Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

13 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Evaluation of Photocatalytic Performance

3. Results and Discussion

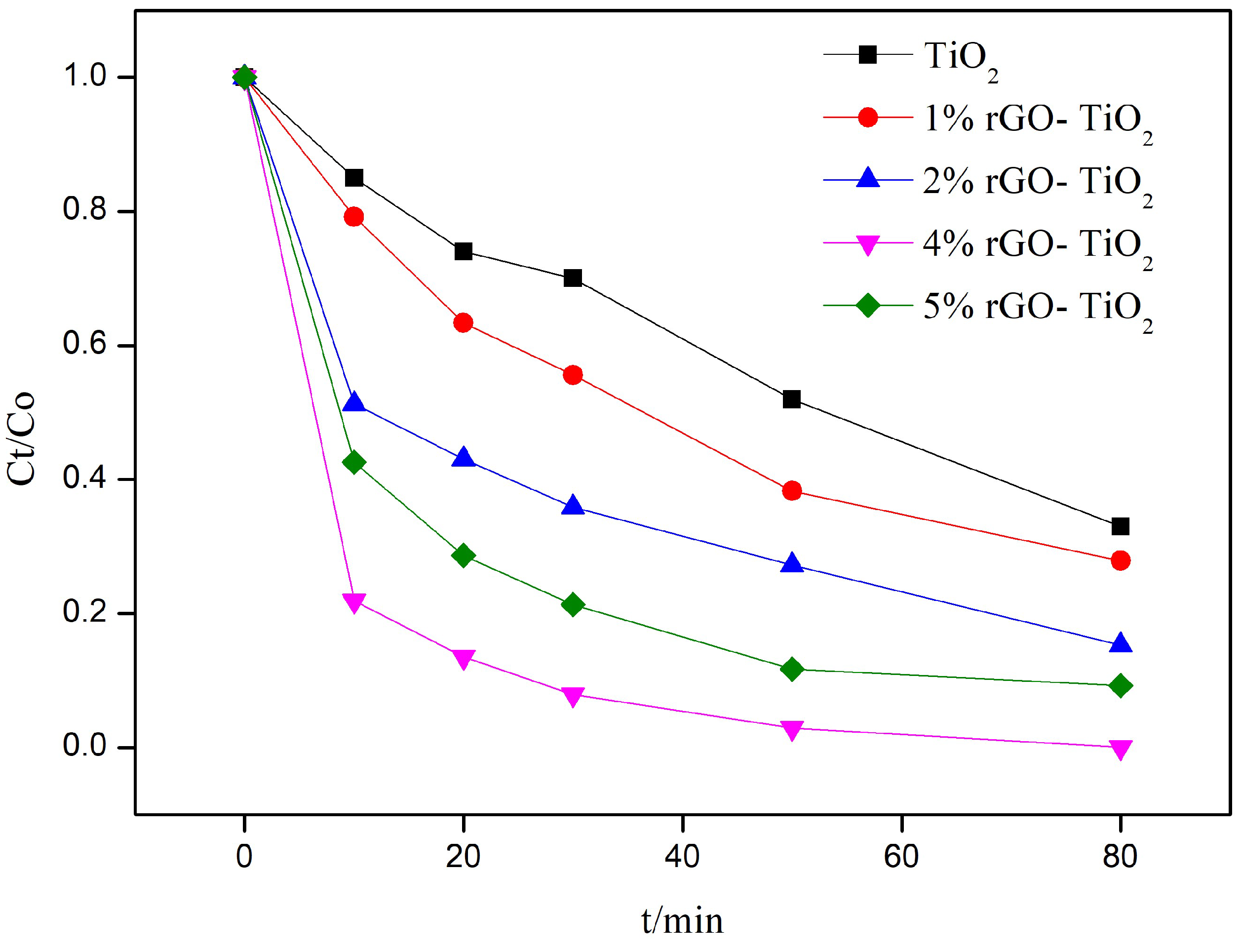

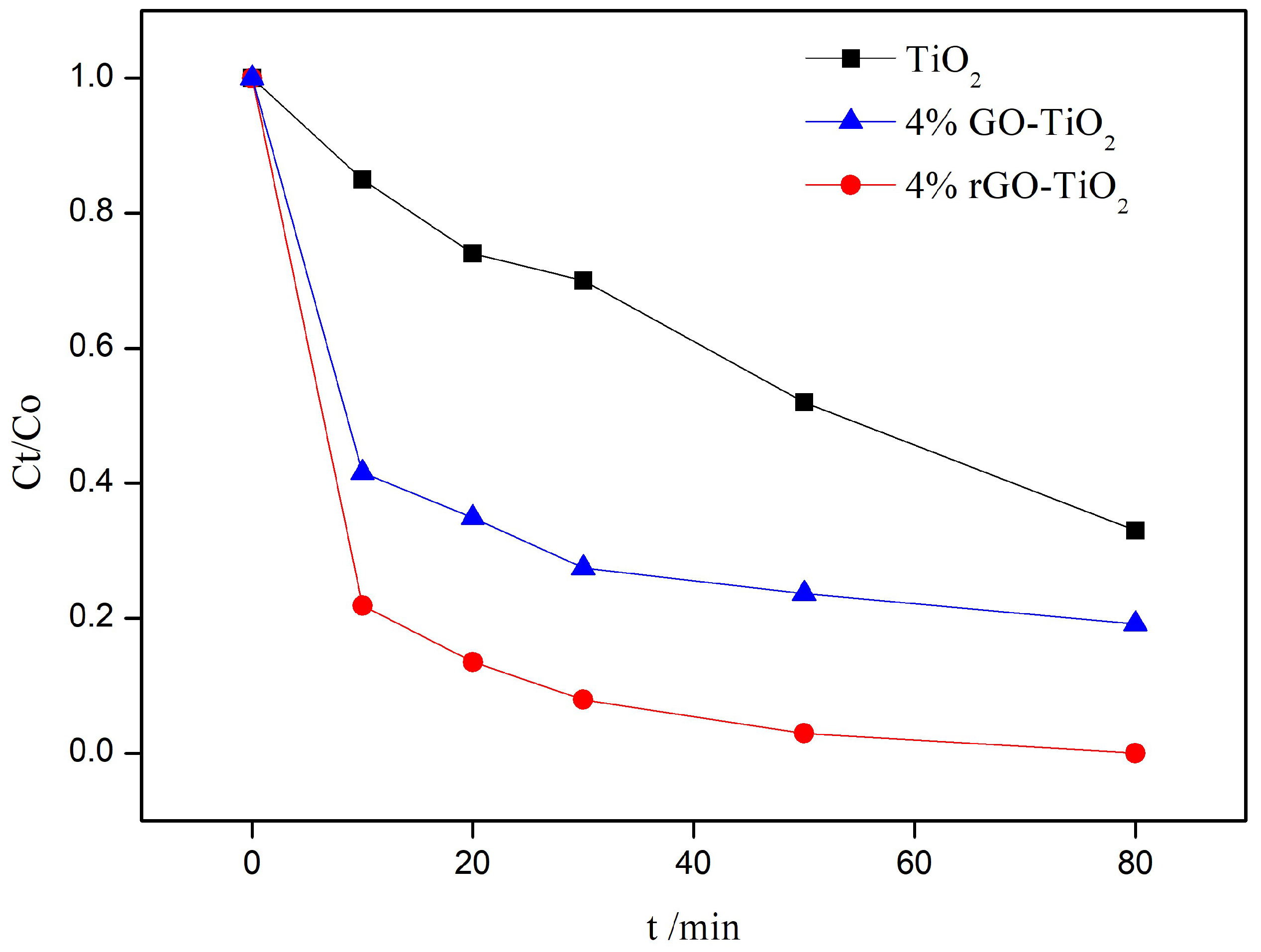

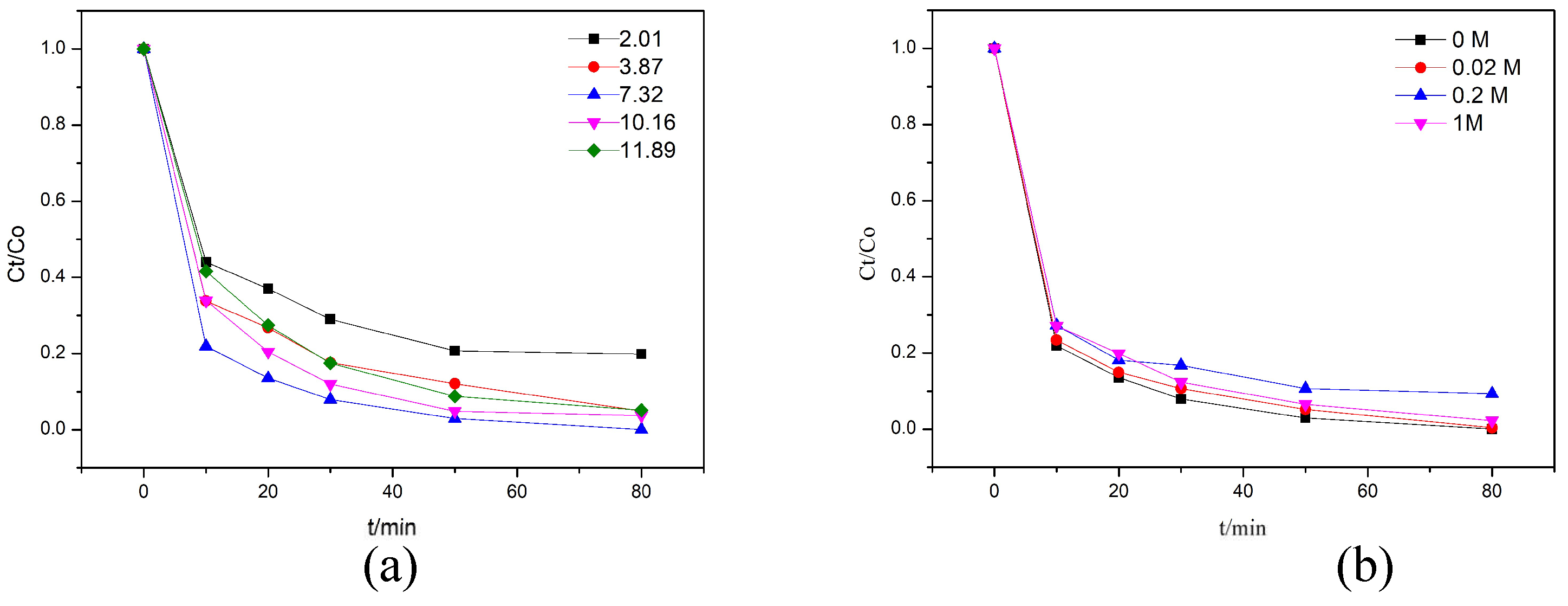

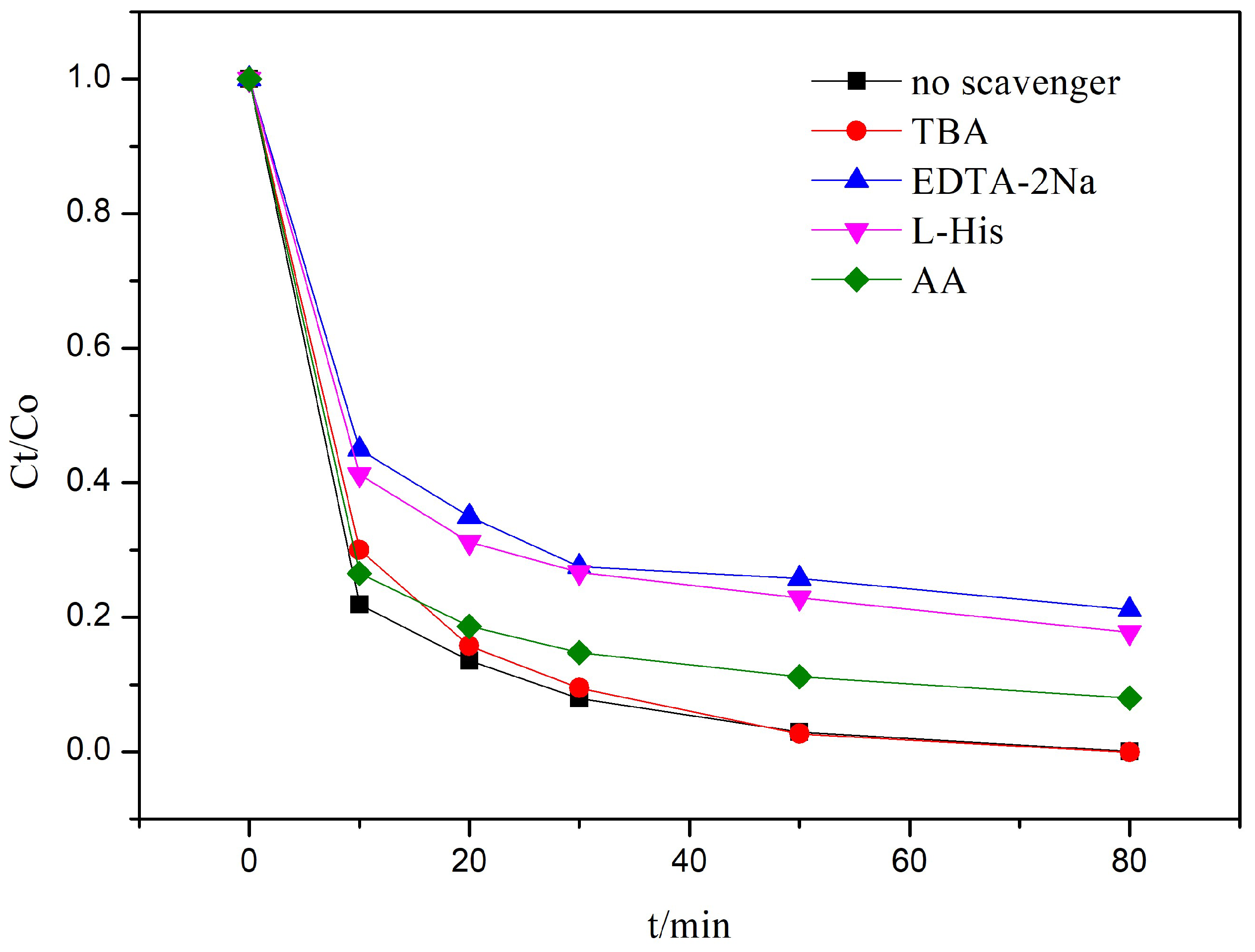

3.1. Photocatalytic Activity

3.2. Characterization Results

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kumari, H.; Sonia; Suman; Ranga, R.; Chahal, S.; Devi, S.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, S.; et al. A Review on Photocatalysis Used For Wastewater Treatment: Dye Degradation. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 1–46. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Noor, T.; Iqbal, N.; Yaqoob, L. Photocatalytic Dye Degradation from Textile Wastewater: A Review. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 21751–21767. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Manna, K.; Pradhan, P.; Sarkar, A.N.; Roy, A.; Pal, S. Review of Polymeric Nanocomposites for Photocatalytic Wastewater Treatment. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7, 4588–4614. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Zhou, C.; Ma, Z.; Ren, Z.; Fan, H.; Yang, X. ChemInform Abstract: Elementary Photocatalytic Chemistry on TiO2 Surfaces. ChemInform 2016, 47. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, H.; Duan, L.; Shen, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X. Influences of annealing atmosphere on phase transition temperature, optical properties and photocatalytic activities of TiO2 phase-junction microspheres. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 789, 1015–1021. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Hou, H.; Fang, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, L.; Chen, D.; Yang, W. Hydrogenated TiO2 Nanorod Arrays Decorated with Carbon Quantum Dots toward Efficient Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 19167–19175. [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Seger, B.; Kamat, P. V., TiO2-graphene nanocomposites.: UV-assisted photocatalytic reduction of graphene oxide. Acs Nano 2008, 2 (7), 1487-1491.

- Chen, C.; Cai, W.; Long, M.; Zhou, B.; Wu, Y.; Wu, D.; Feng, Y. Synthesis of Visible-Light Responsive Graphene Oxide/TiO2 Composites with p/n Heterojunction. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 6425–6432. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Guo, S.; Wang, P.; Xing, L.; Fang, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Dong, S. One-pot, water-phase approach to high-quality graphene/TiO2 composite nanosheets. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 7148–7150. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Wang, P.; Dong, S. Progress in graphene-based photoactive nanocomposites as a promising class of photocatalyst. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 5814–5825. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhao, D.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Y. Research on Photocatalytic Properties of TiO2-Graphene Composites with Different Morphologies. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 3263–3270. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Fang, J.; Liu, Q.; He, P., Preparation and photocatalytic degradation decoloring of TiO2 /reduced graphene oxide composites. Journal of Textile Research 2018, 39 (12), 78-83.

- Cano, F.J.; Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Ashok, A.; Olvera, M.d.l.L.; Velumani, S.; Kassiba, A. Mechanisms of dyes adsorption on titanium oxide– graphene oxide nanocomposites. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 21185–21205. [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Korzeniewski, C. L.; Wang, S.; Fan, Z., Comparing Graphene-TiO2 Nanowire and Graphene-TiO2 Nanoparticle Composite Photocatalysts. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2012, 4 (8), 3944-3950.

- Wang, R.; Shi, K.; Huang, D.; Zhang, J.; An, S., Synthesis and degradation kinetics of TiO2/GO composites with highly efficient activity for adsorption and photocatalytic degradation of MB. Scientific Reports 2019, 9 (1), 18744.

- Joy, J.; Krishnamoorthy, A.; Tanna, A.; Kamathe, V.; Nagar, R.; Srinivasan, S. Recent Developments on the Synthesis of Nanocomposite Materials via Ball Milling Approach for Energy Storage Applications. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9312. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H.; Guo, W.; Zeng, W. Hydrothermal synthesis of different TiO2 nanostructures: structure, growth and gas sensor properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2012, 23, 2024–2029. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Mu, L.; Qiang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yi, R.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yan, L.; Fang, H. Unexpected Selective Absorption of Lithium in Thermally Reduced Graphene Oxide Membranes. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2021, 38. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Yan, L.; Fang, H. Effect of Oxide Content of Graphene Oxide Membrane on Remarkable Adsorption for Calcium Ions. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2021, 38. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Shen, L.; Xing, Z.; Kou, X.; Duan, S.; Fan, L.; Meng, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zhao, M.; Mi, J.; Li, Z., Ti3+ self-doped mesoporous black TiO2/graphene assemblies for unpredicted-high solar-driven photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J Colloid Interface Sci 2017, 505, 1031-1038.

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, H.; Xu, B.; Weng, S.; Wang, S.; Tan, S.; Xie, Z.; Fang, F. FeCoNiMn/Ti electrode prepared by magnetron sputtering for efficient RhB degradation. Vacuum 2023, 214. [CrossRef]

- Quanju, Y.; Zeyan, W.; Ye, Z.; Manyun, L., Study on the performance of Cu2+ doped nano zero-valent iron for the oxidative degradation of Rhodamine B. Chemical Research and Application 2024, 36 (07), 1632-1638.

- Miao, Z.; Wang, G.; Li, L.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X., Fabrication of black TiO2/TiO2 homojunction for enhanced photocatalytic degradation. Journal of Materials Science 2019, 54 (23), 14320-14329.

- Hu, X.; Han, W.; Zhang, M.; Li, D.; Sun, H. Enhanced adsorption and visible-light photocatalysis on TiO2 with in situ formed carbon quantum dots. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 56379–56392. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q. Sulfate promotes the photocatalytic degradation of antibiotics by porphyrin MOF: The electron-donating effect of the anion. Environ. Funct. Mater. 2023, 2, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- MA Chaoge; FANG Guoli; TIAN Jing; ZHANG Gang; YAN Xianghui, Effect of Bi/Cl atomic ratio on the photocatalytic activities of TiO2/BixOyClz composites. Acta Materiae Compositae Sinica 2024, 43, 1-10.

- Štengl, V.; Bakardjieva, S.; Grygar, T.M.; Bludská, J.; Kormunda, M. TiO2-graphene oxide nanocomposite as advanced photocatalytic materials. BMC Chem. 2013, 7, 41–41. [CrossRef]

- Katal, R.; Salehi, M.; Farahani, M.H.D.A.; Masudy-Panah, S.; Ong, S.L.; Hu, J. Preparation of a New Type of Black TiO2 under a Vacuum Atmosphere for Sunlight Photocatalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 35316–35326. [CrossRef]

- Sukarman; Kristiawan, B.; Khoirudin; Abdulah, A.; Enoki, K.; Wijayanta, A.T. Characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles for nanomaterial applications: Crystallite size, microstrain and phase analysis using multiple techniques. Nano-Structures Nano-Objects 2024, 38. [CrossRef]

- Trapalis, A.; Todorova, N.; Giannakopoulou, T.; Boukos, N.; Speliotis, T.; Dimotikali, D.; Yu, J., TiO2/graphene composite photocatalysts for NOx removal: A comparison of surfactant-stabilized graphene and reduced graphene oxide. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2016, 180, 637-647.

- Ruidíaz-Martínez, M.; Álvarez, M. A.; López-Ramón, M. V.; Cruz-Quesada, G.; Rivera-Utrilla, J.; Sánchez-Polo, M., Hydrothermal Synthesis of rGO-TiO2 Composites as High-Performance UV Photocatalysts for Ethylparaben Degradation. 2020, 10 (5), 520.

- Yu, J.; Yu, H.; Cheng, B.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, X. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of TiO2 powder (P25) by hydrothermal treatment. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2006, 253, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-P.; Chen, H.; Nakaruk, A.; Koshy, P.; Sorrell, C. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Photocatalytic Activity of TiO2 Thin Films. Energy Procedia 2013, 34, 627–636. [CrossRef]

- Velardi, L.; Scrimieri, L.; Serra, A.; Manno, D.; Calcagnile, L. Effect of temperature on the physical, optical and photocatalytic properties of TiO2 nanoparticles. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Ohsaka, T.; Izumi, F.; Fujiki, Y. Raman spectrum of anatase, TiO2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1978, 7, 321–324. [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Lee, D.; Yoon, J.; Yin, Y.; Na Lee, Y.; Uprety, S.; Yoon, Y.S.; Kim, D.-J. Enhanced Gas-Sensing Performance of GO/TiO2 Composite by Photocatalysis. Sensors 2018, 18, 3334. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Haider, A.; Khalid, N.; Ali, S.; Ahmed, S.; Khan, Y.; Ahmed, N.; Zubair, M. Tuning the band gap of TiO2 by tungsten doping for efficient UV and visible photodegradation of Congo red dye. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018, 204, 150–157. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Tachikawa, T.; Fujitsuka, M.; Majima, T. Atomic Layer Deposition-Confined Nonstoichiometric TiO2 Nanocrystals with Tunneling Effects for Solar Driven Hydrogen Evolution. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1173–1179. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhao, M.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ghazzal, M.N.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Pan, D.; Wu, W. Facile Vacuum Annealing of TiO2 with Ethanol-Induced Enhancement of Its Photocatalytic Performance under Visible Light. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 14455–14461. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhao, M.; Que, X.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Ghazzal, M.N.; Colbeau-Justin, C.; Pan, D.; Wu, W. Facile Vacuum Annealing-Induced Modification of TiO2 with an Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 27121–27128. [CrossRef]

- Ran, P.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Zuo, P.; Li, B.; Li, X. J.; Cheng, X. Y.; Zhang, J. T.; Lu, Y. F., Redox shuttle enhances nonthermal femtosecond two-photon self-doping of rGO-TiO2-x photocatalysts under visible light. Journal of Materials Chemistry A 2018, 6 (34), 16430-16438.

- Song, X.; Li, W.; He, D.; Wu, H.; Ke, Z.; Jiang, C.; Wang, G.; Xiao, X. The “Midas Touch” Transformation of TiO2 Nanowire Arrays during Visible Light Photoelectrochemical Performance by Carbon/Nitrogen Coimplantation. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Liu, T.; Su, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, S. TiO2 nanotubes wrapped with reduced graphene oxide as a high-performance anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36580. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Song, H.; Meng, X.; Shen, T.; Sun, J.; Han, W.; Wang, X. Effects of Particle Size on the Structure and Photocatalytic Performance by Alkali-Treated TiO2. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 546. [CrossRef]

- Morgunov, V.; Lytovchenko, S.; Chyshkala, V.; Riabchykov, D.; Matviienko, D. Comparison of Anatase and Rutile for Photocatalytic Application: the Short Review. 1 2021, 18–30. [CrossRef]

| sample | SBET(m2/g) | pore volume (cm3/g) |

pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2 | 45.91 | 0.1152 | 10.27 |

| 4% GO-TiO2 | 66.44 | 0.2405 | 13.96 |

| 4% rGO-TiO2 | 58.28 | 0.2483 | 15.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).