Submitted:

26 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

4. Findings

4.1. Politics and Military in Colombo’s World-Class City Development

4.1.1. Political Imperative of Military Integration

- a)

- Capitalize on the military’s reputation for urgency and bypass procedures

- To leverage the strong reputation the military earned

“Right after the war, Defence Secretary hurried to develop Colombo. He had military under him and wanted it to team up with UDA for this. People were excited about this; they thought the military, with their dedication and discipline, could handle it all, just like during the war. So, they felt it was a smart move.”

- To Urgent Actions and Bypass Procedures

“Government wanted to make Colombo like Singapore. They wanted it fast. To speed up, they needed to control people’s resistance and skip formal procedures. If they had used UDA systems, they would have had to follow all the procurement rules, respect human rights, deal with many formalities, and so on. But, with this military approach, it’s just all about national security. You know, military doesn’t really care about procedures or mistakes; they just want to keep things moving. That’s why they put UDA under the Defense Ministry.”

“When military gets orders, they don’t question them. They just follow it. That’s how they won the war. So, if their boss says to demolish unauthorized structures, they do it right away without hesitation.”

- b)

- Keep the military loyal and control under the government

“We [the government] recruited a historically unprecedented number of people into the army during wartime. What can we do with them after the war? We don’t know what they’ll do or which side they’ll take if we lose control over them.”

“When a military officer became a ministry secretary, it was his duty to reward the military. So, he appointed them to various top positions in the government, including the UDA”.

- c)

- Building Trusted Go-Getters

“They [Gotabaya and his clan] thought the military could handle things better than us [professionals]. Maybe they didn’t trust us to get the job done right. If the military were there, everything would go smoothly.”

“So, like, I heard that the ex-UDA minister had some serious corruption issues. The President wanted to put a stop to it. And since the military wasn’t doing much after the war, he decided to hand UDA to the Defence Ministry.”

4.1.2. Military’s Role in the UDA and the URP

“So, every two weeks, we meet with the Defense Secretary. He gives us instructions and his ideas. You know, he’s out there every morning, checking things out, and if he spots something that needs development, he wants us to start right away. I remember after he called us to action, we rushed to the office; It was that urgent. His influence was huge from the start, and honestly, I don’t think any officer really got a chance to discuss things with him. Without him and his circle, we wouldn’t have pulled off these projects – their influence was definitely behind.”

“He ended the war as he had good administration. Gotabaya really wanted to improve Colombo. He wasn’t a typical politician; he wasn’t into all that political nonsense. But those around him pushed him into politics, convincing him to use projects to win votes. Eventually, all systems got politicized and corrupted.”

“We reported directly to him [Defence Secretary, Gotabaya]. UDA managed only our clerical stuff, but all the real decisions and priorities came from him and the MoD.”

“We understood UDA Act is very powerful, so we added some force and speed. Honestly, at first, we didn’t trust the UDA officers, so we brought in some reliable military officers who had worked with us during the war. Later, as they saw how we operated, many UDA officers joined us”.

“Bringing in military folks to oversee UDA people? That’s not a good idea. It was tough to coordinate with them; their strict ‘follow orders’ did not fit into us. They wanted us to act like them, but that just doesn’t fit our style.”

“The big issue with this [URP] project was its military control. They didn’t get the social side enough.”

“UDA was like a sleeping elephant—once we teamed up, they got things rolling. We showed them how to work smarter and faster. They used to clock in for just eight hours, but we were all about that shift.”

“Yeah, there was some military help, but they weren’t actually doing the demolishing. They just supported the police and UDA officers in the early stages of projects like 54 Waththa, 66 Waththa, and Wanathamulla. After the government changed in 2015, they were completely out of it.”

“They just handled operations, not planning or design. At that time, their operational involvement was helpful in moving unauthorized. They had a good reputation among the people.”

“When we went into Wanathamulla to clear some land, it felt like a battlefield—everyone surrounded us. They didn’t trust UDA’s housing promises. I climbed on a barrel and told them to believe us —we’d give them new houses. They like devils, especially women. But I didn’t give up. I kept going back, building trust. They believed us, not me, but my uniform. Finally, we got it done and cleared the land.”

“We don’t need the military for this. We’ve got the power to handle it ourselves! If there’s an issue, we call the police. We’ve never used the military for evictions; we just do relocations legally.”

“So back in 2015, the “yahapalanaya” government set up a commission to see if the military had any role in relocations. The new Secretary and a few folks from the Attorney General’s Department involved in this. They looked into people’s complaints and checked out military involvement but found nothing. Turns out, it was just a media rumour that the army was involved in the demolitions and relocations.”

4.2. Public Housing in World-Class Urban Development

4.2.1. The Elitist Perception of Underserved Communities

“If you are an urban planner, you serve the rich, not the poor. In an urban situation, poor people can’t afford to live. They can’t enjoy all the urban facilities. They have to leave the city, or they have to live in a different way. Urban is always for the rich, not for the poor. This is my personal opinion. As a Town Planner, I’m not serving the poor and serving the rich.”

Military officer—“We saw unauthorized structures like people unauthorizedly occupying government or somebody else property. To me, it’s a crime, injustice.”

Planner—“If it is unauthorized, it is unauthorized. They use common water taps and electricity without payments……. these people were drug addicts.”

“Although we were not much considered in development plans, these low-income people represent fifty percent of Colombo’s population. They are the engine running our economy in Colombo. They are the people who provide labour. They make Colombo live.”

“We wanted to keep these people in Colombo. Their contribution, especially for the informal sector, I mean labour like cleaning.”

4.2.2. Housing Strategies in World-Class ‘Slum-Free’ Mission

- (a)

- Regeneration of Privately Owned Prime Lands

“At that time, just after the war in 2009, investors, mostly Chinese [investors], came in and looked for projects. They were interested in the Port-City project, reclaiming the sea and building a new city like Dubai. Others were interested in projects adjacent to this new development. So, the defence secretary suggested Slave Island. It was a slum area.”

“They were not encroachers. Some or other, they had some legal right to their land. They were not unauthorized. But people who were living there had been stayed in the same situation, like slum or shanty people.”

4.2.3. Reclaiming Encroached Government Lands

- (a)

- The Target

“The government couldn’t make the city development, keeping these people at every junction. They were in Colombo 07, Borella, Narahenpita, Kollupitiya etc... etc. Therefore, there was a need for a solution”.

“Some of those were our early resettlement sites. In Premadasa5’s time, those people were given one or two perches of land. For example, when “Summit Flats” was constructed, many families were relocated elsewhere; currently, we call that resettlement land “Summit Waththa.” Similarly, when the “Keththarama” ground was being constructed, the people who were there were relocated; we call that settlement “Apple Waththa.”

“Though it was called at 68,000 families, we found there were only 56,000. We did a separate survey for our project. We prioritized the category of slums and shanties, which was around 40,000. Based on that, we programmed our project for 50,000.”

- (b)

- The Strategy

“We thought, why not give new houses to the encroachers and get some prime land to sell? We figured if we give one new house to a family in a settlement [underserved], we could get at least two perches of land. Those two perches are worth millions [SLR] in Colombo—like 2 million per perch! So, we’d use a quarter of the land for the new house and sell off three-quarters to investors. We also charge about one million for each new house. That way, we’re pocketing at least 2 million in profit. So, with this formula, the government doesn’t need to spend much, and the families [underserved] get brand new houses.”

“We gave priority to most potential lands. Lands we can sell out quickly,”

- (c)

- Process of Relocation

“There were no choices for people. Why do they need choices? We say you’re unauthorized. We explained to them we could take over their lands anyway and that if they went to court, they would get nothing. But now, if they agree, they could have at least a relocation house.”

“We decided on this 450 sq. ft. based on our costs. The other reason was that the majority, I mean more than 50 percent, lived in less than this in their whole life. However, we later increased this to 550 sq. ft. But we had to continue with this 450 sq. ft. for the 5,000 houses we built in the first stage, as we had already granted contracts early. Another thing is nowhere, I mean, NIRP or any other international policy, has a rule specifying 550 sq. ft. It depends on country to country. For example, in Mumbai in India, they use 275 sq. ft.”

“We targeted higher income. So, in the first stage, we relocated Narahenpita, Castle Street, Borella, Colpetty, Panchikawaththa, and Dematagoda, the most valued lands in Junctions. Yeah, we had to follow NIRP, but we made a few adjustments in our initial stage.”

“You know, even though people were living in unauthorized settlements, they just wouldn’t move on their own. There was some real reluctance. Some guys in the community, like gangsters and drug dealers—maybe five percent—really didn’t like our relocation program and stirred up resistance. Yeah, there were times when the military got involved, but it wasn’t like we were forcing anyone out violently.”

4.2.4. Challenges and Drawbacks in URP

“Low-income housing, by definition, means there are no regulations.”

“We weren’t worried about regulations. There was just so much pressure to get things done quickly! The higher-ups wanted fast results, and honestly, our team was just trying to please them. We talked about the rules, but they weren’t interested. It was all about speed and getting things done, not really thinking about the consequences.”

“We hold these houses until their kids are used to apartment life. We know, after that, they won’t want to go back to their parents’ shanties!”

“Honestly, we are utterly lost right now. We were just stuck in an endless loop. You know, We couldn’t sell our land and that 1Mn [SLR] thing just didn’t work out. We’re trapped in these houses, paying for water and electricity to WB and EB and also do maintenance with our staff. But families don’t pay for those bills. It’s been the same since 2013”

5. Discussion

5.1. Political Motivations and Development Approach

5.2. Shifting Perceptions of Urban Space and Social Exclusion

5.3. Militarization of Urban Governance

5.4. Public Housing and the Politics of Displacement

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

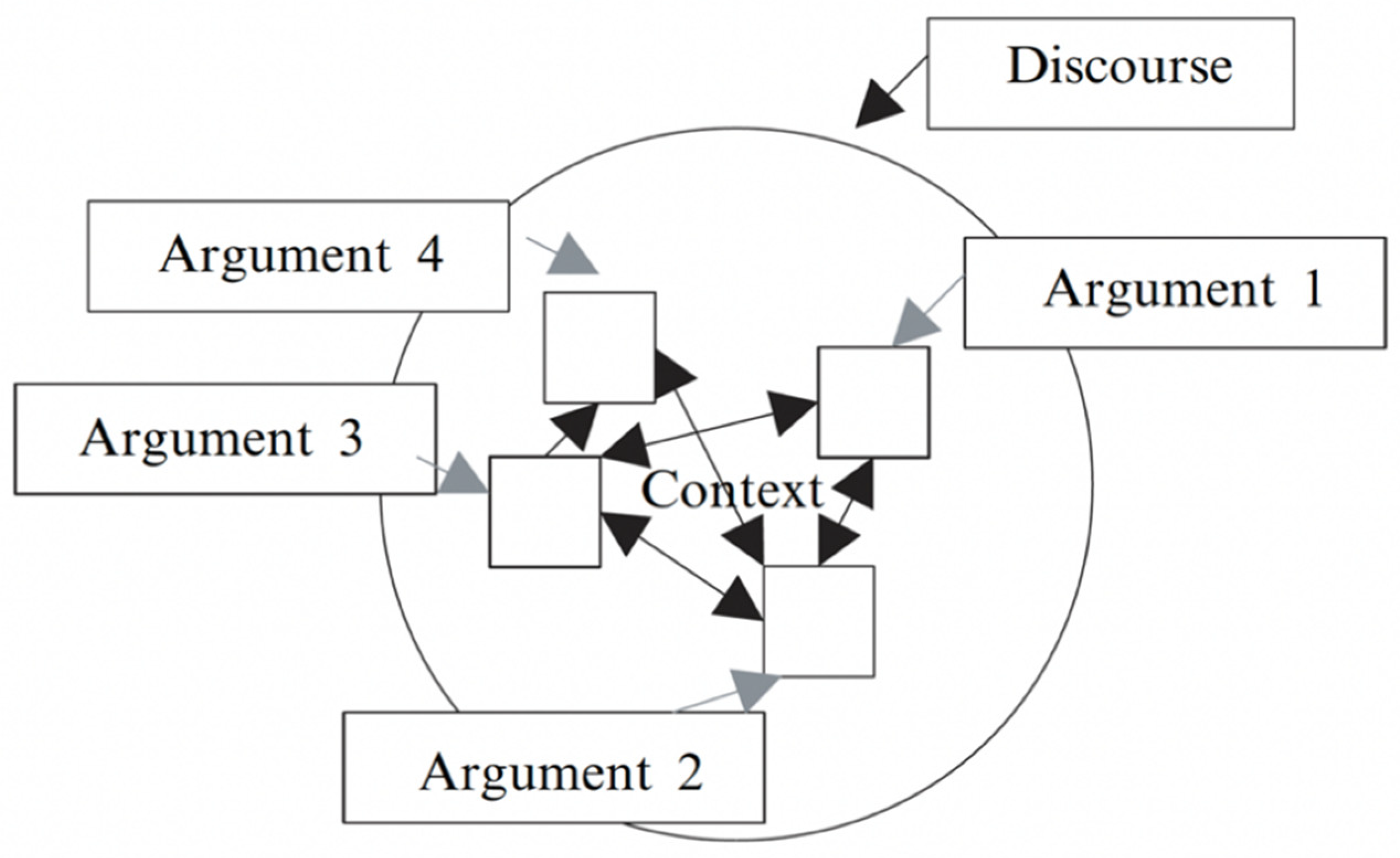

| Claim | Grounds | Warrant | Backing | Qualifier | Rebuttals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claim 1: Military integration was politically driven to transform Colombo into a world-class city. | Rajapaksa’s vision in “Mahinda Chintana Idiri Dekma: 2009” emphasized modernizing Colombo using models like Singapore and Dubai. | Urban transformation aligns with boosting foreign investment and the global image of Sri Lanka as a modern state. | Defense Secretary Gotabaya’s public speeches and statistical comparisons of Colombo with other cities. | Relocation of underserved settlements to high-rise housing was prioritized over addressing socio-economic complexities. | Critics argue this approach overlooked the needs and resistance of underserved communities. |

| Claim 2: The military’s reputation was leveraged to bypass bureaucratic inefficiencies. | Military viewed as disciplined and efficient, able to act swiftly and bypass red tape associated with civilian institutions like the UDA. | Public trust in the military’s ability to handle large-scale projects justified involving them in postwar urban initiatives. | Interviews highlighting public and respondent confidence in the military's effectiveness postwar. | “Military methods” were used as a justification for urgent development projects. | Bureaucratic processes and fundamental human rights were sidelined, causing social dissatisfaction. |

| Claim 3: The relocation program ignored socio-spatial justice for underserved communities. | Low-income communities were relocated from prime city areas to urban outskirts, disregarding their roles in the local economy. | Underserved communities are crucial for informal labor that sustains Colombo’s economic functionality. | Interviews revealed that 50% of Colombo’s population belongs to low-income sectors essential for economic stability. | Some relocation provided housing but did not address loss of urban accessibility and livelihood impacts. | Relocated families struggled with inadequate facilities and disconnection from urban opportunities. |

| Claim 4: Military involvement in the URP expedited urban transformation efforts. | Military’s command-driven culture accelerated housing programs and overcame bureaucratic delays. | Integration of military officers into UDA added efficiency and discipline to its operations. | Testimonials from military and civilian respondents on achieving housing targets quickly despite challenges. | Rapid implementation led to violations of planning standards and building regulations. | Long-term challenges arose from structural inadequacies and lack of adaptation support for relocated families. |

| Claim 5: Land reclaimed from slums was commercialized to fund urban projects. | Encroached lands deemed underutilized were prioritized for sale after relocation of low-income communities. | Selling prime land freed from unauthorized settlements was seen as a financially viable strategy to support urban development costs. | Respondents detailed financial formulas that emphasized profits from prime land redevelopment. | Limited success in selling these lands led to financial strain on the UDA. | Projects struggled with market value mismatches and lack of investor interest under restrictive government conditions. |

| Claim 6: Military involvement minimized resistance to relocation projects. | Visible military presence, uniformed brigadiers, and backup support helped suppress community resistance during the relocation process. | Public perception of the military as trustworthy fostered compliance with relocation plans. | Respondents highlighted that emotional pressure from military presence curtailed resistance to relocation programs. | Relocation compliance stemmed from fear of military authority, not voluntary agreement. | Forced compliance generated resentment and mistrust among displaced families. |

| Claim 7: The government bypassed bureaucratic protocols to expedite urban development. | Military methods allowed processes such as land acquisition and construction to proceed without traditional procedural constraints. | Centralized control enabled swift decision-making, streamlining complex urban planning initiatives. | Respondents detailed examples of procedures overridden to meet rapid urban transformation deadlines. | Justifications for bypassing protocols were often linked to national security concerns. | Procedural bypass led to regulatory violations and diminished stakeholder consultation. |

| Claim 8: Relocated families faced socio-cultural challenges in high-rise apartments. | Families reported difficulties adapting to small living spaces, limited privacy, and lack of community facilities. | High-rise apartments are structurally unsuitable for low-income families accustomed to single-story housing with communal living arrangements. | Interviews with resettled families and urban planners highlighted significant gaps in housing design and social adaptation strategies. | Challenges arose from limited planning for social mobilization components. | Relocated families often expressed dissatisfaction, citing impacts on their cultural and social lifestyle. |

| Claim 9: Relocation projects were influenced by political and elite motives. | Decision-makers prioritized land reclamation for commercial use over ensuring socio-economic well-being for displaced communities. | Political agendas often dictated project priorities, aligning urban development with elite investor interests. | Respondents identified favoritism in land allocation and inadequate compensation for displaced families. | Political influence skewed the project towards profit maximization rather than equitable urban planning. | Relocation processes reinforced inequality, marginalizing low-income families further. |

| Claim 10: Mismanagement and lack of coordination among agencies undermined project outcomes. | Limited collaboration between UDA and other government bodies like the CMA and utility providers delayed project implementation. | Effective urban development requires inter-agency coordination to address regulatory and infrastructural needs comprehensively. | Respondents discussed project delays due to conflicts with municipal authorities and insufficient support from infrastructure agencies. | Lack of coordination led to costly delays and substandard project execution. | Poor collaboration diminished the sustainability and functionality of completed housing projects. |

| Claim 11: Military involvement in planning created conflicts within the UDA. | Civilian UDA officers struggled to reconcile military-driven decision-making with established urban planning protocols. | Differences in organizational culture between military and civilian institutions hindered cohesive project execution. | Interviews revealed dissatisfaction among UDA professionals regarding military oversight in decision-making processes. | Military efficiency clashed with civilian emphasis on stakeholder inclusivity and legal compliance. | Conflicts between military and UDA professionals reduced overall project effectiveness. |

| Claim 12: The land sale strategy failed to achieve financial sustainability. | Unrealistic valuation methods, investor reluctance, and government-imposed restrictions hindered successful land sales. | Market-driven land development requires competitive pricing and investor-friendly terms. | Respondents cited discrepancies between market valuation and government-mandated pricing as critical barriers to land sales. | Failure to generate expected revenue left the UDA financially overburdened. | Unrealistic financial assumptions in project planning exposed systemic inefficiencies. |

| Claim 13: High-rise relocation disrupted the community’s social fabric. | Relocated families expressed difficulty maintaining pre-existing community bonds in the new apartment settings. | Strong community networks in low-income settlements are critical for mutual support and economic survival. | Interviews revealed significant isolation and loss of informal economic systems among relocated families. | Challenges are more pronounced in large housing complexes accommodating thousands of families. | Critics argue that lack of communal spaces exacerbates social isolation. |

| Claim 14: Decision-making processes lacked transparency and inclusivity. | Families and community leaders were not consulted during planning or implementation stages of relocation projects. | Transparent, participatory planning ensures equitable outcomes and mitigates resistance. | Respondents highlighted that families were often unaware of relocation timelines or compensation details. | Decisions were centralized, with little room for community feedback. | Lack of participation led to distrust and resentment among affected families. |

| Claim 15: Relocation projects ignored the economic needs of displaced families. | Relocated families lost proximity to urban job opportunities, informal markets, and transportation hubs. | Urban economic integration requires affordable housing within accessible locations. | Respondents emphasized the economic disruptions faced by families, particularly informal laborers. | Some relocation projects attempted to retain proximity but were insufficient to meet the scale of the issue. | Economic displacement was an unintended but severe consequence of the relocation program. |

| Claim 16: Public perception of military involvement was polarized. | While some viewed military involvement as efficient, others criticized it as coercive and undemocratic. | The dual narrative reflects the complexity of militarized urban development in postwar contexts. | Respondents shared mixed views on the appropriateness of military-led development initiatives. | The military’s role was celebrated for efficiency but critiqued for undermining civilian governance. | Polarized perceptions hinder unified support for such initiatives. |

| Claim 17: Infrastructure challenges limited the success of relocation housing projects. | Relocated families faced inadequate access to utilities like water, electricity, and waste management. | Functional urban housing requires robust infrastructural support systems. | Respondents described persistent issues with maintenance and service delivery in high-rise housing complexes. | Infrastructure gaps were attributed to rushed planning and limited inter-agency collaboration. | Relocation housing projects fell short of providing adequate living conditions. |

| Claim 18: Long-term sustainability of relocation projects is uncertain. | Financial and operational challenges raise doubts about the feasibility of maintaining high-rise housing complexes. | Sustainable urban development requires long-term planning and community ownership. | Respondents noted arrears in housing payments and unresolved legal issues affecting project viability. | Initial success in relocating families overshadowed by concerns about maintenance and ownership. | Critics argue that current models are not scalable or sustainable in the long run. |

| 1 | Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte is the official administrative and legislative capital of Sri Lanka, housing the Parliament and key government offices. Colombo, while commonly referred to as the capital due to its role as the commercial and economic center, does not hold this status in a legal sense. |

| 2 | Governmentality refers to the ways in which the state governs not only through direct control but also by shaping societal norms, expectations, and behaviors through policies, institutions, and discourses [89]. |

| 3 | The reduction in active military involvement during the Sirisena regime was influenced by his political manifesto, which emphasized the 'Yahapalanaya' (Good Governance) initiative, advocating democratic reforms and restoring civilian oversight by limiting military engagement in non-military activities such as urban development. |

| 4 | “Actions involving the subdivision, allocation, moulding, and building on land have a substantive political character: they always influence rights, values, and power relations to some extent. This influence may be direct or indirect, or intentional or unintentional, but in all cases, the effect of spatially localising functions, buildings, and populations is a ‘relative redistribution’. The distribution of costs and gains, windfalls and wipe-outs, and duties and rights is not equal and impartial: someone is advantaged, someone else is disadvantaged; in the competition for urban space, someone ‘wins’, while another ‘loses’. It is this distribution that is substantively political” (Chiodelli & Scavuzzo, 2013). |

| 5 | Premadasa was a former Sri Lankan President and housing minister in Sri Lanka from 1983 to 1987. |

References

- Heo, I. Neoliberal developmentalism in South Korea: Evidence from the green growth policymaking process. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2015, 56 (3), 351–364. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P. Nationalist Thought and the Colonial World; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1993.

- Abeyasekera, A.; Maqsood, M.; Perera, I.; Sajjad, F.; Spencer, J. Discipline in Sri Lanka, punish in Pakistan: Neoliberalism, governance, and housing compared. J. Br. Acad. 2019, 7 (s2), 215–244. [CrossRef]

- Rasnayake, S. The discourse of “slum-free” city: A critical review of the project of city beautification in Colombo, Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka J. Sociol. 2019, 1 (1), 87–120.

- Amarasuriya, H.; Spencer, J. “With that, discipline will also come to them”: The politics of the urban poor in postwar Colombo. Curr. Anthropol. 2015, 56 (S11), S66–S75. [CrossRef]

- Grimwood, T. The rhetoric of urgency and theory-practice tensions. Eur. J. Soc. Work 2022, 25 (1), 15–25. [CrossRef]

- van Wijk, J.; Fischhendler, I. The construction of urgency discourse around mega-projects: the Israeli case. Policy Sci. 2017, 50 (3), 469–494. [CrossRef]

- Perera, I.; Spencer, J. Beautification, governance, and spectacle in post-war Colombo. In Controlling the Capital: Political Dominance in the Urbanizing World; Goodfellow, T., David, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023; pp 203–233.

- Kumar, S.; Pallathucheril, V.G. Analyzing planning and design discourses. Environ. Plann. B: Plann. Des. 2004, 31 (6), 829–846. [CrossRef]

- Eisenstadt, S.N. Traditional Patrimonialism and Modern Neopatrimonialism, 1st ed.; Sage Publications: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1973; Vol. 1.

- Soja, E.W. The city and spatial justice. Spatial Justice 2009, 1, 1–5.

- Park, B.-G.; Hill, R.C.; Saito, A. Locating Neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing Spaces in Developmental States; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Watts, M. Developmentalism. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp 123–130.

- Regmi, K.D. Five decades of neoliberal developmentalism in “Least Developed Countries”: A decolonial critique. J. Int. Dev. 2024, early view. [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.; Yeo, E. Reproduction, discipline, inequality: Critiquing East-Asian developmentalism through a strategic-relational examination of Singapore’s Central Provident Fund. Glob. Soc. Policy 2022, 22 (3), 483–502. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The urban process under capitalism: A framework for analysis. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1978, 2 (1–4), 101–131. [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The urban illusion. In Bononno, R., Trans.; The Urban Revolution; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1970; pp 151–164.

- Afenah, A. Conceptualizing the effects of neoliberal urban policies on housing rights: An analysis of the attempted unlawful forced eviction of an informal settlement in Accra, Ghana. Available online: www.ucl.ac.uk (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Harvey, D. A Brief History of Neoliberalism; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005.

- Ball, M.; Harloe, M. Rhetorical barriers to understanding housing provision: What the ‘provision thesis’ is and is not. Hous. Stud. 1992, 7 (1), 3–15. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.L.; Li, W.D. Neoliberalism, the developmental state, and housing policy in Taiwan. In Locating Neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing Spaces in Developmental States; Park, B.-G., Hill, R.C., Saito, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp 196–224. [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Cities and the geographies of “actually existing neoliberalism.” Antipode 2002, 34 (3), 349–379. [CrossRef]

- Gürel, B.U. Dispossession and development in the neoliberal era. Ankara Univ. SBF Derg. 2019, 74 (3), 983–1001. [CrossRef]

- Aveline, N.; Elgar, E. The financialization of real estate in megacities and its variegated trajectories in East Asia. In Handbook of Megacities and Megacity-Regions; Labbé, D., Sorensen, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp 395–410. [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.D. Developmental neoliberalism and hybridity of the urban policy of South Korea. In Locating Neoliberalism in East Asia: Neoliberalizing Spaces in Developmental States; Park, B.-G., Hill, R.C., Saito, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp 86–113. [CrossRef]

- Lakshman, W.D. The IMF-World Bank intervention in Sri Lankan economic policy: Historical trends and patterns. Soc. Sci. 1985, 13 (2), 3–29. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3520187.

- DeVotta, N. Sri Lanka’s structural adjustment program and its impact on Indo-Lanka relations. Univ. Calif. Press 1998, 38 (5), 457–473.

- DeVotta, N. Majoritarian politics in Sri Lanka: The roots of pluralism breakdown. Unpublished manuscript, 2017.

- Athukorala, P.C.; Jayasuriya, S. Victory in war and defeat in peace: Politics and economics of post-conflict Sri Lanka. Asian Econ. Pap. 2015, 14 (3), 22–54. [CrossRef]

- Fuglerud, O. Manifesting Sri Lankan megalomania: The Rajapakses’ vision of empire and of a clean Colombo. In Urban Utopias; Kuldova, T., Varghese, M.A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; 1st ed.; Palgrave Studies in Urban Anthropology; pp 119–138. [CrossRef]

- Nyaluke, D. The African basis of democracy and politics for the common good: A critique of the neopatrimonial perspective. Taiwan J. Democr. 2014, 10 (2). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341462918.

- O’Neil, T. Neopatrimonialism and public sector performance and reform: Background note. Available online: www.odi.org.uk/PPPG/politics_and_governance/what_we_do/Politics_aid/Governance_Aid_Poverty.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Weber, M. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology, 1st ed.; Roth, G., Wittich, C., Eds.; University of California Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1978.

- Munro, A. Power. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. (accessed on 4 April 2025). https://www.britannica.com/topic/power-political-and-social-science.

- Skigin, P. Neopatrimonialism: The Russian regime through a Weberian lens. In Ideology after Union: Political Doctrines, Discourses, and Debates in Post-Soviet Societies; Alexander, E., Mykhailo, M., Eds.; Ibidem Press: Stuttgart, Germany, 2020; pp 93–110.

- Doidge, M. “Either everyone was guilty or everyone was innocent”: The Italian power elite, neopatrimonialism, and the importance of social relations. J. Sport Soc. Issues 2018, 42 (2), 115–131. [CrossRef]

- von Soest, C. Neopatrimonialism: A Critical Assessment. In Elgar Handbook on Governance and Development; Hout, W., Hutchison, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2021.

- Roth, G. Personal rulership, patrimonialism, and empire-building in the new states. World Polit. 1968, 20 (2), 194–206. [CrossRef]

- Erdmann, G.; Engel, U. Neopatrimonialism revisited—beyond a catch-all concept. Available online: www.giga-hamburg.de (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Theobald, R. Patrimonialism. World Polit. 1982, 34 (4), 548–559. [CrossRef]

- Clapham, C. Third World Politics: An Introduction, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis e-Library: London, UK, 1985.

- Bratton, M.; van de Walle, N. Democratic Experiments in Africa; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Wickramaratne, J. The executive presidency: A left perspective. In Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems, and Prospects; Welikala, A., Ed.; Centre for Policy Alternatives: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2015; Vol. 2, pp 897–930.

- Venugopal, R. Neoliberalism as concept. Econ. Soc. 2015, 44 (2), 165–187. [CrossRef]

- Wickramasinghe, N. Mahinda Rajapaksa: From populism to authoritarianism. In Contemporary Populists in Power; Dieckhoff, A., Jaffrelot, C., Massicard, E., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. The Sciences Po Series in International Relations and Political Economy. https://link.springer.com/bookseries/14411.

- International Crisis Group. Sri Lanka: A Bitter Peace; Crisis Group Asia Briefing No. 99; International Crisis Group: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2010; pp 1–22. Available online: www.dmhr.gov.lk (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Rajasingham-Senanayake, D. Is post-war Sri Lanka following the “military business model”? Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2011, 46 (14), 27–30.

- Riggs, F.W. Thailand: The Modernization of a Bureaucratic Polity; East-West Center Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1966.

- Ghertner, D.A. Rule by Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi. In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global; Roy, A., Ong, A., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp 279–306. [CrossRef]

- Bach, D.C. Patrimonialism and neopatrimonialism: Comparative trajectories and readings. Commonw. Comp. Polit. 2011, 49 (3), 275–294. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.H.; Rosberg, C.G. Personal rule: Theory and practice in Africa. Comp. Polit. 1984, 16 (4), 421–442.

- Ricks, J. Agents, principals, or something in between? Bureaucrats and policy control in Thailand. Available online: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/soss_research (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Mills, W.C. The Power Elite, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1956.

- Soja, E.W. Building a spatial theory of justice. In Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010.

- Soja, E.W. Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places; Blackwell Publishers Inc.: Malden, MA, USA, 1996.

- Wang, S.; Gu, K. Spatial Justice and Planning: Reshaping Social Housing Communities in a Changing Society; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Toward a Theory of Spatial Justice. In Theorizing Green Urban Communities; Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Western Political Science Association, 28 March 2013.

- Lefebvre, H. The Production of Space; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1974.

- Chiodelli, F.; Scavuzzo, L. Power in space: Space regulation amidst techniques and politics in the Global South. In Cities to Be Tamed? Spatial Investigations across the Urban South; LetteraVentidue: Siracusa, Italy, 2013. https://www.ebsco.com/terms-of-use.

- Lefebvre, H.; Kofman, E.; Lebas, E. Writings on Cities (Le Droit à la Ville); Kofman, E., Lebas, E., Trans.; Blackwell Publishers Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2000.

- Mazza, L. Plan and constitution – Aristotle’s Hippodamus: Towards an ‘ostensive’ definition of spatial planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2009, 80 (2), 113–141. [CrossRef]

- Flyvbjerg, B. The dark side of planning: Rationality and “Realrationalität.” In Explorations in Planning Theory; Mandelbaum, S.J., Mazza, L., Burchell, R.W., Eds.; Center for Urban Policy Research Press: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 1996; pp 383–394. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/244994127.

- van Dijk, T.A. Discourse as Structure and Process; Discourse Studies: A Multidisciplinary Introduction, Vol. 1; Sage Publications: London, UK, 1997.

- van Eemeren, F.H.; Grootendorst, R.; Snoeck Henkemans, F. Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1996; Digital printing by Routledge, 2009.

- Toulmin, S. The Uses of Argument, Updated ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003.

- Gasper, D.R.; George, R.V. Planning and design. Environ. Plann. B: Plann. Des. 1998, 25, 367–390.

- Clark, C.M.; Sharf, B.F. The dark side of truth(s): Ethical dilemmas in researching the personal. Qual. Inq. 2007, 13 (3), 399–416. [CrossRef]

- Castleden, H.; Morgan, V.S.; Lamb, C. “I spent the first year drinking tea”: Exploring Canadian university researchers’ perspectives on community-based participatory research involving Indigenous peoples. Can. Geogr. 2012, 56 (2), 160–179. [CrossRef]

- Department of National Planning - Sri Lanka. Mahinda Chintana: Vision for a New Sri Lanka; Government of Sri Lanka: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2009.

- Herter, M. Development as spectacle: Understanding post-war urban development in Colombo, Sri Lanka: The case of Arcade Independence Square. In Geographien Südasiens; Heidelberg Asian Studies Publishing: Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpura, K.N.; Brown, B.; Chan, L. (Dis)connecting Colombo: Situating the megapolis in postwar Sri Lanka. Prof. Geogr. 2020, 72 (1), 165–179. [CrossRef]

- Radicati, A. World class from within: Aspiration, connection and brokering in the Colombo real estate market. Environ. Plann. D: Soc. Space 2022, 40 (1), 118–137. [CrossRef]

- Herath, D.; Lakshman, R.W.D.; Ekanayake, A. Urban resettlement in Colombo from a wellbeing perspective: Does development-forced resettlement lead to improved wellbeing? J. Refugee Stud. 2017, 30 (4), 554–579. [CrossRef]

- Korala, A. Included to be excluded? A critical assessment on the inclusion of slum and shanty dwellers into the urban regeneration project. Univ. Colombo Rev. 2021, 2 (2), 133–150.

- Perera, I.; Ganeshathasa, L.; Samaraarachchi, U.; Ruwanpathirana, T. Forced Evictions in Colombo: The Ugly Price of Beautification; Centre for Policy Alternatives: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2014.

- Kim, S.-H.; Shin, H.B. The developmental state, speculative urbanization and the politics of displacement in gentrifying Seoul. In Developmentalist Cities? Interrogating Urban Developmentalism in East Asia; Doucette, J., Park, B.-G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Vol. 130, pp 245–270. https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047127.

- Brenner, N.; Marcuse, P.; Meyer, M. Cities for people, not for profit – an introduction. In Cities for People, Not Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City; Brenner, N., Marcuse, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp 1–10.

- Ghertner, A.D. Analysis of new legal discourse behind Delhi’s slum demolitions. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2008, 43 (20), 59–66.

- Ghertner, A.D. Nuisance talk: Middle-class discourses of a slum-free Delhi. In Ecologies of Urbanism in India: Metropolitan Civility and Sustainability; Rademacher, A.M., Sivaramakrishnan, K., Eds.; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, 2013; pp 249–275. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ualberta/detail.action?docID=1187364.

- Colombo Telegraph. No mercy for shanty dwellers challenging UDA from de facto CJ. Available online: https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/no-mercy-for-shanty-dwellers-challenging-uda-from-de-facto-cj/ (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Siddiqa, A. Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2007.

- Demir, S.; Bingöl, O. From military tutelage to civilian control: An analysis of the evolution of Turkish civil–military relations. Br. J. Middle East. Stud. 2020, 47 (2), 172–191. [CrossRef]

- Sarigil, Z. Civil-military relations beyond dichotomy: With special reference to Turkey. Turk. Stud. 2011, 12 (2), 265–278. [CrossRef]

- Crouch, H. Military-civilian relations in Indonesia in the late Soeharto era. Pac. Rev. 1988, 1 (4), 353–362. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D. The New Imperialism, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Schouten, P. David Harvey on the geography of capitalism, understanding cities as polities and shifting imperialisms. Available online: http://www.theory-talks.org/2008/10/theory-talk-20-david-harvey.html (accessed on 4 April 2025).

- Graham, S. Cities Under Siege: The New Military Urbanism, Paperback ed.; Verso: London, UK, 2011.

- Levine, D.; Aharon-Gutman, M. Cities on the edge: How Bat Yam challenges the common social implications of urban regeneration. J. Urban Des. 2023, 28 (5), 547–569. [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Governmentality. In The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality; Burchell, G., Gordon, C., Miller, P., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1991; pp 87–104.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).