1. Introduction

Circles of support for people with disabilities represent an innovative strategy for building social support networks, aimed at assisting individuals with disabilities in their daily lives and promoting social integration. This is a method that combines formal and informal elements, engaging the local community. Circles of support help individuals with disabilities to lead more independent and socially integrated lives, although their implementation may face certain organizational and societal challenges.

Circles of support are established around a person with a disability, connecting formal support (e.g., doctors, therapists) with informal support (e.g., family members, friends, neighbours). The aim is to create a personalized support system that responds to the specific needs and preferences of the individual with a disability [

1,

2]. Circles of support actively engage the local community, thus fostering social inclusion and improving the well-being of people with disabilities [

3,

4]. Collaboration with families and communities is crucial for the effective functioning of these circles [

5].

In recent years, the model of circles of support has gained significant importance in shaping public policy in Poland, becoming a symbol of a new approach to community-based support for people with disabilities. As a response to the challenges of deinstitutionalization and the need for the development of individualized, integrated forms of assistance, circles of support have been included in several strategic documents, including the Strategy for People with Disabilities 2021–2030 and the Strategy for the Development of Social Services until 2035. Their role has been further reinforced by their recognition as a model social service within the framework of social service centres and by their planned inclusion in the amended Social Assistance Act. These efforts culminate in the announced systemic scaling project for 2025–2029, aiming at the permanent integration of the model into the structure of local social policies.

Although, at the systemic level, circles of support have been recognized as a key element in the deinstitutionalization process of support for people with disabilities in Poland, there is still a lack of feasibility analysis regarding their implementation through social service centres in a way that enables genuine widespread adoption. A methodology that could serve as a catalyst for the development of community-based services in Poland remains underdeveloped. This article aims to address that gap.

The objective of this article is to conduct a multifaceted feasibility analysis for the implementation of circles of support for people with disabilities in Poland, considering financial, legal, and staff preparation dimensions.

We employ various research methods, including legal analysis, cost analysis, and quantitative research involving staff from social service centres (SSC) and social assistance centres (SAC) regarding the possibilities for implementing circles of support. The subject of evaluation is the social service model of circles of support developed under the project "Circles of Support — from Concept to Dissemination," financed by the State Fund for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons in Poland. This article has been prepared within the framework of that project. The model development process was based on an action research methodology, in which researchers accompanied the process of developing model solutions.

The article is organized into several sections. The initial parts provide a synthetic overview of the idea of circles of support, the history of the model in Poland, and its placement within the broader context of disability policy in Poland. This section concludes with a description of circles of support as a service implemented through SSC, which in the empirical section is subjected to a feasibility analysis. Subsequent sections present the applied methods and the results of the conducted analyses. The article concludes with a summary.

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Circles of Support – Development and Theoretical Foundations of the Method

The model of circles of support for persons with disabilities originates from interdisciplinary concepts developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, primarily in Canada, the United States, and Scandinavian countries. Its theoretical foundations are rooted in social psychology, sociology, and special education – particularly in theories of social capital and the role of support networks in social integration [

6].

The first formal descriptions and implementations of circles of support were developed by Jack Pearpoint and Marsha Forest as part of the Inclusion Press project in Toronto during the 1980s [

7]. Initially, the model was used mainly in educational settings, serving to build supportive social networks around students with disabilities. Known as the "Circle of Friends", it was based on the assumption that every individual, regardless of the degree of disability, can and should be part of a social relationship network.

The circles of support model has strong theoretical foundations, combining social, cultural, and institutional elements. A key theoretical framework is the social model of disability, which views disability as the result of societal and systemic barriers rather than individual dysfunction [

8,

9]. In this perspective, the solution lies not in providing care, but in creating social environments that respond to diverse needs – precisely as envisioned by circles of support.

Another important basis is the concept of social inclusion, especially in the form promoted by contemporary EU educational and social strategies [

10,

11,

12]. The model assumes active participation of persons with disabilities in social life and supports their social roles according to their preferences and capabilities. Circles of support meet these requirements by creating inclusive, sustainable relationships between individuals and their environments.

The third pillar of the model is empowerment theory, which in its modern interpretation combines psychological and social approaches aimed at strengthening individuals' sense of agency, self-determination, and control over their own lives [

13,

14,

15]. Circles of support are not a form of substitute care but a mechanism that enables persons with disabilities to make decisions with social support.

Finally, the theory of social capital plays a critical role in the circles model, emphasizing the importance of networks of relationships and trust as both individual and communal resources [

6,

16,

17]. Building and strengthening social capital around a person with a disability leads not only to an improvement in their quality of life but also to the integration and development of entire local communities.

The multidimensional positive effects of implementing circles of support have also been demonstrated in numerous studies. Circles help persons with disabilities live more independently and improve social support indicators while promoting social integration and well-being [

1,

3,

5]. They shift control over the identification and management of support needs from institutions to individuals, allowing persons with disabilities greater control over their lives [

1,

2]. Circles of support also provide crucial emotional support for coping with challenges related to disability [

2,

5] and often combine formal and informal support, engaging a variety of people and institutions to meet the individual needs of persons with disabilities [

1,

18].

2.2. Development of the Circles of Support Model in Poland

In Poland, the first attempts to adapt the circles of support model appeared in the 1990s, mainly within non-governmental organizations working for persons with intellectual disabilities. Initially, they were implemented as pilot projects, often funded by international sources. A breakthrough in the development of the model came with its inclusion in the deinstitutionalization process of social services, which gained momentum after Poland's accession to the European Union and the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2012.

In recent years, with the growing emphasis on the personalization of social services and the development of community-based support, the circles of support model has gained importance as an effective tool for social integration. The establishment of social service centres (SSC) in 2019, created by transforming social assistance centres (SAC - the primary units responsible for providing support within the public social assistance system), opened new opportunities for the systemic implementation of this model within local social policies.

The first circles of support started operating in Warsaw in 2015 under the Warsaw Forum for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities at the BORIS Association. The next stage involved implementing the "Safe Future" model in eight communities: Jarosław, Nidzica, Biskupiec, Ostróda, Suwałki, Elbląg, Gdańsk, and Goleniów. The project was implemented by the Polish Association for Persons with Intellectual Disabilities (PSONI) and its partners. In 2021, additional PSONI branches in Bytom, Tarnów, and Zgierz joined the initiative. In subsequent years, the circles of support methodology began to be implemented in community self-help homes for persons with disabilities, including in Warsaw, Przemyśl, Żelazna Góra, Gdynia, and Zamość. The latest environments where the methodology is being developed include primary schools – both special and vocational preparation schools. Examples include Special Primary School No. 26 in Gdańsk, Special School Complex No. 17 in Gdynia, the rehabilitation-education center, and non-public institutions run by PSONI branches in Jabłonka and Elbląg.

2.3. Support Circles in Public Policy in Poland

In recent years, the support circles model has become one of the key elements in the strategy for the development of social services in Poland. Its increasing application and growing importance are reflected both in strategic documents and in proposed legislative and institutional solutions.

A turning point for the institutionalization of the support circles model in public policy was the adoption of the Strategy for People with Disabilities 2021–2030 (resolution of February 16, 2021). This document includes support circles as a tool to ensure the sustainability of community-based support for individuals with intellectual disabilities, alongside other forms of support facilitating independent living. The Strategy acknowledges the need for combining formal and informal resources in the individual’s environment, which aligns with the basic assumptions of the support circles model.

The support circles model was also included in the Strategy for the Development of Social Services until 2035, prepared by the Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy. This strategy treats support circles as an innovative and individualized form of organizing social support in local communities, addressing the need for deinstitutionalization and increasing the independence of people with disabilities.

Since 2024, support circles have been increasingly viewed as a model social service implemented by SSC with significant potential for scaling. This model is based on the provisions of the 2019 Act on the Implementation of Social Services by SSC, enabling its implementation at the local level as part of the Program for Social Services. This approach strengthens support circles as a tool of local government and community policy.

The team working on the reform of the Social Assistance Act included the support circles model in the planned legislative changes. Proposed amendments include the introduction of a definition of support circles into the Act, allowing for their implementation as a service benefit within the social assistance system, on par with other forms of community-based support, such as caregiving services or personal assistance.

From 2025 to 2029, a systemic project is planned to scale the support circles model nationwide. This project, co-financed by European and national funds, aims to implement support circles in at least several dozen municipalities, and to develop quality standards, training tools, and mechanisms for monitoring the effects of the service.

The process of expanding the significance of support circles in public policy in Poland can be described as an evolution from a grassroots initiative to a systemic tool. The integration of support circles into strategic documents, legislation, and institutional practice (SSC, community-based self-help centres, schools) is evidence of their growing role in the transformation of social services. This model aligns with the long-term direction of deinstitutionalization and strengthening local support systems, in line with the principles of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

2.4. Support Circles Service in Social Service Centers in Poland

The circles of support model is an environment-and person-centred support system for individuals with disabilities, aiming to enable them to live independently, with dignity, and safely within their local community, in accordance with the provisions of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Art. 19). The model involves launching four integrated support pathways:

Person-Centred Planning. The person with an disability is at the heart of the process, with their needs, dreams, potential, and resources in focus. Support is individually planned, involving the person themselves, their family, and allies, and the future plan is a living document, adjusted to changing circumstances.

Building a Personal Support Network and Integration into the Local Community. The support circle consists of people from the individual’s surroundings—family, friends, neighbours, volunteers, professionals (e.g., personal assistants, social workers, therapists), as well as people from the local community (e.g., shop assistants, neighbourhood police officers). Together, they support the individual in daily life, skill development, pursuing passions, and ensuring a secure future.

Personalized and Coordinated Social Services (e.g., personal assistance, supported housing, supported employment, rehabilitation). This model assumes that every person, regardless of their degree of dependence, has the right to self-determination and participation in social life. Support is “tailored” to individual needs, with the goal of staying within the person’s environment and utilizing publicly available services and facilities.

Strengthening Families of People with Disabilities. This includes gradual planning and securing the future—housing, financial, and social—by creating self-help groups for families, where they share experiences, provide emotional and practical support, and participate together in actions aimed at making the local community more inclusive for people with disabilities.

The impact of support circles on the quality of life for individuals with disabilities focuses on integrating the work of various specialists in supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities through a key worker (in the case of SSC, this is a dedicated position). This is reflected in the continuously developed life plan for the individual. From a methodological perspective, the result is increasing empowerment, meaning the individual’s real influence over their life. A key channel for influencing quality of life is the animation and support of the social network around the individual (the "circle") by the key worker. The measure of change is the increase in the number of people with whom the individual maintains relationships of various types (emotional, friendship, mutual service exchange), thus expanding their social capital.

The activities of support circles, which should be synergistically strengthened by other social services provided by SSC (e.g., respite care, legal advice, psychological support), as well as activities within the realm of organizing the local community (people with disabilities and their circles become part of the broader life of the local community), lead to an increase in participation in local community life—true social inclusion.

At the institutional level, the embedding and safe implementation of the model requires the integration by SSC of the formal system (facilities supporting people with disabilities and other social and health policy entities) and the informal system (family, social surroundings, local community), which is managed by the coordinator of support circles. It is also crucial to combine permanent actions carried out by a specially established SSC program unit, the Centre for Support Circles, which serves as a substantive and supervisory backup for activities carried out by other entities providing the social service. Experienced staff at the Centre for Support Circles conduct training, offer advice, and supervise the implementation of the service. Additionally, it is necessary to develop regulations for commissioning the social service "support circles" to social economy entities, and forms of cooperation with the Centre for Support Circles operating within SSC. Contracting the service requires setting measurable goals (the number of circles and supported individuals) and numerically defined tasks (number of workshops, meetings, hours of companionship). A financial calculation and a time horizon for the service implementation (preferably three years) are also essential elements.

3. Materials and Methods

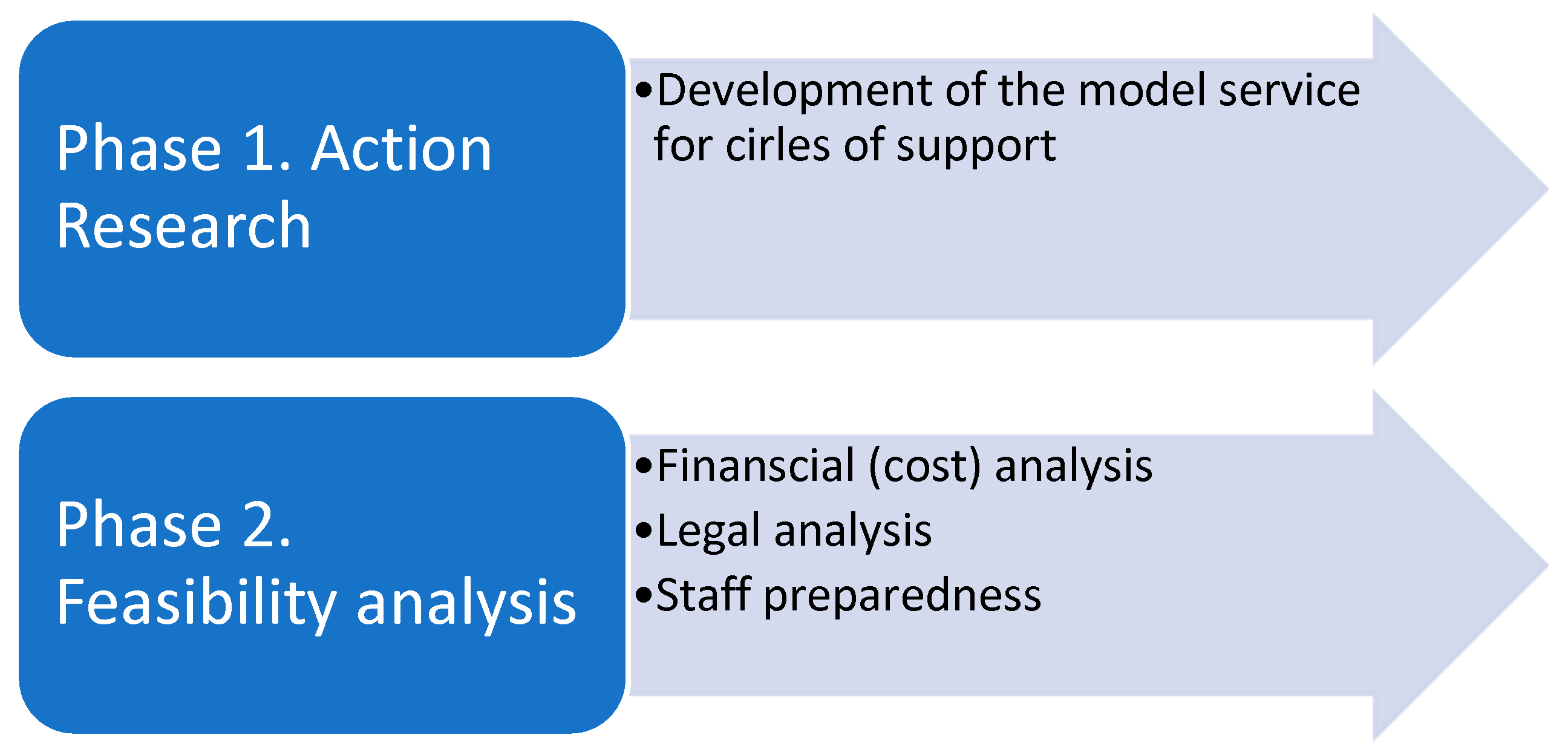

The research process was carried out in several stages

. The first stage focused on developing the support circles service model implemented in SSC. Developing the model was part of action research, where the authors of the article supported two selected SSC centres: in Goleniow and Milanówek, in the process of developing the model service. The SSC in Goleniow serves a medium-sized city (34,000 residents) in the north-western part of Poland, and is already at an advanced stage of implementing the support circles model. The SSC in Milanówek serves a small but very wealthy town near the capital, and the implementation of support circles is still in the preparatory phase there. The comparison of these two perspectives—associated with different experiences in implementing support circles and the varying situations of the municipalities in which they operate—allows for the verification of mutual assumptions. The research is in line with the principles of action research, which combines theory with practice, focusing on real problems and engaging participants in the research process. Key assumptions of this method include cooperation, reflection, and introducing changes through action, making it an effective tool for solving problems in various social and organizational contexts (e.g., [

19,

20,

21]). The researchers participated in meetings and consultations, both conducted in the analysed institutions and in local communities. They accompanied the process of developing the model service at every stage in the SSC in Milanówek and Goleniow.

The next step of the research was the feasibility analysis of the developed model service, which included financial, legal, and staff preparedness analyses. The legal analysis reviewed key legal acts regulating the operation of SSC regarding the possibility of implementing support circles. The financial analysis involved calculating the costs of implementing the service in various variants, as well as the costs of inaction.

The staff preparedness was assessed based on the results of a nationwide survey conducted on a representative sample of social assistance centres (SAC) and social services centres (SSC) using the CATI (Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing) method. The survey was conducted in each of the 16 provinces in Poland. Respondents were representatives of the management staff of SAC and SSC: directors or managers of the units, as well as deputy directors or managers. The effective sample size was n=500 entities from across the country, representing over 20% of the institutions mentioned above in Poland. A random sampling method was applied, with divisions into the following strata: provinces (1) and types of municipalities (2): rural municipality (a), urban-rural municipality (b), urban municipality (c), city with county rights (d). The sampling frame was the nationwide database of SAC/SSC.

The schematic representation of the research process is illustrated in the diagram below.

Diagram 1.

Research design. Source: own elaboration.

Diagram 1.

Research design. Source: own elaboration.

3. Results

The results of the feasibility analysis of the support circles model were carried out on three levels: legal analysis, financial (cost) analysis, and the level of staff preparedness.

3.1. Legal Analysis

The aim of the legal analysis was to identify the legal foundations that enable the provision of support circle services for individuals with disabilities as a comprehensive service delivered by SSC, as well as the methods of delivering this service within the municipality. In order to conduct this analysis, it was necessary to place the service within the catalogue of legal guarantees granted to individuals with disabilities, particularly those with intellectual disabilities. This also required characterizing the legal basis for the functioning of SSC and the principles of providing social services, as well as defining the concept of these services. The analysis covered the following legal acts:

The Constitution of the Republic of Poland of April 2, 1997 (Journal of Laws No. 78, item 483, as amended),

The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities adopted in New York on December 13, 2006 (Journal of Laws 2012, item 1169, as amended),

The Act of August 19, 1994 on Mental Health Protection (Journal of Laws 2024, item 917),

The Act of August 27, 1997 on Vocational and Social Rehabilitation and Employment of Disabled Persons (Journal of Laws 2024, item 44, as amended),

The Act of March 12, 2004 on Social Assistance (Journal of Laws 2024, item 1283, as amended),

The Act of July 19, 2019 on the Provision of Social Services by Social Services Centres (Journal of Laws 2019, item 1818).

In light of the legal analyses, the support circle model is considered a comprehensive social service aimed at organizing a permanent and personalized support system for individuals with intellectual disabilities – both in formal (professionals) and informal (family, neighbours, volunteers) dimensions. The support circle service fulfils the constitutional obligation of the state to support individuals with disabilities (Article 69 of the Polish Constitution) and is fully supported by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ratified by Poland in 2012). It specifically aligns with provisions concerning the right to independent living and social inclusion (Article 19 of the Convention) and the right to respect for family life, education, employment, and support in the local community.

Placing the actions of support circles within the context of SSC, it should be noted that according to the definition in Article 2 of the Act of July 19, 2019, on the Provision of Social Services by Social Services Centres (the so-called SSC Act), it is an immaterial action focused on directly supporting an individual to meet the needs of an individual or social group. This model meets all statutory criteria applicable to social services, including: (1) achieving goals in the area of supporting individuals with disabilities, social reintegration, and civic activity; (2) being based on actions resulting from laws such as the Social Assistance Act, the Mental Health Protection Act, the Vocational and Social Rehabilitation and Employment Act, and the Public Health Act; (3) being incorporated into the local Social Services Program, adopted as a local legal act.

As a new type of organizational unit within a municipality, the SSC has a statutory competence to initiate, implement, and coordinate social services, including innovative forms of support. Under Article 7(1) of the SSC Act, the centre may act as a program implementer, and services may be provided by: SSC employees, other organizational units of the municipality, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), or entities selected through public procurement procedures. This means that the implementation of support circles can be entrusted to NGOs, carried out in a hybrid model, or conducted independently by SSC – in line with the principles of subsidiarity and efficiency.

According to the SSC Act, the legal feasibility of the support circle model requires: (1) a needs and potential assessment of the local community conducted by SSC; (2) inclusion of the service in the local Social Services Program, adopted by the municipal council; (3) securing financing (from local resources, public funds, or partnerships); (4) selecting the appropriate form of implementation: independently by SSC or through an external partner. As part of this procedure, SSC is obliged to monitor, qualify participants, create individualized support plans, and evaluate the results of the service.

In conclusion, the support circle model is fully legally feasible as a social service within the meaning of Polish law, provided that the formal requirements of the local implementation procedure are met. The current regulations – both statutory and those derived from strategic documents (such as the Strategy for Persons with Disabilities 2021–2030) – not only allow but actually recommend the implementation of this model, especially in the context of deinstitutionalization and the development of local community-based support systems.

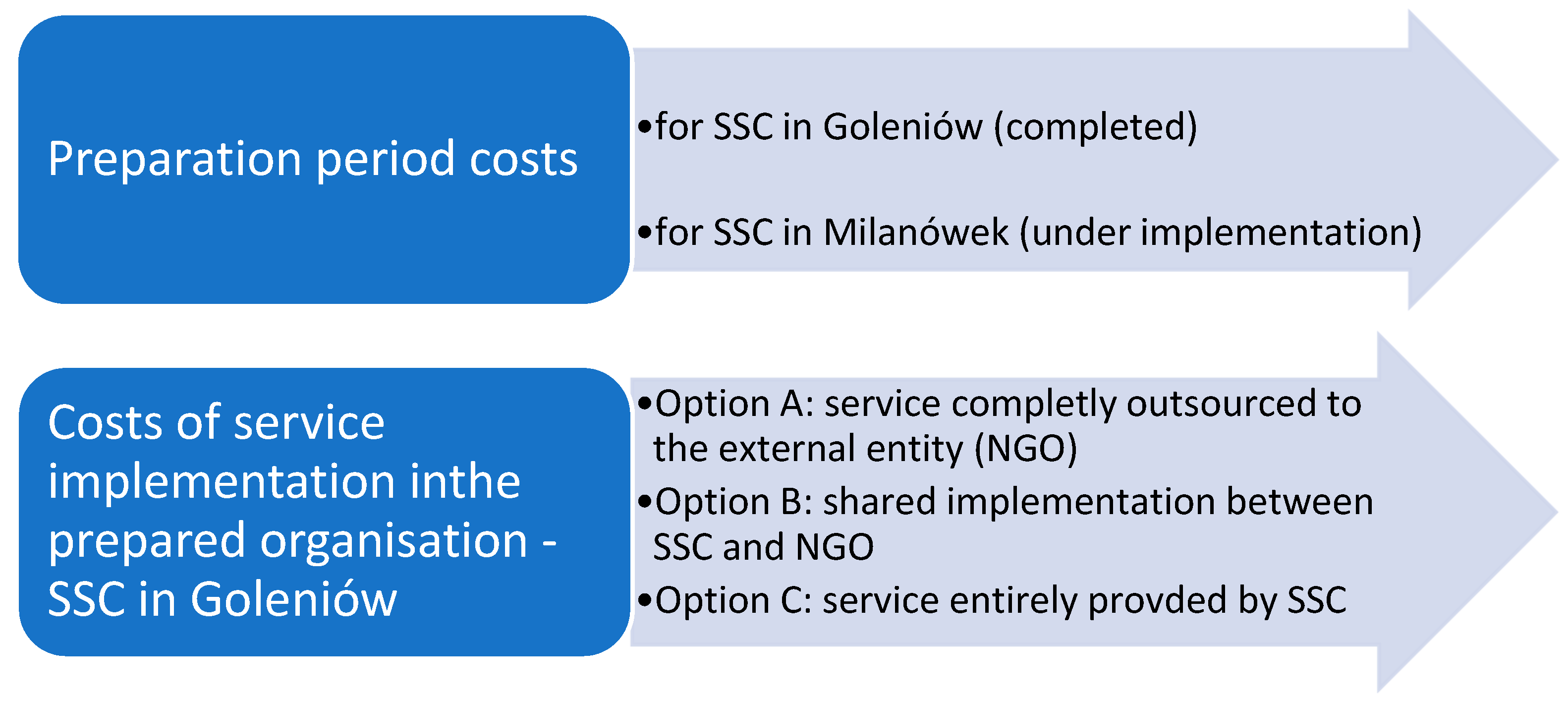

3.2. Financial (Cost) Analysis

As part of the cost analysis, the focus was placed on a comprehensive analysis of the costs and methods of financing the implementation of the support circle service in the following options, presented in the diagram below:

Diagram 2.

Option of Financial AnalysisSource: own elaboration.

Diagram 2.

Option of Financial AnalysisSource: own elaboration.

The analysis covered all costs of service implementation (personnel, material) that enabled its optimal and rational realization. Below are the results of the cost analysis, broken down into the categories presented in the diagram above.

3.2.1. Preparation Period Costs - Investment in Quality and Sustainability

The costs of implementing the service during the preparatory phase (including training, mentoring and support for employees, promotional costs, salaries, initial meetings with potential participants and their families) are a necessary investment enabling the creation of a sustainable and competent support system. The analysis shows that the cost of preparing one participant for support varies depending on the model and local conditions.

In the SSC in Goleniow, the real costs of the preparatory phase range from 13,060 PLN to 19,190 PLN per participant per year, which translates to monthly costs of 1,088 PLN to 1,600 PLN depending on the implementation option. Goleniow has already completed the employee preparation stage, making it a good example of an organization with an experienced and trained staff.

For SSC in Milanówek, however, the costs of the preparatory phase are higher.The higher estimates result from a larger number of employees involved in the training process, which amounts to 4,698 PLN per participant per month. Currently, in Milanowek, the preparatory phase lasts for 6 months, for which the costs have been calculated. After the preparatory phase is completed, the average monthly costs may decrease, most likely due to the higher intensity of costs in the first months of the preparatory phase. Effective preparation of staff, infrastructure, and the social environment significantly impacts the later quality, stability, and acceptance of the service in the local community. The example of Milanowek is a good illustration of how costs evolve for organizations with less experience that are starting the implementation of the support circles service from scratch.

3.2.1. Comparison of Options for the Implementation of the Circles of Support Service

The model of circles of support, which is an individualized form of community-based support for people with disabilities, can be implemented in three basic organizational options. The choice of option depends on local institutional conditions, availability of staff, and the maturity of the social sector. The differences relate not only to the organization of implementation but also to the level of institutional control, service stability, and cost-effectiveness.

The first model analysed – option A – involves fully outsourcing the implementation of the service to a non-governmental organization. In this case, SSC only acts as the commissioner and supervisor, without operational involvement in building and managing the support circles. This option allows for quick implementation of the service, especially in situations where there are no internal organizational or staffing resources. However, it also comes with limited oversight of the quality of actions and the risk of service interruption once external funding ends. The annual cost per participant in this option is approximately 9,900 PLN, but when accounting for the full hourly demand (20 hours of support per month), it can increase to 17,100 PLN.

The second model – option B – is a hybrid solution, where the service is provided simultaneously by SSC employees and a non-governmental organization. This allows for flexible combination of competencies, better use of local resources, and development of cross-sectoral cooperation. However, this model requires clear rules for role division, standardization of activities, and an effective coordination mechanism. The annual cost of the service in this model is 10,377 PLN per participant and remains favourable in terms of the quality and sustainability of the support provided.

Option C – involves the full implementation of the service by SSC. This model ensures the highest level of institutional control over the quality and coherence of the support circles with the local social services strategy. It also contributes to their sustainability after the completion of projects funded from external sources. However, it requires appropriately prepared staff and stable organizational resources. The annual cost of the service in this case is 10,594 PLN per participant.

A detailed comparison of the options is presented in the table below.

Table 1.

Comparison of three options for implementing the circle of support service.

Table 1.

Comparison of three options for implementing the circle of support service.

| Option |

Annual cost per participant1

|

Characteristics |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

| A - implementation by NGOs |

PLN 9,900 (at 10 hrs/month), up to PLN 17,100 (at 20 hrs/month) |

Service completely outsourced to an external entity (NGO) |

Relieve the burden on SSC staff

Rapid implementation in the absence of in-house resources |

Less control over quality

Risk of interruption after funding ends |

| B - mixed model (SSC + NGO) |

PLN 10,377 |

Shared implementation between SSC and NGOs |

Flexibility

Competency development of SSC and NGOs

Cost effectiveness |

Requires good coordination

Needs trust and clear division of roles |

| C - implementation by SSC |

PLN 10,594 |

Service entirely provided by SSC |

Full control over quality

Durability after project completion |

High staffing requirements

Risk of overloading employees |

All three options of implementing the support circles are legally permissible and comparable in terms of unit costs, which range from approximately 10,000 to 10,600 PLN per year per participant. The choice of a specific solution should be based on an analysis of local resources, the level of institutional development, and community expectations. The hybrid model (option B) can be considered the most flexible and sustainable, while option C guarantees the highest stability and integration with local social policy. On the other hand, option A works well in situations where the local government lacks appropriate staffing and organizational resources, but a social partner can provide the necessary service standard.

As part of the cost analysis, an economic efficiency analysis of the support circles model was also conducted through a basic simulation of the costs of not implementing the model. From the perspective of social policy, abandoning the implementation of the support circles model generates significantly higher costs in the long term. The cost of supporting a person with intellectual disabilities in Polish society is approximately 53,000 PLN per year, which is more than five times higher than in the support circles. Considering the entire lifespan of a person with intellectual disabilities, the cost difference could exceed 1 million PLN per person, assuming that at the time of the death of the parents/caregivers (on average around the age of 49), it is the turning point when the circles begin to operate or the person is placed in a social care home.

The financial analysis also identified potential financial risks. The first is dependence on subsidies. The main source of revenue is public grants and subsidies, which carry the risk of reduction in the following years. The second category of risk relates to the underutilization of participant potential. There may be low interest in the service in the early stages of implementation due to unfamiliarity with the topic of support circles. This requires intensive promotional and educational activities. The last key risk concerns the increase in operational costs. Expenses such as salary increases or increased demand for transportation may lead to higher operational costs.

In conclusion, the support circles model is financially feasible and has significant social potential. Proper cost management and diversified funding sources can ensure long-term sustainability and expansion of activities.

3.3. Staff Preparation

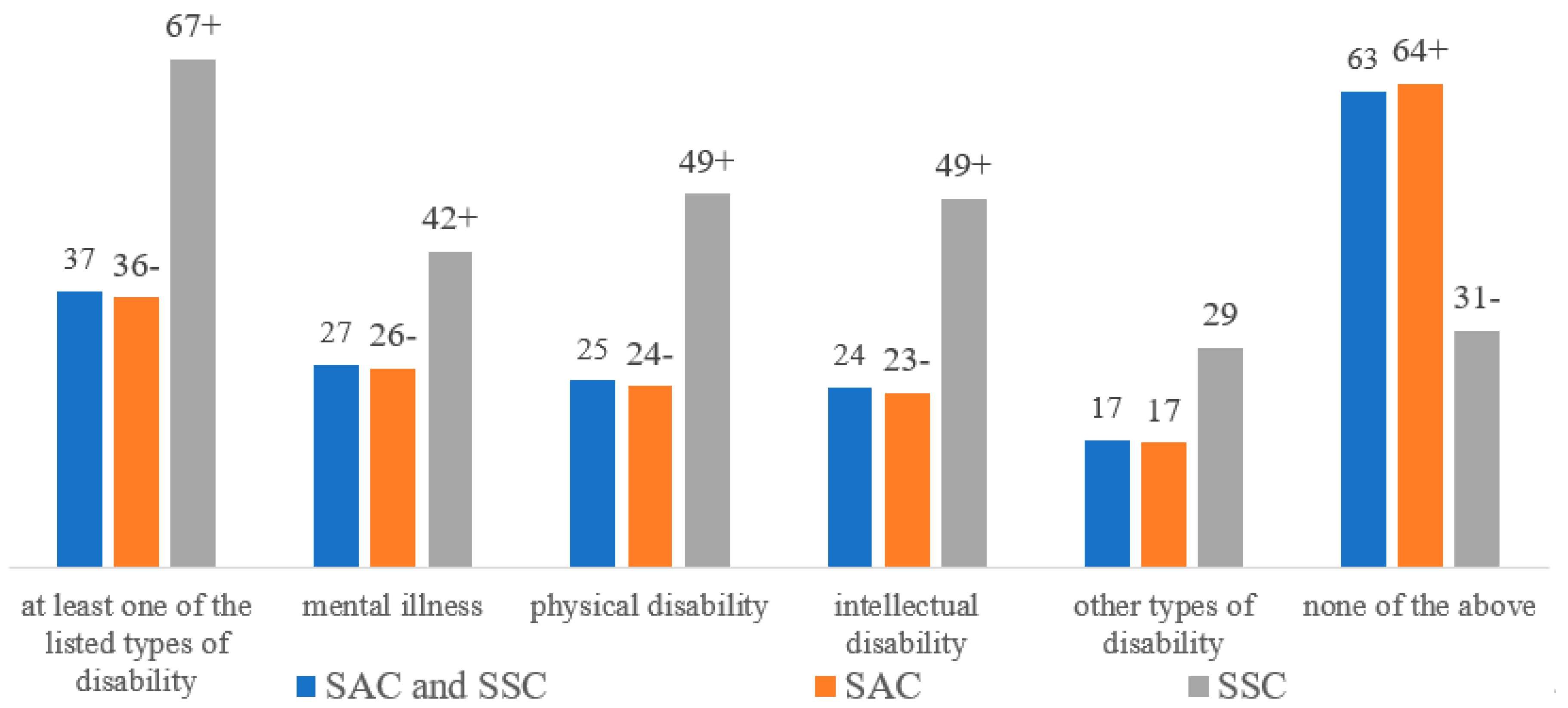

The issues related to the preparation of the staff of social welfare institutions for implementing the support circles model and – more broadly – working in the area of disability were one of the key areas explored during the quantitative research phase with SAC and SSC.

37% of representatives from the surveyed units declare having a staff of specialists qualified in the area of support for individuals with at least one type of disability. In this context, the most frequently mentioned groups were people with mental health issues, followed by those with physical and intellectual disabilities, and then individuals with other types of disabilities.

Figure 1.

Availability of qualified disability specialists (data in %).1 The data for the general sample of SAC and SSC have been weighted according to the type of unit. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 1.

Availability of qualified disability specialists (data in %).1 The data for the general sample of SAC and SSC have been weighted according to the type of unit. Source: own elaboration.

It is evident that SSC are significantly more likely to have personnel with appropriate qualifications in this area (67%) compared to SAC (36%). The "+" and "-" symbols on the chart above indicate statistically significant differences at a 95% confidence level. It is also worth noting that having a staff of specialists qualified in the area of disabilities is most commonly declared by representatives of SAC in cities with county rights (77%) and urban-rural municipalities (49%), while the least common are those representing SAC or SSC in rural municipalities (27%).

In the context of the potential spread of the circles of support model, it is worth mentioning that 12% of representatives from the surveyed entities have heard of the solution and remember what it entails. Once again, those representing SSC (42%) are significantly more likely to know about it compared to the managerial staff of SAC (11%). Additionally, 8% of respondents declare having implemented or having specific plans for implementing this model – those representing SSC (32%) are much more likely to do so compared to the managerial staff of SAC (8%).

One in five participants of the study declares having the resources necessary to implement the circles of support model, which shows the scale of challenges in the social assistance sector in terms of implementing similar solutions for people with disabilities. This (subjective) belief is expressed significantly more often by representatives of SSC (46%) compared to those representing SAC (20%). In terms of the type of local government unit, SAC in rural municipalities stand out, where the managerial staff is the least convinced of having sufficient resources (16%).

As key challenges associated with implementing the circles of support model, the respondents identified primarily insufficient financial resources (90%) and lack of appropriate human resources, i.e., specialists (88%), as well as, to a lesser extent, the need for investments related to adapting infrastructure or spaces to the needs of people with disabilities (69%). The following challenges were related to access to knowledge and familiarity with so-called "best practices." Issues related to the lack of prepared specialist staff are interpreted as challenges more often by representatives of SAC (88%) compared to the managerial staff of SSC (72%). The same observation can be made regarding issues related to ensuring accessibility for people with disabilities (SAC staff – 70%, SSC staff – 50%). Once again, representatives from SAC in rural municipalities stand out as recognizing the most challenges or barriers in implementing the circles of support model.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The circles of support have the potential to significantly improve the quality of life for people with disabilities by increasing their independence and social integration. Despite some implementation barriers, their effectiveness in promoting autonomy and social support is promising [

22,

23]. Further research could help optimize these programs and better understand their impact.

Circles of support are not only a social service but also a form of social capital – they build the resilience of local communities, support deinstitutionalization processes, and improve the quality of life for individuals with intellectual disabilities and their families. A well-designed model is scalable, flexible, and adaptable to different local contexts. The reference cost for supporting one participant per year in Poland should be set at 10,000 PLN – this value covers necessary individual and group activities, as well as environmental actions. Option B (mixed) and C (independent service delivery) can form the basis for building sustainable local social service systems, particularly in the context of the planned transformation of sheltered housing environments into independent living centres. It is essential to ensure long-term funding, integrate social activities with health services, and build the competencies of local institutions. When implementing circles, it is worth considering additional revenue sources, such as cooperation with local businesses or crowdfunding. It is also important to seek partnerships with local organizations to reduce costs for renting premises or transportation, increase volunteer involvement, and promote social campaigns.

In Poland, circles of support are being developed as an innovative form of community-based assistance for persons with disabilities, particularly within SSC. This model of circles of support for persons with disabilities integrates formal support systems with informal networks such as families, neighbours, and volunteers. Our research indicates that it aligns with deinstitutionalization policies being its important pillar and demonstrates significant cost-effectiveness. However, challenges remain, notably financial and staffing constraints, particularly in rural areas. In other European countries however (such as for example in Sweden) formal circles of support are not widely implemented, the concept of individualized, community-centred support is deeply embedded in the welfare system. Individuals with disabilities are granted personalized support rights, including the employment of personal assistants, enabling greater autonomy and self-determination. This framework, emphasizing individual choice and independence, resonates with the objectives of circles of support, albeit through a different operational structure [

24,

25]. In countries as in the Netherlands, the approach is more similar to Poland. Circles of support are formally integrated into care systems for persons with intellectual disabilities. They serve not only to provide daily support but also to assist in crisis situations. The Dutch model systematically involves family, friends, and professionals to create a robust support network around individuals with disabilities [

26]. Comparatively, the Polish and Dutch models exhibit greater formalization within public policies and service structures, whereas the Swedish model emphasizes flexible, user-driven assistance without the formal branding of "circles of support." In terms of financing, Sweden offers beneficiaries greater financial autonomy, whereas in Poland and the Netherlands, funding and service organization remain more institutionally managed. All three models emphasize the critical role of local community engagement, albeit to varying degrees of formalization. These international comparisons underscore the importance of ensuring flexibility, sustainability, and empowerment within circles of support programs in Poland, especially during the upcoming scaling efforts planned for 2025–2029.

While the study provides a comprehensive feasibility analysis of implementing circles of support in Poland, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the analysis primarily focuses on two case studies of SSC, which despite offering valuable insights, may not fully capture the diversity of local contexts across the country. Differences in municipality size, resource availability, and community engagement could significantly influence the scalability and effectiveness of the model. Second, the financial analysis, although detailed, relies partly on estimated costs and self-reported data from SSC staff, which might not fully reflect long-term expenses or unexpected implementation challenges. Third, the nationwide survey of SAC and SSC management staff assesses subjective perceptions of readiness, which may not correspond precisely to actual institutional capacities. Finally, the study does not include perspectives from persons with disabilities or their families, whose experiences could provide critical insights into the effectiveness and responsiveness of circles of support. Future research should address these limitations by including longitudinal case studies, a broader range of municipalities, and direct qualitative evaluations from service users and their families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, IG and BS; methodology: IG; software: IG; validation: IG; formal analysis, IG and BS; investigation, IG and BS; resources: IG and BS; data curation: IG and BS; writing—original draft preparation: IG and BS; writing—review and editing: IG; visualization: IG; supervision: IG.; project administration: BS; funding acquisition: BS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript..

Funding

This research was funded by by the State Fund for the Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons in Poland under the project: "Circles of Support — from Concept to Dissemination”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SSC |

Social service centers |

| SAC |

Social assistance centers |

| NGO |

Non governmental organisation |

References

- Krysta, K. Multidisciplinary Approach in Diagnosing Patients with Mental Health and Intellectual Disability. Eur. Psychiatry 2022, 65, S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, E.; Bubash, S.; Fialka-Feldman, M.; Hayes, A. Circles of Support and Self-Direction: An Interview Highlighting a Journey of Friendship and Managing Services. Inclus. Pract. 2022, 1, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistow, G.; Perkins, M.; Knapp, M.; Bauer, A.; Bonin, E. Circles of Support and Personalization. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2016, 20, 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chomiuk, A. Sustainable Development in the Non-Governmental Organization Sector. In Sustainability and Sustainable Development; 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jay, N. The Circles Network CREDO Project. Support Learn. 2003, 18, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pearpoint, J.; O'Brien, J.; Forest, M. The Inclusion Papers: Strategies to Make Inclusion Work; Inclusion Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, M. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice; Macmillan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Anastasiou, D.; Kauffman, J.M. The Social Model of Disability: Dichotomy between Impairment and Disability. J. Med. Philos. 2013, 38, 441–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, T.; Ainscow, M. Index for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools; Centre for Studies on Inclusive Education: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Simplican, S.C.; Leader, G.; Kosciulek, J.; Leahy, M. Defining Social Inclusion of People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: An Ecological Model of Social Networks and Community Participation. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 38, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holanda, C.; De Andrade, F.; Bezerra, M.; Da Silva Nascimento, J.; Da Fonseca Neves, R.; Alves, S.; Ribeiro, K. Support Networks and People with Physical Disabilities: Social Inclusion and Access to Health Services. Cienc. Saude Colet. 2015, 20, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askheim, O.P.; Beresford, P.; Heule, C. Mend the Gap—Strategies for User Involvement in Social Work Education. In Service User Involvement in Social Work Education; McLaughlin, H., Duffy, J., McKeever, B., Sadd, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018.

- Dan, B. Disability and Empowerment. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020, 62, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kúld, P.; Frielink, N.; Zijlmans, M.; Schuengel, C.; Embregts, P. Promoting Self-Determination of Persons with Severe or Profound Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithen, J.; Aitken, Z.; Ziersch, A.; Kavanagh, A. Inequalities in Social Capital and Health between People with and without Disabilities. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 126, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chenoweth, L.; Stehlik, D. Implications of Social Capital for the Inclusion of People with Disabilities and Families in Community Life. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2004, 8, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parchomiuk, M.; Żyta, A.; Ćwirynkało, K. Challenges Ahead: Exploring External Barriers to Self-Determination in Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2025, 156, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eden, C.; Ackermann, F. Theory into Practice, Practice to Theory: Action Research in Method Development. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 271, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, R.; Martinsons, M.; Malaurent, J. Research Perspectives: Improving Action Research by Integrating Methods. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2021, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, I. Action Research as a Methodology for Professional Development in Leading an Educational Process. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 64, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araten-Bergman, T.; Bigby, C. Forming and Supporting Circles of Support for People with Intellectual Disabilities—A Comparative Case Analysis. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 47, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancaster, K.; Bhopti, A.; Kern, M.; Taylor, R.; Janson, A.; Harding, K. Effectiveness of Peer Support Programs for Improving Well-Being and Quality of Life in Parents/Carers of Children with Disability or Chronic Illness: A Systematic Review. Child Care Health Dev. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordic Welfare Centre. Personalised Support and Services for Persons with Disabilities—Mapping of Nordic Models; Nordic Welfare Centre: Helsinki, Finland, 2021.

- Brennan, C.; Rice, J.; Traustadóttir, R.; Anderberg, P. How Can States Ensure Access to Personal Assistance When Service Delivery Is Decentralized? A Multi-Level Analysis of Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Scand. J. Disabil. Res. 2017, 19, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkers, E.; Cloïn, M.; Pop, I. Informal Help in a Local Setting: The Dutch Social Support Act in Practice. Health Policy 2021, 125, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).