1. Introduction

The tumor microenvironment (TME) includes cells and secreted substances and influences the efficacy of antitumor treatments. Immunosuppressive cells, such as regulatory T cells (Treg), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), play essential roles in the formation of TME [

1,

2,

3]. The development of cancer immunotherapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors, has been a dramatic game-changer in cancer treatment [

4].

Hypoxia, critically low oxygen levels, has potently correlated with the driving tumor toward a more aggressive phenotype and a poorer prognosis for tumor patients [

5,

6]. Hypoxic conditions are a beneficial environment for cancer metastasis [

7]. Hypoxia drives hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-dependent alteration of gene expression profile, which is related to proteome and metabolome [

5,

6,

8]. Under hypoxic conditions, cancer cells release adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP) into the extracellular space, which is sequentially converted into adenosine 5'-diphosphate (ADP), adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP), and adenosine (ADO) by membrane-anchored ectoenzymes CD39 and CD73 [

6]. High levels of extracellular ADO in tumors play a pivotal role in evading antitumor immune responses [

9]. The ADO receptor is composed of four members, A2A ADO receptor (A2AR) is predominantly expressed in most immune cells, including T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, and neutrophils [

10]. Genetic deletion of A2AR in mice rejected tumors via T cell function [

9]. Thus, extracellular ADO produced by CD39/CD73 is one of the key regulators of the immunosuppressive TME.

CD73 is a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored 70-kDa protein encoded by the NT5E gene, which hydrolyzes extracellular AMP into ADO and phosphate. CD73 is composed of two major domains: the N-terminal domain coordinates two catalytic divalent Zn

2+ and Co

2+ metal ions, whereas the C-terminal domain provides a binding site for AMP to generate ADO [

11,

12]. In immunosuppressive TME, increasing ADO production by CD73 weakens the effects of tumor-killing of effector cells, including T cells, B cells, and NK cells [

13,

14,

15,

16]. CD73 expression is confirmed in numerous cancer types, such as glioma [

17], breast [

18], bladder [

19], pancreas [

20], ovary [

21], and lung cancers [

22]. CD73 expression protects cancer cells from being eliminated by the immune system. Furthermore, high CD73 expression induces resistance against chemotherapy [

23,

24]. On the other hand, A2AR upregulates the expression of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and lymphocyte activation gene 3 (LAG-3) immune checkpoint molecules in T cells [

25,

26]. A2AR activation also promotes the differentiation of CD4

+ T cells into Treg with high cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) expression [

27]. CD73 and PD-1 synergistically govern CD4

+ T cells activation [

28]. ADO does not induce migration of tumor cells without A2AR [

26], demonstrating that the CD73-metabolized ADO-A2AR axis exhibits potential as a target of tumor immunotherapy. Not only expressed on the cell surface, CD73 in small extracellular vesicles also constitutes immunosuppressive environments [

29,

30]. A variety of clinical trials targeting CD73 are currently underway [

31].

To date, we have succeeded in developing numerous monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) targeting membrane proteins, including PD-L1 (clone L

1Mab-13) [

32], TIGIT (clone TgMab-2) [

33], CD20 (clone C

20Mab-11) [

34], and EphB6 (clone Eb

6Mab-3) [

35] by using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method. The CBIS method is a high-throughput screening method using flow cytometry to obtain a wide variety of antibodies that bind multiple epitopes, including extracellular modifications of membrane proteins. In this study, we have successfully established a novel anti-mouse CD73 (mCD73) mAb (clone C

73Mab-9) using the CBIS method that can be used for flow cytometry and western blot.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell Lines and Plasmids

LN229 (glioblastoma), Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, and P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1, mouse myeloma), and NMuMG (mouse mammary gland) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). MUSS (histiocyte-like cells from spontaneous sarcoma from mice) cell line, a spontaneous malignant fibrous histiocytoma originating in mice, was provided from the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University (Miyagi, Japan). The expression plasmid of Nt5e (mouse 5' nucleotidase, ecto; mCD73) (pCMV6neoNt5e-Myc-DDK (Catalog No.: MR227439, Accession No.: NM_011851) was obtained from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). The mCD73 expression vector was transfected into cell lines using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, LN229 and CHO-K1, which stably overexpressed mCD73 (hereafter described as LN229/mCD73 and CHO/mCD73, respectively), were stained with an anti-mCD73 mAb (clone TY/11.8; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and sorted using the SH800 cell sorter (Sony corp., Tokyo, Japan).

2.2. Antibodies

A purified anti-mouse CD73 Antibody (clone TY/11.8, rat IgG1, kappa) was purchased from BioLegend. (San Diego, CA, USA).

2.3. Hybridoma Production

For obtaining anti-mCD73 mAbs, a 6-week-old female Jcl: SD rat, purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan), was immunized with LN229/mCD73 (1 × 109 cells) via the intraperitoneal route. The LN229/mCD73 cells as immunogen were harvested after brief exposure to 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). As an adjuvant, Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) was mixed with the immunogen in the first immunization. Three additional injections of 1 × 109 cells of LN229/mCD73 were administered every week via the intraperitoneal route. A final booster injection was performed with LN229/mCD73 (1 × 109 cells) intraperitoneally two days before harvesting splenocytes from the immunized rat. Subsequently, splenocytes from LN229/mCD73-immunized rat and P3U1 mouse myeloma cells were fused using polyethylene glycol 1500 (PEG1500; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

2.4. Flow Cytometry

All cells were collected using 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). The cells were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.) as described previously [

35].

2.5. Determination of the Binding Affinity by Flow Cytometry

CHO/mCD73 cells were suspended in 100 μL serially diluted C

73Mab-9 (30 µg/mL to 0.002 µg/mL) and TY/11.8 (an anti-mouse CD73 mAb, 30 µg/mL to 0.002 µg/mL), after which Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rat IgG (1:200) was added. MUSS cells were suspended in 100 μL serially diluted C

73Mab-9 (50 µg/mL to 0.003 µg/mL) and TY/11.8 (10 µg/mL to 0.0006 µg/mL), after which Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rat IgG (1:200) was reacted. The dissociation constant (K

D) was determined as described previously [

35].

2.6. Western Blotting

Cell lysates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Western blotting was performed using C

73Mab-9 (5 μg/mL), TY/11.8 (5 μg/mL), an anti-DYKDDDDK mAb (1E6, 0.5 μg/mL), and an anti-IDH1 mAb (RcMab-1, 1 μg/mL) as described previously [

34].

3. Results

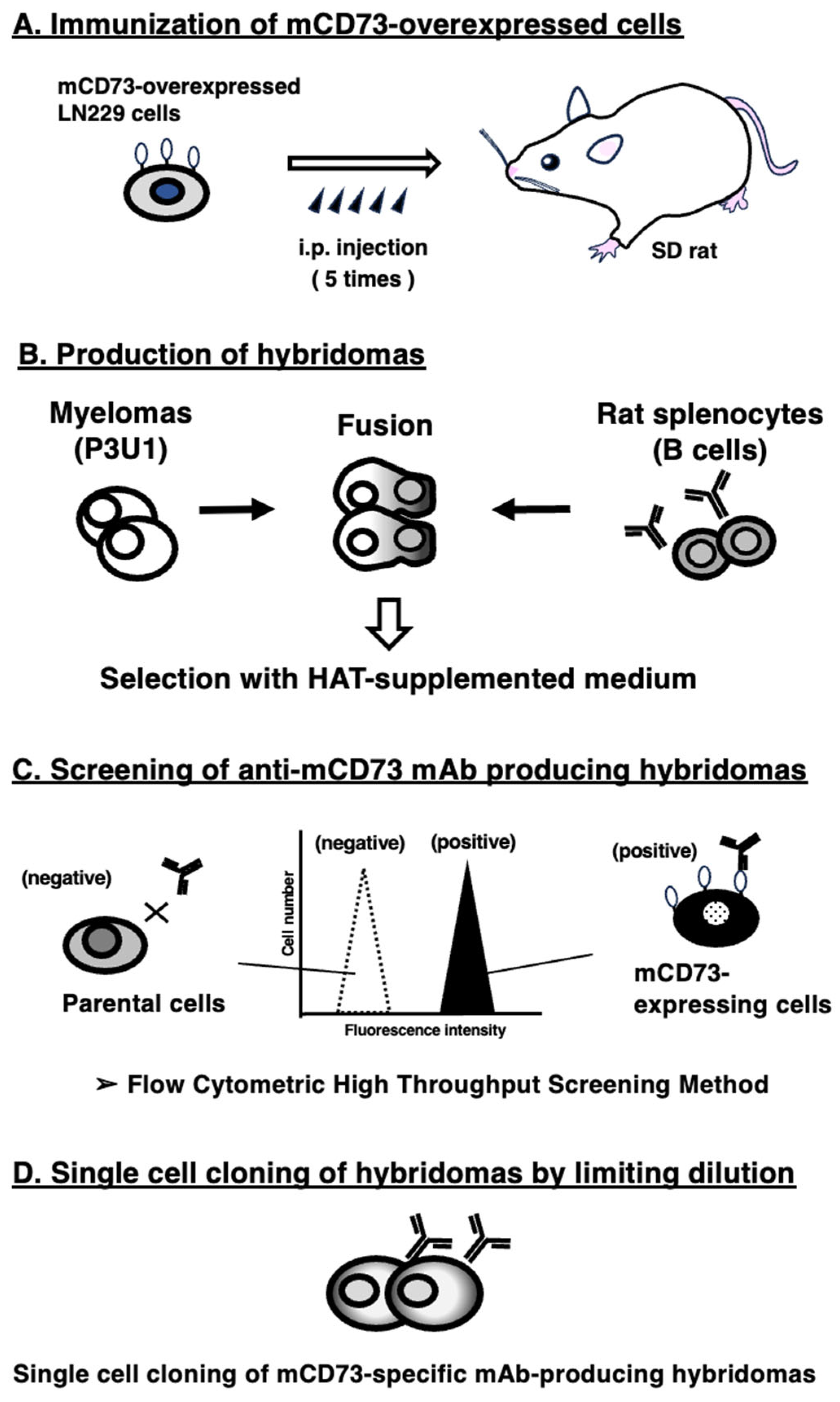

3.1. Development of Anti-mCD73 mAbs Using the CBIS Method

To establish anti-mCD73 mAbs, we employed the CBIS method using mCD73-overexpressed cells. Anti-mCD73 mAb-producing hybridomas were screened by using flow cytometry (

Figure 1). A female Jcl:SD rat was intraperitoneally immunized with LN229/mCD73 (1 × 10

9 cells/time) every week, 5 times in total. Subsequently, rat splenocytes and P3U1 myelomas were fused by PEG1500. Hybridomas were seeded into 96-well plates with HAT-containing medium, after which the screening using flow cytometry was conducted to extract CHO/mCD73-reactive and parental CHO-K1-nonreactive supernatants of hybridomas. We successfully obtained some highly CHO/mCD73-reactive supernatants of hybridomas. After limiting dilution and additional investigations, we finally established the highly sensitive clone C

73Mab-9 (rat IgG

2a, lambda).

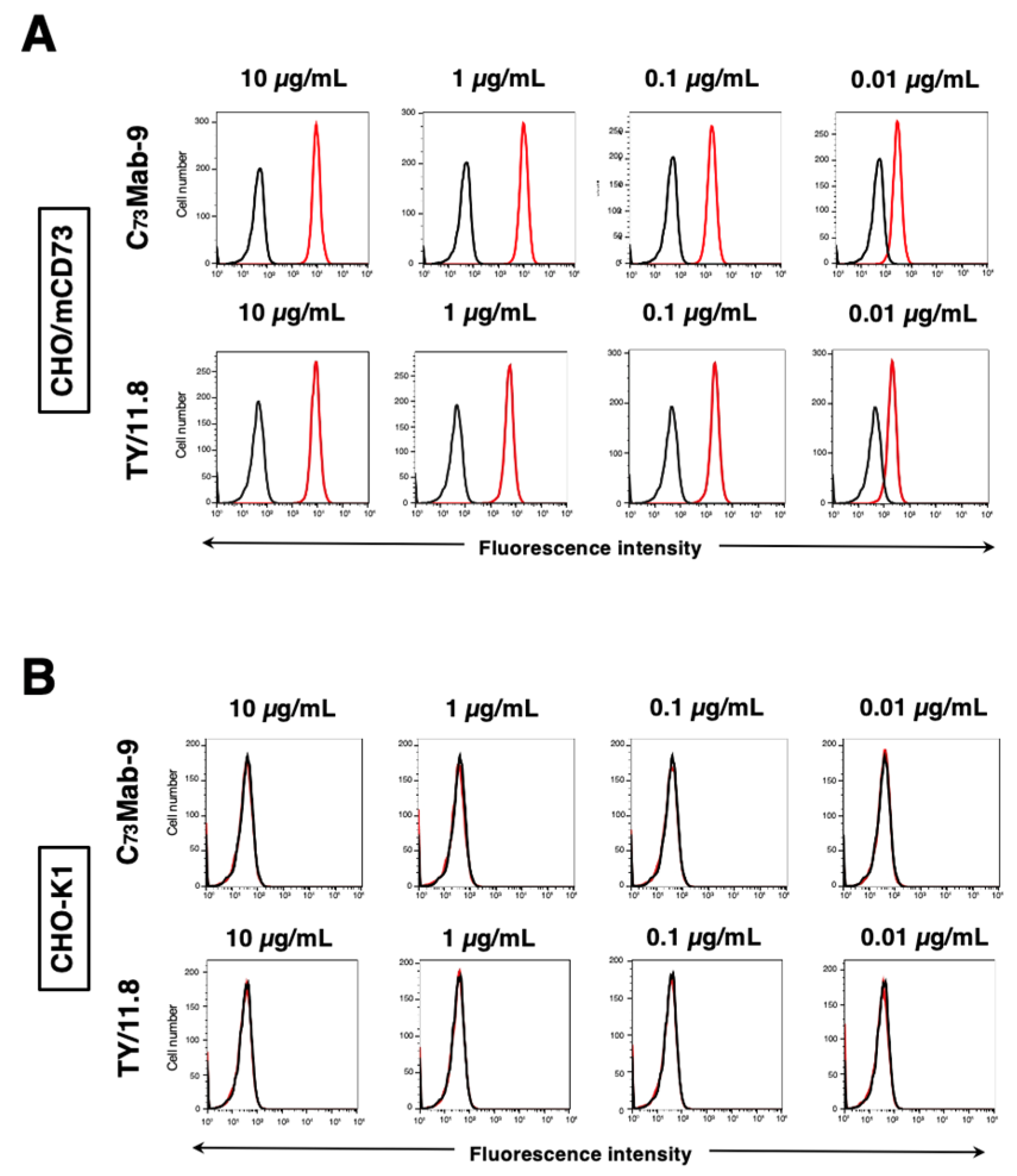

3.2. Evaluation of The Antibody Reactivity Using Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was conducted using C

73Mab-9 and a commercially available anti-mouse CD73 mAb (clone TY/11.8) against CHO-K1 and CHO/mCD73 cells. Results indicated that C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 recognized CHO/mCD73 dose-dependently (

Figure 2A). Reactivity is almost identical between C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 to CHO/mCD73 (

Figure 2A). Both C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 never reacted with parental CHO-K1 cells even at a concentration of 10 µg/mL (

Figure 2B). Thus, C

73Mab-9 can detect mCD73 in flow cytometry.

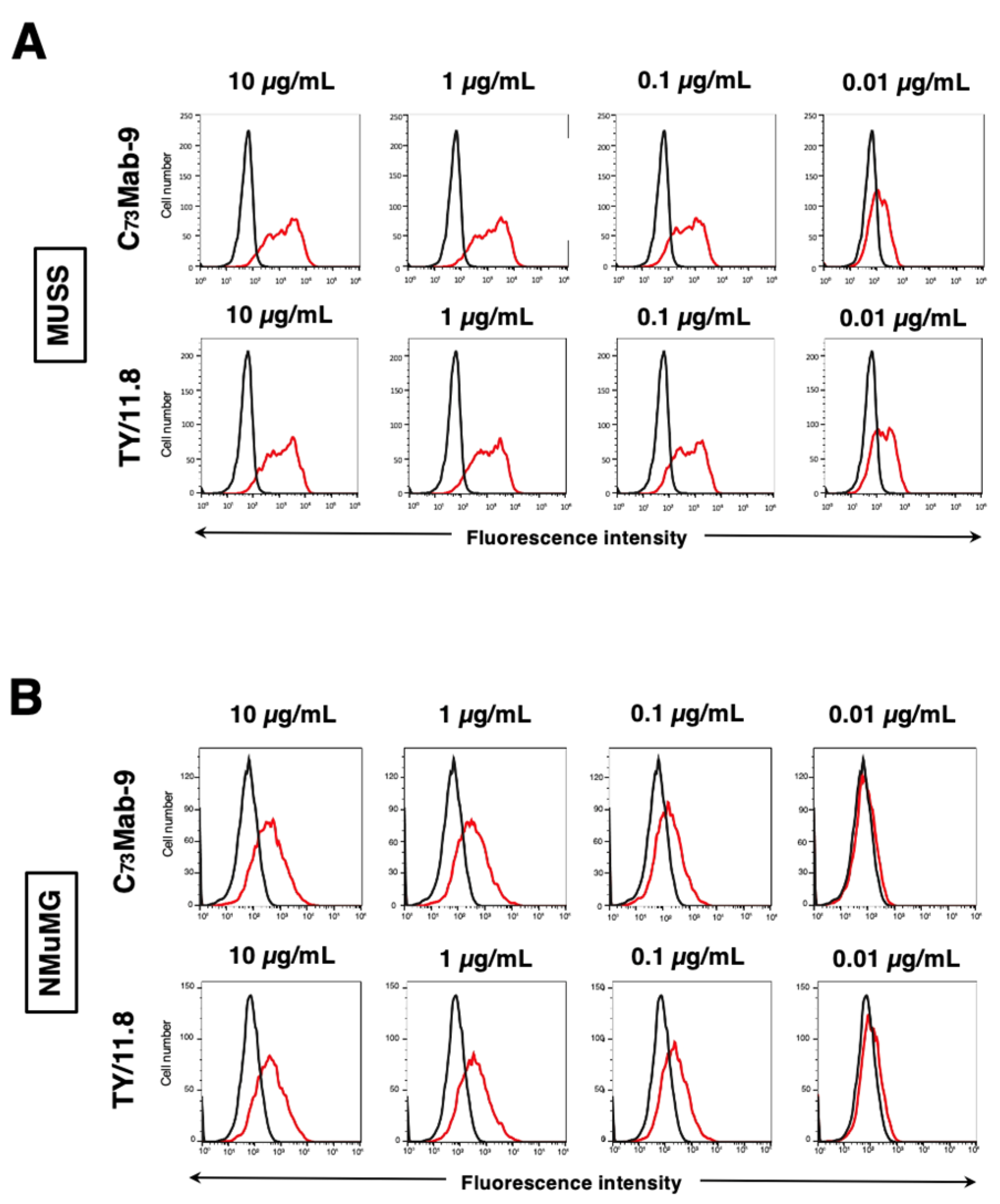

3.3. Evaluation of the Antibody Reactivity Against Endogenously mCD73-Expressing Cells Using Flow Cytometry

Next, further flow cytometric analysis was conducted using C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 against MUSS and NMuMG, which endogenously express mCD73. Results indicated that C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 recognized MUSS dose-dependently (

Figure 3A). Against another mCD73-expressing NMuMG cell line, C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 also recognized dose-dependently (

Figure 3B) with almost identical reactivity. Thus, C

73Mab-9 can detect endogenous mCD73 in flow cytometry.

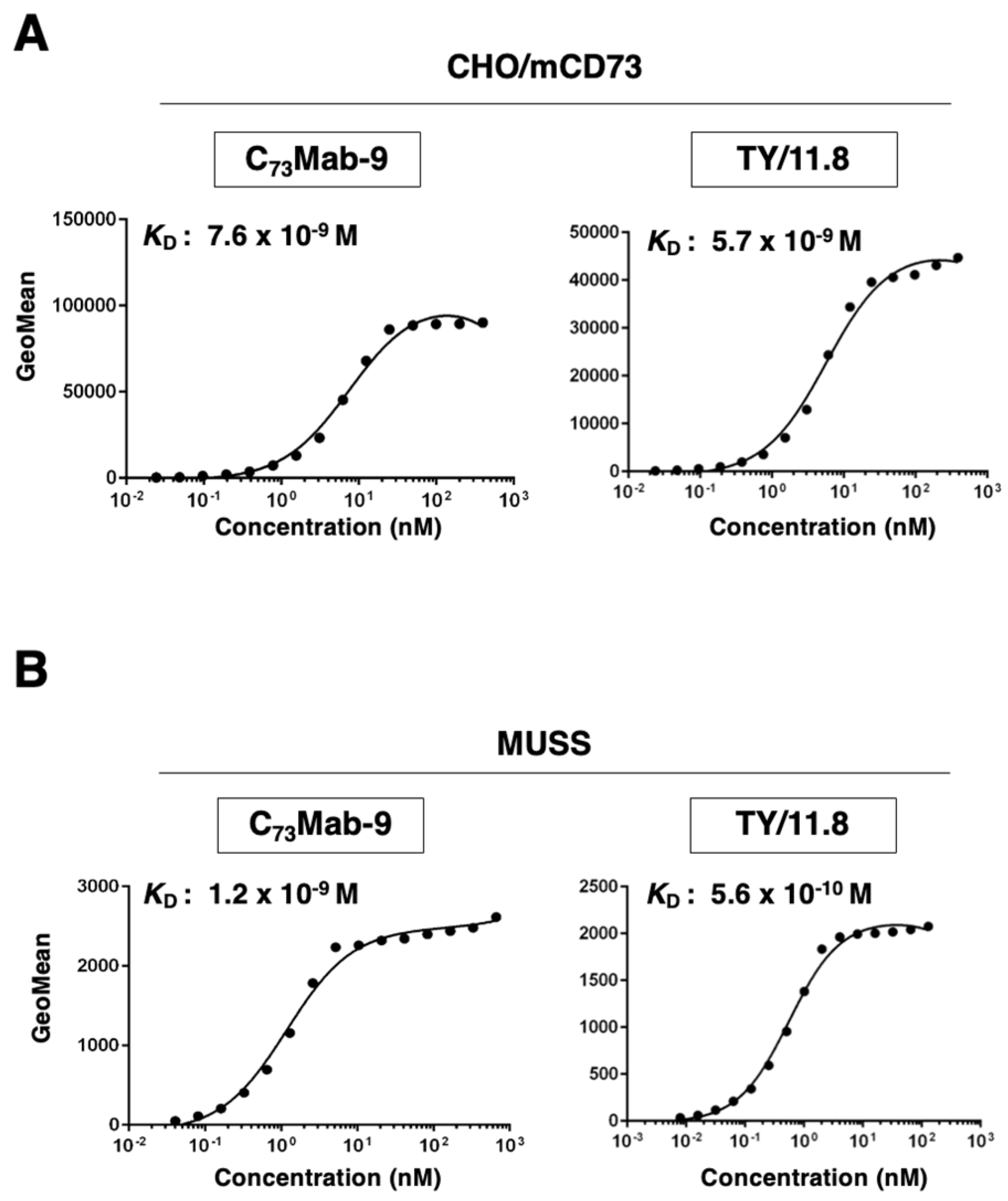

3.4. Calculation of The Apparent Binding Affinity Of Anti-mCD73 mAbs Using Flow Cytometry

The binding affinity of C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 was assessed with CHO/mCD73 using flow cytometry. The results indicated that the K

D values of C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 for CHO/mCD73 were 7.6×10

-9 M and 5.7×10

-9 M, respectively (

Figure 4A). Furthermore, the K

D values of C

73Mab-9 and TY/11.8 for MUSS were 1.2×10

-9 M and 5.6×10

-10 M, respectively (

Figure 4B). These results demonstrate that C

73Mab-9 can recognize mCD73 with high affinity to the cell surface mCD73.

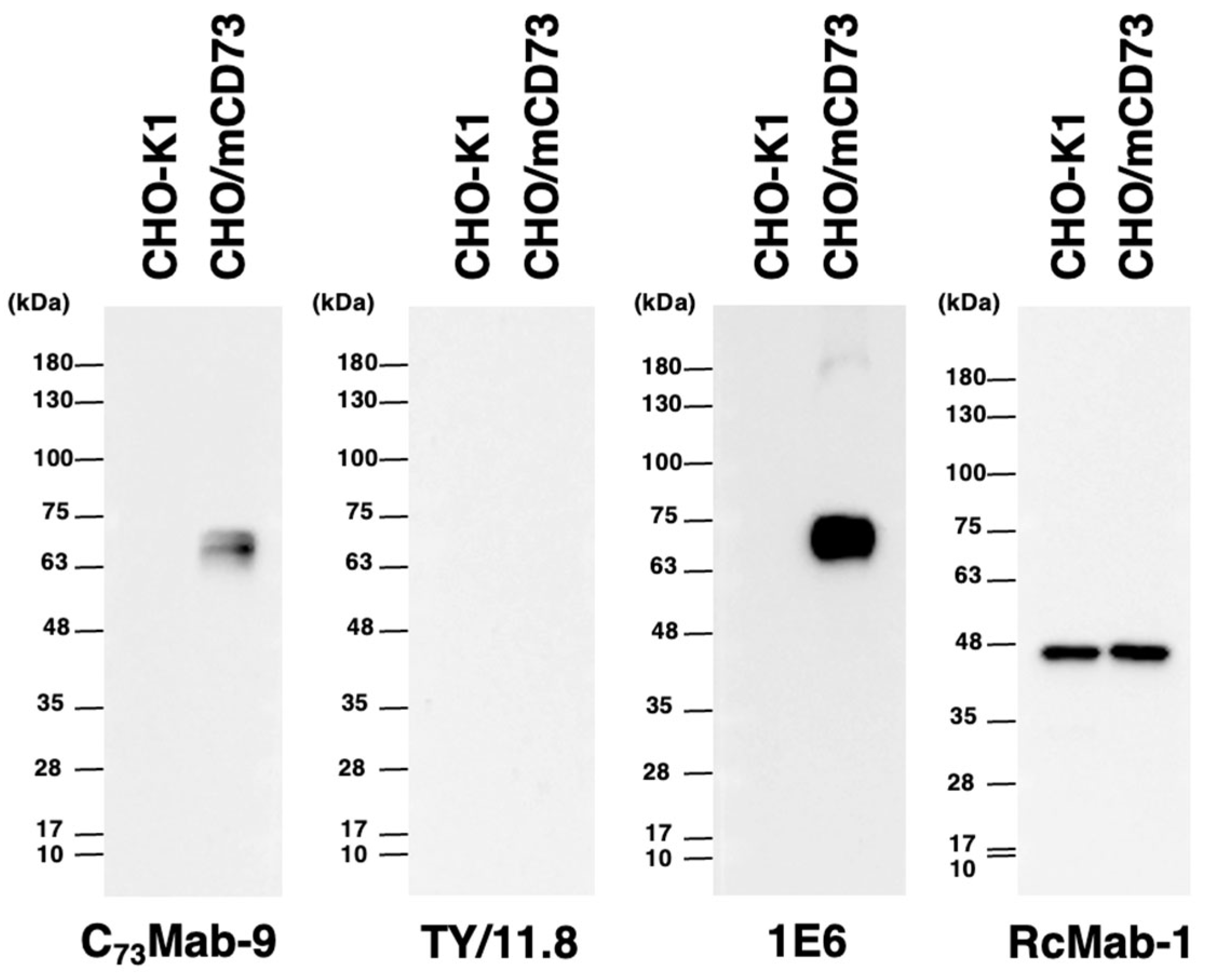

3.5. Western Blot Analyses Using Anti-mCD73 mAbs

We investigated whether C

73Mab-9 can be applied to western blot analysis by analyzing CHO-K1 and CHO/mCD73 cell lysates. The estimated molecular weight of the mCD73 protein is approximately 70,000. As shown in

Figure 5, C

73Mab-9 could detect mCD73 as the major band between 63 to 75 kDa in CHO/mCD73 cell lysates, while no band was detected in parental CHO-K1 cells. Another anti-mCD73 mAb, TY11.8, could not detect any band in CHO/mCD73 cell lysates. An anti-DYKDDDDK mAb (clone 1E6) was applied for positive control because mCD73 was FLAG-tagged in CHO/mCD73. An anti-IDH1 mAb (clone RcMab-1) was used for internal control. These results indicate that C

73Mab-9 can recognize denatured-mCD73 in mCD73-overexpressed cells in western blot analyses.

4. Discussion

Upregulation of CD73 and CD39 has been observed in tumors and immune cells not only under hypoxia but also in response to cytokines such as transforming growth factor-β and interleukins [

36,

37]. These secreted factors also concomitantly upregulate the A2AR expression. The high concentrations of ATP can be observed in the extracellular milieu of solid tumors [

38]. Moreover, it is well known that a wide variety of cytokines are released to TME by tumor cells and immune-related cells [

39,

40]. Thus, ADO production within tumors provides a complex mechanism for evading immune approaches. Interestingly, CD73 might act as a tumor promoter independent of ADO production. CD73 induces adhesiveness and invasiveness of tumors, and transactivation of receptor tyrosine kinases by binding extracellular matrix proteins and clustering on the cell surface, respectively [

41,

42,

43]. Simultaneous inhibition of CD73 and epidermal growth factor receptor significantly induces tumor cell death and suppresses migration of cancer cells [

44]. It is essential to know the epitope of mAb to predict its inhibitory effect on the target protein activity. Anti-CD73 mAb cocktail targeting two different epitopes potently inhibits tumor growth than the single treatment [

45]. We plan to identify the epitope of C

73Mab-9 to clarify whether it binds near the catalytic domain of mCD73, and whether it has an inhibitory effect on the catalytic activity of mCD73 in preclinical models.

CD73 correlates with the initiation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and cancer stemness in ovarian cancer [

46]. Also in hepatocellular carcinoma, CD73 upregulation and A2AR activation contribute to the induction of EMT, metastatic features, and cancer stem cell traits through PI3K/AKT signaling and SOX9 stabilization [

47,

48]. CD73 influences cancer progression not only by immune evasion but also by promoting malignant phenotypes. Moreover, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), a tumor stromal cell, highly express CD39 and CD73, which enable the production of extracellular ADO in cancers [

49,

50]. A high abundance of CAFs was associated with a worse prognosis in colorectal cancer patients [

50]. A2AR activation triggers the proliferation of CAFs, followed by tumor cell growth in non-small cell lung cancer [

51]. CD73-ADO-A2AR axis plays multiple roles in cancer malignancy in tumor tissues, and more detailed analysis may expand its potential as a therapeutic target for numerous cancers. C

73Mab-9 could be a helpful tool for evaluating mCD73-related biological responses in mouse models. Previously, we have successfully developed anti-mouse CD39 mAbs, clones C

39Mab-1 and C

39Mab-2, by the CBIS method [

52,

53]. These established mouse CD39 and CD73-targeting mAbs could significantly contribute to the analysis of the adenosine pathway.

CD73-targeted clinical studies have been conducted against solid tumors. Anti-CD73 mAbs, such as oleclumab (human mAb), CPI-006 (humanized mAb), BMS-986179 (hybrid IgG

1/IgG

2 antibody), and NZV930 (human mAb), have been used in clinical studies. Furthermore, CD73-targeting small molecules, including AB680 and LY3475070, have also been evaluated for solid tumors [

31]. In addition to the role in cancer progression, CD73 is a promising therapeutic target that antibodies and small-molecule compounds can target to block its function. Furthermore, more significant antimetastatic effects have been observed in CD73/A2AR dual blockade by anti-mCD73 mAbs and A2AR inhibitors than either single treatment in the mouse melanoma lung metastasis model [

54]. In future studies, we will investigate the antitumor efficacy of C

73Mab-9 in mouse models.

Author Contributions

Tomohiro Tanaka: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Tomoko Sakata: Investigation; Shiori Fujisawa: Investigation; Haruto Yamamoto: Investigation; Yu Kaneko: Investigation; Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization; Hiroyuki Suzuki: Writing – review and editing; Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Information

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP25am05210 Y.Kato (to Y.K.), JP25ama121008 (to Y.Kato), JP25ama221339 (to Y.Kato), and JP25bm1123027 (to Y.Kato), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 24K18268 (to T.T.) and 25K10553 (to Y.Kato).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Demaria, O.; Cornen, S.; Daëron, M.; et al. Harnessing innate immunity in cancer therapy. Nature 2019;574(7776): 45-56. [CrossRef]

- De Simone, M.; Arrigoni, A.; Rossetti, G.; et al. Transcriptional Landscape of Human Tissue Lymphocytes Unveils Uniqueness of Tumor-Infiltrating T Regulatory Cells. Immunity 2016;45(5): 1135-1147. [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, S.; Momoi, Y.; Nishikawa, H. Immunogenomic cancer evolution: A framework to understand cancer immunosuppression. Science Immunology 2025;10(105): eabo5570. [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Konig, M.F.; Pardoll, D.M.; et al. Cancer therapy with antibodies. Nat Rev Cancer 2024;24(6): 399-426.

- Höckel, M.; Vaupel, P. Tumor Hypoxia: Definitions and Current Clinical, Biologic, and Molecular Aspects. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2001;93(4): 266-276.

- Vaupel, P.; Mayer, A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews 2007;26(2): 225-239. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, E.B.; Giaccia, A.J. Hypoxic control of metastasis. Science 2016;352(6282): 175-180.

- Synnestvedt, K.; Furuta, G.T.; Comerford, K.M.; et al. Ecto-5′-nucleotidase (CD73) regulation by hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates permeability changes in intestinal epithelia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2002;110(7): 993-1002.

- Ohta, A.; Gorelik, E.; Prasad, S.J.; et al. A2A adenosine receptor protects tumors from antitumor T cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006;103(35): 13132-13137.

- Sitkovsky, M.V.; Lukashev, D.; Apasov, S.; et al. Physiological Control of Immune Response and Inflammatory Tissue Damage by Hypoxia-Inducible Factors and Adenosine A2A Receptors*. Annual Review of Immunology 2004;22(Volume 22, 2004): 657-682. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, H. 5′-Nucleotidase: molecular structure and functional aspects. Biochemical Journal 1992;285(2): 345-365. [CrossRef]

- Sträter, N. Ecto-5’-nucleotidase: Structure function relationships. Purinergic Signalling 2006;2(2): 343-350. [CrossRef]

- Mastelic-Gavillet, B.; Navarro Rodrigo, B.; Décombaz, L.; et al. Adenosine mediates functional and metabolic suppression of peripheral and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2019;7(1): 257.

- Lokshin, A.; Raskovalova, T.; Huang, X.; et al. Adenosine-Mediated Inhibition of the Cytotoxic Activity and Cytokine Production by Activated Natural Killer Cells. Cancer Research 2006;66(15): 7758-7765. [CrossRef]

- Raskovalova, T.; Huang, X.; Sitkovsky, M.; et al. Gs Protein-Coupled Adenosine Receptor Signaling and Lytic Function of Activated NK Cells1. The Journal of Immunology 2005;175(7): 4383-4391. [CrossRef]

- Forte, G.; Sorrentino, R.; Montinaro, A.; et al. Inhibition of CD73 improves B cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity in a mouse model of melanoma. J Immunol 2012;189(5): 2226-2233. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, A.; Bavaresco, L.; Wink, M.R.; et al. Indomethacin stimulates activity and expression of ecto-5'-nucleotidase/CD73 in glioma cell lines. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;569(1-2): 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Banerjee, A.; Xie, P.; et al. Pharmacological suppression of the OTUD4/CD73 proteolytic axis revives antitumor immunity against immune-suppressive breast cancers. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2024;134(10).

- Koivisto, M.K.; Tervahartiala, M.; Kenessey, I.; et al. Cell-type-specific CD73 expression is an independent prognostic factor in bladder cancer. Carcinogenesis 2018;40(1): 84-92. [CrossRef]

- Jacoberger-Foissac, C.; Cousineau, I.; Bareche, Y.; et al. CD73 Inhibits cGAS–STING and Cooperates with CD39 to Promote Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Immunology Research 2023;11(1): 56-71. [CrossRef]

- Montalbán del Barrio, I.; Penski, C.; Schlahsa, L.; et al. Adenosine-generating ovarian cancer cells attract myeloid cells which differentiate into adenosine-generating tumor associated macrophages – a self-amplifying, CD39- and CD73-dependent mechanism for tumor immune escape. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2016;4(1): 49.

- Giatromanolaki, A.; Kouroupi, M.; Pouliliou, S.; et al. Ectonucleotidase CD73 and CD39 expression in non-small cell lung cancer relates to hypoxia and immunosuppressive pathways. Life Sci 2020;259: 118389. [CrossRef]

- Loi, S.; Pommey, S.; Haibe-Kains, B.; et al. CD73 promotes anthracycline resistance and poor prognosis in triple negative breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013;110(27): 11091-11096. [CrossRef]

- Quezada, C.; Garrido, W.; Oyarzún, C.; et al. 5′-ectonucleotidase mediates multiple-drug resistance in glioblastoma multiforme cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2013;228(3): 602-608.

- Zarek, P.E.; Huang, C.-T.; Lutz, E.R.; et al. A2A receptor signaling promotes peripheral tolerance by inducing T-cell anergy and the generation of adaptive regulatory T cells. Blood 2008;111(1): 251-259. [CrossRef]

- Leone, R.D.; Sun, I.-M.; Oh, M.-H.; et al. Inhibition of the adenosine A2a receptor modulates expression of T cell coinhibitory receptors and improves effector function for enhanced checkpoint blockade and ACT in murine cancer models. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 2018;67(8): 1271-1284. [CrossRef]

- Ohta, A.; Kini, R.; Ohta, A.; et al. The development and immunosuppressive functions of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are under influence of the adenosine-A2A adenosine receptor pathway. Frontiers in Immunology 2012;3. [CrossRef]

- Nettersheim, F.S.; Brunel, S.; Sinkovits, R.S.; et al. PD-1 and CD73 on naive CD4(+) T cells synergistically limit responses to self. Nat Immunol 2025;26(1): 105-115. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.; Winzer, R.; Rissiek, A.; et al. CD73-mediated adenosine production by CD8 T cell-derived extracellular vesicles constitutes an intrinsic mechanism of immune suppression. Nature Communications 2021;12(1): 5911. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. CD73 in small extracellular vesicles derived from HNSCC defines tumour-associated immunosuppression mediated by macrophages in the microenvironment. Journal of Extracellular Vesicles 2022;11(5): e12218. [CrossRef]

- Allard, B.; Allard, D.; Buisseret, L.; Stagg, J. The adenosine pathway in immuno-oncology. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2020;17(10): 611-629.

- Takei, J.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; et al. A defucosylated anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibody 13-mG(2a)-f exerts antitumor effects in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Rep 2020;24: 100801. [CrossRef]

- Takei, J.; Asano, T.; Nanamiya, R.; et al. Development of Anti-human T Cell Immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM Domains (TIGIT) Monoclonal Antibodies for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2021;40(2): 71-75. [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Establishment of C(20)Mab-11, a novel anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, for the detection of B cells. Oncol Lett 2020;20(2): 1961-1967.

- Tanaka, T.; Kaneko, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; et al. Development of a novel anti-erythropoietin-producing hepatocellular receptor B6 monoclonal antibody Eb(6)Mab-3 for flow cytometry. Biochem Biophys Rep 2025;41: 101960. [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Ibarra, L.R.; Mora-García, M.d.L.; García-Rocha, R.; et al. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Derived from Normal Cervix and Cervical Cancer Tumors Increase CD73 Expression in Cervical Cancer Cells Through TGF-β1 Production. Stem Cells and Development 2019;28(7): 477-488.

- Allard, B.; Longhi, M.S.; Robson, S.C.; Stagg, J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: Novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol Rev 2017;276(1): 121-144. [CrossRef]

- Pellegatti, P.; Raffaghello, L.; Bianchi, G.; et al. Increased level of extracellular ATP at tumor sites: in vivo imaging with plasma membrane luciferase. PLoS One 2008;3(7): e2599. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Nisar, S.; Maacha, S.; et al. Cytokine-chemokine network driven metastasis in esophageal cancer; promising avenue for targeted therapy. Mol Cancer 2021;20(1): 2. [CrossRef]

- Baghy, K.; Ladányi, A.; Reszegi, A.; Kovalszky, I. Insights into the Tumor Microenvironment-Components, Functions and Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24(24).

- Sadej, R.; Skladanowski, A.C. Dual, enzymatic and non-enzymatic, function of ecto-5'-nucleotidase (eN, CD73) in migration and invasion of A375 melanoma cells. Acta Biochim Pol 2012;59(4): 647-652. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.W.; Wang, H.P.; Lin, F.; et al. CD73 promotes proliferation and migration of human cervical cancer cells independent of its enzyme activity. BMC Cancer 2017;17(1): 135. [CrossRef]

- Terp, M.G.; Olesen, K.A.; Arnspang, E.C.; et al. Anti-Human CD73 Monoclonal Antibody Inhibits Metastasis Formation in Human Breast Cancer by Inducing Clustering and Internalization of CD73 Expressed on the Surface of Cancer Cells. The Journal of Immunology 2013;191(8): 4165-4173. [CrossRef]

- Ardeshiri, K.; Hassannia, H.; Ghalamfarsa, G.; Jafary, H.; Jadidi, F. Simultaneous blockade of the CD73/EGFR axis inhibits tumor growth. IUBMB Life 2025;77(1): e2933.

- Xu, J.G.; Chen, S.; He, Y.; et al. An antibody cocktail targeting two different CD73 epitopes enhances enzyme inhibition and tumor control. Nat Commun 2024;15(1): 10872. [CrossRef]

- Lupia, M.; Angiolini, F.; Bertalot, G.; et al. CD73 Regulates Stemness and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Ovarian Cancer-Initiating Cells. Stem Cell Reports 2018;10(4): 1412-1425. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Shen, M.N.; Hu, B.; et al. CD73 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression and metastasis via activating PI3K/AKT signaling by inducing Rap1-mediated membrane localization of P110β and predicts poor prognosis. J Hematol Oncol 2019;12(1): 37. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Hu, B.; Tang, W.G.; et al. CD73 sustained cancer-stem-cell traits by promoting SOX9 expression and stability in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hematol Oncol 2020;13(1): 11. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Kieffer, Y.; Scholer-Dahirel, A.; et al. Fibroblast Heterogeneity and Immunosuppressive Environment in Human Breast Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33(3): 463-479.e410. [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Guo, G.; Huang, L.; et al. CD73 on cancer-associated fibroblasts enhanced by the A(2B)-mediated feedforward circuit enforces an immune checkpoint. Nat Commun 2020;11(1): 515. [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla-Varela, M.; Luddy, K.; Noyes, D.; et al. Antagonism of adenosine A2A receptor expressed by lung adenocarcinoma tumor cells and cancer associated fibroblasts inhibits their growth. Cancer Biol Ther 2013;14(9): 860-868. [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Suzuki, H.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Development of a Sensitive Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody (C(39)Mab-1) for Flow Cytometry and Western Blot Analyses. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2024;43(1): 24-31. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kudo, Y.; et al. A Rat Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2023;42(6): 203-208. [CrossRef]

- Young, A.; Ngiow, S.F.; Barkauskas, D.S.; et al. Co-inhibition of CD73 and A2AR Adenosine Signaling Improves Anti-tumor Immune Responses. Cancer Cell 2016;30(3): 391-403. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).