Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Local Surface Morphology Using AFM

3.2. Analysis of Local Piezoelectric Hysteresis Loops Using PFM

3.3. Analysis of Spontaneous Polarization Distribution Using PFM

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bi, K.; et al. . Interfacial Polarization Control Engineering and Ferroelectric PZT/Graphene Heterostructure Integrated Application // Nanomaterials. – 2024. – Т. 14. – №. 5. – С. 432.

- Sezer, N.; et al. . A comprehensive review on the state-of-the-art of piezoelectric energy harvesting // Nano Energy. – 2021. – Т. 80. – С. 105567.

- Li, X.; et al. . Plantar pressure measurement system based on piezoelectric sensor: a review // Sensor Review. – 2022. – Т. 42. – №. 2. – С. 241-249.

- Jung, J.; et al. . Review of piezoelectric micromachined ultrasonic transducers and their applications // Journal of Micromechanics and Microengineering. – 2017. – Т. 27. – №. 11. – С. 113001.

- Saadon, S.; et al. . A review of vibration-based MEMS piezoelectric energy harvesters // Energy Conversion and Management. – 2011. – Т. 52. – №. 1. – С. 500-504.

- Duan, S.; et al. . Innovation Strategy Selection Facilitates High-Performance Flexible Piezoelectric Sensors // Sensors. – 2020. – Т. 20. – №. 10. – С. 2820.

- Fedulov, F.A.; et al. . Magnetoelectric effects in stripe- and periodic heterostructures based on nickel–lead zirconate titanate bilayers // Russian Technological Journal. – 2022. – Т. 10. – №. 3. – С. 64-73.

- Ivanov, M.S.; et al. . Impact of compressive and tensile epitaxial strain on transport and nonlinear optical properties of magnetoelectric BaTiO3-(LaCa)MnO3 tunnel junction // Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. – 2021. – Т. 54. – №. 27. – С. 275302.

- Yan, M.; et al. . Porous ferroelectric materials for energy technologies: current status and future perspectives // Energy & Environmental Science. – 2021. – Т. 14. – №. 12. – С. 6158-6190.

- Fei, C.; et al. . Modification of microstructure on PZT films for ultrahigh frequency transducer // Ceramics International. – 2015. – Т. 41. – С. S650-S655.

- Atanova, A.V.; et al. . Microstructure analysis of porous lead zirconate–titanate films // Journal of the American Ceramic Society. – 2021. – Т. 105. – №. 1. – С. 639-652.

- Zhang, S.; et al. . Advantages and challenges of relaxor-PbTiO3 ferroelectric crystals for electroacoustic transducers – A review // Progress in Materials Science. – 2015. – Т. 68. – С. 1-66.

- Xiao, W.; et al. . Well-balanced performance achieved in PZT piezoceramics via a multiscale regulation strategy // Materials Horizons. – 2024. – Т. 11. – №. 21. – С. 5285-5294.

- Liu, H.; et al. . Enhanced performance of piezoelectric composite nanogenerator based on gradient porous PZT ceramic structure for energy harvesting // Journal of Materials Chemistry A. – 2020. – Т. 8. – №. 37. – С. 19631-19640.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. . Porous PZT Ceramics with Aligned Pore Channels for Energy Harvesting Applications // Journal of the American Ceramic Society. – 2015. – Т. 98. – №. 10. – С. 2980-2983.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. . Enhanced pyroelectric and piezoelectric properties of PZT with aligned porosity for energy harvesting applications // Journal of Materials Chemistry A. – 2017. – Т. 5. – №. 14. – С. 6569-6580.

- Jia, Q.X.; et al. . Polymer-assisted deposition of metal-oxide films // Nature Materials. – 2004. – Т. 3. – №. 8. – С. 529-532.

- Kozuka, H.; et al. PVP-assisted sol-gel deposition of single layer ferroelectric thin films over submicron or micron in thickness // Journal of the European Ceramic Society. – 2004. – Т. 24. – №. 6. – С. 1585-1588.

- Yamano, A.; et al. . Ferroelectric domain structures of 0.4-μm-thick Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 films prepared by polyvinylpyrrolidone-assisted Sol-Gel method // Journal of Applied Physics. – 2012. – Т. 111. – №. 5.

- Stancu, V.; et al. . Effects of porosity on ferroelectric properties of Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3 films // Thin Solid Films. – 2007. – Т. 515. – №. 16. – С. 6557-6561.

- Oh, S.; et al. . Fabrication of 1㎛ Thickness Lead Zirconium Titanate Films Using Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) Added Sol-gel Method // Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials. – 2011. – Т. 12. – №. 5. – С. 222-225.

- Hu, X.; et al. . Fabrication of porous PZT ceramics using micro-stereolithography technology // Ceramics International. – 2021. – Т. 47. – №. 22. – С. 32376-32381.

- Yang, A.; et al. . Microstructure and Electrical Properties of Porous PZT Ceramics Fabricated by Different Methods // Journal of the American Ceramic Society. – 2010. – Т. 93. – №. 7. – С. 1984-1990.

- Björk, E.M. . Surface Area Determination of Particle-Based Mesoporous Films Using Krypton Physisorption // ACS Omega. – 2024. – Т. 9. – №. 5. – С. 5899-5902.

- Wang, Q.; et al. . Porous pyroelectric ceramic with carbon nanotubes for high-performance thermal to electrical energy conversion // Nano Energy. – 2022. – Т. 102. – С. 107703.

- Schultheiß, J.; et al. . Orienting anisometric pores in ferroelectrics: Piezoelectric property engineering through local electric field distributions // Physical Review Materials. – 2019. – Т. 3. – №. 8.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. . Understanding the effect of porosity on the polarisation-field response of ferroelectric materials // Acta Materialia. – 2018. – Т. 154. – С. 100-112.

- Zhang, Z.; et al. . Significantly enhanced dielectric and energy storage performance of blend polymer-based composites containing inorganic 3D–network // Materials & Design. – 2018. – Т. 142. – С. 106-113.

- Bowen, C.R.; et al. . Pyroelectric materials and devices for energy harvesting applications // Energy Environ. Sci.. – 2014. – Т. 7. – №. 12. – С. 3836-3856.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. . Performance Enhancement of Flexible Piezoelectric Nanogenerator via Doping and Rational 3D Structure Design For Self-Powered Mechanosensational System // Advanced Functional Materials. – 2019. – Т. 29. – №. 42.

- Marselli, S.; et al. . Porous piezoelectric ceramic hydrophone // The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. – 1999. – Т. 106. – №. 2. – С. 733-738.

- Roscow, J.; et al. . Porous ferroelectrics for energy harvesting applications // The European Physical Journal Special Topics. – 2015. – Т. 224. – №. 14-15. – С. 2949-2966.

- Ivanov, M.; et al. . Nanoscale Study of the Polar and Electronic Properties of a Molecular Erbium(III) Complex Observed via Scanning Probe Microscopy // Crystals. – 2023. – Т. 13. – №. 9. – С. 1331.

- Park G., T.; et al. Piezoelectric and ferroelectric properties of 1-μm-thick lead zirconate titanate film fabricated by a double-spin-coating process //Applied physics letters. – 2004. – Т. 85. – №. 12. – С. 2322-2324.

- Choi J., J.; et al. Sol–Gel Preparation of Thick PZN–PZT Film Using a Diol-Based Solution Containing Polyvinylpyrrolidone for Piezoelectric Applications //Journal of the American Ceramic Society. – 2005. – Т. 88. – №. 11. – С. 3049-3054.

- Calderón-Piñar, F.; et al. Ferroelectric hysteresis and improved fatigue of PZT (53/47) films fabricated by a simplified sol-gel acetic-acid route //Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics. – 2014. – Т. 25. – №. 11.

- Nguyen M., D. , Houwman E. P., Rijnders G. Large piezoelectric strain with ultra-low strain hysteresis in highly c-axis oriented Pb (Zr0.52Ti0.48)O3 films with columnar growth on amorphous glass substrates //Scientific reports. – 2017. – Т. 7. – №. 1. – С. 12915.

- Delimova, L.; et al. Porous PZT Films: How Can We Tune Electrical Properties? // Materials. – 2023. – Т. 16. – №. 14. – С. 5171.

- Cornelius T., W.; et al. Piezoelectric response and electrical properties of Pb(Zr1-xTix)O3 thin films: The role of imprint and composition //Journal of Applied Physics. – 2017. – Т. 122. – №. 16.

| № sample | wt % PVP360000 | Number of layers | Ellipsometry thickness, nm | n | Relative porosity , % | SEM thickness, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 10 | 370 | 2.543 | 0.0 | - |

| 2 | 1 | 9 | 390 | 2.397 | 6.8 | 407-503 |

| 3 | 3 | 7 | 370 | 2.288 | 11.0 | 322 – 347 |

| 4 | 6.6 | 4 | 390 | 1.829 | 33.3 | 375 – 378 |

| 5 | 14 | 3 | 400 | - | - | 357 – 363 |

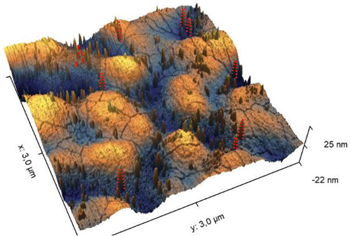

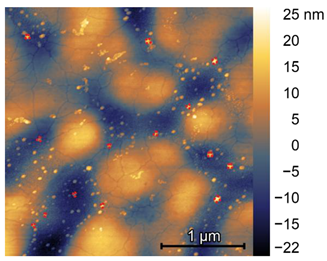

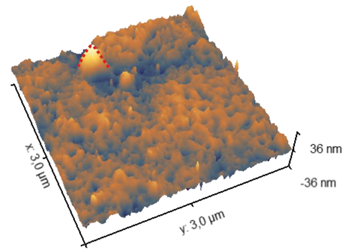

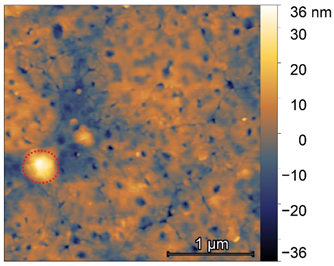

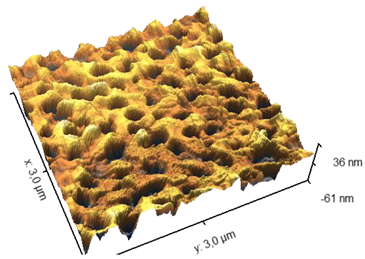

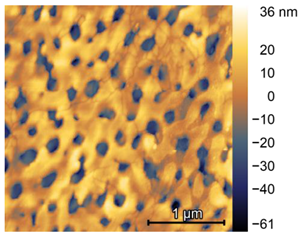

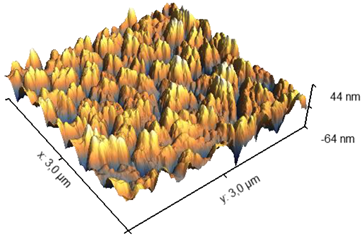

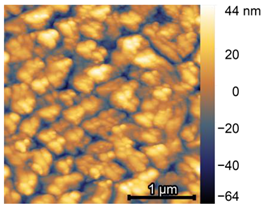

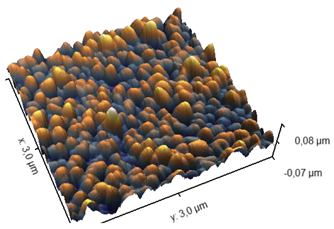

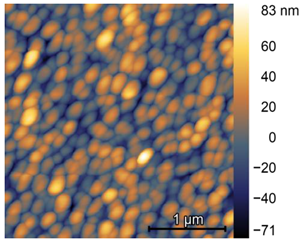

| wt % PVP 360000 | 3D and 2D visualization of Pb(Zr0,48Ti0,52)O3 topography | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 |  |

|

| 1 |  |

|

| 3 |  |

|

| 6.6 |  |

|

| 14 |  |

|

| wt % PVP360000 | Average roughness (Sa), nm | RMS roughness (Sq), nm | Air phase area (As), mkm2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5,28 | 6,56 | 0 |

| 1 | 4,25 | 5,55 | 0,506 |

| 3 | 10,31 | 13,49 | 1,624 |

| 6,6 | 16,38 | 20,10 | 2,619 |

| 14 | 16,03 | 20,05 | 1,637 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).