Cases Presentation

Case 1

A 52-year-old Caucasian man with a past medical history of polysubstance abuse, bipolar 1 disorder, presented to the emergency department after a fall from over 25 feet with unknown impact and unknown loss of consciousness. On presentation, the patient endorsed pain “everywhere,” and did not remember the fall or the events leading up to the fall. He was intoxicated and a poor historian. Physical examination of the head revealed raccoon eyes, contusions, and lacerations of the head. Examination of the nose revealed nasal deformity, signs of nose injury, and nasal tenderness. Examination of the eyes revealed bilateral eyelid swelling. Cardiovascular examination revealed bilateral radial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial pulses 3+ bilaterally, and left arteriovenous access was present. Pulmonary examination revealed tachypnea. Musculoskeletal examination revealed left knee, left upper leg, and left lower leg tenderness. Skin revealed signs of injury, laceration, and wounds. Neurological exam revealed confusion and a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 14. The E-FAST exam was negative.

Portable chest XR: No acute cardiopulmonary disease.

Portable pelvis XR: Acute nondisplaced comminuted fractures involving intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric regions of the left femur.

CT head w/o contrast: No evidence of intra- or extra-axial bleed.

CT maxillofacial w/o contrast: multiple comminuted depressed nasal bone fractures, anterior right frontal sinus fracture, acute depressed fracture involving the superior middle portion of the left orbital rim with orbital emphysema, and probable acute fracture of the medial right orbital wall is also in orbital emphysema.

CT cervical spine w/o contrast: Intact cervical spine

CT thoracic spine w/o contrast: Intact thoracic spine.

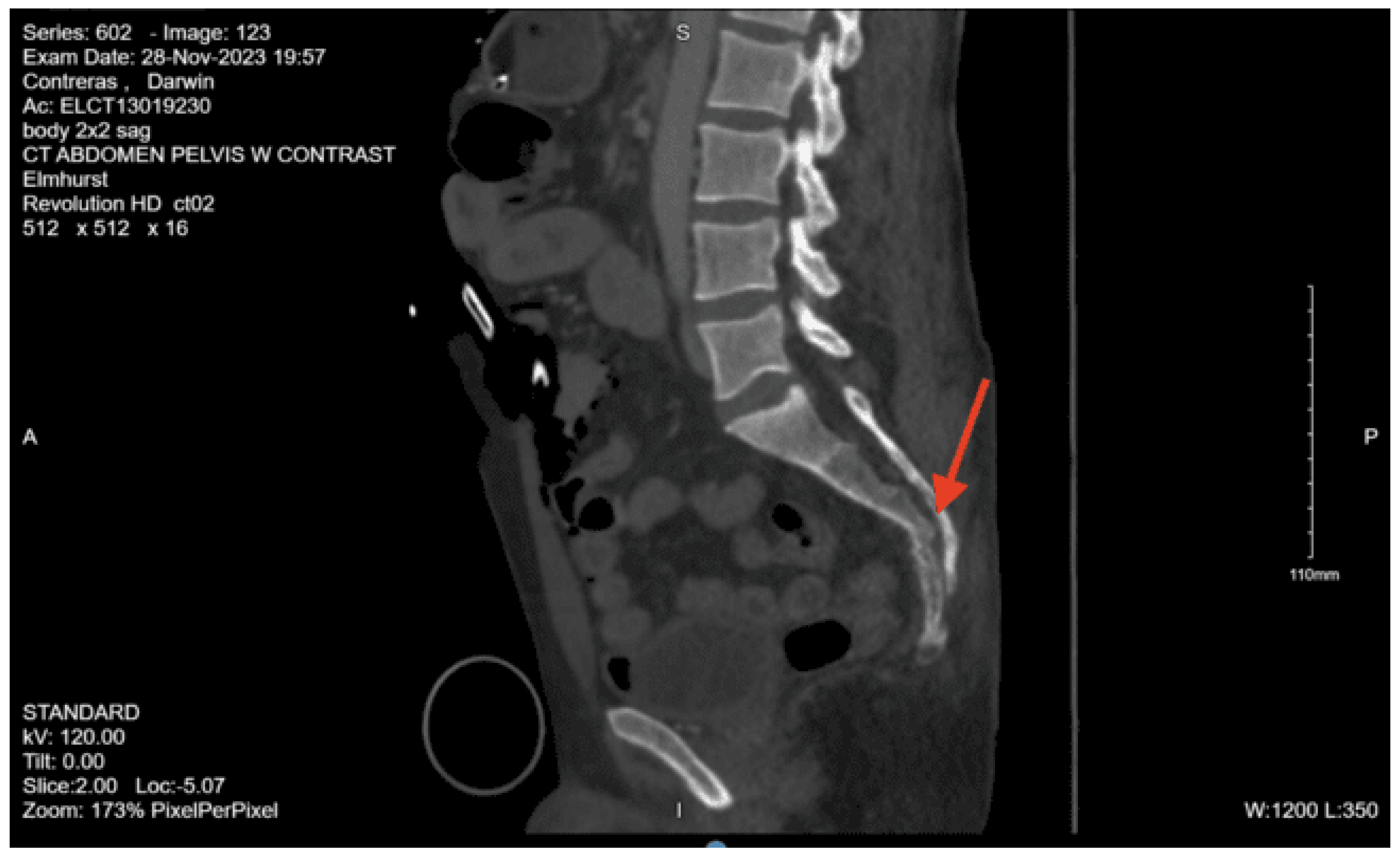

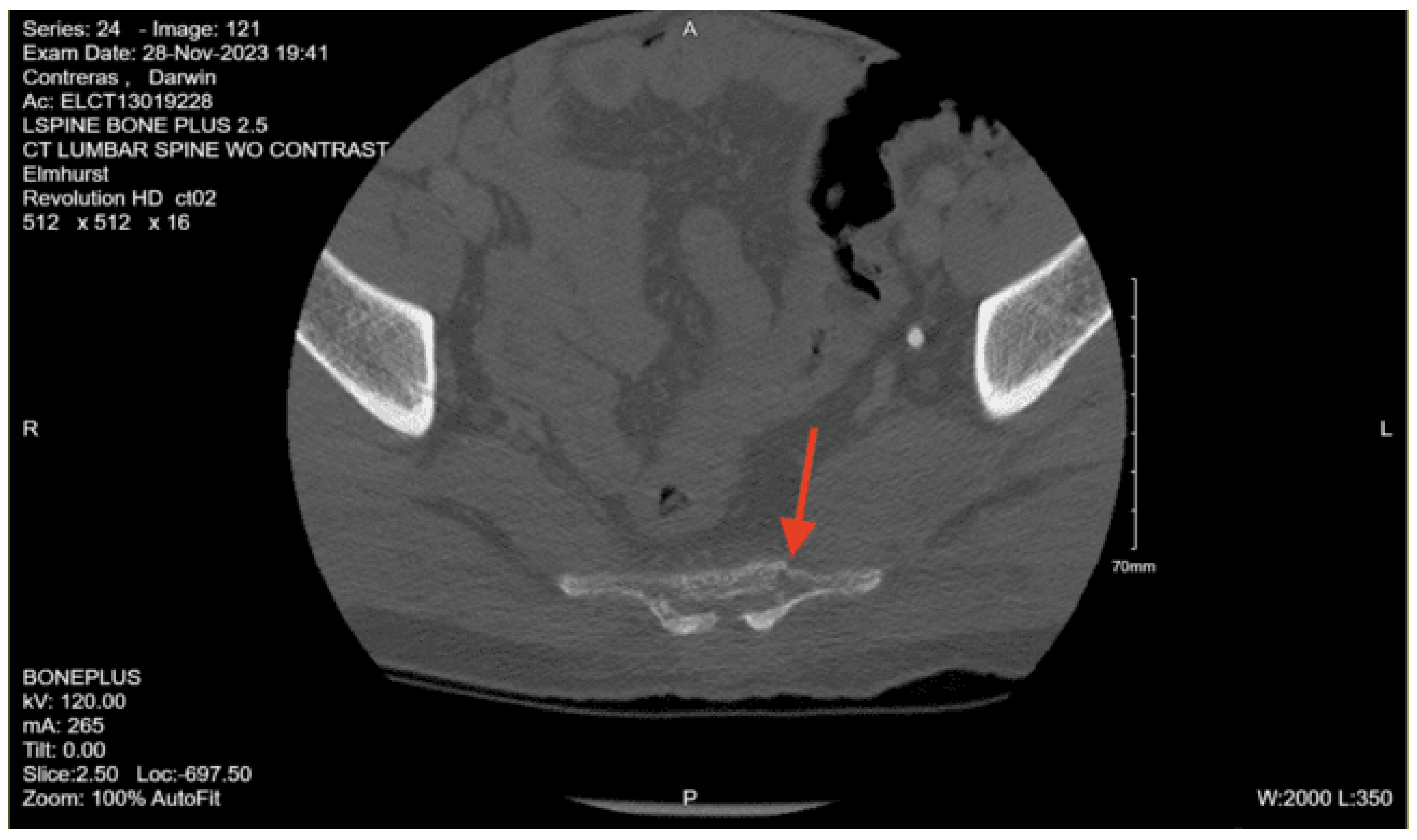

CT lumbar spine w/o contrast: An acute comminuted fracture is seen involving the superior portion of the left sacral wing. The SI joints are intact. Intact lumbar spine.

CT chest with contrast: Grossly unremarkable CT chest.

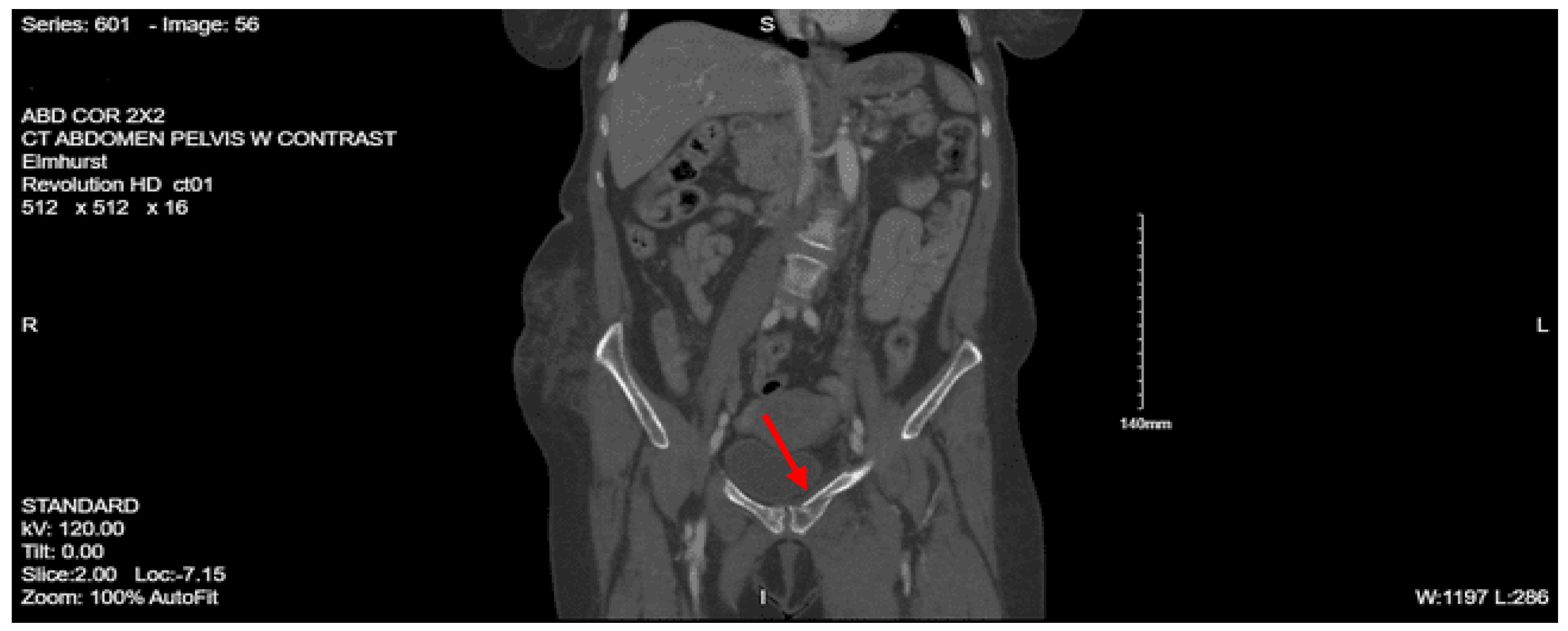

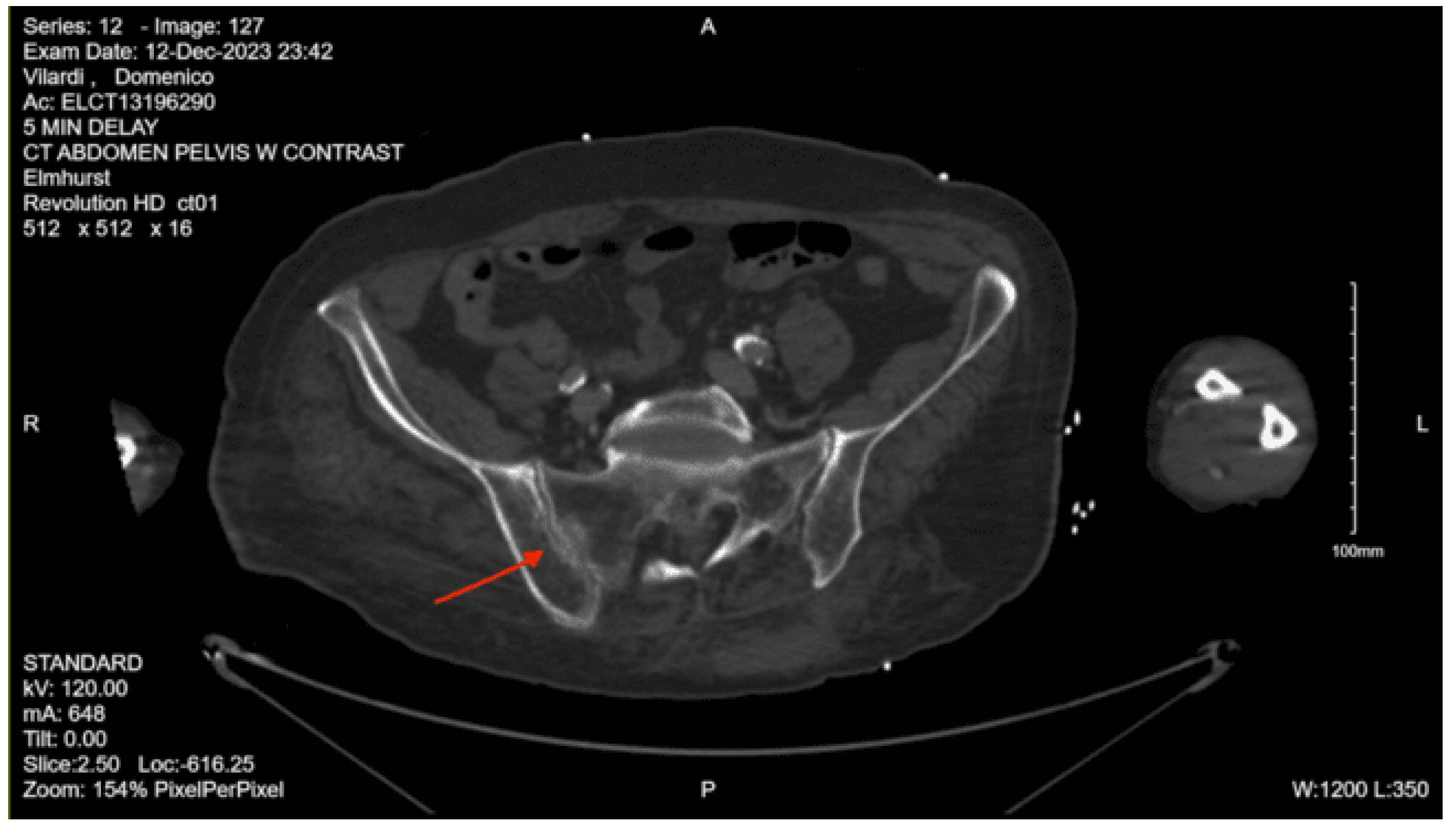

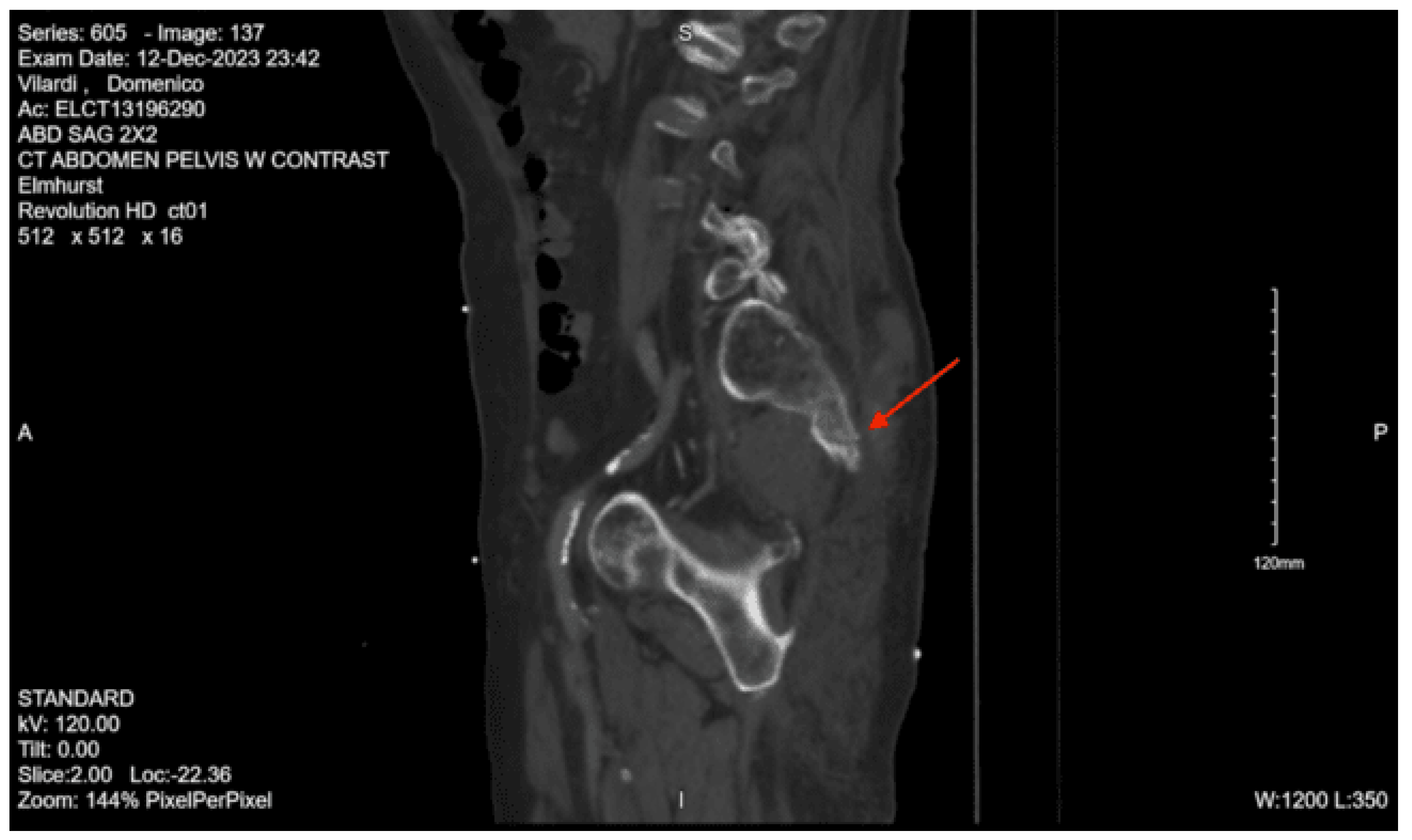

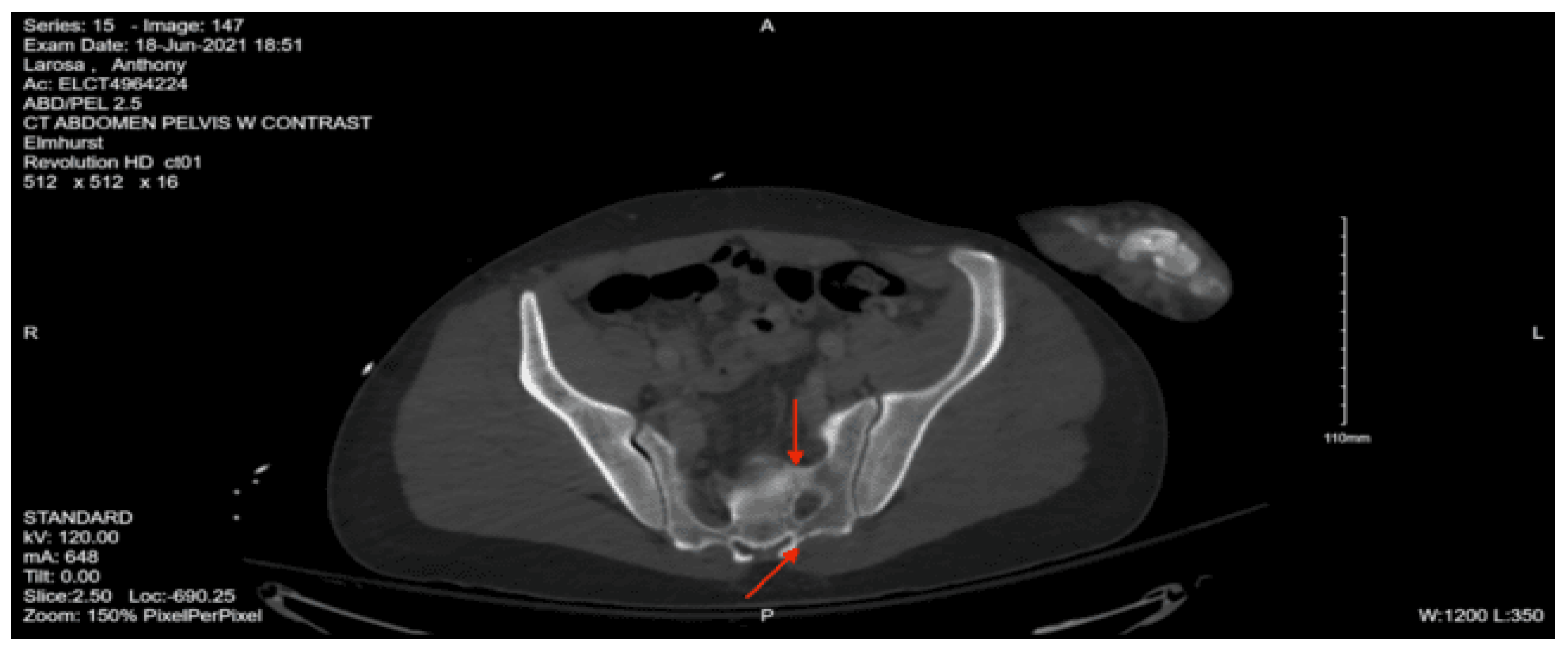

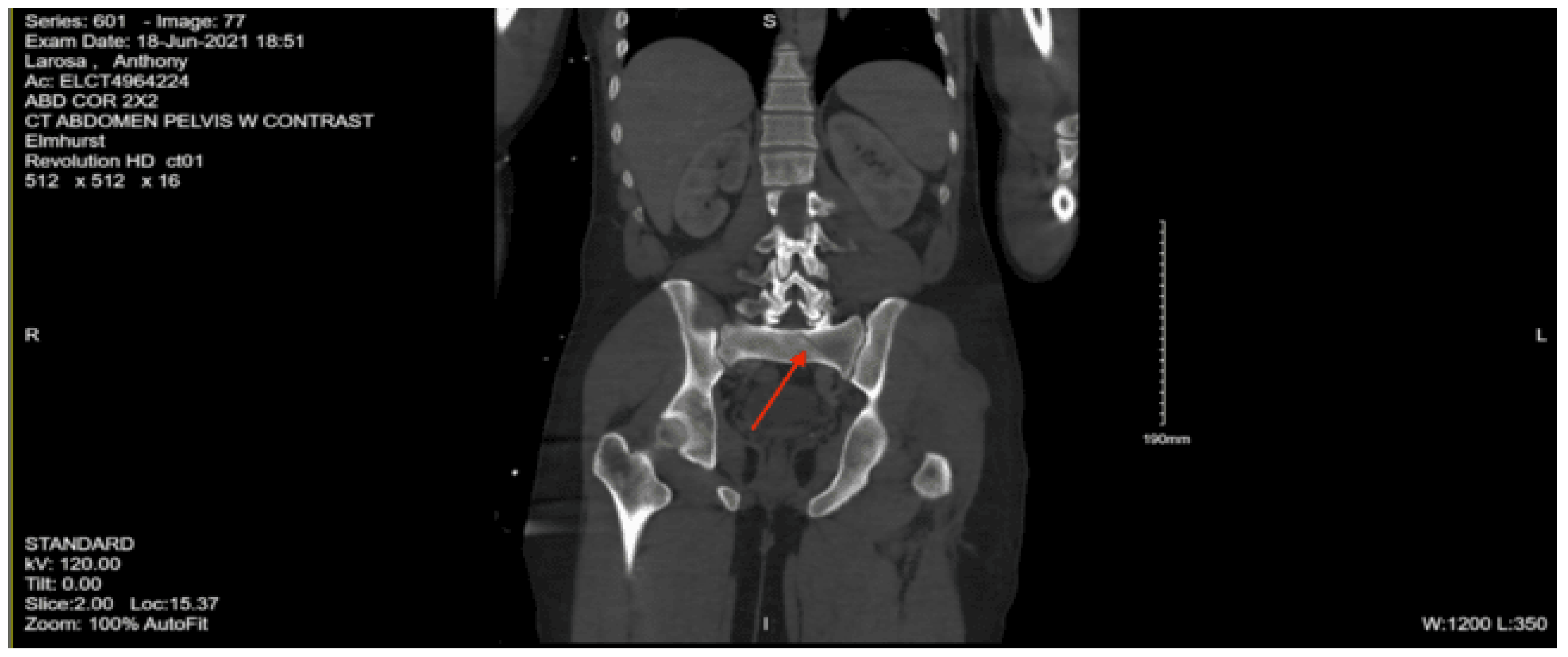

CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast: Acute fractures are seen involving the right superior pubic ramus and left inferior pubic ramus. An acute comminuted avulsed fracture of the left sacral wing in the superior and midportion is demonstrated. No definitive acute traumatic visceral abnormalities were found throughout the abdomen and pelvis.

XR left wrist: Comminuted distal radius fracture with articular involvement.

XR pelvis: Nondisplaced superior ramus fractures. Nondisplaced left lateral sacral fracture.

XR left femur: Acute oblique fracture extending through the greater trochanter and extending about 7 cm inferior to the lesser trochanter. About 3 cm of foreshortening. Adjacent superior pubic ramus fracture.

XR left knee: No distal femur, proximal tibia, or fibula fracture.

XR left tibia and fibula: Spiral fracture distal left tibia shaft exiting above ankle joint. Overall extent 18 cm.

XR right tibia and fibula: No fracture.

Given the patient’s multiple injuries, he was admitted to the SICU for close monitoring and treatment. Plastic surgery was consulted for his facial fractures and recommended starting Unasyn for the open nasal bone fracture and ophthalmology evaluation to rule out intraocular injury. Ophthalmology saw the patient and recommended outpatient follow-up. Orthopedic surgery was consulted for management of the extremity and pelvic fractures, and recommended non-weight bearing for the left lower extremity with a plan to go to the OR the following day, though this was deferred due to his history of recent cocaine use. Neurosurgery was consulted regarding the sacral fracture and recommended non-weight bearing with consideration for surgical vs non-surgical stabilization. On hospital day 3, the patient was found to be in respiratory distress and was subsequently intubated. He was also found to be anemic, and 2 units of pRBCs were transfused. He was successfully extubated on hospital day 5.

On hospital day 7, the patient was taken to the OR by an orthopedic surgeon who performed an open reduction internal fixation of the left femur and insertion of an intramedullary nail of the left tibia. He returned to the OR 2 days later with orthopedic and neurosurgery for percutaneous left SI screw placement with left L5 instrumentation. There was some concern for a possible CSF leak during the procedure, which was managed with bone wax and Duraseal, and no active leak was noted at the end of the case. Post-operative recommendations were to continue bed rest, which was increased to non-weight bearing of the LLE with weight bearing as tolerated for all other extremities on hospital day 13 (post-op day 3). The patient remained disoriented and agitated throughout his SICU stay, and psychiatry was consulted for delirium vs acute psychiatric symptoms and agitation management. On hospital day 15, the patient was transferred to the surgical stepdown unit. Physical medicine and rehabilitation were consulted and recommended beginning physical and occupational therapy, including toe-touch weight bearing of the LLE. They also recommended discharge to acute inpatient rehab when the patient was medically stable.

On hospital day 16, the patient was found to have an altered mental state and was saturating in the 80s with a temperature of 101.6 F, HR 120s, and SBP 160s. He was placed on a non-rebreather mask, which improved his saturation to 90-92%, but he remained unresponsive with a GCS of 3 and was intubated. He was then transferred back to the SICU. On chest x-ray, the patient was found to have a new right lower lobe infiltrate, suspicious of aspiration pneumonia. Two days later, on hospital day 18, the patient was successfully extubated and was transferred back to the stepdown unit the next day. The patient continued to be agitated and uncooperative, at times becoming violent against nursing staff. On hospital day 26, the patient was discharged to subacute rehab with follow-ups scheduled with orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, and neurosurgery. The patient was offered a referral for substance use treatment, but declined.

DX: Denis zone II left sacral alar fx involving S1 foramina. AOSpine B3: NX, M3

Case 2

A 62-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia on aspirin (despite reporting an allergy to aspirin) was brought in by EMS after being struck by a vehicle going approximately 25 mph. The accident was witnessed by her husband. She was thrown backwards and hit the back of her head, and lost consciousness for about 5 minutes. She was not complaining of any pain at the time of the exam, but was not able to recall the incident. On primary survey, she had a GCS of 15, the airway was patent and self-maintained, and she was moving all extremities spontaneously. She was noted to have a 3 cm left lateral scalp laceration and abrasions to the left ankle, anterior foot, and right knee. She had multiple episodes of non-bloody, nonbilious emesis during the exam. Initial vitals were BP 142/97, pulse 106, resp rate 20, temp 98 F, SpO2 93%. No other significant findings were noted. The E-FAST exam was negative.

Portable chest x-ray: No acute cardiopulmonary disease.

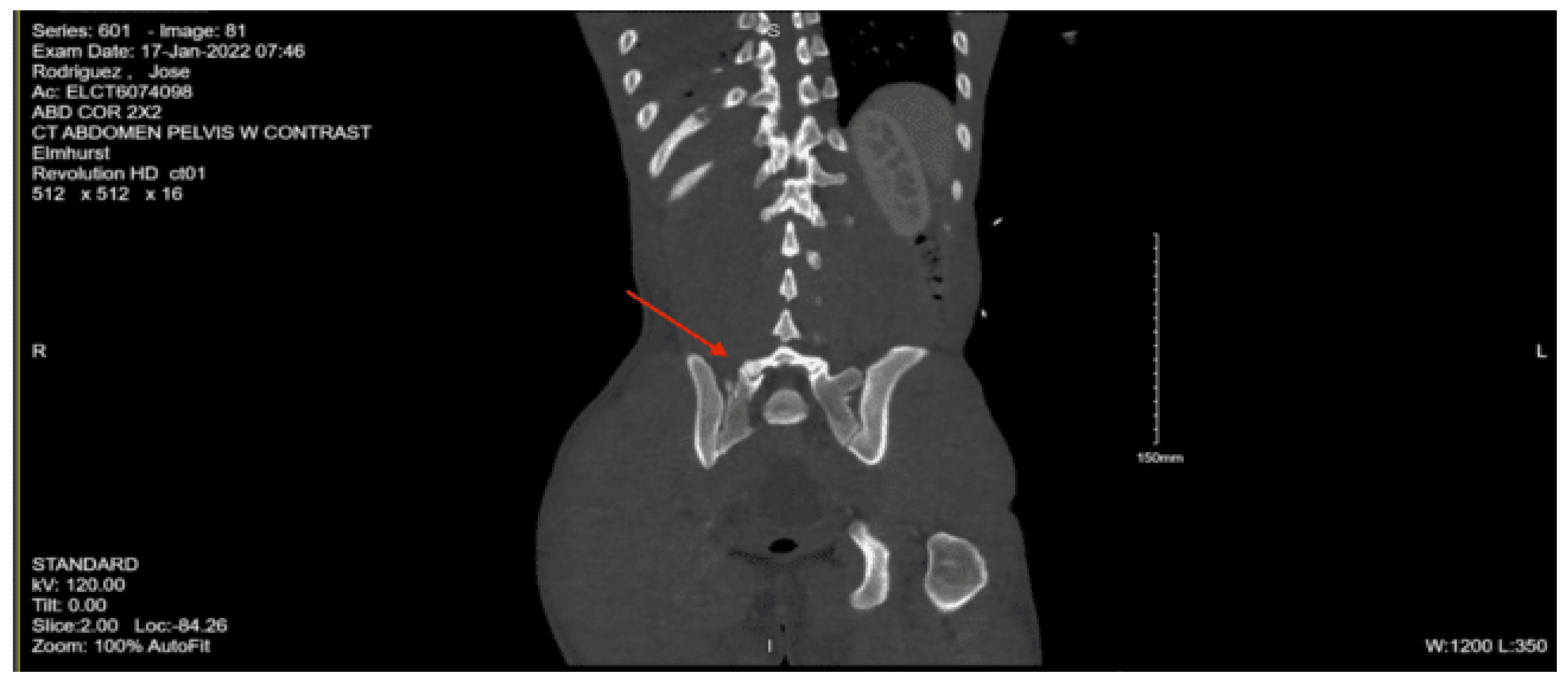

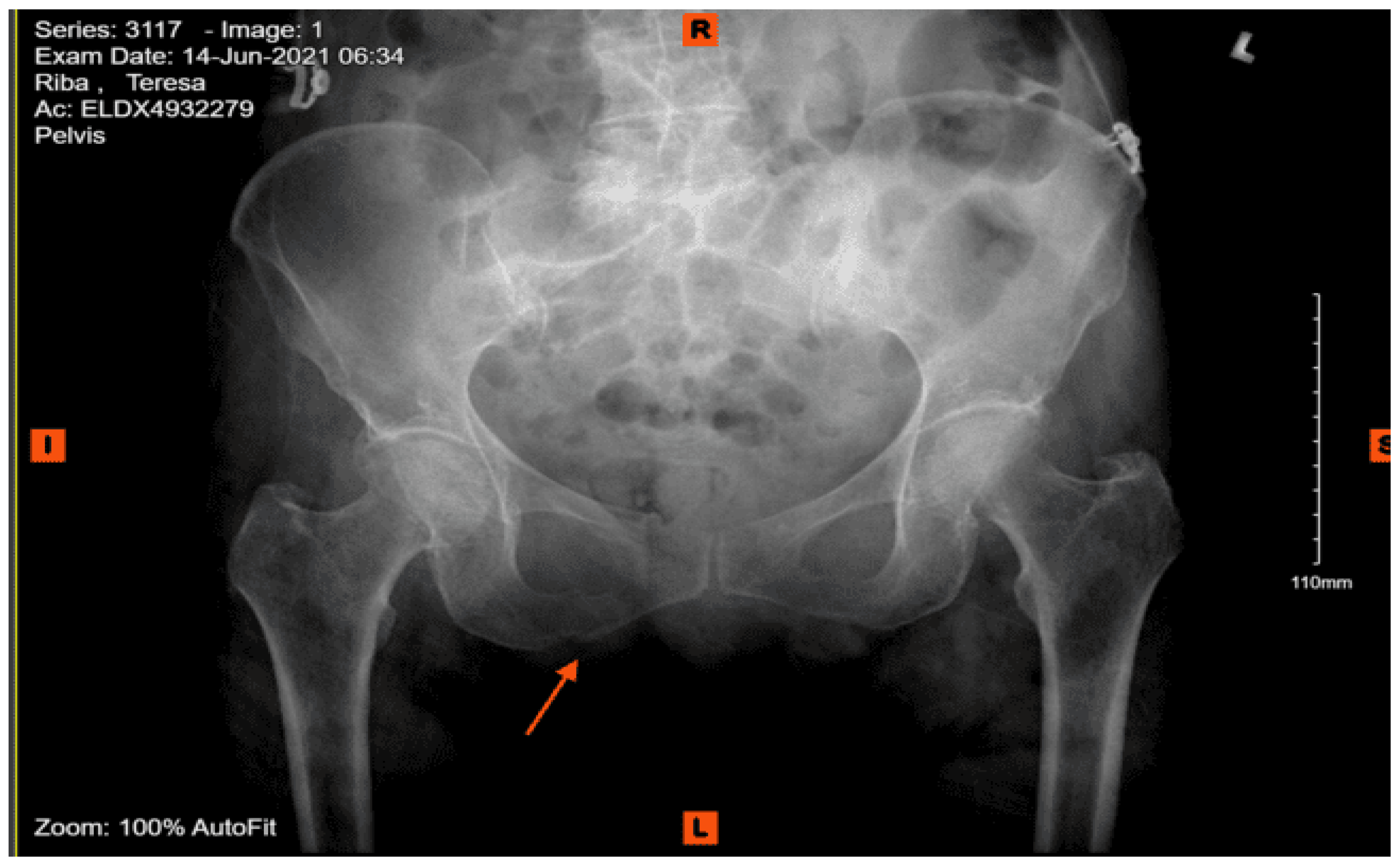

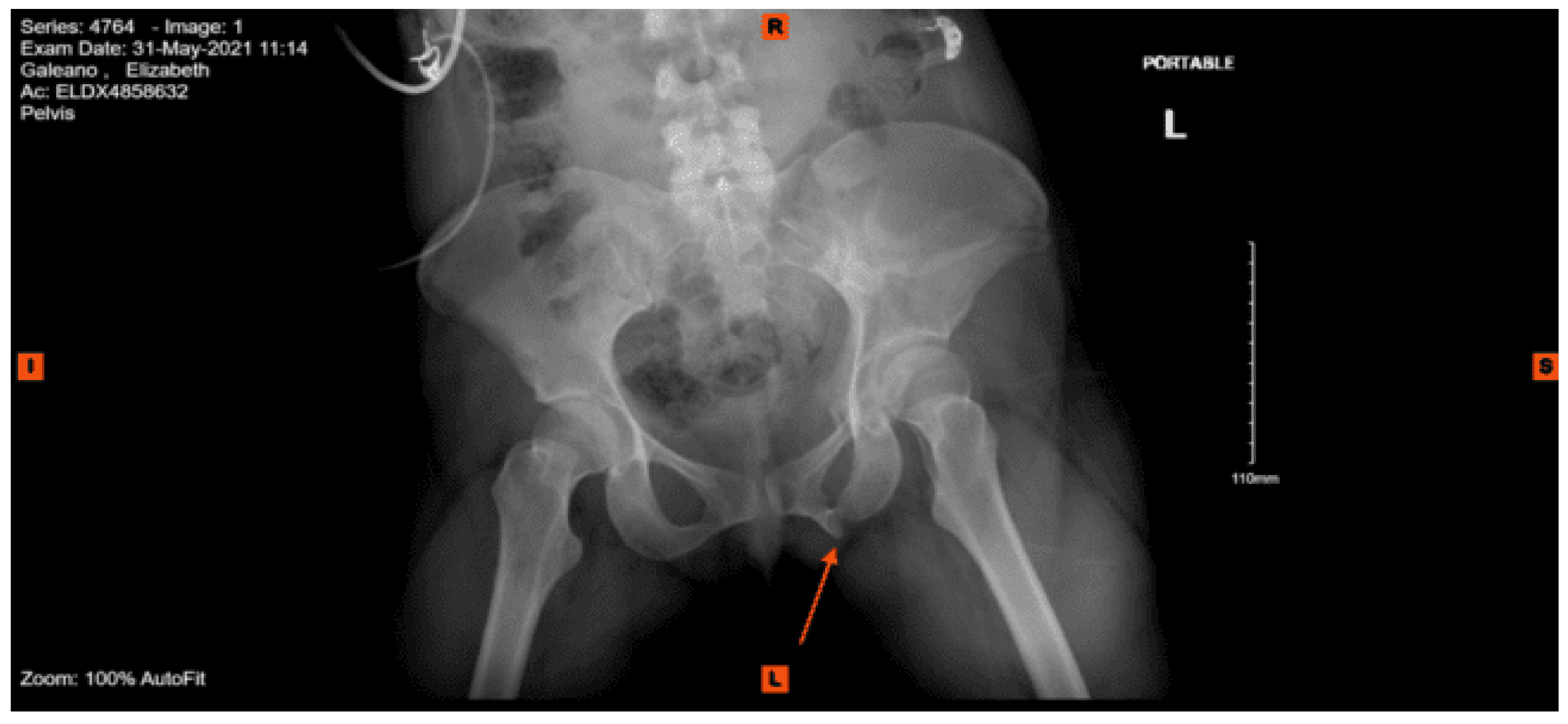

Portable pelvis x-ray: Acute impacted fracture involving the left superior pubic ramus in its medial aspect. Possible fracture, which is nondisplaced, involving the left inferior pubic ramus. The right superior and inferior pubic rami are intact. Femoral acetabular joints were unremarkable.

CT head w/o contrast: Cortical atrophy and microvascular ischemia with diffuse asymmetric areas of subarachnoid blood throughout the frontal and parietal regions, with additional blood within the third and fourth ventricles and posterior aspect of the occipital.

CT cervical spine w/o contrast: Intact cervical spine.

CT thoracic spine w/o contrast: Intact thoracic spine.

CT lumbar spine w/ contrast: Intact lumbar spine.

CT chest with contrast: Grossly normal.

CT abdomen and pelvis with contrast: No acute visceral traumatic abnormality. There is evidence of an acute impacted fracture involving the left superior and inferior pubic rami. The right superior and inferior pubic rami are intact. The sacrum and coccyx appear unremarkable.

XR left tibia and fibula: No evidence of acute fracture.

XR left ankle: No evidence of acute fracture.

XR left foot: No definite evidence of acute fracture.

The patient was found to have a subarachnoid hemorrhage on head CT Neurosurgery was consulted and recommended starting Keppra and repeating head CT. Orthopedic surgery was consulted regarding the pelvic fractures and recommended bed rest. While in the ED, the patient was noted to be tachycardic and hypotensive to 72/50, and was administered 1L lactated Ringer’s. On exam, the patient was found to be minimally responsive and had unequal but reactive pupils, poor rectal tone, and urinary incontinence. She was taken for a repeat head CT, which found increased subarachnoid blood in the bilateral posterior parietal/occipital regions. The patient was transferred to the SICU, where she was found to have a GCS of 5 and continued to be unresponsive and hypotensive; she was subsequently intubated and was transfused 2 units of PRBC and 2 units of FFP under mass transfusion protocol, after which her pressure stabilized. Neurosurgery was made aware of the patient’s change in mental status and recommended a repeat head CT, which was stable, and an additional unit of FFP. She was taken to interventional radiology to assess for acute bleeding, which was not found. CT head with contrast on hospital day 4 showed multiple areas of vessel narrowing, likely post-traumatic vasospasm.

During her hospital course, the patient was also found to have a right lateral tibial plateau fracture and bilateral sacral ala fractures; orthopedic surgery recommended non-weight bearing for the RLE, and neurosurgery recommended bed rest. She required multiple blood transfusions due to repeated drops in hemoglobin/hematocrit but remained hemodynamically stable. Given her continued intubation status, tracheostomy was performed on hospital day 8. Continued monitoring via CT head with and without contrast continued to show evolving strokes and persistent severe vasospasm. On hospital day 13, the patient was seen by physical medicine and rehabilitation, who recommended physical and occupational therapy and TBI unit vs sub-acute rehab for discharge when the patient was medically stable. The patient’s mental status gradually started to improve, and she was transferred to the surgical stepdown unit on hospital day 15. On hospital day 19, PEG was placed by interventional radiology. The patient continued to slowly improve, and tracheostomy decannulation was performed on hospital day 36; then she was discharged to TBI rehab 3 days later.

Case 3

An 18-year-old female with no past medical history was brought in by EMS after being found down in the snow under a fire escape from a fall from third-story window. Patient was A&Ox0, initially somnolent but became more responsive in the trauma bay. She was complaining of severe back pain. She reported that she jumped from her fire escape. Per the patient’s parents, the patient has no history of mental illness and is an honor student and senior in high school. EMS was unable to get a blood pressure reading in the field. In the ED, the patient was found to be hypotensive with an SBP in the 60s, so the massive transfusion protocol was initiated, and a pelvic binder was placed. Physical exam was remarkable for externally rotated right hip and abrasion of the left glute, tenderness to palpation in the thoracic and lumbar spine, and questionable pelvic stability. The patient was moving her upper extremities but not her lower extremities. E-FAST and chest X-ray were both unremarkable. After 3 units of PRBCs and 1 bag of platelets, her SBP went up to the 110s, and the decision was made to bring the patient to CT.

Portable chest x-ray: Unremarkable.

Portable pelvis x-ray: Limited view reveals fracture of the right mid-iliac bone with minimal displacement. Possible inferior pubic ramus fracture or acetabular fracture. Bowel gas pattern is nonspecific. The left hip appears intact.

CT head w/o contrast: small acute subdural hematomas in the left tentorial region and left frontal and temporal regions without significant mass effect.

CT maxillofacial w/o contrast: Normal study of the facial bones.

CT cervical spine w/o contrast: Normal CT scan of the cervical spine.

CT thoracic w/o contrast: Compression fractures with mild anterior wedging deformities involving superior endplates of vertebral bodies of T6, T7, T8, T11, and T12. Fracture of T8 vertebral body is comminuted and somewhat displaced. No abnormalities noted in the spinal canal.

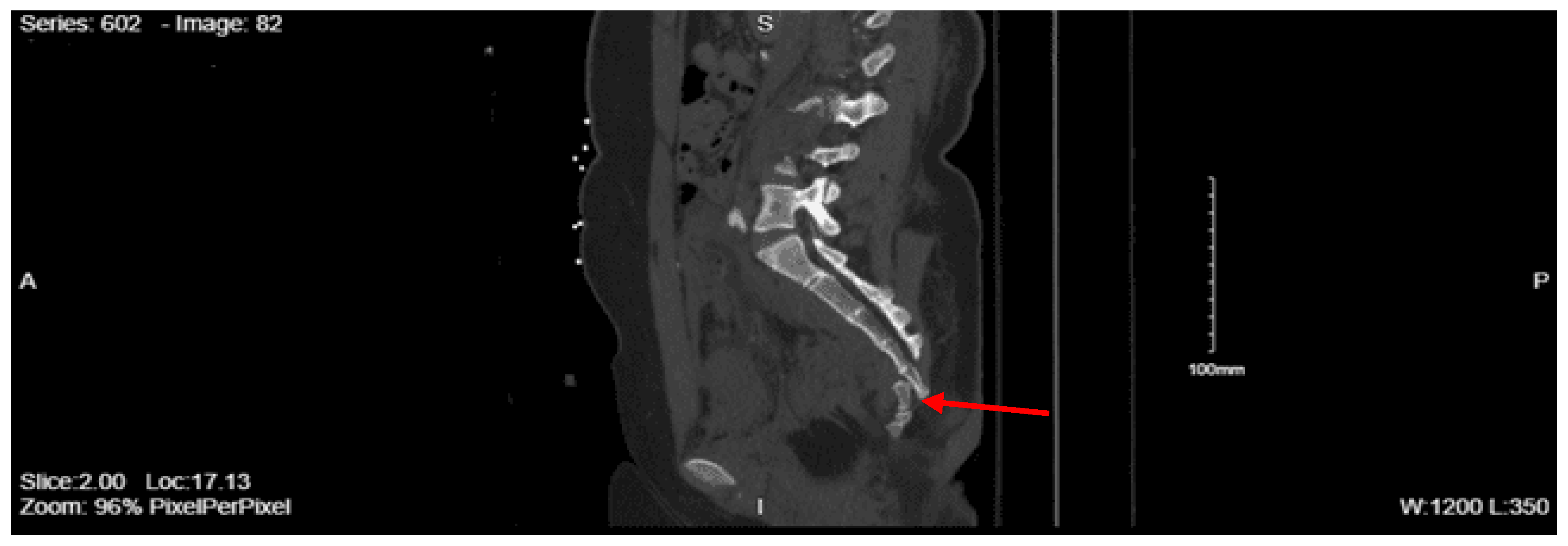

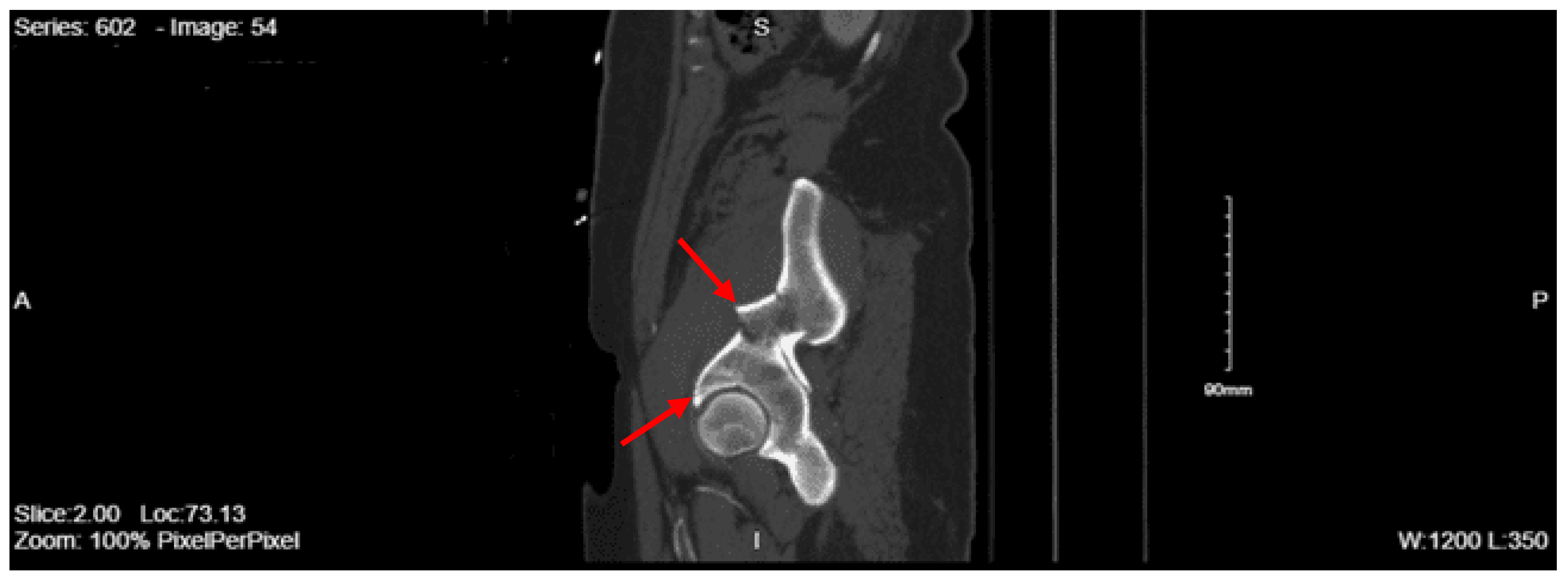

CT lumbar w/o contrast: L3 burst fracture with marked loss of vertebral body stature and retropulsion of fracture fragments completely effacing the spinal canal. There is substantial kyphosis at L3. Displaced L3 transverse process fractures were also demonstrated. L2 burst fracture with mild loss of vertebral body stature. T12 compression fracture with mild loss of vertebral stature. There are anterior paraspinal hematomas adjacent to the L2 and L3 fractures.

CT chest with contrast: Left 4th, 5th, and 6th rib fractures anterolaterally. Nondisplaced manubrial fracture. Trace hemorrhage in the anterior mediastinum. Trace left-sided pneumothorax.

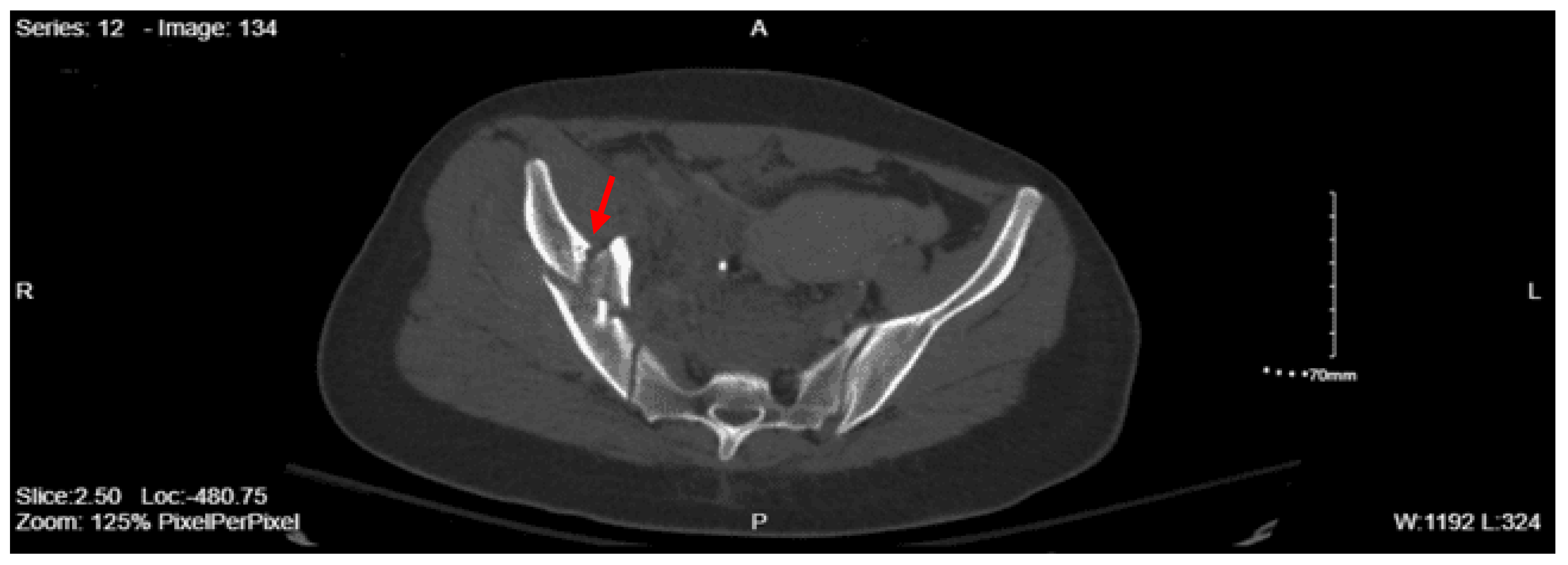

CT angiography abdomen and pelvis with runoff: No visualized arterial blush or pooling of contrast on delayed phase to suggest active arterial bleed. The distal portion of the sacrum is fractured and displaced anteriorly. There is a comminuted fracture through the right iliac bone with moderate displacement. There is a moderately displaced fracture through the right inferior pubic ramus. There are mildly displaced fractures of the right anterior and posterior acetabulum. The anterior fracture appears to involve the articular surface. There is a hemorrhage surrounding the right iliac fracture and a small volume hemorrhage in the right pelvic sidewall and the presacral space. There is a small volume of hemorrhage surrounding the urinary bladder.

A right femoral traction pin was placed by an orthopedic surgeon in the ED. Neurosurgery was consulted for the patient’s multiple spinal fractures and decided to bring the patient to the OR for L1-L5 posterior fusion, L2-3 laminectomy, and L3 corpectomy and cage. A chest tube was also placed on the left in the OR for the pneumothorax. She remained intubated and was admitted to the SICU with post-op instructions of lying flat for 24 hours. Repat CT head showed an expansion of the subdural hematoma, and neurosurgery recommended Keppra for seizure prophylaxis and repeat CT head. The next day, the patient was successfully extubated, and upon further questioning, admitted to trying to hurt herself by jumping out of the window, she was placed on 1:1 monitoring as recommended by psychiatry. Upon reevaluation by orthopedic surgery, they recommended going to the OR after the patient had been medically stabilized. On hospital day 3, the patient underwent flexible sigmoidoscopy to rule out rectal injury; no injury was found. The next day, her chest tube was successfully removed. The patient was found to have a small pulmonary embolism on chest CT, and an IVC filter was placed by interventional radiology on hospital day 7 in preparation for the orthopedic surgery procedure. Later that day, the patient underwent open reduction internal fixation of the right acetabular anterior column and ilium with post-op recommendations of bed rest. Since admission, the patient remained unable to move both lower extremities, though she did gradually regain sensation. She was also unable to void and required intermittent straight catheterization. On hospital day 12, she was evaluated by physical medicine and rehabilitation, who recommended starting bedside physical and occupational therapy, out-of-bed to chair with lift assistance, and discharge to spinal cord injury inpatient rehab if the lower extremity weakness persists. She was transferred to the surgical stepdown unit on hospital day 14. Over her remaining hospital course, the patient regained some ability to move both lower extremities. On hospital day 33, she was discharged to spinal cord injury inpatient rehab.

Case 4

A 33-year-old male with a past medical history of alcohol use disorder was brought in by EMS. The patient was reportedly found on LIRR tracks after having been struck by a train and flung off the tracks. Multiple facial lacerations were noted on arrival, with a bloody airway in the trauma bay. The patient was agonizingly breathing, and EMS was bagging the patient. He had palpable pulses in all four extremities, initial GCS 7 (M4 V2 E1). Vitals were HR 75, RR 32, BP 133/83, SPO2 95%, T 36.7 °C. Given concern for inability to protect the airway, the patient was given fentanyl for premedication, and was subsequently intubated, he was also given hypertonic saline, given depressed GCS, and tranexamic acid. Initial E-FAST was negative, but the patient became hypotensive (BP 40/28, HR 123, RR 32, O2 Sat 97%). A repeat E-FAST exam was positive in the suprapubic region, mass transfusion protocol was activated, and the patient was taken directly to the operating room with trauma surgery.

The patient was taken emergently to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. The findings in the operating room were pooling of blood in the left upper quadrant and multiple large splenic lacerations, evident with active bleeding and a 5cm serosal tear of the transverse colon. The patient underwent splenectomy, repair of the transverse colon, and left chest tube placement for a small left pneumothorax. The patient was admitted to the surgical ICU for close monitoring and management of critical polytraumatic injuries. The patient subsequently had a whole-body CT scan, showing: CT head non-con with no intracranial bleed, significant injuries including left pneumothorax with left lower lobe infiltrates, right 1-3, 11-12 rib fractures, left 2, 5-10 rib fractures, left scapula comminuted displaced fracture, C4 fracture with C4-5 joint widening, C3-4 right transverse process fracture, C7 left transverse process fracture, right T1 transverse process fracture, left T2 transverse process fracture, T3 vertebral body fracture, left L3-4 transverse process fracture, transverse S4 fracture, bilateral nasal bone fractures, bilateral medial orbital wall fractures, right orbital roof fracture, left orbital roof fracture.

The patient was taken back to the operating room the next day for abdominal washout and closure. His SICU course was complicated by worsening neurological exam - repeat CTH demonstrated small left greater than right subdural hygromas, interval development of a small amount of layering subdural hemorrhage along the left tentorium, and prominent bilateral scalp soft tissue swelling. MRI of the brain and c-spine revealed no acute spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery was consulted and evaluated the patient, recommended starting Keppra for seizure prophylaxis, placement of a Miami J-Collar for 8 weeks, C-spine precautions, and outpatient clinic follow-up in 8 weeks. Ophthalmology was consulted, given traumatic findings, and given that on his physical exam, there was no evidence of entrapment or detachments, there was nothing to do on their end. ENT was consulted and evaluated the patient. He had an exam notable for right cranial nerve VII palsy but required no acute interventions and outpatient follow-up. Orthopedic Surgery was consulted, and they evaluated the patient for left scapula fracture and recommended using a sling and non-weight bearing for the left upper extremity.

The patient was discovered to have a free fluid collection in the pelvis, so paracentesis was performed. Cultures grew gram-positive cocci in pairs. Repeat CT abdomen pelvis with IV contrast showed left lower lobe collapse, near complete right lower lobe collapse with moderate left pleural effusion, heterogenous enhancement of the liver, and no opacification of the hepatic veins. Abdominal ultrasound revealed flow in the hepatic and portal veins. The patient was started on IV antibiotics. During his course, the patient had a complaint of chest pain. He had an EKG done, which showed t-wave inversions, so cardiology was consulted and recommended to order a high-sensitivity troponin and to trend it until peak, and stated that there was a low concern for acute coronary syndrome. A repeat CT head was performed, and no acute intracranial finding was observed. Toward the end of his ICU course, the patient was evaluated by Speech-Language Pathology, which conducted a Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) and recommended regular solid foods with thin liquids. The patient progressed well and was downgraded from the ICU to the step-down unit and then proceeded to downgrade to the regular trauma surgery floor. He was evaluated by physical therapy and occupational therapy, who recommended his disposition to be acute rehab. Towards completion of his hospital course, the patient was evaluated by the hospital’s substance use support team, and the patient refused linkage to rehab but was provided with resources. Given his splenectomy, the patient received the following vaccines: pneumococcal Prevnar 20, Meningococcal B Bexsero, Haemophilus B ACTHIB on hospital day 17, and COVID, Flu, and Meningococcal (ACWY-Menveo) vaccine on hospital day 30. The patient was ultimately discharged to acute rehab in stable condition on hospital day 30.

Case 5

A 95-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension on losartan 25mg, chronic kidney disease, was brought in by EMS with her daughter after a fall 3 days prior when going down the stairs and fell three steps, landing on her right side while also striking her head. She was found down on the floor by her daughter and went to an outside hospital the same day. She had a CT head, CT c spine, right shoulder, and right hip X-rays that showed no acute pathology. She was discharged home but had not been able to stand, sit, or ambulate since the incident (ambulates without assistive devices at baseline). In the ER, the patient was complaining of right upper back pain, shoulder pain, and hip pain, with no headache, nausea, vomiting, or numbness. On arrival, her vital signs were BP 156/84, HR 72, temp 36.7, RR 18, SpO2 97%. On the primary survey, her airway was patent and intact. She had bilateral breath sounds. Her extremities were warm and well perfused - she had palpable distal pulses in all extremities. Her GCS was 15. On secondary evaluation, she had a right forehead abrasion, no battle sign or raccoon eyes. Her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. Her extraocular motion was intact. She had no posterior midline tenderness to palpation. She had normal heart sounds and had normal chest excursion. Her pelvis was stable. Some bruising was noted on the right shoulder, but she had no gross deformities. Her E-Fast was negative for any free fluid.

CT Head w/o contrast: small acute subdural hemorrhage along the right frontal convexity measuring 6 mm

CT cervical spine: no acute fracture or traumatic listhesis

CT thoracic spine w/o contrast: no acute fractures or subluxations

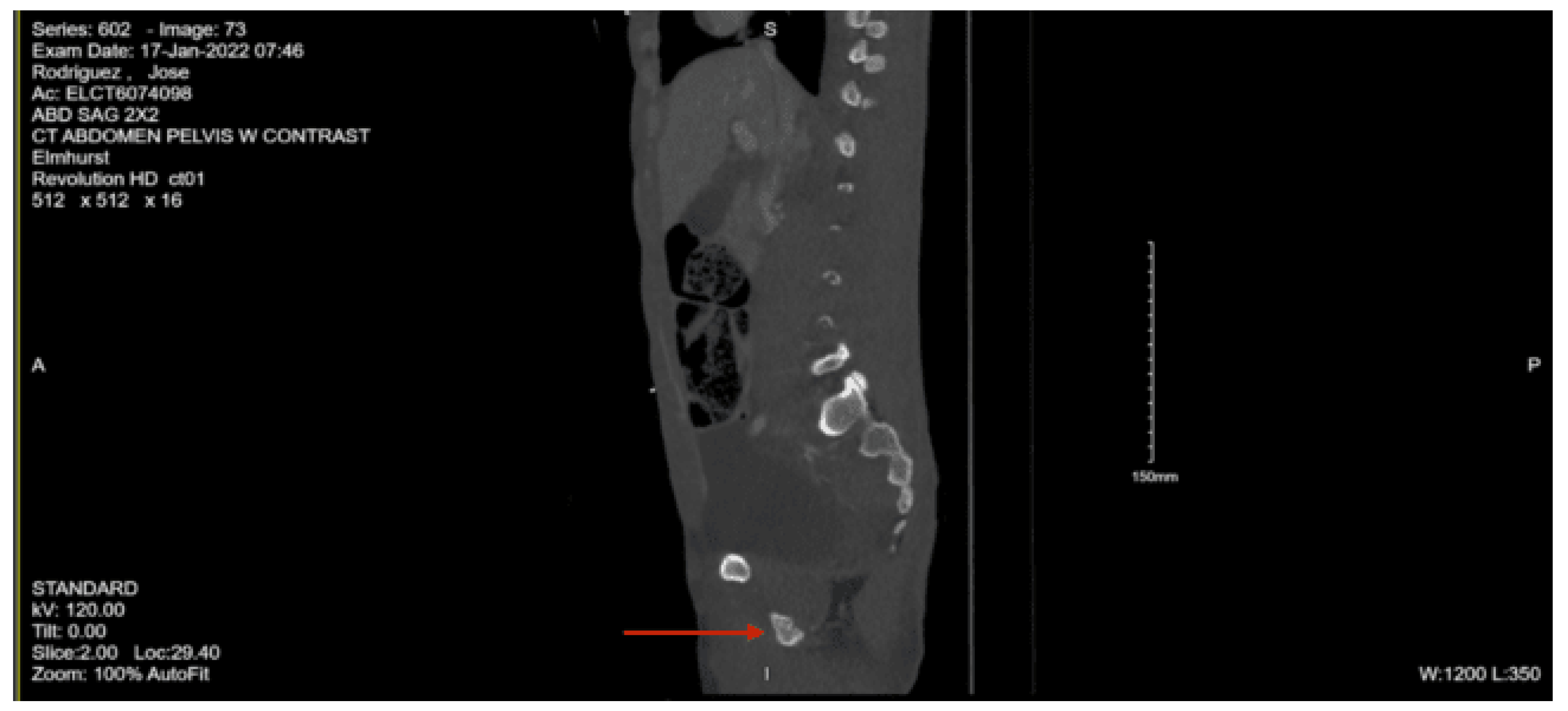

CT lumbar spine w/o contrast: Nondisplaced sacral fracture, approximately at the level of S4. Deformity at the sacrococcygeal junction, indeterminate chronicity. No other fractures identified. Diffuse osteopenia. Degenerative changes within the lower lumbar spine with grade 1 anterolisthesis of L4 over L5. No acute lumbar spine fractures identified

CT chest w/o contrast: non-displaced fracture of the right distal clavicle, fractures of the right 3rd and 4th ribs, bilateral pulmonary nodules, largest 10mm nodule within right lower lobe

XR Pelvis complete: no displaced fracture identified

CT pelvis w/o contrast: Nondisplaced sacral fracture, approximately at the level of S4. Deformity at the sacrococcygeal junction, indeterminate chronicity. No other fractures identified. Diffuse osteopenia. Degenerative changes within the lower lumbar spine with grade 1 anterolisthesis of L4 over L5

XR shoulder right: no dislocation or acute displaced fracture identified

XR clavicle right: distal right clavicular fracture, right lateral 4th rib fracture

XR shoulder axillary view, right: no gross acute abnormality

CT Right shoulder w/o contrast: non-displaced fracture of the right distal clavicle, fractures of the right 3rd and 4th ribs

Repeat CTH, small right convexity subdural hematoma, not significantly changed

The patient was admitted to the surgical stepdown unit. Neurosurgery was consulted for the sacral fracture, they recommended no neurosurgical interventions at the moment, adequate pain control, good bowel regimen, and standing pelvic X-rays when tolerated. For her subdural hematoma, they recommended obtaining a thromoelastogtram, load with Keppra 20 mg/kg followed by 500mg every 12 hours for a total of 3 days, and repeat CT head in 4-6 hours. Her repeat CT head was stable, so the team was told to continue Keppra 500mg twice a day for 7 days and follow up with neurosurgery in the clinic, concussion monitoring and precautions, and for the sacral fracture, she was told to follow up with her primary care provider.

Orthopedic surgery was consulted for the right distal clavicle fracture and recommended non-weight bearing for the right upper extremity in a sling, pain control, and given follow-up. While admitted to the surgical step-down unit, she was placed on a rib fracture protocol. On her second hospital day, she was started on Lovenox 30mg daily, and the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation team was consulted and recommended that the patient start physical and occupational therapy. On hospital day 5, she was seen by physical therapy, and they recommended that after medical optimization, she should be discharged to subacute rehab. On hospital day 8, she developed a cough and tested positive for COVID-19 19 so she was given Paxlovid for 5 days. On hospital day 14, she was discharged to a subacute rehab facility.

Case 6

An 86-year-old male with a past medical history of thyroid disease, hypertension, and coronary artery disease on apixaban presented to the Emergency Department for an unwitnessed fall. Per the family, they heard a thud and attended to the patient, who was initially responsive and following commands. The family states he fell two steps with a head strike and loss of consciousness. On arrival, the patient had reported worsening in his mental status. His vitals on arrival were HR 102, BP 204/97, RR 17, SpO2 99%, T 37.1. On the initial survey, the patient’s airway was intact and protected. The patient had a C-collar in place. He had bilateral breath sounds and palpable distal pulses in all four extremities. His GCS was 14. He had a laceration and hematoma to the posterior scalp that was 2cm long, no hemotympanum, and dried blood in the nares. The neck had no visible injury, and the trachea was midline. The chest had no visible deformities and no bony instability. The abdomen had no visible injuries and was soft and flat. The pelvis had no visible injury and was stable to compression. The extremities had no visible injuries, no bony instability, full range of motion, and no distal pulse deficit.

Portable Chest XR: No acute findings

Portable Pelvis XR: No acute fracture or dislocation, severe right hip osteoarthropathy with extensive bony remodeling of the superolateral femoral head

CT head non-con: Enlarged right lateral ventricle, suggesting early entrapment/hydrocephalus. Extensive rightward midline shift measuring up to 2cm related to a hyperacute left holohemispheric subdural hematoma measuring up to 1.1 cm in greatest coronal dimension. Worsening left uncal herniation. Loss of gray-white differentiation in the anterior left temporal region is concerning for early infarct. Extensive scattered subarachnoid hemorrhage along the bifrontal regions and left frontotemporal region. Large left temporal scalp hematoma with nondisplaced, mildly comminuted left temporal/parietal bone fracture.

CT Angio Head with contrast: Acute occlusion of the left anterior temporal branch of the left MCA with loss of gray-white differentiation in the anterior left temporal lobe.

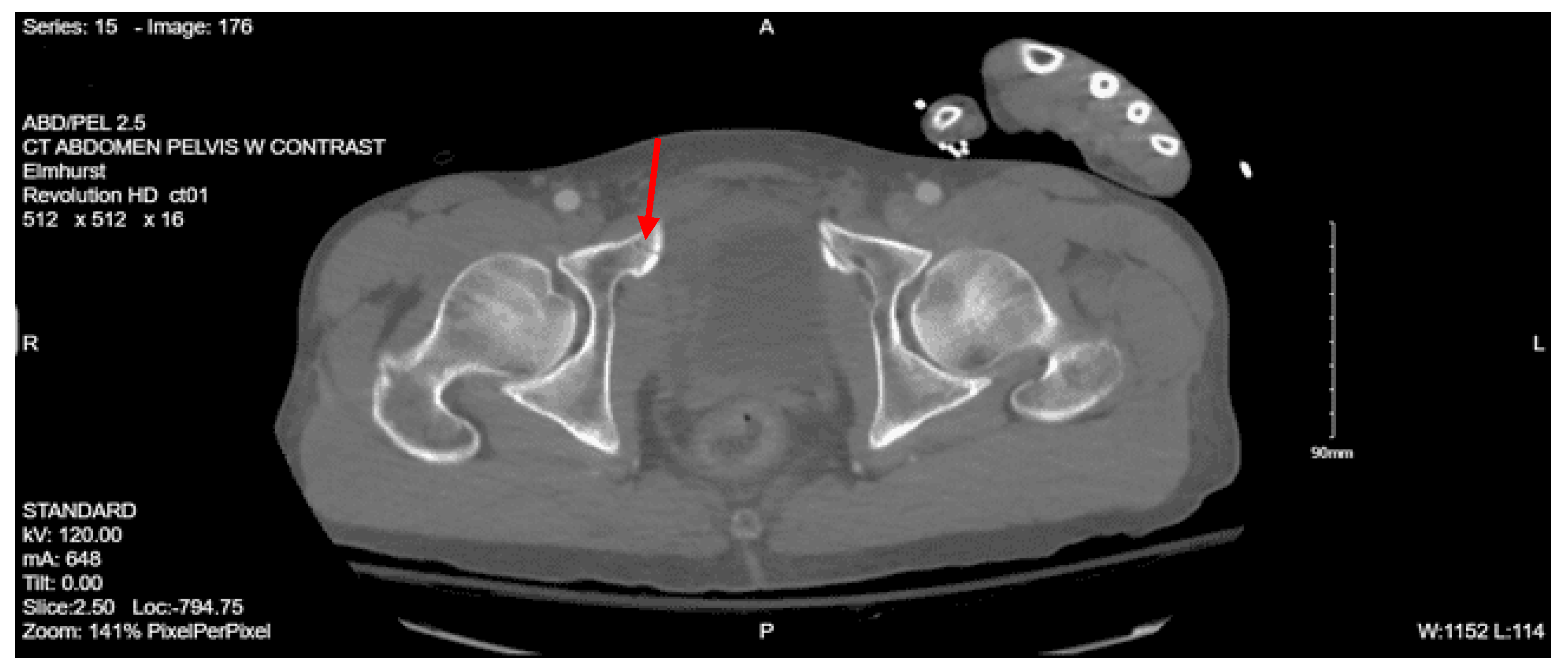

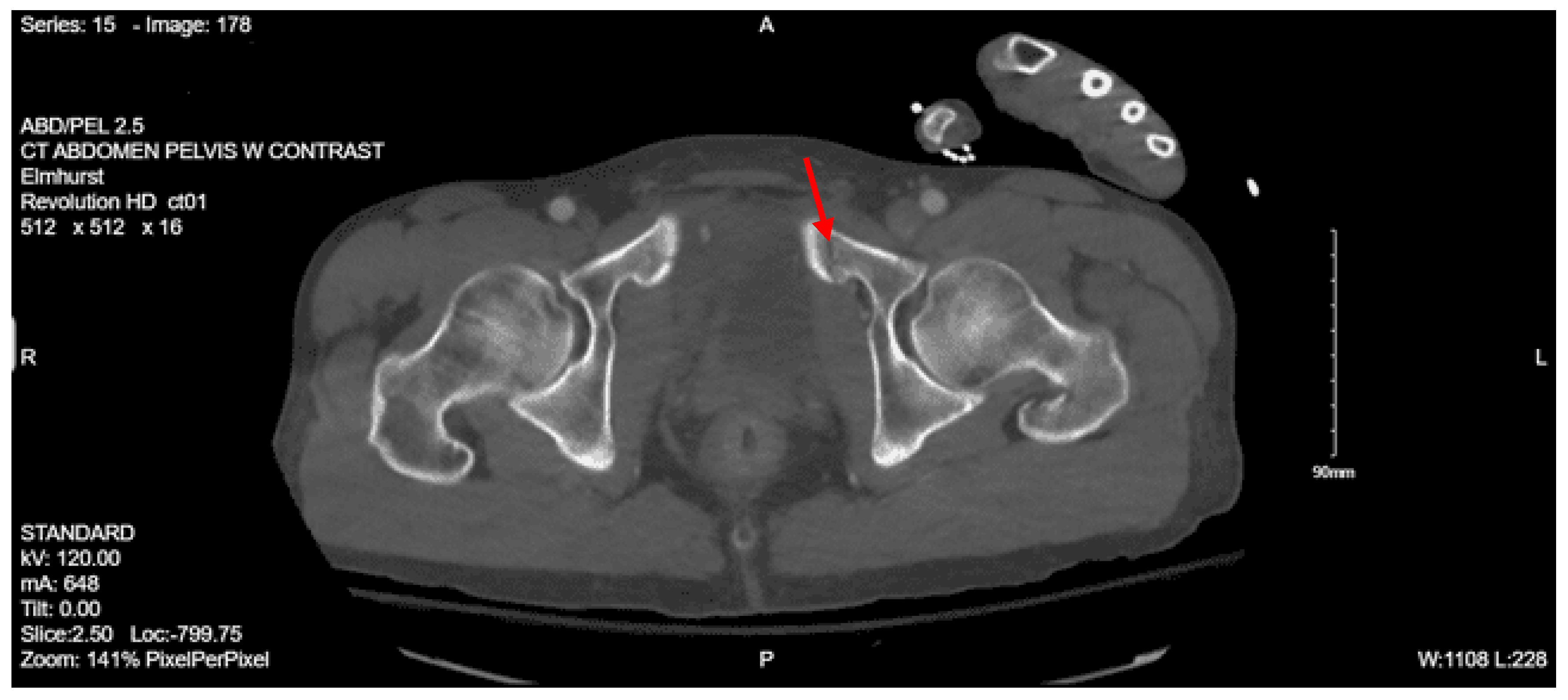

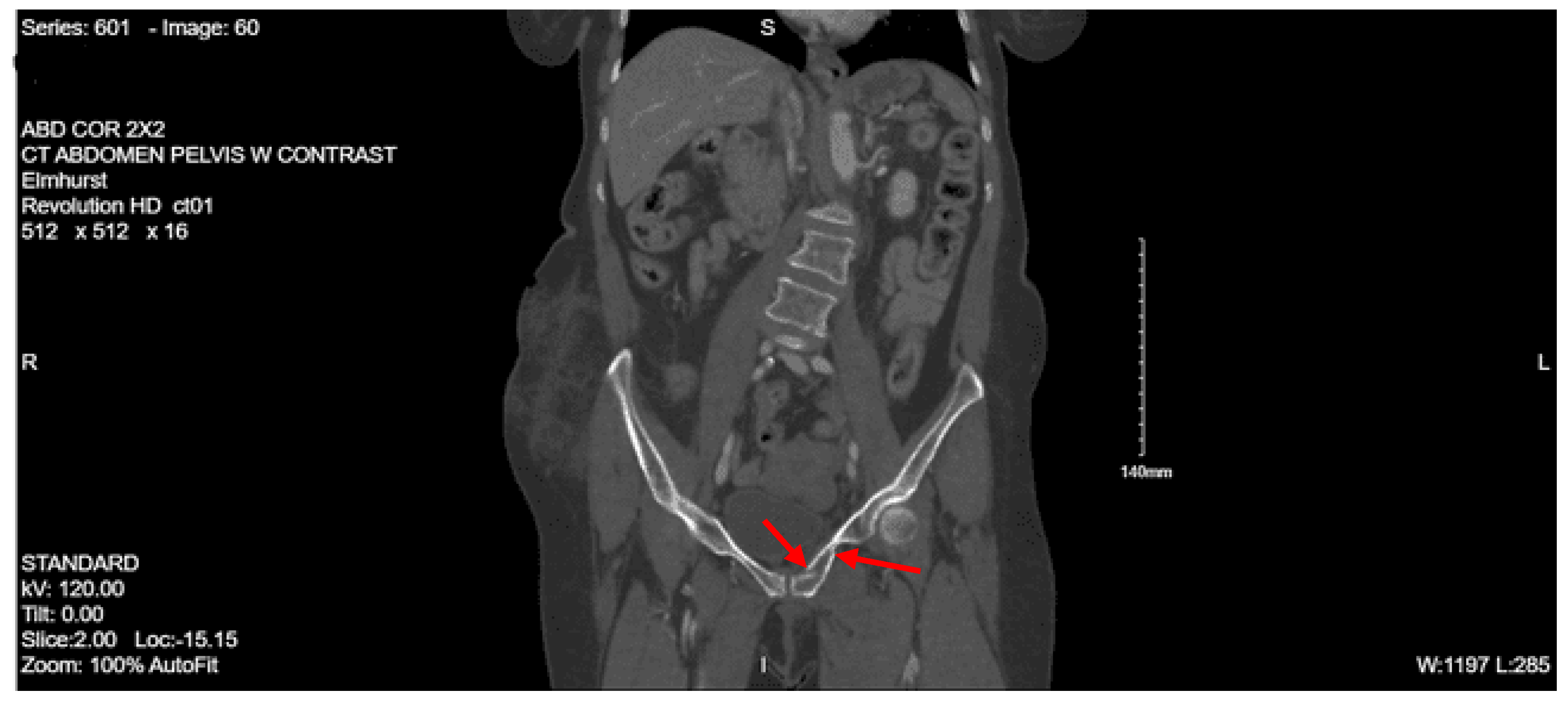

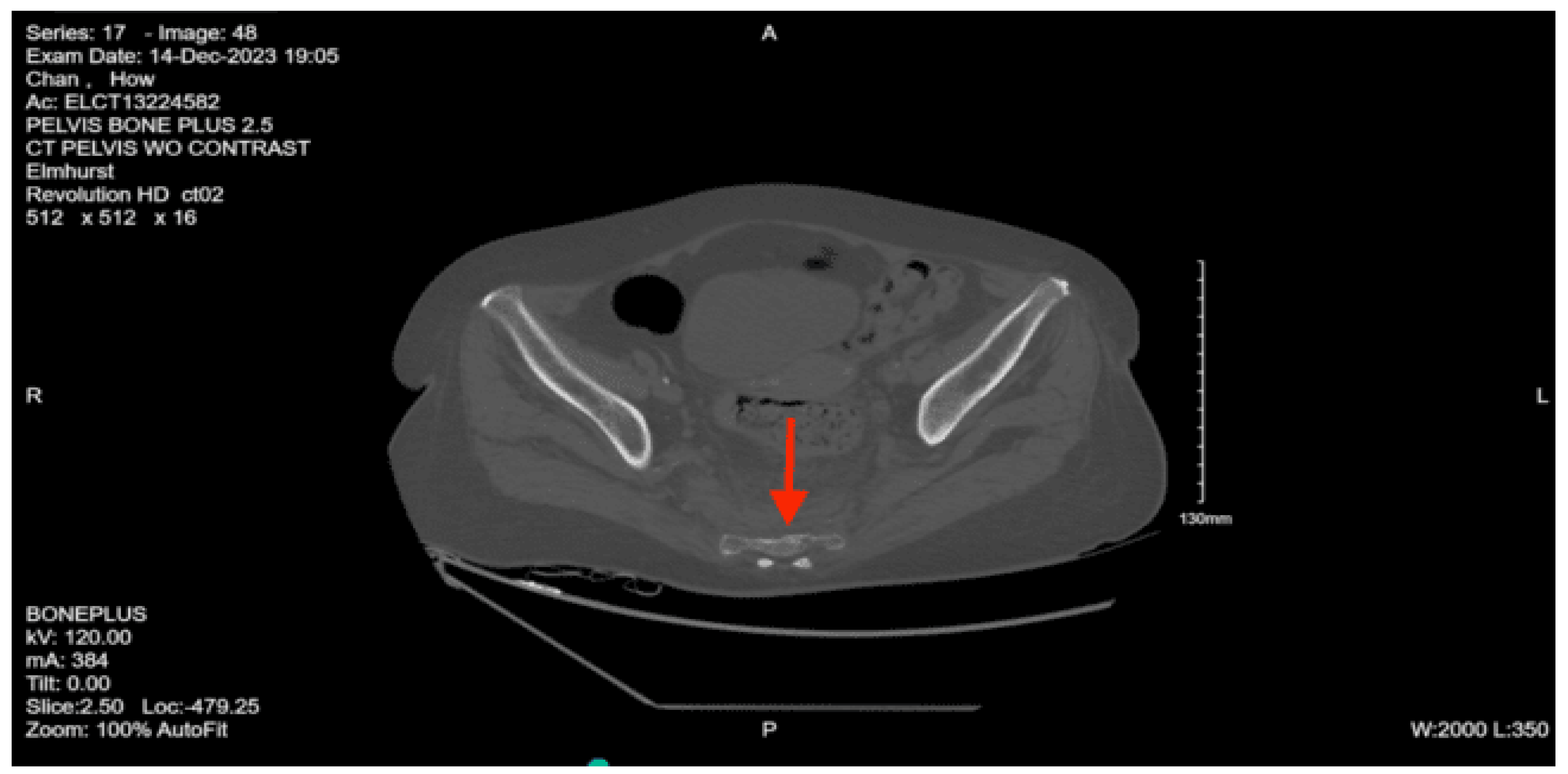

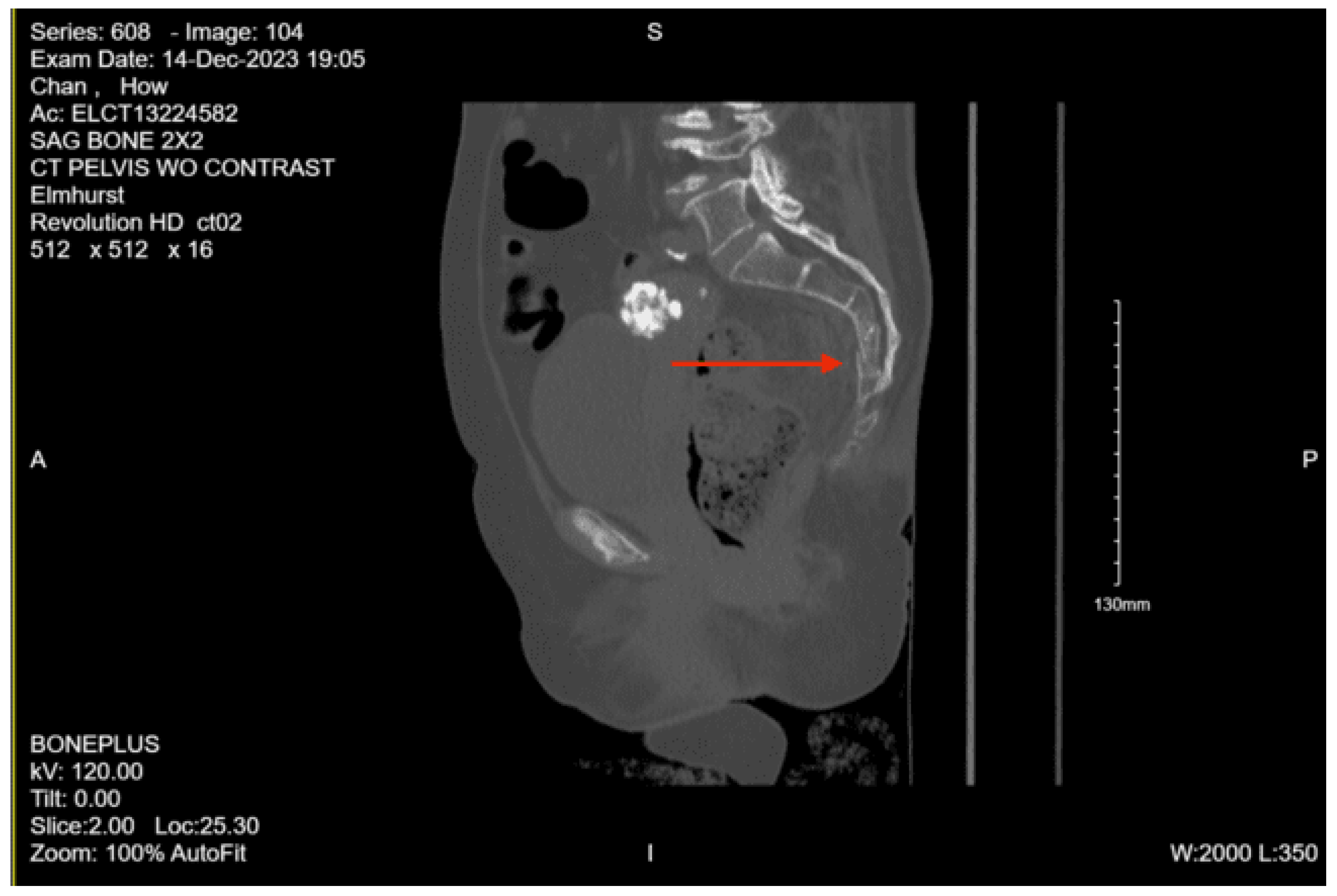

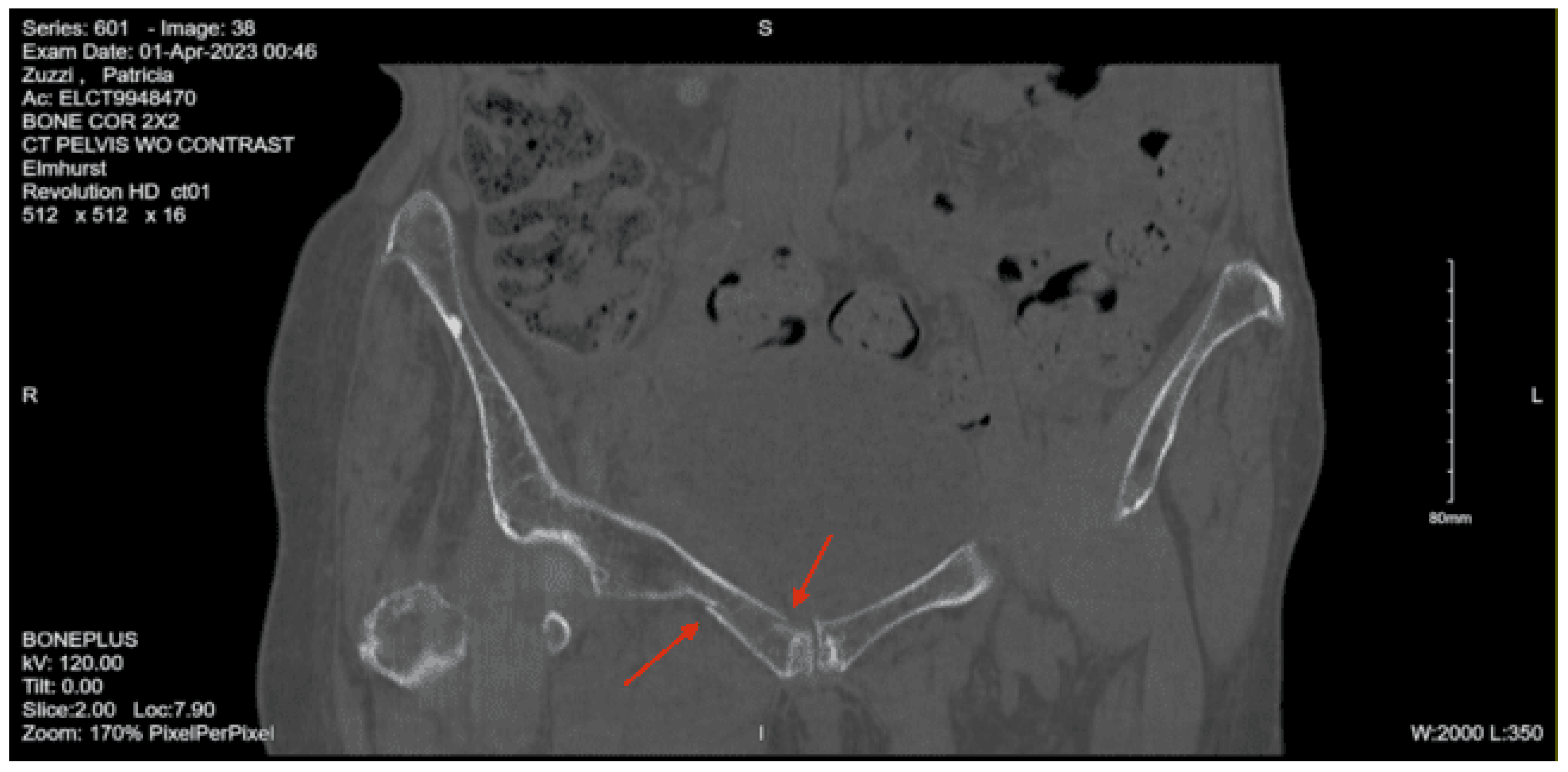

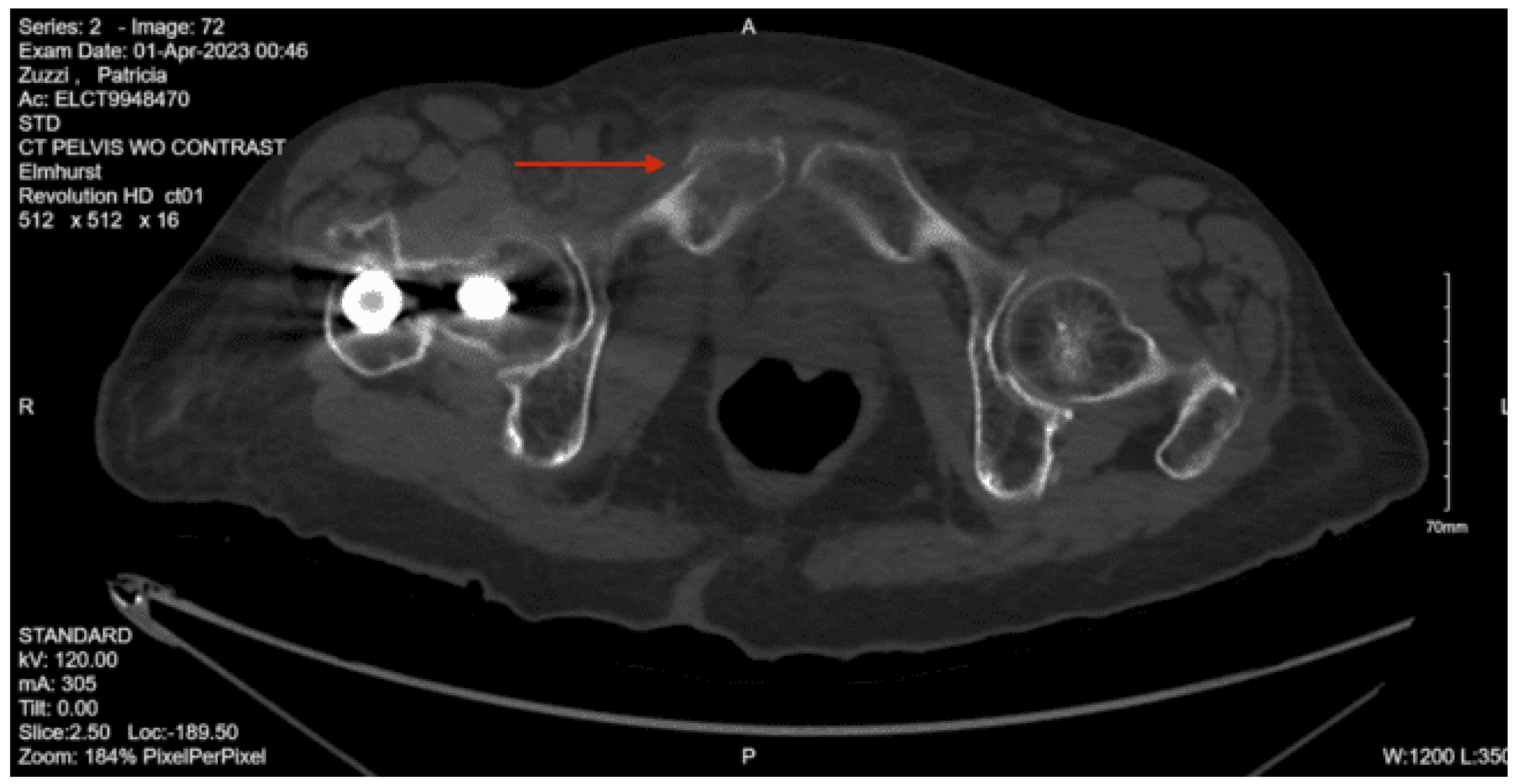

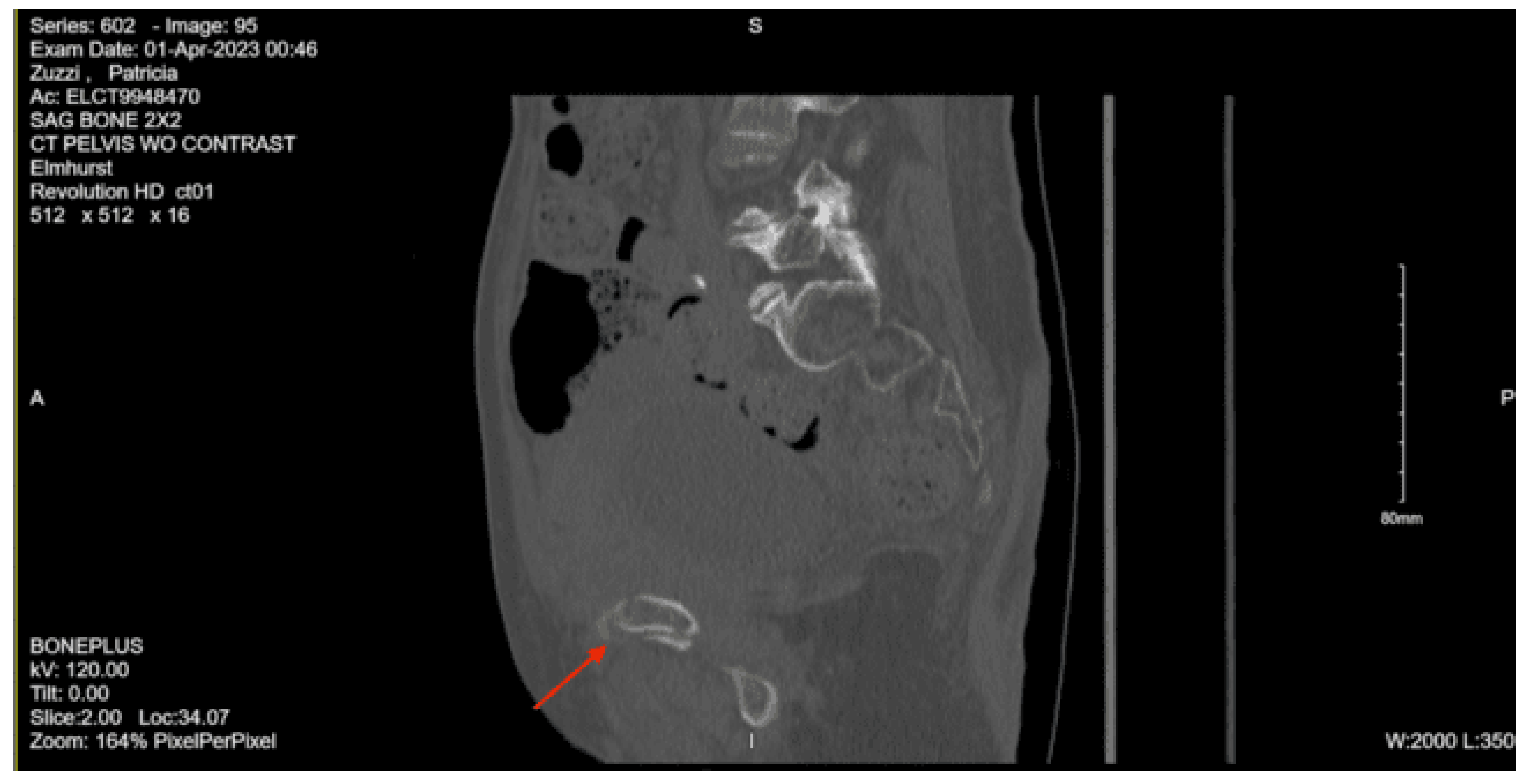

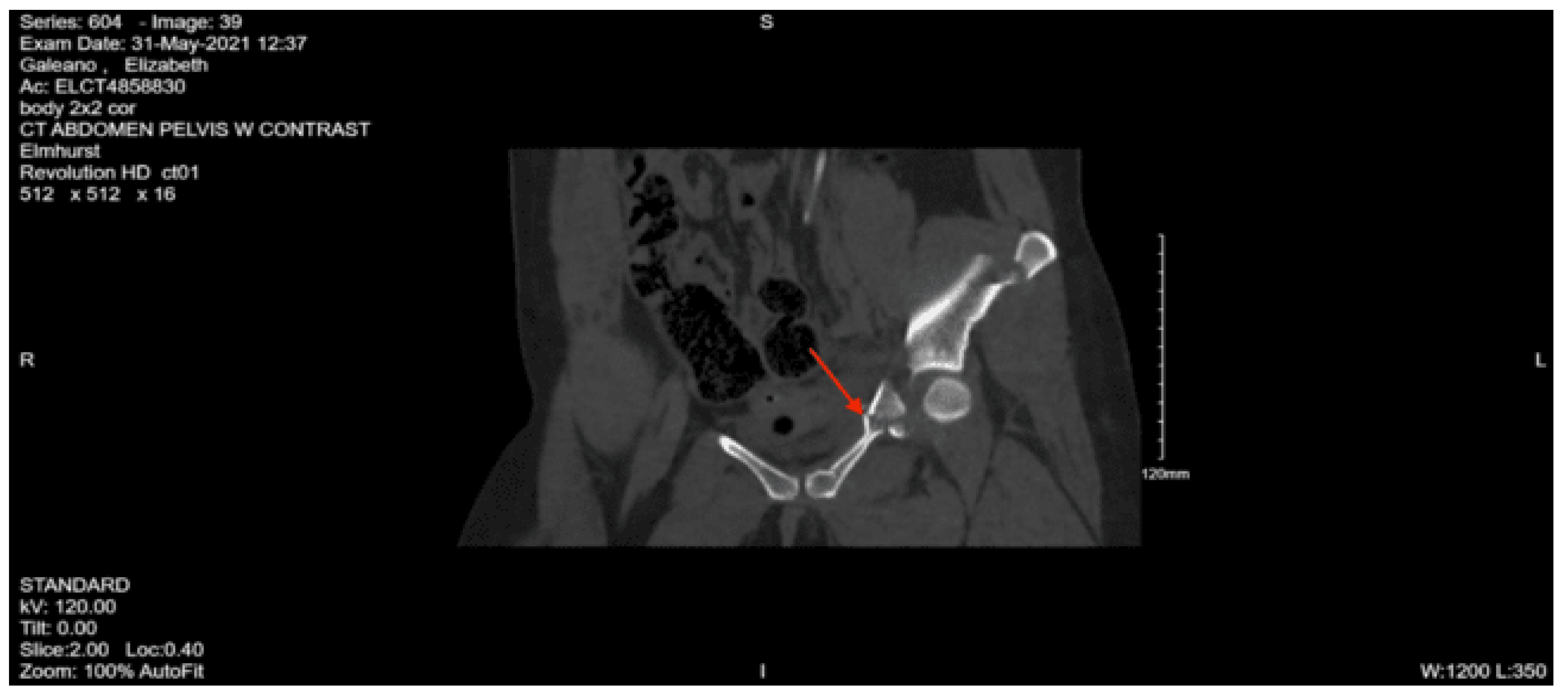

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: Acute nondisplaced bilateral sacral alar fractures with extension into the sacroiliac joint on the right and probable involvement of the right S3 neural foramen. Amorphous hematoma in the medial left gluteal musculature and subcutaneous fat measuring approximately 3.3 x 6.6 x 7.7 cm. No visceral organ injury.

On initial arrival, his GCS was 14 but declined to 11 (M5 V2 E4) throughout the trauma survey. The patient was then found to have a left blow pupil and was immediately brought in for a CT scan due to concern for intracranial bleeding, and neurosurgery was consulted. While in the CT scanner, the patient had a decline in GCS to 8. The CT head non-con showed a traumatic brain injury, showing significant intracranial bleeding. He was given 5mg of labetalol and, per neurosurgery recommendations, was ordered for Kcentra. A clevidipine drip was started, and he was given hypertonic saline, given the concern for raised intracranial pressure. He was given Keppra and tranexamic acid. The medical team shared the information with the family, and the family, including the next of kin, his wife, chose to pursue medical management and forego surgical intervention and against endotracheal intubation.

The patient was admitted to the surgical ICU for monitoring of his intracranial bleed with associated right midline shift and left uncal herniation. The patient was made DNR/DNI by the family. He was initially in the SICU but was then downgraded to the step-down unit for continued comfort care with no aggressive care, including blood draws. Palliative care was consulted. The patient was pronounced dead on hospital day 6.

Case 7

A 52-year-old male with an unknown past medical history was brought in by EMS after being found down at Rikers at the bottom of many steps with an unknown note written in Chinese, presumed to be a possible suicide attempt. When the paramedics arrived, they reported that the patient’s GCS was 3, and they had difficulty intubating the patient in the field. On arrival to the emergency department, the patient was breathing spontaneously but was assisted with a BVM. He was unresponsive upon arrival and unable to provide any history. On arrival, his vitals were Temp 36.4, HR 135, BP 85/62, RR 16, SpO2 96%. On primary evaluation, the patient was unable to protect his airway, so he was intubated. He had no tracheal deviation, and post-intubation had equal breath sounds with good chest excursion bilaterally. He had a non-rapid, non-thready pulse and no active external hemorrhage. His initial GCS was 3 with nonreactive pupils and was not withdrawing to noxious stimuli. On exposure, he had an obvious right lower extremity deformity. On the secondary survey, the patient had an abrasion and hematoma on the right side of the head. Had no hemotympanum, no blood in the nares, and no nasal septal hematoma. The neck had no visible injuries. The chest had no visible injuries and no bony instability. The abdomen was soft and flat, with no visible injuries. His pelvis was stable to compression and had no visible injuries. The right lower extremity had an obvious femur deformity, and the right thigh compartment was larger than the left. He had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses. His E-FAST was negative.

Portable chest XR: No evidence of active chest disease

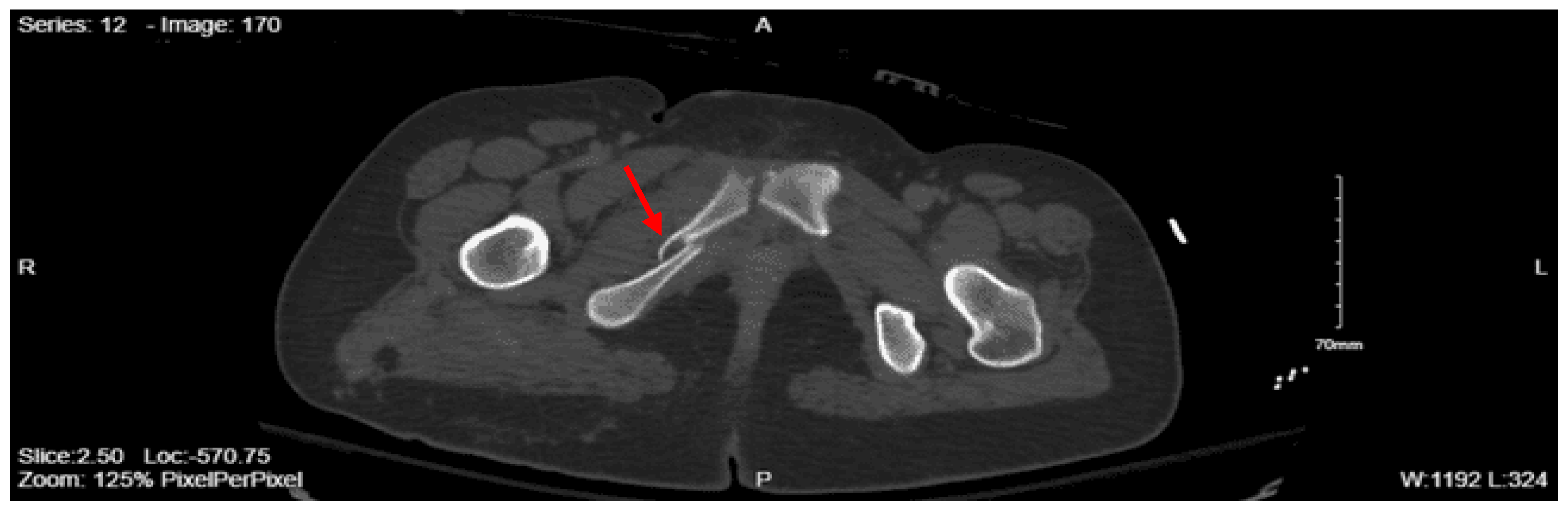

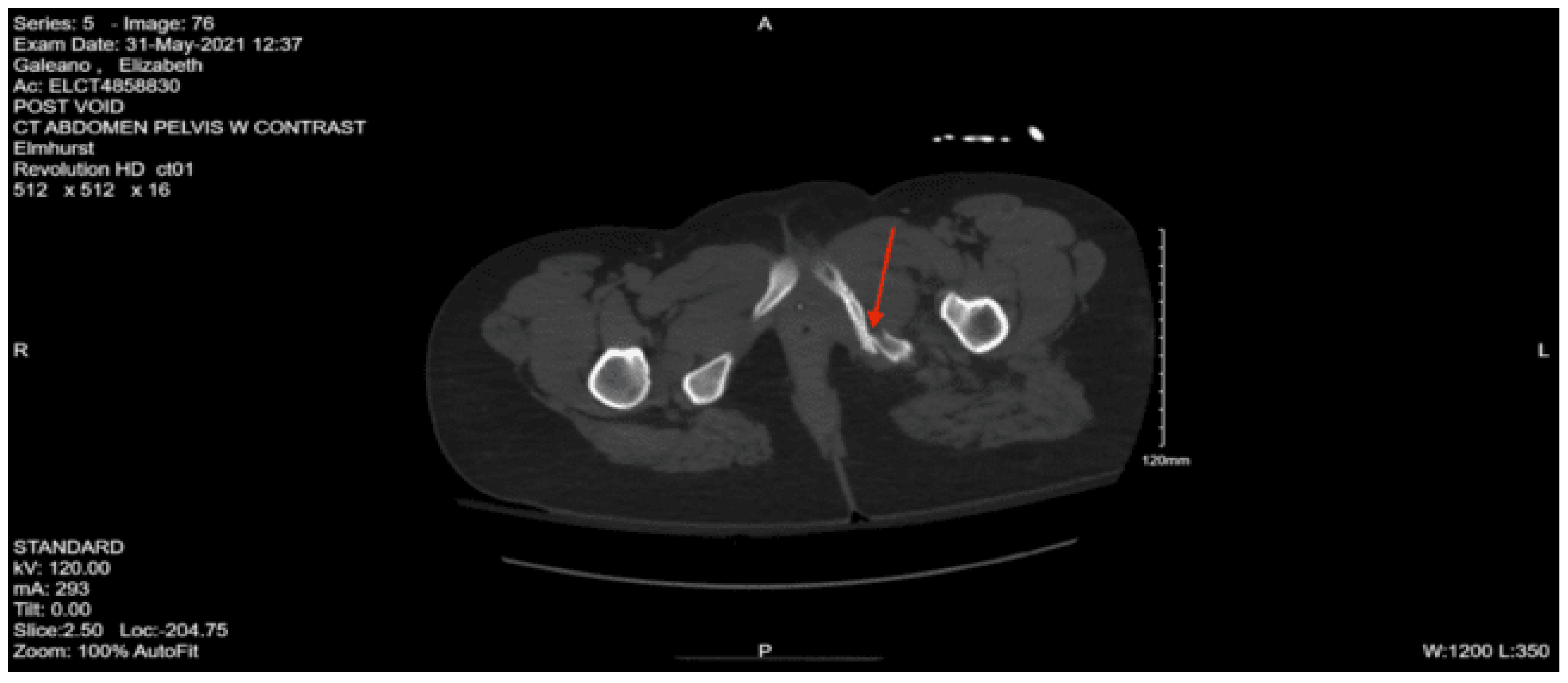

Portable Pelvic XR: Mildly displaced comminuted subtrochanteric fracture of the right proximal femur

CT head non-contrast: Extensive diffuse subarachnoid hemorrhage, bifrontal and bilateral parietal small subdural hematomas, and bilateral small supratentorial subdural hematomas. Mild intraventricular hemorrhage in the right posterior horn. Nondepressed fracture of the right frontal parietal calvarium.

CT cervical spine non-contrast: Unremarkable. No acute fractures.

CT Angio Neck with contrast: Right ICA dissection with occlusion at the skull base

CT chest with contrast: Right lower lobe consolidation/atelectasis. Otherwise no evidence of acute intrathoracic injury.

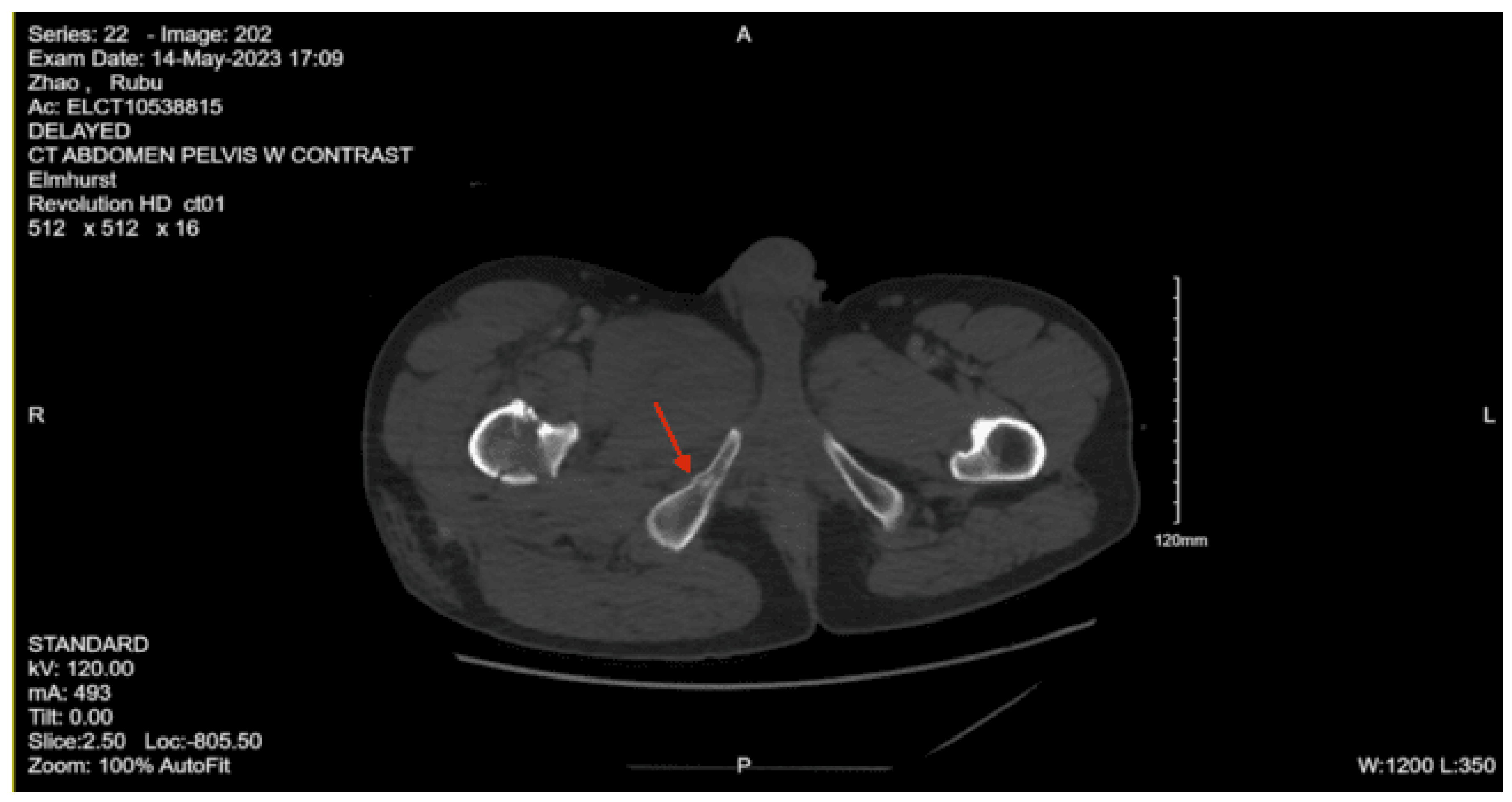

CT Abdomen Pelvic with contrast: No evidence of acute visceral injury. Redemonstration of fractures of the proximal right femur. Fractures of the right inferior petrous and right transverse processes of L2 and L3.

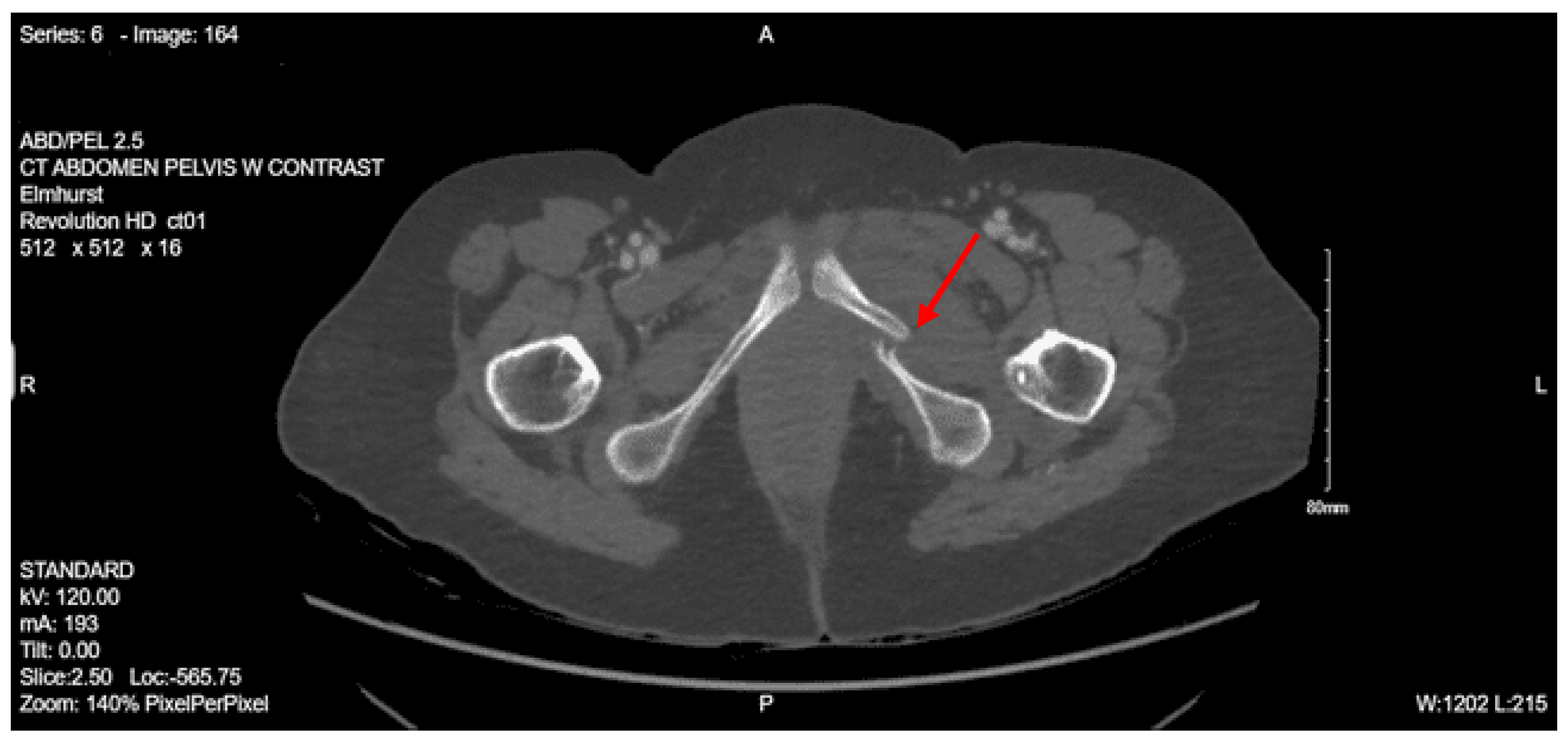

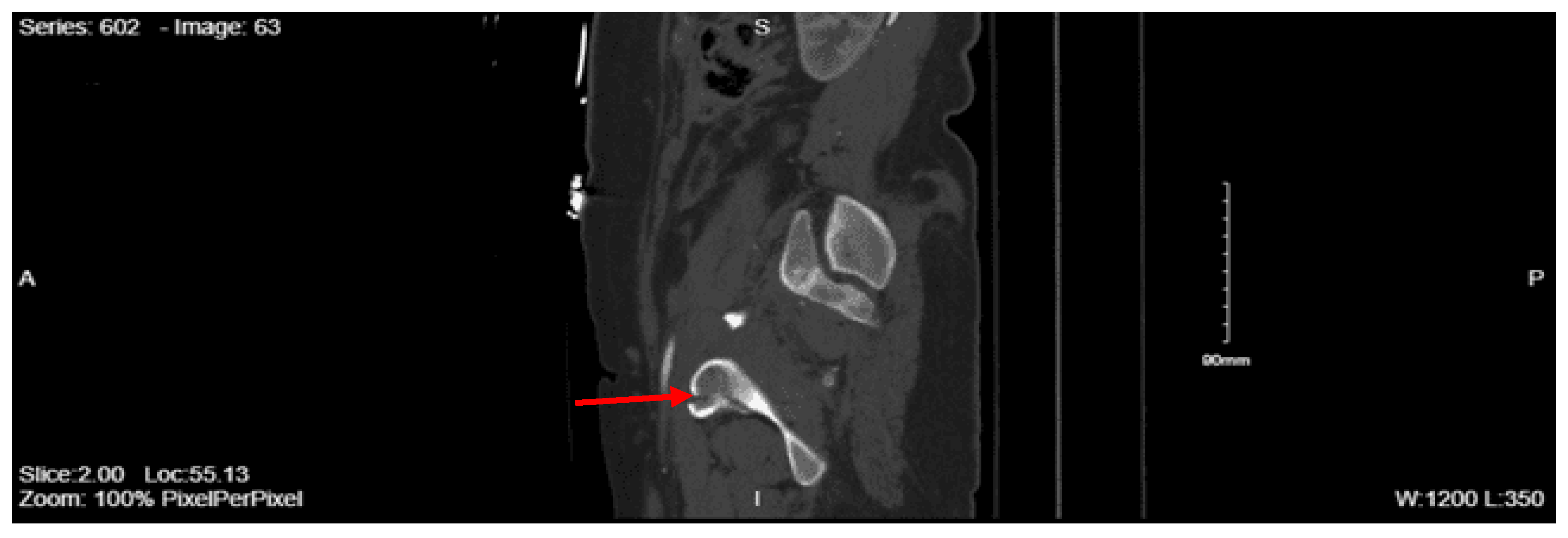

CT femur w/o contrast, Right: Comminuted fracture of the proximal subtrochanteric right femur with posterior medial displacement. Nondisplaced fracture of the right inferior pubic ramus.

Given his hypotension and injuries, the patient was started on a massive transfusion protocol and was given a total of 4 units of packed red blood cells, 2 units of platelets, and 1 unit of fresh frozen plasma. The orthopedic surgery team was consulted due to the right hip fracture, and a traction pin was placed to stabilize the fracture. After imaging, the patient was expediently transported to the surgical/trauma ICU (STICU). Neurosurgery was consulted and diagnosed the patient with diffuse anoxic-hypoxic brain injury with resulting diffuse global edema, loss of the majority of intracranial blood flow, and irreversible ischemic changes and injury as evidenced by the diffuse loss of grew-white differentiation. Despite intervention, they stated that this portends a negligible chance of a meaningful neurological recovery. They recommended no aggressive treatment beyond supportive care.

On arrival to the STICU, his blood pressure was in the 70s systolic. He was given a fluid bolus and started on a phenylephrine drip. The patient continued to decline, so a second vasopressor drip was added to maintain an adequate MAP. While in the SICU, the patient had dusky limbs and had barely reactive pupils, as the only brainstem reflex. The patient’s clinical condition continued to worsen, requiring increased doses of vasopressors. On hospital day 2, the patient had been off sedation, and 4/4 train of four testing, the neurological exam was still GCS 3T. The patient then proceeded to be optimized medically for brain death testing and, the following day, was declared brain dead.

Case 8

An 85-year-old female with a past medical history of Parkinson’s, orthostatic hypotension, and right greater trochanteric fracture status post open reduction, internal fixation on 10/2021, presented to the ED after a mechanical fall at home. The patient reportedly fell onto her right side, hitting her right shoulder, wrist, hip, ankle, and right side of her head. She denied any use of anticoagulants and did not have any loss of consciousness. On arrival, her vital signs were BP 124/53, pulse 66, temperature 36.5 °C, RR 18, SpO2 96% on room air. On primary evaluation, the patient had an intact airway and was able to protect it. She had bilateral breath sounds, was hemodynamically stable, and had palpable distal pulses in all four extremities. Her GCS was 15. On secondary evaluation, she was in no acute distress. She had a right lateral forehead laceration that was sutured by the ER staff. She had normal work of breathing and no chest wall deformity or tenderness to palpation. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender. She had a stable pelvis, and her cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spines were non-tender, without any palpable step-offs.

Portable Pelvis XR: Intact pelvis

CT head non-contrast: Acute subdural hemorrhage over the right cerebral hemisphere measuring up to 12 mm in thickness. There is a mass effect on the right lateral ventricle with a midline shift to the left of approximately 6mm.

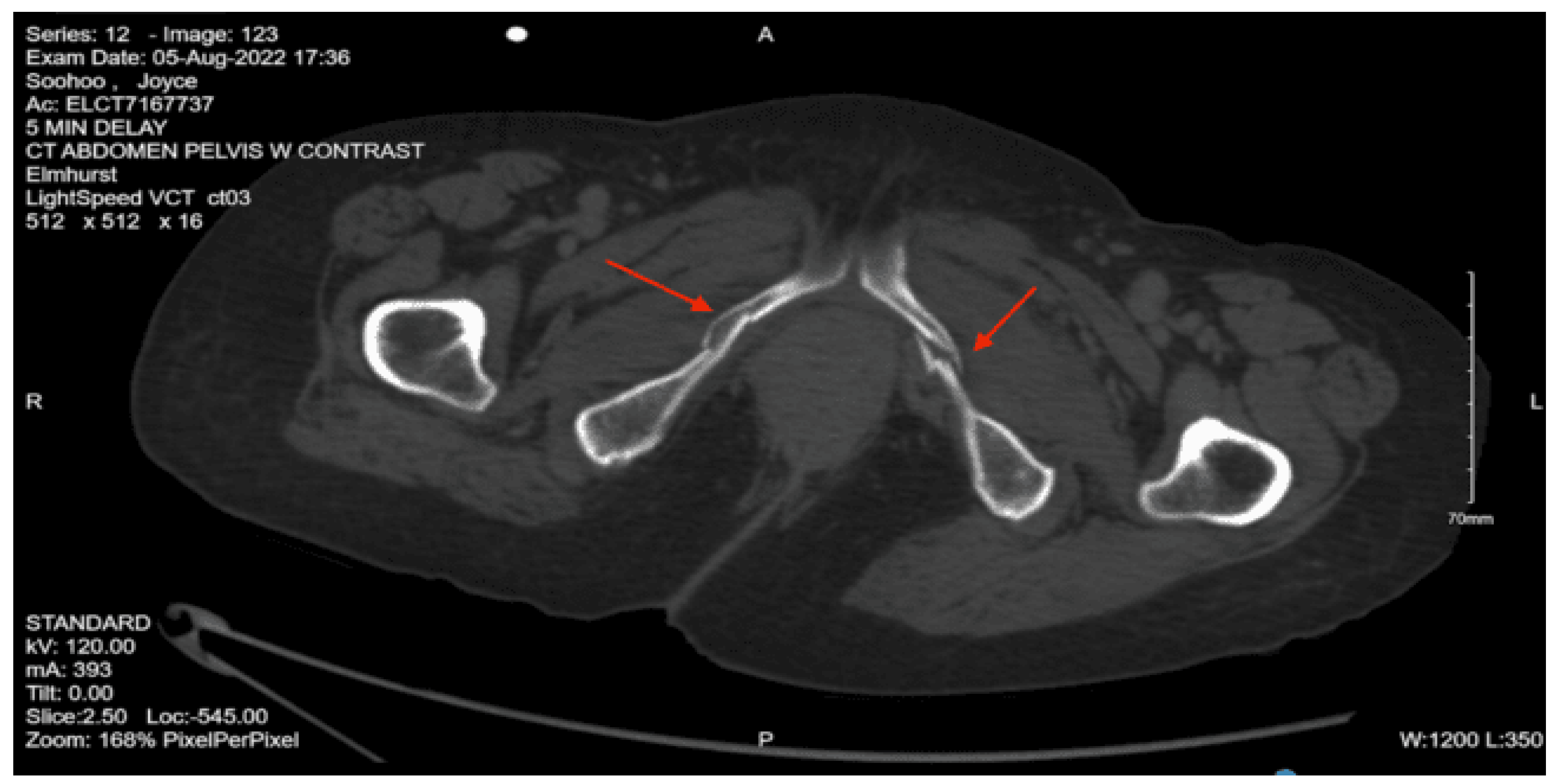

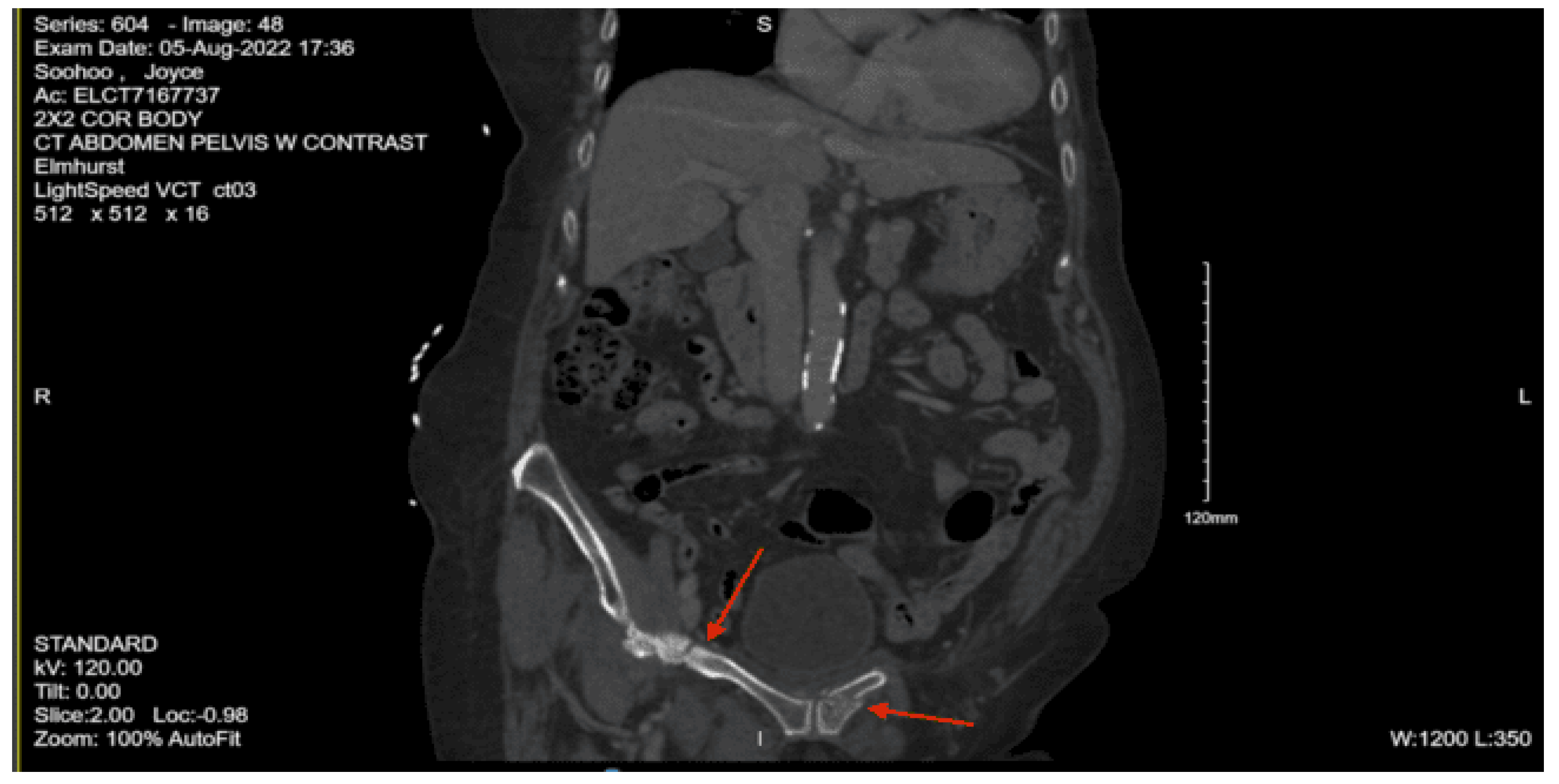

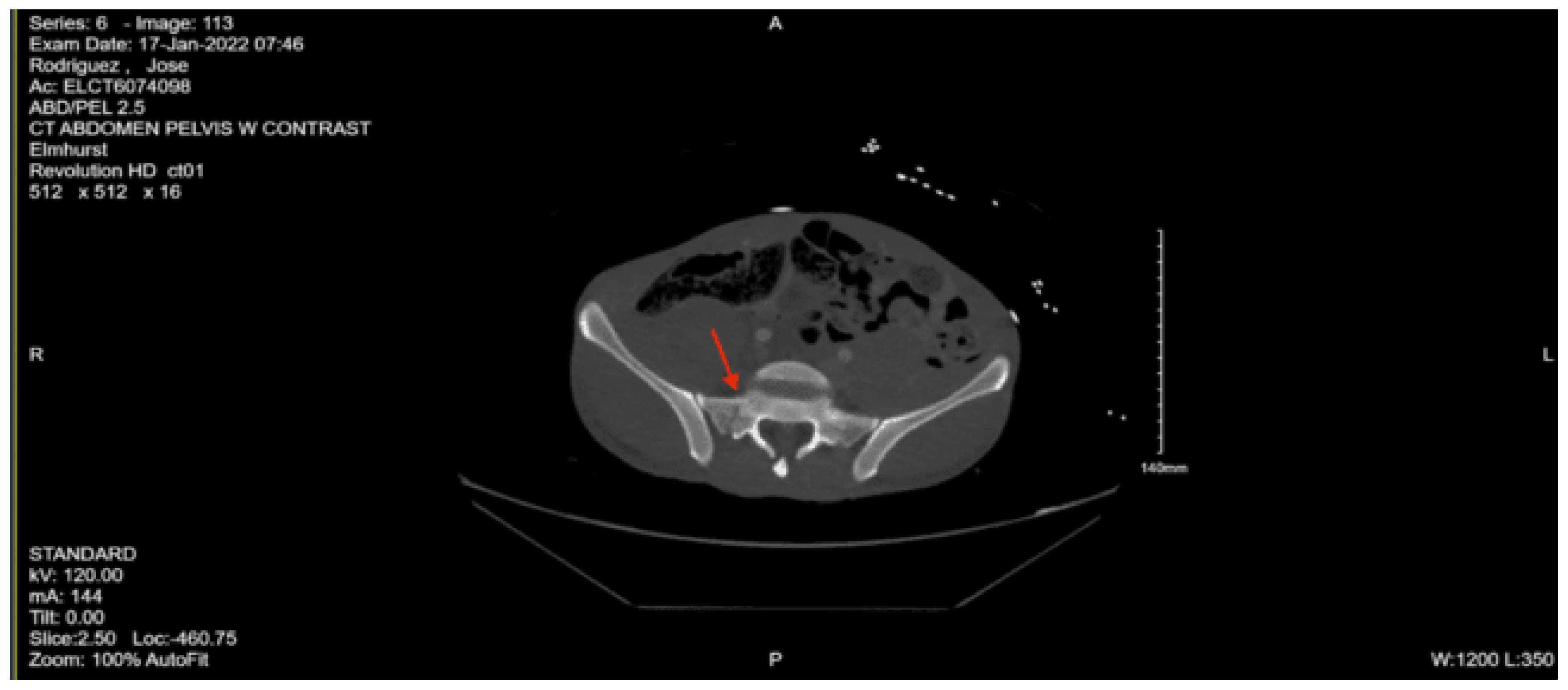

CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast: The lumbar spine demonstrates mild degenerative changes at multiple levels. Acute fracture of the superior and inferior pubic rami on the right with associated hematoma. Question: Fracture of the right sacral ala. Infiltrative changes were noted within the right middle lobe. Moderate dilatation of the common bile duct is present. Punctate calcifications are present within the left kidney without obstructive uropathy. There is mild bladder wall thickening consistent with incomplete distention, chronic outflow obstruction, or cystitis. A large amount of stool is present throughout the colon.

CT pelvis non-con: Acute fracture of the right superior and inferior pubic rami with extension through the pubic tubercle in with a small amount of extraperitoneal hemorrhage dissecting through the fascial planes of the anterior pelvis. Question: age-indeterminate fracture of the right sacral ala.

Neurosurgery was consulted, and they recommended starting Keppra, a goal systolic blood pressure of less than 160, and repeat CT head in 6 hours. They stated that there were no acute neurosurgical interventions. Orthopedic surgery was consulted and recommended that the patient bear weight as tolerated on bilateral lower extremities and stated that there was no plan for any surgical interventions. The patient was admitted to the STICU for management of her traumatic injuries. The speech and swallow team was consulted, given the patient’s baseline dysphagia secondary to her Parkinson’s and subdural hemorrhage, and recommended a diet and aspiration precautions. On hospital day 4, the patient was noted to have worsening hyponatremia and was started on 3% NaCl and salt tabs with appropriate response. Physical and occupational therapy were consulted, and it was recommended that, when medically stable, the patient should be discharged to an acute rehab facility. On hospital day 6, the patient was transferred out of the STICU. The speech and swallow team recommended that the patient obtain a modified barium swallow study, which showed frank aspiration, and the patient was also noted to have an increasing white blood cell count, so she was made NPO, given the concern for aspiration pneumonia. A goals of care conversation was had with the patient, given her increased risk for aspiration, and she was recommended to have a G-tube placed, but the patient refused and was placed back on an oral diet, which she tolerated well. On hospital day 13, the patient was noted to have an increase in her white blood cell count and was afebrile and asymptomatic. She had a urinalysis that was positive for nitrites and leukocytes, so she was started on Bactrim with an interval improvement in her white blood cell count. On hospital day 14, the patient was medically optimized and was safely discharged to acute rehab.

Case 9

An 86-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, prior left breast cancer status post left mastectomy, presented to the ED via EMS after getting hit by a car and subsequently landing on her right side. She reports hitting her head and loss of consciousness. On arrival to the ED, the patient was complaining of lower back pain, bilateral hip pain, and dizziness. On arrival, her vital signs were Temp 36.7, Pulse 98, BP 122/80, RR 19, SpO2 97%. On the primary survey, the airway had no airway-threatening fractures or foreign bodies, blood, or secretions. She had no tracheal deviation. She had equal breath sounds with symmetric chest excursion. There were no obvious chest wall defects. She had a normal level of consciousness. She had a non-rapid, non-thready pulse. Her GCS was 15, and she followed commands. On the secondary survey, her pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. There was no hemotympanum or blood in the nares. A hematoma was palpated at the left occiput. Her neck had no visible injuries, and her trachea was midline. Her chest had no visible injuries and no bony instability. Her abdomen was soft and flat, with no visible injuries. Her pelvis was stable to compression and had no visible injuries. She had a visible right thigh contusion that appeared old. On examination of her back, she was tender to palpation of the midline lumbar and sacral spine. There were no step-offs or deformities noted. Her E-FAST was negative for any pericardial effusion, pneumothorax, thoracic fluid, or intraperitoneal fluid.

Portable chest X-ray: No pneumothorax. No pleural effusion. Osteopenia and degenerative changes of the dorsal spine.

Portable pelvis X-ray: Degenerative changes about both hips. Probable subcapital fracture of the right hip. Marked concentric narrowing of the joint space of the right hip. Osteopenia.

CT head non-contrast: Large left posterior parietal subcutaneous hematoma. Small right temporal contusion with hemorrhage

CT cervical spine, non-contrast: Narrowing of the joint space of C3-4 and slight anterolisthesis of C6 on C7

CT chest with contrast: Grossly normal CT chest

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: Grossly intact abdominal and pelvic viscera with acute fracture of the left superior pubic ramus near the symphysis and the bilateral inferior pubic rami.

CT lumbar spine without contrast: Diffuse osteopenia of the lumbar spine with suggestion of a fracture involving the anterior aspect of the vertebral body of L5 in its superior portion and acute fracture of the anterior aspect involving the lateral mass of S1

The patient then had a repeat CT head non-contrast, given the initial finding as a recommendation from neurosurgery. The repeat CT head showed an enlarging intraparenchymal bleed within the right temporal lobe with mass effect and effacement of the sulci within the right temporal lobe, surrounded by vasogenic edema. She was also found to have an enlarging right parietal subdural bleed and small foci of subarachnoid blood within the medial portion of the right occipital lobe. The patient was subsequently admitted to the STICU for further management of her traumatic injuries. For the neurosurgical injuries, they recommended systolic blood pressure parameters of 90-140 mmHg, administering tranexamic acid and Keppra, and repeat CT head non-contrast for interval scan. The orthopedic surgery team recommended that the patient bear weight as tolerated and recommended additional images: pelvis inlet/outlet. On repeat CT head, it was shown that the patient had a slight interval enlargement of the right temporal intraparenchymal hemorrhage, so they continued to recommend close neuro monitoring and tight control of her systolic blood pressure, sodium, platelets, hemoglobin, INR, and glucose.

She was then downgraded to the surgical step-down unit on hospital day two. On her third hospital day, she had another repeat CT head that demonstrated stability, so she was started on Lovenox for DVT prophylaxis. On her fourth hospital day, the physical medicine and rehabilitation team was consulted and recommended starting physical and occupational therapy. She then had her follow-up pelvic X-rays, which showed stability, so the orthopedic surgery team recommended no further orthopedic interventions. The patient was eventually downgraded to the floor and was evaluated by physical and occupational therapists, who recommended that the patient be discharged to an acute rehab facility. The patient was deemed medically optimized on her seventh hospital day, so she was safely discharged to an acute rehab facility.

Case 10

A 33-year-old male with a past medical history of schizophrenia and opioid use disorder was BIBEMS after a fall from a subway overpass. He had an initial finger stick glucose of 25, so he was immediately given an ampule of D50. On arrival, his vital signs were Temp 36.5, BP 106/83, Pulse 96, RR 12, SPO2 100%. On the primary survey, the patient’s airway was patent and self-maintained. His chest was clear to auscultation bilaterally with good chest wall excursion. He had bilateral distal pulses on the upper and lower extremities. No gross bleeding was appreciated. The patient was moving all extremities spontaneously with a GCS of 13. On the secondary survey, the patient was noted to have inappropriate affect. His left pupil was minimally reactive to light, but his extraocular movements were intact. His chest had an abrasion to the mid-chest but no visible deformity. His abdomen was soft and non-tender. A right knee effusion was noted. On examination of his back, he had multiple abrasions on his right flank and upper back, with associated lumbar spine midline tenderness to palpation. His E-FAST was negative.

Portable chest X-ray: Consolidation within the medial aspect of the right lung base. This could reflect pulmonary contusion given acute fractures involving the posterior 9th through 12th ribs.

Portable Pelvic X-ray: No acute findings

CT head contrast: no acute intracranial findings

CT cervical spine non-contrast: Tiny right greater than left apical pneumothoraces. Chronic fracture involving the C7 spinous process, no acute fractures identified.

CT chest with contrast: Right greater than left pneumothoraces are again noted, small in size. Small right hemothorax. Mild pneumomediastinum. Patchy consolidation and ground glass opacities involving the right lower lobe and right middle lobe are consistent with patchy pulmonary contusion. Multiple acute rib fractures. Nondisplaced L1 transverse process fracture incompletely imaged. Hemangioma within the T5 vertebral body with age-indeterminate contour deformity of the superior endplate.

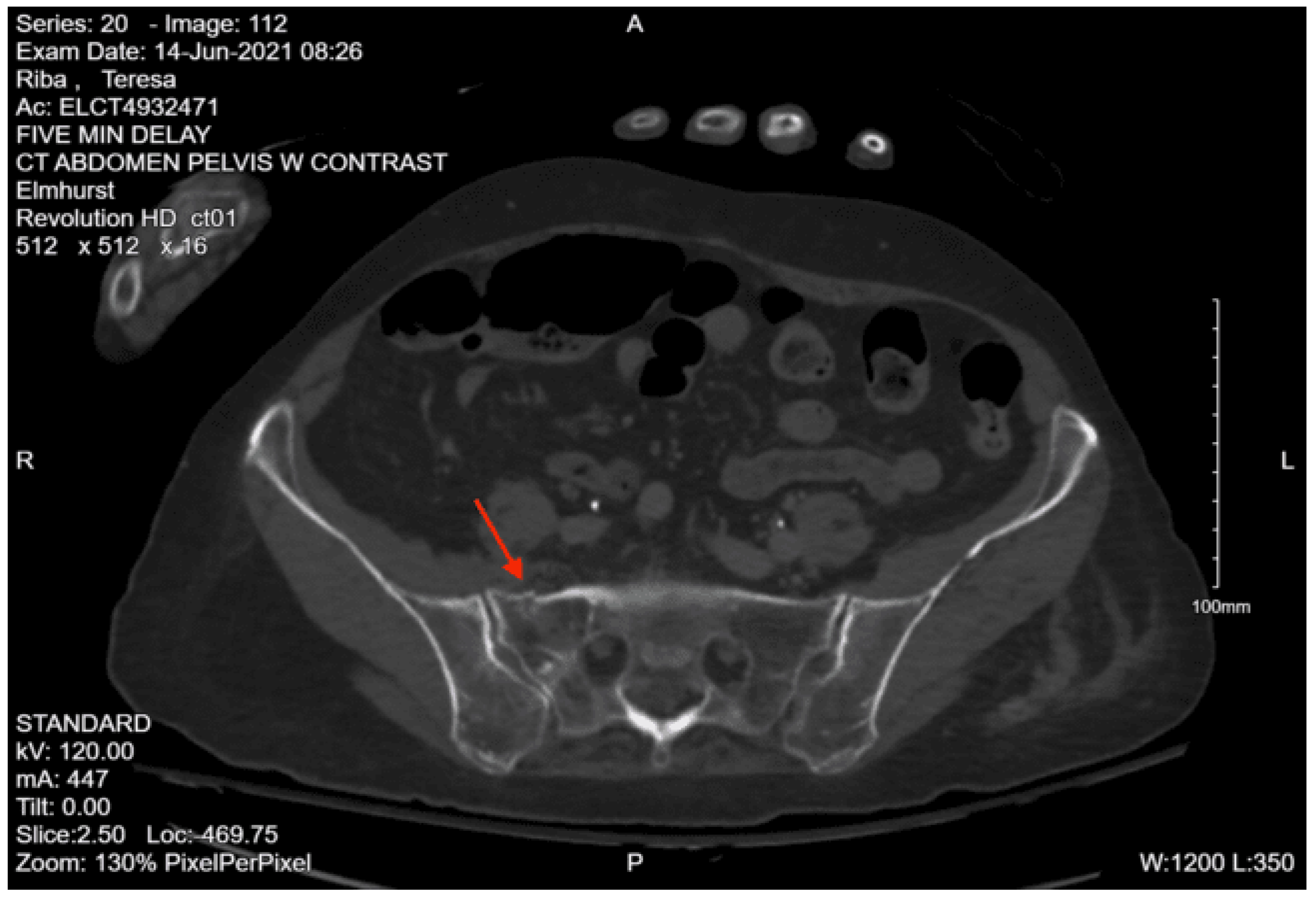

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: There is retroperitoneal fluid surrounding the upper abdominal aorta without contrast blush. Linear flap within the upper abdominal aorta at the level of the celiac and SMA origins, concerning for traumatic injury. Lower thoracic findings include multiple posterolateral right rib fractures. Grade II hepatic injury. Periportal edema. Acute right L1 through L5 transverse process fractures. Acute right sacral ala fracture. Nondisplaced acute right inferior pubic ramus fracture. Nondisplaced acute fracture involving the lateral aspect of the right acetabulum.

Since the patient was found to have pneumothoraces and hemothorax, a right chest tube was inserted by the ED staff and connected to suction. Given the finding of suspected aortic injury from the CT abdomen pelvis with contrast, a CT angiography of the abdomen pelvis was performed, which showed no evidence of vascular abnormality. Pre-contrast imaging demonstrated a heterogeneous enhancement with persistent spotty nephrogram involving areas of the right kidney, which raised a concern for a renal contusion. The patient was admitted to the STICU for continued management of his traumatic injuries. Neurosurgery was consulted for the lumbar spine fractures and the sacral ala fracture. They recommended no acute surgical interventions and advocated for optimal pain control. Orthopedic surgery was consulted for the right sacral ala fracture and the lateral right acetabulum fracture, and recommended no orthopedic intervention at the time and no weight-bearing activity status. Psychiatry was consulted, given his history of psychiatric disease, and they recommended a two-to-one level of observation for unpredictable behavior, holding his standing home medications, and gave recommendations for agitation management.

On hospital day one, the patient was evaluated by psychiatry again, and they were concerned that his injury could have been a suicide attempt, so they changed the level of observation to one-to-one. They also recommended adding buspirone orally twice a day. Urology was consulted, given the concern for the right renal contusion, and they stated that, given the patient had a stable creatinine and no hydronephrosis or other gross abnormalities, no intervention was recommended. The physical medicine and rehabilitation team was consulted and recommended that the patient start physical and occupational therapy. The patient was downgraded from the STICU to the surgical step-down unit on hospital day two. On hospital day three, the addiction medicine team was consulted, given his history of polysubstance use, and they recommended starting him on suboxone, which was a medication he was previously on. His right chest tube was removed once the patient was noted to have a chest x-ray with no evidence of pneumothorax. On hospital day four, the physical and occupational therapists evaluated the patient and stated that the patient was likely to progress to baseline functional status rapidly, so they recommended that the patient be given a shower chair and ambulation device once the patient was medically optimized to be discharged. The patient was deemed medically optimized on hospital day 14 and was discharged with crutches to a shelter, with close outpatient follow-up with psychiatry.

Case 11

A 37-year-old male with a past medical history of polysubstance use presented to the ED after a fall from over 25 feet. It was reported that the patient was running away from the police and tried to jump onto a pole to scale down from the 4th floor of a building, but missed and fell, with a reported loss of consciousness. On arrival, his vital signs were pulse 70, BP 140/90, RR 16, SpO2 95%. On primary evaluation, his airway was patent, self-maintained, and speaking. His chest was clear to auscultation bilaterally with good chest wall excursion. He had bilateral distal pulses on his upper and lower extremities, with no gross bleeding noted on exam. He was reported to have a GCS of 15 and was moving his extremities spontaneously, with no gross deficits noted on the exam.

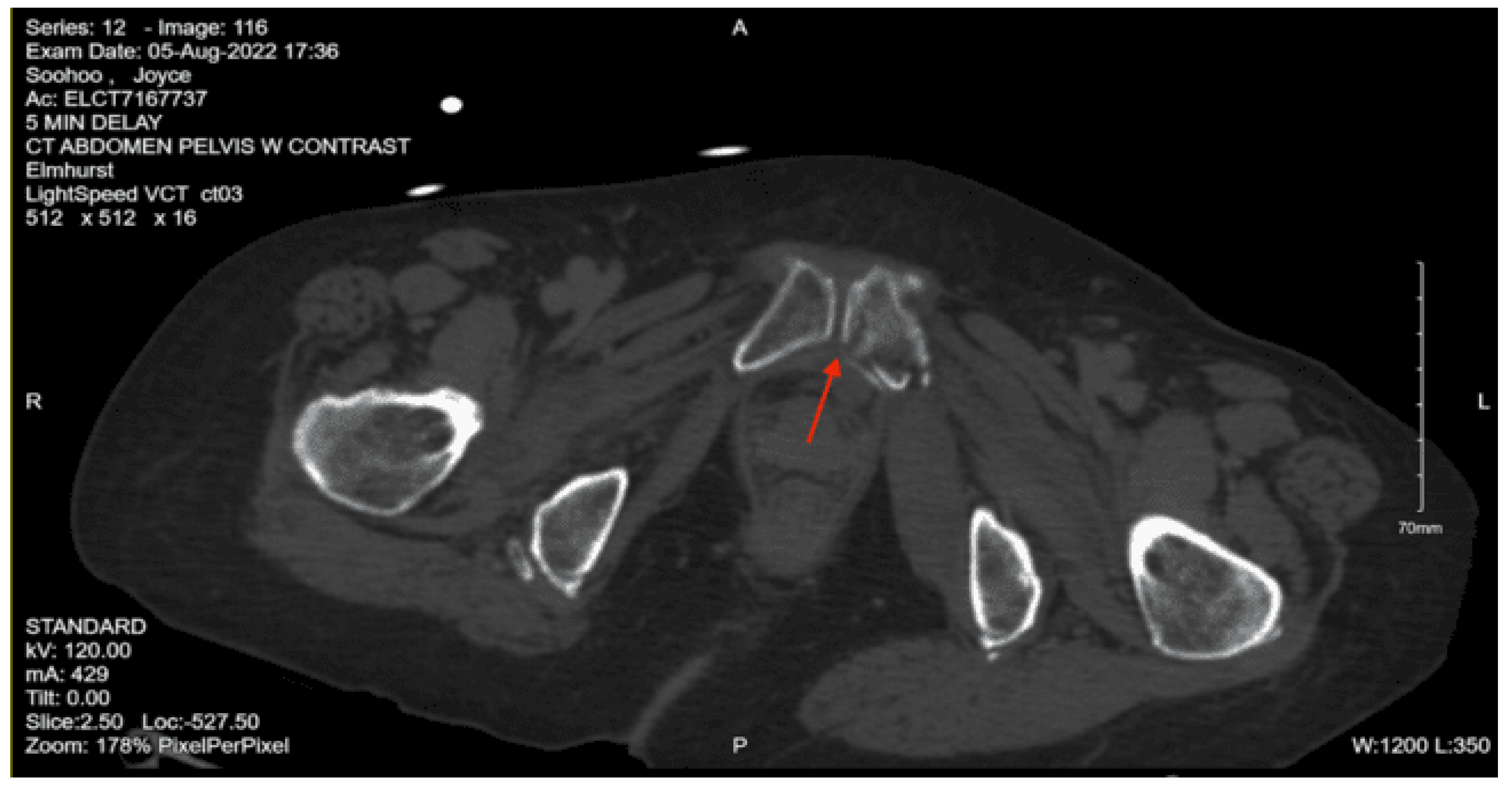

On secondary evaluation, the patient’s pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light. He had left eyelid swelling and ecchymoses. His extraocular movements were intact. The patient had some dried blood in his nares with no nasal septal hematomas. His chest and back had no obvious deformities and were non-tender to palpation. His spine did not have any step-offs or palpable deformities. His abdomen was soft and non-distended but had some suprapubic tenderness to palpation. The patient was moving all four extremities spontaneously. He had ecchymoses to the left elbow and had significant swelling and tenderness to palpation. His left lower extremity was shortened and externally rotated. A left knee abrasion and tenderness to palpation at the left hip and foot were present. His E-FAST was negative, and portable chest and pelvis x-rays were done, which showed multiple pelvic fractures, so a pelvis binder was placed.

Portable chest x-ray: no traumatic findings.

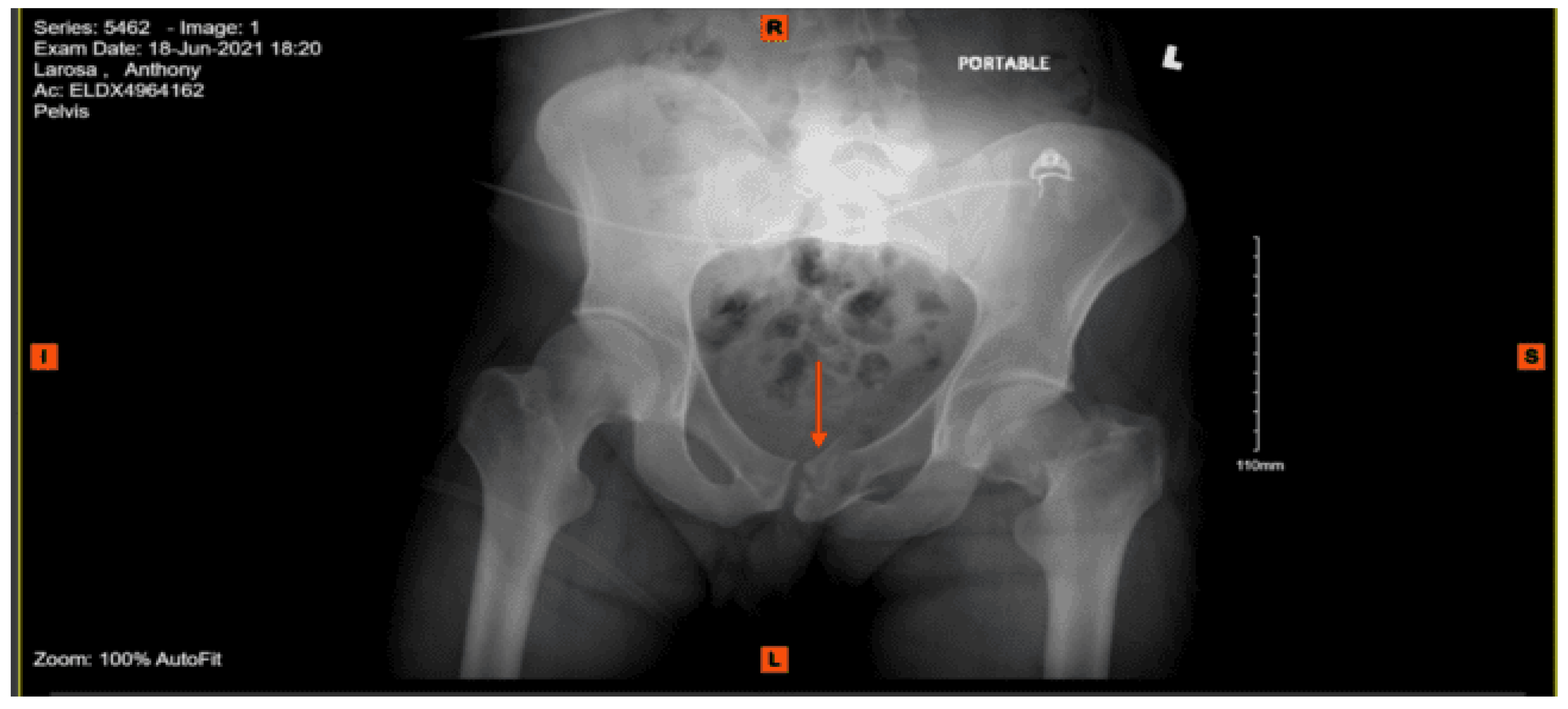

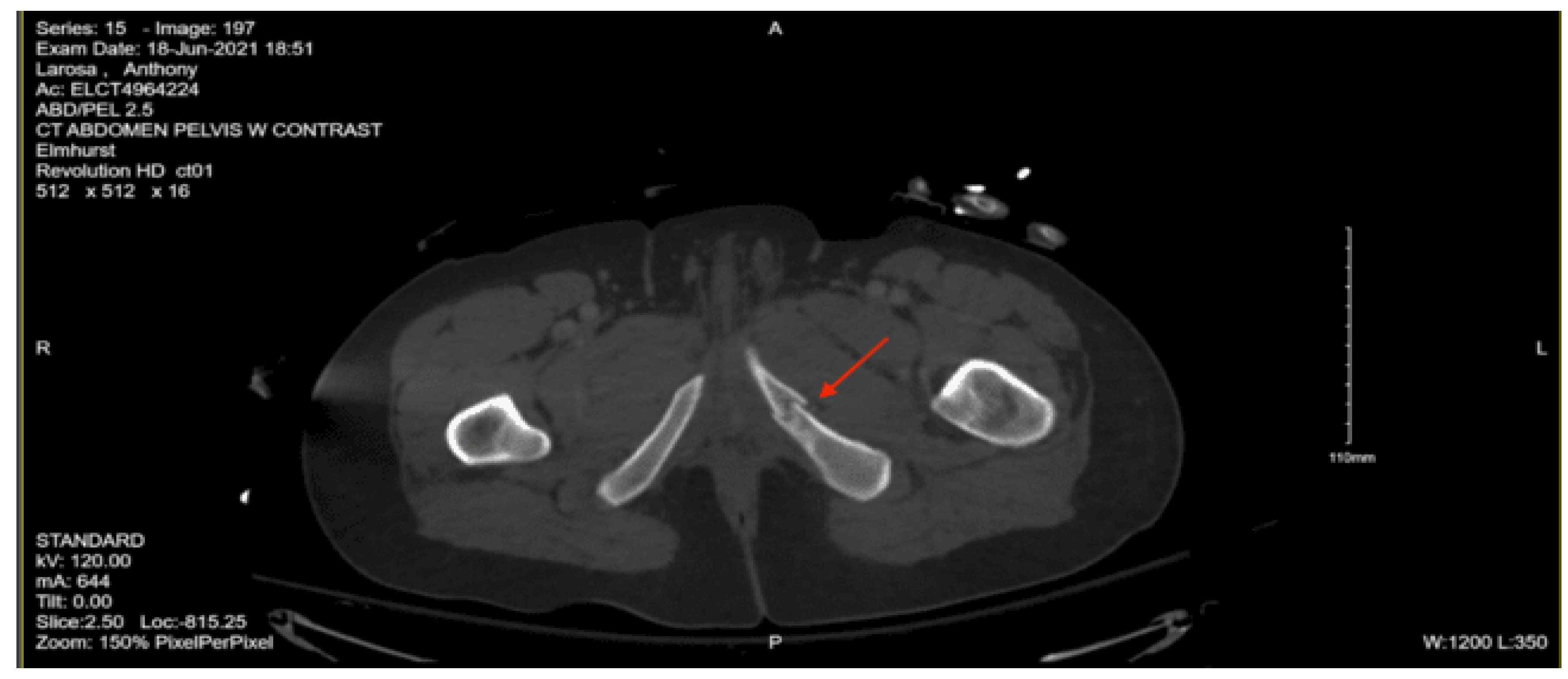

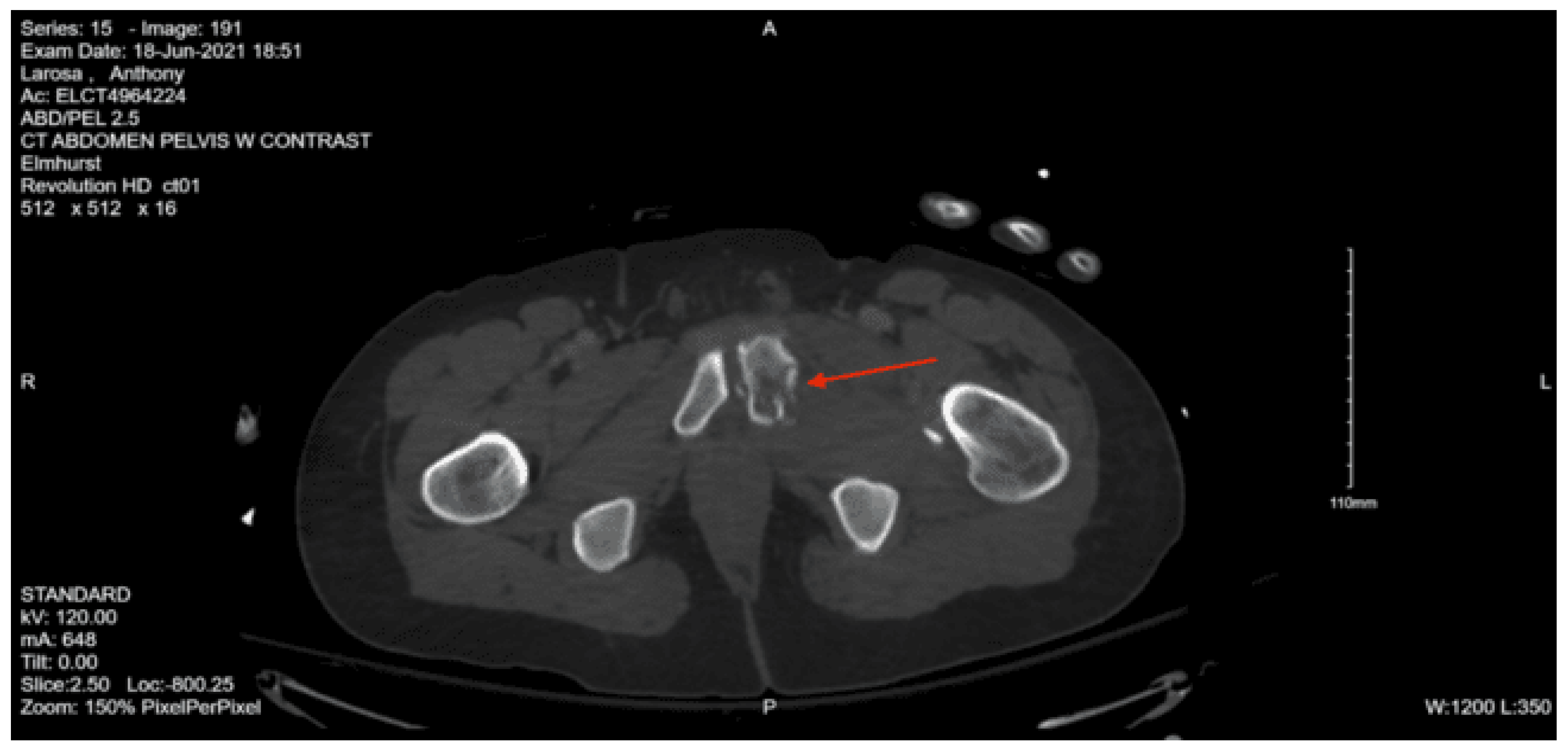

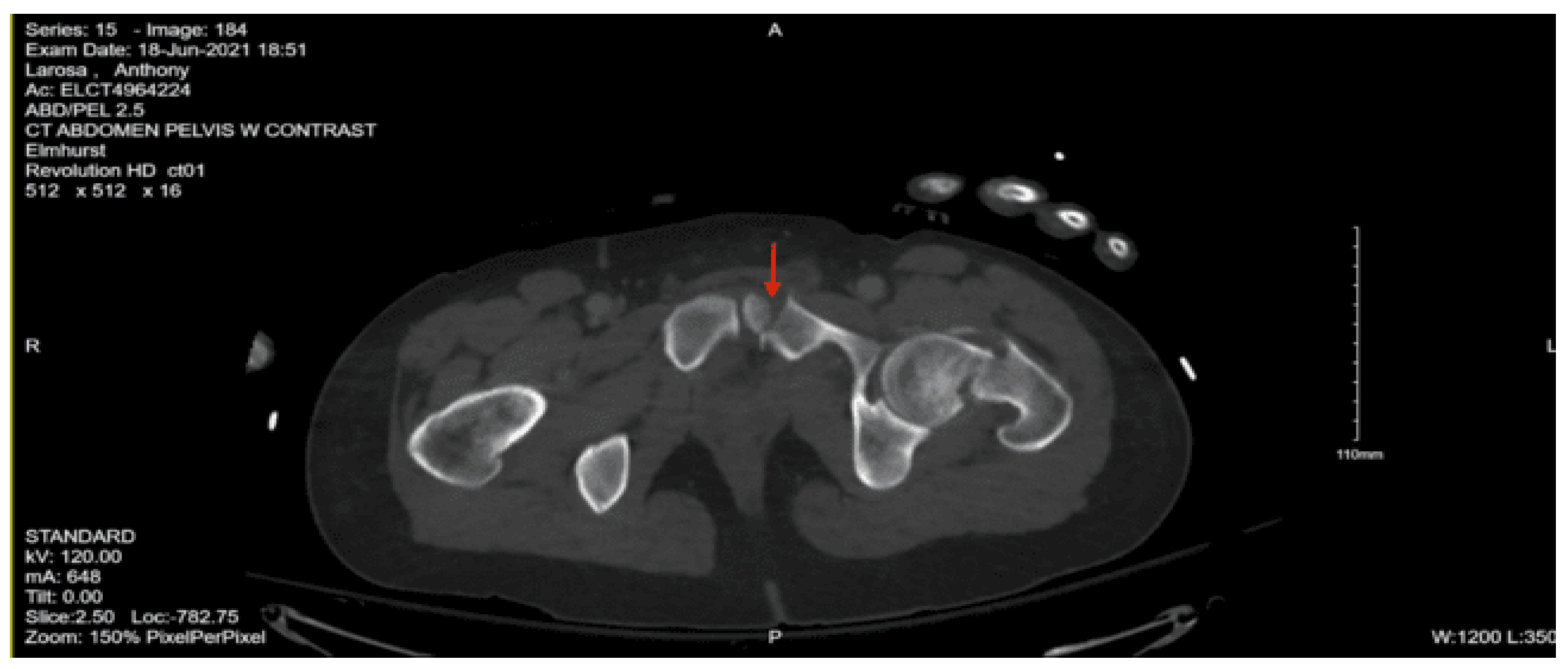

Portable pelvic x-ray: comminuted fracture of the left pubis and adjacent superior and inferior pubic rami. Left femoral neck fracture with no dislocation.

CT head non-contrast: no intracranial hemorrhage. Medial left frontal bone hairline fracture.

CT maxillofacial non-contrast: Fractures of the frontal bone on the left extending across the left frontal sinus with resultant pneumocephalus in the left frontal region. Fracture of the frontal bone forming at the superior wall of the left orbit, the fracture line extends through the length of the orbit. Left periorbital soft tissue emphysema. No retrobulbar lesions/hematomas were identified. Bilateral nasal bone fractures.

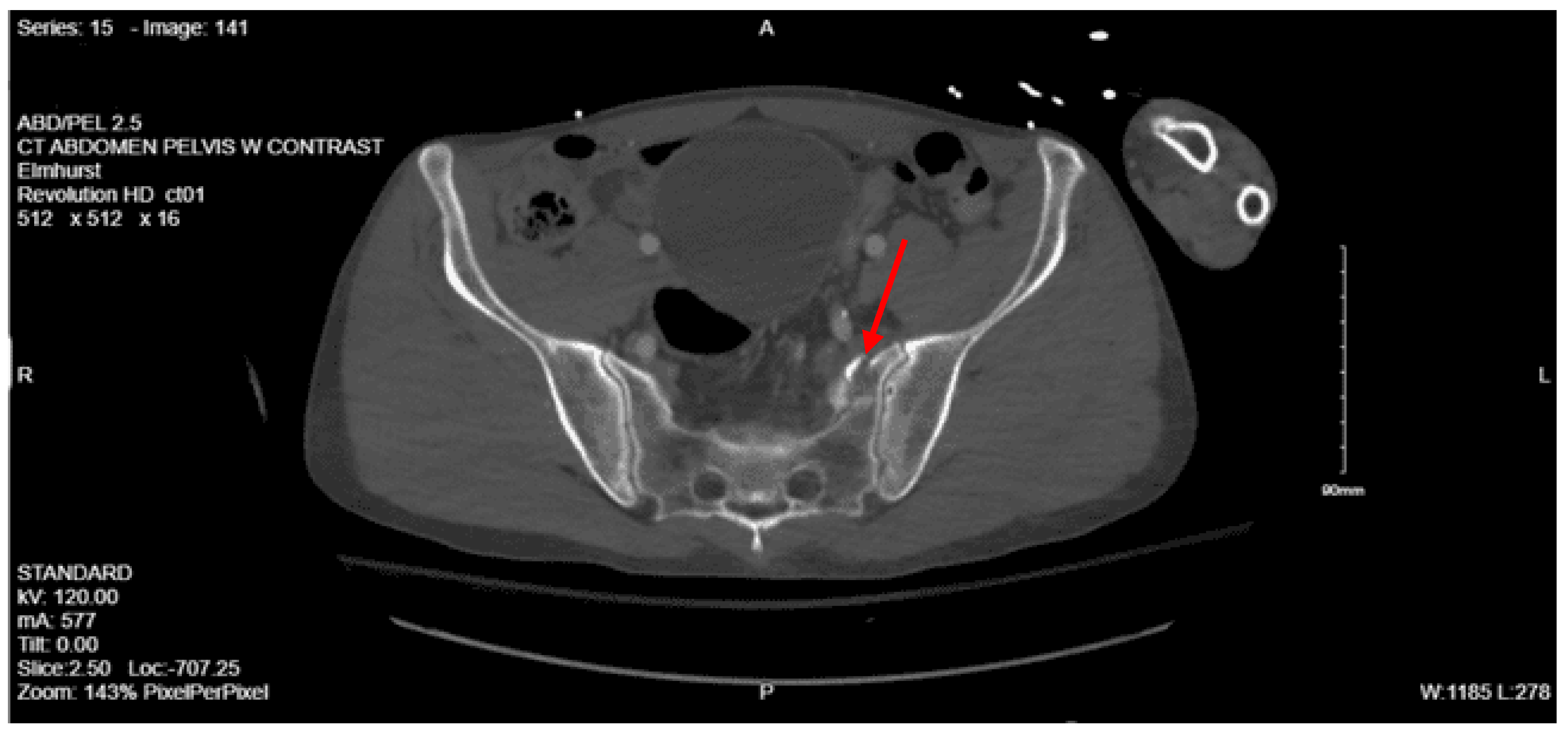

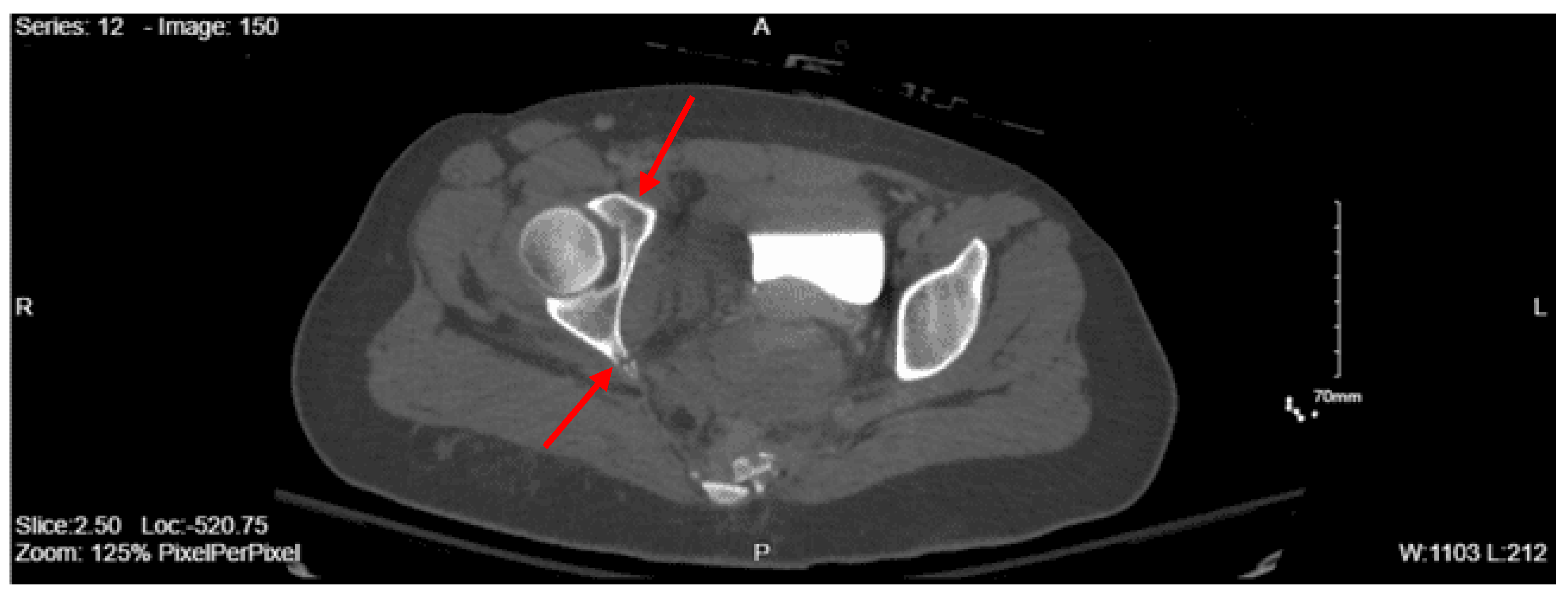

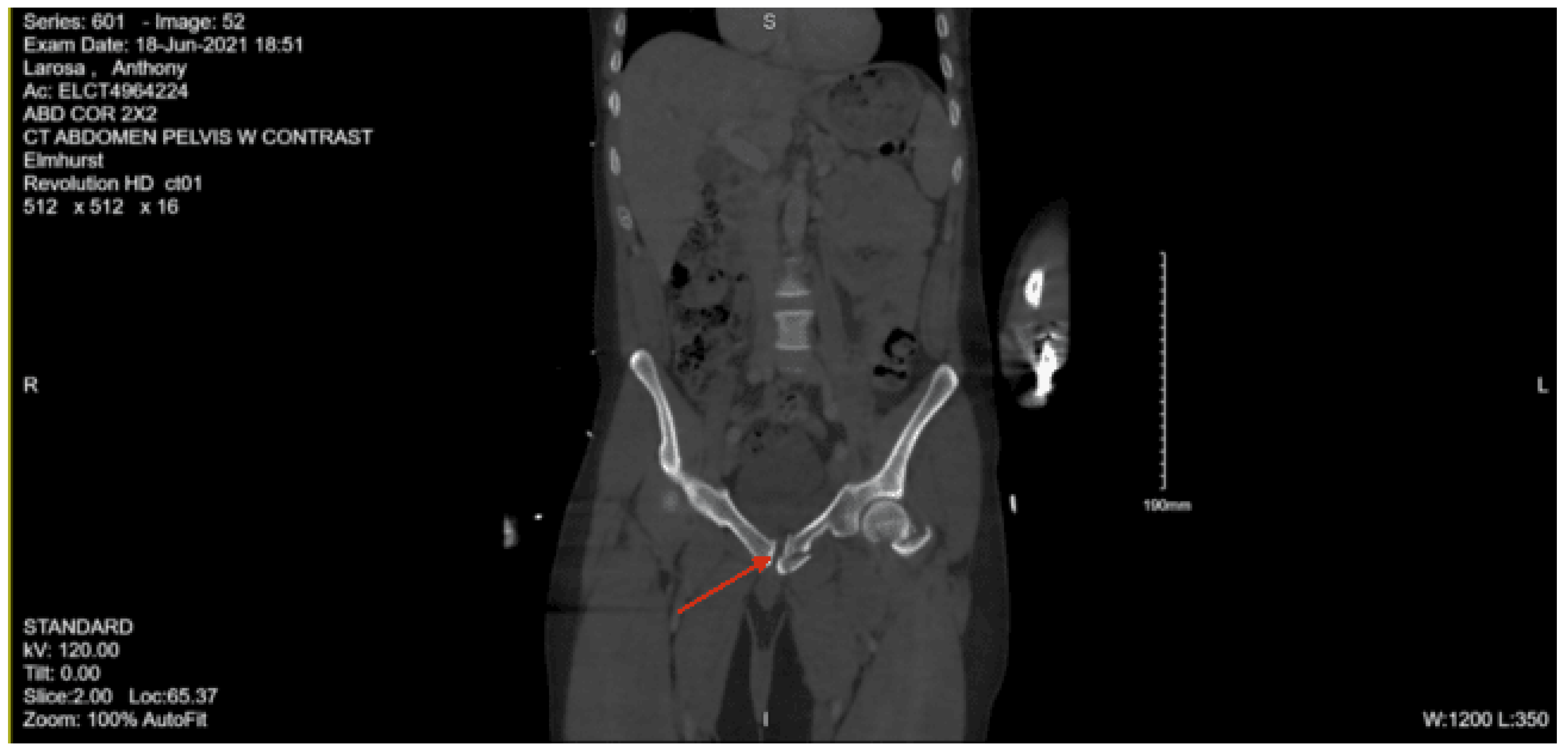

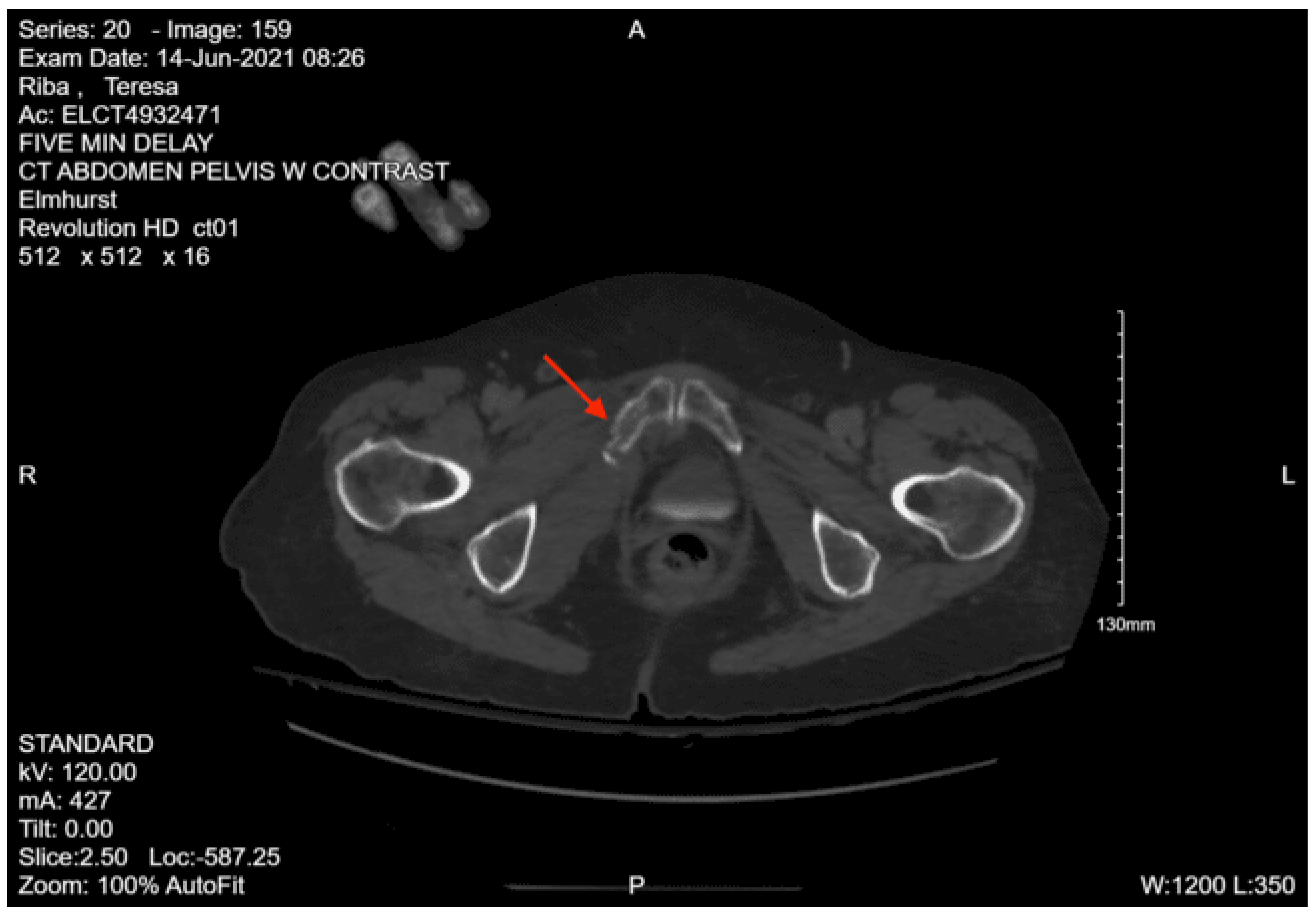

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: Left sacrum nondisplaced fracture extending through the neural foramina throughout its entirety. Mild widening of the SI joint. Incomplete hairline fracture of the iliac bone medially just above the acetabulum. Left pubis, most medial superior ramus, and more extensive left inferior pubic ramus fractures. Comminuted fracture of the left femoral neck. Anterior perivesical and left pelvic hematomas.

Left elbow complete x-ray: Proximal ulnar olecranon acute comminuted fracture and acute fracture of the radial neck.

After completing his full-body imaging, the patient was admitted to the STICU. Neurosurgery was consulted for the sacral, L2 transverse process, and pelvic fractures, and they recommended a thoracic-lumbar-sacral orthosis brace, bed rest, a trial of void with a post-void residual the following day, and adequate pain control. The orthopedic surgery team was consulted, and a padded posterior splint was placed on the left upper extremity. It was recommended that the patient be non-weight bearing in the left upper and left lower extremities. They planned to take the patient to the operating room the following day for an open reduction internal fixation of the left femur. The oral maxillofacial surgery team was consulted and initially recommended no acute surgical intervention, but they would re-evaluate the patient for possible interventions. On hospital day two, the patient underwent a closed reduction internal fixation with pinning of the left femoral neck fracture with the orthopedic surgery team, which the patient tolerated well. The patient was downgraded to the surgical step-down unit on hospital day three. On hospital day five, the patient underwent obliteration of the frontal sinus and closed reduction of the nasal bone with oral surgery. On hospital day eight, he underwent open reduction internal fixation of the left olecranon with orthopedic surgery. Addiction medicine followed the patient during admission for his history of substance use, and he was eventually transitioned to suboxone. He was followed by physical and occupational therapy during his stay, and they recommended that the patient be discharged to a sub-acute rehab facility once medically optimized. The patient was pending placement in a sub-acute rehab facility for several days and remained stable. On hospital day 41, he was eventually discharged to subacute rehab.

Case 12

An 86-year-old female with a past medical history of dementia was brought in by family after an unwitnessed fall; the patient was found at the bottom of the stairs by her husband. It was unclear how many steps she had fallen, and she was unable to provide further history, given her severe dementia. On arrival, her vital signs were BP 157/76, pulse 110, SpO2 94% on room air. On the primary survey, her airway was patent, self-maintained, and the patient was speaking. Her chest was clear to auscultation bilaterally with good chest wall excursion. She had strong distal pulses on all four extremities, and no gross bleeding was appreciated. She was moving all her extremities spontaneously. Her GCS was 14, and per her family, she was at her neurologic baseline.

On the secondary survey, her extraocular movements were intact, and her pupils were equal, round, and bilaterally reactive to light. She had no hemotympanum, and her trachea was midline. Her chest had no visible injuries but was tender to palpation on the right side without crepitus. Her abdomen was soft, non-distended, and non-tender. She had tenderness to palpation to the left shoulder, elbow, and wrist without any obvious deformities. She also had tenderness to palpation at the right hip, but her right lower extremity was not externally rotated or shortened. Her E-FAST was negative for intraperitoneal fluid, pericardial effusion, or pneumothorax.

Portable chest x-ray: no focal consolidation

Portable pelvic x-ray: mildly displaced right inferior and possibly superior pubic rami fractures

CT Head non-contrast: Small quantities of scattered subarachnoid hemorrhage over the cerebral convexities. Small acute subdural hematoma in the interhemispheric fissure without significant mass effect.

CT cervical spine non-contrast: No fracture or vertebral malalignment is demonstrated

CT thoracic spine non-contrast: Nondisplaced right T8-10 transverse process fractures. Multiple displaced and nondisplaced right rib fractures.

CT lumbar spine non-contrast: Nondisplaced right sacral ala fracture

CT Angiography Pulmonary Embolism with contrast: There is no evidence of central intraluminal pulmonary arterial defect. Minimally displaced right third and fourth rib fractures. There is a small volume of right pleural effusion, particularly in the upper thorax and apex.

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: No evidence of solid abdominal organ injury is seen. There are right superior and inferior rami fractures, and adjacent pelvic muscular enlargement likely secondary to intramuscular hematoma. There is a right pubic symphysis fracture with adjacent hematoma.

Left elbow x-ray: left radial head fracture.

Per recommendations from the neurosurgery team, the ED team obtained a repeat CT head non-contrast for the patient, which appeared to have been stable with some improvement in the acute subdural hematoma. Given this finding, the neurosurgery team recommended loading the patient with Keppra and optimizing her pain control. The orthopedic surgery team was consulted, given her traumatic injuries, and they recommended that her weight-bearing status be protected weight bearing with physical therapy. They were opting for nonoperative management, and once she had mobilized with physical therapy, they would plan to re-image two weeks later. As for the left radial head fracture, they recommended a sling for comfort. On hospital day one, the physical medicine and rehabilitation team was consulted, and they recommended starting physical and occupational therapy. On her second hospital day, she was downgraded to the surgical step-down unit. On the fourth hospital day, physical and occupational therapy evaluated the patient and recommended subacute rehab once the patient became medically stabilized. On hospital day eight, she was found to have a urinary tract infection and was started on Macrobid. The patient remained stable throughout her hospital course and was deemed medically optimized by her 15th hospital day when she was discharged to subacute rehab.

Case 13

A 28-year-old female with no significant past medical history was brought in by EMS after being struck by a vehicle going at 15-45 miles per hour. She was a pedestrian and, per the report, flew 15 feet and lost consciousness. Her vital signs on arrival were BP 124/98, Pulse 106, RR 4, SpO2 92%, temp 36.2. On arrival, her GCS was 6 (E1V1M4), and while in the ED, she was intubated in the trauma bay for airway protection and placed on propofol and fentanyl for post-intubation sedation, and bilateral chest tubes were placed for tension hemopneumothoraces. During the primary survey, the patient was tolerating the vent well. She had breath sounds bilaterally since the placement of the chest tubes, with about 100mL of bloody output from the left chest tube and about 20mL from the right chest tube. The patient then rapidly declined and became hypotensive to 80s/40s and was initiated on mass transfusion protocol - in total, she was given four units of packed red blood cells and four units of fresh frozen plasma with improvement in her blood pressure. On the secondary survey, she had epistaxis and blood in the oropharynx. Her right pupil was fixed and dilated. Her trachea was midline. The team was unable to assess for tenderness to her chest; she had bilateral chest tubes in place, and there was mild crepitus to palpation bilaterally. On her back exam, there were no step-offs or deformities. Her abdomen was soft and non-distended. Her pelvis was stable to compression. On examination of her extremities, she was withdrawing from pain in her upper and lower extremities, with distal pulses palpable and intact. Given the concern for increased intracranial pressure due to her exam, she was given hypertonic saline.

Portable chest x-ray: intubated with left apical chest tube with small residual left apical pneumothorax and nondisplaced midshaft right clavicular fracture as well as airspace infiltrates seen most prominently involving the left upper lobe, including the lingula, and minimally seen in the right upper lobe.

Portable pelvic x-ray: Possibility of avulsed fracture medial to the left acetabulum and additional fracture at the junction of the left ischium and inferior pubic ramus.

CT head non-contrast: no definite evidence of acute parenchymal bleed nor definite subarachnoid hemorrhage. Non-depressed right frontotemporal skull fracture.

CT angiography head: unremarkable intracranial CT angiogram. No arterial disruption or pooling of contrast. No stenosis or occlusion. Congenital variation with the right anterior cerebral artery A1 hypoplasia. Right intracranial pneumocephalus. No epidural or subdural bleed. Right mastoid and temporoparietal skull fractures.

CT angiography neck: No visualized arterial disruption. No dissection, stenosis, or occlusion. Normal visualization of the great vessels and bilateral subclavian arteries. Endotracheal tube tip at the carina. Right midshaft clavicular fracture.

CT chest with contrast: Interval placement of right mid and left upper lung field chest tubes with small residual left apical pneumothorax. Atelectasis/pulmonary contusion involving the left upper lobe. Multiple areas of subcutaneous emphysema secondary to trauma and multiple bilateral rib fractures.

CT abdomen pelvis with contrast: No acute visceral traumatic abnormalities noted. Acute avulsed fracture of the superior-lateral acetabulum and multi-comminuted fractures with distracted bony fragments left in the acetabulum and an acute fracture of the medial aspect of the left superior pubic ramus.

Given the fractures on CT and her decompensation, interventional radiology was consulted, and the patient was taken to the IR suite for a pelvic angiogram and embolization. During the angiogram, they found no evidence of extravasation or pseudoaneurysm and successfully prophylactically embolized the left hypogastric, given the mechanism of injury. After her procedure, the patient was transported to the STICU for management of her traumatic injuries. Orthopedic surgery was consulted and recommended a complete x-ray of her pelvis and an x-ray of her clavicle. As for her weight-bearing status, they recommended non-weight-bearing in the left lower extremity and right upper extremity. There was no emergent indication for orthopedic intervention, and planned for an open reduction internal fixation of the left acetabulum once the patient stabilized. On arrival to the STICU, the patient was noted to have pupillary changes and an episode of emesis, so a STAT CT head non-contrast was performed, which showed right superior frontal cortex subarachnoid hemorrhage with a small focus of parenchymal hemorrhage in the left parietal lobe. There were also hemorrhage layers in the quadrigeminal cistern and mild diffuse cerebral edema. Given these findings, a parenchymal ICP monitor was placed by neurosurgery on hospital day one. After the placement of the ICP monitor, the patient had another repeat CT head that showed a stable subarachnoid hemorrhage and intraparenchymal hemorrhage. ENT was consulted due to her right temporal bone fracture; they recommended that the team obtain a CT temporal bones and re-consult once the patient was no longer sedated so they could assess her facial nerve and hearing function. Later that day, the patient had transiently elevated intracranial pressures on the ICP monitor, so an external ventricular drain was placed by the neurosurgery team.

On hospital day two, the patient had her CT temporal bones, which demonstrated bilateral temporal bone, middle ear, and sphenoid bone fractures. On hospital day four, her left-sided chest tube was removed, and on the sixth hospital day, the right-sided chest tube was removed. On the eighth hospital day, the palliative care team was consulted, given the patient’s severe traumatic brain injury, and a goals of care conversation was held with the family and the treatment teams. And after the discussion, the family wanted to continue with aggressive care, and the patient remained full code. Later that day, the patient had a repeat CT of the chest, which showed a large left pneumothorax, so a left-sided chest tube was placed. The patient had a tracheostomy and bronchoscopy on her tenth hospital day. She also had developed fevers, and her sputum cultures were found to be growing Klebsiella, Streptococcus viridans, group F strep, so she was started on empiric antibiotics. That same day, the neurosurgery team removed her external ventricular drain. On hospital day 12, she had an MRI of the brain without contrast, which was consistent with diffuse axonal injury.

On hospital day 15, the physical medicine and rehabilitation team was consulted, and they recommended that the patient start physical and occupational therapy at the bedside. The following day, they evaluated the patient and recommended that the patient would benefit from traumatic brain injury rehab. On hospital day 17, she had the left chest tube removed and had been tolerating the trach collar more consistently. On hospital day 20, she had an episode of bradycardia that spontaneously resolved. During the morning rounds, she was found to have fixed and dilated pupils with a comatose exam, so the STICU team placed an intraosseous line and gave hypertonic saline. She was taken emergently for CT brain and CT angio brain, which showed left frontal hemorrhage and mass effect. She was then taken to the operating room by neurosurgery and underwent a left decompressive craniectomy with evacuation of left frontal intracranial hemorrhage and placement of a left external ventricular drain. On hospital day 22, she had a repeat CT head non-contrast, which demonstrated a new left posterior communicating artery infarct. The following day, her left frontal external ventricular drain had minimal drainage and elevated ICP readings despite troubleshooting, so the EVD was removed and replaced with a new right frontal EVD.

On hospital day 37, a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube was placed by the STICU team. On hospital day 39, the patient was downgraded to the surgical step-down unit. Throughout the rest of her hospital course, the patient continued to improve and could stay on a trach collar and tolerated the PEG tube placement well. Per the orthopedic surgery team, the patient was out of the surgical repair window due to her continued tenuous neurosurgical issues, so they recommended non-weight bearing on the left lower extremity. She had minimal neurologic improvement and was able to open her eyes spontaneously, but was not able to track. She had spontaneous, non-purposeful movements greater on the left than the right, but did not follow verbal commands. On hospital day 58, she was deemed stable for discharge to a long-term acute care hospital for continued management of her traumatic injuries.