Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Imaging Methods Used in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

- A.

- Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, allowing for direct visualization of the mucosa, biopsy sampling [14], and treatment of some complications. It is superior to other imaging methods in highlighting superficial erosions and ulcerations, mucosal hyperemia, and loss of vascular pattern and detecting colonic polyps [2]. Despite its advantages, it has certain limitations: it is invasive, can be uncomfortable for the patient, and does not allow for visualization of the entire small intestine, requiring the use of additional imaging techniques such as CT, intestinal ultrasound, and MRE [15]. However, a colonoscopic evaluation is necessary if patients have persistent symptoms despite normal MRE results [16]. Colonoscopy also cannot evaluate extraintestinal lesions and may limit the penetration of the endoscope in the presence of stenosis (stricture) [17]. Additionally, during the examination, lesions located in hidden parts of the colon may be missed [18].

- B.

- Video capsule endoscopy is useful in exploring the small intestine, with high sensitivity for early mucosal changes, such as small aphthous lesions[19]. It is also indicated in patients with suspected Crohn's disease and normal endoscopic results[20,21]. Recent studies have shown that video capsule endoscopy is superior to MRE in detecting lesions located in the proximal region of the small intestine[20]. However, it does not allow for in-depth evaluation of the intestinal wall and carries a risk of capsule retention in stenoses and intestinal obstructions.

- C.

- Intestinal ultrasound is a non-invasive, accessible, radiation-free method that does not require prior preparation, except for fasting a few hours before the examination[8]. Firstly, it allows for the detection of wall thickening, with a value over 3 mm considered pathological [8] and a measurement over 7 mm indicating an unfavorable prognosis, with surgical indication within the following year [22]. At the same time, the use of color Doppler or contrast medium (CEUS) allows for evaluation of both the wall perfusion and the intestinal inflammatory status, as well as the presence of complications (fistulas, abscesses, or inflammatory lesions), visualized as hypo or hyperechogenic masses[8]. An increased color Doppler signal is observed in cases of transmural edema present in the active form of Crohn's disease, as evidenced by disrupted mural stratification[23]. Intestinal ultrasound is also useful in detecting the thickening of peri-visceral adipose tissue or fat wrapping [24], as evidenced by increased echogenicity at this level, representing a sign of active disease [23]. Ultrasound images may be unsatisfactory and limited in obese patients, body habitus, or significant abdominal distension that may obscure the intestinal region [23].

- D.

- Computed tomography enterography provides detailed images of both the small intestine—highlighting intestinal wall thickening, hyperemia, submucosal fat deposition, and lymphadenopathy[25,26]—and of extraintestinal, perineural lesions, with greater accuracy in terms of the degree and severity of the disease [27], differentiating the active form from the fibrotic one. At the same time, this imaging technique is frequently used for the detection of complications of inflammatory bowel diseases (fistulas, perforations, and abscesses) [25,26] and in emergencies, such as sepsis or penetrating intra-abdominal lesions requiring surgical intervention [13]. Other advantages of CTE include a shorter scanning time, reduced costs compared to MRE [28], and suitability for patients with contraindications to MRE [13], those who are allergic to gadolinium-based contrast media [8],those who were claustrophobic in prior MR exams, and those with acute symptoms [13]. The main disadvantage is exposure to ionizing radiation, which limits its repeated use in young patients [29,30]. The radiation dose used in CTE for the adult population is between 10 and 20 mSv (milisievert) [31], while that in the pediatric population is between 2.9 and 4 mSv [32]. New protocols propose reducing the radiation dose in adults to 5-7 mSv and the noise produced by CTE during the investigation [33]. At the same time, recent studies have focused their interest on artificial intelligence and radiomics. Li et al. have demonstrated that a radiomics model (RM) based on CTE accurately describes intestinal fibrosis in patients with CD[34].

- E.

- Magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) has become the gold standard [8] in the evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease, providing simultaneously detailed images of the intestinal wall and adjacent structures and inflammatory lesions [23], differentiating inflammation from fibrosis in both the small and large intestine submucosa and the perineal area [35,36]. MRE also has high accuracy in staging small bowel inflammatory bowel disease [30], in monitoring treatment response and relapse [23], and in detecting and classifying isolated forms of colonic involvement [37]. This imaging modality is preferred in complex cases with evidence of penetrating, fistulizing, and stenosing lesions [23], as well as in fistulas and perianal sepsis [13]. Fat smudging, fecal sign, fluid level, gaseous distension, comb sign (related vascular congestion), and lymphadenopathy are elements mainly visualized/detected by MRE [2]. Another advantage—perhaps the most important—is that MRE is an imaging method that can be used to evaluate the activity of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in both adults and young people [38], without the use of ionizing radiation [2]. Taylor et al. have shown that MRE has a sensitivity of 97% for detecting inflammatory bowel diseases, over 90% for fibro-inflammatory strictures, and specificity of over 95% [30].

3. Technical Principles of MRE

3.1. Standardized Protocol for MRE

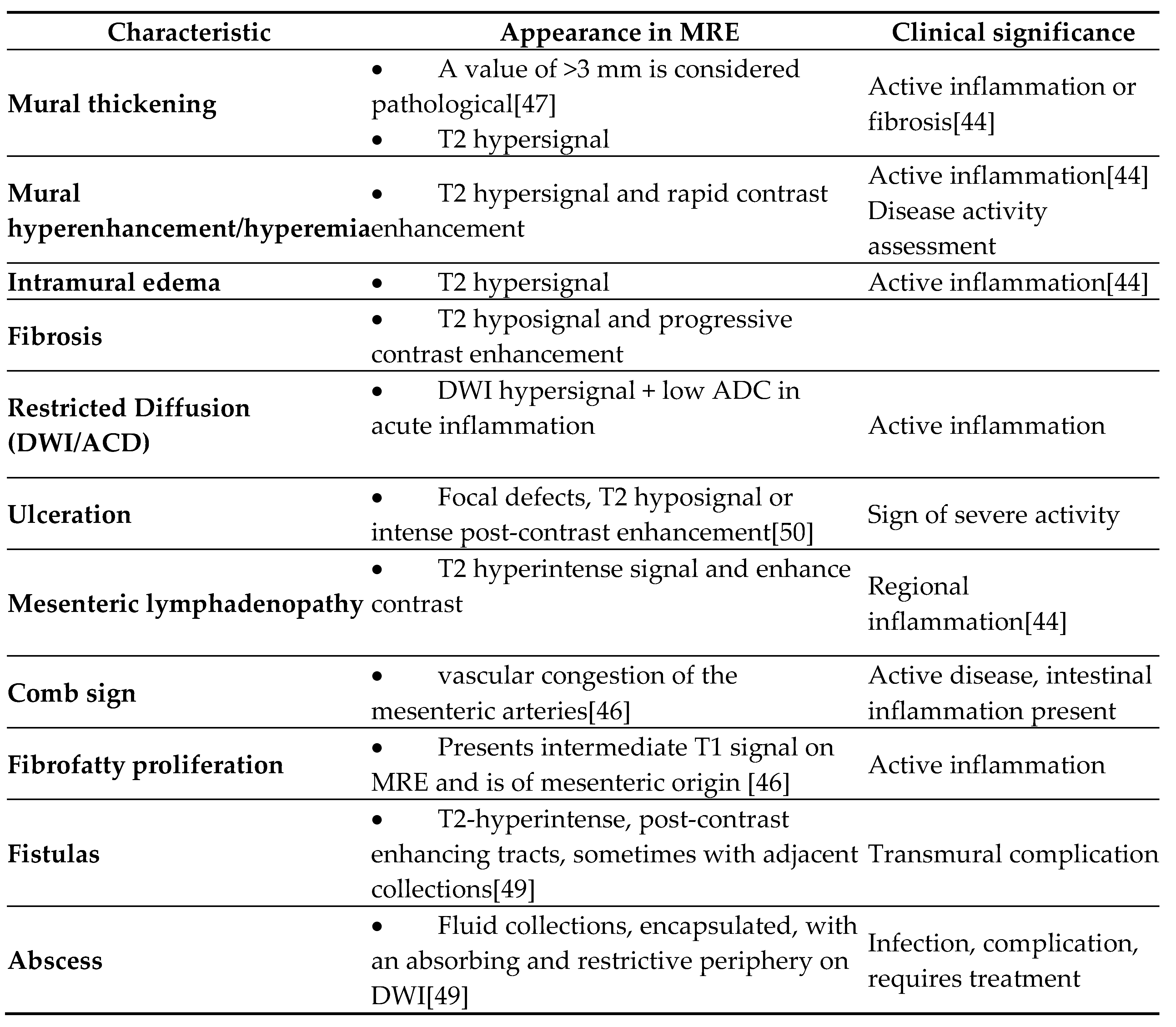

3.2. Relevant Imaging Features in Magnetic Resonance Enterography

- a.

- Mural thickening :

- Is mild (<5 mm), moderate (<9mm) and severe (> 10 mm)

- Commonly occurs in active areas of inflammation (Figure 1).

- b.

- Mural hyperenhancement

- Asymmetric distribution in CD or ontinuous and concentric distribution in extensive ulcerative colitis[44]

- Stratified uptake: “double layer” (submucosa is thickened by edema and inflammation) or “trilaminar layer” (when serosa is also involved) [8]

- Homogeneous, hypovascular uptake in (chronic) fibrosis

- Correlates with clinical and biological activity scores [44]

- Evaluated on post-gadolinium T1 fat-sat sequences, in dynamics [50]

- c.

- Intramural edema

- Is detected as T2 hyperintense signal

- d.

- Restricted diffusion

- DWI hypersignal + low ADC in acute inflammation

- e.

- Ulceration

- Focal defects, fine disruptions of the mucosal contour - small signs of T2 hyposignal or intense post-contrast enhancement[50]

- Requires adequate distension of the small bowel (Figure 4 ).

- f.

- Mesenteric lymphadenopathy

- g.

- Comb sign

- h.

- Fibrofatty proliferation

- Also called “creeping fat”

- i.

- Fistulas

- They may be enteroenteric, enterocolic, enterovesical, or perianal [8]

- Fistulae occur following advanced penetrating disease [8]

- j.

- Abcesses

- Abscesses are found in the abdominal cavity, intestinal wall, or perianal area[8]

- k.

- Stenosis

- May be inflammatory (with edema and entrapment) or fibrotic (without inflammatory signs)(Figure 7)

4. Applicability of MRE in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

4.2. Differentiating Between Active Inflammation and Fibrosis

4.3. Screening/Detection of Complications

- ➢

- Enteroenteric, enterocutaneous, perianal fistulas: MRE can distinguish between simple and complicated fistulas, guiding the decision between conservative treatment and surgical drainage;

- ➢

- Intra-abdominal abscesses;

- ➢

- Fibrous stenosis with dilation of the upstream loops;

- ➢

- Mesenteric adenopathies and changes in perenteric fat;

- ➢

- Toxic megacolon—a rare but severe complication of ulcerative colitis [29].

4.4. Monitoring Response to Treatment

4.5. Complementarity with Other Methods

- ➢

- Exploration of jejunal and ileal loops;

- ➢

- Transmural and extramural evaluation;

- ➢

- Therapeutic guidance in the absence of obvious colonic lesions.

4.6. Role in Staging and Imaging Scores

- Standardized imaging scores in Magnetic Resonance Enterography

- The most widely studied scoring system that assesses Crohn's disease activity on MRE is the magnetic resonance index activity (MaRIA) score. The score is calculated using the following equation:

- MaRIA score=1.5 x wall thickness + 0.02 x RCE (relative contrast enhancement) + 5 x edema + 10 x ulceration [61];

- ➢

- Normal: 0-6;

- ➢

- Moderate disease: ≥ 7-11;

- ➢

- Severe disease: ≥ 11 [23].

- 2.

- The major disadvantage of this score is that it is time-consuming to obtain. Such a limitation led to the development of a simplified new scoring system, the sMaRIA, which requires just 4.5 minutes compared to over 12 minutes for the MARIA [23,61,62]. The sMaRIA was validated by Ordas et al. in 2019, and its most significant advantage is that it does not involve contrast-enhanced imaging [23,63].

- MARIAs = (1 x thickness >3 mm) + (1 x edema) + (1 x fat stranding) + (2 x ulcers)

- ➢

- A score of >1 identifies active disease, with 90% sensitivity and 81% specificity;

- ➢

- 3.

5. Limitations and Challenges of enteroMR

5.1. Accessibility and Costs

- MRE requires modern, high-performance equipment (preferably 1.5T or 3T), specialized software, and trained personnel.

- The limited availability of these resources in some centers may restrict patient access.

- Additionally, the associated costs are higher than those of other investigations, such as ultrasound or CT, which may influence clinical decisions in resource-limited health systems.

- The examination time is longer (30-45 minutes), which can lead to longer waiting lists in congested hospitals.

5.2. The Need for Standardized Protocols and Experience in Interpretation

- There are variations among centers regarding the oral contrast dose scanning technique used and the criteria for interpreting the images, especially in centers without a standardized protocol.

- The lack of correlation with clinical findings and biomarkers can lead to over- or underdiagnosis errors.

- The scores used to assess disease activity (e.g., MaRIA, Clermont, Nancy, and London score) are not always applied uniformly in all centers.

5.3. Patient Preparation and Compliance

- The examination requires specific preparation, including the ingestion of a large volume of oral solution, maintaining immobility for 30-45 minutes, and tolerating possible dyspeptic symptoms. These factors can limit the quality of the examination, especially in children, elderly patients, or patients with severe abdominal pain.

5.4. Artifacts and Technical Limitations

- Respiratory movements and intestinal peristalsis can generate artifacts that degrade image quality, despite the administration of antiperistaltic agents.

- Excessive intestinal gas can affect adequate loop distension and correct interpretation.

- The sensitivity of MRE is lower than that of endoscopy in cases of small, superficial lesions, such as millimeter-sized ulcerations, incipient disease, or subtle inflammatory changes.

5.5. Contraindications and Limitations of use

- Patients with severe claustrophobia or incompatible metallic implants cannot be examined.

- MRE is not indicated in major emergencies, such as perforations or complete occlusions, where CT is preferred for speed.

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

6.1. Main Benefits of enteroMRI

6.2. Research and Innovation Directions

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cozzi D., Moroni C., Addeo G., Danti G., Lanzetta M.M., Cavigli E., Falchini M., Marra F., Piccolo C.L., Brunese L., et al. Radiological Patterns of Lung Involvement in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018;2018:5697846. - DOI - PMC - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Rasha Mostafa Mohamed Ali, Aya Fawzy Abd El Salam, Ismail Anwar, Hany Shehab, Maryse Youssef Awadallah. Role of MR enterography versus ileo-colonoscopy in the assessment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med 2023;54:17. doi.org/10.1186/s43055-023-00967-5.

- Arif-Tiwari H., Taylor P., Kalb B.T., Diego R. M. Magnetic resonance enterography in inflammatory bowel disease. Appl Radiol 2019; (1):9-15.

- Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV Jr. Incidence and Prevalence of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota From 1970 Through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15:857.

- Bernstein CN, Wajda A, Svenson LW, et al. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:1559.

- Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: a large, population-based study in Sweden. Gastroenterology 1991; 100:350.

- Schultsz C, Van Den Berg FM, Ten Kate FW, et al. The intestinal mucus layer from patients with inflammatory bowel disease harbors high numbers of bacteria compared with controls. Gastroenterology 1999; 117:1089.

- Biondi M., Bicci E., Danti G., Flammia F., Chiti G., Palumbo P., Bruno F., Borgheresi A., Grassi R., Grassi F. The role of Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Crohn’s Disease:A Review of Recent Literature. Diagnostics 2022; 12, 1236. [CrossRef]

- Girometti R, Zuiani C, Toso F, et al. MRI scoring system including dynamic motility evaluation in assessing the activity of Crohn’s disease of the terminal ileum. Acad Radiol. 2008;15(2):153-164. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio C., Dal Buono A., Levi R., Gabbiadini R., Reca C., Bezzio C., Francone M., Armuzzi A., Balzarini L. Reporting of Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Results of an Italian Survey. J Clin Med. 2024, 13, 3953. [CrossRef]

- Fiorino G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S (2012) Bowel damage assessment in Crohn’s disease by magnetic resonance imaging. Curr Drug Targets 13:1300–1307.

- Brem O., Elisha D., Konen E., Amitai M., Klang E. Deep learning in magnetic resonance enterography for Crohn’s disease assessment : a systematic review. Abdominal Radiology 2024.49:3183-3189. [CrossRef]

- Bruining D., Zimmermann E., Loftus E Jr , Sandborn W., Sauer C. , Strong S. Consensus Recommendations for Evaluation, Interpretation, and Utilization of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Patients With Small Bowel Crohn's Disease. Radiology. 2018 Mar;286(3):776-799. [CrossRef]

- Rutter MD, Saundrs BP, Wilkinson M, et al. Colonoscopy in IBD:When, how, and why?Gut. 2022; 71(1):15-30.

- RimolaJ, Ordas I, Rodiguea S, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography in Crohn’s disease:Expert consensus recommendations. Gastroenterology. 2022; 162(3):803-817.

- Dulai PS, Levesque BG, Feagan BG (2015) Assessment of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc 82(2):246–255.

- Langan RC, Gotsch PB, Krafczyk MA (2007) Ulcerative colitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician 76(9):1323–1330.

- Neumann H, Tontini GE, Albrecht H (2016) Su1702 accuracy of the full spectrum endoscopy system (FUSE) for prediction of colorectal polyp histology. Gastrointest Endosc 83(5):AB402.

- Tillack C, Seiderer J, Brand S, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance enteroclysis (MRE) and wireless capsule endoscopy (CE) in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14(9):1219–1228.

- Kopylov U. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy versus magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel contrast ultrasound in the evalu- ation of small bowel Crohn’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:854–863. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Rozendorn N., Klang E., Lahat A., Yablecovitch D., Kopylov U., Eliakim A., Ben-Horin S., Amitai M.M. Prediction of patency capsule retention in known Crohn’s disease patients by using magnetic resonance imaging. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2015;83:182–187. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Castiglione F, de Sio I, Cozzolino A, et al. . Bowel wall thickness at abdominal ultrasound and the one-year-risk of surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1977–83. - PubMed.

- Kumar S. , De Kock I., Blad W., Hare R., Pollok R., Taylor S.Magnetic Resonance Enterography and Intestinal Ultrasound for the Assessment and Monitoring of Crohn's Disease.J Crohns Colitis2024 Sep 3;18(9):1450-1463. [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld G., Brown J., Vos P.M., Leipsic J., Enns R., Bressler B. Prospective Comparison of Standard- Versus Low-Radiation-Dose CT Enterography for the Quantitative Assessment of Crohn Disease. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2018;210:W54–W62. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Gore RM, Balthazar EJ, Ghahremani GG, Miller FH. CT features of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:3-15.

- Duigenan S, Gee MS. Imaging of pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:907-915.

- Elsayes K, Al Hawary MM, Jagdish J et al. (2010) CT enterography: principles, trends, and interpretation of findings. RadioGraphics 30:1955–1970.

- Haas K, Rubesova E, Bass D. Role of imaging in the evaluation of inflammatory bowel disease: How much is too much? World J Radiol 2016; 8(2): 124-131 [PMID: 26981221. [CrossRef]

- Makanyanga JC, Taylor SA. Current and future role of MRI in Crohn’s disease. Clinical Radiology. 2021; 76(3):157-167.

- aylor SA, Mallett S, Bhatnagar G, et al.Diagnostic accurancy of magnetic resonance enterography and small bowel ultrasound for the extent and activity of Crohn’s disease (METRIC): A multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021; 6(8):548-562.

- Mettler FA, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology. 2008;248:254-263.

- Gaca AM, Jaffe TA, Delaney S, Yoshizumi T, Toncheva G, Nguyen G, Frush DP. Radiation doses from small-bowel follow-through and abdomen/pelvis MDCT in pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2008;38:285-291.

- Del Gaizo AJ, Fletcher JG, Yu L, Paden RG, Spencer GC, Leng S, Silva AM, Fidler JL, Silva AC, Hara AK. Reducing radiation dose in CT enterography. Radiographics. 2013;33:1109-1124.

- X. Li, D. Liang, J. Meng, et al. Development and validation of a novel computed-tomography enterography radiomic approach for characterization of intestinal fibrosis in crohn's disease Gastroenterology, 160 (2021), pp. 2303-2316e11.

- Martin DR, Lauenstein T, Sitaraman SV. Utility of magnetic resonance imaging in small bowel Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2007; 133(2):385–390.

- Kim KJ, Lee Y, Park SH (2015) Diffusion-weighted MR enterography for evaluating Crohn’s disease: how does it add diagnostically to conventional MR enterography. Inflamm Bowel Dis 21(1):101–109.

- Kaushal P, Somwaru AS, Charabaty A (2017) MR enterography of inflammatory bowel disease with endoscopic correlation. Radiographics 37(1):116–131.

- Lanier MH, Shetty AS, Salter A (2018) Evaluation of noncontrast MR enterography for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease assessment. J Magn Reson Imaging 48(2):341–348.

- Fallis S.A., Murphy P., Sinha R. Magnetic reso-nance enterography in Crohn’s disease: A compari-son with the findings at surgery. Colorectal. Dis. 2013;15:1273–1280. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Kuehle C.A., Ajaj W., Ladd S.C., Massing S., Barkhausen J., Lauenstein T.C. Hydro-MRI of the Small Bowel: Effect of Contrast Volume, Timing of Contrast Administration, and Data Acquisition on Bowel Distention. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2006;187:W375–W385. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Maccioni F., Bruni A., Viscido A., Colaiacomo M.C., Cocco A., Montesani C., Caprilli R., Marini M. MR Imaging in Patients with Crohn Disease: Value of T2- versus T1-weighted Gadolinium-enhanced MR Sequences with Use of an Oral Superparamagnetic Contrast Agent. Radiology. 2006;238:517–530. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Low R.N., Sebrechts C.P., Politoske D.A. Crohn disease with endoscopic correlation: Single-shot fast spin-echo and gadolinium-enhanced fat-sup-pressed spoiled gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiology. 2002;222:652–660. - DOI - PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Tolan DJ, Greenhalgh R, Zealley IA, Halligan S, Taylor SA. MR enterographic manifestations of small bowel Crohn disease. Radiographics. 2010; 30(2):367-384.

- Moy M., Sauk J., Gee M. The Role of MR Enterography in Assessing Crohn's Disease Activity and Treatment Response. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015 Dec 27;2016:8168695. [CrossRef]

- Radmard A., Amouei M.,Torabi A.,Sima A.,Saffar H., Geahchan A., Davarpanah A., Taouli B. MR Enterography in Ulcerative Colitis:Beyond Endoscopy. RadioGraphics.2024Volume 44, Issue 1. [CrossRef]

- Rimola J, Fernandez-Clotet A, Capozzi N, et al. . ADC values for detecting bowel inflammation and biologic therapy response in patients with Crohn disease: a Post-Hoc Prospective Trial Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2023;222:e2329639. - PubMed.

- Mentzel HJ, Reinsch S, Kurzai M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in children and adolescents with chronic inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 1180-1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Alexopoulou E, Roma E, Loggitsi D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the small bowel in children with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease: evaluation of disease activity. Pediatr Radiol 2009; 39: 791-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Qiu Y, Mao R, Chen BLet al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: magnetic resonance enterography vs. computed tomography enterography for evaluating disease activity in small bowel Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 40: 134-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Biernacka K., Barańska D., Matera K., PodgórskiM. , Czkwianianc E., Zakrzewska K., Dziembowska I., Grzelak P. The value of magnetic resonance enterography in diagnostic difficulties associated with Crohn’s disease. Pol J Radiol. 2021 Mar 3;86:e143–e150. [CrossRef]

- Athanasakos A, Mazioti A, Economopoulos N, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease-the role of cross-sectional imaging techniques in the investigation of the small bowel. Insights Imaging 2015; 6: 73-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar].

- Ordas I, Rimola J, Rodriuea-Lago I, et al. Imaging in inflammatory bowel disease: State of the art. Gut.2023. 72(5):889-904.

- Fornasa F., Benassuti C., Benazzato L. Role of magnetic resonance enterography in differentiating between fibrotic and active inflammatory small bowel stenosis in patients with Crohn's disease. Journal of Clinical Imaging Science. 2011;1, article 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Gee M. S., Nimkin K., Hsu M., et al. Prospective evaluation of MR enterography as the primary imaging modality for pediatric Crohn disease assessment. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2011;197(1):224–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Baert F., Moortgat L., Van Assche G., et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):e410–e468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Neurath M. F., Travis S. P. L. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61(11):1619–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Frøslie K. F., Jahnsen J., Moum B. A., Vatn M. H. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):412–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar. [CrossRef]

- Björkesten C.-G., Nieminen U., Sipponen T., Turunen U., Arkkila P., Färkkilä M. Mucosal healing at 3 months predicts long-term endoscopic remission in anti-TNF-treated luminal Crohn's disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;48(5):543–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Rutgeerts P., Van Assche G., Sandborn W. J., et al. Adalimumab induces and maintains mucosal healing in patients with Crohn's disease: data from the EXTEND trial. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(5):1102.e2–1111.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Peyrin-Biroulet L., Deltenre P., de Suray N., Branche J., Sandborn W. J., Colombel J.-F. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2008;6(6):644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- 61. Rimola J, Ordás I, Rodriguez S et al. Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Evaluation of Crohn's Disease: Validation of Parameters of Severity and Quantitative Index of Activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(8):1759-68. - Pubmed. [CrossRef]

- Williet N, Jardin S, Roblin X.. The simplified Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity [MARIA] for Crohn’s disease is strongly correlated with the MARIA and Clermont score: an external validation. Gastroenterology 2020;158:282–3. - PubMed.

- Ordás I, Rimola J, Alfaro I et al. Development and Validation of a Simplified Magnetic Resonance Index of Activity for Crohn's Disease. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(2):432-439.e1. - Pubmed. [CrossRef]

- Kumar S., Plumb a., Mallett S., Bhatnagar G., Bloom S., Clarke C. , Hamlin J.,Hart A., Jacobs I., Travis S., Vega R., Halligan S. , Taylor S. METRIC-EF: magnetic resonance enterography to predict disabling disease in newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease—protocol for a multicentre, non-randomised, single-arm, prospective study. BMJ Open 2022;12:e067265. [CrossRef]

- Nieun Seo. Comprehensive Review of Magnetic Resonance Enterography-Based Activity Scoring Systems for Crohn’s Disease. iMRI 2025;29(1):1-13 . [CrossRef]

- Makanyanga J. C., Pendsé D., Dikaios N., et al. Evaluation of Crohn's disease activity: initial validation of a magnetic resonance enterography global score (MEGS) against faecal calprotectin. European Radiology. 2014;24(2):277–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]. [CrossRef]

- Steward MJ, Punwani S, Proctor I, et al. Non-perforating small bowel Crohn’s disease assessed by MRI enterography: derivation and histopathological validation of an MR-based activity index. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:2080-2088.

- Hordonneau C, Buisson A, Scanzi J, et al. . Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in ileocolonic Crohn’s disease: validation of quantitative index of activity. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:89–98. - PubMed.

- Buisson A, Joubert A, Montoriol PF, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for detecting and assessing ileal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 37:537-545.

- Oussalah A, Laurent V, Bruot O, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance without bowel preparation for detecting colonic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2010;59:1056- 1065.

- Panes J, Bouhnik Y, ReinischW, et al. Imaging techhiquws for assessment of inflammatory bowel disease: Joint ECCO-ESGAR evidence-based consensus guidelines. Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis. 2023:17(4):455-472.

| CROHN DISEASE | ULCERATIVE COLITIS |

| Intestinal preparation before examination | Colonic preparation before examination |

| T2-weighted HASTE/SSFSE axial and coronal | MR images axial plane with entirely colon and rectum[45] |

| Balanced steady state free procession gradient-echo (SSFPGR) – Coronal | T2-weighted coronal postcontrast additional images to verify if there are complications [45] |

| 3D Cinematic bSSFP- Coronal | |

| Delayed 3D T1-weighted post-contrast fat-saturated GRE (gradient recalled echo) - Axial | Sagittal T2-weighted MR images for anastomosis [45] |

| 3D T1-weighted pre-/post-contrast fat-saturated GRE (gradient recalled echo) –Dynamic- Coronal | Thin-section axial fat-suppression T2-weighted images for perianal disease[45] |

| DWI - Axial |

|

|

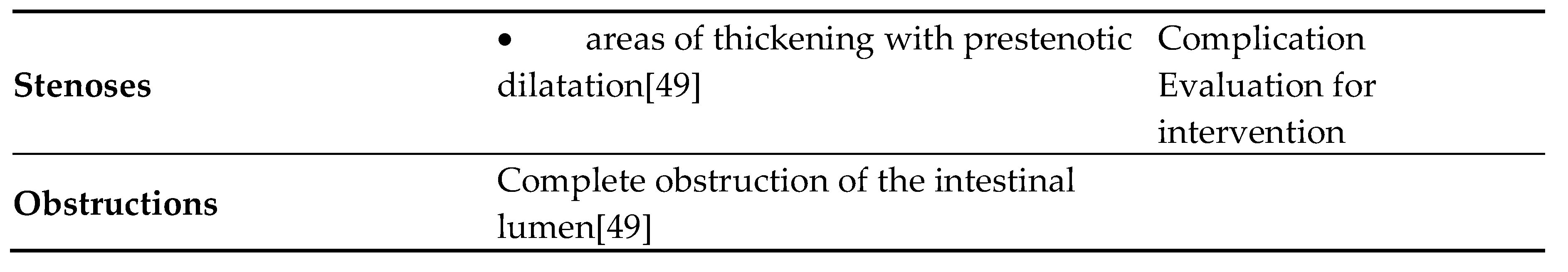

| Per-segment score | |||||

| MR features | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Mural thickness | <3mm | >3–5mm | >5–7mm | >7mm | |

| Mural T2 signal (oedema) | NORMAL | Minor increase | Moderate increase | Large increase | |

| Perimural T2 signal | NORMAL | Increased signal but no fluid | Small (≤2mm) fluid rim | Large (>2mm fluid rim) | |

| Contrast enhancement: pattern | NORMAL | N/A or homogeneous | Mucosal | Layered | |

| Haustral loss (colon only) | 0–5 cm | 5–15 cm | >15 cm | ||

| Multiplication factor for segmental score | |||||

| X1 | X2 | X3 | |||

| Length of disease in that segment | <5cm | 5-15cm | >15cm | ||

| Per patient score | |||||

| MR features | 0 | 5 | |||

| Lymph nodes | Absent | Present | |||

| Comb sign | Absent | Present | |||

| Abscess | Absent | Present | |||

| Fistula | Absent | Present | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).