1. Introduction

In a March 15, 2020 article titled “The Workers Who Face the Greatest Coronavirus Risk,” the New York Times listed dental hygienists, dental assistants, dentists, and other dental professionals among the professions with the most significant risk of coronavirus infection [

1]. The first COVID-19 patient was detected in Japan in January 2020. When the first declaration of a state of emergency order was released, many dental professionals in Japan closed or limited their practices as SARS-CoV-2 infections began surging from April to June 2020 in Japan. However, since no significant clusters were reported at dental clinics in Japan, most clinics restarted normal operations when the declaration was lifted. Since then, Japan has faced several waves of SARS-CoV-2 infections, plus an eighth wave caused by the Omicron variant on May 2023. In May 2023, SARS-CoV-2 infections were downgraded to an infectious disease that does not require notification in Japan, and although the exact number of the patients since then is not known, several waves of infections have repeatedly occurred in Japan.

Statistics on clusters occurring through the fifth wave in Japan studied by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare indicate that, as of July 2021, 1225 clusters involving medical institutions and 1680 clusters involving care facilities for the elderly person or children, those with disabilities, had occurred [

2]. Although sporadic infections occurred in dental professionals at dental clinics during this period, no cluster of SARS-CoV-2 infections associated with dental practice had been reported in Japan till now [

3]. Regarding whether dental professionals are at higher risk of lingering SARS-CoV-2 infection, dental professionals have continued to provide care and treatment for pandemic three years in Japan. Fortunately, the initial predictions by the New York Times, however, have failed to happen. Dental professionals appear not to have caused any infections or clusters through horizontal transmission between clinic patients. SARS-CoV-2 is present in large amounts in the infected person’s saliva [

4], and dental procedures are aerosol-producing procedures containing saliva in various levels [

5]. In the current consensus, SARS-CoV-2 is reported to transmit through contagious and droplet, and possibly droplet nuclei (airborne) in some conditions [

6]. When considering the nature and transmission of SARS-CoV-2, we were led to question why have dental professionals, who rely primarily on standard precautions for contagious infection, remained relatively unscathed, and why have clusters not been seen at dental clinics.

Puzzled by these questions, we performed antibody testing to determine the level of previous infections in dental professionals during the pre-vaccine period of SARS-CoV-2, corresponding to the time from the first to third waves in Japan. The virus load in aerosols produced during dental procedures performed on COVID-19 patients and in their saliva was also determined to answer why SARS-CoV-2 did not spread through dental clinics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determination of IgG/IgM Antibody Titer Against SARS-CoV-2 in the Blood (Evidence for Previous Infections) in Dental Professionals and Their Families During the SARS-CoV-2 Wave

This portion of the study was conducted with the approval of the Clinical Research Management Center, Dokkyo Medical University (Approval No. R-35-21J). Informed consent was obtained from all participants following the “Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Biological Research Involving Human Subjects” in Japan.

The participants were oral surgeons and dental hygienists practicing in the Department of Oral Surgery of Dokkyo Medical University Hospital. Furthermore, their families, and associated dentists, dental hygienists, nurses, dental assistants, dental technicians, and administrative staff of clinics were examined. All participant’s ages were over 20 at the time of consent (

Table 1). Those who refused or were found unsuited to participate by the principal investigator (HK) were excluded from the study.

The antibody testing was performed using the GenBody COVID-19 IgM/IgG Test® rapid antibody detection kit for SARS-CoV-2 (GenBody Inc. Chungcheongnam, Korea). A 20-µl of whole blood collected from each participant was applied to the test plate. Antibody status was assessed after 10 to 20 minutes. The kit’s sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were as follows: sensitivity 50% on Day 1-6, 91·7% after Day 7; specificity 97·5%; and accuracy 95·2% on Day 1-6, 96·5% after Day 7.

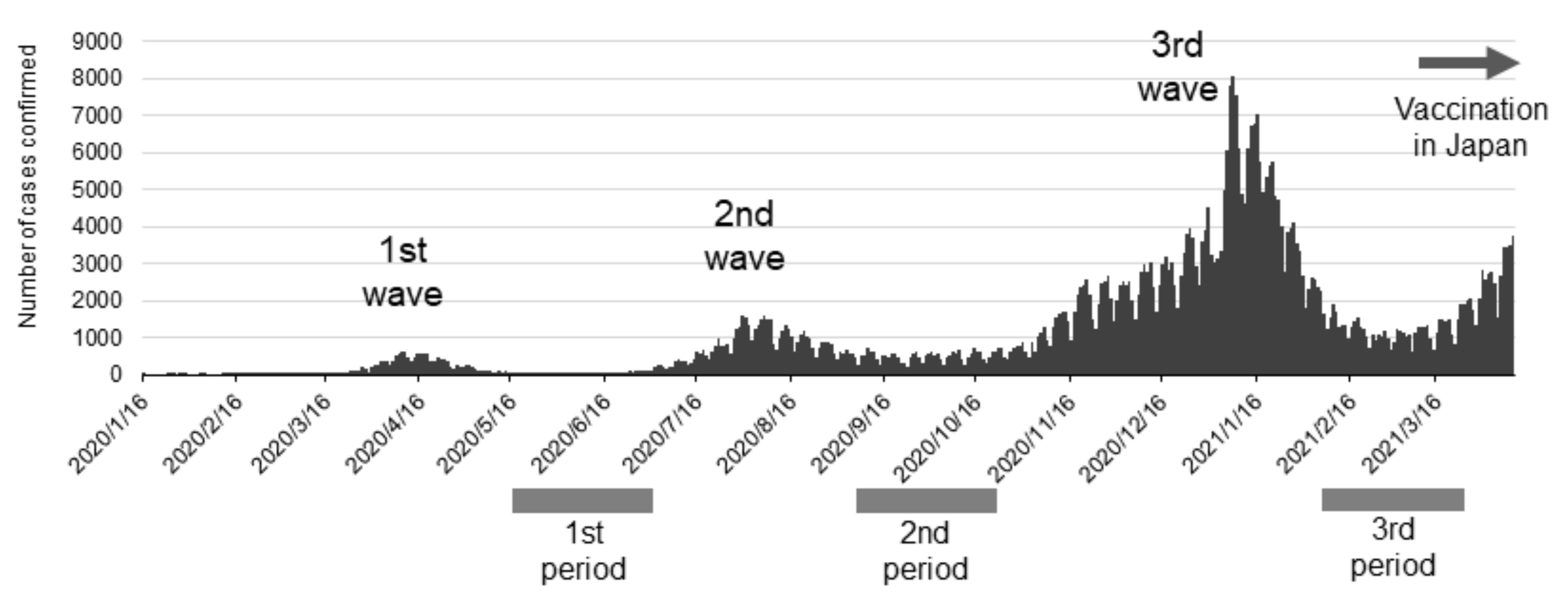

SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests were performed three times on pre-vaccinated dental professionals to coincide with periods of high SARS-CoV-2 prevalence in Japan (as determined according to the number of PCR-positive people in public data on the website of the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare). The first round of tests was performed from May 27 to July 3, 2020, the second from September 23 to October 30, 2020, and the third from January 31 to April 3, 2021 (

Figure 1). The antibody positivity rate in dental professionals and their families was calculated.

The Delta variant was first detected in Japan in a quarantine facility toward the end of March 2021 and spreading into the community of the Delta variant began in April. The Alpha variant was first detected around February, but the date of initial detection is unclear.

2.2. Sample Collection of Saliva and Aerosol During Oral Management for Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients

We performed this part of the study with the approval of the clinical ethics committee, Dokkyo Medical University Hospital (Approval No. R-45-2). The participants were COVID-19 patients hospitalized for treatment who were referred for oral management by a doctor in Department of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. All participants had moderate to severe respiratory symptoms and required respiratory management. Participants capable of consenting were informed orally about the study and then asked to consent. When a participant could not give consent, a family member was asked to consent on their behalf. The demographic profile of the participants is shown in

Table 2.

We conducted an oral examination before the management. Then, No. 51A filter paper (Advantec Toyo Kaisha, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), cut to 15 × 15 mm and autoclaved, was placed in the buccal vestibule or floor of the mouth for 1 minute. The wetted filter paper was collected in a 1.5-mL tube. For the aerosol sample collection, the filter paper and a gelatin filter (Sartorius Corporate Administration GmbH, Gottingen, Germany) were attached to the center of the inlet of extra-oral suction equipment before the start of the oral management. The vacuum inlet was placed approximately 20 cm from the patient’s mouth. Aerosol suction was maintained during the examination and the management. Then, dental plaque and detached epithelium were removed by tooth brushing and wiping, and dental scaling was performed with a VIVAase ultrasonic scaler (Nakanishi Inc., Tochigi, Japan). After dental scaling, residual debris was removed with another round of brushing and wiping. Finally, a moistening gel (Pepti-Sal Gentle MouthGel, T & K Co., Tokyo, Japan; Hinora, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Tokushima, Japan) was applied to the oral mucosa to moisten the mouth and lips. The oral management procedure took about 15 minutes per patient. After the management, the gelatin filter and filter paper were collected as aerosol samples. The saliva and aerosol samples were soaked in 250 µl of normal saline and stored at -25 ºC until analysis.

2.3. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Viral Genome with Real-Time RT-qPCR

Viral genome detection was conducted according to the instructions for using the SARS-CoV-2 Direct Detection RT-qPCR Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan). Briefly, 8 µl of each sample was mixed with Solution A. The mixture was heat-treated and then analyzed with RT-qPCR. SARS-CoV-2 RNA US N1/N2 of a known concentration was used as the positive control (Takara Bio Inc.). RNase-free water was used as the negative control. The primers used with the kit were detection primers listed in “2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-time RT-PCR Panel Primers and Probes” of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [

7].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were determined for the participants’ demographics in the antibody and PCR studies. A chi-squared test with a significance level of 0.05 was used to statistically test the data of the antibody study of the participants. Student’s t-test with a significance of 0.05 was used to compare Ct values associated with virus detected in saliva and aerosol samples. In the scatter plot of viral loads, values below the detection limit on Ct value analysis were indicated as 0, and values below the detection limit in copy number analysis were indicated as 0.01.

3. Results

3.1. Antibody Positive Rate for SARS-CoV-2 in Dental Professionals

SARS-CoV-2 prevalence from the first to third waves in Japan is shown together with the timing of the antibody tests in

Figure 1. Japanese people used only social and personal infection prevention measures through the third wave. Vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 became available just before the fourth wave hit in Japan. Antibody tests in this study were performed at the ends of the first, second, and third waves when antibodies from previous infections would have been detectable if infected with the virus. Noteworthy, the antibody tests were performed before vaccination in Japan, therefore they do not indicate rises in antibody titer from vaccination. We show the results of the antibody tests in

Table 3, which were performed to coincide with times of prevalence. IgG antibodies were detected in 2 of the 424 tests performed. One affected participant was a dentist, and the other was a cohabiting family. None of the samples was positive for IgM antibodies. Since only 2 participants tested positive for antibodies, comparing the frequencies of previous infections among occupations, place of residence, or according to what infection-prevention measures were in place at different clinics was impossible. The results, however, show that very few dental professionals had a history of infection before the fourth wave in Japan.

3.2. Viral Loads in the Saliva or Oral Management-Related Aerosol of COVID-19 Patients

We analyzed the viral loads in samples of saliva or oral management-related aerosols collected from 24 COVID-19 patients (

Table 2). The mean age was 59.0 (42-89) years. Twenty-two of the participants were men, and 2 were women. Samples were collected during the 39 oral management sessions performed. The SARS-CoV-2 detected at the time of the management in these patients was Variant 20I (Alpha, V1)/B·1·1·7 in 12 patients and Variant 21A (Delta)/B·1·617·2 in 11 patients. The variant type of 1 patient was not determinable. Only 3 of the patients had no medical history. Eighteen of the 24 patients (75%) had a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, obesity, dyslipidemia, or respiratory disease. Most of the patients had comorbidities. The days of sample collection ranged from 3 to 46 days from the positive result for SARS-CoV-2 and was, on average, 14.6 days. Twenty-two of the 24 patients required mechanical ventilation (noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: 4 patients, intubation: 18 patients, [intraoral intubation: 10 patients, tracheostomy: 8 patients]). Two patients required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation along with invasive mechanical ventilation. Most patients had ventilation-associated oral dryness and biofilms consisting of dental plaque, tartar, and detached epithelium. Oral management by dental scaling and tooth brushing was possible for 17 of the 24 patients (70.8%). Management was possible only through tooth brushing for 6 of the 24 patients (25%) (

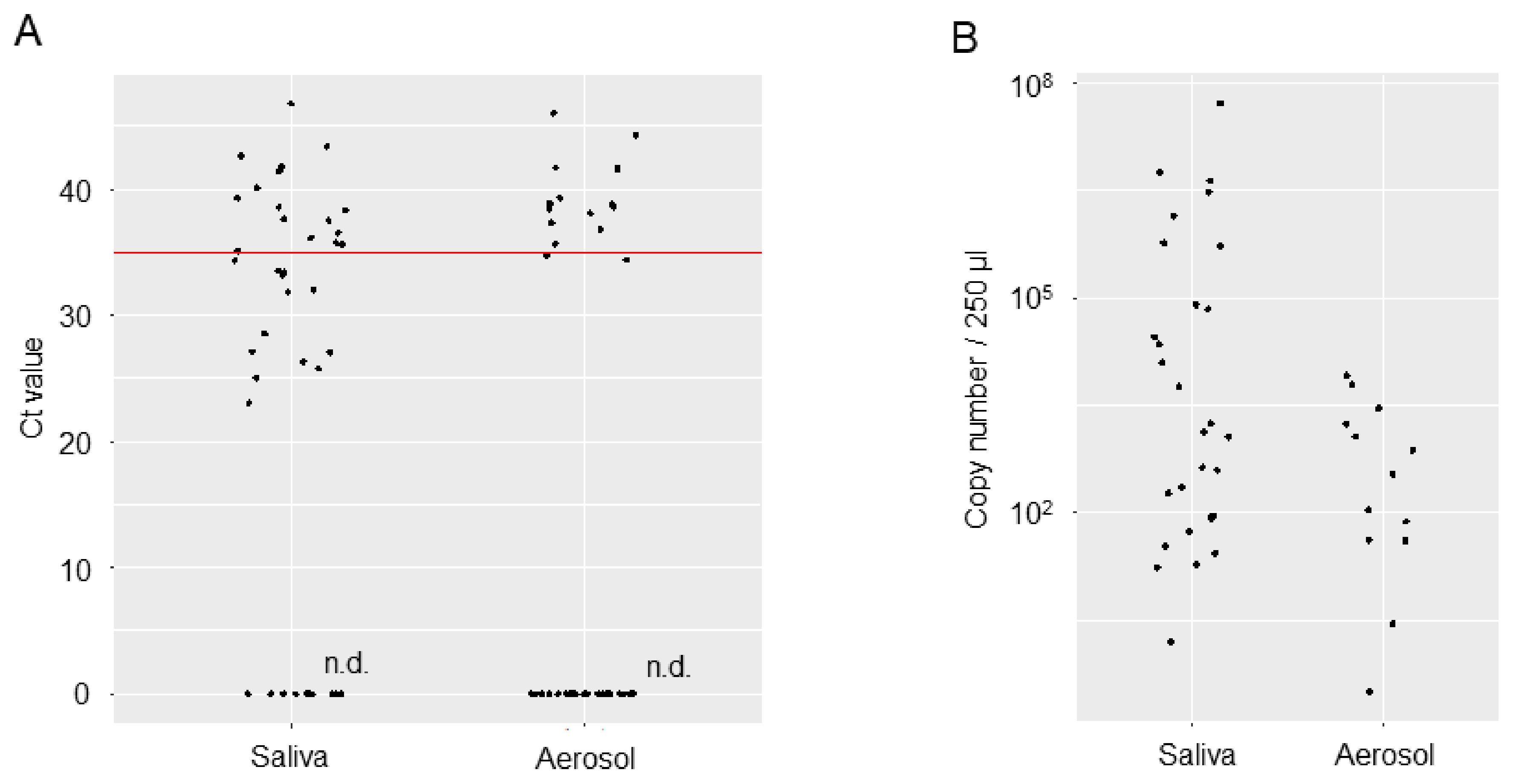

Table 2). Viral loads in the saliva and aerosol samples are shown regarding RT-qPCR Ct values and copy numbers (

Figure 2). Mean Ct values were 34.76 [95% confidence interval (CI): 32.45, 37.07] for the saliva samples and 38.99 [95% CI: 37.28, 41.28] for the aerosol samples. Copy numbers were estimated to be 969,495 [95% CI: -519,755, 2,458,745] per 250 µl for the saliva samples and 1,656 [95% CI: -102, 3413] for the aerosol samples. Although the viral loads in the saliva and aerosol samples are not amenable to comparison, mean Ct values in the aerosol were near the limit of detection, with copy numbers on the order of 10

6 to 10

7 in the saliva samples but 10

3 in the aerosol samples, which represents a 1000- to 10000-fold decrease.

4. Discussion

In 2020, to estimate the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Japan, some companies and agencies conducted an epidemiological survey of infection by antibody testing. The test conducted by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare to evaluate the performance of antibody test kits showed an antibody positivity rate of 0.1% to 1.35% in Tokyo, where infections were prevalent at the time [

8,

9]. Large-scale antibody testing conducted by SoftBank Group Corp. showed an antibody positivity rate of 0.43% in the overall sample, 1.79% in healthcare professionals, 0.89% in dental assistants, and 0.75% in dentists [

10]. Note that the antibody positivity rate among close contacts is thought to be 11.76%. The low antibody positivity (i.e., previous infection) rate of 0.47% identified in dental professionals through the third wave follows the rates seen in nationwide, large-scale testing programs, reflecting actual levels.

Several issues face the provision of dental practice during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: cells of the lingual mucosa and salivary glands harbor the virus, meaning that saliva is a potential source of infection [

4]; dental professionals are at risk of exposure to virus-laden aerosols when treating patients; the diffusion of aerosols in the air in clinics poses the risk of horizontal transmission between patients; difficulty to screen for asymptomatic/subclinical infections (which nonetheless feature viral shedding), there is no way to determine the risk of infection before dental practice is administered. These issues were the source of concern for the spread of viral infections via dental practice. Still, contrary to our assumption, our antibody tests and other large-scale antibody testing performed on dental professionals showed a low positivity rate following infection peaks in the general population. Moreover, in Japan, no clusters associated with a dental practice in a dental setting have been reported.

Why the aerosols produced during dental practice did not spread infection remained unknown. Microbial infections have been conventionally classified and discussed as being transmitted via contagious, droplets and droplet nuclei; the concept of aerosol-transmitted infection was proposed for SARS-CoV-2 infections, which have occurred in a manner not attributable to contact or droplets [

6]. Aerosol is a mixture of tiny solid or liquid particles (of unspecified sizes) floating in the air. However, aerosols in the context of infections are generally defined as micro-droplets measuring no more than 5 µm in diameter. The droplets and aerosol generated from ultrasonic dental scalers may disperse upwards of 6 feet from the source [

11], and aerosols may vaporize as they travel through the air at average temperatures and humidity levels. The part remaining following evaporation corresponds to droplet nuclei as conventionally defined, but the trace quantities of virus remaining in desiccated droplet nuclei might be insufficient to cause infections for SARS-CoV-2 infections [

12].

The present study showed that relatively high viral loads were detectable in the saliva of patients with severe COVID-19 even several days after they were found positive for the virus. Although it is known that SARS-CoV-2 is present in the saliva of infected people, it is unclear whether the virus is present when saliva is secreted from infected salivary gland cells [

13], the virus contaminates saliva from infected upper airway mucosa, or the virus contaminates saliva from lower airway secretions. In the present study, aerosols generated over 15 minutes were trapped in a piece of filter paper 20 cm from the patient’s mouth. The virus was detectable in only 10 of the 39 samples collected with relatively low levels. Usually, symptomatic COVID-19 patients do not visit a local dental clinic. Most patients visiting the dental clinics are expected to be asymptomatic or presymptomatic with COVID-19. Asymptomatic or presymptomatic COVID-19 patients are now known to shed almost equal amounts of the virus from symptomatic patients [

14]. We showed that even when a substantial amount of the virus is present in the saliva, only a small amount remains in the aerosol produced in dental settings. Meethil et al. also reported that aerosol from dental settings carries less viral load than saliva [

15].

A report by Katsumi et al. from the Sendai Municipal Institute of Public Health investigated the relationship between viral isolation and PCR detection of nasal swabs collected from symptomatic patients. It estimated that one infective particle could be present in 100 to 1000 viral copies [

16]. Based on their reports combined with our current findings, it would be suggested that no more than ten infective particles would be present in the aerosol. Therefore, the aerosol generated during dental practice on COVID-19 patients is unlikely to cause infection. It could be part of the reason why dental clinics have not spread COVID-19 infection during the pandemic.

We believe that any aerosol containing virus from the saliva spread during the dental practice of asymptomatic or presymptomatic COVID-19 patients producing SARS-CoV-2 can be kept from infecting others through established measures to prevent contagious or droplet infections. Especially in dental settings, appropriate personal protective equipment and intra- and extra-oral suction equipment are beneficial. With an appreciation of these findings, oral surgeons and other dental professionals can maintain their patient’s oral health with the proper preventative measures even for next coming pandemic by micro-organisms which show contagious or droplet infections.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.T., Y.K. and H.K.; methodology, H.K. and T.W.; validation, Y.K., S.O., H.H., M.N., J.K. and K.W.; data curation, Y.K., S.O., T.H., R.S., S.Y., E.Y., M.T.O., and C.F.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.T., Y.K.; writing—review and editing, C.F., S.I., T.W., H.K.; supervision, H.K.; project administration, H.K.; funding acquisition, H.K., Y.K., S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by JSPS KAKENHI, grant number JP22K17291, JP20K10123.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects issued by Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University (Approval No. R-35-21J and Approval No. R-45-2).

Informed Consent Statement

Written Informed consent was obtained from all participants. In cases where the patients themselves could not decide; we explained the details of the research to the legal guardian of the patient. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the dentists, dental hygienists, nurses and co-medical staffs of the following facilities for their cooperation to this research. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Dokkyo University School of Medicine. Emergency and Critical Care Center, Dokkyo Medical University Hospital. Maruhashi Whole Person Dentistry, Gunma, Japan. Saotome Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Morishita Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Ishikawa Dental Clinic, Kanagawa, Higashi Ueno Dental Clinic, Tokyo, Japan. Japan. Park Dental Clinic, Saitama, Japan. Shibanishi Dental Clinic, Saitama, Japan. Bell Dental Clinic, Saitama, Japan. Hakata Dental Clinic, Fukushima, Japan. Yotsuba Dental Clinic, Saitama, Japan. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kamma Memorial Hospital, Tochigi, Japan. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Kamitsuga General Hospital, Tochigi, Japan. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Sano Kosei General Hospital, Tochigi, Japan. Kobayashi Dental Cilnic, Tochigi, Japan. Sato Dental Clinic, Saitama, Japan. Shibata Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Tochgi Dental Health Center, Tochigi, Japan. Oikawa Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Ishikawa Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Ohtomo Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Tanaka Dental Clinic, Tokyo, Japan. Sun Dental Office, Tokyo, Japan. YasuKazu Charm Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Conciel Dental Clinic, Tokyo, Japan. Iroha Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan. Tobita Dental Clinic, Ibaraki, Japan. Imatani Dental Clinic, Tochigi, Japan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Gamio, L. The workers who face the greatest coronavirus risk. The New York Times. 2020 March 15. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/bus.

- Japan Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare. 45th Novel Coronavirus Infection Disease Advisary Board material 3 - 1 Dai 45 kai shingata corona uirusu kansensyou taisaku advisary board shiryou 3-1 (in Japanese). 2021. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10900000/000812896.pdf.

- House of Counsillors, The Natinal Diet of Japan. The 204th National Diet. House of Councillors Budget Committee Meeting Minutes No. 14 Dai 204 kai kokkai. Sangiin yosan iinkai kaigiroku dai 14 gou (in Japanese). 2021. Available online: https://kokkai.ndl.go.jp/minutes/api/v1/detailPDF/img/120415261X01420210319.

- Huang, N.; Pérez, P.; Kato, T.; Mikami, Y.; Okuda, K.; Gilmore, R.C.; Conde, C.D.; Gasmi, B.; Stein, S.; Beach, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of the oral cavity and saliva. Nat Med. 2021, 27, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Z.Y.; Yang, L.M.; Xia, J.J.; Fu, X.H.; Zhang, Y.Z. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 and special precautions in dentistry. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020, 21, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Jimenez, J.L.; Prather, K.A.; Tufekci, Z.; Fisman, D.; Schooley, R. Ten scientific reasons in support of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2021, 397, 1603–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control. Research Use Only 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Real-time RT-PCR Primers and Probes. CDC’s Diagnostic Test COVID-19 Only Supplies.2019,2019–20. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/virus-requests.html.

- Japan Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare. First antibody possession test Daiikkai koutai hoyuu chyousa (in Japanese).2022. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/10906000/000640184.pdf.

- Japan Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare. Second antibody possession test.Dainikai koutai hoyuu kensa (in Japanese). 2023. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000761671.pdf.

- Softbank group Inc.Preliminary reports for antibody test Koutai kennsa kekka sokuhoutitou ni tuite (in Japanese). 2024. Available online: https://group.softbank/system/files/pdf/antibodytest.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Chiramana, S.; Hima, B.O.S.; Kishore, K.K.; Prakash, M.; Durga, P.T.; Chaitanya, S.K. Evaluation of Minimum Required Safe Distance between Two Consecutive Dental Chairs for Optimal Asepsis. J Orofac Res. 2013, 3, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedalinaghi, S.; Karimi, A.; Mojdeganlou, H.; Pashaei, Z.; Mirzapour, P.; Shamsabadi, A.; Barzegary, A.; Afroughi, F.; Dehghani, S.; Janfaza, N.; et al. Minimum infective dose of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 based on the current evidence: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usami, Y.; Hirose, K.; Okumura, M.; Toyosawa, S.; Sakai, T. Brief communication: Immunohistochemical detection of ACE2 in human salivary gland. Oral Sci Int. 2021, 18, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Saldi, T.K.; Gonzales, P.K.; Lasda, E.; Decker, C.J.; Tat, K.L.; Fink, M.R.; Hager, C.R.; Davis, J.C.; Ozeroff, C.D.; et al. Just 2 % of SARS-CoV-2-positive indivisuals carry 90% of the Virus Circulating in Communities. PNAS. 2021, 118, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meethil, A.P.; Saraswat, S.; Chaudhary, P.P.; Dabdoub, S.M.; Kumar, P.S. Sources of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Microorganisms in Dental Aerosols. J Dent Res. 2021, 100, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsumi, M.; Yamada, K.; Matsubara, H.; Narita, M.; Kawamura, K.; Tamura, S. Considerations on SARS-CoV-2 virus copy number and viral titer in specimens. Infect Agents Surv Rep. 2021, 42, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).