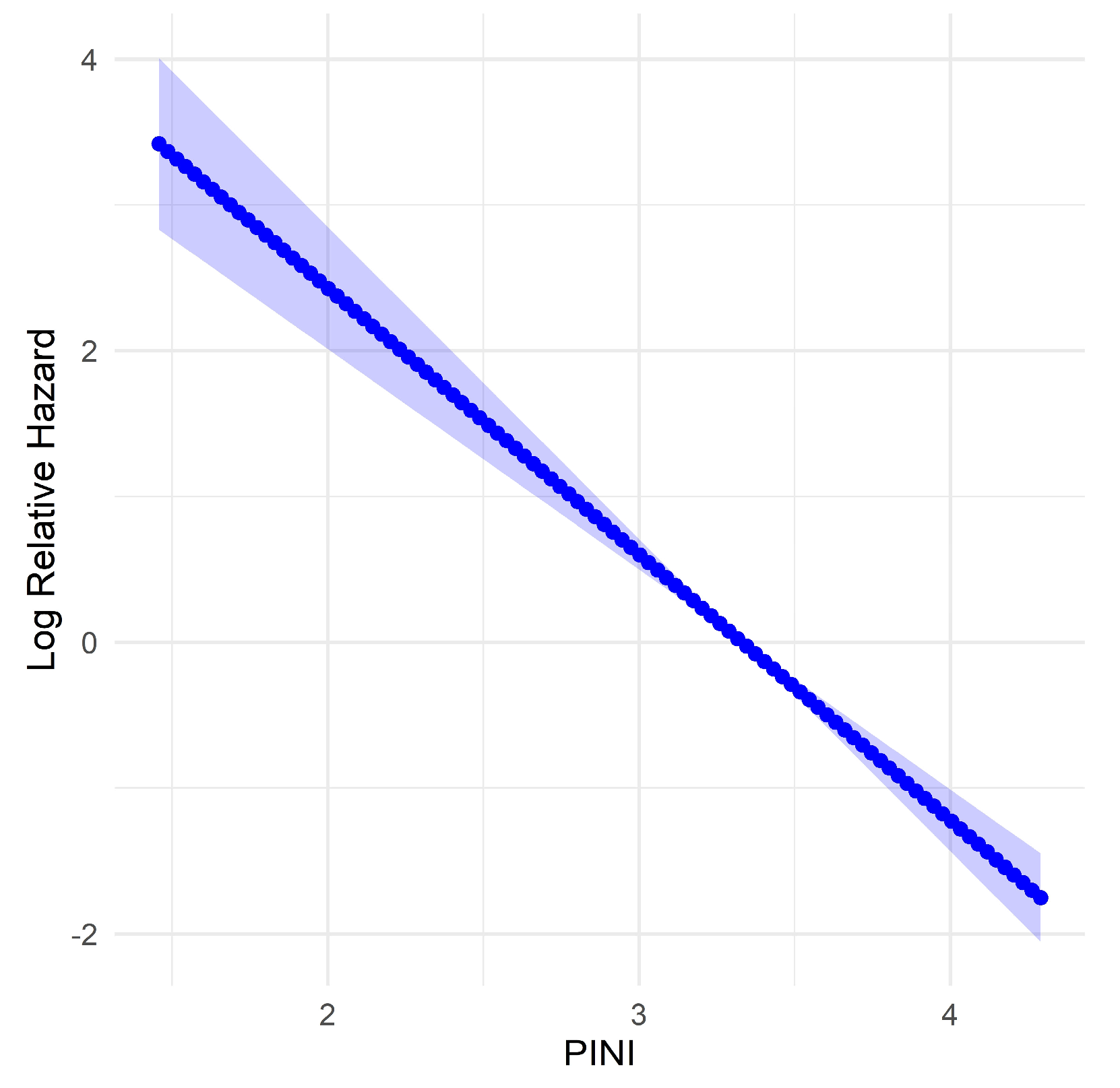

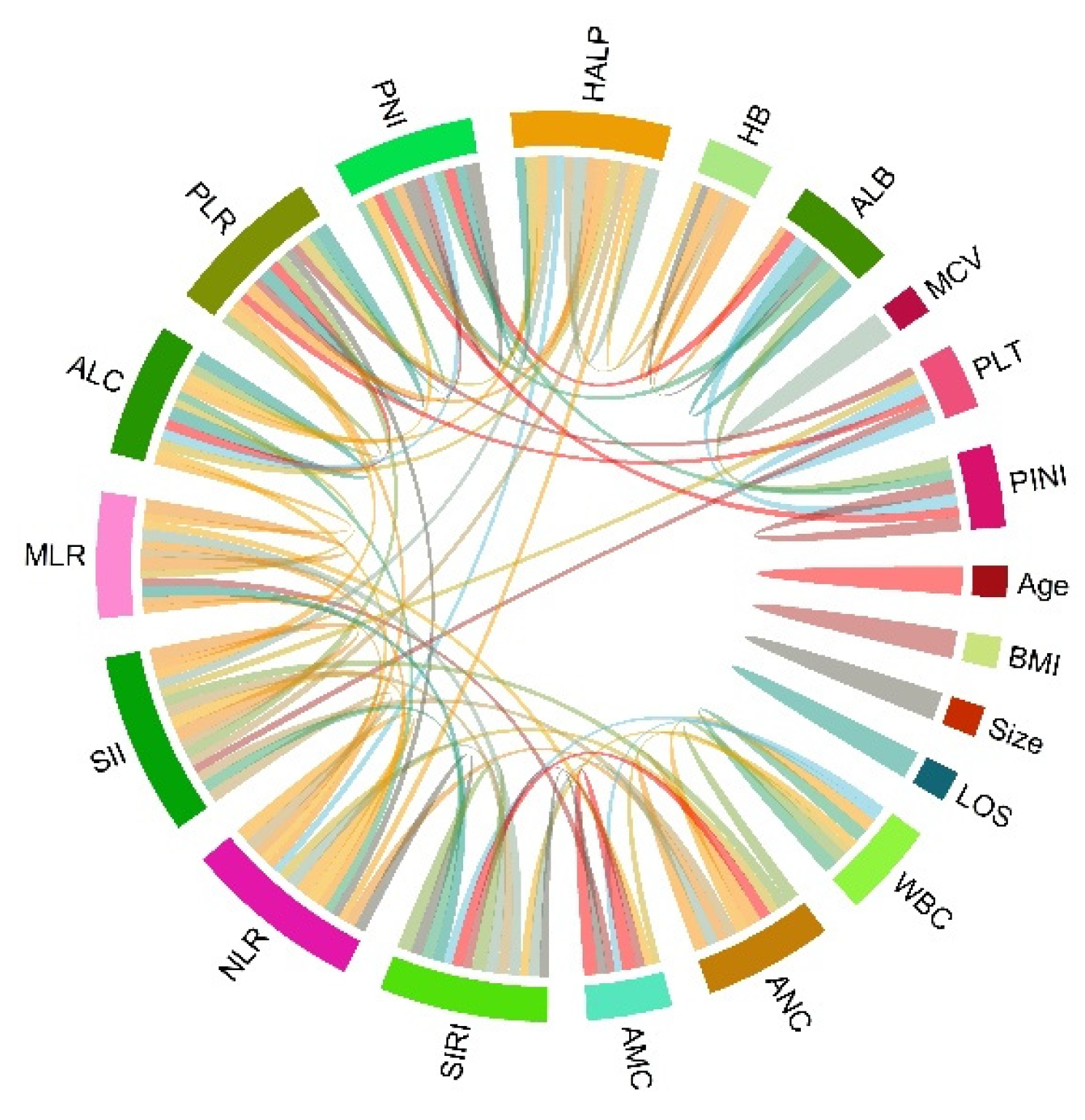

3.5. Evaluation of Predictors for PINI Score

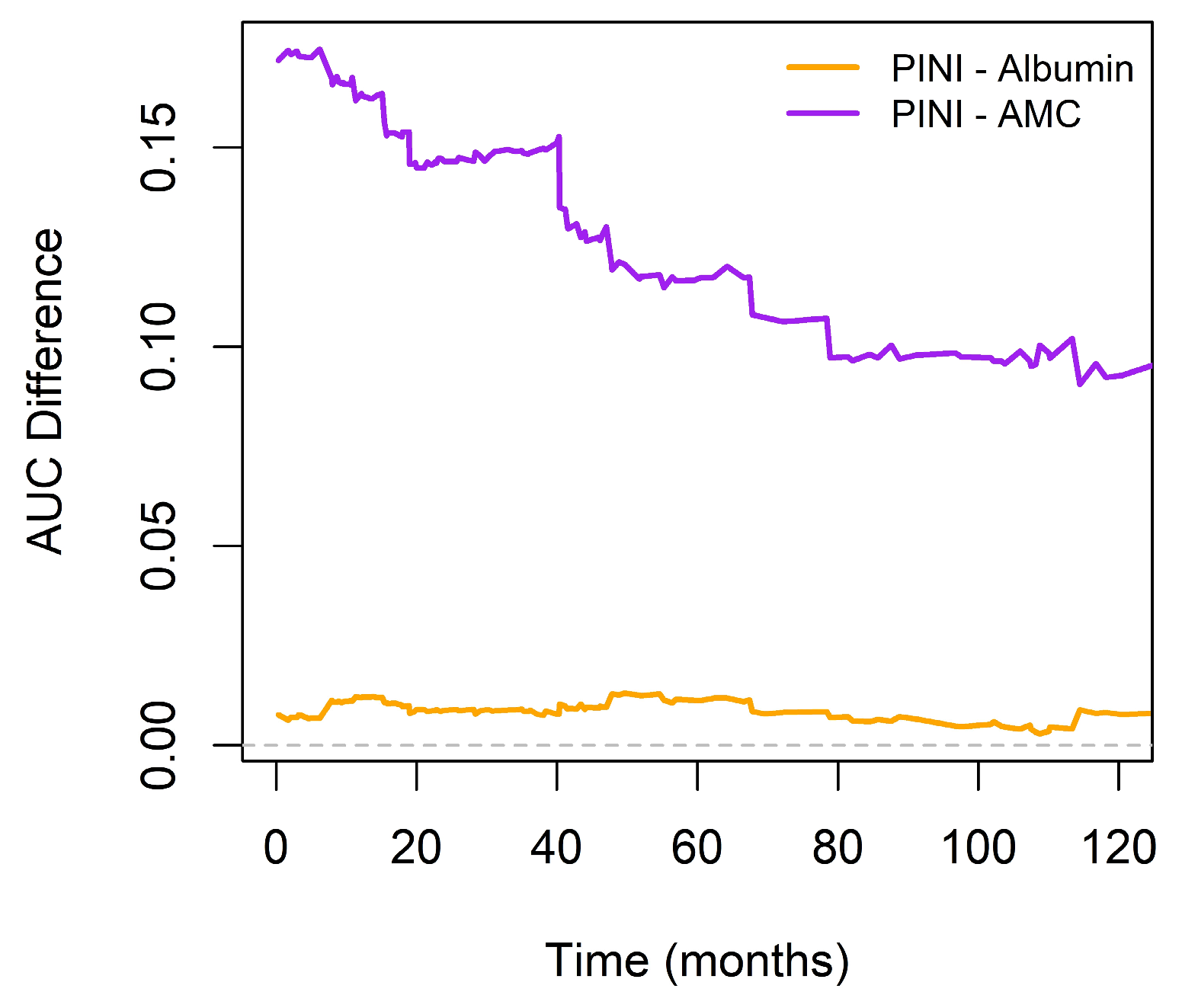

3.6. Comparison of the Prognostic Discriminatory Ability of the PINI Score vs. Albumin and AMC

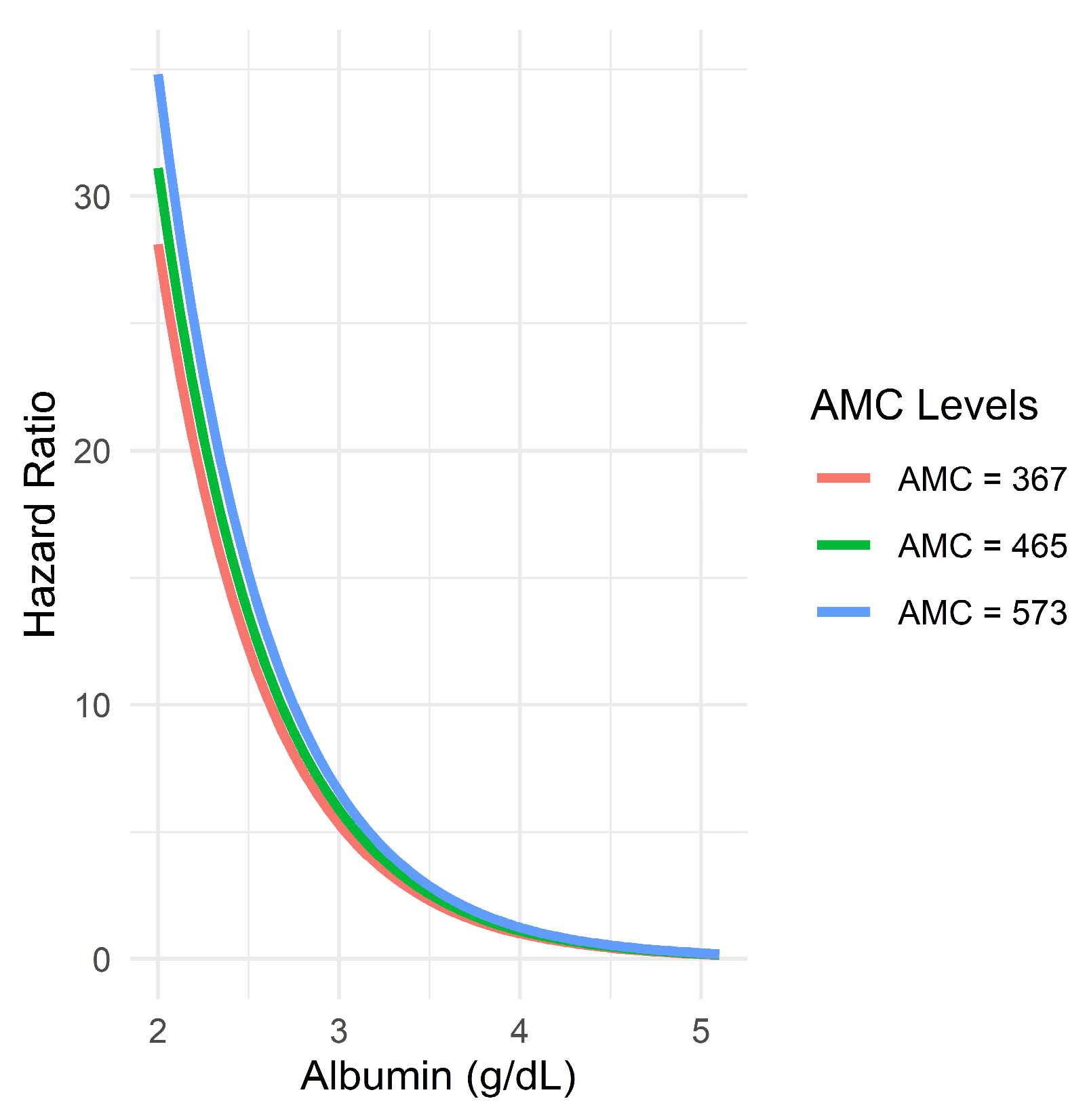

3.7. Evaluation of Possible Interaction Between Albumin and AMC

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ALC | Absolute lymphocyte count |

| AMC | Absolute monocyte count |

| ANC | Absolute neutrophil count |

| ASA-PS | American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CALLY | CRP-albumin-lymphocyte index |

| C-index | Concordance index |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| cNRI | Continuous net reclassification improvement |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| GC | Gastric cancer |

| HALP | Hemoglobin, albumin, lymphocyte, and platelet |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| iAUC | Integrated AUC |

| IDI | Integrated discrimination improvement |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| Lasso | Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator |

| LOS | Length of stay |

| MCV | Mean corpuscular volume |

| mFI-5 | Five-factor modified frail index |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| OS | Overall survival |

| PINI | Prognostic immune nutritional index |

| PLR | Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| PNI | Prognostic nutritional index |

| SII | Systemic immune-inflammation index |

| SIRI | Systemic inflammation response index |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TNM | Tumor–node–metastasis |

| TOG | Type of gastrectomy |

References

- Balachandran, V.P.; Gonen, M.; Smith, J.J.; DeMatteo, R.P. Nomograms in oncology: more than meets the eye. The Lancet. Oncology 2015, 16, e173–e180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oñate-Ocaña, L.F.; Aiello-Crocifoglio, V.; Gallardo-Rincón, D.; Herrera-Goepfert, R.; Brom-Valladares, R.; Carrillo, J.F.; Cervera, E.; Mohar-Betancourt, A. Serum albumin as a significant prognostic factor for patients with gastric carcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology 2007, 14, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crumley, A.B.; Stuart, R.C.; McKernan, M.; McMillan, D.C. Is hypoalbuminemia an independent prognostic factor in patients with gastric cancer? World journal of surgery 2010, 34, 2393–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akula, B.; Doctor, N. A Prospective Review of Preoperative Nutritional Status and Its Influence on the Outcome of Abdominal Surgery. Cureus 2021, 13, e19948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Lee, S. Comparison of the Clinical Value of the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index and Prognostic Nutritional Index as Determinants of Survival Outcome in Patients with Gastric Cancer. Journal of Cancer 2022, 13, 3348–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esashi, R.; Aoyama, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Maezawa, Y.; Hashimoto, I.; Kazama, K.; Morita, J.; Kawahara, S.; Otani, K.; Komori, K.; et al. The CONUT Score Can Predict the Prognosis of Gastric Cancer Patients After Curative Treatment. Anticancer research 2025, 45, 1251–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, M.; Aoyama, T.; Komori, K.; Tamagawa, H.; Tamagawa, A.; Maezawa, Y.; Morita, J.; Onodera, A.; Endo, K.; Hashimoto, I.; et al. The Albumin-Bilirubin Score Is a Prognostic Factor for Gastric Cancer Patients Who Receive Curative Treatment. Anticancer research 2022, 42, 3929–3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.Y.; Zhou, L.N.; Tang, M.; Chen, M.B.; Tao, M. Predicting the Prognosis of Gastric Cancer by Albumin/Globulin Ratio and the Prognostic Nutritional Index. Nutrition and cancer 2020, 72, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G. Albumin/fibrinogen ratio, a predictor of chemotherapy resistance and prognostic factor for advanced gastric cancer patients following radical gastrectomy. BMC Surg 2022, 22, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Fu, Y.; Wang, W.; Jin, X.; Bian, L.; Peng, L. Postoperative ratio of C-reactive protein to albumin is an independent prognostic factor for gastric cancer. Eur J Med Res 2023, 28, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culcu, S.; Yuksel, C.; Aydin, F.; Bakirarar, B.; Aksel, B.; Dogan, L. The effect of CEA/Albumin ratio in gastric cancer patient on prognostic factors. Ann Ital Chir 2022, 93, 447–452. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, I.; Kano, K.; Onuma, S.; Suematsu, H.; Nagasawa, S.; Kanematsu, K.; Furusawa, K.; Hamaguchi, T.; Watanabe, M.; Hayashi, K.; et al. Clinical Significance of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte Ratio/Serum Albumin Ratio in Patients With Metastatic Gastric or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer Administered Trifluridine/Tipiracil. Anticancer research 2023, 43, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Xia, Y.Q.; Xiao, L.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Z.M. Combining the platelet-to-albumin ratio with serum and pathologic variables to establish a risk assessment model for lymph node metastasis of gastric cancer. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2021, 35, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Hu, X.; Huang, T.; Chen, M. Correlation between the C-reactive protein (CRP)-albumin-lymphocyte (CALLY) index and the prognosis of gastric cancer patients after gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgery today 2025, 55, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargin, Z.G.; Dusunceli, I. The Effect of HALP Score on the Prognosis of Gastric Adenocarcinoma. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2022, 32, 1154–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, M.; Caro, A.A.; Raes, G.; Laoui, D. Systemic Reprogramming of Monocytes in Cancer. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Lei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Gong, W.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, G.M.; et al. CCL2/CCR2 pathway mediates recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells to cancers. Cancer Lett 2007, 252, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassetta, L.; Pollard, J.W. Targeting macrophages: therapeutic approaches in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 887–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, S.; Wirsik, N.M.; Kalkum, E.; Seide, S.E.; Nienhüser, H.; Müller, B.; Billeter, A.; Büchler, M.W.; Schmidt, T.; Probst, P. Systematic Review of Prognostic Role of Blood Cell Ratios in Patients with Gastric Cancer Undergoing Surgery. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Lee, S.; Lee, Y.J. Monocyte-to-lymphocyte ratio as a determinant of survival in patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy: A cohort study. Medicine 2023, 102, e33930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eo, W.K.; Jeong, D.W.; Chang, H.J.; Won, K.Y.; Choi, S.I.; Kim, S.H.; Chun, S.W.; Oh, Y.L.; Lee, T.H.; Kim, Y.O.; et al. Absolute monocyte and lymphocyte count prognostic score for patients with gastric cancer. World journal of gastroenterology 2015, 21, 2668–2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yazici, H.; Yegen, S.C. Is Systemic Inflammatory Response Index (SIRI) a Reliable Tool for Prognosis of Gastric Cancer Patients Without Neoadjuvant Therapy? Cureus 2023, 15, e36597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, S.H.; Hao, J.; Shivakumar, M.; Nam, Y.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.J.; Ryoo, S.B.; Choe, E.K.; Jeong, S.Y.; Park, K.J.; et al. Development and validation of a novel strong prognostic index for colon cancer through a robust combination of laboratory features for systemic inflammation: a prognostic immune nutritional index. British journal of cancer 2022, 126, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.; Wei, L.; Liu, M.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, G.; Gao, S.; Wang, Q.; Lin, X.; Tang, S.; Gan, J. Prognostic significance of preoperative prognostic immune and nutritional index in patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer. BMC cancer 2022, 22, 1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibutani, M.; Kashiwagi, S.; Fukuoka, T.; Iseki, Y.; Kasashima, H.; Maeda, K. Significance of the Prognostic Immune and Nutritional Index in Patients With Stage I-III Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Diagn Progn 2023, 3, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauren, P. THE TWO HISTOLOGICAL MAIN TYPES OF GASTRIC CARCINOMA: DIFFUSE AND SO-CALLED INTESTINAL-TYPE CARCINOMA. AN ATTEMPT AT A HISTO-CLINICAL CLASSIFICATION. Acta pathologica et microbiologica Scandinavica 1965, 64, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mranda, G.M.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, X.G.; Yu, W.; Wei, T.; Xiang, Z.P.; Liu, J.J.; Ding, Y.L. Revisiting the 8th AJCC system for gastric cancer: A review on validations, nomograms, lymph nodes impact, and proposed modifications. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022, 75, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, C.; Kendall, M.C.; Apruzzese, P.; De Oliveira, G.S. American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification as a reliable predictor of postoperative medical complications and mortality following ambulatory surgery: an analysis of 2,089,830 ACS-NSQIP outpatient cases. BMC Surg 2021, 21, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, B.M.; Adams, M.A.; Schenker, M.L.; Gelbard, R.B. The 5 and 11 Factor Modified Frailty Indices are Equally Effective at Outcome Prediction Using TQIP. J Surg Res 2020, 255, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, S.; Aalberg, J.J.; Soriano, R.P.; Divino, C.M. New 5-Factor Modified Frailty Index Using American College of Surgeons NSQIP Data. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2018, 226, 173–181.e178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Yao, X.; Cen, D.; Zhi, Y.; Zhu, N.; Xu, L. The prognostic role of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio on overall survival in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 2020, 20, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirahara, N.; Tajima, Y.; Matsubara, T.; Fujii, Y.; Kaji, S.; Kawabata, Y.; Hyakudomi, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Uchida, Y.; Taniura, T. Systemic Immune-Inflammation Index Predicts Overall Survival in Patients with Gastric Cancer: a Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2021, 25, 1124–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.J.; Ji, L.D.; Lian, L.; Ma, Z.F.; Luo, Y.T.; Lai, J.L.; Wang, K.J. [Epidemiological trend of early-onset gastric cancer and late-onset gastric cancer in China from 2000 to 2019]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi 2023, 44, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, M.D.; Motta, I. Anemia in Clinical Practice-Definition and Classification: Does Hemoglobin Change With Aging? Seminars in hematology 2015, 52, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Cook, N.R.; Gerds, T.; Gonen, M.; Obuchowski, N.; Pencina, M.J.; Kattan, M.W. Assessing the performance of prediction models: a framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.) 2010, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipman, J.; Braun, D. Simpson’s paradox in the integrated discrimination improvement. Stat Med 2017, 36, 4468–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, N.R.; Demler, O.V.; Paynter, N.P. Clinical risk reclassification at 10 years. Stat Med 2017, 36, 4498–4502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, M.A.; Oratz, M.; Schreiber, S.S. Serum albumin. Hepatology 1988, 8, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamai, K.; Okamura, S.; Makino, S.; Yamamura, N.; Fukuchi, N.; Ebisui, C.; Inoue, A.; Yano, M. C-reactive protein/albumin ratio predicts survival after curative surgery in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Updates Surg 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forones, N.M.; Mandowsky, S.V.; Lourenço, L.G. Serum levels of interleukin-2 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha correlate to tumor progression in gastric cancer. Hepato-gastroenterology 2001, 48, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Ishida, S.; Hashimoto, I.; Seike, T.; Abe, Y.; Nakaya, Y.; Nakanishi, H. Serum albumin levels correlate with inflammation rather than nutrition supply in burns patients: a retrospective study. The journal of medical investigation: JMI 2014, 61, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, T.; Kunisaki, C.; Ono, H.A.; Makino, H.; Akiyama, H.; Endo, I. Implications of BMI for the Prognosis of Gastric Cancer among the Japanese Population. Digestive surgery 2015, 32, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Kim, Y.J. Muscle-Related Parameters as Determinants of Survival in Patients with Stage I-III Gastric Cancer Undergoing Gastrectomy. Journal of Cancer 2021, 12, 5664–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuke, H.; Matsubara, D.; Kubota, T.; Kiuchi, J.; Kubo, H.; Ohashi, T.; Shimizu, H.; Arita, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Konishi, H.; et al. Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index Predicts Poor Prognosis of Patients After Curative Surgery for Gastric Cancer. Cancer Diagn Progn 2021, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirahara, N.; Tajima, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Kaji, S.; Kawabata, Y.; Hyakudomi, R.; Yamamoto, T.; Taniura, T. Prediction of postoperative complications and survival after laparoscopic gastrectomy using preoperative Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index in elderly gastric cancer patients. Surgical endoscopy 2021, 35, 1202–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugawara, K.; Yamashita, H.; Urabe, M.; Okumura, Y.; Yagi, K.; Aikou, S.; Seto, Y. Geriatric Nutrition Index Influences Survival Outcomes in Gastric Carcinoma Patients Undergoing Radical Surgery. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 2021, 45, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Eo, W.; Lee, S. Prognostic significance of a five-factor modified frailty index in patients with gastric cancer undergoing curative-intent resection: A cohort study. Medicine 2023, 102, e36065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, T.; Saito, H.; Miyauchi, W.; Shishido, Y.; Miyatani, K.; Matsunaga, T.; Tatebe, S.; Fujiwara, Y. The type of gastrectomy and modified frailty index as useful predictive indicators for 1-year readmission due to nutritional difficulty in patients who undergo gastrectomy for gastric cancer. BMC Surg 2021, 21, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.N.; Das, D.; Turrentine, F.E.; Bauer, T.W.; Adams, R.B.; Zaydfudim, V.M. Morbidity and Mortality After Gastrectomy: Identification of Modifiable Risk Factors. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 2016, 20, 1554–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Z.; Yang, Y.C.; Chen, Y.; Wu, C.C.; Lin, R.F.; Wang, Z.N.; Zhang, X. Preoperative Anemia or Low Hemoglobin Predicts Poor Prognosis in Gastric Cancer Patients: A Meta-Analysis. Disease markers 2019, 2019, 7606128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | % or median (IQR) | Variables | % or median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 60.5 (52.0–70.0) | Tumor size, cm | 3.0 (2.0–5.5) |

| Sex | Lymphatic invasion | ||

| Men | 330 (67.1) | No | 325 (66.1) |

| Women | 162 (32.9) | Yes | 167 (33.9) |

| ASA-PS | Vascular invasion | ||

| I/II | 436 (88.6) | No | 466 (94.7) |

| III | 56 (11.4) | Yes | 26 (5.3) |

| mFI-5 score | Perineural invasion | ||

| 0–1 | 381 (77.4) | No | 442 (89.8) |

| 2–4 | 111 (22.6) | Yes | 50 (10.2) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.7 (21.4–26.0) | Length of stay, days | 9 (8–11) |

| Location | Adjuvant therapy | ||

| Upper | 49 (10.0) | No | 320 (65.0) |

| Middle | 168 (34.1) | Yes | 172 (35.0) |

| Lower | 267 (54.3) | WBC, per μL | 6500 (5345–7850) |

| Diffuse | 8 (1.6) | ANC, per μL | 3660.5 (2899.5–4806.0) |

| T stage | ALC, per μL | 1907.5 (1534.5–2326.0) | |

| 0–1 | 334 (67.9) | AMC, per μL | 465.0 (367.0–573.5) |

| 2–4 | 158 (32.1) | Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.1 (11.3–14.2) |

| N stage | MCV, fL | 92.2 (88.5–95.5) | |

| 0 | 320 (65.0) | Platelet, × 103 per μL | 238.0 (204.5–281.0) |

| 1–3 | 172 (35.0) | NLR | 1.9 (1.4–2.7) |

| TNM stage | PLR | 122.8 (96.7–159.1) | |

| I–II | 393 (79.9) | MLR | 2.3 (1.8–3.1) |

| III | 99 (20.1) | SII | 459.4 (303.8–682.7) |

| Histology | SIRI | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | |

| Intestinal | 243 (49.4) | Albumin, g/dL | 4.1 (3.9–4.3) |

| Others | 249 (50.6) | PNI | 51.2 (47.2–54.7) |

| Type of gastrectomy | HALP score | 44.5 (30.4–58.5) | |

| Patial | 389 (79.1) | PINI score | 3.4 (3.2–3.6) |

| Total | 103 (20.9) |

| Covariate | Univariate HR (95% CI) |

p-value | Multivariate HR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (≤50 vs. >50) | 0.16 (0.08–0.35) | < 0.001 | 0.32 (0.15–0.69) | 0.004 |

| Sex (female vs. male) | 0.59 (0.40–0.87) | 0.008 | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.91 (0.87–0.96) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.90–1.00) | 0.044 |

| ASA-PS score† | 2.04 (1.42–2.91) | < 0.001 | ||

| mFI-5† | 1.50 (1.28–1.76) | < 0.001 | 1.28 (1.08–1.52) | 0.004 |

| TNM stage (IIIA vs. I/II) | 4.51 (3.23–6.31) | < 0.001 | 2.87 (1.99–4.13) | < 0.001 |

| Histology (intestinal vs. others) | 1.05 (0.75–1.45) | 0.787 | ||

| Lymphatic invasion (yes vs. no) | 2.79 (2.01–3.89) | < 0.001 | ||

| Vascular invasion (yes vs. no) | 3.32 (1.97–5.59) | < 0.001 | ||

| Perineural invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.99 (1.25–3.17) | 0.004 | ||

| Tumor size | 1.18 (1.14–1.22) | < 0.001 | ||

| TOG (total vs. partial) | 2.35 (1.66–3.33) | < 0.001 | 1.70 (1.19–2.42) | 0.003 |

| LOS, days | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | < 0.001 | ||

| Adjuvant therapy (yes vs. no) | 2.48 (1.78–3.45) | < 0.001 | ||

| WBC | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.829 | ||

| AMC | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.003 | ||

| Anemia (yes vs. no) | 3.57 (2.55–5.01) | < 0.001 | 1.58 (1.07–2.32) | 0.020 |

| MCV | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.008 | ||

| Platelet | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 0.126 | ||

| Albumin | 0.18 (0.14–0.25) | < 0.001 | ||

| NLR | 1.16 (1.09–1.23) | < 0.001 | ||

| PLR | 1.01 (1.00–1.09) | < 0.001 | ||

| MLR | 1.42 (1.29–1.57) | < 0.001 | ||

| SII | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | < 0.001 | ||

| SIRI | 1.21 (1.11–1.32) | < 0.001 | ||

| PNI | 0.87 (0.85–0.90) | < 0.001 | ||

| HALP score | 0.97 (0.96–0.98) | < 0.001 | ||

| PINI score | 0.16 (0.11–0.22) | < 0.001 | 0.36 (0.25–0.52) | < 0.001 |

| Metrics | Full model (FM)a | Intermediate model (IM)b | Baseline model (BM)c | FM vs. BM Difference (SE) | p-value | FM vs. IM Difference (SE) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-index | 0.815 (0.017) | 0.797 (0.017) | 0.659 (0.020) | 0.159 (0.018) | < 0.001 | 0.018 (0.007) | 0.004 |

| iAUC | 0.791 (0.015) | 0.776 (0.017) | 0.640 (0.019) | 0.144 (0.019) | < 0.001 | 0.014 (0.006) | 0.004 |

| 3-year OS | |||||||

| AUC | 0.835 (0.024) | 0.821 (0.026) | 0.690 (0.032) | 0.144 (0.027) | < 0.001 | 0.013 (0.011) | 0.156 |

| IDI | 0.106 (0.027) | < 0.001 | 0.018 (0.016) | 0.206 | |||

| cNRI | 0.394 (0.066) | < 0.001 | 0.134 (0.072) | 0.054 | |||

| 5-year OS | |||||||

| AUC | 0.857 (0.020) | 0.839 (0.022) | 0.711 (0.027) | 0.146 (0.022) | < 0.001 | 0.019 (0.009) | 0.012 |

| IDI | 0.141 (0.029) | < 0.001 | 0.031 (0.016) | 0.032 | |||

| cNRI | 0.383 (0.054) | < 0.001 | 0.171 (0.062) | 0.012 |

| Metrics | Full model (FM)a | Albumin model (AM)b | FM vs. AM Difference (SE) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-index | 0.815 (0.017) | 0.810 (0.025) | 0.005 (0.005) | 0.280 |

| iAUC | 0.791 (0.015) | 0.787 (0.015) | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.180 |

| AUC | ||||

| 3-year OS | 0.835 (0.024) | 0.833 (0.025) | 0.002 (0.007) | 0.872 |

| 5-yerar OS | 0.857 (0.020) | 0.851 (0.021) | 0.006 (0.006) | 0.412 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).