Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

2.1. Experimental Design

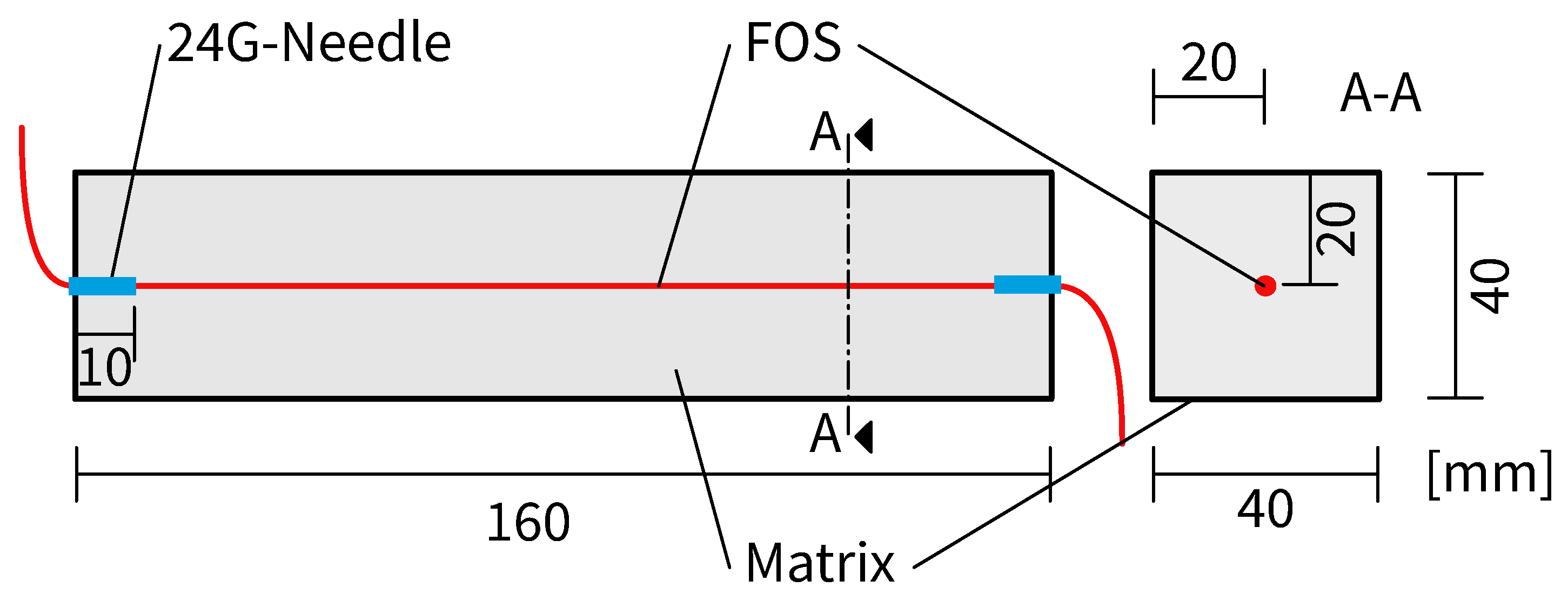

- The mold and FOS were cleaned with isopropyl alcohol. The purpose of this step is to remove contaminants such as oils, release agents, or dust particles that may weaken the bond to ensure optimal adhesion between the matrix and the sensor for improved measurement accuracy.

- The FOS was fixed in the mold using cannula needles (24G). The needles are used to protect the FOS, especially in the zone between the matrix and the mold, and to ensure safe repositioning between and after compacting using the shock table.

- FOS assembly with pigtail and termination.

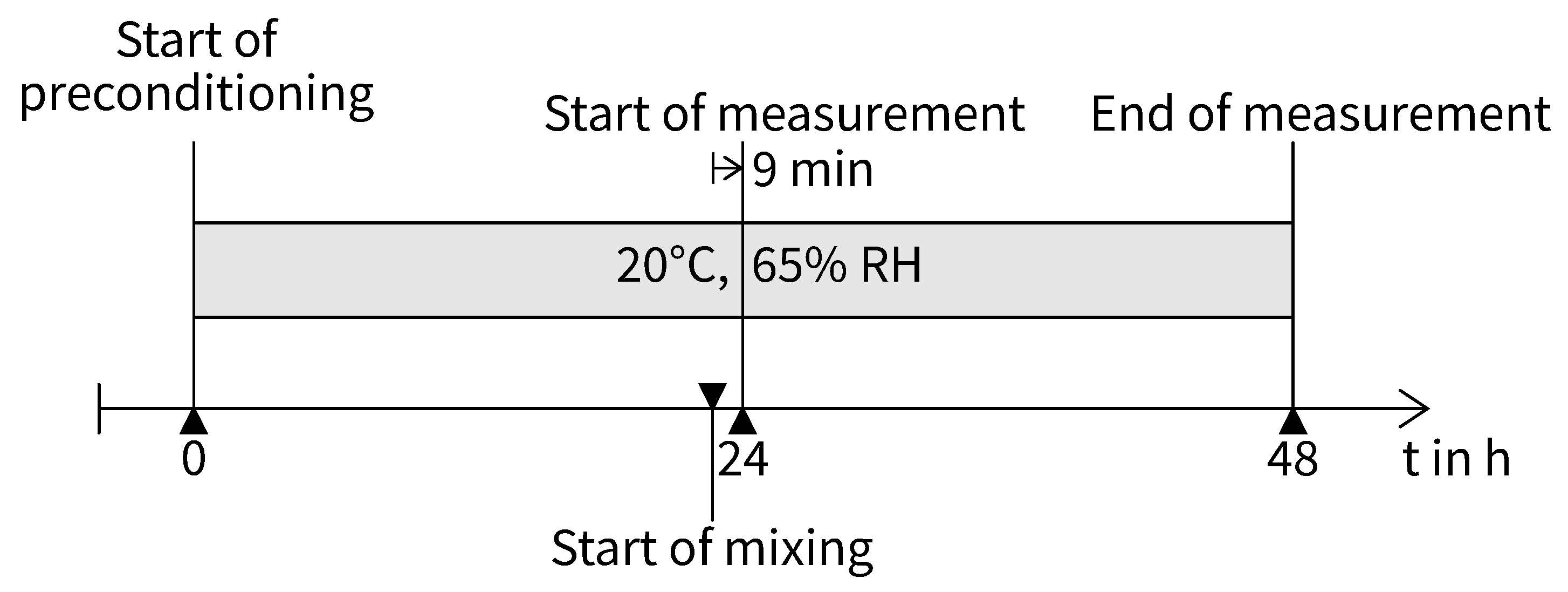

- The mold with the FOS, the mix components (cement, deionized water and CEN standard sand according to EN 196-1:2016), the mixer including trough and agitator, and the shock table were stored for 24 under controlled environmental conditions (20 °C, 65% rH). This ensured stabilization of the initial conditions before the start of the experiment.

- Before the mortar was applied, the FOS was tared to eliminate any offsets.

- The mortar has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of EN 196-1:2016.

- To avoid damaging the sensor or changing its position, the first layer of the mortar was carefully placed in the mold.

- After filling the first and second layers, the position of the sensor was checked by briefly tightening it. The two layers of mortar were compacted by 60 impacts each on a shock table according to EN 196–1:2016.

- The filled mold was placed on a roller track and covered with a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) sheet to prevent the mortar from drying.

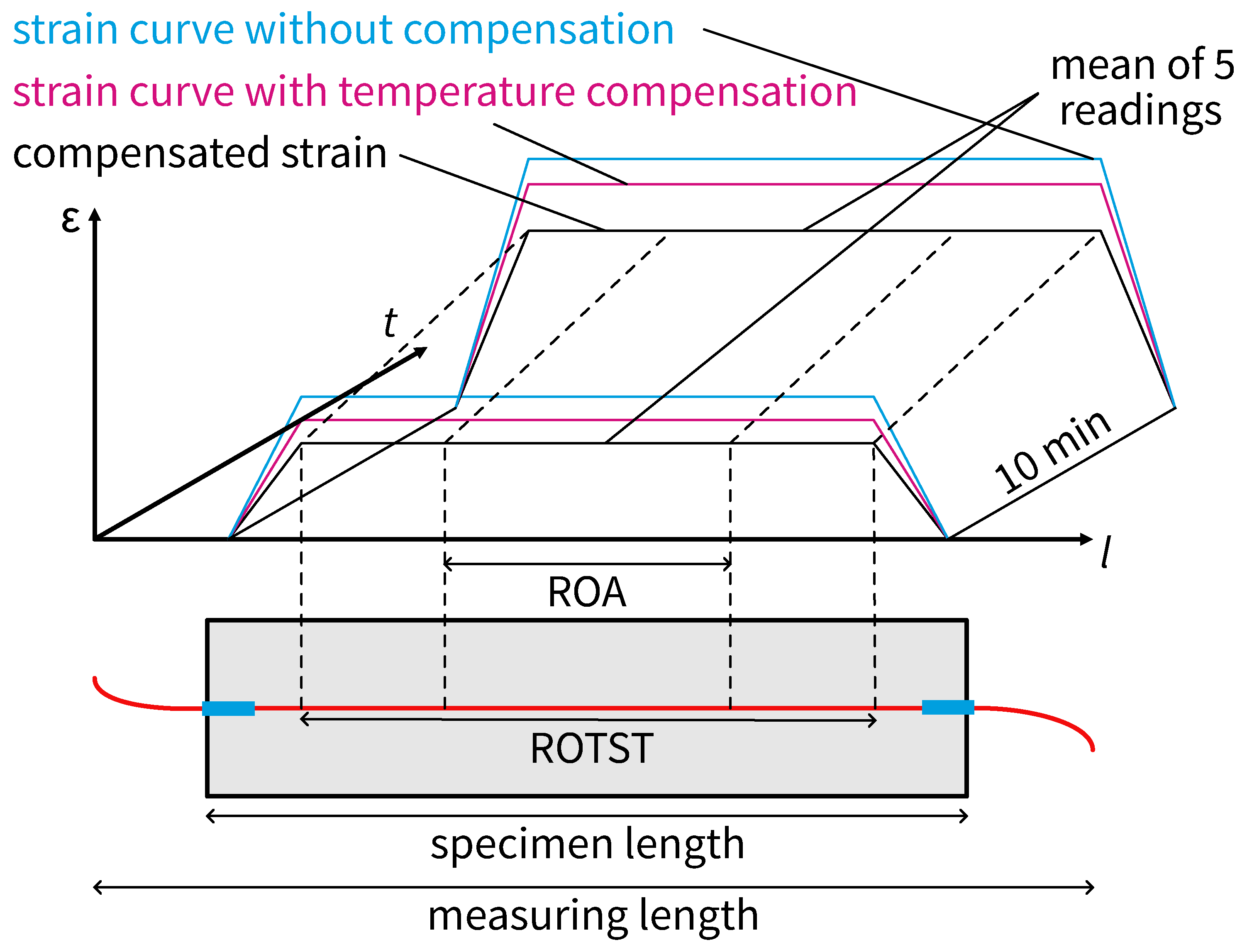

- Start of measurement nine minutes after mbegin of mixing with a duration of 24 and recording of five readings at a rate of 1 every ten minutes.

2.2. Mortar Mixture, Application Material and Fiber Types

3. Results

3.1. Processing of Measurement Results

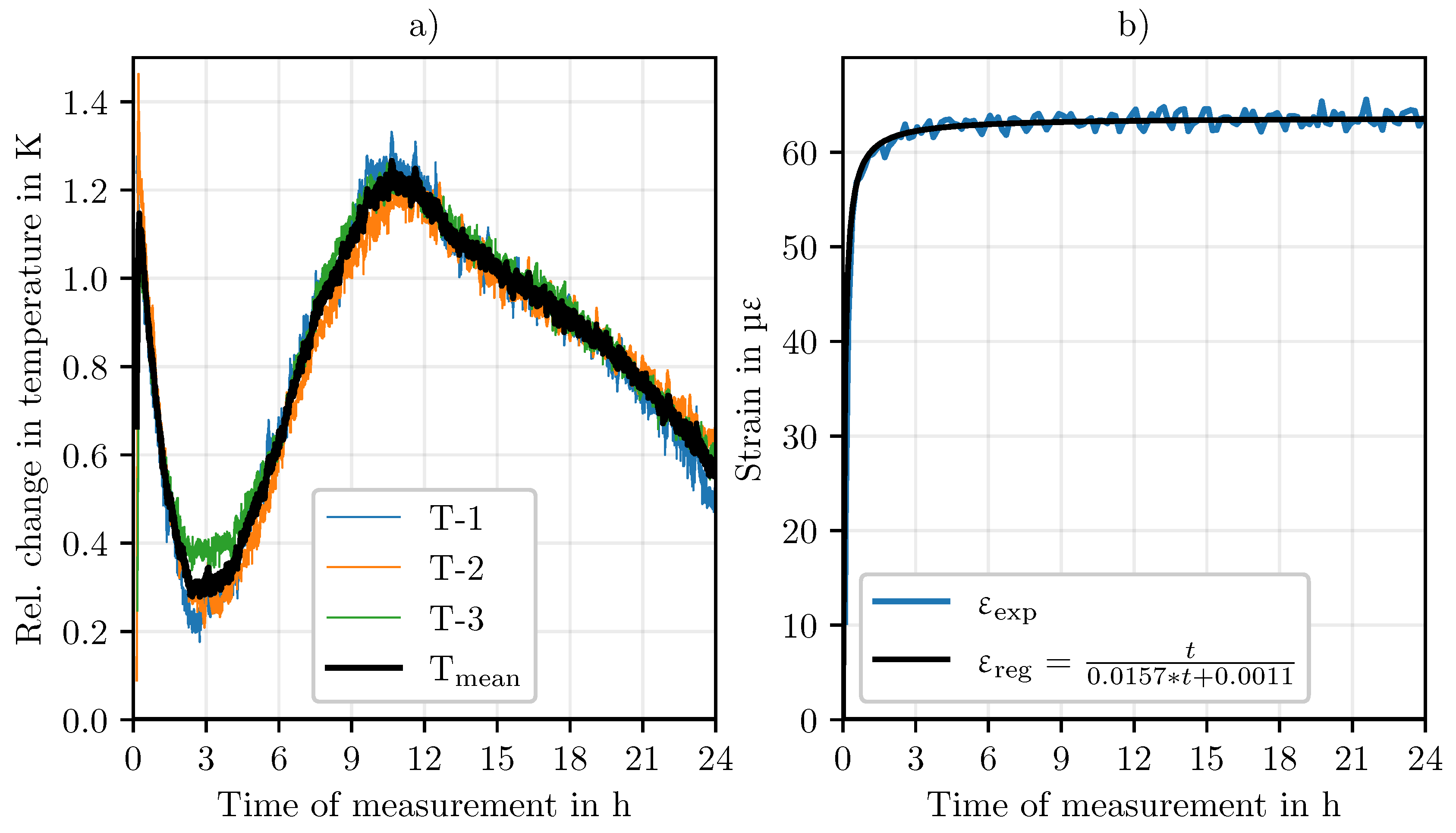

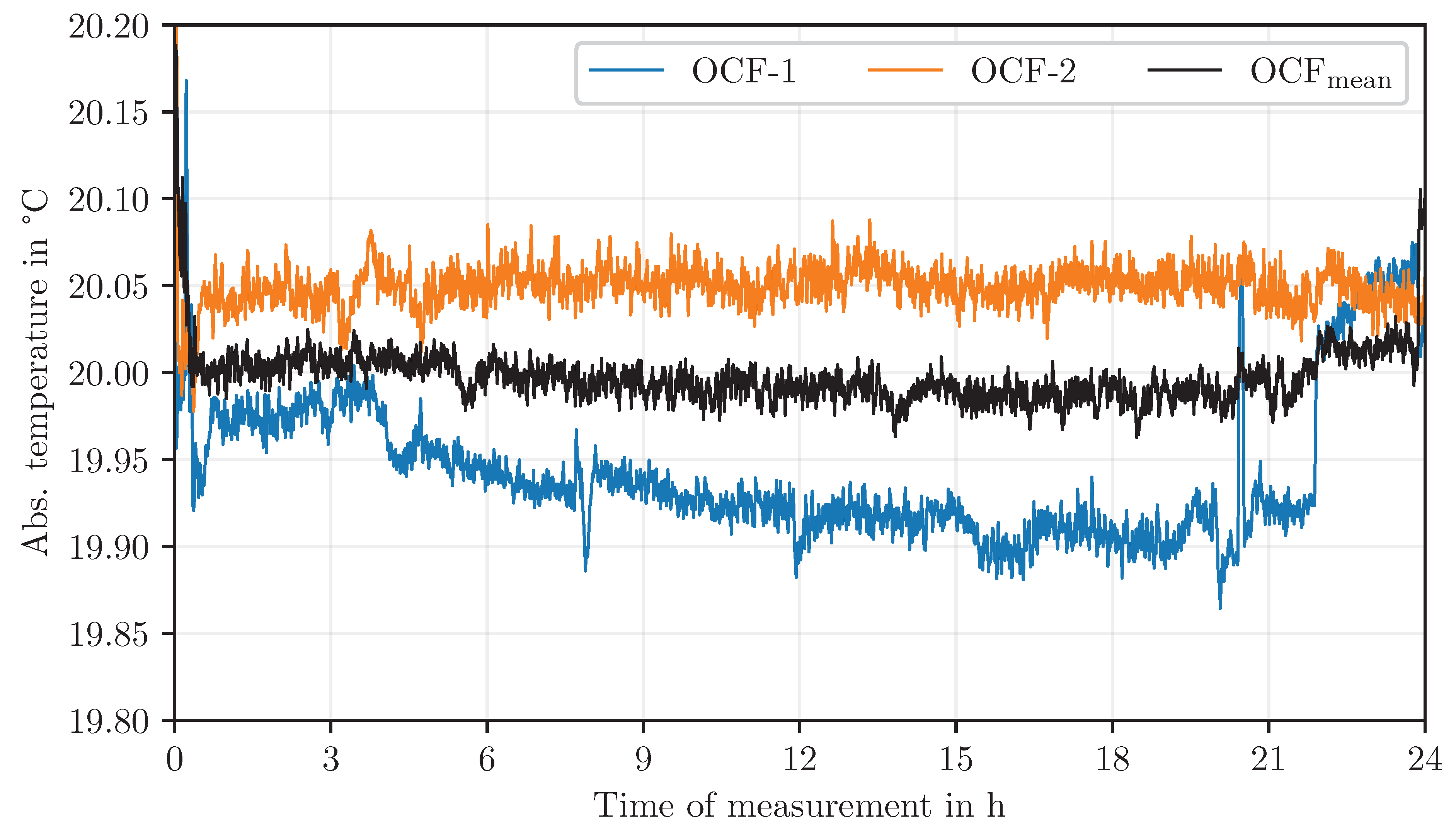

3.2. Compensation for Temperature Effects

3.3. Compensation for Moisture Effects

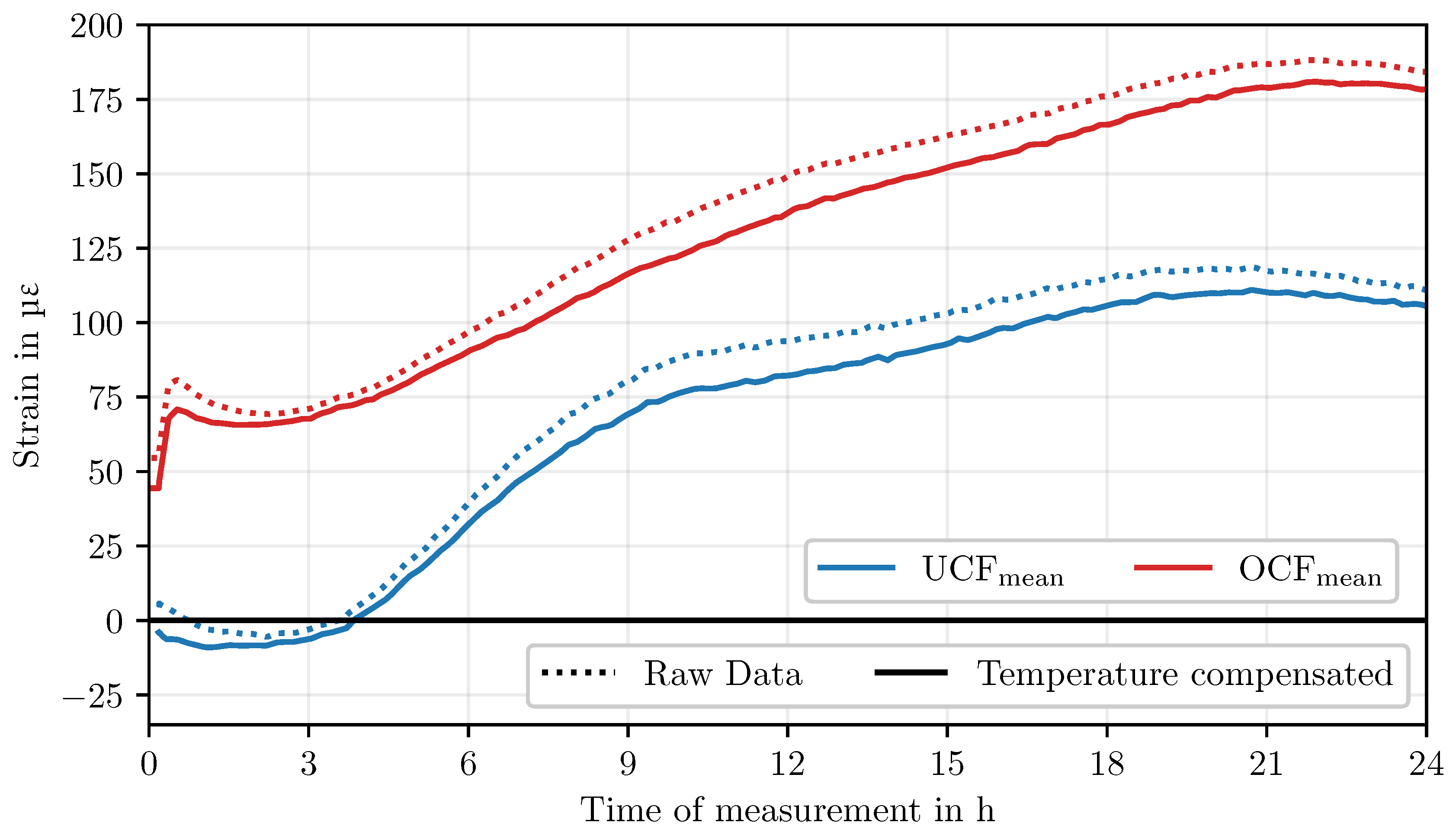

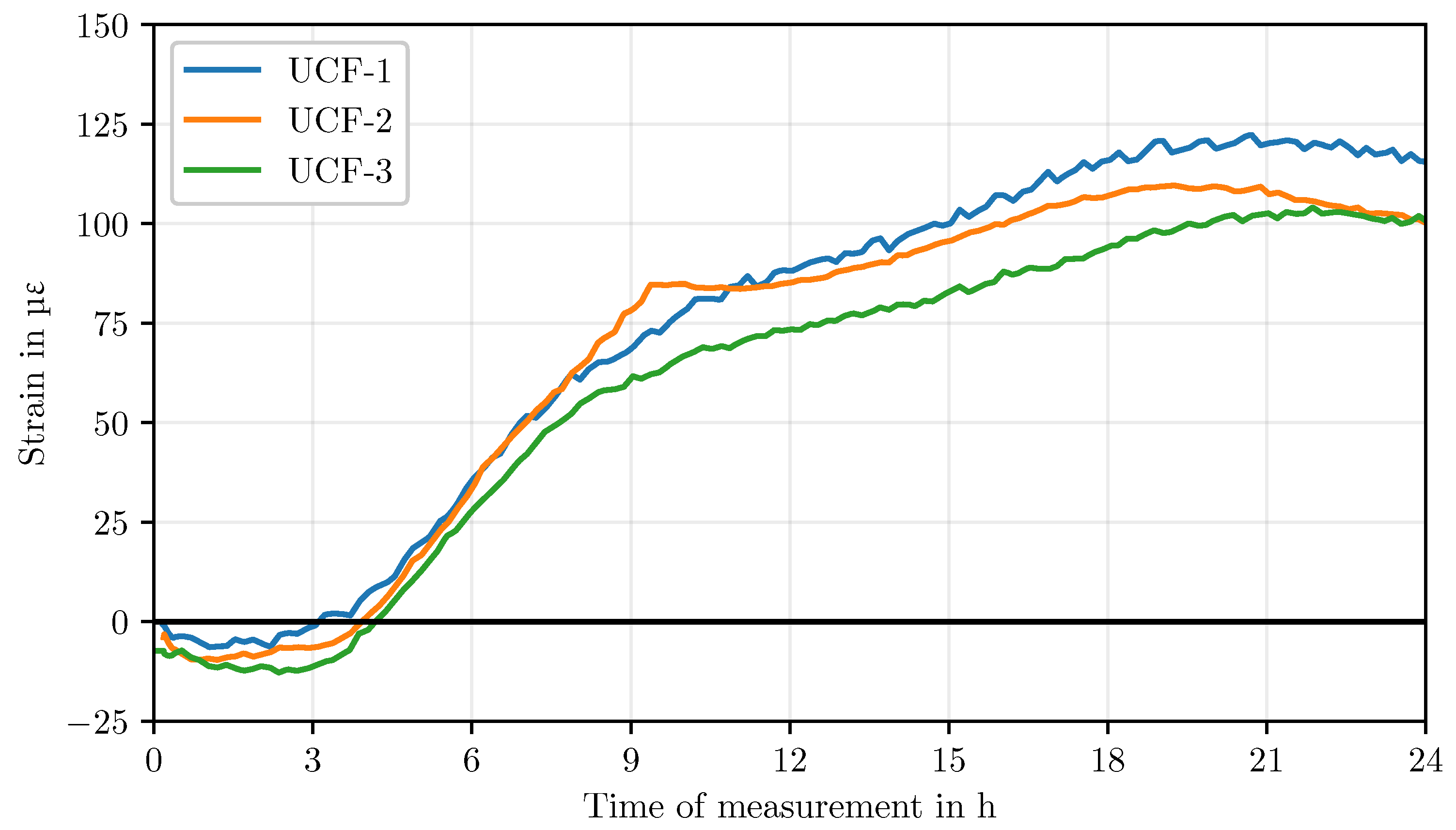

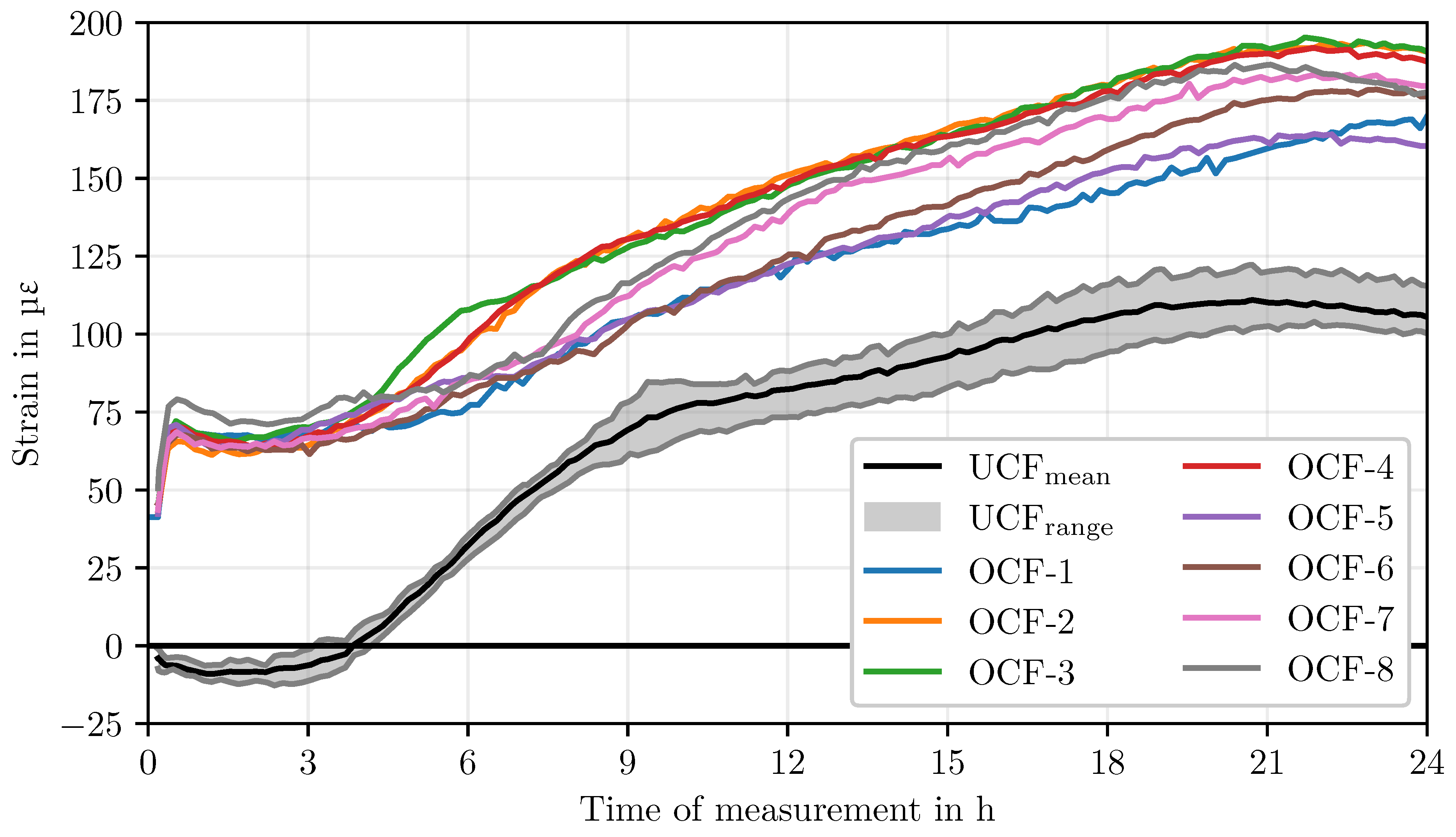

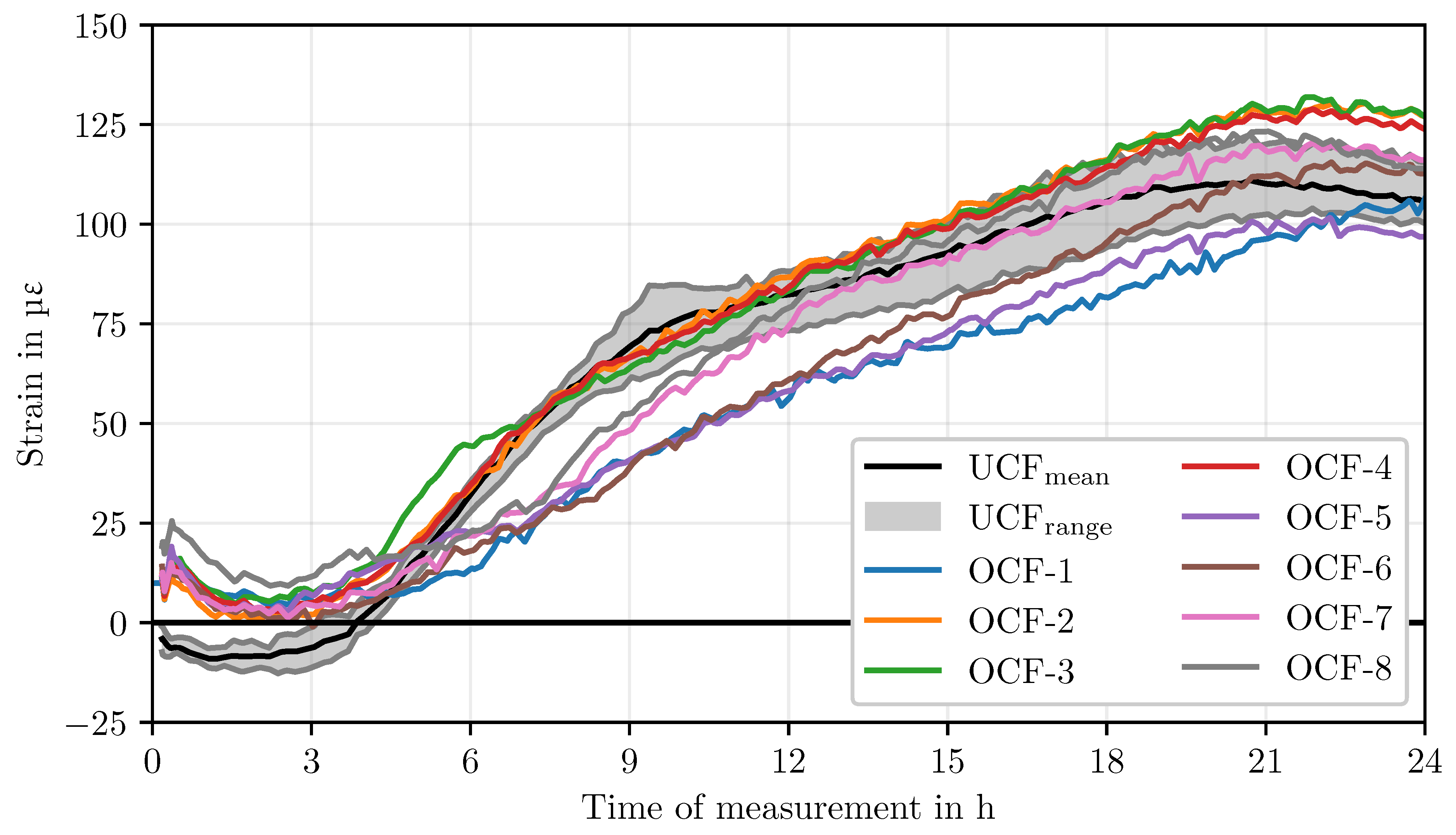

3.4. Deformation Measurement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samiec, D. Distributed fibre-optic temperature and strain measurement with extremely high spatial resolution. Photonik International 2012, 1, 10–13.

- Weisbrich, M.; Holschemacher, K.; Bier, T. Validierung verteilter faseroptischer Sensorik zur Dehnungsmessung im Betonbau. Beton- und Stahlbetonbau 2021, 116, 648–659. [CrossRef]

- Bado, M.F.; Casas, J.R. A Review of Recent Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors Applications for Civil Engineering Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2021, 21, 1818. [CrossRef]

- Barrias, A.; Rodriguez, G.; Casas, J.R.; Villalba, S. Application of distributed optical fiber sensors for the health monitoring of two real structures in Barcelona. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2018, 14, 967–985. [CrossRef]

- Moser, F.; Lienhart, W.; Woschitz, H.; Schuller, H. Long-term monitoring of reinforced earth structures using distributed fiber optic sensing. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring 2016, 6, 321–327. [CrossRef]

- Inaudi, D.; Glisic, B. Application of distributed fiber optic sensory for SHM. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Structural Health Monitoring of Intelligent Infrastructure, SHMII 2005, 2006, pp. 163–169.

- Becks, H.; Baktheer, A.; Marx, S.; Classen, M.; Hegger, J.; Chudoba, R. Monitoring concept for the propagation of compressive fatigue in externally prestressed concrete beams using digital image correlation and fiber optic sensors. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials & Structures 2023, 46, 514–526. [CrossRef]

- Berrocal, C.G.; Fernandez, I.; Rempling, R. Crack monitoring in reinforced concrete beams by distributed optical fiber sensors. Structure and Infrastructure Engineering 2021, 17, 124–139. [CrossRef]

- Chapeleau, X.; Bassil, A. A general solution to determine strain profile in the core of distributed fiber optic sensors under any arbitrary strain fields. Sensors 2021, 21, 5423. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, O.; Thoma, S.; Crepaz, S. Quasikontinuierliche faseroptische Dehnungsmessung zur Rissdetektion in Betonkonstruktionen. Beton- und Stahlbetonbau 2019, 114, 150–159. [CrossRef]

- Henault, J.M.; Quiertant, M.; Delepine-Lesoille, S.; Salin, J.; Moreau, G.; Taillade, F.; Benzarti, K. Quantitative strain measurement and crack detection in RC structures using a truly distributed fiber optic sensing system. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 37, 916–923. [CrossRef]

- Herbers, M.; Richter, B.; Gebauer, D.; Classen, M.; Marx, S. Crack monitoring on concrete structures: Comparison of various distributed fiber optic sensors with digital image correlation method. Structural Concrete 2023, pp. 6123–6140. [CrossRef]

- Kishida, K.; Imai, M.; Kawabata, J.; Guzik, A. Distributed Optical Fiber Sensors for Monitoring of Civil Engineering Structures. Sensors 2022, 22, 4368. [CrossRef]

- Lienhart, W.; Buchmayer, F.; Klug, F.; Monsberger, C.M. Distributed Fiber Optic Sensing on a Large Tunnel Construction Site: Increased Safety, More Efficient Construction and Basis for Condition-Based Maintenance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Infrastructure and Construction 2019 (ICSIC), Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 595–604. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Higuera, J.M.; Cobo, L.R.; Incera, A.Q.; Cobo, A. Fiber Optic Sensors in Structural Health Monitoring. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2011, 29, 587–608. [CrossRef]

- Minardo, A.; Persichetti, G.; Testa, G.; Zeni, L.; Bernini, R. Long term structural health monitoring by Brillouin fibre-optic sensing: a real case. Journal of Geophysics and Engineering 2012, 9, S64–S69. [CrossRef]

- Monsberger, C.M.; Lienhart, W. Distributed Fiber Optic Shape Sensing of Concrete Structures. Sensors 2021, 21, 6098. [CrossRef]

- Monsberger, C.M.; Lienhart, W. Distributed fiber optic shape sensing along shotcrete tunnel linings: Methodology, field applications, and monitoring results. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring 2021, 11, 337–350. [CrossRef]

- Zdanowicz, K.; Gebauer, D.; Koschemann, M.; Speck, K.; Steinbock, O.; Beckmann, B.; Marx, S. Distributed fiber optic sensors for measuring strains of concrete, steel, and textile reinforcement: Possible fields of application. Structural Concrete 2022, 23, 3367–3382. [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, H.; Rajeev, P.; Gad, E. Distributed optical fibre sensor for infrastructure monitoring: Field applications. Optical Fiber Technology 2021, 64, 102577. [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.Y.; Wan, K.T.; Inaudi, D.; Bao, X.; Habel, W.; Zhou, Z.; Ou, J.; Ghandehari, M.; Wu, H.C.; Imai, M. Review: optical fiber sensors for civil engineering applications. Materials and Structures 2013, 48, 871–906. [CrossRef]

- Weisbrich, M.; Holschemacher, K.; Bier, T. Comparison of different fiber coatings for distributed strain measurement in cementitious matrices. Journal of Sensors and Sensor Systems 2020, 9, 189–197. [CrossRef]

- Weisbrich, M. Verbesserte Dehnungsmessung im Betonbau durch verteilte faseroptische Sensorik. Phd thesis, Technische Universität Bergakademie Freiberg, 2020.

- Weisbrich, M.; Holschemacher, K. Comparison between different fiber coatings and adhesives on steel surfaces for distributed optical strain measurements based on Rayleigh backscattering. Journal of Sensors and Sensor Systems 2018, 7, 601–608. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hao, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiao, J.; Poon, C.S. Advanced measurement techniques for plastic shrinkage and cracking in 3D-printed concrete utilising distributed optical fiber sensor. Additive Manufacturing 2023, 74, 103722. [CrossRef]

- Kayondo, M.; Combrinck, R.; Boshoff, W. State-of-the-art review on plastic cracking of concrete. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 225, 886–899. [CrossRef]

- Holt, E.E.; Janssen, D.J. Influence of Early Age Volume Changes on Long-Term Concrete Shrinkage. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 1998, 1610, 28–32. [CrossRef]

- Ghourchian, S.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Lura, P. A practical approach for reducing the risk of plastic shrinkage cracking of concrete. RILEM Technical Letters 2017, 2, 40–44. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Dao, V.; Lura, P. Autogenous deformation and coefficient of thermal expansion of early-age concrete: Initial outcomes of a study using a newly-developed Temperature Stress Testing Machine. Cement and Concrete Composites 2021, 119, 103997. [CrossRef]

- Gowripalan, N., Autogenous Shrinkage of Concrete at Early Ages. In ACMSM25; Springer Singapore, 2019; pp. 269–276. [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Lothenbach, B. Cement hydration mechanisms through time – a review. Journal of Materials Science 2023, 58, 9805–9833. [CrossRef]

- Michaëlis, W. The Hardening Process of Hydraulic Cements. Cement and Engineering News 1907, pp. 1–29.

- Chetalier, H.L. Experimental Researches on the Constitution of Hydraulic Mortars; McGraw-Hill Publishing Co.: New York, 1905.

- Powers, T.C. Some aspects of the hydration of Portland cement. Technical Report 125, J. Port. Cem. Assoc. Res. Dev. Lab., 1961.

- Scrivener, K.; Ouzia, A.; Juilland, P.; Kunhi Mohamed, A. Advances in understanding cement hydration mechanisms. Cement and Concrete Research 2019, 124, 105823. [CrossRef]

- Moses, P.; Perumal, S.B. Hydration of Cement and its Mechanisms. IOSR Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering 2016, 16, 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Aghdam, S.; Masoero, E.; Rasoolinejad, M.; Bažant, Z.P. Century-long expansion of hydrating cement counteracting concrete shrinkage due to humidity drop from selfdesiccation or external drying. Materials and Structures 2019, 52. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S. Delayed ettringite formation - Processes and problems. Cement and Concrete Composite 1996, 18, 205–215. [CrossRef]

- Bjøntegaard, Ø. and Hammer, T.A and Sellevold, E.J.. On the measurement of free deformation of early age cement paste and concrete. Cement and Concrete Composites 2004, 26, 427–435. [CrossRef]

- Mohr, B.; Hood, K. Influence of bleed water reabsorption on cement paste autogenous deformation. Cement and Concrete Research 2010, 40, 220–225. [CrossRef]

- Wyrzykowski, M.; Hu, Z.; Ghourchian, S.; Scrivener, K.; Lura, P. Corrugated tube protocol for autogenous shrinkage measurements: review and statistical assessment. Materials and Structures 2016, 50. [CrossRef]

- Vosoughi, P.; Taylor, P.; Najimi, M.; Horton, R. Effect of Exposure Conditions and Internal Curing on Pore Water Potential Development in Cement-Based Materials. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2020, 2675, 184–191. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O.M.; Hansen, P.F. Autogenous deformation and RH-change in perspective. Cement and Concrete Research 2001, 31, 1859–1865. [CrossRef]

- Hammer, T.; Bjøntegaard, Ø.; Sellevold, E. Measurement methods for testing of early age autogenous strain. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Conference on Early Age Cracking in Cementitious Systems. RILEM Publications SARL, 2003, pp. 217–228.

- Kurup, D.S.; Mohan, M.K.; Van Tittelboom, K.; De Schutter, G.; Santhanam, M.; Rahul, A. Early-age shrinkage assessment of cementitious materials: A critical review. Cement and Concrete Composites 2024, 145, 105343. [CrossRef]

- Al-Amoudi, O.; Maslehuddin, M.; Shameem, M.; Ibrahim, M. Shrinkage of plain and silica fume cement concrete under hot weather. Cement and Concrete Composites 2007, 29, 690–699. [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Lei, D.; Zhu, F.; Bai, P.; He, J. Experimental research on aggregate restrained shrinkage and cracking of early-age cement paste. Cement and Concrete Research 2023, 172, 107246. [CrossRef]

- Ghourchian, S.; Wyrzykowski, M.; Baquerizo, L.; Lura, P. Susceptibility of Portland cement and blended cement concretes to plastic shrinkage cracking. Cement and Concrete Composites 2018, 85, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, A.; Schindler, A.K. Plastic-sleeve test method to measure autogenous and drying shrinkage in paste, mortar, and concrete: Test Results. Measurement 2024, 237, 115138. [CrossRef]

- Slowik, V.; Schlattner, E.; Klink, T. Experimental investigation into early age shrinkage of cement paste by using fibre Bragg gratings. Cement & Concrete Composites 2004, 26, 473–479. [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.C.; Childs, P.A.; Berndt, R.; Macken, T.; Peng, G.D.; Gowripalan, N. Simultaneous measurement of shrinkage and temperature of reactive powder concrete at early-age using fibre Bragg grating sensors. Cement and Concrete Composites 2007, 29, 490–497. [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.S.; Silva, F.; Mahfoud, T.; Khelidj, A.; Brientin, A.; Azevedo, A.; Delgado, J.; de Lima, A.B. On the Use of Embedded Fiber Optic Sensors for Measuring Early-Age Strains in Concrete. Sensors 2021, 21, 4171. [CrossRef]

- Francinete, P.; da Silva, E.F.; de Mendonça Lopes, A.N., Comparative Study Between Strain Gages for Determination of Autogenous Shrinkage. In 3rd International Conference on the Application of Superabsorbent Polymers (SAP) and Other New Admixtures Towards Smart Concrete; Springer International Publishing, 2019; pp. 114–122. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Mao, Z.; Cao, Z.; Huang, X.; Deng, M. Effect of Different Fineness of Cement on the Autogenous Shrinkage of Mass Concrete under Variable Temperature Conditions. Materials 2023, 16, 2367. [CrossRef]

- Weicken, H. Experimentelle Methodik zur Bestimmung des autogenen Schwindverhaltens von Hochleistungsbetonen. Phd thesis, Institut für Baustoffe, Universität Hannover, 2019.

- Eppers, S.; Müller, C. The shrinkage cone method for measuring the autogenous shrinkage - an alternative to the corrugated tube method. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Conference on Use of Superabsorbent Polymers and Other New Additives in Concrete. RILEM Publications SARL, 2010, pp. 67–76.

- Kucharczyková, B.; Kocáb, D.; Rozsypalová, I.; Karel, O.; Misák, P.; Vymazal, T. Measurement and evaluation proposal of early age shrinkage of cement composites using shrinkage-cone. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 2018, 379, 012038. [CrossRef]

- Sant, G.; Lura, P.; Weiss, J. Measurement of Volume Change in Cementitious Materials at Early Ages: Review of Testing Protocols and Interpretation of Results. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2006, 1979, 21–29. [CrossRef]

- Lura, P.; Jensen, O.M. Measuring techniques for autogenous strain of cement paste. Materials and Structures 2006, 40, 431–440. [CrossRef]

- Mejlhede Jensen, O.; Freiesleben Hansen, P. A dilatometer for measuring autogenous deformation in hardening portland cement paste. Materials and Structures 1995, 28, 406–409. [CrossRef]

- Bjøntegaard, Ø and Hammer, T.A.. RILEM TC 195-DTD: MOTIVE AND TECHNICAL CONTENT. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Conference on Volume Changes of Hardening Concrete: Testing and Mitigation. Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2006.

- Weisbrich, M.; Messerer, D.; Holzer, F.; Trommler, U.; Roland, U.; Holschemacher, K. The Impact of Liquids and Saturated Salt Solutions on Polymer-Coated Fiber Optic Sensors for Distributed Strain and Temperature Measurement. Sensors 2024, 24, 4659. [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.Y. Interfacial changes of optical fibers in the cementitious environment. Journal of Materials Science 2000, 35, 6197–6208. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, G.; Wang, G. Effect of the plastic coating on strain measurement of concrete by fiber optic sensor. Measurement 2003, 34, 215–227. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhou, L. Sensitivity coefficient evaluation of an embedded fiber-optic strain sensor. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 1998, 69, 5–11. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.S.; Sr., H.L.; Ren, L.; Song, G. Strain transferring analysis of fiber Bragg grating sensors. Optical Engineering 2006, 45, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.N.; Zhou, G.D.; Ren, L.; Li, D.S. Strain transfer coefficient analyses for embedded fiber bragg grating sensors in different host materials. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 2009, 135, 1343–1353. [CrossRef]

- Luna Innovations Incorporated. OPTICAL DISTRIBUTED SENSOR INTERROGATOR (Model ODiSI B), 2013.

- Innovative Sensor Technology IST AG. TSic 506F TO92 Temperature Sensor IC.

- SCHWENK Zement KG. CEM I 42,5 R Portland Cement, 2012.

- FBGS International N.V.. DTG coating Ormocer®-T for temperature sensing applications, 2015.

- Wyrzykowski, M.; Lura, P. Moisture dependence of thermal expansion in cement-based materials at early ages. Cement and Concrete Research 2013, 53, 25–35. [CrossRef]

- Texas Instruments Incorporated. TMP117 High-Accuracy, Low-Power, Digital Temperature Sensor, 2022.

- Sensirion AG. Datasheet – SHT4x - 4th Gen. Relative Humidity and Temperature Sensor, 2024.

- Bjøntegaard, Ø and Hammer, TA. RILEM TC 195-DTD: MOTIVE AND TECHNICAL CONTENT. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Conference on Volume Changes of Hardening Concrete: Testing and Mitigation. Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2006.

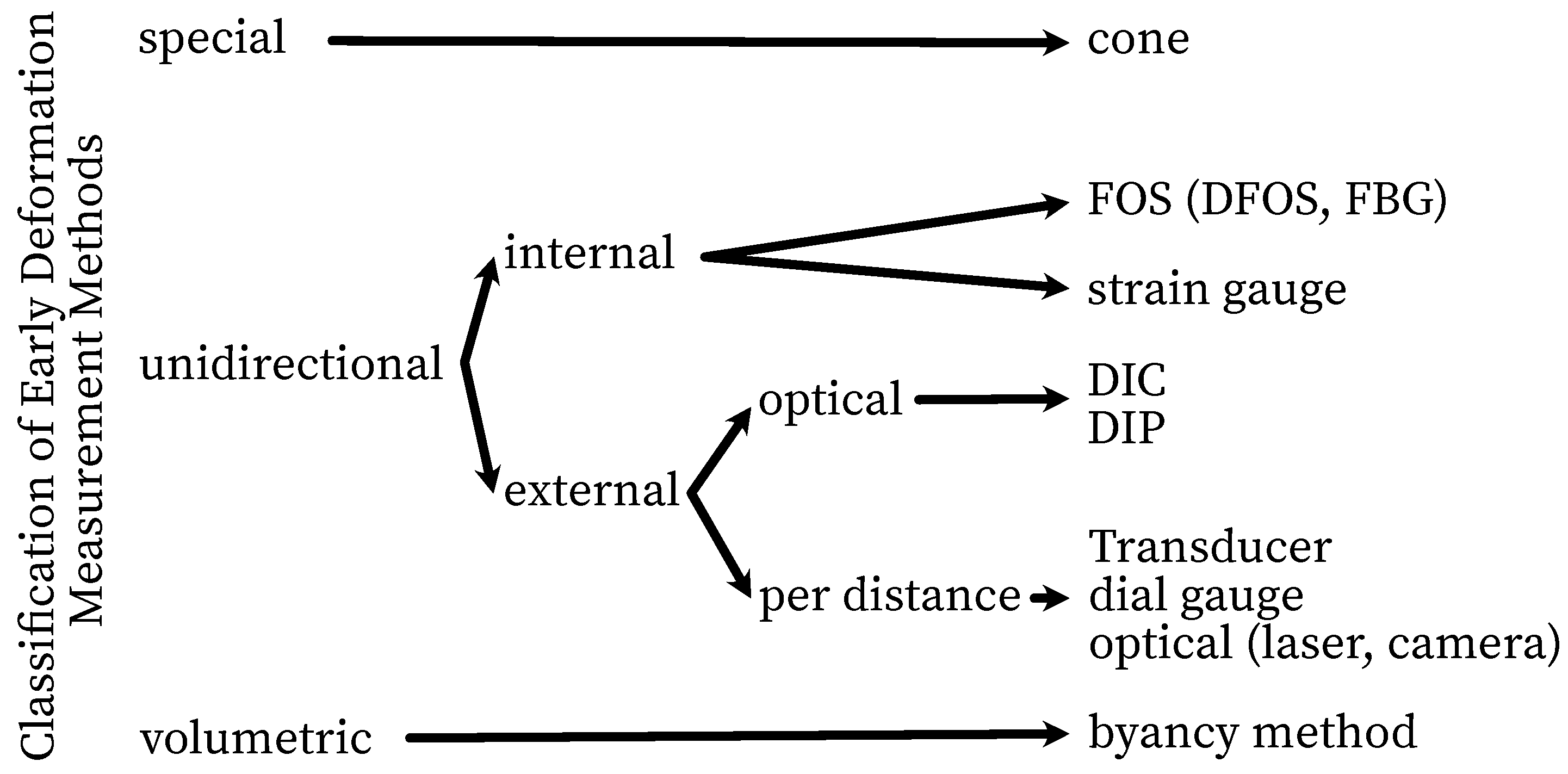

| Category | Measuring device | Example Source |

| unidirectional external | linear gauge | [46] |

| unidirectional external | DIC/DIP | [47,48] |

| unidirectional external | corrugated tube/PST | [41,49] |

| unidirectional external | laser-optic | [29] |

| unidirectional internal | FBG | [50,51,52] |

| unidirectional internal | DFOS | [22,25] |

| unidirectional internal | strain gauge | [53,54] |

| special | cone/laser-optic | [55,56,57] |

| volumetric | byancy method | [58,59] |

| Component | Quantity in |

| 450 | |

| CEN Standard Sand | 1350 |

| Deionized water | 225 |

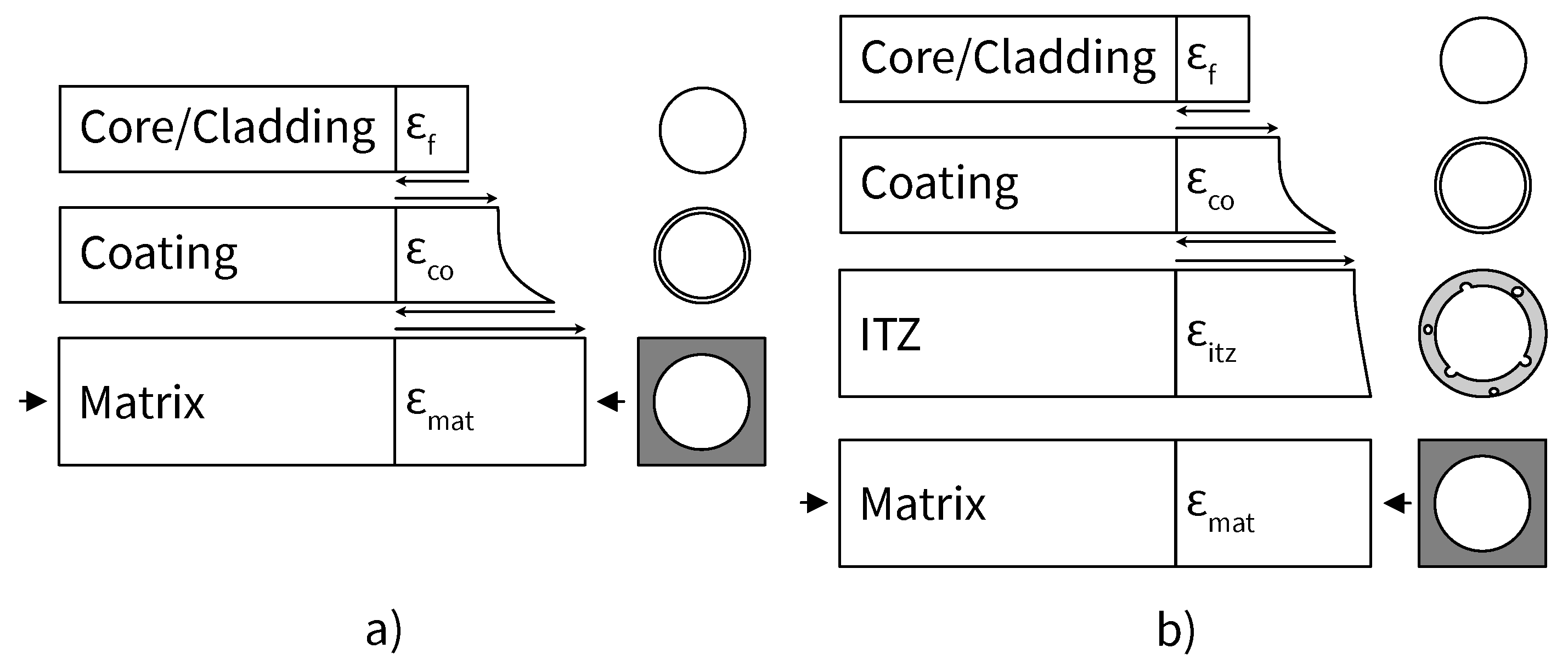

| Description | Ormocer® | uncoatet |

| Notation | OCF | UCF |

| Fibertype | LAL–1550–125 | SMF–28 |

| Ø Core in | 9 | 9 |

| Ø Cladding in | 125(1) | 125(1) |

| Ø Coating in | 195 | – |

| Attenuation at 1550 in | <0.2 | |

| Strain coefficients in | −6.67 |

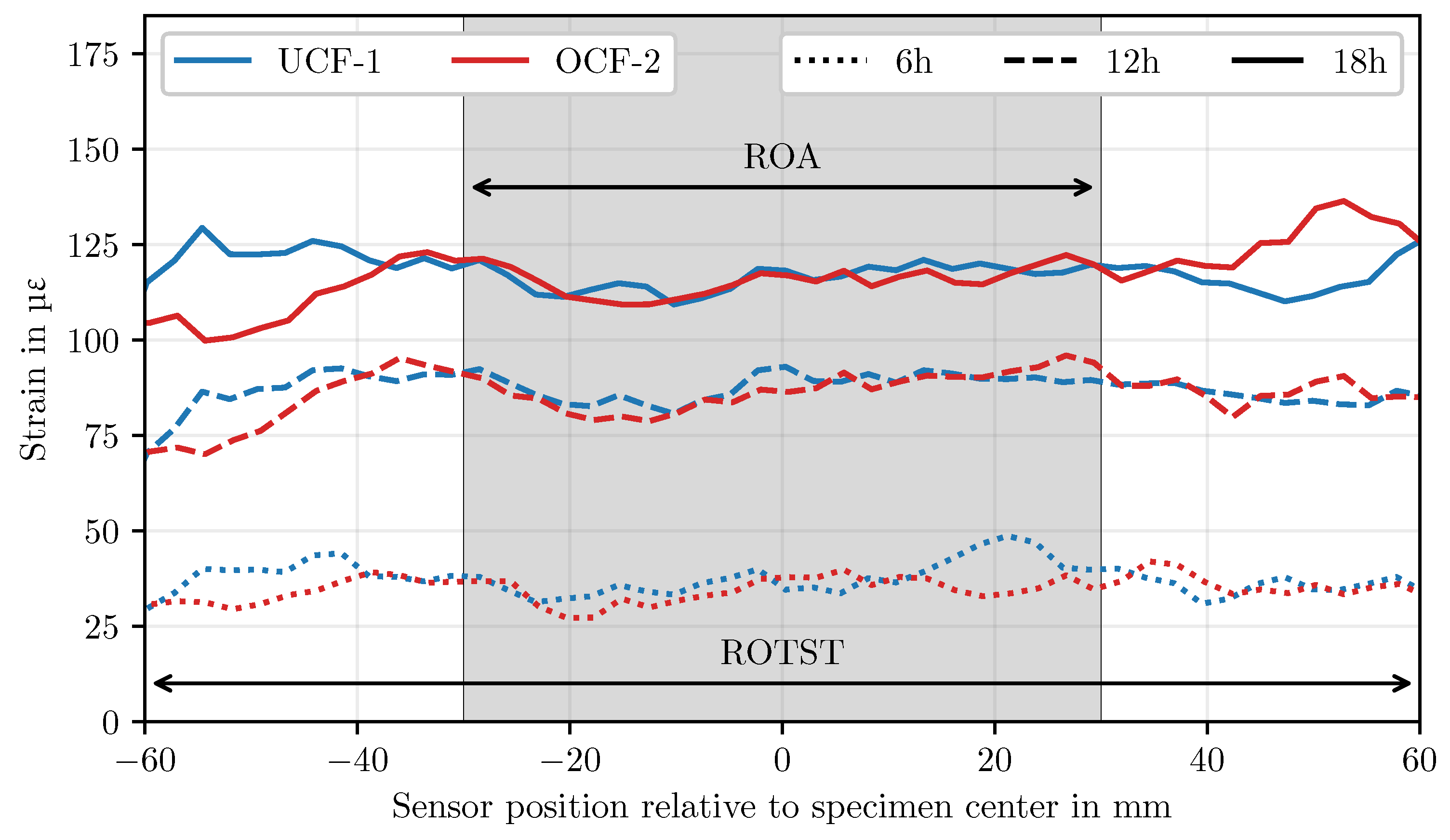

| Nomencl. | No. of spec. | Fibertype | Coating | Cover |

| UCF-X | 3 | SMF–28 | uncoated | PTFE, 1 mm |

| OCF-X | 8 | LAL–1550–125 | Ormocer® | PTFE, 1 mm |

| 1 | LAL–1550–125 | Ormocer® | uncovered |

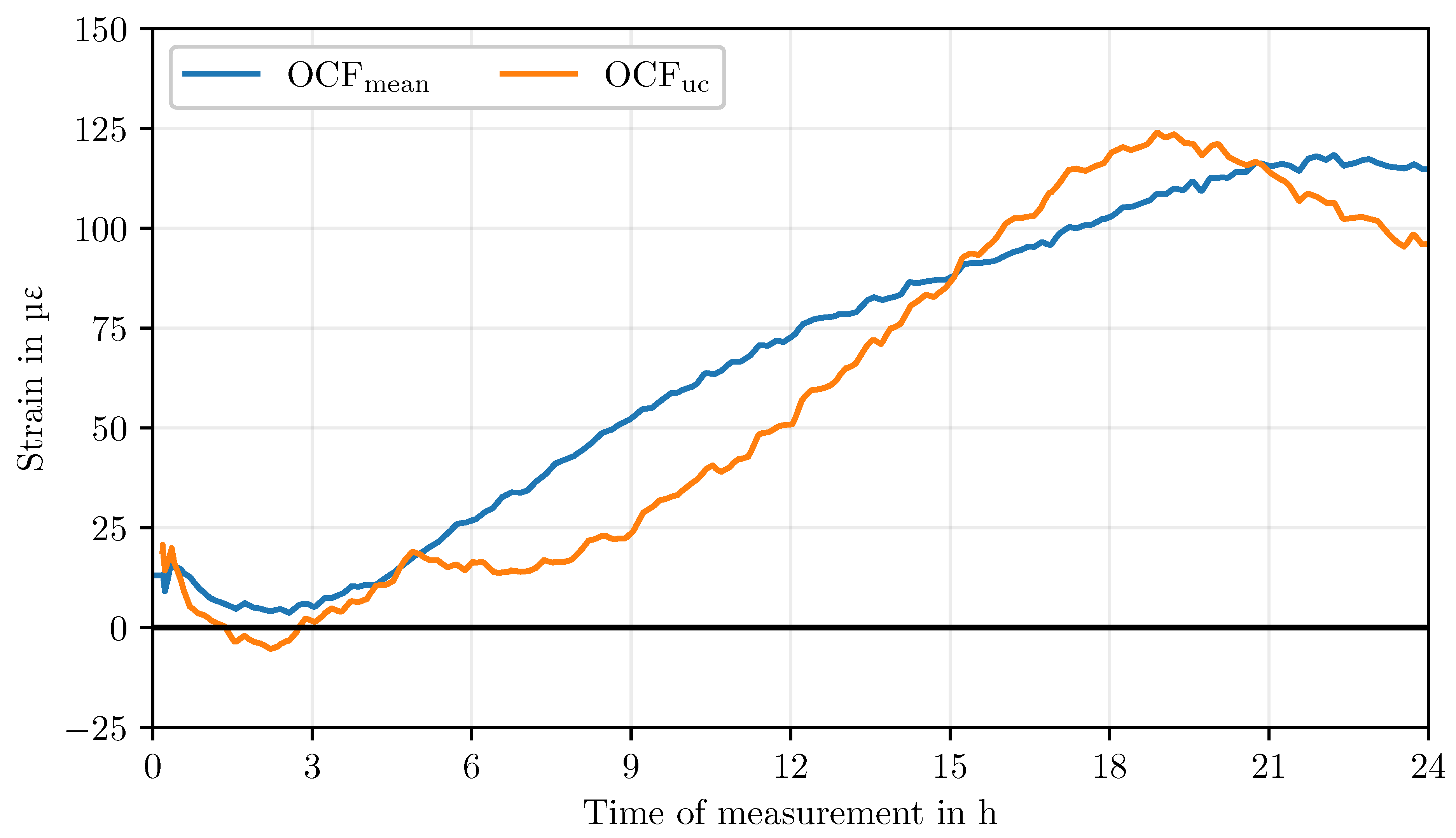

| Time of measurement in h |

Avg. strain in | Range in | ||

| UCF | OCF | UCF | OCF | |

| 3 | −6.6 | 5.3 | 10.0 | 11.8 |

| 6 | 31.8 | 26.4 | 7.6 | 30.9 |

| 9 | 68.6 | 52.3 | 16.9 | 27.7 |

| 12 | 81.5 | 72.9 | 14.7 | 30.5 |

| 15 | 92.2 | 88.2 | 17.0 | 32.3 |

| 18 | 105.1 | 103.7 | 21.7 | 34.5 |

| 24 | 105.1 | 115.5 | 15.3 | 30.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).