3.1. Characterization of the Catalysts

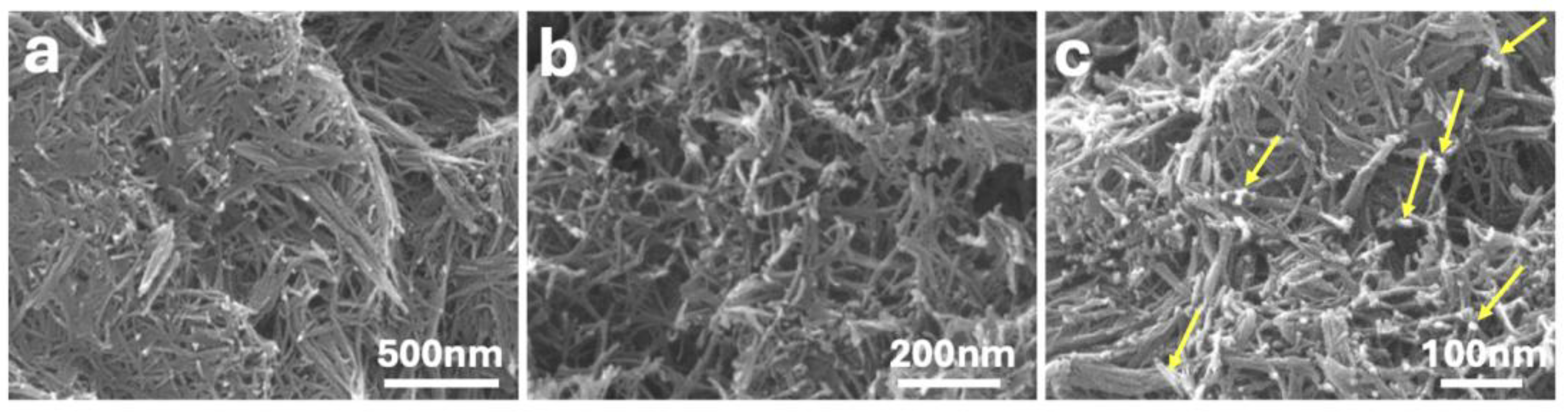

Figure 1 shows SEM images of the synthesized materials at increasing magnifications. The P25-rGO support (

Figure 1a,b) exhibits an interconnected network of fibrous TiO₂ structures with lengths of several hundred nanometers and diameters below 20 nm. These nanofibers form a porous and open framework that facilitates mass transport and light penetration. The reduced graphene oxide (rGO) component is not distinguishable at this scale due to its low contrast and highly exfoliated nature, but it is expected to interweave throughout the fibrous TiO₂ matrix, supporting structural cohesion and charge transport. In the MoS₂-modified catalyst (

Figure 1c), corresponding to 5 wt% MoS₂@P25-rGO, small and dispersed bright domains can be observed along the TiO₂ fibers (highlighted by yellow arrows), which are attributed to the localized deposition of MoS₂ nanosheets. These features suggest a good distribution of MoS₂ without bulk aggregation, maintaining the structural integrity of the fibrous support.

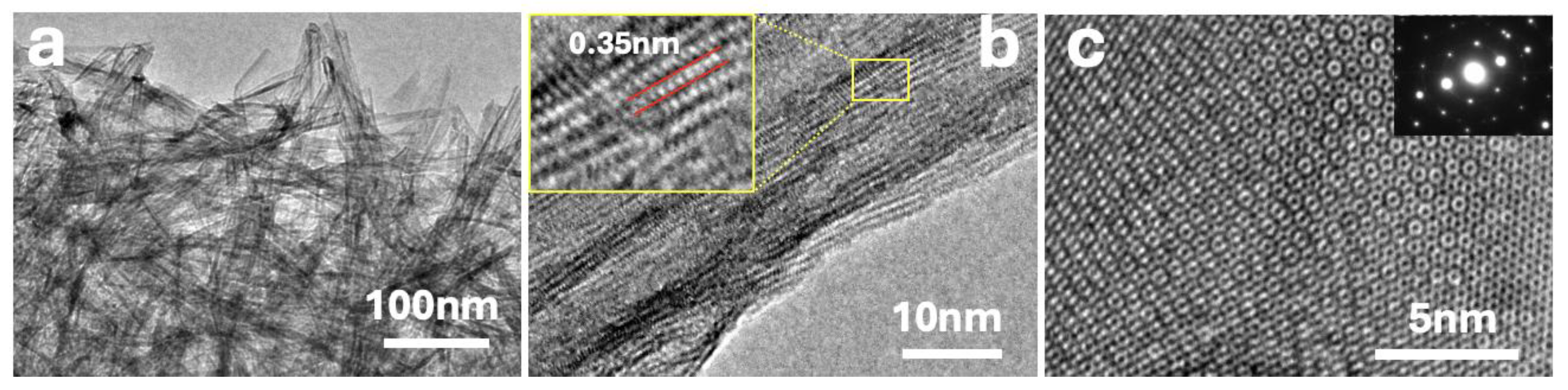

The different composites were also characterized by HRTEM (see

Figure 2).

Figure 2a shows a dense arrangement of TiO₂ nanofibers, with rGO sheets visible as faint, translucent layers enveloping the oxide structures.

Figure 2b provides a higher-resolution view of an individual TiO₂ fiber, where lattice fringes are clearly observed. The inset highlights an interplanar spacing of ca. 0.35 nm, corresponding to the (101) plane of anatase TiO₂, consistent with XRD analysis.

Figure 2c shows a HRTEM image of a single-layer MoS₂ nanosheet. The atomically resolved honeycomb pattern indicates high structural quality and confirms the presence of monolayer MoS₂. The corresponding SAED pattern (inset) reveals a hexagonal diffraction arrangement, characteristic of the 2H-phase of MoS₂. The clear spots and absence of diffuse rings confirm high crystallinity and minimal structural defects.

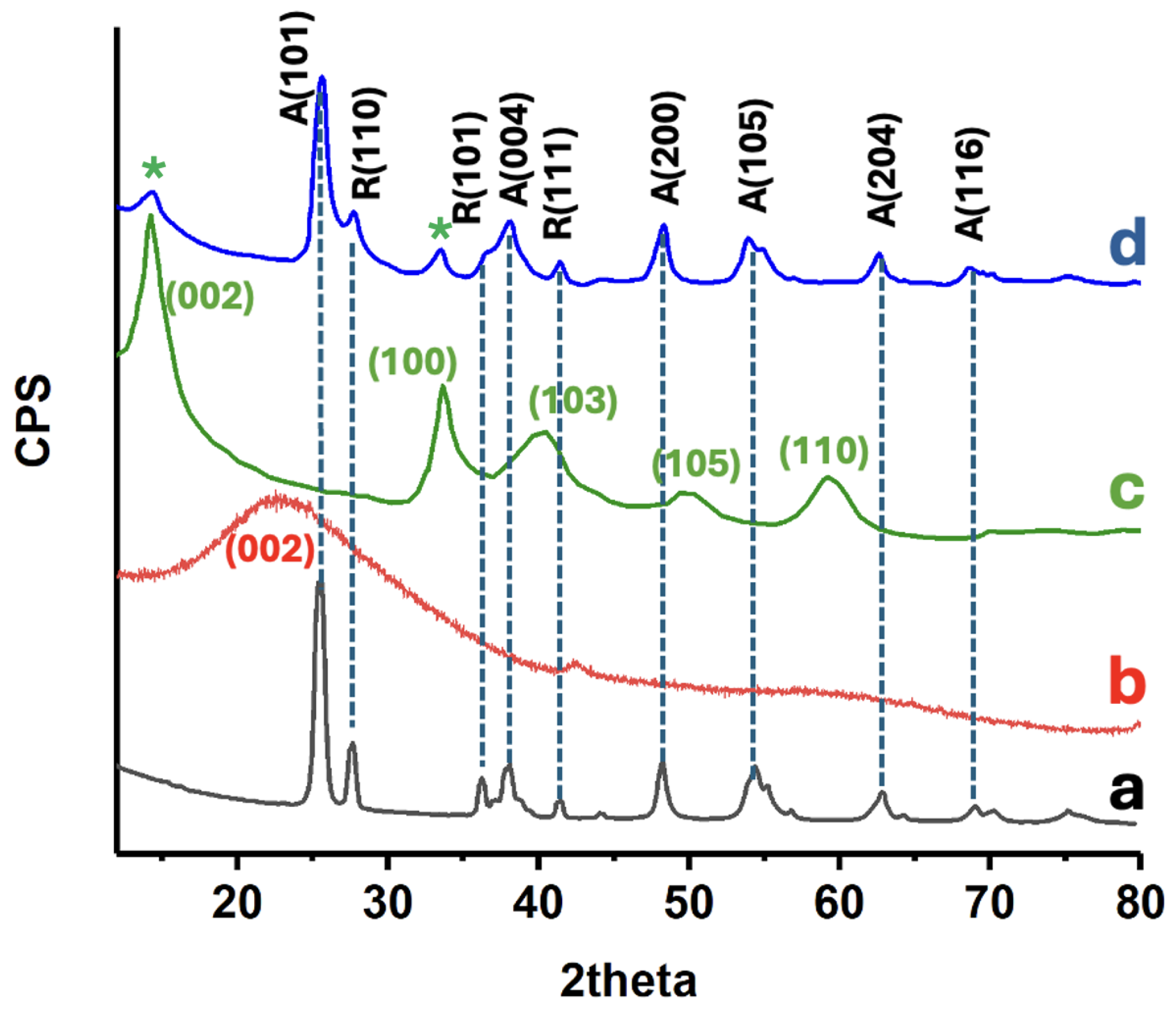

The crystalline phase composition of the prepared catalysts was examined by XRD (see

Figure 3). Pure P25 TiO₂ exhibits the most characteristic reflections of anatase TiO₂ at 25.5°, 38°, 48.2°, 54.4°, assigned to the (101), (004), (200), (105) planes of anatase, along with a rutile peak at ca. 27.7° [

21]. The TiO₂-rGO composite shows a virtually identical diffraction pattern to P25, indicating that the TiO₂ retained its crystalline structure after the graphene incorporation. Notably, no distinct new peaks attributable to graphene are observed; any potential (002) graphitic peak (~23°) is broadened or overlapped by the strong TiO₂ (101) peak [

21]. This is expected given the low loading and exfoliated nature of rGO, which lacks long-range order in stacking. Upon adding MoS₂, the composite XRD patterns still predominantly display TiO₂ reflections, but new low-angle peaks appear. In particular, a faint diffraction peak appears around 13–14° in the 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO sample (see asterisk), which is the (002) basal plane of hexagonal MoS₂ [

21]. An additional minor peak at ca. 33° can be discerned, matching the (100) plane of MoS₂ [

22] (see asterisk). The presence of these MoS₂ reflections confirms the successful incorporation of crystalline MoS₂ in the TiO₂-rGO matrix. Importantly, no significant shifts in the TiO₂ peak positions are detected upon MoS₂ or rGO addition, suggesting that Mo and S are not substituting into the TiO₂ lattice but rather MoS₂ and rGO form an intimate heterostructure on the TiO₂ surface. The combination of TiO₂ and MoS₂ diffraction features, with no extra impurity phases, evidences the formation of the intended composite.

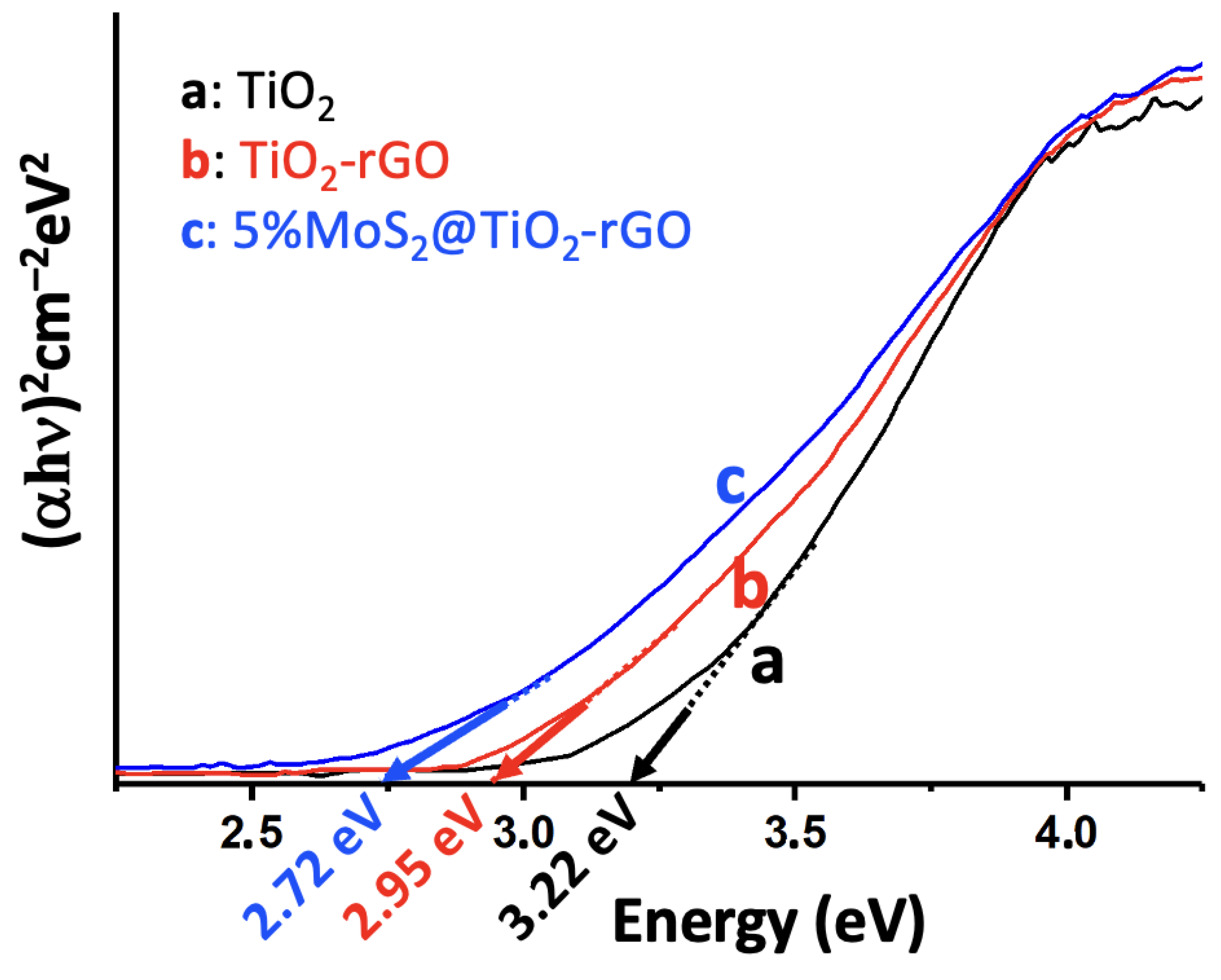

UV-Vis DRS was used to assess the optical absorption properties and bandgap energies of the catalysts (

Figure 4). Pristine P25 TiO₂ shows a strong absorption edge in the UV region (ca. 390 nm), corresponding to a bandgap of about 3.22 eV (consistent with anatase TiO₂) [

23]. Incorporation of rGO extends the absorption into the visible range (the TiO₂-rGO sample appears darker), with a red-shifted absorption edge. Tauc plot analysis (

Figure 4) indicates a reduced bandgap of ~2.95 eV for TiO₂-rGO, implying that the introduction of rGO facilitates visible-light absorption. This bandgap narrowing can be attributed to the electronic interaction between TiO₂ and the conductive rGO, which may introduce mid-gap states and promote the formation of an adsorption tail in the band structure. Upon loading 5% MoS₂ onto TiO₂-rGO, the absorption edge shifts further into the visible (up to ca. 455–460 nm), yielding an estimated optical bandgap of ca. 2.72 eV for the 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO composite [

23]. The progressive red-shift in the absorption onset from 3.22 eV (TiO₂) to 2.72 eV (MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO) confirms that the synergy of rGO and MoS₂ effectively extends the light-harvesting range of TiO₂ into the visible spectrum. This behavior is consistent with MoS₂ acting as a narrow-bandgap sensitizer (2H-MoS₂ has a much smaller bandgap of ~1.2–1.8 eV) and rGO acting as a photosensitizer and electron conduit [

23]. The black-colored MoS₂ nanosheets strongly absorb visible light and, when coupled with TiO₂, enable the heterostructure to use a greater portion of the solar spectrum [

23]. In addition, intimate contact between TiO₂ and MoS₂ (and rGO) can create sub-band-gap states or band bending at the interface, further contributing to the observed bandgap reduction [

24,

25]. The enhanced visible-light absorption evidenced by DRS directly correlates with improved photocatalytic activity under solar irradiation – by harvesting more photons in the visible range, the MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO catalyst can generate more charge carriers for pollutant degradation and H₂ evolution compared to pure TiO₂ [

26].

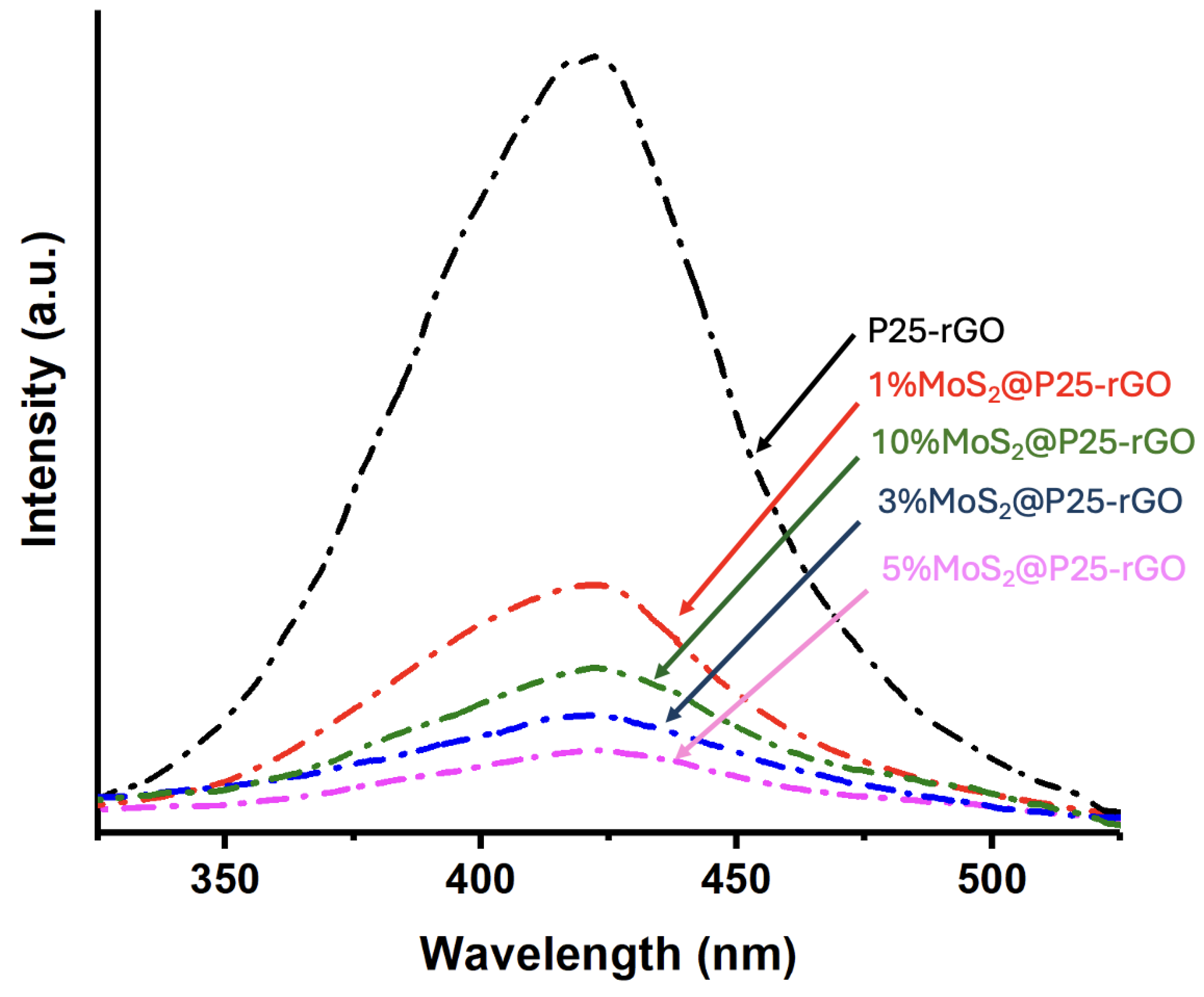

Photoluminescence spectroscopy was used to investigate the recombination behavior of photogenerated charge carriers in the photocatalysts.

Figure 5 displays the room-temperature PL emission spectra (λ

exc = 380 nm) for P25-rGO and its composites containing different MoS₂ loadings (1%, 3%, 5%, and 10%). The P25-rGO sample exhibits a strong and broad emission band in the UV-visible range, reflecting a high rate of radiative recombination of electron-hole pairs in the absence of additional charge separation pathways [

27]. Upon incorporation of MoS₂, the PL intensity generally decreases, indicating improved charge separation due to the synergistic effects of MoS₂ and rGO [

28]. The quenching trend follows the order: P25-rGO > 1%MoS₂@P25-rGO > 10%MoS₂@P25-rGO > 3%MoS₂@P25-rGO > 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO, with the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO composite showing the lowest PL intensity among all tested materials. Interestingly, the composite with 10% MoS₂ exhibits a higher PL intensity than those with 3% and 5%, suggesting that excessive MoS₂ content may not be beneficial. This could be due to agglomeration of MoS₂ layers or shielding effects that interfere with light absorption and charge transfer processes. Therefore, beyond an optimal loading, MoS₂ may hinder rather than enhance photocatalytic performance [

28]. Overall, the PL quenching confirms that moderate MoS₂ incorporation enhances charge carrier separation, while excessive loading could counteract this benefit. The significant PL reduction observed in 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO points to an optimal interfacial configuration between TiO₂, rGO, and MoS₂ that favors efficient charge extraction and transport [

22,

27,

28]. These results are consistent with the photocatalytic activity trends, as will be discussed in a later section, where the 5%MoS₂ composite also displayed the highest performance in both malathion degradation and hydrogen evolution, confirming that suppressed electron-hole recombination is a key factor in the enhanced reactivity of these ternary composites.

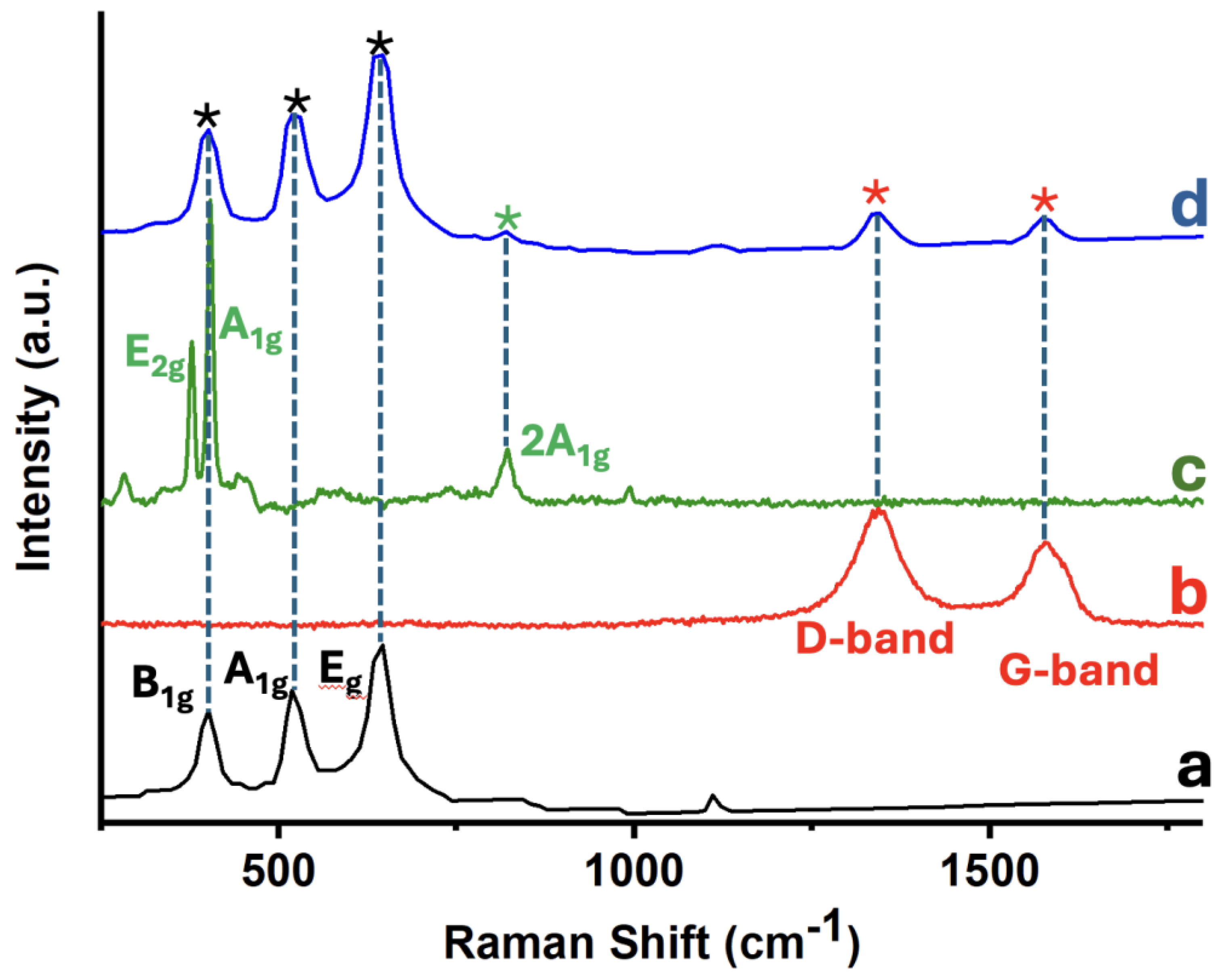

Raman spectroscopy was employed to investigate the structural features and component interactions within the 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO photocatalyst.

Figure 6 displays the Raman spectra of individual and composite materials: (a) TiO₂-P25, (b) rGO, (c) MoS₂, and (d) the ternary nanocomposite 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO. In the spectrum of pristine TiO₂-P25 (

Figure 6a), three characteristic vibrational modes of the anatase phase are clearly observed at approximately 398 cm⁻¹ (B

₁g), 518 cm⁻¹ (A

₁g + B

₁g), and 640 cm⁻¹ (E

g) [

21]. The spectrum of rGO (

Figure 6b) exhibits two prominent and broad peaks centered at ca. 1345 cm⁻¹ (D band) and 1590 cm⁻¹ (G band). The G band arises from the E

₂g vibrational mode of sp² carbon atoms (graphitic domains), while the D band originates from defect-activated breathing modes in disordered sp² structures [

21]. The observed intensity ratio (I

D/I

G ≈ 0.8–1.0) suggests a partially reduced graphene oxide with residual structural defects and oxygenated functionalities, being this an expected outcome of mild reduction protocols. In the MoS₂ spectrum (

Figure 6c), the in-plane E₂g¹ mode (ca. 379 cm⁻¹) and the out-of-plane A₁g mode (ca. 404 cm⁻¹) characteristic of the 2H phase of MoS₂ are clearly observed [

27]. The band separation (~25 cm⁻¹) is consistent with few-layer MoS₂, as larger separations are typical in thinner nanosheets due to decreased interlayer interactions [

22]. A weak overtone near 990 cm⁻¹, attributed to the 2A₁g mode, further supports the presence of multilayer character. The composite 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO (

Figure 6d) presents vibrational features from all three components. The anatase TiO₂ bands (black asterisks), the rGO D and G bands (red asterisks), and the MoS₂ peaks (green asterisks) are all clearly visible, confirming the coexistence of each constituent in the hybrid structure [

27]. Importantly, no new bands or significant peak shifts are observed, suggesting that no undesirable side reactions (e.g., Mo oxidation, Ti–C bonding, or carbide formation) occurred during synthesis. These results validate the structural integrity of the ternary composite and the successful assembly of TiO₂, rGO, and MoS₂ without phase degradation. The presence of well-defined and distinct vibrational signatures from each component further implies favorable interfacial contact, which may facilitate charge separation and transport, being critical factors in enhancing photocatalytic activity.

The specific surface areas of the synthesized materials were determined via nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. As summarized in

Table S1, the commercial P25 TiO₂ sample exhibited a surface area of 48 m²/g, consistent with its well-established properties. Upon incorporation of reduced graphene oxide (rGO), the surface area increased substantially to 483 m²/g, reflecting the textural contribution of rGO sheets, which help prevent TiO₂ agglomeration and promote a more open porous structure. Further addition of exfoliated MoS₂ led to a progressive rise in surface area, with values of 492, 496, 503, and 521 m²/g for the composites containing 1%, 3%, 5%, and 10% MoS₂, respectively. This trend suggests that the introduction of layered MoS₂ contributes to additional mesoporosity and helps maintain a high surface-to-volume ratio in the hybrid system. Interestingly, however, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, the composite with 10% MoS₂, despite having the highest BET surface area, exhibited inferior photocatalytic performance in both malathion degradation and hydrogen evolution. This highlights that surface area alone is not the determining factor for photocatalytic efficiency. At higher MoS₂ contents, excessive coverage or restacking of MoS₂ layers may hinder light absorption or block active sites, disrupting the optimal heterojunction structure necessary for efficient charge separation and transfer [

29].

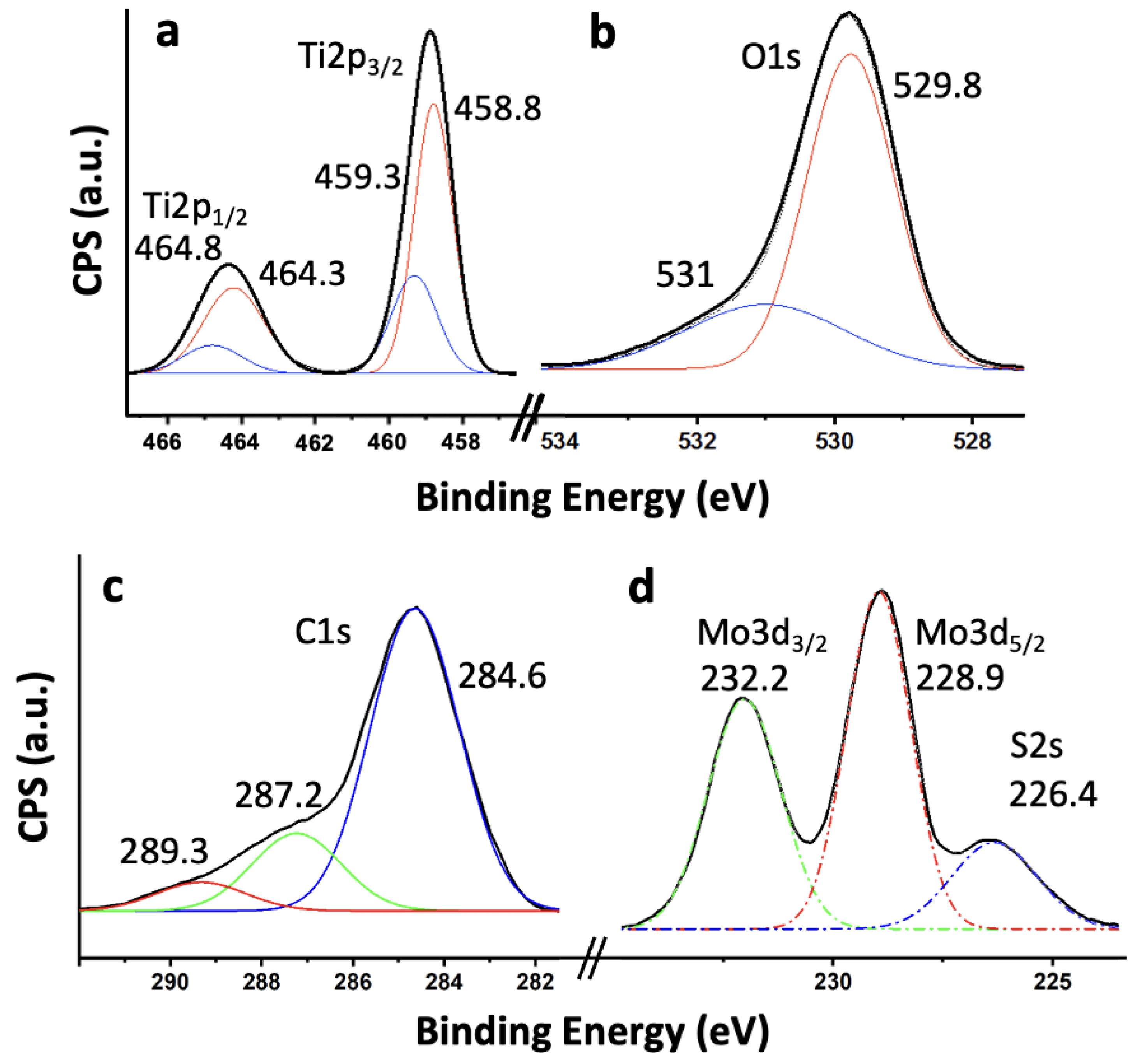

To investigate the surface chemical composition and oxidation states of the elements present in the 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO composite, high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analyses were performed (

Figure 7). The spectra confirm the presence of all key elements: Ti, O, C, Mo, and S. As shown in

Figure 7a, the high-resolution Ti 2p spectrum reveals two well-defined peaks at 458.8 eV and 464.3 eV, corresponding to Ti 2p₃/₂ and Ti 2p₁/₂, respectively, which are characteristic of Ti⁴⁺ in TiO₂ [

30,

31]. A minor shoulder at ca. 459.3 eV may indicate surface heterogeneity or electronic interactions with MoS₂ or rGO [

32], but no significant signal is observed at lower binding energies to suggest the presence of Ti³⁺ species, confirming that the TiO₂ structure remains predominantly in the fully oxidized state [

30]. The O 1s spectrum (

Figure 7b) shows a major peak at 529.8 eV attributed to lattice oxygen (Ti–O–Ti) and a secondary component at 531.0 eV, which corresponds to surface hydroxyl groups, adsorbed water, or oxygenated species on rGO [

33]. These surface oxygen functionalities are often associated with enhanced photocatalytic activity, as they can facilitate charge separation and radical formation [

33]. The C 1s spectrum (

Figure 7c) displays a dominant signal at 284.6 eV due to sp²-hybridized carbon atoms in the graphene lattice (C=C), along with minor peaks at 287.2 eV and 289.3 eV that can be assigned to carbonyl (C=O) and carboxyl (O–C=O) groups, respectively [

34,

35]. The relatively low intensity of these oxidized carbon species confirms the successful partial reduction of graphene oxide to rGO, while the residual functional groups are beneficial for improving interfacial bonding and electron transfer between components [

36]. The Mo 3d spectrum (

Figure 7d) exhibits two main peaks located at 228.9 eV (Mo 3d₅/₂) and 232.2 eV (Mo 3d₃/₂), characteristic of Mo⁴⁺ in MoS₂ [

30,

37]. No additional peaks are detected in the higher binding energy range (233–235 eV), ruling out the presence of significant amounts of oxidized Mo⁶⁺ species such as MoO₃ [

37]. In the same region, a broad feature at 226.4 eV is assigned to the S 2s signal [

38], further supporting the existence of sulfide species (S²⁻) in the MoS₂ lattice [

30,

38]. Altogether, the XPS results confirm the integration of TiO₂, MoS₂, and rGO into a ternary heterostructure with minimal chemical perturbation and strong interfacial interactions. The preservation of the oxidation states of Ti⁴⁺ and Mo⁴⁺, along with the partial reduction of rGO, is consistent with the enhanced photocatalytic behavior observed in degradation and hydrogen evolution experiments.

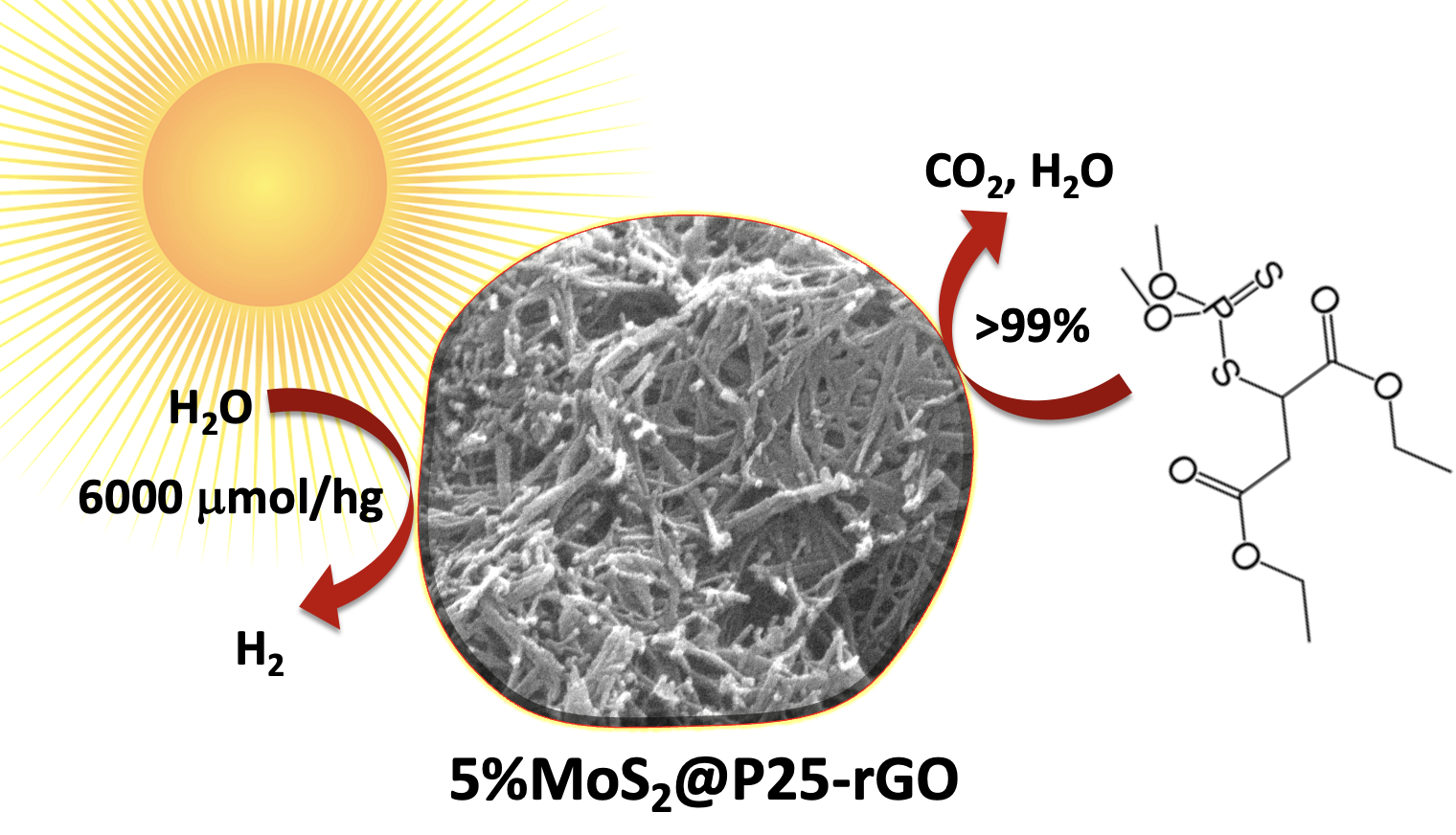

3.2. Photocatalytic Degradation of Malathion

To establish the optimal reaction conditions, a series of preliminary experiments were carried out using the most active material, 5%MoS₂@TiO₂-rGO, as the reference (see

Figure S1). These studies focused on evaluating the influence of key operational parameters, such as catalyst loading, initial pH of the solution, and the presence or absence of irradiation and oxygen on the degradation of malathion. The outcomes not only allowed us to determine the ideal experimental conditions for maximum photocatalytic efficiency but also served to confirm the photocatalytic origin of the degradation process through control experiments. These optimized parameters were subsequently applied in the evaluation of the remaining catalysts to ensure consistent and comparable performance assessments.

Figure S1a shows the effect of catalyst loading (from 0.4 to 1.8 g/L) on the photodegradation efficiency of malathion after 2 hours of UV-visible irradiation. An increase in catalyst loading led to improved degradation up to an optimal concentration of 1.0 g/L, where the degradation reached nearly 100%. This enhancement is attributed to the increased number of active sites and photon absorption capacity. However, beyond this concentration, the degradation efficiency decreased significantly. At 1.6 and 1.8 g/L, degradation dropped to around 65% and 50%, respectively. This decline is likely due to increased turbidity and light scattering at higher catalyst concentrations, which reduce light penetration and active photon flux within the suspension.

Figure S1b shows the influence of the solution pH on photocatalytic degradation efficiency. Experiments were performed over a pH range of 4 to 10, keeping all other conditions constant. The photocatalytic activity showed a marked dependence on pH, with maximum degradation (ca. 100%) occurring at neutral to slightly acidic conditions (pH 6–7). Below this range, especially at pH 4, degradation efficiency decreased sharply (~60%), likely due to reduced malathion adsorption or catalyst surface protonation. In alkaline media (pH > 8), the degradation also decreased, possibly due to hydroxide ion competition or destabilization of reactive oxygen species. These results suggest that the surface charge of the photocatalyst and the speciation of malathion both influence the reaction kinetics, and that near-neutral conditions are ideal for optimal degradation. To confirm the photocatalytic nature of the malathion degradation process, a series of control tests were conducted (

Figure S1c). These included: (i) photolysis (irradiation without catalyst), (ii) catalysis (catalyst in dark), and (iii) photocatalysis under anoxic conditions (argon-purged system). The results clearly show that significant degradation occurred only under full photocatalytic conditions (light + catalyst + air), where the malathion concentration dropped steadily over time, reaching almost complete mineralization within 120 minutes. In contrast, all control conditions showed minimal activity: photolysis and catalysis resulted in only minor losses (<15%), and the anoxic photocatalytic test demonstrated reduced efficiency, highlighting the essential role of dissolved oxygen as an electron acceptor in the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

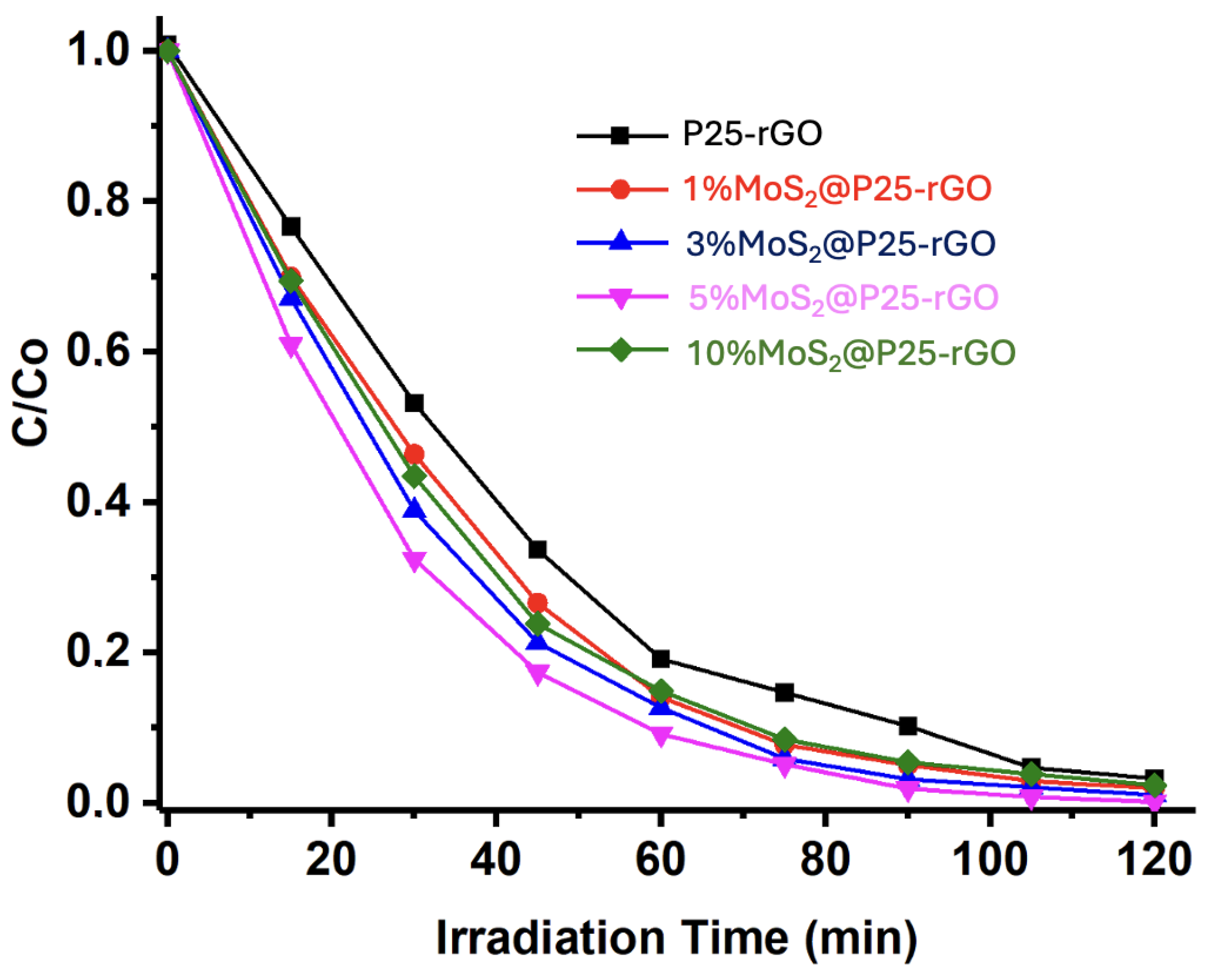

The photocatalytic activity of the synthesized materials was evaluated under UV-visible irradiation. The performance of the different catalysts—P25-rGO and MoS₂-modified composites with 1%, 3%, 5%, and 10% MoS₂—was compared under previously optimized reaction conditions (1.0 g/L catalyst loading and pH 7). As shown in

Figure 8, all MoS₂-containing composites outperformed the P25-rGO sample, demonstrating the beneficial effect of MoS₂ addition. Among the tested materials, 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO exhibited the highest degradation rate, achieving near-complete removal of malathion within 120 minutes. This enhanced activity is attributed to the synergistic interaction between TiO₂, rGO, and MoS₂, which promotes charge separation and broadens light absorption. The 3%MoS₂ and 1%MoS₂ composites also showed significant improvements compared to P25-rGO, but to a lesser extent. Interestingly, the 10%MoS₂@P25-rGO catalyst exhibited slightly lower activity than the 3% and 5% counterparts, likely due to excessive MoS₂ loading that can shield the active surface or induce recombination centers, corroborating the previously discussed BET and PL results.

To better understand the degradation mechanism of malathion using the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO composite, a series of scavenger experiments were carried out to identify the main reactive species involved (see

Figure S2). The addition of 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ), a selective quencher of superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻) [

39], resulted in a pronounced decrease in degradation efficiency, strongly suggesting that ·O₂⁻ species play a central role in the photocatalytic process [

39]. In contrast, the use of EDTA-Na₂, a hole (h⁺) scavenger [

40], led to negligible inhibition, indicating that direct oxidation by photogenerated holes is not the primary degradation pathway [

40]. Similarly, the addition of tert-butanol (t-BuOH), a hydroxyl radical (·OH) scavenger [

41,

42], caused only moderate suppression, pointing to a secondary contribution of ·OH radicals [

41,

42]. These findings are consistent with a mechanism in which photoexcited electrons, generated upon UV-visible irradiation of TiO₂, are efficiently transferred to MoS₂ and/or rGO, reducing adsorbed O₂ molecules to form superoxide radicals. The layered structure and intimate contact among TiO₂, MoS₂, and rGO facilitate efficient charge separation and migration across the heterostructure, possibly through a Type-II or Z-scheme charge transfer mechanism. MoS₂, with its suitable conduction band position, acts as an electron acceptor and stabilizer, while rGO provides a rapid electron transport pathway [

15,

43]. The result is enhanced generation of ·O₂⁻ species, which act as the dominant oxidizing agents responsible for the breakdown of malathion.

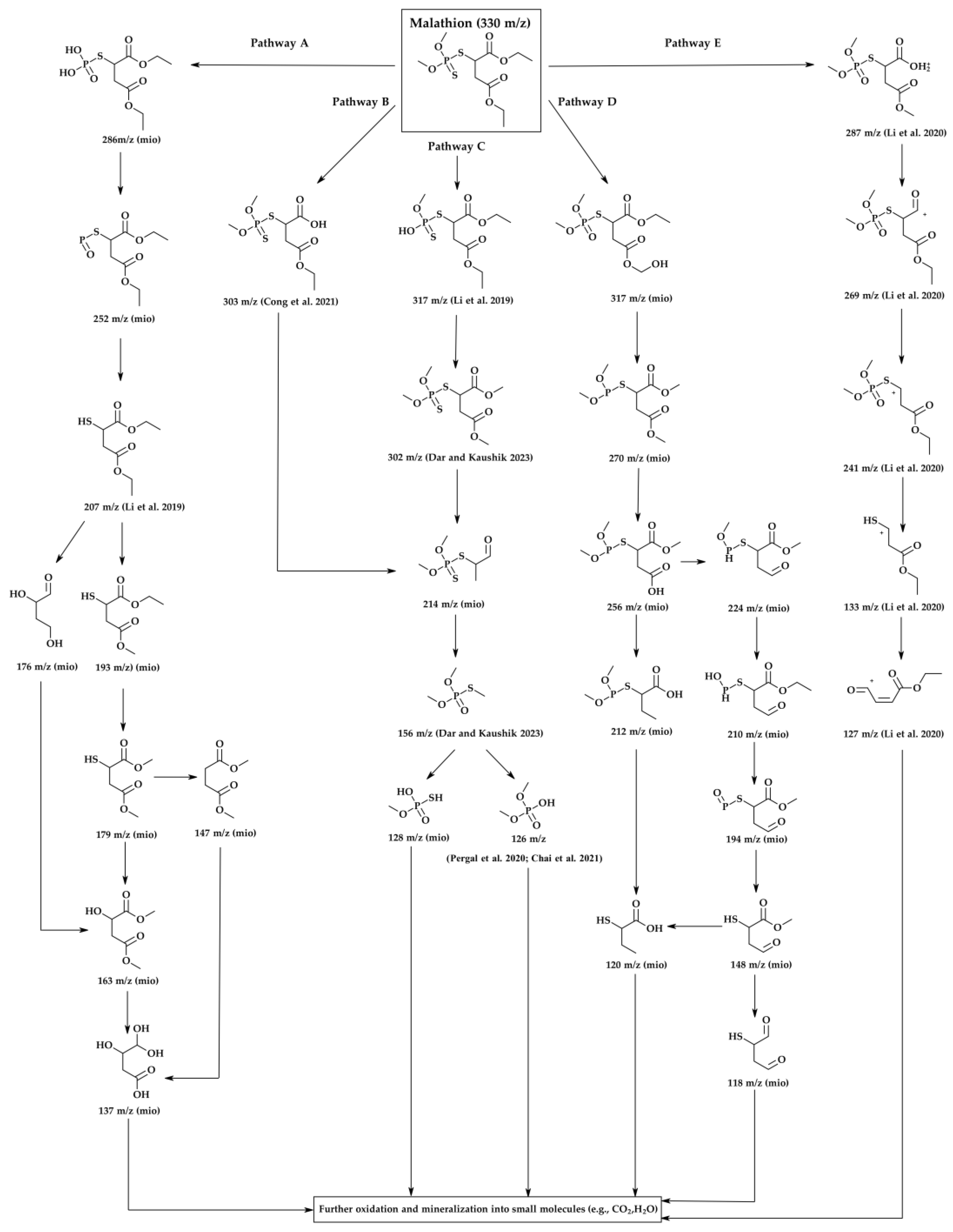

A detailed GC-MS analysis was conducted to elucidate the photocatalytic degradation pathway of malathion under UV-visible irradiation using the most active catalyst, 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO (

Figure 9). Reaction aliquots were collected at different irradiation times and analyzed to identify intermediate products based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratios. The parent compound, malathion (m/z = 330), was progressively decomposed through a sequence of hydrolytic and oxidative transformations. Five main degradation pathways (A–E) were proposed based on the detected fragments and their temporal evolution, as illustrated in

Figure 9. In Pathway A, hydrolysis of ester bonds and ring opening lead to the formation of lower-mass products [

44]. Pathways B and C involve oxidative desulfuration and P–S bond cleavage, producing fragments such as m/z 303, 302, 214, and 156 [

45,

46,

47,

48]. Pathway D comprises further oxidation and sulfur removal, generating species at m/z 317, 270, and 224 [

44], while Pathway E involves oxidative demethylation and side-chain fragmentation, yielding intermediate ions like m/z 287, 241, and 133 [

49]. The presence of low molecular weight fragments (m/z 128, 126, 137) indicates the occurrence of advanced oxidation processes, suggesting partial mineralization of malathion into CO₂ and H₂O, consistent with the mineralization trends observed in other TiO₂-based systems. Importantly, the formation of intermediates such as m/z 214 and 156 supports the predominant role of superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻) as oxidative agents, consistent with the radical trapping experiments discussed previously [

50,

51]. The heterostructure of TiO₂, MoS₂, and rGO favors efficient charge separation and facilitates electron transfer to molecular oxygen, sustaining the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). MoS₂, due to its narrow bandgap and appropriate conduction band alignment, acts as an effective electron sink, while rGO enhances electron transport and surface dispersion. This synergistic configuration promotes a Z-scheme or Type II-like mechanism that enhances photoinduced redox activity [

52]. Altogether, the results demonstrate that the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO catalyst enables efficient and multi-step degradation of malathion via concurrent hydrolytic and oxidative pathways, ultimately leading to detoxification of the pollutant and partial mineralization under mild conditions.

To ensure the practical viability of the developed photocatalysts, long-term operational stability and reusability were also evaluated. In this context, a recyclability study was conducted using the most active material, 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO, to assess its performance over successive degradation cycles. As shown in

Figure S3, the photocatalyst maintained nearly constant activity throughout ten consecutive runs, with only a slight decline of approximately 4.7% in degradation efficiency. This stability underscores the structural robustness and chemical durability of the MoS₂-rGO-TiO₂ heterojunction, confirming its suitability for repeated use in aqueous photocatalytic systems under UV-visible light irradiation.

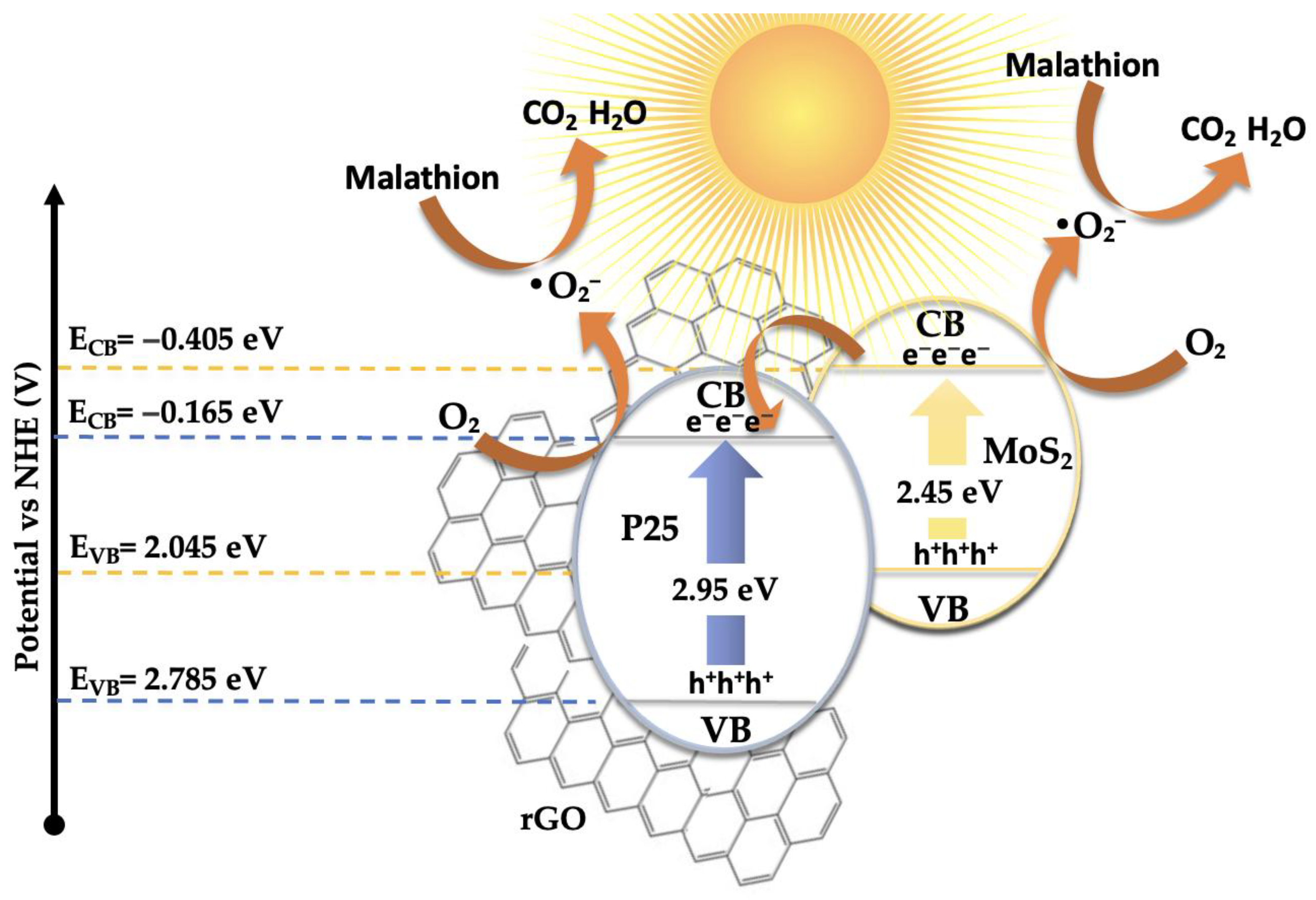

Based on all the results presented above, a plausible mechanism for the photocatalytic degradation of malathion has been proposed, as illustrated in

Figure 10. The electronic band structure and the migration direction of photogenerated charge carriers were estimated using the Mulliken electronegativity approach [

53,

54] in conjunction with the experimentally determined bandgap values (see

Figure 4). The conduction and valence band edge potentials were calculated according to the following equations:

where X is the absolute electronegativity of the semiconductor, E

C=4.50 eV is the energy of free electrons on the hydrogen scale [

55], E

g is the optical bandgap, and E

CB and E

VB are the potentials of the conduction and valence bands, respectively. Based on this model, the calculated band edge positions for P25-rGO are E

CB=−0.165 eV and E

VB=+2.785 eV, while for MoS₂ they are E

CB=−0.405 eV and E

VB=+2.045 eV. Under visible light irradiation, TiO₂ (P25) is largely inactive due to its wide bandgap (~3.2 eV) [

56]. However, MoS₂ and rGO, with narrower bandgaps, can absorb visible photons and become photoexcited [

57]. In the case of MoS₂, visible light promotes electrons from the valence band to the conduction band, leaving behind holes. These photoexcited electrons, due to the more negative conduction band of MoS₂ (–0.405 eV) relative to P25-rGO (–0.165 eV), can transfer to the TiO₂–rGO interface, where they are readily scavenged by molecular oxygen dissolved in the medium. This reduction leads to the formation of superoxide radicals (·O₂⁻), which are highly reactive and capable of oxidizing malathion. Simultaneously, holes remaining in MoS₂ and photoinduced holes in rGO may weakly contribute to oxidation, although scavenger experiments indicate that their role is secondary (see

Figure S2). Instead, hydroxyl radicals (·OH), generated from water or hydroxide oxidation by valence band holes in TiO₂, provide an additional oxidative pathway. The high surface area of rGO facilitates these processes by providing a large number of adsorption and reaction sites, while also improving charge mobility and suppressing recombination via rapid electron conduction [

58]. The dominant degradation route, as supported by radical quenching experiments and GC-MS analysis, is thus initiated by ·O₂⁻ radicals attacking the ester and phosphorothioate bonds in malathion, leading to a stepwise oxidative fragmentation into less toxic and lower-molecular-weight intermediates. This mechanism is fully consistent with the observed suppression of activity upon addition of 1,4-benzoquinone (a ·O₂⁻ scavenger), as well as with the enhanced photocatalytic activity shown by the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO composite compared to binary or unmodified systems. The proposed mechanism involves a type-II heterojunction [

59] in which MoS₂ and rGO sensitize the composite to visible light [

14], and the hierarchical structure promotes directional charge transfer from MoS₂ to TiO₂–rGO [

60]. This configuration enables the generation of reactive oxygen species—mainly superoxide and, to a lesser extent, hydroxyl radicals—which drive the oxidative degradation of malathion under solar-like irradiation conditions.

3.3. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production

As performed for the malathion photodegradation studies, a similar approach was employed to determine the optimal conditions for photocatalytic hydrogen production (

Figure S4). The influence of catalyst loading on the photocatalytic hydrogen production performance of the most active nanocomposite, 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO, was first investigated (

Figure S4a). The hydrogen evolution rate increased with catalyst concentration up to an optimal loading of 1.0 g L⁻¹, reaching a maximum yield of nearly 6000 µmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹. Beyond this point, the activity decreased, likely due to excessive light scattering, increased turbidity, and agglomeration of photocatalyst particles, which limit light penetration and reduce the number of accessible active sites. At lower catalyst dosages, the lower availability of surface-active regions similarly limits the overall rate of hydrogen generation. The effect of solution pH on hydrogen production was subsequently evaluated (

Figure S4b). The system exhibited optimal performance under neutral conditions (pH = 7), where both charge carrier separation and proton availability are favorably balanced. In strongly acidic environments (pH = 4), the excessive concentration of H⁺ ions can hinder charge mobility and promote recombination. Conversely, under alkaline conditions (pH = 10), the reduced proton concentration limits the supply of reactants necessary for H₂ evolution, leading to a significant drop in photocatalytic efficiency [

61]. To confirm the photocatalytic nature of the observed hydrogen generation, control experiments were carried out under different conditions (

Figure S4c). Negligible H₂ evolution was detected in the absence of either the catalyst or light, confirming that both components are essential for the reaction to proceed. These results validate that the process is strictly photo-driven and demonstrate the synergy between MoS₂, TiO₂, and rGO in facilitating efficient light-induced hydrogen evolution.

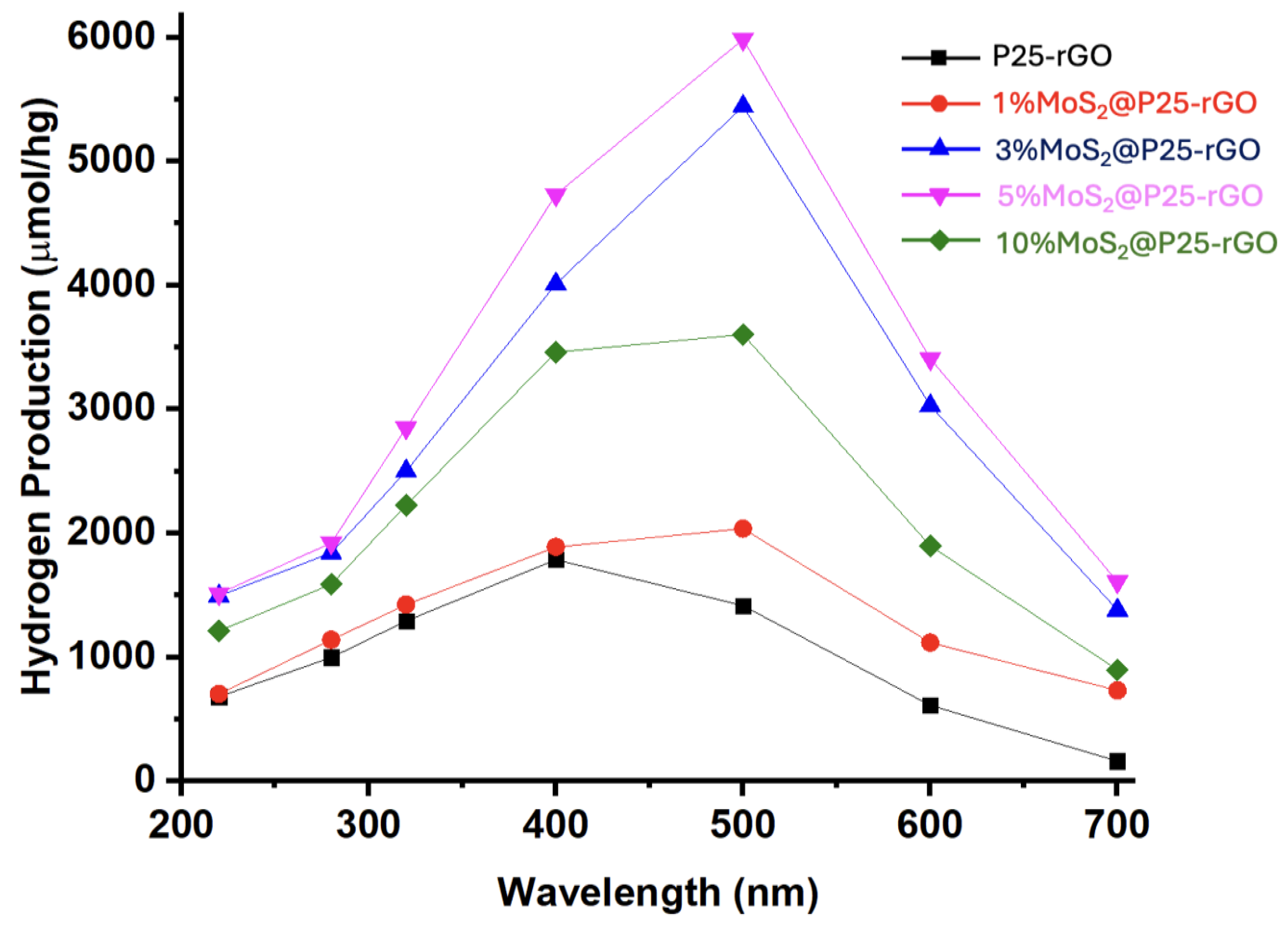

Figure 11 shows the wavelength-dependent hydrogen production profiles, clearly highlighting the superior photocatalytic activity of MoS₂-modified P25-rGO composites relative to the unmodified P25-rGO system. As a function of the incident photon energy, all catalysts show enhanced activity within the 300–500 nm range, where the absorption of UV and visible light is most efficient. Among the materials studied, the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO nanocomposite exhibits the highest hydrogen evolution rate, reaching nearly 6000 µmol g⁻¹ h⁻¹ at 500 nm. This outstanding activity can be rationalized by the formation of an efficient heterojunction between TiO₂, MoS₂, and rGO, which synergistically enhances charge separation, interfacial charge transfer, and visible-light absorption. TiO₂ serves as a stable wide-bandgap photocatalyst with strong UV absorption, while rGO provides a conductive platform that facilitates electron mobility, reduces charge recombination, and promotes light harvesting through its extended π-conjugated system [

62]. The incorporation of MoS₂ introduces a narrow-bandgap semiconductor with well-known catalytic activity for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), acting as a co-catalyst that offers abundant active edge sites and lowers the overpotential required for proton reduction [

63]. The observed activity trend—5%MoS₂ > 3%MoS₂ > 10%MoS₂ > 1%MoS₂ > P25-rGO—clearly indicates that a moderate MoS₂ loading is optimal for balancing these effects. At 1% MoS₂, the number of catalytically active sites is likely insufficient to significantly improve HER kinetics, while an excessive amount of MoS₂ (e.g., 10%) could lead to detrimental effects such as nanoparticle agglomeration, light shielding, and partial coverage of TiO₂ or rGO surfaces, thereby impeding photon absorption and reducing charge accessibility. Additionally, the decline in activity observed beyond 500 nm is consistent with the intrinsic bandgap limitations of the semiconductor components, as the photon energy becomes inadequate to excite electrons from the valence to the conduction band. These findings support that the careful modulation of MoS₂ content within the ternary composite is essential to maximize photocatalytic efficiency, and they emphasize the importance of interfacial engineering, band alignment, and light absorption optimization in designing next-generation nanostructured materials for sustainable hydrogen production.

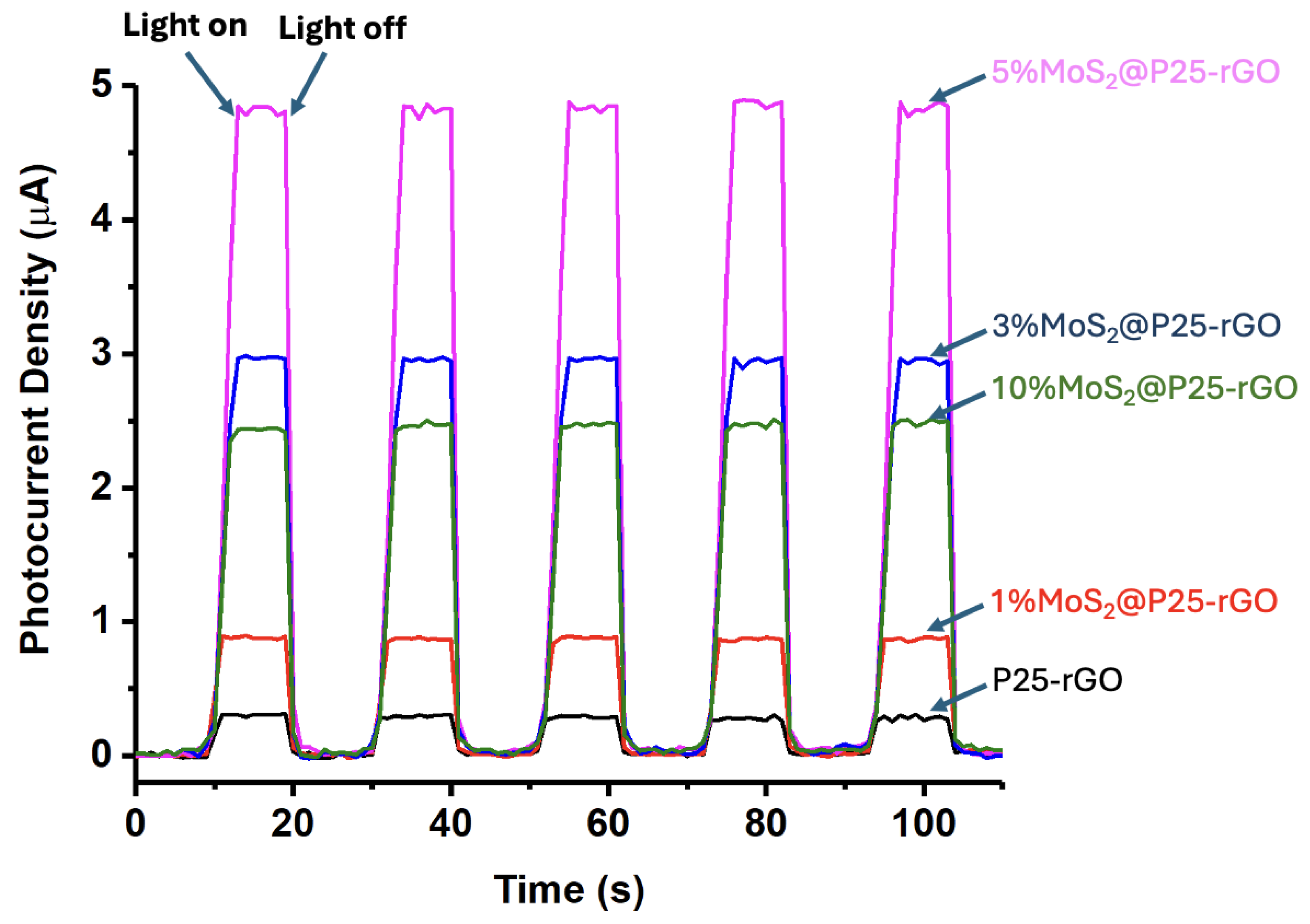

The long-term performance and mechanistic aspects of the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) using MoS₂@P25-rGO composites were further examined through a series of complementary experiments, including transient photocurrent measurements, scavenger assays, and recyclability tests. The photocurrent responses under chopped light illumination (

Figure 12) provide direct insight into the efficiency of photogenerated charge separation and transport. The 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO catalyst exhibited the highest photocurrent density (~5 μA), followed by 3%MoS₂@P25-rGO, 10%MoS₂@P25-rGO, 1%MoS₂@P25-rGO, and finally the unmodified P25-rGO. This order of photocurrent response precisely mirrors the trend observed in photocatalytic hydrogen production (

Figure 11), and also aligns with the photocatalytic activity for malathion degradation discussed in earlier sections. These consistent trends across multiple techniques confirm that the enhanced photoactivity of the 5%MoS₂ composite is directly linked to its superior charge separation and transport characteristics, which are facilitated by the synergistic interactions between MoS₂, P25, and rGO.

To further clarify the mechanistic pathway of HER, radical scavenger experiments were conducted using EDTA-Na₂, a known hole scavenger (see

Figure S5) [

40]. The addition of EDTA resulted in a significant enhancement in H₂ production across the tested wavelengths compared to the control without scavenger. This suggests that photogenerated holes act as recombination centers or engage in parallel oxidative reactions, and that their suppression enables a higher fraction of electrons to participate in proton reduction. These results support the hypothesis that MoS₂ not only facilitates electron transfer but also serves as an efficient co-catalyst for proton reduction, with rGO acting as an electron mediator that enhances interfacial conductivity [

15,

64].

In terms of practical application, the recyclability of the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO photocatalyst was evaluated over ten consecutive HER cycles (

Figure S6). The system retained 91.9% of its initial hydrogen production capacity after ten uses, with a performance drop of only 8.1%. This photostability underscores the structural robustness of the heterostructure and the durability of the active sites, confirming the feasibility of this material for long-term solar hydrogen generation. The strong interfacial bonding among MoS₂, TiO₂, and rGO components likely prevents leaching or deactivation, maintaining catalytic integrity over multiple uses. Taken together, these findings demonstrate the strong correlation between photocatalytic performance, charge transport efficiency, and material stability, positioning 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO as a promising candidate for sustainable hydrogen production.

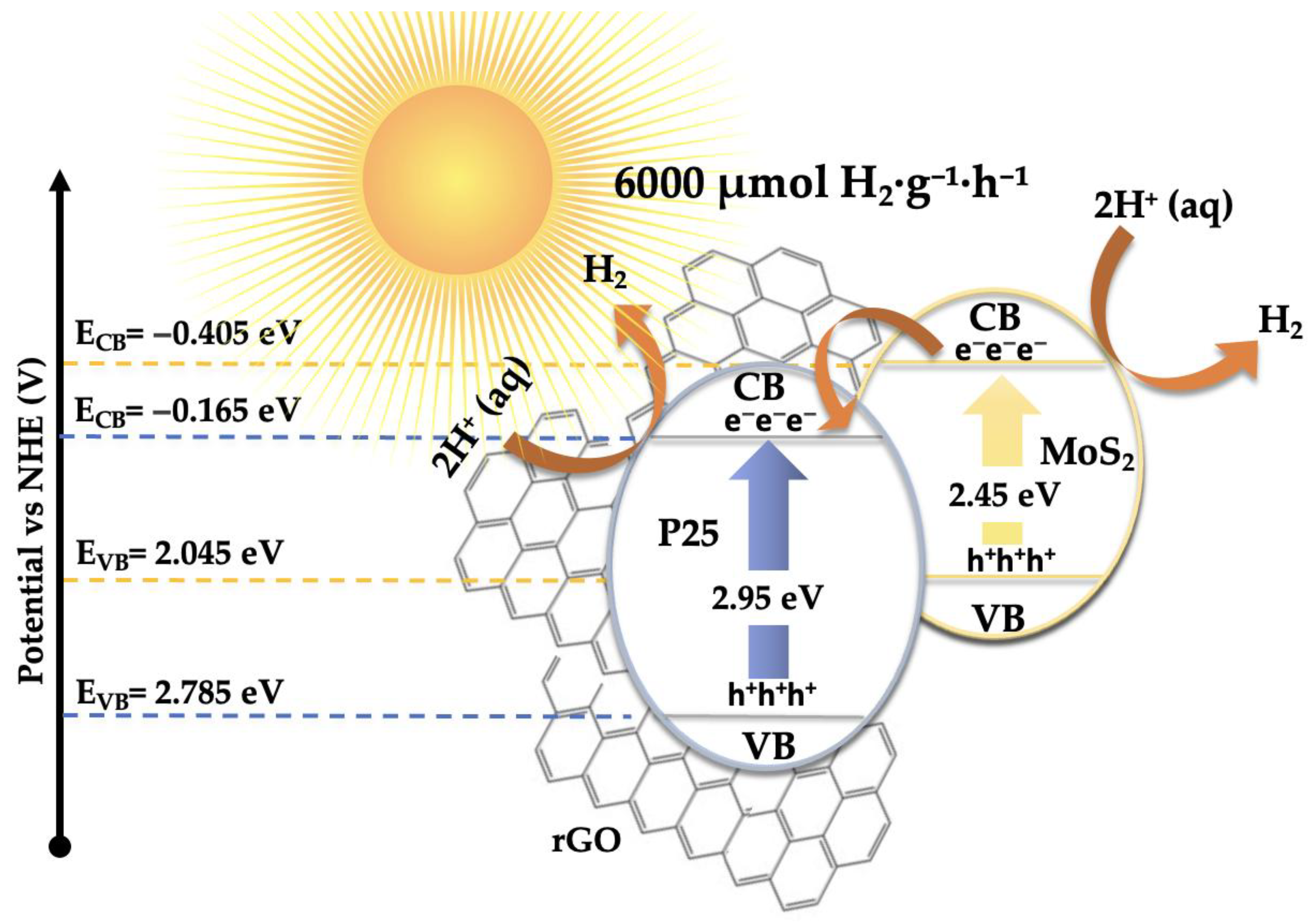

Based on the previously discussed results, a plausible mechanism has been proposed to explain the photocatalytic hydrogen evolution activity, consistent with the experimental observations (see

Figure 13). The outstanding H₂ production performance of the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO photocatalyst arises from the interplay between its three constituents—TiO₂ (P25), MoS₂, and reduced graphene oxide (rGO)—which together form a hierarchical heterostructure capable of efficient light absorption, charge separation, and catalytic functionality under visible-light irradiation. Among them, MoS₂ acts as the primary absorber of visible light. Upon irradiation, electrons are promoted from its valence band (VB) to its conduction band (CB), leaving behind photogenerated holes. TiO₂ (P25), with a wider bandgap (~3.2 eV), is less responsive to visible light; however, the incorporation of MoS₂ and rGO into the structure red-shifts the optical absorption of the composite, allowing some activation of TiO₂ under solar-simulated conditions. Moreover, interfacial interactions can induce localized mid-gap states, enhancing visible-light response. Band edge calculations based on Mulliken electronegativity theory suggest that the CB potential of MoS₂ (–0.405 eV vs NHE) is more negative than that of TiO₂ (–0.165 eV), while TiO₂ has a more positive VB (+2.785 eV), making it a potent oxidant. This band alignment favors a directional flow of charge carriers: electrons generated in TiO₂ or MoS₂ transfer toward MoS₂ and rGO, while holes accumulate on TiO₂ [

65]. Additionally, rGO acts as a conductive electron mediator that bridges MoS₂ and TiO₂, facilitating ultrafast charge transfer and delocalization, while also serving as a high-surface-area scaffold for active site dispersion [

36]. This spatial charge separation is further evidenced by the strong quenching of photoluminescence (PL) in the composite and its enhanced transient photocurrent response, which indicate suppressed electron-hole recombination. The 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO composite shows the highest photocurrent density and the lowest PL intensity among all tested samples, consistent with its superior H₂ production rates. At the MoS₂ surface, electrons reduce protons (H⁺) from the solution to generate H₂, taking advantage of the abundant and catalytically active edge sites on MoS₂. Meanwhile, the holes in TiO₂ oxidize sacrificial agents added to the solution, preventing recombination and sustaining the redox cycle. Scavenger experiments confirm that hole consumption significantly enhances H₂ evolution, highlighting the importance of maintaining separate pathways for electrons and holes. This mechanism is coherent with that proposed for malathion degradation, where the same spatial charge separation and vectorial charge migration were identified. In the absence of oxygen, electrons that would otherwise reduce O₂ (to form ·O₂⁻ for oxidative degradation) are now fully available for proton reduction, thus explaining the high H₂ evolution rates. The rGO sheets not only improve conductivity and dispersibility of MoS₂, but also ensure intimate contact among the components, which is essential for maintaining an efficient interfacial electric field and continuous charge flow [

66,

67]. Overall, the 5%MoS₂@P25-rGO catalyst operates via a cooperative mechanism that combines light absorption, charge generation, and catalytic functionality across its components. The result is a system capable of exploiting a broad portion of the solar spectrum while maintaining low recombination losses and high redox activity—delivering significant hydrogen generation rates and demonstrating its promise for sustainable solar fuel applications.