Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

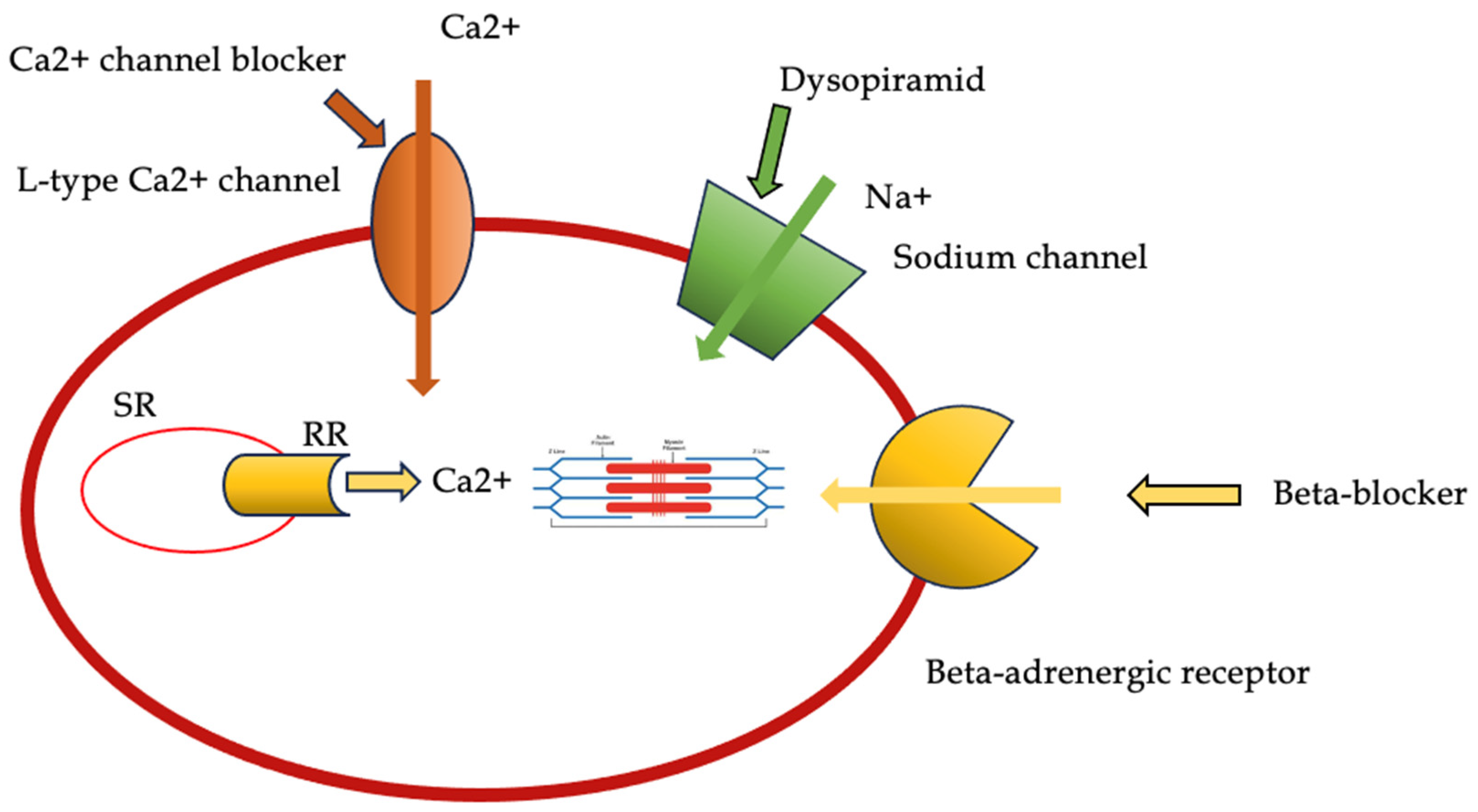

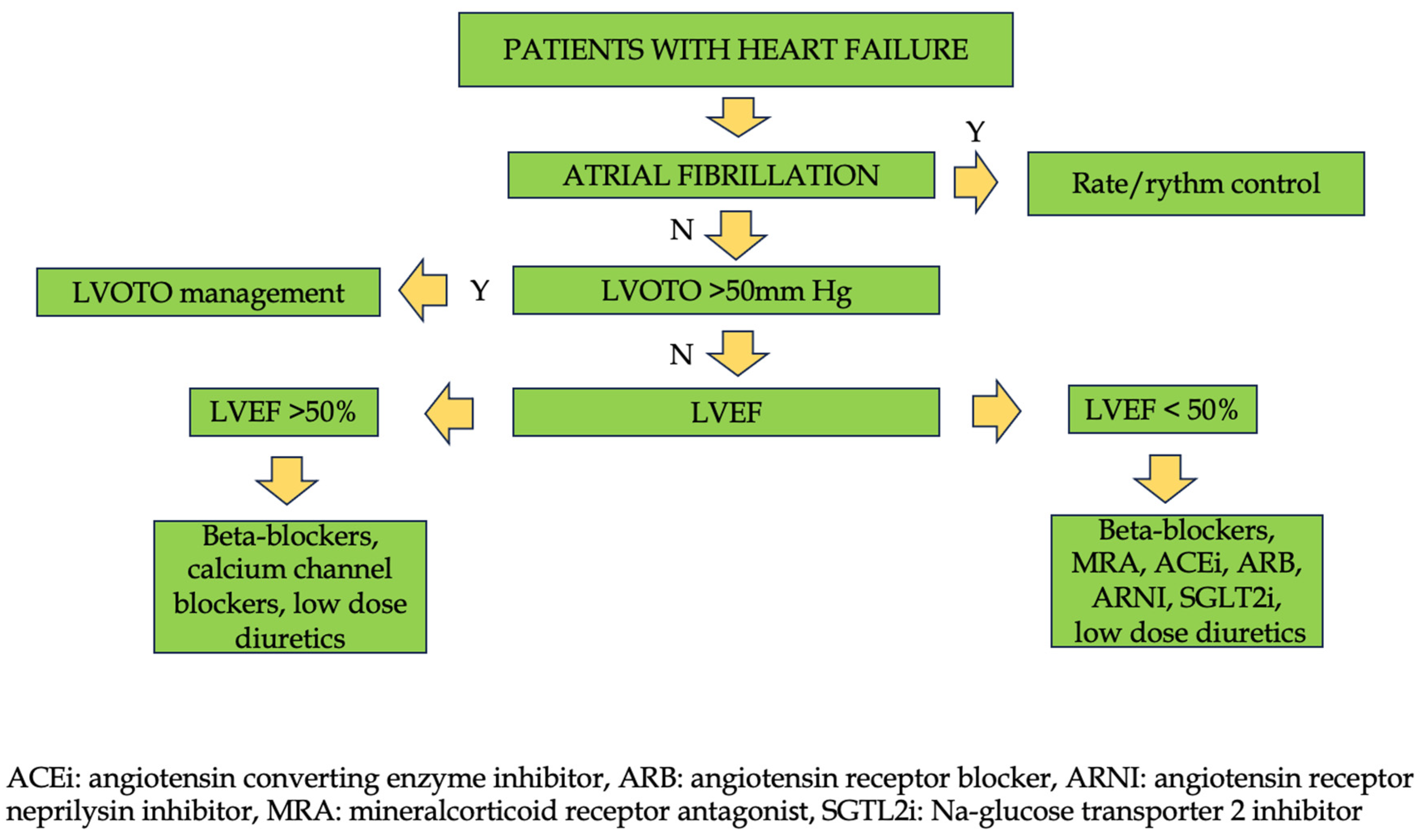

2. Pharmacological Therapy in Obstructive Forms

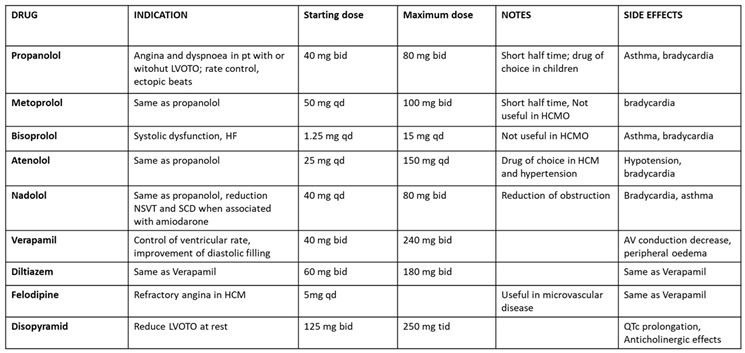

2.1. Beta-Blockers and Non-Dihydropiridine Calcium Channel Blockers

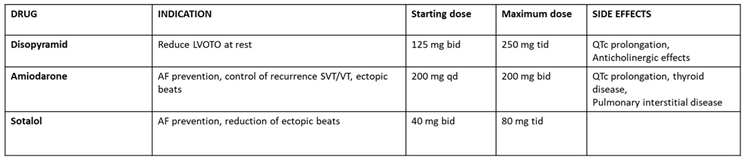

2.2. Disopyramid

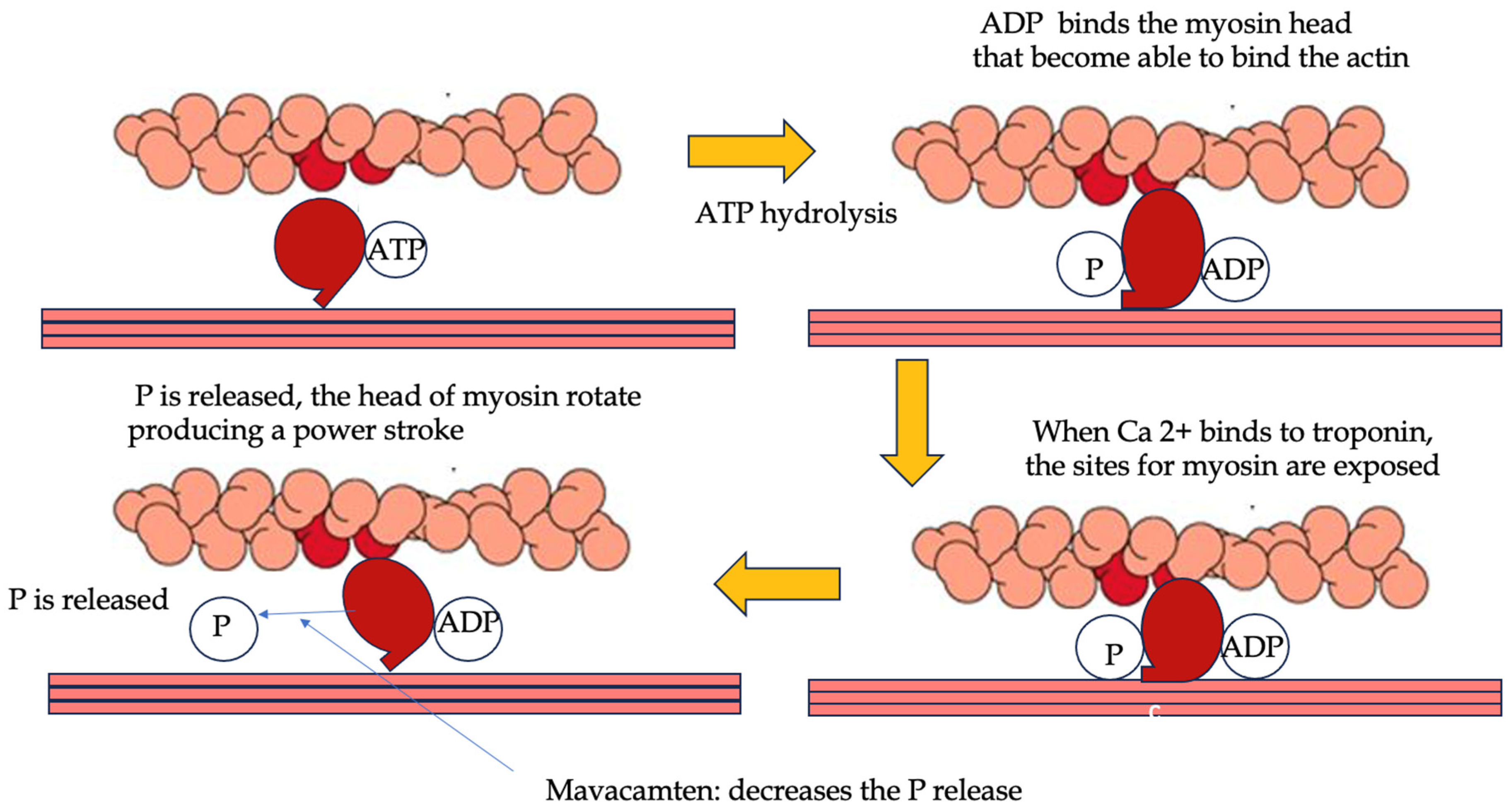

2.3. Cardiac Myosin Modulators: Mavacamten and Aficamten

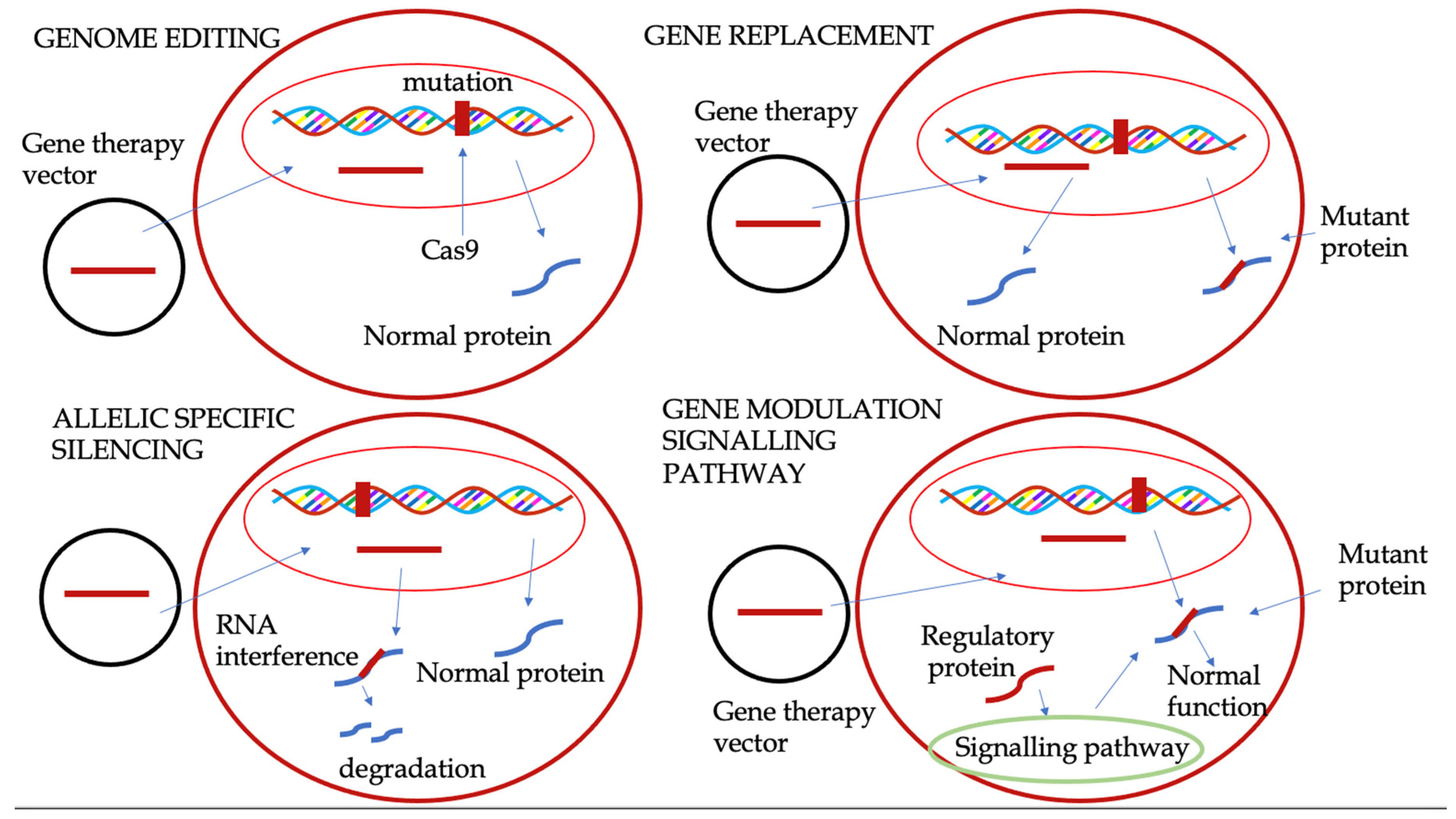

3. Gene Therapy

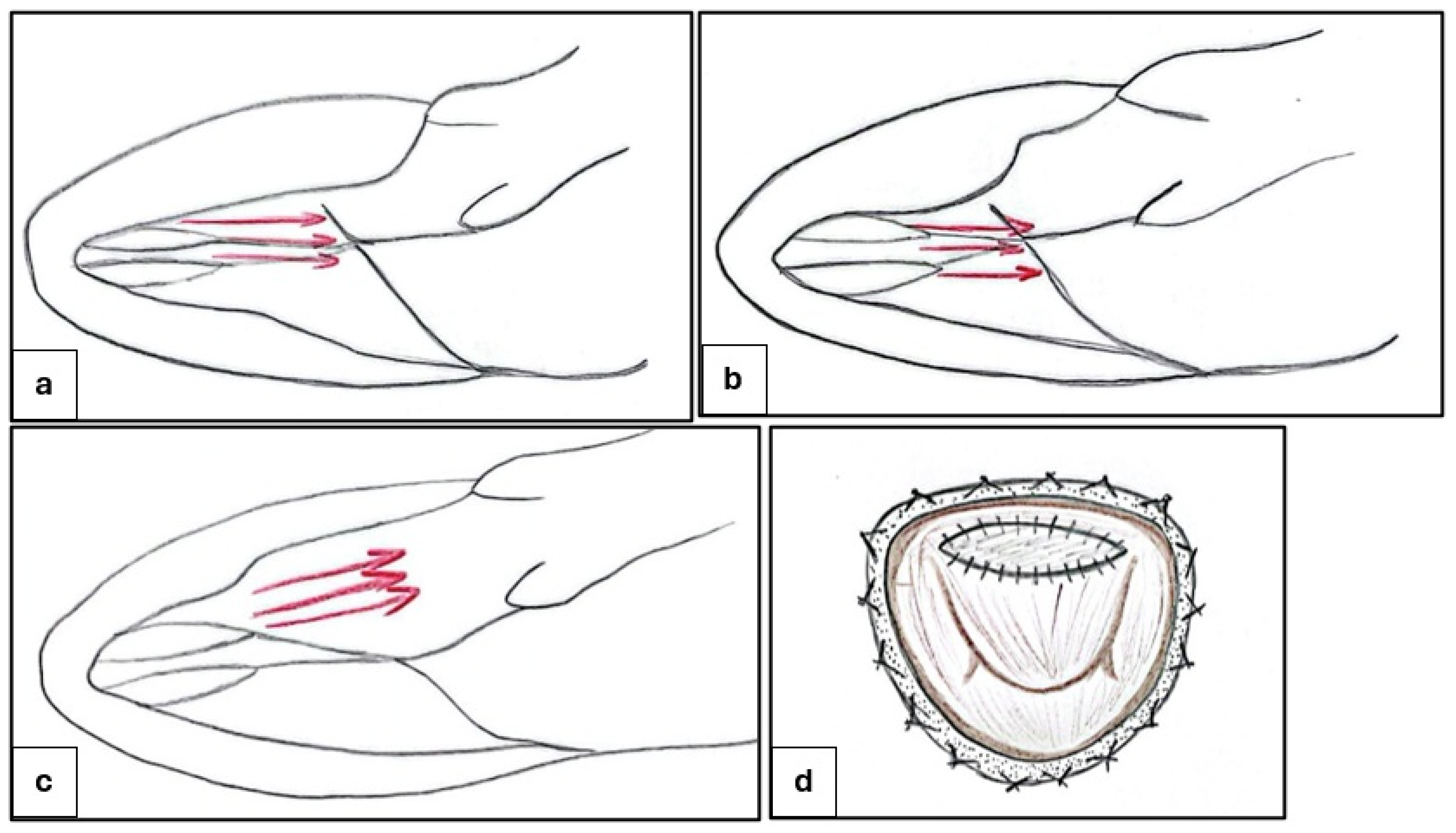

4. Invasive Strategies: Surgery and Alcohol Septal Ablation

5. Management of Non-Obstructive Forms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuohy, C.V.; Kaul, S.; Song, H.K.; Nazer, B.; Heitner, S.B. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the future of treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2020, 22, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammirati, E.; Contri, R.; Coppini, R.; Cecchi, F.; Frigerio, M.; Olivotto, I. Pharmacological treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: current practice and novel perspectives. Eur J Heart Fail 2016, 18, 1106–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbelo, E.; Protonotarios, A.; Gimeno, J.R.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Basso, C.; Bezzina, C.R.; Biagini, E.; Blom, N.A.; de Boer, R.A.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 3503–3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlo, M.; Gagno, G.; Baritussio, A.; Bauce, B.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Cipriani, A.; Castelletti, S.; Dellegrottaglie, S.; Guaricci, A.I.; et al. Clinical application of CMR in cardiomyopathies: evolving concepts and techniques : A position paper of myocardial and pericardial diseases and cardiac magnetic resonance working groups of Italian society of cardiology. Heart Fail Rev 2023, 28, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forleo, C.; D'Erchia, A.M.; Sorrentino, S.; Manzari, C.; Chiara, M.; Iacoviello, M.; Guaricci, A.I.; De Santis, D.; Musci, R.L.; La Spada, A.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing detects novel gene-phenotype associations and expands the mutational spectrum in cardiomyopathies. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0181842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, M.; Porcari, A.; Pagura, L.; Cameli, M.; Vergaro, G.; Musumeci, B.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Crotti, L.; Imazio, M.; et al. A national survey on prevalence of possible echocardiographic red flags of amyloid cardiomyopathy in consecutive patients undergoing routine echocardiography: study design and patients characterization-the first insight from the AC-TIVE Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, F.; Joyce, T.; Lorenzoni, V.; Guaricci, A.I.; Pavon, A.G.; Fusini, L.; Andreini, D.; Rabbat, M.G.; Aquaro, G.D.; Abete, R.; et al. AI Cardiac MRI Scar Analysis Aids Prediction of Major Arrhythmic Events in the Multicenter DERIVATE Registry. Radiology 2023, 307, e222239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggiano, A.; Del Torto, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Muscogiuri, G.; Fusini, L.; Babbaro, M.; Collevecchio, A.; Mollace, R.; Scafuri, S.; Mushtaq, S.; et al. Role of CMR Mapping Techniques in Cardiac Hypertrophic Phenotype. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, S.; Chiesa, M.; Novelli, V.; Sommariva, E.; Biondi, M.L.; Manzoni, M.; Florio, A.; Lampus, M.L.; Avallone, C.; Zocchi, C.; et al. Role of advanced CMR features in identifying a positive genotype of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2024, 417, 132554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagura, L.; Porcari, A.; Cameli, M.; Biagini, E.; Canepa, M.; Crotti, L.; Imazio, M.; Forleo, C.; Pavasini, R.; Limongelli, G.; et al. ECG/echo indexes in the diagnostic approach to amyloid cardiomyopathy: A head-to-head comparison from the AC-TIVE study. Eur J Intern Med 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrabba, N.; Amico, M.A.; Guaricci, A.I.; Carella, M.C.; Maestrini, V.; Monosilio, S.; Pedrotti, P.; Ricci, F.; Monti, L.; Figliozzi, S.; et al. CMR Mapping: The 4th-Era Revolution in Cardiac Imaging. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dicorato, M.M.; Basile, P.; Muscogiuri, G.; Carella, M.C.; Naccarati, M.L.; Dentamaro, I.; Guglielmo, M.; Baggiano, A.; Mushtaq, S.; Fusini, L.; et al. Novel Insights into Non-Invasive Diagnostic Techniques for Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Critical Review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carella, M.C.; Forleo, C.; Caretto, P.; Naccarati, M.L.; Dentamaro, I.; Dicorato, M.M.; Basile, P.; Carulli, E.; Latorre, M.D.; Baggiano, A.; et al. Overcoming Resistance in Anderson-Fabry Disease: Current Therapeutic Challenges and Future Perspectives. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prondzynski, M.; Mearini, G.; Carrier, L. Gene therapy strategies in the treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Pflugers Arch 2019, 471, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.W.; Lumish, H.S.; Sewanan, L.R.; Shimada, Y.J.; Maurer, M.S.; Weiner, S.D.; Clerkin, K.J. Evolving Strategies for the Management of Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Card Fail 2024, 30, 1136–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.J.; Desai, M.Y.; Nishimura, R.A.; Spirito, P.; Rakowski, H.; Towbin, J.A.; Dearani, J.A.; Rowin, E.J.; Maron, M.S.; Sherrid, M.V. Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colan, S.D. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in childhood. Heart Fail Clin 2010, 6, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoerger, D.M.; Weyman, A.E. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy: mechanism of obstruction and response to therapy. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2003, 4, 199–215. [Google Scholar]

- Dybro, A.M.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Nielsen, R.R.; Andersen, M.J.; Jensen, M.K.; Poulsen, S.H. Randomized Trial of Metoprolol in Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021, 78, 2505–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Omote, K. Beta-Blockers and Exercise Hemodynamics in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022, 79, 1576–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosing, D.R.; Idanpaan-Heikkila, U.; Maron, B.J.; Bonow, R.O.; Epstein, S.E. Use of calcium-channel blocking drugs in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 1985, 55, 185B–195B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltes, S.; Lopes, L.R. New perspectives in the pharmacological treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2020, 39, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, M.S.; Rowin, E.J.; Olivotto, I.; Casey, S.A.; Arretini, A.; Tomberli, B.; Garberich, R.F.; Link, M.S.; Chan, R.H.M.; Lesser, J.R.; et al. Contemporary Natural History and Management of Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 67, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S.E.; Rosing, D.R. Verapamil: its potential for causing serious complications in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1981, 64, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, G.; Chiarito, M.; Puscas, T.; Bacher, A.; Donal, E.; Reant, P.; Condorelli, G.; Hagege, A.; Cardiology, R.w.g.o.t.F.S.o. Comparative Influences of Beta blockers and Verapamil on Cardiac Outcomes in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2025, 235, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Nadales, A.; Anampa-Guzman, A.; Khan, A. Disopyramide for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Cureus 2019, 11, e4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinden, N.J.; Coons, J.C. Disopyramide for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Pragmatic Reappraisal of an Old Drug. Pharmacotherapy 2015, 35, 1164–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrid, M.V.; Massera, D. Disopyramide for symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2025, 423, 133030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrid, M.V.; Barac, I.; McKenna, W.J.; Elliott, P.M.; Dickie, S.; Chojnowska, L.; Casey, S.; Maron, B.J. Multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of disopyramide in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005, 45, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrid, M.V.; Shetty, A.; Winson, G.; Kim, B.; Musat, D.; Alviar, C.L.; Homel, P.; Balaram, S.K.; Swistel, D.G. Treatment of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy symptoms and gradient resistant to first-line therapy with beta-blockade or verapamil. Circ Heart Fail 2013, 6, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, M.; Ikeda, S.; Shigematsu, Y. Advances in medical treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Cardiol 2014, 64, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maurizi, N.; Chiriatti, C.; Fumagalli, C.; Targetti, M.; Passantino, S.; Antiochos, P.; Skalidis, I.; Chiti, C.; Biagioni, G.; Tomberli, A.; et al. Real-World Use and Predictors of Response to Disopyramide in Patients with Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forleo, C.; Carella, M.C.; Basile, P.; Mandunzio, D.; Greco, G.; Napoli, G.; Carulli, E.; Dicorato, M.M.; Dentamaro, I.; Santobuono, V.E.; et al. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cardiomyopathies in the Light of New Guidelines: A Focus on Tissue Mapping. J Clin Med 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, A.; Lester, S.J.; Stendahl, J.C.; Hegde, S.M.; Sehnert, A.J.; Balaratnam, G.; Shah, A.; Fox, S.; Wang, A. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Mavacamten in Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Interim Results of the PIONEER-OLE Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2024, 13, e030607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivotto, I.; Oreziak, A.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Abraham, T.P.; Masri, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Saberi, S.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Wheeler, M.T.; Owens, A.; et al. Mavacamten for treatment of symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (EXPLORER-HCM): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.Y.; Owens, A.; Wolski, K.; Geske, J.B.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Sherrid, M.; Cremer, P.C.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Tower-Rader, A.; et al. Mavacamten in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Referred for Septal Reduction: Week 56 Results From the VALOR-HCM Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol 2023, 8, 968–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, F.; Oreziak, A.; Choudhury, L.; Saberi, S.; Fermin, D.; Wheeler, M.T.; Abraham, T.P.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Zwas, D.R.; Masri, A.; et al. Mavacamten Treatment for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Interim Results From the MAVA-LTE Study, EXPLORER-LTE Cohort. JACC Heart Fail 2024, 12, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.T.; Jacoby, D.; Elliott, P.M.; Saberi, S.; Hegde, S.M.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Myers, J.; Sehnert, A.J.; Edelberg, J.M.; Li, W.; et al. Effect of beta-blocker therapy on the response to mavacamten in patients with symptomatic obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail 2023, 25, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismayl, M.; Abbasi, M.A.; Marar, R.; Geske, J.B.; Gersh, B.J.; Anavekar, N.S. Mavacamten Treatment for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Curr Probl Cardiol 2023, 48, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishev, D.; Fabara, S.; Loseke, I.; Alok, A.; Al-Ani, H.; Bazikian, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Mavacamten in the Treatment of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review. Heart Lung Circ 2023, 32, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Mealiffe, M.E.; Bach, R.G.; Bhattacharya, M.; Choudhury, L.; Edelberg, J.M.; Hegde, S.M.; Jacoby, D.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Lester, S.J.; et al. Evaluation of Mavacamten in Symptomatic Patients With Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 75, 2649–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Choudhury, L.; Olivotto, I.; Saberi, S.; Wang, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Nagueh, S.F.; Rader, F.; et al. Phase 2 Study of Aficamten in Patients With Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023, 81, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, A.T.; Masri, A.; Abraham, T.P.; Choudhury, L.; Rader, F.; Symanski, J.D.; Turer, A.T.; Wong, T.C.; Tower-Rader, A.; Coats, C.J.; et al. Aficamten for Drug-Refractory Severe Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Patients Receiving Disopyramide: REDWOOD-HCM Cohort 3. J Card Fail 2023, 29, 1576–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Nassif, M.E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Abraham, T.P.; Arad, M.; Cardim, N.; Choudhury, L.; Claggett, B.; Coats, C.J.; et al. Impact of Aficamten on Disease and Symptom Burden in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Results From SEQUOIA-HCM. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maron, M.S.; Masri, A.; Nassif, M.E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Arad, M.; Cardim, N.; Choudhury, L.; Claggett, B.; Coats, C.J.; Dungen, H.D.; et al. Aficamten for Symptomatic Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2024, 390, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masri, A.; Cardoso, R.N.; Abraham, T.P.; Claggett, B.L.; Coats, C.J.; Hegde, S.M.; Kulac, I.J.; Lee, M.M.Y.; Maron, M.S.; Merkely, B.; et al. Effect of Aficamten on Cardiac Structure and Function in Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: SEQUOIA-HCM CMR Substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2024, 84, 1806–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pavia, P.; Bilen, O.; Burroughs, M.; Costabel, J.P.; de Barros Correia, E.; Dybro, A.M.; Elliott, P.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Mann, A.; Nair, A.; et al. Aficamten vs Metoprolol for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: MAPLE-HCM Rationale, Study Design, and Baseline Characteristics. JACC Heart Fail 2025, 13, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.J.; Maron, M.S.; Semsarian, C. Genetics of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after 20 years: clinical perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012, 60, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forleo, C.; Carella, M.C.; Basile, P.; Carulli, E.; Dadamo, M.L.; Amati, F.; Loizzi, F.; Sorrentino, S.; Dentamaro, I.; Dicorato, M.M.; et al. Missense and Non-Missense Lamin A/C Gene Mutations Are Similarly Associated with Major Arrhythmic Cardiac Events: A 20-Year Single-Centre Experience. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paratz, E.D.; Mundisugih, J.; Rowe, S.J.; Kizana, E.; Semsarian, C. Gene Therapy in Cardiology: Is a Cure for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy on the Horizon? Can J Cardiol 2024, 40, 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Marti-Gutierrez, N.; Park, S.W.; Wu, J.; Lee, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Koski, A.; Ji, D.; Hayama, T.; Ahmed, R.; et al. Correction of a pathogenic gene mutation in human embryos. Nature 2017, 548, 413–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, A.C.; Cui, M.; Chemello, F.; Li, H.; Chen, K.; Tan, W.; Atmanli, A.; McAnally, J.R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; et al. Base editing correction of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in human cardiomyocytes and humanized mice. Nat Med 2023, 29, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichart, D.; Newby, G.A.; Wakimoto, H.; Lun, M.; Gorham, J.M.; Curran, J.J.; Raguram, A.; DeLaughter, D.M.; Conner, D.A.; Marsiglia, J.D.C.; et al. Efficient in vivo genome editing prevents hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in mice. Nat Med 2023, 29, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mearini, G.; Stimpel, D.; Geertz, B.; Weinberger, F.; Kramer, E.; Schlossarek, S.; Mourot-Filiatre, J.; Stoehr, A.; Dutsch, A.; Wijnker, P.J.; et al. Mybpc3 gene therapy for neonatal cardiomyopathy enables long-term disease prevention in mice. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wakimoto, H.; Seidman, J.G.; Seidman, C.E. Allele-specific silencing of mutant Myh6 transcripts in mice suppresses hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Science 2013, 342, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, A.S.; Thompson, A.D.; Day, S.M. Translation of New and Emerging Therapies for Genetic Cardiomyopathies. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2022, 7, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaski, B.E.; Jessup, M.L.; Mancini, D.M.; Cappola, T.P.; Pauly, D.F.; Greenberg, B.; Borow, K.; Dittrich, H.; Zsebo, K.M.; Hajjar, R.J.; et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in cardiac disease (CUPID Trial), a first-in-human phase 1/2 clinical trial. J Card Fail 2009, 15, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, B.; Butler, J.; Felker, G.M.; Ponikowski, P.; Voors, A.A.; Desai, A.S.; Barnard, D.; Bouchard, A.; Jaski, B.; Lyon, A.R.; et al. Calcium upregulation by percutaneous administration of gene therapy in patients with cardiac disease (CUPID 2): a randomised, multinational, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet 2016, 387, 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, S.C.; Ackerman, M.J.; Ommen, S.R.; Cabalka, A.K.; Hagler, D.J.; O'Leary, P.W.; Dearani, J.A.; Cetta, F.; Eidem, B.W. Impact of septal myectomy on left atrial volume and left ventricular diastolic filling patterns: an echocardiographic study of young patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2008, 21, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bytyci, I.; Nistri, S.; Morner, S.; Henein, M.Y. Alcohol Septal Ablation versus Septal Myectomy Treatment of Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, U.; Yilmaz Can, Y.; Duygu, E.; Karabulut, D.; Keskin, K.; Okay, T. Periprocedural, Short-Term, and Long-Term Outcomes of Alcohol Septal Ablation in Patients with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy: A 20-Year Single-Center Experience. Anatol J Cardiol 2022, 26, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmelstiel, C.; Rowin, E.J. Fixed, high-volume alcohol dose for septal ablation: High risk with no benefit. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2020, 95, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawin, D.; Lawrenz, T.; Marx, K.; Danielsmeier, N.B.; Poudel, M.R.; Stellbrink, C. Gender disparities in alcohol septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Heart 2022, 108, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasahira, Y.; Yamada, R.; Doi, N.; Uemura, S. Urgent percutaneous transluminal septal myocardial ablation for left ventricular outflow tract obstruction exacerbated after surgical aortic valve replacement. Clin Case Rep 2021, 9, e04789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchel, J.; Leibundgut, G.; Badertscher, P.; Kuhne, M.; Krisai, P. Radiofrequency ablation in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep 2024, 8, ytae359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommen, S.R.; Ho, C.Y.; Asif, I.M.; Balaji, S.; Burke, M.A.; Day, S.M.; Dearani, J.A.; Epps, K.C.; Evanovich, L.; Ferrari, V.A.; et al. 2024 AHA/ACC/AMSSM/HRS/PACES/SCMR Guideline for the Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2024, 149, e1239–e1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva Menezes Junior, A.; de Oliveira, A.L.V.; Maia, T.A.; Botelho, S.M. A Narrative Review of Emerging Therapies for Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rev 2023, 19, e240323214927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, B.J.; Rowin, E.J.; Maron, M.S. Evolution of risk stratification and sudden death prevention in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Twenty years with the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Heart Rhythm 2021, 18, 1012–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, W.; Warner, E.; Khandait, H.; Sachdeva, S.; Abdalla, A.S.; Shafique, M.; Khan, M.A.; Roomi, S.; Khattak, F.; Alraies, M.C. Septal Myectomy or Alcohol Ablation for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) Database Analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 2023, 50, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afanasyev, A.V.; Bogachev-Prokophiev, A.V.; Zheleznev, S.I.; Zalesov, A.S.; Budagaev, S.A.; Shajahmetova, S.V.; Nazarov, V.M.; Demin, II; Sharifulin, R.M.; Pivkin, A.N.; et al. Early post-septal myectomy outcomes for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2022, 30, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, Y.; Shimoda, T.; Shimada, Y.J.; Shimamura, J.; Akita, K.; Yasuda, R.; Takayama, H.; Kuno, T. Alcohol septal ablation versus surgical septal myectomy of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2023, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, A.G.; Reitz, B.A.; Epstein, S.E.; Henry, W.L.; Conkle, D.M.; Itscoitz, S.B.; Redwood, D.R. Operative treatment in hypertrophic subaortic stenosis. Techniques, and the results of pre and postoperative assessments in 83 patients. Circulation 1975, 52, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Zhu, W.; Ma, J.; Fu, B.; Zeng, X.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, J.; et al. Clinical Effect of the Modified Morrow Septal Myectomy Procedure for Biventricular Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2024, 25, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefano, P.; Argiro, A.; Bacchi, B.; Iannone, L.; Bertini, A.; Zampieri, M.; Cerillo, A.; Olivotto, I. Does a standard myectomy exist for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? From the Morrow variations to precision surgery. Int J Cardiol 2023, 371, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.; Guo, H.; Li, J.; Dai, J.; Ren, C.; Wang, Y. Comparison of surgical results in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy after classic or modified morrow septal myectomy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, R.L.; Hannah, H., 3rd; Carley, J.E.; Pugh, D.M. Surgical treatment of idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis (IHSS). Postoperative results in 30 patients following ventricular septal myotomy and myectomy (Morrow procedure). Circulation 1977, 56, II128–132. [Google Scholar]

- Quinones, J.A.; DeLeon, S.Y.; Vitullo, D.A.; Hofstra, J.; Cziperle, D.J.; Shenoy, K.P.; Bell, T.J.; Fisher, E.A. Regression of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy after modified Konno procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 1995, 60, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laredo, M.; Khraiche, D.; Raisky, O.; Gaudin, R.; Bajolle, F.; Maltret, A.; Chevret, S.; Bonnet, D.; Vouhe, P.R. Long-term results of the modified Konno procedure in high-risk children with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018, 156, 2285–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.N.; Chung, M.M.; Vinogradsky, A.V.; Richmond, M.E.; Zuckerman, W.A.; Goldstone, A.B.; Bacha, E.A. Long-term outcomes of surgery for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a pediatric cohort. JTCVS Open 2023, 16, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkala, M.R.; Schaff, H.V.; Nishimura, R.A.; Abel, M.D.; Sorajja, P.; Dearani, J.A.; Ommen, S.R. Transapical approach to myectomy for midventricular obstruction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 2013, 96, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Schaff, H.V.; Nishimura, R.A.; Geske, J.B.; Dearani, J.A.; Ommen, S.R. Transapical Septal Myectomy for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy With Midventricular Obstruction. Ann Thorac Surg 2021, 111, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehman, B.; Ghoreishi, M.; Foster, N.; Wang, L.; D'Ambra, M.N.; Maassel, N.; Maghami, S.; Quinn, R.; Dawood, M.; Fisher, S.; et al. Transmitral Septal Myectomy for Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Ann Thorac Surg 2018, 105, 1102–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakaguchi, T.; Totsugawa, T.; Tamura, K.; Hiraoka, A.; Chikazawa, G.; Yoshitaka, H. Minimally invasive trans-mitral septal myectomy for diffuse-type hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018, 66, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, K.; Wang, F.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Wang, C. Enlargement of left ventricular outflow tract using an autologous pericardial patch for anterior mitral valve leaflet and septal myectomy through trans-mitral approach for the treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. J Card Surg 2021, 36, 4198–4202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massera, D.; Xia, Y.; Li, B.; Riedy, K.; Swistel, D.G.; Sherrid, M.V. Mitral annular calcification in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2022, 349, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Nie, C.; Zhu, C.; Meng, Y.; Yang, Q.; Lu, T.; Lu, Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, S. Mitral annular calcification in obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Incidence, risk factors, and prognostic value after myectomy. Int J Cardiol 2023, 391, 131266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, H.; Seggewiss, H.; Gietzen, F.H.; Boekstegers, P.; Neuhaus, L.; Seipel, L. Catheter-based therapy for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. First in-hospital outcome analysis of the German TASH Registry. Z Kardiol 2004, 93, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.S., Jr. Current state of the roles of alcohol septal ablation and surgical myectomy in the treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2020, 10, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Mahony, C.; Mohiddin, S.A.; Knight, C. Alcohol Septal Ablation for the Treatment of Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy. Interv Cardiol 2014, 9, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragnano, F.; Pelliccia, F.; Guarnaccia, N.; Niccoli, G.; De Rosa, S.; Piccolo, R.; Moscarella, E.; Fabris, E.; Montone, R.A.; Cesaro, A.; et al. Alcohol Septal Ablation in Patients with Hypertrophic Obstructive Cardiomyopathy: A Contemporary Perspective. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataiosu, D.R.; Rakowski, H. Septal Reduction Strategies in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy-The Scalpel, Catheter, or Wire? JAMA Cardiol 2022, 7, 538–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, M.F.; Ahmed, A.A.; Baron, S.J.; Labib, S.B.; Gadey, G. The use of MitraClip to prevent posttranscatheter aortic valve replacement left ventricular "suicide". Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2021, 97, 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veselka, J.; Faber, L.; Liebregts, M.; Cooper, R.; Januska, J.; Kashtanov, M.; Dabrowski, M.; Hansen, P.R.; Seggewiss, H.; Bonaventura, J.; et al. Alcohol dose in septal ablation for hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol 2021, 333, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raimondo, C.; Balsam, P. Alternative Management Options for Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Feasible? JACC Case Rep 2020, 2, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okutucu, S.; Aytemir, K.; Oto, A. Glue septal ablation: A promising alternative to alcohol septal ablation. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis 2016, 5, 2048004016636313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, M.; Pinte, F.; Tintoiu, I.; Cotuna, L.; Caroescu, M.; Popa, A.; Cristian, G.; Goleanu, V.; Greere, V.; Moscaliuc, I.; et al. Microcoil embolisation for ablation of septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. Kardiol Pol 2004, 61, 350–355. [Google Scholar]

- Iacob, M.; Pinte, F.; Tintoiu, I.; Cotuna, L.; Coroescu, M.; Filip, S.; Popa, A.; Cristian, G.; Goleanu, V.; Greere, V.; et al. Microcoil embolization for ablation of septal hypertrophy in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. EuroIntervention 2005, 1, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banthiya, S.; Check, L.; Atkins, J. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy as a Form of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction: Diagnosis, Drugs, and Procedures. US Cardiol 2024, 18, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udelson, J.E.; Bonow, R.O.; O'Gara, P.T.; Maron, B.J.; Van Lingen, A.; Bacharach, S.L.; Epstein, S.E. Verapamil prevents silent myocardial perfusion abnormalities during exercise in asymptomatic patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 1989, 79, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommen, S.R.; Mital, S.; Burke, M.A.; Day, S.M.; Deswal, A.; Elliott, P.; Evanovich, L.L.; Hung, J.; Joglar, J.A.; Kantor, P.; et al. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2020, 142, e558–e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, P.; Monitillo, F.; Santoro, D.; Falco, G.; Carella, M.C.; Khan, Y.; Moretti, A.; Santobuono, V.E.; Memeo, R.; Pontone, G.; et al. Impact on ventricular arrhythmic burden of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with chronic heart failure evaluated with cardiac implantable electronic device monitoring. J Cardiol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velicki, L.; Popovic, D.; Okwose, N.C.; Preveden, A.; Tesic, M.; Tafelmeier, M.; Charman, S.J.; Barlocco, F.; MacGowan, G.A.; Seferovic, P.M.; et al. Sacubitril/valsartan for the treatment of non-obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An open label randomized controlled trial (SILICOFCM). Eur J Heart Fail 2024, 26, 1361–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, Y.J.; Passeri, J.J.; Baggish, A.L.; O'Callaghan, C.; Lowry, P.A.; Yannekis, G.; Abbara, S.; Ghoshhajra, B.B.; Rothman, R.D.; Ho, C.Y.; et al. Effects of losartan on left ventricular hypertrophy and fibrosis in patients with nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail 2013, 1, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivotto, I.; Ashley, E.A. INHERIT (INHibition of the renin angiotensin system in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the Effect on hypertrophy-a Randomised Intervention Trial with losartan). Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2015, 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Day, S.M.; Axelsson, A.; Russell, M.W.; Zahka, K.; Lever, H.M.; Pereira, A.C.; Colan, S.D.; Margossian, R.; Murphy, A.M.; et al. Valsartan in early-stage hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1818–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coats, C.J.; Pavlou, M.; Watkinson, O.T.; Protonotarios, A.; Moss, L.; Hyland, R.; Rantell, K.; Pantazis, A.A.; Tome, M.; McKenna, W.J.; et al. Effect of Trimetazidine Dihydrochloride Therapy on Exercise Capacity in Patients With Nonobstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol 2019, 4, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivotto, I.; Camici, P.G.; Merlini, P.A.; Rapezzi, C.; Patten, M.; Climent, V.; Sinagra, G.; Tomberli, B.; Marin, F.; Ehlermann, P.; et al. Efficacy of Ranolazine in Patients With Symptomatic Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The RESTYLE-HCM Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Circ Heart Fail 2018, 11, e004124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrid, M.V. Drug Therapy for Hypertrophic Cardiomypathy: Physiology and Practice. Curr Cardiol Rev 2016, 12, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iavarone, M.; Monda, E.; Vritz, O.; Calila Albert, D.; Rubino, M.; Verrillo, F.; Caiazza, M.; Lioncino, M.; Amodio, F.; Guarnaccia, N.; et al. Medical treatment of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: An overview of current and emerging therapy. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2022, 115, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicorato, M.M.; Basile, P.; Naccarati, M.L.; Carella, M.C.; Dentamaro, I.; Falagario, A.; Cicco, S.; Forleo, C.; Guaricci, A.I.; Ciccone, M.M.; et al. Predicting New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: A Review. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, L.; Gupta, M.; Sabzwari, S.R.A.; Agrawal, S.; Agarwal, M.; Nazir, T.; Gordon, J.; Bozorgnia, B.; Martinez, M.W. Atrial fibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: prevalence, clinical impact, and management. Heart Fail Rev 2019, 24, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveri, F.; Pepe, A.; Bongiorno, A.; Fasolino, A.; Gentile, F.R.; Schirinzi, S.; Colombo, D.; Breviario, F.; Greco, A.; Turco, A.; et al. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Atrial Fibrillation: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Anticoagulation Strategy. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2023, 23, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).