Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) represents a major global health challenge, being a leading cause of both death and disability resulting from trauma. In the United States, TBI accounts for approximately 52,000 deaths annually [

1,

2], imposing a significant economic burden with treatment and care costs reaching an estimated

$48.3 billion per year [

1,

2]. The consequences of TBI extend beyond mortality, leading to a variety of severe, long-term complications, including neurological disorders such as seizures and hydrocephalus (an accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid), vascular and nerve injuries, multiple organ dysfunction, and severe disruptions in fluid and hormonal balance[

3]. Additionally, TBI patients are prone to developing deep vein thrombosis and coagulopathies, which complicate their clinical management[

3].

Among the numerous complications following TBI, electrolyte disturbances, particularly those involving potassium, have received growing attention in recent years. While much of the research in this area has focused on the effects of sodium imbalances on TBI outcomes, the impact of potassium dysregulation remains relatively underexplored [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Potassium is a critical intracellular cation essential for maintaining cellular functions, including electrical excitability, muscle contraction, and acid-base balance. It is tightly regulated in normal conditions, with low extracellular concentrations maintained by sodium-potassium pumps. However, in the setting of TBI, this regulation can be disrupted, leading to potassium imbalances such as hypokalemia (low potassium) and hyperkalemia (high potassium), both of which are commonly observed in trauma patients. Electrolyte disturbances, including potassium imbalances, are found in up to 50% of trauma cases[

8]. TBI patients, in particular, face a higher risk of hypokalemia, with studies indicating that up to 45% of these patients are affected.[

7,

9,

10] Hypokalemia is associated with serious clinical complications, including cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, and hyperglycemia, all of which can complicate the management and recovery of TBI patients [

11,

12]. On the other hand, hyperkalemia is less common but still affects approximately 17.77% of TBI patients. It often emerges during the early resuscitative phase and has a period prevalence of 29% within the first 12 hours following admission in non-crush trauma patients [

13,

14]. Hyperkalemia typically follows a phase of hypokalemia and is associated with factors such as catecholamine release, blood transfusions, the administration of pharmacological agents like succinylcholine, acidosis, and tissue ischemia [

15,

16,

17]. Hypokalemia tends to develop immediately following injury, peaking within the first few days as a result of catecholamine-induced shifts in potassium, renal loss of potassium, fluid deficits, and hypothermia. Younger patients and those with more severe injuries are particularly vulnerable to these electrolyte disturbances, often facing additional complications that increase the risk of mortality [

15,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The thresholds for potassium levels in TBI patients have been widely discussed in the literature, though clinical outcomes vary depending on individual cases. Hypokalemia is typically defined as a potassium concentration below 3.5 mEq/L, while hyperkalemia is defined as levels exceeding 4.5 mEq/

mEq/L[

6,

10,

22,

23,

24], with extreme hyperkalemia being classified as greater than 6 mEq/L[

25]. In this study, we define extreme hypokalemia as potassium levels below 2.5 mEq/L, hypokalemia as 2.6–3.5 mEq/L, normokalemia as 3.5–5.2 mEq/L, and hyperkalemia as 5.2–7.0 mEq/L, excluding extreme hyperkalemia (>7.0 mEq/L). These values are generally in line with literature value ranges [

6,

10,

22,

23,

24].

The occurrence of hypokalemia following TBI is well-documented [

4,

8], yet a more nuanced understanding of how varying degrees of potassium imbalances influence clinical outcomes at different stages of hospitalization remains necessary. Specifically, the impact of potassium fluctuations on outcomes during the initial admission, throughout intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and at ICU discharge is not fully understood. Given the high prevalence of TBI and its profound effects on both physical and cognitive function, identifying reliable prognostic markers is essential [

26]. This knowledge is crucial not only for improving clinical decision-making but also for optimizing resource allocation and evaluating treatment efficacy.

We hypothesize that fluctuations in potassium levels, especially severe hypokalemia, are linked to worsened clinical outcomes in TBI patients. The primary objective of this study is to examine the relationship between potassium levels and key clinical predictors, such as the Injury Severity Score (ISS), the initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score at the time of emergency room admission, and various outcomes including mortality, length of hospital stay (LOS), ICU duration, and mechanical ventilation requirements. By investigating potassium as a potential biomarker, this study aims to highlight its critical role in optimizing patient care and improving outcomes for individuals with severe TBI.

Method

Study Population

This is a single-center, retrospective review conducted at a level 1 trauma center verified by the American College of Surgeons in Queens, New York City. We included all patients who presented with a severe TBI between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2023, inclusive. All patients with an Abbreviated Injury Severity (AIS) score of 3 or higher were included. Patients who were discharged or transferred and had potassium levels collected were also included in the analysis. We excluded patients who had a COVID-19 infection at the time of their injury, who died or were discharged within 24 hours of their initial injury, and AIS less than 3 (minor and moderate injuries). We found a total of 1040 patients with severe TBIs, and 981 total patients were included in the study. This study received approval from the institutional review board (IRB) at Elmhurst Facility with IRB number 24-12-092-05G.

Data for all patients with severe TBI were requested from the National Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (NTRACS) database at our center, Elmhurst Hospital Center. NTRACS gathers various categories of TBIs. To maintain clarity in our table and results, we have included only the combinations of TBIs that are relevant to our study. When necessary, we reviewed the patient’s medical charts to collect all pertinent information required for this research. Patients were identified based on the injury mechanism, cause of injury, primary mechanisms (lCD9 or lCDL0 E-Code), and the AIS score (head). The AIS score ranges from 1 to 6 per body region. Severe TBI is defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or less after resuscitation but before sedation given to the patient. We analyzed the potassium levels within five categories: extreme hypokalemia (less than 2.5 mEq/L), hypokalemia (2.6–3.5 mEq/L), normokalemia (3.5–5.2 mEq/L), hyperkalemia (5.2-7.0mEq/L), and extreme hyperkalemia (greater than 7.0 mEg/L) and studied if there were any statistically significant differences in potassium levels at hospital admission (TA), ICU admission (RL1), and ICU discharge (RL2), hospital discharge (HD), and at patient death (PD) across various clinical outcomes. Clinical outcomes studies were ED, ICU, Hospital length of stay, mechanical ventilation time, and mortality.

Data Collection

We collected data using a data collection tool (Excel sheet or spreadsheet). We incorporated all data elements into this tool, for example, patient demographics, clinical outcomes, and biochemical data. Baseline admission data included data elements like demographics (age, sex, race, ethnicity), the AIS, and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) injury description. Age ranges were divided into groups: pediatric (less than 15), young adults (ages 15 to 25), older adults (ages 24 to 64), and elderly (ages greater than 65). Sex was categorized as male and female. We also investigated based on the types of injury, blunt vs. penetrating.

Further subset analysis was performed based on the unique intracranial ICD-10 codes assigned to each patient. The potassium was obtained manually from charts at four pre-determined time frames of a patient’s hospital stay. These were hospital admission, ICU admission, ICU discharge, and then either death or hospital discharge. “Admission” was defined as the first measured level of a metabolite after admission to the trauma bay. “ICU admission” was defined as the first measured level of a metabolite after admission to the ICU. At the same time, “ICU discharge” was the last measured level of a metabolite before arrival in a step-down or floor unit. “Hospital discharge” was the last measured value for a metabolite before discharge, and “death” was the last measured value before the time of death. In a few cases, missing data were filled in by taking the most recent potassium measurement in a given defined time frame [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12], even if that potassium value was used for another time frame. For example, if a patient was discharged with only one set of lab values obtained, the potassium level that was used for admission was also used for discharge, as that was technically the first KL obtained during hospital admission and the last obtained before hospital discharge. Given the universal use of basic metabolic panels and blood gases, the amount of missed potassium values, while not counted, was negligible for our study. The primary outcome variable in this dataset was mortality. Secondary outcomes were ED LOS, hospital LOS, ICU LOS, and days requiring mechanical ventilation. All secondary outcomes were measured in days, and mortality was assigned a binary variable, 0 for no mortality recorded and 1 if a patient had a recorded mortality. To convert KL to a categorial variable for these analyses, patients were assigned a potassium range based on accepted levels in the literature [

10,

22,

23]

,. KL was categorized into the following ranges: extreme hypokalemia (less than 2.5 mEq/L), hypokalemia (2.6–3.5 mEq/L), normokalemia (3.5–5.2 mEq/L), hyperkalemia (5.2-7.0mEq/L). Pearson Chi-square tests were conducted to test the association between certain categorical variables. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to test if various scores and lengths of stays differed between different K levels for K measured at different points of stay. The analyses were conducted in SAS Version 9.4. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Results

A total of 981 patients were included in the study after applying the exclusion criteria. Among these patients, 752 were male, and 229 were female. The age distribution was as follows: 17 patients were in the pediatric group (0 to less than 15 years old), 60 in the younger adult group (greater than or equal to 15 to less than 24 years old), 579 in the older adult group (greater than or equal to 24 to less than or equal to 64 years old), and 310 in the elderly group (greater than or equal to 65 years old). The average age of all participants was 53 years. Of the reported injuries, 961 were due to blunt trauma, while 20 were classified as penetrating trauma. Moreover, 126 patients in our study died, and 855 patients survived their index hospitalization. The average length of hospitalization was 12 days, the average ICU stay was 4 days, and the average length of ventilator use was 2 days.

Our comprehensive analysis categorized potassium levels into five distinct ranges: extreme hypokalemia (less than 2.5 mEq/L), hypokalemia (2.6–3.5 mEq/L), normokalemia (3.5–5.2 mEq/L), hyperkalemia (5.2–7.0 mEq/L), and extreme hyperkalemia (greater than 7.0 mEq/L)[

10,

22,

23,

24]. This categorization provided valuable insights into the relationship between potassium imbalances and various clinical outcomes.

Potassium levels were measured at key stages of the hospital stay: admission (TA), ICU admission (RL1), ICU discharge (RL2), hospital discharge (HD), and patient death (PD). The results reveal a significant shift in potassium levels as patients progress through their hospitalization, particularly among those admitted to the ICU.

Table 1 presents the frequency, percentage, cumulative frequency, and cumulative percentage of various potassium levels (extreme hypokalemia, hypokalemia, normokalemia, and hyperkalemia) at each time point.

Upon hospital admission (TA), most patients (79.71%) had normal potassium levels, with 12.03% experiencing hypokalemia and 4.28% exhibiting extreme hypokalemia. Only a small percentage (3.98%) showed hyperkalemia. However, by the time patients entered the ICU (RL1), there was a drastic shift in potassium levels. Extreme hypokalemia rose sharply to 39.14%, while hypokalemia decreased to 7.75%. Normokalemia was still observed in 51.07% of patients, but hyperkalemia was significantly reduced to 2.04% (

Table 1).

As patients progressed to ICU discharge (RL2), extreme hypokalemia increased further to 42.71%, while hypokalemia dropped to 3.77%. Normokalemia remained relatively stable at 52.80%, and hyperkalemia decreased even further to 0.71%. At hospital discharge (HD), extreme hypokalemia accounted for 28.03% of patients, with hypokalemia in 2.45% and normokalemia in 68.60%. Hyperkalemia remained low at 0.92% (

Table 1).

The data also revealed that, at the time of death (PD), 91.95% of patients had extreme hypokalemia, while only 0.82% had hypokalemia, 4.69% had normokalemia, and 1.43% exhibited extreme hyperkalemia. These findings suggest that as patients progress through their hospitalization, potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia, become more prevalent, and extreme hypokalemia is strongly associated with patient mortality (

Table 1).

The overall percentages for all time points (hospital admission, ICU admission, ICU discharge, hospital discharge, and patient death) showed that extreme hypokalemia occurred in 49.03%, hypokalemia in 38.74%, normokalemia in 11.82%, and hyperkalemia in 0.31%. These results emphasize the prevalence of severe hypokalemia and hypokalemia as the primary pathologies in TBI patients (

Table 1).

The mean hospital length of stay (LOS) for patients with various potassium levels (extreme hypokalemia, hypokalemia, normokalemia, hyperkalemia, and extreme hyperkalemia) was compared at different time points during hospitalization, including hospital admission, ICU admission, ICU discharge, hospital discharge, and patient death (

Table 2).

At hospital admission, the mean LOS was highest in the hypokalemia group (13.16 days), followed by the hyperkalemia group (12.33 days), the normokalemia group (11.72 days), and the extreme hypokalemia group (5.29 days) (

Table 2).

At ICU admission, the mean LOS was highest in the hypokalemia group (14.05 days), followed by the normokalemia group (13.24 days), the hyperkalemia group (12.15 days), and the extreme hypokalemia group (9.06 days) (

Table 2).

At ICU discharge, the hyperkalemia group had the longest mean LOS (21.57 days), followed by the normokalemia group (14.21 days) and the extreme hypokalemia group (8.78 days) (

Table 2).

At hospital discharge, the normokalemia group had the longest LOS (12.42 days), followed by the hyperkalemia group (11.44 days), the extreme hypokalemia group (10.33 days), and the hypokalemia group (4.92 days) (

Table 2).

At the time of patient death (KPD), the hypokalemia group had the longest mean LOS (35.38 days), followed by the hyperkalemia group (19 days), the extreme hypokalemia group (11.51 days), the normokalemia group (10.32 days), and the extreme hyperkalemia group (5.86 days) (

Table 2). It is noteworthy that extreme hypokalemia (potassium levels higher than 7) was observed only in patients who died and was not seen at any other time point.

Table 2.

Mean hospital length of stay of various potassium levels at different time points during hospitalization.

Table 2.

Mean hospital length of stay of various potassium levels at different time points during hospitalization.

| K levels at hospital admission (ta) |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Frequency

|

Cumulative

Percent

|

| Extreme Hypokalemia - 2.5 or less mEq/L |

42 |

4.28 |

42 |

4.28 |

| Hypokalemia- 2.6–3.4 mEq/L |

118 |

12.03 |

160 |

16.31 |

| Normokalemia- 3.5 to 5.2 mEq/L |

782 |

79.71 |

942 |

96.02 |

| Hyperkalemia - greater than 5.2 mEq/L to 7.0 mEq/L |

39 |

3.98 |

981 |

100.00 |

| krl1 |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Frequency

|

Cumulative

Percent

|

| Extreme Hypokalemia - 2.5 or less mEq/L |

384 |

39.14 |

384 |

39.14 |

| Hypokalemia- 2.6–3.4 mEq/L |

76 |

7.75 |

460 |

46.89 |

| Normokalemia- 3.5 to 5.2 mEq/L |

501 |

51.07 |

961 |

97.96 |

| Hyperkalemia - greater than 5.2 mEq/L to 7.0 mEq/L |

20 |

2.04 |

981 |

100.00 |

| krl2 |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Frequency

|

Cumulative

Percent

|

| Extreme Hypokalemia - 2.5 or less mEq/L |

419 |

42.71 |

419 |

42.71 |

| Hypokalemia- 2.6–3.4 mEq/L |

37 |

3.77 |

456 |

46.48 |

| Normokalemia- 3.5 to 5.2 mEq/L |

518 |

52.80 |

974 |

99.29 |

| Hyperkalemia - greater than 5.2 mEq/L to 7.0 mEq/L |

7 |

0.71 |

981 |

100.00 |

| khd |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Frequency

|

Cumulative

Percent

|

| Extreme Hypokalemia - 2.5 or less mEq/L |

275 |

28.03 |

275 |

28.03 |

| Hypokalemia- 2.6–3.4 mEq/L |

24 |

2.45 |

299 |

30.48 |

| Normokalemia- 3.5 to 5.2 mEq/L |

673 |

68.60 |

972 |

99.08 |

| Hyperkalemia - greater than 5.2 mEq/L to 7.0 mEq/L |

9 |

0.92 |

981 |

100.00 |

| overallK |

Frequency |

Percent |

Cumulative

Frequency

|

Cumulative

Percent

|

| Extreme Hypokalemia - 2.5 or less mEq/L |

481 |

49.03 |

481 |

49.03 |

| Hypokalemia- 2.6–3.4 mEq/L |

380 |

38.74 |

861 |

87.77 |

| Normokalemia- 3.5 to 5.2 mEq/L |

116 |

11.82 |

977 |

99.59 |

| Hyperkalemia - greater than 5.2 mEq/L to 7.0 mEq/L |

3 |

0.31 |

980 |

99.90 |

In this study, various prognostic variables (ISS, initial GCS, ED LOS, hospital LOS, ICU length of stay, and ventilatory days) were compared at different times during which potassium levels were collected during hospitalization. These time points included hospital admission (KTA), ICU admission (KRL1), ICU discharge (KRL2), hospital discharge (KHD), and the time of patient death (KPD). The median ISS ranged from 16 to 18, with a quartile range of 14 to 15 across the various time points when potassium was collected. The median GCS recorded in the ED remained at 15, with a quartile range of 2 to 8 during the different collection times. The median ED length of stay (days) was between 8.84 and 9.97, with a quartile range of 9.44 to 14.30 at the different time points of potassium collection. The median hospital length of stay (days) ranged from 5 to 7, with a quartile range of 11 to 13 across the times potassium was collected. The median ICU length of stay (days) ranged from 1.28 to 2.2, with a quartile range of 3.84 to 4.91 at the various collection points. The median number of ventilatory days was 0 for all the time points at which potassium was collected.

This study found multiple significant relationships between potassium levels and various prognostic factors and outcomes. Several statistical methods were employed to analyze these relationships, including the Kruskal-Wallis test and the Chi-square test. These tests were used to compare variance across different groups, particularly when the data was not normally distributed. Potassium levels were measured at key points: hospital admission, ICU admission, ICU discharge, hospital discharge, and patient death for those who applied. Clinical outcomes such as age, race, length of hospital stay (HLOS), ICU length of stay (ICU LOS), ventilation days (VD), Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), and mortality were assessed to examine their correlation with potassium levels.

At hospital admission (TA), potassium levels were significantly associated with demographic factors such as patient age and race. Most patients in our analysis were between 24 and 64 years old, and we observed a significant difference in potassium levels based on age with a Chi-square statistic (χ²) of 21.32, sample size of 966, and p-value of 0.011. Significant differences in potassium levels were also found across different racial groups (χ² = 38.64, df = 18, sample size = 981, p = 0.003), suggesting that race may influence potassium regulation. No significant variation in potassium levels was observed between male and female patients at admission. Moreover, a near-significant trend was found between potassium levels at admission and hospital length of stay (HLOS) with a Kruskal-Wallis statistic (H) of 11.87, and a p-value of 0.079, suggesting that patients with more extreme potassium imbalances at admission may experience longer hospitalizations.

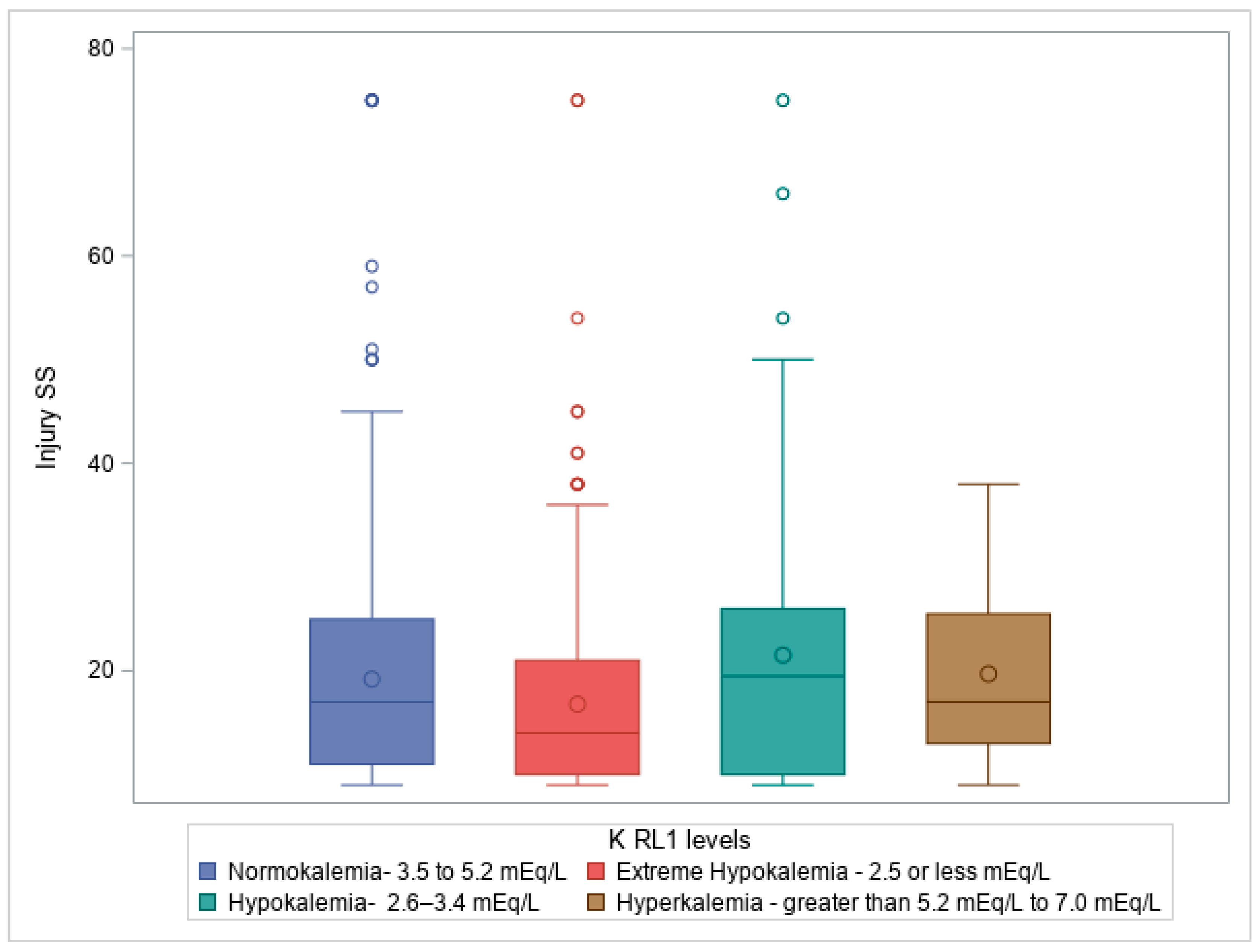

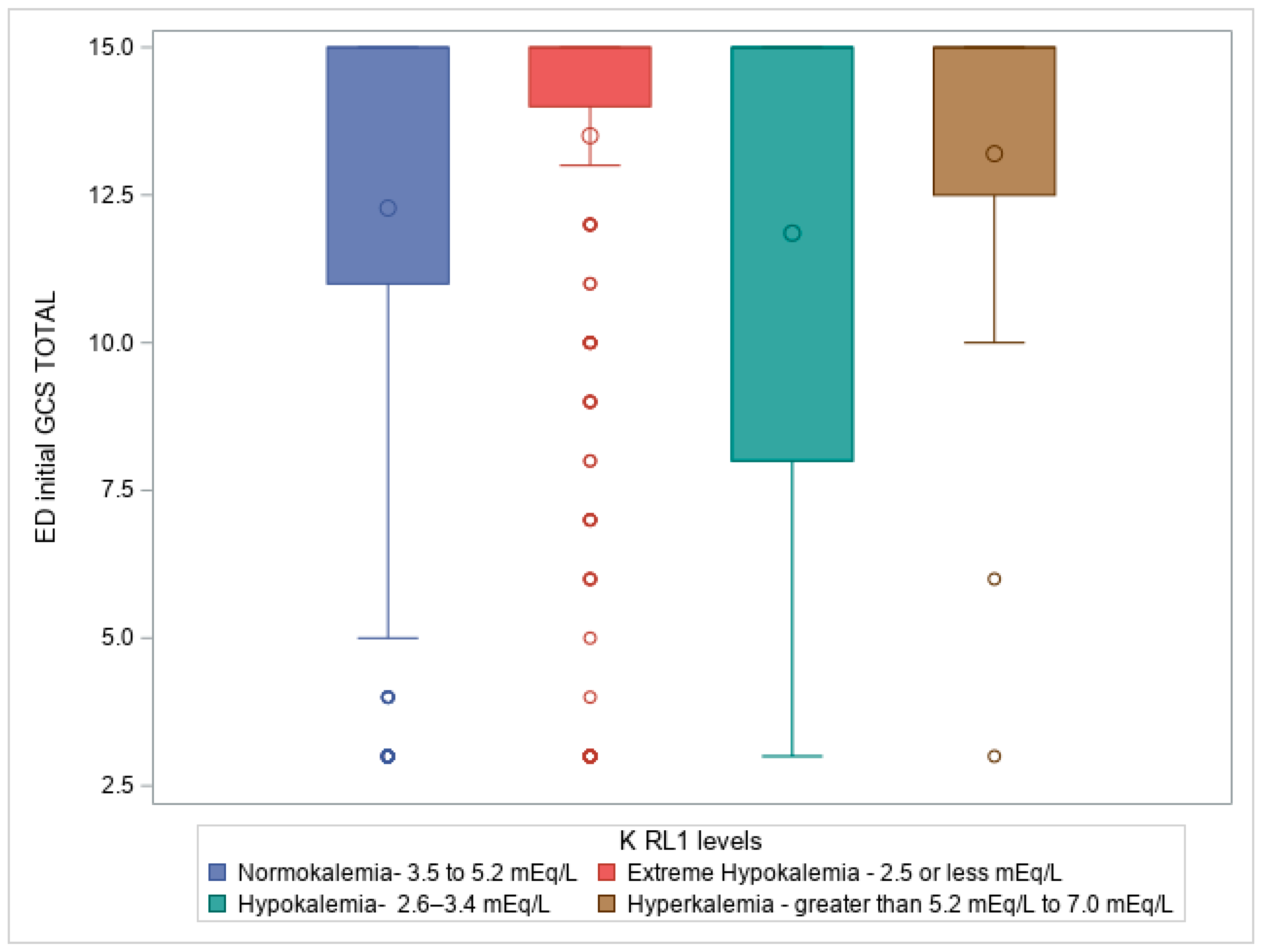

When examining potassium levels at trauma service admission (RL1), typically corresponding to ICU admission, our analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between potassium levels and various injury severity scores, including the AIS head, with a Chi-square statistic (χ²) of 17.75, sample size = 981, and p-value of 0.038. The Kruskal-Wallis test also revealed significant differences in potassium levels at ICU admission regarding Injury Severity Score (ISS) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) total score, with Kruskal-Wallis statistics (H) of 26.408 (p = 7.84E−6) and 28.694 (p = 2.6E−6), respectively.

Figure 1. Box plot illustrating Kruskal-Wallis test comparing ISS score on admission compared to Potassium level on admission to ICU (RL1 levels), p = 7.84E−6, where patients with hypokalemia had high ISS, followed by normokalemia, hyperkalemia, and then extreme hypokalemia.

Figure 2. Box plot illustrating Kruskal-Wallis test comparing ED initial GCS total to Potassium level on admission to ICU (RL1 levels), p =<0.0001, where patients with hypokalemia had a predominant frequency of patients with lower GCS in ED, followed by normokalemia, extreme hypokalemia, and lastly hyperkalemia.

Furthermore, potassium levels in the ICU were significantly associated with extended stays in both the emergency department (ED) (H = 21.80, df = 3, p = 6.87E−6) and the ICU (H = 100.305, df = 3, p = 1.34E−21), as well as the number of ventilation days required (H = 31.35, df = 3, p = 7.19E−7). These results suggest that potassium imbalances may not only reflect disease severity but also correlate with prolonged care needs, such as longer stays in critical care units and mechanical ventilation.

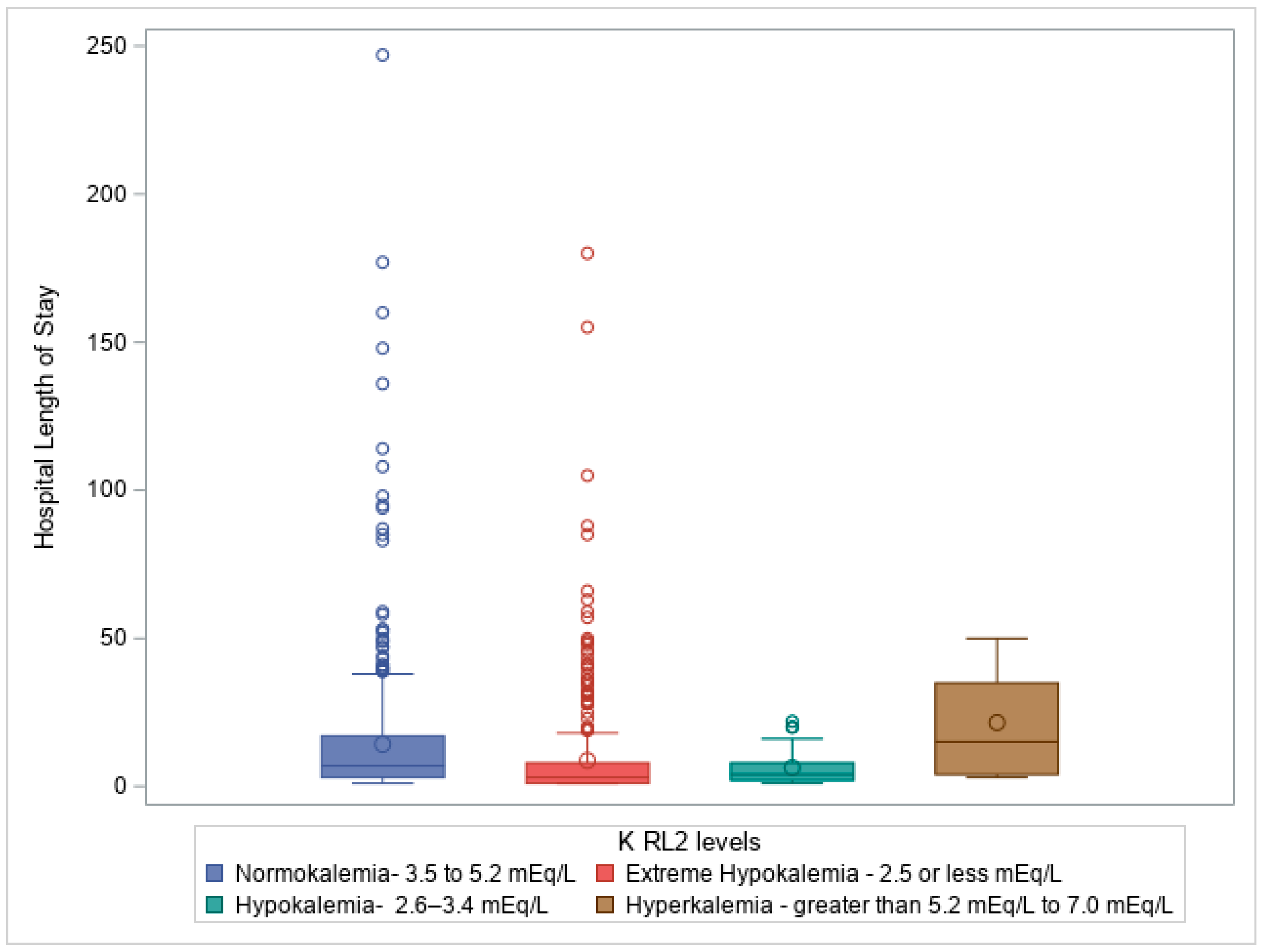

Similarly, a Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant difference in potassium levels at ICU discharge (RL2) about ISS (H = 14.48, df = 3, p = 0.002) and GCS (H = 14.59, df = 3, p = 0.002). Potassium levels at ICU discharge were also significantly linked to extended stays in the ED (H = 18.68, df = 3, p = 0.0003), hospital length of stay (H = 72.36, df = 3, p = 1.33E−15), ICU length of stay (H = 91.17, df = 3, p = 1.23E−19), and ventilation days (H = 16.89, df = 3, p = 0.0007).

Figure 3: Box plot illustrating Kruskal-Wallis test comparing hospital length of stay (days) to Potassium level on ICU discharge (RL2 levels), p =<0.0001, showing significant impact of potassium levels on HLOS.

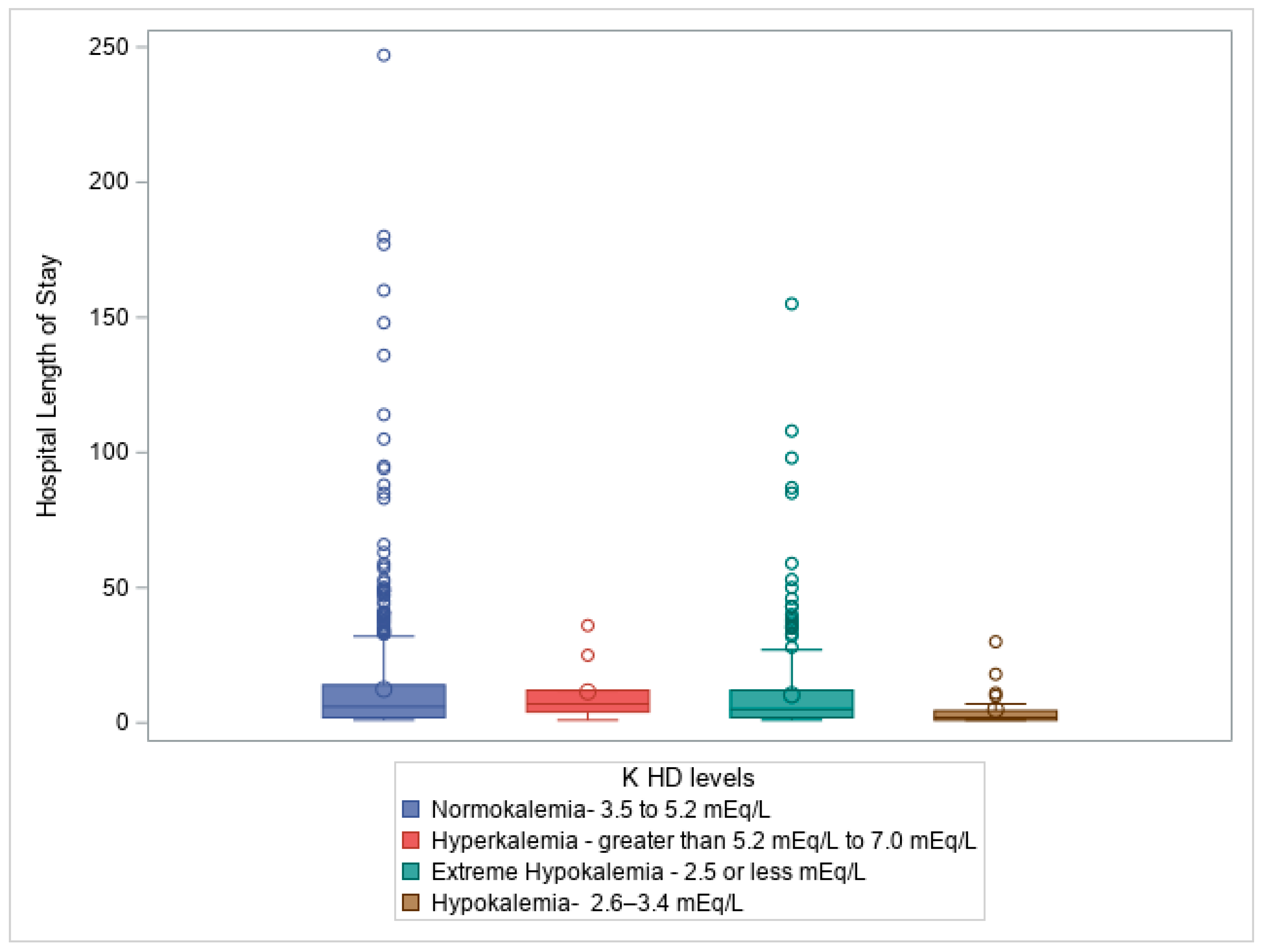

At hospital discharge (HD), potassium levels were strongly correlated with patient mortality, with a Chi-square statistic (χ²) of 24.323, 3 degrees of freedom (df), and a p-value < 0.0001, Additionally, potassium levels at discharge were significantly associated with HLOS (H = 11.56, df = 3, p = 0.009), suggesting that patients with longer hospital stays may experience greater disturbances in potassium balance, potentially due to prolonged illness, treatments, or complications.

Figure 4: Box plot illustrating Kruskal-Wallis test comparing hospital length of stay (days) to Potassium level on hospital discharge (K HD levels), p =0.009.

The analysis also highlighted potassium levels at the time of patient death, which were significantly correlated with several critical clinical factors, including ISS (H = 11.71, df = 4, p = 0.020), GCS (H = 12.82, df = 4, p = 0.012), ED length of stay (H = 14.47, df = 4, p = 0.006), ICU length of stay (H = 9.55, df = 4, p = 0.049), and ventilation days (H = 25.00, df = 4, p = 5E−5). Potassium levels at the time of patient death (PD) were strongly correlated with mortality, with a Chi-square statistic (χ²) of 98.32, and a p-value < 0.0001. These findings highlight the fact that severely ill patients, especially those requiring extended ICU stays and prolonged mechanical ventilation, are more likely to experience extreme potassium imbalances.

This study demonstrates a significant association between potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia, and critical clinical outcomes in trauma patients. As patients progress through their hospitalization, potassium disturbances, especially extreme hypokalemia, become more prevalent and are strongly correlated with patient mortality. The findings further suggest that potassium imbalances are linked to injury severity, Glasgow Coma Scale scores, and prolonged ICU and hospital stays. Given these associations, monitoring potassium levels could serve as a valuable prognostic tool in critically ill trauma patients, guiding treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

Discussion

Key Findings

This study is a single-center, retrospective review conducted at a Level 1 trauma center verified by the American College of Surgeons in Queens, New York City. We included all patients who presented with a severe TBI between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2023, inclusive. All patients with an Abbreviated Injury Severity (AIS) score of 3 or higher were included in the analysis.

The findings underscore the significant association between potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia, and various clinical outcomes in trauma patients. Potassium imbalances, especially extreme hypokalemia, were prevalent throughout the patient hospitalization process and became more pronounced as patients progressed through their ICU stays, with the most severe imbalances observed at the time of death.

At

hospital admission, most patients had normal potassium levels, but a significant proportion exhibited lower potassium levels, including hypokalemia and extreme hypokalemia.

Table 1 provides an overview of the distribution of potassium levels at this stage, showing that while most patients had normal potassium, a considerable percentage had abnormal levels, with hypokalemia and extreme hypokalemia being more common. The data also indicated that potassium levels at admission were influenced by demographic factors such as age and race, with some trends suggesting that certain demographic groups may be more prone to potassium imbalances.

Upon

ICU admission, there was a drastic shift in potassium levels. Extreme hypokalemia increased significantly, while hypokalemia decreased, and normokalemia remained relatively stable.

Figure 1 demonstrates the relationship between injury severity and potassium levels at ICU admission, showing that patients with more severe injuries were more likely to experience potassium imbalances. Similarly,

Figure 2 highlighted the association between GCS scores and potassium levels at ICU admission, suggesting that patients with more severe neurological injuries were also more likely to have lower potassium levels, particularly hypokalemia.

At

ICU discharge, extreme hypokalemia continued to increase, while hypokalemia further decreased. Potassium levels at this stage were significantly correlated with injury severity, ICU length of stay, and the need for ventilation.

Figure 3 depicts the correlation between potassium levels at ICU discharge and hospital length of stay, emphasizing that patients with more extreme potassium imbalances required prolonged care in both the ICU and the hospital.

At

hospital discharge, a large proportion of patients had normalized potassium levels, but extreme hypokalemia remained present in a significant portion of the cohort. The data indicated that potassium imbalances at discharge were strongly associated with mortality, with patients who had more severe imbalances at discharge more likely to experience worse outcomes.

Figure 4 illustrates the relationship between potassium levels at hospital discharge and length of stay, showing that patients with prolonged hospitalizations often had more significant potassium disturbances.

At patient death, nearly all patients exhibited extreme hypokalemia, underscoring the association between severe potassium imbalances and mortality. Potassium levels at the time of death were strongly correlated with injury severity, GCS scores, and prolonged care, including extended ICU stays and mechanical ventilation. These findings highlight that extreme potassium imbalances are not only a marker of illness severity but also serve as a prognostic indicator of patient outcomes.

Table 2 further supports these findings by showing the association between potassium levels and hospital length of stay. Patients with potassium imbalances, particularly hypokalemia, tended to have longer hospital stays, extended ICU stays, and higher mechanical ventilation requirements. The data underscores the clinical significance of monitoring potassium levels as a means to predict the length and intensity of care required, with more extreme imbalances generally corresponding to worse clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the critical role of potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia, in predicting clinical outcomes in trauma patients. The findings suggest that as patients progress through their hospitalization, potassium disturbances, especially extreme hypokalemia, become more prevalent and are closely associated with longer ICU and hospital stays, increased need for mechanical ventilation, and, ultimately, higher mortality. Monitoring potassium levels may therefore serve as a valuable prognostic tool in managing critically ill trauma patients, aiding in treatment decisions, and improving patient outcomes.

Comparison to Existing Literature

Our study findings align with existing literature that highlights the prevalence and clinical significance of potassium imbalances in trauma patients, particularly those with severe traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Dyskalemia, which includes both hypokalemia (low potassium) and hyperkalemia (high potassium), is frequently observed in up to 50% of trauma patients, with TBI patients being especially susceptible to hypokalemia [

8]. Previous studies report hypokalemia in 32.4% to 45% of TBI patients[

4,

7,

9,

10], which is consistent with our findings. In our study, we observed that 12.03% of patients exhibited hypokalemia upon hospital admission, which is in line with these previously reported rates. Upon ICU admission, extreme hypokalemia surged to 39.14%, and further increased to 42.71% by ICU discharge, demonstrating the progressive nature of potassium disturbances in critically ill TBI patients. These results mirror the literature, which emphasizes the worsening of hypokalemia during critical care[

8,

9].

Moreover, hypokalemia in TBI patients is associated with several serious clinical complications, such as cardiac arrhythmias, muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis, renal failure, and hyperglycemia, all of which complicate patient management [

11,

12]. Our study found that patients with hypokalemia had lower Glasgow Coma Scores (GCS) and higher Injury Severity Scores (ISS), supporting the existing body of research that associates hypokalemia with more severe injury and poorer clinical outcomes in TBI patients [

27]. This suggests that potassium disturbances, particularly hypokalemia, contribute to a poor prognosis, as reflected by the significant correlation between potassium levels and injury severity in our study. [

9,

11]

In addition, the literature supports the role of severe hypokalemia and hypophosphatemia as independent risk factors for mortality in TBI patients.[

4,

28] One study reported that the prevalence of severe hypokalemia was 4.4% in TBI patients[

4], and hypophosphatemia is an indicator of progression to brain death[

29]. Our findings emphasize this association by revealing that extreme potassium imbalances, particularly hypokalemia, worsened throughout the ICU stay and were strongly correlated with mortality. Our analysis further revealed that potassium levels at the time of patient death were significantly linked to clinical factors such as ISS, GCS, ED and ICU length of stay, and ventilation days, highlighting the critical role of potassium disturbances in severely ill patients, particularly those requiring prolonged ICU care and mechanical ventilation.

While hypokalemia is a well-recognized concern in TBI patients, the underlying mechanisms remain complex. Catecholamines, which are released in response to brain injury, have been implicated in potassium depletion, possibly through beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated stimulation of the sodium-potassium ATPase pump, which facilitates the shift of potassium from the extracellular space into the intracellular compartment [

30,

31]. Literature suggests that catecholamine levels following brain injury can be 2 to 10 times higher than in the general population, contributing to these electrolyte disturbances [

32]. Our study found that patients with severe hypokalemia and hypokalemia had lower GCS scores and higher ISS, supporting the hypothesis that an overactivated catecholamine system following brain injury may play a role in electrolyte imbalances [

27].

Furthermore, insulin is known to regulate potassium levels by stimulating the Na/K ATPase pump in various tissues, promoting cellular potassium uptake and contributing to hypokalemia [

33]. Although we did not assess whether patients received insulin or glucose infusions during hospitalization, these treatments could have influenced potassium levels. Insulin secretion and infusion are important factors in maintaining potassium homeostasis, and their potential impact on potassium imbalances in our cohort should be considered for future studies.

In conclusion, our study is consistent with and builds upon existing literature, which emphasizes the critical role of potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia, in TBI patients. Our findings reveal significant shifts in potassium levels, with extreme hypokalemia increasing from 12.03% at hospital admission to 39.14% at ICU admission, further rising to 42.71% by ICU discharge. These changes highlight the worsening of potassium imbalances during critical care and emphasize the need for careful monitoring and management of potassium levels throughout the ICU stay. Additionally, the significant correlation between severe hypokalemia, lower GCS scores, and higher ISS underscores the importance of potassium disturbances as indicators of more severe injury and poorer prognosis in TBI patients.

Implications of Study Findings

This study underscores the crucial role of potassium imbalances in the clinical outcomes of patients with severe TBI. The findings indicate that extreme hypokalemia is strongly associated with adverse outcomes, including prolonged hospital and ICU stays, increased ventilation days, and higher mortality rates. These associations suggest that potassium levels may serve as key biomarkers for predicting prognosis and guiding treatment decisions in TBI patients.

The significant correlation between potassium fluctuations and injury severity scores (e.g., AIS, ISS, and GCS) indicates that dyskalemia may signal more severe injury or an increased risk of secondary complications. Potassium imbalances may reflect underlying pathophysiological disturbances such as metabolic dysregulation, catecholamine imbalance, and inflammatory responses, which exacerbate the complexity of TBI management[

34]. Monitoring potassium levels at multiple time points, especially during admission and ICU care, could provide valuable insights into patient prognosis, enabling more informed clinical decisions.

Moreover, the strong link between potassium levels at ICU discharge and mortality highlights the potential of persistent dyskinesia as a predictor of poor outcomes. Maintaining potassium homeostasis during the acute phase of injury may help mitigate complications like arrhythmias, cardiovascular instability, and multi-organ dysfunction, which contribute to mortality[

35]. Timely identification and correction of potassium imbalances could reduce these life-threatening events and improve survival rates in severe TBI patients.

The observed relationship between potassium levels and mechanical ventilation duration further suggests that electrolyte imbalances, particularly involving potassium, may prolong ventilator support. Given potassium’s essential role in neuromuscular function, correcting imbalances could facilitate more effective weaning from mechanical ventilation, thereby reducing ICU length of stay and improving overall recovery.

These findings support the integration of regular potassium monitoring into TBI management protocols, especially for patients with severe injuries. Early detection and correction of dyskalemia could help reduce complications, shorten ICU and hospital stays, and improve survival outcomes. Further investigation into the underlying mechanisms driving these associations and targeted potassium interventions is essential to refine clinical practices and optimize patient care.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between potassium imbalances and clinical outcomes in patients with severe traumatic brain injuries (TBI). However, we acknowledge several limitations in our research design that should be considered when interpreting our findings. The study’s single-center nature limits the external validity of the results, meaning the conclusions may not apply universally across different healthcare settings or populations. This limitation is particularly significant in TBI, as different institutions may have varying treatment protocols, patient care strategies, and resource availability. Therefore, while our study adds to the body of knowledge on potassium imbalances, its findings may not fully represent practices or outcomes seen in other trauma centers or regions.

Additionally, the retrospective design of the study presents inherent challenges, particularly concerning the accuracy and completeness of the data. As the data were drawn from existing records, it is possible that errors or inconsistencies in documentation could affect the results. Despite this, potassium levels were systematically collected and consistently measured during patient hospitalization, ensuring reliable analysis of potassium fluctuations throughout the patient’s care. We analyzed key clinical outcomes such as mortality, hospital length of stay (LOS), ICU LOS, and mechanical ventilation duration, which provided a comprehensive view of the potential consequences of potassium imbalances on these critical parameters. This thorough assessment reduces concerns related to selection bias and strengthens the reliability of our findings.

A limitation of our study is the absence of long-term follow-up data, specifically neurological outcomes. While we focused on acute outcomes, such as mortality and ICU-related metrics, we did not assess the patient’s recovery in terms of cognitive function or quality of life following hospital discharge. This is a critical gap, as long-term neurological recovery is often the ultimate goal in TBI management. Future studies should aim to incorporate longer follow-up periods, perhaps extending from six months to a year post-discharge, to determine how potassium imbalances affect recovery over time. Such research would provide more comprehensive insights into the long-term impact of potassium fluctuations on TBI patients’ neurological outcomes[

26].

Another limitation was the presence of incomplete data regarding the hospital course for some patients. While potassium levels were regularly recorded during the admission and ICU admission stages, a small number of measurements were missing or not collected at key moments, such as during discharge from the ICU or hospital. This missing data could potentially affect the interpretation of the results, as we may have lacked a complete picture of the patient’s potassium levels throughout their entire hospital stay. However, the primary potassium measurements taken early in the hospitalization process are likely to be the most reliable and least affected by these gaps, as they were obtained before any intensive interventions took place.

Furthermore, our study was not a randomized controlled trial, meaning we cannot conclude causality. While the study demonstrates significant associations between potassium imbalances and clinical outcomes, we must exercise caution in inferring cause and effect. Observed relationships may be influenced by confounding factors not accounted for in our analysis. Future prospective, randomized studies are necessary to clarify the directionality and underlying mechanisms of the associations we observed. Such studies could help determine whether interventions targeting potassium normalization lead to improved outcomes in TBI patients.

An additional limitation is that we did not investigate the relationship between potassium levels and other electrolyte levels or metabolites, such as magnesium and phosphate, which could also influence clinical outcomes (Polderman KH). Given that patients with severe head injuries are more susceptible to developing multiple electrolyte imbalances, exploring these associations would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying metabolic disturbances in this population.

Insulin also plays a role in the regulation of potassium levels by stimulating the Na/K ATPase in several tissues, leading to cellular potassium uptake and contributing to hypokalemia. Basal insulin secretion is important for maintaining serum potassium concentrations[

33]. However, we did not account for whether patients received insulin infusion or glucose infusion during their hospitalization, which could have contributed to hypokalemia.

Given the findings of this study, it is important to highlight the need for continuous monitoring of potassium levels in TBI patients. Instead of assessing potassium at a few set points during hospitalization, a more dynamic approach, such as monitoring potassium levels every few hours, could offer more relevant data on how fluctuations in potassium affect patient outcomes. More frequent monitoring allows for timely adjustments to treatment plans, ensuring that potassium imbalances are addressed promptly and reducing the risk of complications such as cardiac arrhythmias or metabolic disturbances. Proactive management of potassium levels could lead to safer patient care and better clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, while our study contributes valuable insights into the role of potassium imbalances in TBI outcomes, the limitations in the design should be kept in mind. By acknowledging these limitations, we gain a better understanding of the context in which our findings should be interpreted, and we emphasize the need for further research. Future studies should focus on larger, multicenter cohorts, longer follow-up periods, and more rigorous study designs to further explore the relationship between potassium levels and clinical outcomes in TBI patients. Addressing these gaps will be essential for improving clinical practices and outcomes in this challenging patient population.

Future Perspectives

Future research in the field of electrolyte imbalances and their impact on outcomes in TBI patients could greatly benefit from a prospective, multicenter approach. Conducting studies across multiple healthcare systems would not only help validate our findings but also contribute to more robust, generalizable conclusions about the role of various electrolytes in influencing TBI outcomes. By incorporating diverse patient populations and treatment protocols from different institutions, these studies would provide a more comprehensive understanding of how electrolyte imbalances impact recovery and prognosis in TBI patients.

In addition to confirming the role of electrolytes in TBI outcomes, future research should delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that contribute to disturbances in potassium levels specifically. Trauma-induced cellular injury and systemic inflammation are thought to disrupt the body’s normal potassium regulation, yet these processes remain insufficiently understood. Further investigation into these mechanisms could lead to more targeted interventions aimed at restoring electrolyte balance and improving patient recovery.

Interventional studies will be critical in assessing the efficacy of correcting potassium imbalances in TBI patients. Research could explore whether actively managing potassium levels has a direct impact on clinical outcomes, such as reducing mortality, preventing complications, or improving long-term neurological function. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could provide valuable data on whether early intervention to normalize potassium levels has long-lasting effects on the recovery trajectory of TBI patients, including better functional and neurological outcomes over time.

Expanding the focus to include other electrolytes and biomarkers in conjunction with potassium would offer a more holistic approach to understanding the prognosis of TBI patients. Electrolyte disturbances often involve multiple elements, including sodium, phosphate, and magnesium, each of which may contribute to the clinical outcomes in unique ways. Investigating how these electrolytes interact could give researchers and clinicians a clearer picture of the complex biochemical landscape of TBI recovery. Moreover, incorporating biomarkers into these studies could help identify specific biological markers that correlate with electrolyte imbalances and offer additional insight into the body’s response to TBI.

Additionally, it would be beneficial to explore the relationship between electrolyte imbalances and specific brain injury patterns. By identifying how potassium levels correlate with particular injury types or severities, we may be able to tailor treatment strategies more effectively for different subsets of TBI patients. Furthermore, evaluating the role of pharmacologic interventions, such as diuretics, potassium supplements, or other electrolyte-modifying therapies, would help refine current clinical management strategies. Understanding how these treatments influence both electrolyte levels and patient recovery could lead to more precise and individualized care.

Finally, it would be valuable to investigate the effects of insulin therapy on electrolyte regulation, particularly potassium. Insulin administration is known to influence potassium levels, and understanding how insulin use in TBI patients affects their electrolyte balance could help guide therapeutic decisions. This research could provide additional context for managing electrolyte disturbances in patients who require insulin for blood sugar control, thereby improving overall outcomes.

In summary, investigating the interplay of electrolytes in TBI patients, alongside studying the impact of insulin therapy, will provide a more comprehensive view of how electrolyte imbalances influence recovery. A more thorough understanding of these factors could ultimately lead to better clinical management and improved long-term outcomes for patients suffering from traumatic brain injuries.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study reinforces the critical role of potassium imbalances, particularly extreme hypokalemia (<2.5 mEq/L), in predicting the clinical outcomes of patients with severe TBI. Potassium plays a fundamental role in cellular function, and its dysregulation exacerbates secondary brain injury through mechanisms such as cellular depolarization, neurotransmitter dysregulation, and impaired metabolic processes. These disturbances contribute to the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier, increasing susceptibility to life-threatening complications, including cardiac arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, and renal failure

,[

36]. Our findings demonstrate that potassium disturbances are strongly associated with prolonged hospital and ICU stays, increased mechanical ventilation requirements, and higher mortality rates. These results highlight the necessity of closely monitoring and managing potassium levels in these patients.

The temporal relationship between potassium fluctuations at key hospitalization stages—admission, ICU stay, and discharge—emphasizes the need for continuous monitoring. Notably, persistent dyskalemia at hospital discharge is strongly associated with increased mortality risk, underscoring the prognostic significance of potassium homeostasis in long-term patient outcomes. The progression of extreme hypokalemia throughout hospitalization, especially in the ICU phase, further emphasizes the need for intensive care protocols that address electrolyte imbalances promptly to mitigate their negative impact on patient recovery.

Our results align with previous research, which has shown that dyskalemia, particularly hypokalemia, is both prevalent and clinically significant in TBI patients. By observing the relationships between potassium fluctuations and injury severity, it is clear that potassium disturbances are not merely secondary effects of trauma but important indicators of injury severity and potential complications. The significant association between severe hypokalemia and lower Glasgow Coma Scores (GCS) further supports potassium’s role as a prognostic marker, suggesting that correcting these imbalances could improve clinical outcomes and reduce mortality rates.

While our study provides valuable insights into the implications of potassium imbalances in TBI, it is not without limitations. The retrospective nature of this study introduces potential biases related to data completeness and prevents us from establishing causality. While the observed associations between potassium imbalances and adverse outcomes are statistically significant, further research is necessary to elucidate the underlying physiological mechanisms. The lack of long-term follow-up data on neurological and functional recovery limits the broader applicability of these findings. Future prospective multicenter studies with rigorous data collection and extended follow-up periods are essential to validate these associations and determine the causal impact of potassium fluctuations on TBI outcomes.

Targeted therapeutic interventions aimed at correcting dyskalemia represent a promising avenue for improving patient outcomes. Prospective clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of potassium normalization strategies could provide valuable insights into optimizing electrolyte management in TBI patients. Additionally, exploring the interplay between potassium and other electrolytes, as well as the biochemical pathways governing potassium homeostasis, may yield novel approaches to mitigating secondary brain injury. Ultimately, the integration of potassium monitoring into routine clinical practice could improve patient outcomes and guide more personalized treatment strategies for TBI patients, contributing to the advancement of precision medicine in the management of severe TBI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—B.S.; writing—original draft preparation—B.S. and M.H.; writing—review and editing—B.S., J.W., K.T., S.B., S.P., J.D., J.M., N.D.B., G.A., and Z.S., figures and table, B.S. and U.G.; supervision—B.S.; project administration—B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no grant support or financial relationship for this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was approved by the IRB at Elmhurst Facility on 5 July 2024, with IRB number 24-12-092-05G.

Informed Consent Statement

Retrospective analysis was performed on anonymized data, and informed consent was not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data was requested from the Elmhurst Trauma registry and extracted using electronic medical records after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board at our facility (Elmhurst Hospital Center).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- JG., Georges A. Booker. "Traumatic Brain Injury." (2020).

- TSA., Syed N. "Recent advances and future trends in traumatic brain injury." Emerg Med Open Access. (2015; 05. ).

- Ahmed S, Venigalla H, Mekala HM, Dar D, Hassan M, Ayub S. "TBIand neuropsychiatric complications." Indian J Psychol. Med (2017): 39: 114e121.

- X. Wu et. al"Prevalence of severe hypokalemia in patients with traumatic brain injury." Injury, Int. J. Care Injured (2015): 35-41.

- Vinas-Rios JM, sanchez-Aguilar M, Sanchez-Rodriguez JJ, et al. "Hypocalcemia as a prognostic factor of early mortality in moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. ." Neurol Res. (2014; ): 36:102-106. [CrossRef]

- Mwachaka P, Amayo A, Mwang’ombe N, Kitunguu P. "Association between serum sodium abnormalities and clinical radiologic parameters in severe traumatic brain injury." Ann Afr Surg. (2021; ): 18:55-162. [CrossRef]

- Micah Ngatuvai, Brian Martinez, Matthew Sauder et al. "Traumatic brain injury, Electrolyte levels, and associated outcomes: A systemic Review." Journal of Surgical Research (2023): (289) 106-115.

- Polderman KH, Bloemers FW, Peerdemann Sm, Girbes AR. "Hypomagesemia and hypophosphatemia at admission in patients with severe head injury. ." Critical Care Med. (2000): 28: 2022-5. [CrossRef]

- Maggiore U, Picette E, Antonucci, et al. "The relation between the incidence of hypernatremia and mortality in patients with severe TBI." Crit Care. (2009; 13: R110. ).

- Rodriguez-Trivino CY, Torres Castro I, Duenas Z. "Hypochloremia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: as a possible risk factor for increased mortality. ." World Neurosurg. (2019; ): S 1878-S8750. [CrossRef]

- Kolmodin L, Sekhon MS, Henderson WR, Turgeon AF, Grisedat DE. "Hypernatremia in patients with severe traumatic brain injury: a systemic review. ." Ann Intensive Care. (2013; ): 3: 35. [CrossRef]

- Reid JL, Whyte KF, Struthers AD. "Epinephrine-induced hypokalemia: the role of beta-adrenoceptors. ." American Journal of Cardiology (1986): 25: 23F-27F. [CrossRef]

- Suman, S.: Kumar, N. and Y, et al. Singh. "Evaluation of Serum Electrolyte in TBIPatients;" Prospective Randomized Observational Study (Journal Anesthesia Critical Care Open Access): 2016.

- Perkins, R., Aboudara, M. and K. Holcomb, J. Abbott. "Resuscitative Hyperkalemia in Non-Crush Trauma:" A Prospective, Observational Study. Clinical Journal of American Soc. Nephrology (2007): 2, 313-319.

- Schaefer, M., et al. "Excessive Hypokalemia and Hyperkalemia Following Head Injury. ." Intensive Care Med. (1995, ): 21, 235-237. [CrossRef]

- Ayach, T., et al. "Postoperative Hyperkalemia. ." Eur, J, Intern. Med (2015,): 26, 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G. and F. Goldner. "Hypernatremia, Azotemia, and Acidosis after Cerebral Injury. ." Americam Journal Medicine (1957): 23, 543-553.

- Beal, A., et al. "Hypokalemia Following Trauma. ." Shock (2002): 18, 107-110. [CrossRef]

- Xing, W., et al. "Prevalence of Severe Hypokalemia in Patients with Traumatic Brain Injury. ." Injury (2015): 46, 35-41.

- Wiesel, O., et al. "Dyskalemia Following Head Trauma: Case Report and Review of the Literature." Trauma (2009): 67. [CrossRef]

- Săcărescu A, Turliuc MD. "Electrolyte Imbalance in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: Insights from First 24 hours. ." Clinical Practice. (2024 August 30): 14 (5): 1767-1778. [CrossRef]

- Cholakkal S, Basheer N, Alapat J. Kuruvilla R,. "A prospective study on hyponatremia in traumatic brain injury. ." Indian Journal Neurotrauma. (2016): 13: L094-L100.

- Yumoto T, Sato K, Ugawa T, Ichiba S, Ukike Y. "Prevalence, risk factors, and short-term consequences of traumatic brain injury-associated hyponatremia. ." Acta Med Okayama. (2015): 69: 213-218. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Baltazar GA, Pate A, Akella K, Chandrasekhar A. "Hyponatremia on initial Presentation correlates with suboptimal outcomes after traumatic brain injury. ." Am Surg. (2017; 83: e126-e128. ). [CrossRef]

- Montford JR, Linas S. "How Dangerous is Hyperkalemia?" J Am Soc Nephrology (2017 NOV): 28 (11): 3155-3165.

- B. Sharma, W. Jiang, M.M. Hasan, et al. "Natremia Significantly Influences the Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury." Diagnostics (Jan 7;15(2):125. PMID: 39857008; PMCID: PMC11764417). [CrossRef]

- Clifton GL, Ziegler MG, Grossman RG. "Circulating catecholamines and sympathetic activity after head injury. ." Neurosurgery (1981; 8:10-4. ).

- Fisher J. Magid N, Kallman C, Fanucchi M, Klein L, McCarthy D, et al. "Respiratory illness and hypophosphatemia. ." Chest (1983; 83: 504-8. ).

- Maniakhina LE, Muir SM, Tackett N, Johnson D, Mentzer CJ, Mount MG. "Significant Hypophosphatemia in Predictive of Brain Death in Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. ." The American Surgeon. (2023): 7: 3278-3280. [CrossRef]

- Brown MJ, Brown DC, Murphy MB. "Hypokalemia from beta2-receptor stimulation by circulating epinephrine. ." N Engl Journal of Medicine (1983): 309: 1414-9. [CrossRef]

- Epstein FH, Rosa RM. "Adrenergic control of serum potassium." New England Journal of Medicine. (198; ): 309:1450-1.

- Hinson He, Sheth KN. "Manifestations of the hyperadrenergic state after acute brain injury." Current Opinion in Critical Care (2012): 18: 139-45. [CrossRef]

- Gabow PA, Johnson AM, Johnson AM, Kaehny WD, Kimberling WJ, Lezotte DC, Duley IT, et al. "Factors affecting the progression of renal disease in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease." Kidney International (1992; 41: 1311-9. ). [CrossRef]

- Cronin D, Kaliaperumal C, Kumar R, Kaar G. "Dyskalemia following diffuse axonal injury: Case Report and review of the literature. ." BMJ Case Report (2012: 10: 2012). [CrossRef]

- Bilotta F. Giovannini F, Aghilone F, Stazi E, Titi L, Zeppa IO, et al. "Potassium-sparing diuretics as an adjunct to mannitol therapy in neurocritical care patients with cerebral edema: effects on potassium homeostasis and cardiac arrhythmias. ." Neurocritical care. (2012; ): 16: 280-5. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, G. and F. Goldner. "Hypernatremia, Azotemia, and Acidosis after Cerebral Injury. ." Americam Journal Medicine (1957): 23, 543-553.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).