Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Fungal Species

Whole Forage Flour Meals of Legumes Substrate Preparation

Observation of the Cultural Characteristics of the Fungus T. viride M5-2 in Legume Flours

Solid State Fermentation Process

Cellulolytic Capacity of T. viride M5-2 in Solid State Fermentation Process

Enzyme Activities

CMCase Enzyme Activity

PFase Enzyme Activity

Productivity of Cellulolytic Enzymes in SSF

Chemical Analysis of Solid State Fermentation Process

Phisical Analysis of Solid State Fermentation Process

Determination of Packing Volume

Determination of Solubility

The Water Adsorption Capacity (WAC)

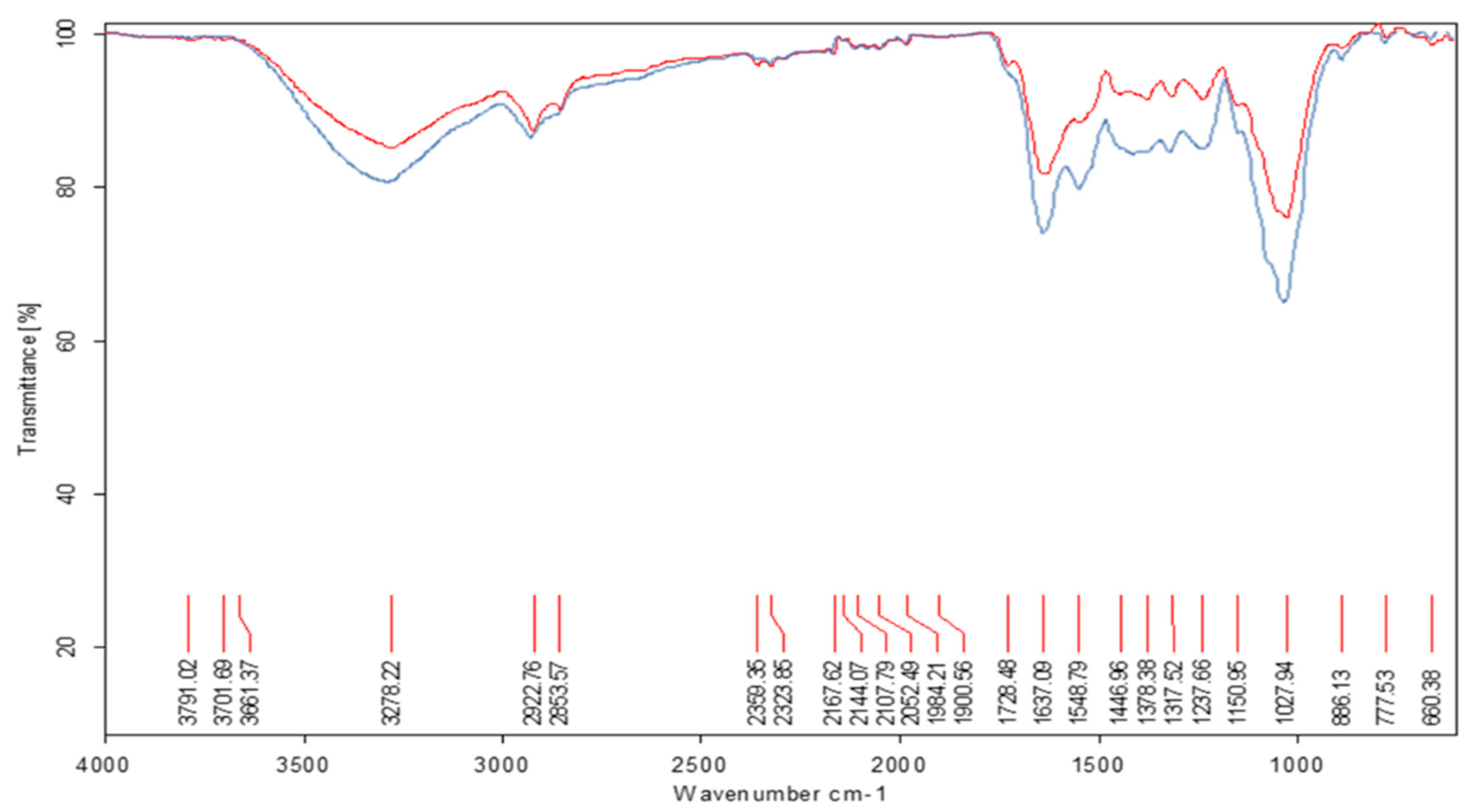

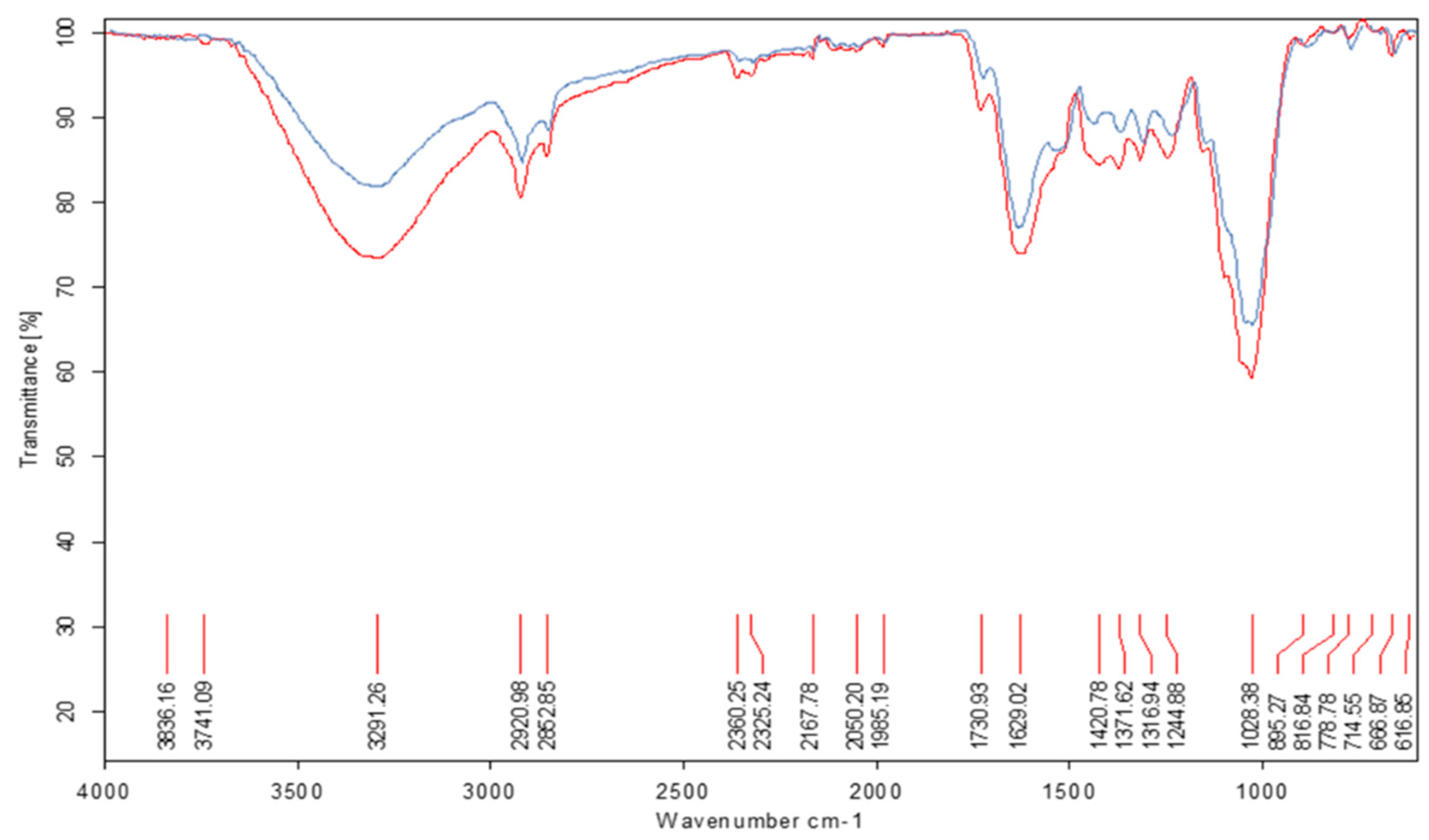

Determination of T. viride M5-2 Structural Changes of the Whole Forage Flours Meals from the Legumes L. purpureus and M. pruriens, by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy ATR-FT-IR Analysis

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Growth of the Lignocellulolytic Fungus T. viride M5-2 on Whole Forage Flours Meals of L. purpureus and M. pruriens

Cellulolytic Capacity of T. viride M5-2 in the Degradation of Legumes in the Solid State Fermentation Process (SSF)

Chemical Analysis of Solid State Fermentation Process by T viride M5-2

Determination of T. viride M5-2 Molecular Changes of Whole Forage Flours Meals from the Legumes L. purpureus and M. pruriens, by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FT-IR) Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ikusika, O.O.; Akinmoladun,O.F.; Mpendulo, C.T. Enhancement of the Nutritional Composition and Antioxidant Activities of FruitPomaces and Agro-Industrial Byproducts through Solid-State Fermentation for Livestock Nutrition: A Review. Fermentation. 2024, 10, 227. [CrossRef]

- Savón, L. ; Scull, I. ; Dihigo, L. E. ; Martínez, M. ; Albert, A. ; Leiva, L. Tropical forage meals: an alternative for sustainable monogastric species production. Multifunctional grasslands in a changing world. 2008, 2, 487-497.

- Ezegbe, C.C.; Nwosu, J. N.; Owuamanam, C.I.; Victor-Aduloju, T.A.; Nkhata, S.G. Proximate composition and anti-nutritional factors in Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean) seed flour as affected by several processing methods. 2023. Heliyon, 9 No. 8. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yoo, J.; Zhang, T.; Yang, K.; Guo, J.; Pan, S. Mixed fermentationof navel orange peel by Trichoderma viride and Aspergillus niger: Effects on the structural and functional properties of soluble dietary fiber. Food Bioscience. 2024, 57, No. 103545. [CrossRef]

- McConnell, L. L. ; Osorio, C. ; Hofmann, T. The future of agriculture and food: sustainable approaches to achieve zero hunger. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023, 71, No. 36, 13165-13167. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, D. K.; Singh, S.; Kumar, S. D.; Sing, T. M.; Dixit, S.; Sawargaonkar, G. Nutrient profiling of lablab bean (Lablab purpureus) from northeastern India: A potential legume for plant-based meat alternatives. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2023, 119, No. 105252. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, L.W.; Ang, T.N.; Ngoh, G.C.; Seak, A.M.C. Fungal solid-state fermentationand various methods of enhancement in cellulase production. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2014, 67, 319-338. [CrossRef]

- Malgas, S.; Thorensen, M.; van Dyk, J.S.; Pletschke, B.I. Time dependence of enzyme synergism during the degradation of model and natural lignocellulosic substrates. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 2017, 103, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Cebrián, M.; Ibarruri, J. Filamentous Fungi Biorefinery. Filamentous fungi processing by solid-state fermentation. Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2023, 251-292.

- Hernández, D.J.M; Ferrera, C.R.; Alarcón, A. Trichoderma: importancia agrícola, biotecnológica, y sistemas de fermentación para producir biomasa y enzimas de interés industrial. Chilean Journal of Agricultural ; Animal Sciences, ex Agro-Ciencia. 2019, 35, No. 1, 98-112.

- Plouhinec, L.; Neugnot, V.; Lafond, M.; Berrin, J.G. Carbohydrate-active enzymes in animal feed. Biotechnology Advances. 2023, 65, No. 10814. [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, D.; Alias, C.; Peron, G.; Ribaudo, G.; Gianoncelli, A.; Savino, S.; Gobbi, E. Solid-state fermentation of Trichoderma spp.: A new way to valorize the agricultural digestate and produce value-added bioproducts. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023, 71, No. 9, 3994-4004. [CrossRef]

- De França, P. D.; Pereira, Jr.N.; de Castro, A.M. A. Comparative review of recent advances in cellulases production by Aspergillus, Penicillium and Trichoderma strains and their use for lignocellulose deconstruction. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 14, 60–66.

- Valiño, E.C.; Dustet, J.C.; Pérez, H.; Brandão, L.R.; Rosa, A.C.; Scull, I. Transformation of Mucuna pruriens with cellulolytics fungi strains as functional food”. Academia Journal of Microbiology Research. 2016, 4, No. 4, 62–71.

- Valiño, E.C., Elías, A., Rodríguez, M.; Albelo, N. Evaluation using Fourier Transformed-infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) of fermentationby the strain T. viride M5-2 from the cell walls of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum Lin) bagasse pretreated International Journal of Chemical and Biomolecular Science. 2015b,1, No. 3, 134-140.

- Valiño, E.C.; Savón, L.; Elías, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Albelo, N. Nutritive value improvement of seasonal legumes Vigna unguiculata, Canavalia ensiformis, M.pruriens, Lablab purpureus, through processing their grains with Trichoderma viride M5-2. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2015a, 49, No. 1, 81-89.

- Wang, L.Y.; Cheng, G.N. ; May, A,S. Fungal solid-state fermentationand various methods of enhancement in cellulases production. Biomass Bioenergy. 2014, 67, 319-338.

- Sosa, A.; González, N.; García, Y.; Marrero, Y.; Valiño, E.; Galindo, J.; Sosa, D. ;Alberto, M.; Roque, D.; Albelo, N.; Colomina, L.; Moreira, O. Collection of microorganisms with potential as additives for animal nutrition at the Institute of Animal Science. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2018, 51, No. 3, 311-319.

- Mandels, M.; Medeiros, J. E.; Andreotti, R.E.; Bissett, F.H. Enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose: evaluation of cellulase culture filtrates under use conditions. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 1981, 23, No. 9, 2009-2026. [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. Chapter 4. Animal Feed. Dr. George Latimer Jr. Editor, 21st ed; AOAC International, Gaithersburg, USA. 2019.

- Scull, I.R.; Savón, L.V.; Spengler, I.S.; Herrera, M.V.; González, V.L. Potentiality of the forage meal of Stizolobium niveum and Stizolobium aterrimum as a nutraceutical for animal feeding. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2018, 52, No. 2, 223-234.

- Van Soest, P.; Robertson, J. B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and non-starch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. Journal of Dairy Science. 1991, 74, No.10, 3583–3597.

- Savón, L.; Scull, I.; Orta, M.; Martínez, M. Whole-grain foliage flours from three tropical legumes for poultry feed. Chemical composition, physical properties, and phytochemical screening. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2007, 41 No. 4, 359-361.

- Di Rienzo, J.; Casanoves, F.; Balzarini, M.; González, L.; Tablada, M.; Robledo, Y.C. InfoStat versión 2017. Grupo InfoStat, FCA, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba: Argentina. 2017.

- Duncan, B. Multiple ranges and multiple F test. Biometrics. 1955, 11, No. 3, 1-42.

- Matas Baca, M. Á.; Flores-Córdova, M. A.; Pérez Álvarez, S.; Rodríguez Roque, M.J.; Salas, Salazar; N.A.; Soto, Caballero, M.C.; Sánchez, Chávez, E. Trichoderma fungi as an agricultural biological control in México. Revista Chapingo. Serie horticultura. 2023, 29, No. 3, 79-114.

- Bézier, S.; Stiegler, M.; Hitzenhammer, E.; Schmoll, M. Screening for genes involved in cellulase regulation by expression under the control of a novel constitutive promoter in Trichoderma reesei. Current Research in Biotechnology. 2022, 4, 238–246. [CrossRef]

- Bamidele, M. O.; Bamikale, M. B.; Cárdenas-Hernández, E.; Bamidele, M. A.; Castillo-Olvera, G.; Sandoval-Cortes, J.; Aguilar, C. N. Bioengineering in Solid-State Fermentation for next sustainable food bioprocessing. Next Sustainability. 2025, 6, No. 100105. [CrossRef]

- Beier, S.; Stiegler, M.; Hitzenhammer, E.; Schmoll, M. Screening for genes involved in cellulase regulation by expression under the control of a novel constitutive promoter in Trichoderma reesei. Current Research in Biotechnology. 2022, 4, 238–246. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Bajarb, S.; Devia, A.; Pantc, D. An overview on the recent developments in fungal cellulase production and their industrial applications Bioresource Technology Reports journal Bioresource Technology. 2021, 14, No. 100652.

- Bhandari, S.; Pandey, K.R.; Joshi, Y.R.; Lamichhane, S. K. An overview of multifaceted role of Trichoderma spp. for sustainable agriculture. Archives of Agriculture and Environmental Science. 2021, 6, No. 1, 72-79. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Deng, L.; Fang, H. Mixed culture of recombinant Trichoderma reesei and Aspergillus niger for cellulase production to increase the cellulose degrading capability. Biomass and Bioenergy. 2018, 112, 93–98. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M. A.; Cabrera, E.C.V.; Aceves, M.A.; Mallol, J.L.F. Cellulolytic and ligninolytic potential of new strains of fungi for the conversion of fibrous substrates. Biotechnology Research and Innovation. 2019, 3, No.1,177-186. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, J.; Leu, S.Y.; Chen, S. Toward a fundamental understanding of cellulase-lignin interactions in the whole slurry enzymatic saccharification process. Biofuels Bioproduct and Biorefinering. 2016, 10, No. 5, 648-663. [CrossRef]

- Dustet, J.C.; Izquierdo, E. Aplicación de balances de masa y energía al proceso de fermentación en estado sólido de bagazo de caña de azúcar con Aspergillus niger. Biotecnología Aplicada. 2004, 21, 85-91.

- Ghose, T. K. Measurement of Cellulase Activities. Pure Appl. Chem. 1987, 59, 257−268.

- Yi, J.; Chen, X.; Wen, Z. ; Fan, Y. Improving the functionality of pea protein with laccase-catalyzed crosslinking mediated by chlorogenic acid. Food chemistry. 2024, 433, No. 137344. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, M.; Sarmiento, L.; Santos, R. H.; Villafranca, M.; Londres, S. Digestive and carcass indicators of Rhode Island Red chickens, which intake rocessed Mucuna pruriens, in two rearing systems. Technical note. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2022, 56, No. 2, 121-126.

- Alberto, Vazquez, M.; Saa, L.R., Valiño, E.; Torta, L.; Laudicina, V.A. Microbiological Aspects and Enzymatic Characterization of Curvularia kusanoi L7: Ascomycete with Great Biomass Degradation Potentialities. Journal of Fungi. 2024, 10, No. 12, 807.

- Jung, N.; Meyer, A.S. Solid-State Fungal Fermentation for Better Plant Foods. Food Science and Nutrition Cases. 2025, fsncases, No. 20250001. [CrossRef]

- Shubha, K.; Choudhary, A. K.; Mukherjee, A.; Kumar, S.; Saurabh, K.; Kumar, R.; Das, A.A. Chemometric study comparing nutritional profiles and functional attributes of two botanical forms of Lablab Bean (Lablab purpureus (L.) Sweet). South African Journal of Botany. 2024, 173, 320-329. [CrossRef]

- Sowdhanyaa, D.; Singha, J.; Rasanea, P.; Kaura, S.; Kaura, J.; Ercislib, S.; Vermac, H. Nutritional significance of velvet bean (Mucuna pruriens) and opportunities for its processing into value-added products. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research. 2024, 15, No. 100921.

- Díaz, M.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.Á.; González, A.; Torres, V.; Noda, A. Biotransformation of Vigna unguiculata during the germination process. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2007, 41, No. 2,161.

- Williams, B.A.; Mikkelsen, D.; Flanagan, B.M. “Dietary fibre”: moving beyond the “soluble/insoluble” classification for monogastric nutrition, with an emphasis on humans and pigs. J Animal Sci Biotechno. 2019, 10, No. 45, 2-12.

- Savón, L.; Scull, I., Orta, M.; Torres, V. Physicochemical characterization of the fibrous fraction of five tropical foliage meals for monogastric species. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2004, 38, No.3, 281-286.

- Vázquez, M.A.; Valiño, E.C.; Torta, L.; Laudicina, A.; Sardina, M.T.; Mirabile, G. Potencialidades del consorcio microbiano Curvularia kusanoi -Trichoderma pleuroticola como pretratamiento biológico para la degradación de fuentes fibrosas. Rev MVZ Córdoba. 2022, 27, No. 2, 2559.

- Valiño, E.C.; Alberto, M.; Dustet, J. C ; Albelo, N. Production of lignocellulases enzymes from Trichoderma viride M5-2 in wheat bran (Triticum aestivum) and purification of their laccases. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2020, 54, No. 1, 55-59.

- García, Y.; Ibarra, A.; Valiño, E. C.; Dustet, J.; Oramas, A.; Albelo, N. Study of a solid fermentationsystem with agitation in the Biotransformation of sugarcane bagasse by the Trichoderma viride strain M5-2. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2002, 36, No. 3, 265-270.

- Sadh, P. K.; Saharan, P.; Duhan, J. S. Bio-augmentation of antioxidants and phenolic content of Lablab purpureus by solid state fermentation with GRAS filamentous fungi. Resource-Efficient Technologies. 2017, 3, No. 3, 285-292.

- Murphy, A. M.; Colucci, P.E. A tropical forage solution to poor quality diets: A review of Lablab purpureus. Livestock Research for Rural Development. 1999, 11, No. 2, 1999.

- Guo, Q.; Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhi, J.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Chen, L. A Comprehensive Review of the Chemical Constituents and Functional Properties of Adzuki Beans (Vigna angulariz). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2025, 73, No. 11, 6361- 6384. [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, H.A.C.O.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P. Physicochemical and functional properties of seed flours obtained from germinated and non-germinated Canavalia gladiata and Mucuna pruriens. Heliyon. 2023, 9, No.19653. [CrossRef]

- Alcívar, J.L.; Martínez, M.P.; Lezcano, P. ; Scull, I.; Valverde, A. Technical note on physical-chemical composition of Sacha inchi (Plukenetia volubilis) cake Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science. 2020, 54, No. 1, 19-23.

- Martínez, M.P.; Vives, Y.H.; Rodríguez, B.; Pérez, G.O.A.; Herrera M.V. Nutritional value of palm kernel meal, fruit of the royal palm tree (Roystonea regia), for feeding broilers. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science, 55th Anniversary. 2021, 55, No. 3, 303-313.

- Alberto, Vazquez, M.; Saa, L. R.; Valiño, E.; Torta, L.; Laudicina, V.A. Microbiological Aspects and Enzymatic Characterization of Curvularia kusanoi L7: Ascomycete with Great Biomass Degradation Potentialities. Journal of Fungi. 2024,10, No. 12, 807-820.

| Cellulolytic Activity | Legumes | Fermentation Time (h) | SE and p | ||||

| 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 120 | |||

| CMCase (IU/mL) |

L. purpureus |

2.09f | 1.18c | 1.22c | 1.01e | 0.99d | ±0.03 p<0,0001 |

|

M. pruriens |

3.15h | 3.29i | 2.57g | 2.01b | 1.90b | ||

| Productivity enzymatic (UI/gMSh) |

L. purpureus |

3.32 | 1.91 | 1.96 | 1.61 | 1.59 | |

|

M. pruriens |

5.36 | 5.46 | 4.26 | 3.32 | 3.15 | ||

| Cellulolytic Activity | Legumes | Fermentation Time (h) | SE and p | ||||

| 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 120 | |||

| PFase (IU/mL) |

L. purpureus |

0.74d | 0.46e | 0.39e | 0.38ef | 0.20d | ±0.01 p<0,0001 |

|

M. pruriens |

0.49g | 0.60d | 0.64c | 0,63c | 0.50b | ||

| Productivity enzymatic (UI/gMSh) |

L. purpureus |

1.17 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.32 | |

|

M. pruriens |

0.84 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 0.83 | ||

| Indicator | Legumes | Fermentation Time (h) | SE and p | |||||

| pH | 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 120 | ||

| L. purpureus |

6.13d | 6.83f | 7.46i | 7.37h | 7.28g | 7.20b | ±0.03 p<0.001 |

|

| M. pruriens |

6.03c | 6.71e | 6.72e | 7.12g | 7.11a | 7.10g | ||

| Indicators (% de DM) |

Legumes | Fermentation Time (h) | SE and p | |||

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | |||

| DM* | L. purpureus | 28.1d | 28.3d | 27.8c | 27.9b | ±0.11 p<0.05 |

| M. pruriens | 28.8c | 26.4a | 27.1b | 27.1b | ||

| CP | L. purpureus | 13.63a | 17.15c | 15.36a | 17.03c | ±0.13 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 19.04b | 21.34d | 22.05e | 21.27d | ||

| TP | L. purpureus | 11.30a | 13.24a | 13.21a | 14.40b | ±0.14 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 17.58c | 19.53e | 21.74g | 20.61f | ||

| NDF | L. purpureus | 67.83 b | 67.83b | 66.74a | 67.90b | ±0.29 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 73.06d | 68.48b | 69.56c | 69.83c | ||

| ADF | L. purpureus | 51.44a | 51.18a | 52.97c | 54.31d | ±0.18 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 52.27b | 52.54bc | 52.64bc | 54.78d | ||

| Cel | L. purpureus | 42.07f | 39.28b | 41.67e | 43.88g | ±0.13 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 39.66c | 39.97cd | 38.41a | 40.14d | ||

| Lig | L. purpureus | 9.17a | 10.87 c | 10.93c | 10.20b | ±0.13 p<0.001 |

| M. pruriens | 12.33e | 11.38d | 13.35f | 13.98g | ||

| Hem | L. purpureus | 16.39d | 16.65d | 13.27a | 13.59a | ±0.08 p<0.0001 |

| M. pruriens | 20.79f | 15.74c | 16.92e | 15.05b | ||

| Physical indicators | Legumes | Fermentation Time (h) | ||||

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | SE and p | ||

| V (g/ml) | L. purpureus | 4.05a | 3.60b | 3.35d | 4.05a | ±0,04 p<0,0001 |

| M. pruriens | 3.48c | 3.21e | 3.41de | 3.25de | ||

| WAC (g/g) | L. purpureus | 3.71d | 3.76d | 2.85e | 4.36c | ±0,13 p=0,0005 |

| M. pruriens | 4.66bc | 5.14a | 4.68bc | 4.78ab | ||

| ABC (meq) | L. purpureus | 0.51f | 0.42h | 0.59b | 0.47g | ±0,002 p<0,0001 |

| M. pruriens | 0.63a | 0.58c | 0.53d | 0.56e | ||

| BBC (meq) | L. purpureus | 0.36c | 0.31g | 0.43a | 0.36c | ±0,001 p<0,0001 |

| M. pruriens | 0.32f | 0.41b | 0.35d | 0.33e | ||

| Physical indicator | Legumes | SE and p | |||

|

Solubility (%) |

L. purpureus | M. pruriens | ±0,07 p=0,0613 |

||

| 7.22 | 7.22 | ||||

| Fermentation time (h) |

±0,11 p=0,0024 |

||||

| 0 | 24 | 48 | 72 | ||

| 7,05bc | 7,16ab | 7,47a | 6,77c | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).