1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a chronic skeletal disorder characterized by decreased bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, resulting in increased bone fragility and fracture risk. It is especially prevalent in postmenopausal women, though it affects millions of older adults of both sexes. In the United States alone, approximately 10 million people have osteoporosis (around 80% of them women), and an additional ~43 million have low bone density (osteopenia). This leads to a tremendous health burden: osteoporotic fractures- particularly of the hip, spine, and wrist- cause significant morbidity and healthcare costs exceeding $25 billion annually in the U.S. Given the aging population, improving osteoporosis management is a critical public health goal.

Current osteoporosis therapies aim to restore the balance between bone resorption and formation. The most common treatments include anti-resorptive drugs such as bisphosphonates (e.g., alendronate, risedronate) and the anti-RANKL antibody denosumab, as well as anabolic agents like teriparatide (parathyroid hormone analog). While these therapies can increase bone density and reduce fracture incidence [1,4,5,6], they have important limitations.

- -

Systemic delivery of current drugs is non-specific. The medications circulate throughout the body and do not concentrate specifically at sites of active bone loss. As a result, both healthy and diseased bone receive similar exposure. This lack of lesion specificity means that areas of high bone turnover (the most at-risk regions) are not selectively targeted by the therapy.

- -

Many osteoporosis drugs, especially bisphosphonates like risedronate, have very low oral absorption. Risedronate, for example, has an oral bioavailability under. Most of the dose is not absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract, which necessitates higher dosing and contributes to variability in patient response. Strict dosing requirements (fasting, water intake, remaining upright) are imposed to maximize absorption and reduce esophageal irritation.

- -

Due to their pharmacokinetics, bisphosphonates often require weekly or monthly dosing, and anabolic agents may require daily injections. Long-term adherence to these regimens is challenging for patients, and missed doses can reduce effectiveness. Oral bisphosphonates can cause gastrointestinal irritation if instructions are not followed, further complicating compliance.

- -

Chronic bisphosphonate therapy is associated with side effects such as gastrointestinal (GI) irritation or ulceration of the esophagus and hypocalcemia.

- -

In rare cases, osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femur fractures. RANKL inhibition (denosumab) can lead to suppressed bone remodeling to the extent that, upon discontinuation, there is a rebound increase in bone resorption and risk of vertebral fractures. These risks are exacerbated by the drugs’ lack of targeting, exposing the entire skeleton and other tissues to their effects.

Given these limitations, there is a compelling need for precision drug delivery approaches in osteoporosis treatment. An ideal therapy would selectively deliver anti-resorptive drugs to bone lesions (areas of active pathological resorption) while sparing normal bone, thereby maximizing efficacy where needed and minimizing systemic exposure and side effects. Targeted delivery could also improve the effective concentration of drug at the desired site, potentially allowing lower total doses and less frequent administration.

Nanomedicine offers a promising strategy to address the challenges above by improving drug targeting and controlled release. In recent years, researchers have explored nanoparticle (NP) carriers for osteoporosis drugs. For example,[3] developed mPEG-coated hydroxyapatite nanoparticles loaded with risedronate, demonstrating improved oral bioavailability and increased bone mineral density in animal models. This approach leveraged hydroxyapatite (HA) as the NP core to inherently target bone mineral, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating to stabilize the particles. However, the system had only a single targeting mechanism (mineral affinity) and released the drug passively, without a mechanism to confine release to diseased sites. In another study,[2] investigated calcium-based nanoparticles that accumulate in bone via mineral interactions. While these NPs achieved enhanced bone targeting, they lacked specificity for lesion sites versus normal bone and did not incorporate on-demand drug release. Similarly,[1] reported alendronate-functionalized PLGA nanoparticles for bone targeting. Alendronate (a bisphosphonate) on the NP surface provided general affinity for bone tissue, leading to effective bone accumulation of the carrier. Yet this system did not include a controlled release trigger, meaning the drug could diffuse out even in off-target locations. These studies highlight the potential of nanocarriers to improve bone delivery, but also reveal gaps in current nanoparticle strategies: typically, only one targeting method is used at a time, and there is a lack of microenvironment-sensitive release control. Consequently, existing formulations may still deliver drug to both healthy and diseased bone and may release drug prematurely in circulation or other tissues.

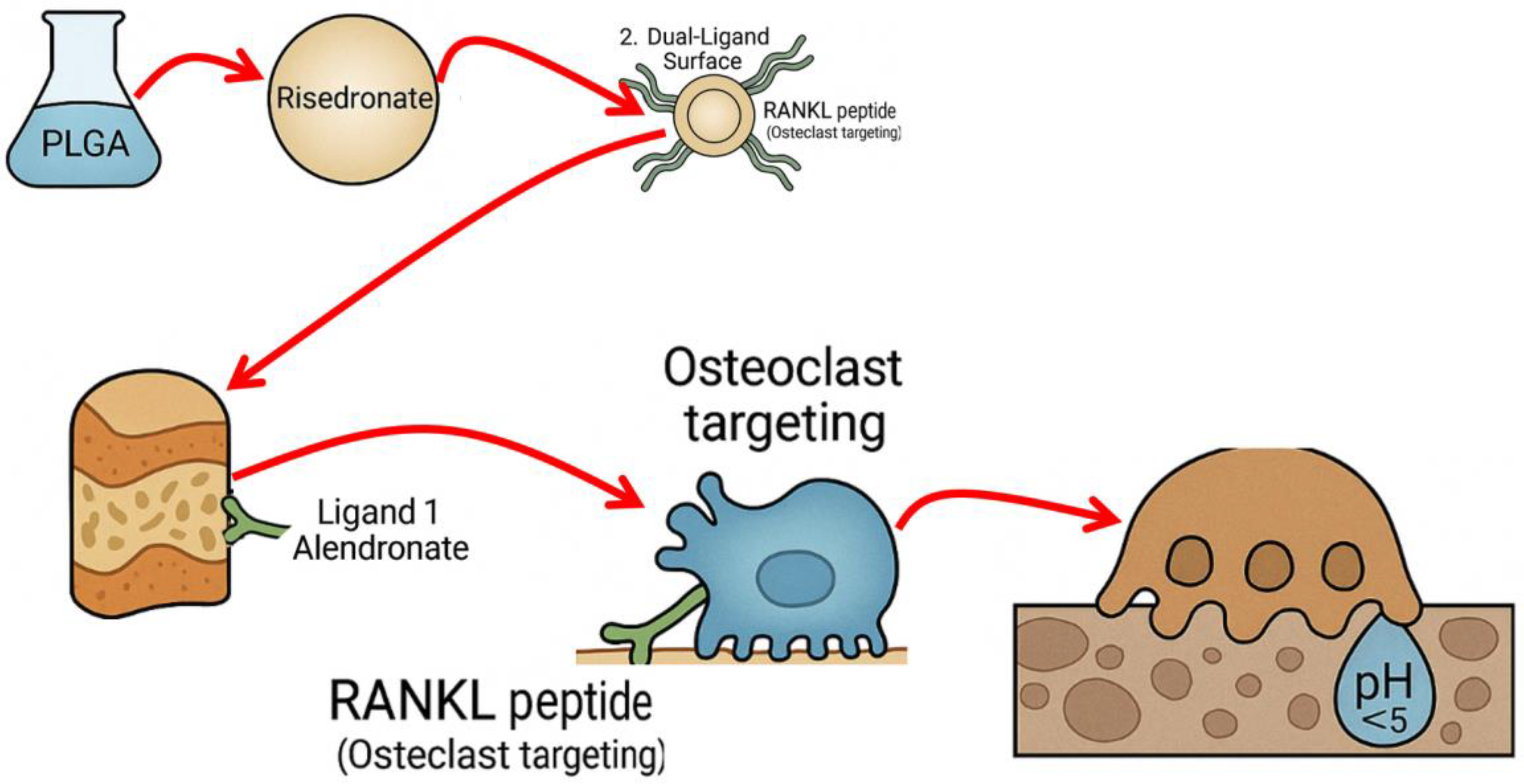

To overcome these gaps, we propose a multi-functional nanoparticle that combines dual targeting with stimuli-responsive drug release. Our central hypothesis is that integrating two distinct targeting ligands with a pH-responsive polymeric nanoparticle will enable preferential delivery of risedronate to osteoporotic lesion sites and reduce off-target effects. By concentrating the drug at sites of pathological bone resorption and activating its release only in the acidic conditions of those sites, we aim to maximize the therapeutic impact on diseased bone while minimizing exposure to healthy bone and other tissues.

The objective of this project is to design and test a PLGA-based nanoparticle for oral delivery of risedronate that (1) homes to bone surfaces (via a bone-binding ligand), (2) specifically recognizes osteoclast-rich or high bone turnover areas (via a second, lesion-targeting ligand), and (3) releases risedronate in a controlled fashion in response to the low pH environment of active bone resorption. In the following sections, we describe the proposed nanoparticle design and composition, the methods for its synthesis and functionalization, and our plans to evaluate its performance through comprehensive in vitro and in vivo experiments.

1.1. Design

The proposed therapeutic system is a dual-targeted, pH-responsive nanoparticle engineered for precision delivery of risedronate to osteoporotic bone.

Figure 1 illustrates the design: a drug-loaded PLGA core decorated with two targeting ligands and coated with a pH-sensitive polymer layer.

1.2. Polymer Core

At the heart of the nanoparticle is a biodegradable core made of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA). PLGA is an FDA-approved, biocompatible polymer widely used in drug delivery systems due to its tunable degradation rate and safety profile. Risedronate (a potent bisphosphonate anti-resorptive drug) will be encapsulated within this PLGA matrix. By encapsulating risedronate, we protect it from the harsh gastrointestinal environment and improve its delivery to the bloodstream and bone. The PLGA matrix also allows a controlled release of the drug as it degrades. Importantly, encapsulation prevents the risedronate from interacting with tissues until the nanoparticle reaches the target site, which can help avoid the local GI irritation that free bisphosphonates cause. The size of the PLGA nanoparticle will be on the order of a few hundred nanometers or less (optimally ~100 nm) to facilitate uptake and distribution. This size range is small enough to cross biological barriers (with assistance, discussed below) but large enough to carry a significant drug payload and multiple surface functional groups.

1.3. Targeting Ligands

To direct the nanoparticles to bone tissue, we will functionalize their surface with a bone-binding ligand. We propose using a bisphosphonate moiety for this role, taking advantage of the natural affinity of bisphosphonates for hydroxyapatite (the mineral component of bone). For example, a molecule like alendronate (which has a primary amine) can be chemically conjugated to the surface of the NP. Once in circulation, this ligand will cause the nanoparticles to accumulate in bones by adsorbing onto exposed hydroxyapatite surfaces (similar to how free bisphosphonates target bone). This provides the first level of targeting – a passive affinity for bone mineral that will preferentially localize the NP to the skeleton, especially areas undergoing remodeling where fresh mineral is exposed. The bone affinity ligand ensures that a high fraction of the injected or absorbed nanoparticles will leave circulation at bone surfaces, rather than distributing evenly to all tissues.

Simply reaching bone is not sufficient, because healthy bone surfaces would also attract bisphosphonate-coated NPs. Thus, a second active targeting ligand is incorporated to achieve specificity for osteoporotic lesions or active resorption sites on bone. We propose to use a ligand that recognizes markers of osteoclasts or regions of high bone resorption. One example is a peptide derived from RANKL (Receptor Activator of NF-κB Ligand) or a RANKL-mimicking sequence that can bind to the RANK receptor on osteoclasts. The idea is to guide nanoparticles to osteoclast-rich areas: if an osteoclast or pre-osteoclast is actively resorbing bone, the nanoparticle decorated with such a peptide could bind to the cell (or to RANKL expressed in the local environment). This lesion-specific ligand provides a second level of targeting: among the bone surfaces that the NP encounters, it will preferentially bind and be retained at sites where osteoclast activity is high (as opposed to quiescent bone surfaces). Alternatives for this targeting element could include small molecules or antibodies/fragment that target other osteoclast surface markers or inflammatory signals upregulated in osteoporosis. For instance, certain peptides (like the heptapeptide ASGLSFP known as LLP2A targeting activated alpha4beta1 integrin on osteoclast precursors) or aptamers could be used. In this proposal, we will use the shorthand “RANKL peptide” to denote the osteoclast-targeting ligand (with the understanding that we will design or choose a peptide that binds specifically to a component of the osteoclast or its niche). This dual ligand approach (mineral-affinity + cell-specific) is a key innovation to ensure NP accumulation at diseased bone sites: the first ligand brings NPs to bone in general, and the second confers an additional binding in areas of active disease, effectively discriminating lesions from normal bone.

1.4. Stimuli Responsiveness

The entire nanoparticle (PLGA core with ligands) will be coated with a pH-responsive polymer layer. The purpose of this layer is to keep the nanoparticle intact (and the drug unreleased) under normal physiological conditions (neutral pH ~7.4), but to rapidly release the drug in the acidic microenvironment of active bone resorption (pH ~6.5 or lower) or within osteoclast intracellular vesicles (pH ~4.5–5 in lysosomes). We are considering two candidate polymers for this coating: poly(L-histidine) and chitosan (or a chitosan derivative). Poly(L-histidine) is a polymer with an imidazole side chain that is largely uncharged and hydrophobic at pH 7.4, but becomes protonated and hydrophilic at pH ~6.0–6.5 (histidine pK_a ≈ 6.0). In a coating, polyhistidine can form a barrier at neutral pH (preventing drug diffusion out of the NP) but will destabilize or swell in a more acidic environment, thus triggering drug release. Chitosan, on the other hand, is a polysaccharide that is insoluble and forms a film at neutral-basic pH, but becomes protonated and dissolves in acidic conditions (pK_a of chitosan ~6.3). A chitosan derivative (e.g., trimethyl chitosan) could similarly remain intact at neutral pH and dissolve in mild acid. Both options achieve the same functional goal: the polymer coat acts as a pH-sensitive “gatekeeper” for drug release. Under physiological pH (bloodstream ~7.4, or healthy bone ~7.4), the coat stays relatively solid or collapsed, preventing premature leakage of risedronate. When the nanoparticle reaches an osteoclast resorption site, where the local pH is slightly lower (osteoclasts secrete protons to dissolve bone mineral, creating pH ~6.5 at the bone surface), or if the NP is endocytosed by an osteoclast and enters an acidified endosome (pH ~5–6), the polymer becomes protonated, disrupting the coating and allowing the encapsulated drug to diffuse out. This mechanism concentrates the release of risedronate exactly where osteoclasts are active, inducing maximal anti-resorptive effect at that location. Crucially, if a nanoparticle with this coating attaches to a bone surface that is not actively being resorbed (normal bone area with pH ~7.4), the coat should remain intact and the drug will largely not be released – the nanoparticle may eventually detach and circulate away or only release drug when it eventually encounters an acidic environment (such as uptake by an osteoclast or acidic organ). This pH-triggered behavior adds a layer of specificity in function: even after the physical targeting by the ligands, release is further restricted to diseased microenvironments.

In addition to the above components, the nanoparticle surface will include polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, a common “stealth” coating used to prolong circulation time and improve stability. We plan to incorporate PEG in one of two ways: either by using a PLGA-PEG copolymer to form the NP core (so that some PEG is already present on the surface), or by grafting PEG chains along with the pH-sensitive polymer during the surface modification step. PEGylation will serve multiple purposes: it will help the nanoparticle avoid rapid clearance by the mononuclear phagocyte system (i.e., reduce opsonization by plasma proteins and uptake by macrophages), and it can also protect the nanoparticle from premature degradation or aggregation (especially in the acidic stomach environment for oral delivery). PEG, being hydrophilic, can also improve the mucosal penetration and diffusion of the particles. We will ensure that PEG chains do not interfere with the targeting ligands by controlling their length or distribution – for example, using heterofunctional PEG that attaches to PLGA and presents a ligand at the distal end, or by attaching ligands in the gaps between PEG chains.

1.5. Delivery Method

The ultimate route of administration for our nanoparticle is oral (via a capsule). Designing an oral nanoparticle is challenging due to the harsh gastrointestinal (GI) conditions and absorption barriers. Our system includes features to address several challenges:

The risedronate-loaded PLGA NP will be encapsulated in an enteric-coated capsule or formulated with protective excipients so that it can pass through the stomach without dissolving. In the small intestine, the capsule will open to release the nanoparticles.

The pH-responsive polymer coat and PEG will protect the NP from immediate degradation in the stomach’s acidic pH and from enzymatic attack or aggregation in the intestine. As noted, chitosan or polyhistidine coatings are stable at neutral pH, so during the brief exposure in the highly acidic stomach (pH ~1–2), the NP might face some risk of premature release if polyhistidine were exposed (since at pH 2, polyhistidine would be fully protonated and potentially swollen). To mitigate this, we rely on the capsule to delay release until the intestine (pH ~6–7). Once in the intestine, the environment is closer to neutral, in which our polymer coat will remain intact.

Nanoparticles in the 100–200 nm range can be taken up across the intestinal epithelium via mechanisms such as M-cell transcytosis in Peyer’s patches or paracellular transport (especially if the NP can transiently open tight junctions). Notably, chitosan is known to have mucoadhesive properties and can transiently loosen tight junctions, potentially enhancing transport of nanoparticles across the gut lining. If we use a chitosan-based coat, it could aid in the uptake of the NP into systemic circulation by interacting with the mucosal surface. PEGylation, while reducing protein adsorption, might reduce mucoadhesion, so there is a balance to consider. We anticipate that a fraction of the orally administered NPs will be absorbed intact into the bloodstream, as has been observed in some studies of oral nanoparticles for peptide drugs. Once in circulation, those NPs will then home to bone as designed. Any NP that are not absorbed will likely be excreted in feces, and any risedronate that might leak in the GI tract could still potentially bind to bone surfaces in the gut (e.g., dietary calcium) and be lost. Therefore, maximizing NP stability and uptake is key to improving bioavailability.

In summary, our nanoparticle design incorporates multi-functionality to tackle the specific challenges of osteoporosis therapy:

- -

Dual targeting: On bone surfaces in general (via a mineral-binding ligand) and osteoclast-rich lesions (via a cell-targeting ligand).

- -

pH Triggered Release: For timing drug release at the right situation – when the nanoparticle senses the acidic conditions indicative of active bone resorption, it will release risedronate, ensuring the drug acts primarily at the site of disease.

- -

Biocompatible, Oral Formulation: Using PLGA, PEG, and chitosan/polyhistidine yields a fully biocompatible NP. These materials are non-toxic and biodegradable; PLGA breaks down into lactic and glycolic acid (natural metabolites), PEG and chitosan are generally safe in the amounts used. By formulating as an oral dosage form, we aim to improve patient compliance (avoiding injections and possibly reducing dosing frequency).

- -

Stability: PEGylation and careful surface engineering allows the NP to navigate the body’s defenses (stomach acid, digestive enzymes, immune recognition) to reach the target.

2. Synthesis and Formulation Methods

We will synthesize the dual-targeted, pH-responsive risedronate nanoparticles using a multi-step process. The process includes: (1) preparation of the risedronate-loaded PLGA core, (2) surface conjugation of the two targeting ligands, and (3) coating of the particle with the pH-sensitive polymer (with PEG incorporation). Each step will be optimized and verified by appropriate characterization techniques [7,8,9,10]. Below we describe the methods in detail.

2.1. Materials

We will source the following key materials:

PLGA polymer: We will use carboxy-terminated PLGA (e.g., 50:50 lactic: glycolic ratio, MW ~30–50 kDa) to facilitate surface conjugation chemistry (the carboxyl end-groups on PLGA will allow ligand attachment via carbodiimide coupling).

Risedronate: in the form of risedronate sodium salt (a water-soluble form of the drug).

Targeting ligands: For bone mineral targeting, we will use alendronate (another bisphosphonate) functionalized with an amine (or a similar hydroxyapatite-binding molecule with a functional handle). Alendronate has a free amine in its structure which can be used for conjugation. For osteoclast targeting, we will synthesize or purchase a RANK-binding peptide with a terminal amine or carboxyl for coupling (the exact sequence will be determined based on literature for optimal binding to osteoclasts or RANKL; we will ensure it is a relatively small peptide for stability).

pH-responsive polymer: Poly(L-histidine) (polymer of ~5–15 kDa) will be used initially. We will also obtain chitosan (MW ~50–100 kDa, deacetylation >85%) for comparison or if needed. Low molecular weight PEG-NHS (e.g., NHS-PEG5000) or PLGA-PEG-COOH will be used for PEGylation.

Chemicals for NP formulation: Dichloromethane (DCM) or ethyl acetate as organic solvent, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) as an emulsifier/stabilizer for nanoparticle synthesis, and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and N-hydroxy succinimide (NHS) for coupling reactions.

2.2. Preparation of Risedronate-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles

We will encapsulate risedronate into PLGA nanoparticles using a modified double emulsion (water-in-oil-in-water) solvent evaporation method, suitable for loading hydrophilic drugs:

Step 2.1: First Emulsion (W/O): Risedronate (which is water-soluble) will be dissolved in an aqueous phase (inner water phase) at a suitable concentration. Because risedronate carries charge, we may include a counterion or adjust pH to enhance its entrapment (e.g., loading it in its acid form to reduce solubility). This inner water phase (containing risedronate) will then be emulsified into an organic phase consisting of PLGA dissolved in dichloromethane (or ethyl acetate). We will sonicate or homogenize this mixture to create a fine dispersion of aqueous droplets (with risedronate) within the PLGA solution – these form the first water-in-oil emulsion. The PLGA in the organic solvent begins to encapsulate the aqueous droplets.

Step 2.2: Second Emulsion (W/O/W): The first emulsion is then immediately poured into a larger volume of aqueous solution containing a stabilizer (e.g., 1–2% PVA solution). Vigorous mixing or sonication is applied to create a second emulsion, dispersing the PLGA-containing organic droplets into the outer water phase. This yields a water-in-oil-in-water double emulsion, where the innermost water droplets (with drug) are inside PLGA/solvent droplets, which are in water.

Step 2.3: Solvent Evaporation and NP Hardening: The double emulsion is stirred to allow the organic solvent to evaporate. As the solvent evaporates, the PLGA precipitates and forms solid nanoparticles entrapping risedronate in their core. We will perform this step under moderate stirring and possibly reduced pressure (or a rotavapor) to remove the solvent efficiently.

Step 2.4: Purification: The resulting nanoparticles will be washed and collected by repeated centrifugation and resuspension in water (or by ultrafiltration). This removes residual PVA, free (unencapsulated) risedronate, and other impurities. We expect an encapsulation efficiency in the range of ~70–80% based on prior literature for bisphosphonate loadingfile-kur39vzxzfdjsz6575ckec, which we will measure later. The NP pellet is then resuspended in deionized water (or buffer) for the next steps. At this stage, the nanoparticles are plain PLGA particles loaded with drug, with carboxyl groups on their surface (from PLGA end groups).

Size Tuning: We will adjust the sonication power and stabilizer concentration to achieve the desired size (target ~100–150 nm diameter). A higher homogenization speed and higher PVA usually yield smaller particles. We will measure the size distribution by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and aim for a monodisperse population. If needed, we will filter the suspension through a 0.2 µm filter to remove any large aggregates.

2.3. Conjugation of Targeting Ligands to NP Surface

With the PLGA nanoparticles formed, the next step is to attach the two targeting ligands (bone-targeting and osteoclast-targeting) to their surfaces. We will use carbodiimide chemistry (EDC/NHS coupling) to attach ligand molecules that have amine groups to the carboxyl groups on the NP surfacefile-kur39vzxzfdjsz6575ckec:

Step 3.1: Activation of NP Surface Carboxyls: The nanoparticle suspension will be adjusted to pH ~6.0 (appropriate for EDC coupling) and mixed with EDC and NHS. EDC will react with surface carboxyl groups to form an active O-acylisourea intermediate, which is then stabilized by NHS to form an NHS-ester on the NP surface.

Step 3.2: Addition of Ligands: We will then add our ligands. First, we will attach the bone-binding ligand (e.g., alendronate). Alendronate has a primary amine that can attack the NHS-ester, forming a stable amide bond linking the alendronate to the PLGA surface. We will use an excess of alendronate relative to available carboxyls to drive the reaction. The reaction will be allowed to proceed for a couple of hours at room temperature with gentle stirring. After this, we will quench any remaining active esters (for example, by adding ethanolamine).

Step 3.3: Attachment of Osteoclast-Targeting Peptide: The second ligand (RANKL-mimetic peptide) will be conjugated similarly. One strategy is sequential coupling: after attaching the first ligand and purifying the particles, we can re-activate remaining carboxyl groups (or, if the peptide has a carboxyl end, use EDC to link it to an amine on the surface or possibly to a diamine linker attached prior). For simplicity, assume the peptide has an N-terminal amine. We would repeat the EDC/NHS activation on the partially conjugated particles and then add the peptide to bind to remaining sites. If the first ligand did not consume all carboxyls, this works. Alternatively, we could co-conjugate both ligands in one step by adding both molecules simultaneously during coupling but controlling the ratio and ensuring both attach could be challenging. We will likely do it sequentially, attaching the smaller ligand (alendronate) first and the peptide second, as the larger peptide might be more sensitive to reaction conditions.

Step 3.4: Purification: After conjugation, nanoparticles will be washed (via centrifugation or dialysis) to remove any unbound ligand and coupling reagents. We will collect the dual-ligand functionalized nanoparticles.

Ligand Density and Verification

For alendronate (or bisphosphonate) on the surface, we may use a colorimetric assay for phosphate or a fluorescently labeled analog to estimate how much attached. Also, zeta potential measurements can indirectly indicate surface modification: PLGA NPs are initially negatively charged; after adding positively charged alendronate (which has amines, though also phosphonate groups), the zeta potential might become slightly less negative.

For the peptide, if it contains certain amino acids, an assay like bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay could estimate surface peptide amount. Alternatively, we could incorporate a small amount of FITC-labeled peptide and use fluorescence to quantify binding. We will also perform functional assays (later) to verify that the ligands are active (e.g., binding to hydroxyapatite for the bone ligand, and binding to target cells for the osteoclast ligand).

2.4. pH-Responsive Polymer Coating

Finally, we will apply the pH-sensitive polymer coating (and PEG) to the ligand-functionalized nanoparticles[11,12]. We have two approaches depending on the polymer choice:

2.4.1. Poly(L-histidine) Grafting:

Polyhistidine can be attached to the surface via amide bonding as well. We can obtain polyhistidine with a terminal amine (or carboxyl). For instance, if we have PLGA-COOH still available or if we incorporated a bifunctional linker, we could use EDC/NHS again to attach polyhistidine chains to the surface. Each polyhistidine chain would then be tethered to the NP at one end, forming a “brush” that covers the particle. We might do this after ligand attachment; however, too many polyhistidine chains might sterically hinder the targeting ligands. An alternative is to first mix the NP with polyhistidine such that it adsorbs electrostatically. Since at neutral pH, polyhistidine is mostly uncharged (some fraction might be protonated), the electrostatic attraction to PLGA (which is negatively charged) might be weak. We could perform this at slightly acidic pH (around pH 6.5) where polyhistidine carries some positive charge, to get it to adsorb onto the NP surface. Then the pH could be raised to neutral, at which the polyhistidine might collapse onto the surface and remain associated (due to hydrophobic interactions). To secure it, we might still crosslink a fraction of it via EDC to any remaining carboxyls, if available.

We will also incorporate PEG [13] during this step. One strategy is to co-graft some PEG chains along with polyhistidine using appropriate chemistry (for example, mixing NHS-PEG in with the polyhistidine coupling reaction so both attach to different sites). Another strategy is to use a block copolymer like PEG-polyhistidine, if available, to coat the surface directly. However, synthesizing PEG-polyhistidine might be non-trivial for this project. Therefore, we lean towards sequentially attaching PEG after the polyhistidine coat is on (the polyhistidine itself has imidazole groups that might be used to attach PEG if functionalized).

The outcome of this sub-step is a nanoparticle where polyhistidine chains cover the surface, interspersed with PEG chains. The targeting ligands should ideally protrude through or be accessible despite the coating. We will optimize so that the density of polymer is enough for drug retention but not so dense as to completely bury the ligands. This may involve testing different polymer:NP ratios.

2.4.2. Chitosan Coating

If using chitosan, a simpler adsorption method can be employed. Chitosan is positively charged and can spontaneously coat negatively charged nanoparticles. We will dissolve chitosan in a mild acidic solution (e.g., acetic acid, pH ~5.5) to make it soluble. Then we will add the NP suspension to the chitosan solution under stirring. The positively charged chitosan chains will bind to the negatively charged NP surfaces, forming a polyelectrolyte coating. Next, we will raise the pH to ~7 by dialysis or gradual neutralization. At neutral pH, chitosan becomes insoluble and will precipitate onto the NP surface as a stable film.

Chitosan can entrap the surface-bound ligands; however, because our ligands are covalently attached, they should still be there beneath the chitosan. We will ensure the chitosan layer is not too thick – controlling the concentration and time will help. After coating, we can also attach PEG. For example, chitosan has amino groups that could react with NHS-PEG to graft some PEG onto the chitosan layer. We might do a reaction with NHS-PEG on the chitosan-coated NPs to introduce PEG, thereby yielding a chitosan-PEG hybrid layer.

The advantage of chitosan coating is its simplicity and known behavior in GI conditions (mucoadhesion and opening tight junctions). The disadvantage is it introduces a positive surface charge (which could cause aggregation or rapid clearance if too high). PEGylation will help neutralize that charge and provide stealth.

We will experiment with both polyhistidine and chitosan coatings in the initial phase and characterize their performance (particularly pH-triggered release behavior) to decide which to carry forward in in-depth biological testing.

2.5. Characterization of Nanoparticle Properties

After full assembly of the nanoparticles (drug loaded, dual-ligand functionalized, pH-sensitive coated), comprehensive characterization [11,12,13,14,15] will be performed:

Particle Size and Morphology: Using dynamic light scattering (DLS), we will measure the hydrodynamic diameter and polydispersity index of the final nanoparticles. We expect a slight size increase after polymer coating compared to the bare PLGA NP. For visual confirmation, transmission electron microscopy (TEM) will be used to observe particle shape and core-shell structure (staining may be needed to see the polymer coating).

Surface Charge (Zeta Potential): We will measure zeta potential at each stage of modification to track changes: plain PLGA NPs (likely highly negative due to carboxylate), after ligand conjugation (perhaps slightly less negative if neutral or positively charged ligands attach), and after polymer/PEG coating (which could make it near-neutral or slightly positive if chitosan is used). A successful chitosan coat would show a zeta shift to positive values, whereas a PEG coating tends to neutralize charge.

Drug Loading and Encapsulation Efficiency: We will determine the risedronate loading by digesting a known amount of nanoparticles in an alkaline solution or organic solvent to release the drug, and then measuring risedronate content. Risedronate can be quantified by UV-Vis spectroscopy (after a color reaction such as complexation with Fe(III) which bisphosphonates can do) or by HPLC (with a UV detector, using an ion-pair or gradient method since risedronate is polar). We will calculate encapsulation efficiency = (mass of risedronate in NPs / mass initially added) × 100%, and drug loading capacity = (mass of drug in NPs / mass of total NPs) × 100%. We aim for high loading efficiency (~80%) so that the NP can deliver therapeutic doses.

pH-Responsive Behavior: To verify the stimulus-responsive design, we will conduct in vitro release studies at different pH. Nanoparticles will be suspended in buffer at pH 7.4 (physiological) and pH 6.5 (representing osteoclast milieu) and pH ~5 (endosomal). At set time intervals, samples will be taken and filtered or centrifuged to separate released drug from NP, and the drug in solution will be measured. We expect minimal release at pH 7.4 in early time points, but significantly higher release at pH 6.5 or 5. For example, over 24 hours, <20% release at pH 7.4 but >50% at pH 6.5 would indicate good pH sensitivity. These studies will confirm that the polymer coating effectively retains the drug at neutral pH and dissolves or opens at acidic pH. If using chitosan, we anticipate that at pH 6.5 it starts to solubilize and let drug out, whereas at 7.4 it stays intact.

Simulated GI Stability: Although more relevant to in vitro testing, we will also verify NP stability in simulated gastrointestinal fluids. In simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH ~1.2) without enzymes, incubate NPs for 2 hours and assess if significant drug is released or if particles degrade (we can measure size changes or drug release). We expect that with the protective measures (capsule + coatings), the NP should remain mostly intact (if tested without capsule, this is a worst-case scenario). Then in simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH ~6.8) for another few hours, see if NPs start releasing drug – we expect only minor release in SIF (since pH 6.8 is still near neutral and should not trigger full release). These tests, along with a Caco-2 cell permeability test (described later), will inform us about how the formulation behaves upon oral administration.

Ligand Accessibility Tests: To ensure that our targeting ligands are still functional after all modifications, we will carry out two quick in vitro binding assays:

Hydroxyapatite Binding Assay: Mix the nanoparticles with hydroxyapatite powder or crystals in buffer, then centrifuge and measure how many NPs remain free in solution vs bound to the HA (for instance, measure the drug or an NP-associated fluorescence in supernatant). We expect the bone-targeting ligand (bisphosphonate) coated NPs to bind strongly to HA, much more than control NPs without that ligand. This will confirm bone affinity.

Cellular Binding Assay: We will expose the nanoparticles to a culture of osteoclast-like cells (RAW264.7 cells differentiated with RANKL, or primary osteoclasts) and examine binding/uptake (this is detailed in In Vitro Testing, but initial qualitative tests can be done here too). For example, fluorescently label the NPs (by encapsulating a fluorescent dye or tagging the surface) and observe under a microscope whether they attach to osteoclasts more than to a control cell (like osteoblasts or undifferentiated cells). Enhanced binding to osteoclasts would indicate the osteoclast-targeting ligand is functioning.

Data Confirmation

All characterization data will be compiled to confirm that we have successfully created a nanoparticle with the intended properties: appropriate size, high drug loading, dual ligand presence, stability in neutral pH, and responsiveness to acidic pH. Once the formulation is validated, we will proceed to biological evaluations. In the next section, we outline the testing protocols for assessing the efficacy and safety of this nanoparticle system in vitro and in vivo.

3. Testing Plan

To demonstrate the potential of the dual-targeted, stimuli-responsive nanoparticle system, we will undertake a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. These experiments are designed to test the nanoparticle’s performance in terms of targeted drug delivery, pharmacokinetics, therapeutic efficacy against osteoporosis, and safety. We will also compare the performance of our specialized NP to appropriate controls (such as free drug and simpler nanoparticle variants) to quantify the benefits of each design feature.

3.1. In Vitro Testing

Our in vitro testing strategy will address several aspects: drug release behavior, cell targeting and uptake, and biological activity (anti-resorptive effect) in cell cultures. Unless otherwise specified, all in vitro studies will be conducted at least in triplicate for statistical reliability.

pH-Triggered Drug Release Study: Although we will have characterized release in buffer, we will repeat or extend these studies to confirm the controlled release profile. Using dialysis or a diffusion chamber, we will measure cumulative risedronate release from the nanoparticles over time at pH 7.4 vs pH 6.5. If we simulate conditions more closely, pH 6.5 plus the presence of hydroxyapatite (to mimic bone surface binding) could be used to see if binding affects release (could possibly slow release by sequestering NPs, but once they release drug, the drug may bind HA). We expect minimal drug release at pH 7.4 (<~20% in 24h) and significantly higher release at pH 6.5 (~50% or more in 24h, and nearly complete release over several days). This experiment will visually demonstrate the stimuli-responsive nature of the system (we can plot release curves).

Nanoparticle Stability in Simulated GI Fluids: We will subject the nanoparticles to sequential incubation in SGF and SIF, mimicking oral administration conditions. After SGF (pH1.2, 2h) exposure, we will examine the NP under DLS for size changes and measure any drug released into the fluid. We anticipate that the enteric capsule would normally prevent direct SGF contact, but this test stresses the formulation’s inherent stability. We expect little drug release in SGF (since the NP are protected by coatings), though some surface polymer might protonate. Next, transferring to SIF (pH6.8, with bile salts/enzymes if we include them) for 4h, we will again measure if any premature drug release occurs. Ideally, the majority of drug remains encapsulated through this GI transit simulation, indicating the NP can reach the absorption site intact.

Caco-2 Cell Permeability Assay (Intestinal Absorption Model): To evaluate the potential of the nanoparticles to be absorbed through the intestinal epithelium, we will perform a transport study using a Caco-2 cell monolayer (a well-established in vitro model of the human intestinal barrier). Nanoparticles (with risedronate or possibly a tracer) will be added to the apical side of a Transwell chamber where Caco-2 cells are cultured to confluence (forming tight junctions). We will measure the amount of drug (or nanoparticle-associated marker) that appears in the basolateral chamber over time. We will compare free risedronate solution (which is poorly permeable), and Risedronate-loaded nanoparticles.

It would also be suitable to compare chitosan-coated vs uncoated NP to see effect of mucoadhesive polymer. If chitosan is used, we expect an increased permeability due to the transient opening of tight junctions. Overall, we hypothesize that a detectable fraction of risedronate will traverse the monolayer when delivered via nanoparticles, whereas free risedronate shows negligible transport (reflecting its low bioavailability in vivo). This experiment will give a qualitative measure of improved absorption. We will also check the integrity of the monolayer (transepithelial electrical resistance, TEER, measurements) to ensure that NP do not cause damage; a temporary slight drop in TEER with chitosan NP is expected (indicating reversible opening of junctions).

Osteoclast Cell Targeting and Uptake: Next, we will test whether the dual-targeting ligands indeed enhance association of NPs with osteoclasts in vitro. We will generate osteoclast-like cells by differentiating RAW 264.7 monocyte cells with RANKL (or using primary bone marrow macrophages with M-CSF/RANKL). These osteoclasts (which form multinucleated cells that resorb bone in vitro) will be incubated with our nanoparticles (for visualization, we will use NPs encapsulating a fluorescent dye or tagged with a fluorescent label). As controls, we will use:

Nanoparticles lacking the osteoclast-targeting ligand (only bone-targeted).

Nanoparticles lacking both targeting ligands (plain NP, possibly with just PEG).

Possibly free drug (though that won’t “stick” to cells unless it goes inside). After incubation (e.g., 1–2 hours), we will wash the cells and examine them by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. We expect to see significantly higher fluorescence in osteoclasts treated with dual-targeted NPs compared to controls, indicating greater binding/uptake due to the RANKL-peptide. Confocal microscopy can visualize nanoparticles at or inside the osteoclasts. Additionally, we can use a co-culture or sequential test with osteoblasts or other cells to ensure specificity: for instance, treat osteoblast-like cells (MC3T3) with the same NPs and see much lower binding, indicating the osteoclast-specific ligand is doing its job.

In Vitro Bone Binding (Mineral Affinity) Test: We will also assess the bone-mineral targeting function in a cellular context. A simple approach is to use mineralized tissue culture plates or bone slices. For example, hydroxyapatite-coated wells or actual bovine bone slices can be placed in culture, and nanoparticles are added. After incubation, rinse off unbound NPs and measure the amount of NP that remain bound to the mineral/bone surface (either by drug content or fluorescence). The bisphosphonate-bearing NPs should exhibit strong binding, whereas NPs without that ligand will wash away. This will reinforce the outcome of the earlier HA binding assay under more realistic conditions.

Anti-Resorptive Efficacy in Osteoclast Cultures: To confirm that the delivered risedronate remains pharmacologically active and that targeted delivery improves efficacy, we will perform functional assays on osteoclast activity:

Osteoclast Resorption Pit Assay: We will culture osteoclasts on a thin layer of calcium phosphate or dentine discs. When osteoclasts resorb bone, they leave pits or release calcium. We will treat the cultures with either: (a) free risedronate (at various concentrations), (b) risedronate-loaded dual-targeted NPs (with equivalent risedronate dose), (c) non-targeted NPs with risedronate, and (d) no drug (control). After 48–72 hours, we will assess resorptive activity by staining the calcium pits or measuring calcium in the medium. We anticipate that groups (a) and (b) will inhibit resorption compared to control, but importantly, group (b) might achieve similar inhibition at a lower apparent concentration due to better uptake by osteoclasts. Also, if washout steps are done (to remove non-bound drug after a short exposure), the targeted NP that bind to cells might remain associated and keep releasing drug to the osteoclast, leading to a stronger effect than free drug which gets washed away. This mimics how targeting can enhance local drug retention.

Osteoclast Viability/Apoptosis: Bisphosphonates like risedronate cause osteoclast apoptosis by disrupting their mevalonate pathway. We will use a TRAP (tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase) staining to identify osteoclasts and observe their number and morphology after treatment. We expect fewer and smaller TRAP-positive multinucleated cells in wells treated with risedronate (especially with targeted NP) versus control. We can quantify osteoclast numbers and nuclei count per osteoclast. Additionally, an apoptosis assay (like TUNEL or caspase activity) in osteoclast cultures could show higher apoptosis in NP-treated groups, indicating the drug has been effectively delivered intracellularly.

Cytotoxicity to Off-Target Cells: We will also evaluate if the nanoparticle by itself is toxic to other cell types, as a safety check. For example, do an MTT or alamarBlue assay on a bone-forming cell line (osteoblasts) or general fibroblasts with exposure to the nanoparticles (with and without drug). We expect PLGA/PEG NPs to be non-cytotoxic. Risedronate, if not delivered inside osteoclasts, has minimal effect on other cells (it acts mainly when internalized by osteoclasts). This selectivity might be improved with our system: free risedronate in medium could enter any cell a bit and might affect them, whereas NP-encapsulated risedronate won’t enter cells that don’t trigger its release. So we might see that free risedronate at high concentration could mildly affect osteoblast viability, while NP risedronate has negligible effect on osteoblasts (since presumably it doesn’t release in their neutral pH environment). This would support the notion of reduced off-target toxicity.

Summary, Anticipated Outcomes

To summarize, the in vitro experiments will demonstrate that the nanoparticle remains intact in normal conditions and releases drug in response to acidity. It will also confirma survival of the NP’s in GI-like conditions and relative absorption, allowing us to remark on its bioavailability being improved or diminished. It preferentially must be show to bind to bone mineral and osteoclasts to show our intended dual targeting worked. Finally, that it effectively delivers the drug to osteoclasts, inhibiting their bone resorption activity more efficiently than non-targeted approaches, without compromising biocompatibility of non-targeted cells.

If any aspect underperforms (for example, if targeted binding is not strong enough), we may adjust the ligand densities or polymer composition and re-test. However, assuming positive results, we will advance to in vivo studies to test the system in an animal model of osteoporosis.

3.2. In Vivo Testing

For in vivo evaluation, we will use an animal model that closely mimics human osteoporosis – the ovariectomized (OVX) rodent model, which is a standard for postmenopausal osteoporosis. The goal of in vivo testing is to confirm that our nanoparticle can increase the delivery of risedronate to bones (especially osteoporotic bones) when given orally, and consequently improve bone outcomes more than the free drug, without causing undue side effects.

3.2.1. Animal Model

Figure 2.

Sprague-Dawley rats are used in biomedical research due to their genetic diversity, ease of handling, and physiological similarities to humans.

Figure 2.

Sprague-Dawley rats are used in biomedical research due to their genetic diversity, ease of handling, and physiological similarities to humans.

We will use adult female Sprague-Dawley rats (approximately 3 months old at start). One group of rats will undergo bilateral ovariectomy (surgical removal of ovaries) to induce estrogen-deficiency osteoporosis. OVX leads to bone loss (especially in trabecular bone of the femur and spine) over subsequent weeks. A sham-operated group (surgery without ovary removal) will serve as a baseline control for healthy bone parameters. We will allow 6–8 weeks post-OVX for osteoporosis to develop (significant bone loss). Then we will initiate treatment.

- -

Treatment Groups: Rats will be randomly divided (with ~8–10 rats per group for statistical power) into the following treatment groups:

- -

Healthy control (sham + no treatment): to represent normal bone (not osteoporotic, no therapy).

- -

OVX control (OVX + no treatment): osteoporotic, untreated, to measure the extent of bone loss and serve as a negative control for therapy.

- -

Free Risedronate (OVX + free drug): osteoporotic rats treated with oral risedronate solution (or suspension) at a dose equivalent to a typical clinical dose scaled to rat size (for example, ~5 mg/kg/week, as a single weekly oral gavage).

- -

Dual-Targeted pH-Responsive NP (OVX + targeted NP): osteoporotic rats treated with the oral nanoparticle formulation, containing the same equivalent dose of risedronate (5 mg/kg/week) in an enteric capsule or appropriate vehicle.

- -

Nanoparticle control (OVX + blank NP): (optional) to isolate effects of the NP itself, a group receiving the same NP but without risedronate. This checks biocompatibility, but if animals are limited, we may omit this since PLGA NPs are known to be safe; however, including it is good for interpretation of any effects.

Additionally, to demonstrate the importance of dual targeting and pH-responsiveness, we could include exploratory groups such as:

NP with only bone-targeting ligand (no osteoclast ligand, but still pH-responsive)

NP with dual targeting but non-pH-responsive (for example, without the pH coat, to see if uncontrolled release is less effective or more toxic)

These would help attribute the outcomes to each feature. However, adding too many groups increases the complexity. The core comparison is free drug vs. our full-feature NP.

Dosing Regimen: We choose a once-weekly oral dose for both free risedronate and NP groups, mirroring how bisphosphonates are given to humans weekly. Each dose for NP will be given via oral gavage of a capsule or suspension in buffer. We will treat for a total of 8 weeks. This duration should be enough to observe differences in bone density, as risedronate typically shows BMD improvements in rats within weeks.

3.2.2. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution Sub-Study

On the first dose, we will perform a pharmacokinetic analysis in a subset of animals (or additional rats if possible). We will sample blood at various time points after administration (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48 hours) to measure risedronate plasma concentration. We expect free risedronate to show a low plasma level (due to poor absorption), whereas the NP group may show a different profile (possibly a delayed peak due to absorption and controlled release, but potentially higher AUC if absorption is improved). We will also sacrifice a few animals at certain time points to directly measure drug distribution: collect organs (femur, spine, liver, kidneys, etc.) and quantitatively determine how much risedronate is in bone versus other organs. Risedronate in bone can be measured by dissolving bone in acid and doing an assay or using radiolabeled drug to track (we might use a trace of tritium-labeled risedronate for this purpose). We expect that bone uptake of risedronate will be higher in the NP group compared to free drug, indicating better targeting. We also expect lower kidney exposure in NP vs free, since free bisphosphonate tends to be cleared via kidneys quickly, whereas NP should sequester drug away from direct renal filtration. This sub-study will give early evidence of targeting: e.g., at 24h, what percentage of dose is in bone for NP vs free? Ideally, NP delivers more to bone.

3.2.3. Bone Density and Microarchitecture Outcomes

We will perform Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) or quantitative micro-CT scans of the rats’ bones (e.g., femur and lumbar spine) before treatment (baseline, after OVX) and after the 8-week treatment. OVX control group will show a decline in bone mineral density (BMD), whereas the treated groups (free risedronate and NP) should show maintenance or increase in BMD. We hypothesize that the NP-treated group will have a greater BMD improvement than the free drug group at the same dose, due to better targeting efficiency.

High-resolution micro-CT analysis of trabecular bone (in distal femur or vertebrae) will be done at the endpoint. Key parameters such as trabecular bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number and thickness, and cortical thickness will be measured. We expect OVX to cause low BV/TV, which free risedronate will partially restore, and NP risedronate to restore further. For example, if OVX reduces BV/TV to 50% of normal, free drug might bring it to 70%, whereas NP could bring to 80–90% of normal due to targeted action.

Bone strength testing: We will conduct mechanical testing on excised bones to see if improvements in density translate to stronger bones. Three-point bending tests on femurs and compression tests on vertebrae can determine maximum load to fracture. We expect NP-treated bones to withstand higher loads than both OVX and free-drug treated bones (or at least higher than OVX untreated).

3.2.4. Biochemical Markers of Bone Turnover

A marker of bone resorption like CTX (C-terminal telopeptide of type I collagen), which is elevated in OVX rats, should decrease with effective anti-resorptive treatment. We will measure CTX levels at baseline, mid-point, and end. The NP group may show a larger decrease in CTX than free risedronate.

A bone formation marker like P1NP (pro-collagen type I N-terminal propeptide) or osteocalcin might initially drop with anti-resorptive (coupling effect), but towards end could reflect improved remodeling balance. Monitoring these gives insight into how specifically the treatment is affecting bone turnover dynamics. Perhaps a highly targeted resorption inhibitor might not suppress bone formation as much as a systemic one (this is speculative but interesting: if we only hit the high resorption sites, maybe basic formation elsewhere continues).

3.2.5. Histological Analysis

TRAP staining for osteoclasts on bone surfaces can show if treated groups have fewer active osteoclasts. We expect NP treated bones to have significantly fewer TRAP-positive osteoclasts per bone surface area than OVX controls, likely even fewer than free risedronate if it’s more effective locally.

Osteoblasts and new bone formation can be assessed by double-calcein labeling (if we give two fluorescent calcium-binding labels during the study, to measure bone formation rate) or by alkaline phosphatase staining. This might show if bone formation is preserved. General histology can check for any abnormal bone quality or architecture issues (like microcracks, though 8 weeks is likely too short for that).

3.2.6. Specificity to Lesions

If possible, we may create a scenario to observe that healthy bones are less affected. Because osteoporosis is diffuse, one approach is to look at different skeletal sites: e.g., the lumbar vertebrae (which lose a lot of trabecular bone after OVX) versus the mid-shaft cortical bone (less affected by OVX). We hypothesize the nanoparticle might show especially strong effects in high-turnover trabecular bone (lesion-like) and comparatively less action on cortical bone (which might be beneficial as cortical doesn’t need as much suppression). Free risedronate would more uniformly affect both. If our data show that cortical bone remodeling in NP group is closer to normal than in free drug group, it suggests we spared some normal bone remodeling while treating the high-turnover sites – a desirable outcome to reduce long-term side effects.

3.2.7. Safety and Off-Target Effects

Body weight and clinical signs: OVX rats tend to gain weight; treatments should not cause unusual weight loss or illness. We will observe feeding behavior, fur condition, etc.

Serum chemistry: Particularly kidney and liver function tests (BUN, creatinine, AST/ALT). Bisphosphonates at high doses can stress kidneys; if our NP reduces kidney exposure, those values might be normal. We anticipate no systemic toxicity from PLGA/PEG. If any group shows elevated kidney markers, that would likely be the free drug group rather than NP.

Necropsy and tissue analysis: After sacrifice, we will examine major organs (liver, kidney, spleen, GI tract). We will histologically look for any signs of inflammation or damage. Since bisphosphonates can cause GI irritation if they directly contact mucosa, we’ll check the esophagus/stomach of free drug group for any lesions. The NP group might show less GI irritation because the drug is encapsulated and not in direct contact.

Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) risk: In rodents, ONJ-like lesions are not common unless high doses and dental extractions are done. We will inspect the jaw bones for any necrotic areas or impaired healing if any teeth lost. We do not expect any ONJ in this short study, but if theoretically free drug had any effect on jaw, a targeted NP might have less because it doesn’t release drug in healthy jawbone (no acidic resorption unless there’s a tooth extraction site).

Immune reactions: Unlikely with PLGA/PEG, but we will check for any signs of injection-site or GI immune response (since it’s oral, maybe none, but ensure no severe inflammatory response in gut to NPs).

3.2.8. Data Analysis

We will compare outcomes across groups: BMD, micro CT metrics, mechanical strength, etc., using ANOVA with post-hoc tests to see significant differences. We expect: OVX vs sham (significant bone loss), treatment vs OVX control (significant improvement), NP vs free (NP superior).

We will also calculate an “effective dose” comparison. If our NP is more efficient, a lower dose might achieve the same effect as a higher dose of free drug. We could include a lower-dose NP group to see if it matches full-dose free drug outcomes, demonstrating dose-sparing. For instance, NP at 1/2 the dose might achieve similar BMD as full dose free drug. That would show an advantage in terms of reducing drug exposure.

If we included a single-target NP group, we would compare that too: maybe dual-target NP shows better results than bone-target-only NP or osteoclast-target-only NP, highlighting synergy.

3.2.9. Summary, Anticipated Outcomes

The in vivo study is expected to provide proof-of-concept that orally administered dual-targeted NPs substantially improve risedronate delivery to bones (higher bone drug levels, higher BMD gains) compared to orally administered free risedronate.

The NP treatment mitigates bone loss in OVX rats more effectively, leading to stronger bones. Side effects or off-target effects are reduced: for example, no signs of GI irritation in NP group vs potential mild issues in free drug group; normal kidney function in NP group, etc.

The concept of pH-selective release is indirectly supported if we see that normal bone (where pH is normal) is not overly suppressed (meaning maybe bone formation continues or there’s no excess accumulation of microdamage).

The dual targeting should show benefit: if included rats with dual-target NP might have better outcomes than those with only one targeting mechanism (this would underscore that both bone affinity and osteoclast targeting together yield best result).

In summary, the in vivo tests will demonstrate the therapeutic efficacy and safety of our nanoparticle system in a living organism. A successful outcome would be seeing near normalization of bone density in osteoporotic animals treated with the NP, without the typical side effects of bisphosphonates, achieved through a convenient oral delivery method.

4. Discussion

The proposed dual-targeted, stimuli-responsive nanoparticle system is an innovative approach to address key challenges in osteoporosis treatment. By integrating multiple targeting strategies and controlled release, it exemplifies a precision medicine paradigm for delivering drugs to where they are needed most. Here we discuss the anticipated benefits of our system, its potential impact, and considerations for future development.

Advantages of the Dual-Targeted, pH-Responsive NP:

Improved Drug Delivery and Efficacy: Our system is designed to significantly enhance the delivery of risedronate to bone lesions. By combining bone mineral affinity and osteoclast-specific binding, we ensure that the nanoparticles accumulate at sites of active bone resorption in much higher concentration than in normal bone. The pH-responsive release then triggers a high local dose of risedronate exactly where osteoclasts are active, maximizing its anti-resorptive effect. We expect this will translate to greater inhibition of bone resorption and better preservation (or increase) of bone density compared to conventional therapy. In effect, more of the administered drug reaches and acts on the target cells (osteoclasts) rather than being wasted or causing off-target effects. This could mean that a lower total dose of risedronate achieves the same (or better) therapeutic outcome, addressing efficacy and safety simultaneously.

Enhanced Oral Bioavailability: By encapsulating risedronate in a nanoparticle that can survive the GI tract and facilitate uptake, we tackle the <1% oral bioavailability problem. Even if a modest percentage of nanoparticles are absorbed through the intestines, that could represent a several-fold increase in the amount of drug entering systemic circulation compared to a free drug dose. The use of absorption-enhancing components like chitosan further improves this prospect. An increase in bioavailability means that patients get more benefit from each oral dose, potentially allowing for lower dosing frequency or amount. Better bioavailability and protection by the NP also likely reduce GI side effects (since less free drug contacts the gut lining).

Precision Targeting vs. Healthy Bone Sparing: One novel aspect of our design is the attempt to discriminate diseased bone from healthy bone. Current treatments affect the entire skeleton uniformly, often leading to suppression of bone remodeling even in healthy bone (hence issues like microcrack accumulation or ONJ over long term). In our system, healthy bone that is not undergoing active resorption should attract fewer nanoparticles (due to lower RANKL/osteoclast presence), and even any NP that do bind there will not release much drug (because the microenvironment pH is normal). Thus, healthy bone might experience minimal bisphosphonate action, preserving normal remodeling in those areas. Meanwhile, high-turnover osteoporotic bone areas get the brunt of the therapy. This targeted action could reduce long-term complications. It essentially provides a site-specific therapy, an unmet need in osteoporosis where some bones (e.g., spine) are more affected than others.

Controlled Release in Acidic Microenvironment: The pH-responsive feature ensures that risedronate is released in a controlled, on-demand manner. This addresses the problem of non-specific or premature drug release seen in many conventional nanoparticle systems. For instance, in a non-pH-sensitive NP, a significant portion of drug might leach out in the bloodstream or in tissues like the liver, reducing the amount that reaches bone and possibly causing side effects elsewhere. Our design prevents most release until the NP encounters acidic conditions (like in osteoclast resorption lacuna or lysosomes after uptake). This not only increases efficacy at target but also reduces systemic exposure. The drug largely stays “locked” during transit, thus organs like kidneys (that normally filter bisphosphonates quickly) will see less free drug, potentially lowering the risk of renal stress or other side effects.

Biocompatibility and Safety: All components of our NP are biocompatible and biodegradable. PLGA and PEG have a long track record of safe use in drug delivery (PLGA nanoparticles are used in approved products, and PEG is in many IV drugs). Risedronate is a well-established drug whose systemic effects are known. By localizing it, we are not introducing a new toxic agent, just using an old one smarter. Chitosan, if used, is a natural polysaccharide often used in dietary supplements. The removal of the NP from the body should be via natural pathways: PLGA degrades to metabolic acids over weeks, risedronate that does not bind bone is excreted, and small amounts of PEG/chitosan will be cleared or metabolized. We anticipate minimal immunogenicity (PEG reduces that risk) and minimal organ toxicity, as evidenced by our planned safety evaluations. Better targeting also means fewer bisphosphonate molecules floating freely to cause things like GI or jaw issues. Overall, the system should be well-tolerated for long-term use, which is crucial since osteoporosis treatment can span years.

Patient Compliance: By making the therapy oral and potentially less frequent, patient compliance should improve. Patients prefer oral medications over injections (like denosumab). If our NP allows monthly dosing instead of weekly or eliminates the strict fasting/upright requirements (because the NP doesn’t harm the esophagus), it will be a more convenient therapy. Better compliance directly correlates with better clinical outcomes in chronic diseases. Thus, our technology could improve not only the drug’s biological performance but also its real-world effectiveness by being easier to take.

Potential Impact on Osteoporosis Management: If successful, this NP system could herald a new class of “smart” osteoporosis drugs that actively seek out bone lesions. This would be a notable improvement in how we treat the disease. It might also reduce the need for combination therapy: currently, some patients cycle between anti-resorptives and anabolics to balance effects. A precisely targeted anti-resorptive might maintain bone turnover more naturally, delaying the need for adding an anabolic agent. Furthermore, by reducing side effects, more patients might be willing to start therapy early and stay on it, which can prevent fractures in a larger population. The economic impact could be significant: fewer fractures mean reduced healthcare costs.

Potential Challenges and Considerations

While the anticipated benefits are strong, it is important to acknowledge challenges and plan for them:

Oral Absorption Efficiency: One uncertainty is how efficiently these nanoparticles can be absorbed in humans. Rodents often have more permeable guts than humans. Even if we see improved absorption in rats, translating that to human oral bioavailability will require further optimization (maybe smaller particles, different coatings, or targeting M-cells with a specific ligand like an RGD for Peyer’s patches). If oral route proves too inefficient, the system could alternatively be adapted for intravenous injection; it would still target bone and release in acidic sites, providing benefit, though it sacrifices the convenience of oral dosing. Nonetheless, our initial focus is to push the envelope on oral NP delivery.

Manufacturing and Scalability: The formulation has multiple components and steps (dual ligands, polymer coat). Scaling up such a complex nanoparticle and ensuring consistency (batch-to-batch reproducibility of ligand densities, etc.) could be challenging. In a practical scenario, one might simplify the design if needed – for example, if one ligand is overwhelmingly effective, perhaps dual is not needed, or if polyhistidine is too expensive, a simpler pH-sensitive coating (like an enteric polymer) could be substituted. Part of our research will clarify which components are most critical so that a manufacturable version can be envisioned.

Stability of Ligands in vivo: Peptides on the surface could potentially be cleaved by proteases or sheared off in circulation. We might need to stabilize them (e.g., use D-amino acids or cyclization of the peptide to avoid proteolysis). We should also ensure that the ligands remain attached during the nanoparticle’s transit from gut to bone. The covalent bonds and/or strong adsorption should help, but vigorous blood flow or enzyme exposure might gradually remove some. We may account for that by loading a surplus of ligand or using highly stable linkages.

Potential Immunogenicity of Targeting Ligands: While PLGA and PEG are inert, a peptide could trigger an immune response if recognized as foreign. We will choose peptides that are as human-like as possible (maybe derived from human RANKL sequences) and relatively short. If immunogenicity becomes an issue, one could consider using a humanized antibody fragment instead, though that complicates oral delivery (antibodies would likely not survive GI).

Effect on Bone Remodeling Balance: We aim to spare healthy bone, but it’s possible that highly efficient targeting could over-suppress resorption at lesion sites. If those sites are also where formation is coupled, we might need to monitor that we’re not locally impairing formation too much. However, this is a known trade-off with all anti-resorptives. The difference here is maybe spatial rather than whole skeleton. In any case, long-term studies would be needed to see if microdamage accumulation is less with targeted NP vs traditional therapy – which would be a big validation of the concept of healthy bone sparing.

Regulatory Hurdles: Introducing a nanomedicine with multiple functional components means regulatory agencies will scrutinize it for safety. A thorough understanding of distribution, metabolism (e.g., what happens to the PLGA and byproducts), and excretion is required. We must demonstrate that none of the components accumulate in organs long-term. PLGA should fully degrade; PEG might accumulate if too high MW (choose PEG MW that can be excreted). These are manageable with known guidelines.

4.1. Future Directions

Assuming our proposal’s aims are met, and the concept is proven in animal models, the next steps would include:

Testing in larger animal models (e.g., osteoporotic non-human primates) to see how it works in a system closer to humans.

Investigating combination therapy: e.g., can we incorporate an anabolic drug into a similar targeted NP (maybe dual delivery)? Or alternate with anabolic therapy in a smart way.

Exploring other bone diseases: The platform could be adapted to deliver different drugs to bone. For example, in bone metastases or multiple myeloma (where lesions are lytic), a similar NP carrying anti-cancer drugs could target bone tumors. Or in osteomyelitis, carrying antibiotics to infected bones. The dual-target approach can be tweaked (change the second ligand to something that targets tumors or bacteria, etc.).

Optimizing the oral delivery further, maybe by designing nanoparticles that exploit receptor-mediated transcytosis in the gut (targeting the neonatal Fc receptor or others).

Cost-benefit analysis and ensuring that adding this technology justifies itself in outcomes, given that oral bisphosphonates are cheap. If our NP can drastically reduce fractures with fewer side effects, it justifies development cost.

4.2. Summary of Expected Impact

We expect that our dual-targeted, stimuli-responsive nanoparticle system will demonstrate:

- -

Higher efficacy in preventing bone loss and fractures due to focused drug action on osteoclasts.

- -

Reduced side effects, as drug action is confined to bones, sparing the GI tract, kidneys, and other tissues from unnecessary exposure.

- -

Better patient adherence to therapy because of an easier dosing regimen and fewer adverse events.

- -

A new paradigm for treating not only osteoporosis but potentially other conditions by using multi-targeted nanomedicines that respond to disease microenvironments.

If successful, this research will lay the groundwork for clinical development of targeted nanotherapeutics in osteoporosis, moving beyond the traditional one-size-fits-all pill towards a smarter, more effective intervention. It addresses a clear clinical need: many patients either cannot tolerate current osteoporosis medications or do not respond optimally; a targeted NP could re-engage those patients and improve outcomes, ultimately reducing the incidence of debilitating fractures.

5. Conclusion

In this proposal, we have outlined a comprehensive plan to develop and evaluate a dual-targeted, pH-responsive nanoparticle for precision osteoporosis therapy. Our nanoparticle leverages state-of-the-art drug delivery principles – combining targeting ligands for bone and osteoclasts with an environmentally-triggered release mechanism – to overcome the limitations of conventional treatments. We have detailed the design rationale, from the PLGA core carrying risedronate to the surface functionalization with bisphosphonate and RANKL-mimetic peptide, and the protective yet clever pH-sensitive coating that guards the drug until it reaches acidic bone resorption sites.

The synthesis approach using emulsion techniques and carbodiimide chemistry is feasible and will yield nanoparticles which we will rigorously characterize for size, drug content, and functionality. Our in vitro experiments will test each aspect of the system: stability in gastrointestinal conditions, selective binding to bone minerals and osteoclast cells, and the ability to suppress osteoclast activity more effectively than non-targeted treatments. Subsequently, the in vivo studies in an ovariectomized rat model of osteoporosis will provide critical proof-of-concept for enhanced bone targeting, improved therapeutic outcomes (higher bone density and strength), and a favorable safety profile relative to free drug.

We expect the results to strongly support our hypothesis that a multi-functional nanoparticle can deliver osteoporosis medication more efficiently and safely. Success would mean that for the first time, an osteoporosis treatment could distinguish between diseased and healthy bone on a cellular level, concentrating its effect only where needed. This would represent a significant advancement in osteoporosis management, potentially reducing side effects like gastrointestinal irritation and rare complications, while maximizing protection against fractures.

Throughout this proposal, we have used a scientific, yet aspirational, tone consistent with a research plan. We have proposed specific methodologies and have been careful to anticipate challenges and include controls to validate the contribution of each component of our system. The knowledge gained from this project will extend beyond a single disease; it will inform the broader field of targeted nanomedicine for bone disorders. In essence, our aim is not just to create another drug delivery vehicle, but to introduce a precision therapeutic strategy that could transform how chronic bone diseases are treated.

The dual-targeted nanoparticle system for osteoporosis has the potential to improve efficacy, reduce side effects, and enhance patient compliance compared to current therapies. If our experimental aims are achieved, the next steps would involve refining the formulation for human use and eventually clinical trials. This line of research holds promise for yielding a new, patient-friendly treatment that better addresses the needs of those suffering from osteoporosis, helping to prevent fractures and improve quality of life on a large scale. We are confident that the proposed work will provide a strong foundation for realizing this vision.

References

- C. Wen et al., “Bone Targeting Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Osteoporosis,” Int. J. Nanomedicine, vol. 19, pp. 1363–1383, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wu et al., “Bone-targeted nano-drug and nano-delivery,” Bone Research, vol. 12, art. 51, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Z. Saifi et al., “Enhancing osteoporosis treatment through targeted nanoparticle delivery of risedronate: In vivo evaluation and bioavailability enhancement,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 2339, 2023.

- P. Rawat et al., “Design and development of bioceramic based functionalized PLGA nanoparticles of risedronate for bone targeting: In-vitro characterization and pharmacodynamic evaluation,” Pharm. Res., vol. 32, pp. 3149–3158, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen et al., “Bone-targeted nanoparticle drug delivery system: an emerging strategy for bone-related disease,” Front. Pharmacol., vol. 13, art. 909408, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ren et al., “An oligopeptide/aptamer-conjugated dendrimer-based nanocarrier for dual-targeting delivery to bone,” J. Mater. Chem. B, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 2831–2844, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Hoque et al., “Bone targeting nanocarrier-assisted delivery of adenosine to combat osteoporotic bone loss,” Biomaterials, vol. 273, p. 120819, 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Vaculíková et al., “Preparation of risedronate nanoparticles by solvent evaporation technique,” Molecules, vol. 19, pp. 17848–17861, 2014.

- D. A. Ossipov, “Bisphosphonate-modified biomaterials for drug delivery and bone tissue engineering,” Expert Opin. Drug Deliv., vol. 12, pp. 1443–1458, 2015. [CrossRef]

- H. Sahana et al., “Improvement in bone properties by using risedronate adsorbed hydroxyapatite novel nanoparticle-based formulation in a rat model of osteoporosis,” J. Biomed. Nanotechnol., vol. 9, pp. 193–201, 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. K. Khajuria et al., “Risedronate/zinc-hydroxyapatite based nanomedicine for osteoporosis,” Mater. Sci. Eng. C, vol. 63, pp. 78–87, 2016.

- X. Pang et al., “pH-responsive polymer–drug conjugates: design and progress,” J. Control. Release, vol. 222, pp. 116–129, 2016.

- H. Hirabayashi et al., “Bone-specific delivery and sustained release of diclofenac via a bisphosphonic prodrug based on the osteotropic drug delivery system (ODDS),” J. Control. Release, vol. 70, pp. 183–191, 2001.

- X. Xing et al., “Bone-targeted delivery of senolytics to eliminate senescent cells increases bone formation in senile osteoporosis,” Acta Biomater., vol. 157, pp. 352–366, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Alhalmi et al., “Nanostructured lipid carrier-based codelivery of raloxifene and naringin: formulation, optimization, in vitro, ex vivo, in vivo assessment, and acute toxicity studies,” Pharmaceutics, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 1771, 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).